February 11, 2016

The 2016-17 Budget

Analysis of the Medi-Cal Budget

Executive Summary

The Governor’s budget proposes $19.1 billion General Fund for Medi–Cal. This is an increase of $1.4 billion—or 8 percent—above the estimated 2015–16 spending level. This year–over–year increase is due to several factors, such as projected increases in caseload and the loss of General Fund savings due to the impending sunset of the managed care organization (MCO) tax and the hospital quality assurance fee (QAF).

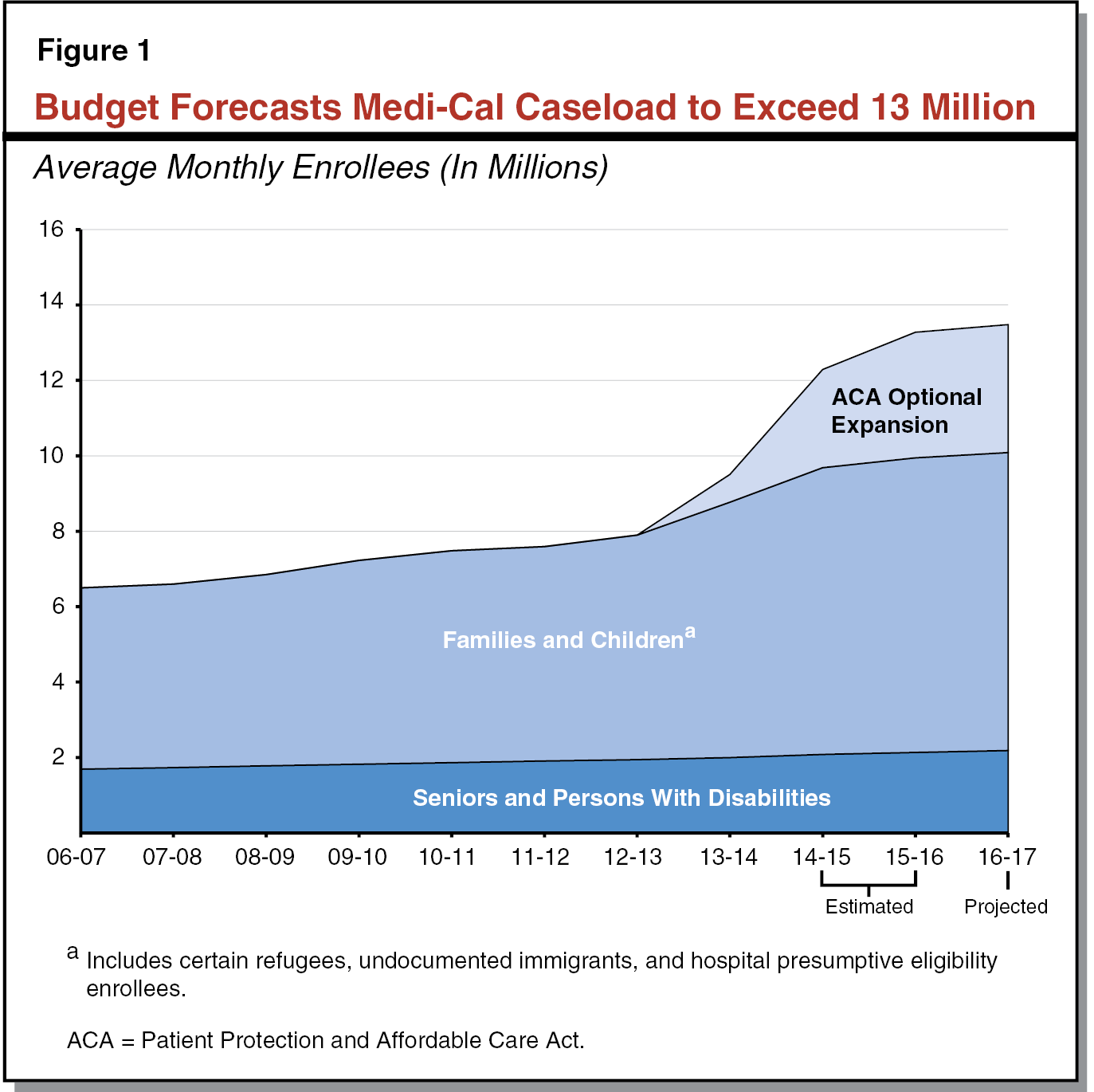

Governor’s Caseload Projections Appear Reasonable. The Governor’s budget assumes total annual Medi–Cal caseload of 13.5 million for 2016–17, an increase of 2 percent over revised 2015–16 caseload. We have reviewed the administration’s caseload projections in the context of the substantial changes to Medi–Cal caseload in recent years as a result of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), and we find the estimates to be reasonable.

ACA Implementation Creates Substantial Uncertainty in Projecting Caseload. ACA–related changes have made it more difficult to project caseload using trends in historical caseload data from recent years. This difficulty arises because the initial impacts of ACA implementation on caseload are unlikely to continue in future years. As the initial changes associated with ACA implementation stabilize, caseload trends and their relationship to changes in the economy will become more useful for projecting caseload. However, until that time, both the administration’s and our office’s caseload projections are likely to be more uncertain than in the past. When making budgetary decisions, the Legislature should consider this uncertainty with the understanding that small changes (both increases and decreases) in Medi–Cal caseload can have large impacts on the Medi–Cal budget. Further, we recommend the Legislature require the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) to report at May Revise hearings on how the most recent data on caseload and redeterminations have informed and changed caseload projections.

Several Potential General Fund Cost Pressures on the Horizon. Beginning in 2016–17 and over the next several years, there are several major changes that could occur in the Medi–Cal program and potentially result in total increased General Fund costs as high as the low billions of dollars annually. The potential cost pressures include (1) the sunset of the hospital QAF, (2) impacts associated with the proposed changes to the federal government’s Medicaid managed care regulations, (3) the potential loss of certain federal funds for uncompensated care, (4) the phase in of the state’s share of cost for the ACA optional expansion population, and (5) the potential reduction in federal funds for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). We recommend the Legislature extend the hospital QAF this legislative session to provide greater assurance that the fee’s benefit in drawing down federal funds is maximized by preventing a lapse in the fee being operative. We also recommend the Legislature consider these General Fund pressures when making policy and budgetary decisions. These cost pressures may inform legislative decisions related to ongoing spending commitments and building up reserves as the Legislature crafts the 2016–17 budget.

Overview

The Governor’s budget proposes $19.1 billion General Fund for Medi–Cal. This is an increase of $1.4 billion—or 8 percent—above the estimated 2015–16 spending level. This year–over–year increase is due to several factors, such as projected increases in caseload and the loss of General Fund savings due to the impending sunset of the MCO tax and the hospital QAF. The proposed budget reserves most revenues associated with the MCO tax in a special fund pending passage of a restructured MCO tax by the Legislature, while the hospital QAF will sunset on January 1, 2017 absent an extension of the fee.

In this report, we provide an analysis of the administration’s caseload projections, as well as a discussion of the impacts of the ACA on the ability to project caseload. We also provide an assessment of several General Fund cost pressures on the horizon in Medi–Cal, including the sunset of the hospital QAF.

Background

In California, the federal–state Medicaid Program is administered by DHCS as the California Medical Assistance Program (Medi–Cal). Medi–Cal is by far the largest state–administered health services program in terms of annual caseload and expenditures. As a joint federal–state program, federal funds are available to the state for the provision of health care services for most low–income persons. Until recently, Medi–Cal eligibility was mainly restricted to low–income families with children, seniors and persons with disabilities (SPDs), and pregnant women. As part of ACA, beginning January 1, 2014, the state expanded Medi–Cal eligibility to include additional low–income populations—primarily childless adults who did not previously qualify for the program.

Financing. The costs of the Medicaid program are generally shared between states and the federal government based on a set formula. The federal government’s contribution toward reimbursement for Medicaid expenditures is known as federal financial participation. The percentage of Medicaid costs paid by the federal government is known as the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP).

For most families and children, SPDs, and pregnant women, California generally receives a 50 percent FMAP—meaning the federal government pays one–half of Medi–Cal costs for these populations. However, a subset of children with higher incomes qualify for Medi–Cal as part of the state’s CHIP. Currently, the federal government pays 88 percent of the costs for children enrolled in CHIP and the state pays 12 percent. Finally, under ACA, the federal government will pay 100 percent of the costs of providing health care services to the newly eligible Medi–Cal population from 2014 through 2016. Beginning in 2017, the federal cost share will decrease to 95 percent, phasing down to 90 percent by 2020 and thereafter.

Delivery Systems. There are two main Medi–Cal systems for the delivery of medical services: fee–for–service (FFS) and managed care. In a FFS system, a health care provider receives an individual payment from DHCS for each medical service delivered to a beneficiary. Beneficiaries in Medi–Cal FFS generally may obtain services from any provider who has agreed to accept Medi–Cal FFS payments. In managed care, DHCS contracts with managed care plans, also known as health maintenance organizations, to provide health care coverage for Medi–Cal beneficiaries. Managed care enrollees may obtain services from providers who accept payments from the managed care plan, also known as a plan’s “provider network.” The plans are reimbursed on a “capitated” basis with a predetermined amount per person, per month regardless of the number of services an individual receives. Medi–Cal managed care plans provide enrollees with most Medi–Cal covered health care services—including hospital, physician, and pharmacy services—and are responsible for ensuring enrollees are able to access covered health services in a timely manner. (In some counties, Medi–Cal managed care plans also provide long–term services and supports, including institutional care in skilled nursing facilities, and home– and community–based services.) The number and type of managed care plans available vary by county, depending on the model of managed care implemented in each county. Counties can generally be grouped into four main models of managed care.

- County Organized Health System (COHS). In the 22 COHS counties, there is one county–run managed care plan available to beneficiaries.

- Two–Plan. In the 14 Two–Plan counties, there are two managed care plans available to beneficiaries. One plan is run by the county and the second plan is run by a commercial health plan.

- Geographic Managed Care (GMC). In GMC counties, there are several commercial health plans available to beneficiaries. There are two GMC counties—San Diego and Sacramento.

- Regional. Finally, in the Regional model, there are two commercial health plans available to beneficiaries across 18 counties.

Imperial and San Benito Counties have managed care plans that are not run by the county, and that do not fit into one of these four models. In Imperial County, there are two commercial health plans available to beneficiaries and in San Benito, there is one commercial health plan available to beneficiaries.

Governor’s Budget Caseload Projections

According to the Medi–Cal Eligibility Data System, there were over 12 million people enrolled in Medi–Cal as of September 2015. This count includes over 3 million enrollees—mostly childless adults—who became newly eligible for Medi–Cal under the optional expansion. A substantial number of families and children who were previously eligible—known as the mandatory expansion—are also assumed to have enrolled as a result of eligibility simplification, enhanced outreach, and other provisions and effects of the ACA. The Governor’s budget assumes that following the large influx of enrollees in 2014–15 and 2015–16, ACA–related caseload levels will stabilize during 2016–17. The budget also assumes modest underlying growth for baseline enrollment within the families and children and SPD populations.

Historical Trends. Figure 1 displays a decade of observed and estimated caseload for each major category of enrollment in Medi–Cal, beginning with (1) historical caseload through 2013–14, followed by (2) the administration’s revised estimate for caseload in 2014–15, and (3) the budget’s projections for 2015–16 and 2016–17. While SPD enrollment grew steadily at about 2 percent annually throughout the historical period, the families and children caseload grew cumulatively by 15 percent (or an average annual growth of about 4 percent) between 2007–08 and 2010–11 (the onset of the Great Recession through the sluggish phase of the recovery). The further uptick in families and children in 2013–14 reflects the shift of the Healthy Families Program (HFP) to Medi–Cal. Further growth in the families and children population after 2014–15 largely reflects the impact of the ACA.

Caseload Projections in Governor’s Budget. The Governor’s budget assumes total annual Medi–Cal caseload of 13.3 million for 2015–16. This is an 8 percent increase over the revised caseload estimate of 12.3 million for 2014–15. This substantial year–over–year increase reflects, at least in part, continued growth related to the ACA. The budget assumes total annual Medi–Cal caseload of 13.5 million for 2016–17, an increase of 2 percent over revised 2015–16 caseload. Of the 13.5 million assumed beneficiaries, 3 million enrollees are projected to have gained eligibility through the ACA optional expansion.

Administration’s Caseload Projections Appear Reasonable. We have reviewed the administration’s caseload projections in the context of the substantial ACA–related changes to the Medi–Cal caseload in recent years, and we find the estimates to be reasonable. We note, however, these ACA–related changes have made it more difficult to project caseload. We discuss these ACA–related impacts in more detail in the next section. Further, if we receive additional information that causes us to change our assessment of the caseload projections in the Governor’s budget, we will provide the Legislature with an updated analysis at the time of the May Revision.

ACA Implementation Creates Substantial Uncertainty in Projecting Caseload

There have been number of ACA–related impacts on Medi–Cal caseload that make it difficult to use trends in historical caseload data from recent years to project future caseload. This is because the initial impacts of ACA implementation on caseload are unlikely to continue in future years. For example, the large influx in Medi–Cal caseload over the past two years associated with the ACA’s optional and mandatory expansions is unlikely to continue in future years as many of those eligible have already enrolled.

Background

Medi–Cal Caseload Changes Are a Function of Inflows and Outflows. Medi–Cal caseload is both a function of inflows (new enrollees coming onto the program) and outflows (existing enrollees leaving the program due to ineligibility or because they obtained other health coverage). Taken together, inflows minus outflows equate to the net change in caseload. It is therefore important that historical caseload data accurately capture both inflows and outflows in order to use such data to project future caseload levels.

Impacts of ACA on Medi–Cal Caseload Inflows

Several ACA–related changes have resulted in an increase in Medi–Cal enrollment (or inflows of Medi–Cal caseload), including eligibility expansions, outreach efforts, and enrollment simplifications.

Increased Enrollment Associated With ACA. Through the ACA’s optional expansion, California expanded Medi–Cal eligibility as of January 1, 2014 to include previously ineligible adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). As shown in Figure 1, the optional expansion resulted in a significant influx of new enrollees into Medi–Cal. In addition to the increase in Medi–Cal enrollment associated with the optional expansion, several other ACA–related factors—such as enrollment simplification, publicity, and outreach—likely increased Medi–Cal enrollment among individuals who were previously eligible, but unenrolled—often referred to as the mandatory expansion.

ACA Changes Likely Made It Easier to Enroll in Medi–Cal. Several ACA–related policy changes have likely made it easier to enroll in Medi–Cal coverage and therefore have likely resulted in increased Medi–Cal caseload. The state adopted a no–wrong–door approach for Medi–Cal applications that allows applicants to apply: (1) online through Covered California’s website, (2) by calling either Covered California’s service center or county Medi–Cal eligibility offices, (3) in person at county Medi–Cal eligibility offices, or (4) through the mail. The state has also taken advantage of other options under the ACA to streamline the enrollment process, including hospital presumptive eligibility and express lane enrollment. Both are streamlined processes that allow certain individuals to enroll in Medi–Cal without completing a full application.

Impacts of ACA on Medi–Cal Caseload Outflows

Several ACA–related impacts have affected the Medi–Cal redetermination process (a check of Medi–Cal eligibility necessary to allow continued enrollment in the program that generally occurs annually during the month in which the beneficiary initially enrolled), which affects Medi–Cal caseload outflows.

While ACA Simplified Some Annual Redeterminations . . . The ACA and state legislation created a new annual redetermination process that reduces the amount of information that must be provided by beneficiaries and, instead, relies on available electronic data. This results in the ability for county eligibility workers to complete a given beneficiary’s annual redetermination without contacting the beneficiary for information if the available electronic data are sufficient to confirm eligibility.

. . . ACA Implementation Workload Created Delay in Medi–Cal Redeterminations. Counties experienced an increase in workload associated with processing Medi–Cal applications as a result of (1) the large influx of Medi–Cal applications resulting from the ACA’s coverage expansion and increased outreach efforts and (2) issues with functionality in the California Health Eligiblity, Enrollment, and Retention System (CalHEERS) that created the need for county eligibility workers to manually complete some steps of Medi–Cal eligibility processes. (CalHEERS is a central automation system, jointly administered by Covered California and DHCS, that allows for real–time eligibility determinations both for Medi–Cal and subsidized coverage through Covered California.) As a result of this workload, DHCS allowed counties to delay the processing of Medi–Cal redeterminations. According to DHCS, counties were advised to delay all redeterminations for the first six months of 2014 and to conduct a modified redeterminations process during the last six months of 2014.

Beginning in 2015, DHCS had the expectation that counties would be conducting full redeterminations in a timely manner. We understand from discussions with counties that not all redeterminations were processed on time in 2015 as a result of continued work associated with ACA implementation and ongoing issues with CalHEERS. While comprehensive data are not available to fully assess the extent of this problem, the data that are available indicate that counties have processed roughly 75 percent of redeterminations due between January 2015 and September 2015.

Ongoing Work Aimed at Addressing CalHEERS Issues and Redeterminations Delay. In the past several years, the Medi–Cal budget has included additional funding for county workload associated with initial implementation of ACA. The Governor’s budget includes an additional $85 million General Fund ($170 million total funds) in 2016–17 for this purpose. From conversations with counties, we understand counties are continuing to get caught up on processing redeterminations on a more timely basis in recent months. Further, work continues to implement additional functionality and resolve outstanding issues in CalHEERS. The administration, with input from counties and other stakeholders, has created a rolling 24–month roadmap that provides a timeline for reaching full functionality of CalHEERS.

ACA Impacts on Projecting Medi–Cal Caseload

ACA–related policy changes have impacted both inflows and outflows of Medi–Cal enrollment in recent years, creating difficulties in the use of historical caseload data to project future caseload levels.

Influx of Caseload Associated With ACA Distorts Underlying Caseload Trends. Typically, our office projects families and children caseload by evaluating historical trends in how caseload changes as a result of changes in the economy. Based on historical trends, we would typically expect caseload to decrease during the recent period of economic expansion absent other policy changes. However, ACA–related policy changes during this period have significantly increased Medi–Cal caseload. The caseload inflows during initial implementation of the ACA coverage expansion represent an initial increase associated with the expanded eligibility and outreach efforts. However, the growth rates experienced during this implementation phase are not trends that we would expect to continue over time. Therefore, the last several years of historical Medi–Cal caseload data are generally not useful for projecting future trends in caseload for several reasons: (1) it is difficult to project exactly when the increase in caseload will slow down and (2) the increase in caseload masks how caseload otherwise would have changed as a result of the economic expansion that has occurred in recent years.

Delay in Medi–Cal Redeterminations Distorts Underlying Caseload Trends. Outflows of caseload from the past several years are distorted by the delays in processing Medi–Cal redeterminations. The redetermination delays have resulted in some enrollees retaining Medi–Cal coverage longer than they otherwise would have if redeterminations had been processed on time. The delay in redeterminations also prevent us from understanding how the outflows of Medi–Cal caseload have changed as a result of the simplification of redeterminations as a result of ACA–related policy changes. Further, these factors complicate the understanding of outflows of caseload associated with changes in the economy.

Future Medi–Cal Caseload Difficult to Project Given Distortions in Recent Historical Data. Together, the ACA’s coverage expansion and recent redetermination delays limit the use of the trends in the most recent caseload data in projecting future caseload. The best data available to understand trends in Medi–Cal caseload are historical data from the years prior to the ACA, and both our office and the administration have looked to this data in projecting Medi–Cal caseload. However, these historical trends may not be reflective of caseload trends that will continue going forward because the ACA significantly changed the Medi–Cal coverage landscape. Once the initial influx of ACA–related caseload is complete and delays in Medi–Cal redeterminations are resolved, it will take several years before the state has sufficient data to understand underlying caseload trends.

Legislature Should Consider Caseload Projection Uncertainty When Budgeting

Early in the roll–out of the ACA there was understandably a focus on getting individuals enrolled in Medi–Cal. As we move out of the initial implementation phases of the ACA, the focus shifts more towards continued implementation of CalHEERS functionality, the timely processing of redeterminations, and more accurate tracking of caseload. As the initial changes associated with ACA implementation stabilize, caseload data will become more useful for projecting future caseload from recent historical trends. However, until that time, both the administration’s and our office’s caseload projections are likely to be more uncertain than in the past.

Legislature Should Consider Caseload Uncertainty When Making Budgetary Decisions. It is important for the Legislature to be aware of this uncertainty in evaluating Medi–Cal caseload particularly in the out years. When making budgetary decisions, the Legislature should consider this uncertainty with the understanding that small changes (both increases and decreases) in Medi–Cal caseload can have large impacts on the Medi–Cal budget. For example, even 200,000 more family and children beneficiaries enrolled in Medi–Cal than projected could result in additional General Fund costs in the low hundreds of millions of dollars. To the extent the Legislature is risk averse, the Legislature may want to account for the potential increases in the Medi–Cal budget as a result of caseload uncertainty in determining the targeted level of General Fund reserves.

Require DHCS to Report at Budget Hearings on Caseload and Redeterminations. As time goes on and the initial phases of ACA implementation are complete, trends in historical caseload data and their relationship to the economy will become more useful in projecting future caseload. Given this, we recommend the Legislature require DHCS to report at May Revise hearings on how the most recent data on caseload and redeterminations have informed and changed caseload projections.

Potential General Fund Cost Pressures on the Horizon

Introduction

Medi–Cal is a complex and dynamic program that at any given time is subject to potential changes resulting from economic or policy shifts. These changes can range from economically driven caseload changes to policy and programmatic changes such as coverage expansions, the addition of new health care benefits, and delivery system reforms. These types of changes typically have fiscal impacts on the state’s budget.

Beginning in 2016–17 and over the next several years, there are potentially several major changes that could occur in the Medi–Cal program and potentially result in increased General Fund costs as high as the low billions of dollars annually in total. Some of these changes are relatively certain to occur, such as the phase–in of the state’s share of cost for the ACA optional expansion population. Other potential changes, such as proposed changes to the federal government’s Medicaid managed care regulations, are still very uncertain but could result in significant General Fund costs.

While some of these potential General Fund cost pressures would not occur during 2016–17, but rather in future fiscal years, the Legislature can use this information when weighing priorities for new ongoing spending proposals and reserve levels. Further, awareness of these cost pressures may inform other policy decisions the Legislature is considering, including whether to pass a restructured MCO tax.

Hospital QAF Sunset

Background. Federal Medicaid regulations allow states to assess “health care–related taxes” on certain health care providers and use the tax revenues as the nonfederal share of Medicaid payments. Since 2009, the Legislature has imposed a health care–related tax, the hospital QAF, on certain private hospitals. The hospital QAF benefits the hospital industry through the use of fee revenue to draw down federal funds that are generally provided to hospitals through various financing mechanisms. Most of the revenues collected through the fee provide the nonfederal share of (1) certain increases to capitation payments that Medi–Cal managed care plans are required to pass along entirely to private and public hospitals and (2) certain supplemental payments to private hospitals. A certain portion of the fee revenue offsets General Fund costs for providing children’s health care coverage, thereby achieving General Fund savings. In 2015–16, General Fund savings from the fee are estimated to be $815 million.

Fee Sunsets January 1, 2017 and Governor’s Budget Does Not Propose Fee Extension. The current hospital QAF sunsets on January 1, 2017. The Governor’s budget does not propose extending the fee. A November 2016 ballot measure, however, would permanently extend the fee if passed. An extension of the fee requires both legislative (or voter) approval and subsequent approval from the federal government to draw down federal funds.

Given Timing of Federal Review, Fee Extension Unlikely to Impact Budget in 2016–17 . . . In order to have an extension of the fee in effect retroactive to January 1, 2017, the state would need to formally submit the proposed fee extension for approval from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) by no later than March 31, 2017. (The federal government would likely allow the fee to be retroactive to the beginning of the quarter in which the fee is submitted to it for approval.) However, prior to submitting for federal approval, the Legislature (or voters) must first authorize an extension of the fee. Once a fee extension is formally submitted to CMS, the administration estimates it would take CMS 6 to 12 months to approve the fee extension. The fee would likely be retroactive to January 1, 2017, but the length of time for CMS approval would create a delay in receiving General Fund benefit from the fee until 2017–18.

. . . But Delay in Authorizing Fee Extension Would Likely Result in Lost General Fund Savings. If the state submitted the proposed extension to CMS for approval after March 31, 2017, there would likely be a gap between the sunset of the current fee and the effective date of the extended fee during which time the state would not receive General Fund benefit from the fee. The magnitude of the General Fund impact would vary based on the duration of time between the current fee’s sunset and the extended fee’s effective date. For example, if the fee was not in effect for one quarter, this could result in General Fund costs in the low hundreds of millions of dollars.

Proposed Medicaid Managed Care Regulations

Background. The CMS recently proposed broad and sweeping changes to the federal regulations that govern managed care in Medicaid. These regulations were submitted for public comment in June 2015 and are expected to be finalized in 2016. This is the first time CMS has updated the managed care regulations since 2002 and, according to CMS, the regulations were proposed to respond to substantial changes in the delivery of health care services. One example of such changes includes the significant increase in managed care enrollment. In 2003–04, only 50 percent of Medi–Cal enrollees were enrolled in managed care. In 2016–17, 75 percent of Medi–Cal beneficiaries are projected to be enrolled in managed care.

If the proposed regulations were adopted by CMS in their current form, there would be several potential adverse General Fund impacts. In this report, we focus on potential impacts of the regulations that, based our current understanding, could result in significant General Fund impacts. However, the proposed regulations could also result in many other changes to how Medi–Cal is administered. A discussion of such changes is beyond the scope of this report.

Regulations as Proposed Would Impact Medi–Cal Financing Structure. The proposed managed care regulations would restrict the state’s flexibility in paying managed care plans in two key ways:

- Restriction on Directing Managed Care Plan Payments. Currently, the state directs managed care plans to pass on certain payments to specified providers, such as payments to hospitals through the hospital QAF. The proposed regulations would generally prohibit the state from directing managed care plan expenditures. This could mean the state would not be able to require managed care plans to use specified portions of capitated rate payments to support specific health care providers.

- Elimination of Managed Care Rate Range. The state generally contracts with actuaries (rate–setting professionals) to determine the appropriate capitated rates to pay Medi–Cal managed care plans. The actuaries determine the appropriate rates in accordance with current federal regulations, which generally require plans to be reimbursed for the reasonable costs of providing health care services covered by Medi–Cal to the population served by the plan. Currently, the actuaries certify to a range of capitated rates for each Medi–Cal managed care plan. DHCS then pays plans a capitated rate that falls within the rate range. In general, the state pays at the lower end of the rate range. Under the proposed managed care regulations, CMS would require actuaries to certify to a specific rate for a given plan instead of a range.

Below, we discuss the potential impact on the General Fund as a result of the potential restrictions the proposed regulations would place on how the state pays managed care plans.

General Fund Savings From Hospital QAF Could Be Compromised. As discussed above, a key feature of the hospital QAF is the use of fee revenue to increase capitation payments to managed care plans. The plans are then required to pass along these capitation increases entirely to private hospitals, county hospitals, and University of California hospitals. If the proposed regulations prevented the state from directing managed care plan payments, then the state would likely not be able to require the capitation increases to be passed on to hospitals. As such, the state would likely be unable to continue the hospital QAF as currently structured and this could compromise the General Fund benefit from the fee.

General Fund Offset From Health Realignment Savings Could Be Reduced. Counties pay for indigent health care using 1991 health realignment funding. Under ACA, counties experience savings from providing less indigent health care, because many previously uninsured individuals enrolled in Medi–Cal. In light of this, counties are required under current law to use a portion of health realignment funding to help pay for California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) grants, which offsets General Fund spending that otherwise would have occurred in CalWORKs. In counties that operate public hospitals, realignment savings are determined through a formula that includes a comparison of the public hospitals’ total revenues and total costs.

The proposed restriction on directing managed care plan payments and the proposed elimination of the managed care rate range could result in less revenue for public hospitals and other safety–net providers. For example, certain financing mechanisms pay managed care plans above the lower end of the rate range and require plans to pass along these payments above the lower end of the rate range to public hospitals. If as a result of the proposed regulations public hospitals receive less revenue, this in turn could reduce the amount of health realignment funds redirected to CalWORKs to offset General Fund costs for CalWORKs grants. The administration estimates the General Fund offset in CalWORKs will be $560 million in 2016–17 (excluding costs associated with truing–up the redirection of health realignment from 2013–14). To the extent the regulations impact public hospital financing, these savings could be reduced.

Potential Reductions in Federal Funding Received by Safety–Net Providers Could Create General Fund Pressure. There is potential for the proposed managed care regulations to result in a reduction of federal funding to public hospitals and other safety–net providers through the hospital QAF and other Medi–Cal financing mechanisms that could potentially be prohibited under the proposed regulations. This could destabilize the safety net and could result in pressure on the General Fund to replace some of the lost federal funds.

Section 1115 Waiver

Background. The federal government grants states flexibility in administering their Medicaid programs through “waivers,” such as those allowed under Section 1115 of the federal Social Security Act. When a state’s waiver request is approved by the federal government, the state is permitted to waive certain federal requirements on the basis that the waiver serves to further the purpose of the state’s Medicaid program. Certain waivers can allow states to leverage federal funding. The state recently received federal approval for a new Section 1115 waiver called the “Medi–Cal 2020” waiver. The waiver, which began January 1, 2016, will provide the state with at least $6.2 billion in federal funds over the next five years.

Uncertain Safety Net Care Pool (SNCP) Funding Through Waiver. Under the Medi–Cal 2020 waiver, CMS has only agreed to provide certain funds referred to as SNCP funds for the first year of the waiver. These funds currently provide roughly $230 million annually to public hospitals for the provision of uncompensated care. CMS expects the amount of uncompensated care provided by public hospitals to have decreased as a result of the ACA’s coverage expansions and as such has required the state to conduct a study of uncompensated care. The study will inform CMS’s decision on the amount of SNCP funding to provide in subsequent years of the Medi–Cal 2020 waiver. In general, we understand CMS has the expectation that the amount of SNCP funding will decrease in subsequent years as a result of an expected decrease in the need for uncompensated care. In addition to requiring the study of uncompensated care, CMS has indicated it expects public hospitals to be self–sustaining absent SNCP funding by 2020.

Reduced SNCP Funding Would Likely Decrease General Fund Offset From Health Realignment Savings. If SNCP funding were to decrease in subsequent years of the Medi–Cal 2020 waiver, this would decrease funding to public hospitals. All else equal, this would likely decrease the amount of health realignment funding counties that operate public hospitals would be required to redirect to CalWORKs. This in turn would decrease the General Fund offset in CalWORKs.

ACA Optional Expansion

Background. Currently, the federal government pays 100 percent of the costs for the over 3 million Medi–Cal enrollees who became eligible through the ACA’s optional expansion (largely low–income, childless adults). Beginning in 2017, the state will pay 5 percent of these costs, phasing up to 10 percent in 2020 and thereafter. However, the state has paid some costs associated with the optional expansion since the expansion began in 2014. These costs occur as a result of a state–only Medi–Cal program that provides full–scope Medi–Cal to certain newly qualified immigrants. The state does not receive a federal match for the costs of these benefits with the exception of emergency and pregnancy services. State law requires that legal immigrants receive the same services as citizens and as such, eligibility for this program was expanded consistent with the ACA’s coverage expansion. Beginning in 2017, this population is expected to transition from Medi–Cal coverage to coverage through Covered California through which they are eligible for federally funded premium subsidies. Medi–Cal will still pay for premiums (above the federally subsidized amount), cost–sharing, and services that are not covered through Covered California but are covered through Medi–Cal—also known as wrap–around coverage.

Administration Estimates Optional Expansion Will Cost $550 Million General Fund in 2016–17, but Only $385 Million Associated With 5 Percent Cost Phase–In. The administration estimates the optional expansion will cost about $550 million General Fund in 2016–17. However, these costs can be grouped into two categories.

- Optional Expansion Costs Associated With 5 Percent State Cost Share. Only $385 million of the $550 million in optional expansion costs are associated with the state paying 5 percent of the optional expansion costs for half of the year.

- Newly Qualified Immigrant Optional Expansion–Related Costs. The remaining $165 million is associated with the cost of providing full–scope Medi–Cal to newly qualified immigrants who are eligible through the state–only program that was expanded consistent with the optional expansion.

This distinction between these two categories of costs is important in understanding how costs associated with the optional expansion will increase as the state’s share of cost increases to 10 percent. The $385 million General Fund represents the baseline cost of the optional expansion during the first six months of 2017 when the state is first required to pay 5 percent of the optional expansion costs. It is therefore this amount (annualized to cover a full fiscal year) that will increase as the state’s share of cost for the optional expansion increases to 10 percent by 2020–21. The state’s costs associated with newly qualified immigrants will decrease when this population transitions to coverage through Covered California in 2017.

General Fund Costs Associated With Optional Expansion Cost Share Could Reach $1.4 Billion to $1.9 Billion by 2020–21. We estimate the General Fund costs associated with the optional expansion are likely to be between $1.4 billion and $1.9 billion by 2020–21, when the state is paying 10 percent of the costs. This range reflects the considerable uncertainty associated with estimating costs several years out for this population. The majority of the optional expansion population will be enrolled in Medi–Cal managed care plans that receive a capitated rate per enrollee per month regardless of the number of services an enrollee receives. The rates paid to managed care plans for optional expansion enrollees have decreased relative to the rates plans were paid at the beginning of the Medi–Cal expansion because this population was less costly than originally estimated. If this trend continues, costs would likely be at the low end of this range. On the other hand, costs would likely be at the higher end of this range if, for example, caseload increased as a result of a recession.

Children’s Health Insurance Program

Background. CHIP is a joint federal–state program that provides health coverage to children in low–income families, but with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid. States have the option to use federal CHIP funds to create a stand–alone CHIP program or to expand their Medicaid programs to include children in families with higher incomes (commonly referred to as Medicaid–expansion CHIP). Recently, California transitioned from providing CHIP coverage through the stand–alone HFP to providing CHIP coverage through Medi–Cal. With this transition, completed in the fall of 2013, Medi–Cal generally provides coverage to children in families with incomes up to 266 percent of the FPL. Some infants in families with incomes up to 322 percent of the FPL may also be eligible for Medi–Cal. (The FPL in 2016 for a family of four is $24,300.)

Unlike Medi–Cal, CHIP is not an entitlement program. States receive annual allotments of CHIP funding based on historic CHIP spending. Generally, states receive allotments that are sufficient to cover the federal share of CHIP expenditures for the full year. Allotments correspond to the federal fiscal year (FFY) which runs from October 1 through September 30.

Enhanced ACA Federal Funding Reduces General Fund Costs by Over $600 Million Annually. Beginning October 1, 2015, California’s CHIP federal matching rate increased from 65 percent to 88 percent as authorized by ACA. The administration estimates the increased matching rate will result in $600 million in General Fund savings in 2016–17.

Uncertainty as to Whether CHIP Will Be Funded After FFY 2016–17. Congress has appropriated funding for CHIP through FFY 2016–17, which ends on September 30, 2017. Therefore, Congress will face a decision as to whether to fund CHIP beyond FFY 2016–17. If Congress does not fund CHIP beyond FFY 2016–17, the state could continue to provide coverage to this population through Medi–Cal and would receive the 50 percent Medi–Cal matching rate. This would result in General Fund costs of roughly one billion dollars on an annual basis.

If CHIP Is Funded, Enhanced Matching Rate Authorized Only Through FFY 2018–19. Assuming Congress funds CHIP beyond FFY 2016–17, the enhanced matching rate is only authorized by the ACA through FFY 2018–19, which ends on September 30, 2019. After such time, the federal cost share would revert to the 65 percent CHIP matching rate absent additional action by Congress. Therefore, the roughly $600 million in annual General Fund savings from the enhanced matching rate is likely time–limited.

Recommendations

Extend Hospital QAF. We recommend the Legislature extend the hospital QAF because this fee is both a benefit to the General Fund and the hospital industry. Further, we recommend the Legislature extend the fee this legislative session to provide greater assurance that the fee’s benefit in drawing down federal funds is maximized by preventing a lapse in the fee being operative. While there is a ballot initiative that would make the fee permanent, a delay in authorizing the fee could result in General Fund costs of at least the low hundreds of millions of dollars. We also note the proposed managed care regulations in their current form could prevent the fee from being implemented as currently structured. However, the regulations are not yet finalized and it is possible the fee could be implemented under the finalized regulations. Therefore, we find the Legislature should move forward with authorizing a fee extension to maximize potential General Fund benefit.

Consider Potential General Fund Pressures When Making Policy and Budgetary Decisions. We recommend the Legislature consider these General Fund pressures in Medi–Cal when making policy and budgetary decisions. These cost pressures may inform legislative decisions related to ongoing spending commitments and building up reserves as the Legislature crafts the 2016–17 budget. Further, some of the Legislature’s decisions on policy issues during this legislative session should be made in consideration of these cost pressures.