May 7, 2009

California's Cash Flow Crisis: May 2009 Update

Summary

(Five-minute video summary)

See also: Conference Committee Update: California's Cash Flow Crisis (May 22, 2009)

Much Progress Was Made in February... The February budget package addressed a $40 billion shortfall in California’s finances, thereby helping the state’s dire cash flow situation. The package also delayed or deferred numerous state payments and allowed over $2 billion of state special funds to be borrowed by the General Fund on a temporary basis for cash flow purposes. These actions allowed the Controller to end a one–month halt on tax refunds, payments to local governments, and other payments. The Controller has stated that the state will be able to pay its bills “in full and on time” through the rest of the 2008–09 fiscal year. In addition, passage of the February package led the Treasurer to resume sales of long–term infrastructure bonds, and recently, this allowed the state to resume funding for thousands of infrastructure projects that had been halted due to the cash crisis in late 2008.

…But Cash Flow Pressures Are Likely to Reemerge in Summer and Fall 2009. While the February budget package eased the state’s cash flow crunch considerably, the budget and cash pressures of recent months have taken their toll. The General Fund’s “cash cushion”—the monies available to pay state bills at any given time—currently is projected to end 2008–09 at a much lower level than normal. Without additional legislative measures to address the state’s fiscal difficulties or unprecedented amounts of borrowing from the short–term credit markets, the state will not be able to pay many of its bills on time for much of its 2009–10 fiscal year. Deterioration of the state’s economic and revenue picture (such as the $8 billion revenue shortfall we forecasted in March) or failure of measures in the May 19 special election would increase the state’s cash flow pressures substantially—potentially increasing the short–term borrowing requirement to well over $20 billion. California is likely to have difficulty borrowing anywhere close to the needed amounts from the short–term bond markets based on the state government’s own credit.

Prompt Legislative Action Required. Time is of the essence in addressing California’s cash flow challenges. In our opinion, the greatest near–term threat to state cash flows would be an inability by state leaders to quickly address California’s budget imbalance. If there were to be a prolonged impasse, the Treasurer and Controller could be prevented from borrowing sufficient funds to allow the state to pay its bills on time. In such a scenario, the Controller would have much less flexibility than he did in February (during personal income tax refund season) to delay non–priority state payments. An inability to borrow sufficient funds by the Controller and Treasurer could subject many more Californians—including local governments, vendors, and, perhaps, in some dire scenarios, state employees and many others awaiting payments from the state—to prolonged payment delays. Payment delays could affect many major state funds during a prolonged impasse, including the General Fund and special funds, all of which are funded from liquid resources in the state investment pool. Such payment delays could subject the already fragile state budget to even more costs (such as penalties and interest).

The Legislature’s Options to Address the Situation. We advise the Legislature to reduce the state’s short–term borrowing need to an amount under $10 billion for 2009–10. (Regular updates from the administration on the projected cash flow situation, therefore, will be necessary during the upcoming budget deliberations.) To reduce the borrowing need and limit the state’s interest costs in 2009–10, the Legislature has two very difficult options:

- Additional actions to increase revenues or decrease expenditures in order to return the 2009–10 budget to balance.

- Additional actions to delay or defer scheduled payments to schools, local governments, service providers, and others.

Federal Assistance Could Come With “Strings Attached.” We believe it is appropriate for the Treasurer to explore the possibility of federal assistance—such as a federal loan guarantee—to address this summer and fall’s grim cash outlook. We caution the Legislature, however, against assuming such federal assistance will be available. By taking prompt actions to reduce the state’s cash flow borrowing need to under $10 billion for 2009–10, policymakers would enhance the ability of the Treasurer and Controller to secure private investment with or without a federal loan guarantee. Moreover, reducing the state’s cash flow borrowing will involve actions that improve the state’s medium– and long–term budgetary outlook. These actions would increase confidence in the bond markets, which are needed to continue providing funds for infrastructure projects that spur economic activity and long–term growth. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, we advise the Legislature and other state policymakers to be cautious about accepting any strings that might be attached to federal assistance. Strings attached to recent corporate bailouts—as well as federal loan guarantees provided to New York City during its fiscal crisis three decades ago—have included measures to remove financial and operational autonomy from executives. We recommend that the Legislature agree to no substantial diminishment in the role of California’s elected state leaders. In our opinion, the difficult decisions to balance the state’s budget now are preferable to Californians losing some control over the state’s finances and priorities to federal officials for years to come.

Introduction

In January 2009, we published California’s Cash Flow Crisis, one of the reports in our 2009–10 Budget Analysis Series. This report provides an update on matters discussed in the January piece. Specifically, this report includes the following sections:

- A history of the state’s recent cash flow problems.

- California’s cash flow outlook.

- The Legislature’s options to improve the cash flow outlook.

- The possibility of federal assistance for the state’s cash flow challenges.

History of the State’s Recent Cash Flow Problems

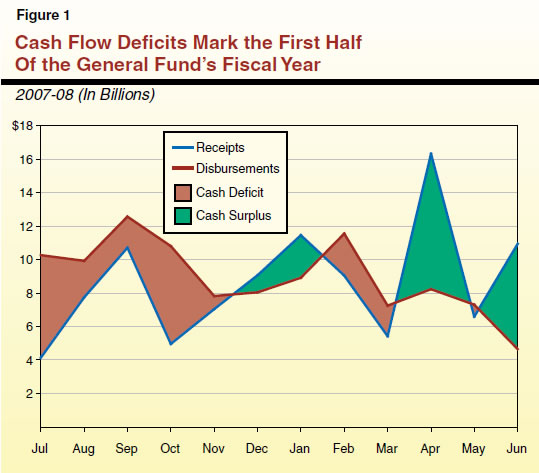

State Must Borrow for Cash Flow Purposes Every Year. In California’s Cash Flow Crisis, we discussed the basic dynamics of the state’s General Fund cash flows. Specifically, the report described how the state generally disburses the majority of General Fund dollars in the first half of the fiscal year (that is, between July and December), while it collects the majority of General Fund receipts in the second half of the fiscal year (between January and June). As shown in Figure 1 (which uses 2007–08 monthly cash flows as a typical example), this means that the state routinely runs monthly cash flow deficits through the first half of the fiscal year and monthly cash flow surpluses through much of the second half. To address this regular imbalance of receipts and disbursements, the state must borrow for cash flow purposes each year: first, from internally borrowable resources (principally, several hundred “special funds” in the state treasury) and second, from external private investors.

“Double Whammy” of Weak Revenues and Credit Crisis Hurt State’s Cash Position. As we described in our January 2009 report, weakening state revenues and limited access to the credit markets in the first half of 2008–09 reduced the state’s resources to address cash flow deficits. At the end of 2008, state officials halted funding for thousands of infrastructure projects in order to conserve state cash resources. Projections at the time indicated that, absent action by the Legislature or the Controller to conserve cash, available resources to fund normal state operations—also known as the state’s cash cushion—would be exhausted by the end of February 2009. (The Controller typically aims to have a minimum $2.5 billion cash cushion in state accounts at any given time.) At the beginning of February 2009, the Controller used his authority to begin delaying certain state payments deemed to be of a lower priority under state law, including many vendor payments, payments to local governments, and tax refunds to individuals and corporations. By delaying about $3 billion of payments in February, the Controller was able to conserve the cash cushion to make other “priority payments” of the state (such as payments for schools, debt service, and state payroll) on time.

Legislative Actions Have Eased Cash Crunch During Second Half of 2008–09. The budget package approved by the Legislature on February 19 and signed by the Governor on February 20 addresses a $40 billion budget shortfall with a combination of temporary tax increases, spending cuts, borrowing, and federal stimulus funds. (For more information on the budget package, see our 2009–10 Budget Analysis Series report entitled The Fiscal Outlook Under the February Budget Package.) By their nature, revenue increases, spending cuts, and other budget–balancing actions help the state’s cash situation by putting or leaving more money in the state’s coffers. In addition to these budgetary actions, the Legislature approved a bill—Chapter 9, Statutes of 2009–10 Third Extraordinary Session (AB 13xxx, Evans)—to make additional, substantial changes to the state’s cash management practices. This bill was in addition to similar cash management legislation passed as part of the original 2008–09 budget package in September 2008.

The cash management actions enacted by the Legislature have played a key role in helping the state meet its priority payments on time through 2008–09. In total, since the beginning of the fiscal year, the Legislature has added funds with over $6 billion of balances to the list of state accounts able to be borrowed by the General Fund temporarily for cash flow purposes. The Legislature also has deferred several billion dollars of payments to later in the 2008–09 and 2009–10 fiscal years. In addition, through its enactment of legislation in March 2009, the Legislature allowed the state to take immediate receipt of $1.5 billion of federal stimulus funds for Medi–Cal, which directly benefits the General Fund. In May 2009, the state will draw down nearly $800 million of federal stimulus funds available to cover costs of the state prison system on an expedited basis, thereby reducing General Fund expenditures. Enactment of the February budget package also helped the Treasurer to execute an additional $500 million cash flow borrowing with The Golden 1 Credit Union and restart long–term infrastructure bond sales. Two huge and extraordinarily successful long–term bond sales in March 2009 and April 2009 raised over $13 billion for state projects and allowed the administration to end the state project “funding freeze” that had been instituted in late 2008 due to the cash crisis.

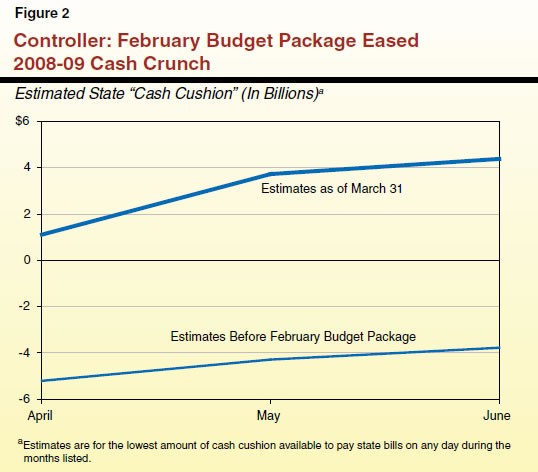

Controller Was Able to End Previously Instituted Delay of Certain State Payments. Due to all of the cash flow and budgetary changes described above, the Controller was able to end the delay of non–priority state payments. On March 31, 2009, the Controller stated that the state government had sufficient cash resources to “meet all of our obligations in full and on time” through the rest of 2008–09. Figure 2 shows the Controller’s estimates of the state’s cash cushion in late 2008–09 both before enactment of the February budget package and on March 31, when he was able to make this statement. The dramatically improved March 31 figures reflect (1) enactment of the February budget package, (2) completion of the $500 million short–term Golden 1 cash flow borrowing, and (3) the accelerated receipt of Medi–Cal stimulus funds.

California’s Cash Flow Outlook

Administration Projections Indicate a New Cash Crisis May Lie Ahead. In early March 2009, the Department of Finance (DOF) prepared an estimate of how the various measures associated with the package (including the tax increases, spending reductions, payment deferrals, and newly authorized borrowable funds) affected the state’s cash flow outlook through the end of 2009–10. Even after including about $1 billion of extra disbursements in the forecast for “unanticipated cash risks” through the end of 2008–09, DOF indicated that the budget package had practically eliminated the cash crunch in the current fiscal year. The DOF forecast, however, indicated the possibility of severe cash flow pressures reemerging as soon as July 2009 and persisting through much of 2009–10.

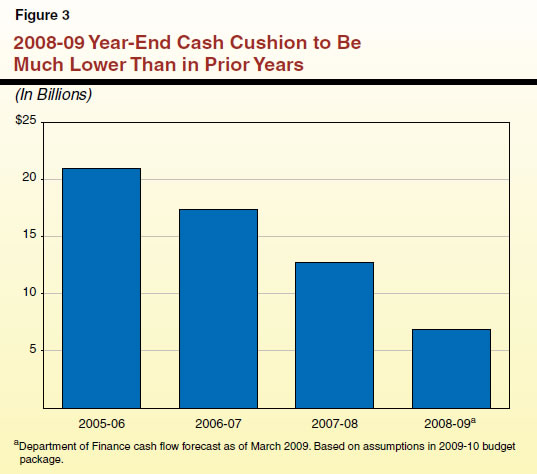

Severely Weakened Cash Cushion at the End of 2008–09 Is Expected to be a Key Problem. The key problem identified in the DOF forecast is the likelihood of a severely weakened state cash cushion at the conclusion of the 2008–09 fiscal year. While the budget package allows the state, in the Controller’s view, to meet its budgeted obligations on time through the rest of 2008–09, the DOF forecast shows that the state cash cushion would be $6.9 billion on June 30. This is much less than the state typically has in its cash cushion at the end of a fiscal year—indicative of the fact that the state will most certainly end the 2008–09 fiscal year with a budgetary deficit. (The February budget plan anticipated there being an operating surplus in 2009–10 to address the 2008–09 budget deficit and build up a reserve account.) Figure 3 shows that the expected fiscal year–end cash cushion at June 30, 2009, is roughly one–half of the cash cushion the state had one year before and only about one–third of the amount of three years ago. To put these figures in perspective, note that the year–end cash cushion for 2008–09 reflects the Legislature’s actions over the past year to add several billion dollars of funds to that cash cushion in the form of new special funds eligible to be borrowed by the General Fund for cash flow purposes. Had the Legislature not taken various budgetary and cash management actions such as these, the state’s cash cushion would have been zero at the end of 2008–09.

Potentially Unprecedented Short–Term Borrowing May Be Required in 2009–10. A weakened cash cushion on June 30 is a problem because of the basic dynamics of the state’s General Fund cash flows displayed earlier in Figure 1. The state disburses the bulk of its General Fund expenditures during the first half of the fiscal year, but collects most of its receipts later. This means that several months at the beginning of the fiscal year have monthly cash flow deficits—that is, months when monthly General Fund receipts are less than monthly General Fund disbursements. While the DOF’s March 2009 forecast projects a cash cushion of $6.9 billion (consisting entirely of borrowable special fund balances—with no available General Fund balance) as of June 30, 2009, the forecast indicates that the General Fund is expected to have a monthly cash flow deficit of $7.9 billion in July 2009 alone. The estimated cash flow deficit in that month is so great that DOF estimates the cash cushion will be depleted under the February budget package unless the Controller delays state payments once again as he did in February or the state borrows funds from private investors. The state borrows on a short–term basis from the credit markets virtually every year by issuing revenue anticipation notes (RANs). These notes, along with a related borrowing source—revenue anticipation warrants (RAWs)—are described in the box below.

Revenue Anticipation Notes (RANs) and Revenue Anticipation Warrants (RAWs) RANs. The state’s most commonly used device for external cash flow borrowing is the RAN—a low–cost, short–term financing tool. Typically issued early in the fiscal year, RANs must be repaid prior to the end of the fiscal year of issuance (usually in April, May, or June). Unlike most of the state’s long–term infrastructure bonds, RANs are not state general obligations. The RANs are secured by money in the General Fund that is available after providing funds for the state’s “priority payments,” such as payments to schools, general obligation debt service, and state employee payroll, among other payments. The State Treasurer’s office works with financial firms to issue RANs almost every year. The state has sold $5.5 billion of RANs to investors during 2008–09. RAWs. The state has issued RAWs for cash flow relief occasionally since these securities were created during the severe state budget crisis of the early 1930s. The main reason that the state resorts to RAWs is that they can be repaid in a subsequent fiscal year after their issuance. In fact, one California RAW issued in July 1994 matured 21 months later. The ability to have a later maturity date means the state can borrow for cash flow purposes even if the state’s cash outlook is challenging in the near term. Because of this longer maturity schedule and the fact that RAWs typically are issued when the state faces challenging budget times, they generally are more costly—with higher interest and other issuance costs—than RANs. The state’s $7 billion of RAWs in 1994, for example, resulted in interest and other issuance costs of over $400 million, and the $11 billion of RAWs in 2003 resulted in over $260 million of costs. The State Controller’s office works with financial firms to issue RAWs. |

A huge concern is that monthly cash flow deficits of varying amounts are expected under the February budget package every month between July 2009 and November 2009. These five consecutive months of monthly cash flow deficits mean that, under the DOF forecast, the state would need to borrow amounts that could grow to well over $13 billion by about October—probably through issuance of RANs or RAWs—in order to pay all bills on time and maintain the state’s traditional minimum cash cushion of $2.5 billion. Figure 4 summarizes DOF’s March 2009 cash flow forecast by showing the expected end–of–month state cash cushion throughout 2009–10 before considering any borrowing from private investors. The forecast shows the state’s accumulated cash deficit—illustrated in Figure 4 as the “negative cash cushion”—would reach $10 billion to $11 billion for much of the middle part of 2009–10. The state, therefore, might need to borrow over $13 billion from investors in order to pay all currently budgeted bills on time and maintain the target minimum $2.5 billion cash cushion described above.

Some Negative Signs Have Emerged Since the March Cash Forecast. Figure 5 lists several developments for the state’s cash flow situation that have emerged since DOF completed its forecast in March. Some of these developments have been good news. For example, the Controller reported that, through the end of March, amounts in borrowable special funds were running about $2 billion higher than forecast. (It is not known whether this will be a sustained trend.) In addition, as described earlier, about $800 million of federal stimulus moneys for corrections was received earlier this month—over one year in advance of its expected date of receipt based on the DOF March forecast. (While legislative action allowed the state to expedite receipt of certain Medi–Cal funds from the federal government, this already was factored in DOF’s 2009–10 cash flow forecast.) On the other hand, more than offsetting these positive developments has been a variety of negative economic and state revenue data, which led our office to project in March 2009 that General Fund revenues in 2009–10 would be about $8 billion below those assumed in the February budget package and DOF’s March cash forecast. (Because of the timing of state receipts, a loss of $8 billion in annual revenues does not necessarily mean the state needs to borrow the same $8 billion to keep paying bills on time in each month.) Net state receipts of personal income and corporate tax payments in April 2009 also were weaker than expected—adding to poor February and March revenue collections. After considering these developments and assuming that higher amounts in borrowable special funds persist, we can make a rough estimate that the state’s borrowing requirement from private investors in 2009–10 may be somewhere around $17 billion—or $4 billion higher than forecast by DOF in March. Further projected revenue declines or expenditure increases could add to this borrowing need, including the voters’ possible rejection of Propositions 1C, 1D, and 1E on the May 19 ballot. As shown in Figure 5, rejection of these measures could cause the state’s 2009–10 investor borrowing requirement to swell to around $23 billion.

Figure 5

State’s 2009‑10 Short-Term Borrowing Need |

(In Billions) |

Administration's March Cash Forecast |

$13 |

Known developments since March cash forecast |

|

Higher amounts in borrowable special funds (as of March 31) |

-$2 |

Expedited receipt of federal stimulus funds for corrections |

-1 |

Lower revenue receipts from February to April 2009 |

3 |

Possible need based on LAO's forecast of lower 2009‑10 revenuesa |

4 |

Subtotal |

($4) |

Rough Estimate Based on Known Developments Since March |

$17 |

Effect if Propositions 1C, 1D, and 1E Are Rejected by Voters |

$6 |

Rough Estimate if Proposition are Rejected by Voters |

$23 |

|

a In a March 2009 report we forecast that General Fund revenues would be $8 billion below the February budget package forecast in 2009‑10. Because some of this difference affects state receipts in April through June 2010, when state cash flows are relatively strong, this difference would not likely result in an $8 billion increase in the state's needed borrowing from short-term investors. Instead, the decrease in revenues should result in a smaller increase in the state's borrowing need. We show $4 billion here as a very rough estimate. |

Borrowing Well Over $13 Billion on the State’s Own Credit May Not Be Possible. Officials of the administration, the Treasurer’s office, and the Controller’s office meet regularly with representatives of financial institutions and institutional investors in the municipal credit markets. Despite the state’s recent successes issuing bonds in the long–term credit markets, the major financial institutions reportedly have indicated to state officials that California will have difficulty borrowing $13 billion from the short–term markets based on its own credit in 2009–10—let alone the much larger amount of around $23 billion discussed in Figure 5. There are various reasons why the state may have difficulty borrowing such large amounts:

- First, this would be an unprecedented amount of short–term borrowing for the state. State short–term borrowing reached a peak of just under $14 billion—raised through issuance of both RANs and RAWs—during 2003–04, but this occurred during a period of relatively easy credit availability. Then, liquidity in the short–term credit markets was healthy (unlike in recent months) and credit standards of investors and banks were less restrictive than they are now.

- Second, the amount of borrowing as a percentage of state receipts—over 13 percent for a $13 billion short–term borrowing—is at least double the maximum typically recommended by municipal bond market credit experts. This means it is likely that RAWs or RANs totaling over $13 billion would have a poor credit rating. With weakened banks and other financial institutions limited in their ability to offer credit enhancement (essentially, a type of bond insurance) to the state’s RAWs or RANs, a low rating will mean that major segments of the short–term investor market will be unable or unwilling to participate in the state’s 2009–10 cash flow borrowing. With fresh memories of their own liquidity crisis last year, major short–term market investors—such as money market funds—have stricter credit standards than ever before, and they may be reluctant to purchase RANs or RAWs with a low rating. Even if investors did purchase the securities, state interest costs for borrowing may exceed budgeted amounts—potentially by as much as hundreds of millions of dollars—as the administration warned the Legislature in a budget letter submitted in early April 2009.

Recommendations and Options for the Legislature

In this section, we address ways that the Legislature can address the state’s cash flow crisis. First, we discuss broad goals concerning state cash flows for the Legislature to consider in its upcoming budget deliberations. Second, we discuss specific options that the Legislature may need to consider to achieve these goals. Third, we discuss the important issue of timing: when the Legislature needs to take action to provide the greatest possible assurance that the state can continue paying its bills on time.

Broad Goals for the Legislature Concerning State Cash Flows

Recommended Legislative Goal: Reducing State’s Need for Short–Term Borrowing. While the state’s recent success in selling long–term infrastructure bonds and resuming funding of voter–approved projects is a positive sign, we are concerned about the potential difficulty and high costs involved in borrowing $13 billion or more for cash flow needs in 2009–10. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature focus in the coming weeks on a goal of reducing the state’s cash flow borrowing need for 2009–10 to somewhere below $10 billion. In any scenario, this will make it easier for state officials to execute the state’s cash flow borrowing. To accomplish this goal, the Legislature will need to ask the administration for regular updates on projected cash flows during its upcoming budget deliberations.

Reducing Short–Term Borrowing Need Below $10 Billion Means More Difficult Choices. Just as the Legislature faced difficult choices earlier in 2008–09 to balance the budget and address the cash flow crisis, even more difficult choices remain for returning the budget to balance and reducing the 2009–10 cash flow borrowing need below $10 billion. The options for the Legislature to accomplish this fit into two general categories:

- Budgetary actions to increase revenues or decrease expenditures of the General Fund or other state funds available for cash flow borrowing.

- Cash flow actions to delay budgeted state payments or accelerate receipt of revenues from either the General Fund or borrowable special funds.

Returning the Budget to Balance Would Help the Cash Flow Situation. By their nature, actions to increase state revenues or decrease expenditures help the cash flow situation, thereby reducing the required borrowing from short–term credit markets. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature focus first on addressing the budget deficit. However, because budgetary balancing actions will not necessarily deliver their full benefit in the opening months of the fiscal year—when the state’s cash flow problems are the greatest—balancing the budget alone may not solve the state’s cash flow difficulties. Additional actions to defer payments or accelerate state receipts during the fiscal year may be necessary.

Specific Options for the Legislature to Achieve These Goals

Beyond the very difficult choices for the Legislature in returning the 2009–10 state budget to balance, there are some particular options that lawmakers may need to consider to address the state’s cash flow challenge.

Additional Payment Deferrals May Be Necessary. Because state payments to schools represent a large portion of General Fund disbursements in cash flow deficit months like July and October, additional measures to delay scheduled state payments to schools may be necessary. Deferrals of scheduled payments for various other programs also may be required. To the extent that federal stimulus funds are available to school districts and other local governments by early in the 2009–10 fiscal year, this may help governmental entities cope with additional payment delays.

Accelerating Issuance of Lottery Securitization Bonds May Prove Beneficial. The DOF cash projections assume that the state receives $5 billion of lottery securitization proceeds—contingent upon voter approval of Proposition 1C in May 2009—in March 2010. To ease the fall 2009 cash crunch somewhat, we recommend that the Legislature encourage the administration, which would control the lottery borrowing process under Proposition 1C, to pursue issuing some or all of the lottery securitization bonds by October 2009. The lottery borrowing—a long–term bond market offering—would reduce the need for issuance of short–term state obligations by the Treasurer or Controller by perhaps a few billion dollars in the fall. Reducing the size of these short–term obligations would make it easier for state officials to market securities to short–term investors.

“Trigger Legislation” May Be Required. In our January report on the cash flow crisis, we discussed the possibility that so–called trigger legislation might be needed to facilitate the sale of RAWs by the Controller. In the past, trigger legislation—such as Chapter 135, Statutes of 1994 (SB 1230, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review)—has helped the state sell short–term cash flow instruments by providing greater assurances to potential investors. Chapter 135 required the state to reduce most categories of expenditures at the time if cash flow projections showed that timely payment of RAWs was threatened. Given the need to preserve the Legislature’s constitutional prerogatives over the state budget, we would be reluctant to recommend passage of trigger legislation that ceded to the Governor the ability to determine which revenues were increased or expenditures decreased to provide assurances to investors of timely RAW repayment. Instead, assuming such legislation proves necessary, we advise the Legislature—as it did in the February budget package in constructing a revenue and expenditure trigger tied to the receipt of federal stimulus moneys—to specify which expenditures would be decreased and revenues increased in any RAW trigger legislation.

Action by Late June or Early July at the Latest Is Needed

Time Is of the Essence in Addressing Cash Flow Problems. Addressing the state’s cash flow challenges is inherently a matter of timing. For the state to have sufficient funds to make General Fund and special fund payments on time, access to sufficient borrowed funds—from both internal sources and private investors—is needed by a given date. The DOF projections under the terms of the February budget package show that the state will need to begin borrowing from private investors in the short–term credit markets in July. Under this package, a total of well over $13 billion in private borrowing likely would need to be completed by October. As discussed earlier, the state may face a major new budgetary gap that will also worsen the state’s cash situation. Absent legislative actions to rebalance the budget and address the state’s budgetary and cash flow difficulties, private investors may be unwilling to lend the state such large sums. Therefore, legislative actions to return the budget to balance and address the state’s cash flow challenges may be required before the Treasurer and Controller can issue the required amount of RANs or RAWs. Accordingly, in our view, the most significant near–term threat to the state’s cash flows is a prolonged legislative impasse in addressing California’s budget difficulties after the May Revision. The Controller and Treasurer will have the greatest ability to issue sufficient RANs and RAWs in a timely fashion if the Legislature restores the budget to balance and takes action to reduce the state’s short–term borrowing need by late June 2009 or early July 2009 at the latest. By taking action on this timeline, the Legislature would allow state officials to begin to access the short–term credit markets in early or mid–July. In any event, the earlier the Legislature takes action after the special election to address the state’s budget and cash problems, the less likely that the Controller will have to resume delaying state payments in order to preserve cash for timely disbursement of priority payments, such as payments to schools and bondholders.

The Possibility of Federal Assistance

Treasurer Exploring Federal Assistance, Such as a Federal Guarantee for RANs or RAWs. Given the possible difficulty for the state marketing a vast amount of short–term notes or warrants, the Treasurer’s office has indicated that it is exploring potential federal assistance for the state (and other public entities) that need to access the short–term debt markets. We believe that it is appropriate for the Treasurer to explore these options with federal officials. Among the options for possible federal assistance are:

- A federal guarantee of the state’s short–term cash flow borrowing.

- A federal commitment to purchase the state’s RANs or RAWs from investors in certain circumstances, perhaps using funds of the Troubled Assets Relief Program approved by Congress in 2008.

- Accelerated receipt of federal stimulus moneys that offset state General Fund expenditures, which could reduce the state’s need for cash flow borrowing in 2009–10.

Recently, the U.S. government has assisted various financial institutions and corporate entities facing insolvency. In addition, there is precedent for a federal guarantee of a public entity facing serious financial difficulties. In 1978, the Congress passed and President Carter signed the New York City Loan Guarantee Act, a response to the city’s severe fiscal crisis at the time. A properly structured federal loan guarantee of this type would allow the state relatively simple access to the bond markets. Such bond market access would be based on the U.S. government’s full faith and credit. A guarantee may require approval by the Congress in a bill, which would be subject to approval or veto by the President.

Recommend That Legislature and Policymakers Be Cautious About Strings Attached to Federal Assistance. Given recent experience, it is likely that any substantial federal assistance for California’s cash flow problems would come with conditions. Recent federal bailouts of private entities have involved those entities losing at least some operational autonomy to federal officials. At the very least, as occurred with New York City’s loan guarantees in the 1970s, the federal government likely would charge the state a fee for a federal loan guarantee—just as a bank or bond insurer guaranteeing state debt obligations would. Nevertheless, the federal government also could insist on a binding, multiyear budget balancing plan from the state or the ability to assume some sort of operational control or oversight of state operations in certain cases. For example, the New York City guarantee act required the city to submit to the Secretary of the Treasury a plan for balancing its budget within roughly four years and mandated that an independent fiscal monitor “demonstrate to the satisfaction of the secretary that it has the authority to control the city’s fiscal affairs during the entire period in which federal guarantees are outstanding.” The state–created fiscal control board that oversaw New York City’s finances remains in existence to this day, although many of its powers under state law have expired. In short, the Legislature and policymakers should expect that there would be strings attached to federal assistance. While the severe nature of the state’s cash flow problems necessitate considering an offer of federal aid, we recommend that the Legislature be very cautious about accepting federal aid with strings attached that undermine the ability of this Legislature or future Legislatures to set the state’s fiscal and policy priorities. We recommend that the Legislature agree to no substantial diminishment of the role of California’s elected state leaders. In our opinion, the difficult decisions to balance the state’s budget now are preferable to Californians losing some control over the state’s finances and priorities to federal officials for years to come.

Legislature Should Not Assume Federal Assistance Will Be Forthcoming. We recommend that the Legislature not proceed with the assumption that federal assistance will be forthcoming to deal with this summer and fall’s state cash flow problems. By beginning to address the state’s budget and cash flow challenges immediately after the May special election, the Legislature will give the Treasurer and Controller the greatest range of options to address the state’s expected cash flow challenges. Moreover, the Legislature’s prompt actions to return the budget to balance and reduce the cash flow problem may help convince federal officials that temporary assistance to the state is justified.

Conclusion

While the February budget package and earlier legislative decisions have helped ease the state’s cash crunch during 2008–09, major challenges for the state’s cash flows loom in the summer and fall of 2009. In our opinion, the greatest near–term threat to the state paying its budgeted bills on time would be a prolonged impasse by the state in addressing California’s budgetary and cash flow challenges after the May special election. Moreover, we recommend that the Legislature not proceed with the assumption that federal assistance will be available to help the state address its cash flow crisis. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature:

- Focus in the coming weeks on reducing the state’s cash flow borrowing need for 2009–10 to somewhere below $10 billion.

- Act quickly—by late June or early July at the latest—to address the state’s budget and cash flow challenges in order to help the Controller and Treasurer access the short–term bond markets beginning in July.

- Consider additional cash management measures, including possible additional delays in scheduled payments and acceleration of receipt of lottery securitization proceeds.

- Be very cautious about accepting federal assistance for the state’s cash–flow problems, especially given the strings that may be attached to such aid.

|

Acknowledgments This report was prepared by Jason Dickerson and reviewed by Michael Cohen. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an

E-mail subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814.

|

Return to LAO Home Page