February 2005

State agencies purchase about $4.2 billion annually in prescription and nonprescription drugs. The agencies purchase the drugs as part of their responsibilities to deliver health care services to their program recipients. Our review—which focused on 10 percent of these purchases—found several deficiencies in the state's procurement of drugs which lead to it paying higher costs than necessary. We make a number of recommendations to correct these procurement and administrative deficiencies. If implemented, they would generate savings totaling tens of millions of dollars annually.

State agencies purchase about $4.2 billion annually in prescription and nonprescription drugs. These agencies purchase the drugs as part of their responsibilities to deliver health care services to their program recipients. For example, the Department of Mental Health (DMH) provides medications to patients residing in state hospitals. The Public Employees' Retirement System (PERS), as part of its health care coverage plans, pays for medications for public employees, their dependents, and retirees. Figure 1 identifies major state entities that purchase drugs, the primary recipients of those drugs, and the annual purchase amounts.

|

Figure 1 Annual State Drug

Purchases |

||

|

(All Funds) |

||

|

Entity |

Drug

Purchase |

Recipients Served |

|

Medi-Cal |

$3,150.0b |

Medi-Cal recipients |

|

Public Employees’ Retirement System |

640.0 |

Public employees, dependents, and retirees |

|

University of California |

223.0 |

Students, clinics, and hospital patients |

|

Corrections |

128.5 |

Inmates |

|

Mental Health |

30.1 |

State hospital patients |

|

Developmental Services |

15.3 |

Developmental center residents |

|

Alcohol and Drug Programs |

4.5 |

Narcotics treatment clients |

|

Veterans’ Affairs |

3.3 |

Veterans’ home residents |

|

California State University |

2.0 |

Students |

|

California Youth Authority |

1.8 |

Wards |

|

Total |

$4,194.0 |

|

|

|

||

|

a Legislative Analyst's Office estimates based on the best available data. |

||

|

b Net of rebates. Amount does not include Medi-Cal managed care drug expenditures. |

||

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the growth in prescription drug costs has outpaced every other category of health expenditure. California, like all other states, has experienced this growth in prescription drug costs. According to a 2002 Bureau of State Audits review, the five state agencies that most frequently purchase drugs experienced an annual average increase of 34 percent in their drug costs from 1996 to 2001.

In this report, we examine how the state purchases drugs for its program recipients. Specifically, our report identifies recent actions that have helped lower some drug costs, examines state agencies' purchasing practices, and makes recommendations for improving the state's costs for drug purchases. The report focuses on the $400 million in annual drug purchases which are most directly affected by the state's procurement and administrative operations. This report, however, does not examine how the state's medical practices influence drug utilization. While we believe changes to the state's medical practices are a fruitful area for future study, this subject was beyond the scope of this report. In addition, this report does not examine drug purchasing by individual Californians, the Governor's "California Rx" proposal to assist low- and moderate-income citizens in obtaining drug discounts, or the new Medicare drug benefit. These matters are discussed separately in a recently released report, and our forthcoming Analysis of the 2005-06 Budget Bill.

During our review, we discussed drug procurement practices with representatives of the University of California (UC) and the Departments of General Services (DGS), Developmental Services (DDS), Corrections (CDC), and Mental Health. In addition, we gathered information from PERS, California State University, the Departments of Health Services (DHS), Alcohol and Drug Programs (DADP), and Veterans Affairs (DVA), and state contractors involved in drug procurement transactions. We also met with experts on the federal and other states' drug programs.

There are many components to the nation's drug market which affect the prices that the state pays for drugs. Below, we describe how federal laws affect state government purchasing activities and how state entities conduct their drug purchases. (See the nearby box for a broader overview of the drug market.)

U.S. Constitution Regulates Interstate Commerce. The U.S. Constitution prevents states from enacting laws that regulate commerce in other states. This "commerce clause" of the Constitution limits states from passing laws that regulate or affect the prices charged for drugs out of state. For example, the commerce clause has been interpreted as preventing a state from passing a law requiring drug manufacturers to charge the state the lowest drug prices in the nation. Such a provision would alter the prices that drug manufacturers can charge in other states by placing a "floor" on their selling prices.

Drug Prices Heavily Controlled by Federal Law. In contrast, the federal government is authorized to pass laws that regulate drug prices. Under this authority, the federal government has enacted legislation that requires drug manufacturers to offer their lowest prices to federal agencies. The federal government has adopted statutes guaranteeing deep drug discounts to the Veterans Administration (VA), Department of Defense, the Medicaid Program, and other specified public health programs. Under federal law, if drug manufacturers offer their federal prices to nonfederal agencies, then the prices they offer to the federal government generally would have to be lowered further. Under certain conditions, however, the federal regulations allow some state programs to seek further price reductions without affecting federal pricing agreements.

In addition, the federal government has implemented trade agreements and associated confidentiality rules which limit the information that is publicly available about drug prices. Consequently, the actual prices paid by public and private entities tend to be unknown. The most commonly available information is the drug's average wholesale price (AWP)—the price that manufacturers suggest wholesalers charge pharmacies. Private and public entities tend to compare their own drug purchase prices to AWP. In addition to AWP information on drug prices, academic studies also provide some information on drug prices.

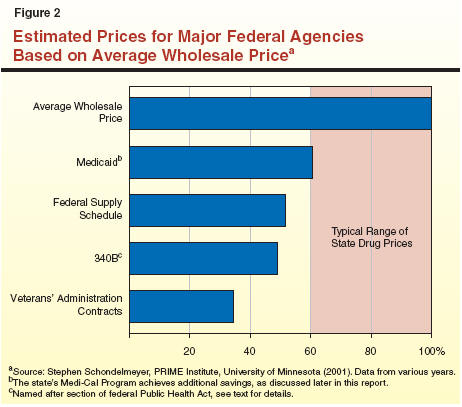

Figure 2 identifies specific federal drug programs and shows their prices relative to AWP. As the figure shows, the federal government pays between 35 percent and 60 percent of the AWP for its drug purchases. The various federal drug programs are:

Because of different laws and procurement practices, state agencies in California purchase drugs in different ways as summarized in Figure 3 and discussed in more detail below. Some state entities are able to access federal drug pricing programs. For those state entities that do not qualify for federal drug discounts, the lowest achievable drug prices would tend to range between 60 percent and 100 percent of AWP (see Figure 2).

|

Figure 3 How State Entities in California Purchase Drugs |

||

|

Purchasing Entity |

Drug Purchase Method |

Cost

Control |

|

Medi-Cal |

Directly reimburses pharmacies for cost of drugs dispensed. Indirectly pays for drugs used by Medi-Cal patients enrolled in managed care plans. |

Medicaid drug prices under federal law. State supplemental rebates. Preferred drug list. |

|

Public

Employees’ |

Included in health care plan coverage. |

Health care benefit Pharmacy benefit manager. |

|

University of California |

Orders placed through Novation contracts. Orders distributed by Cardinal Health. |

304B pricing for some hospitals and clinics. Group Purchasing Organization (GPO) discounts. |

|

Department

of Veterans’ |

Orders placed and distributed through federal contracts. |

Federal drug prices for veterans. |

|

Department of General Services |

Orders placed through Massachusetts Alliance and state contracts. Orders distributed by McKesson Corporation. |

Negotiated and competitive drug contracts. GPO discounts. Common drug formulary. |

Medi-Cal. The DHS administers the Medi-Cal Program (California's version of the federal Medicaid Program), which provides health care services, including prescription drugs, to eligible low-income persons. Medi-Cal pays for the cost of outpatient prescription drugs in one of two ways:

Medi-Cal controls direct reimbursement costs in the following two ways:

PERS. State employees and many local government employees receive health insurance benefits through PERS. Currently, PERS offers three health maintenance organization (HMO) plans and two self-insured preferred provider organization (PPO) plans. Two HMOs—Kaiser Permanente and Blue Shield—manage their own prescription drug programs and offer this coverage as a part of their overall health insurance packages. The third HMO—Western Health Advantage—contracts with a pharmacy benefits manager (PBM) to administer its prescription drug program. (A PBM is a private third party that manages drug benefits for large groups of individuals.) Similarly, PERS contracts with a PBM (currently Caremark) to provide prescription drug services for the PPO plans. The PERS annually negotiates rates with HMOs and sets PPO premiums. The costs of drug coverage are included in these annual rate negotiations.

UC. The UC purchases drugs for its medical centers and student health clinics. As part of a nationwide network of academic medical centers, each UC facility purchases drugs through a group purchasing organization (GPO) called Novation. (A GPO is a drug volume purchasing entity.) These drugs are delivered directly to the campus sites by a pharmaceutical distribution company (Cardinal Health). State law does not require UC to purchase drugs through DGS. All of the UC medical centers (Davis, Irvine, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego) are 340B hospitals and, therefore, are eligible for the federal drug program discounts. In addition, the UC medical centers provide services to some Medi-Cal patients.

DVA. The DVA operates three homes in which veterans receive medical, rehabilitation, and residential services. Under an agreement with the federal government, DVA is able to purchase drugs through federal VA drug contracts. Participation in the VA drug program is restricted to veterans.

DGS Purchases Drugs for Remaining Agencies. The DGS is responsible for procuring drugs for CDC, DMH, DDS, California Youth Authority, and the California State University's student health centers. The DGS contracts with a vendor, McKesson Corporation, to process departmental drug orders. McKesson is responsible for filling and then distributing those drug orders to the departments. McKesson acquires the drugs through (1) competitively procured state contracts for generic drugs, (2) negotiated state contracts for brand-name drugs, or (3) the Massachusetts Alliance, a GPO consisting of both public and private agencies. For drugs that are not available through these methods (that is, noncontract purchasing), McKesson acquires the drugs at discounted wholesale prices (below AWP). Figure 4 shows the annual order volumes and drug costs for each of these methods. (What constitutes a "drug order" varies depending on the type of drug and its manufacturer.) McKesson receives a 0.5 percent service fee for each order.

|

Figure 4 Annual Drug

Procurements |

||

|

November 2003 Through October 2004 |

||

|

Purchase Method |

Drug Orders |

Costs |

|

Noncontract |

1,129,750 |

$83.7 |

|

Contracts: |

|

|

|

Negotiated contracts |

127,956 |

$58.3 |

|

Massachusetts Alliance |

1,285,427 |

28.5 |

|

Competitive contracts |

478,782 |

6.7 |

|

Totals |

3,021,915 |

$177.2 |

State agencies purchase a wide variety of drugs. The types of drugs purchased depend on the medical needs of their respective patient populations. For example, in Medi-Cal and other state agencies such as CDC and DMH, the most commonly purchased prescription drugs are those used to treat mental illness. In addition, some state agencies purchase drugs for the treatment of HIV/AIDS. In DVA, where most of the medical services relate to elder care, the most commonly purchased drugs are those used to treat high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol, and dementia. For PERS, which provides medical services for employees and retirees, the most commonly purchased drugs are those used to treat high cholesterol and blood pressure, various stomach ailments, and depression.

Recent state legislation and actions by the administration should lead to lower drug costs in the future. We discuss these developments below.

Significant Legislation. Since 2000, the Legislature has passed a number of bills aimed at (1) lowering state drug costs and (2) providing additional information on state drug purchases. As summarized in Figure 5, most of these bills have directed the state to conduct a number of new procurement-related activities. For example, Chapter 483, Statutes of 2002 (SB 1315, Sher), authorizes DGS, after receiving a vendor's final cost proposal, to enter into negotiations with the vendor in an effort to receive even lower prices. As described in Figure 5, the administration has made some overall progress in implementing portions of these bills. The savings achieved from implementing these new procurement authorities, however, are unknown. Several steps have also been taken to reduce drug costs in Medi-Cal. Some of these steps, such as reducing the pharmacy reimbursement rate, will reduce costs in the near term. Other actions—such as requiring drug companies to provide DHS with previously unavailable pricing information—should enable the state to achieve greater long-term savings.

|

Figure 5 Recent Significant Legislation to Lower Drug Costs |

|

|

Major Provisions |

Accomplishments |

|

Chapter 127, Statutes of 2000 (AB 2866, Migden) |

|

|

Negotiation of drug rebates. Use of a Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM). Includes inmates in the AIDS Drug Assistance Program. Membership in a group purchasing organization (GPO). |

Department of General Services (DGS) negotiated one drug rebate. DGS purchases drugs through the Massachusetts Health Alliance GPO. |

|

Chapter 483, Statutes of 2002 (SB 1315, Sher) |

|

|

Negotiation of drug discounts and refunds. Expands the use of a PBM. Requires Departments of Corrections (CDC), Mental Health (DMH), Developmental Services (DDS), and Youth Authority participate in DGS’ drug procurement strategies. Authorizes DGS to explore new procurement strategies. Authorizes local governments to use state’s drug contracts. Use of bulk purchasing agreements with nongovernment entities. |

DGS has signed four negotiated drug contracts. Departments participate in DGS drug program. DGS and departments have created a common drug formulary (CDF). CDC is currently using the CDF. In 2005, DDS and DMH will also use the CDF. In 2005, DGS intends to release a bid for a PBM for parolees’ drug purchases. |

|

Chapter 208, Statutes of 2004 (SB 1113, Chesbro) |

|

|

Reduces Medi-Cal reimbursements for drug ingredient costs. Increases dispensing fees up to $8 for some prescriptions. Requires that manufacturers provide Department of Health Services (DHS) with information on drugs’ average sale price and the wholesale selling price. |

The 2004-05 Budget Act estimates savings of $104 million ($52 million General Fund) from the reimbursement reduction. DHS is working with drug manufacturers to receive pricing information. |

|

Chapter 383, Statutes of 2004 (SB 1426, Ducheny) |

|

|

Requires that CDC adopt drug utilization policies and report by April 1, 2006 on their impact. |

CDC is currently developing policies. |

|

Chapter 938, Statutes of 2004 (AB 1959, Chu) |

|

|

Requires that the Bureau of State Audits conduct an audit of state drug purchases by May 2005 and, if necessary, every two years afterwards. |

May 2005 audit underway. |

Strategic Sourcing Has Potential to Reduce Future Drug Costs. In 2004, DGS began an effort to lower the state's overall goods and services costs. This effort—called "strategic sourcing"—involves using past years' purchasing information and standard procurement methods to create new contracts for those same goods and services. The new contracts should result in lower costs. The DGS has identified drug contracts as one of the state's goods that would benefit from strategic sourcing techniques. The estimated savings in drug costs from this effort is unknown but expected to be under $4 million annually.

Common Drug Formulary (CDF) Provides Some Purchasing Leverage. Chapter 483 authorizes DGS to explore procurement strategies that could result in lower drug costs. One of these strategies is the use of a CDF. Since 2001, DGS, CDC, DMH, and DDS have been developing the state's CDF for anti-psychotic drugs. Similar to the Medi-Cal PDL, the CDF involves two tiers—Tier One for drugs that can be prescribed without prior authorization and Tier Two for drugs that can be prescribed after receiving prior authorization. The state can use the CDF to lower drug costs. For example, if a drug is costly and the marketplace offers an equivalent, less costly drug, the state can put the more costly drug in Tier Two. This action could reduce the number of orders for the drug and/or act as an incentive for the drug manufacturer to negotiate with the state for a lower price. According to DGS, it has used this technique once. In this instance, the drug manufacturer was willing to renegotiate their drug price in order to move their product to Tier One status.

CDC Has Addressed Some Problems in Its Pharmacy Operations. Between 2000 and 2002, several external studies were conducted regarding CDC's pharmacy operations. These studies found that CDC's pharmacy program lacked the basic administrative infrastructure and management tools needed to effectively control drug costs and provide quality care. Specifically, these studies found that CDC did not have a CDF, lacked appropriate oversight of its pharmacy operations, and used an outdated pharmacy automation system that could not perform many quality and cost-control functions.

During our review, we met with CDC Health Care Services Division (HCSD) staff to follow up on the department's efforts to implement the studies' recommendations. Based on those discussions, we found that CDC has taken some steps to manage its pharmacy costs. For example, the department (1) uses the state's CDF, (2) has implemented guidelines for prescription doses, and (3) substitutes generic drugs for brand-name drugs in high-cost high-volume medication categories. In addition, HCSD is producing quarterly reports on each prison's usage of high-volume and high-cost medications. Prisons' medical and pharmacy staff are responsible for correcting deficiencies identified in these reports.

Our review found that there are three major groups of state drug purchasers. The largest group is the Medi-Cal Program, accounting for $3.2 billion of the state's drug purchases. We found that Medi-Cal drug prices are primarily affected by the federal Medicaid Program and the state's supplemental rebates. The PERS comprises the second group and it accounts for $640 million of the state's drug purchases. Our review found that the PERS' drug prices are primarily affected by the state's overall negotiations for the health benefit plans. In other words, the majority of these two groups' drug purchases are affected by factors other than the state's day-to-day procurement and administrative procedures that are the focus of this report.

The third group, accounting for only 10 percent—or about $400 million—of the state's drug purchasers consists of UC and DGS. This group's drug purchases are primarily affected by the state's procurement and administrative operations. Our review found several areas in which the state's activities were deficient. These deficiencies lead to the state paying higher drug costs than necessary. We discuss these deficiencies in detail below.

Our review of state drug procurement practices found that DDS, DMH, and DADP are purchasing drugs for Medi-Cal patients in their programs at relatively high prices and are not taking advantage of the better prices, including rebates, available under the federal Medicaid statute.

DDS and DMH. About 97 percent of the population served in the five developmental centers (DCs) operated by DDS is eligible for Medi-Cal. The DDS does obtain reimbursement under Medi-Cal for the drug costs of these DC clients. However, the current practice is for the costs of drug purchases for DC clients to be "bundled" together with other types of ancillary medical costs in billings for reimbursements through the Medi-Cal Program. Under this practice, the prices being paid by the state, and built into the bundled rates, are not the lowest available under the federal Medicaid statute. Instead, the bundled rates use the prices available through the McKesson contract. As described earlier, those prices are not nearly as low as those available under Medicaid. Lower prices would be available to the state if the drug costs for Medi-Cal eligibles in the DCs were accounted for separately and not bundled together with other medical costs. The same practice of rate bundling is currently in place for state hospital patients, although relatively few of these patients are eligible for Medi-Cal.

DADP. Similarly, the costs of methadone provided to beneficiaries under DADP's Drug Medi-Cal Program (which provides substance abuse treatment for Medi-Cal beneficiaries) are bundled together with reimbursements for counseling and other components of narcotics treatment services. The state does not collect the information needed to obtain rebates from methadone manufacturers. Thus, the state is not obtaining the discounts available for its methadone purchases.

The commerce clause of the U.S. Constitution and other federal laws limit the ability of states to obtain discounts on their drug purchases. A number of states, however, have attempted to use the purchasing power of their Medicaid programs to reduce drug costs in other state programs. For example, some states have attempted to reduce drug prices for non-Medicaid populations by allowing drug manufacturers' products to remain on their Medicaid formularies only if they provide discounts or rebates to other state programs. In 2001, Michigan proposed to obtain drug manufacturer rebates for various non-Medicaid programs in that state, including mental health services and hospitals. Maine has also enacted a plan (known as Maine Rx) that, among other provisions, will require drug manufacturers to agree to negotiate rebates for drugs purchased for low- and moderate-income residents.

The Maine and Michigan efforts to extend Medicaid pricing to other programs have been slowed by litigation brought by the drug industry. A recent U.S. Supreme Count decision may better enable states to pursue such efforts. A June 2003 decision (Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America v. Walsh) has been interpreted by academic researchers as allowing states, under certain circumstances, to use their Medicaid Programs as a means to obtain lower drug prices for non-Medicaid populations. States may be able to do this as long as their actions would further the goals of Medicaid, such as providing assistance to individuals who might otherwise end up on the Medicaid rolls. Also, the state would have to receive prior federal approval for such actions.

To date, however, California's efforts to use Medi-Cal as a means to secure discounts on drugs have been limited to Medicare patients and workers' compensation. For example, under Chapter 946, Statutes of 1999 (SB 393, Speier), any pharmacy that participates in Medi-Cal is obligated to limit its charges for drugs sold to Medicare patients to the Medi-Cal pharmacy reimbursement rate plus a small transaction fee. As a result, Medicare patients are able to purchase drugs from certain California pharmacies for a lower price than they would otherwise. Chapter 693, Statutes of 2001 (SB 696, Speier), requires drug manufacturers to provide additional rebates to further reduce the cost of drugs for Medicare patients. Chapter 693, however, has never been implemented—due in part to administrative problems with the proposed mechanism to pass along rebate savings to patients.

No Statewide Work Plan for Purchasing Drugs. The DGS is responsible for procuring drugs for five state agencies through various state contracts. To accomplish this, DGS evaluates the state's drug purchases and, as necessary, conducts competitive bids or negotiates contracts. For example, in order to reduce state costs, DGS may monitor drug patent expiration dates and, when the expiration occurs, conduct a competitive procurement to acquire the drug at a lower price. These types of activities, however, appear to be conducted without a comprehensive approach. The DGS was unable to produce an annual work plan describing what procurements they will conduct over the year.

DGS Purchases Almost One-Half of Drugs Without Contracts. Large drug purchasers should be able to acquire their most frequently used drugs by establishing contracts with drug manufacturers. Based on competition or negotiations with the drug manufacturers, such contracts should result in lower drug prices. As shown in Figure 4, DGS uses four different methods to purchase drugs for departments. Three of these methods (accounting for 53 percent of DGS drug purchases) consist of using contracts to purchase drugs. Yet, the remaining one-half of DGS' drug purchases are being acquired without contracts including some of the state's most commonly purchased drugs. Given the magnitude of the state's purchases of these noncontract drugs, it is likely that DGS could secure lower prices for some of these drugs through a contract. (We recognize, however, that some companies such as those selling certain HIV/AIDS drugs have refused to contract with any entity.)

DGS Does Not Participate in Drug Reviews. Some drug purchasers participate in independent groups that develop information on the relative effectiveness of similar drugs in various categories. Drug purchasers then apply this information to their purchasing and management decisions. For example, the California Healthcare Foundation and PERS participate in the Drug Effectiveness Review Project (DERP) led by the Center for Evidence-Based Policy. The project's participants believe that purchasing in accordance with evidence-based information will generate long-term efficiencies, more appropriate drug utilization, and improved health outcomes. The state as a whole, however, does not participate in such a group and consequently lacks comparable information that it could use in price negotiations.

The DGS, CDC, DMH, and DDS have worked together to establish the CDF. The California Performance Review (CPR) (a Governor's task force that recently examined state government operations) and our own analysis both indicate, however, that—despite these ongoing efforts—state agencies are not doing all they could to share information and collaborate on a regular basis in their efforts to purchase drugs. The PERS does not share its DERP information with other state agencies. In addition, DGS officials indicated to us that they have had little regular interaction with the branch of DHS responsible for securing supplemental rebates and directly bargaining with drug manufacturers over the price of drugs for Medi-Cal patients. Representatives from UC indicated to us that they initially had encountered difficulty discussing joint procurement strategies with DGS. The DGS representatives indicated to us that they knew little about how the UC system purchases drugs for its large university hospital system.

Although there are some differences in the types of drugs needed by these various state agencies, our analysis indicates that there is a significant overlap in the types of drugs they purchase and in the drug manufacturers with whom they do business. For example, records indicate that UC, DHS, and DGS are all major purchasers of anti-psychotics and anti-depressants—usually from the same drug manufacturers. The lack of ongoing, regular communication and sharing of information among state agencies likely puts the state at a disadvantage in its dealings with these drug manufacturers. For example, DGS might be in a better position to bargain for a lower price for a drug if the department was able to take full advantage of DHS' expertise in negotiating for rebates for that class of medications, or if it were aware of the price that UC was paying. In our review, we could not find any state law that prohibits UC from collaborating with DGS in drug purchasing activities. (Federal law does limit some collaborations between DHS and the state.) Better collaboration between state entities could increase the state's drug purchasing power and further reduce the price it pays for drugs.

State regulations issued by DHS require that any hospital facility (both public and private) with more than 100 beds have its own staff committee to develop its own drug formulary. The current regulations were adopted at a time when the cost of prescription drugs was not a major concern and before state agencies began managing their drug costs in a more comprehensive way. These regulations require extensive duplication of effort by state hospital and DC staffs. In addition, this approach reduces the state's bargaining power by allowing separate state facilities to favor their own selection of drugs. As noted previously, the state has developed a statewide CDF for anti-psychotic medications. Yet, DDS and DMH continue to use their own drug formularies for these same drugs—limiting the applicability and effectiveness of a statewide formulary.

CDC Pays Retail Prices for Parolee Drugs. The CDC operates parole outpatient clinics that primarily provide medication management services to mentally ill parolees. To acquire drugs for these parolees, CDC allows its regional parole offices to negotiate drug contracts with local pharmacies. Under these contracts, local pharmacies fill parolee prescriptions and directly bill CDC for the prescribed drugs. According to CDC, its clinics have entered into contracts which pay for these drugs at retail prices—at a cost totaling about $18 million in 2003-04. Retail prices are somewhat higher than AWP and are probably some of the highest prices paid for drugs. (According to DGS, however, the clinics receive prices slightly below AWP. At the time this analysis was prepared, we were unable to reconcile this discrepancy.)

CDC Pharmacy Operations Improved but Still Lacking. Although CDC has made some progress in addressing deficiencies in its pharmacy operations, we found the CDC still lacks the administrative structure and management tools to effectively administer its pharmacy program. For example, pharmacy services are one of several responsibilities of CDC's HCSD—with few staff dedicated solely to oversight and management of pharmacy operations. Consequently, the prison pharmacies operate somewhat independently and without statewide standards and specific guidelines regarding ordering and dispensing of medications.

At the prison level, many pharmacies continue to use the outdated pharmacy information system, known as the Pharmacy Prescription Tracking System. This system lacks many of the capabilities of newer systems, making it more difficult for pharmacy staff to perform some functions that would help to reduce waste (such as estimating volume of drug purchases and tracking inventory). We also found that CDC, like other state departments, continues to experience relatively high vacancies among its pharmacy staff. These program deficiencies most likely result in the wasting of drugs and missed opportunities to save millions of dollars in the prison pharmacy program.

Our review found several deficiencies in how the state purchases prescription drugs. These findings generally are consistent with prior reviews of the state's drug purchasing practices. For example, in August 2004, a task force released its CPR report to the Governor, which identifies a number of ways to reduce state drug costs. This section of the report discusses potential approaches to lowering the state's drug costs.

One approach to reducing state drug costs, undertaken by some states and local governments, involves importing drugs from Canada and other countries. As described in the nearby box (see page 18), we believe that, absent several significant changes in federal policy and other factors, drug importation would probably not provide a long-term solution to reducing the state's drug purchasing costs. Below, we discuss CPR's approach and then offer our own recommended actions.

The CPR estimates that its drug purchasing proposals would result in $75 million in annual state savings. (We found that CPR produced two differing versions of its proposal—a printed version and an Internet version. We were unable to determine which version contains the official CPR recommendation. For that reason, our review comments on both versions.) The main provisions of the CPR proposal are described below.

Hire a PBM to Administer State's Drug Procurements. The CPR recommends that DGS acquire a PBM to administer the state's drug purchases. The CPR asserts that a PBM could administer the state's drug program at a lower cost and receive lower drug prices than DGS is achieving.

Create Centralized Pharmaceutical Office (CPO). The CPR also recommends that the state create a CPO that would be responsible for all of the state's drug purchasing programs. This office would have the authority to establish relationships with local governments, all state entities, and drug manufacturers. The CPR states that this office would maximize the state's purchasing power.

Maximize State Use of 340B Program. The CPR recommends that the state maximize its use of the federal 340B drug discount program to significantly reduce the drug expenditures of various state departments. Specifically, the CPR proposes that UC or other 340B entities become responsible for providing medical and pharmaceutical services to institutionalized patients of the Health and Human Services (HHSA) and Youth and Adult Correctional Agencies—enabling the state to access 340B drug discounts for those individuals. In addition, CPR recommends that PERS and the State Teachers' Retirement System explore the use of 340B entities to provide health care benefits for employees and retirees.

Promote 340B Program. The CPR further recommends that HHSA promote the 340B program among certain hospitals, community health centers, and eligible entities that do not currently participate in the program.

We have identified a number of difficulties with the approaches recommended by CPR, which we discuss below.

Use of PBM Has Limited Applicability in State Drug Purchases. Typically, a PBM offers a number of services to clients, such as establishing drug formularies, negotiating drug discounts with pharmacies, and negotiating rebates with drug manufacturers. It is unclear to us, however, what benefits a PBM would offer for the majority of the state's drug purchases. For example, for the purchases that DGS oversees, the state already has established a drug formulary, has authority to negotiate drug rebates, and usually does not purchase drugs from private pharmacies (except for parolee services).

Need for CPO Is Limited. The CPR does not specify which state entities would transfer their drug purchasing responsibilities to the proposed CPO. For that reason, it is difficult to assess the benefits of a CPO. As discussed elsewhere in this report, we do see potential fiscal benefits from consolidating some UC and DGS drug purchases. Due to restrictions in federal laws, it is probably not feasible to consolidate Medi-Cal and DGS drug purchases—since DGS is unable to receive Medi-Cal drug prices. Finally, the creation of a new state drug purchasing office could be costly, create organizational difficulties, and provide little strategic advantage to the state over the current arrangement in which procurement duties are already largely concentrated. As we discuss later in this report, we believe there is a better alternative approach for improving collaboration among state agencies.

| Drug Importation Strategies

Due to rapidly escalating prices for prescription drugs from domestic suppliers and pharmacies, interest at all levels of government (and by individuals) in importing prescription drugs from other countries has grown in the past few years. Estimates of the annual prescription drug purchase revenues now flowing from the United States to Canada range from $600 million up to $1 billion. The Congressional Budget Office recently estimated that foreign prices for patented drugs are lower than U.S. prices by an average of 35 percent to 55 percent. These and other reported price differences, however, typically reflect retail prices paid by individual consumers for brand-name drugs. Generic medications—which are a majority of drug sales in the domestic market—typically sell for less in the U.S. than in Canada. In addition, the reported price differences typically are not adjusted to reflect the discounts, rebates, and government actions that allow programs such as Medi-Cal to purchase brand-name drugs at prices well below retail levels. Federal, State, and Local Government Drug Importation Programs. The federal Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 permits prescription drug importation programs if the federal Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) certifies that imported drugs pose no additional risk and would generate significant savings for consumers. At the state and local levels, a number of governments have begun programs aimed at assisting residents who wish to import drugs from other nations. For instance, Wisconsin, Kansas, and Missouri have joined an Illinois program called I-SaveRx (started in October 2004), which allows state residents to purchase prescription medications from Canada, the United Kingdom, and Ireland. Minnesota has established a program to allow eligible state employees to purchase drugs from Canadian pharmacies, as have several U.S. cities. Canada May Restrict Drug Exports. Even if the state were able to reduce costs for its programs in the short run by importation of prescription drugs from Canada, it is not clear that those savings could be sustained in the long run. Since California's population exceeds Canada's, a surge in demand for imported drugs from California could prompt a response that would limit the effectiveness or duration of a state importation program. The Canadian Health Minister, for example, recently stated that his government might take action to end the sale of prescription drugs to U.S. residents if the practice overly strains Canada's drug supply. Also, pharmaceutical companies strongly oppose importation, and some have limited the number of drugs they supply to Canadian businesses whom they believe export drugs back to the U.S. Drug Importation Raises Legal Issues. Part or all of the savings generated by state importation programs could be offset by the potential costs arising from federal or consumer legal issues and ensuring the safety of imported drugs. Federal law strictly limits the types of drugs that may be imported into the United States. An August 2003 letter from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to the California Department of Justice reiterated the FDA's position that almost all importation of drugs to the United States from Canada violates federal law because the medications are unapproved, labeled incorrectly, or dispensed without a valid prescription. Drug importation also raises legal issues related to federal oversight of state health care programs. In order to operate a program to directly import drugs for a state health program, the state likely would need to obtain a federal waiver to maintain federal funding for the participating departments. If DHHS were to approve such a waiver, it could require that California ensure the safety and efficacy of all imported drugs—in effect requiring the state to take on the role normally played by the FDA with respect to protecting the domestic drug supply. Obtaining federal approval of such a waiver seems improbable at this time, given the federal administration's consistent opposition to broad drug importation programs to date. Moreover, as an importing entity, the state might incur substantial costs to provide such assurance, potentially reducing or negating any savings gained through lower prices from foreign markets. In summary, absent significant changes in federal policy and the other factors noted above, the possibility of procuring significant savings for the state's programs through drug importation seems problematic at this time. |

Utilizing 340B Entities Requires Major Restructuring of State Programs. Under the 340B program, federal rules specify that discounts are only available for outpatient drugs provided to patients that (1) have an established relationship with the health care provider (such that health records are maintained by that organization) and (2) receive a range of services from a medical practitioner employed or contracted by the covered entity. In other words, generally the covered entity must provide medical services to the patient beyond prescription services in order to obtain drug discounts through the 340B program.

While the CPR recommendation for the state to maximize use of the 340B program in the prisons or state mental hospitals is technically feasible, we would note that it would require major changes to the state's existing health delivery systems. In order to be compliant with federal law and obtain 340B discounts, state departments would have to reassign some or all of their core health delivery functions and responsibilities to another entity. Such a significant restructuring of the state's medical systems should be considered in the larger context of improving quality of care for institutionalized patients—rather than the more limited context of reducing drug costs.

In the more immediate future, we do believe that there are concrete opportunities for the state to develop new (or build on existing) cooperative agreements that involve 340B entities. For instance, telemedicine offers an opportunity to move further in the direction of shifting CDC inmate health care delivery to an outside provider, including providers which would qualify for the 340B program such as UC. The Legislature may wish to consider building upon the existing cooperative agreements between CDC and UC to expand or enhance the now limited telemedicine program. In addition to expanding the state's access to 340B discounts, an incremental approach would enable the state to evaluate the quality of care and fiscal benefits of shifting inmate health care delivery to UC before expanding the university's role elsewhere in the prison health care delivery system.

Promoting the 340B Program to Other Eligible Entities. Our analysis indicates the CPR's recommendation to promote the 340B program presents a reasonable way that more entities could access drug discounts for the patients they serve and make a more efficient use of their limited resources. It is uncertain, however, whether the state would directly achieve savings from this approach. While the state could direct Medi-Cal beneficiaries to these entities for health care, the Medi-Cal program currently pays net prices (after rebates), which according to DHS, are at least as low as those obtained through 340B.

To address the deficiencies found in our review, we recommend a number of actions that the state could take to improve its procurement methods and reduce state costs for those purchases (see Figure 6). In the detailed discussion of each action below, we have grouped our recommendations as those involving changes in statutes, procurement approaches, and departmental practices. We recognize that some of these steps would take longer to implement than others. Accordingly, in Figure 6 we have categorized the steps as either short- or long-term. When possible, we have also provided our general estimate of the level of savings that they could generate. As a whole, we believe these steps could generate savings totaling tens of millions of dollars annually. The savings would be partially offset by implementation costs that we estimate likely would total under $1 million annually.

|

Figure 6 LAO

Recommendations |

||||

|

|

Estimated Maximum Annual Savingsa (In Dollars) |

|||

|

LAO Recommendation |

Unknown |

Hundreds of Thousands |

Millions |

|

|

Short-Term (Less Than 18 Months) |

||||

|

Require collaboration between state drug purchasers. |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Increase Department of General Services (DGS) staff in order to create more drug contracts. |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Require DGS to develop annual work plan. |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Require DGS participation in drug reviews. |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Direct California Department of Corrections (CDC) and DGS to compare potential methods to lower parolee drug costs. |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Direct Department of Health Services to modify regulations requiring multiple formularies. |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Direct Departments of Developmental Services, Mental Health, and Alcohol and Drug Programs to modify reimbursement systems. |

|

X |

|

|

|

Long-Term (More Than 18 Months) |

||||

|

Request use of Federal Supply Schedule. |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leverage Medi-Cal Preferred Drug List. |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Direct University of California and DGS to identify joint drug purchases. |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Require CDC to report on pharmacy improvements. |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

a Does not include offsetting implementation costs. |

||||

Request Use of Federal Program. Under current federal law, states are not allowed to use the FSS to purchase drugs. If the federal government were to allow the state to use the FSS for state drug purchases, the state could receive significant price reductions for those drugs. For this reason, we recommend that the Legislature adopt a joint resolution requesting Congress to change federal law to allow the state to access the FSS to acquire drugs for some of its state agencies. Although Congress has previously rejected full state access to the FSS for drug purchases, the state could propose a more limited approach. For example, the Legislature could request that federal law allow access to the FSS by residents in state hospitals and DCs. Such a change could result in annual savings of a few millions of dollars. We believe requesting FSS access for state hospital and DC residents is more likely to be accepted by the federal government because these residents are similar to recipients served by other federally funded health care programs.

Enact Statute to Leverage Medi-Cal. In the past, the Legislature has used the Medi-Cal Program as leverage to lower drug costs for Medicare beneficiaries and in other limited circumstances. We believe that a similar approach could also be used to lower state drug costs for other state health programs. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature enact legislation requiring drug manufacturers to provide certain state programs with the same types of supplemental rebates that are available under the Medi-Cal Program. For example, the legislation could help reduce drug costs for specialized health programs such as the "state-only" portions of the California Children`s Services and Genetically Handicapped Person Programs, and parole outpatient clinics. Such legislation would encourage drug manufacturers to provide discounts by allowing, in exchange, their products to remain on the Medi-Cal PDL. This approach would need prior federal approval and could be subject to legal challenges but appears consistent with the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America v. Walsh.

Require Collaboration Among State Drug Purchasers. Currently, state entities typically do not collaborate or share information regarding their drug purchases. For this reason, we recommend that the Legislature require state drug purchasing entities to share information on the purchase of prescription drugs. At a minimum, DGS, DHS, UC, and PERS should share information regularly. (In a subsequent recommendation, we identify how UC and DGS could achieve savings through actual consolidation of drug purchases.) In addition, other state agencies with large drug purchases, such as CDC, DMH, DDS, and DVA should communicate regarding their purchases. On an annual basis, these entities—coordinated through DGS—should provide a report to the Legislature on its collaboration activities and progress in reducing or holding down state drug costs. We believe the collaboration, over time, would help to strengthen communication among state agencies in the purchase of prescription drugs without the costs and difficulties of creating a new state entity to oversee drug procurements, as proposed by CPR.

Direct UC and DGS to Identify Consolidated Drug Purchasing Opportunities. The UC's annual drug purchases exceed all of DGS' annual purchases, yet the agencies do not communicate regularly. By combining the purchasing power of the two entities, we believe cost savings could be found for some state drug purchases. For this reason, we recommend that the Legislature adopt statutory language directing UC and DGS to identify opportunities for consolidating drug purchases. According to staff at the UC Office of the President, the university is willing to explore such collaborations. We believe this action would strengthen the bargaining power of both UC and DGS and potentially lead to lower drug prices for the purchases carried out by both agencies.

Increase DGS Staff to Create More Drug Contracts. As noted earlier, almost one-half of DGS drug purchases are being acquired without contracts—resulting in higher drug prices than necessary in some cases. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature increase the number of DGS staff devoted to state drug purchases. The additional staff should include at least one pharmacist who has experience working with drug manufacturers and government procurements. We estimate the ongoing costs of the additional staff would total a few hundred thousand dollars annually, but could result in annual savings of a few million dollars.

Require DGS to Develop Annual Work Plan for Purchasing Drugs. As we noted, DGS drug purchase strategies have been implemented on an individual basis rather than through a more comprehensive approach. In our view, given its responsibility for procuring almost $200 million annually in drugs, DGS should have a comprehensive annual work plan to guide its drug procurement activities. Consequently, we recommend that the Legislature require DGS to develop an annual work plan for state drug purchases. The work plan should describe what activities DGS will conduct over the year and the potential savings that may result from those activities. With the additional staff recommended above, DGS should be able to prepare such a plan. The DGS could use this work plan to guide its annual drug purchase activities and provide information to the Legislature on the savings it has been able to achieve.

Require DGS Participation in Drug Reviews. As noted above, some state entities participate in groups that provide information on the relative effectiveness of similar drugs in various categories. These data are useful in purchasing and management decisions. Yet, DGS does not currently participate in such a group. Since DGS is responsible for procuring almost $200 million annually in drugs, we recommend that the Legislature direct DGS to participate in an independent group of this type. Using a systematic approach to determine which drugs appear on the CDF could generate long-term savings and improve the quality of health care. Participation in such groups usually requires payment of a fee in the range of $100,000 annually.

Direct DGS and CDC to Compare Parolee Drug Costs. It appears that CDC parole outpatient clinics currently purchase parolee drugs at retail prices—generally the highest level of prices paid. Based on discussions with CDC and DGS, it is our understanding that these departments are currently working together to competitively contract for a PBM to manage parolee medications. We believe this approach would be less costly than purchasing the drugs under contract with retail pharmacies. However, depending on the fees charged by the PBM, it may not be less costly than if CDC were to purchase these medications under contracts negotiated and maintained by DGS. The latter could be accomplished by establishing a system in which parolee drugs would be purchased and dispensed for the parole clinics by the prison pharmacies. Under this approach, the health care professionals who work in the parole outpatient clinics would administer parolee medications. We recommend that the Legislature direct DGS and CDC to compare the overall cost of providing parolee medications through the PBM to the cost of purchasing these drugs under its own contracts, and to choose the least costly alternative.

Require CDC to Continue Pharmacy Improvements. The CDC has made some improvement is its pharmacy operations, but much work remains to be completed to resolve ongoing problems. For this reason, we recommend that the Legislature require CDC to provide an update on its pharmacy program. Specifically, CDC should report at budget hearings on its progress and timeline for implementing recommendations from external studies—including implementing a new pharmacy information system or contract for the service, and establishing statewide policies and procedures for prison pharmacy operations. The department should also report on whether, and the extent to which, additional staff resources are required to implement further improvements.

Direct DHS to Modify Formulary Regulations. Current DHS regulations require each DC and state hospital to establish its own drug formulary. This requirement duplicates the CDF and weakens the state's bargaining power for drug purchases. For this reason, we recommend that the Legislature direct DHS to amend its formulary regulations so that the hospitals operated by DMH and DDS would no longer be required to establish a separate staff committee and a separate drug formulary for each licensed facility. State regulations could be modified to allow the option of adopting a single department-wide formulary prepared by a single committee. Alternatively, departments could share the CDF.

Direct DDS, DMH, and DADP to Consider Modifying Reimbursement Systems. Due to limitations of their current billing systems, DDS, DMH, and DADP are not now taking advantage of the discounted drug prices that are available for their Medi-Cal patients. To remedy this situation, we recommend that the Legislature direct DDS and DMH to consider modifying their reimbursement systems to account separately for drug purchases for Medi-Cal patients in the DCs and state hospitals. (These modifications could occur when the departments implement other recent federally required changes to their systems.) The Legislature should also direct DADP to account separately for the medication costs of methadone services in its reimbursements for narcotics treatment clinics so that the state can obtain Medicaid prices and collect the rebates to which it is entitled from drug manufacturers. These changes would allow the state to take full advantage of the better prices available under Medi-Cal.

Our review found that the state has recently taken a number of steps to reduce overall prescription drug costs. In addition, we found that of the state's $4.2 billion in drug purchases, only about 10 percent, or $400 million, is affected primarily by the state's procurement and administrative operations. We found several deficiencies in those operations that the Legislature can correct. In general, the state can take better advantage of its bargaining power and improve its administrative operations. If these steps are taken, we estimate that the state could reduce prescription drug costs totaling tens of millions dollars annually.

| Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by Anna Brannen, Farra Bracht, Dan Carson, Kirk Feely, Shawn Martin, Celia Pedroza, Greg Jolivette, and Anthony Simbol, with assistance of a number of others in the office.. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814. |