This report provides our projections of General Fund revenues and

expenditures for 2002-03 through 2007-08 It includes our independent

assessment of the outlook for California's economy, demographics,

revenues, and expenditures.

Chapter 1 contains our principal findings and conclusions. Chapter 2

presents our economic and demographic projections, Chapter 3 our

revenue forecasts, and Chapter 4 our expenditure projections.

Our fiscal projections reflect current-law spending requirements and tax

provisions. They are not predictions of future policy decisions by the Legislature, nor

are they our recommendations as to what spending and revenue levels should be.

This report, in its eighth year of publication, reflects the historical mission

of the Legislative Analyst's Office to assist the Legislature with its fiscal planning

by assessing the revenues and expenditures of the state. The report is part of

an ongoing series and is updated periodically.

Chapter 1: The Budget Outlook

Chapter 2: Economic and Demographic Projections

Chapter 3: Revenue Projections

Chapter 4: Expenditure Projections

California policymakers will be facing an enormous challenge in crafting the 2003-04 General Fund budget. For the second year in a row, the state faces a budget problem in excess of $20 billion. Specifically, our updated forecast indicates the following:

Given that the General Fund budget enacted for 2002-03 only a few months ago was balanced with a $1 billion reserve, a natural question to ask is: How could such an enormous problem for 2003-04 develop so fast? As discussed below, two main factors are responsible:

About one-half of the projected 2003-04

budget problem relates to an underlying operating shortfall in California's

General Fund budget that would have existed even

without the recent deterioration in the economic

and revenue outlook.

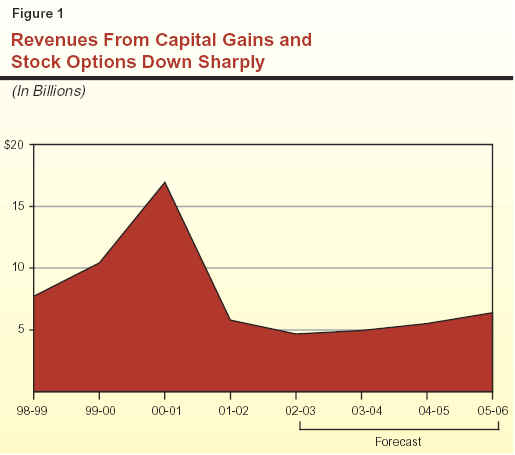

Stock Market Collapse a Key Factor.

As we have indicated in previous reports, the state has faced

a large and ongoing imbalance between revenues and expenditures since the stock market bubble

burst and tax revenues fell by over $10 billion in 2001-02. The dramatic impact of the stock market decline is depicted in Figure 1, which shows

the amount of personal income taxes attributable

to stock options and capital gains. It indicates

that these tax revenues peaked at $17 billion in

2000-01, but fell abruptly following the stock market

decline—to under $6 billion in 2001-02. This

unprecedented 66 percent decline is the key factor

behind the $10-plus billion annual mismatch between

revenues and expenditures that began in 2001-02.

One-Time Solutions Provided Only

Temporary Relief. In dealing with the cumulative

$23.6 billion budget shortfall facing the state in 2002-03, the

Governor and Legislature relied primarily on

one-time actions to close the gap. While these actions

addressed the cumulative shortfall in the 2002-03 budget itself, they did not eliminate the

underlying current-law gap between revenues and

expenditures. Thus, the expenditure-revenue

mismatch was destined to reappear. Consequently, even if

all of the assumptions embedded in the 2002-03

budget had held up, the state would have still faced

an operating shortfall of over $10 billion in 2003-04.

The other roughly half of the projected

$21 billion cumulative shortfall in 2003-04 largely

relates to the recent deterioration in the revenue

outlook resulting from near-stagnant economic

conditions in past months. This factor has caused us to

reduce our General Fund revenue forecasts relative to

our earlier projections by $777 million in

2001-02, $4.1 billion in 2002-03, and $6.5 billion for 2003-04—or a total of $11.4 billion for the

three years combined.

Our updated estimate of the 2003-04 shortfall also includes the impacts of revised

assumptions about new federal funds, retirement

incentives, Medi-Cal fraud detection, and state operations

reductions—as well as savings related to lower

Proposition 98 spending in 2003-04. On balance,

these expenditure revisions have worsened the

budget's bottom-line condition, although not to the

same extent as have revenues.

Recent Trends Have Been Weak. Although the national and state economic downturns appear

to have bottomed out in late 2001, the economic expansion has been extremely sluggish in 2002.

At the national level, consumer spending has

increased over the past year, but business spending and

net exports have been soft. These trends have also

been evident in California, where growth has been

extremely limited in recent months.

Modest Growth Expected. Our updated

forecast assumes that the national and state economies

will continue to expand at subdued rates until

mid-2003, when improvements in business spending and

export sales start to boost overall economic

growth. Specifically, we forecast that U.S. gross

domestic product will increase by about 2.5 percent this

year and 2.6 percent in 2003, before accelerating to

annual growth rates in the 3 percent to 4 percent

range in subsequent years. In California, we forecast

that, following a marginal gain of 1.2 percent in

2002, personal income growth will accelerate to

4 percent in 2003, slightly over 6 percent in 2004, and

to between 6 percent and 7 percent in subsequent years.

Downside Risks Exist. Our forecast is subject

to a significant downside risk that further delays

in business hiring and spending, coupled with sagging consumer confidence and spending, will

depress U.S. and California economic growth below

our current forecast. Another risk involves the

resolution of the current labor-management dispute

involving workers at West Coast ports. A protracted

economic slowdown could reduce state General Fund

revenues by several billions of dollars below our baseline

forecast in the current and budget years combined.

We currently forecast that revenues will

grow from $73.1 billion in 2001-02 to $75 billion

in 2002-03, before declining to $70.2 billion in Revenue Revisions. As indicated above, our

revenue forecast is down from the 2002-03 Budget

Act estimates by $777 million in 2001-02 and

by $4.1 billion in 2002-03. In addition, our

estimates for 2003-04 and beyond are below our

previous estimates by about $6 billion annually. These

substantial downward revisions are primarily

associated with the personal income tax. Collections

from this source are being adversely affected by (1)

the continued reductions of jobs and income in

high-paying manufacturing and software industries,

and (2) continued declines in stock market values,

which will result in reduced levels of taxable income

from stock options and capital gains. To a lesser

degree, sluggish economic growth is also depressing

collections from the sales tax and corporation tax.

2003-04. These totals are affected by a variety

of special factors, which are discussed in

Chapter 3. Absent these factors,

underlying revenues fell by about 16 percent in 2001-02, and are expected

to decline another 1 percent in 2002-03 before

growing about 5.6 percent in 2003-04. Over the

longer term, revenue growth is forecast to average

roughly 7 percent per year.

Figure 2 presents our updated General Fund condition projections for 2001-02 through 2003-04. These estimates take into account our revised projections of current-law revenues and expenditures, discussed in Chapter 3 and Chapter 4, respectively.

|

Figure 2 LAO Projections of General

Fund Condition |

||||||

|

2001-02 Through 2003-04 |

||||||

|

|

|

Forecast |

||||

|

2001-02 |

2002-03 |

2003-04 |

||||

|

Prior-year fund balance |

$2,627 |

-$1,192 |

-$4,635 |

|||

|

Revenues and transfers |

73,121 |

75,010 |

70,199 |

|||

|

Total

resources available |

$75,748 |

$73,818 |

$65,564 |

|||

|

Expenditures |

76,940 |

78,453 |

85,216 |

|||

|

Ending Fund Balance |

-$1,192 |

-$4,635 |

-$19,652 |

|||

|

Encumbrances |

1,473 |

1,473 |

1,473 |

|||

|

Reserve |

-$2,665 |

-$6,108 |

-$21,125 |

|||

Deficit to Exceed $6 Billion. The 2002-03 budget enacted in September assumed that the current fiscal year would end with a positive reserve of $1 billion. However, we estimate that the large combined $4.9 billion reduction in 2001-02 and 2002-03 revenues, coupled with $1.8 billion in added expenditures and a $410 million deterioration in the 2001-02 carry-in balance, will use up the reserve and push the state into a deficit of $6.1 billion in the current year. As discussed above, the decline in revenues reflects the deterioration in the near-term economic outlook. The increase in expenditures is due to our revised estimates related to new federal funds, the state retirement incentive program, state operations reductions, and Medi-Cal fraud detection.

Current Law Assumed. Our revenue and expenditure forecasts for 2003-04 and beyond are

based primarily on the requirements of current law.

For example, we have adjusted the current-year

spending plan for constitutional and statutory

funding requirements (such as the Proposition 98

minimum funding guarantee for K-14 education), as well as for projected changes in caseloads,

cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs), federal

reimbursements, and other factors affecting program

costs. We have also adjusted the budget for

one-time costs and savings in the current year.

Projections, Not Predictions. It is important

to note that our fiscal projections are not

predictions of what the Legislature and Governor will adopt

as policies and funding levels in future budgets. Rather, our estimates are intended to be a

reasonable "baseline" projection of what would

happen if current-law policies were allowed to operate

in the future. In this regard, we believe that our

forecast provides a meaningful starting point for

legislative deliberations involving the state's budget.

Treatment of Loan Repayments and

Mandates. In preparing our estimates for 2003-04 and

beyond, we needed to make assumptions about

repayments of loans to the General Fund from special funds,

as well as state payments to localities associated

with mandates which were deferred in 2002-03. With regard to loan repayments, our estimates

include the timely repayment of all loans which had

specific repayment dates scheduled in the budget.

We also assume that about one-half of the

remaining loans are repaid evenly over the forecast

period. With regard to state-imposed local mandates

(excluding education), we assume that prior-year claims will be paid off over the forecast period.

Key Elements. As shown in Figure 2, we

estimate that revenues will fall from $75 billion in $21 Billion Imbalance

Projected. The combination of the expenditure increases and revenue

reduction in 2003-04 will result in an operating

deficit of nearly $15 billion in the budget year. Thus,

when combined with the $6.1 billion deficit carry-in

from 2002-03, the 2003-04 budget faces a cumulative

shortfall of roughly $21 billion, absent corrective actions.

2002-03 to $70.2 billion in 2003-04. The

decline reflects the large amount of one-time

revenues, loans, and transfers that total $9.5 billion in

2002-03, but which are largely absent in 2003-04. At

the same time, expenditures are projected to

increase from $78.5 billion in the current year to

$85.2 billion in 2003-04. The increase reflects a variety

of factors, including new General Fund costs

associated with health programs previously funded

from the tobacco settlement special fund, the

annualized costs of COLAs provided for the Supplemental

Security Income/State Supplementary Program in

June 2003, $1.2 billion in added funding for

transportation spending (as mandated by Proposition 42), and

additional costs for employer retirement

contributions. General Fund Proposition 98 funding is

projected to grow by only 2.4 percent in 2003-04,

due to (1) a relatively small increase in the

minimum funding guarantee and (2) a rapid increase in

local property taxes, which reduces the General Fund

share of total Proposition 98 funding.

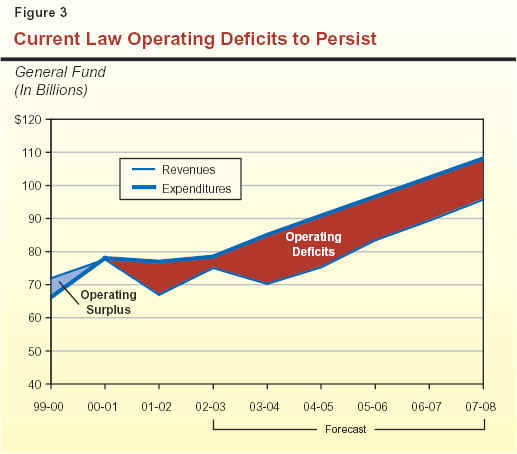

Figure 3 presents our revenue and expenditure forecasts through 2007-08. It indicates that current-law operating deficits are expected to persist over the entire period, absent corrective actions.

On the positive side, we do expect revenues to grow somewhat more rapidly than

expenditures over these years, as evidenced in Figure 3 by

the revenue line closing in a bit on the expenditure

line over time. Our projected faster growth for

revenues than for expenditures reflects our assumption

that revenue growth will accelerate in 2004-05 as the

economic expansion gains momentum. It also reflects relatively

slow growth in General Fund Proposition 98

spending, due primarily to slowing growth in K-12 school

enrollments. As a result of the above factors, our

projected operating deficits do decline slightly over time.

Despite these favorable trends, however,

projected revenues remain well below expenditures at

all times over the forecast period. Specifically, as

the figure indicates, we expect that annual operating

deficits peak at $15.6 billion in 2004-05 before slowly

declining to $12.3 billion by 2007-08. The

persistence of these large mismatches between current-law

revenues and expenditures indicates that the state

has a large structural budgetary imbalance that it

cannot simply "grow" its way out of on the natural. As

a result, substantial budget-balancing actions will

be needed.

Last year, when the state faced a cumulative $23.6 billion budget problem, we identified for the Legislature a variety of principles, strategies, and tools for dealing with the shortfall (see, for example, our report entitled Addressing the State's Fiscal Problem, December 2002). The current budget shortfall is much more formidable and challenging than last year's. This is due both to the magnitude of the problem and because a number of the one-time solutions heavily relied on last year cannot be used again—such as the $4.5 billion raised from tobacco securitization, the $1.1 billion near-term savings from restructuring repayments of state general obligation bonds, and certain loans and tax accelerations. Given this, there is really no easy way out of the current predicament, and this makes it all the more important that the Legislature take advantage of the alternative budget-balancing approaches and options available to it.

Figure 4 summarizes in broad terms the various key budget-balancing principles, strategies, and tools that we have previously identified and that we believe merit the Legislature's attention again this year.

|

Figure 4 Basic Budget-Balancing

Principles, Strategies, and Tools |

|

Key Principles |

|

�

Wide range of budget solutions should be considered. |

|

�

Out-year repercussions should be assessed. |

|

�

Budget solutions should �make sense.� |

|

�

Current-year solutions should play a key role. |

|

Basic Strategies |

|

�

Determine the relative roles of spending and revenue

options. |

|

�

Identify the appropriate contributions of different

program areas. |

|

�

Establish the desired mix of one-time versus ongoing

solutions. |

|

�

Assess whether a multiyear solution is appropriate and

feasible. |

|

Individual Tools |

|

�

Spending-related options. |

|

�

Eliminate or modify programs. |

|

�

Suspend/reduce COLAs. |

|

�

Defer spending. |

|

�

Shift funding from the General Fund. |

|

�

Implement improvements and efficiencies. |

|

�

Revert or disencumber funds. |

|

�

Revenue-related options. |

|

�

Eliminate or modify tax expenditures. |

|

�

Broaden basic tax bases. |

|

�

Raise tax rates. |

|

�

Transfer special fund balances. |

|

�

Improve tax compliance and collections. |

|

�

Revise accrual procedures and sell assets. |

Of particular importance are:

I

n the coming months, our office will be assisting the Legislature in developing possible budgetbalancing expenditure and revenue strategies and options to help address the large projected 2003-04 shortfall.Economic and demographic developments in California have important effects on the state's fiscal condition through their impacts on both tax revenues and state expenditures. This chapter presents our economic and demographic projections for 2002 through 2008, which will affect California's fiscal condition during fiscal years 2002-03 through 2007-08.

California's economy has been hard hit by

the slump in spending on high-tech goods and services, plunging exports, and the stock

market's decline. These factors have combined to

produce soft personal income growth in the state, and

they continue to dampen economic performance as of late 2002. Looking ahead, we forecast that

the economy will continue to "muddle along"

until the second half of 2003, when a long-delayed improvement in business investment spending

is anticipated to begin to boost California's

overall job and income growth. From then on,

moderate income and job gains are expected through

the remainder of the forecast period.

Although our forecast reflects what we believe is the most likely future path for the economy,

our forecast—like any—is subject to risks

and uncertainties. In this regard, we believe that

the main risk to our forecast is on the downside—namely, our economic projections are subject

to the possibility that further declines in

consumer confidence and spending could occur that, in

turn, could result in prolonged economic weakness during the next year. In this event, both

the economy and the state's fiscal condition would under-perform our expectations.

Figure 1 summarizes the details of our economic forecast, while the current

state of the economy and the major components of

our economic forecast are discussed below.

|

Figure 1 The LAO�s Economic

Forecast |

|||||||

|

Percentage Change (Unless Otherwise Indicated) |

|||||||

|

|

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

|

United States |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Real

gross domestic product |

2.5% |

2.6% |

3.8% |

3.6% |

2.9% |

3.0% |

3.0% |

|

Personal

income |

3.2 |

4.5 |

5.9 |

6.1 |

5.7 |

5.4 |

5.4 |

|

Wage

and salary jobs |

-0.8 |

1.2 |

2.5 |

1.7 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

|

Consumer

Price Index |

1.7 |

2.9 |

2.9 |

2.9 |

2.6 |

2.4 |

2.3 |

|

Unemployment

rate (%) |

5.8 |

5.9 |

5.3 |

5.0 |

5.1 |

5.1 |

4.8 |

|

Housing

starts (000) |

1,637 |

1,572 |

1,711 |

1,704 |

1,669 |

1,698 |

1,730 |

|

California |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Personal

income |

1.2% |

4.0% |

6.1% |

6.7% |

7.0% |

6.5% |

6.4% |

|

Wage

and salary jobs |

-0.8 |

0.5 |

2.4 |

2.6 |

2.7 |

2.3 |

2.1 |

|

Taxable

sales |

-1.4 |

3.9 |

6.2 |

6.9 |

6.9 |

6.3 |

6.2 |

|

Consumer

Price Index |

2.7 |

2.5 |

2.9 |

3.0 |

3.1 |

2.7 |

2.7 |

|

Unemployment

rate (%) |

6.2 |

6.1 |

5.6 |

5.3 |

5.1 |

5.0 |

5.1 |

|

New

housing permits (000) |

155 |

153 |

157 |

164 |

165 |

168 |

165 |

After falling in 2001, the U.S. economy

has experienced a modest rebound over the past

year. For example, U.S. real gross domestic

product (GDP) grew by 3 percent between the third

quarter of 2001 and the third quarter of 2002. This

output increase has occurred despite virtually no

growth in employment and only modest gains in

personal income, and thus is attributable primarily

to increased productivity.

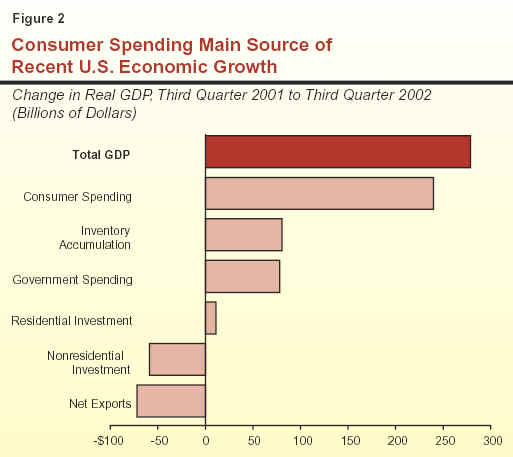

As shown in Figure 2, most of the recent growth in U.S. output has

been related to consumer spending, which has remained

surprisingly strong in view of the lack of job and income

growth over the past year. A key force behind this continued

spending growth has been low interest rates, which

have boosted sales of automobiles and other interest-sensitive

durable goods. Declining mortgage rates have also produced

a boom in both new home sales and financings, as

well as the refinancing of existing mortgages. The new home activity

has directly added to output, and the refinancings

have enabled individuals to reduce their home

payments and/or "cash out" some of their previously

built-up home equity—in both cases providing additional funds for spending.

A very important question for the U.S.

outlook is how much longer can consumer spending

carry the economic expansion—especially in view of

the recent lack of employment and personal income growth in the economy. In this regard, a key

to future economic growth would appear to be increased business spending on capital

equipment and labor.

Normally, continued growth in consumer spending would be matched by new

investment and hiring by businesses. However, this has

not been the case during the past year. For

example, nonresidential investment, which includes spending by businesses on new plants

and equipment, fell by over 4 percent between the

third quarter of 2001 and the third quarter of 2002

(see Figure 2). The decline in business

investment, coupled with cautious attitudes by

employers generally, has contributed to a 190,000 drop

in private sector jobs since the beginning of the year.

The lack of business spending on plants and equipment reflects the large amount of idle

capacity that currently exists in the economy, which

has partly resulted from past over-investment by

many businesses in telecommunications and other

high-tech areas. It also reflects pressures that

businesses are facing from their shareholders and directors

to control costs and improve their "bottom

line" profit statements. These factors have translated

into delays or cancellations of equipment and

software upgrades, and sharp cutbacks in hiring.

The lack of job growth, coupled with declining stock market values and other uncertainties,

is starting to take a toll on consumers. The

Conference Board's consumer confidence survey plunged to

a nine-year low in October, and preliminary

reports suggest that retail sales softened in October.

A slowdown in consumer spending would have major implications for the overall

economic expansion, since consumer spending accounts

for over two-thirds of economic output.

Given these factors, a key to the outlook is an improvement in business spending and

hiring. Such an improvement would provide a

welcome boost to income and jobs, which would in

turn sustain gains in consumer spending and

overall economic growth in the future.

There are no current state-level gross domestic product data available to precisely measure output changes in California. However, the information that is available from such diverse sources as employment, personal income, withholding, taxable sales, new vehicle registrations, and building permit activity suggests that, like the nation, California's economy bottomed-out in late 2001, and has been on a weak growth path during the first ten months of 2002. The recovery has not been of sufficient magnitude to create new jobs and, in fact, California's private sector has experienced job losses during the past year. With regard to personal income, California has suffered a steeper slowdown than the rest of the nation, due to (1) a large amount of job losses in the state's high paying manufacturing sector, and (2) continued declines in stock-option income. Reflecting these factors, we estimate that the state's personal income will increase by just 1.2 percent in 2002, compared to 3.2 percent for the nation as a whole.

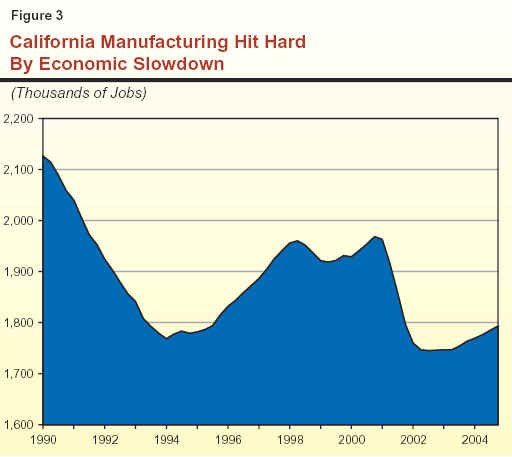

As indicated in Figure 3, total California manufacturing employment has fallen by over 230,000 jobs (12 percent) since its peak in late 2000. Although not as dramatic as in the early 1990s, when the state faced major restructuring of its defense industry, the manufacturing job downturn has nevertheless been one of the steepest two-year declines in the state's history.

A similarly large employment reduction has occurred in the state's business services job sector (which includes temporary hires by manufacturers as well as computer and software design jobs). After growing at an average rate of 8.4 percent per year between 1995 and 2000, this sector has lost 11 percent of its job base during the past two years. The losses of manufacturing and computer-related business services jobs are significant, since these are among the highest paying jobs in the state.

As with the nation generally, a key force

behind the job losses in California's

manufacturing and business services sectors has been

the weakness in national business investment spending. The decline

is important to California since so much of its

high-tech goods and services are sold to businesses.

In addition to the decline in U.S. investment spending,

manufacturers in this state are also coping with a plunge

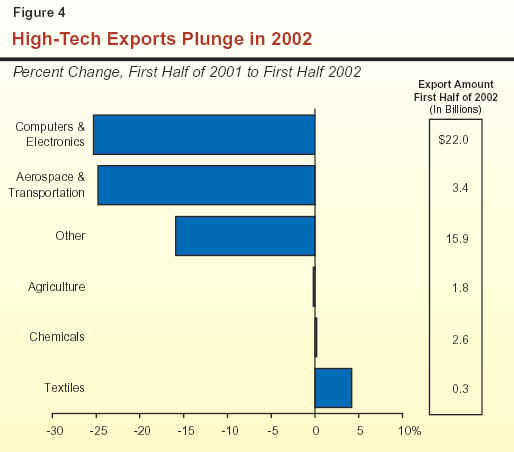

in foreign demand for their products. Total

California-produced exports fell by 11 percent in 2001 and

will decline by another 14 percent this year, due

to soft economic conditions abroad. As shown in Figure 4, the export decline between the first

half of 2001 and the first half of 2002 has been concentrated in computers, electronics,

aerospace, and transportation products. The drop in

exports is important since a significant share of

California-produced high-tech goods are sold in

other countries.

Outside of the manufacturing and

business services sectors, the California economy

has recently managed to grow at a modest pace. The main positive forces have been low interest

rates and continued California population growth.

Like the rest of the nation, California's spending

on automobiles has remained strong in 2002, buoyed by zero-interest financing promotions.

Likewise, strong home sales and mortgage

refinancings associated with low interest rates, along

with continued growth in residential construction activity, are boosting employment in

California's construction and finance-related

industries. Nonbusiness services employment is

also expanding modestly, reflecting gains in such diverse industries as health care, personal

services, and auto repair.

Increases in interest-sensitive and population-driven industries have managed to

keep California's economy on a slight upward track

thus far in 2002. However, it is unlikely that they

can continue to offset the negative effects of

falling business spending and exports for much

longer. Without improvement in these latter two areas,

it is unlikely that California can sustain a

meaningful expansion.

Our forecast assumes that both the national and state economies increase at a very subdued rate through the first half of 2003. At that point, we assume that business spending will finally begin to improve, providing a much-needed boost to overall economic growth. We expect business spending to eventually improve because, although the manufacturing sector currently has a considerable amount of unused capacity, businesses will eventually need to upgrade equipment and software to take advantage of new innovations in communications, web technology, and other areas.

As indicated previously in Figure 1, we

forecast that U.S. GDP will increase by 2.5 percent and

2.6 percent in 2002 and 2003, respectively, before accelerating to 3.8 percent in 2004 and an

average of about 3.3 percent over the balance of

the forecast period. Over the longer term, growth

in U.S. economic output will be aided by healthy gains in worker productivity, which we expect

to rise by slightly over 2 percent per year.

The forecast assumes similarly modest accelerations in jobs

and income. Inflation is expected to remain relatively low over

the forecast period, with the Consumer Price Index forecast to increase by

an average of less than 3 percent over the next

six years.

As with the nation, we expect

California's economy to grow at a very sluggish pace until

the second half of 2003, with employment and

income improving slowly in 2003 before accelerating in

2004 and 2005. The improvement is tied to an assumed rebound in manufacturing employment, which we expect to

benefit from an eventual rebound in business

spending and exports.

We specifically project that personal income

will increase by 4 percent in 2003 and 6.1 percent

in 2004, and that wage and salary employment will grow by 0.5 percent and 2.4 percent during

the same two years. Continued population growth

and low interest rates will result in growth in

residential construction activity during the forecast

period. Nonresidential construction is expected to

decline through mid-2003, then slowly grow thereafter.

Our near-term forecasts for both the nation and California are below the consensus of estimates made by other economists in October 2002, particularly with regard to California personal income growth. However, given recent negative reports on employment, consumer confidence, and manufacturing activity, we believe that even our forecast is subject to considerable downside risk. The combination of a steeper slowdown in consumer spending, and further cutbacks in business investment and hiring, could further weaken near-term growth—or even produce a "double dip" recession early next year. Such a development would result in further job declines and another year of near-zero growth in personal income in 2003. It would also have substantial adverse effects on state tax revenues, and thus on the projected outlook for the General Fund's condition. Another risk involves the current labor management dispute at the West Coast ports. While our forecast assumes that current federally mediated negotiations will produce a successful resolution, a prolonged lockout or strike would disrupt commerce in California and elsewhere in the nation.

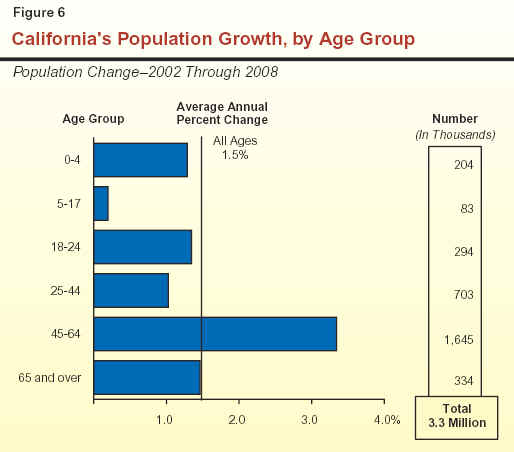

As of 2002, California's population

totaled slightly over 35 million. During the six-year

forecast period, the state's population is projected to

grow annually by about 1.5 percent, or well over half

a million persons yearly. Thus, California will

add roughly 3.3 million people over the forecast

interval and reach over 38 million by 2008.

The population growth rate we are projecting is somewhat slower than that experienced in

the latter part of the 1990s. This reflects both

the dampening effects of the slower economy on in-migration, and a continuing downward trend

in birth rates.

California's population growth can be

broken down into two major

components—natural increase (the excess of births over deaths) and

net in-migration (persons moving into California

from other states and countries, minus those leaving

for other destinations). On average, these two components tend to contribute about equally

to the state's population growth, although their relative shares can vary significantly from one

year to the next depending largely on the strength of

net in-migration.

Natural Increase. We project that the

natural-increase component will average about 285,000

new Californians annually over the forecast period.

This amount is slightly less than in the late 1990s, due

to the ongoing decline in birth rates being

experienced by all ethnic groups. Despite these declining

birth rates, however, the natural-increase component

still will grow slightly due to significant growth in

the female population of child-bearing age groups

in faster-growing segments of the population, including Hispanic and Asian women.

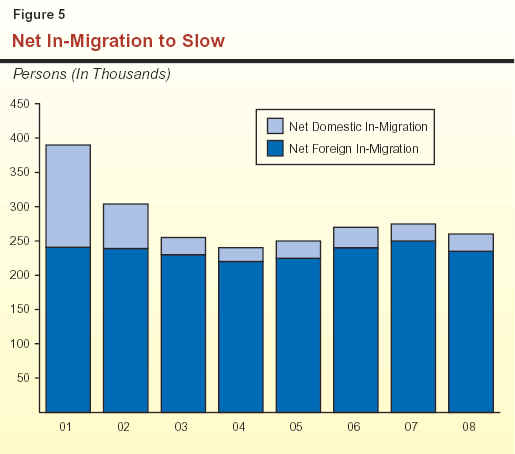

Net In-Migration. We project that net

in-migration will average roughly 265,000 annually over the next six

years. This is weaker than during the latter half of the

1990s and somewhat less than the natural-increase component. As indicated by Figure 5, this reflects

a projected drop in domestic net in-migration that

we believe will accompany California's less-than-robust economic performance. In contrast, foreign net

in-migration—which has been relatively stable over the past decade

and has proved to be less sensitive to the economy—is projected

to remain relatively flat.

Figure 6 shows our population growth projections by broad age categories, including both numerical and percentage growth.

Ranks of Baby Boomers to Swell. The 45-to-64

age group (largely the "baby boomers") continues to

be the fastest growing segment of the population. Over 1.6 million

new people are expected to move into this age category over the next

six years. At the other extreme, although continued in-migration will result

in moderate growth for preschoolers, relatively

slow growth is anticipated for the K-12 school-age population. This reflects the movement of

children of the baby boom generation beyond the

5-to-17 age group. The decline in birth rates in recent

years has also resulted in fewer children moving into

the school-age category.

These various age-group demographic projections can have significant implications

for the state's revenue and expenditure outlook.

For example, strong growth of the 45-64 age group generally benefits tax revenues since this is the

age category that routinely earns the highest wages

and salaries. Likewise, the growth in the young

adult population affects college enrollments, while

that for the 0-to-4 and 5-to-17 age groups drives

K-12 enrollment growth.

The revenues that finance California's state General Fund budget come from a wide variety of different sources, including taxes, fees, licenses, interest earnings on investments, loans, and transfers. The great majority of General Fund revenues, though, is attributable to the state's three major taxes—the personal income tax (PIT), the sales and use tax (SUT), and the corporation tax (CT). In addition, however, actions taken in conjunction with the adoption of the 2002-03 budget have also resulted in a variety of significant one-time revenue increases in the current year related to loans and the securitization of tobacco receipts. In this section, we summarize our revenue projections and provide detail behind our key revenue-related forecast assumptions.

The revenue outlook continues to deteriorate. Our updated revenue forecast, presented in Figure 1, is as follows:

|

Figure 1 The LAO�s General Fund

Revenue Forecast |

|||||||

|

(Dollars in Millions) |

|||||||

|

Revenue Source |

2001-02 |

2002-03 |

2003-04 |

2004-05 |

2005-06 |

2006-07 |

2007-08 |

|

Personal

income tax |

$33,370 |

$34,510 |

$36,380 |

$40,190 |

$44,520 |

$48,450 |

$52,490 |

|

Sales

and use tax |

21,340 |

22,420 |

23,530 |

25,200 |

26,900 |

28,670 |

30,460 |

|

Corporation

tax |

5,620 |

6,760 |

6,700 |

6,540 |

7,010 |

7,530 |

7,930 |

|

Other

revenues and transfers |

12,791 |

11,320 |

3,589 |

3,298 |

3,980 |

4,646 |

4,812 |

|

Total revenues and

transfers |

$73,121 |

$75,010 |

$70,199 |

$75,228 |

$82,410 |

$89,296 |

$95,692 |

|

Percentage

change |

|

2.6% |

-6.4% |

7.2% |

9.5% |

8.4% |

7.2% |

The major downward revisions to revenues

in the current and budget years are primarily

related to the continued softness in California's

economy. This softness is taking a greater toll on personal

income, taxable sales, and taxable profits than we

had previously estimated would be the case. In

addition, the continued deterioration in the stock

market since last spring implies that personal

income taxes from stock options and capital gains will

be even less than assumed in spring 2002.

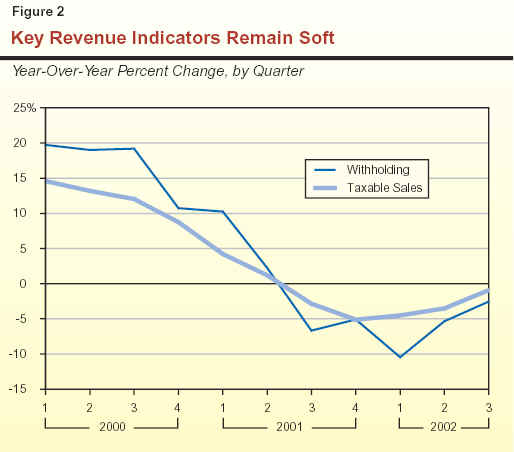

The impacts of continued softness in economic activity are evident in key California revenue

indicators. As shown in Figure 2, although both

personal income tax withholding and taxable sales have shown slight improvements since the

beginning of 2002, both measures remain below last year's already-depressed levels.

Our revenue forecast for 2002-03 and beyond includes the impacts of numerous actions taken in conjunction with the adoption of the 2002-03 budget. These include:

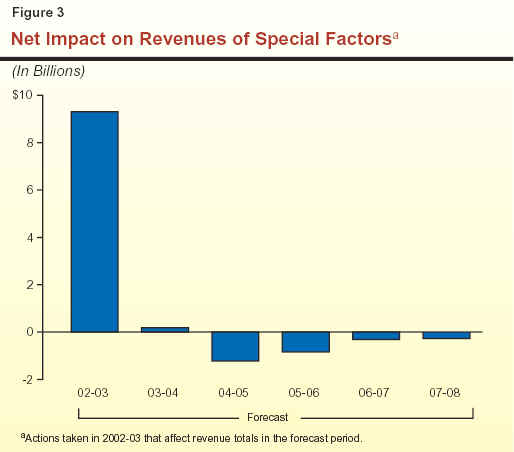

Combined Effect of Special Factors. Figure 3 shows the net impact of the above special factors on General Fund revenues during the forecast period. Taken together, special factors will increase General Fund revenues and transfers by about $9.5 billion in 2002-03. In 2003-04, the net impact of these factors will be relatively small—$188 million—as the second-year impact of the NOL suspension is partly offset by scheduled loan repayments. In subsequent years (2004-05 through 2007-08), the net impact will be annual losses ranging from $250 million to $1.2 billion. These losses are due to loan repayments and higher NOL deductions.

After its historic 25 percent plunge (from $44.6 billion to $33.4 billion) between 2000-01 and 2001-02, we project that PIT receipts will increase modestly to $34.5 billion in 2002-03 and further to $36.4 billion in 2003-04. Over the longer term, we forecast that PIT receipts will increase at an average annual rate of 9.6 percent between 2003-04 and 2007-08, reaching $52.5 billion by the end of the forecast period.

Much of the estimated PIT revenue gain between 2001-02 and 2002-03 is related to the $1 billion in PIT revenue increases adopted in conjunction with the 2002-03 budget. Absent these changes, the underlying growth in PIT receipts would be less than 1 percent. This small underlying increase is related to both continued economic sluggishness and the adverse impacts of further stock market declines on taxable income related to stock options and capital gains. We estimate that after plunging by nearly 66 percent in 2001, the income from gains and options will decline another 19 percent in 2002 before starting to rebound in 2003. In subsequent years, we project that the combination of an economic rebound and modest improvement in stock market-related income will boost PIT receipts.

We estimate that SUT receipts will total $22.4 billion in 2002-03, a 5.3 percent increase from 2001-02. We forecast that these receipts will grow further to $23.5 billion in 2003-04. Over the longer term, we forecast that SUT receipts will increase at an average annual rate of 6.6 percent between 2003-04 and 2007-08, reaching $30.5 billion by the end of the forecast period. This growth in SUT receipts is projected to be slightly less than our projected growth for statewide personal income for the period, reflecting a slight decline in the portion of income that is spent on taxable commodities.

A key determinant of sales tax receipts is

taxable sales. As indicted earlier in Figure 2, these

sales fell sharply beginning in the second half of

2001, and have only partially recovered in the first

three quarters of this year. On an average annual

basis, taxable sales were down by 0.7 percent in 2001

(reflecting softness in the second half of year),

and are expected to be down another 1.4 percent in

2002. As indicated in the shaded box, much of the

recent softness appears to be due to weak

business-related spending.

Looking ahead, we project that taxable sales

will accelerate, increasing by 3.9 percent in 2003

and 6.2 percent in 2004. Over the longer term, our

forecast assumes that taxable sales will increase

slightly slower than personal income. These increases

are somewhat subdued compared to what would normally be expected during a cyclical upturn. As

indicated in Chapter 2 , consumer spending on

automobiles and other durable goods has been

strong during the recent economic downturn. Because

of this, consumers at this point in time have less

capacity to take on new debt and have less "pent

up" demand than is normal for this stage of an

economic cycle. This, in turn, will constrain taxable

sales growth.

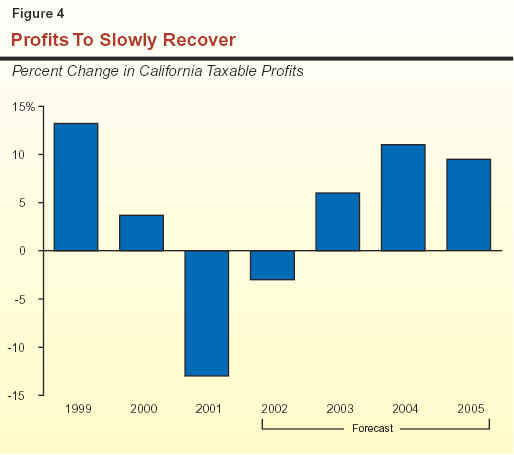

We estimate that CT receipts will increase from $5.6 billion in 2001-02 to $6.8 billion in 2002-03, before falling to $6.7 billion in 2003-04 and $6.5 billion in 2004-05. In the subsequent three years, we project that revenues from this source will increase at an average annual rate of 6.6 percent, reaching $7.9 billion by the end of the forecast period.

Corporation tax receipts in 2002-03 and beyond will be affected both by changes in California taxable corporate profits and by law changes enacted along with the 2002-03 budget. Specifically:

The remaining sources of income for the General Fund include various revenues other than from the PIT, SUT, and CT, as well as transfers to the General Fund from special funds. Included among the other revenues are taxes on insurance premiums, alcoholic beverages, and tobacco, as well as interest on pooled money investments. As shown earlier in Figure 1, we estimate that combined collections from all of these sources will fall from a peak of $12.8 billion in 2001-02, to $11.3 billion in 2002-03 and only $3.6 billion in 2003-04, before partly rebounding to $4.8 billion in 2007-08.

The total revenues from these other sources

depends on a variety of factors, including the

volume of insurance premiums written, alcoholic

beverage and tobacco sales, interest rates, and

the amount of General Fund resources available to

be invested. Our projections for these variables

reflect our underlying economic and demographic assumptions discussed in Chapter 2.

In addition, as noted above, numerous special factors also affect these revenue totals. These

include the electricity loan repayment in 2001-02,

the securitization of future tobacco settlement

receipts, and one-time loans and their associated repayments.

With regard to ongoing revenues in this category, our estimates assume moderate increases

in insurance taxes, stable receipts from alcoholic

beverage taxes, and declining receipts from

tobacco taxes. The estimates also take into account

the phase-out of California's estate tax resulting

from federal law changes enacted in 2001.

As discussed in Chapter 2, the economic forecast on which our revenue projections are based has certain risks that are concentrated on the downside direction. Should the state's economic growth fail to achieve the modest increases we are assuming, annual General Fund revenues could easily fall several billion dollars below what we are projecting. The shortfall would be greater if economic growth stalled out and even a mild downturn were to develop.

Weak Business Spending Behind Drop In Taxable SalesAlthough the plunge in PIT receipts has been the single most significant state revenue

development during the past two years, California taxable sales have also fallen sharply during

this period. This decline has adversely affected the state as well as local governments throughout California.

Although SUT receipts are most generally associated with

retail spending, approximately one-third of taxable sales are actually attributable to

business-to-business transactions. These

include purchases of computers, telecommunications equipment, and building materials that go into

the construction of new facilities. It is the softness in business spending that appears to be

primarily responsible for the recent decline in taxable sales.

The impact of declining business spending on taxable sales during the 2001 economic

downturn can be clearly seen in the detailed taxable sales data recently published by the Board

of Equalization for the third quarter of 2001 (the most recent quarterly data available). It

indicates that, during the 2000 to 2001 period, overall taxable sales fell by just under 3 percent.

However, the relative performance of different components of taxable sales was very different. In particular:

We believe that the trends evident in the 2001 taxable sales data—moderate consumer spending but declines in business-related sales—will persist until mid-2003, when business spending begins to improve. |

In this chapter, we discuss our General Fund expenditure estimates for 2001-02 and 2002-03, and our projections for 2003-04 through 2007-08, both in total and by program area. We first look at general budget trends during the forecast period, and then discuss in more detail our expenditure projections for individual major programs.

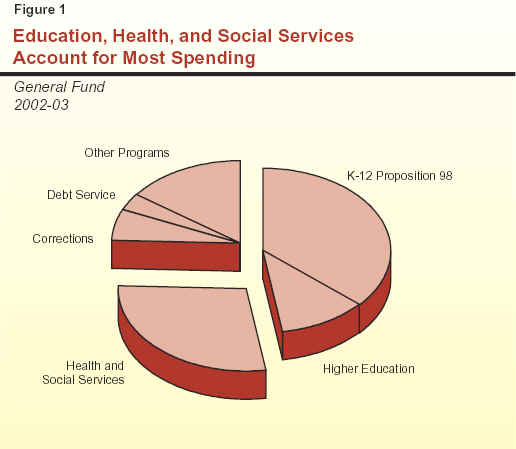

Figure 1 shows how General Fund spending is distributed among major program areas in 2002-03. It shows that education programs dominate state spending, accounting for nearly one-half of the General Fund total. About 37 percent is attributable to K-12 education, and another 11 percent is for higher education (which includes the University of California [UC], California State University [CSU], and California Community Colleges [CCC]). Just over one-fourth of the total is for health and social services, and about 6 percent is for corrections. The remainder is for state operations, debt service, various local subventions (including the vehicle license fee backfill), and other purposes.

Over the forecast period, we project that General Fund expenditures will increase at an average annual rate of 6.6 percent. This overall growth rate reflects divergent trends among major state programs. As indicated in Figure 2:

|

Figure 2 Projected General Fund

Spending for Major Programs |

||||||||||

|

(Dollars in Millions) |

||||||||||

|

|

Estimated |

|

Forecast |

Average

Annual Growth Over the Forecast Period |

||||||

|

2001-02 |

2002-03 |

|

2003-04 |

2004-05 |

2005-06 |

2006-07 |

2007-08 |

|||

|

Education programs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

K-12-Proposition 98 |

$26,806 |

$28,649 |

|

$29,398 |

$30,568 |

$32,309 |

$33,921 |

$35,316 |

4.3% |

|

|

Community Colleges-Proposition 98 |

2,579 |

2,814 |

|

2,832 |

2,989 |

3,194 |

3,422 |

3,659 |

5.4 |

|

|

CSU |

2,638 |

2,620 |

|

2,747 |

2,896 |

3,026 |

3,174 |

3,340 |

5.0 |

|

|

UC |

3,232 |

3,133 |

|

3,303 |

3,482 |

3,638 |

3,817 |

4,016 |

5.1 |

|

|

Health and Social Services |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Medi-Cal benefits |

$8,949 |

$9,782 |

|

$11,160 |

$12,075 |

$12,992 |

$13,863 |

$14,915 |

8.8 |

|

|

CalWORKs |

2,021 |

2,041 |

|

2,143 |

2,078 |

2,078 |

2,078 |

2,078 |

0.4 |

|

|

SSI/SSP |

2,807 |

3,060 |

|

3,420 |

3,566 |

3,750 |

3,960 |

4,182 |

6.4 |

|

|

IHSS |

887 |

1,009 |

|

1,106 |

1,217 |

1,337 |

1,440 |

1,550 |

9.0 |

|

|

Other major programs |

6,637 |

6,249 |

|

6,861 |

7,229 |

7,637 |

8,089 |

8,578 |

6.5 |

|

|

Department of Corrections |

4,657 |

4,700 |

|

4,848 |

5,093 |

5,363 |

5,677 |

5,849 |

4.5 |

|

|

Vehicle license fee

subventions |

2,460 |

3,789 |

|

3,888 |

4,065 |

4,308 |

4,565 |

4,838 |

5.0 |

|

|

Debt servicea |

2,954 |

2,571 |

|

2,907 |

4,190 |

4,646 |

5,159 |

5,589 |

16.8 |

|

|

Other programs/costs |

10,313 |

8,036 |

|

10,602 |

11,549 |

12,500 |

13,385 |

14,279 |

12.2 |

|

|

Totals |

$76,940 |

$78,453 |

|

$85,216 |

$90,996 |

$96,779 |

$102,551 |

$108,190 |

6.6% |

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Detail may not total due to rounding. |

||||||||||

|

a

Includes both general obligation and lease-revenue bonds for all

departments. |

||||||||||

State spending for K-14 education (K-12

schools and community colleges) is governed largely

by Proposition 98, passed by the voters in

1988. Proposition 98 sets the minimum amount the

state must provide for California's public K-12

education system and the CCC. Almost 80 percent of

total operations funding for K-14 education is

from the state General Fund and local property taxes,

pursuant to Proposition 98. The remainder is from

a variety of sources including federal funds,

lottery revenue, and other local revenues. California's

public K-12 education system consists of more than 1,000 locally governed school districts and

county offices of education serving about 6 million

K-12 students. In addition, these entities serve infants

and preschool students receiving child care, and

individuals in adult education programs. The CCC

provides instruction to about 1.7 million adults at

107 colleges operated by 72 locally governed districts.

The Spending Forecast. With the enactment

of the 2002-03 Budget Act, Proposition 98

appropriations exceeded the minimum guarantee by

$6 million. We now estimate that declining General

Fund revenues have lowered the 2002-03 minimum

guarantee by $1.9 billion. Because the 2002-03

appropriation level has not changed, we forecast that

the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee is now

over-appropriated by $1.9 billion.

For 2003-04, we estimate that

Proposition 98 will require the Legislature to allocate

approximately $2.2 billion, or 4.7 percent, more to

Proposition 98 programs than in 2002-03. Since we

estimate that over $1.4 billion of additional

property tax revenue will be allocated to school and

community college districts in 2003-04, the

General Fund increase would be $770 million (a

2.4 percent increase). In addition to the

$2.2 billion growth in the Proposition 98 guarantee, the

Legislature will have available $400 million of

funding in the Proposition 98 base that will be freed-up

for other K-14 priorities in 2003-04. This funding is

a result of spending deferrals that were made to

help address the state's budget problem (see

discussion in the nearby shaded box). For the forecast

period, we estimate that growth in total

Proposition 98 spending (General Fund and local property

taxes) for K-14 education will average 5.4 percent

annually (see Figure 3). This growth rate is lower

than the rate currently projected for 2002-03

(7.6 percent), but higher than the growth rate in

2001-02 (0.7 percent).

Figure 3 The LAO Proposition 98

Forecast 2002-03 2003-04 2004-05 2005-06 2006-07 2007-08 Proposition 98 (In

Billions)a K-12 $41.6 $43.6 $45.9 $48.6 $51.4 $54.0 Community

Colleges 4.8 5.0 5.4 5.7 6.1 6.6 Totals $46.5b $48.7c $51.2d $54.4 $57.5 $60.5 Community Colleges share of guarantee 10.4% 10.4% 10.5% 10.5% 10.7% 10.8% Proposition 98

�Test� 2 2 2 2 2 2 Annual

Percentage Change State

population 1.7% 1.5% 1.5% 1.5% 1.5% 1.5% K-12

average daily attendance 1.4 1.0 0.8 0.8 0.4 0.2 Per

capita personal income -1.3 2.1 3.4 5.3 5.4 5.1 Total

guarantee 7.6 4.7 5.2 6.1 5.8 5.3 General

Fund 7.0 2.4 4.1 5.8 5.2 4.4 Local

property taxes 8.7 9.6 7.4 6.8 7.0 7.0 a

Includes local property tax revenues. b

Assumes restoration of $3.2 billion of "maintenance

factor." c

Assumes restoration of $700 million of maintenance factor. d

Assumes over-appropriation of $428 million to fund Proposition

49. Detail may not add to total due to rounding.

Key Forecast Factors. General Fund

expenditures for Proposition 98 depend on a variety of

factors—including K-12 average daily attendance (ADA),

per capita personal income, per capita General

Fund revenues, and local property taxes. For our

forecast:

Figure 3 summarizes our assumptions for these factors and identifies the annual changes in the guarantee that result.

Commitment to Over-Appropriate Proposition 98. In addition to the above factors, our forecast also accounts for statutory commitments to over-appropriate the minimum guarantee in 2003-04. Chapter 1167, Statutes of 2002 (AB 2781, Oropeza), requires the state to restore any "maintenance factor" in 2003-04 regardless of what the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee would require. (A maintenance factor is created in years where General Fund revenues grow more slowly than the economy. We estimate that the state will have a maintenance factor of $700 million in 2003-04.) Our forecast suggests that General Fund revenues will grow at roughly the same rate as the economy in 2003-04. As a result, Proposition 98 would not require any of the $700 million maintenance factor to be restored. Thus the statutory requirement to restore all of the maintenance factor would result in an over-appropriation of $700 million in 2003-04. In addition, Chapter 1167 requires the state to provide an additional $79 million over-appropriation related to the prior-year's deferrals. The over-appropriation of almost $780 million would become part of the Proposition 98 base—making the increase permanent.

Impact of Proposition 49. Our forecast

also assumes that the recent passage of

Proposition 49—the After School Education

and Safety Program—will require the state to

over-appropriate the minimum guarantee in 2004-05 by

up to $428 million under certain conditions. The

initiative requires the state to over-appropriate

Proposition 98 by the difference between

$550 million and the 2003-04 appropriation for the program.

If the 2002-03 appropriation level of $122 million

is continued into 2003-04, then the state will be

required to over-appropriate Proposition 98

by $428 million in 2004-05. The Legislature and

Governor, however, could decide to increase

funding for the before and after school program in

2003-04. Given the growth in the Proposition 98

minimum guarantee in

2003-04 and the net impact of deferrals, there

will be over $1 billion available—beyond growth

and COLA—for expansion of existing programs

and/or funding for some new programs in 2003-04. Thus, the state could choose to fund part or all

of the required Proposition 49 expansion within the 2003-04 minimum guarantee.

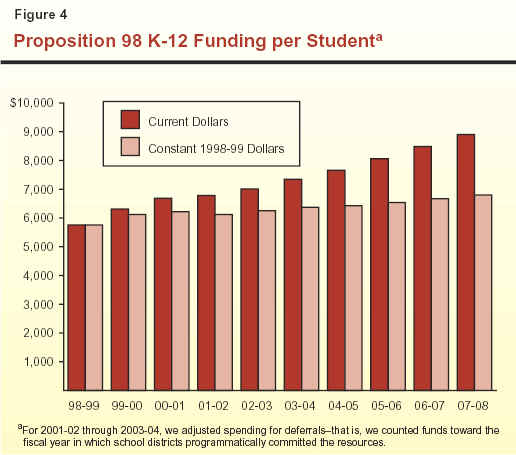

K-12 Funding Projections. Figure 4 displays our projected K-12 per-pupil spending levels (in both "current" and inflation-adjusted dollars). These estimates are derived from our Proposition 98 forecast and are adjusted for funding deferrals between years. (That is, we counted the spending toward the fiscal year in which school districts had programmatically committed the resources.) The estimates reflect real (that is, inflation adjusted) per-pupil increases averaging 1.7 percent annually over the forecast period. These additional resources—averaging over $750 million each year after 2002-03—would permit expansion of existing programs and/or funding for some new programs.

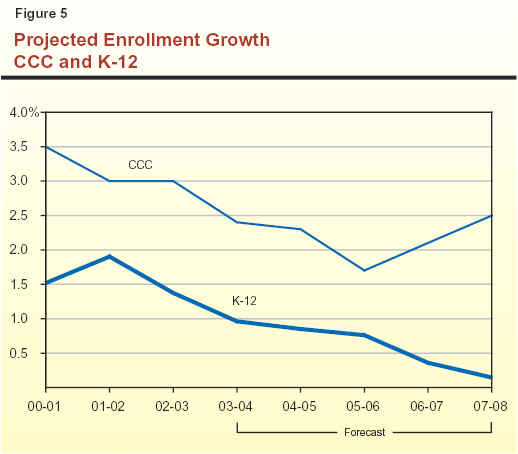

Community College Funding Projections. Based on our Proposition 98 projections, we estimate total CCC funding would increase by about 6.3 percent per year over the forecast period. To forecast the CCC's share of Proposition 98, we assumed that both CCC and K-12 would receive statutorily required growth and COLA each year. We assumed that growth in Proposition 98 funds in excess of growth and COLA would be distributed based on the historic K-12 and CCC split. The resulting forecast projects a gradual increase in CCC's share of Proposition 98 spending from 10.4 percent in 2002-03 to 10.8 percent in 2007-08. As shown in Figure 5, the increase in CCC's share of Proposition 98 funds is due to CCC's enrollment growth rate exceeding K-12's over the forecast period.

2002-03 Deferrals "Free-Up" Over $400 Million in 2003-04As part of the solution to the 2002-03 budget problem, the Governor and Legislature deferred $1.1 billion of Proposition 98 spending from 2001-02 to 2002-03. Instead of receiving $1.1 billion in categorical funding in the late spring of 2002, schools received the funding in summer 2002. The deferral had no programmatic impact on school districts, although some districts may have experienced cash-flow and accounting difficulties as a result of the delay. A second component of the 2002-03 budget solution was to defer $681 million of Proposition 98 funding from 2002-03 to 2003-04. Since the deferrals are one-time costs and the level of deferral paid in 2002-03 ($1.1 billion) is larger than the deferral required to be paid in 2003-04 ($681 million), the Legislature will have over $400 million in resources available for other Proposition 98 priorities in 2003-04. |

In addition to community colleges, the

state's public higher education system includes the

UC and the CSU. The UC consists of eight general

campuses, one health science campus, numerous special research facilities, and a planned tenth

campus in Merced. The UC awards bachelor's, master's,

and doctoral degrees, as well as various professional

degrees. The UC has primary jurisdiction over

public university research. The CSU consists of 23

campuses and several off-campus centers. The CSU

grants bachelor's and master's degrees and may award

doctoral degrees jointly with UC or a private university.

The Spending Forecast. We estimate that

spending for UC and CSU (excluding funding for

capital outlay and debt service) will increase from

$5.8 billion in 2002-03 to $6.1 billion in 2003-04, or

by 4.9 percent. By 2007-08, we estimate that

spending for UC and CSU will increase to $7.3 billion,

reflecting annual increases of about 5 percent.

Key Forecast Factors. For 2003-04 and

subsequent fiscal years, we assume that UC and CSU will

receive base budget increases equivalent to the growth in inflation and enrollments. Over the

forecast period, inflation is projected to average

roughly 3 percent annually. With regard to

enrollment growth, the Master Plan calls for UC and CSU

to draw from a fixed eligibility pool (12.5 percent

and 33.3 percent, respectively) of high school

graduates. The main component of enrollment

growth, therefore, is growth in the number of high

school graduates. This population is expected to grow at

a modest rate of 1 percent to 2 percent annually

over the forecast period. We expect the rate of

college enrollment will be somewhat higher than this,

however, for three reasons. First, the state continues

to conduct outreach and similar activities to

encourage increased college participation by

targeted groups. Second, the recent expansion of

financial aid programs, including the guaranteeing of

Cal Grants to qualified high school graduates, is

subsidizing the cost of college attendance for an

increasing number of students. Third, the declining real

cost of higher education fees (which have not been

increased for eight years) provides an added fiscal

incentive for college attendance.

Cal Grant Increases. Chapter 403, Statutes

of 2000 (SB 1644, Ortiz), made Cal Grant awards an entitlement for every

qualified graduating high school senior. There is still

uncertainty as to the fiscal impact of the new

entitlement program. This is because it is unclear how students

and their families will respond to the changes in Cal

Grant policies. Based on information from the Student

Aid Commission, however, we project that annual

total Cal Grant expenditures could exceed

$1.5 billion by 2007-08.

The 2001-02 budget plan established a new

special fund, the Tobacco Settlement Fund, which

is made up of revenues received by the state from

the settlement of tobacco-related litigation. The law

creating the fund initially required that, after

2001-02, all revenues from this source be deposited in the

fund for the support of various specified health

programs. However, under more recent legislation, this

revenue stream was sold to investors (securitized)

to provide funds to support overall state

expenditures in 2002-03. Because tobacco settlement receipts will

be used to retire this debt for the foreseeable future,

little if any of these funds will be available in 2003-04

and subsequent years for the support of health programs.

The Spending Forecast. This forecast assumes

that the cost of these programs—estimated to

be $546 million in 2002-03—shifts to the state

General Fund. The specific health programs affected by

such funding shifts include Medi-Cal, public health

programs such as the Child Health and Disability

Prevention and prostate cancer treatment programs,

and Healthy Families insurance coverage for children.

The Medi-Cal Program (the federal

Medicaid program in California) provides health care

services to recipients of CalWORKs or SSI/SSP

grants, and other low-income persons who meet the program's eligibility criteria (primarily

families with children and the elderly, blind, or

disabled). The state and federal governments share most of

the program costs on a roughly equal basis.

The Spending Forecast. We estimate that

General Fund spending for Medi-Cal local assistance

(including benefits, administration, and other

costs) will be nearly $10.4 billion in the current year,

about a $600 million increase over the amount

appropriated in the 2002-03 Budget

Act. We project that, barring other actions by the Legislature and

Governor, General Fund support for the program would

grow to $11.8 billion in 2003-04, a 13.6 percent

increase from current-year expenditures. By the end of

the forecast period in 2007-08, we estimate that

General Fund spending for Medi-Cal will reach

$15.7 billion, an average annual increase of 8.5 percent over

the projection period.

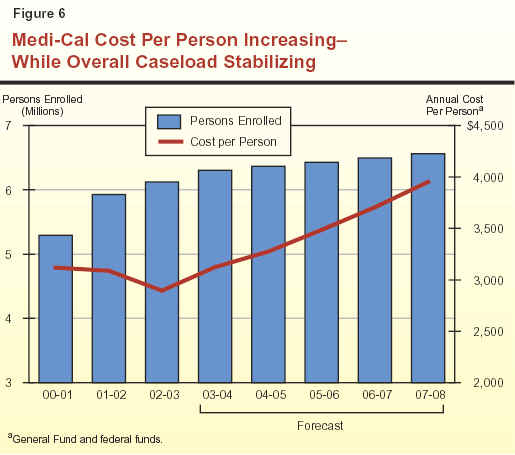

Key Forecast Factors. Several factors play a

significant role in our forecast:

The Healthy Families Program implements

the federal State Children's Health Insurance

Program, enacted in 1997. Funding generally is on a

two-to-one federal/state matching basis. The program

offers health insurance to eligible children in

families with incomes below 250 percent of the federal

poverty level. Families pay a relatively low monthly premium and are offered coverage similar to that available to state employees.

The state has received federal approval to

expand Healthy Families coverage to eligible parents in

families with incomes below 200 percent of the

federal poverty level. However, the Governor vetoed

funding that had been included in the 2002-03 budget

to commence the expansion in October 2002 because of the state's ongoing

fiscal problems.

The Spending Forecast. We estimate that

overall state spending for the Healthy Families

Program will exceed $260 million in 2002-03, about the

same amount of funding as provided in the 2002-03

Budget Act. About $21 million in support would be

provided from the General Fund, with the balance

in state funding during this period coming from

the Tobacco Settlement Fund.

We further estimate that overall state spending for the program will

increase about 14 percent in 2003-04 to about $300 million, and that by

2007-08 the program will have an annual cost of

about $390 million. The forecast assumes that all

$300 million in state support for the program

commencing in 2003-04 comes from the General Fund.

Key Forecast Factors. The significant increase

in General Fund resources for the program in 2003-04 is the result of the anticipated loss of

program support from the Tobacco Settlement Fund. The forecast assumes that the expansion of the

program to parents does not occur during the

projection period. The growth in the program is based

on the assumption that the caseload of children in Healthy Families continues to grow, although

not as quickly as in previous years, as the

program reaches a larger proportion of the eligible

population. Specifically, we assume that the program,

which had about 570,000 children enrolled as of July

2002, will reach an enrollment of almost 700,000

children by June 2008. The forecast assumes continued

increases in the cost of medical coverage.

The Lanterman Developmental Disabilities

Services Act of 1969 entitles individuals with

developmental disabilities to a variety of services,

which are overseen by the DDS. Individuals with

developmental disabilities have been diagnosed with

mental retardation, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, autism,

or other similar disabling conditions. The DDS

operates five Developmental Centers (DCs) and two smaller facilities which provide 24-hour

institutional care, and contracts with 21 Regional Centers

(RCs) to coordinate and deliver community-based services.

The Spending Forecast. We estimate that

General Fund spending for developmental services

in 2002-03 will total $1.8 billion, the same amount

of funding appropriated in the 2002-03 Budget

Act. Of that total, nearly $1.5 billion will be spent

by RCs for community services and about

$332 million will be spent for operating the DCs.

We further estimate that General Fund spending for developmental services will grow by

about 9 percent in 2003-04 to nearly $2 billion. By

2007-08, we estimate that General Fund spending for

this program will grow by $1 billion and reach

$2.8 billion. This expenditure growth is due almost

entirely to the RCs. We estimate that spending for

DCs will remain relatively flat over the forecast period.

Key Forecast Factors. Our forecast of

significant growth in RC spending reflects historical

increases both in caseload and in the average cost of

serving each RC client. Specifically, our forecast

assumes that RC caseloads will continue to grow at an

annual average rate of 5.4 percent and that costs

will continue to grow at an annual average rate of 5.9 percent.

In response to federal welfare reform

legislation, the Legislature created the CalWORKs program

in 1997. This program provides cash grants and welfare-to-work services to families with children

whose incomes are not adequate to meet their basic needs.

The Spending Forecast. General Fund

spending in 2002-03 for the CalWORKs program is

estimated to be $2 billion, an increase of 1 percent over

the prior year. In 2003-04, spending is projected to

increase by 5 percent, to $2.1 billion. We

project spending to decrease by 3 percent in 2004-05,

and then remain stable through the remainder of

the forecast period. The projected year-over-year

spending changes result from (1) satisfying the

remaining state match obligation for the federal

Welfare-to-Work program in 2003-04 and (2) replacing

lower maintenance-of-effort (MOE)-countable

spending in other programs with additional General

Fund spending within CalWORKs. Continued caseload decline projected through the forecast period

enables the state to maintain spending at the

federal MOE floor.

Key Forecast Factors. Our CalWORKs

spending projection is based on several factors, the most

important being our caseload projections

(discussed below). In addition, we assume that California

will meet the $2.7 billion MOE spending requirement

by counting about $650 million being spent in

other programs. Finally, we assume that the

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block

grant will be reauthorized at its current $3.7 billion

annual level for California.

Unanticipated Caseload Declines Relieve CalWORKs Funding

Pressures. Contrary to 2002-03 Budget Act assumptions, the caseload

decreased in 2001-02, and we project caseloads to

decline further in the current year. (We discuss

caseload trends below.) We project that these

unanticipated caseload declines, as well as continued annual

declines through 2005-06, will result in program

savings and sufficient TANF carryover funds to

enable the state to maintain General Fund spending at

the MOE floor while providing the statutory COLA

and inflation adjustments for employment services

and child care throughout the forecast period.

Sensitivity to Caseload Projections.

Our spending forecast is driven largely by our caseload

projections, and relatively modest caseload movement

in either direction could result in significant

program costs or savings. If the caseload were to remain

stable in 2003-04 and beyond, rather than decreasing

as projected, we estimate that federal carryover

savings would be exhausted in 2004-05. Fully

funding the program in that year would require

General Fund expenditures of approximately

$300 million above the MOE floor. By 2007-08, fully funding

the program would require spending over

$1 billion above the MOE floor.

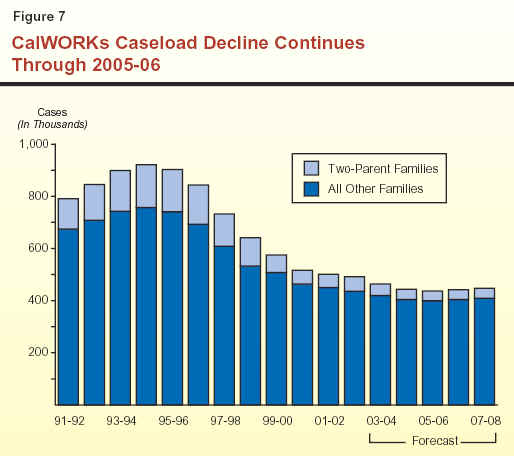

Caseload Trends and Projections. From

1994-95 through 2001-02, the CalWORKs caseload

declined by 46 percent. As shown in Figure 7, we believe the decline will continue, due to

economic and demographic trends (primarily lower

birth rates). Specifically, we project a 2 percent

decline in 2002-03 and a decline of 5 percent in

2003-04, followed by lower declines of 4 percent and

1 percent in 2004-05 and 2005-06, respectively. This

is followed by caseload increases of about

1 percent in both 2006-07 and 2007-08. Our projections

are based on a trend analysis of caseloads, birth

rates, grant levels, and unemployment rates.

The SSI/SSP provides cash assistance to

eligible aged, blind, and disabled persons. The SSI

component is federally funded and the SSP component

is state funded.

The Spending Forecast. General Fund

spending for SSP is estimated to be about $3.1 billion in 2002-03, an increase of 9 percent over the prior

year. For 2003-04, we project an increase of

12 percent, raising total expenditures to $3.4 billion. We

project that from 2004-05 through the end of the

forecast period, spending for SSP will increase by an

annual average of 5.2 percent, eventually reaching a

total of $4.2 billion.

Key Forecast Factors. The 2002-03 Budget

Act delayed the January 2003 COLA until June 2003.

The current-year COLA cost of $24 million results in

annual incremental costs of about $267 million

(representing 11 new months of costs) in 2003-04.

For the remainder of the forecast period, the two

primary components of projected cost increases are (1) annual caseload growth of about 2.2 percent

and (2) providing the statutory January COLA. In 2002-03, caseload growth and COLA result in additional costs of $93 million. In 2003-04 and

subsequent years, annual caseload costs average

about $70 million, and the cost of providing the

COLA ranges from $70 million to $120 million,

depending on the California Necessities Index and the

amount of the federal SSI COLA, which is based on the

Consumer Price Index.

Caseload Trends and Projections. During the

late 1980s and early 1990s, the caseload grew

rapidly, with most of the growth in the disabled

component of the caseload. In the mid-to-late 1990s,

the caseload leveled off and actually declined in

1997-98, in part due to federal policy changes which

restricted eligibility. Since March 1998, the

caseload has been growing at a steady rate of

about 2.2 percent per year. We expect this growth rate

to continue throughout the forecast period.

The IHSS program provides various

services to eligible aged, blind, and disabled persons who

are unable to remain safely in their own homes

without such assistance.

The Spending Forecast. General Fund

spending for IHSS is projected to be about $1 billion in 2002-03, an increase of 14 percent over the

prior year. For 2003-04 we project that costs will

increase by 10 percent. This rate of spending growth will

continue for the next two fiscal years and then fall

to about 8 percent in the final two years of our

forecast, resulting in total expenditures of

$1.6 billion in 2007-08.

Key Forecast Factors. Our forecast assumes

that costs will increase 7.5 percent each year due

to caseload growth and increases in the hours of

service provided to recipients. Recent legislation

authorizing state participation in health benefits

and wage increases for certain IHSS workers will

increase annual costs by an additional $78 million

over the forecast period.

The major state judiciary and criminal justice programs include support for four agencies in the executive branch—the California Department of Corrections (CDC), Department of the Youth Authority, the Department of Justice, and the Office of Criminal Justice Planning—as well as expenditures for local trial courts and state appellate courts. The largest expenditure program—the CDC—is discussed in more detail below.

The CDC is responsible for the

incarceration and care of adult felons and nonfelon

narcotics addicts at 33 state prisons. The CDC also

supervises and provides services to parolees released

to the community.

The Spending Forecast. General Fund

support for CDC is forecast to grow by about

$190 million from 2001-02 to 2003-04, reaching about

$4.8 billion at the end of that period. Expenditures for

CDC are forecast at about $5.8 billion by 2007-08.

(This includes adjustments for employee

compensation increases, but does not include General Fund

support for capital outlay and debt service, which

are accounted for elsewhere in our projections.)

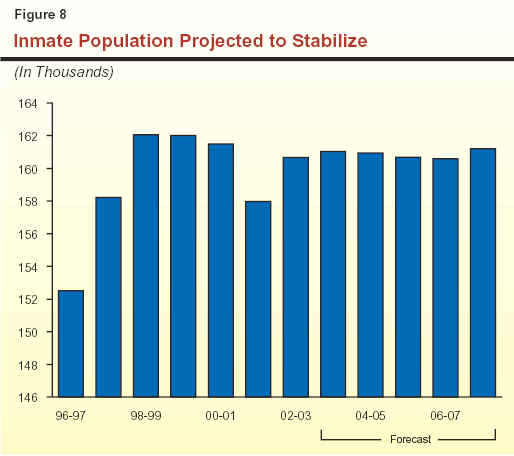

The projected growth in adult correctional expenditures continues a trend of steadily