High school is the culminating experience for students during their K-12 years. While many go on to college or technical school, high school represents the end of formal education for many students. High school also is a kind of “launching pad” into adult life. Students mature a great deal during these later teenage years, developing important work habits and attitudes as they become more independent.

This report examines how well high schools are helping all students learn and succeed in their postgraduation goals. Our report begins with a brief overview of current high school outcomes. In Chapter 2, we discuss state laws and policies that influence what students study during high school. Chapter 3 focuses on the issue of high school dropouts. Chapter 4 looks at high school from the perspective of high school graduates who plan on working or attending community college after graduation. Chapter 5 examines how admission policies of the state’s public four-year universities affect incentives for achievement in high school. Chapter 6 provides a summary of the report’s major recommendations.

Our recommendations offer the Legislature several ways to improve high schools. Alone, these changes will not address all of the problems in high schools. Many critical factors are outside of the state’s control. We think, however, our recommendations provide a strategic “road map” for how the state can contribute to improving high schools.

Chapter 1

In 2002-03, 1.8 million students enrolled in grades 9 through 12-the typical high school grades. Most students attend a traditional high school, one that contains grades 9 through 12. In 2002-03, 855 traditional high schools enrolled more than 85 percent of all high school students in the state, serving an average of about 1,800 students per school. While California’s high school students are an incredibly diverse mix of individuals, they can be grouped into three basic populations: students who drop out before graduating, students who graduate having passed the courses needed to establish eligibility for admission to the state’s four-year universities, and students who graduate without qualifying for a public university in California. Our report uses these three groups to better understand the problems high schools face and identify potential approaches to addressing them.

High Schools Address a Wide Range of Achievement

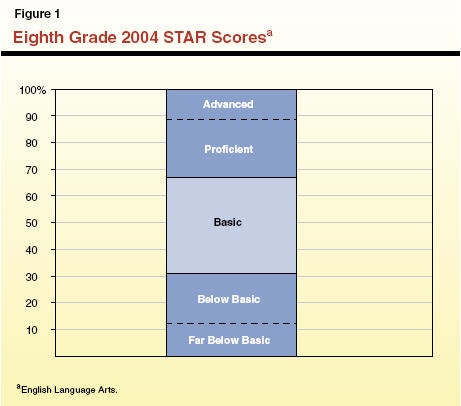

Students begin high school with very different levels of achievement. Figure 1 (see next page) displays the percentage of eighth grade students scoring in the five proficiency levels on the Standardized Testing and Reporting (STAR) English Language Arts test. About one-third of students score in the top two levels-proficient and advanced. About the same proportion scores in the basic category and in the bottom two levels combined-below basic and far below basic. Since the state’s goal is for all students to score in the proficient or advanced levels, Figure 1 shows that about two-thirds of eighth grade students are failing to meet this goal.

It is important to understand the significance of these data. Since 12.5 percent of high school graduates are eligible for admission into the University of California (UC), the 11 percent of students scoring in the advanced level are scoring at levels roughly consistent with UC’s admission standards. At the other end of the performance scale, about 12 percent-roughly 60,000 students-scored far below basic. Scores at this level are equivalent to randomly guessing at the answers to test questions. The difference between the advanced and far below basic levels, therefore, represents a major achievement gap. (For the remainder of the report, we simplify the STAR testing data by consolidating the top two STAR performance levels into “above basic” and the bottom two levels into “below basic.”)

The STAR data also reveal that most high schools must wrestle with the problem of developing curricula that are appropriate for a wide range of student achievement. In the next section, we briefly review what happens to eighth grade students during the high school years and after graduation.

Achievement During High School

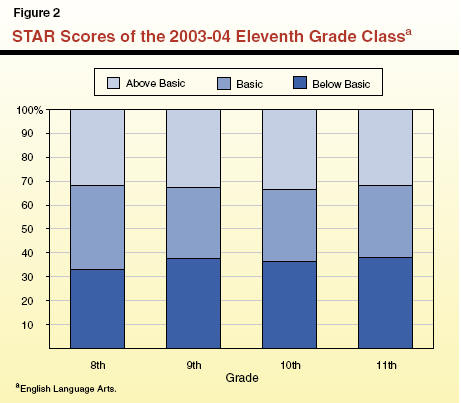

The real test for high schools is not where students start in ninth grade but the improvement made while in high school. One way of measuring this “value added” is by examining the progress of the same group of students over time. Figure 2 shows the STAR scores in grades 8 through 11 for the cohort of students who were in eleventh grade in 2003‑04 (that is, the eighth grade scores are from 2000‑01, the ninth grade scores are from 2001‑02, and so on). As the figure shows, there is very little change over time in the proportion of students scoring in the three levels.

In fact, this figure may overstate the achievement of this cohort of students because it does not account for students who dropped out during high school. Since low-achieving students are more likely to drop out of school, we would expect the remaining students to be higher performing. They are not. Therefore, the data suggest that, relative to state standards, student achievement may be falling during high school.

Another way to evaluate the success of high schools is to look at measures like graduation rates and college attendance rates of recent graduates. By combining data on these two measures, it becomes clear there are three basic outcomes for high school students: failing to graduate (dropouts), graduating and qualifying for admission to UC or the California State University (CSU) (which we will call the “university track”), and graduating without qualifying for a four-year university (which we will call the “general track”).

We have focused this report around these three groups for several reasons. Graduation and continuing on to college represent widely accepted successes for high schools. By focusing on student outcomes, we can more readily identify issues that create barriers to success. In addition, students in the three groups generally face very different problems in high school. Understanding these problems provides a picture of the breadth of challenges high schools face. Finally, all high school students are in one of the groups.

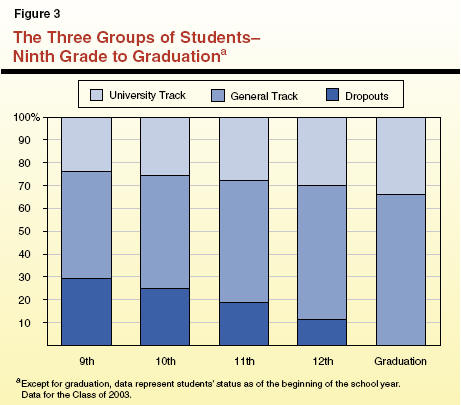

By combining several sources of data, we can track these three groups over the four years of high school. Figure 3 (see next page) displays our estimate of the composition of each high school grade. In ninth grade, students who will eventually drop out represent just under 30 percent of the students in the class. As this group leaves school over the four years, it represents a declining proportion of the class. Since this group does not graduate with the class, it disappears entirely from the “graduation” bar in the figure.

The figure shows that, upon graduation, the university track accounts for one-third of students who remain in school. As a proportion of entering ninth graders, however, the university track comprises only one-fourth of all students. As students in the class drop out of school, this group represents a larger proportion of the remaining students.

The general track contains the largest proportion of students. In ninth grade, almost one-half-47 percent-of all students are included in the general track. As with the university track, this group stays in school and represents an increasing proportion of remaining students over the years. By graduation, the general track accounts for two-thirds of students.

College Attendance by Students in the Three Tracks

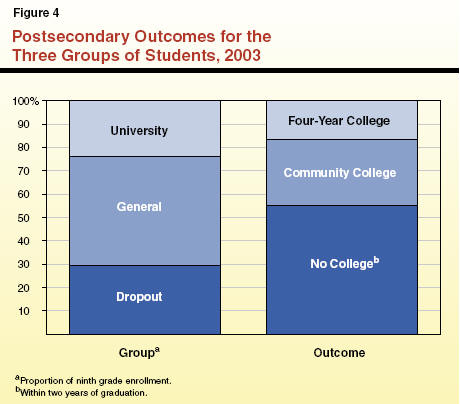

Figure 4 conveys a sense of the postsecondary education outcomes for high school students. The left-hand column illustrates the proportion of ninth graders in each of our three groups (the university and general tracks and dropouts). The right-hand column displays the proportion of students who enroll in four-year universities (UC, CSU, and private colleges and universities) and two-year colleges (the California Community Colleges [CCC]) after graduation. As the figure indicates, 45 percent of students attend college after high school-17 percent enroll in four-year institutions and 28 percent attend community colleges. The other 55 percent of students do not attend college in the first two years after graduation-although they may return later in their adult lives.

Figure 4 also provides a sense of what happens to students in the three groups immediately after high school. Assuming all students in the university track go to college after graduation, about 70 percent of this group attends four-year colleges and about 30 percent attends CCC or attend college in another state. Figure 4 also suggests that a significant proportion-about 40 percent-of the general track enrolls in CCC. The remainder of the general track and dropouts do not enroll in college.

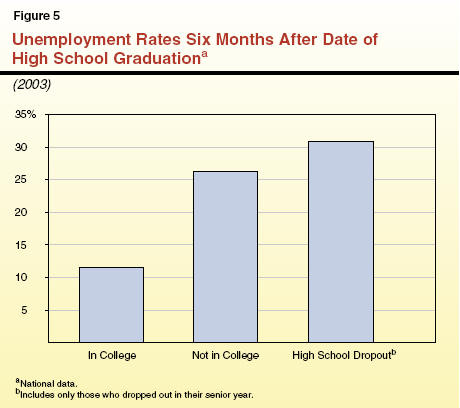

Unemployment Rates of Students in the Three Groups

Most of the 55 percent of students who do not attend college after graduation enter the labor force. Unemployment data suggest a difficult transition to the labor market for many of these students. Figure 5 displays national data on the unemployment rates of students six months after they graduated (or would have graduated if they had not dropped out of school). A total of 19 percent of recent graduates were unemployed, which is defined as actively seeking work, but unable to find a job. For graduates enrolled in college, 12 percent were unemployed. For graduates who were not in college and for students who dropped out during their senior year, unemployment rates were significantly higher-26 percent and 31 percent respectively. These figures do not include “discouraged workers,” who are not employed but have given up looking for a job.

Adult unemployment rates also decline as education increases. California’s unemployment rates reflect this trend. For example, in April 2004, 8.3 percent of adults with a high school diploma reported being unemployed. This compares to 5.3 percent for adults with a two-year CCC degree and 4.3 percent for adults with a four-year college diploma.

The data suggest that students who are not preparing for entrance into college experience greater problems in the labor market. Students who enter the full-time labor force have a harder time finding jobs after their high school years and experience higher unemployment rates as adults.

High schools in California face a significant challenge in helping all students experience success. Data provide mixed evidence on whether the state’s schools meet this challenge. Relative levels of student achievement do not seem to improve from eighth to eleventh grade. Students continue to learn, but high schools do not appear to make progress in accelerating the achievement of lower-performing students. On the contrary, the data suggest that student achievement is not keeping up with the pace dictated by state performance standards.

Other outcome data also indicate a mixed picture. Almost 30 percent of students who start high school do not graduate. Dropouts and high school graduates that do not continue on to college also experience a rough transition to the labor force. As we discuss later in this report, even our most successful students-those who attend college immediately after graduation-are not fully prepared for college-level work.

Later in this report, we examine the experience of these three groups in more detail. In the next chapter, we explore the state’s policies that influence the structure of high schools.

Chapter 2

State law affects the design and operation of high schools in many ways, large and small. Remedial instruction funding, for instance, provides supplemental support for classes that take place outside of the school day. Truancy mandates require schools to follow specific procedures as part of local attendance programs. Funding for alternative programs, such as continuation or community day schools, influence the settings districts employ for educating certain groups of students.

In this section, we review five key state policies that shape the course offerings of high schools and measure the amount students learn in school. These laws also define the skills students need to graduate and qualify for admission into the state’s four-year universities. Together, we believe these five policies exert the most significant influence over the operation of high schools.

These policies can be grouped into two categories. The first group includes state laws or programs that structure student choices over the courses they take in high school. This includes high school graduation and university admission course requirements. Also in this group are state-funded Regional Occupational Centers and Programs (ROC/Ps), which provide vocational education courses to students beginning in their junior year. Graduation and university course requirements affect student demand for certain courses while ROC/Ps increase the supply of vocational courses available to students.

The second group consists of two state testing programs, which also exert great influence over high schools. The STAR establishes performance standards for core academic programs, providing feedback about whether students learn the material in these courses. The California High School Exit Examination (CAHSEE) assesses whether students have attained a level of achievement in mathematics and English the state has deemed necessary for all high school graduates.

The two sets of state course requirements play a central role in what students study in high school. Figure 6 displays the specific requirements for high school graduation and for admission into a public four-year university in California. Enacted in 1983, the graduation requirements help ensure all high school students take a minimum number of academic courses prior to graduation. As the figure shows, students must take over a dozen year-long courses to meet this state requirement.

|

Figure 6 High School Course Requirements for Graduation and University Admissions |

||

|

(Number of Annual Courses) |

||

|

|

Graduation |

UC/CSU

|

|

English |

3.0 |

4.0 |

|

Mathematics |

2.0 |

3.0 |

|

Science |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

History/social science |

3.0 |

2.0 |

|

Foreign language |

1.0a |

2.0 |

|

Art |

1.0a |

1.0 |

|

Physical education |

1.0 |

— |

|

Other |

0.5 |

1.0 |

|

Totals |

12.5 |

15.0 |

|

|

||

|

a State law calls for one of either art or foreign language courses. |

||

The UC and CSU establish a slightly different set of course requirements that students must take as a prerequisite for admission into the four-year university systems. These requirements are known as the “A through G” requirements. The admissions requirement calls for students to take a minimum of 15 year-long courses during high school. In some subjects, students must take specific courses-such as Algebra II in mathematics-to meet the university requirements.

Meeting both the graduation and A through G requirements requires students to take 17 specific courses. (In most subject areas, the A through G requirements call for more courses. In history and physical education, however, the graduation requirements are higher.) In addition, both UC and CSU encourage students to continue taking high-level courses in their senior year. Students who follow this advice by taking courses in all four core areas would use 20 of the 24 high school courses typically available during four years to meet state course requirements.

All high school courses in the subject areas identified for university admissions do not necessarily qualify as meeting the A through G requirements. The UC must specifically approve each high school course that counts toward these requirements. In contrast, districts determine which courses satisfy the graduation requirements, with two exceptions. State law requires one science course to be a laboratory science and students must take algebra as one mathematics course.

The A through G requirements also are important because they create a roadmap-a sequence of courses that, when completed, make a student eligible to apply for admission to a four-year public university in California. By developing the A through G requirements, the universities have helped students and parents understand how to use high school to prepare for UC or CSU.

Vocational Options Through ROC/Ps

Another way the state affects course offerings is through the establishment and support of ROC/Ps. As the name suggests, these agencies provide regional support for vocational education, primarily through county offices of education. In urban counties, ROC/Ps are sometimes administered by consortia of school districts (known as “joint powers agencies”) or very large districts. The 2004‑05 Budget Act includes almost $400 million for the support of ROC/Ps.

The ROC/Ps were established in the 1960s to take advantage of economies of scale that were unavailable to most high school vocational programs. Vocational classes often require specialized instructors and equipment. By attracting students from a larger region, ROC/Ps are able to generate the enrollment in vocational classes needed to finance the higher cost of these programs.

Figure 7 displays the statutory missions of ROC/Ps. Most importantly, state law requires ROC/Ps to help students gain entrance into entry-level occupations. As these jobs typically do not require extensive training, the course structure of ROC/Ps focuses on individual classes. Some ROC/Ps also offer course sequences that help students achieve higher-level job skills or gain entry into advanced community college courses.

|

Figure 7 The Mission of ROC/Ps |

|

|

|

|

|

� |

Allow students to learn entry-level occupations. |

|

� |

Ensure skills are in demand by local employers. |

|

� |

Provide guidance and counseling on vocational matters. |

|

� |

Give priority to students 16 to 18 years old. |

State law also places a priority for ROC/Ps to serve high school students age 16 through 18. Because of this priority, ROC/P classes are targeted mainly at juniors and seniors. State law allows ROC/Ps to serve adults, as well. In 2003‑04, about two-thirds of all ROC/P enrollments were high school students. The proportion of high school students served by individual ROC/Ps, however, varies greatly. While most programs serve only a small percentage of adults, a few programs serve primarily adults.

The High School Exit Examination

In 1999, the Legislature enacted the CAHSEE. This test, which students must pass to graduate from high school, measures student achievement in mathematics and English. Students take the test for the first time in tenth grade. Students who fail either portion of the test may retest up to seven times during the subsequent two years. The test assesses student mastery of the state mathematics standards up to and including algebra and the tenth grade English Language Arts standards.

The class of 2006 is the first to be subject to the CAHSEE requirement. Students in this class took the test for the first time in spring 2004. Almost three-quarters passed each of the subject areas. About 60 percent of low-income students passed at least one of the two portions of the test on their first attempt. Passing rates of English learner (EL) students and special education students were significantly lower.

As discussed above, the Legislature enacted high school graduation course requirements to increase the number of academic courses taken by high school students. The CAHSEE represents another way of improving academic performance. Rather than specifying the number of courses students take, the CAHSEE establishes performance-based criteria for graduation. For instance, it requires that students demonstrate a specific level of mathematical competency in arithmetic and algebra.

As an accountability measure, the CAHSEE significantly affects students and schools. The CAHSEE has increased the academic focus of high school for many students. While high-performing students generally find the CAHSEE standards relatively easy to meet, the test has increased academic expectations for lower-performing students. As a result, more students are taking algebra than before the test requirement was enacted.

In addition, the CAHSEE creates new incentives for schools to boost student achievement. Scores from the CAHSEE are used as the accountability measure for high schools under the federal No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act. Because the law creates consequences for failing to meet performance targets, high schools are motivated to improve student performance on the test.

Finally, graduating from high school is very important for parents and students. Failing to pass the CAHSEE prevents a student (beginning in 2006) from graduating. As a result, high schools are under significant pressure to help students pass the test. In response, schools have developed remedial courses to help students master the skills needed to pass the test.

State Content Standards and the STAR Tests

In 1997, the Legislature enacted the STAR program. As part of that effort, the Legislature required the development of course content standards that would guide the development of the STAR tests. Beginning in 2000, STAR began to include tests aligned with the state’s content standards. By 2002, STAR included tests for standards-aligned courses in English, history, science, and mathematics in grades 9 through 11 (see Figure 8).

|

Figure 8 High School Courses Assessed by the STAR Program |

|

|

|

|

|

English |

Grades 9 through 11. |

|

Mathematics |

General mathematics, Algebra I, geometry, and Algebra II. Students taking mathematics courses above the level of Algebra II take a “summative” test covering both algebra courses and geometry. |

|

Science |

Earth science, biology, chemistry, and physics. |

|

History/social sciences |

Grades 10 and 11. |

Students generally take a STAR test only after they complete a course that covers the state standards. The English and history tests reflect the grade-level orientation of the state standards in these subjects. The tests in mathematics and science, however, align with specific content areas within the subjects. Students take a “summative” test when they complete mathematics courses beyond the Algebra II level.

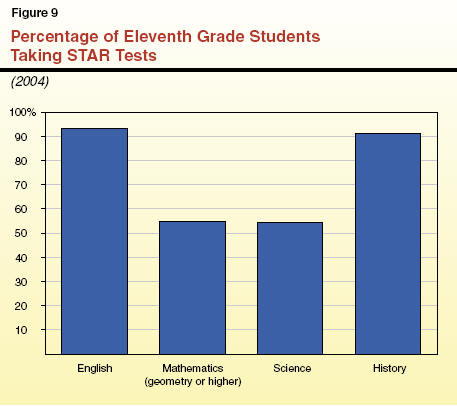

The 2002‑03 STAR results reveal that almost all students take the high school English and history tests. This is consistent with the state graduation requirements of three years of English and history courses. A much smaller proportion of students take more advanced mathematics and science classes and the related STAR tests. These are typically students planning to attend college after graduation.

Figure 9 illustrates this situation. The figure displays the proportion of eleventh grade students taking STAR tests in the four content areas in 2004. Over 90 percent of students took the history and English tests. By comparison, only about 55 percent of eleventh graders took an advanced mathematics test (geometry or higher) or one of the four STAR science courses.

Impact of STAR Results on Educators. The STAR results for grades 9 through 11 have mixed performance incentives for educators. On the one hand, since STAR results cannot be used for high school accountability scores under NCLB, few direct consequences result from low STAR scores for most schools and districts. On the other hand, the STAR scores do determine school rankings under the state’s accountability system. Since these rankings are quite visible to the public, local educators want students to do well on the test.

Impact of STAR Results on Students. For most high school students, however, the STAR results have little impact because there are no negative consequences for doing poorly on the test. Test scores are sent to parents for information purposes. Schools, however, may not include STAR scores on student transcripts without permission. As a result, UC and CSU generally do not have access to STAR scores as part of the admissions process.

The state has tried to create incentives for students to do well on STAR. For instance, state law requires districts to use STAR scores to evaluate whether students are ready for promotion from eighth grade to ninth grade. The state also created a merit college scholarship program that was based on STAR scores. (The program was eliminated as part of budget cuts after only two years.) It is not clear whether either program altered student incentives significantly. Unless students are accountable for their performance on STAR, the test will not create incentives for students to work harder and learn more in school.

The state plays a major role in determining what students study each day and the way the state evaluates performance in those classes. Graduation and university course requirements dictate most of the courses students take during high school. University admissions requirements are also important because they create a pathway to a postsecondary goal of many students-attending UC or CSU. State-funded ROC/Ps create a source of occupational-specific training that confer technical skills to students and help them find better jobs after graduation.

The CAHSEE represents a different way to increase the skills of students. By clearly identifying what all students should know to graduate from high school, the test has two potential advantages over the course requirements. First, the test places more responsibility on students for learning the necessary content. So long as the test content represents a realistic challenge for all students, the CAHSEE encourages lower-performing students to work harder to learn the content assessed by the test. Second, the test creates a statewide benchmark for minimum student achievement. Graduation course requirements can be “watered down” at the local level by giving students credit for passing low-level courses. Because the CAHSEE is performance based, the test helps the state maintain a level of rigor to graduation requirements.

Like the CAHSEE, the high school STAR tests reinforce the state’s expectations for academic courses. The STAR, however, has a greater focus on academic courses taken by students who want to go to college. Unlike the CAHSEE, students currently have little stake in performing well on the STAR tests. As a result, the state may be missing an opportunity to use STAR to increase student incentives to work hard in high school.

Using state tests to hold students accountable also creates new obligations for the state. In the case of the exit examination, the class of 2006 must pass the CAHSEE to graduate. As spring 2006 draws near, concern over the passing rates-particularly for special education and EL students-is growing. Previous court cases in other states have required states to show that students who failed a high school graduation test had a reasonable opportunity to learn the material on the test. Otherwise, courts have not allowed states to deny diplomas to students based on the outcome of the examinations. As a result, using the CAHSEE to define what high school graduates need to know also makes the state accountable for ensuring that students receive the instruction they need to learn the material.

In the next three chapters, we explore more thoroughly the issues related to the three groups-dropouts, the general track, and the university track. Using available data and research, we identify problems students in these three groups encounter while in high school and discuss approaches for addressing them. Each chapter ends with our recommendations for legislative action.

Chapter 3

As noted earlier, about 30 percent of California’s entering high school students fail to graduate. In this section, we examine why students drop out and identify promising approaches to reducing dropout rates. Research offers no easy solutions for reducing dropout rates. Nevertheless, the state can take several important steps to focus attention on districts with high dropout rates and support local efforts to reduce dropouts.

It is important to recognize that our estimate of the dropout rate is significantly higher than the rate calculated by the State Department of Education (SDE). For 2002‑03, for instance, SDE’s dropout rate was 12.6 percent. There are several differences between our methodology and SDE’s dropout rate calculation. Most important, the two methodologies count students differently. The SDE calculation is based on the number of high school dropouts reported by districts. Our estimate tracks the number of students reported as enrolled in each grade and the number graduating each year. Since SDE does not require districts to explain why enrollment declines are greater than the reported dropouts, data do not exist to fully understand why reported dropouts are so much lower than suggested by enrollment data. One major reason for the difference, however, is that SDE’s data capture dropouts only through the fall of twelfth grade. As a consequence, the department’s estimate does not reflect students who drop out in the spring semester of their senior year or who complete twelfth grade but fail to graduate. Our measure captures both groups-we estimate this difference accounts for about 9 percentage points of the difference between our estimate and the SDE rate.

We think our methodology results in an estimate that is closer to the actual dropout rate. By counting the actual number of students enrolled in California schools and the number graduating from high school each year, our data reflect the actual decline in participation over the four years in high school. While our estimate may overstate dropouts somewhat-students who move out of the state are included in our dropout rate-we think our methodology develops a much more accurate rate than SDE’s. In the discussion below, therefore, we use our methodology as the best estimate of dropouts. Until the state develops a data system that collects reliable dropout statistics, data issues will hamper California’s ability to assess the size and scope of its dropout problem.

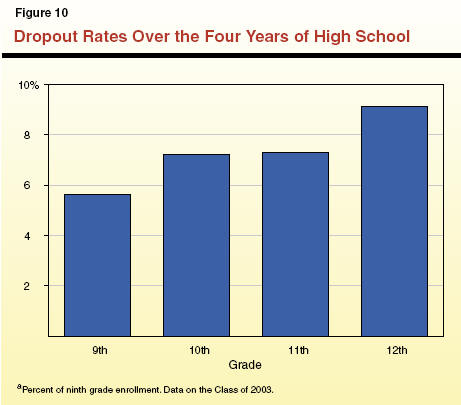

Students drop out at an increasing rate over the four years of high school. Figure 10 shows our estimate of the percent of the 1999‑00 ninth grade class that dropped out each year. For example, 5.6 percent of students dropped out of school during ninth grade, while 9.1 percent of students dropped out during twelfth grade (or did not graduate. Cumulatively, this cohort of students lost about 30 percent of the original class over the four years.

The dropout problem is not uniform across the state. Large urban school districts have higher-sometimes significantly higher-dropout rates than the state average. For example, we estimate dropout rates for the same 1999‑00 ninth grade class for Oakland Unified and Los Angeles Unified School Districts at 50 percent and 55 percent, respectively. San Diego Unified and Long Beach Unified School Districts did considerably better-with dropout rates of about 35 percent-but still exceeded the statewide average.

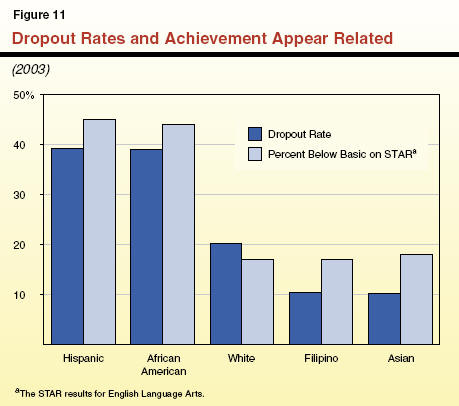

Dropout rates appear highly related to student achievement. Figure 11 displays dropout rates and ninth grade STAR scores for the five largest racial/ethnic groups in California. As the figure shows, dropout rates and the proportion of ninth grade students scoring below basic on STAR for each group is roughly similar. African American and Hispanic students were more likely to score below basic on STAR and were significantly more likely to drop out than most other racial and ethnic groups. While white, Filipino, and Asian students are fared similarly on STAR, white students were twice as likely to drop out as Filipino or Asian students.

Finally, the dropout rate in California has slowly declined over the last five years. We estimate the dropout rate in 1997‑98 at about 33 percent. By 2002‑03, it fell to about 29 percent. This decline suggests that about 20,000 more students graduated in 2002‑03 than if the 1997‑98 rates had applied. In addition, our estimates suggest all the major racial and ethnic groups experienced higher graduation rates over this time period.

A 2004 report by the Urban Institute shows California’s dropout rate was below the national average. This, along with the steady reduction in dropouts over the last five years, provides a hopeful sign that local schools are more effectively addressing the needs of students at risk of dropping out. In the next section, we summarize existing research on the source of the dropout problem.

Dropouts-A Consequence of Disengagement

The National Research Council (NRC) issued a report in 2004 on the problems of urban schools, including low achievement and school dropouts. The report, which synthesizes available research on these topics, describes dropping out as “the ultimate” in student disengagement. “Dropping out of high school is for many students the last step in a long process through which students become disengaged from school.”

Engagement is a mix of attributes that result in a dedication to learning and a belief in the value of school. Figure 12 displays the major attributes of an engaged student. Another way to describe an engaged student is “self-motivated.” Ideally, engaged students are absorbed in the learning process because they find the material interesting. When disengagement becomes advanced, however, frustration and alienation can result in increased absenteeism and behavior problems and, eventually, dropping out.

|

Figure 12 Attributes of Engaged Students |

|||

|

|

|||

|

� |

Enthusiasm |

� |

Active participation |

|

� |

Interest |

� |

Completing work |

|

� |

Pride in success |

� |

Seeking assistance when needed |

|

� |

Social involvement |

� |

Taking challenging classes |

The NRC report finds that the seeds of disengagement usually are planted long before high school. Years of poor performance in elementary and middle schools can lead students to conclude that “school is not for them.” This leads to low expectations for their own success in school and, consequently, low effort-a vicious circle of sorts that results in declining achievement.

Research also suggests that student educational and occupational aspirations are good predictors of dropping out. Enthusiasm for school can wane when students do not see a connection between their course of study and their post-high school goals. This may occur because there is no connection or because students are ill-informed about the steps needed to reach their goals.

The problem of disengagement in high school is not restricted to dropouts. The NRC report cites studies finding that 40 percent to 60 percent of all high school students studied were “chronically” disengaged. This finding is reinforced by several surveys of high school students we reviewed. For instance, a survey of students in Colorado found that 65 percent of students reported they were bored in school at least half of the time. The NRC report concludes that, in most high schools, unless students “come with their own intrinsic motivation to learn (or at least to get good grades), they are likely to feel alienated from their teachers and coursework.”

Key Elements of a Dropout Strategy

The NRC report finds no easy solutions to preventing high school dropouts. Evaluations of programs implementing research-based “best practices” show, at best, mixed success. The report points to five key features of programs that successfully reduced dropout rates. These elements are displayed in Figure 13 and discussed in greater detail below.

|

Figure 13 Key Elements for Addressing High School Dropouts |

|

|

|

|

|

An academic push |

A focus on teaching and learning that “does whatever it takes” to increase the academic skills of students. |

|

Early attention to low performance |

Special programs in middle school for “at-risk” students show

promise in |

|

More personalized schools |

More personal, supportive schools create an environment which encourages lower-performing students to engage in school. |

|

A greater range of options |

Giving students and parents greater control over their program make school more aligned with student goals. |

|

Parental involvement |

Parents must be partners with schools in keeping students on track. |

An Academic Push. The critical feature of any school is an educational program that is committed to doing whatever it takes to help all students achieve. The NRC report defines this as giving all students what they need to learn, holding them accountable, and providing extra assistance when needed. This focus on success sometimes requires changing teachers’ instructional approaches to educating low-achieving students. Holding students accountable includes consequences for failing to complete required work and strong school attendance and truancy programs.

Without this academic push, it is unlikely the other four components will have a significant impact on dropout rates. Students become less likely to drop out when they begin to have success in school. In this context, the other promising components can be viewed as supporting elements-components that are effective only to the extent they complement an effective instructional program.

Early Attention to Low Performance. Research suggests that disadvantaged low-achieving ninth graders typically do not significantly raise their skill levels by twelfth grade. The NRC report cites one study showing that only 15 percent of students identified as weak readers in eighth grade had progressed to an intermediate or advanced level by twelfth grade. The report concludes that, by eighth grade, most low-achieving students had lost their belief that they could make significant progress in school.

Studies also show that student motivation declines as students move through elementary school to middle and high schools. Thus, it makes sense to address the achievement problem before high school, when students are more engaged and when academic deficits are smaller. Initial research on several middle school intervention programs suggests the approach holds promise. Successful programs established alternative schools for at-risk middle grade students, often with smaller class sizes and additional counseling, to accelerate the progress of at-risk students. By comparison, programs that supplemented existing middle school programs with various services showed almost no impact.

More Personalized Schools. Middle and high schools that successfully reduce dropout rates adopt a more personal approach to educating students than the typical high school. The attributes of this approach include:

A school climate that promotes the belief that all students can learn and feel socially connected with the school.

Smaller schools, where students have more personal interactions with teachers and other adults who can help resolve family or personal problems.

High, but achievable, expectations of student academic achievement.

Research suggests these attributes may be necessary, but not sufficient, elements of successful dropout programs. Several studies we reviewed showed schools successfully implementing this personalized approach while having no impact on dropout rates. These findings reinforce our earlier point about the central importance of an academic push.

A Greater Range of Options. The NRC identifies choices as a critical element in helping students “see some value in the high school curriculum.” Choice involves a range of curricular options-including both academic and vocational paths. The report concludes that “Because few urban schools are closely connected . . . to the educational and career opportunities potentially available to students, many students fail to see how working hard in school will enable them to attain the . . . goals to which they aspire.” By connecting students’ high school programs with their postgraduation goals, schools can increase motivation to learn.

Program options for students are important for a second reason. Choices provide students with a way to be involved in their education. With adult freedom and responsibility on the horizon, high school students feel they should have a voice over their education. By giving students a greater range of curricular options, schools can give students (and their parents) more control-and more responsibility-over what they study in school.

Parental Involvement. While almost all school improvement programs-including programs to reduce dropout rates-stress the importance of parental involvement, we were unable to find evaluations identifying the types of involvement that make a difference with at-risk high school students. Literature on parental involvement at the secondary level, however, suggests that parents play a different role in supporting students than when their children were younger. Unlike elementary students, high school students often do not want parents involved in their day-to-day affairs. As a result, parents must “steer” their children through the challenges, keeping them on task, arranging for extra support when needed, and knowing who their child’s friends are.

The parent’s role is very similar to the list of attributes that describe the “personalized” school. This is no accident. All students need encouragement, support, and, sometimes, externally imposed discipline to keep them on track in school. The research is clear that all students are more successful when they get the same messages from school and home. The NRC report finds that parental involvement declines as children get older and that, by some measures, low-income parents are less involved in their children’s education. As a result, schools need to develop ways to engage parents as partners in this endeavor if they are going to significantly reduce dropout rates.

Implementation Is a Critical Factor. Many districts in California already implement programs that include the elements discussed in this section. Programs like Advancement Via Individual Determination and Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness for Undergraduate Programs are designed to boost the achievement of elementary and middle grade students and prepare them for postsecondary education. A few districts also are creating special programs for eighth and ninth graders who achieve at very low levels to improve their skills prior to taking high school courses. Similarly, districts are developing smaller, more personal high schools that provide greater curricular options to students.

As we cautioned above, however, research shows there is no simple formula for success in reducing dropout rates. An evaluation of reform efforts in ten high schools in Boston, Massachusetts, for instance, showed that, despite implementing the key elements discussed above, only two schools produced higher student achievement among low-income, low-achieving students. The evaluation concluded that the successful schools used the reforms to change the culture of high school and increase student engagement. These changes, along with a “laser-like focus on teaching and learning” resulted in higher achievement.

State Actions to Reduce Dropout Rates

What can the state do at a policy level to reduce dropout rates? Most of the effective elements are outside state control. For instance, the state cannot require all high schools to become “more personalized.” Similarly, the state cannot create a desire within school officials to engage parents in meaningful ways. There are, however, several ways the state can support schools and districts in addressing the problem of dropouts. Figure 14 displays a summary of our recommendations, which we discuss in detail below.

|

Figure 14 State-Level Actions To Reduce Dropout Rates |

|

|

|

|

|

Accountability |

Increase the focus of federal accountability programs on lower-performing students. |

|

Flexibility |

Give

schools more flexibility over |

|

Options |

Assist schools in providing more |

|

Early attention to low performance |

Evaluate the effectiveness of remedial programs and social promotion policies. |

|

Data |

Support the student-level database |

Strengthen Accountability for Low Performance and Dropouts. High dropout rates would seem to be an indicator of an accountability problem. That is, local pressure to reduce the number of dropouts is not sufficiently strong to spur concerted action by educators and school board members. There are, in fact, some disincentives to address the dropout problem. When low-achieving students leave, for instance, average school test scores increase. This gives the appearance that the school is improving, and it allows the school to focus on the education needs of the more motivated students that remain. In addition, when students marked as “problems” or “trouble-makers” drop out, they relieve educators of administrative headaches. As a result, inattention to the needs of these types of students can actually make schools appear more successful.

State and federal accountability programs attempt to address these negative local incentives by including graduation rates as a performance measure. The state’s implementation of these programs, however, results in only weak district incentives to improve dropout rates. In addition, implementation decisions by the State Board of Education (SBE) created mixed messages about the importance of raising the achievement of low-performing students, who are at greatest risk of dropping out. To correct these problems, we recommend the Legislature direct SBE to make two changes to the state plan for implementing the federal accountability programs under NCLB. We discuss these changes below.

Refocus NCLB on Helping Low-Performing Students

We recommend the Legislature require SBE to reset NCLB performance levels in order to encourage school districts to focus on the needs of students who are at risk of dropping out of school.

The federal NCLB requires all schools and districts to ensure that a minimum percentage of students achieve at or above a proficient level of performance. This minimum percentage increases each year until, in the year 2014, NCLB decrees that all students must be at the proficient level. Districts and schools that fail to meet these targets two years in a row enter Program Improvement, where they are subject to a variety of sanctions.

Under NCLB, states cannot change these elements of the accountability system. Federal law, however, leaves to states one key decision that significantly shapes the impact of NCLB accountability on schools and districts-the definition of the proficient level of performance. In general, where states set this performance “bar” has a major influence on the incentives created to encourage schools to focus on the needs of low-performing students-those who are most likely to drop out of school.

In 2003, SBE established a high bar for NCLB accountability. Specifically, it set the NCLB achievement targets for grades 2 through 8 at the STAR proficient level. Because the state uses the CAHSEE as its NCLB indicator for high school, it set a CAHSEE target that was equivalent to the STAR proficient level. This high school NCLB target is significantly higher than the score needed to pass the CAHSEE. Only about one third of students currently achieve at the STAR proficient level-thus, the performance bar is set roughly equal to the achievement level of the state’s university track students.

A high NCLB standard has the practical effect of reducing a school’s incentives to attend to the educational needs of students who are likely to drop out. Under NCLB, schools receive credit for helping students improve their performance only when they score at the proficient level. This design encourages schools to focus on the needs of students who scored just below the bar in the previous year, as they are the students who most likely could achieve proficiency the next time around with some improvement. By setting the bar at the STAR proficient level, therefore, the board focused schools on giving extra help to students who previously scored in the STAR basic level.

We believe that the NCLB performance standard should be reset to encourage schools to focus on the needs of students who are at risk of dropping out. For example, using the passing score of the CAHSEE as the performance bar would have several positive effects. First, it would align minimum student expectations for graduation with the federal accountability program. With the existing high NCLB standard, high schools face conflicting incentives. They are under great pressure to help students pass the CAHSEE so they can graduate from high school. Under NCLB, however, high schools receive no credit for helping more students pass the test-they only get NCLB credit when they help students earn the higher NCLB score on the CAHSEE. Given limited resources, which group of students should schools emphasize-students who need help to pass the CAHSEE or students who, with help, can earn the NCLB score on the CAHSEE? By aligning federal accountability standards with the CAHSEE passing score, the Legislature would relieve high schools from this dilemma.

Second, resetting the NCLB standard also would increase incentives for elementary and middle schools to provide extra help to students who are at risk of dropping out. Providing early help to low-performing students holds promise for reducing dropout rates. The existing high bar, however, encourages schools to focus on the needs of students scoring in the STAR basic level, who are less likely to drop out in high school. By lowering the NCLB standard, the state would encourage schools to increase efforts to raise the achievement of low-performing students before their academic deficiencies reach a critical stage.

Third, changing the bar would help schools and districts successfully adjust to NCLB accountability. Where the bar is set establishes the size of the student population that needs to improve. Under the current definition, two-thirds of students are achieving at levels below the performance standard. By resetting the bar, the Legislature would reduce the size of the population that is “underperforming” and send a signal that the state’s goal under NCLB is raising achievement levels of the lowest-performing students. For schools and districts with few low-performing students, this new focus may help them succeed under NCLB accountability. (It remains a question whether schools and districts with larger proportions of low-performing students can succeed under NCLB even with lower performance expectations.)

For the above reasons, the existing policy undercuts incentives to address the needs of students who are likely to drop out of school. To address this problem, we recommend the Legislature enact legislation requiring SBE to set NCLB performance standards at a level consistent with passing the CAHSEE. This would align the state and federal accountability systems, and send a stronger message to schools and districts about the importance of addressing the needs of students at risk of dropping out.

Our recommendation would establish accountability standards similar to those used in other states. The accountability features under the federal act were modeled after Texas’ accountability program from the 1980s and 1990s. Texas began with modest performance expectations for students. As schools helped all students achieve these performance goals, however, the state raised its standard. Over time, the state was able to improve minimum student achievement levels. Currently, Texas maintains a relatively low performance bar under the federal accountability program-more than 80 percent of students in Texas meet the state’s definition of proficient under NCLB.

Strengthen Accountability for Dropouts as Data Improve

We recommend the Legislature require SDE to collect student-level data on graduation rates beginning in 2007 as a means of including dropout data on the state’s Academic Performance Index (API).

Both the state and federal accountability programs attempt to increase local responsibility for dropouts. State law calls for including dropout rates in the API. Federal law requires states to hold districts accountable for graduation rates. To date, dropout rates have not been included in the API due to concerns about the accuracy of the dropout data.

Graduation rates have been included as part of the federal accountability system. The SBE approved a two-part test for determining whether schools and districts make adequate progress on increasing graduation rates (or reducing dropout rates). Specifically, schools or districts can show adequate progress by:

Maintaining a graduation rate of at least 82.8 percent. According to SDE, 20 percent of high schools reported a lower graduation rate in 2003. Schools and districts graduating a lower proportion of students can still demonstrate adequate progress by meeting the second test.

Increasing the graduation rate by 0.1 percent over the previous year’s rate (or by 0.2 percent over the previous two years).

These accountability provisions create fairly weak incentives for schools and districts to focus on reducing the level of dropouts. In 2004, for instance, SDE reports that about 10 percent of all high schools did not demonstrate adequate progress based on these criteria-and only 3 percent failed to make adequate progress due solely to the graduation rate requirement.

New Data System Offers Better Graduation Data. The current graduation and dropout data are problematic, and it is difficult to base strong accountability requirements when the data are so weak. In two years, however, the state will have much better data to calculate dropout and graduation rates. This is because of the implementation of the California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System (CALPADS). The CALPADS will store longitudinal state assessment data on all K-12 students. To collect data on students as they move to different districts over time, the state assigns each student a unique identifier. Beginning in 2006, the student identifier will be included on all students’ state test results.

We think the state should begin using the longitudinal testing data to calculate graduation and dropout rates for high schools and districts as soon as possible. Based on SDE’s existing methodology, the state would have to wait until 2010 to determine these rates using the CALPADS data. Because SDE’s rates measure dropout and graduation rates for each cohort of students, its methodology requires collecting dropout data over four consecutive years and graduation rates after the cohort of students would normally graduate.

Rather than follow a class of students from ninth grade through graduation, however, the state could calculate dropout rates beginning in 2007 by identifying the number of students that drop out in each grade between two consecutive years. Specifically, the state could measure dropouts by identifying the number of students who took the ninth grade STAR test in 2006 but who were not reported as enrolled in school for the tenth grade STAR test in 2007. (The STAR program collects data on all students enrolled at the time of testing-not just those who take the tests.)

With the student identifiers in place, the state would lack only one piece of data needed to develop graduation rates-a list of students (with their identifier number) that graduate in 2007. Just as the state collects data on all enrolled students in grades 2 through 11 as part of STAR, the state could request districts supply the state with similar data on each year’s graduates. Obtaining dropout and graduation data through STAR would allow SDE to discontinue its current collection of these data. As a result, the Legislature may be able to implement this change with little or no additional cost.

To improve the accuracy of dropout and graduation data, therefore, we recommend the Legislature require SDE to begin collecting student-level data on high school graduates, including each student’s unique identifier number. The requirement would begin with the class of 2007. We also recommend the Legislature require SDE to report to the fiscal and policy committees on the options for adding the improved dropout data to the API and for strengthening local accountability for graduation under NCLB. This would provide the Legislature with information needed to monitor the implementation of including dropout and graduation rates in the state and federal accountability programs. We recommend requiring this report by January 1, 2006.

Increase Flexibility Over the Use of State Resources

We recommend the Legislature extend the consolidation of categorical programs initiated in the 2003‑04 legislative session and give schools and districts greater flexibility to address the needs of students at risk of dropping out.

In 2004, the state enacted Chapter 871 (AB 825, Firebaugh), which consolidated eight categorical programs into a “pupil retention block grant.” Included in the block grant are funds for continuation schools, opportunity classes, and tenth grade counseling. Research on alternative programs suggests that students are more likely to drop out of alternative schools than if they had remained in their regular high school. By consolidating these funds, therefore, the act gives schools significantly greater flexibility to use funds in ways that reduce dropout rates.

Most of the resources that support educational services for low-performing students, however, were not included in the consolidation. The 2004‑05 Budget Act provides more than $1.2 billion in additional resources for helping low-achieving students through the state Economic Impact Aid (EIA) and Targeted Instruction Improvement Grants programs. Districts also receive smaller amounts of funds for services affecting this population through a variety of small programs. For example, districts spend about $21 million each year to notify and meet with parents of truant students through two state-mandated local programs.

Each of these programs comes with various requirements and prohibitions on the use of funds locally. The EIA funds, for example, must supplement the educational program for those students identified as eligible for program services. Remedial instruction funding can be used to supplement a student’s educational program outside of the regular school day or school year. These rules were designed to prevent districts from using these supplemental funds for base program expenses such as teacher salaries, textbooks, or utilities.

As discussed above, research suggests that supplemental services are not the most effective way to increase achievement and reduce dropouts. Schools must build the school’s program and culture around the goal of helping all students achieve. Schools that attempt such a change can find the categorical rules difficult to accommodate. For example, the EIA requirement to use program resources for supplemental services limits principals’ ability to use funds as part of the school reform effort. Similarly, state truancy mandates limit schools’ responses to the problem.

While the changes in AB 825 provide a good start, we recommend the Legislature extend the reforms in a way that increases local flexibility and accountability for improving student performance and increasing graduation rates. We have recommended in past years that the Legislature restructure these programs and increase local accountability for achieving the goals of these programs. By grouping the major categorical programs into block grants, the Legislature could significantly reduce the restrictions on local use of the funds and address inequities in existing funding formulas. By highlighting the effectiveness with which districts use these supplemental funds, our accountability provisions also would stress the Legislature’s concern with the problems of low achievement and dropouts. We continue to believe in this approach. (Please see our 2002‑03 and 2003‑04 Analysis of the Budget Bill, beginning at page E-77 and E-43, respectively, for more detail.)

Encourage More Curricular Choices for Students

Currently, the only state-developed path to a postsecondary goal that is available to all students is the A through G requirements, which are required for admission to a four-year public university in California. To satisfy these requirements, most students must carefully plan their four years in high school. The majority of high school students suffer from the lack of similar paths that help them achieve their post-high school goals. Since less than a one-quarter of students who enroll in ninth grade satisfy the A through G requirements upon graduation, the remaining students must find ways to connect school to their postgraduation goals without clearly defined course sequences to assist them.

In the next chapter, we recommend the Legislature take a series of actions to help schools develop a variety of curricular options for students and help students and parents make informed decisions about their choice of programs. Our goal is encouraging schools to create academic and vocational programs that respond to the interests and needs of students. Our proposal also would require districts to provide academic and career counseling to help students and their parents make informed choices about their high school plan. This means providing assistance in refining each student’s long-term goals, fully understanding the high school options available, and gauging the likelihood of success in their choice.

We think these recommendations would help all students-and particularly students at risk of dropping out-use high school as effectively as possible to work toward their goals in adult life. Please see our recommendations in the next chapter of this report.

Evaluate the Effectiveness of Remedial Programs

We recommend the Legislature direct SDE to develop a proposal to evaluate remedial education programs and state “social promotion” policies.

An obvious solution to improving achievement and reducing dropouts in high school is to reduce the number of low-performing students entering ninth grade. Several state policies encourage districts to address low achievement in elementary and middle schools. We think the state should dedicate a modest amount of funds to evaluate the effectiveness of two of these policies in addressing low achievement-funding for supplemental instruction and state social promotion mandates.

Supplemental instruction programs reimburse districts for each hour of additional class time that is provided to students outside of the regular school day. The state’s funding rate assumes a student-teacher ratio of about 30 to 1, which is identical to the formula used to pay for summer school programs. We think it is likely that this level of resources does not provide adequate support for effective remedial instruction programs-addressing the academic deficiencies of low-performing students may require a lower student-teacher ratio. Unfortunately, we were unable to locate any studies on the subject of effective remedial approaches.

The Legislature also enacted social promotion policies in the mid-1990s, which require districts to establish policies for identifying students who need additional help before moving up to the next grade. Students who are not achieving at the minimum level identified by the district for promotion to the next grade must receive supplemental instruction. As a result, the promotion mandates work in tandem with the supplemental instruction programs.

The state has never evaluated the promotion program. Given the lack of significant improvement shown by low-performing students in the elementary and middle grades, STAR data suggest that most district social promotion and remedial education programs are relatively ineffective. Evaluating the local implementation of these policies, however, may help the state identify local practices for identifying and serving low-achieving elementary and middle grade students who are successful in raising achievement. In addition, the state could evaluate whether programs tailored for specific subgroups of students yield better results than programs that attempt to include students with a variety of educational needs.

Therefore, we recommend the Legislature direct SDE to develop a proposed design for this evaluation. The Legislature could review this proposal to ensure it accomplishes its goals in evaluating these programs and to determine the amount to appropriate in the annual budget act. Based on past evaluations, we think this evaluation would cost about $400,000 and could be supported with federal funds.

Conclusion

The state plays a critical role in focusing attention on the problem of high school dropouts and giving educators better ways to address the problem. Our recommendations would strengthen existing accountability programs, improve information available to parents and educators, and increase options available to students. In the next chapter, we examine the curricular options available to high school students and discuss specific steps to increase the choices available to students.

Chapter 4

In this chapter, we take a closer look at the problems faced by students who graduate from high school but do not satisfy the minimum course requirements for entry into UC or CSU. This group constitutes just under one-half the entering ninth grade class and two-thirds of high school graduates. The general track follows two main paths after high school-continued education in community college or employment. Our review of research and data show that this group suffers from some of the same problems that affect dropouts-high schools often are not organized to help students connect their schooling to their post-high school goals.

High Aspirations, Performance Below Standards

As discussed earlier, data currently are not available to directly measure the performance of students over time. By combining data from different sources and making several key assumptions, however, we can paint a rough picture of the achievement and post-high school aspirations of students in the general track. This analysis suggests that most general track students perform somewhat below state standards in high school.

A significant proportion of students in the general track want to go to college. The postsecondary aspirations of this group, however, far exceed their readiness for college. The mismatch between the performance and aspirations of general track students has important implications for the success of this group after graduation.

Most Students Want to Attend College

The general track contains students with a wide range of ability and achievement. For the most part, however, general track students score in the basic level on STAR. As discussed earlier in the report, the data also suggest STAR scores for this group decline somewhat in eleventh grade. We view this decline as an indicator of falling student motivation.

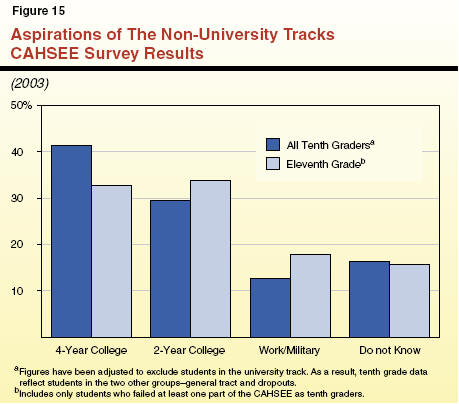

Most general track students also begin high school with the goal of enrolling in college. Figure 15 shows survey results taken at the time students took the CAHSEE in 2002‑03. The survey includes virtually all tenth grade students plus eleventh grade students who did not pass the test the previous year. We modified the tenth grade data by subtracting the proportion of students in our university track from the percentage of students in the survey aspiring to a four-year college.

As a result, data shown for tenth grade students represent the aspirations of students in the general track and those who will eventually drop out of school. As the figure shows, 71 percent of these tenth graders want to enroll in college-41 percent in a four-year university and 30 percent in a community college or technical school. Only 12 percent of students plan to work or enter the military upon graduation.

The aspirations of eleventh grade students who failed the CAHSEE on the first attempt are very similar to those of the nonuniversity track tenth graders. We estimate that about one-half of students in the general track took a CAHSEE test in eleventh grade. Despite having failed at least one part of the CAHSEE, about one-third of the group hopes to enroll in a university. Another one-third plans on attending a community college. Only 18 percent plan on working after graduation.

What actually happens to students suggests these aspirations are unrealistic. About 40 percent of the general track will go on to community college-far fewer than the 70 percent who plan to go to a four-year university or community college. Similarly, roughly 60 percent of this group will go directly to work after graduation-far more than the 12 percent to 18 percent reported in the CAHSEE survey.

The fact that so many students do not realize their postsecondary education goals immediately after college suggests these aspirations often represent vague hopes rather than firm plans. How can high school students get so close to graduation without a more realistic picture of their options after graduation? As we will see in the next section, the experience of high school graduates who enroll in a community college indicates that even students who make it to college often do not understand what it takes to reach their postsecondary goals or realistically assess their chances for success in college. Together, the CAHSEE survey data and the community college experiences of graduates suggest a wide swath of high school students have only vague ideas about how to use their high school years to achieve their postgraduation goals.

Many Students Unprepared for College

About 150,000 recent high school graduates (ages 18 or 19) enroll in CCC each fall. This represents two-thirds of students who enroll in postsecondary education after high school. Most of these students did not satisfy the A though G requirements in high school, and are part of our general track of students. Only about one-third of enrolling CCC students successfully complete a CCC course of study. Within six years of enrolling, about 25 percent transfer to one of the public universities and another 7 percent receive a two-year academic or vocational certificate or degree but do not transfer to a four-year institution.

Low motivation and poor preparation lie at the foundation of these low success rates. For instance, our review of CCC data reveals that:

A Significant Proportion of High School Graduates Drop Out of Community College After Only One Semester. Almost one-half of recent graduates enrolling in a community college attend on a part-time basis. Of this group, 40 percent fail to return the next semester.

More Than 40 Percent of Recent Graduates in CCC Need Basic Skills Remedial Courses. State-required placement tests show that recent high school graduates enrolling in CCC need to repeat high school courses in basic English reading and writing (at least two levels below the transfer freshman composition course) and mathematics (below Algebra I).

Many College Students Are Still Unclear About the Role of Education in Their Lives. About 25 percent of recent high school graduates begin community college with no declared goal for what they want to achieve in college even though the CCC course planning process encourages students to design their schedules according to their personal goals.

These data suggest that a significant proportion of recent high school graduates who enroll in community college are simply not ready for college. These students do not have the motivation and/or academic skills needed to succeed in college. Many arrive at college without a clear picture of what they hope to accomplish while in school. A community college instructor quoted in a 2003 report by Policy Analysis for California Education (PACE) on the transition from high school to community college commented:

For some students, the first year of community college is grade 13. It seems that they are just continuing on-all of their friends are coming here, they are just moving along with the pack. There’s not even necessarily (for some of the first-year students) an acknowledgement . . . that this is even college.

Students Need Better Information About College

Recent studies suggest these problems result from the failure in high school to give students information that would help them answer two key questions: (1) what level of achievement in high school is needed for success in college and (2) how does each student’s high school record compare to the standard for success in college? Studies we reviewed found that:

Counselors Often Recommend College for Virtually All Students. Research on high school counseling programs found that counselors often “advise college for almost everyone.” Even with lower-performing students, counselors are “reluctant to confront students who had unrealistic expectations regarding college or job plans.”

Students Are Not Aware That High School Achievement May Not Meet CCC Standards. The PACE report on community colleges found that many students were not aware that passing a high school course does not mean a student has met CCC standards. As a consequence, community colleges often require students to repeat basic high school mathematics and English courses. The report concludes that students ”do not understand what is expected of them in college, nor the level of academic preparation required of them to handle college-level work.”

General Track Students Are Unfamiliar With the A Through G Requirements. The PACE study also found that less than one-half of students planning to attend a CCC after graduation were familiar with the A through G requirements. As a result, students interested in transferring from community college to a four-year university may be unaware they must first satisfy the A through G requirements in community college before they can begin taking transfer-level courses.

As we discuss in the next chapter, somewhat better signals have been developed for students who want to attend UC or CSU after high school. The A through G requirements define the precollegiate courses students must pass. Both UC and CSU establish minimum grade point averages for admission, and most students must take the SAT. These requirements have two functions. First, they help the universities identify students who are prepared for higher education. Second, they give students feedback on whether they are achieving at levels consistent with being prepared for college.

No similar signals have been developed for students planning to go to a community college. This has negative consequences for students. As one report concludes: “Students’ failures arise not from barriers inside colleges, but from a failure of colleges, and especially community colleges, to convey clear information about the preparation that high school students need in order to have a strong chance of finishing a degree.”

Payoffs to High School Vocational Education Are Low

Not all students want or need to attend college after high school to reach their career goals. Vocational education is another way schools have tried to help students use high school to reach their long-term goals in the workplace. In this section, we examine the impact of secondary vocational education on wages and the likelihood that a student will attend college. Research indicates that vocational courses at the secondary level do not provide significant benefits to most students. While research indicates that sequences of vocational courses can result in significant wage increases, these sequences have not been implemented with much vigor statewide. As a consequence, existing vocational education courses do not offer students an alternative that helps them find jobs with long-term career possibilities.

Participation in Vocational Education Declining

The participation of high school students in vocational education has been declining for many years. In our 1994 report School-to-Work Transition, we noted a 20 percent reduction in high school student attendance at ROC/Ps between 1983 and 1993. This reduction was, in part, caused by the enactment of high school graduation course requirements in 1983.

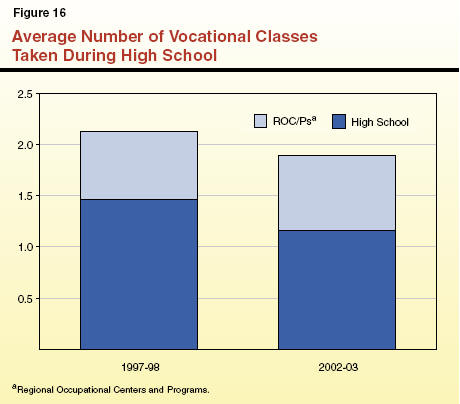

The decline in participation in vocational education has continued in recent years. Figure 16 displays the average number of vocational classes students took in 1997‑98 and 2002‑03. The figure includes all classes listed by districts or ROC/Ps as “vocational,” from basic courses such as keyboarding to high-level occupational courses. Since 1997‑98, vocational enrollments have declined from 2.2 courses to 1.9 courses per student. Of course, not all students take two vocational courses. National studies show that almost all students take at least one vocational class. Only a small proportion of students take three or more vocational courses.

The figure also shows that while the average number of vocational courses offered by high schools dropped sharply over the period, it increased somewhat for ROC/Ps. As a result of these trends, ROC/Ps now provide a higher share of high school vocational courses.

Secondary Vocational Courses Have Little Impact

A great deal of research has focused on the question of whether vocational courses impart significant academic or occupational skills that help students find better jobs and earn more. Figure 17 summarizes the findings common to many of these studies. In general, the conclusion of these studies is that high school vocational courses may provide short-term value to students-in the form of increased employment and wages-but have little effect on academic outcomes.

|

Figure 17 Impact of Secondary

Vocational Education on |

|

|

|

|

|

Dropouts |

Little evidence that vocational programs reduce dropout rates. |

|

Employment |

Small short-run increases in employment. |

|

Earnings |

Modest increases only from completing a sequence of courses in an occupational area. |

|

Academic achievement |

No increase or decrease in academic skills. |

|

College attendance |