January 31, 2005

In the past few years, workload increases for the California Highway Patrol (CHP) have outpaced growth in staffing levels of road patrol (traffic) officers. In particular, the recent upsurge in the number of traffic accidents occurring in CHP's jurisdiction has limited the department's ability to conduct proactive patrols and enhance the levels of service that it provides to the motoring public. Given these developments, this report recommends a number of actions to improve the efficiency of the department in order to enhance its road patrol service.

The California Highway Patrol (CHP) is responsible for providing a number of services to the state. The CHP's core mission is to ensure safety and enforce traffic laws on approximately 100,000 miles of roadways. The CHP's jurisdiction includes all state highways (interstate routes, U.S. highways, and state routes), as well as county roads in unincorporated areas. (Local police departments patrol incorporated areas of the state, and sheriff's offices enforce primarily nontraffic-related laws in unincorporated areas.) Road patrol (traffic) officers drive their enforcement vehicles "in view" of the public in order to reduce the incidence of accident-causing behavior among motorists, remove congestion- and accident-causing impediments from roadways, respond to accidents when they do occur, and provide various other types of services and assistance to the public. In addition to road patrol, the department promotes traffic safety by inspecting commercial vehicles operating on state highways as well as inspecting and certifying school buses, ambulances, and other specialized vehicles.

The CHP carries out a variety of other mandated tasks related to law enforcement, including investigating vehicular theft and providing backup to local law enforcement in criminal matters. Since 1995, when the California State Police was consolidated into the CHP, the department has provided protective services for state employees and property. The CHP's responsibilities have expanded further since September 11, 2001, with the department playing a major role in the state's enhanced security activities.

Most of CHP's operations are funded from the Motor Vehicle Account (MVA), which derives its revenues primarily from vehicle registration and driver license fees. In 2004-05, CHP's expenditures total about $1.4 billion.

In this report, we look at trends in staffing and workload in the road patrol program.

We find that recent increases in the number of

traffic accidents combined with relatively little

growth in road patrol staffing have resulted in

officers spending increasing amounts of their work hours

responding to accidents rather than conducting proactive patrols and

providing enforcement and other safety-related

services to the public. In order to better promote

traffic safety in the state, this report identifies a

number of measures that the Legislature can direct

the CHP to adopt to achieve considerable program efficiencies and cost effectiveness.

These include: (1) reducing workload by modifying

the department's accident-reporting policies;

(2) streamlining the department's record-keeping processes; (3) pilot testing the use

of nonuniformed staff for certain activities in

the road patrol program; and (4) redirecting

certain nonpatrol uniformed staff to road patrol duties.

Currently, the CHP's overall level of staffing is about 10,300. The department is comprised of uniformed (sworn) and nonuniformed (nonsworn) personnel, with uniformed personnel accounting for approximately 7,200 positions, or 70 percent of total staff. Of the uniformed personnel, 85 percent (6,100) are officers and 11 percent (800) are sergeants. Middle and upper management personnel (lieutenants through the commissioner) make up the remaining uniformed positions. Roughly two-thirds (4,700) of CHP's overall uniformed personnel carry out road patrol duties. The remaining uniformed personnel (2,500) perform various nonpatrol functions for the department.

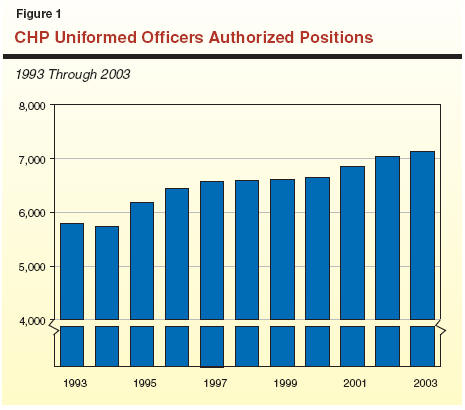

Recent Personnel Growth Largely in Nonpatrol Programs . . . As Figure 1 displays, CHP's uniformed staffing levels have increased considerably in the past decade. In 1993, a department-wide hiring freeze limited CHP to 5,800 uniformed personnel, including about 4,200 personnel for road patrol duties. The following year, the Legislature authorized an increase of 500 uniformed staff over a three-year period. In 1995, CHP added 270 additional protective service positions as a result of the consolidation with the California State Police. The number of uniformed staff also grew in the 1990s due to workload increases in the vehicle inspection and theft programs. As a result of the September 11, 2001 attacks, over 300 additional uniformed positions were added for homeland security duties such as protecting bridges and serving on various antiterrorism task forces.

Overall, levels of authorized uniformed staff have increased by approximately 1,400 officers (24 percent) since 1993. However, two-thirds (900) of these new positions have been designated for nonpatrol functions such as protective/security services. The road patrol program has been the recipient of roughly one-third (500) of the additional uniformed staff since 1993, which represents an increase in traffic officers of 12 percent.

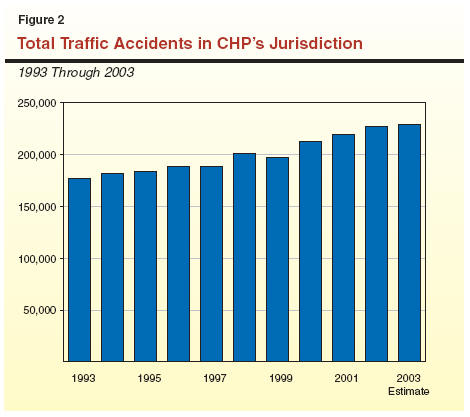

. . . While Workload in Road Patrol Program Soars. From 1993 through 2003, CHP experienced a substantial increase in road patrol workload. The most significant component of workload growth for road patrol officers involves responding to traffic accidents. Since 1993, the number of accidents occurring in CHP's jurisdiction has increased by almost 30 percent, or 52,000 accidents. As Figure 2 shows, total accidents increased modestly from 1993 through 1997. In 1998, however, the number of accidents on highways and county roads jumped to just over 200,000. After declining slightly the following year, accidents in 2000 increased by almost 16,000 (8 percent) over 1999. The number of traffic accidents in CHP's jurisdiction has continued to rise each year since 2000, with totals reaching unprecedented levels of 227,000 in 2002. The CHP estimates accident totals for 2003 to be even higher. (At the time this report was prepared, CHP still did not have actual data for 2003.)

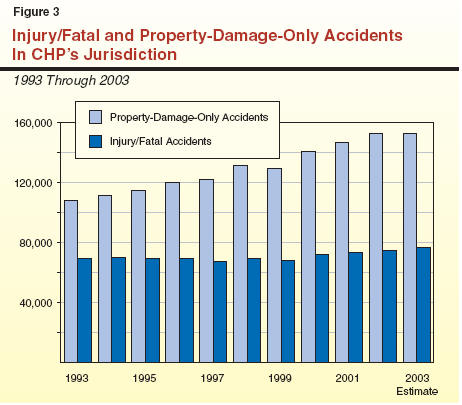

As Figure 3 displays, the increase in accident-related workload has occurred "across the board"—for all categories of accidents including property-damage-only accidents as well as for accidents resulting in injury and death. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration cites the increased number of motorcycles and sports utility vehicles operating on state roadways as key factors influencing the overall growth of accidents in recent years. Increased use of cellular phones and other in-vehicle technology by drivers may also contribute to the increase in accidents. As Figure 3 also shows, the increase in accidents involving property-damage-only has been significantly greater than the increase in more serious types of accidents. Due in part to the proliferation of safety devices in vehicles such as air bags, property-damage-only accidents increased by 40 percent from 1993 through 2003, as compared with a 10 percent increase in injury/fatal crashes.

Increase in Time Spent on Accident Response . . . Departmental policy requires officers to investigate and file a written report on every traffic accident to which they respond. These investigations, even for relatively minor "fender-bender" accidents, are time-consuming tasks for road patrol officers. Data provided by CHP show that the average noninjury investigation takes over two hours to complete. Collisions resulting in injury or death average almost seven hours of investigative and reporting time. Since the late 1990s, the total amount of time officers spend annually on accident-related investigations and reporting has increased about 170,000 hours (25 percent), from 680,000 hours in 1999 to 850,000 hours in 2003—the equivalent of approximately 98 personnel-years (full-time officer positions). This does not include the increase in time officers now spend directing traffic at crash scenes.

. . . Means Less Time for Safety-Enhancing Proactive Patrols. Increased numbers of accidents have limited considerably the amount of time CHP can spend on proactive enforcement efforts, in which officers drive their marked patrol vehicles in view of the motoring public. This is because obligations to respond to, investigate, and file reports on large numbers of traffic accidents reduce the time that officers have available to patrol the roadways. Yet, the department maintains that proactive patrols are a vital means of promoting traffic safety because they serve as an effective deterrent to unsafe driving, as well as provide opportunities for officers to identify and address in a timely fashion dangerous situations such as moving violations, debris, and disabled vehicles on the roadways.

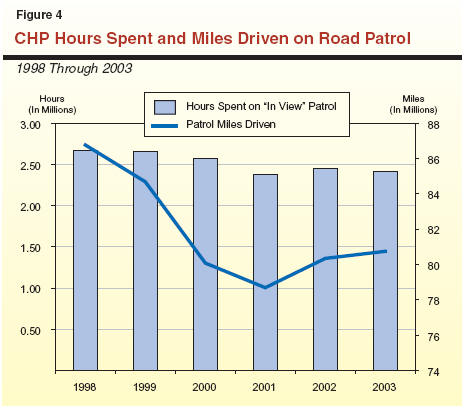

As Figure 4 shows, the extent of proactive patrolling by CHP has declined markedly within the last few years. In fact, the total number of hours officers spend on in-view patrol has decreased from 2.7 million hours in the late 1990s to 2.4 million hours in 2003—a reduction of about 9 percent. Annual patrol miles driven by traffic officers, meanwhile, have dropped from 87 million to less than 81 million miles, while miles driven by motorists have increased every year.

The reduction of in-view patrol and miles driven in 2001 is due in part to the temporary redirection of some officers from road patrol to homeland security duties after September 11, 2001. The addition of new officer positions dedicated to security activities in 2002 and 2003 allowed the department to return redirected officers to road patrol, though increased accident workload in those years limited CHP's ability to attain patrol levels of the late 1990s.

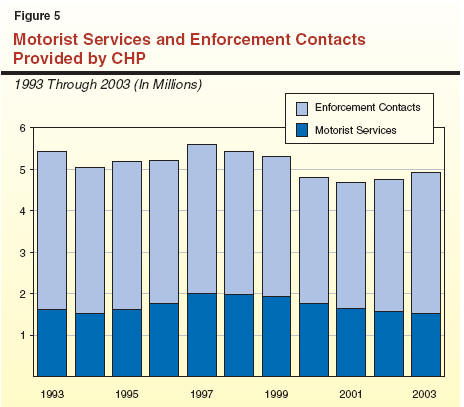

As a result of the reduction in proactive patrolling, the overall level of traffic services and enforcement that CHP provides to the public has fallen, as displayed in Figure 5. Since the late 1990s, the number of motorist services performed by road patrol officers—which includes aiding stranded motorists and removing hazards from the roadways—has decreased by over 20 percent. In addition, the combined number of enforcement contacts (arrests, citations, and written and verbal warnings) initiated by officers in recent years is below levels the department achieved throughout most of the 1990s.

"Vicious Circle" Not Likely to Abate Without Action. The continued increase in traffic accidents has created a vicious circle for the department: the increase in accident workload lessens opportunities for officers to perform proactive patrols, and thus their availability to perform motorist services and enforcement contacts like removing unsafe debris and dangerous drivers from the highways—which in turn may result in additional accidents. Absent corrective measures, it is unlikely that CHP's ability to promote traffic safety will improve. As the state's population continues to increase, use of state and county roadways by motorists will likely grow—resulting in a greater probability of breakdowns, traffic hazards, moving violations, and other situations requiring CHP's services.

Our review shows that there are a number of measures which could be adopted to improve CHP's road patrol program. These measures entail primarily a more efficient use of existing resources, including modifying work processes and shifting certain responsibilities from uniformed to nonuniformed personnel. Under the terms of the existing collective bargaining agreement, it would appear that some of these personnel changes could require consultation with the officers' union.

As noted earlier, current departmental policy requires road patrol officers to investigate and complete a written report on every traffic accident to which they respond. Officers must record each party's personal information (such as names and contact information of drivers and passengers, driver license information, and insurance information) and obtain statements from participants and witnesses. The accident report must also include a narrative that summarizes the circumstances and causes of the crash. Depending on the severity of the collision, officers may also be required to include a detailed diagram of how the accident occurred, as well as describe all pertinent physical evidence. The investigations are usually conducted at the crash scene, while reports are written either at the area office or in a safe location off the roadway. After completing the report, at least one other officer reviews it for clarity and completeness. The report is then made available to interested parties to the crash, particularly the motorists and their insurance companies.

Hundreds of Thousands of Officer Hours Spent on Accident Reports. The CHP spends a significant amount of time and resources on these investigations and reports. In 2003, road patrol officers spent a combined 525,000 hours—the equivalent of 300 personnel-years—completing 76,000 injury and fatal collision reports. In addition, they spent a combined 325,000 hours—the equivalent of 185 personnel-years—writing reports on 150,000 property-damage-only accidents.

Yet, current law does not require CHP or any other law enforcement agencies in the state to take reports on property-damage-only collisions; reports are only required for accidents involving injuries and fatalities. In fact, many local law enforcement agencies, including the Cities of Los Angeles and Sacramento, do not require their officers to take reports on property-damage-only collisions if they do not involve extenuating circumstances such as unlicensed, uninsured, or intoxicated drivers. Instead, city police usually instruct the parties to exchange pertinent information, notify the Department of Motor Vehicles (if property damage to either vehicle exceeds $750), and contact their insurance companies for further investigation and resolution of the matter. By contrast, the only circumstance in which CHP officers are instructed not to take a formal report is if the parties to a property-damage-only collision insist on taking care of the matter themselves by exchanging information. However, current departmental policies forbid road patrol officers from suggesting this option to the parties.

Changing Accident Reporting Could Free Up Officers for Road Patrol. Given its substantial accident-related responsibilities, we recommend the enactment of legislation that directs CHP to modify its accident-reporting policy in a way that reduces officers' workload without compromising public safety. For example, if patrol officers offered parties to a property-damage-only accident assistance with exchanging information—rather than the current default policy of taking a formal collision report—more time on each shift would be freed up for officers to devote attention to higher priority matters. Annually, this could free up to 185 personnel-years in resources to perform proactive patrol.

Like most law enforcement agencies, CHP tracks closely the activities of its officers in the field. Road patrol officers are required to communicate frequently with dispatchers and supervisors regarding their whereabouts and activities. For this purpose officers use their two-way radio or laptop computer, which can be mounted in their patrol vehicle. Officers are also responsible for ensuring that detailed records of each shift are kept for payroll, performance evaluations, and other purposes.

Record-Keeping System Paper-Intensive, Time-Consuming, and Inefficient. Our review finds, however, that CHP's time and record-keeping procedures for road patrol officers are time-consuming and inefficient. The paper-intensive system slows down officers and limits their ability to move quickly onto their next activity. In addition, it requires officers to spend too much of their time—particularly toward the end of their shift—completing paperwork. For instance, officers must record by hand each activity (such as accident investigations, motorist services, and arrests) they perform on their shift log, even though their activities are also recorded on the dispatcher's computer log. At the end of their shift, officers must count the number of times they performed each activity, as well as add up the total amount of time spent on these activities. Officers record by hand this information on their shift log, along with the total hours worked on their shift. Officers routinely ask for a copy of the dispatch log to complete their shift log. Officers must then transcribe the activity data from their shift log onto a separate Activity Summary Form. Officers must also complete by hand a Supplemental Daily Field Record, which requires them to record the race, gender, age, and other information of each member of the public with whom they came into contact while on patrol.

Paperwork Reduces Roadway Patrol, Particularly Between Patrol Shifts. Based on our field observations and discussions with CHP staff, it appears that road patrol officers can spend up to one hour per eight and one half hour shift (roughly 12 percent of each shift) filling out various required forms. (These forms are exclusive of accident reports that officers have to complete, as discussed earlier.) By improving the process of recording, tallying, and reporting officers' attendance and activities, CHP could reduce the amount of time uniformed staff spend on administrative matters, thereby increasing patrol time. This is particularly important given that CHP currently provides negligible coverage of roadways during certain periods of the day when officers just beginning their shift are in briefings at the area office, while officers at the end of their shift are back completing paperwork. A 20 percent reduction in time spent annually on paperwork would amount to the equivalent of about 100 officers. In addition, changes to the process would also reduce workload for the nonuniformed clerical staff that currently perform the task of key-entering data from these forms into CHP's computer system.

Record-Keeping Should Be Streamlined. Accordingly, we recommend the enactment of legislation directing CHP to streamline its record-keeping procedures, including implementing the following:

The procurement of software for record-keeping purposes would involve one-time costs to CHP, which likely would be offset by a reduction in costs to key-enter data. While transcription services for officer reports would involve ongoing administrative costs, it would free up officer time for more road patrol service.

Under current law, all CHP uniformed road patrol officers are sworn law enforcement personnel, meaning that they possess "police powers" of, among other things, search, seizure, and arrest. Road patrol officers must have these powers to issue traffic citations to motorists, search a suspicious vehicle for illegal contraband, and arrest motorists for offenses such as driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs. In addition, however, these officers routinely perform various other service-related duties on their shift that do not require any special police powers. In fact, as Figure 6 displays, data from the department indicate that a significant amount of officer time (over 700,000 hours annually) is spent on activities such as directing traffic and completing paperwork for the storage of towed vehicles. Using the equivalent of over 400 CHP officers on these types of service calls, however, may not be the most cost-efficient use of sworn personnel—particularly considering the heavy workload they carry with accident investigations and enforcement responsibilities.

Road Patrol Duties Can Be Performed by Combination of Sworn and Nonsworn Staff. One alternative to more efficiently utilize road patrol resources would be to use nonsworn road patrol staff for certain activities. This would be similar to the community service officers that numerous law enforcement agencies employ throughout the state and country. For example, the Virginia State Police successfully uses full- and part-time civilian personnel to perform tasks such as directing traffic at crash sites, removing debris from the roadway, assisting the occupants of disabled vehicles, investigating abandoned vehicles, and coordinating the towing of vehicles. These "safety services patrollers" drive distinctively marked vehicles on the highway and are dispatched to nonenforcement calls such as vehicle breakdowns. If all of the safety services patrollers in an area are busy at the time with other calls, a Virginia road patrol officer (state trooper) handles the incident until one becomes available. By having civilian staff assigned to respond to service calls, state troopers' time is freed up so that they can conduct proactive enforcement patrols and manage more serious and complex situations.

Recommend Pilot Testing Use of Nonsworn Staff. In order to evaluate the workability of using nonsworn staff for certain road patrol duties in this state, we recommend the enactment of legislation that directs CHP to pilot test "safety services patrollers" in select areas for a period of time, such as two years, and to report to the Legislature on the pros and cons of implementing the project statewide.

If the pilot is successful, phased-in implementation of the program statewide would produce a net increase in the number of CHP staff (uniformed and nonuniformed) patrolling state roadways for about the same cost. This is because the average cost (salary and benefits) for a CHP officer is over one-fourth higher than that of a nonuniformed CHP position. Thus, for example, cost savings from hiring 400 safety service patrollers to replace the equivalent in vacant officer positions could be used to hire roughly 100 additional officers—thereby increasing total personnel coverage on state roadways.

Although CHP's authorized staffing level for officers and sergeants totals 6,900, only about 4,700 positions are designated for actual road patrol assignments. The other 2,200 officers and sergeants—based at CHP's Sacramento headquarters and in field divisions, area offices, communication centers, and inspection facilities throughout the state—perform various nonpatrol functions. In some cases, however, these uniformed personnel are assigned responsibilities that do not require police powers to carry out. Our review suggests that this is not an efficient use of peace officers. This is because these officers, who are compensated at higher levels than most nonuniformed staff due to their special status and skills, are occupying positions that do not allow them to use to the fullest capacity the expertise for which they are trained. To make more efficient use of CHP resources, we recommend that the Legislature enact legislation directing the department to study the feasibility of backfilling vacated nonpatrol uniformed positions with nonuniformed personnel. Cost savings generated from this action could be used to hire additional road patrol officers where justified by workload. For example, for every 100 vacant positions that are filled with nonuniformed staff rather than sworn personnel, the department could free up enough funds to hire an additional 25 road patrol officers for in-view patrol. Nonuniformed staff could be deployed in place of uniformed staff for activities such as:

This report has suggested a number of measures to address workload growth in CHP's road patrol program. Most of these changes give the Legislature the opportunity to increase in-view patrols with existing levels of funding for CHP. Specifically, by making various changes to CHP's current policies, processes, and procedures—as well as to the way it allocates and uses uniformed and nonuniformed staff—the department can free up substantial resources, potentially in the hundreds of uniformed officers, for proactive patrols, thereby enhancing CHP's road patrol service throughout the state.

| Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by Paul Steenhausen, and reviewed by Dana Curry. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814. |