LAO Contact

February 23, 2017

The 2017-18 Budget

Alternatives to the Governor's Proposition 2 Proposals

Summary

Proposition 2 (2014) requires the state to make: (1) minimum annual payments toward certain eligible debts and (2) deposits into the state’s rainy day fund. As part of this year’s budget proposal, the Governor has outlined his priorities for required debt payments, allocating the majority to repay special fund loans and Proposition 98 settle up. The Governor also proposes the state end 2017‑18 with $9.4 billion in total budget reserves, including $7.9 billion in the state’s rainy day fund.

This publication outlines alternatives to the Governor’s proposals that could free up General Fund resources. Of these options, there is the strongest argument for counting the repayment of weight fee loans toward Proposition 2 debt payment requirements. (These are loans to the General Fund from a fund receiving transportation weight fee revenues that—upon repayment—are used for transportation bond debt service.) This option would free up $380 million in General Fund resources in 2017‑18. The Legislature could implement this option, or others, either by: (1) reducing other currently proposed repayments or (2) funding possible additional debt payments if requirements are higher in May. The Legislature could use these additional funds to build more reserves, address the Governor’s estimated budget problem, or adopt other legislative priorities.

Introduction

Governor Proposes Total Reserves of $9.4 Billion. The 2017‑18 Governor’s Budget proposes that the state end 2017‑18 with $9.4 billion in total reserves. As shown in Figure 1, this would increase total reserves from their assumed level of $8.5 billion in the 2016‑17 budget package. This total reserve balance would consist of: (1) $1.6 billion in the state’s discretionary reserve, and (2) $7.9 billion in the state’s mandatory reserve, which is governed by the terms of Proposition 2 (2014).

Figure 1

Governor Proposes Total Reserves of $9.4 Billion

(In Billions)

|

Reserves Assumed in 2016‑17 Budget |

$8.5 |

|

BSA deposit for 2017‑18 |

1.2 |

|

2017‑18 proposed decrease in SFEUa |

‑0.2 |

|

Total Reserve Balances |

$9.4 |

|

aDifference between assumed SFEU balance in the 2016‑17 budget package ($1.8 billion) and proposed SFEU balance in the 2017‑18 Governor’s Budget ($1.6 billion). BSA = Budget Stabilization Account and SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties. |

|

Under Governor’s Revenue Estimates, State Faces Budget Problem of $1.6 Billion. In preparing the 2017‑18 budget, the administration concluded that the state’s fiscal condition had worsened and, absent new budget actions, the state would have a budget deficit of $1.6 billion at the end of 2017‑18. The administration proposes $3.2 billion in budget actions to eliminate its projected $1.6 billion deficit and leave a balance in the 2017‑18 year‑end discretionary reserve of $1.6 billion.

Proposition 2 Requires Minimum Debt Payments and Reserve Deposits Each Year. Passed by voters in 2014, Proposition 2 amended the State Constitution to require the state to make minimum annual debt payments and budget reserve deposits. As part of this year’s budget proposal, the Governor has outlined his priorities for these required debt payments and his proposed level of total reserves, including those required under Proposition 2. This publication outlines alternatives for Proposition 2 debt payments and reserve balances that could free up General Fund resources. The Legislature could use these additional funds to build more reserves, address the Governor’s estimated budget problem, or adopt other legislative priorities.

Debt Payments

Proposition 2 Debt Payment Requirements

State Constitution Requires Minimum Debt Payments Each Year. Proposition 2 requires the state to spend a minimum amount each year to pay down specified debts. These minimum payments are required through 2029‑30. Thereafter, debt payments become optional, but amounts not spent on debt must be deposited into the rainy day reserve. Unlike reserve requirements, which the Governor and Legislature may reduce during a budget emergency, the state may not reduce the constitutionally required debt payments for any reason. We note that—as described in the box below—the annual state budget pays down billions of dollars of other liabilities outside of Proposition 2 requirements.

Proposition 2 One Part of State’s Debt Approach

Other Liabilities Paid Outside of Proposition 2 (2014) Requirements. Beyond Proposition 2’s requirements, the annual budget pays down several billion dollars of liabilities each year. These include debt service on bonds, budgetary liabilities—such as K‑14 mandate reimbursements—and pension unfunded liabilities. For example, in addition to $1.3 billion in Proposition 2 debt payments, the 2016‑17 Budget Act allocated about $3 billion in General Fund resources to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System to pay down the unfunded liability for state employee pension benefits. The 2016‑17 budget plan also included about $5 billion for debt service on general obligation bonds.

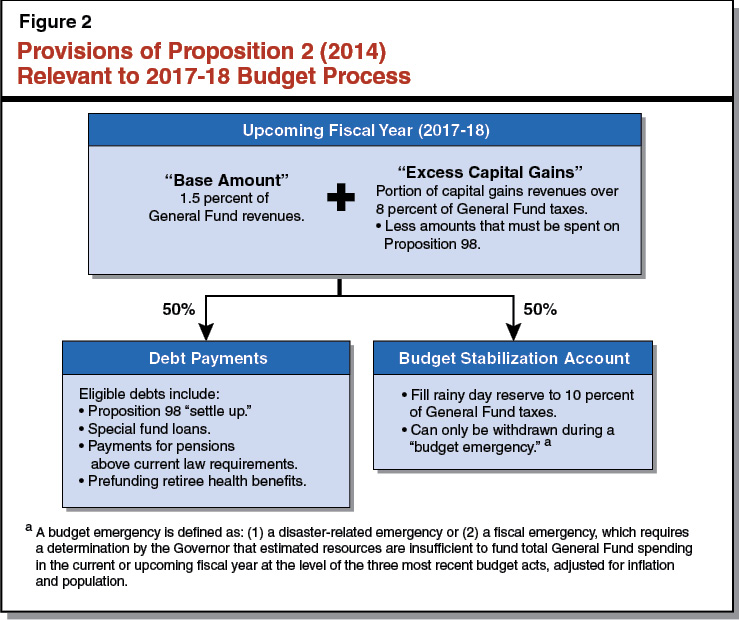

Minimum Debt Payment Requirements Set by Proposition 2 Estimates. Figure 2 illustrates the steps in determining the amount of required debt payments under Proposition 2. First, the state must set aside 1.5 percent of General Fund revenues (we refer to this as the “base amount”). Second, the state must set aside a portion of capital gains revenues that exceed a specified threshold (we refer to this as “excess capital gains”). The state combines these two amounts and then allocates half of the total to pay down eligible debts and the other half to increase the level of the rainy day reserve.

Debt Payment Requirements Will Change in May. While the base amount is relatively steady, the excess capital gains portion of the Proposition 2 requirements can change significantly. In particular, these changes can occur with changes in estimated revenues, particularly those associated with capital gains. In our January 2017 Overview of the Governor’s Budget, we noted that the administration’s estimate of 2017‑18 revenues associated with the personal income tax seemed too low. In particular, the administration’s estimates of revenues from capital gains in 2017‑18 seem inconsistent with their own economic forecasts. As a result, when the state has more information about revenue collections at the time of the May Revision, it is possible that the state could have more revenue than the administration now projects. If higher revenue estimates include increased revenues from capital gains, the state would most likely have higher debt payment requirements under Proposition 2.

Debts Eligible for Proposition 2 Funds

As shown in Figure 3, there are three types of debts eligible for payments under Proposition 2. These include certain budgetary liabilities (amounts the state owes schools and amounts the state’s General Fund owes other state funds), unfunded liabilities for pensions, and prefunding for retiree health benefits. Proposition 2 also made eligible reimbursements for pre‑2004 mandate claims from cities, counties, and special districts, but the 2014‑15 budget paid off these outstanding claims. We describe each of the remaining eligible liabilities in greater detail below. In particular, we highlight cases where our estimate of potentially eligible debts differs from the administration.

Figure 3

Liabilities Potentially Eligible for Proposition 2 Debt Payment Funds

(In Billions)

|

Amount |

|

|

Budgetary Liabilities |

|

|

Special fund loans to the General Funda |

$3.5 |

|

Proposition 98 settle up |

1.0 |

|

Unfunded Retirement Liabilities—Pensions |

|

|

School and community college employeesb |

$89.1 |

|

State and CSU employees |

49.6 |

|

UC employees |

15.1 |

|

Judges |

3.3 |

|

CalPERS quarterly payment deferral |

0.6 |

|

Unfunded Retirement Liabilities—Retiree Health |

|

|

State and CSU employees |

$76.7 |

|

UC employees |

21.1 |

|

aAmount listed differs from administration’s display for two reasons. First, we include certain transportation loans that the administration lists separately ($706 million). Second, we list transportation loans from weight fees that the administration does not include in its list of eligible debts ($1.4 billion). bThis estimate does not reflect the CalSTRS board’s recent decisions to change the investment return and other assumptions. This estimate includes the total unfunded liabilities for schools and community college employees administered by CalSTRS ($72.6 billion) and CalPERS ($16.5 billion), the latter of which is not included in the administration’s display of Proposition 2 eligible debts. The CalSTRS total includes amounts assigned to the state, districts, and unassigned. |

|

Special Fund Loans Include Weight Fee Loans. As one of many actions the state took in the 2000s to address its budget problems, the state loaned amounts to the General Fund from other state accounts known as special funds. Any such loans outstanding as of January 1, 2014 are debts eligible for payment under Proposition 2. Our display of special fund loans differs somewhat from the administration’s display. In particular, unlike the administration, we include “weight fee loans” as eligible. These are loans to the General Fund from a fund receiving transportation weight fee revenues that—upon repayment—are used for transportation bond debt service. The total amount of outstanding weight fee loans, before this year’s payment, stands at $1.4 billion. Including weight fee loans, the state currently has $3.5 billion in outstanding special fund loans.

Proposition 98 Settle Up Similar to Administration’s Display. Proposition 98 establishes a constitutional minimum funding guarantee for schools and community colleges. Settle up occurs when the minimum guarantee turns out to be larger than the amount that was initially included in the budget. Settle up existing as of July 1, 2014 is eligible to be paid from Proposition 2. Our estimate of $1 billion in total outstanding settle up is consistent with the administration’s estimate.

Pension Liabilities for School and Community College Employees Includes “Classified” Employees. Payments toward unfunded liabilities of “state‑level pension plans” are eligible to count under Proposition 2 debt payment requirements. In Figure 3, we have listed unfunded liabilities of pension benefits related to school and community college employees ($89.1 billion), state and California State University (CSU) employees ($49.6 billion), University of California (UC) employees ($15.1 billion), and judges ($3.3 billion). Our display of eligible pension debts for school and community college employees differs from that of the administration. This category includes both the unfunded liability for the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS), the pension program for teachers and administrators (which the administration includes in its display) and the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) program for school and community college classified employees, such as food service workers (which the administration does not include). As a result, our estimate of these eligible unfunded liability costs are $16.5 billion higher than that of the administration.

Payments to Prefund Retiree Health Benefits. Until recently, like most governments in the United States, California did not fund health and dental benefits for its retirees during their working careers in state government. This has resulted in large unfunded liabilities for those benefits. Proposition 2 permits the state to use its debt payment funds to prefund these benefits. Prefunding involves investing employee and employer contributions and using the resulting investment returns to partially fund future costs. Prefunding these benefits costs taxpayers much less over the long term than the expensive “pay‑as‑you‑go” approach (where later generations pay for benefits of past public employees). Figure 3 displays the unfunded liability for retiree health benefits associated with the state and CSU employees ($76.7 billion) and UC employees ($21.1 billion). The administration’s display of eligible retiree health benefits for state and CSU employees is based on an older actuarial valuation and therefore our figures differ slightly.

Payments for Retirement Liabilities and Retiree Health Must Be in Excess of Current Base Amounts. Proposition 2 requires payments for retirement and retiree health liabilities to be “in excess” of “current base amounts.” Under one interpretation, “current base amounts” means those required under law or agreements at some point in 2014 when the Legislature proposed and voters then passed Proposition 2. In other words, the measure would aim to accelerate payments for retirement liabilities above what they would have been under law or policies as of 2014, rather than replacing future payments already planned at that time.

Governor’s Proposal for Debt Payments

Under the Governor’s current revenue estimates, total debt payment requirements under Proposition 2 would be $1.2 billion in 2017‑18. Figure 4 shows how the administration proposes to allocate these requirements.

Figure 4

Administration’s Proposition 2 Debt Proposal for 2017‑18

(In Millions)

|

Special fund loans to the General Funda |

$487 |

|

Proposition 98 settle up |

400 |

|

State and CSU employees retiree health |

100 |

|

University of California pensions |

169 |

|

Total |

$1,156 |

|

aIncludes $8 million in interest on those loans. Also includes $235 million in repayments to the Transportation Congestion Relief Fund, which the administration displays separately. |

|

Administration’s Proposal Focuses on Special Fund Loans and Settle Up Payments. The administration’s proposal focuses on special fund loan repayments and settle up payments. In 2017‑18, it uses $487 million of the required $1.2 billion to repay special fund loans. As shown in Figure 5, the largest of these repayments are $235 million for the Transportation Congestion Relief Fund, $100 million for the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, and $90 million for the Immediate and Critical Needs Account. The special fund loan repayments include $8 million in 2017‑18 interest on those payments. The Governor’s proposal also includes a $400 million payment that would reduce the total settle up owed to schools and community colleges to $626 million.

Figure 5

Proposed Special Fund Loan Repayments in 2017‑18

(In Millions)

|

Fund Name |

Amount |

|

Transportation Congestion Relief Fund |

$235 |

|

Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund |

100 |

|

Immediate and Critical Needs Account |

90 |

|

Hospital Building Fund |

15 |

|

False Claims Act Fund |

13 |

|

Contingent Fund of the Medical Board of California |

9 |

|

Behavioral Science Fund |

6 |

|

Firearms Safety and Enforcement Special Fund |

5 |

|

Registry of Charitable Trust |

3 |

|

Environmental Water Fund |

2 |

|

California Water Fund |

1 |

|

Subtotals, Proposed Repayments (Principal) |

($479) |

|

Interest on loans projected for repayment |

$8 |

|

Total Proposed Special Fund Repayments |

$487 |

Administration Also Counts Prefunding of Retiree Health Benefits. The state has begun implementing its plan to address retiree health benefit liabilities through (1) employer (state) and employee contributions to prefund these benefits and (2) a reduction in the benefits earned by future employees. Through the collective bargaining process, the state has implemented its plan for most state employees. The administration’s proposal for Proposition 2 debt payments counts all of the state’s current costs of prefunding retiree health benefits toward Proposition 2. The administration’s initial estimate of these costs is $92 million in 2017‑18 and the Governor proposes setting aside $100 million in Proposition 2 requirements for this purpose (as shown in Figure 4).

Options for Proposition 2 Debt Payment Requirements

In this section, we outline two options for using Proposition 2 debt payment requirements that could free up General Fund resources. They are:

- Count Repayment of Weight Fee Loans Toward Proposition 2. The administration estimates that the General Fund must repay $380 million in loans associated with weight fee revenues in 2017‑18. The administration does not count this repayment toward Proposition 2 debt payment requirements. As we noted in our March 2015 report, The 2015‑16 Budget: The Governor’s Proposition 2 Proposal, we think there is a strong case that these loans can be counted. Counting weight fee loans toward Proposition 2 could thereby free up $380 million in General Fund resources.

- Count Higher Employer Contributions for CalPERS and CalSTRS Toward Proposition 2. The CalPERS and CalSTRS boards recently changed their investment return and other assumptions. These changes result in annual increases in the state’s contribution rates, and therefore pension unfunded liability payments, beginning in 2017‑18. These contributions represent an increase above the rates projected at the time Proposition 2 was proposed and passed. If these changes represent an increase over “current base amounts” as defined by Proposition 2, there is an argument that part of the increase is eligible to count toward Proposition 2 debt payment requirements. Doing so could free up as much as a few hundred million dollars in General Fund resources in 2017‑18.

Options Could Fulfill Additional Requirements After May Revision. The Legislature could implement either of the above options by either: (1) reducing other currently proposed repayments, or (2) funding additional Proposition 2 debt payment requirements in May if revenue estimates, and therefore debt requirements, are higher.

LAO Comments

We have outlined two alternatives for using Proposition 2 debt payment requirements. We are not making any specific recommendations on either of these options. However, the Legislature could implement either or both of them and free up hundreds of millions of dollars in General Fund resources in 2017‑18. The Legislature could use these additional funds to build more reserves, address the Governor’s estimated budget problem, or address other legislative priorities. Below, we describe some of the trade‑offs associated with implementing these alternatives.

Strong Argument for Counting Weight Fee Loans Toward Proposition 2 Requirements. Of the alternatives for debt payments, the option to redirect some of these requirements toward weight fee loans seems to have the strongest basis. This option is consistent with the administration’s treatment of other loans under Proposition 2. It also represents a temporary use of Proposition 2 resources. That is, within a few years these loans could be fully paid off—in fact, potentially faster than now required if Proposition 2 funds are used. This would leave room for the Legislature to address other debts with Proposition 2 resources in the future.

Counting Increased CalPERS and CalSTRS Contribution Costs Problematic. As we noted earlier, the state arguably could count some higher state costs associated with increased contributions for CalPERS and CalSTRS toward Proposition 2. This option may be allowable under one interpretation of Proposition 2, but there is legal uncertainty about this interpretation. Moreover, these additional costs will increase annually under current projections. Currently, for both pension systems, these increased General Fund costs may grow from as much as a few hundred million dollars in 2017‑18 to over $2 billion in 2021‑22. If the state continued a practice of counting some of these payments toward Proposition 2, they could eventually consume the bulk of the required debt payments.

Counting These Debts Toward Proposition 2 Means Fewer Resources for Other Debts. If 2017‑18 Proposition 2 debt payment requirements are close to current projections in May, the Legislature could implement one or both of the alternative debt repayment options we discussed by reducing other currently proposed payments. This would achieve net General Fund savings, but beneficiaries of the currently proposed debt payments could view this change unfavorably. For example, if the Legislature chose to reduce special fund loan repayments, special fund fee payers may not see near‑term benefits resulting from proposed loan repayments (if the repayments were used to reduce fees or increase services). Alternatively, if there are additional debt payment requirements in May due to higher revenue projections, the Legislature could direct those additional payments toward one or both of the debt repayment alternatives.

Reserves

Background

State Has Two Budget Reserves. The state has two budget reserves: the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU) and the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA). The SFEU is the state’s discretionary budget reserve—that is, the Legislature at any time can appropriate funds in the SFEU for any purpose by majority vote. Unlike the SFEU, use of funds in the state’s rainy day fund—the BSA—is more restricted. The State Constitution has specific rules regarding how and when the state must make deposits into or may make withdrawals from the BSA. Similar to the minimum debt payment requirements, these rules are detailed earlier in Figure 2.

Components of $9.4 Billion in Total Reserves. Under the administration’s current estimate of revenues, total reserve balances would reach $9.4 billion by the end of 2017‑18. Figure 6 shows the components of this reserve balance, including the composition of the BSA. In particular, the BSA reserve includes $1.6 billion deposited in 2014‑15, before the enactment of Proposition 2. The remaining BSA deposits, and estimated deposit for 2017‑18, will have been deposited pursuant to the rules of Proposition 2. (The $2 billion optional BSA deposit in 2016‑17 included budget bill language implying that these funds are also deposited pursuant to these rules.) Under Proposition 2, the state must put money into the BSA until its total reaches a maximum amount of 10 percent of General Fund taxes (currently, about $12.5 billion under the administration’s revenue estimates).

Figure 6

Components of Total $9.4 Billion in Reserves

(In Millions)

|

Budget Stabilization Account |

|

|

2014‑15 pre‑Proposition 2 BSA deposit |

$1,606 |

|

2015‑16 revised BSA deposit |

1,814 |

|

2016‑17 required BSA deposit |

1,294 |

|

2016‑17 additional transfer to BSA |

2,000 |

|

2017‑18 estimated BSA deposit |

1,156 |

|

Total, Proposed BSA Balance |

$7,869 |

|

Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties |

|

|

Total, Proposed SFEU Balance |

$1,554 |

|

Total Reserve Balances |

$9,424 |

|

BSA = Budget Stabilization Account and SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertanties. |

|

Building Reserves Allows State to Sustain Future Spending Levels. Both of the state’s budget reserves help insulate the budget from situations where revenues underperform budget assumptions. If the state faces a deficit, these reserves can delay—or even prevent—the state from making difficult choices (including spending cuts or tax increases) to address a potential budget problem. As such, building reserves during times of economic expansion allows the state to sustain future spending levels during times of economic distress. As described in the box below, the structure of Proposition 2 directly aims to protect the state from these ups and downs in revenue collections.

How Proposition 2 (2014) Mitigates State Revenue Volatility

Proposition 2 aims to protect the budget from periods when revenues underperform expectations. In particular, it sets aside monies from one of the most volatile components of state revenues—capital gains—by directing above average growth in this source into budget reserves and debt payments. It therefore mitigates revenue volatility by: (1) taking revenues “off the table” in good economic times and (2) building budget reserves that can be used during bad economic times to augment declining revenues.

State Only Has Access to Proposition 2 BSA Funds During a Budget Emergency. Under Proposition 2, the Legislature can only reduce the BSA deposit, or make a withdrawal from the BSA reserve, in the case of a budget emergency. A budget emergency can only occur upon declaration by the Governor. The Governor may call a budget emergency in two cases: (1) a “fiscal emergency,” which occurs if estimated resources in the current or upcoming fiscal year are insufficient to keep spending at the level of the prior three budgets adjusted for inflation and population or (2) a “disaster‑related emergency,” which is in response to a disaster such as the declared emergency in response to the situation at the Oroville Dam. In the presence of a fiscal emergency, the Legislature may appropriate funds from the BSA with a majority vote. However, it may only withdraw the amount needed to maintain General Fund spending at the highest level of the past three enacted budget acts, but no more than 50 percent of the BSA balance in the emergency’s first fiscal year. In the case of a disaster‑related emergency, the Legislature may use the amount of funds required to address the emergency. Proposition 2 does not specify a deadline for the Governor to call a budget emergency.

Can the Legislature Use Funds From the BSA to Address the Budget Shortfall?

Given the current budget problem identified by the Governor, some have asked whether the BSA could be accessed under the fiscal emergency provisions of Proposition 2. In this section, we address this question.

Fiscal Emergency Seems Available Under Governor’s Revenue Estimates. Unlike other calculations, Proposition 2 does not require the administration to produce a fiscal emergency calculation as part of the budget process. In fact, there are some uncertainties about how such a calculation would be administered. Figure 7 displays one version of such a calculation using the administration’s estimates of revenues for 2016‑17 and 2017‑18. As shown in the figure, a fiscal emergency seems available in the 2017‑18 calculation. Specifically, resources available in 2017‑18 are about $2 billion lower than the adjusted budget for 2016‑17. That is in large part the result of the Governor’s projections of slow growth in revenues between 2016‑17 and 2017‑18.

Figure 7

Fiscal Emergency in 2017‑18 Seems Available Under Administration’s Estimates

(In Millions)

|

2016‑17 Calculation |

2014‑15 |

2015‑16 |

2016‑17 |

|

Adjusted budget for fiscal yeara |

$113,845 |

$118,724 |

$122,468 |

|

Resources available for 2016‑17b |

122,809 |

122,809 |

122,809 |

|

Adjusted budget greater than resources available? |

No |

No |

No |

|

Amount of budget emergency |

|||

|

2017‑18 Calculation |

2014‑15 |

2015‑16 |

2016‑17 |

|

Adjusted budget for fiscal yeara |

$117,380 |

$122,410 |

$126,271 |

|

Resources available for 2017‑18b |

124,075 |

124,075 |

124,075 |

|

Adjusted budget greater than resources available? |

No |

No |

Yes |

|

Amount of budget emergency |

2,196 |

||

|

aEquals enacted budget total expenditures for fiscal year grown for change in inflation (as measured by the California Consumer Price Index) and population. bEquals prior‑year balance plus revenues and transfers minus encumbrances. |

|||

Governor Does Not Propose Using BSA to Cover Budget Problem. In theory, if the Governor were to call a fiscal emergency, the Legislature could appropriate about $2 billion of BSA funds with a majority vote of both houses. However, the Governor has not called a fiscal emergency and, as such, the Legislature is precluded from using this option. (We would note the Governor could call a budget emergency—either a fiscal emergency or a disaster‑related emergency—later in the budget process.)

Strong Argument Legislature Has Access to Pre‑Proposition 2 BSA Balance. There is a strong argument that the $1.6 billion deposited in the BSA in 2014‑15 is not governed by the Proposition 2 rules. This means the Legislature arguably has greater control over these funds than it has over other funds in the BSA and potentially could access these funds even without the declaration of a budget emergency by the Governor.

LAO Comments

We have outlined the reasons the Legislature cannot access the BSA in response to a fiscal emergency to address the Governor’s estimated budget problem. We also pointed out that the Legislature arguably has some legal authority to use a portion of the BSA balance without a declaration of a budget emergency by the Governor.

Recommend Legislature Not Use BSA Funds to Cover a Budget Shortfall. At this time, we do not recommend the Legislature use BSA funds to cover a shortfall in response to fiscal conditions even if it has the legal authority to do so. As we noted in The 2017‑18: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, the Legislature may want to set its target for state reserves at—or preferably above—the level the Governor now proposes. Withdrawing funds from the BSA to address a budget shortfall now would hamper the state’s ability to build reserves, which will be needed in the face of the next recession.