April 27, 2006

State law establishes the Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC) and entrusts it with accrediting teacher preparation programs, credentialing teachers, and monitoring teacher conduct. In this report, we describe each of these three teacher-quality functions, identify related shortcomings, and propose various recommendations for overcoming them. The recommendations seek to simplify existing teacher-quality processes, reduce redundancies, strengthen accountability, and foster greater coherence among education reforms. Taken as a package, these recommendations would improve how the state ensures teacher quality and eliminate CTC.

All states have certain processes intended to address teacher quality. In California, state law establishes the Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC) and entrusts it with three specific teacher-quality processes: (1) accrediting teacher preparation programs, (2) credentialing teachers, and (3) monitoring teacher conduct. In this report, we examine how CTC currently undertakes these processes and identify ways to improve them. The nearby box summarizes our findings and recommendations.

Existing State Accreditation and Credentialing Systems Have Significant Shortcomings. During the last several years, concerns have been raised with almost every aspect of CTC’s operations-including its ability to perform its core functions effectively and efficiently. In this report, we identify several shortcomings with the state’s existing accreditation and credentialing systems. Most importantly, the existing accreditation process is too subjective and input-oriented and occurs too infrequently. In addition, the existing credentialing process is overly complex, inefficient, and riddled with redundancies. Most teachers, for example, have their initial credential application material reviewed three times (by their teacher preparation institution, county office of education (COE), and CTC) and are initially fingerprinted three times (by CTC, COE, and a school district).

Establish Performance-Based Accreditation System. Given the significant shortcomings with the state’s existing accreditation system, we recommend the Legislature establish a new performance-based accreditation system. This new state system would continue to supplement the required regional accreditation process and the optional national accreditation process. Under the new state system, teacher preparation programs in California would report annual summary data on various outcomes, including their average scores on state-required teacher assessments, graduation rates, employment rates, three-year retention rates, and employer satisfaction rates. Programs meeting minimum performance expectations would have their accreditation renewed. Programs not meeting one or more performance expectations would be placed under review and potentially provided support services. If they failed to improve within a few years, accreditation would be revoked. The California Department of Education (CDE) and State Board of Education (SBE) would work collaboratively to define minimum performance expectations, review and maintain data, and provide related support services.

Streamline and Devolve Credentialing Responsibilities. Given the significant shortcomings with the state’s existing credentialing system, we recommend the Legislature undertake major credentialing reform. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature simplify the requirements for, and types of, initial teaching credentials and then devolve credentialing responsibility to universities and COEs. We also recommend the Legislature retain county-level fingerprinting activities but eliminate CTC and districts’ fingerprinting activities. As a result of these reforms, teachers would have their credential application material reviewed only once rather than three times and would be initially fingerprinted only once rather than three times. While each existing safeguard would be retained, the associated administrative process would be streamlined and CTC would be removed from the process.

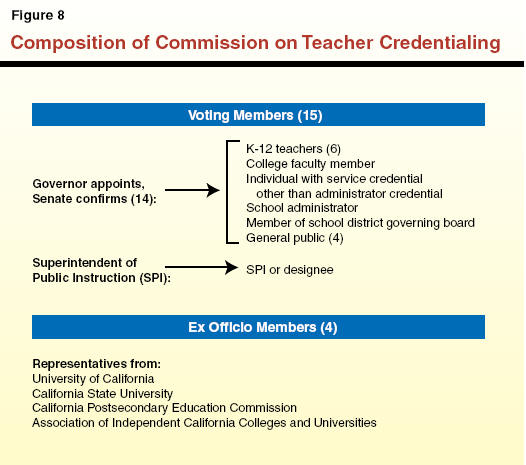

Replace Commission With Advisory Committee. In addition to concerns with CTC’s accreditation and credentialing systems, many groups have expressed concern with the governance structure of the commission. The existing commission is a statutorily authorized body consisting of 15 voting and 4 nonvoting members. The executive director of the commission is accountable only to the commission and does not report directly to the Governor. Moreover, the commission is not directly related to any of the other state education agencies. This existing governance structure has led to excessive regulation, blurred lines of accountability, and a lack of policy coherence. To overcome these problems, we recommend the Legislature replace the commission with an advisory committee that would make teacher-related recommendations to SBE. This would be the final step required to dissolve the entire existing structure of CTC.

|

Summary of LAO Findings and Recommendations |

|

|

Current System: |

New

System: |

|

Accreditation |

|

|

Accredits entire institution rather than each teacher preparation program. |

Accredits each teacher preparation program. |

|

Makes accreditation decisions once every five to seven years, with

no |

Makes accreditation decisions annually using readily available data. |

|

Decisions based on vague, subjective standards and input-oriented

|

Bases decisions on small number of program outcomes. |

|

Credentialing |

|

|

Is

extremely complex, labor |

Issues only initial credentials and only for broad categories of teachers and in broad subject areas. |

|

Requires universities, counties, |

Reviews credential applications one time at university or county

level |

|

Requires most teachers to be fingerprinted three times—at state, county, and district level. |

Fingerprints teachers one time |

|

Monitoring Teacher Conduct |

|

|

Involves a monitoring division within CTC, a Committee of Credentials, and the commission. |

Shifts monitoring functions to California Department of Education and State Board of Education (SBE). |

|

Relies on higher cost Attorney |

Relies on lower cost in-house counsel. |

|

Governance |

|

|

Has a commission that focuses |

Establishes advisory committee that would make recommendations on teacher issues to SBE. |

States have devised many ways to promote teacher quality. For example, they typically invest in an array of teacher preparation, recruitment, retention, and professional development programs. They also attempt to promote teacher quality by accrediting teacher preparation programs, credentialing teachers, requiring new teachers to complete a probationary period, and monitoring ongoing teacher conduct.

California promotes teacher quality in all these ways-funding various teacher programs and authorizing various teacher-quality processes. The state, for example, currently provides approximately half a billion dollars annually to fund about a dozen teacher-quality programs. In addition, state law establishes CTC and entrusts it with overseeing three teacher-quality processes: (1) accrediting teacher preparation institutions to ensure those institutions have met minimum standards; (2) credentialing teachers to ensure those individuals have met minimum training requirements; and (3) monitoring teacher conduct to ensure teachers conduct themselves appropriately. In this report, we assume the Legislature wants to retain these general teacher-quality efforts but improve how they are administered.

This report focuses specifically on the three teacher-quality processes administered by CTC. The agency is itself organized around these three processes. It has a division of: (1) Professional Services-which is responsible for accreditation; (2) Certification, Assignment, and Waivers-which is responsible for credentialing; and (3) Professional Practices-which is responsible for monitoring teacher conduct. These divisions are governed by a statutorily established commission that initiates various teacher policies and approves related regulations.

Figure 1 shows the number of positions and amount of spending associated with each of CTC’s divisions in 2005-06. In total, CTC has 152.5 personnel-years and is budgeted to spend $19 million on state operations. Although the state provided a one-time General Fund bail out to CTC in 2005-06, CTC’s state operation expenses typically are covered entirely from credential application fees and test fees.

|

Figure 1 Commission on Teacher

Credentialing |

||

|

2005-06 |

||

|

|

Personnel-Years |

Budgeted |

|

Division |

|

|

|

Certification, Assignment, and Waivers |

61.9 |

$7.7 |

|

Professional Services |

29.8 |

5.9 |

|

Professional Practices |

27.6 |

5.0 |

|

Distributed Administration |

33.2 |

— |

|

Totals |

152.5 |

$18.7 |

|

Funding Sources |

|

|

|

General Fund |

|

$2.7 |

|

Teacher Credentials Fund |

|

12.3 |

|

Test Development and Administration Account |

|

3.8 |

|

|

||

|

a The CTC also

received $32 million in General Fund monies for three local

assistance programs |

||

During the last several years, concerns have been raised with almost every aspect of CTC’s operations-including its ability to perform its core teacher-quality functions effectively and efficiently. Concerns also have emerged with the commission’s governance structure. The remainder of this report, consisting of four sections, discusses these concerns and makes recommendations for addressing them. The first three sections cover accreditation, credentialing, and monitoring teacher conduct, respectively. The fourth section focuses on the commission’s governance structure.

One of CTC’s core functions is to accredit teacher preparation programs. The primary purpose of accreditation is to ensure these programs are of sufficient quality. California has had a process for approving or accrediting teacher preparation programs since the 1960s. Its most recent accreditation system was established by Chapter 426, Statutes of 1993 (SB 655, Bergeson). This law directed CTC to adopt a new accreditation framework that included updated preparation standards. The standards CTC developed for the most common preparation programs (multiple-and single-subject programs) consist of 10 general preconditions, a set of additional preconditions that vary by program type, 8 common standards, 19 program standards, and 116 required program elements. The nearby box describes a few of these standards.

Teacher Preparation StandardsPreparation standards form the foundation of the state’s current accreditation system. The Commission on Teacher Credentialing publishes a 75-page handbook that describes these standards. Below, we provide a few examples of the common standards that apply to all teacher preparation programs as well as the program standards that apply to individual preparation programs. Common Standards. The eight common standards cover areas such as:

Program Standards. The 19 program standards cover areas such as:

|

State System Supplements Regional and National Systems. The state requires all institutions offering teacher preparation programs to be accredited by CTC. In addition to state accreditation, all California universities offering teacher preparation programs are required to be accredited by a regional accrediting body. Most of these are regionally accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges, though a few are accredited by the North Central Accrediting Association. In addition to required regional accreditation, some California institutions offering teacher preparation programs have opted to seek national accreditation. Currently, approximately one-quarter of California institutions are nationally accredited by the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education. These three accreditation systems (state, regional, and national) operate independently from one another, such that changes to the state system would not affect the regional or national accreditation systems.

The State Accreditation Process for Traditional Programs. For traditional fifth-year teacher preparation programs, the state has different accreditation processes for new and ongoing programs. For new programs, a panel of CTC staff or external experts reviews written proposals to determine if they meet established standards. For ongoing programs, institutions are assessed once every five to seven years based on a site visit conducted by an accreditation team of 2 to 15 members. These reviewers are drawn from a select pool of faculty members, K-12 teachers, and administrators known as the “Board of Institutional Reviewers.” During site visits, accreditation teams examine certain documents and interview various individuals.

The team then submits a recommendation to the Committee on Accreditation (COA), a 12-member statutorily authorized body that makes official accreditation decisions. The COA includes six representatives of higher education institutions and six representatives of K-12 education agencies. For each institution (and thereby all its teacher preparation programs), this committee may decide to, (1) accredit, (2) accredit with stipulations, or (3) deny accreditation. An institution has the right to appeal to the commission if either a decision by the COA or the procedures of an accreditation team are considered arbitrary, capricious, unfair, or contrary to the policies of the commission.

The State Accreditation Process for Internship Programs. The state uses the same basic process for accrediting university and district internship programs as it uses for accrediting traditional teacher preparation programs. For university and district internship programs, accreditation teams also conduct site visits consisting of document reviews and multiple interviews. As with traditional programs, these reviews occur every five to seven years. Although the accreditation process and underlying standards for the two types of preparation programs are the same, internship programs must meet some additional program requirements. For example, internship programs are subject to an additional, somewhat more elaborate supervised fieldwork requirement.

Results of the Most Recent Accreditation Cycle. From 1997 to 2002, most teacher preparation institutions in California had an accreditation review based on the current standards and framework. Over this period, accreditation teams visited 73 campuses. Approximately one-half of these institutions (36) received full accreditation. The remaining institutions also received accreditation but with either technical stipulations (17) or substantive stipulations (20) that had to be addressed within one year. No institution was denied accreditation.

Accreditation Activities Since 2002. Accreditation visits were suspended from spring 2003 through summer 2004. The CTC states that these visits were suspended partly because of budget cuts and partly because the entire accreditation system needed to be reexamined and refined. For the 2004-05 school year, accreditation teams resumed site visits but only to four campuses-all of which were seeking combined national/state accreditation. All four institutions received full accreditation. Although its accreditation of institutions with ongoing programs has been significantly scaled back, COA continues to accredit new programs. In 2004-05, it approved 133 new programs offered at 60 already accredited teacher preparation institutions. For example, San Diego State University was approved to offer a new bilingual specialist program and Stanislaus County Office of Education was approved to begin a mild/moderate disabilities district internship program.

Accredited Institutions. Currently, 95 institutions in California have accredited teacher preparation programs. At the University of California (UC), except for the newly opened campus in Merced, all other eight general campuses have accredited teacher preparation programs. At the California State University (CSU), except for the Maritime Academy, all other 22 campuses offer preparation programs. In addition, CSU offers CalState TEACH, a distance learning teacher preparation program. Many private institutions (53) also offer these programs-ranging from large programs at the University of Southern California and Stanford University to smaller programs at Occidental College and Whittier College. Figure 2 shows the number of students served and teachers prepared by UC, CSU, and private institutions. In addition, five COEs and six school districts offer accredited teacher internship programs.

Based on our review, we identify three major shortcomings with the state’s existing accreditation system. All three of these shortcomings also were highlighted in an independent, statutorily required evaluation of the state’s accreditation system. American Institutes for Research (AIR) conducted this evaluation over a three-year period (1999 to 2002) and released its final report in March 2003. Most of the shortcomings we discuss also have been highlighted in various other accreditation-related documents prepared by CTC over the last three years.

Standards Vague, Reviews Subjective. As indicated above, the current system relies on accreditation teams to decide whether institutions have met certain standards. The AIR evaluation found these standards to be vague. It also found the accreditation reviews to be subjective-with different review teams sometimes having different interpretations of the standards. Indeed, some institutional representatives believed their reviews would have been different if they had been conducted by different teams. The AIR evaluation found these problems were exacerbated by the difficulty of finding and retaining qualified reviewers.

System Almost Entirely Input-Oriented. The current system also is almost entirely input-oriented, which makes the site visit process particularly laborious. For example, in the most recent site visit of CSU, Los Angeles, the accreditation team reviewed 15 different types of documents-including the university catalog, course syllabi, fieldwork handbooks, information booklets, schedule of classes, advisement documents, faculty vitae, examinations, and student work samples. In addition, the accreditation team conducted 991 interviews-including interviews with faculty, administrators, candidates, graduates, employers of graduates, and advisors. Despite this elaborate review process, almost no data are obtained on program outcomes. Even CTC acknowledges this problem. In its 2003 “Proposal for Revision of the Commission’s Accreditation Policies and Procedures,” it noted that “little in the way of outcome data has been collected to determine institutional effectiveness.”

Basic Process Inadequate. The current state system also suffers from basic process problems.

Reviews Occur Too Infrequently. Accreditation reviews currently occur only once every five to seven years. Moreover, the state receives almost no information about changes in program quality that might occur between accreditation visits. In CTC’s 2003 revision proposal, it expressed concern both with the length of time between accreditation visits and the lack of ongoing program monitoring.

Process Focuses on Institutions Not Programs. The current system also accredits institutions for all the teacher preparation programs they offer rather than approving programs individually. Thus, even if some programs are weak, institutions are likely to receive state accreditation. (As mentioned above, no institution was denied accreditation in the last review cycle.) Under the state’s previous accreditation system, individual programs were evaluated and could be denied accreditation without adversely affecting other programs or the institution as a whole.

Quality of Information Varies Significantly. The AIR evaluation found that the quality of institutional information submitted to the accreditation teams varied significantly. Currently, various kinds of input-oriented information are provided in different formats, at different times, with different degrees of reliability. The AIR evaluation concluded that all these variations affect the validity of accreditation decisions.

We recommend the Legislature establish a new performance-based accreditation system. Under the new system, teacher preparation programs would report annual summary data on various outcomes, including their average scores on state-required teacher assessments, graduation rates, employment rates, three-year retention rates, and employer satisfaction rates.

A number of factors have recently converged that highlight the need for accreditation reform. As mentioned above, since 2002, most accreditation activities have been suspended. Formally recognizing this lull in accreditation activities, the Governor’s 2006-07 Budget includes a proposal to transfer four currently vacant positions in CTC’s accreditation division to its credentialing division. In addition, the state’s external accreditation evaluators, the commission, CTC staff, an Accreditation Working Group, and stakeholders in the field have dedicated a substantial part of the last several years to identifying problems with the current system and developing options for revising it.

Base New System on Program Performance. We recommend the Legislature repeal the existing accreditation system and enact legislation establishing a new performance-based system. Whereas the existing system is subjective, input-oriented, and sporadic, our recommended performance-based system would be objective, outcome-oriented, and ongoing. Under the new accreditation system, we recommend institutions be required to provide various outcome data on each teacher preparation program they offer (including internship programs). Specifically, we recommend programs report: (1) the average score of their students on each applicable state-required teacher assessment, (2) their graduation rates, (3) the percentage of each graduating cohort that obtains employment as K-12 teachers, (4) these teachers’ three-year retention rates, and (5) employers’ satisfaction ratings of these teachers. The new system also could evaluate programs according to how well they prepared teachers to help students meet the K-12 content and performance standards. Indeed, existing state law explicitly links teacher preparation to these K-12 standards. Once the California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System (better known as CALPADS) is operational, these data could be added to the accreditation system as another outcome measure.

Maintain Data as Part of State’s Teacher Information System. In the current year, the Legislature authorized CDE to contract for a teacher information system feasibility study report (FSR). Based on our conversations with the vendor preparing the FSR, we think a teacher information system could accommodate the types of outcome data we describe above. Thus, we think CDE (or the party ultimately entrusted with overseeing the entire teacher information system) also should be responsible for maintaining this subset of accreditation-related data.

Make Results Easily Accessible. We recommend the outcome data be provided annually in a consistent format and posted on the Web. This would allow the information to benefit prospective students, employers, policy makers, and the general public as well as help improve the programs themselves. To assist in making sense of the results, the system also could include growth measures and a similar-programs ranking (akin to a K-12 similar-schools ranking) that would control for the demographics and entering academic performance of each program’s students.

Annual Accreditation Decisions Would Be Data Driven. Under the new system, accreditation decisions would be made annually for each teacher preparation program using readily available data. The Legislature could authorize the Superintendent of Public Instruction (SPI), in concert with SBE, to establish minimum rates on the above outcome measures. Ongoing programs meeting the minimum standards would be automatically accredited whereas programs not meeting the minimum standards would be placed under review and potentially provided special support services. If the program did not demonstrate improvement within a few years, SBE would deny its accreditation. For new programs, proposals could be submitted to CDE and a review conducted similar to that of the existing CTC review process. If a program met minimum requirements, it could be initially approved and then, unlike the existing process, its performance could be monitored closely thereafter.

New System Would Redirect Some Costs but Likely to Result in Net Savings to State. For the last accreditation cycle, CTC estimates state-level accreditation activities cost approximately $835,000 annually. Of this amount, approximately $395,000 was spent on previsits, site visits, revisits, training for accreditation teams, and committee meetings. The remaining $440,000 was spent for CTC staff. Because CDE’s new data responsibilities would be less labor intensive than CTC’s current accreditation activities, we think CDE likely could cover annual staffing costs with less than is currently expended for CTC staff. Moreover, all other existing state-level accreditation expenses would be eliminated under the new system.

New System Likely to Reduce Local Costs. Cost impacts at the institutional level are more difficult to determine, but the AIR evaluation noted that institutions under the existing system face significant costs associated with administrator and faculty time spent preparing materials, developing a self-study document, preparing for site visits, creating document rooms for review teams, coordinating interviews, and navigating other logistics of the site visit process. Although we cannot estimate precisely, we think the data collection costs entailed in a new outcome-based accreditation system are likely to be less than these existing accreditation costs.

A second core function of CTC is to credential teachers. The primary purpose of credentialing is to ensure individual teachers are of sufficient quality. The state began issuing elementary school teaching certificates in 1893 and high school teaching certificates in 1901. Over time, the types of credentials and specific credentialing requirements have undergone periodic revision. The most recent significant revisions were a result of Chapter 548, Statutes of 1998 (SB 2042, Alpert). This legislation established a two-stage credentialing system in which individuals must first meet an initial set of requirements to obtain a preliminary credential. In basic terms, these requirements consist of demonstrating sufficient: (1) subject-matter knowledge in the area to be taught, (2) professional preparation, and (3) individual fitness (that is, having no record of serious criminal behavior). This credential is valid for a maximum of five years, during which time teachers need to complete various subsequent requirements in specific training areas-including advanced study in health education and computer technology as well as in teaching special student populations and English learners. After fulfilling these additional requirements, teachers obtain a professional credential. Thereafter, teachers must complete 150 hours of professional development every five years to renew their credential.

Current Credential Requirements. For preliminary and professional credentials, Chapter 548 specified requirements for the single subject credential (which applies to virtually all high school and some middle school teachers) as well as the multiple subject credential (which applies to virtually all elementary and some middle school teachers). These are the most common types of credentials. Figure 3 shows the current requirements for these credentials.

|

Figure 3 Current Requirements

for Single Subject and |

|

(For Teachers Prepared in California) |

|

|

|

Requirements for Preliminary Credential: |

|

·

Possess a baccalaureate or higher degree from a

regionally accredited |

|

· Complete a program from a Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC)-accredited teacher preparation institution. |

|

· Pass the California Basic Education Skills Test. |

|

· Pass the Reading Instruction Competency Assessment.a |

|

·

Complete a comprehensive reading instruction course

focusing on |

|

· Complete a course on the principles and provisions of the U.S. Constitution. |

|

· Demonstrate subject-matter knowledge.b |

|

· Complete introductory computer technology course. |

|

Requirements for Professional Credential: |

|

·

Complete a CTC-approved teacher induction program,

which must include |

|

|

|

a Requirement applies only to the multiple subject credential. |

|

b For single subject credential, individual may fulfill requirement either by passing subject-matter test or completing CTC-approved subject-matter program. For multiple subject credential, individual must pass subject-matter test to fulfill requirement. |

Basic Types of Credentials and Permits. In addition to single subject and multiple subject credentials, CTC issues myriad other types of licensing documents. As listed in Figure 4, CTC currently issues 55 basic types of documents, including 32 types of teaching credentials/certificates/permits, 8 different emergency permits, 8 service credentials/permits, 6 child development permits, and waivers. Within each of these categories, CTC issues preliminary, professional, and renewal documents. Within each category, CTC also issues many different types of authorizations. (We discuss authorizations in more detail in the next section.) In addition, CTC issues a “Certificate of Clearance” to individuals prior to their student teaching, and it renews (but no longer initially issues) 94 now outdated licensing documents.

|

Figure 4 CTC Currently Issues 55 Basic Types of Licensing Documents |

|

|

(As of October 5, 2005) |

|

|

|

|

|

Teaching Credentials (20): |

Emergency Teacher Permits (8): |

|

Multiple Subject |

Single Subject |

|

Single Subject |

Multiple Subject |

|

Education Specialist Instruction |

Education Specialist Instruction |

|

Designated Subjects Adult Education, Part-Time |

Bilingual, Cross-Cultural, Language, and

Academic |

|

Designated Subjects Adult Education, Full-Time |

|

|

Designated Subjects Special Subjects |

Cross-Cultural, Language, and Academic Development |

|

Designated Subjects Supervision and Coordination |

30 Day Substitute Designated Subjects

Vocational |

|

Designated Subjects Vocational Education, Part-Time |

|

|

Designated Subjects Vocational Education, Full-Time |

Career Substitute |

|

District Intern |

Resource Specialist |

|

Eminence |

Service Credentials/Permits (8): |

|

Exchange Certificated Employee |

Administrative Services |

|

Sojourn Certificated Employee |

Clinical/Rehabilitative Services |

|

Specialist Instruction in: |

Emergency Library Media Teacher |

|

Agriculture |

Exchange Certificated Employee Services |

|

Bilingual Cross-Cultural Education |

Health Services |

|

Early Childhood Education |

Library Media Teacher |

|

Gifted Education |

Pupil Personnel |

|

Health Science |

School Nurse |

|

Mathematics |

Child Development Permits (6): |

|

Reading Education |

Assistant |

|

Teaching Certificates (8): |

Associate |

|

Bilingual, Cross-Cultural, Language, and

Academic |

Teacher |

|

Master Teacher |

|

|

Cross-Cultural, Language, and Academic Development |

Site Supervisor |

|

Completion of Staff Development |

Program Director |

|

Early Childhood Special Education |

Waivers |

|

Individualized Internship |

|

|

Pre-Intern |

|

|

Reading |

|

|

Resources Specialist Certificate of Competence |

|

|

Teaching Permits (4): |

|

|

Limited Assignment Multiple Subject |

|

|

Limited Assignment Single Subject |

|

|

Provisional Internship |

|

|

Short-Term Staff |

|

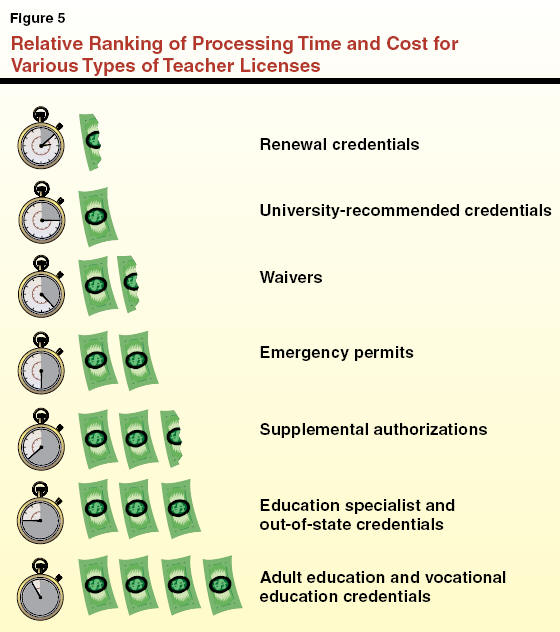

Application Workload and Processing Time. In 2004-05, CTC processed more than 250,000 applications for licensing documents. Although a regulatory provision requires CTC to process these applications within 75 working days of their receipt, CTC’s average processing time is currently approximately 110 working days. As shown in Figure 5, processing time varies significantly for different types of credentials. Whereas renewal documents, which have very simple requirements, take the least time to process, credentials with more elaborate requirements, such as out-of-state and vocational education credentials, take notably longer to process.

Credential Application Fees. In addition to education fees for subject matter and teacher preparation programs and fees for state-required tests, teachers also pay credential application fees. Currently, student-teachers pay $27.50 for a Certificate of Clearance. This amount becomes a credit they can apply toward a future credential. For all other licensing documents, CTC has a uniform application fee of $55. Individuals pay this fee each time they submit an application for a new credential, permit, authorization, or specialization. In 2005-06, CTC expects to collect $12.1 million in teacher credential fees.

Fingerprinting Fees. In addition to these application fees, teachers pay fingerprint fees at the time they apply for their Certificate of Clearance. They pay a $32 fee to the Department of Justice (DOJ) and a $24 fee to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. At the local fingerprinting site, teachers also are assessed a “Live Scan Service Fee,” which ranges from $12 to $25. This fee is retained at the local site to cover local operation costs. As described below, in addition to being fingerprinted prior to student teaching, teachers often are fingerprinted at the county and school district level. Teachers pay the above three fees each time they are fingerprinted.

We think the current credentialing system has three major shortcomings. It is: (1) overly complex (from the perspectives of both the state and teachers), (2) inefficient (being both labor intensive and time consuming), and (3) riddled with redundancies (both in the credential review and fingerprinting process).

Dizzying Array of Documents. Legislation passed in 1993 required CTC to “reduce and streamline the credential system” and allow “greater flexibility in staffing local schools.” Despite this directive, the current credential system is a virtual labyrinth. Below, we provide examples of this complexity for just a few of the many types of credentials that exist.

Single Subject Credential. For this credential, CTC issues 21 different authorizations (in areas such as art, English, chemistry, and physics); 63 different supplementary authorizations (in areas such as anthropology, chemistry, journalism, and ornamental horticulture); and 26 different subject matter authorizations (in areas such as art history, English composition, chemistry, and three-dimensional art). Some subjects (such as chemistry) appear on all three authorization lists.

Vocational Education and Adult Education Credentials. The vocational education credential is issued for 173 different subjects, including bicycle repair, fashion design, roofing, and tow truck operation. The adult education credential is issued for 71 different subjects, including arts and crafts, food preparation, public affairs, and marine technology.

Child Development and Education Specialist Credentials. The child development permit is issued for six levels, ranging from assistant to program director, and the education specialist credential is issued in six areas of specialization, including mild/moderate disabilities and visual impairments.

For each of the above authorizations, levels, and specializations, CTC has unique requirements. Moreover, it requires a separate application and $55 fee every time something new is added to an existing credential or an existing credential is renewed.

Teachers Face Credential Labyrinth. Teachers are directly affected by the complexity of the existing credential system. Teachers not only need to meet many requirements to obtain their preliminary and professional credentials, but they need to meet various requirements to receive authorization to teach specific subjects. As an example, suppose a student graduated from a teacher preparation program, paid a $55 application fee, received a single subject credential in Geosciences, and began teaching courses in Geosciences. Depending on the current policies of CTC and the local governing board, this individual could be counted as misassigned if he or she taught Geography or an introductory science course. In a few years, after completing various requirements, this individual could submit a second application to CTC, pay another $55 fee, and receive a supplementary authorization to teach Geography. A few years later, after completing various other requirements, this individual could submit a third application to CTC, pay a $55 fee for the third time, and receive a subject matter authorization to teach introductory science. This same multistep process holds for hundreds of other types of possible subject matter combinations.

Labyrinth Results in Labor-Intensive and Time-Consuming Application Process. Given the complexity of the requirements for many types of credentials and authorizations, reviewing applications can be labor intensive and time consuming. Currently, the Certification, Assignment, and Waivers division within CTC has 62 staff and a budget of $8.4 million, the bulk of which is for reviewing credential applications. Despite (1) repeated processing-related concerns expressed by the Legislature, (2) development and implementation of a new information technology system intended to reduce processing time, and (3) various independent state-authorized reports focused on credential processing (by MGT of America in 2000, our office in 2002, and the Bureau of State Audits in 2004, 2005, and 2006), processing time is significantly slower today than in 2000. In 2000-01, credentials, on average, took 65 days to process. In the third quarter of 2005, average processing time exceeded 110 days for virtually all types of credentials. For example, during the month of September (2005), CTC took an average of 116 days to process renewal and university-recommended credentials, which require almost no substantive review. Even with the Governor’s budget proposal to establish seven new positions within the credentialing division, average processing time is expected to be about 100 days. (The CTC attributes the longer processing time to staffing reductions and lack of familiarity with the new information technology system.)

Credential Review Process Riddled With Redundancies. When students complete a teacher preparation program, the university’s credential analysts work with them to compile appropriate credential materials and ensure their application packets are complete and accurate. The university then officially recommends students for their credentials and transfers application materials to CTC. Although CTC states that it does only a cursory review of applications coming from universities-in recognition of them already having been evaluated by the university-average processing time for these types of credentials, as noted above, is running 116 days.

Counties Have Devised Own Licensing System Because University/State Licensing System Too Slow. Because of the long processing delay from the universities’ initial review to CTC’s final approval or denial, counties have devised an entirely separate, but substantively similar, licensing process. In the absence of an official state document, counties issue “temporary county certificates.” Authorized in state law, these temporary certificates allow teachers to work for up to a year without an official CTC document. To issue these certificates, counties, however, must be relatively sure a particular individual is qualified and eventually will be issued a CTC credential. They therefore have their own credential analysts who do their own review of credential material. This practice of issuing temporary county certificates is very common. Representatives from the King, Orange, and San Diego COEs, for example, report that they review and issue temporary certificates for the vast majority of teachers seeking to renew their credentials as well as the vast majority of teachers coming from in-state universities and from out of state.

Fingerprinting Riddled With Redundancies-Process Begins at CTC. As with the credential review process, the fingerprinting process for teachers is riddled with redundancies. Many teachers are fingerprinted three times to obtain their first teaching job. Individuals are first fingerprinted prior to student teaching. These student-teachers often are fingerprinted at their teacher preparation institution. (For example, all CSU campuses provide Live Scan services.) As part of this process, DOJ files their fingerprints, does a background check, and then notifies CTC if the individual receives clearance (has no criminal record) and may begin student teaching. The individual’s fingerprints are then on record with DOJ for life or until CTC removes them, and CTC thereafter receives all subsequent arrest notifications.

Counties Repeat the Process. Just as CTC requires a background check for purposes of issuing credentials, counties require a background check for purposes of issuing temporary certificates. As mentioned above, counties issue temporary certificates for the bulk of teachers. Thus, in most instances, teachers must complete the same fingerprinting process for the county as for CTC. In many instances, individuals will already have DOJ clearance, but now the counties will receive all subsequent arrest notifications directly.

Districts Also Repeat the Process. Whereas CTC must fingerprint for official credentials and counties fingerprint for temporary certificates, school districts fingerprint for employment purposes. Thus, teachers complete the same fingerprinting process at the district level as they have at the county and state level. As with the county process, in many instances, individuals will already have DOJ clearance, but now the applicable school district will receive all subsequent arrest notifications directly. If teachers subsequently change districts, they are fingerprinted for employment at the new district (and at every new district thereafter).

We recommend the Legislature undertake major credential reform by reducing the types of credential documents issued, simplifying associated credential requirements, and then devolving credentialing responsibility to universities and COEs. We also recommend the Legislature retain county-level fingerprinting activities but eliminate CTC and districts’ fingerprinting activities.

Given the shortcomings of the existing credentialing system, we recommend the Legislature undertake major credentialing reform to simplify and streamline the system. Under our proposed system, credential requirements would remain but be reduced in number; the basic licensing function would remain but be completed once rather than three times; and, the fingerprinting process would remain, but it too would be completed only once rather than three times. These reforms would preserve the intent of the existing credentialing system while eliminating its redundancies. In the end, teacher candidates, teachers, the public, and policy makers would have a system that was much easier to understand and navigate.

Begin by Simplifying Credential Requirements and Credential Types. As indicated above, the basic intent of credentialing is to ensure that teachers, particularly beginning teachers who have little teaching experience, are of sufficient quality. Over time, however, so many credential requirements, authorizations, specializations, and levels have been created that CTC now appears to regulate every class a teacher may teach during every year of their career. This is clearly contrary to expressed legislative intent to streamline the system.

We recommend the Legislature authorize preliminary credentials for broad categories of teachers (such as multiple subject, single subject, special education, adult education, and vocational education) and in broad subject areas (such as English, Social Science, Math, and Science). We further recommend the Legislature fund support programs for first- and second-year teachers (as currently required for professional credentials) but eliminate much of the remainder of the existing credentialing system-including the issuance of professional credentials, renewal credentials, and supplemental/subject matter authorizations. Although we think CDE and SBE should be allowed some discretion in establishing specific credential types, we recommend the Legislature statutorily limit the number of different teacher documents to no more than a few dozen.

Instead of the highly bureaucratic process that now accompanies the teaching of any class outside a teacher’s preliminary credential, we think teachers could work locally with other teachers, mentor teachers, coaches, and/or principals to structure professional development plans that would allow them to become expert in related subject areas and compile professional portfolios. These portfolios could include additional coursework, advanced degrees, participation in professional development programs, and service as a mentor teacher as well as any other type of related training. The portfolios would be taken with teachers from school to school and district to district, similar to other professionals who take their work experience and skills with them when they change employers.

Devolve Most Credentialing Responsibility to Universities. As discussed above, one of the major shortcomings of the existing system is the redundancy of the credential review process. Rather than having universities, CTC, and COEs all review credential application material, we recommend the review process be done only once for each teacher. Specifically, for individuals coming from accredited teacher preparation institutions in California, we recommend those institutions do what they now do and review their students’ transcripts and related material to ensure they have met the requirements for the credential they seek. If a student meets the requirements, we recommend the university simply issue a credential document that states the student has met the requirements. This would eliminate the need for the university to make a recommendation and forward credential material to CTC. (Currently, CTC does no subsequent substantive review of the application material.) Although universities already are covering credential review costs without charging explicit credential fees, the Legislature could allow universities to charge small fees to cover their costs for preparing and printing credential documents (as universities do for student transcripts).

Devolve Remaining Credentialing Responsibility to COEs. For individuals coming from out of state, we recommend COEs continue to do what they essentially now do and review these applicants’ credential material to determine if they meet the requirements associated with that credential. We recommend the Legislature allow counties to charge these applicants the full cost of the associated review process (as is common practice in other states). Given the simplifications suggested above, however, this review should not be as labor intensive as it now is, which should lower processing costs. The county office would then issue a document that states the individual has met the credential requirements. This would replace the existing process whereby the county issues a temporary county certificate for these individuals as they await receipt of their official CTC credential. County offices also could issue licenses for substitute teachers, similar to the reviews they currently do. County office representatives state that licenses for substitute teachers are relatively easy to review because the requirements are relatively simple.

Fingerprint Teachers Once at County Level. We recommend the Legislature retain county-level fingerprinting services but eliminate CTC and district’s fingerprinting activities. Under the new system, a COE would provide fingerprinting services on behalf of all school districts within that county and inform those districts of any arrest notifications. Although a few county offices already form voluntary consortia with their districts and conduct fingerprinting and related services on their behalf, we recommend legislation be enacted that would extend this streamlined fingerprinting process to all counties. The obvious benefit of such a streamlined system is that teachers would be initially fingerprinted only once and then could move among districts within the county without having to be fingerprinted again. Children, however, would be just as protected in the new system as in the existing system because all teachers still would be fingerprinted and required to receive DOJ clearance.

Another of CTC’s core functions is to protect children by ensuring individuals with records of serious or violent crime are not hired as teachers and teachers’ behavior in the classroom is appropriate. To this end, CTC reviews the criminal records of credential applicants as well as investigates any arrests, allegations, or complaints involving existing teachers. Within CTC, the Division of Professional Practices is responsible for conducting these investigations. Currently, this division has 28 staff and a budget of $5 million. This division is financed with revenue generated from application and exam fees. It reports to a statutorily created Committee of Credentials. This seven-member committee consists of an elementary school teacher, secondary school teacher, school administrator, member of a local school governing board, and three representatives of the general public. Unlike the Committee on Accreditation, which can make final accreditation decisions, this committee is authorized only to make recommendations to the commission. The commission then makes final credential and discipline decisions.

The Monitoring Process. Investigations are undertaken when: (1) DOJ identifies a criminal record for a new credential applicant, (2) CTC receives an arrest or conviction report for an existing teacher, and (3) affidavits are filed or reports are issued from school districts lodging complaints against an existing teacher. The CTC’s legal division conducts approximately 2,000 investigations annually. After legal staff have completed an investigation, the Committee of Credentials makes a recommendation either to close the case or take disciplinary action. If the committee recommends disciplinary action, the teacher may request reconsideration (if relevant information not previously reviewed is presented) or an administrative hearing. The teacher has 30 days to exercise one of these options before the committee’s recommendation is submitted to the commission for final action.

The Hearing Process. If a teacher requests an administrative hearing, the case could be settled prior to the hearing by CTC’s legal staff. If CTC staff cannot settle the case, it is transferred to the Office of the Attorney General (AG), which also reviews whether settlement is appropriate. If the case is settled, the Committee of Credentials reviews the negotiated terms and then submits them to the commission for final adoption.

If a case goes to the administrative hearing stage, it must be prepared by AG staff. Unlike several other state agencies (including CDE, UC, and CSU), CTC does not have a statutory exemption allowing it to use in-house legal counsel for these hearings. The hearing itself is conducted before an administrative law judge and, upon completion, a proposed decision is sent to the commission, which can accept or reject that decision. If the commission rejects the decision, it issues a separate decision based on its own findings.

In 2004-05, the commission approved a total of 71 settlements-54 of which were settled by CTC staff and 17 that were settled after the case had been transferred to the AG. During 2004-05, six administrative hearings were held, and three cases defaulted (meaning the AG initiated the hearing process but the applicant/teacher did not file a notice of defense in the time allowed, so the disciplinary action recommended by the Committee of Credentials was adopted by default).

Disciplinary Actions. If a case is not initially closed, then the commission may ultimately decide to take any of a number of disciplinary actions. As authorized in statute, action may be taken to: (1) deny a credential application or revoke an existing credential, (2) suspend a credential, (3) issue a public reprimand, or (4) issue a private admonition. The commission also may place a teacher on probation as a term of settlement. Similarly, an administrative hearing officer can issue a decision recommending that a teacher be placed on probation. Figure 6 shows the frequency of each of these possible actions, and Figure 7 lists some common causes for each type of action. Disciplinary action is very rare-affecting less than .05 percent of credential applicants and approximately .1 percent of credential holders.

|

Figure 6 Frequency of Disciplinary Actions |

|||

|

Number of Cases |

|||

|

Disciplinary Action: |

2001-02 |

2002-03 |

2003-04 |

|

Credentials revoked |

157 |

217 |

227 |

|

Credential applications denied |

102 |

109 |

104 |

|

Credentials suspended |

77 |

67 |

95 |

|

Public reprimands |

41 |

52 |

56 |

|

Private admonitions |

11 |

25 |

10 |

|

New probation casesa |

4 |

26 |

33 |

|

Totals |

392 |

496 |

525 |

|

|

|||

|

a Action may be (1)

taken as a term of settlement or (2) recommended by an

administrative hearing |

|||

|

Figure 7 Common Causes of Disciplinary Actions |

|

Common Reasons Individuals Would: |

|

Have Their Credential Application Denied or Credential Revoked: |

|

· Conviction of serious or multiple crimes. |

|

· Sex with a student. |

|

· Repeated verbal or physical abuse of students. |

|

Have Their Credential Suspended: |

|

· Internet pornography. |

|

· Major alcohol-related incidence. |

|

· Contract abandonment. |

|

Receive a Public Reprimand: |

|

· Domestic violence. |

|

· Minor misconduct at school with mitigating circumstances. |

|

· Minor alcohol-related incidence. |

|

Receive a Private Admonition: |

|

· Minor criminal convictions. |

|

· Minor mistreatment of students. |

|

· Minor insubordination. |

|

Be Placed on Probation: |

|

· Substance abuse. |

|

· Sexual harassment. |

|

· Anger management issues. |

We recommend the Legislature retain existing monitoring functions but shift responsibility for them to CDE and SBE. We further recommend that CDE use in-house legal counsel, which likely would cut costs for administrative hearings by more than one-half. Lastly, we recommend covering monitoring activities using exam fee revenue (largely consistent with current practice).

Unlike accreditation and credentialing, we recommend the Legislature essentially retain the existing monitoring system. We recommend a few modifications, however, that would streamline associated administrative processes and cut costs.

Modify Administration of Monitoring Functions. Specifically, we recommend two administrative changes. First, we recommend shifting CTC’s existing legal functions to CDE. This shift is largely intended to conform to our other recommendations, which result in the elimination of direct CTC services. Second, we recommend eliminating the Committee of Credentials’ review and recommendation process as well as the commission’s final decision-making process. These processes would be replaced with a streamlined process in which CDE legal staff would make recommendations directly to SBE for action. This CDE/SBE process is commonly used for review and action on a variety of education issues (such as for district waiver requests and charter school appeals).

Reduce Cost of Administrative Hearings. Additionally, we recommend CDE use in-house counsel rather than AG counsel for administrative hearings. As mentioned above, CDE, unlike CTC, already has an exemption from using AG counsel. Based on estimates from a recent legislatively required report, CDE likely would need to hire two additional counsel and two additional analyst positions if workload were shifted from the AG. Using in-house staff, however, likely would cut costs by more than one-half (from $1.1 million using the AG to $432,000). Moreover, we think CDE in-house counsel likely has the expertise to handle credential-related cases given their relatively routine and education-specific nature. Based on the recent legislatively required report, the associated transition process likely could be completed within two months.

Fund Monitoring Activities With Test Fee Revenue. As discussed above, CTC’s legal functions typically are financed using application and test fee revenue. Under our other recommendations, CTC no longer would be collecting credential application revenue, as credentialing functions would have been devolved. Test fee revenue alone, however, likely could cover most, if not all, monitoring costs. If CDE achieved the expected savings from using in-house counsel and even very modest savings from the streamlined administrative process, the $4.2 million expected to be collected in exam fee revenue in 2006-07 likely would be sufficient to cover all associated monitoring costs. Currently, the test fee account also has a substantial reserve. This reserve could help ease the transition if the projected cost savings were not achieved as quickly or as fully as expected.

The above sections examine CTC’s core functions. In those sections, we recommend streamlining certain sets of activities and then, for remaining activities, either devolving or shifting them to other existing state and local education agencies. Given CTC’s operational responsibilities would be reassigned under our package of recommendations, the agency no longer would be needed and the role of the commission would need to be reconsidered. In this final section, we focus on governance issues relating to the structure and function of the commission itself.

An Independent Commission. The existing commission is an independent, statutorily authorized body. Figure 8 shows the composition of the commission. As shown, the commission has 15 voting and 4 nonvoting members. Unlike many other state agencies, the executive director of the commission is accountable only to the commission and does not report directly to the Governor. The commission initiates teacher-related policies and approves teacher-related regulations.

Having an independent commission focused almost exclusively on teacher issues has generated concern among many groups for many years. For example, governance-related concerns were highlighted in our 1999 report, A K-12 Master Plan, as well as in the 2004 report by the California Performance Review. In addition, in 2003, both an Assembly bill (AB 791, Pavley) and a report requested by the Assembly Budget Subcommittee on Education Finance focused on merging CTC with CDE. Through these and various other venues, groups have raised three major concerns with the commission. Specifically, the existing governance structure has been linked to: (1) excessive regulation, (2) blurred lines of accountability, and (3) a lack of policy coherence. Below, we discuss each of these concerns.

Excessive Regulation. Although state law authorizes the basic accreditation and credentialing processes, teacher regulation in these areas, as illustrated repeatedly in the above sections, has become extremely complex. For example, in the accreditation section, we note the elaborate process CTC uses to conduct a site visit-reviewing dozens of different types of documents and conducting hundreds of interviews. Similarly, in the credentialing section, we note that the single subject credential is now associated with 21 different authorizations, 63 supplementary authorizations, and 23 subject matter authorizations. Not required to report directly to any other group, having few external constraints, and operating outside the broader context of K-12 education, the existing commission has an inherent tendency toward excessive complexity, specialization, and regulation.

Blurred Lines of Accountability. The commission operates independently both from higher education agencies and from SBE, SPI, and the Office of the Secretary for Education (OSE). Indeed, as we discuss in our 1999 A K-12 Master Plan report, K-12 governance in California is especially fragmented. In the realm of teacher issues, governance is even more fragmented-with the state board, superintendent, secretary, and commission all having some influence in some policy areas, many of which are overlapping. Given all these competing agencies, identifying and maintaining accountability is particularly difficult. For example, the state has had various problems implementing the teacher provisions of the No Child Left Behind Act (including a lawsuit involving a new teacher license). Given CTC, CDE, SBE, and OSE all have been involved in these implementation issues, the Legislature cannot easily discern who is responsible for such problems.

Lack of Policy Coherence. The competition among so many education agencies, each with some policy control, results not only in blurred lines of accountability but also in a kaleidoscope of policy initiatives. An independent commission has little incentive to ensure its policy initiatives are purposefully aligned with other executive branch education initiatives or well integrated into broader education reforms. For example, CTC often proposes changes to credentialing requirements without demonstrating that the changes are well aligned with the needs and capabilities of school districts, COEs, teacher preparation institutions, and other state education agencies. This lack of policy coordination and coherence also results because other state agencies can initiate reforms without considering their effect on CTC’s policies. For example, SBE and COEs recently have advocated specific approaches to professional development (including the use of teacher coaches) without considering if any related changes should be made to teachers’ credential renewal requirements (which are based entirely on professional development).

We recommend the Legislature replace the commission with an advisory committee that would make teacher-related recommendations to SBE.

Under our recommended package of reforms, the final step involved in dissolving the entire existing structure of CTC would be to eliminate the commission itself and replace it with an advisory committee that reported to SBE. A special teacher-focused advisory committee would retain the basic benefit of the existing governance structure-a knowledgeable body focused on teacher issues in California. By stripping it of independent authority, it would, however, not have the negative repercussions of the existing governance structure.

Overcomes Perverse Incentives Inherent in Existing Governance Structure. Having the new committee serve only in an advisory capacity to SBE would help overcome the shortcomings of the existing governance structure. It would reduce tendencies toward excessive regulation because it would report to a body that is responsible for a broad array of education issues-ranging from teachers to school accountability, instructional materials, federal programs, charter schools, and child nutrition. With so many competing priorities, SBE would be at least somewhat less likely to develop teacher regulations that were as complex and specialized as existing teacher regulations. Eliminating the commission also would reduce at least one of the many agencies that currently vie for K-12 policy control. As a result, the state would achieve clearer lines of accountability and be better able to detect the sources of problems and correct for them. Lastly, policy coherence would be improved because no independent teacher body would be pronouncing new policy initiatives potentially disconnected from other education priorities.

Advisory Committees Common in Other States. Having a teacher-focused advisory committee that reports to a state board is relatively common among states. As shown in Figure 9, 25 states currently have this type of advisory committee. By comparison, 15 states (including California) have autonomous teacher commissions, 6 have semi-autonomous/semi-advisory boards, and 4 have no separate teacher commission.

|

Figure 9 Advisory Teacher

Committee Most Common |

|||

|

Independent |

Semi-Autonomous/ Semi-Advisory Commission (6) |

Advisory |

No

Teacher |

|

Alaska |

Alabama |

Arkansas |

Arizona |

|

California |

Colorado |

Connecticut |

Maine |

|

Delaware |

Florida |

Idaho |

Michigan |

|

Georgia |

Maryland |

Illinois |

Ohio |

|

Hawaii |

South Dakota |

Kansas |

|

|

Indiana |

Texas |

Louisiana |

|

|

Iowa |

|

Massachusetts |

|

|

Kentucky |

|

Mississippi |

|

|

Minnesota |

|

Missouri |

|

|

Nevada |

|

Montana |

|

|

North Dakota |

|

Nebraska |

|

|

Oklahoma |

|

New Hampshire |

|

|

Oregon |

|

New Jersey |

|

|

West Virginia |

|

New Mexico |

|

|

Wyoming |

|

New York |

|

|

|

|

North Carolina |

|

|

|

|

Pennsylvania |

|

|

|

|

Rhode Island |

|

|

|

|

South Carolina |

|

|

|

|

Tennessee |

|

|

|

|

Utah |

|

|

|

|

Vermont |

|

|

|

|

Washington |

|

|

|

|

Wisconsin |

|

In this report, we identify numerous shortcomings with the state’s existing processes for accrediting teacher preparation institutions, credentialing teachers, monitoring teacher behavior, and developing teacher-related policy. Together, these shortcomings result in an overarching system that is extremely complicated and nuanced, inefficient and riddled with redundancies, poorly integrated and largely unaccountable. We summarize these shortcomings in Figure 10.

|

Figure 10 Summary of LAO Findings and Recommendations |

|

|

Current System: |

New

System: |

|

Accreditation |

|

|

Accredits entire institution rather than each teacher preparation program. |

Accredits each teacher preparation program. |

|

Makes accreditation decisions once every five to seven years, with

no |

Makes accreditation decisions annually using readily available data. |

|

Decisions based on vague, subjective standards and input-oriented

|

Bases decisions on small number of program outcomes. |

|

Credentialing |

|

|

Is

extremely complex, labor |

Issues only initial credentials and only for broad categories of teachers and in broad subject areas. |

|

Requires universities, counties, |

Reviews credential applications one time at university or county

level |

|

Requires most teachers to be fingerprinted three times—at state, county, and district level. |

Fingerprints teachers one time |

|

Monitoring Teacher Conduct |

|

|

Involves a monitoring division within CTC, a Committee of Credentials, and the commission. |

Shifts monitoring functions to California Department of Education and State Board of Education (SBE). |

|

Relies on higher cost Attorney |

Relies on lower cost in-house counsel. |

|

Governance |

|

|

Has a commission that focuses |

Establishes advisory committee that would make recommendations on teacher issues to SBE. |

To combat existing problems, we recommend various reforms (also listed in Figure 10), which could be pursued individually or as a package. The reforms streamline some functions, devolve some functions to local-level agencies, and shift some functions to other existing state agencies. Taken together, the reforms would eliminate the role of CTC. They also would greatly simplify the existing system, reduce redundancies, strengthen accountability, and better align future teacher reforms with other education reforms.

|

Acknowledgments This report was prepared by Jennifer Kuhn and reviewed by Robert Manwaring. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814. |