May 29, 2009

Achieving Better Outcomes For Adult Probation

Executive Summary

(Short video summary)

County probation departments in California supervise roughly 350,000 adult offenders in their community. In addition to supervision, these departments also refer probationers to a variety of rehabilitation and treatment programs. Although the probation programs and supervision are a local responsibility, their performance affects state–level public safety programs. This is because adult offenders that fail on probation can have their probation term revoked and be sentenced to state prison, where it costs the state on average approximately $49,000 per year to incarcerate an offender.

In this report, we review the adult probation system in California and present recommendations for improving the system’s public safety and fiscal outcomes. In general, we find that many county probation departments are not operating according to the best practices identified by experts and are underperforming in key outcome measures (such as the percentage of probationers successfully completing probation). We also found that the current funding model for probation provides an unintended incentive for local agencies to revoke probation failures to state prison instead of utilizing alternative community–based sanctions. Our findings and recommendations are summarized in Figure 1.

In order to improve probation outcomes and reduce state prison costs, we recommend that the Legislature create a new program that would provide financial incentives for county probation departments to reduce their revocations to state prison. The program would be funded from a portion of the savings to the state that would result from a reduction in the number of probationers entering the state correctional system. Probation departments would use the financial incentive payments to implement the best practices identified by experts, thereby promoting better public safety outcomes.

Introduction

In California, the supervision of criminal offenders in the community by probation departments has traditionally been funded and administered by counties. This is consistent with the state’s general approach of giving local governments the fiscal and managerial responsibility for most public safety agencies, such as police and sheriff’s departments. Cities and counties thus maintain maximum flexibility to develop and implement those practices that best meet the needs and priorities of their particular communities. However, the actions of local agencies, particularly in the area of probation, affect state–level public safety programs. For example, an adult offender who fails on probation, either by violating the terms of probation or by committing a new crime, can be sent by the courts to state prison, where it now costs the state on average $49,000 per year to incarcerate that offender. Thus, the state has a clear fiscal interest in the success of county probation.

In this report, we review the adult probation system in California and present recommendations for improving the system’s public safety and fiscal outcomes. (Although county probation departments also supervise juvenile probationers, this report focuses on adult probation.) In preparing this report, we surveyed all county probation departments in California for information to help us better understand the various aspects of adult probation. (Please see the nearby box for a more detailed description of our survey.) In addition, we also visited a mix of small and large county probation departments representing different geographic regions of the state. During these visits, we generally met with executive probation staff, accompanied probation officers on visits to probationers, and visited other facilities where probation departments operate, such as courtrooms and sites that provide community programs. We also reviewed the literature regarding adult probation in California and nationally, and we drew upon data from numerous sources, including the State Controller’s Office, the Department of Justice, the Chief Probation Officers of California, and the Administrative Office of the Courts.

Figure 1

Summary of LAO Key Findings and Recommendations |

|

✔ Key Findings |

California probation failing to follow best practices due to limited resources. |

Current funding model provides unintended incentives to revoke probationers to state prison. |

✔ Recommendations |

Provide financial incentives to counties to reduce probation revocations to state prison by implementing best practices. |

Fund the new program from a portion of the savings to the state resulting from incarcerating fewer probationers. |

LAO Survey of Adult Probation Departments

During the summer of 2008, we surveyed all 58 county probation departments in California on the following topics: the demographics of adult probationers, staffing and workload levels, services and programs available, outcomes, and department budgets. A total of 31 counties responded to at least some of the questions on our survey, including 12 of the 15 largest counties in the state, as well as several small– and medium–sized counties. Responding counties also represented a cross–section of the state’s geographic regions, including Southern California, the Central Valley, Coastal California, the San Francisco Bay Area, and Northern California. In total, the counties responding to our survey represent about 85 percent of the total statewide population and supervise over 70 percent of all adult probationers in California. |

Background

What Is Probation?

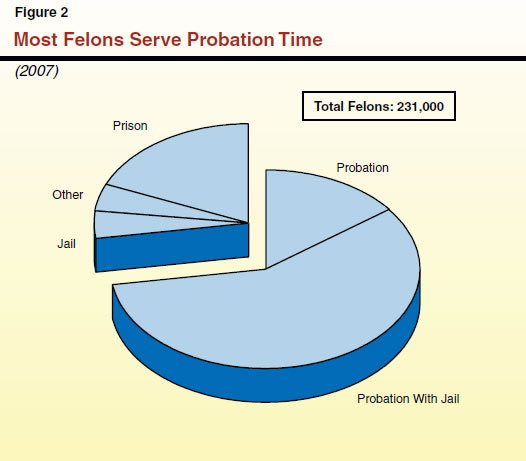

A Community Alternative to Incarceration. Probation is the supervision of criminal offenders in the community by probation officers. The decision to place an adult offender convicted of a misdemeanor or felony crime on probation is made by a trial court judge. A probation sentence is often given to a convicted offender in lieu of incarceration (such as in state prison), thus allowing the guilty offender to remain in the community under certain court–imposed conditions. In addition to community supervision, probation frequently includes a commitment to serve some time in jail, participation in treatment and rehabilitation programs, the payment of restitution to crime victims, and other conditions. Judges have significant discretion over when to sentence an offender to probation and generally make that determination based on various case factors, such as the nature of the offense and the offender’s criminal history. As shown in Figure 2, almost three–quarters of adult felon offenders convicted in California in 2007—those eligible for a sentence to state prison—were actually sentenced to probation or a combination of probation and jail.

County–Operated in California. In California, probation departments are operated by counties and staffed with county employees. Each county probation department is overseen by a chief probation officer who, based on local practice, is appointed by either the local presiding judge or the county board of supervisors. While probation departments are operated by counties, their caseloads are largely dependent on the sentencing decisions of the courts. Therefore, probation officers are frequently referred to as “officers of the court.”

Interestingly, the governance of probation varies across states. According to a nationwide survey, probation is operated at the state level rather than at the local level in 38 states. The same survey also found that probation departments (either at the state or county level) in 48 states were either funded primarily by the state or through a combination of state and local funds. In some states where probation is operated at the state level, the same agency is also responsible for parole. (In the nearby box, we discuss the differences between probation and parole in California.)

What Is the Difference Between Probation and Parole?

Both probation and parole involve the supervision of criminal offenders in the community. However, as shown in the figure below, there are some key differences between the two systems. Probation is administered by counties, includes both misdemeanant and felon offenders, and is generally considered an alternative to incarceration (especially prison). Parole, on the other hand, is administered by the state, includes only felon offenders released from state prison, and includes revocation referrals to the state Board of Parole Hearings. Unlike probation officers, parole officers do not complete presentencing reports and do not directly collect restitution and court– imposed fines.

Adult Probation and Parole—Similarities and Differences |

|

Probation |

Parole |

Level of government that administers program |

County |

State |

Type of offenders |

Misdemeanants and felons |

Felons only |

Purpose |

Alternative to incarceration or post-jail supervision |

Post-prison supervision |

Key responsibilities |

• Community supervision

• Court reports and investigations

• Responsible for restitution and fine collection

• Program referrals |

• Community supervision

• Revocation referrals to the Board of Parole Hearings

• Assistance in restitution and fine collection

• Program administration and referrals |

Number of adult offenders in 2007 |

350,000 |

122,000 |

|

Responsible for Supervision and Other Activities. Probation departments in California have several key responsibilities regarding the adult population that they supervise. These responsibilities include:

- Supervision. Probation officers are responsible for making sure that probationers are in compliance with the conditions of their probation as set by the court. These conditions generally include avoidance of criminal activity and other requirements such as drug testing, electronic monitoring, restitution payments, community service, and participation in drug treatment or domestic violence counseling. Probation officers typically check on probationers by visiting their homes or meeting with them in the probation office, as well as by reviewing drug test results and progress reports from treatment providers.

- Investigations. Probation departments provide presentencing reports to the courts. These reports usually detail the relevant history of the offender, including prior criminal arrests and convictions, family circumstances, work experience, and educational background. The court uses these reports, which frequently include a sentencing recommendation, to make sentencing decisions for convicted offenders. (Similarly, when probationers violate their probation terms, the probation officer recommends a sentencing outcome to the court, which could include continuation on probation—perhaps with stricter supervision requirements—or revocation to state prison.)

- Monetary Collections. Many convicted offenders are directed by the court to pay various fines and penalties, which are sometimes used to make direct payments of restitution to the victim of the crime. When those offenders are placed on probation, probation departments often collect those payments on behalf of the court.

- Program Referrals. When the court requires a probationer to participate in a treatment or service program, the supervising probation officer typically is responsible for referring the offender to specific program providers in the local community. These programs are usually operated by other county agencies, nonprofits, or private for–profit companies.

Who Is on Probation in California?

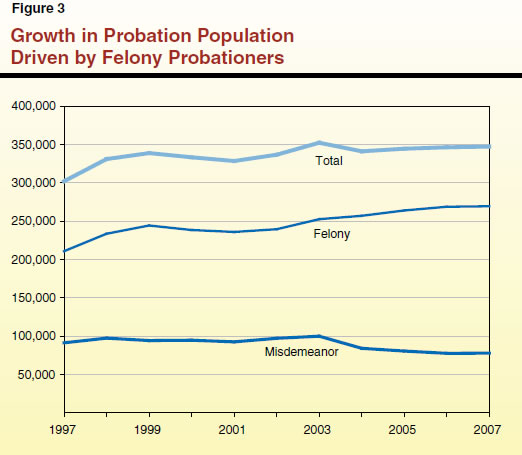

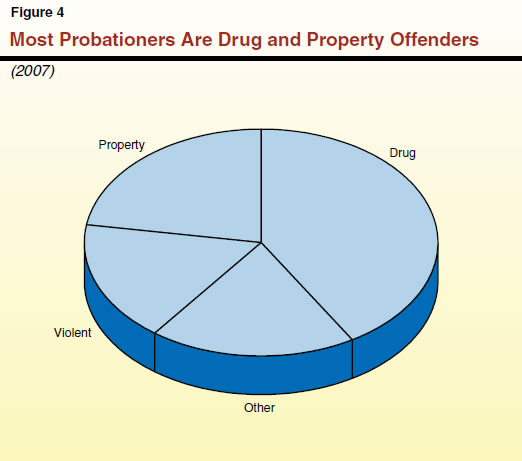

As shown in Figure 3, the total adult probation population supervised in California has increased by 15 percent over the past decade, from about 300,000 probationers in 1997 to roughly 350,000 probationers in 2007. This reflects a 15 percent decrease in misdemeanor probationers and a 28 percent increase in felony probationers. In 2007, there were about 13 probationers in California for every 1,000 adults. Over three–quarters of these offenders were placed on probation for felony offenses, while the remainder were placed on probation for misdemeanor offenses. As shown in Figure 4, counties reported that most adult probationers in 2007 were convicted for drug (41 percent) and property (23 percent) crimes.

Most adult probationers have specific case factors correlated with criminal activity, including low educational attainment, limited employment history or job skills, a history of substance abuse, mental illness, or gang involvement. For example, one national study found that about 40 percent of all adult probationers failed to finish high school or pass a high school equivalency exam. Other studies have found that about 70 percent of probationers have used illegal drugs, about one–half were under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time of their arrest, and almost 20 percent suffer from a mental illness.

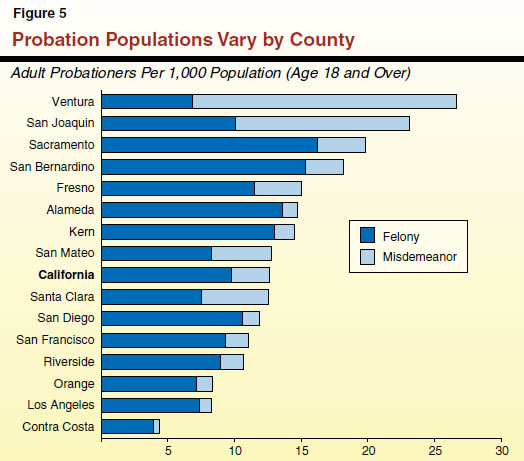

In terms of geographic location, adult probation populations vary considerably across counties. Figure 5 (see next page) shows the number of adult probationers per 1,000 adult population (age 18 and older) in the 15 largest counties in California. As indicated in the figure, Ventura County has the highest probation population rate of 27 probationers per 1,000 general population. However, San Mateo County, with a roughly similar–sized adult population, has a much lower ratio of probationers of 13 per 1,000 persons. The split within counties between felony and misdemeanant probationers also varies substantially. For example, in Ventura County, only one–quarter of probationers are felons, whereas in San Mateo County nearly two–thirds of probationers are felons.

How Are Adult Probationers Supervised?

Adult Probation Officers Are Small Share of Total Probation Staff. Currently, about 20,000 individuals work at county probation departments in California, including staff involved in the supervision of both adult and juvenile offenders. Of this total, almost half are sworn probation officers, while the other half consists of non–sworn employees (such as administrative, clerical, or program staff). We estimate that there are about 3,000 sworn probation officers who supervise adult probationers—only about 30 percent of the state’s sworn probation officers. The remaining officers supervise juvenile probationers or work at juvenile detention facilities and camps, which are also operated by county probation departments.

Under existing state law, all probation officers are required to complete training as prescribed by the Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training. Otherwise, state law provides counties wide discretion over the qualifications and training requirements for its probation officers. Based on the responses to our probation survey, the annual salary of probation officers ranges from about $45,000 to $67,000. (By way of comparison, state parole agents earn $60,000 to $110,000 in salary annually.) Counties responding to our survey reported an average vacancy rate in adult probation officer positions of about 5 percent.

Three Types of Supervision Caseloads. Not all adult probationers in California are supervised in the same manner, even within the same county. Since probationers differ in their criminal history, risk to public safety, and need for treatment and services, probation departments typically assign probationers to three different types of caseloads based on their profile and needs:

- Regular Caseloads. About 20 percent of all adult probationers are assigned to regular caseloads. These tend to be offenders whose criminal history or risk to reoffend is serious enough that probation departments find it necessary to supervise them on a regular basis. Counties report that probation officers make contact with probationers on regular caseloads about once or twice a month. Most of these contacts are face–to–face meetings at the local probation office or at the probationer’s home. Our survey found that these caseloads typically average between about 100 and 200 probationers per officer.

- Specialized Caseloads. About 30 percent of probationers are placed on different specialized caseloads based on such factors as their criminal history or treatment needs. For example, many counties have different specialized caseloads for offenders convicted of domestic violence, sex crimes, driving under the influence of alcohol, or drug–related crimes. Counties report that probation officers often supervise offenders on specialized caseloads more closely than those on regular caseloads, which could range from two to four visits per month depending on the type of specialized caseload. Our survey found that specialized caseloads typically average about 70 probationers per officer.

- Banked Caseloads. About half of all probationers are placed on banked caseloads. These are offenders who are deemed by the probation department to be of low risk to public safety and, therefore, require less supervision than those on regular or specialized caseloads. For example, almost two–thirds of all misdemeanor probationers are on banked caseloads. Probation officers generally have infrequent contacts with probationers on banked caseloads—usually no more than once every few months. These contacts generally do not involve face–to–face meetings, but rather are done in writing, over the phone, or at an electronic kiosk stationed at a probation office. Banked caseloads typically average several hundred probationers per officer.

What Programs and Services Are Provided to Probationers?

Broad Range of Programs and Services. As we noted earlier, trial court judges make the decision as to whether to place a criminal offender on probation. As a condition of probation, the courts often require probationers to participate in certain programs for rehabilitative purposes. For example, probationers convicted of drug possession will often be required to enroll in drug counseling or treatment. In addition, probation officers sometimes voluntarily refer probationers to programs not specifically required by the court. The five most commonly reported programs in our survey were (1) anger management, (2) programs to reduce domestic violence, (3) sex offender treatment, (4) mental health treatment, and (5) substance abuse treatment. Some departments also refer probationers to educational and vocational training programs, family and parenting counseling, and employment assistance programs.

Offenders Help Pay for Services. In many cases, we found that probationers are responsible for making payments to help offset the cost of the programs and services they receive. For example, over three–quarters of counties responded in our survey that offenders typically help pay for anger management, domestic violence, and sex offender treatment programs. Several of the probation officials we met with indicated that having probationers help pay for their services promoted accountability and a sense of self–investment in the programs. In addition, these officials cited the lack of county financial resources as another reason for implementing a fee–for–service model. In order to ensure that income level is not a barrier to having access to services, most programs utilize a “sliding scale” fee structure based on an offender’s ability to pay, with low–income offenders paying little or no fee. Although most programs provided to probationers are supported with fee revenues, some programs are also financed with public funds. For example, state and local sources provide counties with most of the funding for mental health and substance abuse treatment for probationers.

How Is Probation Funded?

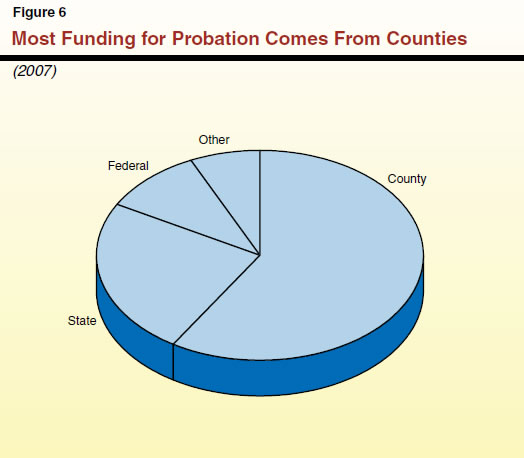

Counties Are Primary Source of Funding for Probation. In 2007, county probation departments spent a total of about $2 billion for adult and juvenile supervision as well as juvenile detention facilities. (Data are not available on what share of this amount was spent specifically on adult probation.) As shown in Figure 6, our survey found that on average probation departments received about two–thirds of their total funding from counties. In comparison, departments received about one–fourth of their funding from the state. The remaining funds came from the federal government and from other sources, such as fees charged to probationers to help support supervision and administrative costs.

Various State and Federal Funding Sources. According to our survey, state funding sources for probation include Proposition 172 (a half–cent statewide sales tax that supports local public safety departments) and three public safety local assistance programs targeted at juveniles—Juvenile Probation and Camps Funding, Youthful Offender Block Grant, and the Juvenile Justice Crime Prevention Act. While the Legislature provided $10 million in one–time grants in 2007–08 to improve probation supervision and services for at–risk young adults of ages 18 to 25, the state currently provides no ongoing funding specifically for adult probation. (The nearby boxes provide a chronology of state funding for probation as well as additional information on the one–time grants provided for adult probation in 2007–08.) The federal funding source identified most frequently by survey respondents was Social Security Title IV–E funding, which reimburses counties for foster care and child welfare costs. Figure 7 lists the primary state and federal funding sources available to probation departments in California.

Figure 7

Primary State and Federal Funding Sources for

Probation in California |

|

State Funding |

Proposition 172 (Local Public Safety Fund) |

Juvenile Probation and Camps Funding |

Juvenile Justice Crime Prevention Act |

Youthful Offender Block Grant |

Proposition 36 (Substance Abuse Crime Prevention Act) |

Proposition 63 (Mental Health Services Act) |

Federal Funding |

Title IV-E (Social Security) |

Juvenile Accountability Block Grants |

Chronology of State Funding for Probation in California

1903 Legislature enacts the state’s first probation laws.

1965 Legislature establishes the Probation Subsidy Act, which provided counties with up to $4,000 for each adult or juvenile offender sentenced to probation instead of prison.

1978 Legislature replaces the Probation Subsidy Act with the County Justice System Subvention Program, which funded a variety of local criminal justice programs, including about 7.5 percent of statewide probation expenditures.

1991 The County Justice System Subvention Program is eliminated as part of the 1991–92 realignment of health and social services programs, with the revenues transferred to counties, along with the discretion to spend the funds on various juvenile justice, health, mental health, and social services purposes.

1993 Legislature proposes and the voters approve Proposition 172, a half–cent state sales tax to fund local public safety departments. Counties are able, but not obligated, to use this ongoing source of funds for probation.

2000 Legislature establishes ongoing grant program for counties to develop juvenile crime prevention programs, with probation as the lead agency involved.

2005 Legislature begins to backfill counties’ loss of federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families funds for juvenile probation.

2007 Legislature establishes the ongoing Youthful Offender Block Grant program to support juvenile offenders at the local level.

2007 Legislature provided $10 million in one–time grants to improve probation supervision and services for at–risk young adults of ages 18 to 25. |

Adult Probation Pilot Programs Funded in 2007–08

The 2007–08 Budget Act included $10 million for two pilot programs aimed at improving probation supervision and services for young adults of ages 18 to 25. The Corrections Standards Authority (CSA) is responsible for administering the funding, which is available for expenditure over a three–year period, and for ensuring that the recipients provide an evaluation report of the pilot projects upon their completion.

The first pilot program provided $5 million to the Alameda County probation department to de–escalate community conflicts among the young–adult probation population, as well as to provide employment development and education programs to these probationers. According to CSA, Alameda County is in the process of implementing this program (formally known as Reconstructing One’s Character through Knowledge, or ROCK). The program will utilize an assessment tool to determine risk and needs, provide motivational interviewing, and offer cognitive behavioral group therapy.

The second pilot program provided $5 million to the Los Angeles County probation department to support young adult probationers in known gang “hotspots.” According to CSA, the department is currently implementing a day reporting center for these particular probationers. The proposed center will be used to assess young males identified as high–risk and provide them intervention services from a multidisciplinary team of education and employment counselors and substance abuse treatment providers. |

Model of Best Probation Practices

As part of our examination of the state’s adult probation system, we reviewed national research on the effectiveness of probation in improving public safety. The research identified a set of best practices for probation. These practices are (1) using risk and needs assessments, (2) referring probationers to treatment programs, (3) maintaining manageable probation officer caseloads, (4) using graduated sanctions for probation violators, and (5) conducting periodic program reviews and evaluations. According to the research, these practices have been found to result in more effective supervision, reduced recidivism, better prioritization of limited supervision resources, and reduced incarceration costs. We discuss each of the five best practices in more detail below.

Use of Risk and Needs Assessments

Corrections research supports the use of risk and needs assessments of offenders when they are first placed on probation and periodically thereafter. These assessments are formal evaluations—usually relying on data from case file reviews, interviews, and questionnaires—of the offender’s criminal history and causes of criminal activity. Risk assessments provide a consistent and accurate approach to distinguishing which offenders pose a higher risk to community safety and, therefore, should receive closer supervision if placed in the community. Given limited resources, the risk and needs assessments also assist probation departments in determining which offenders to prioritize for intensive rehabilitation services.

Referrals to Community–Based Programs to Reduce Recidivism

The national research on community supervision finds that offenders are more likely to be successful while on probation if they are provided effective treatment and assistance programs that assessments show they need, such as drug treatment, mental health counseling, employment assistance, and anger management. In addition, the research finds that such programs are most effective if they are provided under a “cognitive–behavioral” approach. Cognitive–behavioral therapy generally aims to address not only the specific problems of the offender (such as drug use or unemployment), but also the patterns of thinking and decision making that lead to his or her criminal behavior. A review of 25 studies of cognitive–behavioral therapy for adults in prison or under community supervision found that these programs reduce recidivism rates by over 6 percent, yielding net savings to crime victims and taxpayers of over $10,000 per participating offender.

Manageable Supervision Caseloads

Currently, there is no accepted national standard for how many probationers should be on a probation officer’s caseload. However, the literature on probation generally finds that increased supervision levels—achieved by creating lower probation officer caseloads—can be a key to effective probation. Lower caseloads allow probation officers to have more contacts with their offenders (such as in the form of unannounced home visits and more frequent drug testing), thus making it easier for officers to quickly identify probation violations. Similarly, frequent probation contacts can also act as a deterrent for probationers because of the increased risk of getting caught in new criminal activities or violation of the conditions of their probation. The research does indicate, however, that intensive supervision is generally only effective at reducing recidivism when coupled with treatment–oriented programs. The American Probation and Parole Association (APPA) suggests a caseload of 50 probationers per probation officer for general (non–intensive) supervision of moderate and high risk offenders, and caseloads of 20 to 1 for intensive supervision.

System of Graduated Sanctions

Many probationers reoffend, often repeatedly, and for a variety of reasons. According to the literature, one of the key strategies to effectively intervene and interrupt the cycle of reoffending is to establish a system of graduated sanctions. Such a system involves the use of punishments that are scaled to match the number and severity of the violations. Typically, this means imposing less severe sanctions (such as community service, fines, or increased drug testing) for first–time and less serious violations, while providing increasingly stricter sanctions (such as day reporting centers, intensive supervision, flash incarceration, and revocation to prison) for subsequent and more serious violations.

The research also suggests that it is important that such sanctions be applied to probationers swiftly, consistently, and with certainty. A well–implemented system of graduated sanctions acts as a deterrent for some offenders and interrupts the cycle of reoffending for others, thereby improving public safety. Importantly, because many offenders receive a community–based sanction instead of being revoked to prison or jail, this approach often provides a much more cost–effective option than incarceration.

Program Reviews and Evaluations

As discussed above, the research finds that implementing certain programs and practices have been found to result in better probation outcomes and reduced recidivism. This suggests that duplicating similar programs and practices should result in similar outcomes. However, research suggests it is important not only to implement the right types of programs and practices, but to implement them well. For example, it is often critical to ensure that new efforts are implemented with qualified and well–trained staff, and that programs are delivered to the types of offenders for which they were designed. For this reason, several states (such as Oregon) utilize program assessment tools to measure program fidelity, a measurement of how well the program or practice is implemented. As a result, these states are better able to ensure that state– and county–funded programs for probationers will be effective.

In addition to measuring program fidelity, it is important to collect data on probationer outcomes that can indicate what strategies and programs are most effective at successfully rehabilitating offenders. For example, if a substantial number of probationers enrolled in a particular program end up violating their probation terms, this could indicate that the program is not effective. More importantly, program outcome data will enable probation departments and policy makers to replace ineffective programs, improve underperforming programs, and expand successful programs. Data on program outcomes can also help determine which programs are most cost–effective in reducing recidivism and thus assist policy makers in the allocation of limited financial resources for probation.

Opportunities Being Lost to Improve Public Safety and Reduce State Costs

Based on our review of actual probation practices, we find that California counties do not regularly follow the best practices identified in the research. In addition, we find that the absence of a stable funding source for adult probation, and the lack of fiscal incentives to promote the best outcomes for public safety or efficiency, constitute major barriers to the promotion of successful probation practices. These findings mean that probation in California is not as successful as it could be, resulting in a lost opportunity to improve public safety as well as to reduce high state corrections costs.

California Probation Often Fails to Follow Model of Best Practices

Based on the responses to our survey, reviews of other surveys and literature about California probation, site visits to several county probation departments, and discussions with probation officials, we find that many probation departments in California do not follow all of the best probation practices identified in research. Figure 8 summarizes our major findings, which we discuss in detail below.

Figure 8

LAO Key Findings:

California Probation Failing to Follow Best Practices |

|

• Risk and needs assessments of probationers not being used consistently. |

• Effective programs and services not always available for probationers. |

• Probation experiencing high supervision caseloads. |

• Graduated sanctions rarely utilized. |

• Program evaluations not usually conducted. |

Risk and Needs Assessments Not Being Used Consistently. We found that roughly 80 percent of the counties that responded to our survey use a risk and needs assessment tool for at least part of their probation population. While some of the assessments used are designed for the general probation population, other assessments are designed for specific offender groups (such as probationers convicted of sex crimes, domestic violence, or drug crimes). Based on our review of the literature, most of the counties are using assessment tools that are generally considered to be valid and are used in other states.

However, six counties—about one out of every five responding—reported they do not currently use an assessment tool for any of their probationers. (Three of the six counties did report that they are in process of implementing such an assessment.) Other counties only used assessments on certain types of offenders (such as sex offenders) or did not report updating the assessment periodically. In addition, a few counties reported using assessment tools that they had developed internally over the years, but that had not been validated as accurate.

Based on our discussions with county officials, when risk assessments are used, it is primarily to make decisions about the most appropriate supervision level. Risk assessments do not appear to be widely used by probation officers in making sentencing recommendations, nor does it appear that assessments are widely used by probation officers to prioritize which probationers are placed in more intensive rehabilitation programs.

Effective Programs and Services Not Always Available for Probationers. We found that rehabilitation programs are not available in all California counties, nor are they available to many probationers who might benefit from them. Substance abuse treatment was the only type of program that was reported as being available for offenders in all of the counties that responded to our survey. While certain other programs (related to anger management, domestic violence, mental illness, and sex offending) were reported as being available for adult probationers in a large majority of counties, some programs (such as education and vocational training and housing assistance) are only available to probationers in a few counties. Moreover, our discussions with counties suggest that even when such programs are offered for probationers, they frequently suffer from having limited capacity, few available locations, and questionable quality, especially programs that do not adhere to an evidence–based model.

Probation Experiencing High Supervision Caseloads. According to various probation surveys, probation caseloads in California are significantly higher than those suggested by APPA—50 probationers per officer for regular caseloads and 20 probationers per officer for specialized caseloads. According to our survey results, the average caseload for offenders under regular caseload supervision ranges from 100 to 200 probationers per officer, with several counties reporting caseloads in excess of 200 probationers per officer. Although counties reported smaller caseloads for probationers on specialized caseloads, many of these caseloads exceed an average of 70 probationers per officer. According to county probation officials, high caseload ratios are one of their biggest concerns. Constrained resources limit their ability to hire the staff necessary to reduce caseloads to a level more in line with best practices.

Graduated Sanctions Rarely Utilized. Our conversations with probation officers and administrators indicated that they do not regularly employ an array of community sanctions for probation violators, as recommended in the literature. In part, this is because probation officers often have relatively few sanction options (such as day reporting centers) available in their communities to use in lieu of incarceration, even when community–based punishments would be more appropriate. When community–based options are employed, they are typically limited to verbal warnings, modest increases in supervision contacts and drug testing, and referral to a treatment program.

Probation officials indicated that they considered the available list of options as being too narrow to effectively respond to the range of violations and types of offenders they supervise. As a result, probationers are sometimes continued on probation with few sanctions, and then, after repeated violations, end up being sent to state prison.

Program Evaluations Not Usually Conducted. All of the probation departments that we visited expressed a willingness to use evidence–based programs and treatment services for probationers. However, some departments were concerned about the fidelity of those programs to the original model program that was proven to be cost–effective. In other words, probation officials often question whether the programs are consistently delivered effectively with well–trained staff and in accordance to evidence–based principles. Probation officials also noted that they generally exercise little direct oversight over treatment programs operated by public or private agencies. In fact, only a few counties regularly reviewed the fidelity of programs.

In addition, our survey found that a majority of probation departments do not track the type of performance or outcome data that is necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of probation activities and programs. For example, many probation departments responding to our survey were unable to identify how many probationers participate in rehabilitation programs. Only one probation department was able to report on the number of probationers that had completed programs, and only three departments were able to provide information on another key outcome, probationer employment. Moreover, less than half of the probation departments that responded to our survey were able to report the number of probation violations that had occurred in a given year. Even fewer departments were able to provide more detailed information about these violations, such as the number that resulted in a commitment to state prison. Although many departments indicated that they would like to be able to track the above data, they currently lack the information technology systems that would be needed to do so.

Funding Constraints Limit Effectiveness of Adult Probation

Relatively Few Resources Devoted to Adult Probation. The probation department representatives with whom we spoke seemed aware of their agencies’ shortcomings in following the best practices for their field. Most indicated that the main reason for not fully implementing these practices is limited funding.

Notably, our survey found that, on average, probation departments spend about $1,250 per year per adult probationer. (This estimate includes all probation cases, including banked cases.) In contrast, we estimate that probation departments spend about $6,300 per juvenile probationer for community supervision, while the state spends approximately $4,500 annually to supervise an adult parolee. Although these differences in spending could be related to differences in personnel costs or other factors unrelated to the level of service provided, it would appear that, compared to other community supervision systems, adult probation receives a relatively lower level of funding.

Current Funding Model Provides Incentive to Revoke Violators to Prison

Probation departments clearly have an interest in the success of adult probationers because of their responsibility to ensure public safety in the community. However, the current funding structure for adult probation may inadvertently provide a fiscal disincentive for counties to successfully retain adult felon offenders on probation where appropriate. When a probationer commits a violation or new crime, probation officers must decide whether to recommend to the court that the offender be retained on probation or sent to state prison. Although we are advised that probation officers frequently recommend retention, they sometimes recommend state prison for those offenders who commit repeated violations.

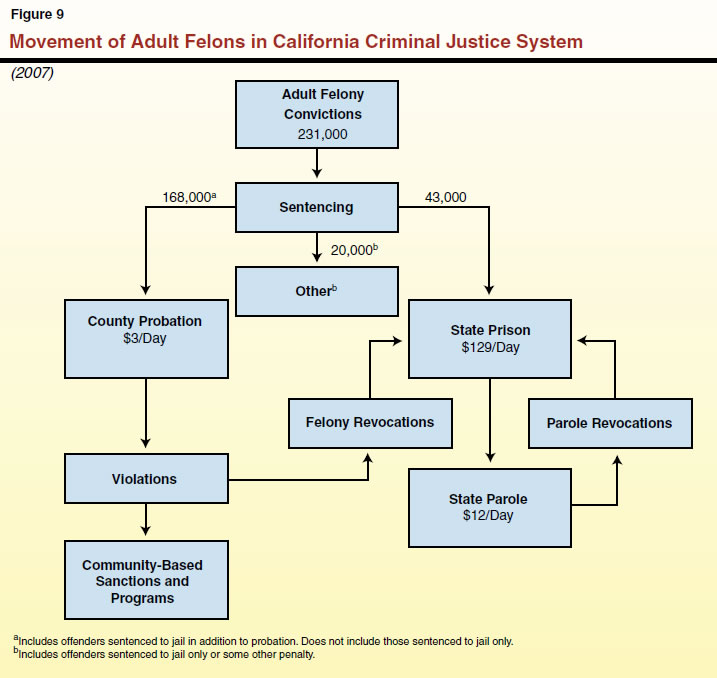

Probation department officials indicate that this is primarily because they often lack sufficient resources to properly supervise and treat these repeat offenders. In contrast, there is comparatively little cost to the county for undertaking the process needed to send the offender to state prison. In addition, sending violators to state prison allows probation departments to prioritize their limited resources for supervising those offenders who are more amenable to supervision and treatment. The consequence of these fiscal incentives is that some offenders who could be safely and successfully supervised at the local level, if more resources were available for this purpose, are instead sent to state prison at an even greater cost to taxpayers—about $49,000 per year—plus additional parole costs. Figure 9 illustrates the movement of adult felons in the California criminal justice system.

The Bottom Line: Many Probation Failures and Significant State Costs

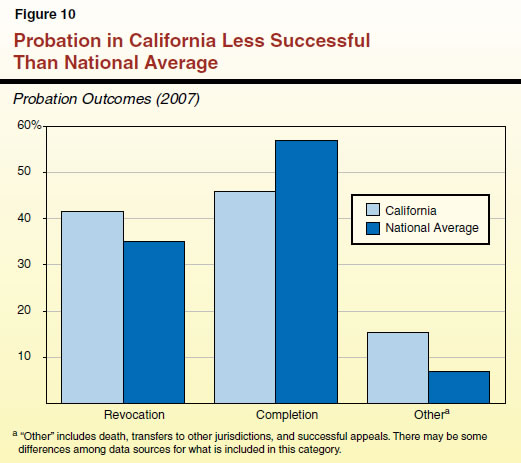

Almost Half of All Probation Terms End in Revocation. In 2007, about 40 percent (or about 80,000) of adult probationers removed from probation had their probation term revoked, usually resulting in a jail term, the imposition of additional probation time or conditions, or a sentence to state prison. Less than half ended with the successful completion of probation.

Probationers in California Less Successful Than Other States. Research indicates that California probation terms are more likely to end in revocation and are less likely to end with the successful completion of probation when compared to the nation as a whole. For example, the rate of successful completion of probation is 10 percent higher nationally than for California. Figure 10 compares revocation and completion rates for California to national averages.

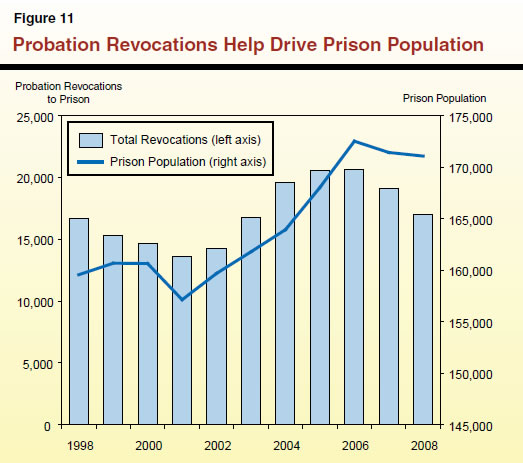

Significant Annual State Expenditures to Incarcerate Probation Failures. According to records kept by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, an average of about 19,000 probation violators are sent to state prison each year. These probationers make up approximately 40 percent of all new prison admissions from the courts each year. Figure 11 shows the number of probation violators sent to prison annually and the change in the total prison population over the past decade. As shown in the figure, changes in the number of probation failures sent to the state and the state prison population mirrored each other closely over the past ten years. We estimate that the state spends about a billion dollars annually to incarcerate, supervise, and treat offenders who first enter the prison system as probation failures.

LAO Recommendation: Establish a Fiscal Incentive Program for Probation

In this report, we have reviewed the adult probation system in California and identified a number of issues that limit its current effectiveness. Based on our review and these findings, we have concluded that there are opportunities to both improve public safety and reduce state costs by better aligning the county probation and state correctional systems. As a result, we recommend that the Legislature establish a new program that would provide a fiscal incentive for county probation departments to reduce the number of probation violators entering state prison. We believe that such a program would provide a stable funding stream for adult probation departments, improve public safety, and reduce state prison overcrowding and operating costs. Although participation in this program would be voluntary on the part of county probation departments, we believe that most departments would choose to participate given the potential financial benefits. A program very similar to our proposal was recently implemented in Arizona. In addition, SB 678 (Leno and Benoit), which is pending in the Legislature, includes many aspects of our proposal. We discuss the structure, keys to effective implementation, and benefits of our proposal below.

How Would the Program Work?

Use State Prison Savings to Create Incentives for Successful Probation. Under the new program we propose, which we call the California Adult Probation Accountability System (CAPAS), county probation departments that demonstrate a reduction in the number of probation violators entering state prison each year would receive a set payment from the state. The state payments would be funded with the savings achieved from incarcerating fewer probation violators in prison. Probation departments would be required to reinvest these funds to alleviate some of the problems we identified with the current system. For example, probation departments could use the funds to reduce probation officer caseloads or to expand the availability of rehabilitation and treatment programs. This, in turn, would help to reduce crime, thereby further reducing the number of probationers sent to prison. (As we discuss in the nearby box, the state administered a program about 40 years ago—known as the California Probation Subsidy Act—that was similar to our proposed CAPAS program.)

California Probation Subsidy Act of 1965

In 1965, the Legislature established the California Probation Subsidy Act, which required the state to pay counties $4,000—the average cost at the time to incarcerate a juvenile or adult offender in a state institution—for every juvenile and adult diverted from the state and kept at the local level. Counties were required to use the funds to develop specialized and reduced probation caseloads. The primary goal of the program was to reduce admissions to the state in order to reduce overcrowding in state correctional facilities. In addition, the program was intended to reduce disparities in state sentencing decisions across counties. The underlying concern was that taxpayers living in counties that sent fewer offenders to the state were effectively subsidizing the tougher sentencing practices of counties that sent disproportionately more offenders to state institutions.

Probation Subsidy Act Was Relatively Successful. Our review of the research indicates that the Probation Subsidy Act was successful at achieving its primary goal of reducing adult and juvenile admissions to state institutions. Estimates were that juvenile admissions declined by about 40 percent and that adult admissions declined by about 20 percent five years after the program was implemented.

Some Concerns Raised About the Probation Subsidy Act. Although the program was successful at achieving its primary mission, some state and local officials had concerns about the program. For example, because the $4,000 payment from the state was not adjusted each year for inflation, counties voiced concerns that subsidies had become insufficient to keep up with the costs of supervising offenders at the local level. In addition, funding was not available

to subsidize sheriffs even though the program diverted some offenders from prison to jail. Law enforcement officials contended that the program increased crime rates because more criminal offenders were being kept in the community rather than sent to state prison. According to the research, however, the program had a minimal impact on crime rates. While crime rates began rising in the 1960s, this trend actually preceded implementation of the Probation Subsidy Act.

CAPAS Could Address Shortcomings of the Probation Subsidy Act. We believe that our proposed California Adult Probation Accountability System (CAPAS) program could be designed to address some of the shortcomings associated with the Probation Subsidy Act. For example, potential negative impacts on county budgets could be significantly reduced by adjusting the per probationer payment each year in line with state prison costs, as well as by providing a share of the payment to other county agencies affected by the program, such as sheriff’s departments. Under our proposed approach, the program would generate substantial net savings annually to the state even if the Legislature provided significant subsidies to counties. In addition, if properly structured, the CAPAS program could be more effective at reducing recidivism than the Probation Subsidy Act. This is because much more research is now available on best probation practices that could be incorporated into the program. Under our proposal, counties would be permitted to use CAPAS funds on any of these best practices, not just on reducing caseload sizes, the sole focus of the Probation Subsidy Act. Finally, unlike the prior probation subsidies, our proposed program is designed to reduce probation revocations and increase public safety, and not just to reduce prison admissions. |

The annual payment that each county probation department would receive under the program would depend on its success in reducing the number of probation violators entering prison and the savings the state would realize from the diversion of probation violators. In order to qualify for a CAPAS payment, a county probation department would have to demonstrate that fewer of its probation violators were entering state prison than historically was the case.

A “baseline” probation revocation rate would be calculated to reflect the actual number of probation revocations entering prison from each county before the CAPAS program began divided by that county’s adult felony probation population. We suggest calculating a baseline revocation rate on at least three consecutive years of data to account for any unusual circumstances that may have occurred in any particular year. The appendix shows baseline revocation rates for each county based on data from 2005 through 2007.

This baseline rate would then be compared to the rate at which probationers subsequently were entering prison from that county each year. Using rates in the calculations (rather than the difference in the number of probationers sent to state prison from one year to the next) would take into account any future changes in each county’s probation population. For example, changes in population or crime rates may on the natural affect the number of probationers that a county would send to state prison over time. In addition, using rates would prevent counties from attempting to “game” the program by placing fewer offenders on probation as a strategy for decreasing revocations to state prison. A rate therefore provides a better way of comparing the actual performance of probation over time. The more that a probation department decreased its rate of commitments of probation violators to prison, the greater its future CAPAS payments would be.

In the nearby box, we provide a more detailed example of how these allocations could be structured. Under our proposed approach, payments to probation departments would equal a portion of the amount the state saved for each probation violator diverted from state prison. As shown in Figure 12, the state eventually spends about $50,000 for each probationer sent to prison and subsequently placed on parole. (This number represents the marginal additional cost to the state for each additional inmate and parolee.) Thus, $50,000 also represents the savings that would eventually accrue to the state each time one less probationer is placed in state custody due to a probation revocation.

Figure 12

State Spends Roughly $50,000 for

Each Probationer Sent to Prison |

|

Average

Length of Time |

Annual

Marginal Cost |

Total Cost |

Prison |

17 months |

$23,000 |

$32,500 |

Parole |

2.5 years |

2,500 |

6,000 |

Reincarceration for

parole violations |

6 monthsa |

23,000 |

11,500 |

Totals |

5 years |

— |

$50,000 |

|

a Estimated costs for parolees returned through administrative revocation process, as well as those convicted in courts for new crimes. |

We suggest the state provide a reasonable share of these savings to probation departments. In concept, the probation department’s share of funding should be enough for them to (1) provide supervision and treatment (including, as necessary, incarceration at times in county jail) for the additional offenders who would remain in county custody and (2) improve their supervision and services for their overall adult probation operations, such as by reducing the average caseloads for probation officers. Currently, the program in Arizona provides a payment equal to 40 percent of estimated state savings. If California were to provide an equivalent share of its savings, for the purposes discussed above, this would be $20,000 for each diverted probationer. This is significantly higher than the average counties currently spend on each adult probationer ($1,250). We estimate that this amount of funding could provide more intensive supervision of the probationer at a more manageable caseload size ($4,000), a typical treatment program such as substance abuse treatment ($6,000), while leaving the remainder of the payment ($10,000) for probation to increase its supervision and services of other probationers or help fund the implementation of new practices and programs, such as risk assessments. Such a payment would still leave the state with savings of about $30,000 per offender. Since these savings would accrue over a period of several years, it may make sense to spread out the payments to counties over two or more years as well.

Program Savings Could Be Significant. The net savings that the state could achieve under our proposed CAPAS program are unknown and would depend on how many fewer probationers were revoked and sent to state prison each year, as well as the level of the savings shared under the program with county probation departments. If, for example, the number of probation violators sent to state prison was reduced by 10 percent, the inmate population would be reduced by about 2,500 inmates, and total state corrections operating costs would be reduced by about $100 million annually when fully implemented. If, as we have suggested, 40 percent of these savings went to probation departments, they would receive $40 million annually to improve probation operations, and the state would achieve $60 million in net savings.

Other Ways to Structure the Program. The CAPAS program could be structured differently than we have outlined above. For example, a higher per probationer payment, or a certain percentage of the overall state savings, could be provided to probation departments in counties that currently send relatively few probation violators to prison. Such an approach would reward departments that are already doing a better job at managing their adult probation caseloads and holding down state correctional costs. This approach would recognize that such departments likely could not make as great a reduction—or any reduction—in their probation revocations to state prison as departments in other counties that much more frequently commit such offenders to state prisons.

The CAPAS payments to probation departments could also be tied to the number of new crimes committed by probationers. For example, Arizona’s new probation subsidy program ties half of the funding that goes to counties to reductions in overall probation revocations and the other half to the number of new felony offenses committed by probationers. Counties showing improvements in public safety through a reduction in crime by probationers could receive additional funding. While we recommend that a similar approach be considered by the Legislature, data limitations may make it difficult to collect this information consistently in the short term.

Calculating a Probation Department’s CAPAS Payment—An Example

In the figure below, we provide a hypothetical example of how the state could calculate a probation department’s California Adult Probation Accountability System (CAPAS) payment.

|

|

|

Calculation of the Baseline Rate of a County |

County A |

Average probation revocations sent to prison (2006 to 2008) |

1,000 |

Average adult felony probation population (2006 to 2008) |

10,000 |

Baseline Rate (Revocations Per 100 Adult Felon

Probationers) |

10.0% |

Calculation of the Reduction in Revocations for 2009

Achieved by That County |

Adult felon probation population in 2009 |

10,500 |

Baseline Rate |

10.0% |

Expected revocations to prison in 2009 |

1,050 |

Actual revocations to prison in 2009 |

900 |

Reduction in revocations to prison in 2009 |

150 |

Calculation of the Total Payment to a County |

|

Reduction in revocations to prison in 2009 |

150 |

Per probationer payment amount |

$20,000a |

Total Probation Department Payment |

$3,000,000 |

Probation payment in 2010-11 |

$1,500,000b |

Probation payment in 2011-12 |

$1,500,000b |

|

a In this example, we assume a payment equivalent to 40 percent of total state corrections savings, based on current costs. Actual per probationer payment amount would be adjusted annually. |

b In this example, we assume that the total probation payment is spread out over two years. Payments begin starting in the first complete fiscal year after the end of the last calendar year for which the

reduction in revocations to prison is calculated. |

|

What Are the Keys to Successful Implementation?

In order to ensure that the new CAPAS program is implemented successfully and effectively, it should be designed and administered in a manner that facilitates accountability and enables probation departments to improve their programs and services. Specifically, we believe it is important to (1) ensure effective administration and oversight, (2) limit the use of CAPAS funding to the implementation of best probation practices, (3) utilize available federal funds to allow counties to make initial improvements to their programs, and (4) provide some assurance to probation departments regarding the ongoing availability of CAPAS funding.

Ensure Effective Administration and Oversight. Under our proposal, the Corrections Standards Authority (CSA) would administer the CAPAS program. This arrangement would build upon CSA’s experience in administering several local public safety grant programs and providing state oversight of local detention facilities. The CSA would be responsible for (1) compiling data on the number of probation violators entering state prison from each county, (2) calculating the appropriate CAPAS payments (based on legislatively determined formulas), and (3) providing general state oversight regarding the expenditure of these funds by probation departments. In order to assist CSA in providing program oversight, we propose requiring each probation department that receives CAPAS funds to submit a year–end report to CSA on how the funds were spent. The report should also include data on year–to–year changes in probation outcomes (such as the number of probationers arrested for new crimes, program completion rates, and the percentage of probationers able to find employment). In addition, probation departments should be required to report on their base funding, staffing, and caseload levels to give the Legislature a more complete understanding of all the resources available for probation. The CSA would be required to compile these individual reports into a single statewide report for the Legislature. Finally, the CSA would be responsible for ensuring that the rules on the use of funding are being followed and that any funds spent inappropriately were returned to the state.

Restrict Funding to Best Practices. As discussed earlier in this report, most county probation departments do not follow all of the best practices identified in the research, primarily because of the limited resources dedicated specifically to adult probation. In order to help address this problem, we believe that probation departments should be required to use most of the CAPAS payments they receive to implement and expand their use of best practices in adult probation. These practices include using risk assessments, providing treatment programs and services, reducing caseloads, utilizing graduated sanctions, and evaluating the effectiveness of programs. Under our proposal, probation departments would have the flexibility to allocate their CAPAS funding towards the mix of best practices that would best meet their local needs. Since the proposed program could impact other county agencies, such as sheriffs and county drug and alcohol and mental health departments, we also suggest that a portion of funds be restricted to help offset increased costs to these other affected county agencies.

Utilize New Federal Funds to Get the Program Started. The proposed CAPAS program would likely benefit from an initial upfront investment for probation departments to begin improving their programs and practices to reduce revocations. The federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, passed in February 2009, provides California with $136 million in Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grants (Byrne/JAG), which can be used to support local public safety programs. These funds will be administered and distributed to eligible sub–grantees by the California Emergency Management Agency (CalEMA). The Legislature could direct CalEMA to use these funds for an upfront investment in the CAPAS program, in order to help county probation departments begin improving their overall success at reducing failures on probation.

Assure Probation Departments That Ongoing CAPAS Funding Will Be Provided. We expect that a key concern of probation departments with the proposed program is whether they would in fact receive CAPAS payments if they reduce the number of probation failures sent to state prison, especially in future years when the state is faced with budget shortfalls. While these concerns are reasonable, we think the fiscal benefit to the state will be a key to keeping the program intact. In other words, as long as probation departments can continue to demonstrate the effectiveness of the program in reducing probation violations and prison admissions, there will be a clear and compelling reason for the state to continue to support the program. In fact, under such circumstances, it would be demonstrably more costly for the state to discontinue a successful CAPAS program than to continue it because of the increased correctional system costs that would result from such an action.

Benefits of Proposed CAPAS Program

Our proposal for a program to provide a fiscal incentive for probation departments to reduce the number of probation violators entering state prison would address some of the shortcomings with the state’s current probation system. Specifically, our analysis indicates that such a program could achieve the following benefits:

- Provide Additional Resources to Improve Adult Probation. Under the CAPAS program, county probation departments would use the additional funds to improve their core operations, such as by implementing risk assessments and graduated sanctions. In addition, probation departments would be in a better position to keep those probation violators who pose the lowest risk to public safety on probation and provide them with more intensive programs. According to the research, this should result in fewer reoffenses, more successful probation completions, and fewer probationers revoked to prison for new offenses, all of which could help to improve public safety in the community.

- Create Incentives for Success. The CAPAS program would address what is currently a disincentive for probation departments to keep lower level probation violators in the community. As we discussed above, these probation violators are sent to state prison—often after multiple violations—in part because probation departments have relatively few resources and alternatives available. The CAPAS program provides a fiscal incentive for probation departments to better supervise and treat probationers by linking successful outcomes with additional resources.

- Prioritize Limited State Prison Space for Most Serious and Violent Offenders. Under the CAPAS program, counties would have expanded capacity to supervise and treat lower level offenders who would otherwise have gone to prison. Currently, about 70 percent of adult offenders are sent to prison for non–violent crimes (though many may have committed prior violent offenses). Thus, the CAPAS program would help the state to prioritize the use of state funds and prison space for offenders who pose the greatest danger to the community.

- Result in Significant State Savings. As discussed above, our proposal potentially could result in significant corrections savings to the state, as a result of a reduction in probation revocations to prison. The state could also experience operational and capital outlay savings from slowing the growth in the prison population under CAPAS. For example, our proposal would likely reduce costs for the processing of new inmates into the prison system, inmate health care, transportation of new inmates, as well as delay or eliminate the need to construct new prison facilities in the future.

LAO Realignment Reports Involving Probation

Over the years, our office has published numerous reports on the subject of state and local program realignments, some of which have included realigning certain responsibilities to county probation. For example, in The 2008–09 Budget: Perspectives and Issues (please see page 125), we recommended realigning responsibility for lower–level adult parolees to county probation. We believe that shifting responsibility for this group of offenders, along with the corresponding amount of funding the state spends to supervise them, would improve outcomes since these parolees could be better rehabilitated and integrated into their local communities by county probation.

More recently, our office, as part of our 2009–10 Budget Analysis Series (please see the report titled Criminal Justice Realignment), recommended shifting responsibility for punishment and treatment of certain adult offenders with substance abuse problems from the state to counties. Under our proposal, counties would receive a dedicated funding stream to carry out this responsibility. Counties could use the resources to place individuals in jails or resident treatment facilities, or to supervise them in the community while they attend substance abuse treatment programs. Notably, both of the above realignment proposals could work in conjunction with the recommendations in this report to further improve public safety outcomes. |

Conclusion

In summary, our proposed program would provide financial incentives for county probation departments to (1) implement the best practices identified by experts as critical for reducing recidivism rates and (2) reduce their revocations to state prison. This, in turn, would result in better public safety outcomes for local communities. At the same time, our proposal would help reduce state prison and parole expenditures, which have increased significantly over the past 20 years and takes up a greater portion of the state budget. In addition, by reducing the number of probationers sent to prison, our proposal could help alleviate the significant overcrowding in the prison system. This could be particularly important given the issuance of a tentative ruling on February 9, 2009, by a federal three–judge panel that the state must reduce the state’s inmate population by tens of thousands of inmates.

|

Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by

Paul Golaszewski and Brian Brown with assistance from Shereda Robinson, and reviewed by

Anthony Simbol. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan

office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as

an E-mail subscription service, are

available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925

L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814.

|

Return to LAO Home Page