In This Report

LAO CONTACTS

Higher Education in Context,

Hastings College of the Law,

California Student Aid Commission

University of California,

California State University

California Community Colleges

February 26, 2016

The 2016-17 Budget

Higher Education Analysis

Executive Summary

Overview

Under Governor’s Budget, Total Funding for Higher Education Reaches $48.2 Billion. Accounting for funds from all sources, the Governor’s budget includes $48.2 billion for higher education in 2016–17, an increase of $1.4 billion (3 percent) from the revised 2015–16 level. This funding primarily supports the University of California (UC), the California State University (CSU), the California Community Colleges (CCC) and the California Student Aid Commission. Though many fund sources help support higher education, the main fund sources for undergraduate and graduate education are state General Fund, student tuition revenue, and, at CCC, local property tax revenue. These fund sources for UC, CSU, and CCC combined grow from $20.7 billion in 2015–16 to $21.6 billion in 2016–17, an increase of $916 million (4 percent). The Governor assumes tuition charges for resident students at each segment remain flat.

Governor’s Budget Contains a Few Proposals for UC and CSU, Many for CCC. The Governor’s budget increases state General Fund for UC and CSU each from $3.3 billion to $3.5 billion. These proposed increases include ongoing unrestricted base increases for UC ($125 million, 4 percent) and CSU ($148 million, 5 percent), one–time funding of $171 million for paying down a portion of UC’s unfunded pension liability, and one–time funding of $35 million each for UC and CSU deferred maintenance. For CCC, the Governor’s budget increases Proposition 98 funding to $8.3 billion, an increase of $262 million (3 percent) from the revised current–year level. The Governor’s budget increases CCC apportionments by $115 million to fund 2 percent enrollment growth and augments various categorical programs, most notably, providing $200 million for a new program to expand access to career technical education (CTE) and $30 million to revamp the existing Basic Skills Initiative. The Governor provides $290 million for CCC deferred maintenance and instructional support.

Key Messages

Recommend Linking UC and CSU Funding Increases With Legislative Priorities. Under the Governor’s budget, UC and CSU would have significant discretion over their ongoing budget augmentations. We recommend the Legislature review the expenditure plans that UC and CSU have developed to determine if they conform with legislative priorities. We further recommend the Legislature designate funding in the state budget for areas it deems high priorities.

Recommend Legislature Continue Enrollment–Based Budgeting. The Governor’s budget does not set enrollment targets for UC and CSU. Though the state has been inconsistent in recent years in setting enrollment targets, it set targets last year. In doing so, it took a new approach by setting expectations for one year after the budget year. This was an effort to better align state budget decisions with UC’s and CSU’s admission decisions. We recommend the Legislature use the same approach in crafting this year’s budget. Specifically, if the Legislature desires to fund enrollment growth, we recommend it (1) set a target for 2017–18 and (2) schedule any associated enrollment funding for 2017–18 in this year’s trailer legislation. For CCC, we believe the proposed enrollment growth rate is somewhat high given recent enrollment trends. We recommend the Legislature revisit the issue in May, at which time it will have updated information about current–year enrollment.

Recommend Modifying CCC Workforce Proposals. We recommend the Legislature create a new workforce program, as the Governor proposes, but better structure it to address the high costs of certain CTE programs. Under the modified program, CCC would have ongoing funding streams for (1) equipment and other one–time costs and (2) programs with exceptionally high ongoing costs (typically due to faculty and class–size requirements). We also recommend the Legislature fold into this new program an existing supplemental funding program for nursing education and any CCC projects the Legislature desires to maintain from the CTE Pathways Program. In addition, we recommend consolidating planning processes so that colleges are not required to create parallel regional plans for adult education, CTE, and other workforce–related programs.

Recommend Learning From Efforts Now Underway Before Augmenting Basic Skills Initiative. We believe the Governor’s proposed augmentation is premature. Last year, the state funded two new grant programs intended to improve basic skills practices. The state required evaluations of both programs, with the results of the evaluations due in a few years. We recommend the Legislature learn more about the outcomes of these programs before augmenting the Basic Skills Initiative. In 2016–17, the Legislature could redirect the proposed funding to allow more colleges to participate in one of the two grant programs created last year or use the funds for other one–time priorities.

Recommend Working With Segments to Improve Budgeting of Maintenance. For decades, the state has had difficulty getting clear, reliable information about each segment’s annual maintenance spending and maintenance backlog. Given this longstanding challenge, coupled with the size and complexity of the segments’ capital programs, we believe the Legislature should begin exploring new ways of budgeting for maintenance. The Legislature could work with the segments to develop reasonable estimates of the amount of annual spending required to keep their backlogs from growing. Once it has made reasonable estimates of these amounts, the Legislature could consider earmarking funding in the annual budget. In tandem with developing these earmarks, the state could work with the segments to develop plans for eliminating their existing maintenance backlogs. These plans should identify funding sources and propose a multiyear schedule of payments. Once reasonable plans have been developed, the Legislature could consider including them in trailer legislation. Given their backlogs are substantial, developing these plans likely would take time, such that if the Legislature were to begin this work now it could help inform next year’s budget.

Recommend Directing UC and CSU to Provide More Information About Some of Their Proposals at Spring Budget Hearings. We recommend that UC provide additional information on its plans for (1) changing its pension benefits, (2) expanding graduate enrollment, and (3) providing general purpose monies to campuses to boost academic quality. We also recommend the Legislature direct CSU to provide additional information at spring budget hearings on its plans for student success initiatives and capital outlay.

Introduction

In this report, we analyze the Governor’s proposed budget for higher education. We begin by providing background on three areas of higher education: enrollment, tuition and financial aid, and performance. In the next five sections, we analyze the Governor’s budget proposals for (1) the University of California (UC), (2) the California State University (CSU), (3) the California Community Colleges (CCC), (4) Hastings College of the Law, and (5) the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC). In each of these sections, we provide relevant background, describe the proposals, provide an assessment, and make recommendations. The final section consists of a summary of the recommendations we make throughout the report. Various additional higher education budget tables not included in this report may be accessed from the Education page of our website.

Higher Education in Context

This section provides background on key aspects of the state’s higher education system. We begin with an overview of the state’s public and private institutions. Next, we present information on public higher education enrollment, tuition and financial aid, and institutional and student performance. In cases where data is available, we provide perspective on how California’s public higher education system compares to other states. Throughout this section, we cite the most recent data available from government sources. In some cases, particularly for national comparison data, the most recent data may be several years old.

Overview of Higher Education

Higher Education in California Delivered by Public and Private Institutions. The Master Plan for Higher Education in California sets forth the missions of the state’s three public segments. In addition to public higher education, California has a private sector consisting of many nonprofit and for–profit colleges and universities. Figure 1 provides basic information about each segment and sector.

Key Issues in Higher Education in California. The state in recent years has focused primarily on three main areas of higher education: access, affordability, and performance. The state’s longstanding interest in access is to ensure that its residents have the opportunity to attend higher education. The state also has had a longstanding interest in ensuring that higher education is affordable for those residents choosing to attend. In more recent years, the state has taken a heightened interest in a number of performance measures, including whether students complete their studies on time. The remainder of this section addresses each of these areas by providing context on enrollment, tuition and financial aid, and performance in California’s public higher education system.

Enrollment

Below, we discuss higher education eligibility policies, enrollment demand, enrollment funding, enrollment trends, and nonresident enrollment.

Eligibility Policies

1960 Master Plan Differentiates Among the Three Segments. The state’s Master Plan establishes different eligibility requirements for each of the three higher education segments. Under the Master Plan, any student may enroll in the CCC system. The CCC system has the broadest level of access both because it (1) has the broadest mission (including vocational training leading to certificates and credentials, adult education, and instruction leading to associate degrees and transfer) and (2) is the least expensive per student. In contrast, both university systems set admission criteria because (1) their missions are more narrowly focused on undergraduate and graduate education and (2) they are more expensive per student. Between the university systems, UC has the most rigorous admission criteria and the highest cost. Though the Master Plan does not explicitly assign areas of service to each of the three systems, the state typically views UC as a statewide system, CSU as a regional system, and CCC as a system of local campuses. (The state did not include Hastings in the Master Plan, nor has the state otherwise specified an eligibility policy for Hastings.)

All Adult Californians May Attend Community Colleges. The CCC system is known as an “open access” system because it is available to all Californians 18 years or older. The CCC system has no admission criteria, such as grades or previous course–taking, to screen out or select certain students. (While CCC does not deny admission to students, it also does not guarantee access to particular classes and some classes may set prerequisites.)

Master Plan Sets Freshman Eligibility Pools at UC and CSU. The Master Plan calls for UC to draw its incoming freshman class from the top 12.5 percent (one–eighth) of public high school graduates. It calls for CSU to draw its applicant pool from the top 33 percent (one–third) of public high school graduates. The Master Plan allows the universities to admit resident private high school graduates and nonresident students if these applicants meet similar academic standards as eligible public high school graduates.

Universities Supposed to Align Admission Policies With Freshman Eligibility Pools. Both UC and CSU require freshman applicants to complete a set of high school coursework known as “A through G” (A–G) that includes English, history, math, and science courses. These coursework requirements are intended to help prepare students for college–level work. In 2013–14, 42 percent of public high school graduates had successfully completed A–G coursework. In addition to completing A–G coursework, UC and CSU have other admission criteria, including requiring certain test scores and grade point averages (GPAs), they use to select students from within their respective eligibility pools. (UC and CSU also admit some freshmen who do not meet these criteria. The Master Plan calls for UC and CSU to limit such special admissions to no more than 2 percent of all freshman admissions.)

Available Evidence Suggests UC and CSU Drawing From Beyond Their Freshman Eligibility Pools. For fall 2014, UC and CSU admitted 13 percent and 30 percent, respectively, of public high school graduates as freshmen. Had CSU also admitted an additional 17,500 freshman applicants who met CSU’s admission criteria but whom the university system turned away, it would have admitted 34 percent of all public high school graduates. Because not all public high school students within the eligibility pools apply to UC or CSU, and many only apply to UC or CSU but not both, the universities currently are drawing from even larger pools of students.

State Currently Conducting Freshman Eligibility Study to Obtain Better Data. Over the last several decades, the state has conducted studies periodically to determine the proportion of public high school graduates eligible for admission to UC and CSU as freshmen. As part of these studies, UC and CSU admission counselors examined a sample of public high school transcripts and determined the number of students the universities would have admitted had all students applied. Chapter 324 of 2015 (SB 103, Committee on Budget) directs the Office of Planning and Research to complete such a study by December 1, 2016.

Master Plan Establishes Minimum Qualifications for Students Transferring to UC and CSU. The Master Plan calls for UC and CSU to accept qualified transfer students who complete 60 units of transferrable credit at a community college and meet minimum GPA requirements (2.4 for UC and 2.0 for CSU). The Master Plan also calls on UC and CSU to maintain at least 60 percent of their total enrollment as upper–division to allow room for transfer students (who typically transfer as juniors). To achieve this target, the universities typically aim to admit one transfer student for every two freshmen. Though not part of the Master Plan, recent legislation—Chapter 428 of 2010 (SB 1440, Padilla)—also requires CSU to accept applicants who earn “associate degrees for transfer” from the community colleges.

For Fall 2014, UC Admitting All Eligible Transfer Students, CSU Denying Admission to 13 Percent. Unlike for freshmen, the universities themselves are able to track whether they are admitting all eligible transfer students. This is because the Master Plan sets the minimum admission standards for transfer students, rather than establishing an eligibility pool as for freshmen. UC has been admitting all eligible transfer students for many years. CSU has not been admitting all eligible transfer students the past few years. It asserts that part of the reason it recently has been unable to accommodate all eligible transfer students is due to inadequate state funding.

Master Plan Does Not Include Eligibility Criteria for Graduate Students. Instead, the Master Plan calls for the universities to consider graduate enrollment in light of workforce needs, such as for college professors and physicians.

Master Plan Eligibility Policies Last Reviewed in 2010. Over the last several decades, the Legislature has periodically revisited the Master Plan’s provisions, doing so most recently in 2010. To date, the Legislature has not modified any of the original Master Plan eligibility policies. In recent years, however, the Legislature has taken an interest in access to particular campuses at UC, even though the Master Plan establishes eligibility on a systemwide basis.

Enrollment Demand

Demographic Changes Affect Enrollment Demand. Other factors being equal, an increase in the number of California public high school graduates causes a proportionate increase in the number of students eligible to enter UC and CSU as freshmen. Similarly, increases in the state’s traditional college–age population (18– to 24–year olds) generally correspond with increases in UC and CSU eligible students. In 2013–14, more than 90 percent of UC undergraduates and about 80 percent of CSU undergraduates were in this age group. The CCC system enrolls students from a broader age range, with 57 percent of its students being under the age of 24. Its enrollment is affected by changes in both the college–age population and the overall adult population in California.

College Participation Rates Another Factor in Enrollment Demand. For any subgroup (for example, the traditional college–age group), the percentage of individuals who are enrolled in college is that subgroup’s college participation rate. Other factors remaining constant, if participation rates increase (or decrease), then enrollment demand increases (or decreases). Participation rates can change due to a number of factors, including student fee levels, availability of financial aid, state and institutional efforts to promote college going, and the availability and attractiveness of other postsecondary and employment options.

College Participation in California Higher Than National Average. The federal Department of Education estimates that 46 percent of 18– to 24–year olds in California were enrolled in postsecondary education in 2013. This participation rate is higher than all but ten states and three percentage points higher than the national average of 43 percent. Compared to other states, California has a higher percentage of its undergraduate enrollment in two–year institutions. In California, 60 percent of all undergraduates attend two–year institutions—a higher share than all but two other states (Illinois and Wyoming) and 14 percentage points higher than the national average of 46 percent.

For Community Colleges, Economy Affects Enrollment Demand. Though changes in the state’s college–age population affect community college enrollment demand, CCC enrollment demand is also affected by various other factors. For example, CCC enrollment demand tends to be tightly linked with economic conditions. In particular, demand for CCC’s workforce and career technical education courses tends to rise during economic downturns (when more people tend to be out of work) and fall during economic recoveries (when job opportunities are better).

Enrollment Demand Varies by Campus. Student demand can vary greatly by campus. For instance, at UC, the Berkeley and Los Angeles campuses receive the most applicants and are the most selective. In fall 2015, the two campuses admitted 19 percent and 16 percent of California resident freshman applicants, respectively. By contrast, the least selective UC campus (Merced) admitted 62 percent. Differences in enrollment demand also exist at CSU and CCC.

Enrollment Funding

State Traditionally Sets Enrollment Target for Each Segment. Under the traditional approach to funding enrollment, the state first considers the various factors discussed above and sets an enrollment target for each segment. Over the past few decades, the state typically has set one overall enrollment target for each segment rather than separate targets for undergraduate and graduate students. If the state increases a segment’s overall enrollment target, then the state decides how much associated funding to provide for enrollment growth. (As an exception to these practices, the state traditionally has not provided enrollment funding to Hastings. Instead, the state provides unallocated base increases and gives discretion to the school in setting its enrollment level.)

UC and CSU Enrollment Growth Traditionally Funded Based on Marginal Cost Formula. In the case of the universities, the state for decades funded enrollment growth based on the estimated cost of admitting one additional student. The state used a formula to calculate this “marginal cost.” The most recently used formula assumed the universities would hire a new professor for roughly every 19 additional students and linked the cost of the new professor to the average salary of newly hired faculty. In addition, the formula included the average cost per student for faculty benefits, academic and instructional support, student services, instructional equipment, and operations and maintenance of physical infrastructure. The marginal cost formula was based on the cost of all enrollment (undergraduate and graduate students and all academic disciplines excluding health sciences). The state provided each system flexibility to determine how to distribute enrollment funding to its campuses. If the systems did not meet the enrollment target specified in the budget within a certain margin, then the associated enrollment growth funding reverted back to the state.

In Recent Years, State Has Not Consistently and Clearly Linked Funding to Enrollment Growth for UC and CSU. As shown in Figure 2, the state did not set enrollment targets for UC and CSU in four of the nine years between 2007–08 and 2014–15. The state first omitted enrollment targets in the 2008–09 budget, when it entered the most recent recession and reduced base funding for UC and CSU. The purpose was to provide UC and CSU flexibility to manage state funding reductions. The state resumed enrollment funding from 2010–11 through 2012–13, but, in two of the three years, it did not require the universities to return money to the state if they fell short of the target. In effect, the targets these two years largely were symbolic. In 2013–14 and 2014–15, the state again chose not to include enrollment targets in the budget, primarily due to concerns the Governor had raised regarding enrollment–based funding. (The Governor argued it distracts from a focus on institutional and student outcomes.)

Figure 2

State Has Not Been Setting University Enrollment Targets on a Consistent Basis

Resident Full–Time Equivalent Students

|

2007–08 |

2008–09 |

2009–10 |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

|

|

UC |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Enrollment target |

198,455 |

None |

None |

209,977 |

209,977a |

209,977a |

None |

None |

Noneb |

|

Actual enrollment |

203,906 |

210,558 |

213,589 |

214,692 |

213,763 |

211,212 |

209,867 |

212,002 |

210,669 |

|

Percent changec |

3.3% |

1.4% |

0.5% |

–0.4% |

–1.2% |

–0.6% |

1.0% |

–0.6% |

|

|

CSU |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Enrollment target |

342,553 |

None |

None |

339,873 |

331,716a |

331,716a |

None |

None |

Noned |

|

Actual enrollment |

353,915 |

357,223 |

340,289 |

328,155 |

341,280 |

343,227 |

351,955 |

359,679 |

371,217 |

|

Percent changec |

0.9% |

–4.7% |

–3.6% |

4.0% |

0.6% |

2.5% |

2.2% |

3.2% |

|

|

aState budget did not require the universities to return money if they fell short of this target. bThe 2015–16 budget directs UC to add 5,000 undergraduate students by the 2016–17 academic year, as compared to the number enrolled in 2014–15. The budget provides $25 million to UC if it meets this expectation. cReflects percent change in actual enrollment. dThe 2015–16 budget directs CSU to add 10,000 full–time equivalent students by the end of fall 2016, as compared to the number enrolled in 2014–15. The budget does not identify a specific dollar amount for enrollment growth, but it fully funds CSU’s budget request, which assumed this level of growth. |

|||||||||

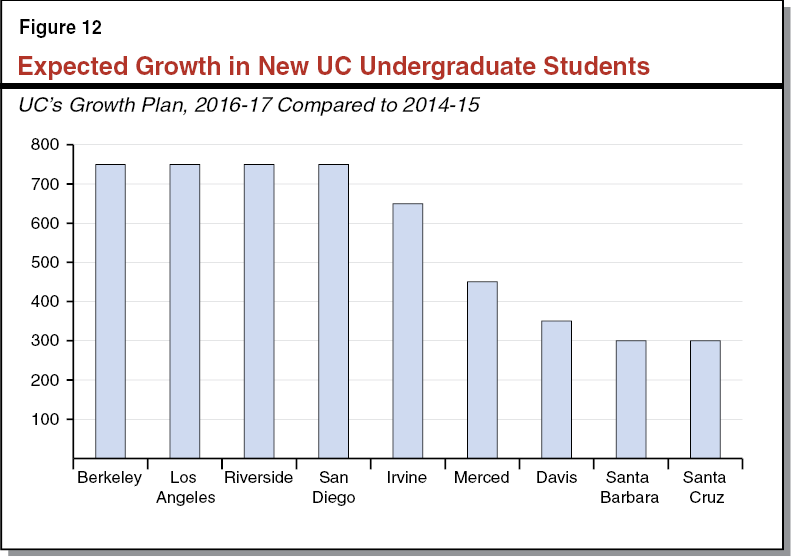

New Approach Taken Last Year. In 2015–16, the state resumed connecting funding to enrollment but took a different approach than it had in the past. Specifically, the state set enrollment targets in the 2015–16 budget but allowed each system until 2016–17 to meet the target. The state took this approach in recognition of the fact that by the time the state budget was being finalized in June 2015, UC and CSU had already largely determined their enrollments for fall 2015. The state also deviated from its traditional approach by specifying that the target for UC was for undergraduate students only.

State Continues to Link Funding to Enrollment Growth for CCC. The budget annually sets an enrollment target for CCC. State law requires that the system’s annual budget request for enrollment growth be based, at minimum, on changes in the adult population and excess unemployment (defined as an unemployment rate higher than 5 percent). The CCC also may request enrollment growth to cover “unfunded” (or over–cap) enrollment. The Governor and Legislature do not have to approve enrollment growth at the requested level. Their decisions tend to reflect the state’s budget condition—increasing the enrollment target when revenue increases (and the Proposition 98 guarantee rises) and reducing it when revenue falls. This approach often works counter to economic conditions and student demand. That is, unemployment tends to rise during recessions, stimulating enrollment demand, yet recessions likely mean a tighter state budget and fewer, if any, funds available for enrollment growth.

Enrollment Trends

UC Enrollment Relatively Flat in Recent Years. As shown in Figure 2, enrollment at UC over the past few years has increased or decreased by less than one percentage point each year. Looking over a somewhat longer period, enrollment in 2015–16 is expected to be 3.3 percent higher than it was in 2007–08 (prior to the start of the last recession), but 1.9 percent lower than in 2010–11 (when enrollment at UC peaked). We estimate the 18– to 24–year old population has grown by roughly 3 percent from 2007–08—around the same rate of change as UC enrollment.

CSU Enrollment Increasing Moderately in Recent Years. Enrollment at CSU has increased by 2 to 3 percentage points over the last few years. Enrollment in 2015–16 is expected to be at an all–time high (4.9 percent above the 2007–08 level). During the recession, enrollment decreased more notably at CSU than at UC, as CSU chose to reduce enrollment in order to manage state funding reductions. Since 2007–08, enrollment at CSU has grown faster than the 18– to 24–year–old population.

CCC Enrollment Has Fluctuated Notably This Economic Cycle. Beginning in 2007–08, CCC enrollment surged. While the state provided enrollment growth funds in both 2007–08 and 2008–09, student demand outpaced growth in funding, resulting in actual enrollment exceeding funded enrollment. In 2009–10, a particularly difficult budget year, the state reduced enrollment funding but actual CCC enrollment remained about the same. At the trough of the recession, actual CCC enrollment exceeded funded enrollment by about 95,000 full–time equivalent (FTE) students. As the state continued to reduce CCC funding, community college districts eventually responded by reducing their course offerings. Actual enrollment began to drop, presumably less from a drop in student demand and more from a lack of funding. By the end of 2012–13, actual enrollment was 12 percent (123,000 FTE students) below its 2008–09 peak. Since 2012–13, the state’s fiscal situation has improved, with the state funding enrollment growth in each of the past three years. With greater funding have come greater course offerings. Student demand, however, appears to be weakening, with many community college districts indicating difficulty in meeting their current funded enrollment targets.

Hastings Has Sharply Curtailed Enrollment. Juris Doctor (JD) enrollment at Hastings reached a high point in 2009–10 at 1,179 FTE students. Enrollment has declined to an estimated 778 FTE students in 2015–16—a drop of 34 percent from the peak. Hastings indicates the decline was a strategic move intended to (1) address slackening workforce demand for attorneys and (2) increase the academic qualifications of its student body.

Enrollment in California Has Grown More Slowly Than in Other States. Enrollment at California public institutions has grown more slowly since the start of the most recent recession compared to other states. Specifically, public higher education FTE enrollment in California grew 2.2 percent from 2007–08 through 2013–14, while the average growth across other states was 11 percent. Growth was slower in California for both four–year institutions and community colleges. Various factors might explain why public higher education enrollment in California has grown more slowly than in most other states, including differences in demographic growth and changes in state funding levels. Some enrollment in California also appears to have shifted to private sector institutions, as private sector FTE enrollment grew by 34 percent between 2007–08 and 2013–14.

Funding Per Student Has Increased in Recent Years. Per–student funding has increased at each segment the past few years. From 2012–13 through 2015–16, per–student funding increased by 27 percent at CCC, 16 percent at UC, and 13 percent at CSU. Inflation generally was quite low during this period—running at 1 to 2 percent annually. As a result, even after adjusting for inflation, funding per FTE student increased 22 percent at CCC, 11 percent at UC, and 9 percent at CSU. (Comparing these per–student funding figures back to 2007–08 is not possible due to certain changes in the way the state accounts for university expenditures.)

Nonresident Enrollment

Nonresident Enrollment Traditionally Not Factored Into State Budget Decisions. The state’s funding approach to enrollment traditionally has considered only resident students. This is because the state does not provide funding for nonresident students. As a result, each segment has had discretion to set nonresident enrollment levels.

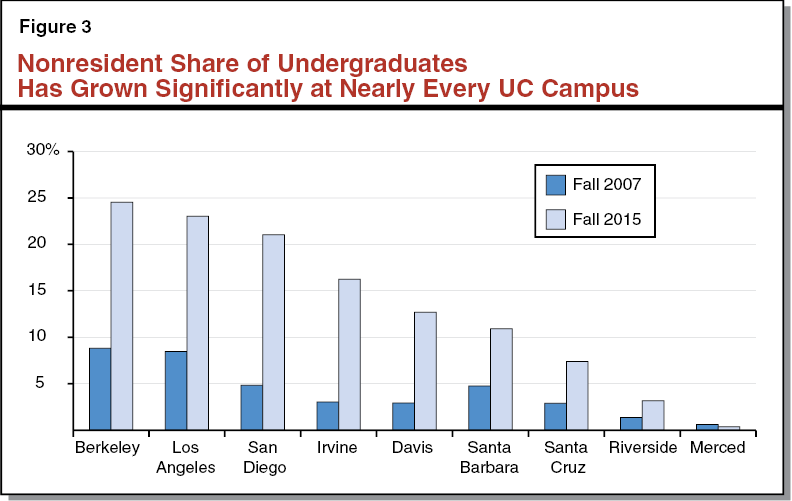

UC Has Largest Percentage of Nonresident Students. Currently, nonresidents make up 17 percent of all students at UC, 11 percent at Hastings, 6 percent at CSU, and 4 percent at CCC. UC also has experienced the largest growth in nonresident students in the recent past, particularly among undergraduates. (Most nonresident graduate students are able to establish residency after one year, thereby limiting their numbers.) UC undergraduate nonresident enrollment increased from about 7,100 students in 2007–08 to an estimated 29,000 students in 2015–16. Nonresidents’ share of the UC undergraduate student body quadrupled during this time.

Nonresidents Growing as a Share of UC Undergraduate Students at Nearly Every Campus. As shown in Figure 3, the share of nonresident undergraduates has grown from 2007 to 2015 at every UC campus, except for Merced. Though nonresidents have grown notably as a share of undergraduate students at nearly every campus, large differences still exist across campuses. For example, as shown in the figure, close to 25 percent of undergraduates at Berkeley currently are nonresidents, compared to 3 percent at Riverside. A number of factors could account for differences in the resident to nonresident ratio across campuses. Berkeley, which is a more selective campus, likely has greater ability to attract more applicants from outside of the state. Berkeley also might have higher costs relative to Riverside and it might have decided to partly pay for these by generating more nonresident tuition. (UC allows campuses to retain the tuition revenue they generate from nonresident students.) Cost differences across campuses could be attributable to a different mix of programs (with the sciences being more expensive to operate) as well as higher faculty compensation.

Nonresident Enrollment at UC Lower Than Other Similar Public Universities. Compared to other public universities with a similar level of research, UC has a lower share of incoming undergraduate students who are nonresidents. Specifically, across 64 comparison institutions, nonresidents make up 30 percent of new freshmen. The average across the UC system is 18 percent. (This percentage is different than the 17 percent noted above because it includes only new freshmen.) Specific UC campuses, however, are near or slightly above the national average. For instance, 31 percent and 27 percent of incoming freshmen at Berkeley and Los Angeles, respectively, are nonresidents.

UC Nonresident Students Generate More Revenue Than Resident Students. In addition to paying the resident tuition charge, UC nonresident students pay a supplemental tuition charge of about $27,000. The UC system requests $10,000 from the state to serve a resident student. UC asserts that the $17,000 excess funding generated by nonresidents is used to cross–subsidize services for California resident students. Since 2007–08, the UC system has allowed individual campuses to retain the revenue associated with nonresident supplemental tuition. (Prior policy had been to collect the revenue centrally and distribute it back out to all campuses based on systemwide priorities.)

Tuition and Financial Aid

Below, we examine affordability from a variety of angles, beginning with a focus on student tuition, then turning to financial aid.

Tuition

State Currently Does Not Have a Tuition Policy. A tuition policy establishes how tuition levels are to be adjusted over time. Depending on the policy, the tuition charge either explicitly or implicitly represents the share of education cost to be borne by students, with the remainder of cost primarily subsidized by the state through base funding appropriated to each of the higher education segments. (The full tuition charge only affects certain students, as financial aid policies can cover some or all of the tuition charge for financially needy students.) Though California had a tuition policy for several years during the late 1980s and early 1990s, it has not had a tuition policy the last couple of decades.

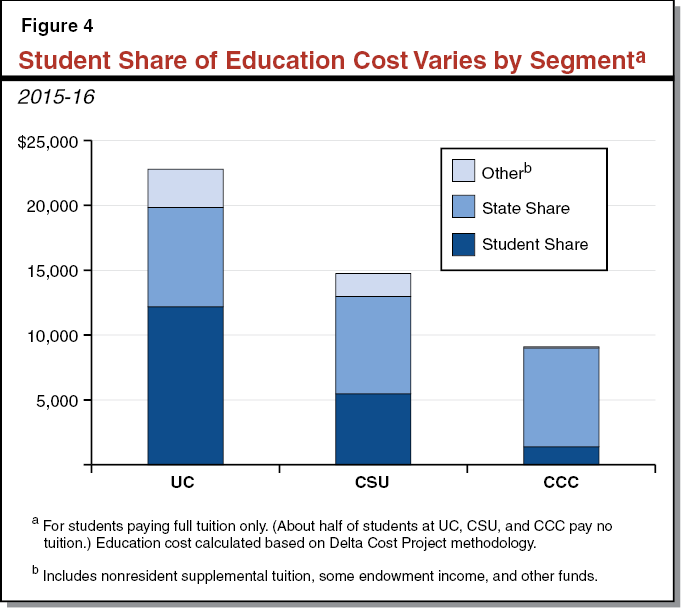

Each Segment Charges Different Tuition and Fees. UC’s systemwide charge for full–time undergraduate students is the highest—$12,240. CSU charges such students $5,472, while CCC charges $1,380 for a full course load (or $46 per unit). Campuses in each system also can charge additional fees for specific services or activities—such as student health services.

Student Share of Education Cost Varies by Segment. Figure 4 shows the proportion of education cost for a student paying full tuition that is covered by the state, the student, and other sources. (As discussed further below, about half of students at each segment pay no tuition.) UC students paying full tuition cover slightly more than half of their education cost, CSU students cover about one–third of their education cost, and CCC students cover 15 percent. (The federal government also covers a share of cost for students paying tuition, as some students [or their families] are eligible for a federal tax credit of up to $2,500 annually to reimburse for tuition costs.)

Segments’ Tuition and Fee Levels Vary Compared to Public Colleges in Other States. Compared to other public universities with a similar level of research activity, UC tends to have higher tuition and fees. Specifically, UC’s tuition and fees are higher than all but 10 of the 65 largest public research universities in other states. By contrast, tuition and fees at CSU are lower than all but 42 universities among a group of 244 masters–level public universities in other states. CCC tuition and fees are the lowest in the country, about 40 percent of the national average.

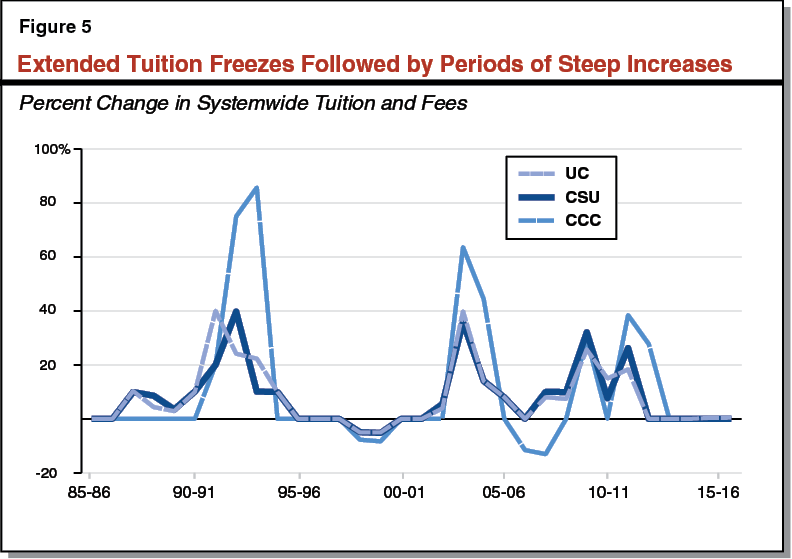

Tuition and Fees Tend to Be Volatile. As shown in Figure 5, tuition and fee levels in California tend to follow a pattern of flat periods punctuated by sharp increases. The flat periods generally correspond to years in which the state experienced economic growth, while the periods of steep increases generally correspond to periods when the state experienced a recession. During recessions, the state has often balanced its budget in part by reducing state funding for the segments. UC and CSU, in turn, increased tuition charges to make up for the loss of state support, and the state increased fees at CCC. This pattern could be affected by the new state reserve requirements enacted under Proposition 2 (2014), which could mitigate state revenue losses during recessions.

Financial Aid

Cost of Attendance Includes Tuition and Other Expenses. These other expenses include housing and food, personal expenses, books and supplies, and transportation. The cost of attendance varies across campuses within each system because some expenses (such as housing) vary by location. The cost also varies depending on whether a student lives on campus, off campus not with family, or off campus with family. Figure 6 shows the range of attendance costs across campuses at each system, by living arrangement. For each system, students living at home with family have the lowest cost of attendance. The cost of attendance for students living on campus and off campus not with family tend to be similar. The cost of attendance tends to be highest at UC, next highest at CSU, and lowest at CCC, though this is not always the case. For instance, Coastline Community College (located in Orange County) reports a cost of attendance for students living off campus not with family that exceeds the cost for students in the same living arrangement at all CSU campuses and one UC campus.

Figure 6

Cost of Attendance Varies by Segment and Living Arrangementa

2014–15

|

On Campus |

Off Campus (Not With Family) |

Off Campus (With Family) |

|

|

UC |

$31,300 to $34,800 |

$26,700 to $30,000 |

$24,500 to $26,100 |

|

CSU |

$19,600 to $26,200 |

$21,700 to $25,000 |

$10,100 to $13,200 |

|

CCC |

$11,000 to $15,400b |

$14,400 to $28,200 |

$5,400 to $12,300 |

|

aReflects the range across campuses, rounded to the nearest hundred. bOnly 9 of 112 colleges report a cost of attendance for students living on campus. |

|||

Cost of Attendance in California Typically Higher Than in Other States. Even the least expensive UC campus has a higher cost of attendance than nearly all other public universities with high research activity. CSU campuses also tend to have a higher cost of attendance relative to most other masters–level public universities in the country. A similar pattern holds for CCC compared to community colleges in other states.

Various Types of Financial Aid Help Students Cover Their Cost of Attendance. Types of aid include grants, scholarships, and tuition waivers (collectively called gift aid, because students do not have to pay back these amounts); student loans; federal tax benefits; and subsidized work–study programs. Financial aid may be need based (for students who otherwise might be unable to afford college) or nonneed based (typically scholarships or other payments based on academic merit, athletic talent, or military service). About two–thirds of resident undergraduate students at UC and CSU receive need–based financial aid in the form of gift aid, loans, or work study. At the community colleges, 46 percent of students receive such aid. (CCC students are much more likely to attend part–time and many aid programs require full–time attendance.)

Eligibility for Need–Based Aid Determined Using Federal Methodology. To be eligible for federal, state, and institutional need–based financial aid programs, students must complete a common, web–based application form (the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA). The federal Department of Education uses information from this form, including household income, certain available assets, and number of children in college, to determine a student’s expected family contribution (EFC) toward college costs. A student’s financial need is the total cost of attendance at a particular campus less his or her EFC. Campuses then combine (or “package”) various types of financial aid to meet as much of each student’s financial need as possible.

Three–Fifths of Financial Aid at UC, CSU, and CCC Comes in Form of Need–Based Gift Aid. Figure 7 displays how much financial aid students at California’s public institutions receive from various sources. As shown in the figure, California students received an estimated $10.2 billion from these sources in 2013–14, with over 60 percent of it in need–based gift aid. (This is in addition to $12 billion in nonneed–based subsidies the state provides for all students through direct appropriations to the segments.) For costs not covered by these sources, students typically rely on family income and assets, their own earnings and savings, and other types of borrowing.

Figure 7

Over Half of Aid Is Need–Based Gift Aid

2013–14 (In Billions)

|

Gift Aid (Need Based) |

|

|

Federal |

$2.8 |

|

Institutional |

2.0 |

|

State |

1.4 |

|

Subtotal |

($6.2) |

|

Loans |

|

|

Federal (subsidized) |

$1.1 |

|

Federal (unsubsidized) |

1.1 |

|

Other |

0.1 |

|

Subtotal |

($2.3) |

|

Tax Benefits |

|

|

Federal |

$1.4 |

|

Gift Aid (Nonneed Based) |

|

|

Institutional |

$0.2 |

|

Other |

0.1 |

|

Subtotal |

($0.2) |

|

Work Study |

|

|

Federal |

$0.1 |

|

Total |

$10.2 |

|

Federal |

$6.5 |

|

Institutional |

2.2 |

|

State |

1.4 |

|

Other |

0.2 |

|

Note: Figure reflects aid for UC, CSU, and CCC undergraduate students. Only programs providing more than $50 million in aid are shown. Some gift aid, institutional loans, and nonfederal work–study programs do not meet this threshold. |

|

Gift Aid Covers Full Tuition for About Half of Public College Students. About 55 percent of undergraduate students at UC and CSU receive aid sufficient to fully cover systemwide tuition and fees, and an additional 9 percent of UC students and 7 percent of CSU students receive partial tuition coverage. At CCC, 45 percent of students receive full fee waivers, paying for two–thirds of all course units taken.

State Provides Need–Based Gift Aid Through Cal Grants. The state’s Cal Grant program guarantees gift aid to California high school graduates and community college transfer students who meet financial need criteria and academic criteria. In addition, students who do not qualify for high school or community college entitlement awards but meet other eligibility criteria may apply for a limited number of competitive grants. Awards cover full systemwide tuition and fees at the public universities and up to a fixed dollar amount toward costs at private colleges. The program also offers stipends (known as access awards) for some students. Access awards are intended to help cover some living expenses, such as the cost of books, supplies, and transportation. A student generally may receive a Cal Grant for a maximum four years of full–time college enrollment or the equivalent.

Cal Grant Spending Has Grown Significantly, Driven by Increased Tuition and Participation. State spending on Cal Grants has increased from $813 million in 2007–08 to an estimated $2 billion in 2015–16. The increase primarily is due to sharp increases in the number of award recipients as well as increases in award amounts for students at the public universities. The number of award recipients increased from 207,300 in 2007–08 to 340,500 in 2015–16 (a 64 percent increase), while systemwide tuition and fees at the universities nearly doubled. Implementation of the California Dream Act, which beginning in 2013–14 made certain undocumented and nonresident students eligible for state financial aid, accounts for $67 million of the increase in Cal Grant spending.

State Recently Created New Program to Supplement Cal Grant Access Award. The 2015–16 budget provided $39 million for a new Full–Time Student Success Grant to supplement the access award for CCC students who are enrolled in 12 or more units. The CCC Chancellor’s Office expects the program to increase the access award by $600 in 2015–16—bringing the total access award for CCC students to $2,256.

State Also Recently Created Middle Class Scholarships for Certain UC and CSU Students. The Middle Class Scholarship program took effect starting in 2014–15. Under the program, students with household incomes up to $100,000 qualify for an award that covers 40 percent of their tuition (when combined with all other public financial aid). The percent of tuition covered declines for students with household income between $100,000 and $150,000, such that a student with a household income of $150,000 qualifies for an award covering up to 10 percent of tuition. The program is being phased in, with awards in 2015–16 set at 50 percent of full award levels, then 75 percent and 100 percent for the following two years, respectively. CSAC provides these scholarships to eligible students who fill out a federal financial aid application, though the program is not need–based according to the federal government’s financial aid formula. Unlike Cal Grants, the program is not considered an entitlement, with program funding levels capped in state law. If funding were insufficient to cover the maximum award amounts specified in law, awards would be pro–rated downward.

State Changed Certain Aspects of Middle Class Scholarship Program Starting in 2016–17. Whereas the program previously had no asset ceiling, 2015–16 trailer legislation establishes a ceiling of $150,000. (The asset ceiling excludes primary residences and funds in retirement accounts.) The legislation requires CSAC to adjust income and asset ceilings annually for inflation. The legislation also specifies that a student may receive a scholarship for no more than the equivalent of four years (or, in some cases, five years) of full–time attendance. To reflect savings from these changes as well as lower–than–anticipated participation in the program, the legislation adjusted the original statutory appropriations for the program down from $152 million to $82 million in 2015–16, from $228 million to $116 million in 2016–17, and from $305 million to $159 million thereafter.

Segments Offer Institutional Need–Based Gift Aid. In addition to Cal Grants and Middle Class Scholarships, UC and CSU operate institutional need–based programs. UC and CSU pay for these programs largely by redirecting a portion of tuition revenue. When packaging financial aid, UC first applies any applicable federal and state aid on a student’s behalf and assumes each student must contribute $9,500 through work or borrowing. It then uses institutional aid to fill any remaining gap between available resources and the cost of attendance. UC’s average gift aid per recipient from all sources exceeds tuition by about $4,600—meaning the average aid award pays for some living costs. By comparison, CSU uses its State University Grant program to cover full tuition for certain students based on their EFC. It does not cover other costs of attendance. At CCC, the Board of Governors (BOG) Fee Waiver program fully covers enrollment fees (but not other costs of attendance) for financially needy students. Though commonly considered institutional aid, as it is unique to CCC, the state effectively funds the BOG fee waiver program through CCC apportionments. (If the state did not use these associated funds for apportionments, it likely would use them for other CCC purposes.)

Institutional Need–Based Gift Aid Has Grown Significantly. Between 2007–08 and 2015–16, institutional aid spending more than doubled at the universities, growing from $313 million to an estimated $735 million at UC and from $241 million to an estimated $581 million at CSU. At CCC, spending on BOG Fee Waivers has nearly quadrupled from $221 million in 2007–08 to an estimated $777 million in 2015–16. The increases at each segment primarily occurred as a result of increases in tuition and fees over this time.

Net Price Ranges Considerably by Segment and Campus. The “average net price” for an institution is the cost of attendance (tuition and living expenses) minus the average grant aid received by grant recipients. The federal government reports an average net price for first–time, full–time undergraduate students by institution that is weighted according to how many students live on campus, off campus not with family, and off campus with family. At UC, the average net price ranges from $12,000 (at the Merced campus) to $16,700 (at the Berkeley campus). The range across CSU campuses is much broader, spanning from $1,600 (at the Dominguez Hills campus) to $16,800 (at the San Luis Obispo campus). A similar range exists at CCC campuses, with average net prices spanning from $1,400 (at College of the Sequoias) to $12,200 (at Irvine Valley College). Because aid policies largely are standardized across campuses, the variation in net price across campuses mostly relates to differences in cost of attendance (due to regional differences in housing and other costs) as well as differences in students’ financial need across campuses.

Net Price Also Varies Considerably by Income Level. For instance, at UC campuses, the average net price for students whose families earn less than $30,000 annually ranges from $8,000 to $10,900, while the average for students whose families earn more than $110,000 annually ranges from $26,900 to $30,900. Variations by income group also exist at CSU campuses and CCC campuses. This is because financial aid programs typically target lower–income students who might otherwise be unable to afford college.

Student Borrowing Much More Common at Universities Than CCC. Each year, 43 percent of UC and CSU undergraduates take out loans, with an average loan amount of $6,500 at UC and $7,600 at CSU. By the time they graduate, 55 percent of UC students and 48 percent of CSU students have taken out student loans. Among those borrowing, the average student loan debt at graduation is $19,100 for UC students and $15,700 for CSU students. (In addition, about 6 percent of UC and CSU parents who apply for financial aid take out loans, with average annual loan amounts of about $15,100 and $12,000, respectively.) By contrast, only 2 percent of CCC students borrow each year.

Average Student Debt Comparatively Low in California. About 60 percent of students at four–year public universities nationally graduate with loan debt, with an average debt load of $25,900. This is 36 percent higher than the average debt at UC and 65 percent higher than CSU. Nationally, 17 percent of students attending public two–year institutions report borrowing—ten times the proportion at CCC.

Small Share of UC and CSU Students Default on Loans. About 95 percent of all borrowing at UC and CSU is through federal loans. Three–year default rates on these loans vary by UC and CSU campus but tend to be relatively low. For instance, over two–thirds of UC and CSU campuses have default rates that are less than 5 percent, and no campus has a default rate greater than 10 percent. In comparison, the national default rate for four–year public universities is 8 percent.

Federal Loans Have Income–Driven Repayment Plans. The most common type of federal loan—William D. Ford federal direct loans—currently offers new borrowers six repayment plans. Three of these plans, known as income–driven repayment plans, vary loan repayments based on the income of the borrower as a way to improve affordability and reduce the likelihood of a student defaulting. For example, the Pay As You Earn Repayment Plan (PAYE) caps monthly repayments at 10 percent of a borrower’s discretionary income (defined as income earned above 150 percent of the poverty level, adjusted for location and household size). Each of these three plans also forgives any remaining loan balances after a set period. For example, PAYE forgives balances after 20 years, or 10 years for eligible borrowers in public service careers.

Performance

Below, we describe the state’s performance measures for higher education and review data on the segments’ recent performance in certain areas.

Performance Measures

State Recently Adopted Broad Goals for Higher Education. Chapter 367 of 2013 (SB 195, Liu) establishes three goals for higher education. The goals are: (1) improve student access and success, such as by increasing college participation and graduation rates; (2) better align degrees and credentials with the state’s economic, workforce, and civic needs; and (3) ensure the effective and efficient use of resources to improve outcomes and maintain affordability. The law states the Legislature’s intent that these goals guide state budget and policy decisions for higher education. The law also calls for the creation of performance measures to monitor progress toward these goals. To date, the state has not adopted these measures.

State Recently Adopted Specific Performance Measures for UC and CSU. Separate from Chapter 367, the 2013–14 budget package codified a new requirement for UC and CSU to report annually on a number of performance measures. The university systems are required to report by March 15 of each year their graduation rates, spending per degree, and the number of transfer and low–income students they enroll, among other measures. In addition, recent state budgets have required the UC and CSU governing boards to adopt academic plans each year that set their own targets for each statutory performance measure for each of the following three years. Figure 8 shows UC’s and CSU’s current performance and their respective performance targets.

Figure 8

Comparing UC’s and CSU’s Current Performance and Performance Targetsa

|

State Performance Measure |

University of California |

California State University |

|||

|

Current Performanceb |

Targetc |

|

Current Performanceb |

Targetc |

|

|

CCC Transfers Enrolled. Number and as a percent of undergraduate population. |

34,344 (18%) |

34,425 (18%) |

143,322 (36%) |

145,480 (35%) |

|

|

Low–Income Students Enrolled. Number and as a percent of total student population. |

76,452 (41%) |

76,708 (40%) |

207,528 (50%) |

213,614 (50%)d |

|

|

Graduation Rates.e |

|||||

|

63% |

66% |

19% |

20% |

|

|

57% |

60% |

12% |

14% |

|

|

57% |

59% |

|||

|

52% |

56% |

|||

|

57% |

60% |

30% |

32% |

|

|

53% |

56% |

29% |

31% |

|

|

62% |

66% |

|||

|

62% |

65% |

|||

|

Degree Completions. Annual degrees awarded for: |

|||||

|

33,123 |

36,270 |

36,704 |

45,238 |

|

|

14,745 |

15,080 |

42,771 |

45,443 |

|

|

13,917 |

15,110 |

18,831 |

19,513 |

|

|

23,999 |

25,660 |

45,660 |

50,030 |

|

|

62,988f |

Not reported |

105,693 |

117,146 |

|

|

First–Year Students on Track to Graduate on Time. Percentage of first–year undergraduates earning enough credits to graduate within four years. |

51% |

51% |

51%g |

55%g |

|

|

Funding Per Degree. State General Fund and tuition revenue divided by number of degrees for: |

|||||

|

$105,100f |

$121,400 |

$38,548f |

$42,322 |

|

|

Not reported |

$28,900 |

Not reported |

$51,830 |

|

|

Units Per Degree. Average course units earned at graduation for: |

Quarter Units |

Semester Units |

|||

|

187 |

183 |

138 |

138 |

|

|

97 |

93 |

141 |

140 |

|

|

Degree Completions in STEM Fields. Number of STEM degrees awarded annually to: |

|||||

|

16,371f |

Not reported |

18,519 |

24,531 |

|

|

8,167 |

8,830 |

4,278 |

4,766 |

|

|

8,775 |

9,382 |

8,802 |

10,628 |

|

|

aTargets based on administration’s General Fund and tuition revenue assumptions for 2016–17 through 2018–19. bFall 2015 for enrollment and annual 2014–15 for completions and units, unless otherwise specified. cFall 2018 for enrollment and annual 2018–19 for completions and units, unless otherwise specified. dFall 2017. eFor most recent and future cohorts as reported by segments. f2013–14. gCSU excludes students not enrolled at the beginning of the second year. STEM = science, technology, engineering, and math. |

|||||

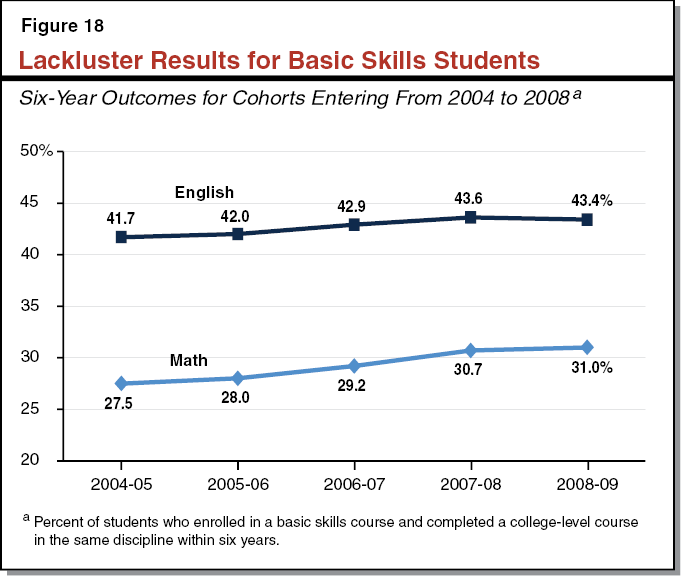

State Also Required CCC to Set Performance Targets. The 2014–15 budget package required each community college and the CCC Board of Governors to adopt measures and targets for student performance by June 30, 2015. The Board of Governors adopted systemwide measures and targets in July 2014. (The measures come from CCC’s Student Success Scorecard, which was developed in 2012.) These measures are tracked for a cohort of students over a six–year period. Figure 9 shows CCC’s current performance and targets.

Figure 9

CCC Systemwide Performance Measures and Targets

|

Measure |

Current Performancea |

Target |

|

Completion Rate. Completion defined as: (1) earning an associate degree or credit certificate, (2) transferring to a four–year institution, or (3) completing 60 UC/CSU transferable units with a GPA of at least 2.0 within 6 years of entry. |

39% for underprepared 70% for prepared 47% overall |

Increase rate by 2.5 percent (of rate) annually. |

|

Remedial Progress Rate. Success in college–level English or math class for students who took remedial English, remedial math, or English as a second language. |

43% in English 31% in math 28% in English as a second language |

Increase rate by 2.5 percent (of rate) annually. |

|

CTE Completion Rate. CTE students who completed a degree, certificate, 60 transferable units, or transferred. |

50% |

Increase rate by 2.5 percent (of rate) annually. |

|

Associate Degrees for Transfer. Number of these degrees completed annually. |

11,448 |

Increase number by 5 percent annually for next five years. |

|

Equity Rate. Index showing whether a subgroup’s completion rate is low compared with overall completion rate. An index of less than 1.0 indicates underperformance. |

0.73 American Indian 0.79 African American 0.82 Hispanic 0.88 Pacific Islander 1.09 White 1.38 Asian |

Increase annually until all indices are 0.80 or above. |

|

Education Plan Rate. Share of students who have an education plan. |

Not availableb |

To increase percentage each fall term. |

|

FTE Years Per Completion. A measure of efficiency showing amount of instruction, on average, required for each completion. (A student completing 60 units, the standard length of an associate degree or preparation for transfer, would generate two FTE years.) |

5.3 for underprepared 2.85 for prepared 4.39 overall |

Decrease measure (increase efficiency). |

|

Participation Rate. Number of students ages 18–24 attending a community college per 1,000 California residents in the same age group. |

265 |

Increase participation rate each year. |

|

Participation Among Subgroups. Index comparing a subgroup’s share of enrollment with its share of the state population. An index of less than 1.0 indicates underrepresentation.c |

0.87 White 1.01 Hispanic 1.01 African American 1.22 Asian |

Maintain index above 0.80 for all subgroups. |

|

a2013–14 for annual data and 2008–09 cohort for cohort data, unless otherwise specified. bNew data measure. Reporting was optional in 2013–14. cReflects participation rates in 2012–13. Rate for 2013–14 not yet available. CTE = career technical education and FTE = full–time equivalent. |

||

State Has Not Directly Linked Funding for UC, CSU, or CCC to Their Institutional Performance. The state to date has not adopted a performance funding formula that adjusts funding based upon the segments’ performance. The state, however, has provided some targeted funding in recent years related to institutional performance. Most notably, the state increased CCC’s Student Success and Support Program from $49 million in 2012–13 to $427 million in 2015–16. It also created a one–time $50 million program in 2014–15 to promote innovative models of higher education at CCC, CSU, and UC campuses. In some cases, the segments also have chosen to dedicate otherwise unallocated resources to improving performance. Most notably, CSU is dedicating $38 million of its unallocated base increase in 2015–16 to expanding its student success initiatives.

Governor Trying to Boost Institutional Performance Through an Agreement With UC. In May 2015, the Governor and the UC President announced they had reached an agreement that UC would undertake certain operational changes intended to improve its institutional performance. (The agreement also calls for multi–year funding increases for UC and allows UC to increase its tuition charge starting in 2017–18.) Among other changes, the agreement calls for UC to (1) more closely align its lower–division requirements for its 20 most popular majors with those used by CSU and CCC for associate degrees for transfer, (2) initiate a pilot program to use adaptive learning technologies to improve instruction and student persistence, and (3) identify three–year degree pathways in 10 of its top 15 majors.

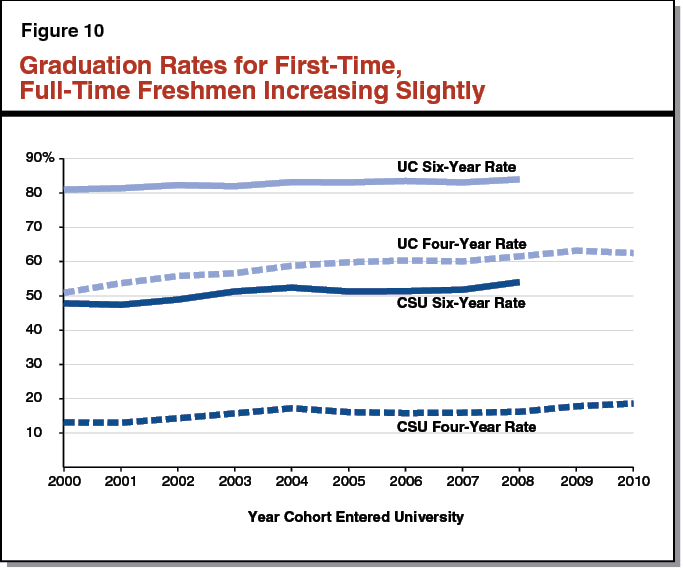

Performance Trends

Slight Increases in UC and CSU Graduation Rates for Freshmen. As shown in Figure 10, graduation rates for students entering UC and CSU as freshmen have increased slightly in recent years. At UC, more than 60 percent of incoming full–time freshmen graduate within four years and more than 80 percent graduate within six years. By comparison, most public institutions similar to UC in terms of research activity have lower graduation rates, with an average four–year graduation rate of 45 percent and six–year graduation rate of 70 percent. Graduation rates are much lower at CSU than UC. Less than 20 percent of incoming full–time freshmen graduate within four years and just over half graduate within six years. These rates are similar to the graduation rates at masters–level public institutions in other states, which have an average four–year graduation rate of 24 percent and average six–year rate of 45 percent.

Graduation Rates for UC and CSU Transfer Students Also Increasing Slightly. A two–year graduation rate for transfer students is analogous to a four–year graduation rate for entering freshmen. The two–year graduation rate for transfer students at UC has increased from 46 percent a decade ago to 55 percent today. The two–year rate at CSU has increased from 21 percent to 28 percent over the same time. UC’s two–year rate for transfer students is less than its four–year rate for freshmen, while at CSU the opposite is true. This means freshmen generally outperform transfer students (in terms of graduation rates) at UC, whereas transfer students generally outperform freshmen at CSU. Graduation rates for transfer students at both UC and CSU increase notably when measured over longer period of times. For instance, the four–year graduation rate for transfer students is 88 percent at UC and 73 percent at CSU.

Based on Certain Milestone Measures, CCC Performance Improving Slightly. Milestone performance measures show the share of students passing certain academic milestones commonly associated with completion. CCC milestone measures include the percentage of students persisting over three terms, completion rates of college–level English and math courses for students entering unprepared and English as a second language students, and the percent of students completing 30 units. Each of these measures has increased slightly in recent years. For instance, the three–term persistence rate has risen from 71 percent in 2009–10 to 72 percent in 2013–14.

CCC Program Completion Rates Declining Slightly. Instead of measuring the share of entering students that completes a degree within a specified period, CCC measures the success of a “completion cohort.” A student in a completion cohort is one who enters CCC as a first–time student, enrolls in six units within three years of first enrolling, and attempts any math or English course during that period (typically an indicator that the student has some academic goal). A successful completion outcome is earning an associate degree or a credit certificate, transferring to a four–year institution, or becoming “transfer prepared” by successfully completing 60 transferable units with at least a “C” average. Completion rates have been declining slightly in recent years. They peaked at 49 percent in 2011–12 and since have dipped to 47 percent for 2013–14. More recent data likely will begin showing a reversal of this trend, as completion rates appear somewhat linked with state funding, and state funding has increased notably in recent years.

Back to the TopUniversity of California

In this section, we begin with an overview of the Governor’s proposed budget for UC. We then analyze specific UC revenue and expenditure proposals and make associated recommendations. (In a separate report released on February 10—Review of UC’s Merced Campus Expansion—we discuss UC’s one large capital outlay proposal for 2016–17.)

Overview

Governor’s Budget for UC Consists of $29 Billion From All Sources in 2016–17. This is a $903 million (3 percent) increase from the current year. Of total UC funding, about one–quarter comes from state General Fund and student tuition revenue. These two fund sources primarily support UC’s mission of providing undergraduate and graduate education. As a major research university, UC is involved in various other activities. For example, more than one–quarter of UC’s revenue comes from its five medical centers, which provide health care services to patients. UC also annually receives a substantial amount of federal funding to support specific research activities.

Governor Proposes to Continue His Long–Term Funding Plan for UC. In 2013–14, the Governor announced a four–year funding plan for UC. Under the plan, the state provided UC 5 percent General Fund base increases in the first two years (2013–14 and 2014–15) and a 4 percent increase in the current year (2015–16). The plan includes another 4 percent increase for UC in 2016–17. In order to receive these base augmentations, the Governor has required UC not to increase tuition for resident students. The Governor has not tied these base increases to specific budgetary priorities (such as enrollment growth). Instead, UC has set its own priorities with its state funding. (In May 2015, the Governor announced his intention to propose 4 percent General Fund increases for UC in 2017–18 and 2018–19. The Governor also proposed for UC to begin increasing tuition at around the rate of inflation beginning in 2017–18.)

Governor Proposes General Fund Increase of $209 Million (6.4 Percent). Figure 11 shows the Governor’s January revenue assumptions and UC’s corresponding expenditure plan. Consistent with his long–term plan, the Governor proposes a $125 million (4 percent) ongoing, unrestricted General Fund base increase. The Governor’s budget also includes two one–time General Fund augmentations for specific purposes: (1) $171 million to pay down a portion of UC’s unfunded pension liability (scored as a Proposition 2 debt payment) and (2) $35 million for deferred maintenance. These augmentations are offset by $122 million in expiring one–time funds.

Figure 11

University of California Budget

(In Millions)

|

Revenuea |

|

|

2015–16 Revised |

|

|

General Fund |

$3,257 |

|

Tuition and fees |

3,028 |

|

Total |

$6,285 |

|

2016–17 Changes |

|

|

General Fund |

$209 |

|

Tuition and feesb |

158 |

|

Subtotal |

($367) |

|

Otherc |

145 |

|

Total |

$512 |

|

2016–17 Proposed |

|

|

General Fund |

$3,467 |

|

Tuition and fees |

3,186 |

|

Total |

$6,652 |

|

Changes in Spending |

|

|

UC’s Plan for Unrestricted Funds |

|

|

General salary increases (3 percent) |

$152 |

|

Resident undergraduate enrollment growth (3.4 percent)d |

50 |

|

Academic quality initiativese |

50 |

|

Faculty merit salary increases |

32 |

|

Operating expenses and equipment cost increases |

30 |

|

Health benefit cost increases (5 percent) |

27 |

|

Deferred maintenance |

25 |

|

Pension benefit cost increases |

24 |

|

Debt service for capital improvements |

15 |

|

Nonresident enrollment growth (3.2 percent)f |

14 |

|

Dream Loan Program |

5 |

|

Retiree health benefit cost increases |

4 |

|

Subtotal |

($428) |

|

Restricted General Fund |

|

|

Proposition 2 payments for UC Retirement Plan (one time) |

$171 |

|

Deferred maintenance (one time) |

35 |

|

Remove one–time funding provided in 2015–16 |

–122 |

|

Subtotal |

($84) |

|

Total |

$512 |

|

aIncludes all state General Fund. Reflects tuition after discounts. (In 2016–17, UC is projected to provide $1.1 billion in discounts.) bReflects increases in nonresident supplemental tuition (8 percent), the Student Services Fee (5 percent), and increased enrollment, offset by increases in discounts. cReflects: (1) General Fund for enrollment growth UC intends to carry over into 2016–17, (2) savings from administrative efficiencies, (3) increased revenue from investments, and (4) philanthropy. dUC has not yet indicated its final plan for resident graduate enrollment growth. eFor purposes such as increasing instructional support, reducing student–to–faculty ratios, recruiting faculty, increasing faculty salaries, and providing stipends to graduate students. UC indicates it will allow campuses to determine how to spend the funds. fFunded from nonresident tuition. |

|

Governor Assumes Tuition Revenue Increases $158 Million (5.2 Percent). Specifically, the Governor assumes increases of: (1) $88 million in nonresident supplemental tuition revenue due to an 8 percent rate increase, coupled with an increase in nonresident students; (2) $76 million in other tuition revenue due to resident enrollment growth and the phasing out of tuition discounts for nonresident students; (3) $19 million in Student Services Fee revenue from a 5 percent rate increase and enrollment growth; and (4) $4 million in professional supplemental tuition revenue from enrollment growth. These tuition revenue increases are offset by a $30 million increase in tuition discounts.

UC Assumes $95 Million in Ongoing Savings and Revenue From Other Sources. UC indicates it has identified four ways to generate new savings and revenue for its education program. First, UC expects $40 million in new revenue from increased investment returns. (The increase is due to UC shifting a portion of its reserves from a lower–yield, short–term investment fund into a higher–yield, longer–term investment fund.) Second, UC assumes it will save $30 million through improved procurement practices across its campuses. Third, UC anticipates $15 million in savings from self–insuring for certain risks. Finally, UC assumes a $10 million increase in philanthropic donations available for instructional purposes.

UC Assumes $50 Million Additional General Fund for Meeting Enrollment Expectations. The 2015–16 budget set an expectation for UC to enroll 5,000 more resident undergraduate students in 2016–17 compared to 2014–15. The budget authorizes the Director of Finance to augment UC’s budget by $25 million (ongoing) in May 2016 if UC demonstrates it will meet this expectation. In his 2016–17 budget, the Governor assumes UC will meet this target and receive the associated funding. UC, however, asserts it will not be able to spend the $25 million during 2015–16 and indicates it intends to carry the funds over into 2016–17. UC intends to dedicate $50 million toward supporting the 5,000 students in 2016–17 (equating to $10,000 per student). (In Figure 11, we include this enrollment funding in the “other” revenue changes.)

Key Issues Before the Legislature. UC developed an expenditure plan that is based on the level of funding proposed in the Governor’s budget. We analyze key features of this expenditure plan. We start by considering the alternative revenue sources identified by UC to support its education program. Afterward, we analyze the following expenditure areas: inflationary cost increases, UC’s unfunded pension liability, enrollment growth, maintenance, and UC’s proposal to enhance academic quality. As we have discussed in past years, we have major concerns with the Governor’s approach to allow UC to set its own spending priorities without legislative input. We continue to recommend the Legislature designate funding in the budget for high state priorities.

Alternative Revenue

UC Recently Began Directing More Alternative Fund Sources to Education Costs. The state historically has considered state funding and student tuition revenue the primary sources of funding for UC education. In addition, the state and UC by longstanding practice have considered a small amount of certain other UC revenues, such as a portion of UC’s patent royalty income, as paying for education. In recent years, however, UC has been factoring funding from different revenue sources, such as philanthropy, into its annual state budget plan. Moreover, in a recent biennial report to the Legislature on the cost of education, UC estimated it spends $24,157 per student, with $7,871 (one–third) originating from sources other than state funding and student tuition. The report, however, did not itemize these other sources of funding. (The $24,257 estimate is an average of the cost of education for undergraduate and graduate students. It excludes the health sciences.)

Required Report Lacked Key Information on Other Funds Used for Education. To better understand what revenue sources UC uses to pay for students’ education, the state, as part of the 2015–16 budget package, required UC to submit a report by December 2015 describing all fund sources it can legally use to pay for students’ education. Though the report UC submitted identified all fund sources UC is legally allowed to spend on education, it did not itemize the amount it uses from each source. As a result, the state still lacks key information on the funds UC makes available for education.

Recommend Requiring UC to Identify Fund Sources in Cost of Education Reports. UC’s identified alternative revenues may have positive implications for state budgeting. The Legislature, however, lacks key information on these revenue sources. For example, are these sources mostly one time or ongoing in nature? Is education the appropriate use of these funds? Does UC plan to rely more or less heavily on them moving forward? To obtain better information on how UC pays for students’ education, we recommend the Legislature modify existing state law to require UC’s biennial cost of education report (next due in October 2016) to identify the amount of each alternative fund source used in its calculations. Understanding these fund sources could facilitate future conversations on how the state and the university share the cost of education.

Inflation

Inflation Affects Three Areas of UC’s Budget. These areas are (1) employee compensation costs; (2) other operating expenses, such as utility bills and equipment costs; and (3) capital outlay. (Because the state now combines UC’s support and capital budgets and adjusts annually by a certain percentage, it is effectively making an inflationary adjustment to capital spending.) We discuss these three areas in greater detail below.

Compensation Costs Are UC’s Largest Expense. Compensation consists of the salaries and benefits UC pays its employees. Employee compensation is the largest driver of UC’s instruction costs (over 80 percent of UC’s core academic budget). Instruction–related employees include faculty, administrators, counselors, librarians, and management staff.

Operating Expenses and Equipment Costs Are a Smaller Portion of UC’s Budget. UC also spends money on goods and services. For instance, UC procures instructional equipment and library materials and it pays for utilities. In 2015–16, UC’s operating expenses and equipment costs made up about 13 percent of its core academic budget.

Funding for Capital Outlay Recently Shifted Into UC’s Operating Budget. For most state agencies, the state issues bonds for capital outlay projects and funds the associated debt service separately from agencies’ operating budgets. Recently, the state began treating capital outlay as an operating expense for UC and CSU. That is, the state shifted all funding for debt service associated with UC projects into UC’s operating budget. The state also provided UC the authority to (1) issue bonds by pledging its General Fund appropriation and (2) repay the associated debt service using its General Fund. Given these changes, the state has not issued bonds for UC projects the past few years and instead has expected UC to fund new capital projects from within its operating budget.