(Elizabeth Hill's Webcast Describing the Fiscal Outlook)

November 14, 2007

California's Fiscal Outlook:

LAO Projections 2007-08 Through 2012-13

Summary

Deterioration of the 2007–08 Budget

At the time the 2007–08 Budget Act was enacted in August 2007, the budget plan focused on closing the gap between General Fund revenues and expenditures for the fiscal year and maintaining a $4.1 billion reserve. Since that time, the 2007–08 budget situation has deteriorated by almost $6 billion. Under our forecast, absent corrective action, the state would end the current fiscal year with a $1.9 billion deficit. The state’s dimming fiscal outlook is due to:

- Continued softness in the state’s economy lowering the forecast of revenues.

- Lower property taxes, driving state General Fund spending on K–14 education upwards.

- A likely delay in the sale of EdFund and a reduction in anticipated revenues.

- Delayed implementation of new tribal gambling compacts.

- A court–ordered payment to the state’s teacher retirement system.

State Also Faces $8 Billion Shortfall in 2008–09

In addition to a negative carry–in balance from 2007–08, we project the state will face an $8 billion operating shortfall in 2008–09. Revenues are projected to grow by 4.6 percent, hampered by the ongoing effects of the weakened economy. On the expenditure side, spending is projected to grow by 7 percent—reflecting both cost increases in most state programs and the end of many 2007–08 one–time budget solutions.

Multibillion Dollar Shortfalls Through 2012–13

Like in 2008–09, we project state costs will exceed revenues by $8 billion in 2009–10. After that, the shortfall will drop to the range of $3 billion each year. The primary factor responsible for this drop between 2009–10 and 2010–11 is that $11.3 billion in previously issued deficit–financing borrowing would be fully paid off in the spring of 2010. This will free up over $3 billion in annual debt service payments beginning in 2010–11.

LAO Bottom Line

In order to balance the 2008–09 budget, the state will have to adopt nearly $10 billion in solutions. Addressing the state’s current budget problem is even more urgent because we forecast a continuing gap between revenues and expenditures. A plan to permanently address the state’s fiscal troubles must involve a substantial portion of ongoing solutions. This is not only because of the persistent operating deficits projected throughout the forecast, but also because of the downside risks inherent with the economy, General Fund revenue volatility, and a wide range of budgetary uncertainties. Making tough choices now will allow the state to move closer to putting its fiscal woes in the past.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

The Budget Outlook

This report provides our projections of the state’s General Fund revenues and expenditures for 2007–08 through 2012–13. Our fiscal projections primarily reflect current–law spending requirements and tax provisions, while relying on our independent assessment of the outlook for California’s economy, demographics, revenues, and expenditures. The report aims to assist the Legislature with its fiscal planning as it begins to consider the 2008–09 budget. The basis of our assumptions is described in the box below.

Basis for Our Estimates

Our revenue and expenditure forecasts are based primarily on the requirements of current law, including constitutional requirements (such as Proposition 98) and statutory requirements (such as cost–of–living adjustments [COLAs]). In other cases, the estimates incorporate effects of projected changes in caseloads, prices, federal requirements, court orders, and other factors affecting program costs.

What Is Not Included? We have not included funding to cover the Governor’s “compact” with higher education, as the Legislature has taken no statutory action to implement such an agreement during this multiyear period. Rather, our estimates for higher education are based on projected enrollment and inflation–related increases. For instance, in 2008–09, fully funding the compact would require added expenditures of nearly $200 million beyond those we are projecting. Similarly, our projections do not account for any fiscal effects from proposed health care reforms. In the social services area, our projections do not include the costs of providing COLAs for the foster care program or county welfare administration costs. Based on recent experience, the Legislature has considered these latter costs on an annual basis.

Projections, Not Predictions. Our estimates are not predictions of what the Legislature and Governor will adopt as policies and funding levels in future budgets. Rather, our estimates are intended to be a reasonable baseline projection of what would happen if current–law policies were allowed to operate in the future. In this regard, we believe that our forecast provides a meaningful starting point for legislative deliberations involving the state’s budget so that corrective actions can be taken to ensure that the state’s fiscal house is in order. |

Update on the 2007–08 Budget

The Budget as Adopted Had $4 Billion Reserve

At the time the 2007–08 Budget Act was enacted in August 2007, the budget plan focused on closing the gap between General Fund revenues and expenditures for the fiscal year. State revenues and expenditures were both projected to be $102.3 billion. The plan also had a $4.1 billion reserve. The budget closed the state’s ongoing gap between revenues and expenditures using largely one–time solutions. Consequently, the state was expected to once again face multibillion budget shortfalls beginning in 2008–09.

Negative Factors Will Deplete the Reserve and Leave a Year–End Deficit

We have updated our forecast of the 2007–08 General Fund condition to reflect (1) key changes that have occurred since August and (2) updated revenue and expenditure forecasts. Almost all of these factors have been negative. As described in more detail below, the deterioration of the state’s budget outlook is due to a combination of a worsening economic and revenue picture, delayed benefits from budget solutions, and higher costs. We project that the state’s 2007–08 budget has deteriorated by a total of almost $6 billion. Consequently, rather than having a $4.1 billion reserve, the state faces a 2007–08 year–end deficit of $1.9 billion. Figure 1 summarizes the decline in the state’s budget outlook.

Figure 1

What Happened to the $4 Billion Reserve? |

(In Millions) |

|

Reserve as of June 30, 2008 |

2007-08 Budget Act (August 2007) |

$4,070 |

Revenues on the Decline |

|

Lower 2006‑07 major tax revenues |

-$604 |

Receipt of 2006‑07 Medi-Cal quality assurance fee revenues |

180 |

Lower 2007‑08 tax forecast |

-2,082 |

Lower property taxes (Proposition 98) |

|

2006‑07 |

-356 |

2007‑08 |

-686 |

EdFund sale not achievable in 2007‑08 |

-1,000 |

Delayed implementation of tribal compacts |

-210 |

Delayed child support penalty rebate |

-198 |

Expenditures on the Rise |

|

CalSTRS payment |

-$500 |

Correctional officer pay increase |

-258 |

Unallocated reductions not achievable |

-240 |

Higher firefighting costs |

-174 |

Other (net savings) |

184 |

LAO Revised Reserve (November 2007) |

-$1,874 |

Revenues on the Way Down…

2006–07 Revenues Adjusted Down. Based on the 2007 May Revision revenue estimates, the budget assumed that the state received $96 billion in 2006–07. However, revenues collected for the months of May and June were significantly below projections. Due to some uncertainty regarding the final 2006–07 amounts at the time of the budget’s enactment, the 2006–07 revenue total was not adjusted in the budget plan. Tax revenues for 2006–07 have now been revised and were about $600 million below the budget’s forecast. Somewhat offsetting this decline was the receipt of $180 million in Medi–Cal quality assurance fee revenues.

Slower Growth in Revenues. Since the enactment of the budget, the state’s economy has shown continuing signs of weakness—particularly with the depressed real estate market and high energy and gasoline prices. In addition, year–to–date cash receipts for tax revenues have been falling considerably short of budget estimates. As described in depth in Chapters 2 and 3, these factors have resulted in our forecast reducing expected 2007–08 tax revenues by more than $2 billion.

Property Taxes Declining. Combined over 2006–07 and 2007–08, our forecast of property tax revenues for school districts is lower than the enacted budget assumptions by more than $1 billion. Because the property tax revenues received by school districts generally offset the state’s General Fund Proposition 98 expenditures on a dollar–for–dollar basis, this means that state General Fund costs are now projected to be $1 billion higher. This decline is due to two issues:

- Lower Base From 2005–06. The 2007 May Revision recognized a roughly $300 million reduction in actual 2005–06 property tax receipts compared to earlier projections. The enacted budget assumed that this was a one–time decline and that 2006–07 revenues would rebound to a higher level. The budget authorized the State Controller’s Office (SCO) to conduct an audit of receipts to determine the reason for the drop in revenues. Earlier this month, SCO released its audit which found no reason to expect 2006–07 revenues to significantly rebound. Consequently, our property tax forecast assumes the lower 2005–06 base—raising General Fund Proposition 98 expenditures by more than $350 million for 2006–07 and 2007–08.

- Lower Growth in Revenues. The enacted 2007–08 budget assumed that property taxes generally would grow at a rate of 10 percent. Due to the slumping real estate market, our forecast of property tax revenues is somewhat lower—at 8.7 percent. This raises General Fund Proposition 98 expenditures by roughly an additional $300 million in 2007–08.

EdFund Sale Likely Delayed and Downsized. One of the budget plan’s major solutions was authorizing the Director of the Department of Finance (DOF) to sell EdFund, the state’s nonprofit agency that administers federal student loan guarantee programs. The budget assumed $1 billion in one–time 2007–08 revenues from the sale. Since the budget’s enactment, federal changes to the loan guarantee programs reduced the financial attractiveness of such businesses. In addition, it is less likely that the complicated sale could be finalized by the end of the current fiscal year. Consequently, our projections now assume that the state will receive $500 million from EdFund’s sale—but not until 2008–09.

Child Support Automation Rebate Delayed. In recent years, the state has paid hundreds of millions of dollars in federal penalties due to delays in implementing a child support automation system. Due to expected federal certification of the state’s new system, the enacted budget assumed the receipt in 2007–08 of $198 million in rebated penalties. We now expect that certification to be delayed and the receipt of the funds in 2008–09.

Lower Indian Gambling Revenues. Measures passed by the Legislature in 2007 ratify amended compacts between the state and five Southern California Indian tribes and authorize those tribes to expand their casino operations with up to 22,500 new slot machines on a combined basis. Based primarily on a DOF analysis submitted to the Legislature with the May Revision, the budget package assumed that the state would receive $293 million in new General Fund revenues in 2007–08 as a result of the five new compacts. While the measures were passed on a majority–vote basis (meaning that they would take effect on January 1, 2008), the DOF analysis assumed that the compacts would be ratified on an urgency basis (to take effect on or about July 1, 2007). Subsequent to the Legislature’s actions on the compacts in June, referenda petitioners submitted signatures of registered voters to place the legislative measures ratifying four of the compacts on the February 2008 statewide ballot. (Final federal approval of the compacts also would be required.) As a result of these delays, we project that 2007–08 General Fund revenues from tribal compacts will be more than $200 million lower than the budget assumed.

…While Expenditures Are on the Way Up

State Lost Teachers’ Retirement Lawsuit. In 2003–04, as a budget balancing solution, the state reduced by $500 million, on a one–time basis, an annual appropriation to the purchasing power protection program of the California State Teachers’ Retirement System. In September 2007, the Third District Court of Appeal ruled that the reduction unconstitutionally violated the contractual rights of system members. Consequently, the administration repaid the $500 million. The amount of interest owed on the payment is being appealed by the administration and will require a future appropriation to be paid. The interest owed could total in the range of $200 million. (Our estimates assume that the interest payment occurs in 2008–09.)

Correctional Officer Pay. Following an impasse in negotiations with the union representing state correctional officers, the administration began implementation in September 2007 of its final offer to the union. That offer included a current–year salary increase of 5 percent at a General Fund cost of $258 million. Although the Legislature has not yet acted on this proposal, we have included the costs in our forecast. These costs could be lower or higher depending on legislative action.

Unallocated Reductions Unlikely to Meet Targets. The enacted budget assumed that the administration would reduce expenditures by $258 million during the fiscal year through unallocated reductions. The budget provision intended to achieve $100 million of this amount has traditionally failed to generate new savings and instead counts savings elsewhere in the budget which occur on the natural from, for example, reduced caseload. Of the remaining amount, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation was expected to cover $106 million in reductions—despite the department’s history of budget shortfalls. As a result, our forecast assumes that only a minimal amount of the assumed savings will be achieved.

Southern California Wildfires. The 2007–08 budget includes $82 million for statewide emergency firefighting costs. Our forecast assumes the state will spend $174 million more in firefighting costs than the budgeted amount over the course of the year. Most of this increase—$140 million—results from the recent Southern California wildfires. (However, it is likely that the federal government will reimburse the state for a substantial portion of this cost in future years.)

Bigger Problems in 2008–09 As Well

Figure 2 shows our updated projection of the General Fund condition through 2008–09. As a result of the factors described above, we project that 2008–09 will begin the year with a negative reserve of $1.9 billion. In 2008–09, we project revenues will climb to $103.5 billion, an increase of 4.6 percent from the current year. We project expenditures will total $111.4 billion, an increase of 7 percent. Consequently, under our current–law projections, the General Fund would be left with a 2008–09 year–end deficit of $9.8 billion absent corrective actions. The box below helps explain our use of “year–end deficit” and other terms associated with the state’s budget problems.

Our forecast of an $8 billion gap between 2008–09 revenues and expenditures is worse than our earlier projections. This is largely the result of the ongoing impact of our reduced revenue forecast. Partially offsetting this decline in revenues is the shift in our forecast of revenues from 2007–08 to 2008–09 for the sale of EdFund and the receipt of the federal child support automation rebate.

Figure 2

LAO Projections of General Fund Condition |

2006-07 Through 2008-09

(In Millions) |

|

2006-07 |

2007-08 |

2008-09 |

Prior-year fund balance |

$10,435 |

$4,114 |

-$1,129 |

Revenues and transfers |

95,578 |

98,916 |

103,512 |

Total resources available |

$106,013 |

$103,030 |

$102,383 |

Expenditures |

$101,899 |

$104,159 |

$111,428 |

Ending fund balance |

$4,114 |

-$1,129 |

-$9,045 |

Encumbrances |

$745 |

$745 |

$745 |

Reserve |

$3,369 |

-$1,874 |

-$9,790 |

Budget Stabilization Account |

$472 |

—a |

—a |

Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties |

$2,897 |

—a |

—a |

|

a Under current law, the General Fund will deposit $1 billion in 2007-08 and $1.6 billion in 2008-09

into the Budget Stabilization Account for use as a budgetary reserve. Due to the projected budget shortfalls, however, these funds and any funds in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties are

assumed to be used to partially address the shortfalls. |

Definitions of a Budget Problem

In recent years, a number of different terms have been used to describe the state’s fiscal woes. At times, these terms have been used interchangeably—even though they often have significantly different meanings. In other words, the magnitude or meaning of the state’s “budget problem” may be very different depending on which term is being used.

Operating Shortfall/Operating Deficit. These terms focus on the difference between revenues and expenditures in a single budget year. For instance, under our forecast, the operating shortfall for 2008–09 is $7.9 billion ($111.4 billion in expenditures less $103.5 billion in revenues). In better financial times, an operating surplus is the opposite—when the state receives more money than it spends in a single budget year.

Strictly looking at an operating shortfall makes sense when evaluating the future. If expenditures are expected to exceed revenues for the foreseeable future, then the state should take actions to bring these two trend lines into balance. The term “structural budget deficit” may be used to describe this type of chronic operating shortfall.

Budget Deficit/Year–End Deficit. These terms are similar to operating shortfall but make the key addition of considering the state’s carry–in reserve from the end of the prior fiscal year. Budget deficit and year–end deficit have more relevance in the short term when considering an upcoming budget. That is because the most immediate task for the Legislature is passing a “balanced budget”—by eliminating any year–end deficit and ensuring a reserve at the end of the year. Thus, the state could adopt a balanced budget even when it has an operating deficit because of a positive carry–in reserve. If a carry–in reserve is negative, however, the upcoming budget must have more revenues than expenditures to avoid a year–end deficit. The Legislature faces this situation with the 2008–09 budget. Revenues in 2008–09 must exceed expenditures by $1.9 billion to make up for the projected negative carry–in reserve.

Net Operating Deficit. This is a term developed by the administration in presenting its budget in January 2007. It attempts to account for any one–time revenues and/or expenditures within an operating shortfall. By stripping out these one–time factors, net operating deficit can help identify the state’s underlying budget problem. In addressing an immediate budget problem, however, the concept is less helpful. That is because, regardless of how they are characterized, one–time costs remain obligations of the state that must be paid. |

Longer–Term Forecast

Our longer–term revenue and expenditure forecasts are detailed in Chapter 3 and Chapter 4, respectively. Based on these forecasts, Figure 3 shows that the state’s budget woes are projected to continue through 2012–13. In 2009–10, the state would once again face an operating shortfall of $8 billion. After that, the annual operating shortfall would drop to the range of $3 billion each year. The primary factor responsible for this decline in the shortfall after 2009–10 is that the $11.3 billion in previously issued deficit–financing bonds would be fully paid off in the spring of 2010. This will free up over $3 billion in annual debt service payments beginning in 2010–11. Another key factor in 2010–11 is improved revenue growth, in part due to the renewed effect of the estate tax.

The Impact of Prior Borrowing and Debt. Figure 3 breaks the state’s projected operating shortfalls into two components:

- Basic. The portion due to each year’s difference between current–law spending and revenues.

- Budgetary Borrowing. The portion due to the state’s obligations from past borrowing to address budget problems.

At the start of 2008–09, we project the state will have about a $20 billion balance on its budgetary borrowing. The state is scheduled to make $4 billion payments towards this amount in both 2008–09 and 2009–10. In these years, the portion of the shortfall due to past borrowing is about one–half of the state’s problem. Once the deficit–financing bonds are paid off, the share due to borrowing falls somewhat—to about one–third of the annual problem for the following two years. While the past borrowing helped the state get from one fiscal year to the next, it has created additional spending pressures each year to pay for past rather than current services.

Additional Risks, Uncertainties, and Cost Pressures

Our forecast captures our best estimates at this time regarding the state’s fiscal condition. Yet, the state faces a number of other risks, uncertainties, and cost pressures not accounted for in our forecast as discussed below.

Legal Issues. The state faces a number of court cases with sizable fiscal liabilities.

- Use of Transportation Funds. The largest such lawsuit challenges the 2007–08 budget’s use of transportation funds for the General Fund’s benefit. On September 6, 2007, the state was sued by public transit advocates arguing that the budget’s redirection of $1.3 billion in transportation funds for various purposes benefiting the General Fund is illegal. The case is expected to be heard at the end of November. If the state is unable to defend its various actions, the 2007–08 budget would be up to $1.3 billion in further deficit. In addition, a portion of the redirection is intended to be ongoing. Our estimates assume more than $400 million in General Fund savings each year throughout the forecast period. Those savings are at risk as well.

- Correctional Issues. The state continues to deal with a variety of federal lawsuits related to the correctional health care system. While our forecast includes many costs associated with these lawsuits, the potential for additional costs remains. On the other hand, if the federal courts imposed a correctional population cap (currently under review), state prison costs would be hundreds of millions of dollars lower each year due to fewer inmates being in the state’s system.

- Other Legal Issues. During its 2007 session, the Legislature enacted measures to reduce the financial risk in cases involving limited liability companies’ tax obligations and the state’s unclaimed property program. However, some potential liabilities remain in these areas until the pending cases are ultimately resolved.

Estate Tax. California’s estate tax—which is tied to the federal estate tax—is not presently in effect. Under current federal law, California’s estate tax would once again collect revenues beginning in 2011. If this were to occur, California’s tax would raise roughly $900 million in 2010–11 (a half–year effect) and $1.9 billion in 2011–12 and thereafter. These revenues are included in our forecast. Should the scheduled changes in the tax at the federal level be modified, these revenues would need to be adjusted downward.

Taking Steps to Balance the Budget

In each year since 2001–02, the state has faced budget problems of varying magnitudes. Once again, the Legislature will face a major challenge in bringing the 2008–09 budget into balance. It will need to develop a budget plan that provides almost $10 billion in solutions. Addressing the state’s current budget problem is even more urgent because we forecast a continuing gap between revenues and expenditures. Without permanent budget solutions, the state will continue to face annual budget problems. A plan to permanently address the state’s fiscal troubles must involve ongoing solutions.

In past years, the Legislature has been concerned that in addressing a current budget problem, it not “overcorrect” by adopting permanent solutions—such as deep cuts in programs—that would not be necessary in the out–years. For instance, permanent spending reductions of $10 billion to address the 2008–09 budget problem would be more than needed by 2010–11 (see Figure 3). While this is a valid concern, we believe a substantial portion of the current budget problem needs to be addressed through ongoing solutions. This is not only because of the persistent operating deficits over the life of the forecast, but also because of the downside risks inherent with the economy, General Fund revenue volatility, and the various budgetary uncertainties described in the previous section. Even with such an approach, the state would still need to come up with billions of dollars in additional solutions of a more limited duration to get through the worst of the upcoming budget years—2008–09 and 2009–10.

Budget Savings and Revenue Increases. In order to achieve ongoing budget solutions, there are numerous options available, though almost all of them involve making tough policy choices.

- Slowing program growth by reducing or eliminating cost–of–living adjustments (COLAs).

- Rolling back recent program expansions or reducing the level of program benefits.

- Eliminating duplicative or ineffective programs and restructuring program delivery methods.

- Shifting costs to special funds or to user fees.

- Eliminating tax credits and tax expenditure programs.

- Increasing efforts to enforce existing tax laws and ensure compliance.

- Raising tax rates.

Current–Year Solutions? Under our forecast, the state will end the current fiscal year with a deficit of $1.9 billion. While the state is not required by law to take action to bring the 2007–08 budget into balance, the Legislature should strongly consider doing so. By taking action now, the Legislature in some cases can “double up” its savings from any enacted solutions. That is, by acting this year, a program reduction can generate savings in 2007–08 which will then carryover into 2008–09. For instance, as we discuss in Chapter 4, reducing Proposition 98 spending to the minimum guarantee in 2007–08 would result in about $400 million in savings that year and allow roughly the same amount of savings to be achieved in 2008–09. In other cases, solutions may need early action in order to get a full year’s worth of savings in 2008–09. This would often be the case in program reforms or restructurings. Similarly, if the Legislature wished to delay or suspend COLAs, it may require action prior to July 1, 2008. For example, the 2007–08 Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Program COLA is due to go into effect on June 1, 2008, and the Legislature would need to act this spring if it wished to suspend it and generate $250 million in ongoing savings beginning in 2008–09. In the end, any improvement that the state can make in its 2007–08 year–end balance will make it that much easier to balance the 2008–09 budget.

Suspend the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) Transfer? As we discuss in the box below, under current law, the General Fund would transfer $3.1 billion to the BSA in 2008–09. One–half of this amount would go towards supplementing the “triple flip’s” pay off of the state’s deficit–financing bonds, and the other one–half would be held as a reserve. The Governor has the authority to suspend this transfer through an executive order by June 1, 2008. If he did so, this would reduce 2008–09 expenditures by $1.6 billion (by not making the supplemental deficit–financing bonds payment). The triple flip would continue to make its $1.5 billion in 2008–09 bond payments. While paying off budgetary borrowing improves the state’s long–term fiscal outlook, the state’s current repayment schedule is particularly heavy in 2008–09 and 2009–10. If the Governor were to suspend the transfer, the costs of repaying past budgetary borrowing would be extended.

Budget Stabilization Account, Deficit–Financing Bonds, And the Budget Outlook

At the March 2004 election, the state’s voters approved Propositions 57 and 58. The propositions, which amended the State Constitution, implemented a number of key changes that will factor into the development of the 2008–09 budget.

Balanced Budget Requirement. While previously the Governor was required to propose a balanced budget, Proposition 58 requires the Legislature to enact a balanced budget. At the same time, nothing in the measures prohibit the state from ending a fiscal year with a deficit (as would occur under our forecast for 2007–08). Yet, the next year’s enacted budget would have to make up this carry–in deficit to meet the balanced budget requirement. The Governor is also authorized to declare a fiscal emergency and call a special session of the Legislature to address it.

$15 Billion in Deficit–Financing Bonds. The voters authorized the issuance of up to $15 billion in deficit–financing bonds. In essence, the voters allowed the state to borrow money to pay off a portion of the state’s budget debts (as of the end of 2003–04). After the passage of the measures, the state raised $11.3 billion from these bonds—leaving up to $3.7 billion in additional funds that could be raised.

The “Triple Flip.” In a complex financing mechanism that is known as the triple flip, the voters established a mechanism to pay off the debt from the deficit–financing bonds. One quarter of a cent of the local sales tax is diverted to pay off the bonds. While there is outstanding debt, local government sales tax revenues are replaced on a dollar–for–dollar basis with property taxes shifted from K–14 school districts. In turn, K–14 school losses are offset by increased state General Fund spending through Proposition 98. The triple flip is expected to pay $1.5 billion towards bond debt in 2007–08 and another $1.5 billion in 2008–09.

The Budget Stabilization Account (BSA). Proposition 58 established a new General Fund budget reserve, called the BSA. The measure requires that annual transfers be made to this account totaling 1 percent of revenues in 2006–07 (equivalent to $944 million), 2 percent in 2007–08 (equivalent to $2 billion), and 3 percent thereafter ($3.1 billion in 2008–09) until the balance of the account reaches either $8 billion or 5 percent of General Fund revenues, whichever is greater.

- Bond Payoff. One–half of the annual transfers is allocated to a subaccount to make supplemental payments on the outstanding deficit–financing bonds until they are paid off. This amount was $1 billion in 2007–08 and will be $1.6 billion in 2008–09.

- Budget Reserve. The other one–half is held in reserve and available to support General Fund expenditures (as is the case for the state’s other reserve, called the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties). Due to the budget shortfall under our forecast, we expect the entire reserve balance of the BSA to be transferred back to the General Fund in 2007–08 (the $1 billion transferred in 2007–08, plus the $472 million carried over from 2006–07), as allowed under the 2007–08 Budget Act. Similarly, $1.6 billion of the reserve would be immediately used in 2008–09 for budget balancing—leaving a zero balance in the BSA.

The Governor has the authority to suspend the annual transfer through an executive order issued by June 1 of the preceding fiscal year. (Our forecast assumes that the transfers are not suspended.)

Outstanding Balance of Deficit–Financing Bonds. By the start of the 2008–09 fiscal year, we expect roughly one–half of the $11.3 billion in deficit–financing borrowing to be paid off. If the Governor does not suspend the BSA transfers in 2008–09 and 2009–10, the remaining $6 billion in outstanding bonds would be paid off by the spring of 2010.

Difference From Department of Finance (DOF). Our display of the BSA in our General Fund condition statement (Figure 2) differs somewhat from DOF. On the revenue side, we include all funds that will be transferred to the BSA (3 percent of revenues in 2008–09). In contrast, DOF only shows one–half of this amount (1.5 percent in 2008–09) as revenues. The DOF excludes the amount of revenues dedicated to the BSA reserve. We believe our display better captures the total level of resources available for General Fund obligations. On the expenditure side, there is no difference. We and DOF both show the portion of the BSA being used to pay off the deficit–financing bonds as a General Fund expenditure. The remaining one–half of the BSA is not shown as an expenditure since the funds are being held in reserve and are not being spent for a specific purpose. Our different treatments of revenues, however, does not affect the bottom–line reserve. In other words, for a particular level of General Fund revenues and expenditures, we and DOF would show the same number in the reserve line of a General Fund condition statement. Yet, DOF’s reporting of an operating shortfall would tend to be higher since its revenue total is lower. |

More Borrowing? Since its budget problems began at the start of the decade, the state has relied on numerous forms of borrowing and deferrals to help balance its books. This has included raising $11.3 billion from deficit–financing bonds, accelerating the receipt of two decades’ worth of tobacco settlement payments through securitization, borrowing funds from state special funds (particularly transportation), and shifting costs into the future. With the Governor and the Legislature unable to agree on major program reductions and/or a broad–based tax increase, these techniques have tended to be the “path of least resistance.” At this point, the state has $20 billion in outstanding borrowing from its previous budget problems. We therefore believe that additional borrowing or deferring more costs into the future should be considered only as a last resort.

Issue the Remaining Deficit–Financing Bonds? Given the magnitude of the state’s 2008–09 budget problem, however, we recognize that additional borrowing may be explored. One option in this regard would be to raise the remaining $3.7 billion from deficit–financing bonds as authorized by voters in 2004. If the Legislature wanted to pursue this option, there would be some legal and technical issues to explore to ensure the issuance meets constitutional restrictions and could provide immediate budgetary benefit to the General Fund. Such an approach would not be without its costs. The state’s debt payments through the triple flip and BSA would be extended into the future—making it harder to balance future budgets and incurring additional interest costs.

Leasing the Lottery? In May, the administration first suggested the notion of leasing the state Lottery to a private vendor on a long–term basis—in exchange for payments to the state. The underlying basis for the proposal is that a private vendor could enhance the performance of the Lottery. Although the administration has since suggested using a lease to help finance its health care proposal, it would be possible to reorient the concept back towards benefiting the General Fund. While changes to the Lottery are worth considering, the Legislature should approach using the Lottery as a budget solution with caution.

- Unknown Value. The administration has received estimates that the lease of a Lottery could yield between $14 billion and $37 billion in a one–time payment to the state. The amount the private sector would pay is not known and would depend largely on the “strings attached” to the deal by the Legislature and the state’s voters. If the proceeds were first used to hold education entities “harmless” (currently about $1 billion annually), then any net revenues available to the General Fund would be greatly reduced from the above estimates.

- Use of a One–Time Payment. Taking a one–time payment could offer a large influx of revenues that could be used to address the state’s near–term budget problem. The downside is that the availability of a lump sum could result in the state not taking the steps needed now to solve its longer–term budget problem.

- Difficult to Rely on in a 2008–09 Budget Plan. If the Legislature decided it wanted to pursue a Lottery lease as a budget solution, it would be difficult to build any benefit into the 2008–09 budget plan. This is because of its unknown value, as well as the time it would take to go to the state’s voters for authorization and process a lease agreement. Due to the uncertainty, we think the Legislature should recognize a realistic implementation time line and be wary of adopting an overly optimistic fiscal estimate of a Lottery lease.

Long–Term Perspective Needed. The magnitude of the 2008–09 budget problem makes it difficult to focus on the fiscal problems that loom in 2009–10 and beyond. Yet, the state’s structural budget problem will only be fully addressed once ongoing revenues and expenditures are brought into line and budgetary borrowing is repaid. In crafting its 2008–09 budget, therefore, the Legislature should keep an eye on improving the state’s long–term fiscal health through the adoption of as many ongoing solutions as possible. Making tough choices now will allow the state to move closer to putting its fiscal woes in the past.

Chapter 2

Economic and Demographic Projections

Economic and demographic developments are important determinants of California’s fiscal condition, primarily through their impacts on state revenues and expenditures in such areas as education, health, social services, corrections, and transportation. This chapter presents our economic and demographic projections for calendar years 2007 through 2013, which will affect California’s budgetary condition during the period 2007–08 through 2012–13.

The Economic Outlook

We expect both the national and state economic expansions to continue during the forecast period, although growth will likely remain subdued through 2008.

Figure 1 summarizes our forecasts for key economic variables for both the nation and California. In the subsequent sections, we discuss our forecasts in more detail and the major factors underlying our outlook.

Figure 1

The LAO’s Economic Forecast |

Percentage Change (Unless Otherwise Indicated) |

|

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

United States |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Real gross domestic product |

2.1 |

1.9 |

2.9 |

2.9 |

2.8 |

2.7 |

2.4 |

Personal income |

6.5 |

4.7 |

5.1 |

5.4 |

5.2 |

5.2 |

4.9 |

Wage and salary jobs |

1.3 |

0.7 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

0.8 |

Consumer Price Index |

2.7 |

2.2 |

1.9 |

2.0 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

Unemployment rate (%) |

4.6 |

5.0 |

4.9 |

4.8 |

4.6 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

Housing starts (000) |

1,344 |

1,102 |

1,389 |

1,577 |

1,705 |

1,711 |

1,699 |

California |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Personal income |

5.3 |

4.9 |

5.3 |

5.6 |

5.6 |

5.7 |

5.6 |

Wage and salary jobs |

1.1 |

1.0 |

1.3 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

Taxable sales |

3.2 |

3.8 |

4.7 |

6.0 |

5.9 |

5.8 |

5.7 |

Consumer Price Index |

3.3 |

2.7 |

2.2 |

2.2 |

2.0 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

Unemployment rate (%) |

5.3 |

5.7 |

5.6 |

5.4 |

5.3 |

5.2 |

5.1 |

Housing permits (000) |

121 |

125 |

149 |

159 |

167 |

172 |

175 |

The U.S. Economy

Recent Developments

Economy Has Generally Been Slowing. Figure 2 shows that after expanding by 3.6 percent in 2004, U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) growth slowed to 3.1 percent in 2005 and a bit more to 2.9 percent in 2006. For 2007, based on performance thus far, it is expected to slow further in the fourth quarter and show a sharp decline to 2.1 percent for the year as a whole.

Within the context of this pattern of overall economic slowing since 2004, however, the quarter–to–quarter growth pattern has been quite choppy, which has given mixed signals and made it difficult at times to clearly discern exactly what the underlying trends in the economy are and where it is heading.

But Haven’t Recent Developments Been More Positive? Recently released preliminary estimates are that real GDP growth in the third quarter was an unexpectedly strong 3.9 percent, buoyed particularly by exports and surprisingly by consumer spending, and well above the sub 3 percent pace anticipated by most economists. In addition, growth in payroll employment in October was surprisingly strong, the unemployment rate held steady, and productivity growth was good. Despite these recent positive reports, however, most economists believe that the economy is currently in a slowing mode. It was in recognition of this that the Federal Reserve recently reduced its key interest rate by three–quarters of a percent. A variety of data show underlying economic softness in a number of areas. For example:

- Despite October’s good payroll jobs report, the number of new jobs created over the past three months averaged only 60 percent of what occurred a year ago.

- An alternative jobs measure—the employment survey of households—showed a loss in October of 250,000 workers, its third decline in the last four months.

- The manufacturing sector was barely growing in October, seen by some as evidence that the impact of the slowdown in the housing and financial sectors has started spilling over into manufacturing.

- Real spending and real disposable incomes both slowed in September.

- Core inflation in September was holding steady at a modest 1.8 percent 12–month increase, consistent with slack conditions in the labor and product markets.

The Bottom Line—Softness Despite Uncertainties and Mixed Signals. Given such factors, most economists expect a significant slowing to occur in the fourth quarter. In addition, considerable uncertainty exists, as evidenced in some of the recent large daily stock market swings and gold price movements.

A number of factors appear to have been contributing to the current economic slowing, such as overextended consumer balance sheets caused both by past high levels of borrowing and low savings rates. The most important, however, is the continuing and deepening turmoil in the housing and mortgage credit markets, followed by recent significant increases in crude oil prices.

The Forecast—Subdued Growth in 2008 With Some Rebound in 2009

Led by continuing problems in the housing sector and high oil prices, we expect the overall economy to be depressed in 2008 with GDP growth below 2 percent through much of the year. Figures 1 and 2 earlier show that, for 2008 as a whole, real GDP growth is forecast to be only 1.9 percent, before rebounding to 2.9 percent in 2009 and ranging between 2.4 percent and 2.9 percent for the rest of the forecast period. The economy is expected to be particularly weak in the first half of 2008, largely due to intensification of the housing correction currently underway. Figure 2 also shows that our projected growth has been reduced significantly from what was assumed in the 2007–08 Budget Act. The main components of our forecast are as follows:

- Real consumer spending growth will slow from 2.9 percent in 2007 to 2 percent in 2008, before partially rebounding to an average annual pace of around 2.8 percent during the balance of the forecast period.

- New vehicle sales will be soft, reflecting both subdued income and job growth as well as high gasoline prices. We forecast that unit sales of new light vehicles (automobiles and light trucks) will drop in 2008 to 15.9 million, their third straight annual decline.

- Residential construction spending adjusted for inflation, following a nearly 17 percent drop in 2007, is forecast to fall by another 19 percent in 2008, before rising by a modest 5.9 percent in 2009. Thereafter, growth is forecast to stabilize at around 10 percent annually. The greatest volatility over the forecast period will be associated with the single–family portion of the market.

- Housing starts themselves are predicted to drop to only 1.1 million units in 2008. This is down from the reduced level of 1.3 million units in 2007 and the nearly 2 million average level of the three years before that. They will then rebound partially to 1.4 million units in 2009 and settle–in at about 1.7 million units for the following several years. As shown in Figure 3, the 2008 level will be a near–record low, primarily reflecting the sharp fall–off in single–family units.

- Nonresidential construction is expected to take up at least some of the slack caused by the housing slump and partially offset the weakness in residential construction, despite the weaker economy and soft corporate profits. This has already been occurring, in part reflecting the freeing–up of construction resources due to the housing downturn.

- Real business investment growth will continue to slow further to 2.2 percent in 2008, from 3.8 percent in 2007, and 6.6 percent in 2006. After this, it should stabilize at close to 4 percent for the remainder of the forecast period. Of special note is that real spending on information technology equipment and software is expected to remain healthy—a plus for California which has a large number of firms and workers which design and produce computer and software products.

- Oil prices experienced a sharp rise during 2007 and recently reached record highs. As shown in Figure 4, the inflation–adjusted average price of imported oil (which applies to most of the oil we use) is currently at its all–time quarterly peak that was reached more than 25 years ago. We anticipate oil prices to continue to experience quarterly volatility but remain high throughout the forecast period, averaging roughly $80 per barrel. Given the oil–price outlook, gasoline prices also are expected to remain high during the forecast period. While gasoline prices are expected to continue to follow traditional seasonal volatility patterns, their annual summertime peaks are forecast to remain in the range of $3 per gallon. The high oil and gasoline prices we are forecasting will clearly be a drag on the rate of overall economic growth, but are not expected to derail the expansion.

- Inflation is one of the positive elements in the outlook, as it is predicted to be relatively modest despite high oil and gasoline prices. After steadily dropping in the past several years—from 3.4 percent in 2005 to 3.2 percent in 2006, and an estimated 2.7 percent in 2007—growth in the Consumer Price Index is predicted to settle–in at about 2 percent for the forecast period. Despite some pressure from selected areas like energy and medical costs, core inflation (which excludes energy and food costs) will be held down by such factors as soft housing cost increases and slack in the nation’s product and labor markets caused by subdued economic growth and the housing correction.

- Interest rates are projected to dip modestly in 2008 as economic growth and inflation eases, but then firm back up in 2009 and increase slightly thereafter as the economy strengthens.

The California Economy

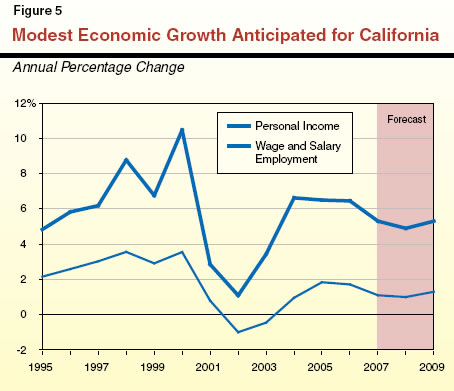

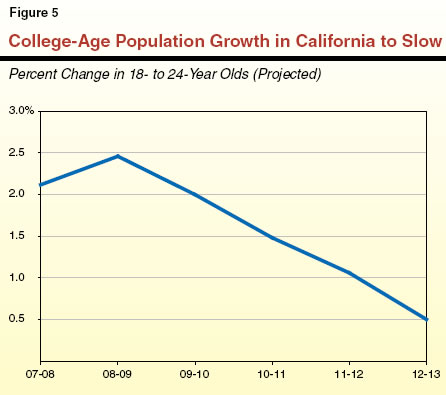

The current economic situation and outlook for California are generally similar to the nation as a whole, although the turmoil in the state’s housing and mortgage markets has been more pronounced than nationally, making its outlook a bit more sluggish. Economic growth in 2008 is expected to be slow, especially in the first half of the year, with recovery beginning later in the year and continuing into 2009. Figure 1 earlier shows our forecast for selected California economic variables, while Figure 5 shows our growth pattern for the forecast period and earlier years for two key variables—personal income and wage and salary employment.

Recent Evidence of Slowing

After healthy gains in 2004 through 2006, a variety of economic indicators suggest that economic growth slowed for the state as 2007 progressed. For example, growth in both wage and salary employment and taxable sales declined, the unemployment rate rose, and new residential building permits dropped.

Key Factors Behind Slowdown—Real Estate and Energy

The key forces behind the economic slowdown that is being experienced in California are the same as for the nation—namely, sharply declining real estate markets and, to a somewhat lesser though still–important degree, high energy and gasoline prices. In fact, the adverse effects of these negative forces tend to be even greater in California than for the rest of the country, reflecting (1) the state’s growth–oriented and highly cyclical real estate sector, which generally has expanded more in boom years and fallen further than the rest of the country during downturns, and (2) its higher–than–average gasoline prices and gasoline consumption.

While both of these factors are expected to negatively impact California’s economic performance in 2008 and 2009, this is especially true for the real estate sector. As discussed in the nearby box, a major real estate correction is currently underway that is expected to get worse before it runs its full course. Although its initial major adverse effects appear to be primarily falling on homeowners, housing–related industries, and financial institutions directly involved, there will undoubtedly also be various eventual negative spillover effects on the economy at large.

The Real Estate Situation

California’s real estate–related industries—which include developers, contractors, real estate brokers, financial institutions, title companies, and insurers—have in recent years accounted for roughly 15 percent to 20 percent of the state’s private sector economy. Changes in real estate asset values and mortgage refinancing activity can also have substantial indirect impacts on other sectors of the economy, such as consumer spending.

Major Real Estate Correction Underway

California is now in the midst of a major real estate correction, in part due to the state’s overheated housing market and in part to the sub–prime mortgage market crisis that followed the early 2000s’ housing boom.

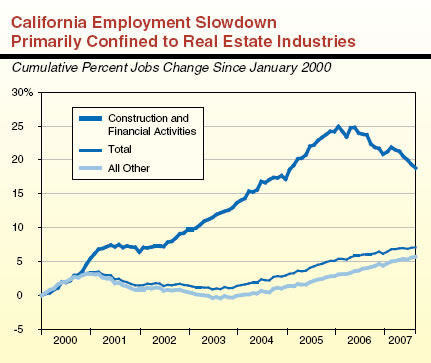

Record Upswing. . . The state experienced an unprecedented boom in its real estate markets between 2001 and 2005, fueled not only by basic demand for housing by California’s growing population, but also speculation by real estate investors and increased use of sub–prime mortgage loans and risky lending standards to facilitate home buying by marginally qualified purchasers. During this period, inflation–adjusted home prices doubled, sales reached all time highs, and new construction registered its highest levels in nearly 15 years. As shown in the figure, these increases dramatically boosted employment during this period (and as a result of this, incomes and spending), both in those sectors most closely tied to real estate–related activities and California’s economy generally.

. . .Then the Bubble Burst. California’s real estate market peaked in mid–2005, however, and since then, home sales and new construction activity have fallen sharply and by proportionally more than for the rest of the nation. The growing number of mortgage delinquencies, outright foreclosures, rising unsold home inventories, and regions experiencing flat or declining home prices, indicate that further intensification of the housing correction and related softness in building activity are in store. This is particularly true because many of the mortgage loans written near the peak of the boom with temporarily favorable interest rates will have their rates reset at higher levels in the near future. Equally important, many homeowners who were recently approved loans without the long–term ability to realistically afford them, due to relaxed lending standards, will be finding it increasingly difficult to make their payments. Exacerbating the problem is the softness in housing prices, which has precluded many distressed owners from refinancing or having access to home equity. All of these factors will be putting increased financial pressures on the homeowners and financial institutions involved.

How Will the Economy Be Affected?

These problems involving the real estate industry and related financial sector will have major adverse impacts in a number of ways. For example, many realtors, developers, contractors, and real estate lenders in California will lose income for at least the next couple of years, and the profits of certain financial firms will be negatively impacted. Likewise, reductions in home values will adversely affect the financial condition of many households, which will likely slow consumer spending. Adverse economic effects will also result from the casualties of the meltdown in the sub–prime mortgage market, including displaced homeowners and financial investors having lost money. Among the industries most vulnerable are home–related financials, producers of home furnishings and appliances, and manufacturing operations related to home construction—such as wood products, cement, steel fabrication, and furniture.

So Far, However, Employment Losses Still Relatively Concentrated. As shown in the figure, thus far the job–related losses California has experienced beginning a couple of years ago have largely been confined to real estate–related industries such as construction and financial services, and not spread more broadly to other areas of the economy. Many economists would expect, however, that eventually various spillover effects on the economy at large will materialize to some degree.

Regional Effects Will Vary. The effects on the economy also will vary geographically, depending on such factors as the prevalence of high–risk loans granted in different regions and the amount of speculative housing activity characterizing them. For example, the Central Valley and Inland Empire appear particularly at risk. An analysis by the Wall Street Journal found that 12 California metropolitan areas, most of them inland, rank in the top 45 nationally in terms of the percentage of loan volume issued in 2006 that is high risk. |

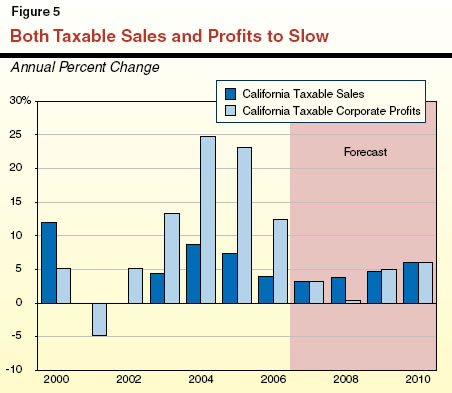

Specifics of the Forecast

As shown previously in Figure 1 and Figure 5, our outlook for California includes the following forecasts for specific economic variables:

- Personal income growth is predicted to slow, from 6.5 percent in 2006 to 5.3 percent in 2007 and then to 4.9 percent in 2008. We see it then partially rebounding to 5.3 percent in 2009 before averaging roughly 5.6 percent through the remainder of the forecast period.

- Wage and salary employment growth is predicted to drop significantly, from 1.7 percent in 2006, to 1.1 percent in 2007, and a bit further to 1 percent in 2008. Thereafter, it is forecast to accelerate slightly to 1.3 percent in 2009 and average 1.7 percent for the rest of the period.

- Taxable sales growth is expected to be soft in 2008 at 3.8 percent following 2007’s very weak 3.2 percent, before firming up a bit in 2009 at 4.7 percent. In all three of these years, taxable sales growth is expected to be well below that of personal income.

- New residential building permits are expected to bottom–out in the vicinity of 120,000 units in both 2007 and 2008.

How Will Individual Sectors Do? Performance by industry will vary. The weakest areas will clearly involve real estate–related industries such as residential construction and finance. In contrast, solid growth should occur involving international trade, which is benefiting California manufacturers and farmers that sell abroad, as well as transportation, warehousing, and distribution activities associated with trade activity through California’s ports. Likewise, continued strength is foreseen for information–related industries (including motion pictures, sound recordings, publishing, and Internet service providers). Healthy growth in California’s high–tech and related professional services industry is also expected, including software development, computer systems and design, biotechnology, and pharmaceuticals.

Risks to the Outlook

Although our forecasts for the nation and California are what we believe to be the most likely economic outcomes, there are both inherent risks and uncertainties in the outlook. The main ones continue to involve housing and energy.

- On the housing front, California continues to be in uncharted territory in terms of exactly where the current market correction will end up regarding home prices and building activity, as well as how long it will take for the correction to run its course. For example, our forecast assumes that price and construction declines will not become extreme by historical standards, reflecting the overall long–term positive outlook for California’s economy. However, steeper reductions could occur, which in turn would further depress economic growth in the state over the next couple of years.

- Regarding energy costs, the main concern is that recent sharp increases in oil prices might continue, due to such factors as the market’s vulnerability to unexpected supply disruptions, rising political tensions in various global regions, and increasing worldwide demand for oil as China and certain other nations continue to rapidly industrialize. Gasoline prices also are always vulnerable to supply disruptions involving not only crude oil, but also refinery operations. Adverse developments in these areas could place upward pressures on inflation and interest rates, as well as significantly disrupt economic activity generally.

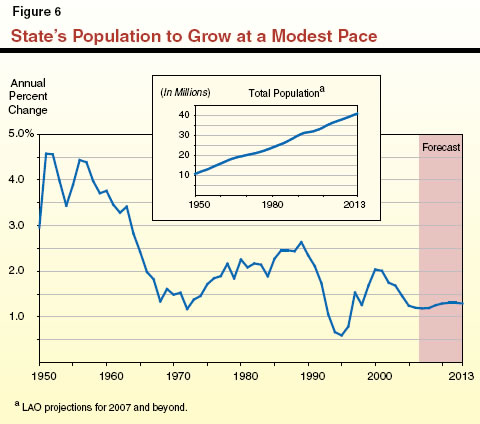

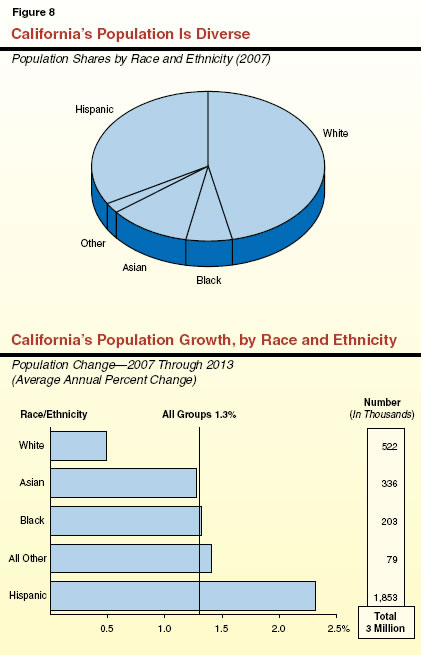

The Demographic Outlook

California’s population currently totals approximately 38 million persons. During the six–year forecast period covered in this report, Figure 6 shows that the state’s population growth is projected to average a bit under 1.3 percent annually. In terms of numbers of people, this modest annual growth rate translates into about 500,000 people yearly, and is roughly equivalent to adding a new city the size of Long Beach to California each year. As a result, California will add about 3 million people over the forecast interval and reach over 40 million by 2013.

The population growth rate we are projecting, while slightly more than for the last couple of years, is somewhat slower than that experienced in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when annual growth was averaging about 1.6 percent. This reflects a number of factors, including the dampening effects of the large housing price increases and more subdued employment growth rates of recent years on in–migration. Another factor is the reduced birth rates being recorded by certain segments of California’s female population.

Population Growth Components

California’s population growth can be broken down into two major components—natural increase (the excess of births over deaths) and net in–migration (persons moving into California from other states and countries, minus those leaving California for out–of–state destinations). On average, these two components have tended in the past to contribute about equally over time to the state’s population growth. However, their relative shares can vary significantly from one year to the next depending largely on the strength of the net in–migration component—by far the most volatile element. For example, during the past several years, in–migration has accounted for about 30 percent of California’s annual population change, reflecting a sharp drop in growth from interstate population flows.

Natural Increase. We project that the natural–increase component will average close to 315,000 new Californians annually over the forecast period. This net natural gain reflects an average of somewhat over 565,000 births annually partially offset by somewhat over 250,000 deaths annually.

Our forecast incorporates the well–documented trend of declining birth rates that has been in effect for essentially all ethnic groups in recent years in California. Despite these declining birth rates, however, the number of new births in our forecast actually trends up a bit through 2013. This is due to significant growth in the female population of child–bearing age groups in the faster–growing segments of California’s population, including Hispanic and Asian women. As a result, even after accounting for growth in the number of deaths occurring annually in California, we project that the natural increase component will grow slightly during the latter half of the forecast period.

Net In–Migration. We project that combined domestic and foreign net in–migration will average roughly 185,000 annually over the next six years. This is less than during the latter half of the 1990s and in the early 2000s, when annual net in–migration averaged about 260,000. It also is considerably less than the projected 315,000 natural–increase component noted above. Regarding this in–migration:

- Most of the net in–migration we are projecting reflects foreign net in–migration from other nations. This component has been relatively stable over the past decade and has proved to be less sensitive to the economy than domestic population flows between states. We forecast net foreign in–migration will be fairly constant through 2013, averaging about 200,000 annually.

- Regarding domestic net in–migration, this is arguably the single most difficult demographic variable to forecast at this time. The available data indicate that this component turned negative starting in 2004 (that is, more people left California for other states than flowed–in from them), and became even more so in the following couple of years, reaching over 78,000 in 2006. In large part, this appears attributable to California’s continued modest job growth and high home prices. Our forecast is for continued net domestic out–migration in the short term. Although we do expect the net domestic outflows to taper off and eventually reverse themselves, we do not foresee a return to net interstate population in–flows for several years. And, after this, only modest net domestic in–flows of 5,000 annually are anticipated toward the end of the forecast period. Over our entire forecast interval, net domestic out–migration will average close to 20,000 annually.

Growth to Vary Significantly By Age Group

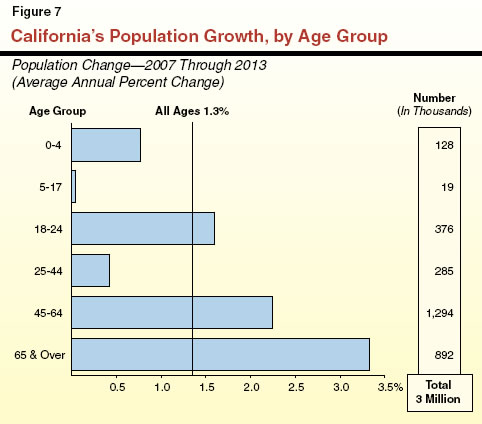

Figure 7 shows our population growth projections by broad age categories, including both numerical and percentage growth.

“Baby Boomers” Swelling 45–to–64 Age Group. The 45–to–64 age group (largely the baby boomers) continues to be by far the fastest growing segment of the population numerically and the second–fastest percentage wise. Nearly 1.3 million new people are expected to move into this age category over the next six years for an annual average growth of 2.2 percent.

Slow Growth for Children. At the other extreme, slow growth—well under 1 percent—is anticipated for preschoolers and the K–12 school–age population. This reflects several factors. One is the movement of children of the “baby–boom” generation beyond the upper–end of the 5–to–17 age group, which partially explains the above–average growth in the 18–to–24 age category. Other factors include the slower rate of net in–migration, and the decline in birth rates in recent years that has reduced the number of children moving into the preschool and school–age categories.

Rapid Growth for the Elderly. The single–fastest–growing age group percentage wise and second–fastest numerically is the 65–and–over category, reflecting the well–known “graying” of the population. This cohort is expected to increase at an annual average pace of 3.3 percent.

Fiscal Effects. These various age–group demographic projections can have significant implications for the state’s revenue and expenditure outlook. For example, strong growth of the 45–to–64 age group generally benefits tax revenues since this is the age category that routinely earns the highest wages and salaries. Likewise, the growth in the young–adult population affects college enrollments, those for the 0–to–4 and 5–to–17 age groups drives K–12 enrollment growth, and that for the elderly impacts medical care costs.

Other Demographic Features

In addition to age, projected population growth will also differ markedly along other dimensions. For example:

- Racial/Ethnic Variation. Figure 8 indicates that California’s population is very diverse in terms of its racial/ethnic composition. In addition, the amounts and rates of population growth along these dimensions will differ significantly for different groups. The Hispanic population is forecast to experience especially strong growth, averaging over 2.3 percent annually and accounting for over 60 percent of California’s total population growth between 2007 and 2013.

- Geographic Variation. Rates of growth will be above average for the state’s Central Valley, Inland Empire, and foothills areas. This will occur as the availability of land allows population to continue to “fill in” and attract people from the more–congested coastal areas within the state. Such high–growth regions will increasingly face new challenges in providing the public services and infrastructure to accommodate growth.

Chapter 3

Revenue Projections

The revenues that finance California’s state General Fund budget come from numerous sources, including taxes, fees, licenses, interest earnings, loans, and transfers. However, almost 95 percent of the total is attributable to the state’s “big three” taxes—the personal income tax (PIT), the sales and use tax (SUT), and the corporation tax (CT). In this chapter, we summarize our updated General Fund revenue projections and provide detail behind our key revenue–related assumptions. We also discuss the outlook for property taxes in the shaded box below. Although a local revenue source, these property tax revenues have significant implications for the state budget due to their effects on General Fund spending on Proposition 98.

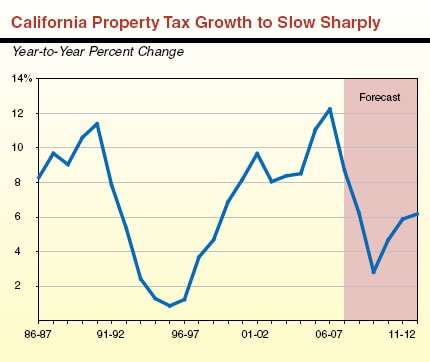

Outlook for Property Taxes—Much Slower Growth

Property taxes are projected to total $47 billion during 2007–08, making it the second–largest state–local government revenue source in California. In the current year, about one–third of property tax revenues will go to schools, while the remainder will be apportioned among cities, counties, and special districts. Under Proposition 13, real property (land and buildings) is reassessed to market value only when it changes ownership. Otherwise, the assessed value grows by no more than 2 percent a year. An assessment also can be reduced (through a process initiated by the assessor or property owners under Proposition 8) when the estimated market value of a property falls below its assessed value.

Despite the dedication of property tax revenues to local governments, the state is affected by changes in local property taxes. Under Proposition 98, state funding for K–14 education is generally offset, dollar–for–dollar, by the amount of local property taxes available to school and community college districts.

Property Taxes Grew Rapidly in Recent Years. . .

The recent real estate boom of the early 2000s led to more than a 60 percent increase in local property tax revenues between 2001–02 and 2006–07, and about a 40 percent real increase after adjusting for inflation. The inflation–adjusted increase is the largest of any same–length period since the passage of Proposition 13 in 1978. This unprecedented growth resulted from increased property assessments, and has had beneficial impacts on both state and local government finances in recent years. The large increase over the period reflects a combination of soaring real estate prices and historically high sales rates (both of which led to large reassessments), and large increases in new construction activity. Property turnover was responsible for the largest share of revenue growth during this period.

. . . But Much Slower Growth Is Forecast

During the boom years, annual statewide property tax growth averaged nearly 10 percent (see accompanying figure), reflecting assessment growth. However, the slowdown in the real estate market that is currently underway in California and we see as intensifying, will lead to much slower growth in assessed property values, and thus property tax revenues, during the next several years. Factors leading to lower growth include (1) a reduced level of property sales (and hence fewer upward assessments of property to their current market values), (2) less new construction, and (3) less average growth in assessed values for property that is sold. Depending on the magnitude of future price declines in the real estate market, downward assessments (under the Proposition 8 process) of certain recently purchased property also will have a negative impact on assessed values during the next several years. This has already been occurring, with tens of thousands of properties having been reassessed downward by billions of dollars statewide.

As shown in the figure, and consistent with our forecast for assessed value growth, we are projecting that annual growth in property taxes will slow sharply in the near term—from 12 percent in 2006–07 to below 9 percent in 2007–08, about 6 percent in 2008–09, and about 3 percent in 2009–10—before rebounding modestly in subsequent years. Our forecast, however, is highly dependent on the length, scope, and severity of the correction in the real estate market, and our figures could be significantly overstated if the slump proves to be more pronounced than we are assuming. For example, each 1 percentage point reduction in the rate of growth in statewide assessed values translates into over $450 million of ongoing reduced local property tax revenues annually, and roughly $150 million of increased yearly General Fund Proposition 98 obligations.

|

|

Recent Developments and Overall Outlook

Revenues have been falling short of expectations since the 2007–08 Budget Act was adopted, largely reflecting the state’s weaker economic performance than was predicted last May when the budget’s economic and revenue forecasts were put together. Preliminary estimates indicate that revenues in 2006–07 fell short of the 2007–08 Budget Act estimate by $435 million. Likewise, tax receipts during the first quarter of 2007–08 fell short of their estimate by over one–half a billion dollars, with all of the largest revenue sources coming in low. Partial–month receipts for the month October were also down, by another several hundred million dollars. Given this combination of weakness in the economy and accumulating shortfalls in cash receipts, we have revised our projections for General Fund revenues downward—and by a significant amount.

Key Revenue Components Are Exhibiting Weakness

Looking broadly at the different components of the revenue base, many of the main ones have showed softness thus far in 2007–08 compared to estimated levels. For example:

- Although PIT withholding receipts are running slightly ahead of their estimate (up $77 million through October relative to their $10.7 billion 2007–08 Budget Act estimate), the remaining sources of PIT monies, such as tax prepayments by high–income individuals on their investments, are down by about $450 million after adjusting for cash–flow anomalies.

- Receipts under CT were down over the same period by $160 million for prepayments (5.4 percent from their estimate) and $60 million from all sources, suggesting softness in taxable corporate profits.

- SUT receipts were down by about $440 million through October. Although some of this shortfall may be related to the Southern California fires, it also is consistent with taxable sales growth having been lower than projections, averaging less than 2 percent in recent quarters.

The Bottom Line on Revenues— Significant Downward Adjustment

Based on recent cash and economic developments, and their future implications, we have significantly reduced our projected revenues relative to the 2007–08 Budget Act forecast. Figure 1 shows our updated revenue estimates for the prior year (2006–07) and current year (2007–08), and compares them to the projections assumed in the 2007–08 Budget Act. Figure 2 shows our revenue projections for the entire forecast period, ending in 2012–13.

Figure 1

Revised LAO Revenues for 2006-07 and 2007-08

Compared With 2007-08 Budget Act |

(In Millions) |

|

|

2006‑07 |

|

|

|

2007‑08 |

|

Revenue Source |

Budget Act |

LAO |

Difference |

|

Budget Act |

LAO |

Difference |

Personal Income Tax |

$52,243 |

$51,636 |

-$607 |

|

$55,236 |

$54,227 |

-$1,009 |

Sales and Use Tax |

27,787 |

27,445 |

-342 |

|

28,820 |

28,196 |

-624 |

Corporation Tax |

10,717 |

11,062 |

345 |

|

11,055 |

10,669 |

-386 |

Other revenues and transfers |

5,266 |

5,435 |

169 |

|

7,151 |

5,823 |

-1,328 |

Total Revenues and Transfers |

$96,013 |

$95,578 |

-$435 |

|

$102,262 |

$98,916 |

-$3,346 |

Figure 2

The LAO's General Fund Revenue Forecast |

(Dollars in Millions) |

Revenue Source |

2006-07 |

2007-08 |

2008-09 |

2009-10 |

2010-11 |

2011-12 |

2012-13 |

Personal Income Tax |

$51,636 |

$54,227 |

$56,754 |

$60,151 |

$64,121 |

$68,345 |

$73,005 |

Sales and Use Tax |

27,445 |

28,196 |

29,560 |

31,198 |

33,082 |

35,085 |

37,184 |

Corporation Tax |

11,062 |

10,669 |

11,337 |

12,006 |

13,088 |

14,021 |

14,953 |

Other revenues and transfers |

5,435 |

5,823 |

5,861 |

5,637 |

6,816 |

7,511 |

7,744 |

Total Revenues and Transfers |

$95,578 |

$98,916 |

$103,512 |

$108,991 |

$117,108 |

$124,962 |

$132,886 |

(Percentage Change) |

2.3% |

3.5% |

4.6% |

5.3% |

7.4% |

6.7% |

6.3% |

2006–07 Revenues—Down $435 Million. Based on preliminary reports by both the State Controller and the state’s tax agencies for 2006–07, we estimate that General Fund revenues and transfers totaled $95.6 billion during the year—a 2.3 percent rise from 2005–06. As Figure 1 shows, this is down $435 million from the level assumed in the 2007–08 Budget Act. This change reflects the net effect of a variety factors, including accrual adjustments. About $600 million of the reduction is from taxes, partially offset by a gain from other revenues. The main reason for the gain in the other revenue category is attributable to prior–year Medi–Cal quality assurance fee revenue being recognized on a one–time basis in 2006–07.

2007–08 Revenues—Down $3.3 Billion. We project that General Fund revenues and transfers will total $98.9 billion in 2007–08, a 3.5 percent increase from 2006–07. As Figure 1 shows, our revised revenue total is down by $3.3 billion from the estimate contained in the 2007–08 Budget Act. This drop consists of declines in taxes of $2.1 billion—including $1 billion from PIT. The remaining $1.2 billion of the drop is primarily due to (1) reducing the $1 billion in assumed 2007–08 revenues from the sale of EdFund to $500 million, and moving it out of the current year and into 2008–09 (please see related discussion in Chapter 1) and (2) declines of about $200 million each in estimated revenues from tribal gambling activity and child support–related revenues, partially offset by gains from oil royalties and in interest income.

2008–09 Revenues—Modest Growth. As shown in Figure 2, we forecast that total General Fund revenues and transfers will be $103.5 billion in 2008–09, a 4.6 percent increase from the current year.

2009–10 Through 2012–13. We project that revenue growth will accelerate modestly in 2009–10 to 5.3 percent, and then rise a bit and average about 6.8 percent annually through 2012–13. This assumes the return of the state’s “pick–up” estate tax, which is scheduled under current law to come back into effect January 1, 2011. Without this estate–tax factor, revenue growth beyond the budget year would average about 6 percent, or slightly more than our projected personal income growth of 5.9 percent for the period—as typically occurs during periods of economic expansion.

Detail on Individual Revenue Sources

Personal Income Tax

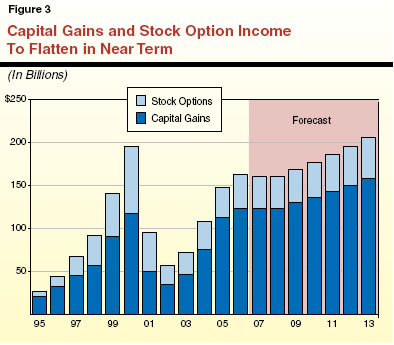

We estimate that PIT receipts totaled $51.6 billion in 2006–07 (a modest 3.5 percent increase from the year before) and will grow to $54.2 billion in 2007–08 (a 5 percent gain from the prior year). The PIT revenues are projected to grow further to $56.8 billion in 2008–09, a 4.7 percent increase from the budget year, and at an average annual rate of 6.5 percent thereafter.

Key Forecast Factors. As noted earlier, our PIT forecast for 2007–08 is down by $1 billion relative to the 2007–08 Budget Act forecast. Part of this drop is related to the across–the–board shortfall reported thus far in receipts for all PIT components except for withholding. This includes estimated, final, and miscellaneous payments, which are very much affected by payments of high–income individuals, including those with large amounts of bonus and investment income, capital gains, and stock options. As shown in Figure 3, we accordingly have assumed a relatively flat forecast for both capital gains and stock options in 2007 and 2008. This is consistent both with recent cash trends and economic and financial developments influencing these income sources.