January 22, 2007

Implementing the 2006 Bond Package:

Increasing Effectiveness Through Legislative Oversight

(Note: This report was reprinted in our Analysis of the

2007-08 Budget Bill, published February 21st, 2007. In that

publication we

added a section

related to the Governor's January 24, 2007

executive order intended to increase governmental accountability

and public information about the use of the November 2006

bonds.)

Contents

Introduction

Section 1: Overview

Section 2: Transportation

Section 3: Resources

Section 4: Housing

Section 5: K-12 School Facilities

Section 6: Higher Education

In November 2006, California voters approved $42.7 billion in general obligation bonds to fund infrastructure projects in transportation, education, resources, and housing. The 2006 bond package represents a major opportunity for the Legislature to address many of the state’s most pressing infrastructure concerns. With more than $18 billion allocated to new programs, effective legislative oversight is critical to the success of the programs. In this report, we offer key considerations and recommendations to assist the Legislature in implementing the bonds.

|

Executive Summary |

|

|

|

ü

November 2006 Bond Package Provides

$43 Billion for Infrastructure |

|

·

Five bonds span transportation

($19.9 billion), housing ($2.9 billion), education

($10.4 billion), flood control ($4.1 billion), and

resources ($5.4 billion). |

|

·

The bonds provide the state with a

major opportunity to make infrastructure investments

that will last for a generation or more. |

|

ü

Bonds Fund 67 Different Programs |

|

·

Each of the 67 pots of money has its

own purpose and administering department. |

|

·

More than $18 billion is allocated to

21 new programs. The remaining $25 billion is for

existing programs. |

|

ü

Governor Proposes More Than

$11 Billion in Spending |

|

·

Of the bond proceeds, the

administration proposes spending $2.8 billion in

2006‑07 and an additional $8.7 billion in 2007‑08.

|

|

·

Governor proposes an additional

$29 billion in bonds be put before the voters in

2008 and 2010. |

|

ü

Paying Off the Bonds Will Have to

Fit Into the State’s Long-Term Budget Plan |

|

·

To pay off these bonds over the next

30 years, the state will pay an additional

$41 billion in interest. |

|

·

We estimate that the state’s debt

burden will rise to a peak of 5.6 percent of annual

revenues in 2010‑11. Adding in the Governor’s

proposed new bonds, the burden would rise to a peak

of 6.1 percent in 2014‑15. |

|

ü

Legislature Should Take an Active

Oversight Role to Ensure Accountability |

|

·

In designing the framework for new

programs, the Legislature should emphasize long-term

benefits and statewide priorities. A program’s goals

and the criteria for selecting projects should be

clearly defined. |

|

·

The Legislature can add additional

oversight by rejecting the use of continuous

appropriations, limiting administrative costs, using

special committees and joint hearings, and requiring

and reviewing annual reports. |

|

ü

Desire to Distribute Funds Quickly

Should Be Balanced With Practical Considerations |

|

·

Bond spending will have a modest

effect on the overall state economy. |

|

·

Limits on staff, materials, and the

readiness of high-quality projects will require

spending over multiple years. |

|

ü

Coordination Among State Entities

Needed |

|

·

At least two dozen state entities will

be involved in implementing the bond programs. |

|

·

Some of the programs cut across

traditional state departmental boundaries. The

Legislature should ensure that the proper

coordination and planning between departments is

taking place. |

Introduction

In November 2006, California voters approved five propositions which authorize $42.7 billion in general obligation (GO) bonds. The bonds cover a range of purposes, including transportation, education, resources, and housing. The bond package represents a major commitment by the Legislature, Governor, and the voters to improve the state’s infrastructure.

The large infusion of bond proceeds provides the state with a major opportunity to make infrastructure investments that will last for a generation or more. At the same time, in overseeing the implementation of the bonds, the Legislature faces several challenges. The bonds provide funding to many new programs for which goals and allocation criteria have yet to be established. The way in which these programs are crafted by the Legislature will help determine the level of the bonds’ success. In addition, ongoing legislative oversight of all of the funding would increase accountability and increase the likelihood of positive outcomes. This report aims to assist the Legislature in implementing the 2006 bond package. It offers key considerations and recommendations to the Legislature to help ensure the bond proceeds are used effectively and efficiently.

Organization of This Report. This report has six sections:

-

“Section 1” provides an overview of the bonds, the programs funded, and their long-term financing costs. This section also broadly summarizes the Governor’s proposals for implementing the bonds. The section then discusses key implementation issues that cut across more than one of the bonds.

-

“Sections 2 through 6” provide a program area by program area look at the bonds. In each section (transportation, resources, housing, K-12 education, and higher education), we provide a deeper look at the key issues facing the Legislature. We cover the Governor’s proposals in more detail, discuss specific programs which need attention by the Legislature, and make various recommendations regarding program implementation.

Section 1: Overview

The Bond Package

The 2006 bond package approved by the voters in November provides $42.7 billion for infrastructure spending. The package included five propositions spanning transportation (Proposition 1B), housing (Proposition 1C), education (Proposition 1D), and resources (Propositions 1E and 84).

Interest Costs. As GO bonds, the spending authorized will need to be paid back, with interest, from the state’s General Fund over time. In recent years, GO bonds have been paid off over a 30-year period. Since they are backed by the state’s general taxing power and generally exempt from taxation under federal law, the bonds tend to be sold with the lowest interest rate compared to other types of borrowing. In the voter information guide for the November 2006 election, we assumed most of the bonds would be sold at an average interest rate of 5 percent. (Proposition 1C, the housing bond, will have higher interest rates since a portion of the bonds are not eligible for the federal tax exemption.) Figure 1 summarizes the five bonds and the interest payments that we estimate will be made over the life of the bonds. The interest payments will almost double the costs of the bonds over their life-for a total cost of $84 billion.

|

Figure 1

Long-Term Costs of the 2006 Bond Packagea |

|

(In Billions) |

|

|

Principal |

Interest |

Totals |

|

Proposition 1B—Transportation |

$19.9 |

$19.0 |

$38.9 |

|

Proposition 1C—Housing |

2.9 |

3.3 |

6.2 |

|

Proposition 1D—Education |

10.4 |

9.9 |

20.3 |

|

Proposition 1E—Flood Control |

4.1 |

3.9 |

8.0 |

|

Proposition 84—Resources |

5.4 |

5.1 |

10.5 |

|

Totals |

$42.7 |

$41.2 |

$83.9 |

|

|

|

a LAO

state voter pamphlet estimates, November 2006. |

Many Pots of Money. Within the five bond measures, there are many specified allocations of funds. In total, there are 67 pots of money included in the five bonds. The smallest such pot of money is in the housing bond and provides $10 million for self-help construction grants to organizations which assist households in building or renovating their own homes. In contrast, the largest pot of money is in the transportation bond and provides $4.5 billion for corridor mobility to reduce congestion on state highways and major access routes. Each pot of money has its own purpose, administering department, and restrictions (if any) on its use. Many different state departments will be involved in the implementation and allocation of the bonds. Figure 2 summarizes the broad categories of funding within each bond. In each of the individual program area writeups later in this report, there is a figure which provides a description of each of the 67 pots of funds.

|

Figure 2

Allocations of 2006 Bond Package |

|

(In Millions) |

|

Program |

Funding |

|

Proposition 1B—Transportation |

$19,925 |

|

Congestion Reduction, Highway

and Local Road Improvements |

$11,250 |

|

Transit |

4,000 |

|

Goods Movement and Air Quality |

3,200 |

|

Safety and Security |

1,475 |

|

Proposition 1C—Housing |

$2,850 |

|

Development Programs |

$1,350 |

|

Homeownership Programs |

625 |

|

Multifamily Housing Programs |

590 |

|

Other Housing Programs |

285 |

|

Proposition 1D—Education |

$10,416 |

|

K-12 |

$7,329 |

|

Higher Education |

3,087 |

|

Proposition 1E—Flood

Control |

$4,090 |

|

|

|

|

Proposition 84—Resources |

$5,388 |

|

Water Quality |

$1,525 |

|

Protection of Rivers, Lakes,

and Streams |

928 |

|

Flood Control |

800 |

|

Sustainable Communities and

Climate Change Reduction |

580 |

|

Protection of Beaches, Bays,

and Coastal Waters |

540 |

|

Parks and Natural Education

Facilities |

500 |

|

Forest and Wildlife

Conservation |

450 |

|

Statewide Water Planning |

65 |

|

Total |

$42,669 |

Existing Versus New Programs. Some pots of funding provide state programs with additional resources. Many of these existing programs also have funds remaining from prior bond authorizations. In total, we estimate that almost $5 billion in prior bond funds have not yet been spent on these programs. (As noted in our K-12 discussion, there is an additional $4 billion available for an overcrowded schools program that was replaced with a new program in Proposition 1D.) In other cases, a pot provides dollars for a purpose never previously funded. In these cases, the program purpose at this point may be defined only by a few sentences. As shown in Figure 3, the bond package funds 21 new programs, representing more than 40 percent of total funding. Many of these new programs will need further implementing legislation in order to begin operating.

|

Figure 3

2006

Bond Package Funds

Existing and New Programs |

|

(Dollars in Billions) |

|

|

Number |

Funding |

|

Existing programs |

46 |

$24.5 |

|

New programs |

21 |

18.2 |

|

Totals |

67 |

$42.7 |

Appropriations. Most of the programs will need future legislative action to appropriate funding-either through the annual budget bill or separate legislation-before state departments can begin spending the funds. In some cases, the funds are continuously appropriated-meaning that funding obligations can be made by departments without additional legislative action. These continuous appropriations cover $9.4 billion of the bond funding. They apply to all K-12 education programs, a number of housing programs, and several pots within Proposition 84.

Governor’s

Proposal

In this section, we provide an overview of the Governor’s approach to implementing the 2006 bond package, as outlined in the Governor’s proposed 2007-08 budget. In the specific policy area sections that appear later in this report, we provide a more detailed description of these proposals.

Proposed

Expenditures for 2006-07 and

2007-08

As shown in Figure 4, the Governor is proposing to spend $11.5 billion of the bond funds by the end of 2007-08-or slightly more than one-quarter of the total available. Of this proposed spending, roughly $8.9 billion would be used for existing programs while $2.6 billion would be for new programs.

|

Figure 4

Governor’s Proposed Spending Plan for

2006 Bond Package |

|

(In Millions) |

|

Program |

2006‑07 |

2007‑08 |

Future Years |

|

Proposition 1B—Transportation |

|

|

|

|

Congestion reduction, highway

and local road

improvements |

$503 |

$1,858 |

$8,889 |

|

Transit |

— |

600 |

3,400 |

|

Goods movement and air quality |

15 |

267 |

2,918 |

|

Safety and security |

5 |

64 |

1,406 |

|

Proposition 1C—Housing |

|

|

|

|

Development programs |

— |

$228 |

$1,122 |

|

Homeownership programs |

$35 |

129 |

461 |

|

Multifamily housing programs |

105 |

236 |

249 |

|

Other housing programs |

20 |

67 |

198 |

|

Proposition 1D—Education |

|

|

|

|

K-12 |

$985 |

$2,142 |

$4,202 |

|

Higher Education |

1,056 |

1,359 |

672 |

|

Proposition 1E—Flood Control |

— |

$624 |

$3,466 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Proposition 84—Resources |

|

|

|

|

Water quality |

— |

$263 |

$1,262 |

|

Protection of rivers, lakes,

and streams |

— |

245 |

683 |

|

Flood control |

— |

276 |

524 |

|

Sustainable communities and

climate change

reduction |

— |

31 |

549 |

|

Protection of beaches, bays,

and coastal waters |

— |

131 |

409 |

|

Parks and natural education

facilities |

— |

25 |

475 |

|

Forest and wildlife

conservation |

$60 |

119 |

271 |

|

Statewide water planning |

— |

15 |

50 |

|

Totals |

$2,784 |

$8,679 |

$31,206 |

Current-Year Expenditures. Of the Governor’s proposed expenditures, $2.8 billion would be spent in the current year. In the case of the $1.1 billion for higher education, the Legislature appropriated these amounts in the

2006-07 Budget Act, with the assumption that Proposition 1D would be passed by the voters. In other cases, such as the $985 million for K-12 education facilities, $160 million for existing housing programs, and $60 million from Proposition 84, the funding is continuously appropriated and became available for spending upon the passage of the bonds. Regarding the $523 million in proposed transportation spending for the current year, however, the Legislature would need to enact urgency legislation to appropriate the funds if it wished to adopt the administration’s planned timing.

Budget-Year Expenditures. The Governor proposes spending $8.7 billion in 2007-08. In some cases, the administration proposes new staffing and statutory language to help implement the programs. In other cases, however, the Governor’s budget does not include any such requests despite a program being funded for the first time. While this proposed spending covers most of the programs authorized by the bond package, the Governor’s plan does not include spending for seven pots of funding, primarily for new programs.

Bond Package in the Context of the

State Infrastructure Plan

Five-Year Plan Required. Chapter 606, Statutes of 1999 (AB 1473, Hertzberg), requires the Governor to annually submit to the Legislature a five-year infrastructure plan in January in conjunction with the submission of the Governor’s budget. The plan is required to identify new and renovated infrastructure requested by state agencies (including higher education), and aggregate funding for transportation and K-12 education. Additionally, the plan is required to provide a cost estimate and a specific funding source for the infrastructure projects identified. Thus, the plan represents the administration’s funding priorities for infrastructure improvements across all departments and programs.

Plan Not Submitted on Time. The administration did not submit a 2007 infrastructure plan this month. Instead, the administration reports that it plans to submit it on March 1, 2007. As such, it is difficult to assess precisely how the $43 billion bond package meets the state’s current overall infrastructure needs from the administration’s perspective. However, the administration’s 2006 plan identified total state infrastructure costs of $90 billion through

2010-11. Clearly, the 2006 bond package significantly increases the amount of funding available to address that $90 billion total. Yet, the two numbers are not directly comparable. The bond package funds a number of programs and purposes not envisioned within the administration’s five-year plan. For instance, the entire $2.9 billion in spending authorized by the housing bond was not identified as a state priority by the administration last year.

Governor Proposes Additional Borrowing. While the 2006 bond package made a sizable commitment to the state’s infrastructure, it did not address all aspects of the state’s infrastructure demands. For instance, the package contained no funding in the criminal justice area. In addition, areas that were funded by the bonds have identified additional demands. For example, Proposition 1D funds for education are expected to fund programs through only 2008-09. In recognition of these limitations, the Governor has proposed additional long-term borrowing as part of his 2007-08 budget package (presented as a second phase to his Strategic Growth Plan). The Governor proposes additional GO bonds totaling $29.4 billion to be put before the voters in 2008 and 2010 (see Figure 5). Of this amount, the vast majority-$23.1 billion-would be for education purposes. Education funding would be split about evenly between K-12 and higher education programs. Most of the remaining funds would be for water development projects ($4 billion) and court facilities ($2 billion). In addition, the Governor proposes the use of lease-revenue bonds totaling $11.9 billion-primarily for corrections and local jails. As with GO bonds, costs for lease-revenue bonds are paid off with General Fund revenues.

|

Figure 5

Approved and Proposed General Obligation Bonds |

|

2006 Through 2010

(In Billions) |

|

|

Approved

2006 |

Proposed

2008 and 2010 |

Totals |

|

Transportation |

$19.9 |

— |

$19.9 |

|

K-12 Education |

7.3 |

$11.6 |

18.9 |

|

Higher Education |

3.1 |

11.5 |

14.6 |

|

Flood control and water |

4.9 |

4.0 |

8.9 |

|

Resources |

4.6 |

— |

4.6 |

|

Housing |

2.9 |

— |

2.9 |

|

Courts and other |

— |

2.3 |

2.3 |

|

Totals |

$42.7 |

$29.4 |

$72.1 |

Our office’s review of the programmatic features of the new proposals is outside the scope of this report. Please see our forthcoming

Analysis of the 2007-08 Budget Bill (to be released February 21) for a discussion of these new infrastructure proposals. In order to assist the Legislature, however, with questions concerning the affordability of additional bonds, we do discuss their fiscal implications in the section which follows.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

Below, we raise a number of issues that the Legislature will need to consider as it makes its decisions this year regarding implementing the bond package.

Costs and Affordability of the Bonds

Bond Costs and the Budget. Faced with ongoing budget shortfalls, as well as the administration’s proposals for additional borrowing, the Legislature will want to consider how infrastructure borrowing fits into the state’s budget plan. The cost of the 2006 bond package in the next few years-and its impact on the state’s budget-will depend primarily on the timing of bond sales, bond maturity structures, and the bonds’ interest rates. In turn, the overall affordability of the package will depend on how its costs affect the state’s future debt-service expenses-including costs for bonds that have already been sold, yet-to-be-sold bonds authorized prior to the November 2006 election, and any future bond authorizations. For example, in addition to the 2006 bond package, the state currently has about $37 billion of bonds outstanding on which it is making principal and interest payments, and another $25 billion in unsold bonds that voters have already approved for various purposes.

Key Assumptions. Our cost projections are generally based on the administration’s assumptions about the timing of bond sales. These assumptions suggest annual bond sales from

all authorizations totaling over $10 billion in 2007-08, rising to a peak of nearly $16 billion in 2009-10. Our projections also assume:

- Maximum maturity lengths for GO bonds and lease-revenue bonds of

30 years and 25 years, respectively.

- GO bond interest rates of 4.5 percent currently, trending up over time to 5.7 percent, with lease-revenue bonds slightly higher.

Debt-Service Amounts. We currently estimate that the state’s annual debt-service costs for infrastructure-related debt outside of the November 2006 package amounted to $3.9 billion in 2005-06, and will be $4.1 billion in

2006-07 and $4.6 billion in 2007-08. These costs will peak at $5.4 billion in 2010-11 as additional already-authorized bonds are marketed, and then decline slowly thereafter as the bonds are paid off over their lifetime. When the bonds approved in November are included, total annual debt service is projected to rise from $4.7 billion in 2007-08 to a peak of $7.5 billion in 2014-15. Finally, when the additional GO and lease-revenue bonds proposed by the administration are included, debt service would peak at $10.4 billion in 2017-18.

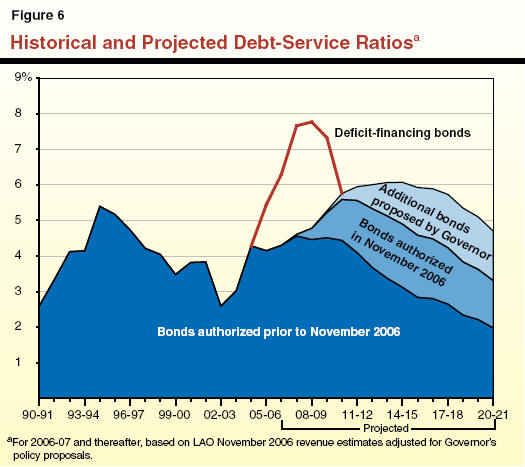

Debt-Service Ratio. The ratio of annual debt-service costs to yearly revenues (DSR) is often used as a general indicator of a state’s debt burden. The DSR helps to look at debt from the perspective of affordability, as it takes into account the amount of revenues the state has available or is projected to have available to fund its programs (including debt payments).

Although concerns have sometimes been voiced in the past about DSRs in excess of 5 percent or 6 percent, there is no “right” level for the DSR. Rather, this depends on such things as a state’s preferences for infrastructure versus other priorities, and its overall budgetary condition. Some states, for example, have comparatively high DSRs but still experience favorable bond ratings. Examples include Maryland, New York, New Jersey, and Illinois.

From an affordability perspective, however, each additional dollar of debt service out of a given amount of revenues comes at the expense of a dollar that could be allocated to some other program area. Thus, the “affordability” of more bonds has to be considered not just in terms of their marketability and the DSR, but also whether their dollar amount of debt service can be accommodated on both a near- and long-term basis within the state budget. (As a rule of thumb, each $1 billion of new bonds sold at 5 percent interest adds close to $65 million annually to state debt-service costs for as long as 30 years.)

LAO Debt-Service Projections. Figure 6 shows California’s DSR in recent years and its projected outlook for the future. The DSR was well under 2 percent during most of the post- World War II period, increased in the early 1990s when it peaked at somewhat over 5 percent, and then fell below 3 percent in the early 2000s. It has since risen as new bond authorizations have been sold, and would peak at 4.6 percent in 2007-08 without the November 2006 bonds. Including the November bonds, the DSR is projected to peak at 5.6 percent in 2010-11. Finally, including the new GO and lease-revenue bonds proposed in the Governor’s budget, the DSR would peak at 6.1 percent in 2014-15. On top of these amounts are the payments the state is making on the deficit-financing bonds (Proposition 57) that were issued to help address the state’s ongoing budget problems, and which the administration is proposing to pay off during 2009-10.

Ensuring Adequate Legislative Oversight And Accountability

- The Legislature’s role in implementing the bond package is to provide:

- A statutory framework to effectively administer and distribute the funds.

- Appropriations of the funds.

- Oversight to ensure the programs are then administered in accordance with the Legislature’s and the voters’ intent.

This legislative role can help ensure that the $43 billion infusion of funding to the state is implemented with accountability and transparency.

Developing New Programs. Since the bonds commit $18.2 billion to new programs, one of the most important tasks for the Legislature will be to effectively design the frameworks for these new programs. Figure 7 lists each of the 21 new programs.

|

Figure 7

Many New Programs Funded by

2006 Bond Package |

|

(In Millions) |

|

Program |

Funds |

|

Proposition 1B—Transportation |

|

|

Corridor mobility |

$4,500 |

|

Local transit |

3,600 |

|

Trade corridors |

2,000 |

|

Highway 99 |

1,000 |

|

State-Local Partnership grants |

1,000 |

|

Air quality |

1,000 |

|

Transit security |

1,000 |

|

School bus retrofit |

200 |

|

Port security |

100 |

|

Proposition 1C—Housing |

|

|

Development in urban areas |

$850 |

|

Development near public

transportation |

300 |

|

Parks |

200 |

|

Pilot programs |

100 |

|

Homeless youth |

50 |

|

Proposition 1D—Education |

|

|

Severely overcrowded schools |

$1,000 |

|

Career technical facilities |

500 |

|

Environment-friendly projects |

100 |

|

Proposition 84—Resources |

|

|

Local and regional parks |

$400 |

|

San Joaquin River restoration |

100 |

|

Urban water and energy

conservation |

90 |

|

Incentives for conservation

planning |

90 |

|

Total Funding |

$18,180 |

- Long-Term Benefit.

Current law essentially requires that GO bonds be used only

for capital purposes which have a long-term life. The

principle behind this law is that the state should not

conduct long-term borrowing for costs that only provide

short-term benefits, such as day-to-day maintenance or

operations costs. If, instead, bond proceeds were used for

short-term benefits, it would mean that taxpayers three

decades from now would be paying for the short-term benefits

enjoyed by today’s California residents. In developing new

programs, we recommend that the Legislature strongly enforce

the principle that bond proceeds should only support

projects that will provide a long-term benefit to the state.

- Criteria and Priorities.

Another important consideration in establishing a new

program is to ensure that the funding will reflect statewide

priorities. The best way to accomplish this goal is to lay

out in state law the program’s goals and the criteria for

selecting projects which meet those goals. By defining who

is eligible for the funds and what are the program’s

priorities, grant recipients will have a fair opportunity to

compete for funding. After allocations are made, the

Legislature can use these statutory criteria to verify that

the administering state department’s process met legislative priorities.

Appropriations. The “power of the purse”-appropriation authority-is one of the Legislature’s most powerful tools to ensure accountability. Without an appropriation, the administration cannot spend bond funds. Therefore, the Legislature should not appropriate funds until it is satisfied that the administration will spend them effectively. On the other hand, continuous appropriations provide minimal opportunities to ensure legislative oversight. Departments can spend continuously appropriated funds without any further action by the Legislature. While continuous appropriations may be appropriate in some circumstances, we recommend that the Legislature not add any new continuous appropriations to the bond programs. In addition, a continuous appropriation does not preclude the Legislature from instead including the appropriation in the budget bill “in lieu” of the continuous appropriation. As described in the resources section, we recommend that the Legislature take this approach for Proposition 84 programs with continuous appropriations.

Limiting Administrative Costs. Each dollar spent on administrative costs within a bond program is one less dollar that is available for infrastructure projects. The Legislature therefore should make every effort to ensure that administrative costs are contained to the greatest extent possible. By actively reviewing requests from the executive branch for staff and other administrative costs, the Legislature likely can increase the funds available for grants and projects. We have recommended in the past that no more than 5 percent of a program’s funding should go towards administrative costs in the resources and housing areas. That level of administrative funding for competitive grant programs is typically sufficient to provide enough state staff to effectively manage a program. (A strict cap on administrative costs may not make sense in every program area, particularly in those areas where the state is responsible for designing and constructing capital outlay projects such as the California Department of Transportation [Caltrans].)

Using Special Committees and Reporting. In the past, the Legislature has performed effective oversight of bond and other programs through the use of joint committee hearings and annual reporting requirements. For instance, by holding a hearing that merges both budget and policy committee members and staff (from one house or jointly between the Assembly and Senate), the Legislature may be better able to assess the full fiscal and policy implications of not only its decisions but also those of the administering entities. Similarly, annual reports from state departments can allow the Legislature to monitor the administration’s progress in achieving specific program objectives. Later in this report, we provide specific recommendations in areas where we think these techniques would be effective.

Infrastructure planning and financing is a complex issue because it is related to so many state functions and involves a long-term vision for the state. We have also recommended in the past that the Legislature establish special committees to deal with infrastructure and capital outlay issues. Looking beyond the 2006 bond package, a special policy or joint committee could assist the Legislature in focusing on the state’s long-term infrastructure planning. Such a committee could help the Legislature review the administration’s 2007 five-year plan and the Governor’s latest proposals for additional infrastructure borrowing.

Economic Impacts of the Bond Package

State expenditures on infrastructure can have important positive impacts on the economy in terms of employment, gross state product, and the various components of the tax base, such as personal income, corporate profits, and taxable sales. This is especially true to the extent that California is the origin of the various intermediate materials and supplies used in construction activities. In addition, infrastructure projects themselves can generate significant economic benefits, such as improved transportation networks that facilitate the movement of people and products, flood control projects which enhance property values and make new geographic areas available for business and residential uses, and school facilities that help produce a more educated labor force that in turn eventually enhances economic productivity.

Yet, while the magnitude of the 2006 bond package is substantial, it is only a fraction of the size of the overall economy and construction sector in California. For example, in the near term, the state’s gross domestic product is expected to be about $1.7 trillion and the combined statewide value of residential and nonresidential new building permits is roughly $70 billion (with probably two or three times that amount being the overall contribution of the building sector to the state’s economy once all of the indirect and induced economic activity associated with construction-related activity is considered). In addition, not all of the bond package represents a net increase in infrastructure funding compared to that which would have occurred without the package. Californians have typically passed individual new bond authorizations fairly regularly in past years. Thus, while the bond spending can be expected to have a substantial positive dollar economic impact, its magnitude will probably be modest in the context of the overall economy.

Timing Considerations

In evaluating the Governor’s proposals and developing its own funding schedule, the Legislature will need to balance several factors related to the timing of spending. Of course, there will be a desire to get the newly authorized funding appropriated and distributed quickly. This desire should be balanced with practical considerations that limit the state’s ability to effectively spend the funds in a short time period. In some cases, the Legislature may need to prioritize among the various infrastructure demands.

Personnel and Materials. As the Legislature considers the large level of new resources available from the bonds, it will need to determine the limits of capacity for state personnel to manage the expansion of programs. Particularly in the short term, the state may be unable to recruit, hire, and train a sufficient number of staff in some programs to accommodate a rapid rise in spending. If the work is for architectural or engineering services, the Legislature could make expanded use of contracted services, as permitted by Article XXII of the State Constitution. For instance in the case of Caltrans, without additional contracting out, the department may have to hire as many as 4800 new staff to deliver projects funded by Proposition 1B.

Another similar factor to consider is the effect of billions of dollars of public works projects on the costs of construction crews and materials. In recent years, the state (as well as other governments and private builders) have struggled with rapidly rising construction costs driven by limited supplies of trades workers and construction materials. For example, the cost of concrete has climbed sharply and has added significant costs to many projects. To the extent that the state funds projects more evenly over time, it may be able to partially mitigate this trend.

Quality of Projects. There is also tension between timing of projects and their quality. From past experience, spreading allocations over several funding cycles would likely improve the overall quality of the projects funded through competitive programs. To the extent that more funds are awarded in any given year for a competitive grant program, for instance, lower-score projects would tend to be funded. By spreading the dollars out, there is more time for higher-quality projects to be put together and submit applications. For example, this longer-term approach is proposed by the administration for the ongoing housing programs (as was the case with previous housing bonds).

Coordination Among State Entities Needed

As shown in Figure 8, at least two dozen state entities will be involved in implementing some component of the 2006 bond package. Throughout the package, there are program allocations for purposes that cut across traditional state departmental boundaries. One of the key roles for the Legislature will be ensuring that departments are communicating and coordinating with each other when appropriate. For instance, the new development programs within the housing bond aim to promote urban development, particularly near public transportation. At the same time, the transportation bond provides billions of dollars for transit improvements. As such, without close coordination among the departments administering these funds, the state may miss an opportunity to make both sets of money go further by linking projects and/or timelines. Likewise, both the housing and resources bonds contain funding for parks. While conceivably the state could operate distinct park grant programs in two departments, designating a single department (such as the Department of Parks and Recreation [DPR]) to act as the primary administrator of all park bond funds would likely result in lower administrative costs and more consistent project evaluation.

|

Figure 8

2006

Bond Implementation

Will Involve Many State Entities |

|

|

|

·

Air Resources Board |

|

·

California Conservation Corps |

|

·

California Community Colleges |

|

·

California Housing Finance Agency |

|

·

California School Finance Authority |

|

·

California State University |

|

·

California Transportation Commission |

|

·

California Department of

Transportation |

|

·

Department of Education |

|

·

Department of Fish and Game |

|

·

Department of Health Services |

|

·

Department of Housing and Community

Development |

|

·

Department of Parks and Recreation |

|

·

Department of Water Resources |

|

·

Division of State Architect |

|

·

Ocean Protection Council |

|

·

Office of Emergency Services |

|

·

Office of Public School Construction |

|

·

Resources Agency |

|

·

State Allocation Board |

|

·

State Conservancies (nine) |

|

·

State Water Resources Control Board |

|

·

University of California |

|

·

Wildlife Conservation Board |

In these instances, the Legislature can take a number of steps to ensure that proper coordination and planning between departments is taking place. Holding hearings that cut across traditional program areas, requiring joint implementation plans, and verifying implementation progress are a few of the approaches available to the Legislature.

Rethinking Labor Compliance

Programs (LCPs)

As described below, the Legislature has dedicated considerable resources from past bonds to increase enforcement of the state’s labor wage laws. In implementing the 2006 bond package, the Legislature again will face decisions about which approach to take in this area.

California’s Prevailing Wage Law and LCPs. The state’s prevailing wage law affects most state and local public works projects, including most projects funded by the 2006 bond package. While the Department of Industrial Relations (DIR) is the primary state entity responsible for enforcing the law, the Legislature in recent years has required LCPs to supplement the work of DIR for some bond acts. Using a portion of bond proceeds, LCPs are supposed to educate contractors and subcontractors about wage laws and review and audit payroll records to verify compliance. About 80 percent of LCPs are operated by school districts, with most of the rest operated by third-party contractors.

LCP Reporting and Accountability Appears Weak. Our review of summary data from annual reports filed with DIR by LCPs suggest that the amount of wages recovered for workers by the LCPs-as well as penalties imposed for violations of wage laws-is minor, given the volume of public works contracts that LCPs monitor and the amount spent on administering LCPs. Despite LCPs having a primary role in enforcing compliance for contracts totaling $8.3 billion between 2003 and March 2006 (primarily for education construction), the reports show that the programs only recovered somewhere around $3 million or $4 million of wages, penalties, and forfeitures related to their wage enforcement activities. The LCPs spent about $70 million of state GO bond proceeds and local matching funds during this period. In other words, LCPs spent between $18 and $23 for each $1 of wages, penalties, and forfeitures they report to have recovered. At the same time, these measures of wage recovery activity do not capture any voluntary compliance or reduction of complaints to DIR that may be the result of LCPs’ work.

Legislative Options for Enforcing Prevailing Wage Laws. As discussed earlier, each dollar spent on administrative costs within a bond program is one less dollar that is available for infrastructure projects. In this instance, the $70 million in LCP spending would have been able to fund about 200 new classrooms if it had instead been directed to construction. Because there is weak evidence concerning the effectiveness of LCPs, we recommend that the Legislature consider other options for future prevailing wage enforcement activity, including projects funded by the 2006 bond acts.

- Stronger Oversight of LCPs and a Sunset Date. If the Legislature wishes to extend LCP requirements to 2006 bond act projects, we recommend that it pass legislation requiring DIR to strengthen its oversight of LCPs. More accurate and detailed reporting, the revocation of poor-performing LCPs’ authorizations, and improved training would increase the likelihood of LCPs effectiveness. In addition, any new authorizations for LCPs should include a sunset date (such as December 31, 2008) to allow for a thorough review of their work.

- Increase DIR Enforcement Staff Instead of New LCP Requirements. As an alternative to LCP requirements, the Legislature could expand DIR’s enforcement staff by authorizing the establishment of new positions. An increase in staffing also should be accompanied by specific reporting requirements on the staff’s productivity.

Instead of these options, the Legislature could choose to not authorize any LCPs for the 2006 bond package while maintaining DIR’s enforcement staff that monitors public works projects at current levels (numbering 22). With the same number of staff and a rising number of public works projects, however, this would tend to reduce the level of enforcement possible per project.

Conclusion

The 2006 bond package represents a major opportunity for the Legislature to address many of the state’s most pressing infrastructure concerns. To use the bond funds most effectively and strategically, the Legislature will need to take steps to exercise its oversight role. We lay out a number of key considerations and recommendations to help the Legislature achieve that purpose. These key issues are summarized in Figure 9.

|

Figure 9

Summary of Key Issues in

Implementing the 2006 Bond Package |

|

Overall |

|

ü

Consider how the costs of repaying the

bonds fit into the state's overall budget plan. |

|

ü

In developing new programs, bond

proceeds should only support

projects that will provide a long-term benefit. |

|

ü

Establish program goals and project

selection criteria that reflect

statewide priorities. |

|

ü

Do not add any new continuous

appropriations. |

|

ü

Generally limit administrative costs

in competitive programs to 5 percent. |

|

ü

Use special legislative committees and

departmental reports to fully

assess policy and budget implications. |

|

ü

Recognize bond spending will only have

a modest effect on the overall state economy. |

|

ü

Balance desire to distribute funds

quickly with practical limits on staffing and

materials costs. |

|

ü

Ensure proper coordination and

planning between departments. |

|

ü

Consider other options besides labor

compliance programs to enforce wage laws. |

Section 2: Transportation

Background

In recent years, California has spent about $20 billion annually in state, federal, and local funds to maintain, operate, and improve its multimodal transportation network. These expenditures have been primarily funded on a pay-as-you-go basis from taxes and user fees.

Primary State Fund Sources. There are two primary state revenue sources that have funded transportation programs. First, the state’s 18 cent per gallon excise tax on gasoline and diesel fuel (often referred to as the gas tax) generates roughly $3.4 billion annually. Second, revenues from the state sales tax on gasoline and diesel fuel provide about $2 billion a year. Additionally, the state imposes weight fees on commercial trucks, which generate roughly $950 million a year. Generally, these revenues must be used for specific transportation purposes, including improvements to highways, streets and roads, passenger rail, and transit systems.

Bonds Have Played a Limited Role in State Transportation Funding. Since 1990 (and prior to Proposition 1B), voters have approved $5 billion in state GO bonds to fund transportation-less than 5 percent of the total investment in transportation over that period. These bond proceeds have been dedicated to passenger rail and transit improvements, as well as retrofit of highways and bridges for earthquake safety. As of November 2006, only $350 million of these bonds remain unissued and most of these funds are committed to specific projects.

Federal and Local Funds. In addition to state funds, California’s transportation system receives federal and local money. The state receives roughly $4.6 billion a year in federal transportation funds. Collectively, local governments invest about $9.5 billion a year into California’s highways, streets and roads, and transit systems. Local governments have also issued bonds backed mainly by local sales tax revenues to fund transportation projects.

Major Provisions of Proposition 1B

Allocation of Funds. Proposition 1B, the

Highway Safety, Traffic Reduction, Air Quality, and Port Security Bond Act of 2006, approved by voters at the November 2006 election, provides $20 billion in GO bond funds for projects to relieve congestion, facilitate the movement of goods, improve air quality, and enhance the safety and security of the transportation system. Figure 10 details the purposes for which the bond money can be used. The bonds will provide a major one-time infusion of state funds into the transportation system to be spent over multiple years.

|

Figure 10

Proposition 1B

Uses of Bond Funds |

|

|

Amounts

(In Millions) |

|

Congestion Reduction, Highway and

Local Road Improvements |

$11,250 |

|

Corridor mobility: reduce

congestion on state highways and major access

routes. |

$4,500 |

|

State Transportation

Improvement Program: increase capacity on highways,

roads, and transit. |

2,000 |

|

Local roads: enhance capacity,

safety, and operations. |

2,000 |

|

Highway 99: enhance capacity,

safety, and operations. |

1,000 |

|

State-Local Partnership:

grants to match locally funded transportation

projects. |

1,000 |

|

State Highway Operations and

Protection Program: rehabilitate and improve

operation of highways and roads. |

750 |

|

Transit |

$4,000 |

|

Local transit: purchase

vehicles and right of way. |

$3,600 |

|

Intercity rail: purchase

railcars and locomotives for state system. |

400 |

|

Goods Movement and Air Quality |

$3,200 |

|

Trade

corridors: improve movement of goods on highways and

rail, and in ports. |

$2,000 |

|

Air quality: reduce emissions

from goods movement activities. |

1,000 |

|

School bus retrofit: retrofit

and replace polluting vehicles. |

200 |

|

Safety and Security |

$1,475 |

|

Transit security: improve security and facilitate

disaster response. |

$1,000 |

|

Grade separation: grants to

improve railroad crossing safety. |

250 |

|

Local bridges: grants to

seismically retrofit local bridges and overpasses. |

125 |

|

Port security: grants to

improve security and disaster planning in publicly

owned ports, harbors, and ferry facilities. |

100 |

|

Total |

$19,925 |

Bond Act Creates Several New Programs, Involves Many Implementing Entities. As shown in Figure 11 (see page 18), $5.5 billion (28 percent) of the $20 billion in Proposition 1B funding are directed to existing state and local transportation programs, while the majority of the bond revenues-$14 billion (72 percent)-will be used to create new programs. Some of these new programs-including Trade Corridors, Port Security, and Transit Security-address goods movement and security issues that have not historically been a focus of state transportation funding.

|

Figure 11

Proposition 1B Programs

Implementing Agencies and Oversight |

|

Programs |

Implementing Agency |

Oversight

Report/Audit |

Funding

(In Billions) |

|

New |

|

|

$14.4 |

|

Corridor mobility |

CTCa |

Annual report |

$4.5 |

|

Local transit |

Local transit operators |

None specified |

3.6 |

|

Trade corridors |

CTC |

Annual report |

2.0 |

|

Highway 99 |

Caltransb |

None specified |

1.0 |

|

Air quality |

ARBc |

None specified |

1.0 |

|

SLPd

grants |

CTC |

Annual report |

1.0 |

|

Transit security |

None specified |

None specified |

1.0 |

|

School bus retrofit |

None specified |

None specified |

0.2 |

|

Port security |

OESe |

Annual report |

0.1 |

|

Existing |

|

$5.5 |

|

STIPf |

CTC |

Annual report |

$2.0 |

|

Local roads |

Cities and counties |

Controller audits |

2.0 |

|

SHOPPg |

CTC |

Annual report |

0.8 |

|

Intercity rail |

Caltrans |

None specified |

0.4 |

|

Grade separations |

CTC/Caltrans |

Annual report/

None specified |

0.3 |

|

Local bridges |

Caltrans |

Annual report |

0.1 |

|

Total

Proposition 1B Bond Programs |

|

$19.9 |

|

|

|

a

California Transportation Commission. |

|

b

California Department of Transportation. |

|

c Air

Resources Board. |

|

d

State-Local Partnership. |

|

e

Office of Emergency Services. |

|

f

State Transportation Improvement Program. |

|

g

State Highway Operations and Protection Program. |

The monies for this myriad of programs, in turn, are to be administered by a variety of state and local entities, as highlighted in Figure 11. State entities include primarily the California Transportation Commission (CTC) and Caltrans. For funds provided directly to locals, recipients include cities and counties, as well as transit authorities, ports, harbors, and ferry terminal operators.

All Funds to Be Appropriated by Legislature. Proposition 1B specifies that all bond funds are subject to appropriation by the Legislature, either through the annual budget process or through other legislation before becoming available to a state or local entity for expenditure. Many Proposition 1B programs do not require oversight measures (such as reports or audits) to verify how bond funds are actually spent.

Some Programs Allow for Further Statutory Direction. With the exception of $1 billion in Air Quality funds, all monies provided in Proposition 1B could be appropriated and put to use without additional implementing statute. However, the bond act explicitly allows the Legislature to provide additional conditions and criteria through statute to five new programs created by the measure, involving $5.1 billion. These programs include Trade Corridors, Transit Security, Air Quality, State-Local Partnership (SLP) grants, and Port Security.

Governor’s Proposal

Proposed Expenditures and New Positions. The Governor’s budget proposes appropriating $7.7 billion in Proposition 1B money in 2007-08, with about $2.8 billion of this being expended in the budget year, as shown in Figure 12. This includes:

- About $1.5 billion to be expended by Caltrans or provided as grants for various highway, bridge, transit, and grade crossing projects.

- $600 million to be expended by transit operators on transit capital improvements.

- $600 million to be expended by local governments on street and road improvements.

- $97 million to be expended by the Air Resources Board on school bus retrofit and replacement.

|

Figure 12

Governor’s Proposed Expenditures |

|

(In Millions) |

|

Program |

2006-07 |

2007-08 |

|

Congestion Reduction, Highway, and Local Road

Improvements |

|

Corridor mobility |

$100 |

$317 |

|

State Transportation

Improvement Program |

262 |

340 |

|

Local roads |

— |

600 |

|

Highway 99 |

— |

28 |

|

State-Local Partnership grants |

— |

170 |

|

State Highway Operation and

Protection Program |

141 |

403 |

|

Transit |

|

|

|

Local transit |

— |

$600 |

|

Intercity rail |

— |

— |

|

Goods Movement and Air Quality |

|

|

|

Trade corridors |

$15 |

$170 |

|

Air quality |

— |

— |

|

School bus retrofit |

— |

97 |

|

Safety and Security |

|

|

|

Transit security |

— |

— |

|

Grade separation |

— |

$55 |

|

Local bridges |

$5 |

9 |

|

Port security |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

$523 |

$2,789 |

Despite proposing significant expenditures in the budget year, the Governor’s budget provides almost no staffing to support the project development activities funded with the bonds. Caltrans advises us that additional personnel resources will be requested in the May Revision.

In addition, the Governor’s budget proposes expenditures of $523 million by Caltrans in the current year on projects mainly in the State Transportation Improvement Program (STIP), State Highway Operation and Protection Program (SHOPP), and newly created Corridor Mobility program. Because all Proposition 1B funds are subject to legislative appropriation, these expenditures would require separate legislative action.

Proposed Policy Changes. In addition to appropriations, the administration is also proposing to expand the oversight role for CTC in the implementation of Proposition 1B. Specifically, the administration proposes that Local Transit funds be dispersed by formula to transit operators, as provided by Proposition 1B, but only after projects are approved by CTC. Moreover, the administration has adopted guidelines for the Highway 99 program, which channel funds through CTC rather than directly to Caltrans, as specified in the bond act.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

The infusion of bond funding is only a first step in improving California’s transportation landscape. In order to realize the full benefits of these funds, it is important that the projects funded are cost-effective in achieving desired results-including improved mobility, a more secure transportation system, and cleaner air. Moreover, these projects must be delivered in a timely manner. In this section, we highlight key challenges to achieving the goals of Proposition 1B and assess how well the Governor’s proposals address these challenges. Also, we recommend measures-statutory and administrative-to ensure that bond funds are used to deliver effective projects in a timely manner and that adequate oversight measures are in place. Our recommendations are summarized in Figure 13.

|

Figure 13

Recommendations to Improve

Proposition 1B Implementation |

|

|

|

ü

Determining Project Eligibility |

|

·

Limit all Proposition 1B funds to

projects with long-term benefits. |

|

·

Decide whether to limit transit

security funds to just security-oriented

investments. |

|

·

Structure state-local partnership

program to spur new local investment. |

|

ü

Adopting Additional Evaluation

Criteria for Project Selection |

|

·

Require measures of

cost-effectiveness. |

|

·

Require fund leveraging be considered. |

|

·

Require air quality impacts be

considered for new capacity projects. |

|

ü

Encouraging Timely Project Delivery |

|

·

Establish delivery deadlines to ensure

funds do not linger. |

|

·

Adopt provisions to remove funds from

lagging projects. |

|

ü

Ensuring Oversight Measures Are in

Place |

|

·

Require periodic reports to

Legislature. |

|

·

Hold joint legislative hearings. |

|

·

Enhance commission’s oversight

capacity. |

|

ü

Identifying Personnel Resources to

Deliver Projects |

|

·

Require annual update of multiyear

personnel resource plan. |

|

·

Authorize additional use of contracted

resources, as necessary to ensure timely delivery. |

|

ü

Streamlining Measures to Improve

Project Delivery |

|

·

Authorize design-build contracting on

pilot basis. |

|

·

Consider measures to streamline

environmental review. |

|

ü

Appropriating Bond Funds |

|

·

Appropriate all funds through budget

bill. |

Determining

Project Eligibility

The bond act varies in the level of detail it provides regarding project eligibility. For three programs totaling $3 billion-Air Quality, Transit Security, and SLP-the act provides little or no guidance as to the types of projects eligible for funding. While no expenditures from the Air Quality and Transit Security programs are proposed for 2007-08, the Governor’s budget shows $170 million in SLP grants to be awarded in the budget year. Before any bond funds are spent, the Legislature should provide eligibility guidelines statutorily to ensure that funds are used for projects that address state priorities. Below we present a general principle for determining project eligibility for all projects. We then discuss eligibility issues particular to two specific programs.

Limit Bond Funds to Projects With Long-Term Benefits. As a general principle, bond funds should be used only for capital improvements or activities that provide benefits over many years to taxpayers who finance the bonds. However, in the case of some Proposition 1B programs, the bond act does not prohibit funding activities that yield only short-term benefits. For example, $1 billion in Air Quality program monies are to be available for “strategies and public benefit projects” to reduce emissions related to goods movement. This language does not exclude short-term operational approaches to emissions reduction, even though the debt-service payments on the bond could outlast the activities they finance. To avoid this issue, we recommend the Legislature enact statute specifying that all Proposition 1B funds are available only for capital purchases or strategies that provide long-term benefits.

Decide Whether to Limit Transit Security Funds to Just Security-Oriented Investments. The bond act limits Transit Security dollars to capital projects, yet provides little additional guidance regarding project eligibility. Language directing the use of these funds is very open-ended-it allows these funds to be used either for transit projects that specifically address a security threat (for example, installing detection devices or security gates at train stations) or for projects that more generally increase a transit system’s capacity (such as adding vehicles to a transit fleet). Given this ambiguity, we recommend enacting statute that outlines more explicit eligibility requirements.

Structure SLP Grant Program to Spur New Local Investment. Proposition 1B provides $1 billion in SLP grants to match local funds for transportation projects over the next five years. The measure also allows the Legislature to add conditions and criteria to the program through statute. The CTC proposed guidelines that would provide funding to local jurisdictions that

have adopted local sales tax measures or developer fees for transportation. These guidelines, however, do not set aside any of these funds to create incentives for

new local revenues to be pursued in the future. In order to spur new local funding for transportation, we recommend that the Legislature adopt guidelines that would set aside a portion of SLP grants for cities and counties that establish new fees or tax measures for local transportation purposes.

Adopting Additional Evaluation Criteria For Project Selection

The bond act specifically authorizes the Legislature to adopt additional conditions and criteria for five new programs, involving $5.1 billion. These programs include Trade Corridors, Air Quality, Transit Security, SLP, and Port Security. Of these programs, the Governor’s budget proposes expenditures of $170 million in SLP grants and $185 million in Trade Corridors funds through 2007-08.

Of the five programs, the bond act provides evaluation criteria only for selecting Trade Corridors projects, but none for the other four programs. We recommend that the Legislature adopt project evaluation criteria for these new programs to ensure that bond funds are used efficiently and deliver effective projects. The following criteria could be applied across multiple Proposition 1B programs.

Require Measures of Cost-Effectiveness. This criterion focuses on the estimated benefit achieved per dollar spent on a project in order to ensure that bond funds consistently deliver the biggest bang for the buck. Depending on the program and its goals, the specific benefits to be measured will vary by program. For example, a measure to evaluate projects competing for Trade Corridors funds could include the volume of goods transported per dollar invested; whereas, the appropriate metric for Air Quality funds would be the level of emissions reduced for the amount spent on the project.

While cost-effectiveness is a useful criterion to evaluate projects competing for a number of Proposition 1B programs, it may not be the most appropriate to use in selecting projects for Transit Security and Port Security funds. This is because the particular benefits achieved by security-oriented projects (for example, lives saved from terrorist attacks) may be difficult to quantify.

Require Fund Leveraging Be Considered. Because the benefits of transportation investments are felt most at the local level, evaluating projects by their ability to tap into local, federal, and private dollars (so that state funds can be applied to more projects) makes sense. Currently, the bond measure requires fund leveraging in only some instances. These include Local Bridge funds that supplement available federal dollars, as well as SLP, Trade Corridors, and Grade Separation grants, which generally require a one-to-one match of nonstate funds. There are other programs, however, where leveraging should play a role in evaluating projects. In selecting Corridor Mobility projects, CTC indicates it will consider a project’s ability to leverage nonstate funds, particularly for large projects where matching funds are available.

In order to stretch bond funds as broadly as possible, we recommend the Legislature require projects be evaluated based on their ability to leverage nonstate funds. For example, statute should require consideration of applicants’ ability to leverage Transit Security and Port Security funds with federal grants or private dollars.

Admittedly, there may be cases where leveraging is less feasible. For example, projects located in rural areas may not be able to generate significant investment from local or private sources. To address such concerns, fund leveraging considerations should take into account a region’s ability to leverage funds.

Require Air Quality Impacts Be Considered for New Capacity Projects. Given that all of California’s major urban areas violate federal air emissions standards, project selection for Proposition 1B programs should consider a project’s impact on air quality. Proposition 1B addresses air quality in varying ways. Some programs, including Air Quality and School Bus Retrofit, are specifically targeted at reducing emissions. Language describing the Trade Corridors program lists emissions reduction as one consideration among many in evaluating projects for funding. The CTC’s proposed guidelines for the Corridor Mobility and SLP programs list air quality analysis as an optional element in project nominations.

So that entities, like CTC, that are charged with selecting projects can take emissions impacts into account, we recommend that the Legislature require analysis of air quality impacts to be included in all nominations where projects would add capacity to the highway and local road network. This would include projects funded by Trade Corridors and SLP grants.

Federal law requires many California regions to evaluate the emissions impact of transportation projects in their long-range plans. Thus, including air quality analysis as a part of the project nomination process should not impose significant additional analysis workload for these regions. For the few rural regions not subject to emissions reporting in their federal plans, these regions might be exempted from quantifying emissions impacts in project nominations.

Encouraging Timely Project Delivery

Projects must be completed and opened to users in a timely manner in order to offer any mobility, air quality, or safety benefits. Moreover, in an era of rising construction costs, delayed delivery often means increased construction costs, reducing the amount of improvements that can be achieved with available funding.

Establish Delivery Deadlines to Ensure Funds Do Not Linger. Generally, the bond act does not require that projects be constructed and opened to users by a specific date. The Corridor Mobility program is an exception-the bond act requires that these projects start construction by December 31, 2012. (If projects fall behind schedule, CTC is to remove funds.) The administration has adopted the same delivery timeline for Highway 99 funds. Setting timelines enables the Legislature to hold the administration and other fund recipients accountable for the delivery of projects. In other state transportation programs, notably the Traffic Congestion Relief Program, the absence of delivery deadlines has allowed funds to remain available indefinitely, even for stalled projects that show few signs of progress. To avoid repeating this situation with Proposition 1B funds, we recommend the enactment of legislation requiring the establishment of deadlines to begin project construction.

To ensure that adopted deadlines are reasonable on a program-by-program basis, the Legislature should direct CTC to specify project delivery deadlines for each program. For example, CTC could specify later deadlines for programs that fund large or complex projects requiring longer timeframes and shorter timeframes for programs where the delivery process is less involved.

Adopt Provisions to Remove Funds From Lagging Projects. In addition to setting delivery deadlines, the Legislature should enact statute that requires projects’ progress to be monitored and funds to be removed from those projects that are not advancing. The state already has a “use-it-or-lose-it” policy, established under Chapter 783, Statutes of 1999 (AB 1012, Torlakson), which allows CTC to redirect certain federal funds not expended by regions in a timely manner. Prior to the use-it-or-lose-it policy, regions had accumulated a $1.2 billion backlog of unused federal funds. This policy gives regions a strong incentive to expend federal funds in a reasonable timeframe and enables the state to make sure funds do not go unused.

Beyond regional agencies, Caltrans has a less than perfect record in delivering projects on time and on budget. Thus, we recommend the Legislature require an entity, like CTC, to regularly check fund recipients’ progress in meeting major project milestones, such as plan approval, completion of environmental review, right-of-way certification, and advertising a project for construction. Admittedly, this approach creates additional oversight workload. But, more importantly, it holds fund recipients accountable for delivering projects in a timely manner and provides the opportunity to identify delays and redirect funds, as necessary, to alternative projects that can meet delivery goals.

The Legislature has a few options in deciding how to redirect funds once removed from a stalled project. One approach would be to transfer funds to the highest performing project that did not previously receive funding. This option maximizes the benefit of bond funds on a statewide basis. Another option would be to redirect funds to other projects in the same geographic region, so that regions are held harmless. This option does not maximize the benefit of bond funds at a statewide level, but ensures that a region maintains its level of investment even when a local project loses funding. How the Legislature redirects funds from stalled projects depends on whether project performance or regional equity is the primary consideration.

To ensure that funds can be removed from lagging projects and redirected to other projects that address state priorities, we recommend the enactment of legislation that (1) directs CTC to monitor project milestones and identify delays, (2) authorizes CTC to redirect funds away from lagging projects, and (3) provides guidance on how these funds should be redirected.

Ensuring Oversight Measures

Are in Place

In many cases, the bond act does not call for specific program oversight through reports or audits, as shown in Figure 11. Given the large number of programs funded by Proposition 1B, the substantial amount of funding provided, as well as the number of entities charged to implement these programs, we recommend the Legislature adopt additional oversight measures to ensure that bond funds are used effectively.

Require Periodic Reports to Legislature. Current law requires CTC to report annually to the Legislature on funds it allocates to transportation programs and related policy issues. This report provides the Legislature with necessary information to monitor programs and take statutory action, as needed, to ensure funds are used appropriately. The CTC plans to include in future annual reports discussion of all Proposition 1B programs for which it will allocate funds. Under the bond act, this includes about one-half of the monies-Corridor Mobility, Trade Corridors, SLP grants, funds for STIP and SHOPP, as well as $100 million of the Grade Separation grants. If the Legislature concurs with the administration’s proposal that CTC allocate an additional $4.6 billion in bond monies, including funds for Highway 99 and Local Transit, these programs would also be included in CTC’s annual report.

However, even if the administration’s proposals are adopted, there would still be almost $5 billion in Proposition 1B funds that would not be included in CTC’s annual report because CTC does not allocate these funds. Though expenditures from some of these programs would be included in other miscellaneous reports, the information would be scattered, making it less conducive to oversight of the total bond program.

We think that having information on the status of all Proposition 1B programs in one place would facilitate legislative oversight. Accordingly, we recommend the enactment of legislation directing CTC to include discussion of all bond-funded programs in its annual report. Additionally, the Legislature should require fund recipients to provide CTC with information on all projects funded by Proposition 1B monies. This information should include each project’s annual expenditures and progress in meeting major milestones (including plan approval, completion of environmental review, right-of-way certification, and listing for construction), as well as explanation of any delays in the delivery process.

Hold Joint Legislative Hearings. Beyond requiring project specific information through annual reporting, we further recommend that the policy committees and budget subcommittees of the Legislature hold periodic joint hearings in which CTC, Caltrans, and other key implementing entities report on the use of bond funds and the timeliness of project delivery. This would provide the Legislature an opportunity to monitor the progress of the bond program in the aggregate, and assess whether the programs are being carried out effectively to meet the measure’s objectives.

Enhance CTC’s Oversight Capabilities. Given the size of the bond program and number of fund recipients, one central entity should provide ongoing oversight of all bond-funded activities. With its experience in overseeing transit and highway programs statewide, CTC is a logical choice to perform that oversight function. The Governor’s budget provides two positions to supplement CTC’s current staff of 16 personnel-years (PYs). However, depending on the role the Legislature decides CTC is to play, significant workload could be involved. We recommend that the Legislature take action to enhance the commission’s oversight capacity.

The Legislature has a few options in doing so. One option is to provide additional staff to CTC, beyond what is proposed in the Governor’s budget. An alternative is to provide CTC with the authority and flexibility to use consultant services to perform selected project evaluation and oversight functions, on an as-needed basis to supplement commission staff.

Identifying Personnel Resources to

Deliver Projects

Caltrans will play a crucial role in delivering $12 billion in highway, bridge, and transit projects through several Proposition 1B programs. This represents a 33 percent increase in the value of total projects that Caltrans is currently working on. To deliver these projects in a timely manner, Caltrans will need additional personnel resources to plan and construct projects in 2007-08 and beyond. Ensuring that Caltrans has adequate capital outlay support (COS) resources-including both state staff and contracted services-will be essential to the timely delivery of many Proposition 1B projects.

Require Annual Update of Multiyear Personnel Resource Plan. Given the upsurge in workload, it is important that Caltrans inform the Legislature about its estimates of the future-year COS funding needs, as well as what portion of the delivery workload it will have to contract out given constraints in hiring state staff.

Supplemental report language accompanying the 2006-07 Budget Act requires Caltrans to develop, by May 1, 2007, a multiyear staffing plan that estimates the level of personnel resources Caltrans will need each year through 2010-11 for project development workload related to Proposition 1B. The report is also required to provide (1) the anticipated composition of these resources, in terms of the breakdown between state staff, cash overtime, and contracting out; (2) data on Caltrans’ recent experience in recruiting and retaining project delivery employees; and (3) actions the department will take to attract employees, cost-effectively train its new workforce, and minimize attrition rates.