February 17, 20066

The costs of providing health care to retired state employees and their dependents-now approaching $1 billion per year-are increasing significantly. Many other public employers (including the University of California, school districts, cities, and counties) face similar pressures. This report discusses health benefits provided to retired public employees, focusing on state retirees. We find that the current method of funding these benefits defers payment of these costs to future generations. Retiree health liabilities soon will be quantified under new accounting standards, but state government liabilities are likely in the range of $40 billion to $70 billion-and perhaps more. This report describes actions that the Legislature could take to address these costs.

Background. Like many employers, governments in California often pay for health and dental insurance for their employees and eligible family members after retirement. Costs for retiree health benefits have been rising rapidly-increasing faster than both inflation and the overall growth rate of government spending.

Retiree Health Benefits Are Not Prefunded�Unlike Pensions. Almost all public entities in the United States pay for retiree health benefits in the year the benefits are used by retirees. This is sometimes called the �pay-as-you-go� approach, and it differs from the prefunding model used for most pension benefits-where most costs are funded in advance during employees� working years and invested until paid to retirees. The pay-as-you-go approach has led to the accumulation of massive financial liabilities to pay for future retiree health benefits. These liabilities will be quantified under new government accounting rules that come into effect in 2007-08.

Structure of This Report. This report focuses on the state�s costs for providing benefits to its own retired employees, while also discussing similar issues for the University of California (UC), local governments, and school districts. The report first describes existing benefits for retirees and then outlines the new accounting rules. We then discuss the magnitude of financial liabilities for retiree health benefits and offer policy recommendations and options for governments to address these liabilities.

In 1961, the Legislature for the first time appropriated funds to the State Employees� Retirement System-the predecessor to the California Public Employees� Retirement System (CalPERS)-to provide health benefits to state employees and retirees. The state paid most of the costs of a basic employee and retiree health plan-with state contributions per employee set at $5 per month in 1961-62. Total costs at that time were $4.8�million (then under 0.3�percent of General Fund spending). The $5 state contribution mirrored the provisions of the new federal employee health program, which began operations in 1960. Figure�1 lists key events in the evolution of the state�s retiree health program over the past half century. Since 1974, the state has paid a percentage of health costs, rather than a fixed amount.

|

Figure 1 State Retiree Health Benefits—Key Historical Events |

|

|

Year |

Event |

|

1961 |

State contributions of $5 per month begin. |

|

1967 |

Local agencies begin contracting with CalPERS for health benefits. |

|

1974 |

State pays 80 percent of employee/retiree and 60 percent of dependent costs. |

|

1978 |

State pays 100 percent of employee/retiree and 90 percent of dependent costs. |

|

1984 |

State costs exceed $100 million. Legislature increases years required for employees to vest in retiree health benefits. |

|

1991 |

State begins to pay less than 100/90 formula for current employees. The 100/90 formula continues for retirees. |

|

2006 |

The 2006‑07 Governor's Budget projects that costs will exceed $1 billion. |

Current law provides state contributions for retiree health benefits on the basis of a �100/90 formula.� Under the formula, the state�s contributions are equal to 100�percent of a weighted average of retiree health premiums and 90�percent of a similar weighted average for additional premiums necessary to cover eligible family members of retirees. The formula bases payments on the weighted average of premium costs for single enrollees in the four basic health plans with the largest state employee enrollment during the prior year. The formula applies to all eligible retirees, including those from the California State University system.

Vesting Requirements for State Contributions. Most state employees hired since 1985 receive full state contributions only after a period of vesting. Retirees and their eligible family members generally receive no state health contributions with less than ten years of service. They receive 50�percent of the contribution with ten years of service, increasing 5�percent annually until the 100�percent level is earned after 20 or more years of employment. State employees hired prior to 1985 are fully vested for health benefits upon retirement.

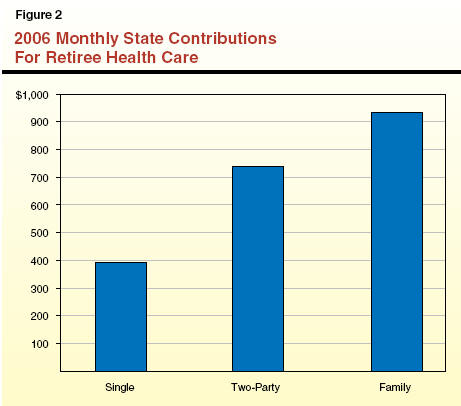

2006 State Contribution Levels. Legislative approval of funding for retiree health and dental benefits occurs in the budget act, following CalPERS� negotiation of health plan rates for the upcoming calendar year. For 2006, the 100/90 formula contributions are based on the premium costs for the four largest CalPERS health plans: Blue Shield�s health maintenance organization (HMO), Kaiser Permanente�s HMO, the PERSCare preferred provider organization (PPO), and the PERS Choice PPO. This results in a 2006 required state contribution of $394 per month for a single retiree, $738 per month for a retiree and a family member, and $933 per month for a retiree family, as shown in Figure�2.

Retirees Under Age 65. A retiree�s vested state contribution amount may or may not cover the entire premium cost for a desired health care plan. For instance, for a fully vested 60-year-old retiree with a spouse or domestic partner of the same age, the 100/90 formula results in state contributions of $738 per month. In 2006, the state contribution for this couple covers all premiums for the Kaiser Permanente HMO plan. To join a Blue Shield HMO plan in 2006, the couple must pay $33 extra per month above the state contribution. To join PERSCare-with its flexible PPO options, including the ability to switch physicians or see specialists without referral-the family must pay $609 extra per month. (The 2006 monthly premiums for selected health plans administered by CalPERS are listed in Figure�3. Retirees under age 65 enroll in the basic plans listed in the top part of the figure.)

|

Figure 3 2006 Monthly Premiums for Selected State Employee Health Plans |

|||

|

|

Single |

Two-Party |

Family |

|

Basic Plan Premiums |

|

|

|

|

Kaiser Permanente Basic HMO |

$365 |

$730 |

$949 |

|

Blue Shield Basic HMO |

386 |

771 |

1,003 |

|

PERS Choice Basic PPO |

401 |

801 |

1,042 |

|

PERSCare Basic PPO |

674 |

1,347 |

1,752 |

|

Medicare Plan Premiums |

|

|

|

|

Kaiser Permanente HMO Medicare Advantage |

$219 |

$437 |

$656 |

|

Blue Shield HMO Medicare Supplement |

286 |

573 |

859 |

|

PERS Choice PPO Medicare Supplement |

322 |

644 |

966 |

|

PERSCare PPO Medicare Supplement |

347 |

694 |

1,042 |

|

|

|||

|

HMO = Health Maintenance Organization. PPO = Preferred Provider Organization. |

|||

For many retirees from state service who are between the ages of 50 and 65, retirement brings no immediate change in health plans or coverage. These persons can remain in the same CalPERS basic health plan they had when they worked for the state. Rather, the changes they experience after retirement are largely financial. During their working years, these individuals and their family members probably received health benefits under 80/80 or 85/80 state contribution formulas included in collective bargaining agreements between the state and employee bargaining units. After retirement, the new retirees and their families typically receive benefits under the more generous 100/90 formula. Upon retirement, therefore, an individual may experience a reduction in the premium expenses he or she pays-with the state contributing an increased share.

Retirees, Age 65 and Over. Upon reaching age 65, most state retirees receive coverage under the federal government�s Medicare Part A program (for hospital and similar benefits). Eligible state retirees must join Medicare Part A and Part B (for outpatient benefits), and at that time, they become eligible for coverage under one of CalPERS� Medicare health plans. These CalPERS plans supplement the federal government�s health coverage and reduce the out-of-pocket costs required under Medicare-including premiums, deductibles, and copayments. Because the federal government covers a significant portion of health costs for retirees on Medicare, the premiums for CalPERS� Medicare plans are lower than those of CalPERS� basic health plans for current state employees and retirees under age 65. Monthly premiums in 2006 for some of CalPERS� Medicare plans are listed in the bottom part of Figure�3.

Retirees over age 65 and eligible family members receive the same monthly state contribution for health premiums as younger retirees. For a fully vested 67-year-old state retiree with a spouse or domestic partner of the same age, for example, this means that the state contribution for 2006 covers all monthly premium costs for the four CalPERS Medicare plans listed in Figure�3. After providing for these premium costs, $301 of the state contribution is unused if the couple enrolls in the Kaiser Permanente Medicare Advantage plan, and $44 is unused if the couple enrolls in the PERSCare Medicare Supplement plan. State law provides that this unused portion of the state contribution may be used to pay all or part of Medicare Part B premiums for retirees and eligible family members. (In 2006, monthly Medicare Part B premiums are just under $89.) If any portion of the state contribution remains unused after paying these costs, it will remain unused since the retiree does not receive a refund for any remaining amount.

Some state retirees-including some who were first hired before 1986, when Medicare taxes became mandatory for most state and local government employees-are not automatically eligible for Medicare Part A coverage when they reach the age of 65. These retirees and some others can remain in CalPERS� basic health plans.

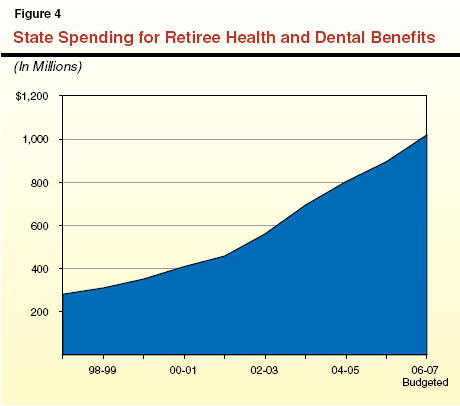

Figure�4 shows that state costs for retiree health and dental benefits have increased rapidly in recent years. They have more than tripled in the last nine years, reaching $895�million in 2005-06. The 2006-07 Governor�s Budget projects that retiree health and dental costs will exceed $1�billion in 2006-07. Since 2000-01, retiree health expenditures have increased an average of 17�percent annually, or more than five times the rate of growth of state spending.

Health Care Costs Have Risen Rapidly. For the last four decades, national health expenditures consistently have grown at a faster rate than the overall economy. Since 1999, health spending has increased by more than three times the rate of inflation. Federal data show that the cost drivers in California�s health care system mirror those of the nation as a whole: principally, prescription drugs, physicians and other professional services, and hospital care. The bargaining power of hospitals has increased in recent years, and a limited supply of nurses has also contributed to cost increases.

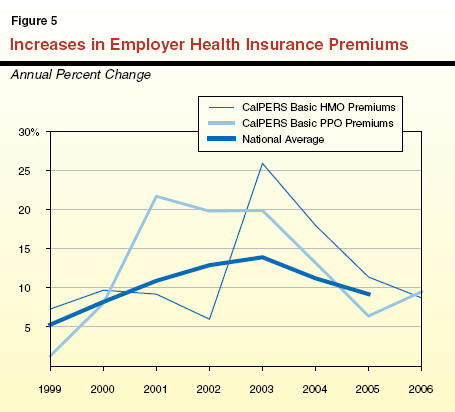

Employer Health Premiums Rising Even Faster. In recent years, employer health premiums-such as those negotiated for the state by CalPERS-have risen even faster than the rate of overall medical expenditures. Employers� expenditures to purchase health coverage reflect the general costs of medical care, other costs associated with a private insurance market (insurer reserves, the pricing of pooled risk, and a return on capital), and the health care industry�s shifting of costs not paid by the large, but typically unprofitable, Medicare and Medicaid programs. As shown in Figure�5, the state�s premiums in most recent years have risen faster than the national average for public and private employers. The growth each year, which is determined by annual negotiations with health plans, can be quite volatile. Some recent years have seen double-digit increases.

Research shows that trends in the rate of growth of employer premiums follow a cyclical pattern, characterized by some experts as an insurer underwriting cycle. Many, if not most, researchers believe that U.S. health insurers are entering a lull in this underwriting cycle, when annual premium growth will be slower than in recent years. Recent cost containment actions of CalPERS (summarized in Figure�6) and other purchasers of health coverage seem to have contributed to a slowdown in premium growth since 2004. In our fiscal outlook for the state, we project that CalPERS premiums will continue to grow through 2010-11, but moderate and move closer to the overall rate of medical inflation over time.

|

Figure 6 Selected CalPERS Cost Saving Measures Since 2002 |

|

|

Action |

Comment |

|

Ended relationship with Health Net and PacifiCare Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) in 2003. |

Avoided $77 million cost increase for state and local health programs. |

|

Raised office visit copayments to $10 in 2002, as well as other copayment increases. |

First changes in copayments for HMO members since 1993. |

|

Eliminated high-cost hospitals from Blue Shield provider network beginning in 2005. |

Saved an estimated $45 million. |

|

Adopted regional pricing. |

Prevented large-scale exodus of local participants in Southern California, which would have diminished health plan's bargaining power. |

|

Provided incentives to purchase over- the-counter drugs and refill prescriptions by mail. |

Saved an estimated $27 million. |

|

Moved certain age 65 and older members from basic to Medicare plans. |

Saved an estimated $19 million. |

|

Building large purchaser coalition, Partnership for Change, to enhance bargaining power. |

May produce uniform standards for hospital quality and pricing. |

|

Encouraging health plan partners' disease management programs. |

May produce savings and improved care for conditions like diabetes and asthma. |

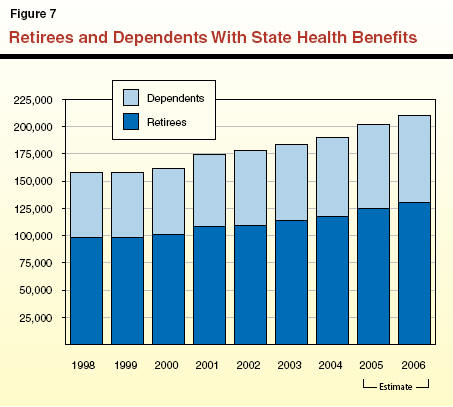

More Retirees: The Other Cost Driver. The number of retirees that the state covers in its health programs continues to rise. Californians are living longer, and the large �baby boom� generation has begun to retire. Consequently, state employees are entering retirement faster than prior retirees and family members are dying. Figure�7 shows that the number of retirees covered by state health plans has increased an average of 3.6�percent annually since 1998.

We estimate that 35�percent to 45�percent of the state�s active workforce will retire within the next ten years. Assuming this level of retirements and retirees� increasing longevity, we forecast that the number of retirees and dependents covered by the state�s health program will increase by almost 4�percent annually through 2010-11. This trend, combined with continued premium growth, results in our projection of continued double-digit growth in the cost of state retiree health and dental benefits. We project that these costs will increase from $1.0�billion in 2006-07 to $1.6�billion in 2010-11.

In addition to state health benefit programs provided through CalPERS, other public agencies in California offer a wide variety of health benefit programs for current employees, retirees, and eligible family members. Some offer coverage until retirees (and, in some cases, family members) reach the age of eligibility for Medicare-usually age 65. Some provide benefits to supplement Medicare after age 65. Below, we summarize selected characteristics of some of these plans.

The UC administers its employee and retiree health program separately from CalPERS. As a result, there are some differences in plan options and premiums. One difference is that, unlike CalPERS, UC benefit plan documents explicitly state that retiree health benefits are not vested or accrued entitlements and that the Regents may change or stop benefits altogether.

2006 UC Contributions. The UC�s maximum retiree health contribution-provided based on years of service-covers most premium costs. For single UC retirees in California under age 65, UC�s maximum 2006 health plan contributions cover all but $18 to $27 of monthly HMO premiums and all but $70 to $75 of monthly PPO and point of service (POS) plan premiums. The UC also offers a high-deductible fee-for-service plan-for which the maximum UC contribution covers all premium costs-designed to provide some protection in the event of a catastrophic illness. For UC retirees over age 65 and on Medicare, UC�s supplement plans generally have premiums that are entirely covered by the maximum UC contribution (which also typically pays all Medicare Part B premiums).

Costs Growing Rapidly. In 2004-05, UC retiree health and dental benefit costs totaled $193�million, or 1�percent of total university revenues. Between 1997-98 and 2004-05, as illustrated in Figure�8, these costs grew an average of 12�percent annually. The UC retiree population grew at a rate of 2.2�percent annually during this period.

A Wide Variety of Benefit Packages. Hundreds of California school districts and community college districts offer varying levels of health benefits to employees and retirees. Premiums, employer contributions, copayment levels, deductibles, covered services, and retiree benefits differ based primarily on collective bargaining agreements with certificated employees (that is, teachers and other licensed staff) and classified employees. In contrast to the standardized management of pension benefits offered to school employees-through the California State Teachers� Retirement System (CalSTRS) and CalPERS-administration of school district health plans varies widely.

As of 2004, 114 school and community college districts (out of a total of almost 1,100) contracted with CalPERS for employee and retiree health coverage. About 265 districts purchased coverage through 11 benefit trusts, which allow multiple districts to join together to achieve economies of scale. In addition, the Kern County Office of Education administers the Self-Insured Schools of California joint powers agency, which provided benefits to more than 250 school employers in 31 counties, as of 2004. The remaining districts either secure health benefits on their own or do not provide these benefits.

CalSTRS Survey of Benefits. A survey conducted by CalSTRS in 2003 revealed more information about the variety of health benefits offered to retired teachers. The CalSTRS estimated that districts covering 57�percent of retired teachers statewide pay all or a portion of retirees� health insurance premiums. The survey, however, showed that only about 7�percent of districts offer lifetime benefits, such as those offered by the state, UC, and by some of the largest school districts, including the Los Angeles Unified School District. In more than half of responding districts retired teachers were required to pay all of their own health insurance premiums beginning at age 65.

Legislative Actions to Enhance Retired Teachers� Benefits. Since 1985, the Legislature has taken several actions to enhance health benefits of retired teachers. Districts that provide health or dental benefits for current teachers must permit retired teachers and their spouses to enroll in the same plan, pursuant to a series of laws that began with enactment of Chapter�991, Statutes of 1985 (AB 528, Elder). Chapter�991 does not include a requirement for districts to contribute to retirees� coverage, and the law also allows plans to set higher premiums for retired members (compared to current employees) based on retirees� typically higher utilization of medical services. Many districts offer only the minimum required benefits to retirees under Chapter�991 and subsequent legislation. A CalSTRS program authorized by Chapter�1032, Statutes of 2000 (SB 1435, Johnston), also pays Medicare Part A premiums for 6,000 retired teachers not automatically eligible for this federal program.

Counties, cities, and special districts offer a wide variety of retiree health benefits. Most appear to offer some type of health benefit to retired employees through a publicly administered health program also offered to current employees. Many offer benefits through CalPERS.

In September 2005, the California State Association of Counties surveyed county officials on retiree health benefits. Of 49 counties responding (including eight of the ten largest counties), 48 reported that retired employees are eligible for some type of health benefits. (Modoc County was the only one reporting that retirees received no health benefits.) An estimated 117,000 retired employees of responding counties�currently receive�health benefits at a combined cost of around $600�million per year.�In more than two-thirds of counties, retirees pay the same premium rates as active county employees. Of the 49 counties, 43 continue to offer health benefits to retirees after the age of 65, and 44 extend coverage to retirees� dependents. Of the total cost for county retiree health benefits, about half is paid directly�from county operating budgets, and another one-fourth is paid from funds of retirement systems or county trusts. Almost all counties use a pay-as-you-go approach for part or all of their retiree health benefits. We did not locate similar surveys of cities or special districts during our research.

The rules that govern how governments account for retiree health benefits are in the process of changing. The Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) establishes accounting rules for state and local governments (and related entities, such as public universities and retirement plans). Audited financial statements of governments prepared according to GASB rules are most closely scrutinized by investors in state and local bonds and the rating agencies that make judgments on the likelihood those bonds will be paid off as required. The board was created in 1984 as a parallel to a similar board that governs corporate accounting. In that same year, the Legislature enacted a law requiring the state�s financial statements to comply with GASB�s rules.

To bring governmental accounting standards more into line with those of private companies, GASB has implemented a series of accounting rules, known as statements, concerning governmental liabilities related to retirement benefits. In 2004, GASB released Statement 45 (GASB 45) concerning health and other non-pension benefits for retired public employees. These benefits, collectively, are known as �other postemployment benefits,� or OPEB. Retiree health programs are, by far, the most costly of these benefits.

The GASB has no power to change how governments fund retiree health, pension, and other benefits. Instead, the GASB governs the rules that auditors must follow in providing opinions on the reliability of government financial statements.

The new accounting rule dramatically increases the amount and quality of information included in government financial reports with respect to retiree health and other retiree benefits. State and local governments-working with their accountants and actuaries-must take a series of steps that include quantifying the unfunded liabilities associated with retiree health benefits. Results of the actuarial valuations must be reported in government audits and updated regularly. The accounting standard sets deadlines requiring large governments (including the state, most counties, many cities, and some school districts) to comply beginning with release of their 2007-08 financial reports. (The state�s financial reports usually are released in February or March following the end of the fiscal year.) Smaller governments will implement GASB 45 in the following two years.

Under GASB 45, government financial statements will list an actuarially determined amount known as an annual required contribution. This contribution, with regard to health and related benefits, is comprised of the following two costs:

The �normal cost�-the amount that needs to be set aside in order to fund future retiree health benefits earned in the current year.

Unfunded liability costs-the amount needed to pay off existing unfunded retiree health liabilities over a period of no longer than 30 years.

Retiree health benefits, like pension benefits, are a form of deferred compensation-that is, compensation earned by employees during their working years, but paid to (or used by) individuals after they retire. Pension systems typically are funded by governments paying normal costs each year-as employees earn this type of deferred compensation-and the funds are invested so that they generate returns and grow until required to be paid to the employees after retirement. This is known as �prefunding,� and pension accounting standards focus on how well retirement systems are prefunded. To the extent that funds set aside each year (with assumed, future investment earnings) are insufficient to cover projected benefit costs, the system has an �unfunded liability.� Retiree health programs now will have accounting standards that are very similar. GASB 45 will result in calculation of an unfunded liability for retiree health programs similar to the comparable figure for pension systems.

For governments that fund retiree health benefits on a pay-as-you-go basis (such as the state), 100�percent of retiree health liabilities will be unfunded. (In contrast, the average state pension system currently has about a 20�percent unfunded liability. Although this unfunded liability totals tens of billions of dollars in the cases of CalPERS and CalSTRS, more than 80�percent of their liabilities have been funded in advance from investment returns and contributions by employees and employers.)

The liabilities for retiree health benefits-like those for pension systems-will be determined by actuaries and accountants based on certain assumptions of future health care cost inflation, retiree mortality, and investment returns. This unfunded liability can be characterized as an amount which, if invested today, would be sufficient (with future investment returns) to cover the future costs of all retiree health benefits already earned by current and past employees.

All 50 states offer health benefits to their retirees in some or all age groups. As of 2003, 17 states, including California, covered up to 100�percent of health benefit costs for some retirees. Only 11 states reported any prefunding of retiree health benefits at all (most of these with only a tiny amount of funds set aside). The GASB 45 accounting requirements likely will lead to an increase in the number of states prefunding these benefits. Only a few states have completed the actuarial valuations needed to determine unfunded retiree health and other liabilities, as well as the annual contributions, required by GASB 45. We discuss the status of two states below and corporate responses to similar rules in the nearby box.

Corporate America�s Retiree Health LiabilitiesSharp Decline in Retiree Health Coverage. Since corporations began to account for retiree health liabilities in 1990 (due to a change in business accounting standards), investors have pressured them either to fund the liabilities or drop the benefits altogether. The percentage of large private U.S. firms offering health benefits to retirees has dropped from about 66�percent in 1988 to about 33�percent in 2005. The trend among California companies has been similar, with 32�percent of large firms here continuing to offer retiree benefits. Even companies continuing to offer benefits have cut costs in some cases by: imposing caps on the amount they will pay toward retiree health care; increasing copayments, deductibles, and drug costs paid by retirees; aggressively bargaining with health insurers and providers; and making many other changes. Companies also may seek bankruptcy protection to restructure retirement benefits. (Local governments and school districts also can do this under state law.) General Motors Corporation (GM). The second largest purchaser of employer health benefits in the United States, GM ranks behind the U.S. government and ahead of CalPERS (the third largest purchaser). As of September 2004, GM reported in financial statements that its unfunded retiree health and related liabilities exceeded $61�billion. Retiree health expenses add significantly to the costs of GM cars and trucks and are believed to have contributed to a decline in the company�s finances. Ratings of GM bonds have dropped to junk status, and some have speculated that a bankruptcy filing may be inevitable. In October 2005, GM and the United Auto Workers (UAW) reached agreement to cut retiree health liabilities by $15�billion. The company agreed to start a new defined contribution health plan to offset other reductions in the health benefits provided to retired workers. While UAW�s rank-and-file employees approved the agreement, implementation awaits a U.S. District Court review of objections from a retiree claiming that UAW lacks the authority to negotiate concessions of retiree health benefits. The retiree claims the benefits are vested contractual rights. |

Maryland: Considering How to Finance a Large Liability. The State of Maryland-which has a AAA bond rating (the highest possible)-assessed its situation relative to the GASB 45 requirements through a valuation completed in October 2005. The state�s unfunded liability under GASB 45, principally for retiree health benefits, was valued at $20�billion, or about twice the size of the state�s general fund budget. Maryland currently pays $311�million per year for retiree health benefits on a pay-as-you-go basis. Maryland�s state workforce and retirees number about one-fourth of California�s, and the state annually pays about one-third of the amount California pays for retiree health benefits. Maryland�s annual retiree health contribution under GASB 45, according to the October 2005 valuation, is just under $2�billion. (This consists of $634�million in annual normal costs for retiree health benefits earned each year and more than $1.3�billion in annual costs to amortize Maryland�s existing unfunded liabilities.)

Ohio: Already Prefunding Some Retiree Health Liabilities. The State of Ohio generally has been recognized as a leader in addressing retiree health liabilities. A portion of public employers� retirement system contributions is set aside for funding of retiree health care. The system�s actuarial accrued liability for retiree health and similar benefits was pegged at $19�billion, as of December 31, 2002. The Ohio system already has set aside $10�billion to fund these benefits, significantly reducing the unfunded portion of the liability that eventually will be reported under GASB 45.

As discussed above, the state and many other public entities (in California and elsewhere) have made retiree health benefits an important part of the overall compensation package offered to government workers. These benefits, however, have become significantly more costly than they used to be.

Up until recently, policy makers have had little information with which to evaluate key characteristics of retiree health benefit programs. These characteristics include the programs� long-term costs, how benefits compare with the vast array of retiree health plans offered by other governments, and how other public agencies are addressing these costs. The GASB�s new accounting rules will result in important new tools for policy makers to use in evaluating retiree health programs.

Over the next year or two, actuaries and accountants will be the experts making complex calculations concerning the size of GASB 45 liabilities for the state and local governments. Our educated guess is that unfunded retiree health liabilities for state government will total in the range of $40�billion to $70�billion and perhaps more. (This is based on the results of other liability valuations.) The unfunded retiree health liability may exceed the combined unfunded liabilities of CalPERS� and CalSTRS� pension systems-which were $49�billion, as of June 30, 2004.

Using Maryland�s valuation as a potentially comparable example, we can make a rough guess about the state�s annual contribution for retiree health benefits, as defined by GASB 45. This amount might be in the range of $6�billion. This would consist of about $2�billion in normal costs (the value of retiree health benefits estimated to be earned by current employees each year) and around $4�billion more in yearly payments to retire the unfunded retiree health liability over 30 years. Compared to the state�s current funding of $1�billion, the normal costs under this scenario would be about twice the amount the state now spends each year for benefits under a pay-as-you-go system.

We expect that UC, most local governments, and school districts also will obtain actuarial valuations of their retiree health liabilities. Combined, their liabilities could exceed those of the state itself, but there will be significant variation among governments. Some local governments and school districts will have relatively small liabilities and others will have very large ones. (The significant liabilities of the school districts in Los Angeles and Fresno, as an example, are discussed in the nearby box.)

Retiree Health in Two School DistrictsLos Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD). The LAUSD is one of the few districts offering comprehensive lifetime health benefits to its retirees. The LAUSD health program covers 32,000 retirees and 18,000 of their family members. The cost to the district is about $200�million annually. Like the state, LAUSD pays retiree health benefits on a pay-as-you-go basis. Retiree health benefits have grown from 2.6�percent to 3.9�percent of general fund spending since 2001-02. A July 1, 2004 actuarial valuation pegged the unfunded retiree health liability of the district at $4.9�billion. Normal costs-the amount needed to keep the liability from growing-were estimated to be $326 million per year. The actuarial valuation estimated that annual spending of $529�million would be needed to pay off the unfunded liability within 30 years. Currently, this would raise retiree health expenditures by 8�percent of general fund spending. Fresno Unified School District (FUSD). The FUSD had an unfunded retiree health and other benefits liability of approximately $1.1�billion before the district ratified a new agreement with the Fresno Teachers Association in August 2005. Previously, retirees with at least 16.5 years of service received premium-free benefits, which continued as supplemental coverage to Medicare after age 65. The new agreement includes various employee concessions, such as a new requirement for retirees under age 65 to pay the same portion of their benefit costs as active employees-reportedly $40 to $80 per month-and a cap on the amount FUSD will pay in the future for benefits. A group of FUSD retirees has indicated that it may file suit regarding the health benefit changes. The group says it was not invited to participate in negotiations on the new agreement. |

Retiree health benefits, like salaries, are earned during an employee�s working years. The benefits, however, are paid out after retirement. Unless enough funds (with assumed, future investment earnings) are set aside to cover normal costs of benefits while an employee is working, future taxpayers pay all or a part of the costs of the employee�s health care after retirement.

An Example of Shifting Liabilities to Future Generations. For example, take a state employee earning a $25,000 salary in 1985. In addition to this salary compensation, the employee was promised in 1985 that the state would pay 100�percent of his or her health benefits during retirement (if the employee worked at least 20�years). The state, however, did not set aside any funds for those future health costs in 1985 or in any year thereafter. If that employee retires this year, taxpayers of today and the future must pay about $5,000 per year for the employee�s retirement health costs. While these benefits were earned doing work for the prior generation of taxpayers, the current generation of taxpayers will bear the financial burden of paying for them. In the same way, today�s state workforce is earning future retirement health benefits. While paying for current retirees� health costs, the state is not setting aside any money for future costs. The next generation of taxpayers will be left paying this bill. Because health care costs are rising and retirees are living longer than ever before, the future costs will be much higher than the current $5,000 per year. In this way, each generation shifts a growing liability to the next generation.

Current Taxpayers Should Pay for Current Expenses. The state (and nearly every other public entity nationwide) does not pay its current (or normal) costs for retiree health benefits each year. Consequently, the state fails to reflect in its budget the true costs of its current workforce. Since 1961, the state has been shifting costs to future taxpayers. The tens of billions of dollars in unfunded liabilities now owed by the state is the result of this approach. For this reason, the pay-as-you-go approach to retiree health care conflicts with a basic principle of public finance-expenses should be paid for in the year they are incurred. This principle requires decision makers to be accountable-through current budgetary spending-for the costs of whatever future benefits may be promised.

In this section of the report, we:

First discuss the need for the Legislature to take action to ensure that the vast amount of information about retiree health liabilities soon to be released under the new accounting rules is disclosed publicly. By doing so, the Legislature will improve the information available to it (and to local and school district leaders) as these issues are considered over the next few years.

Next, we recommend prefunding retiree health benefits in order to begin addressing the state�s massive unfunded liabilities.

Finally, we discuss a range of options that the Legislature may consider if it wishes to reduce future cost increases in retiree health benefits.

Currently, the Legislature-and other elected officials throughout the state-lack much of the information needed to develop a concrete, long-term strategy for addressing retiree health care liabilities. We recommend the Legislature take several actions to make information on these liabilities easily accessible to policy makers, researchers, and the public. Legislative actions also should promote efforts by governments to plan for payment of future retiree health costs.

Actuarial Valuation. The State Controller has requested $252,000 in the 2006-07 Budget Bill to obtain a retiree health actuarial valuation for the state, consistent with GASB 45�s requirements. The valuation would provide important information for the Legislature on the magnitude of the state�s unfunded liabilities and possible funding options. We recommend approving the State Controller�s funding request.

Inventory of Retiree Health Liabilities Statewide. As state officials begin the process of evaluating state government�s retiree health liabilities, local officials also are beginning the process of complying with GASB 45�s requirements. As discussed earlier, GASB 45 will result in government financial statements having information on retiree health liabilities similar to the information already provided for pension systems.

The State Controller already compiles audited reports of state and local pension systems. We believe it would be valuable to have GASB 45 liabilities publicly disclosed in a similar fashion. For this reason, we recommend enactment of legislation requiring governmental entities in California to submit their actuarial valuations to the State Controller. We also recommend that the State Controller be required to post the valuations on the Internet (if governments choose to submit them electronically) and produce a report annually on retiree health liabilities similar to the one produced on the finances of public pension systems. (Any reimbursable state mandated costs under this proposal should be minimal because local governments voluntarily obtain valuations.)

School District Recommendations. For some school districts, the size of retiree health benefit liabilities will be so large that unless steps are taken soon to address the issue, it seems likely that districts will eventually seek financial assistance from the state. For this reason, we reiterate our recommendations in the Analysis of the 2005-06 Budget Bill (please see page E-50) that the Legislature require county offices of education (COEs) and school districts to take steps to address school districts� long-term retiree health liabilities. Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature enact legislation to require districts to provide COEs with a plan to address retiree health liabilities. We also recommend that the state�s school district fiscal oversight process (the AB 1200 process) be modified to require COEs to review whether districts� funding of retiree health liabilities adequately covers likely costs. We will discuss this issue further in the Education chapter of the upcoming Analysis of the 2006-07 Budget Bill.

UC Recommendations. The UC, independently of the state, negotiates with its employees concerning compensation and retirement benefits. Historically, the Legislature has opted to appropriate funds to UC to cover increased health benefits costs. Like the state, UC is expected to release its own retiree health valuation (under the terms of GASB 45) by 2008. We recommend that the Legislature request UC-upon completion of the valuation-to propose a long-term plan for addressing unfunded retiree health liabilities. Such a plan would provide the Legislature with information regarding the long-term costs of the existing benefits and any measures UC plans to take to lower these costs. Upon receipt of such a plan, the Legislature would be in a much better position to consider whether additional General Fund resources should be provided to address any portion of UC�s future retiree health costs.

Recommend Creation of Working Group on State Retiree Health Funding. Just as we recommend increased planning and disclosure by school districts and UC, we also recommend the state plan for how it might fund retiree health benefits in the future. Consequently, we recommend that the Legislature establish a working group-consisting of representatives from key state agencies-to advance the state�s planning. Tasks for this working group might include consideration of and recommendations concerning: the types of prefunding vehicles available under state law and federal tax law, possible choices for a state agency or other entity to manage these funds, investment guidelines, the viability of issuing bonds to reduce retiree health liabilities, strategies to increase the funding for retiree health benefits paid from federal funds, and options to reduce state costs.

We would suggest that the working group provide an interim report to the Legislature on these subjects by January 1, 2008 and a final report by January 1, 2010-following its consideration of the state�s first actuarial valuation. In considering the valuation, the working group should review the actuarial assumptions used (for health care inflation and retiree mortality, for example). Rosy assumptions about future health care inflation or investment return could result in a valuation that understates the true magnitude of state liabilities by tens of billions of dollars. For this reason, in its final report, the working group should be required to provide its opinions to the Legislature on the valuation�s overall reliability, considering the actuarial assumptions that are used.

As discussed above, the state (and almost all other governmental entities in California) pays for the health benefits of retired employees on a pay-as-you-go basis. This means that retiree health services are funded when retirees use them. The alternative is to prefund benefits.

If the state and other governments were starting from scratch today and offering retiree health benefits for the first time, prefunding could be accomplished by paying the normal costs each year-the estimated amount that needs to be set aside and invested to pay for health services after employees enter retirement. However, since the state and other governments have offered these benefits for decades and have not set aside funds, they would have to pay considerably more to fully prefund all benefits. As noted previously, GASB 45 requires the calculation of a full prefunding annual contribution consisting of: (1) estimated normal costs and (2)�an amount needed to retire the unfunded liability for unpaid past normal costs within 30 years.

Prefunding Is the Approach Used for Pension Systems. Prefunding is the approach the state uses for its current pension systems. The board of CalPERS, for example, requires the state to pay an amount each year that is set aside and invested to prefund future retiree benefits. This annual amount paid to CalPERS is similar to the full prefunding annual contribution that will be calculated under GASB 45.

There is virtually no dispute that prefunding is the best way to fund a pension system. The Legislature-and California�s voters-have mandated a prefunding policy for state employee pensions for decades. In 1947, the Legislature adopted a prefunding policy for state employee pensions. At that time, the Legislature enacted laws that began to require actuarially determined contributions to the Public Employees� Retirement Fund. In 1972, the Legislature passed a statute that began to prefund CalSTRS pension benefits under a long-range plan.

Reasons to Prefund Retiree Health Benefits. As noted earlier, a pay-as-you-go approach to funding retiree health benefits is problematic in that it shifts current costs to future taxpayers. The alternative-prefunding benefits-not only avoids this problem, but also results in the following:

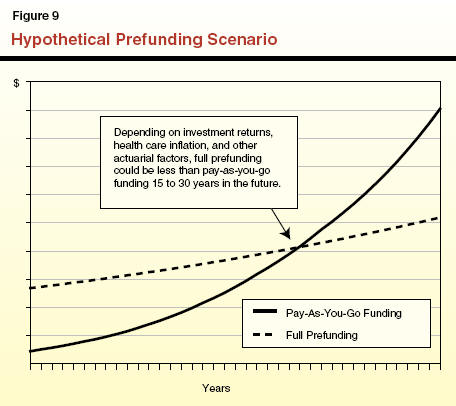

More Economical Over Time. Over the long term, investment earnings would supplement state and any employee or retiree contributions for retiree health costs. This would allow the state to pay for a given level of benefits with fewer budgetary resources and retire unfunded liabilities for retiree health care. Figure�9 illustrates the long-term benefits of fully prefunding retiree health benefits by contributing the full annual contributions (normal costs and costs to retire unfunded liabilities) specified by GASB 45. Paying more now can dramatically reduce costs over the long term.

Helps Secure the Benefits Expected by Employees. Prefunding creates a pool of assets with which to support future benefits that public employees expect to receive. These assets would strengthen the state�s ability to provide these benefits over the long term.

Contributes to Higher Bond Ratings. Bond rating agencies, whose evaluations help determine the interest rates paid on state debt, monitor the funding status of the retiree health program. There is no indication that rating agencies will rush to downgrade ratings once GASB 45 reveals large retiree health liabilities. However, unfunded pension and retiree health obligations are viewed by bond analysts as similar to debt. For rating agencies and bond investors, more debt can be a negative consideration. As more states and local governments address retiree health liabilities, rating agencies may compare those governments that have acted with others that have not.

Partially Prefunding Retiree Health Benefits Is an Option. As noted earlier, our rough guess of the state�s cost for full prefunding under GASB 45 is in the range of $6�billion annually. That amount would cover the future costs of today�s employees, plus pay off the state�s unfunded liability over 30�years. Clearly, given the state�s budget situation, immediately moving to this level of funding is unrealistic. Another option is funding part of the GASB 45 annual contribution. Any amount of prefunding reduces the exposure of the state to future increases in health costs. Investment earnings from funds set aside today would help reduce future budget pressures.

LAO Recommendation. For the reasons discussed above, we recommend that the Legislature-after receiving the state�s actuarial valuation-begin partially prefunding retiree health benefits. Recognizing the state�s current fiscal condition, we recommend that the state ramp up to an increased level of contributions over a period of several years. The near-term target should be the state�s normal cost level under GASB 45-the amount estimated to cover the cost of future retiree health benefits earned each year by current employees. This amount might be in the range of about $1�billion above what the state spends under the current pay-as-you-go approach. Funding a minimum of the normal cost each year would help reduce the burden of future taxpayers to pay for benefits earned today. Over the much longer term, the state could then begin to address the unfunded liability that has been accumulated over the past half century.

The Legislature and other public policy makers-confronted with an accurate accounting of the long-term costs of retiree health benefits under GASB 45-may wish to consider options to reduce costs. In this section, we discuss such options. Some options would allow continuation of current benefit levels, but perhaps require that employees or retirees bear more of the costs of the benefits. Other options involve reduced benefits.

Whether the Legislature would want to pursue these options would depend on a variety of factors, such as: (1) the desired level of compensation provided to state employees, (2) the amount of the unfunded liability, and (3) other funding priorities. Consequently, at this point, we make no recommendations as to these options.

For Current and Past Employees, Options May Be Limited. The ability of companies and governments to cut retiree health benefits for current and past workers is an evolving area of law, according to sources we consulted during our research. To the extent that the state has promised employees-in statute, collective bargaining agreements, or elsewhere-that it will pay a portion of their health care during retirement as deferred compensation, these benefits may be a vested contractual right of the employee, just as pensions are. The Legislature may have little or no ability to unilaterally alter such vested benefits.

For Future Employees, Extensive Options. The Legislature has much more extensive options within the law to reduce or alter retiree health benefits for employees that begin state service in the future. There are many such options, including:

Changing the current 100/90 formula for retiree health benefits for future hires and their dependents.

Increasing the share of retiree health benefit costs paid by employees (during their working years) and retirees (through premiums, copayments, deductibles, and similar mechanisms).

Raising the number of years required to vest in retiree health benefits.

Establishing a defined contribution program, to which the state would agree to contribute a set amount of money. This would eliminate the risk of unfunded state liabilities, but shift financial risk to retirees.

These types of actions would reduce the state�s normal costs for retiree health benefits. Reducing benefits for future hires, however, would not change the unfunded liability already incurred for current and past state employees. Moreover, if the state continued paying for retiree health benefits on a pay-as-you-go basis, changing benefits for future hires would only result in savings decades into the future.

Reducing state costs by taking the types of actions discussed above may create a �two tier� system of retiree benefits (where one group of state retirees receives a richer benefit package than the other). Such systems can be difficult to administer and can cause conflicts between groups of employees and retirees. In addition, since providing retiree health benefits has been an important component of the state�s compensation package for its employees, actions to significantly reduce these benefits could affect the state�s ability to recruit and retain employees in the future without offsetting compensation increases.

Unfunded retiree health care liabilities of the state and other public agencies in California are significant, and over the next several years, these liabilities will be quantified by actuaries and accountants pursuant to GASB 45. Because of the recent, rapid rise of health care costs, this category of state liabilities has been growing very rapidly in recent years. Figure�10 summarizes our recommendations for the Legislature to develop a strategy that will begin to address these unfunded liabilities and reduce costs imposed upon future taxpayers.

|

Figure 10 Summary of LAO Findings and Recommendations On Retiree Health Liabilities |

|

|

|

» Unfunded Liabilities |

|

State government retiree health liabilities are likely $40 billion to $70 billion and perhaps more. |

|

Combined liabilities for the University of California (UC), local governments, and school districts could exceed those of state government. |

|

» More Disclosure and Planning |

|

Recommend approving State Controller's request for $252,000 in 2006‑07 to obtain a retiree health actuarial valuation for the state, consistent with GASB 45. |

|

Recommend requiring public entities choosing to obtain valuations to submit them to the State Controller. |

|

Recommend requiring State Controller to report on retiree health benefits, costs, and liabilities statewide. |

|

Recommend requiring school districts to develop plans to address retiree health liabilities. |

|

Recommend requesting UC to propose a plan to address its retiree health liabilities. |

|

Recommend establishing state working group to report to the Legislature on options for funding and reducing costs of retiree health benefits. |

|

» Funding Retiree Health Benefits |

|

Recommend beginning to partially prefund retiree health benefits after receipt of state's retiree health actuarial valuation, ramping up to an increased level of contributions over several years. |

|

» Options to Reduce Future Retiree Health Costs |

|

Extensive options exist to reduce costs for state employees hired in the future. |

|

For costs related to current and past employees, options may be limited. |

|

Acknowledgments This report was prepared by Jason Dickerson and reviewed by Michael Cohen. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814. |

Visit the LAO's Retiree Health Care News and Reports Web Site