LAO Contacts

- Managing Principal Analyst,

Resources and Environment

- Forestry and Fire, Parks, and Recycling

- Cap-and-Trade and Air Pollution

- Water and Fish and Wildlife

- Conservation and Toxics

February 15, 2017

The 2017-18 Budget

Resources and Environmental Protection

- Overview of Governor’s Budget

- Cross‑Cutting Issues

- Department of Parks and Recreation

- The Department of Fish and Wildlife

- Department of Conservation

- Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery (CalRecycle)

- Air Resources Board (ARB)

- Department of Toxic Substances Control

- Summary of Recommendations

Executive Summary

In this report, we assess many of the Governor’s budget proposals in the resources and environmental protection areas and recommend various changes. Below, we summarize our major findings. We provide a complete listing of our recommendations at the end of this report.

Budget Provides $8 Billion for Programs

The Governor’s budget for 2017‑18 proposes a total of $8.3 billion in expenditures from various sources—the General Fund, various special funds, bond funds, and federal funds—for programs administered by the Natural Resources ($5 billion) and Environmental Protection ($3.3 billion) Agencies. This total funding level in 2017‑18 reflects numerous changes compared to 2016‑17, the most significant of which include (1) decreased bond spending of $2.8 billion, largely attributable to how prior‑year bond expenditures are accounted for in the budget; (2) a reduction of $600 million in spending from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund related to shifting this funding to a “control section” of the budget act; and (3) a net reduction of $299 million from the General Fund, in large part due to one‑time funding provided in 2016‑17, such as for deferred maintenance projects.

Governor Proposes to Extend Cap‑and‑Trade Beyond 2020

The Governor’s budget proposes to spend $2.2 billion in cap‑and‑trade auction revenue on activities intended to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. However, $1.3 billion would only be spent after the Legislature enacted—with a two‑thirds urgency vote—new legislation extending the Air Resources Board’s authority to operate a cap‑and‑trade program beyond 2020. In our recent report, The 2017‑18 Budget: Cap‑and‑Trade, we provide a full assessment of the policy issues raised by the Governor’s proposal. In summary, we recommend approving the extension of cap‑and‑trade (or a carbon tax) with a two‑thirds vote in order to (1) better ensure the state meets its GHG reduction goals cost‑effectively, (2) reduce uncertainty regarding the state’s authority to auction allowances, and (3) broaden the allowable uses of auction revenues based on legislative priorities.

Water Policy Continues to Be a Focus of Budget

The budget includes several notable proposals intended to continue and extend efforts related to the recent drought and implementation of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA).

Drought‑Related Funding. While a series of winter storms has significantly increased the amount of water available for both human and environmental uses, they will not be sufficient to eliminate all of the impacts from the state’s multiyear drought. We recommend approving some of the Governor’s proposed $178 million in one‑time funding for continued drought response activities. The specific amount to approve should be based on an assessment of updated conditions later this spring, but we expect that the increase in precipitation has rendered some components of the Governor’s proposals unnecessary. We also recommend the Legislature consider providing some ongoing funding for activities that would both address current conditions and increase the state’s resilience in future droughts.

Implementation of SGMA. Effective management of its groundwater resources is a vital component of the state’s overall water management strategy, and local agencies are in a critical stage of SGMA implementation. As such, we recommend the Legislature approve the Governor’s proposals to provide additional resources to the Department of Water Resources to provide assistance to local agencies ($15 million) and the State Water Resources Control Board to conduct intervention activities ($2.3 million). We also recommend the Legislature continue to monitor and oversee implementation of the act to ensure it stays on track and to identify if additional legislative action might be needed.

Several Special Funds Face Potential Shortfalls

Many of the state’s resources and environmental protection programs are funded largely from special funds, which rely on non‑General Fund revenues, such as fees. In this report, we evaluate the fund condition of several special funds that face future budget shortfalls if actions are not taken to bring revenues and expenditures in line.

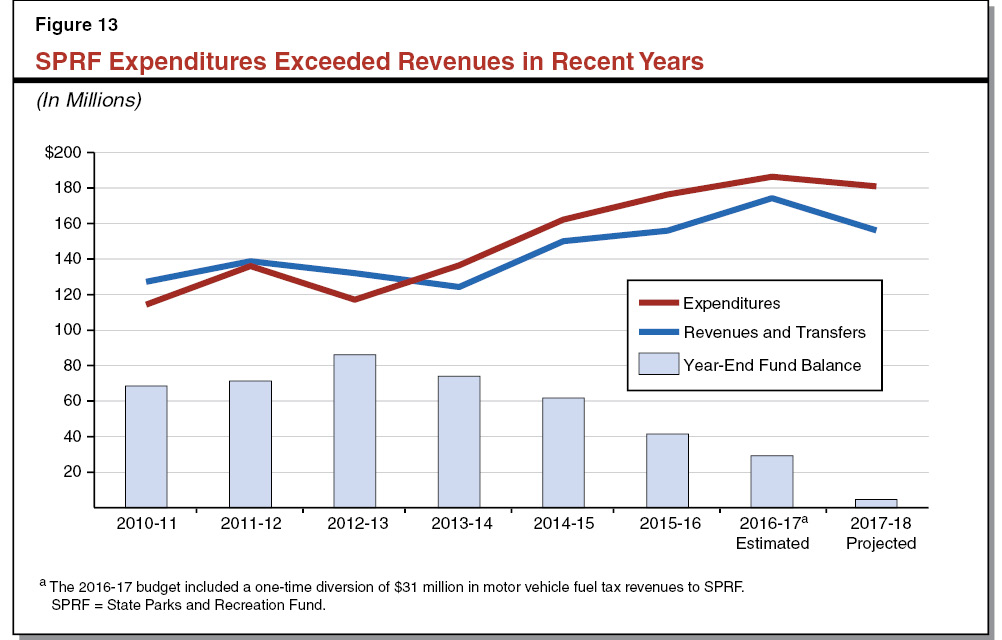

Base Funding for State Parks. The Governor proposes one‑time augmentations from the State Parks and Recreation Fund (SPRF) and the Environmental License Plate Fund to address a projected budget‑year shortfall in SPRF of $25 million. We find that these options are not available on an ongoing basis. Consequently, we recommend the Legislature begin consideration of options that would provide an ongoing budget solution to the SPRF structural deficit.

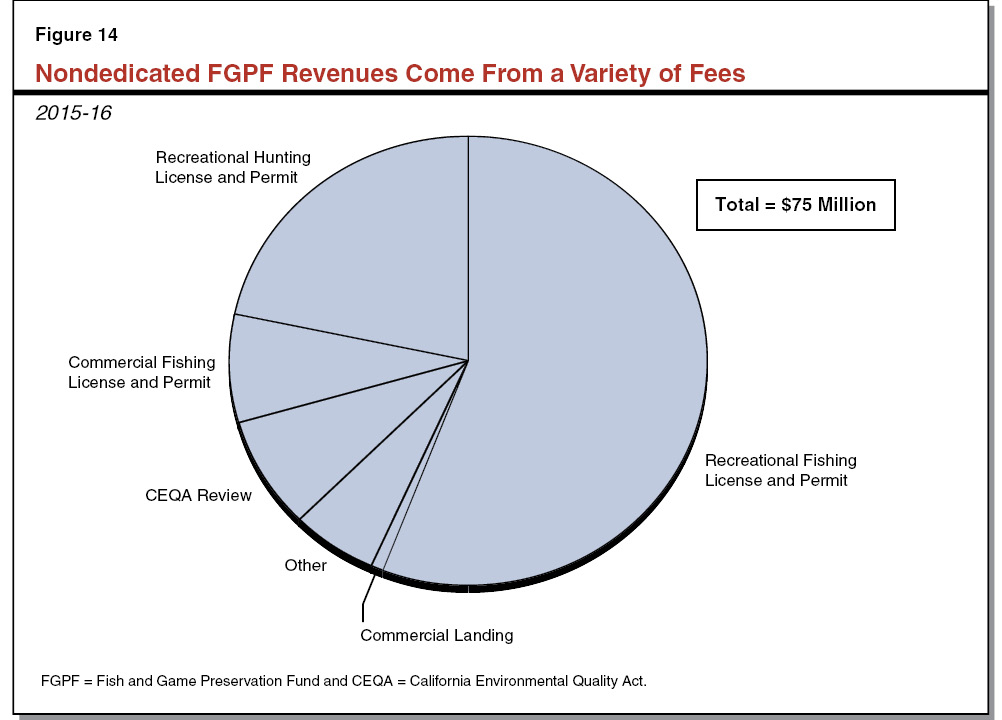

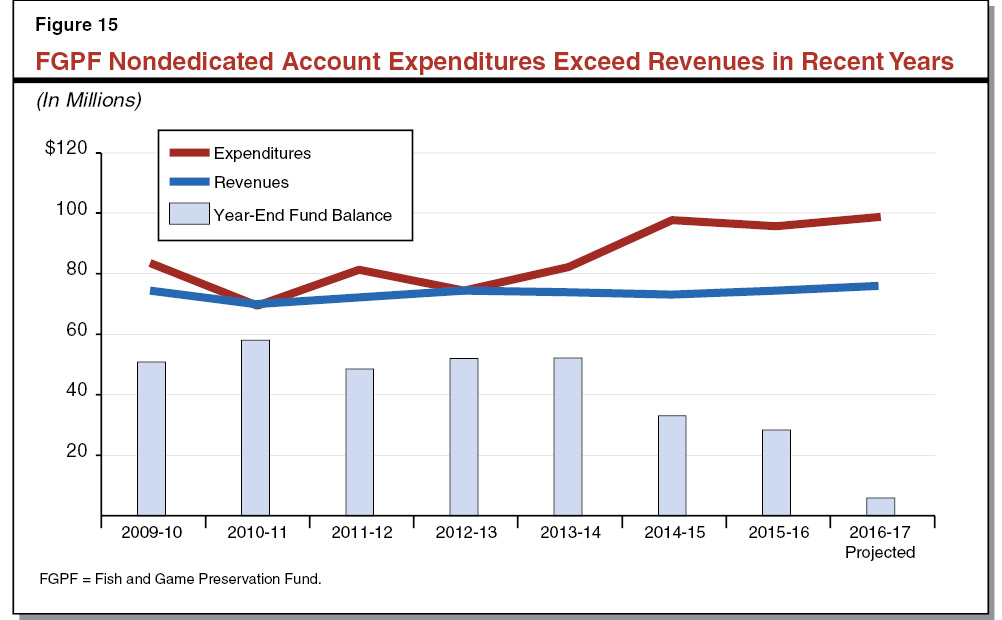

Fish and Game Preservation Fund (FGPF). We are concerned that the Governor’s proposal to address the $20 million operating shortfall in the FGPF nondedicated account: (1) includes a commercial fishing landing fee increase that may be too large for the industry to sustain and (2) adds new activities that exacerbate the account’s imbalance. Moreover, the proposals leave an ongoing shortfall for the Legislature to address in 2018‑19. We recommend the Legislature (1) adopt a commercial landing fee increase but perhaps at a lower level or more gradually, (2) adopt the Governor’s proposal to transfer lifetime license fee revenues to the nondedicated account, (3) modify the Governor’s proposals to begin two new activities by funding them on a limited‑term basis using different funding sources, and (4) begin the process of identifying and considering options for addressing the remaining shortfall on an ongoing basis.

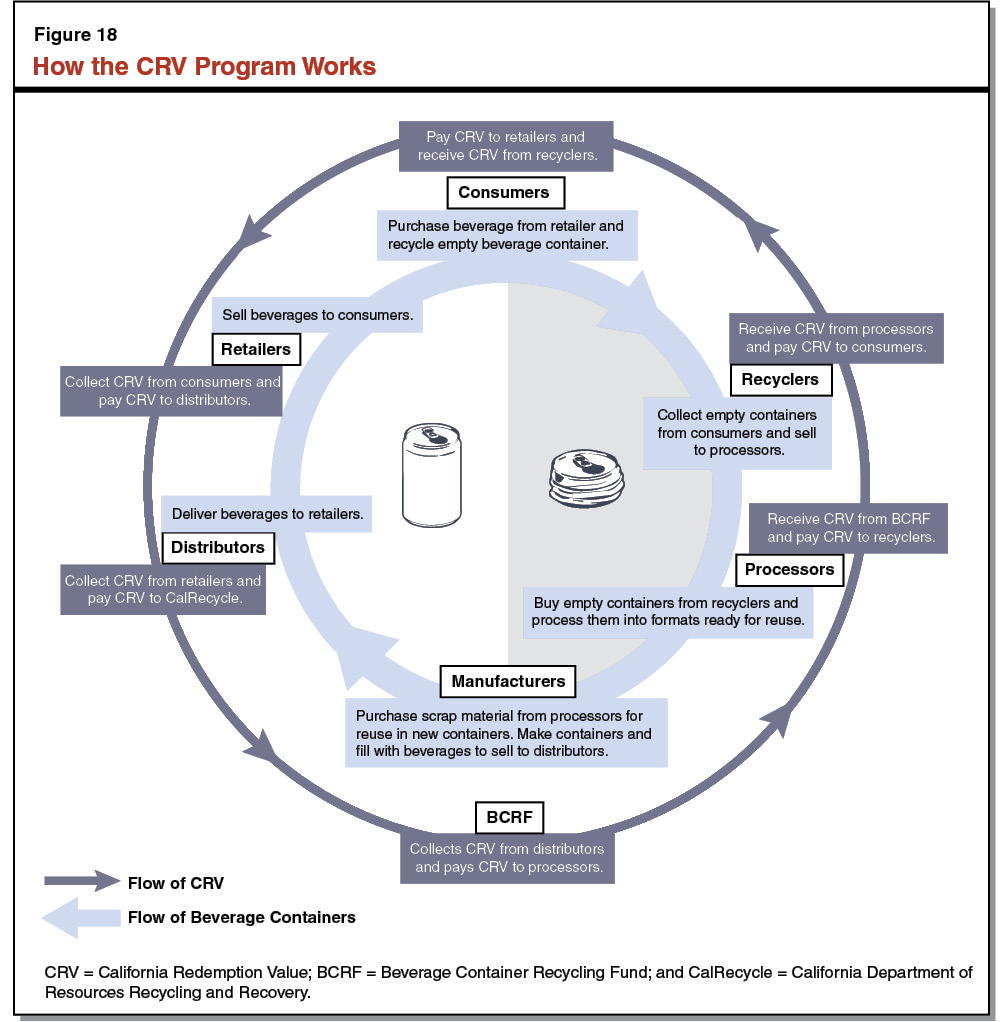

Beverage Container Recycling Program. While the budget does not include a proposal to address the Beverage Container Recycling Fund’s structural imbalance—most recently estimated at $24 million at the end of 2017‑18—the administration did release a policy paper outlining general principles and suggested approaches to addressing the problem. We find that the issues and ideas raised in the paper provide a reasonable starting place for discussion, but the Legislature will require more details in order to enact program reform.

Timber Harvest and Forestry Program. The budget includes a total of $15.2 million for three state departments to implement various forest health related programs. The administration’s proposed activities are reasonable but represent a relatively large amount of additional spending that will draw down the Timber Regulation and Forest Restoration Fund balance. We recommend that the Legislature identify program activities and grants it would prioritize and determine a funding strategy for the budget year and thereafter that reflects those priorities.

Overview of Governor’s Budget

Total Proposed Spending of $8.3 Billion. The Governor’s budget for 2017‑18 proposes a total of $8.3 billion in expenditures from various sources—the General Fund, various special funds, bond funds, and federal funds—for programs administered by the Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Agencies. Specifically, the budget includes $5 billion for resources departments and $3.3 billion for environmental protection departments.

Funding Mostly From General Fund and Special Funds. As shown in Figure 1, more than half—$2.8 billion—of the $5 billion proposed for resources departments is from the General Fund. Another $1.4 billion (27 percent) is from special funds. As shown in Figure 2, the vast majority of the $3.3 billion in funding for environmental protection programs—$2.8 billion, or 85 percent—is from special funds.

Figure 1

Natural Resources Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2015‑16 |

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

Change From 2016‑17 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Expenditures |

|||||

|

Department of Forestry and Fire Protection |

$1,306 |

$1,548 |

$1,423 |

‑$126 |

‑8% |

|

General obligation bond debt service |

970 |

1,029 |

1,002 |

‑27 |

‑3 |

|

Department of Parks and Recreation |

466 |

681 |

621 |

‑60 |

‑9 |

|

Energy Commission |

436 |

661 |

489 |

‑172 |

‑26 |

|

Department of Water Resources |

916 |

2,005 |

449 |

‑1,556 |

‑78 |

|

Department of Fish and Wildlife |

409 |

493 |

442 |

‑51 |

‑10 |

|

Wildlife Conservation Board |

116 |

502 |

124 |

‑379 |

‑75 |

|

California Conservation Corps |

95 |

95 |

119 |

24 |

25 |

|

Department of Conservation |

87 |

151 |

118 |

‑33 |

‑22 |

|

Coastal Conservancy |

44 |

143 |

55 |

‑88 |

‑61 |

|

Other resources programs |

214 |

226 |

182 |

‑44 |

‑19 |

|

Totals |

$5,059 |

$7,535 |

$5,024 |

‑$2,511 |

‑33% |

|

Funding |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$2,600 |

$3,110 |

$2,811 |

‑$299 |

‑10% |

|

Special funds |

1,283 |

1,646 |

1,359 |

‑287 |

‑17 |

|

Bond funds |

1,030 |

2,477 |

564 |

‑1,914 |

‑77 |

|

Federal funds |

146 |

302 |

290 |

‑11 |

‑4 |

Decreases From 2016‑17 Largely Reflect Technical Changes. The proposed 2017‑18 funding levels for both natural resources and environmental protection departments are significantly lower than estimated expenditures for 2016‑17. Notably, the budget shows significant decreases in spending from bond funds, special funds, and the General Fund. However, these changes largely reflect certain technical budget adjustments rather than significant programmatic changes.

- Bond Funds. Proposed bond funds are estimated to decline by a total of $2.8 billion, half for resources departments and half for environmental protection departments. Much of this apparent budget‑year decrease is related to how bonds are accounted for in the budget, making year‑over‑year comparisons difficult. Specifically, bond funds that were appropriated but not spent in prior years are assumed to be spent in the current year. The 2016‑17 bond amounts will be adjusted in the future based on actual expenditures.

- Special Funds. The 2017‑18 budget reflects reduced special fund expenditures of $552 million for environmental protection departments and $287 million for natural resources departments. However, the Governor’s budget does not include spending from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF)—which receives revenue from cap‑and‑trade allowance auctions—in the budgets of individual departments in 2017‑18 as it has in prior years. Instead, these expenditures are funded in a separate “control section” of the budget, making it appear that spending from this fund for these departments has decreased. In 2016‑17, resources and environmental protection departments are estimated to spend $600 million from GGRF. In total, the 2017‑18 budget proposes to appropriate a total of $1.3 billion from GGRF for various programs, including resources and environmental protection programs.

- General Fund. The budget for resources departments includes a net reduction of $299 million (10 percent) in General Fund support. However, much of this decrease is related to one‑time funding provided in 2016‑17, including $187 million for deferred maintenance projects. Estimated current‑year expenditures also include $45 million in additional emergency firefighting costs for the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire), an amount that is adjusted annually based on historical emergency firefighting costs.

Figure 2

Environmental Protection Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2015‑16 |

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

Change From 2016‑17 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Expenditures |

|||||

|

Resources Recycling and Recovery |

$1,687 |

$1,599 |

$1,563 |

‑$36 |

‑2% |

|

State Water Resources Control Board |

897 |

2,943 |

934 |

‑2,009 |

‑68 |

|

Air Resources Board |

698 |

844 |

401 |

‑443 |

‑53 |

|

Department of Toxic Substances Control |

220 |

248 |

272 |

24 |

10 |

|

Department of Pesticide Regulation |

91 |

99 |

96 |

‑3 |

‑3 |

|

Environmental Health Hazard Assessment |

18 |

21 |

22 |

1 |

5 |

|

General obligation bond debt service |

3 |

3 |

3 |

— |

‑4 |

|

Totals |

$3,613 |

$5,757 |

$3,291 |

‑$2,466 |

‑43% |

|

Funding |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$225 |

$90 |

$89 |

— |

— |

|

Special funds |

2,656 |

3,347 |

2,795 |

‑$552 |

‑16% |

|

Bond funds |

396 |

1,936 |

23 |

‑1,914 |

‑99 |

|

Federal funds |

337 |

384 |

384 |

— |

— |

Cross‑Cutting Issues

Cap‑and‑Trade

LAO Bottom Line. In our recent report, The 2017‑18 Budget: Cap‑and‑Trade, we provide comments and recommendations related to the Governor’s proposal to spend $2.2 billion in cap‑and‑trade auction revenue, contingent on the Legislature extending authority for cap‑and‑trade beyond 2020 with a two‑thirds vote. Figure 3 provides a summary of our recommendations.

Figure 3

Summary of LAO Recommendations

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Background

Senate Bill 32 Established 2030 Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Target. The Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 (Chapter 488 [AB 32, Núñez/Pavley]) established the goal of limiting statewide GHGs to 1990 levels by 2020. The legislation directed the Air Resources Board (ARB) to adopt regulations to achieve the maximum technologically feasible and cost‑effective GHG emission reductions by 2020. In 2016, Chapter 249 (SB 32, Pavley) established an additional target of reducing emissions by at least 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030.

Cap‑and‑Trade Aims to Limit Emissions and Encourage Cost‑Effective Reductions. Assembly Bill 32 authorized ARB to implement a market‑based mechanism—known as a cap‑and‑trade program—through 2020. Under the cap‑and‑trade program, ARB issues a limited number of “allowances” (essentially, emission permits), which large GHG emitters can purchase at a state‑run auction or on the private market. (ARB also gives some allowances away for free.) From an economic perspective, the primary advantage of a cap‑and‑trade program is that the market sets a price for GHG emissions, which creates a financial incentive for businesses and households to implement the least costly emission reduction activities.

Legal Uncertainty Around Cap‑and‑Trade. Currently, there is a court case challenging ARB’s authority to auction allowances and raise revenue through 2020. There is also legal uncertainty whether ARB has the authority to operate the cap‑and‑trade program beyond 2020 and whether extending the authority to auction allowances beyond 2020 would require a two‑thirds vote of the Legislature given changes to the definition of taxes and fees under Proposition 26 (2010).

Governor Proposes Extending Cap‑and‑Trade With Two‑Thirds Vote

The Governor’s 2017‑18 budget proposes to spend $2.2 billion in cap‑and‑trade auction revenue on activities intended to reduce GHGs. However, $1.3 billion would only be spent after the Legislature enacted—with a two‑thirds urgency vote—new legislation extending ARB’s authority to operate a cap‑and‑trade program beyond 2020. Under the Governor’s proposal, the Department of Finance (DOF) would have authority to select the specific programs within each category of activities that would receive funding. In addition, under the Governor’s proposal, DOF would have the authority to adjust downward allocations to discretionary programs proportionally based on available funds.

LAO Recommendations

In our report, we make recommendations in response to three critical questions raised by the Governor’s proposal:

- Should cap‑and‑trade be authorized beyond 2020?

- Is a two‑thirds vote needed to extend cap‑and‑trade?

- How should the Legislature use cap‑and‑trade revenue?

We summarize our recommendations below.

Authorize Cap‑and‑Trade Beyond 2020 Because Likely Most Cost‑Effective Approach. We recommend the Legislature authorize cap‑and‑trade (or a carbon tax, which is an alternative market‑based approach to reducing emissions) beyond 2020 because it is likely the most cost‑effective approach to achieving the state’s 2030 GHG emissions target. If the Legislature approves cap‑and‑trade, we recommend the Legislature (1) strengthen the allowance price ceiling because there is potential for substantial price volatility associated with the lower cap and (2) provide clearer direction to ARB regarding the criteria that the board should use to determine whether a complementary policy should be adopted. We also recommend the Legislature continue to take steps to ensure oversight and evaluation of major climate policies by establishing an independent expert committee.

Approve With a Two‑Thirds Vote to Ensure Ability to Design Effective Program. Although cap‑and‑trade could be extended with a simple majority vote, we recommend the Legislature approve cap‑and‑trade (or a carbon tax) with a two‑thirds vote because it would provide greater legal certainty and ensure ARB has the ability to design an effective program. For example, a two‑thirds vote would provide legal certainty regarding ARB’s authority to auction allowances—a method for distributing allowances that is generally recommended by economists. A two‑thirds vote would also allow the Legislature to remove the current requirement that cap‑and‑trade auction revenues can only be used on activities that reduce GHG emissions.

Broaden Allowable Uses of Revenue to Include Other Legislative Priorities. With a two‑thirds vote, we recommend the Legislature broaden the allowable uses of auction revenue because it would give the Legislature flexibility to use the funds on its highest priorities. The Legislature could use the funds to (1) offset higher energy costs for households and businesses by providing tax reductions or rebates; (2) promote other climate‑related policy goals, such as climate adaptation activities; and/or (3) support other legislative priorities unrelated to climate policy. In our view, returning the revenue to businesses and consumers by reducing taxes or providing rebates could become a particularly important option if allowance prices—and, consequently energy costs for households and businesses—increase substantially in the future.

When finalizing its 2017‑18 cap‑and‑trade spending plan, we also recommend the Legislature (1) reject the administration’s proposed language making spending contingent on future legislation, (2) consider alternative strategies for dealing with revenue uncertainty, and (3) allocate funds to specific programs rather than providing DOF that authority.

Drought Response

LAO Bottom Line. While a series of winter storms has significantly increased the amount of water available for both human and environmental uses, they will not be sufficient to eliminate all of the impacts from the state’s multiyear drought. We recommend approving some one‑time funding for continued drought response activities based on an assessment of updated conditions later this spring, but expect that the increase in precipitation has rendered some components of the Governor’s proposals unnecessary. We also recommend the Legislature consider providing some ongoing funding for activities that would both address current conditions and increase the state’s resilience in future droughts.

Background

State Has Experienced Serious Multiyear Drought. Until recent storms, California had been experiencing an exceptionally dry and warm period. Annual precipitation rates were below average for the past five years, and only one of the past ten years was exceptionally wet. Even more notably, 2012 through 2015 was the driest consecutive four‑year stretch since statewide precipitation record‑keeping began in 1896. In addition, statewide average temperatures have been higher than normal in each of the past five years, and the past three years were the warmest on record since such measurements began in 1895. Scientific evidence indicates these warmer temperatures have contributed to the severity of recent drought conditions by leading to more precipitation falling as rain rather than snow, faster melting of winter snowpack, greater rates of evaporation, and drier soils.

Drought Has Affected Various Sectors in Different Ways. The severity of the drought’s impacts across the state have varied significantly based on sector‑specific water needs and access to alternative water sources. For example, while the drought has led to a decrease in the state’s agricultural production, farmers and ranchers have moderated the drought’s impacts by employing short‑term strategies, such as fallowing land, purchasing water from others, and—in particular—pumping groundwater. In contrast, some rural communities—mainly in the Central Valley—have struggled to identify alternative water sources upon which to draw when their domestic wells have gone dry. For urban communities, the primary drought impact has been a state‑ordered requirement to use less water, including mandatory constraints on the frequency of outdoor watering.

Additionally, multiple years of warm temperatures and dry conditions have had severe effects on environmental conditions across the state, including degrading habitats for fish, waterbirds, and other wildlife; killing an estimated 102 million of the state’s trees; and contributing to more prevalent and intense wildfires.

State Has Funded Both Short‑ and Long‑Term Drought Response Activities. The state has deployed numerous resources—fiscal, logistical, and personnel—in responding to the impacts of the current drought. This includes appropriating more than $3 billion to 13 different state departments between 2013‑14 and 2016‑17. Figure 4 summarizes these appropriations by type of activity. All of this funding was initially provided on a one‑time basis, although funding for certain activities has been renewed—sometimes repeatedly—in subsequent years. State general obligation bonds (primarily Proposition 1, the 2014 water bond) provided about three‑quarters of these funds, with the state General Fund contributing around one‑fifth. The emergency response and environmental protection activities (such as fighting more frequent wildfires, providing bottled drinking water, and rescuing fish) were to meet urgent needs stemming from the current drought. In contrast, most of the water supply and some of the water conservation activities (such as building new wastewater treatment plants), which were primarily supported by bond funds, will be implemented over the course of several years, and therefore will be more helpful in mitigating the effects of future droughts. Some other water conservation activities (such as providing rebates for lawn removal or water efficiency upgrades) were intended to have noticeable effects in both the current and future droughts.

Figure 4

Recent State Drought Response Appropriations

(In Millions)

|

Type of Activity |

2013‑14 |

2014‑15 |

2015‑16 |

2016‑17 |

Totals |

|

Water supply |

$480 |

$267 |

$1,488 |

— |

$2,235 |

|

Emergency response |

108 |

213 |

183 |

$325a |

829 |

|

Water conservation |

54 |

44 |

177 |

4 |

280 |

|

Environmental protection |

2 |

60 |

— |

16 |

78 |

|

Totals |

$643 |

$584 |

$1,849 |

$345 |

$3,420 |

|

aIncludes midyear augmentation of $90 million provided from Emergency Fund for increased fire protection. |

|||||

Drought Response Has Also Included Policy Changes and Regulatory Actions. In addition to increased funding, the state’s drought response has included certain policy changes. Because drought conditions required immediate response but were not expected to continue forever, most changes were authorized on a temporary basis, primarily by gubernatorial executive order or emergency departmental regulations. For example, one of the most publicized temporary drought‑related policies was the Governor’s order (enforced through regulations) to reduce statewide urban water use by 25 percent, in effect from May 2015 to May 2016. (The regulations were then modified to account for available local water supplies, and were recently extended through November 2017 unless repealed sooner.) In response to a subsequent executive order, state agencies are in the process of developing a comprehensive plan—“Making Water Conservation a California Way of Life”—to increase statewide water efficiency on an ongoing basis. State regulatory agencies also have exercised their existing authority in responding to drought conditions. For example, the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) has ordered and enforced that less water be diverted from some of the state’s rivers and streams, and the Department of Fish and Wildlife (DFW) has closed some streams and rivers to fishing.

Recent Storms Have Dramatically Improved Conditions . . . A series of winter storms between October 2016 and February 2017 has brought significant precipitation to California and will undoubtedly help ameliorate some of the drought symptoms that have plagued the state for several years. As of the beginning of February 2017, most of the state’s large reservoirs held more than their historical average levels for that date, after measuring well below average for the past several years. Moreover, as of the beginning of February, the water content in the state’s snowpack measured 173 percent of the historical average for that date, compared to a low of 19 percent in 2015. This is particularly significant, as runoff from the mountain snowpack typically provides about one‑third of the state’s annual residential and agricultural water supply. Additional water flowing through the state’s rivers and streams will begin to address both the human and environmental impacts of recent shortages.

. . . But Certain Drought Impacts Linger. While this year’s boost in precipitation will increase the amount of water available for both human and environmental uses, it will not be sufficient to eliminate all of the drought’s impacts. Most notably, while increased availability of surface water should help stem groundwater pumping rates in the coming year, it likely will take many years of both natural and engineered replenishment to reestablish groundwater levels. Groundwater depletion has left some communities—primarily in the Central Valley—without a safe drinking water supply. Moreover, existing surface water supplies in some areas of the state—especially in the Santa Barbara region—are still dangerously low. As of early February, the U.S. Drought Monitor still classified about one‑tenth of the state—focused in the southern half—as being in “severe” drought status. These lingering dry conditions continue to threaten fish and wildlife in that part of the state, including runs of steelhead trout along the southern‑central coast and in Southern California that the federal government had listed as threatened and endangered even before the most recent drought began.

Science Suggests State Will Experience More Frequent and Intense Droughts in the Future. Numerous climate models predict that warmer temperatures are indicative of future trends. For example, a recent study from researchers at Stanford University predicts that by around 2040, California’s climate will have transitioned to one in which there is nearly a 100 percent likelihood that low precipitation years will also be severely warm. This is one factor contributing to warnings from many climate researchers that the state will experience more frequent and intense droughts in the coming years.

Governor’s Proposal

Proposes $178 Million for Drought Response Activities in 2017‑18. Figure 5 summarizes the Governor’s proposals for drought response activities in 2017‑18. Generally, the proposals represent continuations of activities conducted in prior years and are proposed to be funded on a one‑time basis. As shown, the activities span five departments and total $178 million, primarily from the General Fund ($174 million).

Figure 5

Governor’s 2017‑18 Drought Response Spending Proposals

(In Millions)

|

Activity |

Department |

Amounta |

|

Fire Protection and Tree Mortality |

||

|

Expand/enhance fire protection |

CalFire |

$91.0b |

|

Disaster assistance: tree removalc |

OES |

30.0 |

|

Subtotal |

($121.0) |

|

|

Statewide Emergency Response and Coordination |

||

|

Rescue and monitor fish and wildlife |

DFW |

$8.2 |

|

Conduct drought assistance and response |

DWR |

7.0 |

|

Monitor/enforce water rights and conservation |

SWRCB |

5.3 |

|

Coordinate statewide drought response |

OES |

3.5 |

|

Subtotal |

($24.0) |

|

|

Address Drinking Water Shortages |

||

|

Disaster assistance: emergency drinking waterc |

OES |

$22.2 |

|

Provide temporary and permanent water supplies |

DWR |

5.0 |

|

Subtotal |

($27.2) |

|

|

Other Activities |

||

|

Conduct activities to assist Delta smelt |

DWR |

$3.5d |

|

Save Our Water conservation campaign |

DWR |

2.0 |

|

Subtotal |

($5.5) |

|

|

Total |

$177.7 |

|

|

aGeneral Fund unless otherwise noted. bIncludes $3 million from State Responsibility Area Fund. cCould also be used for other drought or non‑drought related disaster response activities. dIncludes $0.9 million from Harbors and Watercraft Fund. CalFire = California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection; OES = Office of Emergency Services; DFW = Department of Fish and Wildlife; DWR = Department of Water Resources; and SWRCB = State Water Resources Control Board. |

||

Majority of Funding Is for Fire Protection and Tree Mortality. About 70 percent of the proposed drought‑related funding ($121 million) is related to increased fire danger and responding to the estimated 102 million trees that have died during the drought. The largest single proposal ($91 million) would fund CalFire to hire and train firefighters, purchase and repair equipment and vehicles, and remove dead trees. The budget also includes an augmentation for the California Disaster Assistance Act (CDAA) program in the Office of Emergency Services (OES) for disaster assistance activities. This includes $30 million that could be used to provide grants to counties to remove dead or dying trees that represent a threat to public safety. Under the Governor’s proposal, these CDAA funds could also be used for any CDAA‑eligible activity related or unrelated to the drought.

Funds State Agency Drought Response and Coordination. As shown in Figure 5, the budget also proposes funding for the Department of Water Resources (DWR), SWRCB, DFW, and OES to continue various drought response activities. This includes a total of $24 million for all four agencies to coordinate statewide responses through the Governor’s Drought Task Force and to respond to emergency needs as they emerge. Such needs might include implementing temporary permits for changes in water rights and flow requirements or rescuing fish that become stranded in dangerously low or warm streams.

Includes Funding for Drinking Water, Delta Smelt, and Water Conservation Campaign. The budget includes $22 million for OES and $5 million for DWR to address emergency drinking water shortages that continue to afflict certain communities. (As noted above, CDAA funding through OES can also be used for other, non‑drought related disaster assistance activities.) Additionally, the budget proposes funding for DWR to implement a targeted effort to improve conditions for the endangered Delta smelt ($3.5 million) and conduct a statewide water conservation campaign ($2 million).

Framework for Considering Proposals

Because the state’s rainy season is still only halfway completed, it is premature to determine what drought conditions will remain and what state‑level responses will be required in 2017‑18. The significant increase in precipitation that has occurred since the Governor prepared his budget proposal, however, likely will reduce the need for some of his proposed activities and funding. Additionally, even as the state appears to be emerging from the recent drought, it faces the challenge of how to best prepare for more prevalent droughts in the future. These evolving conditions—both with current‑year precipitation and longer‑term climate—suggest the Legislature may want to modify the drought response proposal currently before it. In Figure 6, we offer a framework the Legislature could use to consider the proposal, consisting of three categories:

- Necessary Emergency Response. One‑time emergency response activities needed to address lingering drought impacts (consistent with the Governor’s portrayal).

- Build Drought Resilience. Activities that both respond to current conditions and could be continued on an ongoing basis to help build the state’s resilience for future droughts.

- Potentially Not Necessary. Activities that could be decreased or eliminated based on improved hydrologic conditions and decreased response needs.

Figure 6

LAO Preliminary Classification of Governor’s Drought Proposals

(In Millions)

|

Activity |

Department |

Necessary Emergency Response |

Build Drought Resilience |

Potentially Not Necessary |

Totals |

|

Fire Protection and Tree Mortality |

|||||

|

Expand/enhance fire protection |

CalFire |

$91.0 |

— |

— |

$91.0 |

|

Disaster assistance: tree removal |

OES |

30.0 |

— |

— |

30.0 |

|

Statewide Emergency Response and Coordination |

|||||

|

Rescue and monitor fish and wildlife |

DFW |

3.5 |

$1.0 |

$3.7 |

8.2 |

|

Conduct drought assistance and response |

DWR |

3.0 |

1.0 |

3.0 |

7.0 |

|

Monitor/enforce water rights and conservation |

SWRCB |

2.2 |

1.0 |

2.1 |

5.3 |

|

Coordinate statewide drought response |

OES |

1.7 |

— |

1.8 |

3.5 |

|

Address Drinking Water Shortages |

|||||

|

Disaster assistance: emergency drinking water |

OES |

14.0 |

— |

8.2 |

22.2 |

|

Provide temporary and permanent water supplies |

DWR |

5.0 |

— |

— |

5.0 |

|

Other Activities |

|||||

|

Conduct activities to assist Delta smelt |

DWR |

3.5 |

— |

— |

3.5 |

|

Save Our Water conservation campaign |

DWR |

— |

— |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

Totals |

$153.9 |

$3.0 |

$20.8 |

$177.7 |

|

|

CalFire = California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection; OES = Office of Emergency Services; DFW = Department of Fish and Wildlife; DWR = Department of Water Resources; and SWRCB = State Water Resources Control Board. |

|||||

In the figure, we illustrate one specific approach to how the Legislature could modify the Governor’s proposals within this framework. The amount of funding under each category is based on our analysis of the proposed activities in the context of updated hydrologic conditions. We discuss the rationale behind our classifications in more detail below.

Most Funding Addresses Lingering Emergency Needs. We expect that some drought response activities will continue to be needed despite increased precipitation and improved conditions. As shown in Figure 6, we estimate that this represents $154 million of the Governor’s drought proposals. The vast number of dead and dying trees in the state’s forests has contributed to an increased risk of wildfire and many need to be removed to improve public safety. We therefore anticipate that funding for tree removal and firefighting through CalFire and OES still will be needed in 2017‑18.

Additionally, as discussed above, drought conditions and impacts linger, particularly in the southern half of the state. As such, we expect that DWR, SWRCB, DFW, and OES will need to continue conducting some level of statewide coordination and emergency response. Given that the amount of urgent response that is needed in 2017‑18 is likely to be less than in recent years, however, one possible approach would be to provide about half of the Governor’s proposed funding for coordination and emergency response (after backing out the $3 million that we find could be made ongoing, as described below). We also anticipate a continued need for DWR and OES to address emergency drinking water needs, and for DWR to provide support for the endangered Delta smelt.

Some Proposals Address Longer‑Term Drought Resilience. While requested to be funded on a one‑time basis, our review found that certain emergency drought response activities proposed by the Governor at DWR, SWRCB, and DFW actually address ongoing needs. In addition to responding to current conditions, these activities, if ongoing, would help the state prepare for and build resilience for future droughts. Examples of proposed activities we believe could provide ongoing value include (1) data collection and analysis, including modeling various hydrologic scenarios; (2) monitoring conditions and developing resiliency approaches for how to address needs of fish and wildlife in light of climate change and recurring water shortages; and (3) implementing the administration’s long‑term water conservation plan, including supporting urban water agencies in developing local plans for sustainable water use and drought planning. Based on our initial review of the activities described in the Governor’s proposals—and considering funding the state has already provided in recent years—in Figure 6 we identified a total of $3 million, or $1 million per department, for these types of efforts.

Given Recent Increase in Precipitation, Some Proposals May Not Be Needed. We believe improved hydrologic conditions around the state have negated the need for some of the proposed drought spending—perhaps around $21 million—as there likely will be fewer urgent issues requiring state agency response. As discussed above, we find that it might be reasonable to reduce about half of proposed statewide coordination and emergency response funding for DWR, SWRCB, DFW, and OES. Prior‑year spending data suggest that OES will not need the full amount proposed to provide emergency drinking water. Thus, our preliminary classification reduces this proposed amount by $8 million. Additionally, improved water conditions across much of the state suggest one‑time funding for the statewide Save Our Water public relations campaign will no longer be needed. Rather than this short‑term effort, the state could focus on longer‑term policies for encouraging sustainable water use at the local level, as described in the administration’s conservation plan.

LAO Recommendations

Delay Decisions Until May When Statewide Conditions Are More Certain. Given ongoing storms are still affecting statewide hydrology, we recommend delaying any action on the Governor’s drought response proposals until after the May Revision. The administration has also indicated it will reexamine its proposals based on evolving conditions, and likely will submit a revised proposal for the Legislature to consider. As discussed above, while increased precipitation suggests less one‑time funding than initially proposed may be warranted, there may also be value in providing ongoing resources for certain activities. In considering its final drought response funding package, we recommend the Legislature adopt a combination of the following three actions:

- Approve Some Amount of One‑Time Funding for Continued Emergency Response. Determine which needs will continue to require statewide action despite improved hydrology. Should this include funding for OES to provide disaster assistance, we recommend restricting those CDAA funds to be used for drought‑related tree removal and drinking water—and not for non‑drought related activities—to ensure that intended outcomes are achieved.

- Consider Making Some Funding Ongoing to Increase State’s Resilience for Future Droughts. Given scientific evidence that the state is likely to experience more frequent and intense droughts in the future, identify activities that are important to addressing both the current and future droughts, and provide resources to support them on an ongoing basis. This would reduce the amount of General Fund resources available for other state purposes in future years.

- Reduce Some Funding in Recognition of Improved Hydrology and Conditions. Determine which emergency response needs will no longer be necessary.

Proposition 1—2014 Water Bond

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend the Legislature adopt the Governor’s proposal to appropriate $421 million from Proposition 1 in 2017‑18, as it is generally consistent with the bond language and with an appropriation schedule previously approved by the Legislature. We also recommend the Legislature continue to monitor Proposition 1 implementation through oversight hearings and information provided by stakeholders and the administration.

Background

Proposition 1 Provides $7.5 Billion in General Obligation Bonds. In November 2014, voters approved Proposition 1, a $7.5 billion water bond measure aimed primarily at restoring habitat and increasing the supply of clean, safe, and reliable water. Most of the projects funded by Proposition 1 will be selected on a competitive basis, based on guidelines developed by state departments. Generally, the measure prohibits the Legislature from allocating funding to specific projects.

State in Midst of Implementing Proposition 1. As shown in Figure 7, the bond provides funding for eight categories of activities. These funds will be distributed across 16 state departments (including ten state conservancies). As shown in the figure, the Legislature already has appropriated a combined $3 billion of available bond funding. The $2.7 billion for water storage projects is not subject to legislative appropriation but rather is continuously appropriated to the California Water Commission (CWC). As such, $1.8 billion in authorized Proposition 1 funding remains for the Legislature to appropriate.

Figure 7

Summary of Proposition 1 Bond Funds

(In Millions)

|

Purpose |

Implementing Departments |

Bond Allocation |

Prior Appropriations |

2017‑18 Proposed |

|

Water Storage |

$2,700 |

$10 |

$416 |

|

|

Water storage projects |

CWC |

2,700 |

10 |

416 |

|

Watershed Protection and Restoration |

$1,496 |

$792 |

$162 |

|

|

State obligations and agreements |

CNRA |

475 |

448a |

17 |

|

Watershed restoration benefiting state and Delta |

DFW |

373 |

93 |

37 |

|

Conservancy restoration projects |

Conservancies |

328 |

163 |

60 |

|

Enhanced stream flows |

WCB |

200 |

78 |

39 |

|

Los Angeles River restoration |

Conservancies |

100 |

— |

— |

|

Urban watersheds |

CNRA |

20 |

10 |

9 |

|

Groundwater Sustainability |

$900 |

$825 |

$35 |

|

|

Groundwater cleanup projects |

SWRCB |

800 |

764a |

— |

|

Groundwater sustainability plans and projects |

DWR |

100 |

61 |

35 |

|

Regional Water Management |

$810 |

$290 |

$217 |

|

|

Integrated Regional Water Management |

DWR |

510 |

87 |

214 |

|

Stormwater management |

SWRCB |

200 |

105 |

3 |

|

Water use efficiency |

DWR |

100 |

98 |

— |

|

Water Recycling and Desalination |

$725 |

$648 |

$1 |

|

|

Water recycling |

SWRCB |

725 |

598a |

— |

|

Desalination |

DWR |

51 |

1 |

|

|

Drinking Water Quality |

$520 |

$475 |

$5 |

|

|

Drinking water for disadvantaged communities |

SWRCB |

260 |

248 |

3 |

|

Wastewater treatment in small communities |

SWRCB |

260 |

227 |

2 |

|

Flood Management |

$395 |

— |

— |

|

|

Delta flood management |

DWR and CVFPB |

295 |

— |

— |

|

Statewide flood management |

DWR and CVFPB |

100 |

— |

— |

|

Administration and Oversight |

— |

$2 |

$1 |

|

|

Administrationb |

DWR and CNRA |

— |

2 |

1 |

|

Totals |

$7,546 |

$3,042 |

$837 |

|

|

aReflects reversion of some previously appropriated funds, as proposed in the 2017‑18 Governor’s Budget. bBond does not provide a specific allocation for bond administration and oversight, but allows a portion of other allocations to be used for this purpose. CWC = California Water Commission; CNRA = California Natural Resources Agency; DFW = Department of Fish and Wildlife; WCB = Wildlife Conservation Board; SWRCB = State Water Resources Control Board; DWR = Department of Water Resources; and CVFPB = Central Valley Flood Protection Board. |

||||

Of the amount available for appropriation, $1.3 billion represents funding to continue activities initiated in prior years. (Departments do not plan to submit formal funding requests in budget change proposals for these funds unless they wish to deviate significantly from the multiyear plan presented to the Legislature in prior years.) The remaining $500 million represents funding for two new activities that are not yet underway and for which the Legislature has not yet approved any appropriations: Los Angeles River restoration ($100 million) and flood management ($395 million).

Bond Implementation Subject to Certain Accountability Provisions. Proposition 1 included a requirement that the California Natural Resources Agency (CNRA) annually publish a list of all program and project expenditures on its website. Additionally, last year the Legislature enacted statutory requirement that CNRA publish an annual report summarizing bond implementation. The report is to include status updates on funding allocations, projects initiated and completed, measurable project outcomes, and common challenges and successes reported by project grantees. This annual report is due to the Legislature on January 10 but as of this publication had not yet been submitted for 2017. The administration indicates the report is in the process of being finalized and will be submitted in the coming weeks.

Governor’s Proposals

Appropriates $421 Million From Proposition 1. As shown in Figure 7, the Governor’s budget plan assumes total spending of $837 million from Proposition 1 in 2017‑18. Of this total, the administration projects that the CWC will award $416 million in grants for water storage projects. (As noted earlier, the funding for water storage projects are continuously appropriated outside of the legislative budget process.) Additionally, $421 million is proposed to be appropriated in the budget. All of these budgeted spending proposals before the Legislature represent additional funding for activities that have received initial appropriations in prior years. The largest proposal is for DWR to award $214 million in additional grants for integrated regional water management projects. This continues a program the state has also funded through previous bonds, in which local groups can apply for funding to implement water management projects on a regional scale.

No Proposals to Allocate Funding From Unappropriated Categories of Bond. Similar to prior budgets, no appropriations are yet proposed from the sections of the bond set aside for restoring the Los Angeles River or flood management projects. Discussions amongst stakeholders are still underway regarding the best way to allocate funds between the two conservancies identified in the bond for Los Angeles River restoration. The administration plans to wait to begin requesting appropriation authority for flood‑related funding until 2020‑21 because funds from previous bonds are still available for flood management projects.

LAO Assessment

Governor’s Proposal Largely Reflects Multiyear Funding Plan Presented to Legislature in Prior Years. In general, the Governor’s proposals for Proposition 1 reflect the “rollout” plan the administration presented in prior budget proposals. Our review found that deviations from that plan are relatively minor and justifiable. For example, whereas the previous plan indicated the administration’s intention to request $22 million in 2017‑18 and $3 million in 2018‑19 for SWRCB to allocate wastewater treatment grants, the actual budget‑year proposal swaps those amounts. That is, the 2017‑18 proposal is for $3 million, and the administration now plans to request $22 million in 2018‑19. This is in response to delays in allocating the nearly $230 million for this activity that has already been appropriated and a desire to avoid appropriating funding more quickly than departments can manage its allocation.

The administration has also submitted a few technical budget change proposals to the Legislature for Proposition 1 funds, mostly reclassifying small amounts of funding from local assistance to state operations for some agencies to better administer grant programs. We view these as similarly minor and justifiable changes from the original plan presented to the Legislature.

LAO Recommendations

Adopt Governor’s Proposition 1 Proposals. Because they continue implementing Proposition 1 projects consistent with the bond language and with an appropriation schedule previously approved by the Legislature, we recommend adopting the Governor’s Proposition 1 proposals for 2017‑18.

Continue Ongoing Oversight, Modify Course if Needed. We recommend the Legislature continue to monitor Proposition 1 through oversight hearings and information provided by stakeholders and the administration. This could include asking the administration to present its annual Proposition 1 implementation report, which at the time of this publication was not yet available for our review. While the Legislature approved the administration’s multiyear funding plan in previous years, it has the authority to revisit this approach each year via the annual budget act if it has concerns about bond implementation. Moreover, lessons learned from implementation of Proposition 1 can help shape potential future bonds or state programs by identifying the programs and practices that are (and are not) successful at achieving desired outcomes.

Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA)

LAO Bottom Line. Effective management of its groundwater resources is a vital component of the state’s overall water management strategy, and local agencies are in a critical stage of SGMA implementation. As such, we recommend the Legislature approve the Governor’s proposals to provide additional resources to DWR to provide assistance to local agencies and to SWRCB to conduct intervention activities. We also recommend the Legislature continue to monitor and oversee implementation of the act to ensure it stays on track and to identify if additional legislative action might be needed.

Background

Groundwater Is Important Component of State’s Overall Water Resources. Groundwater is the portion of water from precipitation that infiltrates (either naturally or deliberately) under the surface of the ground. In a sense, all groundwater starts as some form of surface water, meaning that the two types of water are integrally connected. Much like a sponge, the ground—depending on soil type—soaks up the water into underground basins available to be pumped out of the ground for human uses, such as residential purposes or agricultural irrigation. This infiltration can happen over a period ranging from several years to over a millennium. Historically, California’s groundwater provides about 30 percent of the state’s total water supply in wet years and nearly 60 percent in dry years. Groundwater may provide up to 100 percent of water supplies in communities without access to surface water or in other areas during years where surface water deliveries are not available and rainfall is scarce.

Severe Groundwater Depletion Exists in Some Areas of the State. When the rate at which groundwater is pumped out of a basin exceeds the rate at which the water is restored or “recharged,” the basin can become depleted, or “overdrafted.” While not every basin is overdrafted, overall, California uses more groundwater than is restored through natural or artificial means. Estimates suggest that on average, extractors pump about 15 million acre‑feet a year, whereas 13 million to 14 million acre‑feet seeps back into the ground through rain, runoff, irrigation, or intentional recharge efforts. This imbalance has led to several groundwater basins across the state reaching serious levels of overdraft. Specifically, based on data collected between 1989 and 2009, DWR identified 21 of the state’s 515 groundwater basins as being “critically overdrafted,” such that a “continuation of present water management practices would probably result in significant adverse overdraft‑related environmental, social, or economic impacts.” Implications of such overdraft can be serious, including failed wells, deteriorated water quality (from intrusion of seawater or other contaminants), and irreversible land subsidence that can damage infrastructure and diminish aquifers’ future water storage capacity. DWR has not identified which other basins around the state may be experiencing a lower level of overdraft—and some of these concerning impacts—but have not yet reached its definition of critical status. Moreover, groundwater pumping rates increased during the recent drought, potentially worsening the risk and prevalence of such impacts compared to when DWR conducted its analysis.

Groundwater Use Has Not Been Regulated on Statewide Basis. In contrast to its practice of monitoring and enforcing surface water rights, the state historically has not directly regulated groundwater use. (Groundwater usage in certain areas of the state, referred to as adjudicated basins, is regulated through court orders.) Indeed, for many years California was one of the only western states without a comprehensive state‑managed groundwater use permitting system. Experts argue this lack of state management has contributed to excessive groundwater extraction in some regions, resulting in the aforementioned critical levels of overdraft.

SGMA Marks Significant Change in State’s Approach. In 2014, the Legislature passed and the Governor signed three new laws—Chapters 346 (SB 1168, Pavley), 347 (AB 1739, Dickinson), and 348 (SB 1319, Pavley)—collectively known as SGMA. With the goal of achieving long‑term groundwater resource sustainability, the legislation represents the first comprehensive statewide requirement to monitor and operate groundwater basins to avoid overdraft. The act’s requirements apply to the 127 of the state’s 515 groundwater basins that DWR has found to be high and medium priority based on various factors, including overlying population and irrigated acreage, number of wells, and reliance on groundwater. (DWR will update this prioritization in future years if any of the factors change significantly—for example, if groundwater use data shows notable changes for a particular basin, or if an updated census shows significant shifts in population.) While only comprising about one‑fourth of the groundwater basins in California, the 127 high and medium priority basins account for 96 percent of California’s annual groundwater pumping and supply water for nearly 90 percent of Californians who live over a groundwater basin. The remaining basins ranked as being lower in priority—generally smaller and more remote—are encouraged but not required to adhere to SGMA.

SGMA Requires That Groundwater Be Managed Locally . . . The act assigns primary responsibility for ongoing groundwater management to local entities. Local groundwater sustainability agencies (GSAs) are responsible for developing and implementing long‑term groundwater sustainability plans (GSPs) defining the specific guidelines and practices that will govern the use of individual groundwater basins. These GSAs will be formed by a single or combination of local public agencies with existing water or land management duties, such as cities, counties, or special districts. The GSAs are vested with broad management authority, including the ability to (1) define the sustainable yield of a groundwater basin, (2) limit extractions from that basin, (3) impose fees to pay for management costs, and (4) enforce the terms established in the GSP. Basins that are already legally adjudicated are not required to form GSAs or develop GSPs, provided they can prove they are already being managed sustainably. Additionally, certain basins that can display existing plans and sustainable practices can submit alternative plans in lieu of formal GSPs.

. . . But Overseen by Two State Agencies. The legislation tasks DWR and SWRCB with discrete roles in carrying out SGMA. DWR has primary responsibility for the initial phases of implementation, including defining and prioritizing groundwater basins, collecting and disseminating data and best practices, providing technical and financial assistance to GSAs, and reviewing GSPs. Previous budgets have provided DWR with roughly $15 million annually to begin these activities; however, this initial funding was only provided through 2019‑20.

SWRCB is tasked with enforcing the law and intervening when local entities fail to follow SGMA’s requirements. Specifically, SWRCB is responsible for intervening when it designates a basin as being in “probationary status” due to (1) failing to form a GSA (referred to as an “unmanaged basin”), (2) failing to complete a GSP, or (3) developing or implementing an inadequate or ineffective GSP (one that will cause significant depletion of groundwater or interconnected surface water). SWRCB’s intervention activities may include imposing reporting requirements around groundwater extractions and use, issuing fees, assuming management responsibilities, developing interim management plans governing how groundwater may be used in the basin, and conducting enforcement actions for noncompliance. SWRCB currently receives $1.9 million from the General Fund annually for ten staff to conduct SGMA‑related activities. Over time, funding support for these positions will transfer to fee revenue as the board’s SGMA‑related responsibilities and fee authorities increase.

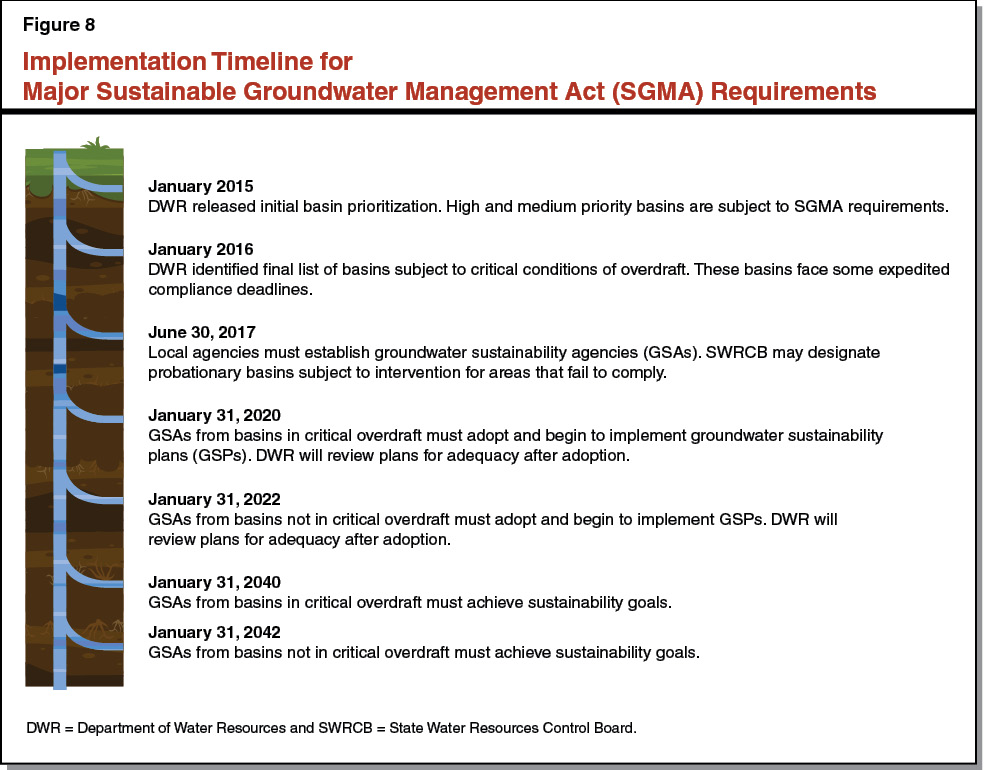

Requirements Phased in Over Several Years. Given the magnitude of the changes it entails, SGMA is designed to be implemented over a period of several decades. Figure 8 highlights the significant milestones for implementing the act. As shown, local entities currently are in the process of forming GSAs to oversee the management of individual groundwater basins, with a requirement to do so by June 30, 2017. Basins that fail to meet this deadline are subject to intervention from SWRCB. The figure also shows that the deadline for implementing a GSP is expedited for the 21 groundwater basins that DWR has defined as being in critical overdraft status—January 2020, as compared to 2022 for the remaining basins.

Governor’s Proposals

The Governor has two 2017‑18 budget proposals related to SGMA implementation that total $17.3 million, which we discuss below.

Support Local Agencies in Planning and Implementation (DWR, $15 Million). The Governor’s budget proposes an ongoing $15 million General Fund augmentation to both continue and expand DWR’s SGMA implementation activities. These funds would be in addition to the limited‑term funding—roughly $15 million a year—that the Legislature previously provided to DWR for SGMA‑related activities. (The previously approved funding will phase out over the next few years.)

DWR would use the combined roughly $30 million in 2017‑18 and 2018‑19 to accomplish activities such as assisting in the formation of GSAs, reviewing alternative management plans submitted by qualifying GSAs, and collecting and disseminating the data GSAs need to develop their GSPs. In future years, the proposed $15 million would be used for ongoing activities such as providing technical assistance to GSAs, reviewing and evaluating GSPs, monitoring groundwater levels, and continued data collection and dissemination. The department would accomplish the proposed activities within its existing position authority.

Intervene in Areas That Fail to Comply With SGMA (SWRCB, $2.3 Million). The Governor’s budget proposes five new positions and $2.3 million ($750,000 ongoing and $1.5 million on a one‑time basis) for SWRCB to assume management responsibilities in basins that fail to form GSAs by June 30, 2017. The ongoing funding and new staff would be used to establish a new SGMA Reporting Unit within SWRCB that would (1) identify groundwater users and usage rates within unmanaged basins, (2) issue and collect fees, and (3) conduct enforcement efforts for noncompliance. The $750,000 funding request is based on an estimate that five basins will fail to form GSAs and will require SWRCB intervention in 2017‑18. The number, size, and complexity of potential unmanaged basins, however, remains unknown. As such, the proposed one‑time $1.5 million would be contingency funding for the department to contract for assistance if there are significantly more than five unmanaged basins and associated workload exceeds the ongoing resources.

The proposed funding source for these activities in 2017‑18 would be a loan from the Underground Storage Tank Clean‑Up Fund to the Water Rights Fund. According to the administration, revenue from fees paid by groundwater extractors in unmanaged basins will be used to repay the loan in 2019 and provide ongoing support for program activities beginning in 2018‑19. (These fees are required under SGMA.)

LAO Assessment

Successful Implementation of SGMA Is Fundamental to State’s Management of Water Resources. The passage of SGMA was an important first step towards better groundwater management, and there are a number of reasons why successful implementation of the act’s requirements should continue to be a key state priority. First, because of the geological connectivity of above‑ and below‑ground water sources in many locations, the increased efforts the state has taken to measure, restrict, and regulate surface water usage will be somewhat ineffective if groundwater extraction is allowed to continue or increase without similarly robust oversight. Second, surface water supplies face increasing pressures from a growing population and projected reductions due to climate change, resulting in groundwater playing an increasingly important role in the state’s overall water supply. Third, possible impacts from continued overdraft of groundwater resources—including land subsidence, contamination of underground aquifers, and widespread well failures and drinking water shortages—are serious and potentially irreversible. Fourth, consistent and reliable monitoring could encourage additional efforts to recharge groundwater basins. Regional management of basins could provide individual parties with greater certainty that they would benefit from their efforts to recharge their basins without fear that the additional water would be pumped out by other parties.

SGMA Implementation at Critical Stage. As shown in the earlier figure, the next five to seven years represent a critically important period for establishing how SGMA will guide local operations and practices in future years. Local agencies must negotiate and collaborate to form functional GSAs, then undertake the difficult work of gathering and analyzing data about their areas’ groundwater use, defining sustainability targets for their basins, and developing enforceable plans and practices for how the basins can be managed to achieve those sustainability goals. The comprehensiveness and effectiveness of these processes and plans will determine the overall success of the act and of the state’s nascent efforts at comprehensively managing its groundwater resources.

State Plays Important Role in Ultimate Success of Implementation. The significant and complex workload facing local agencies in the coming years heightens the importance of assistance from state agencies during this period. In particular, the state can help by providing GSAs with baseline data to inform their GSPs. When possible, collecting data on a statewide basis—such as through remote sensing technology—can save funding by taking advantage of economies of scale, and ensure that data are valid and consistent across different areas of the state. Additionally, the state can play an important role in providing technical assistance, offering neutral facilitation services, monitoring local agency progress, and providing additional support when needed to ensure GSAs stay on track to meet deadlines. Finally, the state serving as a “backstop” if local agencies fail to meet SGMA’s requirements both raises the pressure for local compliance as well as increases the likelihood that the act’s sustainability goals ultimately will be met.

LAO Recommendations

Given the essential function that successful implementation of SGMA plays in the state’s overall approach to water management, we recommend the Legislature:

- Adopt Governor’s Proposals. Because state agencies could provide helpful assistance to local agencies during this critical implementation period, we recommend adopting the Governor’s proposals for DWR and SWRCB.

- Continue to Monitor Successes and Challenges of SGMA Implementation. Because the next several years are a decisive period of SGMA implementation, we recommend maintaining careful and regular oversight over how it is proceeding. This could include asking the administration to report on implementation status, successes, and challenges through budget and oversight hearings. To avoid delays, pitfalls, or unforeseen consequences, we recommend that the Legislature monitor whether additional state action—such as follow‑up legislation or a modification to the activities conducted by state agencies—might be warranted to stay on track and achieve sustainability goals.

Timber Regulation and Forest Restoration Program (TRFRP)

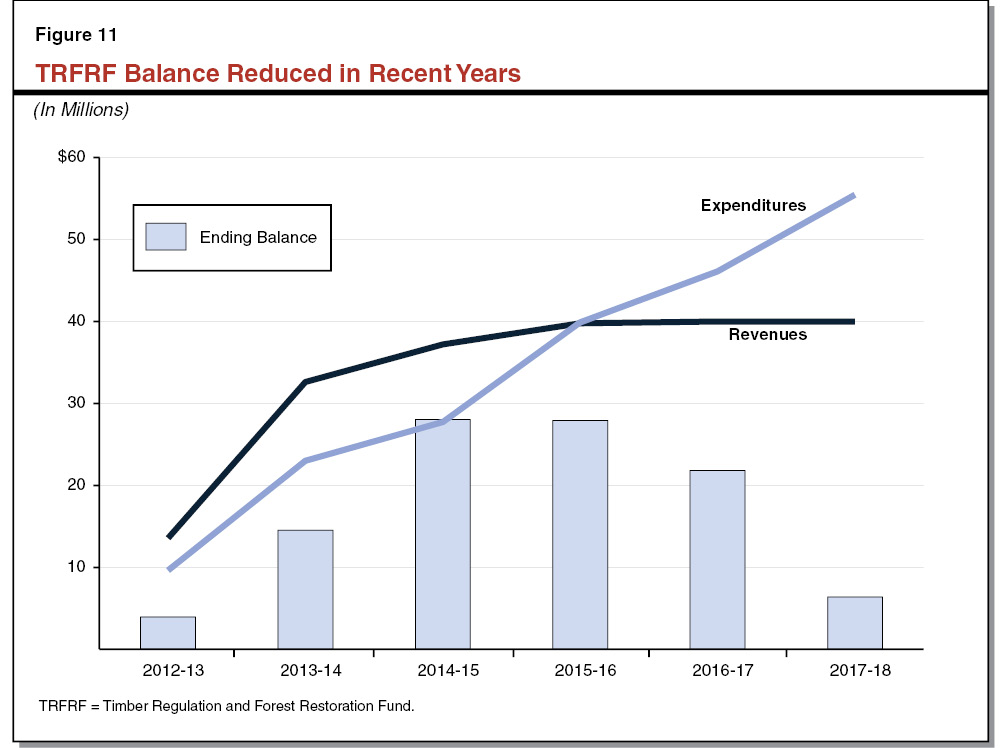

LAO Bottom Line. The budget includes a total of $15.2 million for three state departments to implement various forest health related programs. The administration’s proposed activities are reasonable but represent a relatively large amount of additional spending that would draw down the Timber Regulation and Forest Restoration Fund (TRFRF) balance. We recommend that the Legislature identify program activities and grants it would prioritize and determine a funding strategy for the budget year and thereafter that reflects those priorities.

Background

TRFRP Reviews Timber Harvest Permits. Under the state’s Z’Berg‑Nejedly Forest Practice Act of 1973, timber harvesters must submit and comply with an approved timber harvesting permit. The most common permit is a Timber Harvesting Plan (THP), which describes the scope, yield, harvesting methods, and mitigation measures that the timber harvester intends to perform within a specified geographical area over a period of five years. After the plan is prepared, TRFRP staff review and approve them for compliance with timber harvesting regulations designed to ensure sustainable harvesting practices and lessen environmental harms. CalFire takes the lead role in conducting these reviews but gets assistance from DFW, the Department of Conservation, and SWRCB. The regulation of timber harvesting is exempt from meeting certain California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) requirements, including the preparation of an environmental impact report, because this process is sufficiently equivalent to the CEQA process. The state approved 254 THPs in 2015‑16.

Lumber Assessment Established to Pay for Regulatory Activities. Prior to 2012‑13, the state’s review of THPs was funded mainly from the General Fund. In addition, DFW and SWCRB also levied a few fees for various THP‑related permits to support such activities. Total funding for THP reviews was about $25 million. However, General Fund support for THP‑related activities was reduced to less than $20 million as a result of the state’s fiscal condition during the recession. Position authority also declined during this period. For example, DFW had fewer than eight positions working on THP review in 2010‑11, a decline of over 75 percent from 2007‑08 staffing levels. Staff reductions limited the ability of administering departments to perform some required THP review activities in a timely fashion.

In 2012, the Legislature approved Chapter 289 (AB 1492, Committee on Budget), which authorized a tax on the sale of lumber products in California—effective January 2013—to fully fund THP regulatory activities. This revenue was to be used to increase staffing and reduce the amount of time it takes for departments to review THPs, as well as provide departments with additional resources necessary to perform more comprehensive THP reviews. Revenues collected from this tax are deposited into the TRFRF and are intended to fully fund the timber harvest regulatory program. In 2015‑16, the lumber assessment generated $40 million in revenues.

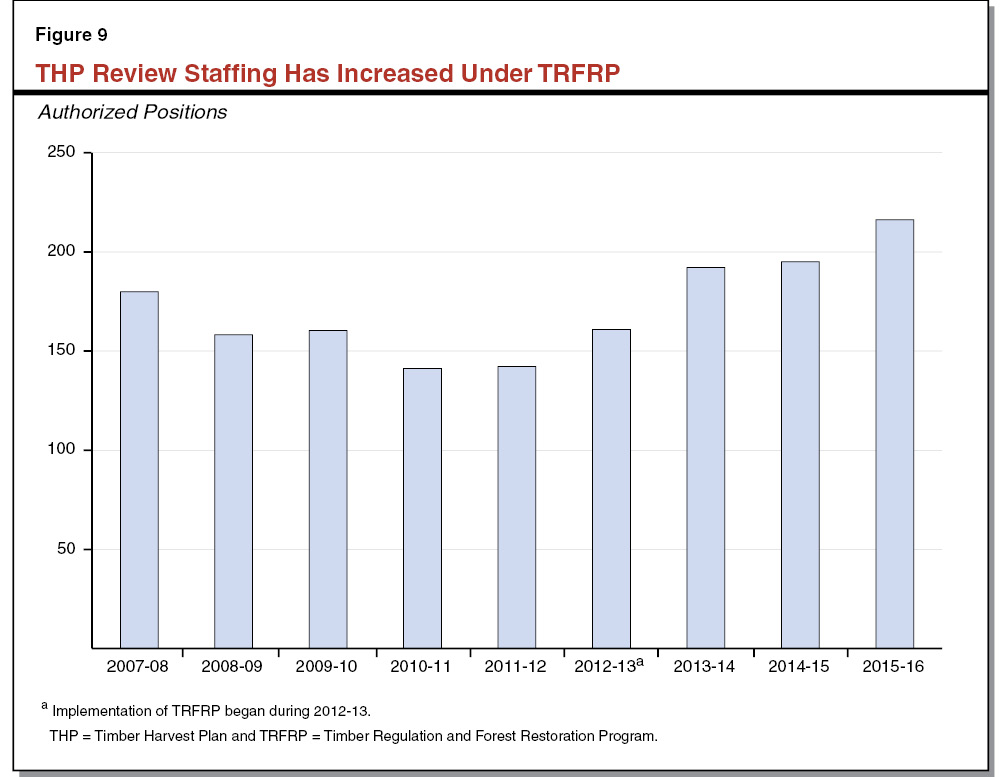

Staffing Increases Have Contributed to Faster Reviews on Average. As shown in Figure 9, staffing at the departments conducting THP review has increased under the TRFRP. Overall staffing has increased by more than 50 percent since 2010‑11, the year before the TRFRP was implemented. In fact, staffing levels are higher now than they were in the years prior to the budget cuts described above. In total, the program had 216 authorized positions in 2015‑16.

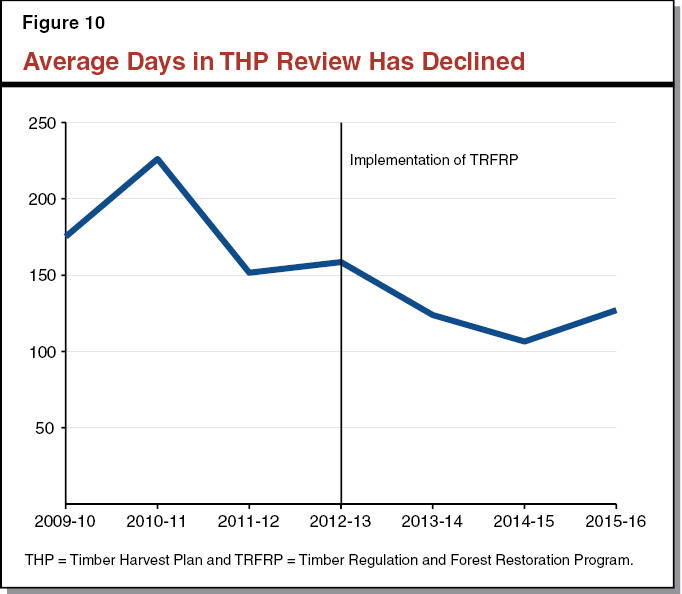

It appears that the increase in staffing has contributed to a moderate reduction in review times overall. Since the program was established, the average review time for THPs has declined from more than 150 days in 2011‑12 to 127 days in 2015‑16 (a 16 percent decline), as shown in Figure 10. In addition, the maximum number of days a THP is in review and the median review time have also declined since the TRFRP was implemented in 2012‑13. Notably, reduced review times have occurred even though, according to the departments, they have undertaken more comprehensive plan reviews. It is also important to note that other factors could be affecting average review times, such as the size and complexity of the THP, weather and wildfire conditions that can affect departments’ ability to perform inspections, and the completeness of the information submitted.

TRFRP Also Supports Forest Health Activities. Assembly Bill 1492 specifies that in addition to funding regulatory costs (and maintaining a minimum $4 million reserve), revenue from the TRFRF can be spent on specific programs to improve forest health and promote climate change mitigation or adaptation in the forestry sector. In 2016‑17, about $7.5 million—or roughly one‑fifth of the TRFRP budget—is budgeted for local assistance grants for forest restoration. The largest program is the California Forest Improvement Program (CFIP) run by CalFire, which currently receives about $5 million from TRFRF. CFIP reimburses part of the costs for smaller landowners (between 20 and 5,000 acres) to conduct certain forest health activities on their land, such as preparing management plans, tree planting, land conservation, and improvement of fish and wildlife habitat. In 2015‑16, this program provided 96 grants to treat 35,000 acres of forest land.

The rest of the TRFRF local assistance funding is administered by DFW and SWRCB and supports grants to nonprofits and local governments, primarily for restoration of habitat and watersheds. For example, in 2015‑16, funding for SWRCB supported four projects for habitat restoration and watershed assessments and planning.

Governor’s Budget

The Governor’s budget includes three proposals supported from TRFRF that total $15.2 million in 2017‑18, declining in subsequent years to $4.4 million annually beginning in 2019‑20.

Forest Restoration and Accountability ($9 Million). The largest proposal is for $9 million and 15 positions in 2017‑18 (declining to $1.2 million and 7 positions in 2019‑20 and thereafter) to support activities in three departments:

- Forest Restoration Grants ($7 Million). The budget includes $5 million to support CFIP, which extends for one additional year the same level of resources that CFIP has received for the past two years. The Governor also proposes extending current SWRCB grants for another two years at their current funding level of $2 million annually.

- State Operations ($2 Million). The budget includes about $1 million ($472,000 ongoing) for CNRA and CalFire to support development of an online timber harvest permitting system, $549,000 to convert four limited‑term positions at SWRCB to permanent status, $300,000 annually for CNRA to continue existing pilot projects for an additional two years, and $149,000 for one additional support position at CNRA to assist in the development of ecological metrics and monitoring protocols.

Restore Nursery Operations ($4.9 Million). The budget includes $4.9 million ($2.1 million ongoing) for CalFire to resume state nursery operations at L.A. Moran Reforestation Center (LAMRC), which has been used in the past to support the reforestation of public and private forest lands, especially those that have been damaged by fire, flood, drought, insects, and disease. The administration proposes resuming these activities to encourage landowners to participate in reforestation activities as soon as possible following natural disasters in order to begin recovery of forest health and reduce soil erosion and water pollution. The center is expected to provide 300,000 seedlings annually.

Historically, the state operated three nurseries, which provided 600,000 to 800,000 seedlings annually that were native to the state’s approximately 80 “seed zones” or habitat types. The last of these nurseries closed in 2011 due to budget constraints during the recession. The department indicates that federal and private nurseries were unable to fully backfill the loss of state seedlings, and that there are currently no private nurseries operating within California that cover all of California’s seed zones. Additionally, according to the department, private nurseries typically only grow seedlings on request, which can result in significant delays in acquiring seedlings after a natural disaster. Conversely, state nurseries keep seedlings stocked so they are immediately available. Seedling delays can allow unwanted vegetation to take over and increase erosion. The department anticipates a significant demand for seedlings over the next few years due to tree mortality and the associated increased fire risk.

Monitoring Exemptions and Emergency Notice Provisions ($1.4 Million). The budget includes $1.4 million ($1.2 ongoing) from TRFRF for CalFire to implement the following three pieces of recent legislation:

- Chapter 583 of 2016 (AB 1958, Wood) exempts the removal of non‑oak trees for the purpose of restoring or conserving oak woodlands from being subject to a THP. The law also requires CalFire to evaluate and report on the effects of this exemption.

- Chapter 563 of 2016 (AB 2029, Dahle) requires the department to evaluate the Forest Fire Prevention Pilot, which provides a THP exemption for specific tree removal activities that could reduce fire risk. The department is required to monitor all projects submitted under the pilot.

- Chapter 476 of 2016 (SB 122, Jackson) requires CalFire to prepare a record of proceedings—an official record of all project application materials, reports, and related documents—concurrently with a THP or other type of harvest permit at the request of the applicant. (These costs are reimbursed by the applicant.)

LAO Assessment

Budget Requests Reasonable. We have no specific concerns with the activities proposed by the administration. Much of the proposal is the continuation of forest health activities that have been funded for the past couple of years. Additionally, these activities are in line with those identified in TRFRP statute to promote forest health, and requested funding levels appear to be in line with associated workload.