LAO Contact

January 31, 2017

Creating a Debt Free College Program

Executive Summary

Report Considers Design and Cost of a “Debt Free College” Program. The Supplemental Report of the 2016‑17 Budget Act directs our office to provide the Legislature with options for creating a new state financial aid program intended to eliminate the need for students to take on college debt. The reporting language envisions a program under which the state covers all remaining college costs (tuition and living expenses) after taking into account available federal grants, an expected parent contribution, and an expected student contribution from work earnings. Though not specified in the reporting language, our understanding of the intent is for the program to focus on resident undergraduate students attending public colleges in California.

Program Likely to Limit but Not Eliminate Student Loan Debt. The debt free college program described in the reporting language is based upon what some financial aid experts refer to as shared responsibility. Shared responsibility programs can be designed to provide students a pathway to debt free college. Importantly, however, these programs do not necessarily eliminate loan debt for all students. Unless programs require students to make their contribution through work, some students might prefer to borrow. Also, some students might borrow if they experience difficulty finding employment or if their parents fail to provide their full contribution.

Various Assumptions Underlie Cost Estimate for New Program. One of our key assumptions is that the cost of the new program generally is based on current college costs as estimated by the California Community Colleges (CCC), the California State University (CSU), and the University of California (UC). Another key assumption is that the expected parent contribution is based on a federal calculation used for most existing financial aid programs. We assume students work 15 hours per week during the academic year and 40 hours per week during the summer, resulting in a $7,300 student work expectation (after deducting an allowance for summer living expenses). In estimating the initial cost of the new debt free college program, we do not assume any increase in total enrollment (due to more college gift aid being available), any shift in enrollment among the public systems (due to all segments becoming equally affordable), or changes in students’ living arrangements (due to all living arrangements, including living away from home, becoming equally affordable). The magnitude of these behavioral responses would depend on the specifics of the program adopted, but could be significant. We also assume only students taking 6 or more units qualify for the program.

Program Estimated to Cost Additional $3.3 Billion Dollars Annually. Of this amount, $2.2 billion is for CCC students, $800 million is for CSU students, and $300 million is for UC students. (These amounts are on top of all existing gift aid.) Costs vary by segment primarily due to differences in the number of students they serve, as well as some variation in current levels of gift aid per student. Though our estimate of the initial cost of a new debt free college program is based upon the best available information to us at the time this report was prepared, actual program costs over the longer term could turn out to be notably higher or lower.

Modifying Requirements for Part‑Time Students Could Cut Costs in Half. The Legislature could consider setting a higher minimum unit requirement than we assume in our base estimate. For example, the Legislature could consider setting a 12 unit minimum—thereby limiting the program to full‑time students. The associated savings could be significant, particularly at CCC. Were part‑time students excluded from the program (and these students did not shift to full‑time study), we estimate CCC program costs would drop by $1.6 billion. Alternatively, the Legislature could consider setting a higher expected student contribution for part‑time students. For instance, students taking between 6 and 12 units might be expected to work 30 hours (rather than 15 hours) per week during the academic year given they are spending less time in class. Under this particular example, were students to remain enrolled only part time, their higher expected contribution from work earnings generally would result in them no longer qualifying for debt free college aid, with CCC program costs also dropping by $1.6 billion.

Adding a Time Limit and Academic Achievement Requirement Could Reduce Costs Too. Because the debt free college aid program would cover living costs, the Legislature likely would want to consider imposing a time limit on aid. Given such a program is designed to allow students to enroll full time, the Legislature might consider a two‑year limit at CCC and a four‑year limit at CSU and UC. Such time limits would reduce costs notably. This is because on‑time graduation rates at CCC, CSU, and UC currently are low and many students enroll for additional semesters. As a result, a sizeable share of the each system’s student body could time out of the program were it to have these limits. For instance, we estimate that about 20 percent of CSU students are beyond their fourth year. In addition, having a requirement for students to achieve certain academic standards—either for initial or continuing eligibility for the program—also would reduce program costs.

Administering Program by Consolidating Existing Aid Programs Offers Significant Benefits. California currently has many aid programs with a slew of rules and requirements, making it confusing for students and families to understand what aid is available to them. Consolidating all aid into one grant program could help to make financial aid more understandable for students, families, and policy makers. As with any major program restructuring, however, consolidation would involve some administrative challenges for the state and the segments. Though a new streamlined aid program has significant benefits, the Legislature could decide instead to add the debt free college program on top of all existing aid programs. Were the Legislature to take this latter approach, creating a simplified message for students and families to understand the plethora of state programs would be critical.

Several Options for Phasing In New Program. Given the significant costs associated with the program, the Legislature could consider phasing it in over time. One phase‑in approach is to tailor the program initially to pay only for tuition costs, consistent with the state’s historical practice of targeting aid primarily toward tuition. Under this approach, program costs would drop significantly because most financially needy students at CCC, CSU, and UC already pay no tuition. Another phase‑in approach is to prioritize funding for students based on their financial circumstances. For instance, students who have the lowest expected family contribution could receive the most aid. A third option is to set a fixed budget in the initial years and ration award coverage for each student. This could be done either by assuming each student has a higher expected work contribution or by proportionately reducing each student’s award according to a sliding scale.

Introduction

Report Considers Design and Cost of a “Debt Free College” Program. The Supplemental Report of the 2016‑17 Budget Act directs our office to provide the Legislature with options for creating a new state financial aid program intended to eliminate the need for students to take on college debt. The reporting language envisions a program under which the state covers all remaining college costs after taking into account available federal grants, an expected parent contribution, and an expected student contribution from work earnings. The reporting language requires us to provide a cost estimate for the program as well as present options for administering and phasing in the program, including one specific option of consolidating all existing state and institutional aid programs into a single program. Though not specified in the reporting language, our understanding of the legislative intent is for the program to focus on resident undergraduate students attending public colleges in California. Also in accordance with the reporting language, we focus our analysis on increasing state financial aid spending as a means of reducing student borrowing, rather than considering alternative approaches, such as reducing college costs.

Report Contains Two Main Sections. First, we provide background information on higher education costs and financial aid in California. Second, we examine various features of a potential new debt free college program.

Back to the TopBackground

Below, we begin with an overview of California’s higher education system. Next, we discuss college costs in California, describe financial aid programs available to California students, and provide information on student borrowing.

California’s Higher Education System

California Has Three Public Higher Education Systems. Each of the three public systems serves different undergraduate student populations. The California Community Colleges (CCC) serve the broadest population. Open to all adult Californians, CCC provides instruction in basic skills, career technical education leading to certificates and credentials, and lower division coursework leading to associate degrees and transfer to baccalaureate institutions. Whereas CCC is open to all adults, the California State University (CSU) and the University of California (UC) are selective. For freshman admission, CSU and UC draw from the top one‑third and top one‑eighth of California public high school graduates, respectively. For transfer admission, the systems admit community college students with a lower‑division grade point average of at least 2.0 for CSU and 2.4 for UC.

California Also Has a Private Higher Education Sector. California’s private sector consists of about 1,250 institutions. These institutions vary considerably in terms of selectivity and the types of students they serve, as they have a variety of missions, ranging from vocational training for specific industries to education in the liberal arts to specialized graduate, law, and seminary programs. About 86 percent of California’s private institutions are for‑profit, whereas the remaining 14 percent are nonprofit.

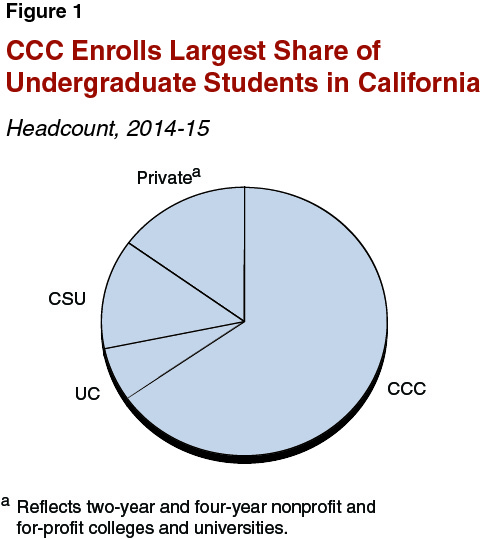

The Vast Majority of Undergraduate Students Enroll in the Three Public Systems. Altogether, the three public systems enroll 85 percent of California undergraduate students, whereas the private sector enrolls 15 percent. (On a full‑time equivalent student basis, the public sector’s share of undergraduate students is slightly lower at 80 percent.) As shown in Figure 1, the CCC system alone enrolls over half of California undergraduate students.

College Costs

College Costs Consist of Tuition and Living Expenses. College costs include the tuition and fees that pay for a student’s education. In addition, students incur costs for books and supplies to complete their coursework. While they attend college, students also incur living expenses, such as for housing, food, and transportation.

Tuition Varies Considerably Across Institutions. Two main reasons account for variation in tuition. First, an institution’s mission affects its education costs. In particular, four‑year and research institutions tend to have higher education costs than two‑year and nonresearch institutions. This is primarily because faculty tend to receive higher pay while teaching fewer courses at four‑year and research institutions. Second, public institutions tend to charge lower tuition than private institutions because the state subsidizes a portion of their education costs. Figure 2 shows tuition charges for each public system in California and two types of private institutions.

Figure 2

Tuition in California Varies Considerablya

2015‑16

|

Type of Institution |

Average Tuition |

|

Nonprofit, four‑year |

$29,319 |

|

For‑profit, two‑year or less |

17,573 |

|

University of California |

13,451 |

|

California State University |

6,815 |

|

California Community Colleges |

1,380 |

|

aReflects tuition and required fees charged to first‑year, undergraduate resident students taking 30 units. Averages across private institutions are based on data reported to the federal government, not weighted by student enrollment. |

|

Living Expenses Vary by Living Arrangement . . . Living expenses can vary depending on whether a student lives (1) with family, (2) off campus, or (3) on campus. Generally, students living with family incur the lowest costs because their families tend to help subsidize some or all of their two largest living expenses—housing and food. Of the other two living arrangements—living off‑ or on‑campus—which is more expensive depends primarily on per‑student housing costs. Figure 3 shows how average living expenses at UC vary by living arrangement. The UC system estimates students living with family face by far the lowest costs—about 30 percent lower than students living off campus and almost 50 percent lower than students living on campus.

Figure 3

Living Expenses Vary by Student Living Arrangement

University of California, 2015‑16

|

On Campus |

Off Campus |

Living With Family |

|

|

Rent and food |

$14,199 |

$9,391 |

$4,700 |

|

Health carea |

2,130 |

2,169 |

1,818 |

|

Transportation |

687 |

1,247 |

1,659 |

|

Otherb |

1,700 |

1,884 |

2,032 |

|

Totals |

$18,716 |

$14,691 |

$10,209 |

|

aPrimarily reflects health insurance costs. Students insured through a family member are not required to purchase insurance. bIncludes expenses for clothing, entertainment, and recreation. |

|||

. . . And by Institution. Except for on‑campus room and board prices, institutions do not determine students’ living expenses. Instead, they use various methods to estimate those costs. Their estimates vary due to regional differences in cost of living as well as methodological differences in the way they make their estimates. Regarding methodology, one institution, for example, might survey its students to find out how much they spend on living expenses, whereas another institution might collect data on average living costs in the area.

Back to the TopFinancial Aid

Financial Aid Helps Students and Families Pay College Costs. The federal government, state government, most higher education institutions, and some private organizations offer financial aid to students and families. Financial aid programs may be need based (for students who otherwise might be unable to afford college) or nonneed based (typically based on academic merit, athletic talent, or military service). Types of financial aid include gift aid (grants, scholarships, and tuition waivers that students do not have to pay back); loans (that students must repay); federal tax benefits (that can reduce income tax payments or provide a tax refund); and subsidized work‑study programs (that make it more attractive for employers to hire students). A sizeable body of research indicates that gift aid can increase college attendance and, in some cases, improve persistence and completion. Much less research exists on the effects of other types of aid.

Many Financial Aid Programs Available for California Students. Figure 4 shows the main aid programs available to California college students. If a student qualifies for more than one program, then campus financial aid offices “package” together aid for the student. Generally, a student’s aid package cannot exceed his or her estimated college costs (tuition and living combined). When packaging aid, campuses first prioritize awarding gift aid before moving on to awarding loans and work study. Campuses do not award tax benefits. Students and parents claim these benefits on their tax returns.

Figure 4

Major Financial Aid Programs for California Undergraduates

(In Billions)

|

Program |

Source |

Expendituresa |

|

Gift Aid |

||

|

Pell Grant |

Federal |

$4.0 |

|

Cal Grant |

State |

1.9 |

|

Military/veterans programs |

Federal |

1.8b |

|

CCC Board of Governor’s Fee Waiver |

State |

0.8 |

|

UC Grants |

State |

0.8 |

|

CSU State University Grant |

State |

0.6 |

|

Supplemental Education Opportunity Grant |

Federal/colleges |

0.1 |

|

Middle Class Scholarship |

State |

—c |

|

CCC Full‑Time Student Success Grant |

State |

—c |

|

Private college institutional aid |

Colleges |

—d |

|

Loans |

||

|

Direct Student Loans |

Federal |

3.9 |

|

Parent PLUS Loans |

Federal |

0.9 |

|

Perkins Student Loans |

Federal |

0.1 |

|

Tax Benefits |

||

|

Tuition credits and deductions |

Federal |

2.8b |

|

Coverdell education savings account |

Federal/state |

—c |

|

Scholarshare savings plan |

Federal/state |

—d |

|

Work Study |

Federal/colleges |

0.1 |

|

a2014‑15 for federal programs and 2015‑16 for state programs. bIncludes expenditures on graduate students. cLess than $50 million. dData not available. |

||

Most Public Aid Programs in California Geared Toward Paying Tuition. Of the six state gift aid programs shown in Figure 4, three pay only for tuition (the CCC Board of Governor’s Fee Waiver, the CSU State University Grant, and Middle Class Scholarships). Additionally, about 85 percent of spending from the state’s main aid program (Cal Grants) pays for tuition, as does about two‑thirds of spending from UC’s grant program. Collectively, these programs cover full tuition for about half of students at CCC, CSU, and CCC. (The remaining state program listed in the figure, the CCC Full‑Time Student Success Grant, covers only book/supplies and living costs, as students receiving this grant already pay no education fees.)

Most Public Aid Programs Target Financially Needy Students but Programs Differ in Several Ways. Most state and public institutional aid programs require a student to demonstrate financial need based on a calculation developed by the federal government. (The box below provides more detail on the federal need calculation.) Some state and institutional aid programs, however, assess need using alternative methods. Moreover, even the aid programs using the federal need calculation tend to have additional eligibility criteria that distinguish them from each other. For instance, the Cal Grant program requires students to have need based upon the federal calculation but then applies program‑specific income and asset ceilings. Additionally, award amounts vary by program, with some programs only paying for a portion of tuition, some paying for full tuition, some paying for living expenses, and some paying a combination of tuition and living expenses.

Back to the Top

Federal Assessment of Student Financial Need

Students Must Submit Federal Aid Application to Access Most Need‑Based Aid Programs. Most need‑based financial aid programs—regardless of whether they are run by the federal government, state government, or an institution—require a student to file a Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA). The FAFSA collects detailed financial information on income and assets as well as a student’s family circumstances (such as household size). It becomes available each October for the upcoming academic year. The deadline for filing the FAFSA varies by program. California’s state‑run aid programs have a deadline of March 2.

Federal Government Uses FAFSA to Calculate “Expected Family Contribution.” Federal law sets forth a formula that calculates an expected family contribution (EFC) based on the FAFSA. As the name suggests, the EFC is how much the federal government expects a family to be able to pay for college each year. The EFC can be as low as zero—meaning the federal government does not expect the family to pay anything. For dependent students (generally those under age 24), the EFC consists of an expected parent contribution plus an expected student contribution. For independent students (generally those over age 24 or married), the EFC is based only on an expected student contribution.

Expected Family Contribution Based on Multiple Factors. The EFC formula is somewhat complicated. For a dependent student, the EFC formula starts with the parents’ and student’s adjusted gross income as reported on federal tax forms. It then makes certain adjustments to income. For example, the formula deducts a certain amount from parent income based on household size (with a larger deduction for larger families). It also deducts a fixed amount from the student’s income. The remaining income after these adjustments is deemed “available income.” Next, the EFC formula totals certain types of assets, such as cash and checking accounts (but not primary residences or retirement accounts). For the parent contribution, the EFC formula then (1) excludes a portion of assets based on age and other factors, (2) adds 20 percent of the value of the remaining assets to “available income,” (3) calculates a contribution from the total available resources based on income level, and (4) divides this contribution by the number of children in college. For the student contribution, the EFC formula (1) calculates a contribution from income that equals 50 percent of “available income” and (2) adds 20 percent of the student’s assets. The expected parent and student contributions are then summed to get the expected family contribution. The EFC formula uses a somewhat similar methodology for independent students. The figure below provides a simplified illustration of how the EFC is calculated for two dependent students—one with parent income of $35,000 and no student income and another with parent income of $105,000 and student income of $7,500.

Examples of Expected Family Contributiona

|

Example 1 |

Example 2 |

|

|

Expected Parent Contribution |

||

|

Incomeb |

$35,000 |

$105,000 |

|

Allowancesc |

‑33,468 |

‑53,523 |

|

Available Income |

$1,533 |

$51,478 |

|

Assetsd |

5,000 |

50,000 |

|

Allowancese |

‑19,700 |

‑46,364 |

|

Available Assets |

— |

$ 3,636 |

|

Total Available Resources |

$1,533 |

$55,114 |

|

Parent Contributionf |

$337 |

$19,475 |

|

Expected Student Contribution |

||

|

Incomeb |

$2,000 |

$7,500 |

|

Allowancesc |

‑6,553 |

‑7,237 |

|

Contribution From Income |

— |

$263 |

|

Assetsd |

— |

3,000 |

|

Allowancese |

— |

‑2,400 |

|

Contribution From Assets |

— |

$600 |

|

Student Contribution |

— |

$863 |

|

Expected Family Contribution |

$337 |

$20,338 |

|

aBoth examples are for a family of four with two parents (both working), both age 50, with one child in college. Examples are for illustrative purposes only. |

||

|

bGenerally based on adjusted gross income. Also includes untaxed income (such as contributions to pension plans) and a few other income sources, such as education tax credits. |

||

|

cFor both parents and students, includes income and Social Security taxes paid. For parents, also includes (1) an “income protection allowance” that varies based on income, household size, and number of children in college and (2) an “employment expense allowance” that varies by income and number of parents working. For students, includes a fixed “income protection allowance” of $6,400 and 50 percent of income above this threshold. |

||

|

dFrom savings accounts and investments. Excludes primary residence and retirement accounts. |

||

|

eFor parents, varies based on number of parents and age of older parent. For students, equals 80 percent of assets. |

||

|

fReflects a percentage of parents’ available resources that varies based on available resources. Equals 22 percent in first example and 31 percent in second example. |

||

Expected Family Contribution Used to Determine Eligibility for Need‑Based Aid. A student can qualify for need‑based financial aid up to the difference between his or her college cost (tuition and living combined) and EFC. (If the student’s EFC exceeds the cost of college, then the student is not eligible for any need‑based aid.) This does not guarantee, however, that the student will receive this amount of aid. The student still must meet any other aid program eligibility criteria and, even so, the student still might not receive a full aid package, as many aid programs have limited funding. Financial aid officers consider financially needy students who receive insufficient financial aid to pay for all their college costs to have “unmet need.”

Some Concerns Expressed Regarding Expected Family Contribution Calculation. Some students and families argue the EFC formula does not exclude enough income to reflect the actual cost of living. Specifically, critics note the federal government tends to set the EFC formula based on how much it desires to spend on federal grants, rather than an assessment of how much students and families can afford to pay. Others believe the formula understates the amount middle‑ and higher‑income parents can contribute because it excludes certain asset categories. Additionally, some critics suggest the EFC formula is flawed because it does not account for regional differences in cost of living.

Gift Aid Significantly Lowers College Costs in California. The average net price for gift aid recipients attending California colleges is much lower than total college costs. For instance, college costs for a student living on campus total about $33,000 at UC, but the average gift aid recipient receives about $16,000 in aid—effectively cutting college costs about in half.

Back to the TopStudent Loan Debt

Certain Students More Likely to Borrow and Accumulate More Debt. In California, about one‑third of full‑time freshmen take on student loans, and just over half of students graduating have student loan debt. Students attending private institutions are both somewhat more likely to borrow and accumulate more debt than students attending public institutions. For instance, 61 percent of students attending private, nonprofit four‑year institutions graduate with debt averaging $27,500, compared to 53 percent of graduates at CSU and UC with debt averaging $19,500. Students attending CCC are far less likely to borrow than their peers at four‑year institutions, with only 2 percent taking out loans each year, borrowing an average $5,000. Additionally, low‑ and middle‑income students tend to borrow more to finance their education than their higher‑income peers. For example, at UC, just over 50 percent of students from families earning less than $54,000 annually take out student loans, compared to 15 percent of students from families earning over $161,000. (The student debt figures cited throughout the report exclude other forms of debt, such as credit card debt.)

Most Student Loan Debt Issued by Federal Government. The federal government has long played a predominant role in student lending. In California, 89 percent of the debt held by graduating students each year is issued by the federal government, with the remaining 11 percent coming mainly from private lenders. Students attending public institutions in California make even greater use of federal loans compared to other loans. For instance, at UC, 94 percent of student loan dollars come from the federal government.

Default Rates on Federal Loans Tend to Vary by Type of Institution. For each cohort of undergraduate borrowers entering repayment in a given year, the federal government tracks the percentage of students defaulting within three years, by institution. The average rate for California institutions is 10.4 percent (compared to 11.3 percent nationally). Default rates tend to be higher for students attending two‑year institutions and for‑profit institutions, while they tend to be lower for students attending four‑year institutions and nonprofit institutions. Among California’s three public higher education systems, three‑year student loan default rates tend to be highest at CCC campuses and lowest at UC campuses. Specifically, while the vast majority of CCC campuses have rates in excess of 10 percent, no CSU campus has a rate greater than 6.7 percent and no UC campus has a rate greater than 3.6 percent.

Federal Government Increasing Efforts to Make Loan Repayments Manageable. The federal government historically only offered three loan repayment plans. The payments under these plans differed, but none of the plans were based on a borrower’s ability to make the payments. In more recent years, the federal government has expanded its repayment plan offerings to include a number of “income‑driven” repayment plans. Unlike the traditional loan repayment plans, income‑driven repayment plans vary payments based on the income of the borrower as a way to improve affordability and reduce the likelihood of a student defaulting. For example, the Pay As You Earn Repayment Plan caps monthly payments at 10 percent of a borrower’s discretionary income (defined as income earned above 150 percent of the poverty level, adjusted for location and household size). Income‑driven repayment plans also forgive any remaining loan balances after a set period (unless the borrower defaults on the loan). For example, the Pay As You Earn Repayment Plan forgives balances after 20 years. Figure 5 summarizes the four income‑driven loan repayment plans offered by the federal government and compares them to the three traditional repayment plans. In addition to these repayment plans, the federal government has a Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program that forgives loan balances after ten years for borrowers working for a public or nonprofit employer.

Figure 5

Seven Repayment Plans Available for Federal Student Loansa

|

Plan |

Monthly Payment |

Repayment Period |

|

Income‑Driven Plansb |

||

|

Pay As You Earn |

10 percent of discretionary income |

Up to 20 years |

|

Revised Pay As You Earn |

10 percent of discretionary income |

Up to 20 years |

|

Income Based |

10 percent of discretionary incomec |

Up to 20 years |

|

Income Contingent |

20 percent of discretionary incomed |

Up to 25 years |

|

Traditional Plans |

||

|

Standard |

Fixed |

10 years |

|

Graduated |

Lower at first, then increases |

10 years |

|

Extended |

Fixed or graduated |

25 years |

|

aFor undergraduate borrowers in the federal Direct Loan program, the main undergraduate loan program. bPayment must be less than payment under Standard plan to participate in Income Based and Pay As You Earn plans. For all plans, loan balances are forgiven at the end of repayment period. Discretionary income is the difference between a borrower’s income and 150 percent of the poverty level (100 percent for the Income Contingent plan). cFor borrowers taking out their first federal loan after July 2014. Other borrowers pay 15 percent of discretionary income and have a 25‑year repayment period. dPayment also can be based on a 12‑year repayment plan, adjusted for income. |

||

Creating a Debt Free College Program in California

This section of the report focuses on various features of a potential new debt free college program in California. We first discuss a financial concept known as “shared responsibility,” which is a key idea underlying debt free college programs. Next, we identify our key assumptions in designing such a program in California, provide the associated cost estimate, explore a few other program considerations, and then set forth options for administering and phasing in the program. Based on our understanding of legislative intent, we assume the program operates only at public colleges in California, though we discuss in a box at the end of the report how the program could work if it also were to operate at private colleges in California.

Shared Responsibility

Below, we explain the concept of “shared responsibility,” provide information on similar programs in other states, and discuss how such a program could affect student loan debt in California.

Debt Free College Program Based on Concept of Shared Responsibility. The debt free college program described in the Supplemental Report of the 2016‑17 Budget Act is based upon what some financial aid experts refer to as shared responsibility. A shared responsibility approach to financial aid takes total college costs and then deducts (1) a parent contribution (for dependent students only), (2) a student contribution, and (3) federal gift aid. The state then provides “last dollar” gift aid to meet any remaining unmet financial need.

Minnesota and Oregon Currently Have Shared Responsibility Aid Programs. In 1983, Minnesota became the first state to adopt a shared responsibility aid program. The state of Oregon adopted a similar program in 2007. Both states allow students to use their grants at two‑year or four‑year, public or private institutions. Both states’ programs use the same general approach to award aid, but they differ somewhat in terms of their calculations, as shown in Figure 6. Most notably, Oregon currently rations its awards due to insufficient funding to cover the program’s full costs. Neither program explicitly specifies how it expects students to make their expected contribution, whether through borrowing, work, or other means.

Figure 6

Minnesota and Oregon Shared Responsibility Aid Programs

|

Minnesota |

Oregon |

|

|

Step 1: Determine costs |

Tuition: up to a cap set in state lawa Living: set in state law |

Tuition and living: average amount charged by public institutionsa |

|

Step 2: Deduct student contribution |

50 percent of costs |

Fixed amount of costsb |

|

Step 3: Deduct parent contribution |

94 percent of federal expected parent contribution |

100 percent of federal expected family contribution |

|

Step 4: Deduct federal aid |

Actual value of Pell Grant |

Actual value of Pell Grant plus assumed federal tax credits |

|

Step 5: Calculate state grant |

Costs minus student and parent contributions and federal aid |

Costs minus student and parent contributions and federal aid |

|

Step 6: Ration awards |

— |

Flat award of $2,000 for students qualifying for at least this amount |

|

aTuition allowance is lower for students attending two‑year versus four‑year institutions. bLower for students attending two‑year versus four‑year institutions. |

||

UC’s Grant Program Also Based on Shared Responsibility. Similar to the Minnesota and Oregon programs, UC’s financial aid program starts by creating a student budget that factors in tuition and living expenses. (UC estimates living expenses based on student surveys.) It then sets an expected student “self‑help” contribution (currently averaging $9,700 systemwide for dependent students) for students to manage through work and borrowing. UC then factors in an expected parent contribution based on the federal calculation as well as available federal gift aid. Additionally, UC factors in all available state gift aid. UC then provides institutional gift aid to address any remaining unmet need. UC does not factor in merit‑based or private gift aid, thereby allowing students to apply these funds toward their self‑help contribution or their parents’ contribution.

Shared Responsibility Programs Likely to Limit but Not Eliminate Student Loan Debt. A shared responsibility program can be designed to allow a student to attend college without taking on debt. That is, a program can provide students a pathway to debt free college. Importantly, however, a shared responsibility aid program does not necessarily eliminate student loan debt for all students. Unless programs explicitly require students to make their contribution through work, some students might prefer to borrow. Also, depending on local economic circumstances, some students could experience difficulty finding employment, which could put pressure on them to borrow to meet their contribution. Parents also might fail to provide their full expected contribution, again putting pressure on students to borrow.

Back to the TopKey Assumptions

Assume Current Tuition Levels and Systems’ Estimates of Living Expenses. Various assumptions underlie our cost estimate for the new program. One of our key assumptions is that the cost of the new program is based on current tuition levels and living costs during the academic year (nine months) as estimated by CCC, CSU, and UC, with one adjustment. Specifically, we assume students living with family pay no rent. (We discuss our assumptions on summer costs below.) The Legislature could consider basing the program’s costs on somewhat different assumptions. For instance, the Legislature could create its own method for estimating living expenses and set a uniform rate. This approach would treat students more consistently across the segments and give the Legislature more control over the program’s costs.

Assume Program Applies to Students Taking At Least Six Units Per Term. Our cost estimate excludes community college students taking fewer than six units. (It does not specifically exclude CSU and UC students taking less than six units as so few of these students exist to materially affect our estimate.) We exclude these students for two reasons. First, federal aid rules generally only allow institutions to recognize a small share of these students’ living costs as college‑related costs. As a result, these students have no effect on our cost estimate because our expected student contribution exceeds their college costs. Second, we exclude these students from the calculation because the debt free college program appears primarily intended to help students complete full academic programs. Some community college students, particularly those taking fewer than six units, may not have such a goal. Instead, they may be interested in learning English, becoming citizens, enrolling in a short career technical training program, or seeking personal enrichment. Were the Legislature to include these students in the new program, it would want to develop a financial need calculation that ensured they qualified for at least some associated aid.

Assume Parent Contribution Based on Federal Formula. Because the federal expected parent contribution calculation is used for most existing financial aid programs, we assume this calculation also is used for the new debt free college program. The Legislature, however, could consider creating a state formula if it has concerns that the federal calculation does not accurately represent the amount parents can contribute.

Assume All Existing Federal Gift Available for Program. We assume the state counts all existing federal gift aid received by students toward the new program. The Legislature, however, also could consider factoring in a student’s expected federal tax credits and deductions (as done in Oregon’s program).

Also Assume Most Other Existing Gift Aid Available for Program. We assume the state counts as available for the new program existing state gift aid provided to financially needy students through the Cal Grant and Middle Class Scholarship programs and all existing need‑based gift aid provided by CCC, CSU, and UC institutional aid programs. We also count fee waivers, such as for dependents of disabled veterans. We do not include merit‑based aid or private gift aid.

Assume Standard Student Contribution Based on Research Findings . . . Research suggests that students working a moderate number of hours during the academic year do not have worse educational outcomes than nonworking students. The research, however, varies somewhat regarding the recommended maximum number of hours to work during the academic year, with studies ranging from 10 hours to 20 hours of work per week. We assume a work expectation at the midpoint of this range (15 hours per week) and we assume students earn the minimum wage. Additionally, we assume students work full time in the summer at minimum wage and live at home. We assume students incur about $1,800 in expenses during the summer for food, transportation, and personal expenses. (This estimate is derived based on the estimated expenses for these items for students living at home during the academic year.) Based on these assumptions, we assume students could contribute about $7,300 from work earnings. Figure 7 shows our expected student contribution calculation. In creating the new program, the Legislature could set the work expectation at whatever level it deemed most appropriate.

Figure 7

Expected Student Contribution From Work

|

Academic Year |

Summer |

|

|

Hours per week |

15 |

40 |

|

Wage per hour |

$10 |

$10 |

|

Earnings per week |

$150 |

$400 |

|

Work weeks |

37 |

11 |

|

Student Earnings |

$5,550 |

$4,400 |

|

Living expensesa |

$0 |

‑$1,900 |

|

Taxes |

‑$403 |

‑$335 |

|

Student Contribution |

$5,147 |

$2,165 |

|

Total Student Contribution |

$7,312 |

|

|

aLiving expenses are not deducted for students during academic year because these costs are already factored into students’ estimated college costs. |

||

. . . But Student Contribution Could Differ in Some Cases. For purposes of our estimate, we assume (1) students living at home incur no housing costs and (2) all students live at home during the summer. In reality, some students might choose not to live at home during the summer, such as independent students who are married and have families of their own. We believe the majority of students at CSU and UC, however, live at home during the summer since 66 percent of CSU aid recipients and 87 percent of UC aid recipients are dependent students. Dependent students also make up about half of aid recipients at CCC. Moreover, of the remaining half of CCC aid recipients that are independent students, 40 percent report living with parents or relatives during the academic year. For students not living at their parents’ home during the summer, the debt free college program could allow for a different student contribution that reflects both higher expected summer expenses as well additional resources, such as from a spouse’s income. In creating the new program, the Legislature also could decide whether to have different expectations regarding the contributions of dependent and independent students.

Assume Additional State Gift Aid Pays for All Remaining Unmet Need. After factoring in all other available funds mentioned above, we assume the state fully funds any remaining unmet need with gift aid. Figure 8 calculates the new award amount for two illustrative dependent students attending one of the three public systems. (The expected parent contributions used in these two examples are similar to those used in the figure on page 11 showing examples of the federal calculation.) In the first example, the student has no expected parent contribution and qualifies for a federal Pell Grant and a Cal Grant B award. The Cal Grant B award pays for tuition at UC and CSU plus a stipend of $1,656, while at CCC it pays only the stipend because the student has tuition covered through the Board of Governor’s Fee Waiver program. The student also receives a CCC Full‑Time Student Success grant and a small UC grant. Because the student already receives significant aid through existing programs, the debt free college award provides at most about $5,000 in additional aid. In the second example, the student has a much higher expected parent contribution and only qualifies for a Middle Class Scholarship at CSU and UC as well as a small UC grant. In this example, the student does not receive any aid through the debt free college program because the parent contribution, student contribution, and state and institutional aid is sufficient to cover the student’s college costs.

Figure 8

A California Debt Free College Program

Determining Grant Amounts for Two Illustrative Students

|

Dependent Student With Expected Parent Contribution of Zero |

|||

|

CCC |

CSU |

UC |

|

|

College costsa |

$19,845 |

$25,060 |

$30,345 |

|

Resources to cover college costs |

|||

|

Expected parent contribution |

— |

— |

— |

|

Expected student contributionb |

7,312 |

7,312 |

7,312 |

|

Gift aidc |

|||

|

Federal |

5,815 |

5,815 |

5,815 |

|

State |

2,256 |

7,128 |

13,950 |

|

Institutional |

1,380 |

— |

1,780 |

|

Amount of cost covered |

$16,763 |

$20,255 |

$28,857 |

|

Debt Free College grant |

$3,082 |

$4,805 |

$1,488 |

|

Dependent Student With Expected Parent Contribution of $20,000 |

|||

|

CCC |

CSU |

UC |

|

|

College costsa |

$19,845 |

$25,060 |

$30,345 |

|

Resources to cover college costs |

|||

|

Expected parent contribution |

20,000 |

20,000 |

20,000 |

|

Expected student contributionb |

7,312 |

7,312 |

7,312 |

|

Gift aidd |

|||

|

Federal |

— |

— |

— |

|

State |

— |

1,642 |

3,688 |

|

Institutional |

— |

— |

645 |

|

Amount of cost covered |

27,312 |

28,953 |

31,645 |

|

Debt Free College grant |

— |

— |

— |

|

aAssumes student lives off campus and attends East Los Angeles College, Cal State Los Angeles, or the University of California at Los Angeles. bBased on student work expectation of 15 hours per week during academic year and 40 hours per week during summer. cStudent would qualify for a federal Pell Grant. Assumes student meets academic and other eligibility criteria for a state Cal Grant. At CCC, student also would receive a waiver from enrollment fees and a Full‑Time Student Success Grant. At UC, student also would receive a Blue and Gold grant. Assumes student receives no aid from private sources. dStudent likely would qualify for a Middle Class Scholarship. Assumes student receives no aid from private sources. |

|||

Assume No Initial Changes in Student Behavior. In estimating the initial cost of the new debt free college program, we do not assume any immediate increase in total enrollment (due to more college gift aid being available), any shift in enrollment among the public systems (due to all segments becoming equally affordable), or changes in students’ living arrangements (due to all living arrangements, including living away from home, becoming equally affordable). To the extent total enrollment increased, students shifted to higher‑cost institutions, more students moved away from home, or more students otherwise opted for higher‑cost living arrangements, costs would increase. For example, costs would be over one and a half times greater had we assumed all students living with family shift to living off campus.

Back to the TopFiscal Estimate

Program Estimated to Cost Additional $3.3 Billion Dollars Annually. Of this amount, $2.2 billion is for CCC students, $800 million is for CSU students, and $300 million is for UC students. Costs vary by system primarily due to differences in the number of students they serve, as well as some variation in current levels of gift aid per student. We estimate the cost per financially needy student is $4,000 at CCC, $2,700 at CSU, and $2,400 at UC. (These amounts are on top of all existing gift aid.)

Program Costs for CCC Notably Higher Than Amount CCC Students Borrow Annually. Whereas we estimate annual program costs of $2.2 billion for CCC students, currently only 2 percent of CCC students borrow a total of about $200 million annually. This indicates that most CCC students who would qualify for the debt free college program currently already are finding ways to avoid borrowing for college. One way CCC students might be avoiding borrowing is by attending college part time and working more than the number of hours assumed in our estimate. Tellingly, the associated program cost for part‑time students (those taking more than 5 but fewer than 12 units) is $1.6 billion, whereas the program cost for full‑time CCC students (those taking 12 or more units) is $500 million. (The difference in costs between the two groups also exists in per‑student terms, with per‑student costs of $4,300 for part‑time students and $1,900 for full‑time students.) All this suggests that a debt free program would not reduce borrowing for many CCC students, but it might encourage some students to attend full time, as they could cover more of their living expenses with grant aid rather than paid employment.

Program Cost for CSU and UC Students More Similar to Amount Those Students Borrow. Whereas we estimate annual CSU and UC program costs of $800 million and $300 million, respectively, financially needy students at each respective system collectively borrow about $1 billion and $500 million annually. One potential reason program costs are less than the amounts being borrowed at each segment is that some students and parents might currently be paying more toward college costs than assumed in our estimate. Another important point to consider in comparing program costs and annual borrowing is that the debt free college program might not necessarily lead to a “one for one” reduction in student loan debt. This is because some financially needy students who would benefit from the program might not currently be borrowing. For instance, about 20 percent of UC students with family income less than $54,000 graduate with no loan debt.

Fiscal Impact of Program on State Budget Depends on Proposition 98 Treatment. State budgeting for community colleges is governed largely by Proposition 98, which establishes a minimum funding requirement for community colleges and schools, commonly referred to as the minimum guarantee. Typically, the state chooses to fund at (rather than above or below) the minimum guarantee. Currently, the state counts some but not all community college financial aid expenditures toward the minimum guarantee. If the Legislature were to fund the CCC portion of the debt free college program within the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee, it effectively would crowd out funding for other community college or school programs. If the Legislature were to fund CCC program costs outside the guarantee, it would come at the expense of other General Fund programs, unless a new revenue source is created to support the program.

Considerable Degree of Uncertainty Over Costs. Estimating the costs of a new program is often challenging due to uncertainties regarding participation. For instance, when the state created the Middle Class Scholarship program as part of the 2013‑14 budget package, it estimated the program would cost $107 million in the first year. In actuality, the program’s first‑year costs turned out to be less than half the estimated amount. The main reason the estimate was off was due to incorrect assumptions regarding how many students would qualify for the program. Though our estimate of the initial cost of a new debt free college program is based upon the best available information regarding actual costs and participation (using 2015‑16 data for CCC and 2014‑15 data for CSU and UC), actual program costs over the longer term could turn out to be notably higher or lower than our initial estimate. In particular, our estimate for CCC is subject to the most uncertainty due to various data limitations for that system, the sheer number of students involved, and the most potential for changes in students’ unit‑taking behavior.

Other Program Considerations

Below, we discuss three other considerations regarding eligibility for a potential new debt free college program. As the preceding cost estimate assumes all resident undergraduate students taking more than six units at the public systems are eligible for the new program based only on their financial circumstances, any additional eligibility criteria would reduce the programs’ costs by excluding some students. Due to data limitations, in most cases we only provide a general description of the option’s fiscal effects. We also discuss each option’s benefits and drawbacks.

Back to the TopMinimum Units

Existing Aid Programs Have Different Minimum Unit Requirements. Most existing state aid programs have a six unit requirement similar to the one we assumed in our estimate. These programs allow students to take less than a full course load (typically defined as 12 units for financial aid purposes) but pro‑rate gift aid down accordingly. However, the state’s newest financial aid program—the CCC Full‑Time Student Success Grant—has a 12 unit requirement. Students taking less than 12 units are not eligible for any portion of this grant.

Setting a Higher Minimum Unit Requirement Would Encourage Faster Completion . . . Setting a minimum unit requirement higher than six units would encourage students to enroll in more units to maintain their financial aid eligibility. This, in turn, could lead students to complete college more quickly than otherwise.

. . . But It Also Could Exclude Certain Types of Students. Depending on the particular threshold selected, a higher minimum unit requirement could affect certain types of students differently. For instance, “nontraditional” students tend to be older and often have family and work obligations. For these reasons, the systems indicate that nontraditional students are more likely to take a part‑time course load. Setting a higher minimum unit requirement might exclude some of these students from the debt free college program. The program by design, however, limits the amount of time students are expected to work, such that a higher minimum unit requirement should only affect students who enroll part time for reasons besides work.

Effects of Higher Minimum Unit Requirement Could Vary. Setting a minimum 12 unit requirement likely would have little effect on UC program eligibility, as most UC students enroll full time. Setting a 12 unit limit would affect some CSU students, as about 15 percent of CSU students currently take fewer than 12 units. The impact on eligibility for CCC students likely would be somewhat larger, as about one‑third of CCC gift aid recipients take more than 5 but fewer than 12 units. Were these students to remain part‑time and be excluded, CCC program costs would drop by $1.6 billion.

An Alternative Approach Would Be to Vary Expected Student Contribution by Units Taken. Rather than having a minimum unit requirement, the debt free college program could vary the expected student contribution based on the number of units taken. For instance, students taking between 6 and 12 units might be expected to work 30 hours (rather than 15 hours) per week during the academic year. This would account for the fact that these students are spending less time in class and therefore have more time available to work. The fiscal effects of such a policy could be notable, particularly at the CCC system. Under this particular example, costs would be lowered at the CCC system by $1.6 billion, if students remained part time and generally no longer qualified for aid under the new program because of their larger earnings expectation. Savings would be less if the state set a lower work expectation for all these students or set a lower expectation for the amount of earnings independent students applied to their college costs.

Back to the TopTime Limits

Many Existing Aid Programs Have Time Limits. For example, the state’s Cal Grant program has a four‑year time limit, while the federal Pell Grant program has a six‑year limit.

Existing Aid Programs’ Limits Typically Based on Units. Both the Cal Grant and the Pell Grant program set their limits in terms of full‑time equivalent study (and define full‑time as taking 12 or more units). As a result, the time limits do not necessarily correspond to length of the calendar or academic year. A student could use up their program eligibility in less than four years if they enroll in summer term, whereas a student taking a part time schedule could use up their eligibility in eight years. This kind of unit‑based limit provides an incentive for students to make sure the units they accumulate satisfy their program’s requirements. Otherwise, the student risks exhausting their aid and still having units left to complete.

Term‑Based Limit for Debt Free College Program Provides Better Incentives. This is because the debt free college program pays for a student’s living expenses as well as tuition. As a result, under a unit‑based limit, a half‑time baccalaureate‑degree seeking student’s debt free college aid package would cover eight years’ worth of living expenses. To avoid paying for living expenses over a prolonged period of time, the state could set the time limit based on the standard number of academic semesters (or quarters) required for graduation and expect students to take a full course load to graduate on time. In other words, the state could establish a four‑semester time limit for CCC students pursuing an associate’s degree and an eight‑semester time limit for students at CSU and UC.

Time Limit Would Reduce Costs Significantly. This is because on‑time graduation rates at CCC, CSU, and UC currently are low and many students enroll for additional semesters. As a result, a sizeable share of each system’s student body could time out of the program. For instance, we estimate that about 20 percent of CSU students are beyond their fourth year.

Back to the TopAcademic Achievement

Existing Aid Programs Typically Have Academic Progress Requirements. The federal Pell Grant program requires students to maintain “satisfactory academic progress” toward a degree or certificate in order to continue receiving aid. Most state and institutional aid programs have this same requirement. The federal government allows each institution to define what satisfactory academic progress means but typically institutions set a threshold of a 2.0 grade point average. One state aid program—the Cal Grant program—also has a high school academic achievement requirement for initial eligibility.

Academic Requirement Encourages Achievement, Prioritizes Aid. An academic achievement requirement for continuing students provides an incentive for students to do well in their courses and progress through their studies so they can continue to receive aid. Similar rationales exist for an academic achievement requirement for initial eligibility, though some financial aid experts caution against basing aid decisions too heavily on high school performance. We were unable to estimate the effects of imposing an academic achievement requirement with the data available to us at the time we prepared this report, though we believe they could be significant depending on the specific criteria chosen.

Back to the TopAdministration

Two Main Options for Administering Debt Free College Program. The first option is to consolidate all existing state and public institutional aid programs into a single new aid program. The second option is to add the new debt free college program on top of existing aid programs.

Consolidated Grant Program Offers Significant Benefits . . . California currently has two major state‑run aid programs along with several institutional aid programs. Furthermore, the main state program—the Cal Grant program—itself has numerous sub‑programs. Having this many aid programs makes it confusing for students and families trying to understand what aid is available to them. Additionally, the existing aid programs are not highly coordinated and often contain different rules and requirements. Consolidating all aid into one grant program could help to make financial aid more understandable for students, families, and policy makers. It also potentially could yield some administrative efficiencies. For instance, campus financial aid offices currently estimate a student’s Cal Grant award as part of their aid packaging process, but then they must wait for the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC) to calculate and verify a student’s award before making it final.

. . . But Would Create Some Administrative Challenges. To create a consolidated program, all current spending on gift aid from state and institutional sources would be combined and distributed according to the new program’s rules. The state and the systems could experience some challenges during the transition period, as currently CSAC administers state aid programs while the systems administer their institutional aid programs. Combining these programs together likely would mean a significant shift in how public financial aid is administered in California.

Regardless of Administrative Approach Taken, Simplifying Aid Message to Students Is Critical. Experts on financial aid best practices suggest that making financial aid awards understandable to students and families is critical for aid programs to be effective at increasing access to education. Even if aid is provided through many different programs, opportunities exist to increase students’ and families’ understanding of available aid. For instance, UC several years ago created a “Blue and Gold Opportunity Plan” that tells students they will not pay for tuition if their family income is less than $80,000 and they have financial need. The Blue and Gold Opportunity Plan did not actually provide significant new aid for students as virtually all of these students already would have had their fees covered through Cal Grants or UC’s existing institutional aid program. Rather, the Blue and Gold Plan was a messaging strategy that reduced a more complex discussion of financial aid into an easily understood message. Similarly, the state could create a simplified “debt free” messaging strategy for students even if it retained all existing aid programs and created an additional aid program.

Back to the TopPhase In

Program Could Start With Tuition Coverage Only. Most state and institutional aid programs in California traditionally have focused on covering only tuition for financially needy students. This approach stems from the state’s 1960 Master Plan for Higher Education—which called for the state to pay for students’ educational costs but for students to pay for their living expenses. If the Legislature were to phase in the debt free college program by focusing first on covering only tuition for financially needy students, we estimate the program’s costs would drop significantly. This is because most financially needy students at CCC, CSU, and UC already pay no tuition.

Program Could Prioritize Recipients According to Financial Need or Type of Institution. Another option for phasing in the program is to prioritize funding for students based on their financial circumstances. For instance, students who have the lowest expected family contribution could receive the most aid. In addition, the Legislature could consider phasing in the program by establishing it at only one of the systems based on its policy objectives. For instance, if the Legislature wanted to encourage more CCC students to reduce their work hours and enroll full time, it could start with that system.

Program Could Ramp Up Award Coverage Over Multiple Years. A third option is to set a fixed budget in the initial years and ration award coverage for each student. This could be done either by assuming each student has a higher expected student contribution or by reducing each student’s award according to a sliding scale. Both approaches effectively assume that students work more or borrow to finance a portion of their education. The first approach applies this assumption uniformly across students, whereas the second approach effectively would result in students with the greatest financial need having the lowest expected student contributions.

Phasing In Could Have Various Implications for Segments. If the state fully funded the debt free college aid program in year one of implementation, all segments would experience an increase in state funding. In contrast, under certain phase‑in options, particularly very gradual phase‑in options using a consolidated grant program, UC and CSU would see some of their aid funding effectively transferred to CCC students in the initial years of implementation. Redistribution would occur because UC and CSU currently have relatively more aid funding (including their institutional aid) than need whereas CCC currently has less existing aid compared to need. As with some restructuring efforts, the Legislature could minimize the impact on UC and CSU by effectively holding them harmless from any redistribution. Such a hold harmless provision, however, would come at the expense of providing more aid to CCC students in the near term.

Back to the TopConclusion

The state and its public institutions currently provide significant gift aid to financially needy students to help them attend college. The bulk of existing state gift aid goes toward covering tuition costs. The Legislature has expressed an interest in creating a program that would provide gift aid to cover any otherwise unmet cost of college—tuition and living combined—with the objective of minimizing student borrowing. Covering living costs is not unprecedented among California aid programs. A small portion of Cal Grant aid helps California’s financially neediest students pay for nontuition costs such as books, supplies, and transportation to campus. UC’s institutional aid program also provides some of this type of support.

Despite these existing efforts, moving the overall focus in California from covering direct education costs to also covering living costs would be a significant development—both because of the significant price tag and the associated policy and implementation issues. Most notably, unlike tuition charges, the Legislature has little control over students’ living expenses and these expenses vary depending on students’ particular circumstances and preferences. Creating a program to cover these costs could create unintended consequences. For example, unless the aid program assumed the least‑cost living arrangement, many students might move away from home or choose more expensive living arrangements. Were the Legislature to move forward with creating a debt free college aid program, we encourage it to examine all these types of underlying incentives and potential consequences carefully.

Extending the Debt Free College Program to Private Colleges

California Has a Long History of Providing Aid to Students Attending Private Colleges. In 1955, the Legislature established a State Scholarship program that is the main precursor to today’s Cal Grant program. The program provided coverage for tuition and fees of up to $600 at private institutions, $84 at UC, and $45 at CSU. In the late 1970s, the Legislature consolidated the State Scholarship program and other aid programs that it had created over the years into the Cal Grant program. The Cal Grant program allowed students to use their awards at private colleges and, at some points in time, linked award coverage at private colleges to state support for public institutions. Currently, the Cal Grant program still allows recipients to use their awards at private colleges. Award amounts are set forth in state law and vary by the type of private college the student attends. Students attending private, nonprofit colleges receive awards of $9,084 whereas those attending private, for‑profit colleges receive awards of $4,000.

Two Potential Reasons for Extending Debt Free College Program to Private Colleges . . . The main rationale today for allowing students to use their Cal Grant awards at private colleges is to provide students choice over where to pursue their education. To continue fulfilling this policy objective, the Legislature could consider extending the new debt free college program to students attending private colleges. In addition to promoting choice, state financial aid in the past has been used to expand access and capacity by encouraging students to use the private sector. This is why the State Scholarship program created in 1955 provided a much higher scholarship for students attending private institutions. At the time, the Legislature was concerned about the public systems’ capacity to serve additional students. Thus, another reason why the Legislature could consider including private colleges in the debt free college program is if it wanted to alleviate enrollment demand pressures at the public systems.

. . . But Extending Program Could Add Significant Costs. Estimating the cost of extending the program to students attending private colleges is challenging because data is not readily available for certain parts of the calculation, such as data on private college students’ expected parent contributions. Notwithstanding these data limitations, we estimate extending the program to students attending private colleges could cost several hundreds of millions to over a billion dollars annually. To derive this range, we assume the state funds college costs up to the weighted average of costs at CSU and UC for students attending four‑year private colleges and at the average CCC cost for students attending two‑year or less than two‑year private colleges. Because we base our cost estimate on the subsidized tuition levels charged by the public systems and not on the actual tuition at private institutions, the program would not fully fund the typical private school students’ college costs, meaning financially needy students attending these schools could still have to borrow to finance their education.