August 27,2002

In an effort to determine the extent to which racial disparity is a factor in traffic enforcement, many law enforcement agencies in California have begun collecting traffic-stop data. In this report, we discuss many of the issues concerning the collection and analysis of these data. We analyze the data collected from the California Highway Patrol and a number of local departments. We recommend a number of changes for racial profiling data collection, analysis, and training in the state in order to improve their effectiveness.

Over the past several years, the use of race by law enforcement agencies in their policing activities has received considerable attention across the country. The controversy regarding "racial profiling" has centered on police departments' practices related to traffic stops—examining whether police have targeted drivers on the basis of their race or ethnicity. Significant anecdotal evidence has suggested that some departments may be treating drivers of some races or ethnicities differently than white drivers. In an effort to determine the extent to which race is a factor in police stops, many departments have begun collecting traffic-stop data. These data collection efforts typically involve recording the race of each driver stopped. The racial mix of the traffic stops is then compared to a "benchmark"—often the racial mix of the jurisdiction's overall population—in order to determine if drivers of particular races are disproportionately stopped by law enforcement.

In response to these concerns, the Legislature enacted Chapter 684, Statutes of 2000

(SB 1102, Murray). Chapter 684:

Chapter 684 directs the Legislative Analyst's Office to evaluate (1) the data voluntarily collected by police departments in California regarding racial profiling and (2) the value of the new required training.

In preparing this report, we have reviewed national reports and data from California law enforcement agencies. We also consulted with representatives from local law enforcement, relevant state agencies, and civil rights organizations. This report begins with a discussion of key racial profiling issues—national studies on the topic, definitions, and tradeoffs inherent in data collection. We then evaluate the data-collection efforts in California. Finally, we review the implementation of the training course required by Chapter 684.

As concerns about racial profiling have been raised around the country, several organizations have prepared reports on the subject. In order to provide an overview of the current landscape on racial profiling, we discuss below a number of these reports which focus on data-collection and analysis issues. In short, these national studies reflect the difficulty for all interested perspectives (law enforcement, local communities, government, and academia) in finding a mutually acceptable methodology for analyzing and explaining race data collected by police departments. Later in this analysis, we review reports pertaining to selected law enforcement agencies in California.

General Accounting Office (GAO) Report. Congress's GAO released a report in March 2000 entitled Racial Profiling: Limited Data Available on Motorist Stops which reviewed five quantitative racial profiling analyses available at that time. In its review, the GAO found that minority drivers were more likely to be stopped by police in comparison to their overall representation in the populations to which they were compared. The GAO concluded, however, that these studies "have not provided conclusive empirical data from a social science standpoint to determine the extent to which racial profiling may occur." The GAO found that the reports failed to "fully examine whether different groups may have been at different levels of risk for being stopped" (due to the rate and severity of traffic violations committed) and the reports did not sufficiently rule out factors other than race to explain the differences. In other words, the reports' benchmarks did not adequately establish whether there is variation among racial and ethnic groups' actual violations of traffic laws and the rates at which they are stopped by law enforcement personnel.

Bureau of Justice Statistics Report. As part of a national survey of police-public contacts, the U.S. Department of Justice's (U.S. DOJ) Characteristics of Drivers Stopped by Police, 1999 found that on a national level, black drivers were somewhat more likely than white drivers to be stopped. On the other hand, Hispanic drivers were less likely than either black or white drivers to be stopped. The report did not attempt to draw any conclusions regarding profiling and stated, "To form evidence of racial profiling, the survey would have to show (all other things being equal)—blacks and/or Hispanics were no more likely than whites to violate traffic laws, and police pulled over blacks and/or Hispanics at a higher rate than whites. Because the survey has information only on how often persons of different races are stopped, not on how often they actually break traffic laws, analysis of data from the 1999 Police-Public Contact Survey cannot determine whether or to what extent racial profiling exists."

U.S. DOJ Report. In response to

many police departments beginning racial profiling data-collection projects, the U.S. DOJ released

A Resource Guide on Racial Profiling Data Collection Systems

in November 2000. The resource guide provides recommendations

to police departments opting to begin a data collection process. Among its

recommendations are to convene a community task force

to determine a city's data needs and develop a relationship with an academic or

research partner to perform data analysis. In seeking

to develop appropriate benchmarks for which to compare the racial demographics of

traffic stops, the report concludes: "More research

is needed to determine the most useful way to analyze data on stops and searches. By

experimenting with various benchmark comparisons, practical methods can be designed."

Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) Report. The PERF released Racially Biased Policing: A Principled Response in 2001. The report provides guidance to police departments undertaking data-collection projects, including data element recommendations and suggestions on data analysis. The report did not make any recommendations on establishing comparative benchmarks, but PERF plans to release a best practices report on data analysis methodologies later in 2002. In addition to data issues, the study stresses the importance of making changes in department accountability, policies, hiring, training, and community outreach to address police race issues.

The debate over racial profiling has been complicated by parties using multiple definitions. Variation among these definitions means that interested parties are often discussing different types of police practices, behavior, and stops. As such, proposals to prohibit racial profiling would prevent a range of police activities depending on which definition was used.

Federal Constitutional Protections. The 4th (unreasonable searches and seizures) and 14th (equal protection of the laws) amendments of the U.S. Constitution provide a framework for the protection of drivers from indiscriminately being targeted by the police in traffic stops. In moving to define and outlaw racial profiling practices, state legislatures have needed to consider whether they intend to (1) specifically ban police behavior which is already unconstitutional under federal law or (2) provide additional protections which go beyond existing federal law.

California State Law. Chapter 684 prohibits law enforcement officers in California from engaging in racial profiling. Chapter 684 defines racial profiling as "the practice of detaining a suspect based on a broad set of criteria which casts suspicion on an entire class of people without any individualized suspicion of the particular person being stopped."

Wide Spectrum of Other Definitions in Use. In addition to the definition specified in state law, a number of California law enforcement agencies have developed their own working definitions. Likewise, the U.S. DOJ's Resource Guide, PERF, and other organizations have set forth their own definitions. Figure 1 presents a number of these definitions. No consensus on an appropriate definition has emerged. The definitions reflect a continuum in the degree to which they would restrict law enforcement activities. The debates over definition typically center on a few key issues:

|

Figure 1 Various Racial Profiling

Definitions |

|

|

|

Chapter 684, Statutes of 2000 (SB 1102,

Murray) |

|

·

“‘Racial profiling,’ for purposes of this section,

is the practice of detaining a suspect based on a broad set of criteria

which casts suspicion on an entire class of people without any

individualized suspicion of the particular person being stopped.” |

|

California Highway Patrol |

|

·

“‘Racial profiling’ is defined for this report as

occurring when a police officer initiates a traffic or investigative

contact based primarily on the race/ethnicity of the individual.” |

|

U.S. Department of Justice Resources Guide on

Racial Profiling |

|

·

“For this guide, racial profiling is defined as any

police-initiated action that relies on the race, ethnicity, or national

origin rather than the behavior of an individual or information that

leads the police to a particular individual who has been identified as

being, or having been, engaged in criminal activity.” |

|

Police Executive Research Forum |

|

·

“‘Racially biased policing’ occurs when law

enforcement inappropriately considers race or ethnicity when deciding

with whom and how to intervene in an enforcement capacity.” |

|

City of San Jose |

|

·

“Racial profiling during traffic stops occurs when a

police officer initiates a traffic stop solely upon the race of the

driver of a motor vehicle.” |

|

American Civil Liberties Union |

|

·

“Racial profiling is the use of race by law enforcement

in any fashion and to any degree when making decisions about whom to

stop, interrogate, search, or arrest—except where there is a specific

suspect description.” |

Current State Definition Needs Improvement. Our review of Chapter 684's definition of racial profiling found that it lacks specificity. It seems to reflect the Legislature's interest in applying a prohibition of profiling to all police activity (rather than traffic stops alone). Yet, the definition is vague in terms of what is meant by a "broad set of criteria." Furthermore, the definition does not explicitly use the term race—leaving open whether it is intended to prevent profiling based on gender, age, or other characteristics. In our research, we found that a number of practitioners resisted using the state definition due to its vagueness. Consequently, we recommend that the Legislature revisit its definition of racial profiling and develop one which more explicitly defines what activities are acceptable under state law.

Choosing an Appropriate Definition. In developing a more explicit definition, the Legislature should ensure that it meets a number of criteria.

In order to determine whether their officers engage in racial profiling, many law enforcement departments in California have chosen to develop data collection systems. Some departments have integrated their data collection systems with increased training and management oversight. When departments consider undertaking a race-based data collection project, they must consider a number of factors. Below, we discuss the potential benefits and drawbacks that departments must consider. Based on our review of departments' experiences with data collection, we found that the benefits from data collection have tended to exceed the drawbacks, as discussed below. At the same time, each department must evaluate their specific circumstances. For agencies which have had no community complaints and/or already closely monitor officer behavior in other ways, undertaking race-based data collection may not be the most efficient use of resources.

Based on our review of departments' experiences with data collection, we discuss a number of potential benefits below.

Determining If a Problem Exists and, If So, Seeking Solutions. In most cases, the primary purpose of undertaking data collection will be to determine whether racial disparities in police activity exist and, if so, why. Identifying any problems would then allow a department to begin searching for solutions.

Due to the high number of traffic stops conducted in most jurisdictions, analyzing data on a departmentwide level would not likely provide information regarding the conduct of specific officers. Instead, for those departments which either formally or informally connect their data collection with individual officers or units, they may be able to identify outliers from typical officer behavior. Departments may then be able to learn any reason for the outliers and take any necessary corrective actions.

Improved Community Relations. A number of departments have begun data collection after concerns were raised by the public regarding police practices. According to a number of departments, the willingness to collect data has helped to improve their relationship with the public.

Improved Management of Resources. Some agencies that have undertaken data collection projects have discovered that the data gathered can be informative to the management of officer resources and behavior. For those departments, they often learn new information about what types of stops and searches their officers are making. Management can then decide if these practices are the most efficient allocation of department resources.

Legal Protection. Some departments across the country have been accused in lawsuits of engaging in racial profiling. Without the collection of their own data, departments can have a difficult time in court defending their practices. At the same time, some departments have expressed concerns that any data that they do collect could be used against them in court.

Despite the benefits discussed above, some departments have encountered drawbacks from data collection.

Lack of Definitive Answers. Simply

collecting race-based data does not help a

department answer questions about its practices. Instead,

it must then arrange for the analysis of the data—

to seek explanations of the data's meaning. As discussed in more detail below, this

analysis process often leads to more questions

than answers, which can be frustrating for both

the police and the community.

Potential for Reduced Enforcement. Some critics of data collection have argued that if officers believe they are being monitored, they will "disengage" from police activity. That is, officers would selectively reduce their traffic stops in order to avoid any behavior which might be perceived as racially biased.

Increased Costs. In most cases, departments will experience some up-front costs for establishing the data collection system and then ongoing costs for data entry and analysis. Some departments have been able to integrate their race-based data collection with existing systems—substantially reducing their up-front costs.

If a department chooses to begin data collection, it typically faces a number of challenges in implementing an effective system. Below, based on department experiences and the national reports described above, we review the most important considerations for those departments implementing a data collection system for racial profiling purposes.

Time Concerns of Officers. Police officers complete a wide variety of paperwork for their daily traffic stops. Adding additional requirements has the potential to slow officers down and limit their ability to move onto their next activity. There is a tradeoff, therefore, that departments must make between choosing a data collection method which is quick to use and which collects thorough data.

Accuracy of Data Collection. Data collection systems rely on officers to accurately report the data from their stops. It is important to implement systems to oversee and double-check the data collection to ensure the reliability of the data recorded.

Type of Contacts. As noted above, one of the major differences in the various definitions of racial profiling concerns the types of police activities covered. Departments must make a similar choice governing the types of police activities covered by their data collection system. While tracking all traffic stops (including those leading only to a verbal warning) has become generally accepted as the minimum information that should be collected, some departments have opted to cover all their contacts with the public, including pedestrian interactions. The choice of what type of police activities to cover should match the definition in use by the department.

Data Elements. One of the most difficult implementation decisions that departments face is choosing which data elements to require their officers to record. Additional data elements yield more information and insight into department practices, but also require additional time for collection and analysis. Major data categories include the location of the stop, residency and demographic characteristics of the driver, reason for the stop, disposition of the stop, length of the stop, whether a search was conducted, what type of search, and the results of the search. Figure 2 shows the data elements that both the U.S. DOJ Resource Guide and PERF recommend that law enforcement agencies collect.

|

Figure 2 Traffic Stop Data Elements |

|

|

|

Basic Stop Information |

|

·

Date. ·

Time. ·

Location. ·

Length of stop. ·

Identity of officer. |

|

Identity of Individual Stopped |

|

·

Race and ethnicity. ·

Age. ·

Gender. |

|

Type of Stop |

|

·

Reason for the stop. ·

Outcome of the stop. |

|

Search Information |

|

·

Whether search was performed. ·

Legal basis for search. ·

What was searched. ·

Whether contraband was found. ·

Description of any property seized. |

|

a

Elements recommended by both the U.S. Department of Justice and

Police Executive Research Forum. |

Community Task Forces. A number of departments across the country have had considerable success using a community task force of public members to help develop and oversee their race-based data collection system. These task forces can help ensure that the project will address specific concerns of the community and improve the working relationship between the police and the public.

Officer-Specific Data. Connecting data on traffic stops with the officer that performed that stop allows a department to have a more complete picture of an officer's activities and identify any outliers from standard department practices. Yet, due to officer resistance, many departments have opted to not link their data collection with an officer's identity. For those departments opting for officer confidentiality, maintaining data at the unit or shift level still protects confidentiality while allowing more sophisticated data analysis than would be possible with departmentwide data.

In 1999, the Legislature approved SB 78 (Murray) which directed CHP and local law enforcement agencies to begin collecting data on the race or ethnicity of all motorists stopped for traffic enforcement or investigation. The Governor vetoed the bill but directed CHP to begin collecting race, gender, and age data from all traffic stops made by its officers from 2000 through 2002 and to submit its findings to the Governor and Legislature in three annual reports.

While the Governor issued his directive in September 1999, CHP actually began collecting demographic data on its "public contacts" two months earlier in July 1999. Public contacts include all stops by CHP officers in order to conduct physical arrests, issue citations, provide verbal warnings, or provide nonenforcement services to motorists.

The CHP defined racial profiling as occurring when an officer initiates a traffic or investigative contact based primarily on the race or ethnicity of the individual. In October 1999, CHP expanded its data collection to track not only the demographic characteristics of its public contacts but also the outcome of each contact.

In July 2000, CHP issued a report that summarized data on more than 2.6 million contacts between its approximately 5,900 uniformed officers and members of the public between July 1999 and April 2000. The categories of contacts included 2.1 million "enforcement contacts" in which officers stopped motorists who were suspected of violating laws or regulations, 470,000 stops to provide motorist services unrelated to law enforcement (such as providing information or assisting the driver of a disabled vehicle), and almost 32,000 cases in which officers responded to collisions.

The CHP data showed that both blacks and whites represented larger proportions of CHP's public contacts than their shares of the state's population. Motorists of Asian and Hispanic descent accounted for smaller proportions of the CHP's contacts than their representation in the general population. For example, the report indicated that blacks represented about 7 percent of the state's population and 8 percent each of CHP's enforcement contacts, motorist services, and collisions. Hispanics represented 30 percent of the population and 26 percent of CHP enforcement contacts and motorist service contacts.

The report concluded that because CHP officers provided positive services (motorist services and collision assistance) to blacks in the same proportion as enforcement contacts, CHP officers do not employ race or ethnicity as a basis for enforcement stops and do not engage in racial profiling. However, as discussed below, our review indicates that the data are inconclusive.

Despite the large number of contacts covered by the CHP report, the analysis of the data collected is minimal and incomplete. Specifically, the report presents only statewide aggregate totals on the race or ethnicity of CHP contacts and does not offer an explanation as to why the demographic makeup of both its enforcement contacts and its motorist services differ from the state population. The level of analysis in the report is insufficient to ascertain the incidence of racial profiling to any degree of certainty. In order to gain a better understanding of the nature of CHP's public contacts, we recommend that future reports include a more thorough analysis of the data.

Regional Analysis Would Provide More Accurate Assessment. Although CHP's database includes the location of each incident, the report contains only statewide totals and does not break down the results by region. Because there may be significant demographic differences among different regions of the state, we believe that a regional breakdown and analysis would provide a more accurate assessment of the demographic composition of CHP's contacts.

Better Model of Highway User Population Would Be Useful. The report notes that the ethnic composition of the state's highway users may be different from the ethnic composition of the statewide population. This is significant because, in order to determine whether profiling has taken place, the demographic composition of CHP's enforcement contacts should be compared with the demographic characteristics of the highway users in CHP enforcement areas. The report instead compares the enforcement contacts to the overall state population. No analysis was performed to ascertain the extent to which demographic characteristics of the state population differ from highway users.

There are limited means to ascertain the racial background of California's driving population because such information is not collected by the state. The CHP could try, however, a variety of analytical techniques to determine whether the demographic differences between highway users and the overall population of different regions are significant. For example, CHP could conduct a survey to determine Californians' driving patterns. In addition, CHP could perform spot checks at designated test locations along state highways. The checks could consist of "windshield tests" in which observers record the race or ethnicity of drivers who pass through designated points. The demographic composition of the highway users could then be compared with the composition of the overall population for each area. As we note later in this report, such a technique has been used by other law enforcement agencies in these racial profiling studies.

Definitive Conclusion Difficult. Even with the analysis recommended above, it will be difficult for CHP to definitively conclude whether racial profiling is occurring. As noted by GAO and the U.S. DOJ, it is difficult to ascertain the extent of racial profiling in traffic stops without baseline data that establish whether there is actual variation among different racial and ethnic groups' violation of traffic laws. Nevertheless, by undertaking a more vigorous analysis of the data, CHP would gain a better understanding of the role of race in its public contacts. As noted above, CHP is scheduled to collect race data through the end of 2002. If it desires continued data collection, the Legislature, therefore, would need to direct the department to extend the time frame of the project.

The Governor's order that established CHP's demographic data collection program directed the department to report its findings to the Legislature in three annual reports. Two years have passed since the first report was published. The CHP states that it submitted its second report to the Business, Transportation and Housing Agency on August 6, 2001, but it has not been released. We recommend that the Legislature request the release of the second report and the expedited preparation of the third report.

In addition to collecting and analyzing CHP's own data, the Governor directed the department to include in its annual reports information from local agencies that voluntarily submit data on the racial composition of their public contacts. Of the 433 local law enforcement agencies contacted by CHP, only 16 agencies submitted data for inclusion in the 2000 report (see Figure 3).

|

Figure 3 Jurisdictions Included in |

|

|

|

Alameda |

|

Amador County |

|

Anderson |

|

Angels Camp |

|

Corning |

|

Livermore |

|

Newark |

|

Palo Alto |

|

Piedmont |

|

Pleasanton |

|

Redding |

|

San Leandro |

|

San Luis Obispo County |

|

University of California, Berkeley |

|

University of California, San Francisco |

|

Woodland |

For CHP's 2000 report, the 16 participating local agencies submitted data in a variety of formats with various levels of detail. The CHP did not attempt to standardize the information collected to enable comparisons among different agencies. Instead, the report merely included photocopies of the information provided by each agency as an appendix. The CHP did not provide any analysis of the local data reported.

To provide an incentive for local law enforcement agencies to collect racial

composition data on their public contacts, the

Legislature established a grant program in 2000-01.

Funds were provided to local agencies to cover

their costs of data collection. The 2000-01 budget provided a $5 million appropriation for

this purpose. Agencies were eligible for grants between $5,000 and $75,000, depending

on their number of sworn officers, as well as supplemental allocations. To date, about

$4 million has been provided to local agencies.

As shown in Figure 4, the number of local agencies voluntarily participating in the program has grown to 78. Based upon a survey performed by the ACLU in 2001, at least another 14 jurisdictions are collecting race data but have opted to not participate in the state grant program. In total, 16 sheriffs, 75 police departments, and 1 community college district were collecting data as of 2001. These agencies serve more than 40 percent of the state's population. Some local agencies report that they are reluctant to participate in the state's program because of the effort required to collect data and concerns that the information they report could be misinterpreted and used against them.

|

Figure 4 Local Jurisdictions |

|

|||

|

Participation in CHP Grant Program |

|

|||

|

Adelanto |

Mill Valley |

|

||

|

Alameda County |

Modesto |

|

||

|

Alturas |

Morro Bay |

|

||

|

Amador County |

Napa County |

|

||

|

Angels Camp |

Newark |

|

||

|

Arcata |

Novato |

|

||

|

Banning |

Oakdale |

|

||

|

Beaumont |

Oakland |

|

||

|

Bell Gardens |

Palo Alto |

|

||

|

Belmont |

Placer County |

|

||

|

Benicia |

Placerville |

|

||

|

Berkeley |

Redding |

|

||

|

Blue Lake |

Richmond |

|

||

|

Capitola |

Riverside |

|

||

|

Chula Vista |

Rocklin |

|

||

|

Corning |

Roseville |

|

||

|

Dixon |

Sacramento |

|

||

|

Fairfax |

Sacramento County |

|

||

|

Fresno |

San Diego |

|

||

|

Fresno County |

San Luis Obispo County |

|

||

|

Greenfield |

Santa Clara County |

|

||

|

Participation in CHP Grant

Program |

||||

|

Half Moon Bay |

Santa Cruz |

|||

|

Huntington Beach |

Santa Cruz County |

|||

|

Inyo County |

Sausalito |

|||

|

Ione |

Scotts Valley |

|||

|

Isleton |

Sonoma County |

|||

|

Kensington |

Stanislaus County |

|||

|

Livermore |

Stockton |

|||

|

Livingston |

Sutter County |

|||

|

Los Angeles |

Sutter Creek |

|||

|

Los Angeles County |

Tiburon |

|||

|

Mammoth Lakes |

Tulelake |

|||

|

Manteca |

Vacaville |

|||

|

Marin Community College |

Watsonville |

|||

|

Marin County |

West Sacramento |

|||

|

Marysville |

Wheatland |

|||

|

Menlo Park |

Yolo County |

|||

|

Merced County |

|

|||

|

Additional Jurisdictions Reported as |

||||

|

Alameda |

Piedmont |

|||

|

Citrus Heights |

Pleasanton |

|||

|

Colusa County |

San Carlos |

|||

|

Davis |

San Francisco |

|||

|

Emeryville |

San Jose |

|||

|

Fremont |

San Leandro |

|||

|

Hayward |

Union City |

|||

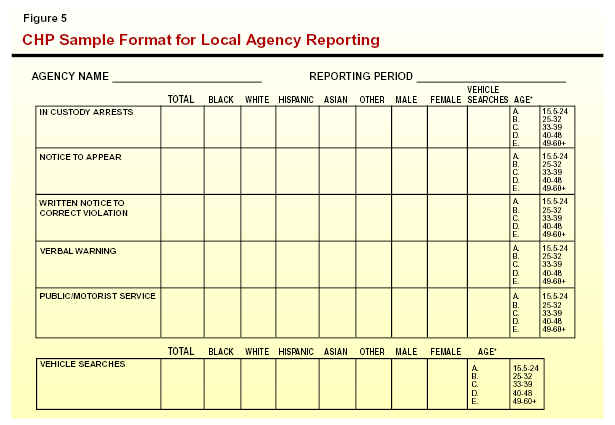

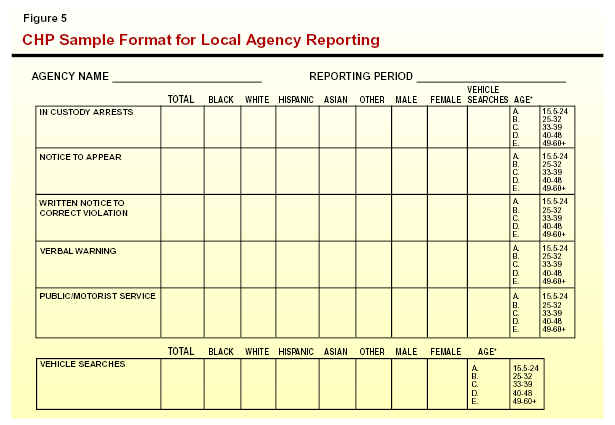

Although the number of participating agencies has increased since the publication of CHP's report, the information they provide continues to lack a standard format. After the 2000 report was issued, CHP developed a sample format (see Figure 5) and definitions for reporting demographic data. While CHP recommends that local agencies use the sample format, the department has not required its use. A majority of the agencies have adopted the form but others continue to use different formats. Some of those agencies using the CHP form have not completed every data category. Agencies have reported their data monthly, quarterly, or annually at their discretion. It is also generally unclear whether departments have followed the suggested CHP definitions of stops and searches. Because data are reported using different formats, different time periods, and different definitions, data from various agencies cannot generally be compared.

To the extent that the Legislature chooses to provide additional funding for a local grant program, we recommend a number of changes in order to improve the usefulness of the data reported.

As indicated above, the local data collected by CHP has a number of limitations. The data lacks standardization in format and definitions used. In addition, the data are aggregated at the department level and do not include any information regarding local police practices. These factors limited our ability to perform any significant analysis of the data. Consequently, we are unable to draw any reliable conclusions from these data. Instead, we reviewed the major reports that have been completed to date by local police departments in California. San Diego, San Jose, Sacramento, and Riverside have all made efforts to analyze the race-related data that they have collected. We begin with a discussion of some common characteristics shared by the reports. We then describe each of the reports in more detail—focusing on their unique characteristics. Figure 6 compares some key components of each report.

|

Figure 6 Comparison of Department

Data Collection and Reporting |

|||||

|

|

CHP |

Riverside |

Sacramento |

San Diego |

San Jose |

|

Data collection |

Paper forms. |

Computer-aided |

Scantron |

Index cards. |

Computer-aided |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dates covered |

July

1999- |

Calendar year 2001. |

Fiscal

year 2000‑01. |

Calendar

year 2000. |

Fiscal

year |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Analysis |

Department staff. |

University |

University |

University |

Department

staff. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Officer identity |

No. |

No. |

Portion

of study |

No. |

No. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reason for stop included? |

No. |

No. |

Yes. |

Yes. |

Yes. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Data on searches included? |

Yes. |

Yes. |

Yes. |

Yes. |

No. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Data comparisons, in addition to population |

Motorist |

Stops by traffic and patrol units. Time of day. Crime |

Crime

victims, suspects, and parolees. Population by neighborhood. |

Traffic |

Population

by police district. |

Acknowledgement of Difficulties With Analysis. Each report acknowledges many of the difficulties described above in collecting and analyzing the racial profiling data. They contain a general tone of caution regarding "reading too much into" the results of the reports.

Use of Population Data for Comparison. While acknowledging the difficulties in establishing an appropriate mechanism to analyze the traffic-stop data, each report attempts to compare police contacts by race to the racial characteristics of the jurisdiction's general population. The more recent reports used 2000 U.S. Census data, while the older reports used various estimates of their jurisdictions' populations. In most cases, the reports found that black and Hispanic drivers were stopped at rates higher than would be expected based on the population comparisons.

In order to prevent any racial disparities in nondriving age populations from skewing the comparison, both San Diego and Sacramento limited the population data to those residents of driving age. Even by limiting the data to driving age population, comparisons to the overall population can be significantly limited in their usefulness without additional refinement. For instance based on local circumstances, jurisdictions may need to attempt to quantify: (1) the extent to which nonresidents drive in the jurisdiction, (2) whether vehicle ownership and driving patterns vary by race, and (3) the extent patrol patterns vary by neighborhood.

In May 2001, the San Diego Police Department released its report for vehicle stops made in 2000. The report found that both black and Hispanic drivers were stopped and searched at rates disproportionately high in comparison to their driving age populations.

Comparison to Accident Data. In seeking another reasonable proxy for drivers on the road, San Diego compared their data to non-hit-and-run traffic accidents (assuming accidents do not vary by race or ethnicity). These accident data varied somewhat from the population and traffic stop rates. Still, the department cautioned against using these traffic data because of the potential for (1) the underreporting of accidents in immigrant communities and (2) neighborhood variations in accidents.

Age Analysis. Because younger drivers were stopped more often and black and Hispanic populations tend to be younger in San Diego than the white population, the report hypothesized that age differences might account for the stop differentials. Yet, upon analyzing racial stops by age, the report found that blacks and Hispanics were still overrepresented in stops in virtually every age category.

After issuing quarterly updates, the San Jose Police Department issued an annual report for 1999-00 vehicle stops in December 2000. As with San Diego, the department found that overall, blacks and Hispanics were stopped at a rate higher than would be expected in comparison to population data, but that was not the case when the comparisons were done on a patrol district level.

Patrol District Analysis. The report attributes the variation in racial stop rates to the organization of the department's police districts. The city's district boundaries are established in a manner to evenly distribute the number of typical calls for service. As a result, some districts are smaller geographic areas than others. Those smaller districts tend to have higher concentrations of minority residents. The report concludes that when district populations are compared to district traffic stops, the proportions are similar.

Stops Due to Vehicle Code

Violations.

San Jose has given its officers four choices for reporting the reason for the vehicle

stop—occupant matches a suspect description,

municipal code violation, state code violation,

and vehicle code violation. Of the nearly 100,000 stops by the department covered in the

report, 99 percent were reported as vehicle

code violations. As a result of these broad

categories, the department does not have the

opportunity to disaggregate stop data in a meaningful

way by reason for stop—perhaps reducing the

ability to explain their data.

Sacramento released its report for 2000-01 stops in October 2001. The report found that blacks were stopped more often than their share of the population would suggest. The report offered a number of possible reasons for this variation, unrelated to racial profiling.

Checks on Data Accuracy. The researchers performed a number of tasks in order to check the validity of the data collected by the departments' officers and the Census comparative data. In order to confirm information regarding the stops, researchers made follow-up phone surveys of drivers who were stopped by the police. Windshield observations of driver demographics at several intersections were taken. While information gathered from these techniques generally tracked the base data, there were enough variations to raise cautions regarding the validity of officer-completed forms and Census data.

Extensive Comparisons. Due to the comprehensive nature of Sacramento's data collection system, the report was able to disaggregate the stop data using a wide range of variables—such as officer experience, type of police unit, type of stop, stops recorded by video and those not, stop length of time, and whether a search occurred. These comparisons open a wide range of possibilities for further data analysis. While the report briefly discusses these variables, they were not fully explored. The city has chosen to continue its data collection and analysis for several more years.

Search Data. In addition to differences by race in those drivers that were stopped, the Sacramento report showed that blacks and Hispanics were subject to searches at a higher rate than whites and those searches averaged longer lengths of time. The report noted that both minority officers and white officers (in both videotaped and nontaped stops) searched minorities at similar frequencies and for similar lengths. This analysis only confirms that police behavior is consistent across the department—but does not help explain the underlying search differentials by race.

Crime Reports and Parolees. The report concludes that the high percentage of blacks among parolees and probationers living in Sacramento are likely explanations for the higher-than-expected stops for blacks. The report, however, does not offer an analytical basis for this conclusion. For example, it does not detail the total number of city parolees or the number of stops attributable to the stopping of parolees.

In March 2002, Riverside released its report on traffic stops conducted during calendar year 2001.

Traffic Versus Patrol Behavior. The study of traffic stops found that Riverside officers stopped blacks at a higher rate than their representation in the overall population of Riverside would indicate. The city's police department is split into two units: (1) traffic units which tend to focus on traffic enforcement and (2) patrol units which involve more discretionary stops. The report divided the data by the type of unit performing the stop. This split showed a considerable variation in stop rates by race—with blacks representing an even higher percentage of the stops for the patrol unit. The report compares the patrol unit stops to crime suspects and victims by race to show these categories also have higher minority representation than the general population.

Time-of-Day Analysis. In preparing the report, the researcher performed a series of windshield counts at several intersections in order to get a broad sense of the driving population. The variation in racial composition of drivers was considerable—with more minority drivers at night and in the early morning. The report illustrates that Riverside's traffic stops are also concentrated at night and in the early morning, which could explain some of the variation in racial composition of stops from the general population.

As with prior reports on racial profiling, the evidence presented in the four cities' reports that we reviewed was not conclusive regarding the incidence of racial profiling in traffic stops. This is because departments have been unable to establish whether drivers of different races violate traffic laws at different rates. Yet, the reports illustrate the potential for thorough examinations of police departments' behavior in regards to contacts with the public. For instance, if adopted, data elements similar to those collected by Sacramento (such as length of stop and officer experience) would offer departments the ability to analyze their data using a wide variety of factors. The other cities` reports reflect the evolving techniques (such as windshield tests) available to departments in seeking to explain the racial composition of their traffic stops. As more cities attempt to explain the data collected, these techniques should continue to become more precise.

Chapter 684 expands the mandatory training of law enforcement officers to include coursework on racial profiling. This law requires POST—which is responsible for developing and certifying a variety of courses for officers—to develop a curriculum on racial profiling in collaboration with a panel of key stakeholders. The course will then be offered by local providers (typically police departments or community colleges). The racial profiling law also requires the LAO to assess the value of this newly required training.

Too Early to Evaluate Racial Profiling Training. Ideally, an evaluation of the racial profiling training course would examine law enforcement attitudes about racial profiling before and after taking the course and, to the extent possible, the degree to which participation in the course influences law enforcement decisions with regard to traffic stops or other public contacts. At the time this report was prepared, the racial profiling curriculum was still in its final stages of development. Therefore, we were unable to assess the value of the training.

Racial Profiling Curriculum Meets Legislative Intent. However, based upon our review of the curriculum content and the process for its development, it appears that POST has met the requirements of Chapter 684. The curriculum covers four major topics—including instruction on the definition of racial profiling, legal considerations, the history of civil rights, and related community considerations. Earlier in this report, we recommended that the Legislature develop an improved definition of racial profiling. If the definition were revised, POST would likely need to update that portion of its curriculum to reflect the change in state law.

The training uses accepted instructional methods, such as group discussions, role-playing, video, and presentations. In developing the five-hour racial profiling course, POST consulted with community stakeholders and law enforcement. The initial training of instructors has begun, and the course will be taught as the instructors complete their training.

POST Plans to Evaluate Racial Profiling Course. The POST plans to evaluate the racial profiling course as it does other courses. Course participants will fill out forms evaluating the course on its content, presentation, instructor, and job applicability.

There are limited useful data on racial profiling in California and analysis of the data is in the early stages of development. We, therefore, recommend that POST work with law enforcement agencies that collect data in an ongoing effort to integrate into the racial profiling course issues that emerge as part of the data collection effort. The POST should also ensure that its other courses and guidelines are up-to-date with relevant information regarding racial profiling.

Likewise, CHP should use its data to improve its training programs. The CHP currently uses the data it compiles on the demographic composition of its public contacts solely for preparation of the reports it is required to submit to the Governor and Legislature. The department indicated that the information is not used to gauge the effectiveness or to improve the usefulness of its training program. We recommend that CHP use any data it collects in the future to provide feedback on the effectiveness of CHP's new POST-certified training. The collected data could be used to help evaluate, modify, and improve training procedures on an ongoing basis.

Nearly 100 law enforcement agencies in California now collect data related to racial profiling. Yet, the manner in which the data are gathered and analyzed remains fragmented. We recommend a number of improvements, summarized in Figure 7 (see page 20), for racial profiling data collection, analysis, and training in the state. These changes—combined with the continued improvement in data analysis techniques by law enforcement researchers—would improve the effectiveness of these efforts in the future.

|

Figure 7 Summary of LAO

Recommendations |

|

|

|

Definition |

|

·

Revisit state definition of racial profiling and develop

one which more explicitly defines what activities are |

|

CHP Reports |

|

·

Direct CHP to conduct additional data analysis, including

conducting regional analysis and developing a |

|

·

Request the release of second annual report and the

expedited preparation of the third report. |

|

Local Grant Program |

|

·

Require all participating agencies use the same standard

format and definitions. |

|

·

For any future program, select state department better

equipped to collect and analyze the data in a |

|

POST Training |

|

·

Direct POST and CHP to use data collected in order to

improve the effectiveness of training courses. |

| Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by , Michael Cohen, Sam Delson, Stephanie Marquez, Dana Curry and Greg Jolivette. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814. |