On August 3, 2004, the California Performance Review (CPR) released its report on reforming California's state government, with the aim of making it more efficient and more responsive to its citizens. This report provides our initial comments on the CPR report. Specifically, we: (1) provide an overview of its reorganization framework and other individual recommendations, (2) discuss the savings it assumes from its major proposals, and (3) raise key issues and considerations relating to CPR's various proposals.

On August 3, 2004, the California Performance Review (CPR) released its report to the Governor on reforming California government. The report lays out a framework for reorganizing and consolidating state entities, and contains 278 issue areas and 1,200 individual recommendations aimed at making state government more modern, efficient, accountable, and responsive to its citizens. The CPR also adopted the 239 proposals included in a report recently issued by the Corrections Independent Review Panel. The CPR asserts that the state would achieve about $32 billion in savings over the next five years if all of its recommendations were fully adopted.

The CPR has four volumes. The first sets forth its major goals, the second lays out a reorganization plan for state government, the third provides a budget and financial review of California state government, and the fourth contains CPR's individual proposals.

LAO's Bottom Line. The CPR provides the state with a valuable opportunity to comprehensively examine how it does business. It has made a serious effort at rethinking the current organization of state government and how it delivers services to the people of California. We find that many of its individual recommendations would move California toward a more efficient, effective, and accountable government.

At the same time, the rationale for some of its reorganization proposals is not clear, it does not examine whether the state should continue to perform certain functions, and many of its fiscal savings estimates are overstated.

For these reasons, it will be important for the Legislature to evaluate the merits of the proposals individually, looking at their policy trade-offs, their likely effectiveness, and their fiscal implications. The Legislature also may wish to consider broadening the scope of reforms offered by CPR to include a more comprehensive examination of the state and local tax system, the role of constitutional officers, the state's system of funding education, and the relationship between state and local government.

Organization of This Report. This report, which provides our initial reaction to the CPR report, has three sections:

The CPR has two major components—a reorganization of state entities and other individual recommendations. Below we briefly describe both of these components.

The CPR proposes a major reshuffling of the state's agencies, departments, boards, commissions, and other entities. In reorganizing state government, the CPR proposal focuses on aligning similar programs and consolidating administrative functions in order to eliminate duplication of effort and improve customer service. The major components of the reorganization are:

As noted above, the CPR identifies 278 issue areas and contains about 1,200 specific proposals affecting a wide range of government programs. Although the proposals cover a vast number of individual areas, they can be generally placed into one or more of the following five broad categories.

The CPR indicates that its proposals, if fully adopted, would generate savings of slightly over $1 billion in 2004-05 and $32 billion over the next five years combined. According to CPR estimates, about one-third of the cumulative savings would accrue to the General Fund and the remaining two-thirds would accrue to special funds, federal funds, and local funds. Figure 1 (see next page) shows that on an annual basis, savings to the General Fund are projected to be in the range of $2 billion to $3 billion per year starting in 2005-06, while annual savings to other funds are projected to average $5 billion to $6 billion.

As shown in Figure 2 (see page 7), proposals in 15 issue areas account for almost 88 percent of the total savings estimated by CPR for the next five years. Nearly one-half the total is related to just three broad proposals: one to maximize federal grants ($8.2 billion), another to transform eligibility processing for Medi-Cal, CalWORKs, and food stamps ($4 billion), and the third related to the creation of a workforce plan for California state employees that would result in fewer employees ($3.3 billion). Significant savings are also scored for transportation funding proposals which include seeking higher federal taxes on fuels containing ethanol, changes in enrollment cutoff dates for kindergarten, biennial vehicle registration (mostly one-time revenues from the acceleration of fees paid by motorists), increased lottery sales, and increases in college and university tuition for out-of-state residents.

|

Figure 2 Fifteen CPR Proposals With

Largest Fiscal Effects |

||||||

|

(CPR Estimates, Dollars in Millions) |

||||||

|

Rank |

CPR |

Issue |

Five-Year

Savings |

Cumulative

Percent of Total |

||

|

General

Fund |

Other

Funds |

Total |

||||

|

1 |

GG

07 |

Maximize

Federal Grant Funds |

� |

$8,200 |

$8,200 |

26% |

|

2 |

HHS

01 |

Transform

Eligibility Processing |

$1,548 |

2,471 |

4,018 |

39 |

|

3 |

SO

43 |

Work

Force Plan for |

1,646 |

1,646 |

3,293 |

49 |

|

4 |

ETV 11 |

Change Enrollment Entry Date for Kindergartners

|

1,880 |

820 |

2,700 |

58 |

|

5 |

INF

15 |

Transportation

Funding Initiatives |

� |

1,960 |

1,960 |

64 |

|

6 |

GG

36 |

Biennial

Vehicle Registration |

1,259 |

� |

1,259 |

68 |

|

7 |

GG

06 |

Lottery

Reforms |

� |

1,024 |

1,024 |

71 |

|

8 |

ETV

18 |

|

� |

1,004 |

1,004 |

74 |

|

9 |

SO

71 |

Performance-Based

Contracting |

485 |

485 |

970 |

77 |

|

10 |

SO

72 |

Strategic

Sourcing |

427 |

427 |

855 |

80 |

|

11 |

INF

30 |

Decentralize

Real Estate Services |

410 |

410 |

819 |

83 |

|

12 |

INF

13 |

Relinquish

Highway Routes to Local Agencies |

� |

432 |

432 |

84 |

|

13 |

GG

01 |

Tax

Amnesty |

384 |

15 |

399 |

85 |

|

14 |

INF

11 |

Selling

Surplus Property Assets |

379 |

� |

379 |

86 |

|

15 |

GG

17 |

Tax

Relief on Manufacturing Equipment |

343 |

� |

343 |

88 |

|

|

|

All

Other CPR Proposals |

2,029 |

1,921 |

3,950 |

100 |

|

|

|

Totals,

All CPR Proposals |

$10,791 |

$20,815 |

$31,606 |

100% |

Savings Overstated. In many instances, the CPR was conservative in scoring savings from its individual proposals—acknowledging that actual savings, while likely, simply could not be estimated. However, in other instances, the CPR scored savings that are uncertain or overstated. This is especially the case with regard to many of the proposals with the largest identified savings shown in Figure 2. Specifically, we found that:

Taking into account these factors, we believe that a more realistic savings assumption attributable to state actions would be less than one-half of the $32 billion shown. While any estimate of savings is highly uncertain, we believe that a more reasonable cumulative estimate for all funds over the next five years would be roughly $10 billion to $15 billion. In annual terms, this translates into $3 billion or less per year, divided roughly evenly between the General Fund and other funds. Regarding the revised General Fund total, nearly one-half of the savings would be attributable to a single proposed change—the delay in the enrollment entry date for kindergartners who are less than five years old at the beginning of the school year.

Our lower overall savings estimate does not make the goals or proposals offered by the CPR any less valid. The state would clearly benefit from changes that enhance workforce productivity, improve and streamline services, and reduce inefficiencies in government—even if the savings were only a fraction of the CPR estimates. At the same time, it is important to recognize that even if all the CPR's recommendations were adopted, the fiscal savings would only cover a relatively small portion of the large structural shortfall facing California's budget in the future. Stated another way, even if the proposals were adopted, the state will continue to face hard choices regarding program funding levels and taxes in order to balance its future budgets.

The CPR has developed an impressive list of proposals in a relatively short timeframe, which provides the state with a valuable opportunity to examine many aspects of how it does business. At the same time, the report raises a large number of important policy issues which need to be considered.

California's past successes and failures with reorganization plans strongly suggest that reorganizations should be undertaken only when (1) there is a clearly defined problem with the existing system and (2) there is a convincing reason to believe that the new system will address the problem and, more generally, enable the state to provide services more efficiently and effectively. We believe there are a number of areas that the CPR has identified where these fundamental criteria may apply. For instance, in the health area, the proposed centralization of a number of public health programs could improve their effectiveness.

Yet, in many other areas, the reorganization plan lacks a strong rationale. As we discuss in more detail in "Section 2," among the problems we identify are:

Given these concerns, we recommend that the Legislature not focus its attention on the large-scale statewide reorganization that the CPR envisions. Instead, the Legislature should seek out more specific opportunities to pursue consolidations on a smaller scale. Many of the current problems that CPR identified could be solved with simpler solutions. A combination of limited consolidations and other types of solutions (such as improved leadership, policy changes, better coordination between departments, interagency agreements, and cross-departmental training) offers a better chance of improving the effectiveness of state government while limiting the risks involved.

The CPR's proposals encompass a broad range of issues. However, there are a number of fundamental issues that were not considered in the analysis. For example, while the CPR reorganization plan regroups and consolidates a vast number of existing functions of state government, the CPR does not examine the more fundamental question of which functions should continue to be provided by the state. In addition, although the CPR presents a modest realignment proposal, the report does not comprehensively address the state-local system of service delivery. Similarly, while including a single tax incentive proposal, the CPR does not examine California's overall system of state and local taxes.

Finally, while the plan proposes specific changes to the Constitution as it relates to transportation and a biennial budget, it does not address many other constitutional issues, such the role of constitutional officers and agencies in the restructured government. The latter is a significant consideration in the context of the CPR's proposed reorganizations. As noted in "Section 2" and "Section 3" of this report, the future roles of the Superintendent of Public Instruction and the BOE—two constitutionally created entities—are left somewhat undefined in the context of the restructured government proposed by the CPR.

Addressing these more fundamental issues may have been beyond the scope of what the CPR believed was its mission, especially given the relatively limited time it had to complete its review. However, the lack of reforms in these areas inherently limits the amount of improvement in governmental services that can be achieved through the CPR.

For example, while some of the CPR proposals may improve efficiency and coordination of state functions, citizens may continue to be faced with the fragmentation of services between state and local governments. Similarly, while the creation of a new tax commission may result in some added efficiencies in the collection and auditing of certain taxes, the exclusion of the BOE from the consolidation means that the state's two largest taxes—the personal income tax and sales tax—will continue to be administered by separate agencies. To address these issues, the Legislature may wish to broaden the scope of reforms it considers.

The release of the CPR is intended to be a first step in a dialog on governmental reform. Its specific proposals have not yet been embraced by the administration. Rather, the Governor has directed the CPR commission to hold public hearings to seek input on the report's recommendations.

Ultimately, the reorganization plan could be proposed by the Governor through the specific reorganization process provided for in state law (and discussed in "Section 2"). Some of the other recommendations—such as those requiring departments to develop performance measures—could be implemented administratively by the Governor. Other recommendations could be included in the Governor's 2005-06 or later budgets, or proposed through separate legislation.

Thus, while some of the 1,200 CPR proposals can be adopted administratively, many of them will require legislative approval in order to be implemented. The merits of each proposal would need to be weighed on its own. In "Section 3" we review some of the CPR's key proposals in major program areas and offer our initial comments on them. Some of the recurring issues raised by our analyses are:

For these reasons, it will be important for the Legislature to weigh the merits of each proposal—taking into account its fiscal effects, its policy implications, and whether it represents the most effective way of achieving the fundamental goals of state government.

One of the major components of the CPR report is a reorganization of the state's departments, agencies, boards, and other entities. Below, we describe this reorganization plan and then provide some of our initial observations.

The CPR report puts forth two principles that are at the center of its approach to reorganizing state entities:

In addition to these principles, the report also emphasizes improving customer service and ensuring that the best and most effective practices of individual departments are used throughout state government.

Mega-Departments. Currently, the state is organized with both agencies and departments. Agencies generally perform policy-setting and oversight roles in a particular policy area. Under an agency's supervision, departments implement programs. For instance, the Department of Financial Institutions (DFI) regulates banks and credit unions under the guidance of the Business, Transportation, and Housing Agency. The core of the CPR reorganization is the creation of 11 large, mega-departments. The proposed 11 departments are listed in Figure 3 (see next page). These mega-departments—called "departments" by CPR—would merge the policy-setting function of agencies with the program administration function of departments.

|

Figure 3 CPR�s 11

Mega-Departments |

|

|

Proposed Department |

Major

Departments Transferred |

|

Commerce and Consumer Protection |

Financial Institutions, Consumer Affairs, Motor

Vehicles |

|

Correctional Services |

Corrections, Youth Authority, Board of Prison

Terms, Office of Inspector General |

|

Education and Workforce Preparation |

Community Colleges Chancellor, Board of Education,

Student Aid Commission |

|

Environmental Protection |

Water Quality Control Boards, Air Resources Board,

Pesticide Regulation |

|

Food and Agriculture |

Food and Agriculture |

|

Health and Human Services |

Health Services, Social Services, Mental Health,

Developmental Services, Child Support |

|

Infrastructure |

Transportation, State Water Project, Energy

Commission, Bay-Delta Authority |

|

Labor and Economic Development |

Industrial Relations, Employment Development |

|

Natural Resources |

Conservancies, Fish and Game, Forestry (Resource

Management), Parks and Recreation |

|

Public Safety and Homeland Security |

Emergency Services, Highway Patrol, Forestry (Fire

Protection) |

|

Veterans Affairs |

Veterans Affairs |

In most cases, these new departments would represent the merger of several existing departments. For instance, both DFI and the Department of Corporations would merge as a new Financial Services Division within the proposed Commerce and Consumer Protection Department. Other divisions within the same department would include most functions from existing departments such as the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) and the Department of Real Estate. In other cases, existing departments are divided—with their component functions distributed among several new departments. For example, functions from the Department of Fish and Game would be distributed to the Environmental Protection, Natural Resources, and Public Safety and Homeland Security Departments.

Discontinuation of Many Boards and Commissions. The state has hundreds of boards, commissions, and task forces which serve a variety of roles—including administering grant programs, regulating industries, and providing policy advice. These entities generally are governed by a board appointed by the Governor, Legislature, or other state officials. Some board members receive full-time salaries while many others only receive reimbursements for their travel and other expenses. The CPR identified 339 existing boards, commissions, and task forces across state government. The report recommends discontinuing 117 of these entities, including the Air Resources Board, State Lands Commission, Energy Commission, State and Regional Water Quality Boards, Student Aid Commission, Victims Compensation and Government Claims Board, Board of Prison Terms, and Youth Authority Board. For the majority of these discontinuations, the CPR consolidation would move these entities' activities under one of the new mega-departments. In other words, the government activity would continue but be governed by a departmental secretary, rather than an independent board. On the other hand, the CPR would eliminate both the function and the entity in about four dozen cases. Most of these entities entirely eliminated provide policy advice to the state (such as the Rural Health Policy Council and the 911 Advisory Board) rather than administer programs. The report notes that the elimination of these advisory boards could be replaced with ad-hoc advisors on an as-needed basis.

Other New Entities. In addition to the creation of the mega-departments, the CPR proposes to create several other new entities in state government, including:

Some Entities Largely Unaffected. In some areas, the CPR proposes few, if any, changes to existing department structures. For instance, constitutional officers are left largely unaffected. In addition, the Military Department would remain an independent entity outside of the mega-department structure. The Departments of Food and Agriculture and Veterans Affairs would be elevated to mega-departments, but their roles and responsibilities would remain largely unchanged.

The report acknowledges that fully implementing its governmental reorganization is an "ambitious" undertaking. The report provides few details on a timeframe for implementation but suggests the use of a centralized performance review team to coordinate any consolidations.

The Reorganization Process. State law provides a specific process for the Governor to propose reorganizations to the Legislature. Since 1968, various Governors have submitted 29 reorganization plans through this process. The Legislature approved 18 of these plans. Figure 4 (see next page) lists these plans, and the box (see end of section) provides a historical perspective on reorganizing state government as it relates to the health and social services area.

|

Figure 4 Previous Executive Branch

Reorganization Proposals |

|||

|

Year |

Governor |

Description |

Outcome |

|

1968 |

Reagan |

Establish four agencies:

Business and Transportation, Resources, Human Relations, and Agriculture

and Services. |

Approved |

|

1969 |

Reagan |

Eliminate various boards and

commissions and transfer some functions to other departments.

Change the names of the

Department of Harbors and Waterways and the Harbors and Watercraft

Commission.

Change staff titles and

organization names in the Department of Professional and Vocational

Standards (DPVS). |

Approved Approved Approved |

|

1970 |

Reagan |

Create the Department of

Health and consolidate three departments.

Change DVPS to the Department

of Consumer Affairs. |

Approved Approved |

|

1971 |

Reagan |

Change the names of some of

the water quality control boards.

Eliminate the State Board of

Drycleaners.

Change the name of the

Resources Agency to Environment and Resources Agency and create the

Department of Environmental Protection. |

Failed Failed Failed |

|

1975 |

Brown |

Consolidate air, water

quality, and solid waste programs into the Environmental Quality Agency.

Consolidate the Divisions of

Labor Law Enforcement and Industrial Welfare into the Department of

Industrial Relations (DIR). |

Failed Approved |

|

1976 |

Brown |

Consolidate air, water

quality, and solid waste programs into the Environmental Quality Agency.

Consolidate the Office of

Alcoholism with the Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control (ABC) and

transfer ABC to the Health and Welfare Agency. |

Failed Failed |

|

1977 |

Brown |

Transfer functions from the

Office of Narcotics and Drug Abuse to a new Department of Health

Services (DHS) and create an Advisory Council on Narcotics and Drug

Abuse. |

Approved |

|

1978 |

Brown |

Transfer industrial safety and

occupational health functions from DHS to DIR. |

Approved |

|

1979 |

Brown |

Transfer employment functions

from DIR to State and Consumer Services Agency and create the Department

of Fair Employment and Housing.

Create new central agency for

personnel administration.

Create the Youth and Adult

Correctional Agency. |

Approved Withdrawn Approved |

|

1980 |

Brown |

Transfer mobilehome functions

to the Department of Housing and Community Development. |

Approved |

|

1981 |

Brown |

Create the Department of

Personnel Administration (DPA). |

Approved |

|

1984 |

Deukmejian |

Transfer position

classification functions from State Personnel Board to DPA. |

Approved |

|

1985 |

Deukmejian |

Create the Department of Waste

Management, State Waste Commission, and three regional waste boards.

Create a cabinet-level

Department of Waste Management. |

Failed Failed |

|

1991 |

|

Create the Environmental

Protection Agency and transfer several departments and functions into

the new agency. |

Approved |

|

1995 |

|

Reorganize the

Consolidate the State Police

with the

Consolidate the State Fire

Marshal with the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. |

Failed Approved Approved |

|

1998 |

|

Eliminate the Department of

Corporations, create the Department of Managed Care, and rename the

Department of Financial Institutions. |

Failed |

|

2002 |

|

Create the California Labor and Workforce Development Agency and

transfer several departments into the new agency. |

Approved |

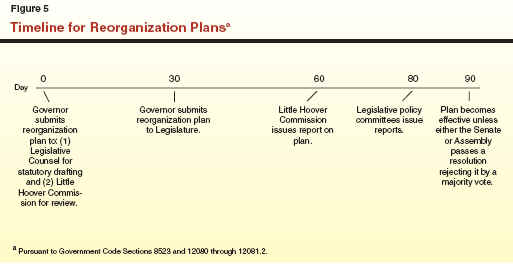

Figure 5 (see page 15) provides a sample timeline for the reorganization process. In total, a reorganization plan can take 90 days to become effective. Among the key components of the process are:

In reviewing the CPR reorganization plan, there are many considerations for the Legislature. Figure 6 (see next page) lists some of the criteria that we would suggest the Legislature use in evaluating any proposed reorganization. Below, we outline some additional considerations specific to the CPR and offer our initial comments on the proposed reorganization. Later in this report, we provide more program-specific comments on some of the more significant components of the reorganization.

|

Figure 6 Criteria for Considering

the |

|

|

|

As the Legislature considers the CPR and other future reorganization proposals, it may want to consider the following questions to help determine a proposal�s merits. |

|

� Effectiveness. Would the reorganization make the programs more effective? Would the public receive better services as a result of the reorganization? |

|

� Accountability. In the current and the new structures, who is responsible for the program�s outcomes? Is the new structure likely to improve program accountability? |

|

� Oversight. Will the new structure provide for effective, independent oversight by the executive and legislative branches? |

|

� Efficiency. Would the reorganization improve the use of limited resources? Are there reasons to believe that the programs can be administered more efficiently? Do existing programs exhibit duplication of effort or lack of coordination? |

|

� Other Options. What is the problem that is being addressed? Is a reorganization the best approach to solve that problem? Could improved leadership, changes in policy, better coordination between departments, or other solutions provide a better result? |

|

� Implementation. Do the expected long-term benefits outweigh the short-term costs and disruptions from the implementation of the reorganization? Will the public experience a disruption in services? Does the implementation need to occur now, or can it be phased in over time? |

Opportunities for Greater Efficiencies Exist, But More Details Needed. Consistent with the CPR, we believe that many aspects of state government's organization can be improved. Our initial review of the CPR's consolidation proposal finds that the report has correctly identified some good candidates for consolidation. For instance, in the health area, the proposed centralization of a number of public health programs could improve their effectiveness. Likewise, the merger of the Departments of Mental Health and Alcohol and Drug Programs could allow the state to better coordinate services to those dually diagnosed patients who are currently served by both departments. At this stage, however, the reorganization proposal often lacks sufficient detail to evaluate whether a proposed consolidation would improve state government. Until the full details of a proposed reorganization are put forth, drawing conclusions about many of CPR's suggestions is difficult.

Reshuffle or Change the Scope of Government? For the most part, the CPR reorganization is a reshuffling of existing state activities. Examining the organization of government services is a necessary and important task. It is not always clear, however, that CPR asked a more fundamental question—should the state continue to perform its current functions and provide its current services? As such, the reorganization plan may have missed the opportunity to rethink what level of government should be responsible for each service or if certain government services are still necessary.

Is Changing the Organizational Structure the Solution? As noted above, some of the proposed consolidations offer promise to improve the quality of government services. In other cases, there may be more simple solutions to a massive reorganization. For instance, to increase coordination between two departments, interagency agreements could be developed in place of a full merger. In addition, the administration could use cross-departmental training to spread those management and other practices it has identified as particularly effective.

Possible Unintended Consequences. We recognize that any proposed overhaul of state government on the scale of CPR would invite many questions regarding why certain entities are proposed to be placed in one department versus another. In many instances, reasonable minds can differ over in which location a program would be most effective. That said, our initial review raised some concerns with a number of CPR's choices. The full implementation of the CPR reorganization could lead to some unintended negative consequences. The examples noted below are illustrative that the Legislature will need to carefully examine each consolidation component in detail.

Missed Opportunities. While the CPR reorganization affects most state entities, the Legislature should not consider the plan an exhaustive list of possibilities. In some areas, there appears to be additional room for consolidations to improve state government. For instance, by keeping the Department of Veterans Affairs outside of most of the reorganization plan, CPR may not have considered the option of merging the veterans' homes with the state's other 24-hour care facilities. Similarly, CPR aimed to consolidate all education programs within the Education and Workforce Preparation Department. Yet, the CPR maintains the existing roles and responsibilities of the Superintendent of Public Instruction (SPI). Maintaining the overlapping responsibilities of the SPI and other education administrators represents a missed opportunity to repair a central governance issue in K-12 education.

Considering the Merits of Independent Boards. The CPR reorganization emphasizes a transition away from independent boards and commissions and towards executive program management. In evaluating these types of decisions, the Legislature should consider both the benefits and drawbacks regarding the use of independent boards. Among the benefits of independent boards are:

On the other hand, independent boards also may have some disadvantages, including:

Unknown Implementation Costs. The proposed reorganization, if implemented, would result in significant implementation costs, particularly in the short term. In many cases, the fiscal estimates of the CPR do not take into account these expenses, such as the costs for integrating data and budget systems and relocating offices. As an example, the recent closing of the Technology, Trade, and Commerce Agency cost millions of dollars in shutdown expenses—nullifying most of the savings for the first year. While these types of implementation costs typically do not provide sufficient justification on their own to dismiss a proposed reorganization, the Legislature should be aware of them in making its decisions. This is particularly true in the cases when the recommendations are being implemented primarily to generate budget savings.

REORGANIZATIONS: A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVEReorganizations: Then and NowReorganizing state government by consolidating departments, or breaking them apart, is not new. One of the major differences between prior reorganizations and the CPR proposal is its sheer scope. Previous reorganization proposals have focused on a limited number of related departments and programs. These have included, for example, combining labor and employment departments under one agency in 2002; placing various environmental departments under one agency in 1991; and merging health and certain social services programs into a single department in 1970. The CPR proposal, by contrast, envisions a reorganization of the entire state government, involving virtually every state department and generally consolidating them into larger state entities. Health and Social Services ExperienceConsolidation of Departments in 1973. The CPR's proposal to reorganize health and social services departments into one mega-department is similar—but larger in scope—to one adopted by the Legislature and then subsequently disbanded in the late 1970s. In 1970, Governor Reagan proposed the creation of a unified Department of Health in order to improve the integration of health and related programs, reduce program fragmentation, and further program coordination. In submitting his reorganization plan to the Legislature, Governor Reagan noted: "The Plan that I am submitting to you will enable us to eliminate much of the fragmentation that exists in such fields as mental retardation, alcoholism, and facilities licensing. . . . It will encourage integration of health and related services, replacing the present system under which the consumer must find his way through a maze of uncoordinated services." In response to Governor Reagan's proposal, the Department of Health was created effective July 1, 1973 by combining the former Departments of Mental Hygiene, Public Health, and Health Care Services together with the social service functions of the Department of Social Welfare. Among other programs, the new department was responsible for: Medi-Cal, public health, mental health, drug and alcohol, developmental disabilities, licensing and certification of health facilities, and various social services for welfare recipients. (The department was not responsible for providing welfare cash grants, which was assigned to a new Department of Benefit Payments.) Separation of Departments in 1978. For a variety of reasons, the unified Department of Health was unable to fulfill its promise, leading to the enactment of Chapter 1252, Statutes of 1977 (SB 363, Gregorio), which created five new departments and one new office. In enacting Chapter 1252, the Legislature declared that it was separating the Department of Health into distinct departments in order "to increase individual program visibility, to improve program policy direction and to provide needed public accountability." The new departments were Health Services, Social Services, Mental Health, Developmental Disabilities, and Alcohol and Drug Abuse. The new office was the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. Implications for CPR Proposal. The fact that a large consolidated department did not work the last time around does not mean that the current CPR proposal to establish a consolidated Health and Human Services Department should be rejected automatically. Rather, it provides a cautionary warning that reminds the Legislature and administration that they will need to (1) determine whether there are any lessons to be learned from the state's previous experience, and (2) assess how the new proposed reorganization meets their criteria for improving the delivery of state services. |

| LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814. |