January 22, 2008

Hon. Don Perata

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Room 205, State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Senator Perata:

You requested that we analyze certain fiscal issues related to the health care reform (HCR) plan currently under consideration by the Legislature. The HCR consists of two parts: (1) the Health Care Security and Cost Reduction Act, ABX1 1 (Núñez), which passed the Assembly and was later amended on January 16, 2008 (subsequently referred to as the “bill”) and (2) the related initiative, entitled the “Secure and Affordable Health Care Act of 2008,” as filed December 28, 2007 with the state Attorney General (subsequently revised with technical amendments and referred to as the “initiative”). Our analysis is based, in part, on information provided by the administration and the author’s office (collectively referred to as the “proponents”). Below in our response to your request, we provide a brief overview of HCR and then answer the three questions you asked us to address:

- What are the expected revenues and costs of the reform plan once it is implemented, and how would those factors change after five years?

- What risks, cost pressures, and implications for the General Fund does the reform plan present?

- How does the Governor’s January 10, 2008 spending plan affect the reform plan’s underlying finances?

The HCR would create one of the largest programs in state government and directly affect virtually every Californian. In the time available for our analysis, we focused our review on the largest fiscal components in order to address your questions.

SUMMARY

We started our fiscal analysis of the HCR plan based on information and fiscal estimates provided by the proponents. We adjusted their fiscal estimates to correct for technical estimating errors and used our estimates of tobacco tax revenues instead of theirs. We then estimated the fiscal impact of HCR using two different assumptions of premiums: $250 per month per person (which is what the proponents have assumed for their estimates) and $300 per month per person because, as we explain later, there are reasons to believe that a $250 premium level may be difficult to achieve.

Based on our estimates, we conclude that under the $250 premium scenario, there are sufficient revenues to support the program in the first year of operation (2010-11). However, by the fifth year of the program (2014-15), annual costs exceed revenues by $300 million. Despite annual costs exceeding revenues in the fifth year, the program still has a positive cumulative fund balance because the collection of two revenue sources (tobacco tax and employer fees) start before program costs are incurred.

Under the $300 premium assumption, costs exceed revenues by $122 million in the first year of operation and this shortfall increases to $1.5 billion by the fifth year of the program. In addition, the fund balance shows a deficit of almost $4 billion by the end of that period, even with the early collection of the tobacco tax and employer fees.

In addition to the premium level, we have identified a number of other fiscal risks and uncertainties which could negatively affect the fiscal solvency of the plan by more than an additional $1.5 billion annually.

Overview of the HCR Plan

The bill and its companion ballot initiative would make significant changes to California’s existing health care system if they were implemented. In Figure 1, we provide a summary of significant HCR policy changes.

|

Figure 1

Key Components of HCR

Health Coverage Expansion |

|

Individual Mandate. Beginning July 1, 2010, every

California resident would be required to maintain a minimum level of

health insurance coverage, known as minimum creditable coverage,

that would be established by the Managed Risk Medical Insurance

Board (MRMIB). Exemptions to the mandate would be given to

individuals and families by MRMIB, based on income levels and

hardships. |

Health Insurance Market

Provisions. The Health Care Reform (HCR) would require

insurers to provide a range of health insurance coverage plans to

purchasers (“guaranteed issue”) who are subject to the individual

mandate. The health insurance coverage plans offered by insurers

would be required to meet coverage criteria that would be developed

by MRMIB. |

State Health Care Purchasing

Pool Program. The state would establish a new “purchasing

pool” program, the California Cooperative Health Insurance

Purchasing Program (Cal-CHIPP), administered by MRMIB. The board

would negotiate and purchase health insurance for eligible

enrollees, mainly employees (and their dependents) of employers who

pay a prescribed fee, and other persons that choose to purchase

health insurance through the pool. |

Public Health Care Program

Expansion and Support for Low-Income Persons. Public health

programs would be expanded to cover additional persons and certain

low-income persons would receive additional assistance as follows: |

· Healthy Families Program expansion for children

(regardless of immigration status) in families with incomes up to

300 percent of federal poverty level (FPL). The FPL is currently

about $20,700* annually for a family of four and about $10,200

annually for a single person. |

· Cal-CHIPP Healthy Families Plan to cover adults with

incomes between 100 percent and 250 percent of FPL. |

· Medi-Cal expansion to single, medically indigent

adults with incomes up to 250 percent of FPL—benefits may be less

than standard Medi-Cal. |

· Medi-Cal expansion to adults ages 19 and 20 earning

less than 250 percent of FPL—benefits may be less than traditional

Medi-Cal. |

· New coverage program for childless adults with incomes

under 100 percent of FPL—benefits may be less than traditional

Medi-Cal. |

· Individuals without employer coverage and with incomes

from 250 percent to 400 percent of FPL would receive a tax subsidy

to help purchase coverage through the pool. |

· Individuals and families earning less than 250 percent

of FPL can obtain coverage through the new purchasing pool and their

contribution would not exceed 5 percent of family income. |

· Persons with incomes up to 150 percent of FPL would

pay no premiums or out-of-pocket costs. |

Medi-Cal Provider Rate

Increases. The HCR also proposes to increase Medi-Cal rates

paid to physicians and hospitals. |

Prevention Programs. The

HCR would establish programs to improve management of high cost and

chronic

diseases including diabetes, and to promote tobacco cessation and

obesity prevention.

* Revised January 25, 2008. |

|

The initiative contains provisions to finance HCR. In Figure 2, we provide a summary of key components of HCR financing.

|

Figure 2

Key Components of HCR

Financing |

|

Federal Funds. The Health Care Reform (HCR)

anticipates federal funds will pay for a substantial portion of the

proposed coverage expansions and rate increases. The state would

need to obtain federal approval for amendments to existing waivers

and the state plan or obtain new ones in order to claim some of

these federal funds needed to finance HCR. |

Hospital Fee. The HCR would impose a 4 percent tax on

net patient revenues for private and public hospitals. |

Cigarette Tax Increase. The HCR would increase taxes

paid on cigarettes by $1.75 per pack. (Under current law this would

have the effect of increasing the excise tax on other tobacco

products.) These revenues would decline over time because of the

well-established ongoing erosion of smoking activity unrelated to

this measure. The initiative proposes to backfill (1) the

Proposition 99 Health Education Account, Research Account, and

portions of the Unallocated Account; (2) Proposition 10 programs

excluding children’s health insurance programs; and (3) and the

Breast Cancer Fund from the tax increase. |

Employer Contributions. Employers would be required to

meet a minimum spending level on health care for their workers of

between 1 percent and 6.5 percent of their Social Security wages

depending on the payroll size of the employer as follows: |

· 1 percent for firms with wages up to $250,000. |

· 4 percent for firms with wages up to $1 million. |

· 6 percent for firms with wages up to $15 million. |

· 6.5 percent for firms with wages over $15 million. |

Employers could meet the minimum spending level either by purchasing

health care services directly from providers or paying a fee to the

state (referred to as “pay or play”) thereby allowing their workers

to obtain coverage through a new state purchasing pool. Employer

contributions to the purchasing pool would also include so-called

“horizontal equity.” (Horizontal equity would allow individuals who

are offered employer coverage to choose instead to obtain coverage

through the California Cooperative Health Insurance Purchasing

Program [Cal-CHIPP]. For persons choosing Cal-CHIPP instead of

employer coverage, their employer’s contribution towards coverage

would follow them into the pool.) |

Individual Contributions. Individuals obtaining

coverage through the state purchasing pool would contribute

towards their coverage through premiums and potentially other

payments. |

County Share of Cost. Counties collectively would pay

40 percent of the costs of state coverage for some categories of

uninsured. These payments would reflect a shift in coverage from the

counties to the state for some persons, generally indigent adults. |

State Program Savings. When fully implemented, HCR

would result in annual savings by potentially eliminating or

restructuring some state health programs that would become redundant

under HCR. |

California Health Trust Fund. Under the initiative,

the California Health Trust Fund (CHTF) would be created in the

State Treasury. The HCR-related funds paid by employers, Cal-CHIPP

enrollees, cities, counties, hospitals, as well as proceeds from the

cigarette tax would be deposited into the CHTF. The moneys in the

fund would be exclusively available for providing health care

coverage and at the end of a fiscal year any monies that had not

been spent would be carried forward to the next fiscal year. |

|

Background

A Number of Components of HCR Subject to Appropriation by the Legislature. A number of components of HCR would not go into operation unless the Legislature appropriates funds for these purposes. These include the following:

- Medi-Cal rate increases for physicians.

- Expansion of Medi-Cal and Healthy Families Programs to include new eligibility categories.

- Grants to local health departments for obesity prevention and other prevention programs.

- Establishment of a statewide education and awareness program to inform all California residents of their health care individual mandate obligation.

For purposes of this analysis, we assume appropriations are made for components of HCR which require them.

HCR Time Line. We are informed by the proponents that their intent is to place the initiative on the November 2008 ballot for voter approval. If approved, HCR would be implemented on the schedule shown in Figure 3.

|

Figure 3

Time Line for

Implementation of Major Components of HCR |

|

· Cal-CHIPP Startup—January 2009. The

Managed Risk Medical Insurance Board would begin to implement the

California Cooperative Health Insurance Purchasing Program (Cal-CHIPP)

in preparation for starting to

provide health care coverage July 1, 2010. |

· Cigarette Tax Increase Goes Into Effect—May 1,

2009. The state would begin to collect revenues from the

cigarette tax increase. |

· Children’s Health Care Expansion—July 2009. Expansion of the Healthy Families Program and Medi-Cal to provide

services to additional children. |

· Employer Contribution (Pay or Play)—January

2010. Those employers that do not meet spending requirements

for providing health care to their workers would begin paying a fee

to the state. |

· Individual Mandate—July 2010. Coverage

is mandated for California residents and their dependents with some

exemptions. |

· Hospital Tax—July 2010. Tax on hospitals

equivalent to 4 percent of net patient revenues would go into

effect. |

· County Contribution—July 2010. Counties

would cover 40 percent of the costs of state coverage for some

categories of uninsured previously insured by them. |

|

Under this schedule, there would be less than 20 months between voter action and when the California Cooperative Health Insurance Purchasing Program (Cal-CHIPP) would begin offering coverage through the purchasing pool in July 2010. Implementation of HCR would be contingent on a finding by the Director of the Department of Finance (DOF) that sufficient state resources exist in the California Health Trust Fund (CHTF) to implement HCR during the first three years of operation. This is commonly referred to as the “trigger-on” provision. The bill, however, does not specify the date upon which the Director of DOF would have to make this finding. We discuss the trigger provisions of HCR in more detail later in this analysis.

Fiscal Analysis of HCR

The Proponents’ Estimate

The HCR plan would result in a number of costs to the state, and relies on a number of funding sources to support the program. The proponents of HCR have provided us with their estimate of the costs of and revenues supporting the plan. The key fiscal drivers of HCR are summarized in Figure 4.

|

Figure 4

Key Fiscal Drivers of Health Care Reform

(ABX1 1 and Related Initiative) |

|

Key Cost Components |

· Purchasing pool participation rates and premium levels |

· Expansions in Healthy Families and Medi-Cal coverage |

· Rate increases for hospitals and physicians |

· Tax credits |

· State administration costs |

Key Revenue Components |

· Hospital fee |

· Employer fee |

· Federal funds |

· Cigarette tax increase |

· Individual contributions |

· County funds |

|

The Gruber Model. The HCR plan contains many complicated interactions among its parts. To model the effects of population responses to HCR, proponents relied on the work of Massachusetts Institute of Technology economics professor Jonathan Gruber. He has created an economic model (subsequently called the Gruber model), that has been used to estimate many of the cost and revenue components of HCR. In our 2007-08 Budget: Perspectives and Issues, we describe some of the strengths and weaknesses of this model. It is important to note, however, that a number of elements of the plan, such as the hospital fee and cigarette tax increase on the revenue side and rate increases and program expansions on the spending side, are not addressed by the model. In addition, the model is not designed to estimate the effects of an economic slowdown on population responses.

The 2007 Baseline. The proponents developed a multiyear projection of the revenues and expenditures for HCR. The multiyear fiscal estimate provided by the proponents was calculated in three steps. First, they estimated what each cost and revenue component would have been in 2007 had HCR already been in place for several years. These results are referred to as the “full implementation” or “2007 baseline” results. Second, each of the 2007 baseline amounts was grown over multiple years using growth factors appropriate for that component. For example, the cost of expanding Medi-Cal to adults was grown at the projected growth rate for current Medi-Cal expenses, while the wage-based employer fee was projected to grow at the projected growth rate for wages. Finally, the estimates for the initial years of the program were adjusted to reflect a phase-up period. These phase-in adjustments were also component-specific. For example, the estimate assumes that only 50 percent of the people who ultimately would participate in the purchasing pool would do so in the first year of the program, but the hospital fee would be fully implemented in the first year.

LAO Approach to Analyzing the Fiscal Effects of HCR

In analyzing the fiscal effects of HCR, we began with the fiscal estimate provided to us by its proponents. We examined each cost and revenue component in this estimate. We found a number of their assumptions and calculations to be reasonable. There are other assumptions and calculations, such as the cost of “seamless enrollment,” about which we do not yet have enough information to draw a conclusion. In other cases, we identified a downside risk to the estimate depending on behavioral responses to HCR, changing economic conditions, or other factors. We also did a sensitivity analysis on several key elements of the plan to determine the fiscal impact on the bottom line. Finally, there are several items for which we disagree with the fiscal estimate and have developed our own estimate. In the section that follows, we describe the specific adjustments that we made.

It is important to note that this analysis is our preliminary fiscal assessment of HCR. We are currently in the process of analyzing the proposed HCR initiative for the Attorney General’s Office and are gathering additional information. It is possible that as a result of this process, our estimates may change.

LAO’s Specific Adjustments

A Technical Adjustment for Inflation. The estimate provided by HCR proponents begins with the 2007 baseline results described above. Each cost and revenue component from the 2007 base is then grown to subseq uent years using growth factors appropriate for that component. In the calculation provided to us by the proponents some of these growth factors were omitted. Specifically, the 2009 costs for the purchasing pool and the 2009 revenues from the employer fee reflected only one year of growth from the 2007 base calculation. In our calculations, the 2009 levels for these items are adjusted to reflect a second year of growth from 2007.

Tobacco Tax Revenues. A major component of the funding for HCR is a $1.75 per pack increase in the cigarette excise tax. This would raise the tax from $0.87 to $2.62 per pack of 20 cigarettes. We have made our own estimates of the cigarette tax component of HCR revenues. Our estimates differ from those of HCR’s proponents in three ways.

- Partial-Year Revenues Are HCR Revenue. The cigarette tax is scheduled to go into effect on May 1, 2009. Thus, there will be some revenue raised in the 2008-09 fiscal year. This additional revenue is not accounted for in the fiscal estimates provided to us by the plan’s proponents. We have included $222 million in 2008-09 cigarette tax revenues as a result.

- Some New Revenues Are Not HCR Revenues. Under current law, the increase in the cigarette tax also causes an automatic increase in the excise tax rate on other tobacco products. Also, because of the new higher price of other tobacco products and cigarettes, more Sales and Use Tax (SUT) revenues will be collected. Under current law, new revenues from the excise tax increase on other tobacco products would go to fund programs created by Proposition 99, not to HCR. Likewise, increases in SUT revenues would go to the General Fund, not to HCR. The dollar amounts included in the proponents’ estimate of HCR funding seem to include, however, revenue raised from the SUT and the other tobacco products tax. We have excluded from our estimates, revenues that would not go to HCR. As a result, our revenue estimate of HCR cigarette tax revenues is approximately $85 million lower than the proponents’ in 2009-10 and thereafter.

- More Rapid Long-Run Decline in Smoking. The funding analysis provided by proponents of HCR assumes that cigarette consumption is currently declining at a rate of 1 percent per year. Our analysis indicates that the underlying decline is closer to 3 percent per year, and we have therefore reduced our estimates of the revenues raised by the increased cigarette tax in future years accordingly. This annual reduction grows to about $100 million by 2014-15.

Administrative Start-Up Costs. The estimate provided by HCR proponents did not include any administrative costs to the state prior to fiscal year 2010-11. We believe that the state will incur substantial administrative costs between now and then in order to have programs in place on the schedule required by the plan. Our estimates include an adjustment for these start-up costs of $110 million spread over three years—2008-09 through 2010-11.

Impact of Premiums on Purchasing Pool Costs

Assumed Premiums May Be Too Low. Neither ABX1 1 nor the initiative specify the premium cost for the plan. This ultimately will be set and subsequently adjusted by the Managed Risk Medical Insurance Board (MRMIB) pursuant to statutory guidelines. The cost estimates in the reform plan for the purchasing pool assume a per member per month (pmpm)—essentially a premium—cost of coverage of $250 for those persons under 250 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) who would receive state subsidies. A critical fiscal question for HCR is whether MRMIB can design minimum benefit standards and a corresponding health coverage plan that insurers would be willing to offer at a price of $250 pmpm. This may be particularly challenging.

For example, according to the 2007 California Employer Health Benefits Survey, the average monthly premium for individuals with employer coverage was $374. In order to provide premium levels of $250 pmpm, the state will need to either negotiate a much lower rate than the average employer, or set the minimum benefit level substantially below the average employer-provided benefit level.

The proponents of HCR provided us with information to demonstrate that a $250 pmpm is possible. The information consisted of a range of scenarios developed by a private consulting firm that considered possible benefit packages and their related premiums. The premium scenarios ranged from $246 pmpm to $330 pmpm. Thus, the $250 pmpm assumed in the proponents’ overall cost estimate is very near the bottom end of the range of possible benefit packages identified by their own consultant.

The scenarios provided by the proponents demonstrate the sensitivity of premium levels to benefits. For example, the only difference between their $246 pmpm scenario and their $305 pmpm scenario is that the more costly package has more expansive drug coverage. Given the sensitivity of premium levels to choices of benefit packages, we believe it is prudent to consider the fiscal effects on the program if an alternative premium level in the middle of the range examined by the proponents is assumed.

A Failure to Meet Cost Targets Would Have Large Fiscal Effects. To test the fiscal effects of higher purchasing pool premiums, we asked that the Gruber model be run assuming $300 pmpm, rather than $250 pmpm. The results of this run suggest that the cost to the state of the purchasing pool would be about 12 percent higher at the $300 pmpm level. As a result, we estimate that a $300 pmpm would increase HCR’s cost by almost $500 million in 2010-11, and by over $1 billion per year beginning in 2012-13.

The Bottom Line—Significant Differences Between Estimates

Figure 5 compares the proponents’ fiscal estimates of HCR with our estimates under two different scenarios for two points in time: (1) the first year of operation (2010-11) and (2) the fifth year of operation (2014-15).

|

Figure 5

Net Fiscal Effect of HCR Alternative Estimates |

(In Millions) |

|

2010‑11 |

2014‑15 |

Projected

Balance in

2014‑15 |

Proponents |

$540 |

$245 |

$2,712 |

LAO, $250 pmpma scenario |

346 |

-300 |

684 |

LAO, $300 pmpm scenario |

-122 |

-1,457 |

-3,941 |

|

a Per member per

month. |

|

Proponents’ Estimate. The proponents estimate that in 2010-11 (the first year of HCR) revenues will exceed program expenditures by $540 million. By 2014-15, the fifth year of the program, revenues will still exceed expenditures, but by a smaller amount ($245 million). The proponents estimate that the program will have a projected balance of $2.7 billion by the fifth year of the program. Of this reserve, $1.7 billion is attributable to the fact the tobacco tax and employer fees start in May 2009 and January 2010, respectively, while most program expenditures do not start until July 2010.

LAO Estimates. Our estimates have been adjusted to account for our views on the technical inflation adjustment, tobacco taxes, and start-up administrative costs (as discussed above). In addition, one of our estimates assumes a $250 pmpm scenario and the other assumes a $300 pmpm scenario. Under our $250 pmpm scenario, we estimate that revenues exceed costs by $346 million in 2010-11, but that by 2014-15 expenditures exceed revenues by $300 million. The projected balance has declined to $684 million. The reason our estimate is different from the proponents even though we assume $250 pmpm as they do, is entirely attributable to our technical adjustment for inflation, tobacco taxes, and administrative start-up costs.

Under our $300 pmpm scenario, expenditures exceed revenues by $122 million in 2010-11 and the gap between expenditures and revenues increases to $1.5 billion by 2014-15. At the end of the five-year period, there is a cumulative shortfall of $3.9 billion between revenues and expenditures.

Detailed estimates supporting the conclusions reflected in Figure 5 are included in the enclosures. We note that we have included state program savings resulting from elimination or restructuring of state activities in our estimates. Enclosure A details the LAO $250 pmpm scenario. Enclosure B details the LAO $300 pmpm scenario. Enclosure C summarizes the scenarios for each year from 2008-09 through 2014-15.

Other Fiscal Risks and Cost Pressures

In addition to the specific fiscal adjustments we have made as a result of our analysis, we have identified a number of other fiscal risks and cost pressures. These risks, which total more than an additional $1.5 billion annually, are presented in Figure 6 and detailed below. Any one of these risks by itself, or in combination with other risks, could negatively affect HCR fiscal solvency. However, given the amount of time we had to prepare our analysis and the uncertainty that some of these risks would be realized, we did not incorporate these risks into our bottom line fiscal estimate discussed above. In many cases, we are not able to quantify a specific effect.

|

|

|

Figure 6

Other Fiscal Risks

and Cost Pressures of HCR |

|

(Dollars in

Millions) |

|

Risk |

Potential

Annual Cost |

|

Federal funding uncertainties |

$1,100 |

|

Medi-Cal |

(1,060) |

|

Healthy Families |

(40) |

|

Higher number of uninsured |

Hundreds of millions |

|

Long-run health care inflation could be higher (fifth year) |

$300 |

|

Adverse health selection effect |

Unknown |

|

Employer behavior could affect level of fee revenues |

$200 |

|

Tax credits implementation |

Unknown |

|

Enforcement of the individual mandate |

Unknown |

|

Other |

|

|

Seamless enrollment (per 100,000 persons) |

$30 |

|

IHSS |

$120 |

|

Response to tobacco tax increase |

Unknown |

|

Legal issues (Employee Retirement Income Security Act) |

Unknown |

|

|

Some Federal Funding at Risk

The reform plan relies in part on $4.4 billion in federal matching funds. Our review finds that a total of about $1.1 billion in federal matching funds assumed by the reform plan are at risk.

Some Federal Funding for Medi-Cal Program Expansion Uncertain

Most Federal Funds Accessible Under Existing Rules. At the time this analysis was prepared we had not received information that we had requested from the proponents regarding the amount of federal matching funds dependent on federal waivers. We estimate that about $3.3 billion of the plan’s estimated $4.4 billion in annual federal matching funds would likely be available without the need for the state to amend its current waivers or obtain new ones. These amounts are likely to be available through the increased flexibility in Medicaid benefit design permitted by the federal Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 or as the standard federal match for Medi-Cal provider rates and coverage expansions allowed under federal law. Nevertheless, there are uncertainties regarding some other federal funds which would require federal waivers or state plan amendments.

Waivers Needed to Redirect Federal Funds. Typically, adults are only eligible for Medi-Cal if they have children or become aged or disabled. The reform plan assumes that California will be able to obtain a new or amended federal waiver for the state to provide Medi-Cal coverage for certain childless adults (through the purchasing pool for some groups). We estimate that a waiver would need to provide $1.1 billion in new or redirected federal matching funds annually. Generally, federal waivers require budget neutrality, meaning that the state must demonstrate that a proposed change will not result in any additional federal costs. To meet the $1.1 billion annual cost while maintaining federal budget neutrality, the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) asserts that California would be able to redirect various funds. We evaluate the availability of these funds below.

Current Federal Hospital Waiver Funding at Risk. California restructured its Medi-Cal hospital financing system under a federal five-year waiver beginning in 2005-06. This waiver provides increased federal funding for hospitals, including an allotment of $766 million annually known as the “Safety Net Care Pool” (SNCP), which public hospitals can access to help pay for indigent care costs. California obtained this increased federal funding in part by agreeing to forego the opportunity to implement a “provider tax” on hospitals or physicians. However, the reform plan proposes a 4 percent tax on hospital revenues.

The reform plan would redirect $666 million of these current SNCP funds to pay a portion of the costs for expanded coverage for adults, as described above, and designates the remaining $100 million as reimbursement for the costs of clinics operated by public hospitals. The plan assumes that the state would be able to amend and renew its Medi-Cal hospital waiver in 2010 to redirect the SNCP funding while levying the new 4 percent tax on hospital revenue. Because of the tax prohibition included in the current waiver, it is uncertain whether the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) would grant an amended waiver, putting this $766 million in SNCP funds at risk.

Amount of Available DSH Funding Uncertain. The proponents assume that a portion of the annual Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments would be available under an amended waiver to pay for expanded health coverage. Public hospitals that meet certain requirements for providing uncompensated care services currently receive these payments, but DHCS estimates that up to $600 million annually in DSH payments would go unused following health reform coverage expansions and could therefore be redirected. We find it plausible in principle that CMS would approve a waiver redirecting these funds for coverage expansion, but the true amount available, and the time frame in which the state would have access to it, could depend on the actual reduction in uncompensated care services provided by public hospitals following enactment of the reform proposals. This depends in part on how successful the state is in enforcing the proposed individual mandate and enrolling uninsured persons in new coverage. Thus, the availability of these funds is uncertain at this time.

Federal Funding for Other Programs Uncertain

New Federal Rules Place Some Children’s Funds at Risk. The CMS recently issued administrative restrictions for states seeking to expand federally funded health coverage programs beyond 250 percent of FPL. These rules include a requirement that states enroll in their programs 95 percent of the eligible population below 200 percent of FPL before CMS will approve an expansion above 250 percent. While CMS initially issued these rules in 2007 for the State Children’s Health Insurance Program, known as the Healthy Families Program (HFP) in California, a recent CMS announcement indicates that it will apply these rules to Medicaid funding as well. Whether California would meet the requirements under such a policy is not clear at this time. The extent to which CMS will enforce this policy is also unclear, but these rules create risk that the Medicaid funding for the HFP expansion above 250 percent of FPL would not be available. We estimate this funding to be about $40 million annually.

Higher Number of Uninsured May Drive Costs Higher

Estimates of the Uninsured Vary. The projected size and costs of all coverage expansions in the reform plan are based on estimates of the uninsured population drawn from the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS), conducted biennially by the University of California, Los Angeles. The CHIS is very useful as a source of California-specific data, but it has consistently produced estimates of the uninsured population that are lower than various federal surveys that use different survey methods. For example, the 2003 CHIS indicated that 4.9 million Californians were uninsured at any given time during the year. By contrast, the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), administered by the U.S. Census Bureau, estimated the number of Californians uninsured at any given time in 2003 to be 6.3 million, 31 percent more than the CHIS estimate. There is reason to believe that other federal surveys may overcount the number of California uninsured, but it appears possible that the CHIS moderately undercounts the total uninsured population. The proponents have indicated that they have made some adjustments to the CHIS data to account for the differences described above. Nonetheless, we believe there is still a risk that their estimate of the uninsured is too low.

More Uninsured Could Significantly Increase Costs. The Gruber model estimates that 3.6 million currently uninsured Californians will become insured under this plan. If the initial number of uninsured has been undercounted by 30 percent (as suggested by SIPP), we would expect at least an additional 1 million persons to become insured under this proposal (bringing the total to 4.6 million). If the actual number of uninsured is somewhere in between the two survey estimates—at about 500,000 more people covered than assumed for the proponents’ cost estimate—we estimate net additional costs to the state in the hundreds of millions of dollars once the program is fully implemented.

Economic Slowdown Could Increase the Number of Uninsured. California is subject periodically to slowdowns in economic activity. During these times, unemployment often increases. This reduces the number of Californians with access to employer-provided healthcare. A recession similar to the one California experienced in the early 1990s could result in hundreds of thousands of Californians losing access to employer-provided health care, thereby increasing the costs for the HCR plan.

Long-Run Health Care Inflation Could Be Higher

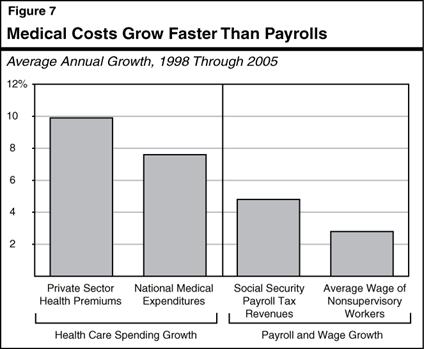

In recent years, as shown in Figure 7, costs have risen faster in the health care sector than in the economy as a whole, and wages in particular. The proponents’ cost estimate includes assumptions about the expected inflation rate for each cost and revenue component of the plan. The overall cost of the plan is sensitive to many of these assumptions.

Mismatch Likely Between Growth in Costs and Revenues. One concern is that many of the cost components in the HCR proposal are likely to grow at a rate similar to medical cost growth, while some of the revenue sources used in the plan will likely grow at the same or similar rate as wage and salary payroll. If so, rapid growth in health costs could create an imbalance between revenues and costs in future years.

The fact that a major share of the plan’s financing comes from the hospital fee provides some protection against this outcome. Revenues from the hospital fee are likely to increase at roughly the same general pace as medical care costs. This will help to protect the CHTF against rapid medical cost increases.

However, other elements of the plan will be affected. Specifically, the cost-sharing payments by subsidized workers can be expected to grow more slowly than medical costs, as will the payroll fee levied on non-offering employers. As shown in the figure, growth rates in payroll and wages have historically lagged health spending growth. Therefore, it is likely that employer premium contributions for subsidized workers would also grow more slowly than health care costs.

How Big Could the Problem Be? We estimate that a 0.5 percent per year increase in medical inflation above that assumed by the proponents would result in potential annual costs by the fifth year of implementation of $300 million, or a cumulative net cost to the state by 2014-15 of approximately $1 billion.

Program Features That May Reduce Long-Run Health Costs. The HCR plan contains several provisions that could help reduce health care costs over time. Some of these provisions are intended to hold down cost growth through direct administrative or regulatory controls. However, the details as to how such controls will be implemented has generally been left to the discretion of state agencies. For example, there is a requirement that health plans, insurers, and hospitals spend at least 85 percent of every dollar in revenues on patient care. Such a provision could potentially be used to limit health cost growth, but the actual effect would depend on technical regulatory details, such as the exact definition of “patient care” and revenues. Until there is more detail on how these direct administrative controls would be implemented, it is difficult to evaluate their likely effectiveness in restricting health care inflation.

The HCR plan also contains some programs that may control costs indirectly. Specifically, HCR would support or create programs aimed at reducing morbidity related to tobacco, obesity, and diabetes. If successful, these programs should reduce some of the demand for health care services, and, hence, related health care costs.

Reductions in Uncompensated Care May Not Keep Health Care Costs Down. The increased coverage funding under the plan is likely to reduce the amount of uncompensated care in the system. This will, in turn, reduce the “cost shifting” of non-reimbursed care costs on to private payers. This could help restrain growth in health care costs. However, there are several reasons why a reduction in cost shifting may not reduce health cost growth:

- First, reductions in uncompensated care may in some circumstances show up as increases in profits to insurers and providers, if they decide not to reduce the amount they charge consumers of health services.

- Second, a reduction in cost shifting might lead to a single, one-time reduction in costs, without reducing the underlying rate of future inflation.

Both of these factors make it difficult to predict whether a reduction in uncompensated care funded by this plan will have a lasting impact on medical care inflation.

Adverse Health Selection Could Also Substantially Increase Costs

The Impact of Adverse Selection. Adverse health selection occurs when the people who choose to enter a public plan are systematically less healthy than the average insured individual. This is an especially important factor to be aware of when establishing a health program, because a few patients with chronic or expensive illnesses account for a large fraction of health care costs in any one year. In 2002, for example, 5 percent of the insured population accounted for approximately one-half of all health care costs, while the least-expensive 50 percent of the insured population accounted for only 3 percent of total health care costs. Private health insurance plans or employers can therefore benefit greatly from transferring responsibility for the most expensive patients to the government.

If adverse selection does occur, and unhealthy patients participate disproportionately in the new state insurance pool, it could result in insurers being unwilling to offer plans to the pool at low premiums. If this results in increased premiums, net costs to the state of the HCR could increase substantially.

The HCR Plan Attempts to Address Adverse Selection. The current HCR plan attempts to address the adverse selection problem. The plan includes a guaranteed issue requirement that prevents private insurers from rejecting unhealthy applicants and a community rating policy that prohibits setting prohibitively high prices for them. Without these requirements, private insurers could opt to insure only healthy individuals, leaving a disproportionately high number of unhealthy people in the state pool.

The plan also includes a horizontal equity provision that applies to employees with access to employer-provided insurance who instead choose to purchase insurance through the state pool. When this happens, the contribution that the employer would have made to its in-house insurance plan on behalf of that employee is transferred to the pool. This removes incentives that the employer may have had to design an in-house insurance plan in a way that would discourage participation. To the extent, however, that these three measures are not as successful as intended, the costs of HCR could increase substantially by an unknown amount.

Employer Behavior Could Affect Level of Fee Revenues

The HCR plan requires employers to pay a specified percentage of their payroll on health benefits for their employees or pay the difference to a state fund. The fee is reduced by credits earned for direct expenditures on employee health care costs. In concept, the reform plan assumes that employers have two choices: offer health insurance to their employees or pay the employer fee. The structure of HCR, however, could result in other choices. For example, it is possible that employers could provide health-related benefits, such as providing employees with a gym to exercise in, that count toward the health care contribution requirement specified in HCR but fall short of constituting actual health coverage. Another possibility is that some employers whose low-income workers are now uninsured (that is, do not have health coverage through a spouse or their own individual coverage) will generate credits to offset their employer health care fee by providing significant health savings account contributions as a benefit for their higher-income workers, rather than providing coverage for their lower-income workers. Behaviors that increase employer fee credits without increasing the number of insured employees would result in a reduction in employer payroll fee revenues, but no offsetting savings in HCR costs.

Amendments have been incorporated into ABX1 1, as amended January 16, 2008, which attempt to address the above issue by restricting employers’ ability to use other expenditures to offset their health care fee. Professor Gruber has indicated that while the amendments go far to forestall the erosion of employer payroll fee revenues, it is still likely that some reduction in such revenues will occur. He has suggested that the net effect on the “bottom line” would be 5 percent to 15 percent of the fee level. Taking the midpoint of this range results in an increase in net costs to HCR of approximately $200 million in 2010‑11.

Tax Credit Implementation Sensitive to Age Distribution and Inflation

The HCR plan provides for a tax credit to defray a portion of the cost of health insurance premiums for qualified taxpayers with incomes between 250 percent and 400 percent of FPL. The credit is for a portion of the cost of premiums purchased through MRMIB that exceeds 5.5 percent of the taxpayer’s income. The cost of this tax credit will be sensitive to a number of factors. We believe that the proponents’ estimates are reasonable, but there are a number of downside risks which we have not been able to quantify, as detailed below.

Age Distribution of Credit Claimants Is Important. The dollar amount of credit that a taxpayer can claim is capped. The cap is based on the taxpayer’s age and family status. For singles, no credit is allowed for people aged 19 to 29, whereas people aged 60 to 64 may claim up to $3,762 per year. For families, the range is from $1,500 per year for 19 to 29 year olds to $8,772 per year for 60 to 64 year olds. Thus, the cost of the credit will depend not only on the number of people claiming it, but also on their ages. The estimated cost of the credit assumes relatively few claimants in the groups with the highest caps. This is reasonable because there are fewer 60 to 64 year olds in the 250 percent to 400 percent of FPL income range than there are 19 to 29 year olds. There is a risk, however, that higher-than-expected take-up rates in the groups with high caps could increase the total cost of the credit. Also, we note that, because of the structure of the credit caps, the general aging of the population predicted by our demographic forecast will cause the cost of this credit to increase about 1 percent per year faster than it would have if the credit caps did not vary by age.

Medical Cost Inflation. The cost of the tax credit is sensitive to inflation in health care premiums for two reasons:

- First, the credit caps described above are indexed to the Consumer Price Index for All-Urban Consumers for Medical Costs. If this inflation rate increases faster than expected, so too will the cost of this credit.

- The second reason medical inflation will matter comes from the fact that the credit can only be claimed on the portion of a taxpayer’s premium that exceeds 5.5 percent of their income. Some taxpayers may initially select a health care plan with premiums very near this 5.5 percent of income floor. Initially, they will claim little or no credit. If medical inflation outpaces wage inflation, their health care premiums will soon exceed the 5.5 percent of income floor. For these taxpayers, the increase in the amount of credit they claim will be very large relative to the amount of credit they claimed initially.

Advancability. The plan states that it is the intent of the Legislature to make the tax credit advancable. Since this statement is only intent language, it is not possible to determine its effect. The concept of advancability is to allow people to use these tax credits to pay their insurance premiums at the beginning of a year, even though tax credits cannot be calculated until some time after the year has ended. To do this, the amount of the advance will be based on an earlier year’s tax calculations. We caution that enforcement issues may arise in cases where the amount of credit advanced is greater than the amount of credit that the taxpayer ultimately earns.

Enforcement of the Individual Mandate—Questions Remain

The HCR package requires, with limited exceptions, all Californians to carry health insurance. This mandate produces two major fiscal effects. First, to the extent that newly insured people (or their employers) pay their new health care premiums, it increases the overall funding for health care in the state. Second, it will cause more people to enter state-subsidized programs, which increases the cost of the state subsidies to those programs.

Provisions on Exemptions From the Mandate Not Yet Determined. The HCR plan specifies that persons with family incomes of less than 250 percent of FPL would be exempt from the mandate if their health costs exceed 5 percent of their family income. However, the plan does not define the minimum level of coverage or certain other hardship and affordability mandate exemptions for which residents could apply. Instead, the HCR plan requires MRMIB to determine these standards and the processes for exemption applications. We cannot, therefore, estimate the number of exemptions that will be granted, or the fiscal effect of granting those exemptions.

Effectiveness of Mandate Enforcement Unclear. The reform plan directs MRMIB to establish procedures to enforce the individual mandate and work with health care entities, such as local agencies, health care providers, and health insurers, to develop ways to facilitate enrollment into health coverage. However, the lack of enforcement procedure detail in the plan and the lack of penalties for noncompliance make the effectiveness of the individual mandate highly uncertain. This uncertainty has conflicting fiscal implications for the state. To the extent that the state is unable to identify noncompliant persons and enroll them in coverage, costs to the state would be lower. However, to the extent that noncompliance is high and the state does identify those persons, costs to the state could be higher than those estimated by the proponents. The net effect of noncompliance on HCR costs is unknown.

Other Risk Issues

Seamless Enrollment. Beginning July 2010, the reform plan would require all residents that have been in the state for at least six months to maintain “minimum creditable coverage” unless they qualify for certain exemptions. Under seamless enrollment, people accessing health care services who are found to have been without adequate health insurance for 62 days will be automatically signed up for a health insurance program. The state will pay the person’s initial health care premiums, then attempt to recover the appropriate amount of money from that person. The proponents estimate that the state would incur net costs of $570 million in the first year that reform is implemented. After the first year, the number of uninsured persons accessing health care should decrease, and the amount of seamless enrollment payments recovered by the state should increase. The proponents estimate that the net cost of seamless enrollment will decline to $132 million in 2012‑13. In the event that fewer people than expected initially comply with the mandate, however, more people would be enrolled via seamless enrollment. Based on the limited information that we have received, it appears that for each additional 100,000 persons enrolled this way, the net cost to the state would be about $30 million higher than the proponents’ estimate.

Increase in Hourly IHSS Health Benefit Contribution. Currently the state participates in In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) provider healthcare up to $0.60 per hour, and wages up to $11.50 per hour, for a total of $12.10 per hour. Of this $12.10, the federal government pays 50 percent, and the remainder is shared 65 percent by the state and 35 percent by the counties. The ABX1 1 increases the amount for which the state will participate in heath benefits for IHSS providers from $0.60 to $1.35 per hour, and thus, increases state participation in combined wages and health benefits from $12.10 to $12.85 per hour. (As with current law, the measure links these increases to a trigger mechanism related to General Fund revenue growth. In the last 20 years, General Fund revenue growth met the trigger threshold 13 times.)

The ABX1 1 increases the state’s General Fund exposure for IHSS costs. This is because it raises the total level of state participation. As counties increase wages and benefits over the maximum of $12.10 per hour currently authorized, the state will experience General Fund costs that would not have occurred in the absence of this bill. The increase in the General Fund exposure is estimated to be about $40 million in 2010‑11, increasing to about $145 million in 2014‑15. These costs would only be fully realized when all counties raise combined wages and benefits to $12.85 per hour. The proponents assume a cost of $72 million in 2014‑15.

Uncertainty Regarding Responsibility for IHSS Employer Contribution. In addition to the fiscal effect noted above, under the provisions of the initiative and the bill (and their interaction with current law), it is unclear whether the state, federal, and/or county governments would be responsible for employer contributions for expanded health care coverage under ABX1 1 for IHSS providers. If only the state and federal governments were found to be responsible, this may create an incentive to shift health contribution costs to the state, in the amount of approximately $50 million in 2010‑11 and increasing amounts thereafter.

Consumer Response to Cigarette Tax Increase May Reduce Revenues. Many studies have attempted to calculate what consumers’ reactions will be to an increase in cigarette prices due to a tax change. These studies are based primarily on responses to past tax and price changes. The problem is there are very few cigarette tax increases in history of the sheer size being considered here, bringing uncertainty as to how accurate these calculations will be for this measure’s larger tax increase. Thus, while a reasonable assumption for this occurrence is incorporated into our cigarette tax estimates, if consumers are more responsive than anticipated, revenue from the cigarette tax would be less than estimated.

Potential Exists for Legal Challenges. The reform plan would mandate that all employers spend a certain percentage of their Social Security payroll on employee health benefits or pay the difference into the state health purchasing pool. This “pay-or-play” mandate may conflict with a federal law known as the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). The ERISA was enacted to protect interstate commerce and the interests of participants in employee benefit plans and their beneficiaries, and has been interpreted by the courts to generally prohibit the states from requiring employers to provide health insurance coverage to their employees. We acknowledge that ERISA represents a risk to HCR. The initiative contains language that if parts of it are found to be invalid, the remaining parts can go into effect.

Implications for General Fund of HCR

Analyzing the implications to the General Fund of HCR is a difficult task given the complexity of the program, its financing, and the interrelationship with existing state programs. Many programmatic and funding details of HCR are subject to future actions by the Legislature and the administration and therefore are not known at this time. Proponents cite the trigger on and trigger off provisions of the bill and the initiative as key mechanisms to ensure fiscal viability and therefore minimize exposure to the General Fund. We discuss these provisions below. We then highlight various factors that pose risk to the General Fund.

Some HCR Programs Contingent on Fiscal Findings

Trigger Provisions Meant to Ensure Review of Fiscal Viability. The reform plan’s implementation would be contingent on a finding by the Director of DOF that the financial resources necessary to implement the plan are available. We refer to this as the trigger on provision. The Director would file a finding with the Secretary of State that all of the following conditions exist: (1) based on reasonable financial projections, sufficient state resources will exist in the CHTF to implement the plan taking into consideration the resources that will be available, during the first three years of operation, (2) required federal approvals for program changes under the act have been obtained or can reasonably be expected to be obtained by the time those programs are implemented, and (3) required federal resources will be available to implement the act based on the anticipated schedule of review and approval of state plan amendments and waivers applicable to HCR implementation.

Beginning the year following implementation of HCR, its continued operation would be contingent on a finding by the Director of DOF that the financial resources to continue operating are available. We refer to this as the “trigger off” provision. Twice each state fiscal year, at times deemed appropriate by the Director of DOF, the Director would review whether based on reasonable financial projections, revenues generated to fund HCR are sufficient to support the continued operation of HCR programs. If the Director determines that there are insufficient funds, then the Director will report this to the Legislature. If the Legislature does not address the fiscal shortfall within 180 days of notification by the Director, the laws in effect prior to HCR would go back into effect on the first January 1 that falls at least 270 days after the Director’s notification.

Analyst’s Concerns. Both the trigger on and trigger off provisions give the executive branch of government significant discretion in evaluating whether the financial resources necessary to implement HCR are available. Overall, we are concerned with the vagueness of the trigger on and trigger off provision. We have identified a number of specific issues with regard to the trigger on provision. First, the bill is unclear as to how a reasonable financial projection should be prepared and what factors such a projection should take into account. Second, the bill does not define “sufficient state resources” in terms of how it relates to funds delineated for HCR versus existing state resources and commitments. Third, HCR may be implemented if federal approvals for program changes can reasonably be expected to be obtained, opening the possibility that some federal approvals would not be obtained prior to implementation.

The trigger on provision also does not specify when the Director of DOF would certify with the Secretary of State that the circumstances described above exist and therefore HCR implementation could go forward. Nonetheless, even before the initiative is considered by voters in November, state departments would have to begin working on HCR implementation in order to meet the time line contained in the bill. This creates a scenario in which state resources would be allocated to implement HCR even before it is known whether the fiscal circumstances exist that would allow HCR to go forward.

Finally, the timing of the trigger off fiscal reviews by DOF put the state at some risk of operating HCR for up to almost 20 months after a shortfall is reported by the Director of DOF. For example, if the Director of DOF notified the Legislature on May 15, 2013 that there was a shortfall, the Legislature would have 180 days to act, or by November 10, 2013. If the Legislature did not address the financial imbalance, HCR would stop operating “the first January 1 that falls at least 270 days after the notification…” In this scenario, February 8, 2014 is the date 270 days after the May notification. Since HCR would not stop operating until the first January after the 270 day period had expired, it could continue operating on an unsound fiscal basis for more than ten months beyond February—until December 31, 2014. The measures are silent on how such a gap would be addressed.

Factors That Pose Risk to the General Fund

There are a number of factors that pose risk to the General Fund, such as those discussed below:

- Funding Source Outside of State Control. The HCR plan, as discussed earlier, places a heavy reliance on the availability of federal funds. Congress and the President are facing their own fiscal challenges at the national level. To the extent these funds do not materialize, there will be additional expenditure pressure on the General Fund.

- Funding Source Sunsets in 2015. The initiative’s hospital fee is scheduled to sunset on July 1, 2015. Thus, a major source of program funding would not be available unless reauthorized, potentially putting pressure on the General Fund in future years.

- Access to Medical Care. After implementation, according to the proponents’ estimates, more than 3.5 million people would come to depend on HCR for health care coverage. Stopping the program due to funding shortfalls would represent a hardship for many of these persons and a serious disruption to their access to medical care for others. It is likely that significant public pressure would be aimed at the state to find a means to continue funding for HCR.

Ultimately, in our view, the state General Fund would be the ultimate backstop for HCR. Therefore, if HCR were to experience an operating shortfall, it could create pressure on the General Fund.

Interaction With Proposed 2008‑09 State Budget

Implementing HCR by July 2010 would require several state agencies to begin work in the 2008‑09 state fiscal year and continue through 2009‑10. Our analysis indicates that implementation of HCR would create additional General Fund costs and exacerbate the 2008‑09 budget shortfall.

Governor’s Budget Proposal Runs Counter to HCR

The Governor’s budget plan was released on January 10, 2008 and included significant proposals affecting health care programs, many of them complex in nature. In all, the budget proposes more than $17 billion in solutions. In some cases, the Governor’s budget plan appears to run counter to proposals in HCR. For example, one of the Governor’s proposals is to reduce provider payments for physicians and other medical services providers to save about $602 million in the budget year. However, HCR assumes in 2010-11 a $500 million rate increase for Medi-Cal physicians subject to appropriation by the Legislature.

State Administrative Costs Would Increase in 2008‑09

The Governor’s budget plan does not anticipate any HCR implementation activities in 2008-09. Since certain program expansions—most notably the childrens’ health expansion—would begin July 2009, some administrative costs would be incurred in late 2008 or early 2009 in order to meet this date. The proponents recognize that there will need to be implementation activities in 2008-09 and 2009-10 which will result in increased costs. They have identified costs of about $110 million for implementation activities. However, they have not identified how these costs would be distributed across 2008-09 and 2009-10.

Short-Term Pressure on State Funds to Initially Implement Some Proposals. There would be short-term pressure to initially use state funds to pay for some of the startup costs associated with HCR because HCR revenues (tobacco tax would be implemented May 1, 2009, and the employer fee would be implemented January 1, 2010) would not begin early enough to offset these costs. For example, it is likely that MRMIB would begin working on the expansion of HFP to undocumented children and children in families with incomes under 300 percent of the FPL in early 2009 (since this expansion is effective July 2009). However, the first HCR revenue source that could be used to pay for these administrative costs would not be available until May 2009.

Costs and Timing of Information Technology (IT) Changes. Similarly, HCR will likely result in changes to existing IT systems and the development of new IT systems. Procurement and development of some of these systems would need to begin at least 24-months prior to implementation of the system. An example of such a system would be a new nontax debt collection system to collect health care premiums at the Franchise Tax Board. However, revenue sources to pay for these development costs in 2008 and early 2009 have not been identified. The proponents have indicated that if HCR goes forward, legislation would be needed to provide funding and administrative flexibility for departments to undertake necessary activities to implement this measure by the deadlines established in the bill.

Clearly, the thrust of the administration’s 2008-09 spending plan to reduce state spending across-the-board, including health programs, runs counter to the thrust of program expansions in HCR. Given the magnitude of changes proposed in the budget, we are likely to identify additional interactions in the coming weeks.

Conclusion

Any plan to reform the state’s health care system, by the nature of its complexity, will involve financial risk over the long term. Many of the risks discussed above would be shared by any health reform plans that attempt to maintain the current system of employer-provided coverage while expanding public programs to cover the uninsured. We believe it is important to examine both near- and long-term issues in evaluating the fiscal viability of the HCR Plan.

If you have any questions regarding our analysis, please contact me at 445-4656.

Sincerely,

Elizabeth G. Hill

Legislative Analyst

Enclosures

Enclosure A

|

|

|

LAO Health Care Reform Fiscal Summary |

|

(In Millions) |

|

|

$250

PMPMa |

|

|

2010-11 |

2014-15 |

|

Costs |

|

|

|

Purchasing pool |

$4,191 |

$10,398 |

|

Medi-Cal and Healthy Families expansion

(children) |

1,521 |

2,166 |

|

Medi-Cal expansion (adults) |

555 |

1,375 |

|

Tax credits |

270 |

661 |

|

Expanded access to primary care funding

increase |

140 |

148 |

|

Obesity/tobacco/diabetes/healthy actions |

180 |

208 |

|

Section 125 tax treatment (state revenue loss) |

149 |

406 |

|

Seamless enrollment |

570 |

123 |

|

Medi-Cal rate increases |

4,363 |

5,288 |

|

In-Home Supportive Services health benefits |

21 |

72 |

|

State administration costs |

503 |

569 |

|

Total Costs |

($12,464) |

($21,414) |

|

Revenues and Other Funding |

|

|

|

Employer fee |

$1,846 |

$2,176 |

|

Employer-horizontal equity |

598 |

1,619 |

|

Hospital fee |

3,069 |

4,026 |

|

Individual contributions |

1,496 |

3,856 |

|

Federal funds |

3,669 |

5,785 |

|

County fund shift |

580 |

1,417 |

|

Tobacco tax increase |

1,341 |

1,201 |

|

State Program Savings |

212 |

1,034 |

|

Total Revenues |

($12,810) |

($21,114) |

|

Differences |

$346 |

-$300 |

|

|

|

a Per member per

month. |

|

Detail may not total

due to rounding. |

|

|

Enclosure B

|

|

|

LAO Health Care Reform

Fiscal Summary |

|

(In Millions) |

|

|

$300 PMPMa |

|

|

2010‑11 |

2014‑15 |

|

Costs |

|

|

|

Purchasing pool |

$4,703 |

$11,667 |

|

Medi-Cal and Healthy Families expansion

(children) |

1,521 |

2,166 |

|

Medi-Cal expansion (adults) |

555 |

1,375 |

|

Tax credits |

270 |

661 |

|

Expanded access to primary care funding

increase |

140 |

148 |

|

Obesity/tobacco/diabetes/healthy actions |

180 |

208 |

|

Section 125 tax treatment (state revenue loss) |

149 |

406 |

|

Seamless enrollment |

570 |

123 |

|

Medi-Cal rate increases |

4,363 |

5,288 |

|

In-Home Supportive Services health benefits |

21 |

72 |

|

State administration costs |

503 |

569 |

|

Total

Costs |

($12,975) |

($22,683) |

|

Revenues and

Other Funding |

|

|

|

Employer fee |

$1,852 |

$2,183 |

|

Employer-horizontal equity |

645 |

1,749 |

|

Hospital fee |

3,069 |

4,026 |

|

Individual contributions |

1,486 |

3,832 |

|

Federal funds |

3,669 |

5,785 |

|

County fund shift |

580 |

1,417 |

|

Tobacco tax increase |

1,341 |

1,201 |

|

State program savings |

212 |

1,034 |

|

Total Revenues |

($12,852) |

($21,226) |

|

Differences |

-$122 |

-$1,457 |

|

|

|

a Per member per

month. |

|

Detail may not total

due to rounding. |

|

|

Enclosure C

|

|

|

Net Fiscal Effect of HCR

Alternative Estimates |

|

(In Millions) |

|

|

2008-09 |

2009-10 |

2010-11 |

2011-12 |

2012-13 |

2013-14 |

2014-15 |

Cumulative |

|

Proponents |

— |

$1,670 |

$540 |

$17 |

-$6 |

$247 |

$245 |

$2,712 |

|

LAO, $250 PMPMa |

$192 |

1,525 |

346 |

-354 |

-472 |

-253 |

-300 |

684 |

|

LAO, $300 PMPM |

192 |

1,527 |

-122 |

-1,214 |

-1,514 |

-1,352 |

-1,457 |

-3,941 |

|

|

|

a Per member per

month. |

|

|

Return to LAO Home Page