March 9, 2017

The 2017-18 Budget

Analysis of the Medi‑Cal Budget

- Overview

- Background

- Governor’s Budget Caseload Projections

- Continued Uncertainty in Projecting ACA Optional Expansion Caseload Growth

- Proposed Use of Proposition 56 Revenues

- Proposed Transition of New Qualified Immigrants to Covered California

- CHIP Funding

- Proposed Abolition and Transfer of MRMIF

Executive Summary

The Governor’s budget proposes $19.1 billion General Fund for Medi‑Cal. This is a decrease of $430 million—or 2 percent—below the estimated 2016‑17 General Fund spending level. Total Medi‑Cal spending (all funds) is proposed to increase by $2.6 billion between 2016‑17 and 2017‑18—from $100 billion to $102.6 billion. This increase in total spending is primarily due to higher special fund spending.

Current‑Year Spending Reflects Two Major Upward Adjustments. Estimated 2016‑17 General Fund spending in Medi‑Cal has been adjusted upward by $1.8 billion. This adjustment reflects two major factors: (1) a miscalculation of the costs and savings associated with the Coordinated Care Initiative and (2) a one‑time General Fund cost increase due to the payment of prescription drug rebates owed to the federal government that, while budgeted in 2015‑16, was not paid in that fiscal year and thus remained owing and was paid in 2016‑17.

Budget‑Year Spending Reflects Several Factors. Year‑over‑year changes in total Medi‑Cal spending and in the program’s funding mix reflect several factors, including: (1) nearly $700 million in higher state costs for the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) optional expansion population; (2) around $535 million in higher projected General Fund spending based on the administration’s assumption of less federal Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) funding in 2017‑18; and (3) significant growth in state special fund spending, including new Proposition 56 tobacco excise tax revenues dedicated to Medi‑Cal.

Governor’s Caseload Projections Appear Reasonable. The Governor’s budget estimates Medi‑Cal caseload of 14 million for 2016‑17, a 5 percent increase over the caseload estimate of 13.4 million for 2015‑16. The budget projects a Medi‑Cal caseload of 14.3 million for 2017‑18, an increase of 2 percent over the 2016‑17 caseload. We find the administration’s Medi‑Cal caseload estimates to be reasonable, though subject to some uncertainty particularly regarding the ACA optional expansion caseload. If this component of the Medi‑Cal caseload grows at a higher or lower rate than the administration currently projects, state spending could be higher or lower in 2016‑17 and/or 2017‑18 by tens of millions of dollars.

Proposed Transition of New Qualified Immigrants (NQIs) to Covered California Raises Issues for Legislative Consideration. Legislation enacted in 2013 requires NQIs eligible for full‑scope Medi‑Cal as a result of the ACA optional expansion to transition from the state‑only Medi‑Cal program into subsidized coverage through the state’s Health Benefit Exchange—Covered California—with a Medi‑Cal “wrap.” (This transition has been delayed to January 1, 2018.) The Governor’s budget proposes to shift additional NQIs (that is, NQIs in addition to those whose eligibility for state‑only Medi‑Cal was triggered by the ACA optional expansion) into Covered California with a Medi‑Cal wrap starting January 1, 2018. The administration suggests the budget proposal will protect these additional NQIs from potential tax penalties under the ACA. We find that the Governor’s budget proposal could generate General Fund savings from the additional federal funding for additional NQIs, and is consistent with the concept driving the 2013 legislation.

We provide the Legislature with several issues to consider based on what action it takes on the proposal. If the Legislature approves the proposal, there are implementation challenges to be addressed. In this case, the Legislature should consider requiring (1) regular reporting by the administration on progress toward implementing the transition and (2) the Department of Health Care Services to provide guidance on how NQIs would be reenrolled in health insurance coverage should Covered California become inoperative. If the Legislature rejects the proposal, the Legislature might also consider whether or not to continue the planned transition under the 2013 legislation.

Governor’s Federal CHIP Funding Assumption Reasonable, Though Uncertain. The Governor’s budget assumes CHIP funding is reauthorized in federal fiscal year 2017‑18, but at a 65 percent federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) in California instead of the 88 percent FMAP authorized by the ACA. We find the Governor’s approach to budgeting CHIP funding is reasonable given the uncertainty around congressional action. Across the range of potential actions Congress may take on CHIP funding, the Governor’s budget assumes a middle‑of‑the‑road scenario.

Take No Issue With Governor’s Proposed Abolition of the Major Risk Medical Insurance Fund (MRMIF). The Governor’s budget proposes to abolish MRMIF and transfer its fund balance and any ongoing revenue from the Managed Care Administrative Fines and Penalties Fund into a newly created Health Care Services Plans and Penalties Fund, which will fund ongoing Medi‑Cal services. We find the Governor’s budget proposal on MRMIF to be reasonable, particularly given the high remaining MRMIF balance that is likely to go substantially unused for many years.

Overview

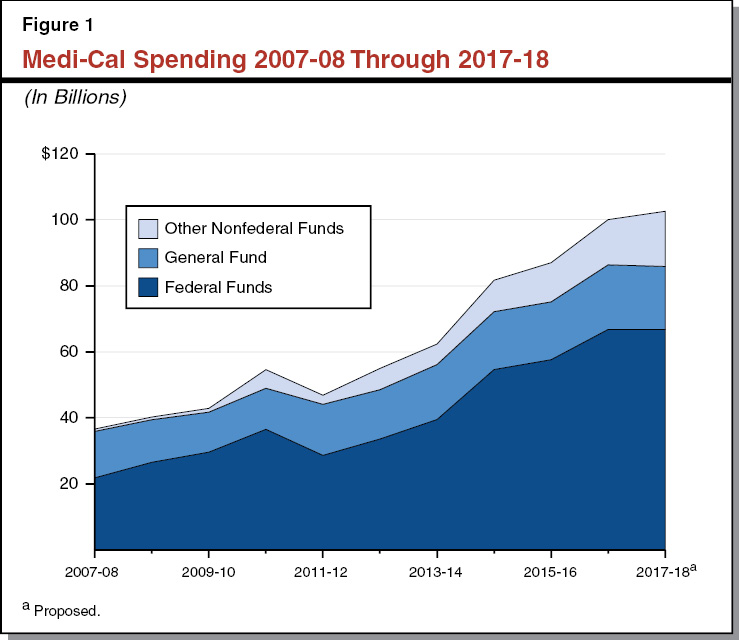

The Governor’s budget proposes $19.1 billion General Fund for Medi‑Cal. This is a decrease of $430 million—or 2 percent—below the estimated 2016‑17 General Fund spending level. While proposed General Fund Medi‑Cal spending is lower in 2017‑18 than 2016‑17, other nonfederal Medi‑Cal spending (which includes funding from state special funds as well as some local Medi‑Cal funding) is over $3 billion—or 22 percent—higher in 2017‑18 than 2016‑17. Proposed federal Medi‑Cal spending of about $67 billion is essentially flat between the two fiscal years. Total Medi‑Cal spending is proposed to increase by $2.6 billion between 2016‑17 and 2017‑18—from $100 billion to $102.6 billion. Figure 1 shows the increase in Medi‑Cal spending from 2007‑08 through 2017‑18 by funding source. As indicated by Figure 1, federal funds and state and local funding sources other than the General Fund account for the vast majority of long‑term expenditure growth in Medi‑Cal.

Current‑Year Adjustments. Estimated 2016‑17 General Fund spending in Medi‑Cal reflects two major upward adjustments that are one‑time in nature:

- A net increase in General Fund costs—totaling $1.4 billion—due to a miscalculation of the costs and savings associated with the Coordinated Care Initiative (CCI). (We address the Governor’s CCI‑related actions and budget proposals in a separate report, The 2017‑18 Budget: The Coordinated Care Initiative: A Critical Juncture.)

- A one‑time General Fund cost increase of nearly $500 million due to the payment of funds owed to the federal government that was not budgeted in the 2016‑17 Budget Act. (This payment was budgeted in 2015‑16 but was not paid in that year as intended.) These funds related to prescription drug rebates for individuals who are newly eligible for Medi‑Cal under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) optional expansion.

Budget‑Year Changes. Year‑over‑year changes in total Medi‑Cal spending and in the program’s funding mix reflect the following major factors:

- $700 million in higher state costs for the ACA optional expansion population. These higher state costs are primarily a result of the state’s share of costs for this population increasing in accordance with federal law from an effective 2.5 percent to an effective 5.5 percent between 2016‑17 and 2017‑18. (While changes in the state’s cost share for this population are on a calendar‑year basis under the ACA, we have translated the costs here to a state fiscal‑year basis.) We note that a sizable portion of these increased state costs are proposed to be paid with Proposition 56 revenues.

- Around $535 million in higher projected General Fund spending based on the administration’s assumption that less federal Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) funding will be appropriated in 2017‑18 compared to 2016‑17.

- Nearly $140 million in General Fund spending to support implementation of the Drug Medi‑Cal Organized Delivery System Waiver, a joint federal‑state‑county demonstration project aimed at providing a full continuum of substance use disorder services—from residential treatment to outpatient services—to Medi‑Cal enrollees in the 16 participating counties.

- Significant growth in state special fund spending in Medi‑Cal in 2017‑18 compared to 2016‑17. The three major sources of higher special fund spending in Medi‑Cal in 2017‑18 are (1) Proposition 56 tobacco excise tax revenues dedicated to Medi‑Cal, (2) managed care organization tax revenues, and (3) hospital quality assurance fee revenues. Together, these three special fund sources account for about $1.9 billion of the $2.6 billion increase in total Medi‑Cal spending between 2016‑17 and 2017‑18.

We would note that some budget solutions proposed by the administration were not incorporated into the bottom‑line spending estimates of the Governor’s Medi‑Cal budget. These include proposals to delay shifting services for California Children’s Services eligible children from fee‑for‑service (FFS) into managed care under the Whole Child Model and to delay providing palliative care services to eligible Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. These proposed delays are projected to reduce General Fund costs by $21 million in 2017‑18 below what is currently budgeted for Medi‑Cal.

We would also note that there is substantial federal uncertainty about the future of the ACA. In projecting Medi‑Cal spending in 2017‑18, the Governor’s budget generally assumes existing federal and state law. The one major exception involves CHIP. The Governor’s budget assumes that enhanced federal funding for CHIP will continue beyond the date to which Congress has appropriated funding (September 30, 2017), but at a lower federal cost share, known as the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP). This assumption increases projected state Medi‑Cal spending in 2017‑18 by a significant amount. We address the general uncertainty around the future of the ACA and the potential fiscal implications for the state in a separate report, The Uncertain Affordable Care Act Landscape: What It Means for California.

In this report, we provide an analysis of the administration’s caseload projections, including a discussion of the projected increases in ACA optional expansion caseload. We also provide an assessment of several aforementioned major factors affecting projected changes in Medi‑Cal spending in 2017‑18 and other policy changes proposed by the administration. These include the Governor’s proposed uses of Proposition 56 revenues, the proposal to shift additional New Qualified Immigrants (NQIs) to Covered California in 2017‑18, assumptions around federal CHIP funding, and the proposed abolition and transfer of the Major Risk Medical Insurance Fund (MRMIF).

Back to the TopBackground

In California, the federal‑state Medicaid program is administered by the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) as the California Medical Assistance Program (Medi‑Cal). Medi‑Cal is by far the largest state‑administered health services program in terms of annual caseload and expenditures. As a joint federal‑state program, federal funds are available to the state for the provision of health care services for most low‑income persons. Until recently, Medi‑Cal eligibility was mainly restricted to low‑income families with children, seniors and persons with disabilities (SPDs), and pregnant women. As part of the ACA, beginning January 1, 2014, the state expanded Medi‑Cal eligibility to include additional low‑income populations—primarily childless adults who did not previously qualify for the program.

Financing. The costs of the Medicaid program are generally shared between states and the federal government based on a set formula. The federal government’s contribution toward reimbursement for Medicaid expenditures is known as federal financial participation. The share of Medicaid costs paid by the federal government is known as the FMAP.

For most families and children, SPDs, and pregnant women, California generally receives a 50 percent FMAP—meaning the federal government pays one‑half of Medi‑Cal costs for these populations. However, a subset of children with higher incomes qualify for Medi‑Cal as part of the state’s CHIP. Currently, the federal government pays 88 percent of the costs for children enrolled in CHIP and the state pays 12 percent. Finally, under the ACA, the federal government paid 100 percent of the costs of providing health care services to the newly eligible Medi‑Cal population from 2014 through 2016. Beginning in 2017, the federal cost share decreased to 95 percent, phasing down to 90 percent by 2020 and thereafter.

Delivery Systems. There are two main Medi‑Cal systems for the delivery of medical services: FFS and managed care. In a FFS system, a health care provider receives an individual payment from DHCS for each medical service delivered to a beneficiary. Beneficiaries in Medi‑Cal FFS may generally obtain services from any provider who has agreed to accept Medi‑Cal FFS payments. In managed care, DHCS contracts with managed care plans, also known as health maintenance organizations, to provide health care coverage for Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. Managed care enrollees may obtain services from providers who accept payments from the managed care plan, also known as a plan’s “provider network.” The plans are reimbursed on a “capitated” basis with a predetermined amount per person, per month regardless of the number of services an individual receives. Medi‑Cal managed care plans provide enrollees with most Medi‑Cal covered health care services—including hospital, physician, and pharmacy services—and are responsible for ensuring enrollees are able to access covered health services in a timely manner. (In some counties, Medi‑Cal managed care plans also provide long‑term services and supports, including institutional care in skilled nursing facilities, and home‑ and community‑based services.) Managed care enrollment is mandatory for most Medi‑Cal enrollees, meaning these enrollees must access most of their Medi‑Cal benefits through the managed care delivery system. As a result, in 2017‑18 nearly 80 percent of Medi‑Cal enrollees are projected to be enrolled in managed care.

The number and type of managed care plans available vary by county, depending on the model of managed care implemented in each county. Counties can generally be grouped into four main models of managed care:

- County Organized Health System (COHS). In the 22 COHS counties, there is one county‑run managed care plan available to beneficiaries.

- Two‑Plan. In the 14 Two‑Plan counties, there are two managed care plans available to beneficiaries. One plan is run by the county and the second plan is run by a commercial health plan.

- Geographic Managed Care (GMC). In GMC counties, there are several commercial health plans available to beneficiaries. There are two GMC counties—San Diego and Sacramento.

- Regional. Finally, in the Regional model, there are two commercial health plans available to beneficiaries across 18 counties.

Imperial and San Benito Counties have managed care plans that are not run by the county, and that do not fit into one of these four models. In Imperial County, there are two commercial health plans available to beneficiaries and in San Benito, there is one commercial health plan available to beneficiaries.

Back to the TopGovernor’s Budget Caseload Projections

According to the Medi‑Cal Eligibility Data System, there were over 13.5 million people enrolled in Medi‑Cal as of June 2016. This count includes over 3.3 million enrollees—mostly childless adults—who became newly eligible for Medi‑Cal under the ACA optional expansion. A substantial number of families and children who were previously eligible—known as the ACA mandatory expansion—are also assumed to have enrolled as a result of eligibility simplification, enhanced outreach, and other provisions and effects of the ACA. The Governor’s budget assumes that following a large influx of enrollees in 2015‑16 and 2016‑17, ACA‑related caseload levels will stabilize during 2017‑18. The budget also assumes modest underlying enrollment growth within the families and children, and SPD populations.

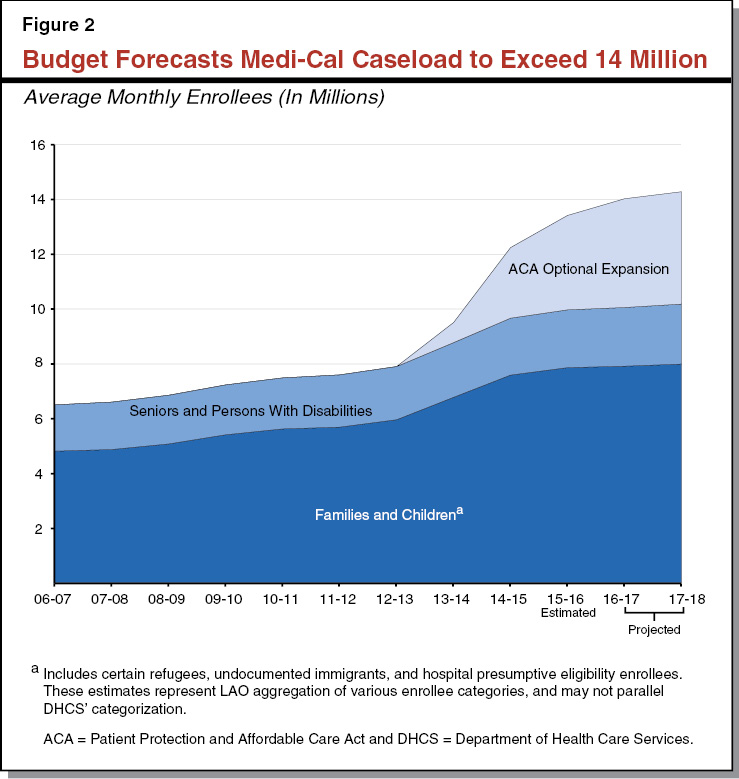

Historical Trends. Figure 2 displays over a decade of observed and estimated caseload for each major category of enrollment in Medi‑Cal, beginning with (1) historical caseload through 2014‑15, followed by (2) the administration’s revised estimate for caseload in 2015‑16, and (3) the Governor’s budget projections for 2016‑17 and 2017‑18. While SPD enrollment grew steadily at about 2 percent annually throughout the historical period, the families and children caseload grew at an average rate of about 4 percent between 2007‑08 and 2010‑11 (the onset of the Great Recession through the sluggish phase of the recovery). The further uptick in families and children in 2013‑14 reflects the shift of the Healthy Families Program to Medi‑Cal. Further growth in the families and children population after 2013‑14 largely reflects the impact of the ACA.

Caseload Projections in Governor’s Budget. The Governor’s budget assumes an average monthly Medi‑Cal caseload of 14 million for 2016‑17. This is a 5 percent increase over the revised caseload estimate of 13.4 million for 2015‑16. This significant year‑over‑year increase reflects, at least in part, continued growth related to the ACA. The budget assumes total annual Medi‑Cal caseload of 14.3 million for 2017‑18, an increase of 2 percent over the 2016‑17 caseload. (This 2 percent annual growth is in line with historical Medi‑Cal caseload growth predating the ACA.) Of the 14.3 million beneficiaries, 4.1 million enrollees are projected to have gained eligibility through the ACA optional expansion.

Administration’s Caseload Projections Appear Reasonable. We have reviewed the administration’s caseload projections in the context of the substantial ACA‑related changes to the Medi‑Cal caseload in recent years, and we find the estimates to be reasonable. We note, however, these ACA‑related changes have made it more difficult to project caseload. We discuss, in particular, the growth in ACA optional expansion caseload in more detail in the next section. Further, if we receive additional information that causes us to change our assessment of the caseload projections in the Governor’s budget, we will provide the Legislature with an updated analysis at the time of the May Revision.

Back to the TopContinued Uncertainty in Projecting ACA Optional Expansion Caseload Growth

ACA Expanded Medicaid Eligibility to Low‑Income, Childless Adults. Before the ACA, Medi‑Cal eligibility was generally restricted to families and SPDs with incomes below 108 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). Accordingly, childless adults under age 65 were ineligible for Medi‑Cal regardless of income. The ACA expanded eligibility for Medi‑Cal to individuals under age 65 (children, parents, and childless adults) with household incomes at or below 138 percent of FPL. The population who became eligible for Medi‑Cal under the ACA is known as the ACA optional expansion population.

Administration Assumes Strong Growth in ACA Optional Expansion Caseload in 2016‑17. The administration projects that the ACA optional expansion caseload will continue to grow significantly from its 2015‑16 level, particularly in 2016‑17. Between 2015‑16 and 2016‑17, average monthly caseload for the ACA optional expansion population is projected to grow by 15 percent—from under 3.5 million to nearly 4 million. In 2017‑18, the administration projects that ACA growth will significantly taper off, increasing average monthly ACA optional expansion caseload to a little over 4 million, or a 3 percent rate of increase. This is more in line with other Medi‑Cal populations’ caseload growth trends.

State Became Responsible for a Share of ACA Optional Expansion Costs in 2017. The federal government paid 100 percent of the costs of the Medi‑Cal ACA optional expansion through calendar year 2016. Beginning in 2017, the state became responsible for a 5 percent share of the ACA optional expansion’s costs. The state’s share of ACA optional expansion costs will gradually increase on an annual basis until 2020, when the state must pay 10 percent of this population’s Medi‑Cal costs. Figure 3 summarizes the federal government’s share of Medi‑Cal costs for the ACA optional expansion by state fiscal year from 2013‑14 through 2020‑21. In 2016‑17, the state is responsible for paying 2.5 percent of the ACA optional expansion population’s Medi‑Cal costs. In 2017‑18, the state share increases to 5.5 percent.

Figure 3

Federal Share of Costs for ACA Optional Expansion Population

|

State Fiscal Year |

FMAPa |

|

2013‑14 |

100.0% |

|

2014‑15 |

100.0 |

|

2015‑16 |

100.0 |

|

2016‑17 |

97.5 |

|

2017‑18 |

94.5 |

|

2018‑19 |

93.5 |

|

2019‑20 |

91.5 |

|

2020‑21 |

90.0 |

|

aDetermines federal share of costs for covered services in state Medicaid programs. We note that the FMAP for the ACA optional expansion population is stated in the ACA statute on a calendar‑year basis. We have translated the FMAP to a state fiscal‑year basis. ACA = Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and FMAP = federal medical assistance percentage. |

|

State’s ACA Optional Expansion Costs Projected to Increase by 75 Percent in 2017‑18. The administration estimates the state’s costs for the ACA optional expansion population to be almost $900 million in 2016‑17 and to be nearly $1.6 billion in 2017‑18. The $700 million year‑over‑year change is primarily the result of the state’s share of costs for this population increasing in accordance with federal law from an effective 2.5 percent to an effective 5.5 percent between 2016‑17 and 2017‑18.

Total ACA Optional Expansion Spending Projected to Decrease in 2017‑18. While state costs for the ACA optional expansion are expected to significantly increase between 2016‑17 and 2017‑18, total spending (which includes state and federal spending) on the ACA optional expansion is projected to decline by over $1 billion over this same time period. There are a number of factors explaining this year‑over‑year decline. The most significant one involves retroactive recoupments of past‑year capitated managed care payments that Medi‑Cal made on behalf of the ACA optional expansion population. Managed care plans’ costs of providing care to ACA optional expansion adults have been lower than their previous years’ capitated payments reflect. As a result, Medi‑Cal is recouping a portion of the capitated payments that it made to managed care plans in previous years. Retroactive recoupments from managed care plans are expected to be almost $700 million higher in 2017‑18 compared to 2016‑17. Because the federal government paid 100 percent of the costs of the ACA optional expansion during the time for which managed care payments are being recouped, all of the recoupments will remit to the federal government and have the effect of reducing federal Medi‑Cal spending in 2016‑17 and even more in 2017‑18.

LAO Assessment of Governor’s ACA Optional Expansion Caseload Projections

Projecting the Growth of ACA Optional Expansion Caseload Involves Some Uncertainty. The ACA has brought significant uncertainty to projecting Medi‑Cal caseloads due in part to the ACA’s expansion of Medi‑Cal eligibility to previously ineligible populations. A factor that plays an important role in the continued growth of the ACA optional expansion caseload relates to the population in California that is eligible through the ACA optional expansion but has not enrolled in Medi‑Cal. Given the high ACA optional expansion caseload growth of recent years, a higher proportion of California’s eligible population has already enrolled. Continued growth in the ACA optional expansion will depend to a significant degree on the extent to which individuals who are eligible, but not enrolled, elect to sign up for Medi‑Cal, as well as the speed with which they do so.

As we would expect, DHCS has estimated slower annual rates of caseload growth for this population. While the number of new potential ACA optional expansion enrollees is smaller than in previous years, there remains uncertainty around whether the ACA optional expansion caseload will grow at faster or slower rates in either 2016‑17 or 2017‑18 than DHCS currently projects.

Analysis Will Be Updated at May Revision. Assumptions around the growth of the ACA optional expansion caseload have fiscal implications for the state beginning in 2016‑17 as a result of the state beginning to share in the Medi‑Cal costs of this population. As such, projected state Medi‑Cal spending on the ACA optional expansion could be higher or lower in 2016‑17 and/or 2017‑18 by tens of millions of dollars. We will provide the Legislature an updated analysis of DHCS’ ACA optional expansion caseload projections at the May Revision when additional caseload trend data arrives.

Back to the TopProposed Use of Proposition 56 Revenues

In this section, we describe the Governor’s proposed uses of revenues from Proposition 56, which raised state taxes on tobacco products, within the Medi‑Cal program. We provide a general assessment of the Governor’s proposed uses of Proposition 56 revenues, beyond just Medi‑Cal, in our report, The 2017‑18 Budget: An Overview of the Governor’s Proposition 56 Proposals.

Background

Proposition 56 Raised Tobacco Excise Taxes. Proposition 56 increased the state’s excise tax on cigarettes and other tobacco products, now including electronic cigarettes, beginning April 1, 2017. The administration projects that the new tobacco taxes will raise $368 million in 2016‑17 and $1.4 billion in 2017‑18.

Proposition 56 Directs Majority of Revenues to Medi‑Cal. Revenues from the new tobacco taxes are deposited directly into a new special fund and then distributed to state departments for use in various state programs. Among other uses, Proposition 56 directs revenues from the new taxes to state programs related to tobacco cessation, physician training, and Medi‑Cal. After directing select amounts of Proposition 56 revenues to various prescribed purposes, the measure dedicates 82 percent of remaining revenues to Medi‑Cal. The measure restricts Proposition 56 revenues from supplanting existing General Fund support for Medi‑Cal.

Governor’s Proposal

Over $1.3 Billion to Medi‑Cal to Cover Anticipated Program Spending Increases. As required by the measure, the Governor’s budget allocates the bulk of the Proposition 56 revenues raised through the end of 2017‑18 (five quarters of revenues) to Medi‑Cal. (Of the $1.3 billion in revenues, about $1.2 billion would be spent in Medi‑Cal in 2017‑18 and the remainder would be spent in 2018‑19 due to Medi‑Cal’s accounting structure.) The Governor’s budget does not propose using Proposition 56 revenues to pay for new policy changes in the Medi‑Cal program, such as higher provider rates. Instead, under the Governor’s proposal, Proposition 56 revenues would largely support anticipated spending increases due to growth in the Medi‑Cal program between 2016‑17 and 2017‑18. Absent Proposition 56 funding, either the General Fund or other allowable special fund revenues would have to be used to pay for these state Medi‑Cal spending increases. We describe the use of Proposition 56 revenues in Medi‑Cal in more detail below. Under the Governor’s proposal, the majority of Proposition 56 Medi‑Cal revenue would be spent within the managed care delivery system.

Overall State Spending in Medi‑Cal Is Higher in 2017‑18, While General Fund Spending Is Lower. While the administration does not reduce overall state funding for Medi‑Cal as a result of the Proposition 56 revenues, General Fund Medi‑Cal spending is lower in 2017‑18 than 2016‑17. This reflects that higher special fund revenues from the managed care organization tax, the hospital quality assurance fee, and other non‑Proposition 56 sources more than offset the lower General Fund Medi‑Cal spending in 2017‑18.

Administration’s Approach to Proposition 56’s Non‑Supplantation Requirement for Medi‑Cal. As previously stated, Proposition 56 does not allow Proposition 56 revenues to supplant existing General Fund spending for the Medi‑Cal program. The administration interprets “existing General Fund spending” as the amount of General Fund spending in Medi‑Cal as of the 2016‑17 Budget Act. While projected Medi‑Cal General Fund spending in 2017‑18 is lower than the revised estimate of 2016‑17 Medi‑Cal General Fund spending (due to the one‑time factors discussed earlier), it is over $1 billion higher than the General Fund appropriation for Medi‑Cal in the 2016‑17 Budget Act. Since projected 2017‑18 Medi‑Cal General Fund spending is higher than the 2016‑17 Medi‑Cal General Fund appropriation, the administration believes its proposed uses of Proposition 56 revenues in Medi‑Cal are consistent with the non‑supplantation requirement of the measure. We provide an assessment of the administration’s interpretation of Proposition 56’s non‑supplantation requirement in a separate report: The 2017‑18 Budget: An Overview of the Governor’s Proposition 56 Proposals. In that report, we contrast the Governor’s interpretation of non‑supplantation to an alternative interpretation that “existing General Fund spending” means the ongoing amount of General Fund needed to fund Medi‑Cal absent any policy changes to the program. We find it uncertain how a court would decide any legal challenge brought against the state related to Proposition 56’s non‑supplantation requirements for Medi‑Cal. Finally, we suggest that the Legislature must make its own determination on how to appropriate Proposition 56 revenues in Medi‑Cal given the measure’s non‑supplantation requirements.

Large Portion of Proposition 56 Revenues Pay for State’s Increased Share of Cost for ACA Optional Expansion. Under the Governor’s proposal, a sizable portion of Proposition 56 funding in Medi‑Cal would pay for the state’s increased share of cost for the ACA optional expansion. As previously discussed, the state’s share of costs for the ACA optional expansion increases from an effective 2.5 percent to an effective 5.5 percent between 2016‑17 and 2017‑18. The state’s increased share of costs amounts to almost $700 million in additional state spending for the ACA optional expansion in 2017‑18 compared to 2016‑17. Thus, much of Medi‑Cal’s Proposition 56 revenues supplant federal Medi‑Cal funding rather than state Medi‑Cal funding.

Significant Portion of Proposition 56 Revenues Paid to Medicare. The Governor proposes using over $300 million of Proposition 56 revenues to support increased payments to the federal government for Medicare. Most of this funding would pay for increased payments that Medi‑Cal makes to Medicare to offset a portion of the federal government’s costs for Medicare Part D. Medicare Part D transferred certain Medi‑Cal prescription drug costs from the state to the federal government. For taking on these costs, the federal government required state Medicaid programs to pay back to the federal government a portion of their savings resulting from the establishment of Medicare Part D.

Remainder of Proposition 56 Revenues Funds Managed Care. The Governor proposes to spend the remainder of Medi‑Cal Proposition 56 funding within Medi‑Cal managed care. This funding would support various increased costs in 2017‑18 compared to 2016‑17, including increased costs associated with higher utilization of Hepatitis C medications, caseload increases, and annual growth in managed care plans’ capitated rates.

LAO Assessment

Spending of Medi‑Cal’s Proposition 56 Revenues on New Policy Changes Could Require Spending Cuts Elsewhere. As discussed, the Governor’s budget proposes using Proposition 56 revenues to support anticipated spending increases in the Medi‑Cal program. The Governor does not propose any new policy changes, such as increases to Medi‑Cal provider payments, funded with Proposition 56 revenues. Should the Legislature wish to divert some or all Proposition 56 revenues to support new policy changes, the Legislature would need to allocate up to an additional $1.2 billion in 2017‑18 from the General Fund to Medi‑Cal to pay for the costs Proposition 56 covers under the Governor’s proposal. Under the Governor’s revenue estimates, doing so could require reductions to other programs or smaller budget reserves. Should the revenue estimates be higher in May, however, the Legislature would have more flexibility to allocate additional revenues to Medi‑Cal.

Back to the TopProposed Transition of New Qualified Immigrants to Covered California

Background

Federal Law Bars Most Legal Noncitizens From Receiving Full‑Scope Medicaid for Five Years. Under the federal Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA), most legal noncitizens cannot receive full federal financial participation for full‑scope Medicaid services for five years after arriving in the United States. Legal noncitizens are generally defined by federal law as those immigrants who are lawfully admitted to the United States. States receive federal funding to partially pay for the provision of limited‑scope Medicaid services—such as emergency medical services and pregnancy‑related services—for all legal noncitizens during the five‑year bar.

State Law Extends Full‑Scope Medi‑Cal to Legal Noncitizens During the Five‑Year Bar. Under PRWORA, states can choose to use their own funds to provide legal noncitizens with full‑scope Medicaid services during the five‑year bar. (States that provide full‑scope Medicaid services to legal noncitizens still receive federal funding to partially pay for limited‑scope Medicaid services.) California chose to create a state‑only Medi‑Cal program to cover legal noncitizens who would be eligible for full‑scope Medicaid but for their immigration status, individuals referred to as “new qualified immigrants” or NQIs.

ACA Optional Expansion Triggered Increase in the Number of NQI Adults Eligible for Medi‑Cal. A number of NQI adults—primarily childless adults present in the United States for less than five years—became eligible for Medi‑Cal as a result of the ACA optional expansion. We refer to these individuals as ACA optional expansion NQIs. The Governor’s budget estimates that 63,000 of these NQI adults are currently enrolled in the state‑only Medi‑Cal program for NQIs.

ACA’s Individual Mandate Applies to NQIs. The ACA requires—with some exemptions—individuals to enroll in health insurance coverage that meets certain minimum quality standards (otherwise known as “minimum essential coverage,” or MEC) or pay a tax penalty. This individual mandate also applies to NQIs.

NQIs Qualify for Premium Subsidies and Cost‑Sharing Reductions Through Covered California. While NQIs currently receive their health care coverage through the state‑only Medi‑Cal program, NQIs are also eligible for federal premium subsidies and cost‑sharing reductions to purchase coverage through a Health Benefit Exchange. The California Health Benefit Exchange, also known as Covered California, is an online health insurance marketplace where individuals are able to enroll in subsidized and unsubsidized coverage. Individuals with certain incomes qualify for federal tax credits to purchase coverage, known as premium subsidies. Some of those individuals with lower incomes also have their out‑of‑pocket costs reduced by federal payments to health insurers, known as cost‑sharing reductions.

Current State Law Requires Shift of ACA Optional Expansion NQIs Into Covered California With a Medi‑Cal Wrap. California passed legislation in 2013 that, in addition to conforming state law to several ACA regulations, required that NQIs eligible for full‑scope Medi‑Cal as a result of the ACA optional expansion transition from the state‑only Medi‑Cal program into subsidized coverage through Covered California with a Medi‑Cal “wrap.” The Medi‑Cal wrap would cover any benefits, premiums, or cost‑sharing not covered by these NQIs’ subsidized coverage through Covered California. Those eligible for the transition to Covered California with a Medi‑Cal wrap must purchase coverage through Covered California or would only qualify for limited‑scope Medi‑Cal services thereafter. The legislation is intended to leverage federal funding for premium subsidies and cost‑sharing reductions available to NQIs, while maintaining the level of care provided to NQIs through Medi‑Cal. By shifting ACA optional expansion NQIs into Covered California with a Medi‑Cal wrap, the state expects to save $48 million General Fund in 2017‑18. (Given the transition is effective January 1, 2018, General Fund savings in 2017‑18 from the transition represent approximately half of the savings in a full fiscal year.)

State’s Implementation of the Shift Delayed. The legislation discussed above was originally effective January 1, 2014. The development of new state information technology systems delayed the implementation of the program into 2016. The Legislature subsequently approved a further one‑year delay in the implementation of the program—from January 1, 2017 to January 1, 2018—because of concerns about disruptions and delays in ACA optional expansion NQIs accessing coverage and about the administrative complexities of the program.

Budget Proposal

Budget Proposes to Shift Additional NQIs Into Covered California With a Medi‑Cal Wrap. The Governor’s budget proposes to shift additional NQIs (that is, NQIs in addition to those whose eligibility for state‑only Medi‑Cal was triggered by the ACA optional expansion) into Covered California with a Medi‑Cal wrap starting January 1, 2018. These additional NQIs—not included in the state’s 2013 legislation that originally authorized the transition—are individuals eligible for Medi‑Cal under the pre‑ACA eligibility rules. Primarily, they are parents or caretaker relatives of minor children. An estimated 20,700 individuals would be affected by this change, bringing the total amount of NQIs transitioning to Covered California to 83,700. (NQI pregnant women, and NQIs under age 21 or over age 64, who would otherwise be eligible for this transition, are exempt from this proposal because their coverage is generally already certified as MEC.)

Budget Does Not Provide an Estimate of General Fund Savings From Proposal. As previously noted, the Governor’s budget estimates the state will save $48 million General Fund in 2017‑18 from the transition of the ACA optional expansion NQIs into Covered California pursuant to the 2013 legislation discussed previously. The budget, however, does not provide an estimate of the General Fund savings for the additional 20,700 NQIs who would transition into Covered California under this proposal. By the time of the Governor’s May Revision, the administration expects to provide an estimate of General Fund savings for this population.

Administration’s Rationale for Budget Proposal. The administration suggests the budget proposal will protect the additional NQIs from potential tax penalties under the ACA. The state‑only Medi‑Cal program for nonpregnant, nonelderly NQI adults is not formally certified by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) as MEC. Individuals are required to maintain MEC to avoid tax penalties under the ACA’s individual mandate. If the additional NQIs remain in the state‑only Medi‑Cal program, they could be subject to tax penalties. By transitioning the additional NQIs into Covered California with a Medi‑Cal wrap—coverage which would be formally certified as MEC—the administration argues the additional NQIs would be protected from these tax penalties. (We again note that nearly all remaining NQIs in the state‑only Medi‑Cal program—such as NQI pregnant women—already have MEC and are exempt from this proposal.) The administration also acknowledges the additional General Fund savings from these NQIs receiving federal funding for premium subsidies and cost‑sharing reductions through Covered California.

Proposed Trailer Bill Language Would Limit Choice of Covered California Health Plans. Proposed trailer bill language implementing the Governor’s budget proposal would also limit the number of health insurance coverage options available to transitioning NQIs to two lower‑priced health plans. The administration’s rationale for limiting the number of health plans is to limit the differences in plan premiums and cost‑sharing amounts, thereby reducing the complexity of the program for Covered California and DHCS.

Assessment

Budget Proposal Would Leverage Additional Federal Funding for Additional NQIs . . . The administration’s budget proposal to transition additional NQIs from the state‑only Medi‑Cal program into Covered California with a Medi‑Cal wrap would leverage additional federal funding for premium subsidies and cost‑sharing reductions that would be available to these additional NQIs through Covered California. While the exact amount of General Fund savings for this population is not known at this time, the potential savings from this proposal could be in the low tens of millions of dollars annually. The Legislature approved the concept of a transition of ACA optional expansion NQIs into Covered California in 2013 primarily to achieve General Fund savings from the additional federal funding available to these NQIs, while maintaining the level of care that is provided to NQIs through the state‑only Medi‑Cal program. For these reasons, the budget proposal’s transition of additional NQIs also has merit.

. . . But Administration’s Rationale for Budget Proposal Related to Avoidance of Tax Penalties Is Uncertain. In addition to the fiscal and policy rationale for the 2013 legislation, the administration provides another rationale for this proposal: to protect the additional NQIs from potential tax penalties under the ACA. It is uncertain whether or not NQIs are paying, or could in the future pay, tax penalties because the coverage they receive through the state‑only Medi‑Cal program is not formally certified as MEC. To date, DHCS is unaware whether or not any NQI enrolled in Medi‑Cal has paid a tax penalty.

Joint Enrollment of NQIs in Covered California Health Plans and Medi‑Cal Is Complex for Agencies and Health Plans to Administer. We note that there are several administrative complexities for federal and state agencies, as well as for health plans through Covered California, to address in implementing the transition of NQIs—both pursuant to the 2013 legislation and the Governor’s budget proposal—to Covered California coverage with a Medi‑Cal wrap:

- To enroll NQIs in Covered California health plans and in the Medi‑Cal wrap, a variety of federal and state agencies must first approve the health plans. Like other health plans offered through Covered California, health insurers must file plan documents with CMS, Covered California, and either the California Department of Managed Health Care or the California Department of Insurance (depending on the insurance product). DHCS also must work with Covered California to obtain approval from CMS for the health plans because of the Medi‑Cal wrap. Final approval of the health plans could extend beyond January 1, 2018.

- There are also a number of ways health insurers could structure the Covered California health plans around the federal premium subsidies and cost‑sharing reductions for NQIs. No matter how health plans are structured, federal and state agencies will need to develop new administrative processes for the program. Developing those processes could also extend beyond January 1, 2018.

- Program regulations will also need to be developed by the administration. Proposed trailer bill language would extend the deadline for those regulations from July 1, 2017 to July 1, 2020 (that is, beyond the scheduled January 1, 2018 implementation date). The emergency rulemaking process could be used prior to 2018 to implement this transition.

Any of these administrative complexities could delay the full implementation of the Governor’s budget proposal—as well as the transition of NQIs authorized in the 2013 legislation—beyond January 1, 2018. Such delays would reduce General Fund savings otherwise resulting from the transition of NQIs into Covered California.

Significant Federal Uncertainty About the Future of the ACA, Including the Federal Funding for NQIs Obtaining Subsidized Coverage Through Covered California. When the Legislature authorized the transition of ACA optional expansion NQIs into Covered California with a Medi‑Cal wrap in 2013, there was little federal uncertainty about the future of the ACA. By contrast, the current federal administration and congressional majority have stated their intent to make major changes to the ACA. We discuss the uncertain future of the ACA in a separate report—The Uncertain Affordable Care Act Landscape: What It Means for California. In our report, we outline congressional procedures—such as the federal budget reconciliation process—that could be used to facilitate the repeal of major components of the ACA, including federal funding for premium subsidies and cost‑sharing reductions through state Health Benefit Exchanges. Proposed trailer bill language implementing this budget proposal does make the transition of any NQI into Covered California inoperative should federal funding for state Health Benefit Exchanges be eliminated. If NQIs were transitioned under the Governor’s budget proposal into Covered California prior to it becoming inoperative, however, these individuals might have to be reenrolled in Medi‑Cal or an alternative form of coverage. This issue would also apply to NQIs transitioning to Covered California under the 2013 legislation.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

The Governor’s budget proposal could generate additional General Fund savings from increased federal funding for the additional NQIs, and is consistent with the concept driving the 2013 legislation. It therefore warrants serious consideration by the Legislature. We provide the Legislature with several issues to consider based on what action the Legislature takes on the proposal.

If LegislatureApproves the Proposal, There Are Implementation Challenges to Be Addressed. If the Legislature approves the proposal, it might consider directing DHCS to expedite the development and approval of Covered California health plans for all NQIs, including NQIs transitioning to Covered California under the 2013 legislation. Any delays in the development and approval of the health plans also delays the implementation of the transition, reducing General Fund savings. The Legislature might also consider directing relevant agencies, with input from insurers, to regularly report to the Legislature on how they are addressing the administrative complexities of the transition. Regular reporting could help the Legislature assess whether implementation of the transition is on schedule, or whether additional legislative action is necessary. The Legislature might also consider requesting DHCS to report on how many NQIs have been, or currently are, subject to tax penalties under the ACA. Lastly, the Legislature might consider directing DHCS to establish procedures for reenrolling NQIs in the state‑only Medi‑Cal program should federal funding for state Health Benefit Exchanges be eliminated. Clear guidance from DHCS on how NQIs would be reenrolled in health insurance coverage—should Covered California become inoperative—could address potential concerns from NQIs and stakeholders about disruptions and delays in obtaining coverage. For all of these implementation issues for additional NQIs transitioning to Covered California, the Legislature could address similar issues for ACA optional expansion NQIs.

If Legislature Rejects the Proposal, the 2013 Legislation Should Also Be Reconsidered. If the Legislature rejects the proposal—for example, because of legislative concerns about the federal uncertainty around premium subsidies and cost‑sharing reductions through Covered California—the Legislature might also consider whether or not to continue the planned transition under the 2013 legislation of ACA optional expansion NQIs into Covered California coverage with a Medi‑Cal wrap. This is because any concerns about the transition proposed under the Governor’s budget are likely also to apply to the planned transition under the 2013 legislation.

We note that if the Legislature decides to repeal the authorized transition of ACA optional expansion‑triggered NQIs into Covered California coverage, the Legislature might also consider directing DHCS to apply for CMS to certify the state‑only Medi‑Cal program for NQIs as MEC. CMS approval of the state‑only Medi‑Cal program for NQIs would protect these Medi‑Cal enrollees from potential tax penalties under the ACA. There would be a fiscal trade‑off, however, with this action, as General Fund costs would increase by an estimated $100 million annually because NQIs would no longer qualify for premium subsidies and cost‑sharing reductions through Covered California. We understand that under current federal law, such disqualification from federal assistance through Covered California would be permanent.

Back to the TopCHIP Funding

Background

CHIP Provides Health Insurance to Low‑Income Children. CHIP is a joint federal‑state program that provides health insurance coverage to children in low‑income families, but with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid. States have the option to use federal CHIP funds to create a stand‑alone CHIP program or to expand their Medicaid programs to include children in families with higher incomes (commonly referred to as Medicaid‑expansion CHIP). California transitioned from providing CHIP coverage through its stand‑alone Healthy Families Program to providing CHIP coverage through Medi‑Cal. With this transition, completed in the fall of 2013, Medi‑Cal generally provides coverage to children in families with incomes up to 266 percent of the FPL. Some infants in families with incomes up to 322 percent of FPL may also be eligible for Medi‑Cal. DHCS estimates that there will be over 1.3 million children enrolled in CHIP coverage in 2017‑18.

FMAP for CHIP Is Traditionally Higher Than for Medicaid. Traditionally, the federal government provides an enhanced FMAP for CHIP health insurance coverage in California relative to the Medicaid FMAP of 50 percent. The historical FMAP for the CHIP population has been 65 percent, although this has been further enhanced by the ACA, as discussed below.

CHIP Funding Is Capped. Unlike Medi‑Cal, CHIP is not an entitlement program. States receive annual allotments of CHIP funding based on historic CHIP spending. A change in a state’s CHIP FMAP also changes the state’s annual allotment. Generally, states receive allotments that are sufficient to cover the federal share of CHIP expenditures for the full year. If a state does not spend its full annual allotment in the given year, the state may continue to draw down unspent funds in the next year.

The ACA and CHIP

ACA Authorized an Increased FMAP for CHIP, but Congress Has Only Appropriated Funding Through Federal Fiscal Year (FFY) 2016‑17. Beginning in FFY 2015‑16, the ACA authorized an increased FMAP for CHIP through FFY 2018‑19. (An FFY runs from October 1 through September 30.) Under the ACA, California’s CHIP FMAP increased from 65 percent to 88 percent. The ability of California to draw down federal CHIP funds at this higher FMAP, however, is dependent on Congress’ decision regarding the appropriation of funding for CHIP beyond FFY 2016‑17, as Congress has only appropriated funding for CHIP through FFY 2016‑17. The implications of this for California’s budget are discussed further below.

ACA Required Part of CHIP Population to Be Covered Through Medicaid. Under the ACA, states must provide Medicaid coverage to children up to age 19 with family incomes up to 138 percent of FPL (which is referred to as the “federal minimum standard”). Previously, children between the ages of 6 and 19 with family incomes between 108 percent and 138 percent of the FPL could be covered through states’ CHIP programs. The federal government currently pays the higher CHIP FMAP (currently 65 percent in California) for this population. States will be required to continue providing Medicaid coverage to this population at the lower Medicaid matching rate (50 percent in California) if CHIP funding runs out.

ACA Maintenance‑of‑Effort (MOE) Requirements for CHIP and Medicaid. Under an ACA MOE provision, states are required to maintain their March 23, 2010 Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels for children through the end of FFY 2018‑19. The implications of these MOE requirements are uncertain for California because the state transitioned from a stand‑alone CHIP program to a Medicaid‑expansion CHIP program after March 2010. The CMS will need to clarify the implications of the ACA MOE requirements for California if Congress does not appropriate additional CHIP funding through FFY 2018‑19.

Budget Proposal

Budget Assumes Federal Funding for CHIP Is Authorized at Traditional FMAP. The Governor’s budget assumes CHIP funding is reauthorized in FFY 2017‑18, but at a 65 percent FMAP in California instead of the 88 percent FMAP authorized by the ACA. At this lower FMAP, DHCS estimates the state will spend an additional $535 million (mostly General Fund) in 2017‑18 (relative to what it would have spent at the ACA‑enhanced FMAP of 88 percent). Given that Congress has not appropriated funds for CHIP beyond FFY 2016‑17, the amount of CHIP funding, if any, allotted to California for FFY 2017‑18 is uncertain. It is certain that California will remain at the 88 percent FMAP from July 1, 2017 through September 30, 2017, because this three‑month period overlaps with FFY 2016‑17. The CHIP funding for the rest of 2017‑18 is less certain and could have a significant impact on the state’s budget.

Congress’ Decision on CHIP Funding Could Result in Higher or Lower General Fund Costs in Medi‑Cal Budget. The decision Congress makes regarding appropriations of CHIP funding beyond FFY 2016‑17 has implications for the state’s General Fund spending in Medi‑Cal. Figure 4 summarizes three potential congressional actions that could be taken on CHIP funding beyond FFY 2016‑17.

Figure 4

Potential Congressional Actions on CHIP Funding Beyond FFY 2016‑17

|

Scenario |

FMAPa |

Change in 2017‑18 General Fund Spending in Medi‑Cal |

|

No new CHIP funds appropriated |

50 percentb |

$350 million increasec |

|

New CHIP funds appropriated at traditional FMAP |

65 percent |

No change |

|

New CHIP funds appropriated at ACA‑enhanced FMAP |

88 percent |

$535 million decreased |

|

aFMAP is the percentage of state Medicaid costs paid by the federal government. bAssumes state would continue to provide Medi‑Cal coverage to CHIP‑eligible children at lower FMAP. cWould depend on the amount of FFY 2016‑17 CHIP funds the state carries over into FFY 2017‑18. dIncludes a small portion of special funds from the Perinatal Insurance Fund. |

||

|

CHIP = Children’s Health Insurance Program; FFY = federal fiscal year; FMAP = federal medical assistance percentage; and ACA = Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. |

||

LAO Assessment. The Governor’s approach to budgeting CHIP funding is reasonable given the uncertainty. Across the range of potential actions Congress may take on CHIP funding, the Governor’s budget assumes a middle‑of‑the‑road scenario. However, as discussed above, federal CHIP funds available to California in 2017‑18 could be significantly more or less than assumed in the Governor’s budget, depending on the action ultimately taken by Congress.

Back to the TopProposed Abolition and Transfer of MRMIF

Background

Major Risk Medical Insurance Program (MRMIP). MRMIP provides health insurance coverage to individuals who, prior to the ACA, could not obtain coverage or were charged unaffordable premiums in the individual health insurance market because of their preexisting conditions. MRMIP was originally conceived as a state high‑risk pool. The ACA prohibits health insurers from imposing preexisting condition exclusions, including denying coverage, charging more for coverage, and limiting or refusing to cover benefits associated with an individual’s preexisting condition. Given the ACA’s prohibition on preexisting condition exclusions, MRMIP enrollees can now obtain coverage through, for example, the state’s Health Benefit Exchange—Covered California. As a result, MRMIP enrollment has steadily declined from 6,570 enrollees in 2013 to 1,332 enrollees in 2016. MRMIP enrollees, however, may choose not to enroll in other coverage because, for example, they are ineligible based on their immigration status. (Undocumented individuals are eligible for coverage through MRMIP, but are not eligible for premium subsidies and cost‑sharing reductions through Covered California.)

MRMIF. Administered by DHCS, MRMIF pays for any MRMIP costs in excess of what MRMIP enrollees pay in the form of premiums, deductibles, and copayments. The state spent roughly $10 million from MRMIF in 2016‑17. The remaining MRMIF balance is estimated to be $69 million in 2016‑17, most of which comes from ongoing revenue transferred to MRMIF from the Managed Care Administrative Fines and Penalties Fund. This fund, administered by the Department of Managed Health Care, is used to deposit various administrative penalties and fines for the licensing and regulation of health care service plans. The first $1 million deposited into this fund is transferred to the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development for one of its loan repayment programs. The remaining fund amount is transferred to MRMIF. In 2016‑17, an estimated $3.4 million in revenue will be transferred from the Managed Care Administrative Fines and Penalties Fund to MRMIF. Administrative fines and penalties vary substantially from year to year: in 2015‑16, $8.5 million was transferred to MRMIF.

Budget Proposal

Budget Proposes Eliminating MRMIF, Transferring Fund Balance and Ongoing Revenue to New Health Care Services Plans and Penalties Fund. The Governor’s budget proposes to abolish MRMIF and transfer its fund balance and any ongoing revenue from the Managed Care Administrative Fines and Penalties Fund into a newly created Health Care Services Plans and Penalties Fund, also administered by DHCS. The administration’s rationale for abolishing MRMIF, and transferring its monies to another fund for other purposes, is the significant reduction in MRMIP enrollees since the ACA’s implementation (the prohibition on denying coverage due to preexisting conditions) and the need for additional funding in the state’s Medi‑Cal program.

Budget Proposes Using Fund Balance and Ongoing Revenue for Medi‑Cal. Once the Health Care Services Plans and Penalties Fund covers all MRMIP expenses, the Governor’s budget proposes to use the fund’s remaining balance in 2017‑18 and any ongoing revenues thereafter to cover overall Medi‑Cal expenses. The administration’s rationale for this proposal is that a substantial portion of MRMIF monies are idle and by using them to fund Medi‑Cal, the monies would be used in a manner consistent with MRMIF’s purpose of providing health care coverage.

LAO Assessment. We find the Governor’s budget proposal to be reasonable, particularly given the high remaining MRMIF balance that is likely to go substantially unused for many years and the ability to tap ongoing revenues deposited into MRMIF to be used instead to address pressing budgetary funding requirements. We acknowledge, however, that there remains substantial federal uncertainty about the future of the ACA and, consequently, whether there could be an ongoing need for a state high‑risk pool like MRMIP. For example, some ACA replacement proposals currently being considered by Congress include what would be a reinvigorated role for state high‑risk pools, perhaps with a federal funding contribution. Should these proposals come to fruition, the Legislature would want to reevaluate the role and financing of MRMIP.