February 2008

From Cellblocks to Classrooms: Reforming Inmate Education To Improve Public Safety

According to national research, academic and vocational programs can significantly reduce the likelihood that offenders will commit new offenses and return to prison. Despite these findings, the state offers these programs to only a relatively small segment of the inmate population. Moreover, the inmate education programs that do exist suffer from a number of problems that limit their effectiveness at reducing recidivism. To improve prison education programs and public safety, we recommend several structural reforms to increase the performance, outcomes, and accountability of the existing inmate education programs, as well as ways to expand their capacity at a low cost to the state.

Executive Summary

The Value of Correctional Education

Each year, more than 120,000 California state prisoners are released back into society after serving their prison sentences. As part of its mission, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) provides a number of services to prison inmates that are intended to improve their likelihood of leading a productive, crime–free life upon release to the community. One such service is education. Various studies show that correctional education potentially offers many benefits and, when good programs are implemented, can offer benefits that more than offset their costs.

Remedial Work Required for CDCR Education Programs

This report finds significant shortcomings in the state’s provision of education programs for adult inmates in California prisons. Specifically, we have found low student enrollment levels compared to the number of inmates who could benefit from these programs, inadequate participation rates by inmates, a flawed funding allocation methodology, ineffective case management, and lack of regular program evaluation. Together, these problems mean that the state’s significant investment in prison education programs is not returning the full benefits possible in the forms of lower state costs and improved public safety.

LAO Recommendations

We recommend the Legislature take several steps to improve adult prison education programs in the near term. In particular, we recommend that the state fund these programs based on attendance rather than enrollment, develop incentives for inmate participation in programs, and develop routine case management and program evaluation systems. These recommendations would better leverage the state’s existing investment in prison education programs to increase the number of inmates who participate as well as improve the quality of the programs provided. In addition, we recommend that after the state has improved the structure of its existing programs, it consider some alternatives to expand the capacity of correctional education programs. The single most significant way to expand capacity at little or no cost to the state would be to place inmates in education and work programs for half days, thereby maximizing participation through utilizing existing resources.

LAO Recommendations to Improve

State’s Correctional Education System |

|

✔ Structural changes to ensure program performance and CDCR accountability |

Fund programs based on actual attendance, not enrollment. |

Develop incentives for inmate participation and achievement. |

Fill teacher vacancies. |

Limit the negative impact of lockdowns on programs. |

Develop a case management system that assigns inmates to most appropriate programs based on risk and needs. |

Base education funding decisions on ongoing assessments of programs. |

✔ Address structural problems first, expand programs later |

✔ Future options to increase enrollment |

Create half-day programs. |

Partner with Prison Industries Authority to build program space. |

Other opportunities to expand education programs. |

The Value of Correctional Education

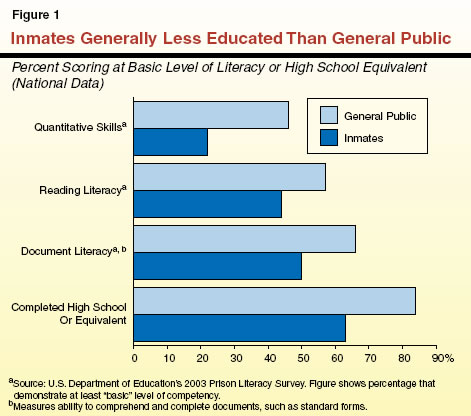

Programs Can Improve Level of Educational Attainment. Research demonstrates that inmates on average have lower educational achievement than the general public. As shown in Figure 1, for example, prison inmates nationally scored significantly lower than the general public on various measurements of literacy in a recent study by the U.S. Department of Education. In addition, adult prison inmates in the United States are significantly less likely than the general public to have obtained a high school diploma or its equivalent. Evaluations conducted by the CDCR have similarly found that only one–quarter of the state’s inmate population can read at the high school level. In fact, inmate test scores showed that the average California inmate reads at the seventh grade level upon entry to prison.

Importantly, many research studies have shown that inmates who participate in correctional education programs can experience significant improvement in test scores, as well as other education–related outcomes, such as earning diplomas and obtaining employment. For example, New York reports that in 2005 about 11,000 of its state inmates enrolled in education programs improved reading or math scores to at least a sixth or ninth grade level. Another 2,300 earned the equivalent of a high school diploma.

Prison Education Benefits Public Safety. Correctional researchers and administrators have long been aware of the strong correlation between low educational attainment and the likelihood of being incarcerated. Recent research indicates that correctional education programs can significantly reduce the rate of reoffending for inmates when they are subsequently returned to the community.

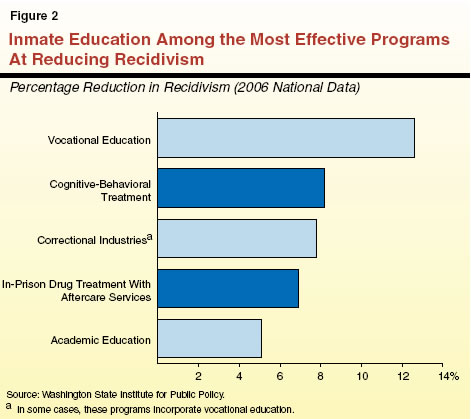

For example, one widely cited study that analyzed education programs in three states (Ohio, Maryland, and Minnesota) found that inmates who had participated in prison education programs were reincarcerated 10 percent less often on average than a comparison group of inmates who did not. Several evaluations have demonstrated that correctional education programs increase employment rates and wages of parolees, both factors correlated with reduced recidivism. For example, one research study that compiled data from evaluations of 16 educational programs from various states found that program participants were two times more likely to be employed after release than inmates that did not participate in education programs. As shown in Figure 2, another study found that inmate education programs ranked among the most successful strategies for reducing inmate recidivism. Specifically, this research found that vocational education, correctional industries, and academic education all significantly reduce the recidivism rate of participating inmates after they are released from prison. However, some inmate education programs have been shown to be more effective than others. For example, researchers found vocational education to be more than twice as effective as academic education at reducing recidivism.

These findings are of particular importance in California, where, in 2006, almost 120,000 inmates were released from prison, and there were more than 90,000 “parolee returns” to prison for committing new crimes or parole violations.

Inmate Education Improves Prison Management. In addition, many corrections officials from California and other states have advised us that prison programs, including education, make it easier for prison administrators to safely manage the inmate population. According to these officials, inmates are less likely to engage in disruptive and violent incidents when they are actively engaged in a program instead of being idle. Importantly, this can result in improved safety for state employees, as well as inmates, and result in lower prison security, medical, and workers’ compensation costs.

Other Fiscal Benefits for State and Local Governments. To the extent that inmate education programs reduce rates of reoffending as the research indicates, these programs can also result in direct and indirect fiscal benefits to state and local governments. The direct fiscal benefits primarily include reduced state court and incarceration costs, as well as a reduction in local costs for criminal investigations and jail operations. The indirect fiscal benefits can include reduced costs for assistance to crime victims, less reliance on public assistance by families of inmates, and greater income and sales tax revenues paid by former inmates who successfully remain in the community.

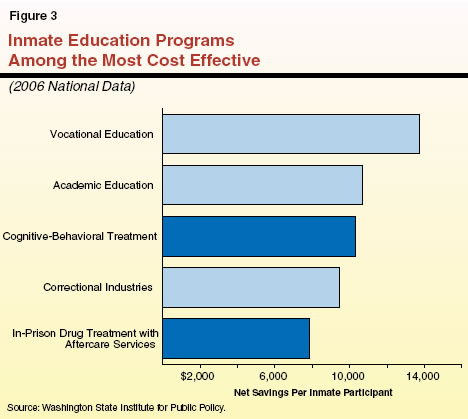

Some academic research suggests that—taking all of these factors into account—offering services to inmates in prison (commonly referred to as “programming”) generates net savings. That is, they have concluded that these programs result in more fiscal savings to society in the long run than they cost to provide. Figure 3 shows the net savings that result from correctional education programs compared to other prison programs. According to this analysis prepared by the Washington State Institute for Public Policy (WSIPP), inmate education programs are among the most cost–effective correctional strategies for reducing recidivism. For example, WSIPP estimated that vocational education programs generate an average of $14,000 in net savings per inmate participant. These findings suggest that successful education programs can generate $2 to $3 or more in savings for every dollar invested to implement them.

The CDCR Education System

Inmate Education Required By State Laws

Several statutes govern the provision of CDCR education programs and make such rehabilitation programs a part of the department’s mission. For example, California Penal Code 2053, enacted in the late 1980s, states the intent of the Legislature “to raise the percentage of prisoners who are functionally literate, in order to provide for a corresponding reduction in the recidivism rate.” To accomplish this objective, state law requires that the department have a statewide education plan and that every state prison provide literacy programs designed to ensure that inmates achieve a ninth grade reading level before they are paroled.

In 2005, the Legislature and Governor enacted Chapter 10, (SB 737, Romero), which reorganized and consolidated state correctional departments. One purpose of this reorganization was to increase the importance of rehabilitation programming, including education programs, within the department. The reorganization attempted to achieve this by emphasizing rehabilitation as part of the department’s mission.

More recently, the Legislature adopted Chapter 7, Statutes of 2007 (AB 900, Solorio), which requires CDCR to implement a number of improvements to rehabilitation programs generally, and to inmate education programs specifically. Among other changes, Chapter 7 includes requirements to increase inmate education participation rates, reduce teacher vacancies, and conduct risk and needs assessments of inmates sent to prison.

Education Programs Offered by CDCR

The department’s adult education system is based on the public school district model. The central CDCR Division of Education and Vocations Programs functions as a statewide school district office headed by the division’s director. Each prison operates its education program as an individual school composed of academic, vocational, and life–skills instruction, staffed by teachers, librarians, and support staff. Due to the constant entry and exit of inmates from prison and the classroom, the CDCR organizes classes on a model that provides an individualized, self–paced program for each inmate. Department staff develop standardized curricula for education programs, and a departmental committee is responsible for ensuring that the curricula conforms with the adult curriculum frameworks established by the California Department of Education. Each prison’s education program is accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges, an association that provides accreditation to schools in the general community. Academic teachers in CDCR must have state teaching credentials.

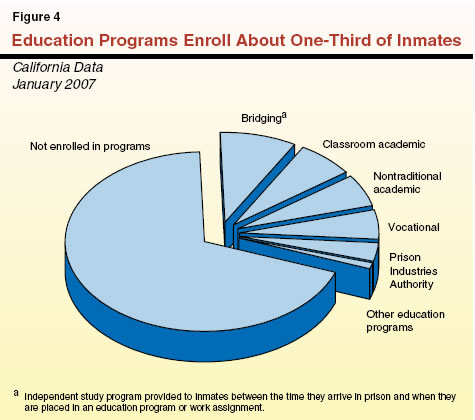

The CDCR has approximately 54,000 inmates enrolled in education programs, about 31 percent of the total inmate population. These programs include academic and vocational education programs, correctional industries, and independent study programs, among others. Figure 4 shows the enrollment of each type of correctional education program now taught in California prisons. Each of these types of programs is described in more detail below.

Classroom Academic Education. Nearly all state prisons offer academic education programs in traditional classroom settings taught by state–certified teachers, generally on a ratio of 27 students per teacher. These classes are primarily composed of Adult Basic Education courses which focus on teaching basic literacy (for example, reading and math) and cognitive skills for inmates who read below the ninth grade reading level. In addition, the department offers classes for inmates with limited English proficiency and developmental disabilities, as well as classes that assist inmates in earning a high school diploma or General Education Development (GED) certification (which provides the equivalent of a diploma). In total, about 12,000 inmates are enrolled in classroom academic programs at any given time.

Nontraditional Academic Programs. The CDCR also assists about 6,000 inmates through alternative academic education programs, such as independent study and distance learning. These education programs do not utilize as much direct teacher instruction as traditional classroom academic programs. In addition, although the department does not allocate funding for college programs, CDCR reports that about 4,000 inmates participate largely on their own in college coursework, typically through correspondence courses.

“Bridging” Education Program. In the past, education programs have not been available to inmates who were (1) housed in reception centers or (2) in regular prison beds but on a waiting list for admission to a program. The 2003–04 Budget Act included funding to begin implementation of an independent study program that continues today to bridge the gap between when an inmate arrives in prison and when he or she is placed in an education program or work assignment. Instructors provide inmates with workbooks focused on prerelease skills necessary for successful reintegration to communities as well as some academic material. Inmates work independently and are to meet with instructors weekly to assess their progress. The bridging program is staffed at a ratio of 54 students to each instructor position. Approximately 16,000 inmates are currently in bridging programs throughout the state prison system.

Vocational Education. The department offers various vocational training programs in most prisons, totaling almost 30 different specialized trades, including landscaping, automobile repair, and electrical work. In some vocational programs, inmates who complete the required curriculum earn professional certifications in those trades, such as air conditioning repair and welding. The department currently has almost 9,000 inmates enrolled in vocational education.

Prison Industries Authority (PIA). The PIA is a state–operated correctional industries organization that utilizes inmate labor to produce goods to sell to government and nonprofit entities. All of PIA’s operating costs are funded through the revenues produced from the sale of its products. While the Secretary of CDCR sits on PIA’s board of directors, PIA operates autonomously and is not a part of CDCR or its Division of Education and Vocation Programs. The PIA operates various service, manufacturing, and agricultural enterprises at about two–thirds of the state prisons and employs approximately 6,000 state inmates. While PIA primarily operates as a work program, some individual industries offer the opportunity for participating inmates to earn a vocational certification.

Other Education Programs. Most prisons also offer other programs through their education offices, including prerelease preparation, physical education, and a conflict resolution program called Conflict Anger Lifelong Management. In total, CDCR has just under 2,000 slots for these programs.

How Inmates Are Assigned To Education Programs

Upon entering the state prison system, each inmate is required to take the Test of Adult Basic Education, a test to determine his/her education level. Then, a classification committee made up of institution staff (typically including education staff) assigns each inmate to a work, academic, vocational, or other institution program. Education programs are voluntary, and if an inmate does not want to participate in an education program, the classification staff may assign him to a prison job, such as working in the prison kitchen or laundry.

Program and job assignments are on a first–come, first–served basis, meaning that inmates are generally assigned primarily based on the availability of programs at that institution. If an inmate is assigned to an education program at a prison with no education slots available, he is placed on a waiting list. The department reports that about 26,000 inmates are currently on prison waiting lists for education programs—about 15 percent of the total inmate population.

State Expenditures on Correctional Education

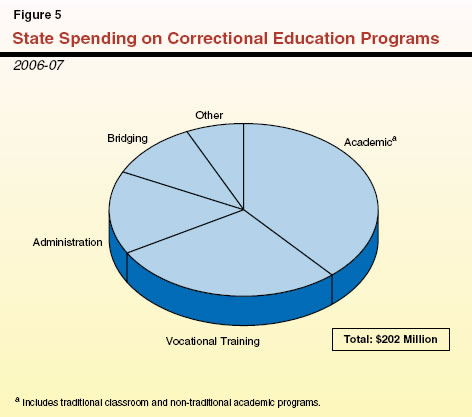

As shown in Figure 5, the state spent about $202 million for prison education programs in 2006–07, with all but $7 million (federal funds and reimbursements) coming from the state General Fund. This represents an increase of about 40 percent compared to spending in the prior year. Most of this funding—approximately 69 percent—is for academic programs, including traditional classroom programs, bridging, and nontraditional programs. The 2007–08 Budget Act includes about $220 million for these programs. However, at the time this analysis was completed, CDCR had not yet identified how it intended to allot those funds among each of its various education programs. The Governor’s budget for 2008–09 proposes about $225 million for inmate education programs.

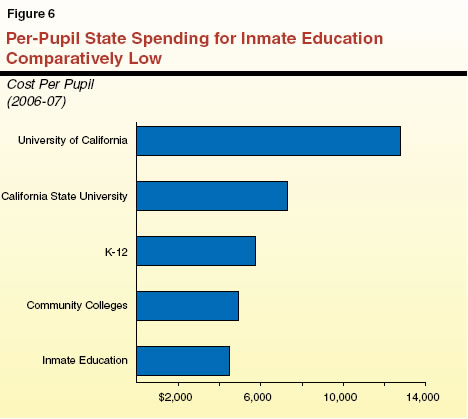

Figure 6 shows that average per inmate participant cost for education programs is approximately $4,200 (not including security costs), though it is worth noting that the average cost varies significantly by program. By comparison, the state spends about $5,800 per K–12 student in California, and between $4,900 and $12,800 on average per undergraduate student attending a community college, California State University, or University of California campus.

Remedial Work Required for CDCR Education Programs

Based upon our review of the available literature on inmate education programs; site visits to state prisons; and discussions with state and national correctional education researchers, teachers, and administrators, we have identified significant concerns with CDCR’s education programs. These are (1) insufficient capacity to enroll inmates in education programs, (2) low inmate attendance rates, (3) the lack of incentives for inmate participation and achievement, (4) poor case management, and (5) lack of program evaluation. We summarize these concerns in Figure 7 and discuss each of them in more detail below.

LAO Recommendations to Improve

State’s Correctional Education System |

|

✔ Structural changes to ensure program performance and CDCR accountability |

Fund programs based on actual attendance, not enrollment. |

Develop incentives for inmate participation and achievement. |

Fill teacher vacancies. |

Limit the negative impact of lockdowns on programs. |

Develop a case management system that assigns inmates to most appropriate programs based on risk and needs. |

Base education funding decisions on ongoing assessments of programs. |

✔ Address structural problems first, expand programs later |

✔ Future options to increase enrollment |

Create half-day programs. |

Partner with Prison Industries Authority to build program space. |

Other opportunities to expand education programs. |

Many Inmates Cannot Get an Education Assignment

Programs Reach Only Small Segment of Inmate Population. Our analysis indicates that the current set of CDCR education programs reach only a small segment of the inmate population who could benefit from them. The CDCR now enrolls about 54,000 inmates in education programs for a system with 173,000 inmates, and barely one–half of those—27,000 inmates—are in the core traditional academic and vocational training programs (including those operated by PIA) most likely to improve the educational attainment of inmates and thus their employability upon their release on parole to the community. The remaining programs—such as bridging, distance learning, and physical education—by their less intensive nature, are likely to not be as effective in helping inmates to progress in their education and employability.

The provision of only these 27,000 core education program slots means that these programs are available to about 16 percent of the total inmate population, despite estimates that three–quarters of inmates cannot read at a high–school level and evidence that most will be unemployed following their release from prison. In fact, three prisons—Deuel Vocational Institute (Tracy), North Kern State Prison (Delano), and Wasco State Prison (Wasco)—offer no traditional academic programs, a situation which appears to violate the state law requiring that all prisons provide educational programming designed to ensure that inmates can read at a ninth grade level. Seven state prisons offer no vocational education programs.

Of particular importance, CDCR is not providing these programs to inmates with the lowest level of educational achievement. The CDCR’s most recent estimate is that about 110,000 inmates in the prison population read below the ninth grade level. However, pre–high school level classes are available to only about 8,100—or 7 percent—of these inmates.

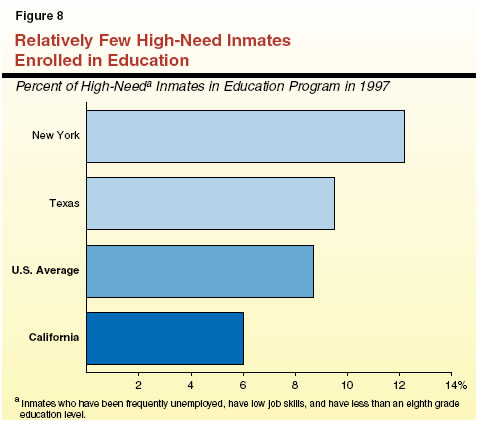

Moreover, research has shown that California compares poorly with the rest of the nation in providing education and vocational training to inmates who would most benefit from them—including inmates who have been unemployed frequently, have low job skills, and have less than an eighth grade education level. As shown in Figure 8, only about 6 percent of these “high– need” inmates received education or vocational programming in 1997, a level significantly below that of the rest of the nation and other large states. While this data is a decade old, it does not appear that California has made significant strides in providing core education programs. In fact, the combined capacity of traditional education, vocational, and PIA programs has actually declined by 29 percent since 1998–99, dropping from 37,000 slots that year to 27,000 slots in 2006–07.

Unfortunately, these findings are symptomatic of the inability of CDCR to provide inmate programs in general. A recent report by a group of national experts brought in to review CDCR rehabilitation programs (generally referred to as the “Expert Panel”) found that about one–half of all California inmates are released from prison without participating in any rehabilitation or work program during their most recent prison term. This lack of sufficient programming capacity in education as well as other areas of rehabilitation is probably a significant contributor to California’s high recidivism rate compared to the rest of the nation. Moreover, there is evidence that the limited program slots available are not targeted to those offenders who are likely to be released from prison. For example, the PIA reports that almost one–third of its inmate participants are lifers.

Reasons for Low Enrollment Levels. Education enrollment capacity is low primarily because of a couple of factors. First, the state corrections department has not historically considered education and rehabilitation programs a primary mission. As such, expanding the provision of education programs or seeking funds to keep pace with the growing population was not an organizational priority compared to other correctional missions. As discussed above, this attitude has begun to change in more recent years, as reflected, for example in the department’s reorganization and mission change.

Second, since about 2001, the state has faced significant fiscal problems that have made it difficult to increase its investment in inmate education programs. (Nevertheless, in more recent years, the Legislature and administration have provided more funding for inmate rehabilitation programs in general, and education programs in particular. For example, the 2007–08 budget includes about $14 million in additional funding for higher teacher salaries and more vocational programs.)

Third, the physical space needed to hold academic and vocational classes is limited in many prisons. Most prisons were originally designed to provide education or rehabilitation programming to only a fraction of all inmates housed in those facilities. Moreover, California prisons are currently housing many more inmates than originally intended. Importantly, Chapter 7 (discussed in more detail above) could help to address some of this problem of a lack of physical space for programs to the extent that it is successful at relieving overcrowding at existing facilities, as well as results in the construction of additional programming space at existing prisons and reentry facilities. However, it is currently unclear how much additional programming capacity will be created by Chapter 7 construction projects, largely because the department’s construction plans have undergone significant changes since the enactment of Chapter 7.

Enrolled Inmates Frequently Don’t Get to Class

As discussed above, the department has about 21,000 inmates enrolled in classroom academic and vocational programs. However, this figure overstates the number of inmates who are actually attending classes on a daily basis. In fact, CDCR reports that during 2006–07 on average 43 percent of all enrolled inmates were in class each day. The failure of inmates to attend classes on a regular and consistent basis is an important operational problem because it significantly reduces the effectiveness of these programs. We would note that the attendance levels in 2006–07 were a slight improvement compared to 2005–06, when an average of only 40 percent of enrolled inmates were in class each day.

There are three significant factors that contribute to attendance rates lower than program capacity. These are (1) lockdowns, (2) staffing vacancies, and (3) the state’s process for allocating funding for education programs. We discuss each of these in more detail below, as well as discuss the consequences of these low participation rates.

Lockdowns. During lockdowns, prison administrators confine large groups of inmates in their cells, typically in response to inmate violence or the threat of violence. Lockdowns keep inmates—including many not involved in the incident that triggered the lockdown—from participating in programs such as education classes. Lockdowns are often necessary to maintain the safety of a prison. However, as we discussed in our 2005–06 Analysis of the Budget Bill (please see page D–34), there is evidence that the department has historically overused this strategy by not targeting the use of lockdowns to the most serious situations. As shown in Figure 9, there were almost 600 lockdowns in state prisons between April and December 2006, with 100 of those lasting at least one month, and 37 lasting at least three months. Department records show that inmates are absent from education classes about 27 percent of the time due to lockdowns.

Figure 9

Number of Lockdowns in CDCR Prisons |

2006a |

Facility Type

(Number of Institutions) |

Number of Lockdownsb |

Lockdowns Lasting at Least |

30 Days |

60 Days |

90 Days |

Level II and III (9) |

193 |

18 |

6 |

4 |

Level III and IV (8) |

115 |

14 |

9 |

5 |

High Security (7) |

171 |

45 |

19 |

15 |

Reception Center (6) |

72 |

23 |

17 |

13 |

Female (3) |

9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Totals (33) |

560 |

100 |

51 |

37 |

|

a Includes lockdowns in effect during the period April through December 2006. |

b "Lockdowns" include all lockdown incidents listed in CDCR Program Status Reports. |

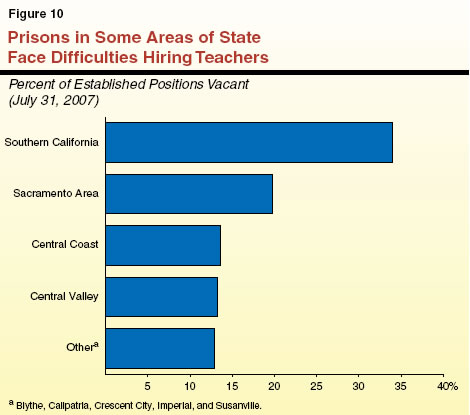

Staffing Vacancies. Inmates also do not attend classes when teaching positions are vacant. According to the State Controller’s Office, about 17 percent of the department’s 1,500 teacher positions were vacant as of July 31, 2007. Figure 10 shows the percentage of teacher vacancies at prisons in different regions of the state. As shown in the figure, prisons in Southern California and near Sacramento have higher vacancy rates on average than other parts of the state despite their proximity to a larger pool of potential hires. The data also show significant variation in the vacancy rates among the prisons within each region. This suggests that vacancy problems at individual prisons are only partially due to prison location, and in fact may also be due to other factors specific to individual institutions, such as work environment, budget and management issues, and the frequency of lockdowns that reduce the need to fill teacher positions.

In addition to permanent staff vacancies, teaching positions are often vacant when instructors take short–term leaves, such as for sick leave, vacation, and training. The CDCR reports that in 2004–05, teachers took an average of 23 days of leave. The department reports that inmates miss education classes 22 percent of the time due to short–term absences of instructors.

Yet, despite staffing leaves, the department historically has not utilized substitute teachers or hired teachers with emergency permits (formerly called emergency credentials) to fill vacancies during staff absences. It is worth noting that in the current year the department has converted 46 of its existing teacher positions to be substitutes and has begun hiring teachers with emergency permits for short periods.

Current Funding Structure. The process by which funding is budgeted for CDCR and allocated to education programs at individual prisons contributes to the problem of inmates not getting to classes. This is because funding levels are not based on actual class attendance, but rather on expected attendance by inmates. Under current practice, CDCR receives education funds based on the number and type of programs it plans on providing in the budget year, generally based on prior–year levels. The department then distributes these funds to each institution based on the number and types of programs expected to be operated at each of those prisons.

However, actual attendance is often below the enrollment level expected because of the frequent lockdowns and staffing vacancies described above. Thus, the department and individual prisons are budgeted to provide more educational services than they actually provide. There is no requirement that CDCR or its individual prisons return education funding to the General Fund when this occurs. This approach reduces the incentive for prison administrators to ensure that education programs are fully staffed and operating and that inmates are actually in class. The department reports that in recent years unspent funds have been used for other purchases, such as for textbooks and computers.

In contrast, funding for public schools primarily reflects average daily attendance (ADA) rates which measure how often students are actually in class rather than the number of students enrolled in a school. The ADA system provides a strong incentive for schools to do as much as they can to ensure that students are in the classroom.

Limited Incentives for Inmate Participation and Rehabilitation

Given that participation in education programs is voluntary, it is important that inmates have appropriate incentives to participate in rehabilitation programs in order to maximize the public safety and fiscal benefits. Our examination found that CDCR provides few incentives for inmates to participate in educational and vocational programs, as compared to the incentives for inmates to participate in other types of programs. In fact, the Expert Panel brought in to evaluate CDCR rehabilitation programs cited a lack of appropriate incentives as one of the most significant shortcomings of CDCR rehabilitation programs.

Few Incentives to Participate in Education Programs. Our analysis indicates that there is currently a disincentive for inmates to participate in education as compared to other prison programs. Most inmates who enroll in education programs earn work release credits equal to one day off from their sentence for each day in the program (commonly referred to as “day for day”). While these credits do provide some incentive to be in an education program, other programs provide greater immediate benefits, from an inmate’s perspective, in terms of a greater sentence reduction or pay.

For example, inmates in conservation camps earn two days off of their prison sentence for each day in the program. Inmates assigned to a job in prison, such as in the kitchen or laundry, receive the same day–for–day credits as for an education program, but additionally earn a small income. Moreover, inmates assigned to non–traditional academic programs such as distance learning, do not earn any work release credits for their participation unless they are also enrolled in another credit–earning program at the same time.

Poor Case Management of Offenders

Lack of Case Management... Case management refers to the idea of placing the “right” inmates in the “right” programs to maximize the effectiveness of those programs. Effective case management, therefore, ultimately requires (1) identifying the programmatic needs of inmates, (2) targeting programs to the most appropriate offenders, and (3) tracking the progress of individual cases on an ongoing basis. Currently, our analysis indicates, CDCR does not carry out any of these tasks on a statewide or systematic basis.

Typically, effective case management is begun by assessing the risks and needs of inmates using a formal assessment tool. This assessment can tell prison administrators what program(s) or treatment(s) will best serve an individual inmate. For example, if it is determined that an individual inmate’s criminal history is most closely related to addiction and unemployment, then the most appropriate programs for that offender might be substance abuse treatment and vocational training. Currently, CDCR does not utilize formal needs assessments of all inmates entering state prison, except for pilot assessment programs at four prisons. The administration’s 2008–09 budget proposes to expand the use of these assessments to all reception centers in 2008–09.

The CDCR also does not target its programs to the most appropriate offenders. Instead, CDCR generally assigns inmates to programs on a first–come, first–served basis. Such an approach likely results in some inmates who would greatly benefit from participation in a particular program not being assigned to the most appropriate programs, while those limited program slots may instead be filled with other, less appropriate offenders.

The challenge of putting the right inmates in the right programs is exacerbated in CDCR prisons by the fact that the department does not currently operate a centralized case management database for inmate education programs. Instead, each prison operates its own education data tracking system that includes some common information, such as attendance and number of inmates passing GED tests. These data systems are neither centralized at headquarters nor comprehensive in the information collected. Nor are these fragmented systems linked to other inmate or parole data systems with potentially valuable information—such as age, mental illness, employment history, or time remaining on the sentence—which would assist correctional staff in making case management decisions.

Consequently, the absence of centralized data systems for education programs makes it difficult for the department to track the education level, placement history, and program advancement of individual inmates. Without such a system, staff cannot easily obtain current information about inmates to determine the most appropriate program placement, including whether the inmate would be best served in a certain level of an academic program, a vocational program, or in a prison job. The fragmented and incomplete information technology (IT) systems are particularly problematic in a prison education setting where inmates frequently move between institutions, as well as from prison to parole and back again to prison.

…Reduces Effectiveness of Programs. The lack of systematic and effective case management at CDCR means there is a high probability that many of the “wrong” inmates are ending up in the “wrong” programs. If inmates are not participating in the best treatment programs for them, these programs, in turn, are likely to be less effective at reducing recidivism than they could be if targeted to the right offenders.

Lack of Program Evaluation Limits Effectiveness

Department Lacks IT Systems Necessary to Evaluate Education Programs. As discussed above, the department’s existing IT systems are insufficient to support case management of individual inmates in CDCR programs. There is another significant IT–related problem in that CDCR’s IT systems are also not designed to allow tracking of performance by the education system as a whole or for specific programs. As a result, the department is unable to easily identify program outcomes such as grade level advancements, rates of program completion (for example, the number of inmates obtaining their GED or vocational certification), and impacts of programs on parole outcomes, including employment and recidivism. For example, although state law requires the department to get inmates to read at a ninth grade level upon release, the department cannot say how often it is complying with this requirement.

Current IT Project Will Provide Limited Benefit to Programs. The CDCR is in the process of developing a new centralized case records database system to be used throughout its institutions and headquarters called the Statewide Offender Management System (SOMS). The SOMS, currently in the design phase and scheduled to be implemented in 2013, is expected to contain information on inmates’ criminal history, classification and housing, medical and mental health records, and parole revocations. While this system will be central to managing the inmate population in many respects, it will, as it is now planned, contain only limited information regarding an inmate’s participation in education programs.

Vocational Programs: An Example of a Program That Could Benefit From Program Evaluation. Research shows that the effectiveness of vocational education programs may largely depend on the specific vocational certification an inmate earns and whether there is an active job market for those skills in the community to which he is being released. Texas inmates who earned machinist or welder certificates, for example, were more than three times more likely to be employed in their field than inmates earning a certificate in automotive repair.

However, CDCR does not currently have the IT capability to track and measure employment or recidivism outcomes of parolees to determine which vocational education programs are most effective. One would expect that positive outcomes for inmates would be associated with participation in those vocational programs that are in growing industries that need new workers, as well as provide a wage that is likely to be an incentive for the offender to work rather than return to criminal activities. As shown in Figure 11, not all of CDCR’s current vocational programs are in industries with projected annual job growth of over 2,000 jobs and where the average wage is more than $15 per hour. Also, several of CDCR’s vocational programs do not provide participating inmates with an opportunity to earn a professional certification which would better enable them to gain employment after release from prison. While not definitive, these findings suggest that some of these vocational programs may not be as effective as others at leading to employment after release, as well as reducing recidivism. An IT system that allowed CDCR to evaluate the effectiveness of specific vocational programs would provide valuable information to allow the state to make strategic decisions about which of these programs to continue, discontinue, or expand in order to maximize the benefits achieved from the state’s investment in prison vocational programs.

Figure 11

Inmate Vocational Programs

Not Always Targeting Growth Industries |

|

|

Criteria |

CDCR Programs |

Enrollment

(2007) |

Projected Annual Job Growtha >2,000 |

Hourly Wagea >$15 |

Inmates

Earn

Professional

Certification |

Auto body |

446 |

|

X |

X |

Auto mechanics |

497 |

X |

X |

X |

Building maintenance |

350 |

X |

X |

X |

Carpentry |

190 |

X |

X |

X |

Cosmetology |

53 |

|

|

X |

Dry cleaning |

332 |

|

|

|

Electrical |

202 |

X |

X |

|

Electronics |

744 |

|

X |

X |

Graphic arts |

548 |

|

X |

|

Household repair |

27 |

X |

X |

|

Installer/taper |

27 |

|

X |

|

Janitorial |

611 |

X |

|

|

Landscape gardening |

581 |

|

|

X |

Machine shop |

157 |

X |

X |

X |

Machine shop—automotive |

54 |

X |

X |

|

Masonry |

243 |

|

X |

X |

Mill and cabinet work |

385 |

|

|

X |

Office machines |

27 |

|

X |

|

Office services and technologies |

1,697 |

X |

|

X |

Painting |

193 |

X |

X |

X |

Plumbing |

176 |

X |

X |

X |

Refrigeration |

294 |

|

X |

|

Roofer |

27 |

|

X |

|

Sheet metal |

50 |

|

X |

X |

Small engine repair |

360 |

|

|

X |

Welding |

534 |

|

|

X |

Total |

8,805 |

|

|

|

|

a Source: Employment Development Department occupational employment projections (2004-2014). |

Recommendations to Improve Performance, Outcomes, and Accountability

Based on our review of the research, discussions with CDCR, discussions with national experts, and site visits to existing institutions, we find there are a number of steps the state could take to address the shortcomings of current CDCR education programs. Specifically, we recommend a series of structural reforms to better ensure that the state’s current investment in correctional education is better managed and provides a significant return through reduced reoffending in the community and fewer returns of offenders to prison. Importantly, given the state’s fiscal condition, each of these recommendations can be implemented with minimal new costs or utilizing existing resources. Once these steps are underway, the Legislature may wish to consider various additional steps to expand education programs to more state inmates, including one key recommendation that could be implemented primarily utilizing existing departmental resources. Our recommendations are summarized in Figure 12 and described in more detail below.

Figure 12

LAO Recommendations to Improve

State’s Correctional Education System |

|

✔ Structural changes to ensure program performance and CDCR accountability |

Fund programs based on actual attendance, not enrollment. |

Develop incentives for inmate participation and achievement. |

Fill teacher vacancies. |

Limit the negative impact of lockdowns on programs. |

Develop a case management system that assigns inmates to most appropriate programs based on risk and needs. |

Base education funding decisions on ongoing assessments of programs. |

✔ Address structural problems first, expand programs later |

✔ Future options to increase enrollment |

Create half-day programs. |

Partner with Prison Industries Authority to build program space. |

Other opportunities to expand education programs. |

Structural Changes to Ensure Program Performance and CDCR Accountability

As described above, there is significant research to demonstrate that correctional education programs can significantly reduce the recidivism rate of inmate participants. However, several structural problems in CDCR’s programs—problems that are systemic and statewide—result in California not achieving the full potential benefit of its more than $200 million invested annually in prison education programs. Therefore, we recommend several steps the state should take to ensure better return on its current investment in correctional education programs.

Fund Programs Based on Actual Attendance, Not Enrollment

Establish Education Funding Formula…We recommend restructuring the way that inmate education programs are funded in CDCR. Instead of providing a base level of funding that is unaffected by actual attendance, as is currently the case, we recommend instituting a funding formula for education programs that is directly tied to actual inmate attendance, similar to ADA formulas used in public K–12 schools and adult education programs. Such a funding mechanism would need to factor in the different staffing levels, as well as educational supplies and equipment costs necessary for different types of academic and vocational programs. This could involve, for example, establishing different funding formulas for high school education than for bridging or vocational programs.

Under our proposal, the amount of total funding for education would be appropriated in the annual state budget, just as it is now. However, this funding would be directly linked to projected attendance for academic and vocational programs. If actual attendance in academic programs fell short of these projections, a proportionate share of the education funding would automatically revert to the General Fund. Because some number of student absences is reasonable and unavoidable, we recommend that 20 percent of the funding not be subject to the ADA formula. This would protect the department from losing education funding for student absences that occur for reasons out of its control. The department may need to provide the Legislature with an estimate of how often such absences occur. We recommend that the Legislature adopt the following statutory language to implement this change:

Proposed Language— Education Funding Formula

The budget for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation includes funding for the operation of various academic and vocational education programs in state prisons. The administration’s budget request for this funding shall identify the expected average daily attendance level for each education program. If the actual average daily attendance for any of these programs falls below the level identified in the budget request, a share of funding that is proportionate to the difference between the expected and actual attendance levels shall revert to the General Fund. Because some level of student absences is reasonable and unavoidable, the budget request for this funding may include a base share of 20 percent that is not subject to reductions due to actual attendance falling below the expected level. This section shall become effective starting in the 2009–10 fiscal year.

...To Increase Actual Attendance Rates…Establishing an ADA formula would provide an incentive to the department to ensure that inmates go to programs regularly, knowing that if inmate attendance is low, the department will lose funding. This could also prompt CDCR to become more strategic and encourage it to resolve teacher vacancy and lockdown problems that lead to low attendance. For example, permanent teaching positions could be converted to substitute positions at prisons with historically high vacancy rates to ensure that programs continue to operate even when vacancies occur.

...And Improve Fiscal Accountability. The implementation of an ADA funding formula would improve accountability by more accurately aligning budget authority for education programs with actual expenditures on in–classroom instruction. In other words, the Legislature would know that CDCR funds spent on inmate education were actually used to educate inmates.

Develop Incentives for Inmate Participation and Achievement

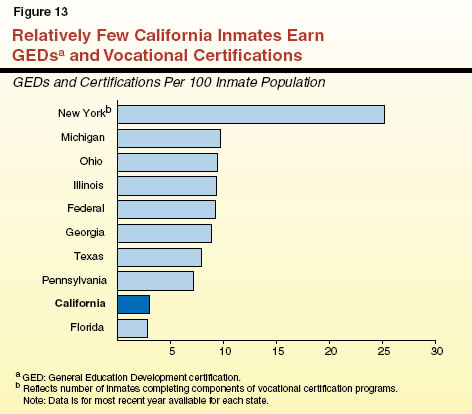

Various Incentives Can Be Used in Correctional Settings. While California no longer uses indeterminate sentencing for most inmates as a motivator for inmate rehabilitation, there are a number of other measures CDCR could take to provide greater incentives for inmates to participate in rehabilitation programs, including education programs. Corrections administrators and experts suggest that several aspects of prison life that inmates care about can be used to encourage certain behavior, including participation and advancement in education programs. These aspects include inmate pay and access to canteen, food, recreation, visiting, and housing. Providing an incentive for inmates to not just enroll, but also to advance, in programs is particularly important. That is because research demonstrates that achievement of certain education levels, such as basic literacy and GEDs, are even more highly correlated with reduced recidivism than just participation in education programs. As Figure 13 shows, among the nation’s largest prison systems, California has among the lowest percentage of the inmate population earning a GED or vocational certification.

To accomplish this, inmate pay for prison jobs could be linked to their level of educational attainment. Under such an approach, an inmate who has advanced to high school level classes might earn more in his prison job than when he was in middle school level classes. The top paying prison jobs, provided by PIA, could be reserved for inmates with a high school diploma or equivalent. This approach would not only provide an incentive for inmates to enroll in school, but importantly to successfully advance in their studies. The CDCR could similarly provide benefits such as extra visiting or recreation time, choices of better housing or work options, or special meals for those inmates who advance to higher academic levels. Importantly, the department could provide such incentives at little or no additional cost to the state. Another approach that some states use— Pennsylvania, for example—is to pay inmates in education program, similar to how inmates are already paid for prison jobs such as working in a kitchen or laundry.

Even within the framework of California’s determinate sentencing laws, it is possible to enact statutory changes to use an earlier release from prison as an incentive for education program participation and success. Most inmates who work or participate in education programs already earn day–for–day release credits. However, inmates who work in CDCR’s conservation camps can earn additional work release credits for their services to the state. One option the Legislature may wish to consider is enacting a law providing “education release credits” for inmates who achieve certain levels of educational attainment while in prison. For example, an inmate who earned a vocational certification or GED while in prison could receive additional credits towards his/her release date. As with all early release credits, they could be revoked if an inmate had serious disciplinary infractions while in prison. Also, these bonus credits could be capped to ensure that no inmate earns an inordinate amount of time off of his/her sentence. An additional benefit of this recommendation is that it would result in savings to the state as these inmates served shorter terms in prison because of their successful participation in education programs. These savings could reach tens of millions of dollars annually, depending upon the amount of additional early release time that could be earned for various types of achievement, as well as the number of inmates who achieved specified educational goals each year. In the longer term, these savings could be used to offset other costs to expand and improve prison education programs. Figure 14 lists several examples of incentives that could be used to encourage inmate participation in education programs.

Figure 14

Options to Provide Incentives for Inmates to

Participate and Advance in Education Programs |

|

✔ Provide a higher work release credit rate for inmates participating in education programs and/or a bonus amount of credit that is earned for successful completion of an education program, such as advancement to high school level courses or earning a vocational certification. |

✔ Link the pay scale for inmate jobs to educational attainment. For example, could require attainment of a General Education Development (GED) certification before an inmate can be assigned to highest paying prison jobs, such as Prison Industries Authority. |

✔ Pay inmates who participate in education programs. Pay a higher rate for more advanced education levels. |

✔ Give inmates in education program better housing assignments, such as housing in newer facilities, more out-of-cell time, or other privileges. Give the best assignments to those inmates who have earned their GED or vocational certification. |

✔ Allow inmates in education programs to have more frequent, higher quality, or priority access to visiting, canteen, meals, and recreation. |

Should Inmates Be Provided Additional Incentives? Some may wonder why it is important to provide incentives, such as a reduction in the time served in prison, for inmates to participate in education programs. Research finds that such incentives are important because they can improve education program outcomes, improve institution security, and ultimately improve public safety. Many correctional experts have concluded that motivation plays an important role in determining the level of inmate participation in prison programs, and the extent to which they will advance in those programs. Therefore, well–designed incentives can encourage inmates to not only participate but also focus on educational success and advancement. The development of educational skills could assist inmates to transition successfully to their communities after their release from prison, reduce recidivism, and hence, improve public safety.

Fill Teacher Vacancies

Utilize Substitute Teachers. As described above, vacancies in teaching positions and frequent sick leave, vacation, and other types of leave limit the opportunity of inmates to attend education programs. The 2007–08 Budget Act does include additional resources to provide pay increases for teachers which could assist recruitment and retention efforts. Moreover, CDCR reports that it has begun converting some regular teacher positions to substitutes to allow them greater flexibility to cover teacher vacancies and leaves. We think this is a reasonable approach given the frequency with which education programs are idle and because this approach allows the department to address these problems utilizing existing resources. The trade–off, however, is that the conversion of teacher positions to substitutes reduces the potential enrollment level of the education system by removing regular instructors.

In the longer term, should the state’s fiscal condition improve, this problem of few substitute teachers could be reduced if the department were permanently funded for substitute teachers. We estimate that it would cost about $11 million annually to provide sufficient additional funding to hire additional substitute instructors to fill in when sick leave and vacation are taken by regular instructors. We estimate that additional funding of about $7 million would be sufficient to hire enough substitute teachers to fill in for vacancies in teacher positions (assuming a standard 5 percent vacancy rate).

However, it makes little sense for the Legislature to add funding for such purposes to CDCR’s budget until after the department demonstrates that it is able to significantly reduce its current high–vacancy rates for regular teachers.

Allow Teachers With Emergency Permits. Unlike public schools, CDCR has not historically been allowed to hire teachers with emergency permits to fill vacancies. Teachers with emergency permits may only be hired as short–term substitutes, despite the hiring difficulties experienced by the department in many locations in the statewide prison system. We recommend that the Legislature direct the State Personnel Board—the state agency responsible for setting classification requirements for positions in state service—to amend the classification requirements for teachers in correctional facilities so that the department could hire teachers with emergency permits in those locations where there is difficulty hiring and retaining fully credentialed instructors. We also recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to provide regular reports on its progress in utilizing teachers with emergency permits, as well as substitutes, consistent with the following supplemental report language:

Proposed Language—Substitute Teachers and Emergency Permits

The prison education programs operated by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) have historically experienced high vacancy rates among academic teacher and vocational instructor positions. It is a state priority that CDCR implement strategies to successfully reduce these vacancy rates so as to ensure that inmates are regularly engaged in meaningful rehabilitation programs that will reduce the likelihood that they reoffend after release to the community. No later than January 10, 2009 and annually thereafter, the CDCR shall provide a report to the fiscal committees of both houses identifying what steps the department has taken to reduce or otherwise address the problem of teacher and instructor vacancies, including but not limited to the use of substitute teachers and teachers with emergency permits. This report shall also include information on the progress made in reducing these vacancy rates at each institution. This report may be provided as part of the supplemental report required under Penal Code section 2063(c).

In the event that even allowance of teachers with emergency permits does not effectively reduce vacancy rates, it also may be worth considering whether credentials and permits should be required for prison teachers. Some research into public school systems finds little evidence that teaching credentials result in better outcomes for students generally. Given the state’s difficulty hiring teachers in prison, it might make sense to change the minimum requirement to a bachelor’s degree for prison teachers. This approach may make particular sense given that CDCR has recently implemented a standard curriculum for its education programs statewide. The department would still be responsible for providing necessary training to new teachers.

Reduce the Negative Impact of Lockdowns on Programs

We recommend that the department modify its current policies related to lockdowns. In particular, the Legislature should direct the department to reevaluate its current policies that result in inmates being barred from attending education and other rehabilitation programs even when they were not involved in the incident that caused the lockdown. For example, the department could explore establishing a policy of allowing inmates in these programs out of lockdown sooner than other inmates to attend their programs. One possible way of accomplishing this could be to generally have prisons house all inmates in education programs in the same housing units or prison yards rather than spread them among various housing units across the prison, as is currently the case. If a serious incident occurs in a different housing unit, it might make it easier for prison administrators to release the programming inmates to their programs, knowing that they were not directly involved in the incident. This type of strategy would demonstrate the importance the department places on rehabilitation and provide a disincentive for inmates enrolled in education programs to participate in fights that lead to lockdowns.

Given the continuing major impact of lockdowns on education and other programs, the department should report at budget hearings on the efforts it has made to reduce the use of lockdowns that interfere with inmate programming.

Develop an Inmate Case Management System

We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to take steps to improve its case management of inmates in the education system (as well as other programs designed to reduce recidivism). The CDCR should develop policies and protocols that more consistently ensure that the right inmates are assigned to the right programs and that the progress of inmates is tracked consistently while they are in these programs.

Improving Program Placement Decisions. As described earlier, it appears that CDCR’s current procedures generally place inmates in programs on a first–come, first–served basis rather than on an assessment that determines who would benefit most from participation in a particular program. Placement decisions should instead be made based on such factors as an individual inmate’s risk to reoffend, relative need for different programs and treatment, and motivation to participate and change behavior. For example, research generally finds that inmates with high risk factors should be steered toward more intensive and multifaceted treatment services—such as those that address multiple areas of risk, including criminal thinking, substance abuse, mental health, and literacy—because they are the ones who are likely to benefit the most from the services. Lower–risk inmates can also benefit from programs, but generally require less intensive treatment that is more focused on their specific areas of need, such as education. See the text box below for a more detailed discussion about some of the factors that are critical to the effective case management of criminal offenders and operation of correctional programs.

Currently, CDCR is pilot testing a risk–needs assessment called the Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS) at some prison reception centers with the intention of using this tool to help make program placement decisions. We think this is potentially a good approach. However, it is not clear at this point what criteria CDCR intends to use to make those placement decisions and how these criteria will be formalized in department policies. Specifically, it is unclear how CDCR will use the information provided by COMPAS assessments to improve case management decisions. For example, will inmates identified by COMPAS as high risk be given first priority to programs? Will inmates with a high need for education services be given higher priority for transfer to institutions with those programs available? What priority will lifers receive for education services compared to determinately sentenced inmates? The Legislature should direct CDCR to address these types of questions at budget hearings, particularly since the department plans to expand the use of COMPAS in 2008–09.

Criteria for Effective Correctional Rehabilitation Programs

Research shows that successful correctional rehabilitation programs—whether they are education, substance abuse, mental health, or other types of programs—and the case management systems that place inmates into those programs have several key components. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation should create a process for evaluating whether its programs—including, but not limited to, education programs—adhere to these criteria, which we describe below.

- Program Model. Programs should be modeled on widely accepted principles of effective treatment and, ideally, research demonstrating that the approach is effective at achieving specific goals.

- Risk Principle. Treatment should be targeted towards inmates identified as most likely to reoffend based on their risk factors—for example, those inmates who display high levels of antisocial or criminal thinking, low literacy rates, or severe mental illness. Focusing treatment resources on these inmates will achieve greater net benefits compared to inmates who are low–risk to reoffend even in the absence of treatment programs, thereby generating greater “bang for the buck.”

- Needs Principle. Programs should be specifically designed to address those offender needs which are directly linked to their criminal behavior, such as antisocial attitudes, substance abuse, and illiteracy.

- Responsivity Principle. Treatment approaches should be matched to the characteristics of the target population. For example, research has shown that male and female inmates respond differently to some types of treatment programs. Important characteristics to consider include gender, motivation to change, and learning styles.

- Dosage. The amount of intervention should be sufficient to achieve the intended goals of the program, considering the duration, frequency, and intensity of treatment services. Generally, higher–dosage programs are more effective than low–dosage interventions.

- Trained Staff. Staff should have proper qualifications, experience, and training to provide the treatment services effectively.

- Positive Reinforcement. Behavioral research has found that the use of positive reinforcements—such as increased privileges and verbal encouragement—can significantly increase the effectiveness of treatment, particularly when provided at a higher ratio than negative reinforcements or punishments.

- Post–Treatment Services. Some services should continue after completion of intervention to reduce the likelihood of relapse and reoffending. Continuing services is particularly important for inmates transitioning to parole.

- Evaluation. Program outcomes and staff performance should be regularly evaluated to ensure the effectiveness of the intervention and identify areas for improvement.

|

Potential Benefits of an Education Case Management System. A formal risk–needs assessment tool such as COMPAS would provide important information that should be incorporated into a broader case management IT system. At the time that this report was prepared, CDCR had proposed to create a case management database for education programs called Education for Inmates/Ward Reporting and Statewide Tracking (EdFIRST). The proposal is estimated to result in about $10 million in one–time implementation costs and $4 million in costs annually thereafter to maintain the system. The administration’s 2008–09 budget proposes to spend $1 million in the budget year to begin implementing EdFIRST. The implementation costs for EdFIRST are proposed to be funded from a $50 million appropriation provided in Chapter 7 for rehabilitation programs. Subsequent legislation requires that priority for spending this appropriation be given to specific purposes such as risk–needs assessments and expanding education programs. While the statute does not specifically give priority to a case management database, the proposed use of these funds would appear to be consistent with the measure’s requirements.

An education case management IT system—such as proposed by CDCR—would help teachers and correctional counselors to make appropriate program placements and to track participation and advancement of individual inmates in their educational programs, likely leading to better outcomes for individual participants. However, we will analyze the administration’s IT proposal in more detail as part of our review of the 2008–09 budget plan.

Base Education Funding Decisions on Ongoing Assessments of Programs

The education IT system discussed above should do more than help guide decision making pertaining to individual inmates. It should also be part of a system to assess the effectiveness of education programs and determine, over time, how the state could get the greatest results for its investment in these programs. For example, an IT system that tracked the outcomes of individual inmates could aggregate that data department–wide in order to assess overall progress on increasing attendance rates, test scores, GED and vocational certification completion rates, as well as on decreasing inmate recidivism. In addition, the department could use the data collected to compare outcomes at individual prisons and programs to identify unsuccessful programs which may need to be improved or, in some cases, eliminated entirely. Over time, such information would provide the Legislature and the department with valuable information about how to best target limited state resources for inmate education to generate the greatest benefit. We believe these program evaluations could largely be accomplished within existing resources because the Legislature has recently provided additional funding for CDCR to bolster its internal research office, primarily to analyze the effectiveness of department programs.

Address Structural Problems First, Expand Program Capacity Later

As described above, CDCR must overcome significant structural barriers to ensure that the more than $200 million a year now being spent on inmate education is used in the most effective way possible. These findings imply that any additional investment made at this time to expand the capacity of education programs could well be a poor expenditure of funds because there would be little assurance that the department was putting these monies into effective programs. Therefore, we recommend that the steps to address these structural problems be adopted before the state significantly expands the capacity of the prison education system.

Future Options to Expand Education Enrollment at Lower Cost

Once CDCR has improved its education programs, the Legislature may wish to look at ways to expand such programs to a larger share of the state inmate population. The traditional approach would be to add teachers and vocational instructors, as well as related equipment, supplies, and program space, much the same way such programs have been implemented in the past. However, the Legislature should consider several other options to increase the number of inmates participating in education programs at a significantly lower cost than would otherwise be the case. In particular, we would recommend implementation of half–day programs.

Create Half–Day Programs

We recommend that among the first changes the Legislature consider after CDCR addresses its structural problems is to restructure CDCR’s classroom academic education and other programs from full–day to half–day classes. Currently, inmates attending education programs go to class six hours a day, five days a week. We propose, instead, establishing two three–hour sessions each day, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. Inmates would attend either the morning or the afternoon session. Generally, during the morning or afternoon period in which an inmate is not in an educational program, he/she would go to work at a prison job, participate in other prison rehabilitation programs, or study. In some cases, it may be useful to maintain vocational programs that provide official certification as full–day programs to allow inmates to complete the training programs in the requisite period of time.

Moving to half–day programs would increase enrollment capacity at little or no cost to the state, improve program effectiveness, and create greater incentives for inmate participation, as discussed below.

Increased Education Program Capacity. Instituting half–day programs would immediately increase the capacity of the classroom academic and some vocational programs, thereby allowing at least 12,000 more inmates to participate in an educational program. This capacity expansion would allow CDCR to come closer to meeting current statutory requirements to provide education services to low–performing inmates. Moreover, the increase in program capacity would occur without requiring significant additional resources. The department could provide the additional program capacity with existing program staff and space. There may be some additional resources required to provide school supplies, such as textbooks, to more inmates. We estimate this annual additional cost to be a couple million dollars at most.

Increased Program Effectiveness. In addition, our analysis indicates that a shift to half–day classes could provide more effective programs, at least for some inmates. Half–day education programs are commonly used in other state prisons, and several correctional education administrators and researchers have advised us that certain inmates—particularly those with little previous success in school—may be more successful in a half–day classroom format.

In addition, a shift to half–day programs would create greater opportunities for inmates to receive other program and treatment services during the day necessary to further their rehabilitation. For high–risk offenders who have multiple risk factors for reoffending, a switch to half–day programs would allow them to participate in multiple programs, such as education programs during one–half of the day and some other type of program—such as substance abuse treatment—during the other half of the day.

Program effectiveness could also be improved because our proposal provides more flexibility to correctional instructors to tailor their efforts to the needs of the students. For example, a current full–day class with a mix of students with ninth through twelfth grade skills could be divided into two, half–day classes. One class could have students with ninth and tenth graders, and the other could have eleventh and twelfth graders, thereby allowing teachers to narrow and target the scope of instruction in each class to the different needs of the students.

Moreover, operating two sessions each day would improve program effectiveness by allowing the department to convert bridging programs to traditional classroom programs in prisons where space is available. While neither CDCR’s classroom academic nor its bridging programs have been evaluated for effectiveness, the more intensive classroom programs are likely to be more effective for two reasons. First, CDCR classroom education programs are accredited while the bridging program is not. Second, half–day classroom programs are likely to provide inmates with more interaction time with the teacher. Typically, bridging teachers spend only about one hour each week with each student.

Greater Incentive for Inmate Participation. Finally, splitting education programs into half–day sessions could indirectly provide a greater incentive for inmates to participate in education programs. Some inmates who now decline education programs because they prefer to work in a prison job that provides pay now could do both on a half–day basis. Not all inmates who now have prison jobs are likely to want to go to school part–time due to the loss of current income. However, the ability to balance education and income may entice more inmates to participate in education programs—especially if they are rewarded with higher pay, as we have proposed, as they complete educational programs.

Addressing Potential Concerns With Half–Day Programs. Our proposal for half–day classes has some limitations. First, it would not completely solve CDCR’s current shortage of education program capacity. Even with our proposal, there would be program capacity for only a minority of inmates with reading abilities less than ninth grade. However, the correctional education system as a whole would be a step closer to meeting the educational needs of inmates.

Second, a move to half–day programs could slow the academic progress of inmates who could advance more quickly under full–day instruction. Accordingly, our proposal would allow inmates who want or need to participate in full–day education programs (perhaps to earn their GED before their parole release date) to do so. Alternatively, there may be opportunities to utilize other resources, such as peer tutors or voluntary evening classes, to assist inmates without taking up a classroom for a full day.

Third, half–day classes could affect prison operations. Because of their commitment to half–day education programs, two inmates in some instances might now work a half–day shift where a single inmate currently works a full–day shift. This would require custody staff to manage more frequent movement of inmates than is currently done. However, this generally should not require additional resources for security, because prisons are already budgeted for the custody staff needed to manage inmate movements several times during the typical prison day. In fact, we found that CDCR is effectively operating some of its nontraditional academic education programs as half–day classroom programs without requiring additional custody supervision.

Partner With PIA to Build Program Space

As discussed above, a lack of available classroom space is frequently a barrier to providing education programs within prison walls. In the future, should the Legislature decide to expand the capacity of prison education programs, it will likely need to address the lack of available classroom space in the prisons. One option the Legislature may wish to consider is meeting these space needs with modular education buildings purchased from PIA.