January 2006

Amid growing concerns with the organizational relationship between the Student Aid Commission and EdFund, the Legislature directed our office to identify the range of organizational options available for administering federal student loan programs. This report describes various options and then assesses them in terms of their ability to reduce tension among organizational leadership, clarify certain roles and responsibilities, and promote incentives that reward high-quality service to students.

The Supplemental Report of the 2005 Budget Act directs the Legislative Analyst’s Office to identify “the range of structural options available to the Legislature for providing the state with access to federally guaranteed student loan services,” giving special focus to the organizational arrangements used by other states. The language explicitly precludes us from recommending adoption of any particular organizational arrangement. Given this directive, in this report, we: (1) describe how states administer the Federal Family Education Loan Program (FFELP), (2) discuss the shortcomings of California’s existing organizational arrangement for administering FFELP, and (3) identify the range of organizational options available for administering FFELP.

The federal government offers various types of loans to help students cover college costs. The four major types of federal student loans are: (1) subsidized Stafford Loans, (2) unsubsidized Stafford Loans, (3) Parent Loans for Undergraduate Students (PLUS), and (4) consolidation loans. Whereas subsidized loans are designed for financially needy students, unsubsidized loans are designed for nonneedy students. For subsidized loans, the federal government pays the interest costs while students are enrolled, for the first six months after students leave school, and during deferment periods. For unsubsidized loans, the federal government does not pay any of the associated interest costs. The amount students can receive in federal loans is capped annually. For example, juniors in college who are dependent on their parents currently may receive a maximum of $5,500 in federal student loans whereas graduate students may receive a maximum of $8,500 annually.

These federal loans are administered via two student loan programs-FFELP and the William D. Ford Direct Loan Program. The FFELP evolved from a federally guaranteed student loan program originally established in the Higher Education Act of 1965, whereas the direct loan program was authorized by the federal Student Loan Reform Act of 1993. In federal fiscal year 2003-04, the federal government underwrote $84 billion in student loans. Of this amount, $65 billion, or 77 percent, was for FFELP loans whereas $19 billion, or 23 percent, was for direct loans.

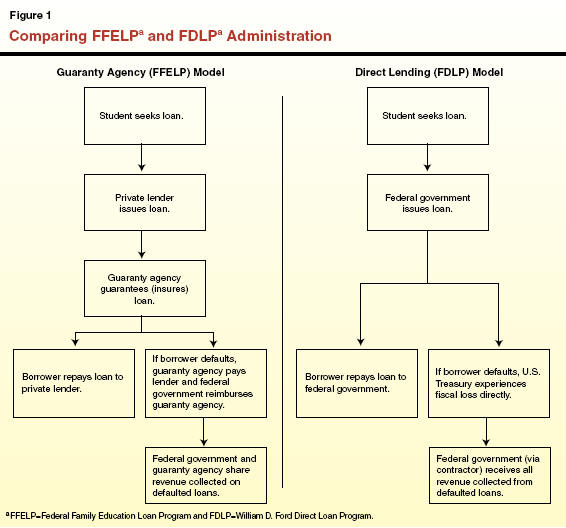

As shown in Figure 1, the major difference between FFELP and the direct loan program is in how the federal government finances and administers them. Administration of FFELP is decentralized-relying on private lenders and state guaranty agencies to operate the program for the federal government. By comparison, administration of the direct loan program is centralized-colleges work directly with the federal government and loans are funded directly from the U.S. Treasury. Colleges themselves select which program to use, though they can participate in both programs as long as no student receives a loan from both programs for the same enrollment period. Because state-level agencies have no role in the direct loan program whereas states must have a designated guaranty agency that administers FFELP, the remainder of this report focuses only on FFELP.

Under FFELP, private lenders, such as banks, fund the student loans. The federal government guarantees repayment to these lenders if borrowers default. The federal government relies on state guaranty agencies to process the guarantee and perform related administrative functions. Each state has a designated guaranty agency that issues guarantees to lenders, works with lenders and borrowers to prevent loan defaults, and collects on loans after default. Colleges, however, are not required to use their state’s designated guaranty agency. Instead, they may use any guaranty agency in the country.

Thirty Five Guaranty Agencies Nationwide. Currently, 35 guaranty agencies exist across the country to perform guarantee-related functions on behalf of the federal government. As shown in Figure 2, seven agencies serve as a guarantor in multiple states. Even agencies that are officially designated as guarantor in only one state, such as the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC), are not prohibited from operating in other states. These program rules have allowed several guarantors to develop a national presence. The CSAC, for example, currently has approximately 35 percent of its loan volume from California schools and 65 percent from out-of-state schools. Within California, CSAC currently has 53 percent of all loan volume whereas other guarantors have 21 percent and the direct loan program has 26 percent. Figure 2 ranks guaranty agencies by 2003-04 loan volume.

|

Figure 2 Guaranty Agencies Administering FFELP On Behalf of Federal Government |

|

|

Guaranty Agency |

2003-04 Loan Volumea (In Millions) |

|

United Student Aid Funds (8) |

$9,705.1 |

|

California Student Aid Commissionb |

5,709.5 |

|

Great Lakes Higher Education Corporationb (3) |

3,703.1 |

|

Texas Guaranteed Student Loan Corporationb |

3,246.2 |

|

Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency (3) |

3,112.4 |

|

New York State Higher Education Services Corporation |

2,548.0 |

|

National Student Loan Program |

2,371.7 |

|

American Student Assistanceb (2) |

1,722.6 |

|

Illinois Student Assistance Commission |

1,206.5 |

|

Kentucky Higher Education Assistance Authority (2) |

866.6 |

|

Tennessee Student Assistance Corporation |

754.0 |

|

Education Assistance Corporation |

741.3 |

|

Educational Credit Management Corporationc (2) |

734.7 |

|

Michigan Higher Education Assistance Authority |

707.2 |

|

Missouri Student Loan Program |

651.8 |

|

New Jersey Higher Education Student Assistance Authority |

641.4 |

|

Florida Office of Student Financial Assistance |

564.8 |

|

North Carolina State Education Assistance Authority |

562.3 |

|

Northwest Education Loan Association (3) |

547.4 |

|

Oklahoma Guaranteed Student Loan Program |

514.0 |

|

Colorado Student Loan Programb |

504.0 |

|

South Carolina Student Loan Corporation |

435.3 |

|

Iowa College Student Aid Commission |

413.2 |

|

Louisiana Student Financial Assistance Commission |

396.5 |

|

Student Loan Guarantee Foundation of Arkansas |

375.2 |

|

Utah Higher Education Assistance Authority |

334.9 |

|

Connecticut Student Loan Foundation |

286.9 |

|

Georgia Higher Education Assistance Corporation |

257.8 |

|

Rhode Island Higher Education Assistance Authority |

255.2 |

|

Vermont Student Assistance Corporation |

233.0 |

|

New Hampshire Higher Education Assistance Foundation |

208.4 |

|

Finance Authority of Maine |

187.7 |

|

Montana Guaranteed Student Loan Program |

173.7 |

|

New Mexico Student Loan Guarantee Corporation |

141.1 |

|

Student Loans of North Dakota |

140.8 |

|

|

|

|

a Reflects loan volume for Stafford Loans and Parent Loans for undergraduate students. |

|

|

b Indicates guaranty agency currently has Voluntary Flexible Agreement with United States Department of Education. |

|

|

c Includes loan volume of Oregon State Scholarship Commission, which was transferred to this guaranty agency in 2004. |

|

Five Guaranty Agencies Currently Have Voluntary Flexible Agreements With Federal Government. In 1998, amendments to the Higher Education Act of 1965 gave the United States Department of Education (USDE) the authority to negotiate Voluntary Flexible Agreements (VFA) with individual guaranty agencies. Those guaranty agencies with VFAs receive waivers from certain federal laws and regulations in exchange for meeting certain specified performance outcomes-all of which are negotiated on a case-by-case basis. The overarching intent of the VFA process is to improve FFELP by encouraging experimentation and sharing best practices among guaranty agencies. More specifically, VFAs are intended to shift the focus from collecting on defaulted student loans (the emphasis of the standard guaranty agency model) to improving outreach, default prevention, and loan servicing. Currently, five guaranty agencies, including CSAC, have VFAs (footnoted in Figure 2).

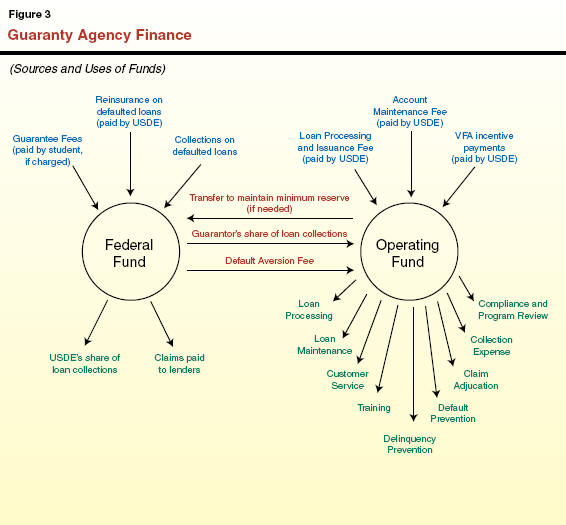

Guaranty Agency Finance. Guaranty agencies are required to be nonprofit. Each guaranty agency is required by federal law to maintain two funds-the Federal Reserve Student Loan Fund (Federal Fund) and the Student Loan Operating Fund (Operating Fund). Figure 3 shows the primary in-flows and out-flows of these two funds.

Federal Fund. The Federal Fund is owned by the federal government and must maintain a minimum reserve requirement equal to 0.25 percent of all the guarantor’s outstanding loan principal. The fund receives monies from two primary sources: (1) reimbursement by the federal government of defaulted loans and (2) collections on defaulted loans from students. In addition, guarantors are allowed to assess borrowers a guarantee fee equal to 1 percent of the original loan amount. Although some guarantors (including CSAC) currently waive this fee, if collected, it is deposited into the Federal Fund. The fund is used to cover costs associated with defaulted loans, including: (1) repaying lenders for defaulted loans, (2) transferring to USDE its share of collection on defaulted loans (typically 77 percent), (3) transferring to the Operating Fund the guarantor’s share of collections (typically 23 percent), and (4) transferring to the Operating Fund a guarantor’s reward for any successful default-aversion activities.

Operating Fund. Whereas the Federal Fund is intended to cover the costs associated with defaulted loans, the Operating Fund is intended to cover the guarantor’s operating costs. In contrast to the Federal Fund, the Operating Fund is owned by the guaranty agency. (Because California’s guaranty agency is a state entity, the state owns the operating fund.) This fund receives monies from various fees (loan processing and issuance fee, account maintenance fee, and default aversion fee) that the federal government pays to the agency. In addition, based on their success in meeting agreed-upon performance goals, those guarantors that have VFAs also receive federal incentive payments, which are deposited into the Operating Fund. Operating Fund monies may be used to fund the guarantor’s various administrative costs as well as outreach, research, and other related financial aid activities.

In 1979, CSAC became California’s designated guaranty agency with responsibility for administering federal student loans. Through 1996, the state relied on CSAC to administer FFELP. During some of this period, CSAC contracted out some loan functions, but, over the entire period, CSAC remained legally responsible for administration of the program.

This organizational structure changed in 1996 when the Legislature enacted Chapter 961, Statutes of 1996 (AB 3133, Firestone). Chapter 961 authorized the commission to establish an auxiliary organization for the purposes of administering FFELP on its behalf. As a result of this legislation, the commission created EdFund in 1997. Ever since, the state has relied on this two-agency model-CSAC administering the state grant programs and EdFund administering FFELP.

Legislature Intended EdFund to Be More Efficient, Effective, and Responsive. In Chapter 961, the Legislature expressed its expectation that the two-agency structure would “enhance the administration and delivery of commission programs and services.” The legislation came in response to growing concerns by the Legislature, federal government, and financial aid stakeholders that CSAC was struggling to administer FFELP effectively. To understand better the problems that spurred the initial creation of EdFund, we reviewed independent evaluations, state audits, and federal audits conducted in the early and mid-1990s. We also conducted interviews with individuals involved in developing the 1996 legislation. The identified problems ranged from financial aid processing difficulties and accounting errors to staff inexperience and perceptions among colleges that CSAC was not adequately responsive or service oriented. The Legislature sought to address all these concerns by authorizing CSAC to establish an auxiliary agency that potentially would be more responsive, adapt more quickly to changes in the student loan market, improve relations with colleges, and develop better information systems.

Auxiliary Agency Exempted From State Employment and Procurement Laws. Statutorily structured as a nonprofit public benefit corporation (more commonly known as a 501 [c][3] agency), EdFund is exempt from certain state employment and procurement practices. Individuals involved in developing the 1996 legislation state that these statutory provisions were viewed as critical changes designed to enhance responsiveness to loan market dynamics, colleges, and students.

Auxiliary Agency Subject to Ultimate Commission Control. Despite being given considerable day-to-day operational autonomy, state law specifies that the auxiliary organization is subject to the overarching authority of the commission. In addition, EdFund’s Articles of Incorporation are explicit that, if the agency were dissolved, the commission obtains EdFund’s net assets. (State law limits the amount of the auxiliary agency’s potential liabilities to the amount contained in its Federal Fund and Operating Fund. This provision protects the state from potential unfunded liabilities owed to the federal government or other parties.)

In this section, we discuss three shortcomings with the existing CSAC/EdFund structure. These shortcomings were identified during our interviews of CSAC and EdFund leadership and in our review of various documents related to CSAC and EdFund (including state law as well as EdFund’s Articles of Incorporation, bylaws, and board agendas). We summarize these shortcomings below and then elaborate upon them in the remainder of this section. (As indicated in the nearby box, we do not discuss potential problems with EdFund’s employment and contracting practices, as these are currently under review by the Bureau of State Audits. The auditor is expected to release its findings in Spring 2006.)

State Audit Underway Examining EdFund’s Employment and Procurement PracticesDuring spring 2005, the Executive Director of the commission publicly expressed concern with EdFund’s compensation and contracting practices. These concerns were shared during discussions with legislators and legislative staff. They also were highlighted in performance reports provided to legislative staff as well as reported in some newspaper articles. The accusation that EdFund might employ inappropriate compensation and contracting practices prompted the Joint Legislative Audit Committee to authorize a state audit, which is scheduled for release in spring 2006. Given the audit is currently underway and its findings and recommendations have not yet been shared, we do not address these issues in this report. |

Having Separate Governing Bodies has Led to Tension Among Organizational Leadership. This has created concern about the stability and viability of the two agencies.

State Law has Not Adequately Delineated Which Agency Is Responsible for Which Operational Functions. This has led to disagreements about each agency’s appropriate roles and responsibilities. What appears to be vigilant oversight and meaningful accountability from some parties’ point of view has appeared as micromanagement and counterproductive interference from others’ point of view.

The Agencies Have Conflicting Incentive Structures. This has hindered a collaborative relationship between the two agencies.

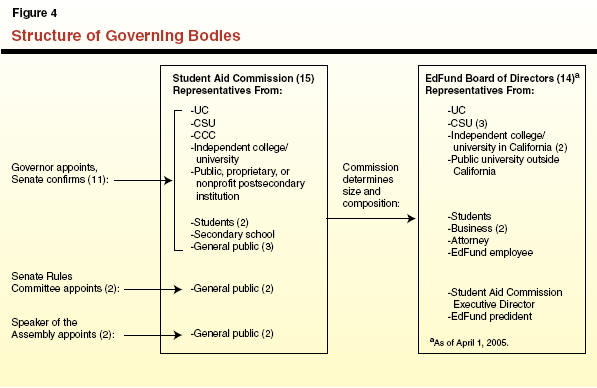

Separate Governing Bodies has Led to Tension Among Organizational Leadership. In our opinion, one of the major shortcomings of the existing structure stems from its competing governing bodies. Figure 4 shows the composition of these governing bodies as of April 2005. As reflected in the figure, state law specifies that CSAC is to be governed by a 15-member commission and entrusts the commission with nominating and appointing a board of directors for its auxiliary agency. The commission is given broad authority to determine both the size and composition of the board. Furthermore, EdFund’s bylaws permit the commission to remove any individual serving on the board at any time, with or without cause. Despite being given no ultimate, independent authority, EdFund is assigned (both by law and its operating agreement) major operational responsibilities. This has created considerable tension between the two agencies since the inception of EdFund.

This tension manifested itself in spring 2005 when the commission voted to dismantle the EdFund board. In the minutes from the April 2005 commission meeting, the commission indicated that its action was motivated by concerns with governance as well as by a desire to ensure that both agencies were working together toward a united set of goals. Many parties-including the chairs of the Senate Education Committee and Assembly Higher Education Committee as well as the California Bankers Association, the California Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators, and the California Community College Student Financial Aid Administrators-expressed concern that the decision to dismantle the board had threatened EdFund’s stability and viability.

State Law Lacks Clarity on Which Agency Is Responsible for Which Operational Functions. A second shortcoming of the existing organizational arrangement is the lack of clarity and agreement on which agency should be entrusted with which specific operational responsibilities. Silent on specific operational issues, state law calls for these responsibilities to be negotiated in a jointly developed annual operating agreement approved by the commission.

In our discussions with CSAC and EdFund leadership, several areas of concern were raised about the existing ambiguity in law and resulting tension within the negotiation process. Most importantly, concerns revolved around determining who is responsible for developing EdFund’s budget, designating the use of Operating Fund (also known as SLOF) monies, representing EdFund interests to the state Legislature, negotiating EdFund’s VFA with the federal government, and resolving grievances of EdFund’s civil service employees. Although the operating agreement addresses some of these issues-for example, it specifies that the use of surplus revenues in the Operating Fund shall be determined by the commission in consultation with the EdFund Board of Directors-many provisions are subject to competing interpretations.

Incompatible Incentive Systems Detract From a Student Focus. A third shortcoming of the existing organizational arrangement relates to the incentive systems that operate within the two agencies. Whereas CSAC is structured as a traditional state agency whose employees are subject to civil service laws and regulations, EdFund’s status as a nonprofit corporation has fostered more market-driven practices. A CSAC “Policy Statement and Guidelines Memo” describing EdFund’s incentive compensation plans begins with the statement, “It is the Commission’s intention that EdFund function as a performance based organization. EdFund offers its employees incentive compensation plans in furtherance of this intent.” EdFund uses variable payment plans that allow it to offer incentive compensation to reward employees for providing high-quality service in their respective area. These variable compensation plans are notably different from typical civil service compensation plans based on routine step increases that are not directly linked to providing high-quality service to students.

The leadership of both agencies expressed concern to us that these incompatible incentive systems (or “cultures,” in their words) have led to certain perceptions of unfairness among staff and directors. Equally important, the resulting interagency tension has detracted from a public focus on providing students with high-quality loan and grant service.

In this section, we first describe the range of organizational options the Legislature has for administering FFELP. We then highlight issues we think the Legislature should consider when deciding which of these various options to adopt.

As summarized in Figure 5, the Legislature can select one of five basic organizational models for administering FFELP. Under a single-agency structure, the Legislature could: (1) entrust a state agency with administrating both grant and loan programs or (2) establish a nonprofit public benefit corporation to perform them. Under a two-agency structure, the Legislature could: (3) retain the existing two-agency arrangement, (4) modify the existing two-agency arrangement, or (5) rely on an independent guaranty agency to administer FFELP.

|

Figure 5 Organizational Options |

|

|

Single Agency |

|

|

State Agency Model |

Nonprofit Public Benefit Corporation Model |

|

Single state agency administers state grant programs and serves as designated federal loan guaranty agency. |

Single nonprofit public benefit corporation administers state grant programs and serves as designated federal loan guaranty agency. |

|

Agency subject to state employment and procurement laws and regulations. |

Agency exempt from state employment and procurement laws and regulations. |

|

Options as Applied to California: |

|

|

(1) California Student Aid Commission (CSAC) (or another state agency) administers both grant and loan programs. |

(2) EdFund (or another nonprofit public benefit corporation) administers both grant and loan programs. |

|

Two Agencies |

|

|

State/Dependent Guarantor Model |

State/Independent Guarantor Model |

|

A state agency administers state grant programs and a separate auxiliary, affiliate, or chartered state-dependent agency serves as designated federal loan guaranty agency. |

A state agency administers state grant programs and contracts with independent guarantor to provide federal student loan guarantees. |

|

State employment and procurement laws apply to state agency but not auxiliary agency. |

State employment and procurement laws apply to state agency but not independent guarantor. |

|

Option as Applied to California: |

|

|

(3) Make no changes to existing CSAC/EdFund arrangement. |

(5) Rely on an independent guarantor—either a reconstituted EdFund or another existing guaranty agency. |

|

(4) Modify CSAC and EdFund's roles and responsibilities. |

|

The Legislature has two basic single-agency options. It could unify grant and loan functions under a state agency or under a nonprofit public benefit corporation.

Option 1-Single State Agency. Under the first option, the Legislature would reestablish a unified state agency (either CSAC or another agency) that would be responsible for administering both state grant programs and FFELP. This agency would be California’s designated guarantor. Practically, this option would require eliminating EdFund’s existing Board of Directors, consolidating the agency with CSAC (or another state agency), and subjecting the reconfigured CSAC to all applicable state laws and regulations, including those relating to hiring, compensation, promotion, and procurement. Under this model, the state agency could provide all operational functions internally, or it could contract for any or all grant and loan services. As shown in Figure 6, 15 states currently have a unified state agency structure.

|

Figure 6 States’ Organizational Arrangementsa |

|||

|

Single Agency |

|||

|

Option 1: State Agency Structure (15) |

Option 2: Nonprofit Public Benefit Corporation Structure (2) |

||

|

Colorado |

Montana |

Kentucky |

|

|

Georgia |

New Jersey |

Pennsylvania |

|

|

Florida |

New York |

|

|

|

Iowa |

North Carolina |

|

|

|

Louisiana |

Oklahoma |

|

|

|

Maine |

Rhode Island |

|

|

|

Michigan |

Utah |

|

|

|

Missouri |

|

|

|

|

Two Agencies |

|||

|

Options 3 and 4: State/Dependent Guarantor Structure (7) |

Option 5: State/Independent Guarantor Structure (26) |

||

|

California |

States that use a private corporation: |

||

|

Connecticut |

Alaska |

Nevada |

|

|

Illinois |

Arizona |

New Hampshire |

|

|

South Carolina |

Arkansas |

New Mexico |

|

|

Tennessee |

Hawaii |

North Dakota |

|

|

Texas |

Idaho |

Ohio |

|

|

Vermont |

Indiana |

Oregon |

|

|

|

Kansas |

South Dakota |

|

|

|

Maryland |

Virginia |

|

|

|

Massachusetts |

Washington |

|

|

|

Minnesota |

Wisconsin |

|

|

|

Mississippi |

Wyoming |

|

|

|

Nebraska |

|

|

|

|

States that use another state’s guaranty agency: |

||

|

|

Alabama (uses Kentucky’s agency) |

||

|

|

Delaware (uses Pennsylvania’s agency) |

||

|

|

West Virginia (uses Pennsylvania’s agency) |

||

|

|

|||

|

a This table reflects our best attempt to classify other states' organizational arrangements. To our knowledge, no "official" list of states' organizational arrangements exists. As part of our study, we contacted the federal government, academic researchers, and national financial aid policy experts—none of whom were aware of any state-level comparison. EdFund staff provided general guidance to us in preparing the above list. |

|||

Option 2-Single Nonprofit Public Benefit Corporation. Alternatively, the Legislature could establish in statute a single nonprofit public benefit corporation to administer both grant and loan programs. As a nonprofit corporation, the agency would be exempt from state employment and procurement practices. The agency could still be required to implement certain grant programs and adhere to certain reporting requirements as well as accountability provisions. Kentucky and Pennsylvania’s existing organizational arrangements are the only ones that somewhat resemble this type of structure. Although Kentucky has statutorily established both a grant agency and a nonprofit loan corporation, the two organizations are governed by one Executive Director and the same governing board. This leadership body also is responsible for administering work study programs, the state’s college savings program, and a prepaid tuition program-thereby consolidating all financial aid programs into one umbrella agency. Although slightly less overarching, Pennsylvania’s Higher Education Assistance Agency is a statutorily created nonprofit public benefit corporation that serves both as the state’s guaranty agency and grant agency.

Instead of a single-agency structure, the Legislature could maintain a two-agency structure in which one agency administers state grant programs and another agency administers FFELP. The majority of states currently have a two-agency structure. Many possible permutations exist for the specific structuring of a two-agency model. That is, the two agencies could be subject to all, none, or any subset of state employment and/or procurement laws. Among the many possibilities, the Legislature has three basic options under a two-agency structure.

Option 3-Maintain Status Quo. The Legislature could retain the existing CSAC/EdFund arrangement, making no statutory changes. This is the simplest option in that it leaves the existing organizational arrangement intact. This option, however, does not address the various shortcomings-both recent and longstanding-identified earlier in this report. That is, this option would not address the existing tension resulting from (1) separate CSAC/EdFund governing bodies, (2) ambiguity concerning each agency’s roles and responsibilities, and (3) differences in the agencies’ incentive systems.

Option 4-Modify Roles and Responsibilities Within Existing Two-Agency Structure. The Legislature could retain the existing organizational arrangement while modifying specific organizational or operational components of that structure. As shown in Figure 6, six other states currently have organizational structures similar to that of CSAC and EdFund. That is, these states have one agency that administers state grant programs and another agency that is auxiliary to, affiliated with, or chartered by the state grant agency or the state government. If this basic structure were retained, the Legislature could make specific statutory changes to address the problems identified earlier in this report. For example, the Legislature could adopt in statute an explicit revenue-sharing expectation that would specify what percentage of Operating Fund monies would be designated for state grant programs as well as an explicit expectation regarding which agency is responsible for state and federal representation.

Option 5-Designate New Independent Guarantor. Instead of using a guarantor that is dependent on the state (that is, the agency is an auxiliary of, affiliated with, or chartered by the state), the Legislature could establish an independent guarantor. Although the state for federal purposes would officially designate this entity as its FFELP guarantor, it would have little, if any, control over the entity’s operations. The Legislature has two basic options when selecting an independent guarantor: (1) convert EdFund into an autonomous entity outside of the state’s direct control or (2) rely on another existing guaranty agency. As identified in Figure 6, 26 states currently rely upon an independent guarantor. Of these states, 23 rely on a nonprofit private corporation as its guarantor whereas 3 rely on another state’s guarantor.

Whereas the Legislature could grant EdFund autonomous status via a relatively simple statutory change, transitioning to another guaranty agency would be more involved. This is because the transition would likely entail selling EdFund’s existing loan portfolio. Because EdFund is currently the second largest guarantor in the country, only a few large loan companies have the resources needed to buy EdFund. A few other guaranty agencies, while not large enough to purchase EdFund, could merge or form a partnership with EdFund, thereby creating a new offshoot guaranty agency. Under either an outright sale or a partnership, the Legislature could structure the transaction in various ways. Most simply, it could accept: (1) one upfront, lump-sum payment equal to the assessed value of EdFund, (2) a negotiated partial upfront payment and then annual payments over some specified time period, or (3) no upfront payment but potentially larger annual payments over some specified time period.

As described in the above section, the Legislature has five basic options for administering FFELP. In assessing the merits of the available organizational options, we encourage the Legislature to keep in mind both the shortcomings of the existing organizational arrangement as well as the shortcomings that led to EdFund’s initial creation. We think any effective solution should address and correct for these shortcomings. In particular, an effective solution should: (1) restructure the existing organizational leadership; (2) clarify roles and responsibilities; (3) establish a clear revenue-sharing expectation; (4) rely on incentive systems that reward high-quality service to students; and (5) promote efficiency, effectiveness, and responsiveness. Below, we discuss each of these organizational objectives.

Restructure Organizational Leadership. Any solution should strive to reduce potential internal conflict among organizational leadership. A major shortcoming of the existing organizational arrangement has been the tension inherent in having a CSAC Commission and a separate EdFund Board of Directors-a board that is given substantial operational responsibility but no ultimate authority. Any organizational solution should attempt therefore to promote greater organizational cohesion, especially among leadership. This level of cohesion is unlikely to be achieved if each party has its own governing body. Promoting cohesion is relatively easy in a single-agency structure, whereas more care needs to be taken in promoting cohesion under a two-agency shared-control structure.

Designate More Clearly Who Is Responsible for What. Any solution should clarify in statute who is entrusted with major operational responsibilities. Most importantly, any solution should clarify who is responsible for budget development and resource allocation as well as policy development and state and federal representation. The solution also should clarify the extent to which any party is to have autonomy over employment and procurement policies. These issues could be relatively easily addressed under a single-agency structure. More careful attention needs to be given to these issues under a two-agency shared-control structure, as each agency’s responsibilities need to be designated explicitly. Indeed, lack of clarity regarding who is responsible for what likely has been one of the greatest shortcomings of the existing organizational arrangement.

Establish Clear Revenue-Sharing Expectation. The budgeting of monies from the guarantor’s Operating Fund has also been a serious source of contention. Any solution therefore should both clarify who has control over budgeting these monies and establish a clear revenue-sharing expectation. For example, the Legislature might specify, within some range, that a percentage of Operating Fund monies be annually transferred to the Cal Grant program. To date, these transfers have occurred on an ad hoc basis. Every party we interviewed, however, highlighted the obvious fiscal benefit of these transfers. Although establishing clear budget control and revenue-sharing expectations might be easier in a single-agency structure, the Legislature should carefully delineate these expectations regardless of the organizational structure.

Design Incentive System(s) to Reward High-Quality Service to Students. Any solution also should reward all employees for providing excellent service to students. Given the tension between CSAC and EdFund resulting from incompatible employee incentive systems, meeting this organizational objective would require that the existing incentive systems be assessed and modified as needed to ensure all employees are rewarded for providing excellent student service. As with some of the other organizational objectives, developing two compatible incentive systems or developing a unified incentive system that rewards high-quality service might be easier under a single-agency structure. Nonetheless, whether using a single-agency or two-agency structure, the Legislature should monitor and assess the incentive system(s) by carefully specifying certain fiscal and program reporting requirements. Information about any agency operations should be obtained annually by independent, unbiased sources.

Continue to Foster Efficiency, Effectiveness, and Responsiveness. Any solution should strive to meet the above conditions without weakening what many parties would deem the success of the existing organizational structure-the ability of EdFund to be responsive to students, schools, lenders, and the dynamics of the student loan market. The Legislature created the two-agency model largely because California was struggling to administer FFELP effectively under a state-agency structure. This historical experience (as well as the experience of other states) might suggest that a two-agency structure or a nonprofit public benefit corporation structure would be better able than a single state-agency structure to meet the challenges inherent in administering a market-oriented federal student loan program.

In conclusion, the Legislature has five basic organizational options for administering FFELP. It also has five critical organizational objectives to keep in mind when selecting among these options and developing a new organizational solution. As described above, not every option is equally likely to be successful in meeting the identified objectives. That is, not every option is equally likely to be able to build upon the strengths of the existing organizational structure while addressing its weaknesses. Thus, when assessing the merits of these options, the Legislature should strive to find an option that meets as many of these objectives as possible-thereby addressing both recent and longstanding shortcomings associated with the existing organizational structure.

This report was prepared by

Jennifer Kuhn,

and reviewed by Steve Boilard. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office

which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the

Legislature. To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail

subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at

www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000,

Sacramento, CA 95814.

Acknowledgments

LAO Publications

Return to LAO Home Page