This report provides our projections of General Fund revenues and

expenditures for 2004-05 through 2009-10. It includes our independent assessment of the outlook for California's economy, demographics, revenues,

and expenditures.

Chapter 1 contains our principal findings and conclusions. Chapter 2 presents our economic and demographic projections, Chapter 3 our revenue

forecasts, and Chapter 4 our expenditure projections.

Our fiscal projections reflect current-law spending requirements and tax

provisions. They are not predictions of future policy decisions by the Legislature, nor

are they our recommendations as to what spending and revenue levels should be.

This report, in its tenth year of publication, reflects the historical mission

of the Legislative Analyst's Office to assist the Legislature with its fiscal planning

by assessing the revenues and expenditures of the state. The report is part of

an ongoing series and is updated periodically.

Chapter 1

The Budget Outlook 1

Chapter 2

Economic and Demographic Projections

9

Chapter 3

Revenue Projections 19

Chapter 4

Expenditure Projections

27

In approaching the 2005-06 budget,

California's policymakers face a deceptively difficult

challenge. On the one hand, the strengthening revenue

picture, coupled with the availability of the

remaining $3.5 billion in authorized deficit-financing

bonds that have not yet been used, would enable the

Legislature to balance the 2005-06 budget by making

a relatively modest amount of hard choices to

reduce spending and/or augment revenues.

This would only be a temporary fix, however, as the 2005-06 outlook masks a much more

negative underlying budget picture. This is because the 2005-06 budget will be helped by a carry-over balance and various limited-term solutions enacted

in the 2004-05 budget which will not be available

in subsequent years. As a result, these solutions

cannot be counted on to address the state's large

and persistent ongoing structural budget shortfall.

We project that this shortfall will reach nearly

$10 billion in 2006-07 under current-law spending

and revenue policies, absent corrective actions.

The size and persistence of this shortfall, even

in the face of an expanding economy and strengthening revenues, underscores a critical point that

we have made in the past—namely, it is unlikely

that California will be able to simply "grow its way

out" of this shortfall.

Given the above, we believe it is critical that the Legislature act now to address the large underlying structural budget imbalance. Every ongoing budget solution that is adopted this year will reduce the amount of actions that will be needed later. Conversely, postponing action will only make the state's fiscal matters worse in the future. Therefore, we recommend that the state adopt real and ongoing solutions to close the budget gap in 2005-06 and that it not sell the remaining $3.5 billion in deficit-financing bonds at this time. Such an approach will have the dual benefits of both (1) reducing the structural deficit in later years through adopting ongoing solutions, and (2) preserving the bonding authority for possible use in 2006-07 or thereafter, when the current-law structural shortfall gets much larger and harder to deal with.

The 2004-05 budget adopted last summer addressed a roughly $15 billion budget shortfall. As shown in Figure 1, that budget plan contained a variety of budget-balancing actions, including substantial borrowing, a two-year diversion of property taxes, targeted revenue increases, funding shifts (including higher education student fee increases), and significant program savings in education and other areas of the budget.

Proposition 98 Suspension. The budget

package included a suspension of Proposition 98 and

language in Chapter 213, Statutes of 2004, that

2004-05 education spending be set at $2 billion less than

the minimum guarantee. (This language, in effect,

signals the Legislature's intent to provide

more/less funding if the guarantee increases/decreases

during the year—for example, due to changes in

revenues or attendance.) The difference between this

Chapter 213 "target" level and the actual amount

appropriated by the budget—$302 million—is shown

as a Proposition 98 reserve in the 2004-05 budget.

General Fund Condition. Under the budget

plan, the 2004-05 fiscal year was estimated to

conclude with a reserve balance of $768 million, of

which $302 million was earmarked for Proposition 98

and the remaining $466 million was to be available

for non-Proposition 98 purposes. Because of

the budget's reliance on one-time or limited-term

solutions, it was clear when the budget was adopted that the

state would continue to face substantial budget shortfalls in the

future, absent further corrective actions.

Since the 2004-05 budget was enacted, there have been various developments affecting the revenue and expenditure sides of the budget. Key changes in our fiscal estimates relative to the budget act are shown in Figure 2.

|

Figure 2 Effect of Recent

Developments on 2004-05 Budget |

||

|

(In Millions) |

||

|

|

|

|

|

2004-05 Budget Year-End Reserve |

|

|

|

Proposition 98 reserve |

$302 |

|

|

Non-Proposition 98 reserve |

466 |

|

|

Total |

|

$768 |

|

Higher Revenues (2003-04 Plus 2004-05) |

|

|

|

2003-04

major taxes |

$430 |

|

|

2004-05

major taxes |

1,997 |

|

|

2004-05

nontax revenues |

-364 |

|

|

Subtotal

(increase to reserve) |

|

$2,063 |

|

Higher Costs/Reduced Savings |

|

|

|

Punitive damage award redirection |

$390 |

|

|

Unallocated savings |

316 |

|

|

Corrections |

201 |

|

|

Medi-Cal |

96 |

|

|

Trial courts |

90 |

|

|

Proposition 98: lower |

-445 |

|

|

Other |

212 |

|

|

Subtotal

(decrease to reserve) |

|

$860 |

|

Revised

Reserve: |

|

$1,971 |

|

Proposition 98 Reserve |

|

(1,357) |

|

Non-Proposition 98 Reserve |

|

(614) |

Revenues Up Sharply. We estimate that the major

taxes will exceed the budget estimate by $2.4 billion over

2003-04 and 2004-05 combined, due to a sharp increase

in the corporation tax and more moderate gains in both the personal income tax and the sales and

use tax. Partly offsetting the increase in tax revenues is

a $364 million decline in nontax revenues, due

to lower-than-expected receipts from tribal gaming revenues and the sale of surplus property. The

net increase in General Fund revenues is $2.1 billion.

Costs Are Also Up. Offsetting a significant

portion of the revenue increase are higher state

costs totaling about $860 million. The increases are

occurring in a variety of areas, including

corrections, Medi-Cal, trial court funding, and spending on

state operations. In some instances, the higher costs

are occurring because the amount of savings

resulting from various budgetary solutions is falling short

of earlier estimates.

Revised Reserve. Taking into account the

higher revenues and higher costs, we estimate that the

year-end reserve increases by about $1.2 billion, to

just under $2 billion.

Proposition 98 Interaction. The increase in

projected 2004-05 tax revenues increases the

minimum Proposition 98 K-14 funding guarantee by

about $1 billion compared to the budget plan.

Consequently, if the Legislature funds Proposition 98

at the Chapter 213 target level (that is, $2 billion

below the guarantee), it would require a $1 billion

increase in school appropriations. In Figure 2, we

have reflected this higher obligation as an increase in

the Proposition 98 reserve from $302 million

to $1.357 billion. This leaves $614 million of the

total reserve available for non-Proposition 98

purposes, only a marginal increase from the $466 million

estimated at the time the budget was enacted. Thus,

the large increase we project in tax revenues is

almost completely offset by increased spending due to

the Proposition 98 interaction and higher costs in

other program areas.

Figure 3 shows the General Fund condition through 2005-06, using the assumptions outlined in the accompanying box. We estimate that revenues will climb to $82.2 billion and expenditures will total $89.5 billion in 2005-06, resulting in a $7.3 billion operating shortfall (that is, the difference between annual revenues and annual expenditures). After taking into account the $614 million non-Proposition 98 reserve available from 2004-05, the 2005-06 year-end deficit would be $6.7 billion.

|

Figure 3 LAO Projection of General

Fund Condition |

|||

|

2003-04 Through 2005-06 |

|||

|

|

2003-04 |

2004-05 |

2005-06 |

|

Prior-year balance |

$4,178 |

$3,542 |

$1,543a |

|

Revenues and transfers |

75,000 |

78,884 |

82,247 |

|

Deficit-financing bond |

2,012 |

� |

� |

|

Total Resources Available |

$81,190 |

$82,426 |

$83,790 |

|

Expenditures |

77,649 |

79,526 |

89,540a |

|

Ending fund balance |

$3,542 |

$2,899 |

-$5,751 |

|

Encumbrances |

929 |

929 |

929 |

|

Reserve |

$2,613 |

$1,971 |

-$6,680 |

|

Proposition

98 |

� |

(1,357) |

� |

|

Non-Proposition

98 |

� |

(614) |

� |

|

|

|||

|

a

Assumes that 2004-05 Proposition 98 reserve is appropriated. |

|||

Year-End Condition if Proposition 98 Not

Increased. If appropriations for Proposition 98

were not increased in the current year, spending in

the current year and budget year each would be reduced by

$1.4 billion. This would reduce the 2005-06 year-end

shortfall from the $6.7 billion shown in Figure 3

down to $3.9 billion.

Our revenue and expenditure forecasts are based primarily on the requirements of current

law, including constitutional and statutory funding requirements. Our estimates also reflect

projected changes in caseloads, federal reimbursements, and other factors affecting program costs. Of

special significance in the current forecast are our assumptions in the following three areas.

Governor's Higher Education

Compact. In the current forecast, we have not assumed the

Governor's "compact" with higher education, as the Legislature has taken no statutory action to

implement such an agreement. Rather, our estimates for higher education are based on projected enrollment

and inflation-related increases. Fully funding the compact would require added annual

expenditures beyond those we are projecting, reaching over $500 million by the final year of our forecast period.

Future Proposition 58 Transfers to the Budget Stabilization

Account. Proposition 58, approved by the voters in March 2004, created a Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) to cushion the state

against budget-related shortfalls. The measure provided for annual transfers of General Fund revenues to

the BSA, equaling 1 percent of General Fund revenues in 2006-07 (about $875 million), 2 percent

in 2007-08 (about $1.9 billion), and 3 percent in 2008-09 (about $2.9 billion) and thereafter until

the balance in the fund reaches $8 billion. The measure, however, allows the transfers to be suspended

or reduced through a Governor's executive order. Given the major budget shortfalls we are

already projecting in the out years, we have not included the added expenditures that would be needed

to fund the annual transfers to the BSA in our estimates.

Interaction of Proposition 98 With Revenue

Increases. Our baseline estimates include the

impacts of the current-year increase in revenues—and other factors—on the Proposition 98 spending

levels. This is consistent with language in Chapter 213, which was enacted with this year's budget.

However, given the increased General Fund shortfalls and increased pressures on non-Proposition 98

programs that would result from this use of revenues, we also show the outlook assuming no change

in 2004-05 Proposition 98 appropriations. Our estimates are not predictions of what the Legislature and Governor will adopt as policies

and funding levels in future budgets. Rather, our estimates are intended to be a reasonable

"baseline" projection of what would happen if current-law policies were allowed to operate in the future. In

this regard, we believe that our forecast provides a meaningful starting point for legislative

deliberations involving the state's budget.

Basis for Our Estimates

Projections, Not Predictions

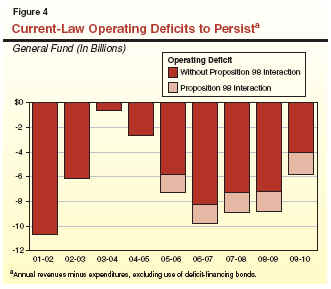

Our longer-term revenue and expenditure forecasts through 2009-10 are detailed in Chapters 3 and 4, respectively. Figure 4 shows the effects of these projections on the state's operating deficit—annual revenues minus expenditures—under two scenarios:

The state has been plagued with a large

structural budget shortfall since 2001-02, when

revenues plunged following the recession and the

steep decline in the stock market. The annual gap

between projected revenues and expenditures has been massive, reaching

as much as one-quarter of annual General Fund

spending. While the state has addressed the annual

shortfalls in each of the past three budgets, many of

the solutions have involved borrowing, spending

deferrals, accounting shifts, and other one-time

actions. As the benefits of these one-time solutions fell

away in subsequent years, the large underlying

structural shortfall reemerged.

The one-time and limited-term savings included in the 2004-05 budget are highlighted in

Figure 5. They include savings from deficit-financing bonds, pension obligation bonds, Proposition 42 transportation loans, postponement of

local mandate payments, and diversion of local

property taxes.

These actions, along with substantial borrowing undertaken in previous budgets, are resulting in

significant current and future General Fund costs.

As indicated in the accompanying box, annual General Fund costs related to budget borrowing

will peak at nearly $4 billion annually in 2006-07

through 2008-09, before trailing off somewhat in

subsequent years.

Figure 5 One-Time or Limited-Term

Solutions in 2004-05 Budget

Deficit-financing bond proceeds ($2 billion)

Proposition 42 transportation loan ($1.3 billion)

Diversion of local property taxes ($1.3 billion annually for two

years)

Pension obligation bond proceeds ($929 million)

Postponement of local mandate payments (about $200 million)

Suspension of teachers� tax credit (about $200 million annually

for two years)

Approaching the Budget Problem

As discussed above, our projections indicate that, absent corrective actions, the state will not resolve its structural imbalance. As a result, it is important that the Legislature take meaningful actions in 2005-06 to address this shortfall. In this regard, we believe that there are four basic "building-blocks" that should be considered in crafting a strategy for dealing with the budget shortfall in 2005-06:

While it is tempting to use deficit-financing bonds to avoid the more painful budget choices in 2005-06, making real changes in the budget year would enable the state to make meaningful progress toward eliminating the structural problem that has plagued the state since 2001-02.

Borrowing and the Budget ShortfallAs noted elsewhere in this report, we believe that the Legislature should minimize the use of budget-related borrowing in its solutions to the projected 2005-06 budget shortfall. The state has already accumulated $26 billion of outstanding budget-related debt, consisting of $18 billion in bonds, $4 billion in loans from local governments and schools, and about $4 billion in loans from transportation and resources special funds. This budget-related borrowing is in addition to the $40 billion in traditional borrowing used to finance new infrastructure. Borrowing Is a Temporary Fix . . .While budget-related borrowing enables the state to maintain funding for programs and avoid deeper cuts or revenue augmentations in the year in which it is undertaken, it is a temporary solution, which does nothing to address the ongoing mismatch between revenues and expenditures. . . . That Diverts Resources From Future BudgetsJust as importantly, the borrowing eventually becomes a drag on future budgets, as revenues are diverted from current programs to pay for past borrowing. As shown in the figure, the budgetary borrowing already undertaken will result in annual General Fund costs of nearly $4 billion for the 2006-07 through 2008-09 fiscal period. While the costs will drop off in subsequent fiscal years, they will remain above $2 billion annually until the Proposition 57 deficit bonds are repaid (anywhere from 2013 to 2018). Over the next several years, these budget-related borrowing costs will account for over 40 percent of the annual operating shortfalls that we are projecting. Additional debt will only add to the size of these future diversions, and will hamper meaningful progress toward resolving the state's ongoing structural shortfall.

|

Economic and demographic developments are important determinants of California's fiscal condition, mainly because of their impacts on state revenues and expenditures in such areas as education, health, social services, and transportation. This chapter presents our economic and demographic projections for 2004 through 2010, which will affect California's fiscal condition during fiscal years 2004-05 through 2009-10.

Despite sharply rising fuel prices and

somewhat uneven job gains, both the national and state

economies have experienced solid economic growth over

the past year. The gains have been fueled by strong

performances in interest-sensitive sectors such as

housing, as well as healthy gains in business capital

investment and continued strength in consumer spending.

Looking ahead, we expect economic growth to slow modestly in 2005 due to the constraining

impacts on the economy of high household debt levels, the rise in energy costs, and mild increases

in interest rates. In subsequent years, our outlook

calls for moderate expansion at both the national

and state levels. Figure 1 summarizes the details of

our economic forecasts for the nation and state. In

the subsequent sections, we discuss in more detail

major factors underlying our forecasts.

Figure 1 The LAO�s Economic

Forecast Percentage Change (Unless Otherwise Indicated) 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 United States Real gross domestic product 4.3% 3.4% 3.5% 3.3% 3.1% 3.2% 3.2% Personal income 5.3 5.0 5.4 5.6 5.8 6.0 6.2 Wage and salary jobs 1.0 1.6 1.2 1.1 1.0 1.0 1.0 Consumer Price Index 2.7 2.7 1.7 2.0 2.2 2.3 2.4 Unemployment rate (%) 5.5 5.4 5.6 5.6 5.6 5.6 5.5 Housing starts (000) 1,933 1,771 1,664 1,627 1,615 1,598 1,617 California Personal income 5.9% 5.5% 5.8% 6.1% 6.3% 6.3% 6.2% Wage and salary jobs 0.9 1.4 1.5 1.8 1.9 1.8 1.7 Taxable sales 6.5 5.6 5.6 6.0 6.5 5.8 5.7 Consumer Price Index 2.8 3.1 2.0 2.2 2.4 2.4 2.6 Unemployment rate (%) 6.1 5.6 5.4 5.4 5.5 5.5 5.5 Housing starts (000) 207 195 183 176 187 179 178

The national economy has experienced

broad-based economic growth over the past year.

Although the third quarter's real (that is,

inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product (GDP)

growth—initially reported at a 3.7 percent annual rate—was

modestly below expectations, the shortfall was

mainly related to less-than-expected accumulation of

business inventories, as opposed to a softening in

consumer or business demand.

Monthly information for October and early November suggests that solid economic growth is

continuing in the final quarter of 2004. After

several months of sluggish gains, job growth

rebounded sharply in October. Although some of the

increase was due to post-hurricane rebuilding activity in

the southeastern U.S., the October expansion was

widespread, affecting most major industry sectors.

Recent reports on retail sales, company profits, new orders

for manufactured goods, and consumer confidence,

also point toward healthy fourth-quarter economic

growth. Finally, the stock market, after lagging for much of

2004, jumped in early November, reflecting optimism

about future business sales and profits.

Although the near-term

outlook is clearly positive, the U.S. economy faces at least two

key challenges as of late 2004. These are high oil-related

prices—which are boosting the costs of gasoline and heating

oil—and the uneven job gains in 2004.

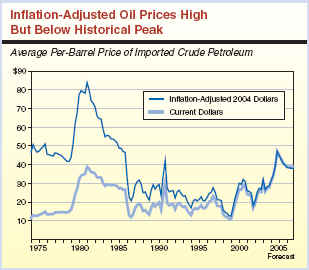

Oil Prices. As indicated in the accompanying box,

world oil prices have jumped dramatically in 2004,

having reached an all-time high of $55 per barrel in mid-October

before sliding back to slightly below $50 as of early

November. The oil price jump has had a major adverse impact on

prices paid by American consumers for gasoline, diesel fuel, heating oil, and other

oil-based commodities. It is also negatively affecting

consumer confidence, and will likely have a modest

negative impact on spending over the next year.

Jobs. Although the U.S. job report for

October was bullish, the employment gains over the past

year have been uneven, with businesses

relying on added hours and productivity gains from their

existing workforce rather than hiring additional

employees. This strategy has worked so far, yielding major gains

in business earnings, as well as higher wages for

some workers. However, the lack of broad-based job

growth remains a risk to the durability of the expansion,

in that, if continued, it may undercut consumer

confidence and spending throughout the economy.

After several years of relative stability, oil prices have soared in 2004, reflecting the impacts

of sharply rising worldwide demand, the lack of new production capacity, and numerous supply

disruptions in the Gulf of Mexico and abroad. As shown in the accompanying figure, the

per-barrel price of crude oil rose from $19 in early 2002 to $30 in early 2004, before soaring nearly to $50 in

the final quarter of the year. The increase in crude oil prices has in turn boosted retail prices of

gasoline—where the average per gallon price in late October surpassed $2 nationwide, and $2.40 in

California—as well as heating oil and a variety of other oil-based products.

The increases that have already occurred will have modest adverse effects on inflation and

real economic growth over the next year. Indeed, the modest economic slowdown we are projecting

in 2005 is partly related to the effects of higher energy costs on household confidence and

discretionary incomes. We do not, however, expect the negative economic impacts to be anywhere near as

dramatic as in the 1970s and early 1980s, when sharply rising oil prices sent the U.S. economy into two

recessions. The main reason is that, while oil prices are at an all-time high, they are nowhere near the

levels reached in 1980 in inflation-adjusted terms. As shown in the figure, in constant 2004 dollars,

oil prices peaked at more than $80 per barrel in 1981.

In addition, the consumption of oil-based products as a percentage of economic output

and income is less today than a quarter century ago, meaning that the proportional impact of any

given crude oil price increase is less today than in the past. A related factor is that the oil price increases

do not appear to be having the same type of

adverse "ripple" effects on other prices throughout

the economy as they did in the 1970s and early

1980s. Businesses have thus far managed to "hold the

line" on retail prices, due to offsetting savings related

to, for example, worker productivity increases.

Absent more broad-based increases in economy-wide inflation, it thus is

unlikely that the oil price increases will have the

dramatic negative impacts on interest rates and other

elements of the economy that they did in the 1970s.

Impact of High Oil Prices

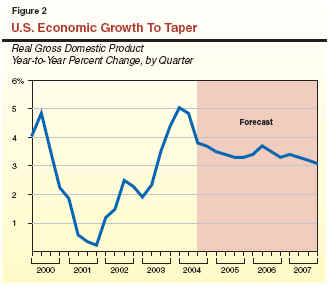

Our forecast assumes that the U.S. economy will expand at a solid though moderating pace in 2005. As indicated in Figure 2, we forecast that year-over-year increases in inflation-adjusted GDP will subside from the current 4 percent pace to around 3 percent by mid 2005, before accelerating modestly in 2006. This outlook assumes continued healthy increases in business investment, but slowing growth in consumer spending.

Our national outlook assumes that:

The California economy has experienced

generally healthy growth since mid-2003. The state

has faced challenges in many areas—most recently

being the major increase in gasoline costs.

However, most measures of statewide economic

activity—such as taxable sales, personal income, permits for

new construction, and company profit

reports—suggest that the state's economy is clearly on an upward

track as 2004 draws to a close.

Factors boosting economic growth over the past year have included:

Similar to the national pattern, we expect that California's economic growth will continue in 2005, although at a more moderate pace than in 2004. As indicated earlier in Figure 1, personal income is forecast to slow from 5.9 percent in 2004 to 5.5 percent in 2005, but then average over 6 percent for the balance of the forecast period. On the positive side, the national outlook for continued strong business investment will boost many industries in this state. On the negative side, however, we expect that high energy costs and rising interest rates will take a significant toll on consumer spending and housing activity in the state.

Employment Picture Mixed—Some

Improvement Expected. Over the past year, the

employment picture has been uneven. According to the

monthly survey of employers, payroll jobs (which

economists follow closely in gauging the strength of the

job markets) have increased by just 110,000

between September 2003 and September 2004, a growth

rate of just 0.8 percent. This is less than one-third

the number of payroll jobs that would normally be

expected at this stage of an expansion.

As we have indicated in previous forecasts, the separate survey of households (which is mainly

used to calculate the unemployment rate) shows

significantly more job growth. Using this alternative

measure, the total number of jobs in California has

increased by over 300,000 in the past year, a more

respectable 2 percent growth. The discrepancy

between the two job measures may reflect an

increase in the number of individuals working as

independent contractors. Such workers would be

counted in the household survey but not necessarily

included in the survey of employers. While the higher

job growth totals in the household survey is

encouraging, its exact implications for the economy are

uncertain. This is because little is known from

the household survey about the nature of the nonpayroll jobs—for

example, whether they are full or part time, or their pay and benefit

levels. In any event, the reluctance of employers to expand their

permanent work force remains a concern in the outlook.

Looking ahead, we forecast that job growth will

improve modestly, from 0.9 percent in 2004 to 1.4 percent in 2005

(an increase of 210,000 jobs), as businesses step up hiring

to meet continued growth in output and sales. Over the

2006-through-2010 period, job growth is forecast to

average 1.7 percent per year (about 240,000 jobs annually), a

rate that is roughly consistent with projected adult

population growth and thus labor force expansion.

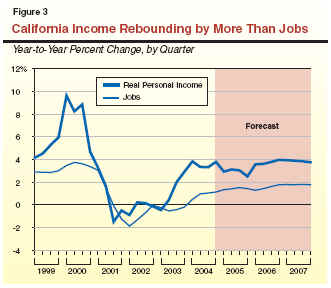

Personal Income Growth Has Been More

Positive. While California's job

performance has been disappointing, the recent rebound in personal

income has been more positive. As shown in Figure 3, after falling sharply in the 2001 recession, real

personal income growth jumped sharply to almost 4 percent

in early 2004, due to healthy increases in wages and

business earnings. Although we project a modest slowdown in

personal income during 2005, growth should remain in the solid

3 percent to 4 percent range through the forecast period.

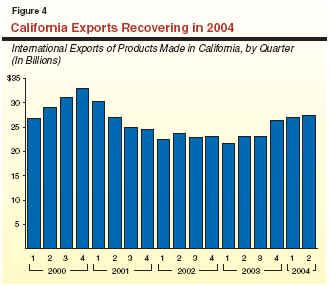

International Exports Finally

Improving. Exports are an important element

of California's economy. In 2003, international sales of

California-produced goods totaled about $95 billion, directly

accounting for about 7 percent of California's gross state

product. Over one-half of California's exports related to

high-tech goods, such as computers, electronics, and aerospace

products. Other key export categories include paper,

chemicals, and pharmaceuticals.

As shown in Figure 4, after lagging since 2001,

international exports jumped to a quarterly level of over $27 billion (over

20 percent growth) in the first half of 2004. Key factors

behind the growth are the declining value of the U.S.

dollar (which makes U.S. goods more competitive in

foreign markets), major growth in the economies of China and other developing nations on the

Pacific Rim, and a long-awaited acceleration in

Japan's economy. We expect export growth to continue

in 2005 and 2006, although at a slower pace than

in 2004.

A Key Factor In California's

Outlook—Housing. California's housing market has been booming,

as evidenced by record sales levels, dramatic price

increases, and strong levels of new construction. As

of September 2004, the median price of a detached single-family home in California was $465,000,

up over 20 percent from the prior year. Home

construction will likely exceed 200,000 units in 2004, the

strongest level in 15 years.

Our forecast assumes that prices will level off

and that sales and new construction will retreat

modestly from 2004 levels. As shown in Figure 5, we

assume that permits for new construction will fall slightly below 200,000 in 2005, and slide a bit

further to around the 180,000-to-190,000 range for

the remainder of the forecast period. Our forecast

assumes that interest rates will increase only

modestly, and that underlying population and income

growth result in continued strong demand for new

housing. This forecast is vulnerable, though, to a

larger-than-expected climb in interest rates. Given that

many recent home buyers are already financially

stretched by large mortgages, rising rates on variable

interest rate loans could further squeeze their

household budgets. For prospective buyers, such higher

rates would further reduce the affordability of new

homes, resulting in fewer sales and downward pressure

on home prices. These developments could depress

construction activity, and potentially reduce levels

of spending and income in other areas of the economy.

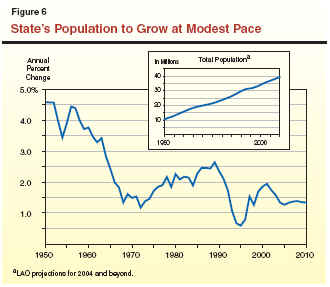

California's population currently totals

over 36 million persons. During the six-year forecast

period covered in this report, Figure 6 shows that the state's population growth is

projected to average about 1.3 percent annually. In terms

of numbers of people, this annual growth

translates into about half-a-million people and is

roughly equivalent to adding a new city the size of Long

Beach to California each year. As a result, California

will add roughly 3 million people over the forecast

interval and reach over 39 million by 2010.

The population growth rate we are projecting is somewhat slower than that experienced in the

late 1990s and early 2000s, when growth was

averaging about 1.6 percent. This reflects both the

dampening effects of the slower economy of recent years on

in-migration, plus a continuing downward trend in birth rates.

California's population growth can be broken

down into two major components—natural

increase (the excess of births over deaths) and

net in-migration (persons moving into California from

other states and countries, minus those leaving California for

out-of-state destinations). On average, these two components

have tended in the past to contribute about equally over time

to the state's population growth. However, their relative

shares can vary significantly from one year to the next

depending largely on the strength of the net in-migration

component—by far the most volatile element.

Natural Increase. We project that the

natural-increase component will average close to

300,000 new Californians annually over the forecast

period. This net natural gain reflects an annual average

of around 550,000 births partially offset by about 250,000 deaths.

Our forecast incorporates the well-documented trend of declining birth rates that has been

occurring for essentially all ethnic groups in recent

years in California. Despite these declining birth

rates, however, the number of new births in our

forecast actually trends up a bit through 2010. This is due

to significant growth in the female population of

child-bearing age groups in the faster-growing

segments of California's population, including Hispanic

and Asian women. As a result, even after accounting

for growth in the number of deaths occurring

annually in California, we project that the natural

increase component will grow slightly during the latter

half of the forecast period.

Net In-Migration. We project that combined

domestic and foreign net in-migration will average roughly 206,000 annually over the next six

years. This is weaker than during the latter half of the

1990s and early 2000s when annual net in-migration

averaged about 260,000. It also is considerably less

than the projected 300,000 natural-increase

component noted above.

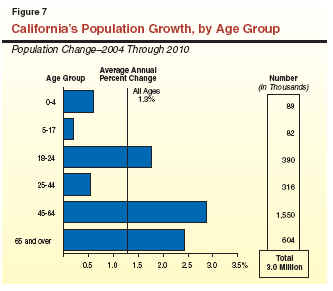

Figure 7 shows our population growth projections by broad age categories, including both numerical and percentage growth.

Baby Boomers Swelling 45-64 Age Group. The 45-to-64 age group

(largely the "baby boomers") continues to be by far the

fastest growing segment of the population. Nearly 1.6 million additional people are expected in

this age category over the next six years.

Slow Growth for Children. At the other

extreme, slow growth is anticipated for preschoolers and

the K-12 school-age population. This reflects several

factors. One is the movement of children of the

"baby boom" generation beyond the upper-end of the 5-to-17 age group, which partially explains the above-average growth in the 18-24 age

category. Other factors include the slower rate of net

in-migration, and the decline in birth rates in recent

years that has reduced the number of children

moving into the preschool and school-age categories.

These various age-group demographic projections can have significant implications for the

state's revenue and expenditure outlook. For

example, strong growth of the 45-64 age group generally

benefits tax revenues since this is the age category

that routinely earns the highest wages and salaries.

Likewise, the growth in the young adult population

affects college enrollments, while that for the

0-to-4 and 5-to-17 age groups drives K-12

enrollment growth.

The revenues that finance California's state General Fund budget come from numerous sources, including taxes, fees, licenses, interest earnings, loans, and transfers. However, over 90 percent of the total is attributable to the state's "big three" taxes—the personal income tax (PIT), the sales and use tax (SUT), and the corporation tax (CT). In this chapter, we summarize our updated General Fund revenue projections and provide detail behind our key revenue-related assumptions.

Before presenting our revenue forecast, it is first useful to review where things currently stand in terms of recent revenue-related trends that serve as the "springboard" to our revenue projections.

Total cash receipts from major taxes during the first four months of this fiscal year have exceeded the 2004-05 budget projection by over $900 million, largely reflecting much-stronger-than-expected CT receipts. Despite the mild slowdown in overall economic activity that we are projecting for 2005, we believe that the stronger revenue trend will hold through the remainder of this fiscal year, and that total revenues through June 30, 2005, will exceed the budget estimate by slightly over $2 billion. About $430 million of this increase is attributable to final returns for 2003 tax liabilities, and thus will be accrued back to 2003-04. The balance will be reflected as higher revenues in the current year.

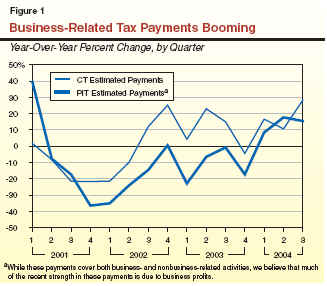

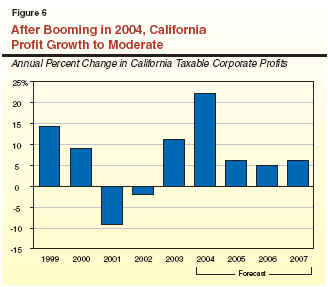

Figure 1 shows that estimated tax payments under the CT were up from the prior year by 28 percent in the third quarter of calendar-year 2004. These higher payments were primarily attributable to large increases by firms in the petroleum, finance, and high-tech manufacturing industries. The figure also indicates that PIT-related estimated tax payments were up by over 15 percent in the third quarter from the same time in the prior year. We believe that this increase was likewise due to strong business payments—in this case, those related to earnings of the subset of businesses that file under the PIT (such as S-corporations, partnerships, and sole proprietorships).

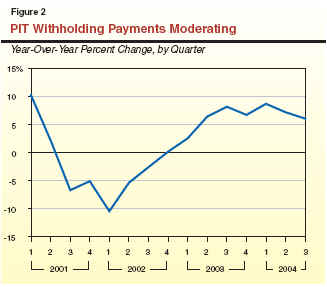

Revenue collections from other sources have been growing at a more subdued, but still healthy, rate in 2004. For example, Figure 2 shows that after a strong performance in late 2003 and early 2004, the growth in PIT-related withholding payments—which are attributable to employee wages, salaries, stock options, and bonuses—moderated to about 6 percent as of the third quarter of 2004. These recent increases are generally consistent with solid wage gains but relatively subdued employment gains over the past year. We believe that some of the recent slowdown is related to a slackening of stock option-related activity since the stock market peaked in early 2004.

Figure 3 presents our updated revenue projections for the period 2003-04 through 2009-10.

|

Figure 3 The LAO�s General Fund

Revenue Forecast |

|||||||

|

(Dollars in Millions) |

|||||||

|

Revenue Source |

2003-04 |

2004-05 |

2005-06 |

2006-07 |

2007-08 |

2008-09 |

2009-10 |

|

Personal Income Tax |

$36,200 |

$39,640 |

$42,210 |

$44,810 |

$47,960 |

$51,400 |

$55,050 |

|

Sales and Use Tax |

23,720 |

25,340 |

26,630 |

28,150 |

29,870 |

31,570 |

33,400 |

|

Corporation Tax |

7,480 |

8,730 |

9,170 |

9,730 |

10,270 |

10,860 |

11,510 |

|

Other Revenues and Transfers |

7,600 |

5,174 |

4,237 |

4,659 |

4,996 |

4,459 |

5,043 |

|

Total

Revenues and Transfers |

$75,000 |

$78,884 |

$82,247 |

$87,349 |

$93,096 |

$98,289 |

$105,003 |

|

(Percentage Change) |

� |

5.2% |

4.3% |

6.2% |

6.6% |

5.6% |

6.8% |

2003-04 Revenues. We estimate that revenues and

transfers totaled $75 billion in 2003-04. This is up $430 million from the 2004-05 budget

estimate. The increase is mainly due to

higher-than-expected payments related to CT and PIT final returns for 2003.

Even though many of these returns are filed in 2004-05,

under California's modified accrual system of revenue

accounting their associated payments are accrued back to 2003-04.

2004-05 Revenues. We project that revenues and

transfers will total $78.9 billion in 2004-05. This is up slightly

over $1.6 billion from the 2004-05 budget estimate. The

major taxes are up by $2 billion, mainly reflecting the

stronger-than-expected tax payments from business earnings

discussed above. Specifically, we estimate that CT taxes will be

up by about $1.2 billion in the current year and that PIT

revenues will exceed the budget estimate by about $670 million. We

also expect that sales taxes will exceed the budget estimate by just under $200 million.

The increase in major tax receipts will be

partly offset by lower receipts from nontax sources.

Specifically, we estimate that tribal gaming revenues

will total about $100 million in 2004-05 instead of

the $300 million anticipated in the budget. We also

expect that General Fund proceeds from asset sales will be $50 million, which is $164 million less

than assumed in the budget. Our estimates continue

to assume $560 million in General Fund revenues

from the sale of $950 million in pension obligation

bonds, which are subject to legal validation. (The

remaining portion of the bond proceeds shows up on

the expenditure side of the budget.)

2005-06 Revenues. We forecast that total

revenues and transfers will be $82.2 billion in 2005-06, a 2006-07 Through 2009-10. We project that

total revenues will increase at an average annual rate

of 6.3 percent, or slightly faster than the 6.1

percent average growth in personal income, during the

period. For this interval, we are projecting that

PIT revenues will grow moderately faster than the

overall economy, reflecting the interaction of rising

real incomes with California's progressive PIT rate

structure. In contrast, we are projecting receipts

from the remaining income sources to grow slightly slower than personal income during this period.

4.3 percent increase from the current year. This

relatively modest growth rate reflects the projected

economic slowdown in 2005 as well as a decline in

nontax revenues. As indicated in Figure 3, we estimate

that revenues from the major nontax sources will

fall from $5.2 billion this year to $4.2 billion next

year. This decline is related to the drop-off in

one-time revenues from pension obligation bonds, as well

as an assumed loan repayment to a transportation

special fund. Absent these special factors,

"underlying" revenues are expected to increase by a

moderately stronger rate of 5.8 percent.

The revenue totals shown in Figure 3 are affected by both the state's economy and numerous policy-related actions taken in conjunction with recent budgets. While the magnitude of these special factors in 2004-05 is considerably less than in the 2001-02 through 2003-04 period, they nevertheless will have a significant impact on both the revenue totals and the year-to-year changes in receipts for 2004-05 and beyond. Key examples of these special factors include:

As shown in Figure 4, special factors combined to raise General Fund revenues and transfers by about $4 billion in 2003-04 and by another $1.8 billion in 2004-05. In future years, the figure also shows that the impact of special factors will reduce annual revenues modestly, mainly because of the loan repayments that are due at various points in time.

We forecast PIT receipts will increase from $36.2 billion in 2003-04 to $39.6 billion in

2004-05. These estimates are up from the levels assumed

in the 2004-05 Budget Act by about $200 million

and $670 million, respectively. We project that PIT

revenues will grow moderately to $42.2 billion in 2005-06, and at an average annual rate of 6.9 percent during the balance of the forecast period.

Key Forecast Factors. Our upward PIT

revision from the 2004-05 Budget Act forecast is the net

result of three main factors:

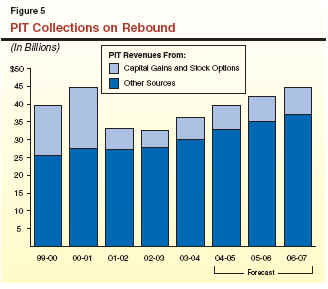

Capital Gains and Stock Options—Moderate Growth Assumed. Figure 5 depicts the important role that stock options and capital gains have played in the PIT revenue totals during recent years. It shows that the dramatic decline in revenues from these two sources—from nearly $17 billion in 2000-01 to below $5 billion by 2002-03—was the principal cause of the over-25 percent decline in total PIT collections during this period. It appears that revenues from these sources partially rebounded to $6.2 billion in 2003-04, but still remain at just over one-third of their 2000-01 peak. Looking ahead, we expect that revenues from these sources will grow by about 8 percent (to $6.7 billion) in 2004-05, and by roughly 6 percent to 7 percent in subsequent years, reflecting assumed moderate future gains in stock market valuations.

We estimate that SUT receipts will total $25.3 billion in 2004-05, a 6.8 percent increase from the

prior year. Our updated forecast is up by $194 million from the 2004-05 Budget Act. We

project that SUT receipts will grow further to $26.6

billion in 2005-06, and at an average annual rate of 5.8

percent during the balance of the forecast period.

Key Forecast Factors. The main determinant

of SUT receipts is taxable sales. About two-thirds

of these sales are related to retail spending by

consumers and the remainder is related to building

materials that go into new construction and to

business-to-business transactions.

Taxable sales grew by slightly more than 6 percent during the first half of calendar-year

2004, which was nearly double the pace for all of

2003. The main factors responsible for the

acceleration are: (1) increases in both the prices and sales

quantities of lumber and building materials, (2) the

sharp rise in gasoline prices, (3) strong increases in

equipment spending by businesses, and (4)

continued moderate growth in retail spending by

consumers. For 2004 as a whole, we project that taxable

sales will be up by 6.4 percent from the prior year.

Looking ahead, we anticipate that sales growth will

slow to 5.6 percent in 2005, reflecting the negative impacts

of higher interest rates and gasoline prices on both

consumer confidence and household spending on sales

of nongasoline goods. In subsequent years, we project

that taxable sales will increase at an average annual rate of

5.9 percent through the end of the forecast period. This

reflects moderate gains in consumer spending and

continued healthy growth in business investment.

We estimate that CT receipts will increase

from roughly $7.5 billion in 2003-04 ($200 million

more than assumed in the 2004-05 Budget Act) to $8.7

billion in 2004-05 (up by $1.2 billion from the

2004-05 Budget Act estimate). We forecast that CT tax

receipts will grow to $9.2 billion in 2005-06, and will increase at an

average annual rate of 5.8 percent during the remaining

four years of the forecast.

Key Forecast Factors. Two categories of

factors are of special importance in our updated forecast

of CT receipts:

Regarding NOL deductions, legislation

passed in conjunction with the 2002-03 Budget

Act suspended NOL deductions for both 2002 and

2003. This legislation, however, also reinstated the

deductions in 2004, with the percentage of losses that

can be deducted against future earnings

permanently increasing from 65 percent to 100 percent

effective beginning in 2005. These provisions raised

revenues by $600 million in 2003-04. We estimate that

the reinstatement and expansion of NOLs will

reduce collections by about $300 million in 2004-05 and

by modestly higher amounts in subsequent years. We would note, however, that there is considerable

uncertainty surrounding this estimate. This is

because the exact timing and amount of losses from

2002 and 2003 that will be used to offset future tax

liabilities is not known.

Regarding the MIC, the statute creating this credit in 1994 contained a provision stating that

the credit would sunset following any year after 2000

in which the cumulative growth in manufacturing

jobs (excluding aerospace) from 1994 was less than 100,000. Manufacturing jobs fell below this

threshold in 2003, triggering the expiration of the

MIC effective January 1, 2004. The elimination of

this credit boosted CT revenues by $40 million in

2003-04, $195 million in 2004-05, and by

additional annual amounts increasing to over $400 million

by the end of the forecast period.

This category encompasses all remaining

General Fund revenue sources. It includes taxes on

insurance, alcoholic beverages, estates, and

cigarettes. It also includes various fees, interest on

investments, asset sales, pension bond proceeds, as well as

loans and transfers from special funds. Absent special

factors, we would expect revenues from these

categories to currently total roughly $4.5 billion.

However, this category has been much larger in

recent years, due to various one-time solutions adopted

to address the budget shortfall.

As shown previously in Figure 3, combined receipts in this category totaled $7.6 billion in

2003-04, of which $2.2 billion was related to the

proceeds of a tobacco securitization bond sale. The

total drops off to $5.2 billion in 2004-05, reflecting

a smaller, though still significant, amount of

one-time revenues from pension bonds. Projected

revenues from the nonmajor tax sources falls further to $4.2 billion in 2005-06, and then fluctuates

between roughly $4.5 billion and $5 billion over the

balance of the forecast period. The annual totals shown

reflect steady-though-modest increases in tax and

fee revenues, and incorporate various scheduled

loan repayments from the General Fund to special

funds over time.

In this chapter, we discuss our General Fund expenditure estimates for 2003-04 and 2004-05, as well as our projections for 2005-06 through 2009-10. We first look at general budgetary trends and then discuss in more detail our expenditure projections for individual major program areas.

Figure 1 shows our forecast for major General Fund spending categories. We forecast that General Fund expenditures will grow from $79.5 billion in 2004-05 to $89.5 billion in 2005-06, an increase of 12.6 percent. Roughly one-half of this large increase is an anomaly related to one-time savings in 2004-05 that temporarily depress General Fund expenditures in that year. These savings include the use of deficit-financing bond proceeds to support General Fund programs, the assumed use of pension obligation bond proceeds to cover a portion of the state's retirement contributions, the deferral of mandate payments to localities, a deferral of Proposition 42 transportation payments, and a delay in cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) for CalWORKs and SSI/SSP recipients.

|

Figure 1 Projected General Fund

Spending for Major Programs |

|||||||||

|

(Dollars in Millions) |

|||||||||

|

|

Estimated |

|

Forecast |

Average

Annual Growth From |

|||||

|

2003‑04 |

2004‑05 |

2005‑06 |

2006‑07 |

2007‑08 |

2008‑09 |

2009‑10 |

|||

|

Education

programs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

K-14�Proposition 98 |

$30,277 |

$33,693a |

|

$36,300 |

$38,767 |

$40,252 |

$42,216 |

$43,831 |

4.8% |

|

CSU |

2,630 |

2,448 |

|

2,456 |

2,529 |

2,611 |

2,700 |

2,810 |

3.4 |

|

UC |

2,868 |

2,721 |

|

2,667 |

2,766 |

2,874 |

2,987 |

3,093 |

3.8 |

|

Financial aid |

672 |

637 |

|

839 |

892 |

952 |

1,007 |

1,047 |

5.7 |

|

Health

and Social Services |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Medi-Cal benefits |

$9,254 |

$11,214 |

|

$12,169 |

$12,858 |

$13,637 |

$14,416 |

$15,056 |

5.5% |

|

CalWORKs |

2,053 |

2,187 |

|

2,220 |

2,402 |

2,550 |

2,763 |

2,984 |

7.7 |

|

SSI/SSP |

3,157 |

3,474 |

|

3,740 |

4,032 |

4,296 |

4,559 |

4,847 |

6.7 |

|

IHSS |

1,117 |

1,181 |

|

1,330 |

1,483 |

1,649 |

1,829 |

2,025 |

11.1 |

|

DDS |

1,964 |

2,220 |

|

2,426 |

2,669 |

2,881 |

3,158 |

3,468 |

9.3 |

|

Other major programs |

5,005 |

5,107 |

|

5,670 |

5,871 |

5,873 |

6,107 |

6,346 |

2.9 |

|

Department

of Correctionsb |

$4,594 |

$5,557 |

|

$5,797 |

$6,074 |

$6,252 |

$6,414 |

$6,588 |

3.2% |

|

VLF-related

payments |

$2,839 |

� |

|

� |

$1,187c |

� |

� |

� |

� |

|

Prop

42-related payments |

$289 |

� |

|

$1,280 |

$1,351 |

$2,774 |

$2,459 |

$1,476 |

3.6% |

|

Local

mandate reimbursements |

� |

� |

|

$254 |

$588 |

$602 |

$616 |

$630 |

25.5% |

|

Retirement-related

payments |

$1,083 |

$1,901 |

|

$2,360 |

$2,574 |

$2,869 |

$3,157 |

$3,424 |

9.8% |

|

Debt

service |

$2,307 |

$3,538 |

|

$3,949 |

$4,411 |

$5,083 |

$5,657 |

$5,797 |

10.1% |

|

Deficit

bond proceedsd |

$2,012 |

-$2,012 |

|

� |

� |

� |

� |

� |

� |

|

Other

programs/costs |

$5,527 |

$5,660 |

|

$6,084 |

$6,661 |

$6,803 |

$7,071 |

$7,373 |

4.9% |

|

Totals |

$77,649 |

$79,526 |

|

$89,540 |

$97,114 |

$101,958 |

$107,115 |

$110,793 |

5.5% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

a

2004-05 total reflects appropriations to date. Reserve

funds for Proposition 98 total 1.4 billion. Projections for subsequent

years, however, assume that reserve funds are appropriated. |

|||||||||

|

b

Reflects employee compensation costs. |

|||||||||

|

c

VLF �gap� loan repayment to local governments. |

|||||||||

|

d

Of the amount authorized by the voters in Proposition 57,

about $3.5 billion remains available. |

|||||||||

Moderate Total Growth Projected. The right-hand column of Figure 1 shows our projected

average annual growth in expenditures for major

programs from 2005-06 through 2009-10. We forecast that total spending will increase by an average

rate of 5.5 percent over the period, or slightly less

than statewide personal income growth. This

average growth rate, however, masks divergent

trends among the different individual program areas

that make up the total. Annual spending totals

during the final four years of the forecast period are

affected by deferred payments to local governments and transportation special funds making

year-to-year comparisons difficult.

Highlights for Individual Program

Areas. With regard to some of the major individual

program areas in the budget, the figure shows that:

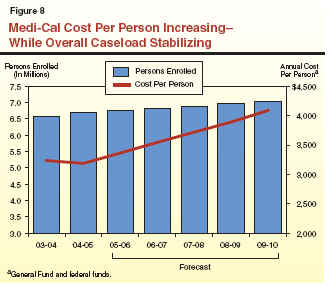

In the sections that follow, we provide a more detailed discussion of the expenditure outlook for these and other individual major program areas.

State spending for K-14 education (K-12

schools and community colleges) is governed largely

by Proposition 98, passed by the voters in 1988.

Proposition 98 is funded from the state General Fund

and local property taxes, and accounts for about

three-fourths of total support for K-14 education. The

remainder is from a variety of sources including

federal funds, lottery revenue, community college

fee revenues, and other local revenues. Generally,

the Proposition 98 guarantee is increased annually

by the growth in K-12 pupil attendance and the

growth in the economy.

California's public K-12 education system consists of more than 1,000 locally governed school

districts and county offices of education serving

about 6.3 million K-12 students. In addition, these

entities serve infants and preschool students receiving

child care and individuals in adult education

programs. The California Community Colleges (CCC)

provide instruction to about 1.2 million

full-time equivalent students at 109 colleges operated by

72 locally governed districts.

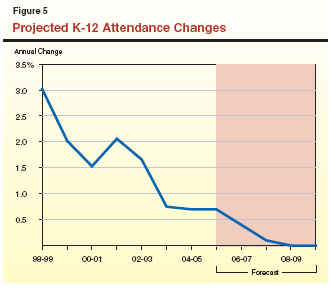

Figure 2 displays our projections of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee—as well as its General Fund and local property tax funding components—throughout the forecast period. The forecast shows steady increases in funding for K-14 education—between $2.5 billion and $3.2 billion in annual growth. Much of the cost of meeting the minimum guarantee is supported by increased local property tax revenues, which we forecast will grow by $1.2 billion to $1.3 billion annually.

|

Figure 2 The LAO Proposition 98

Forecast |

|||||||

|

(In Billions) |

|||||||

|

|

2004-05 |

2005‑06 |

2006‑07 |

2007‑08 |

2008‑09 |

2009‑10 |

|

|

Budget

Act |

Revised |

||||||

|

Proposition 98 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund |

$34.3a |

$35.1b |

$36.3 |

$38.8 |

$40.3 |

$42.2 |

$43.8 |

|

Local property tax |

13.0 |

13.2 |

14.6 |

14.6c |

15.7 |

17.0 |

18.2 |

|

Totals |

$47.3a |

$48.3b |

$50.9 |

$53.3 |

$56.0 |

$59.2 |

$62.0 |

|

Growth |

� |

� |

$2.6 |

$2.5 |

$2.7 |

$3.2 |

$2.8 |

|

|

|||||||

|

a

Assumes appropriation of a $302 million Proposition 98 reserve. |

|||||||

|

b

Assumes appropriation of a $1,357 million Proposition 98 reserve. |

|||||||

|

c

The state will transfer $1.3 billion of local property tax

revenues from schools to local governments in 2006-07. This transfer

roughly offsets the growth of local property taxes for schools in this

year. |

|||||||

Forecast for the Prior Year. An increase in 2003-04 General Fund revenues (see Chapter 3)

results in a $210 million increase in the

Proposition 98 minimum guarantee for that year. The state

will eventually have to provide the additional

$210 million to "settle up" the Proposition 98 guarantee

for 2003-04. However, as part of the budget package

for 2004-05, Chapter 216, Statutes of 2004 (SB

1108, Budget Committee), delayed all settle-up

obligation payments for fiscal years 1995-96 through

2003-04. The delay effectively transforms these

obligations into a loan from Proposition 98 to the General

Fund. Chapter 216 establishes a repayment plan for

this loan, providing $150 million annually beginning

in 2006-07 until the loan is repaid. The estimated

increase of $210 million we forecast is on top of

$1 billion the state already owes to Proposition 98 for

these prior years.

We estimate that local property tax revenues

for 2003-04 increased by $135 million. These

additional funds will reduce the General Fund costs of

Proposition 98 for 2003-04 by a similar amount.

Forecast for the Current Year. Chapter 213,

Statutes of 2004 (SB 1101, Budget Committee), suspended the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee

for 2004-05, providing for spending that is

$2 billion less than would otherwise be required. We

project the 2004-05 suspension will result in annual

savings, growing from $2 billion in 2004-05 to

$2.5 billion by the end of the forecast period. When the

budget was adopted, the state assumed that the

Proposition 98 minimum guarantee would have

been $49.3 billion. Given the suspension, the 2004-05

budget package included $47.3 billion in

Proposition 98 funding (recognizing a $302 million

Proposition 98 reserve).

If the state is to meet the target of providing $2 billion less than the Proposition 98 guarantee,

we estimate it would now need to appropriate an

additional $1.4 billion in 2004-05. Figure 3

summarizes the components of this increase. First, the

Legislature would need to appropriate the $302 million

in the Proposition 98 reserve. Second, we now

forecast that the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee has

increased by $986 million since the budget

was adopted. The increase in the minimum guarantee

is the net effect of two main factors—additional

General Fund revenues and lower K-12 attendance.

We estimate that 2004-05 General Fund tax revenues are $2 billion higher than assumed in the

2004-05 budget package, and that attendance growth is

about a quarter percent lower than assumed in the

budget. Finally, we estimate that forecasted

2004-05 Proposition 98 spending will fall by around

$70 million because lower K-12 attendance growth will

reduce the continuous appropriation for school districts' and county office

of educations' revenue limits. Since less

Proposition 98 resources will be spent on revenue limits, the

state would need to reallocate the $70 million for a

different K-14 use. For purposes of this forecast, we

assume the Legislature provides the additional

$1.4 billion in funding in 2004-05, building the base upon which future Proposition 98 funding increases are added. However,

in the nearby box, we discuss options that the

Legislature has to address current-year Proposition 98

funding given the state's overall fiscal condition.

Figure 3 Additional K-14 Spending

Needed (In Millions) 2004‑05 Budget Act Proposition 98

reserve $302 Increase in guarantee 986 Revenue limit adjustment 70 Total $1,357 a

Assuming the state provides $2 billion less than the minimum

guarantee, per Chapter 213, Statutes of 2004.

Chapter 213 suspended the Proposition 98 guarantee for 2004-05. It also included language that

the state would provide $2 billion less than required by the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee.

Chapter 213, in effect, signals the intent of the Legislature to appropriate additional funding if the

Proposition 98 guarantee increases (as we are forecasting). Because the statute does not provide specific

appropriation authority to meet this requirement, the Legislature would have to take positive action in

the future to do so. Absent such action, the minimum guarantee would "default" to the current level

of appropriations. Because of the language in Chapter 213, we developed our Proposition 98 forecast

assuming that the Legislature would appropriate an additional $1.4 billion in the current year. This amount

increases the Proposition 98 base, resulting in comparable increases in each out-year of the forecast.

Given the state's projected large, ongoing budget problems (see Chapter 1) and the suspension

of the guarantee which has already occurred, we would encourage the Legislature to reconsider the

funding goal laid out in Chapter 213 and instead leave 2004-05 Proposition 98 funding at its current level

of appropriations. (This could be accomplished either by specifically amending Chapter 213 or by

simply not making additional Proposition 98 appropriations in the current year.) This option would

save $2.8 billion in 2004-05 and 2005-06 combined, yet would not reduce the current level of

educational services. In 2005-06, the increase in the Proposition 98 guarantee would fully fund the base program

as adjusted for growth and cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) and still support limited additional

spending. In the out-years of the forecast, Proposition 98 would provide enough to pay for growth

and COLAs, eliminate the education credit card debts (discussed later in this section), and begin to

expand K-14 programs. While we recognize there are a range of options which the Legislature could

consider regarding Proposition 98 in the current year, we believe this option would not only provide for

reasonable growth in school spending, but would reduce the pressure to suspend Proposition 98 again in

the near future. Forecast for the Budget Year. For 2005-06, we

estimate the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee

will total $50.9 billion. This is $2.6 billion

(5.4 percent) more than we forecast for 2004-05, and

$3.9 billion (8.3 percent) more than provided in the

2004-05 Budget Act. For 2005-06, we forecast that K-14

local property tax revenue will increase by

$1.35 billion. Thus, General Fund costs of meeting the

Proposition 98 minimum guarantee will grow by

$1.25 billion (3.4 percent) from the revised 2004-05

estimate. The slow growth in General Fund costs is a

combination of fast growth in local property tax

revenues and slow K-12 attendance growth.

Out-Years' Forecast. For the remainder of

the forecast period, we estimate that annual growth

in total Proposition 98 spending will average

$2.8 billion (5.1 percent). Strong property tax growth

averaging $1.2 billion annually (8.2 percent) helps

reduce the impact on the state budget, resulting

in General Fund support for Proposition 98

growing around $1.6 billion annually (4 percent).

Proposition 49 Trigger. Approved by voters

in 2002, Proposition 49 requires that the state

appropriate additional funding for after school

programs beginning in 2004-05 if certain conditions are

met. Specifically, the state must appropriate up to an

additional $428 million for after school programs

if total state spending reaches a specified

threshold. Based on our revenue forecast, the state would

not be required under Proposition 49 to augment

after school programs until 2008-09. When the trigger

is reached, Proposition 49 requires that the

additional $428 million be appropriated

above the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. The additional

costs of funding Proposition 49 are factored into

the Proposition 98 growth estimates in Figure 2

starting in 2008-09.

Key Forecast Factors. General Fund

expenditures for Proposition 98 depend on a variety of

factors—including K-12 average daily attendance (ADA),

per capita personal income, per capita General

Fund revenues, and local property taxes. Figure 4

summarizes our assumptions for these factors and

the K-12 COLA rate.

Figure 4 The LAO Proposition 98

Forecast Factors 2004‑05 2005‑06 2006‑07 2007‑08 2008‑09 2009‑10 Proposition 98 �Test� 2 2 2 2 2 2 Annual Percent Change K-12 average daily attendance 0.7% 0.7% 0.4% 0.1%

�

� Per capita personal income 3.3 4.6 4.3 4.6 4.8% 4.9% Per capita General Fund 7.2 4.4 4.4 5.0 5.0 5.0 State population 1.3 1.3 1.4 1.4 1.4 1.4 Local property taxes 9.4a 11.0 9.6a 8.2 7.8 7.0 K-12 COLA 2.4 3.4 3.0 2.6 2.8 2.9 a

Growth rates in 2004‑05 and 2006‑07 reflect the

underlying growth in school districts and community colleges property

tax revenues.

For our forecast:

To Meet Proposition 98 Targeta

Legislature's Current-Year Proposition 98 Options

The state has four main cost pressures to

continue currently required K-14 services over the

forecast period:

(1) growth in K-12 and community college attendance, (2) COLAs, (3) funding ongoing programs for which one-time funds were used in 2004-05, and (4)

funding Proposition 49 after school programs.

Figure 6 shows the annual growth in Proposition 98

resources over the forecast period, and the amount needed to fund these increases in base program costs.

|

Figure 6 Proposition 98 Funds

Available After Maintaining Base Programa |

||||||

|

(In Millions) |

||||||

|

|

2004-05 |

2005-06 |

2006-07 |

2007-08 |

2008-09 |

2009-10 |

|

Resources |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Increases in Proposition 98 funding |

$1,357 |

$2,593 |

$2,450 |

$2,674 |

$3,186 |

$2,809 |

|

Base Program Needs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Growth and COLA |

� |

$2,186 |

$1,842 |

$1,693 |

$1,487 |

$1,511 |

|

Backfill for one-time spending |

� |

279 |

� |

� |

� |

� |

|

Proposition 49 |

� |

� |

� |

� |

428 |

�b |

|

Funds available for other purposesc |

$1,357 |

$129 |

$608 |

$981 |

$1,271 |

$1,299 |

|

|

||||||

|

a

Assuming the state provides $2 billion less than the minimum

guarantee, per Chapter 213, Statutes of 2004. |

||||||

|

b

Proposition 49 funded as part of base program beginning this

year. |

||||||

|

c

Such as program expansions or reductions in existing K-14

obligations. |

||||||

Proposition 98 Will Provide Significant Resources Beyond the Base Program. As Figure 6 also shows, Proposition 98 will provide significant new resources beyond those needed to maintain the base program. However, the state created large K-14 fiscal obligations for future years while addressing state budget problems in 2002-03 and 2003-04. Specifically, the state relied heavily on (1) one-time solutions, (2) borrowing from the future by deferring appropriations to future years to support current costs, and (3) a large limited-term reduction in general purpose funding for K-12. The 2004-05 budget provided some funding beyond base program growth and COLAs , but did not begin to address the overall size of these obligations to K-14 education. We have termed these obligations the "K-14 education credit card." Figure 7 shows that the state will face a credit card balance of almost $3.5 billion in K-14 costs in 2005-06, absent corrective actions.

|

Figure 7 K-14 Education Credit Card

Balance |

|

|

(Year-End Balance in Millions) |

|

|

|

2004‑05 |

|

One-Time |

|

|

Revenue limit and categorical deferrals |

$1,083 |

|

Community college deferrals |

200 |

|

Cumulative mandate deferrals |

1,524 |

|

Ongoing |

|

|

Revenue limit deficit factor |

$643 |

|

Total |

$3,450 |

These credit card costs include program funding deferrals, mandate deferrals, and K-12 revenue

limit "deficit factor." This latter obligation was

created when the state temporarily reduced revenue

limit payments to K-12 districts by $643 million in 2003-04. By 2006-07, current law requires the

state to provide the additional $643 million in

revenue limit funding.

Proposition 98 Growth Will Allow for

Program Expansion After Meeting Current

Obligations. If the Legislature meets the Proposition 98 target in

Chapter 213, providing an additional $1.4 billion in 2004-05, the growth in Proposition 98 funding

over the forecast period would allow the state to

maintain the base program and completely eliminate

the education credit card by 2006-07. This

scenario would leave significant resources for program

expansion. Alternatively, if the Legislature

maintains the current Proposition 98 funding level, the

state could still maintain the base program, eliminate

the credit card, and expand programs over the

forecast period. However, the level of program

expansion would be somewhat less.

In addition to community colleges, the

state's public higher education system includes UC

and CSU. The UC consists of nine general campuses

(including a new campus at Merced, which is

scheduled to open in fall 2005), one health sciences

campus, and numerous special research facilities. The

UC awards bachelor's, master's, and doctoral

degrees, as well as various professional degrees. Of the

segments, UC has almost exclusive jurisdiction

over public university research. The CSU consists of

23 campuses and several off-campus centers. The

CSU grants bachelor's and master's degrees and may award joint doctoral degrees with UC under

specified circumstances. Overall, state policy for

higher education is laid out in its Master Plan for

Higher Education, which was originally adopted in 1960.

The Spending Forecast. Our forecast assumes

cost increases which fully fund the projected impacts

of inflation and enrollment growth. As a result,

the segments' budgets grow by an average annual

rate of about 4.2 percent over the forecast period.

General Fund costs, however, grow somewhat more slowly, due to new revenue from the gradual

phase-in of an excess unit surcharge on students

(adopted as part of the 2004-05 budget). Including the

offsetting effect of that revenue, we project that

General Fund spending will increase from $5 billion in 2004-05 to $5.9 billion in 2009-10, for an

average annual increase of 3.8 percent over the period.

Key Forecast Factors. Our forecast is largely

based on three key factors.

Governor's

Compacts. Earlier this year the Governor

developed "compacts" with UC and CSU in which

he commits to seek certain funding increases for

the segments in his future budget proposals.

Because these compacts are neither in statute nor

formally endorsed by the Legislature, we have not

reflected them in our projections for spending at UC and

CSU. The nearby box explains the compacts in more

detail.

Cal Grant Costs Likely to Increase

Substantially. We estimate that General Fund spending for

financial aid programs administered by the Student

Aid Commission will increase from $637 million in 2004-05 to approximately $1 billion in 2009-10.

The bulk of the expected increase is attributable

to growth in the Cal Grant entitlement program, as well as our assumption that all Cal Grant

funding will be covered by General Fund revenue starting

in 2005-06. (In 2004-05, $147 million of Cal Grant

funding is being covered by surplus revenue

available from the Student Loan Operating Fund.) Since

2001-02, the Cal Grant entitlement program has

guaranteed financial aid to recent high school

graduates and community college transfer students under

24 years of age. Because it is still relatively new,

future participation rates remain uncertain. Over the

forecast period, our projections assume that student

participation will continue to grow somewhat

faster than student enrollment.

In May of this year, the Governor and the heads of UC and CSU agreed to pursue specific

annual funding goals for the university systems over the next six years. These goals were expressed in

"compacts," whereby the Governor committed to include the specified funding levels in his annual

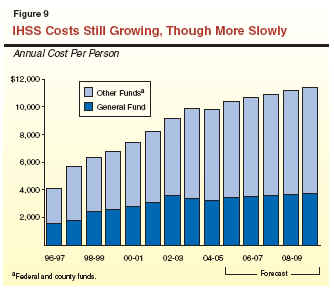

budget requests, and the segments agreed to provide annual reports on a variety of activities and