Additional Content

March 30, 2017

The 2017-18 Budget

Considering the State's Role in Elections

- Introduction

- Elections in California

- SB 450: New Model for Voting in California

- Roles and Responsibilities in Elections

- State Funding of County Election Activities

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

Counties Administer Most Elections and Pay Elections Costs. As traditionally has been the case across the United States, county governments in California administer most local, state, and federal elections pursuant to state and federal law. Typically, counties appropriate funds from their general funds to pay for costs related to administering elections. Cities, special districts, and schools pay for a share of elections costs as well. Often, these local governments reimburse the county based on the proportion of the ballot dedicated to the local governments’ candidates and issues. Neither the state nor the federal government provides regular payments for county elections administration.

State Requires Certain Activities in Elections Administration. Since 1975, the state must pay for the associated cost (in most cases) of election‑related requirements imposed on counties. These requirements are called reimbursable mandates. The state has placed a handful of requirements on counties related to elections administration costing roughly $30 million in general election years. For many years, however, the state has suspended the mandates. When a mandate is suspended, the requirement remains in law but local governments do not have to comply with the requirements in that year and the state has no reimbursement obligation. Counties typically have continued to comply with these requirements, effectively paying for these state‑priority costs with local funds.

Recent Law Created Optional New Voting Model. Under SB 450 (Chapter 832 of 2016), counties may replace the current precinct model of voting with a new “vote center” model. Rather than opening thousands of polling places, implementing counties will be required to open a certain number of vote centers (based on population). Vote centers will be similar to polling places, but will offer more services than polling places and be open for more days.

Effective Elections Administration an Important State Interest. The state has a clear interest in secure, timely, and uniform elections. While the state reaps regular benefits from county elections administration, it only sporadically provides funding to counties for election activities. Relying on the existing mandates system to provide state support to elections is ineffective. We recommend the Legislature develop a new financial relationship between the state and counties to (1) direct statewide elections policy and (2) provide a reasonable and reliable level of financial support that reflects the benefits to the state of county elections administration. The pending implementation of SB 450 provides an opportunity for the Legislature to consider how to structure such a financial relationship to ensure consistency across counties as well as address other elections issues.

Create Block Grant for Ongoing Support. We suggest the Legislature consider sharing in the cost of elections through a block grant. A block grant would provide counties state support to partially offset county costs to comply with a range of elections activities specified by the Legislature. In addition to making block funding contingent on county implementation of the vote center model, the Legislature could include other elections issues like timely vote counting, protecting elections systems, keeping voter registration current, and complying with existing suspended mandates. There are various options for how to distribute the block grants. For example, basing the grant amount on the number of registered voters could encourage counties to increase voter registration.

Introduction

In 2016, the Legislature passed and the Governor signed SB 450, the Voter’s Choice Act (Chapter 832). The law allows counties to implement a new model of voting that enables voters to cast their votes over a period of days prior to election day. This new model is a significant change in state elections policy. A subset of counties may implement the new model in 2018. All other counties may move to this model in 2020. This report discusses the landscape of elections administration in California today and the changes to that landscape in counties choosing to adopt the new elections model permitted. We then layout a framework for considering the roles and responsibilities in elections. The report concludes by outlining options the Legislature could consider to provide financial support to counties for elections administration to ensure secure, timely, and uniform elections. The Governor’s budget does not include any state support for elections administration or SB 450 implementation.

Elections in California

Administration

Counties Administer Most Elections. As traditionally has been the case across the United States, county governments in California administer most local, state, and federal elections pursuant to various requirements established under state and federal law. County elections officials administer almost every part of voting in California including: processing voter registrations; accepting candidate filings; verifying signatures on petitions to qualify initiatives for the ballot; determining what equipment voters use to cast ballots at polling places; establishing precinct boundaries and poll locations; printing ballots and sample ballots; mailing materials to voters (including ballots for people who vote by mail); hiring and training poll workers and other temporary staff; receiving ballots; and tabulating election results.

Secretary of State Provides Statewide Oversight and Direction. The Secretary of State is the state’s chief elections officer and oversees county administration of all federal and state elections within California. The Secretary of State oversees county administration of elections by promulgating regulations that provide direction to counties about how to comply with statute; advising local elections officials on how to administer elections; testing and approving all voting equipment used in the state; coordinating and compiling the tabulation of votes from each county; and certifying final election results. In addition, the Secretary of State has many direct administrative responsibilities in statewide elections including: maintaining the statewide voter registration system, known as VoteCal; tracking and certifying initiatives for the statewide ballot; determining the order of candidates on the ballot; and printing and mailing the statewide voter guide.

Funding

County General Purpose Funds Pay Elections Administration Costs. Typically, a county appropriates funds from its general fund to pay for costs related to administering elections. As is the case with any general purpose funds, boards of supervisors must determine how to allocate these limited resources among a number of competing priorities.

Local Governments Typically Pay County to Administer Elections. Counties often administer elections for cities, special districts, and schools in the county. These local governments typically pay counties for administering their local elections, based on the proportion of the ballot dedicated to the local governments’ candidates and issues put to the voters—this cost allocation sometimes is referred to as “ballot real estate.”

State Has Not Provided Regular Payments for Elections Administration. The state requires various activities to be performed by counties when administering elections. Proposition 4 (1979) requires the state to reimburse local governments for requirements placed upon them by the state after 1975. These requirements are called reimbursable state mandates. Some required elections activities are reimbursable state mandates. Prior to Proposition 1A (2004), there was no payment schedule for reimbursing local governments for these state mandates. As a result, the state went many years without paying counties for the costs associated with certain state elections requirements. Proposition 1A required the state (1) to reimburse local governments for these outstanding prior years’ mandates costs and (2) either to suspend or reimburse local governments for state mandates on an ongoing basis. Mandates can be suspended as part of the annual budget bill. When a mandate is suspended, the requirement remains in law but local governments do not have to comply with the suspended mandate requirements in that year.

For many years, the state has suspended election mandates, providing no regular assistance to counties. Currently, the state owes counties about $71 million for outstanding elections mandates incurred in prior years. Despite these mandates being suspended, counties continue the activities associated with the suspended laws—costing counties roughly $30 million in general election years. Although the state has not paid for these regular ongoing costs, it has provided one‑time funds to counties on occasion for particular elections issues. Below, we discuss a few examples of when counties have received one‑time funds from the federal or state governments to address specific needs in administering elections.

One‑Time Federal and State Funding in 2002. Voting equipment and the administration of U.S. elections became a prominent issue following the contested presidential election in 2000. At the federal level, the Help America Vote Act of 2002 (HAVA) established standards for federal elections. To help state and local governments implement the requirements established under HAVA, the federal government provided funding to the states. California received $392 million in federal funds to implement the mandates established under the federal law—$195 million of which was allocated to counties to comply with HAVA voting system requirements. Of the $195 million, the Secretary of State indicates that—as of July 20, 2016—counties have $35.6 million remaining for these purposes. Thirty counties have expended all of the federal funds available to them for this purpose, and nine counties have more than 50 percent of their allocated federal funds still available. In addition to federal funds made available to counties in 2002, California voters also approved the issuance of $200 million in state bonds for counties to procure new voting equipment. The nearby box explains what happened with these funds.

A False Start in Modernizing California Voting Equipment

Bond Money Provided to Counties on Matching Basis to Replace Voting Equipment. Voters approved Proposition 41 in 2002. The proposition allowed the state to sell $200 million in general obligation bonds to assist any county in the purchase of new voting equipment that was certified by the Secretary of State. In order to receive bond monies, a county had to expend $1 of county funds to receive $3 of bond monies—a three‑to‑one ratio of state‑to‑county money. The proportion of the bond monies available to each county depended on a formula that took into account each county’s number of eligible, registered, and participating voters and number of polling places. In addition to Proposition 41 money, the federal government provided $195 million to upgrade voting systems in 2002.

Decertification of Purchased Voting Equipment. In the years following Proposition 41’s passage, some counties replaced defunct punch card voting systems with electronic voting equipment. By 2005, actions taken by then Secretary of State Kevin Shelley and the Legislature imposed certain restrictions on electronic voting systems. In 2007, then Secretary of State Debra Bowen established new rules relating to the testing and requirements of electronic voting equipment. Through these state actions, several counties were forced to abandon their recently purchased electronic voting systems and, instead, rely on paper‑based, optical scan technology. Little has changed since 2007—most counties continue to use paper‑based, optical scan systems for polling place voting.

One‑Time State Funding in 2016. In spring 2016, the Secretary of State raised concerns to the Legislature that counties were facing high overtime costs and other expenses related to unusually high numbers of (1) initiatives seeking qualification for the November 2016 general election and (2) residents registering to vote before the June 2016 primary. The Legislature made available $16.3 million in one‑time state funds to reimburse counties for specified election costs through Chapter 11 of 2016 (AB 120, Committee on Budget). The Secretary of State reports that 47 counties received reimbursements totaling $15.7 million. The specific amount received by each county varied depending on the county’s number of (1) eligible voters and (2) signatures on initiative petitions being verified.

Voting

Beyond the specific requirements established in state and federal law, county elections officials have discretion in how people vote in their county. Consequently, election operations—including equipment used to cast and count ballots—vary across counties. In addition, voter preferences vary across the counties, affecting the proportion of (1) eligible voters who are registered to vote and (2) registered voters who vote by mail or in person at the polling place.

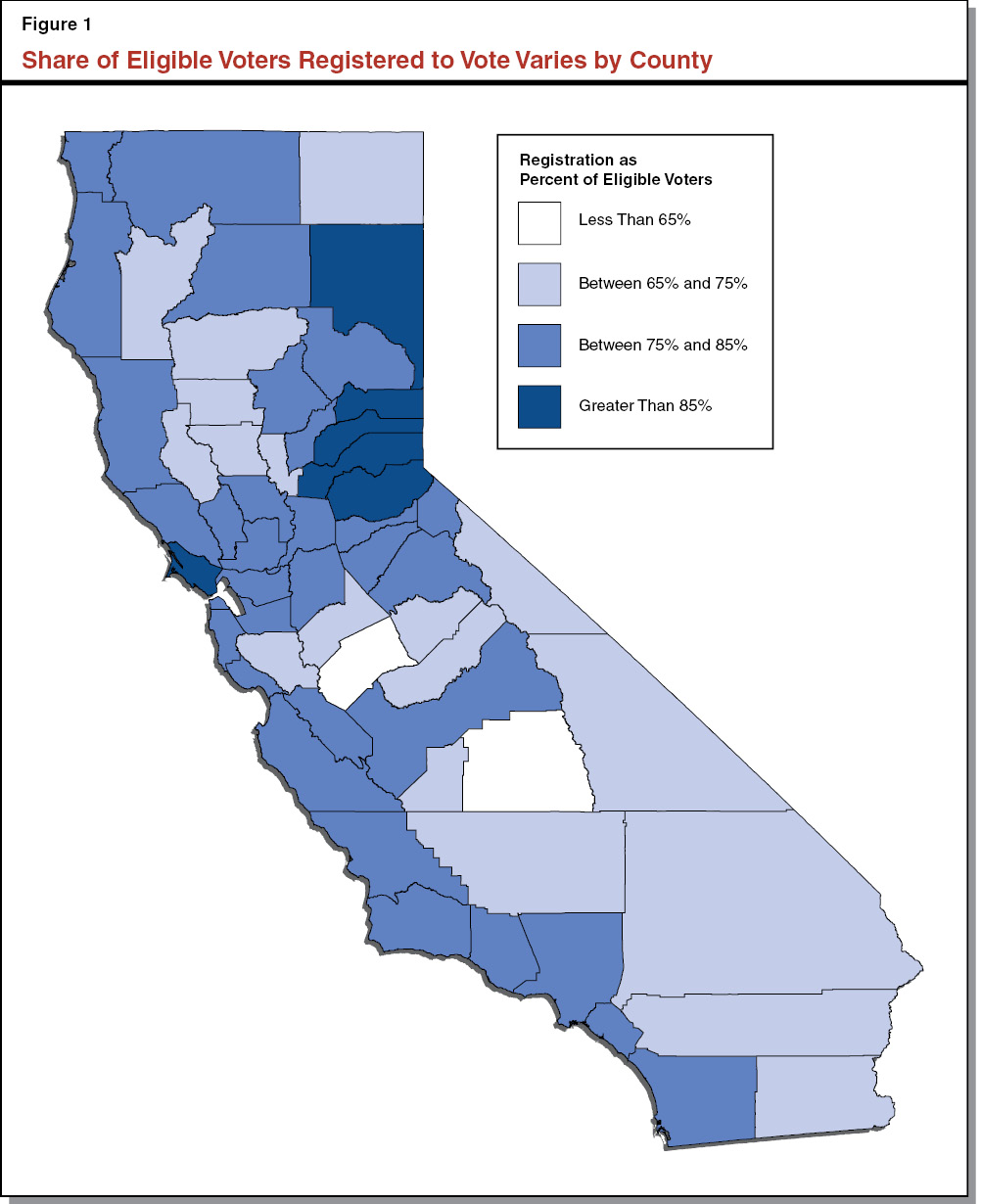

Voter Registration in California. To be eligible to vote in California, a person must be (1) a U.S. citizen, (2) a resident of California, (3) at least 18 years old on election day, (4) not currently incarcerated or on parole for the conviction of a felony, and (5) not prohibited from voting by a court due to mental capacity. Individuals can register to vote up to and including election day. Individuals registering within two weeks of election day are conditionally registered—pending verification they are not registered elsewhere—and must use “provisional” ballots. (Provisional ballots are used when there are questions about a given voter’s eligibility. Once his or her eligibility to vote is verified, the ballot is counted.) As of October 24, 2016, the Secretary of State reported that 78 percent of the approximately 25 million people eligible to vote in California were registered to vote in the November 2016 general election. Figure 1 shows how voter registration varies across the state by county.

Voter Participation in California. In the November 2016 election, about 14.6 million votes were cast in California. This means that about three‑fourths of registered voters in the state participated in that election. Voter participation—or “turnout”—varies significantly by the type of election, among other factors. Voter turnout in presidential elections tends to be higher, for example, while turnout for special elections tends to be low. For example, in the November 2016 election 68 percent of registered voters in Los Angeles voted; however, in the March 7, 2017 consolidated municipal and special election, fewer than 20 percent of registered voters cast ballots.

Precinct Model of Voting. The traditional voting model relies on precincts—a geographical subdivision of a county determined by a county’s elections official. State law generally requires that each precinct include no more than 1,000 voters (excluding permanent vote by mail voters). Counties with high populations have thousands of precincts. Each address in a county is assigned a precinct. Each precinct has a polling place where voters are expected to cast their ballot. If a voter goes to a polling place other than the one designated for his or her precinct, the voter must cast a “provisional” ballot. Depending on the election, each polling place may have numerous ballot types—for example, at a primary election the polling place may have different ballots for each political party. In a general election, ballots will vary based on the governments and representatives serving the precincts at the polling place. (For example, voters served by two different school districts may be assigned to the same polling place and require different ballots for school board candidates.)

Voting by Mail a Popular Alternative. California voters have the choice to cast their ballots in person at a polling place or through the mail. Voters who choose to vote by mail can do so on a one‑time or permanent basis. Voting by mail has become increasingly popular. Statewide, about 12.2 million voters—nearly 63 percent of all registered voters—received a mail ballot in the November 2016 general election. About 70 percent of these vote‑by‑mail (VBM) ballots were returned (either through the U.S. Postal Service or dropped at polls) to county elections officials to be counted. In total, about 58 percent of the 14.6 million ballots cast in the November election in California were VBM ballots. The share of voters casting VBM ballots in that election varied across the state from fewer than one‑half of voters casting their ballots by mail in Los Angeles, Lassen, and Merced Counties to more than 90 percent of registered voters voting by mail in Napa, Alpine, Plumas, and Sierra Counties.

Antiquated Equipment and Systems Used by Most Counties. All but a few counties in the state use voting systems that are more than a decade old. In many cases, components of the systems no longer are supported or produced by manufacturers. In one example, a county’s system had a failed part that no longer is supported by the manufacturer or easy to replace. The county purchased a replacement part through eBay. In another example, a county uses the same system it used in the 1990s. Although this county’s system has been updated periodically, it currently relies on computers that operate on Microsoft Windows XP—an operating system that was released in 2001 and no longer receives free security upgrades or other support from the manufacturer. Both of these examples raise serious concerns about the security of the voting system as well as the possibility of a catastrophic failure of voting systems in counties. Updating these systems requires money and political support from counties to spend the necessary funds on these upgrades instead of other priorities in their budgets. In many cases, counties appear to be allowing their systems to “limp along” in the hope that the state or federal government will again provide financial assistance to replace the systems.

Some Counties Plan to Replace Equipment Soon. Although many counties we spoke with have no imminent plans to replace their equipment, a few counties recently acquired new voting systems. Other counties have established plans to replace their existing systems within a certain number of years, regardless of whether they receive state or federal funds. Most counties with plans to replace their existing systems intend to purchase or lease equipment from one of a handful of vendors.

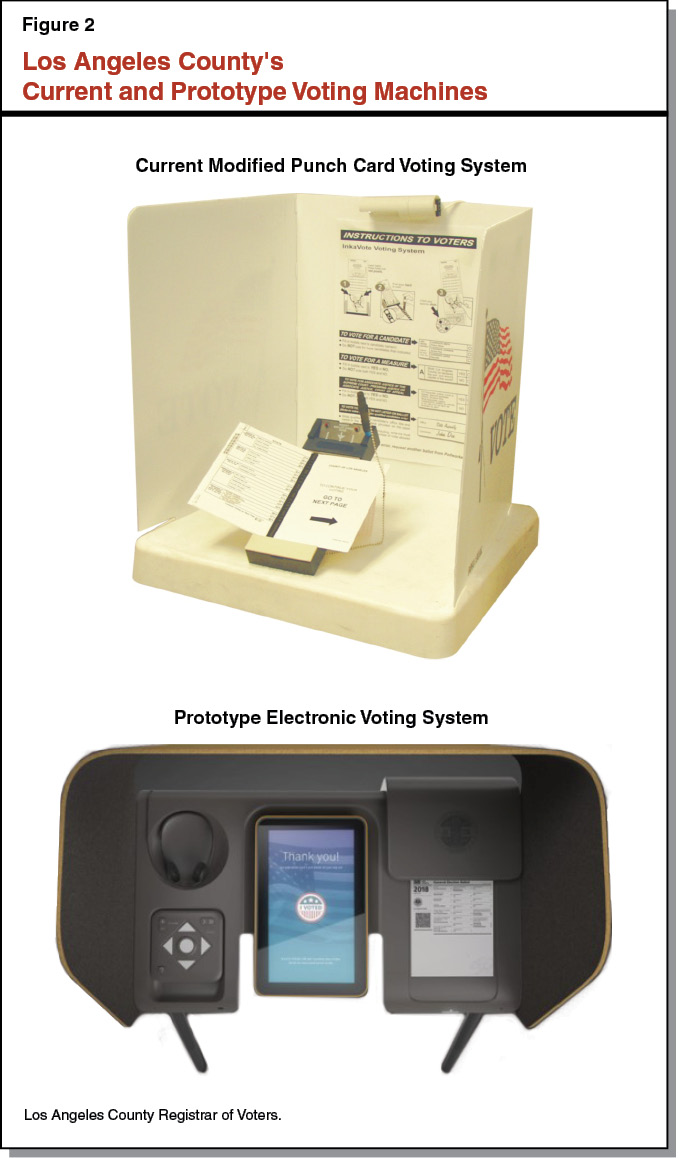

Los Angeles County is taking a different approach. It currently uses one of the most antiquated voting systems in the state. Their system is referred to as a “modified punch card” system, which converts punch card ballots into marked ballots. This modification prevents failed punches, but still relies on the old system. Instead of purchasing or leasing a system maintained by a vendor, Los Angeles County is in the late stages of developing its own open source system. Although the county will rely on a vendor to manufacture the equipment, the county will own all intellectual rights to the system. Figure 2 shows photographs of the current modified punch card system and the prototype of the county’s new system.

SB 450: New Model for Voting in California

Under SB 450, counties may replace the current precinct model of voting with a new “vote center” model. This section explains the structure of the new model for counties other than Los Angeles County. The requirements for Los Angeles County vary somewhat, but the overarching structure is the same.

Changes to Elections Administration

Implementation Is Optional. Counties are not required to implement SB 450. Doing so is at the discretion of county elections officials. Fourteen counties—Calaveras, Inyo, Madera, Napa, Nevada, Orange, Sacramento, San Luis Obispo, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Shasta, Sierra, Sutter, and Tuolumne—may implement SB 450 for the 2018 election cycle. All other counties may implement the system for the 2020 election cycle.

Vote Centers Replace Polling Places. Rather than open thousands of polling places, implementing counties will be required to open a certain number of vote centers (based on population). Vote centers will be similar to polling places, but will offer more services to voters. Counties will have far fewer vote centers than polling places, but the center will be open for longer periods before an election.

All Registered Voters Receive Vote by Mail Ballots. In implementing counties, all registered voters will receive a vote‑by‑mail ballot. This is different from the model that exists today, which requires voters to request VBM ballots. Under the vote center model, voters may submit their VBM ballots by mail (which requires postage), by turning them in at drop boxes (located throughout the county), or by returning their ballots to a vote center or the county registrar of voters.

Vote Centers Open Ten Days Prior to Election Day. Senate Bill 450 requires implementing counties to open at least one vote center per 50,000 registered voters ten days prior to election day. (Counties with fewer than 50,000 registered voters must open two vote centers.) Three days prior to election day, counties must open at least one vote center per 10,000 registered voters. The vote centers also must be open on election day. (In some cases, counties may have slightly fewer vote centers in the three days prior to election day; however, counties with at least 20,000 registered voters must have at least two vote centers during this period.) At a vote center, a voter can register to vote or update his or her voter registration and/or cast his or her vote either by turning in a VBM ballot or using a voting machine. Vote centers must meet accessibility and language requirements as defined in current law. As prescribed by the measure, vote centers also must be distributed across the county “so as to afford maximally convenient options for voters” and “established at accessible locations as near as possible to public transportation routes.”

A Voter Can Use Any Vote Center in County. Today, a voter not wishing to use a VBM ballot and, instead, vote in person must go to his or her designated polling place. Under SB 450, a voter can use any vote center in his or her county. If a registered voter does not bring his or her VBM ballot to the vote center, he or she can receive a ballot and vote there. As a result, vote centers must be able to provide all ballot types at every vote center. Each county has multiple ballot types to reflect the different governments and districts serving and representing each resident.

Individuals Can Simultaneously Register and Vote at Vote Centers. As noted earlier, vote centers will be able to register voters and allow newly registered voters to vote in person. To do this, vote centers will have to check whether an individual is already registered in another county as well as whether the individual already cast a ballot. As the statewide voter registry of record, VoteCal will allow counties to do these checks.

Implementing Counties Must Have Plan Approved by Secretary of State. Counties implementing SB 450 must develop a plan for implementing the statute’s requirements. The plan must be developed with input from communities across the county. Moreover, counties must meet with community groups to discuss the plan and allow for public comment. Once a county’s plan is finalized, the county must submit the plan to the Secretary of State for approval. The Secretary of State may approve, approve with modifications, or reject a county’s plan. Counties must update these plans every few years with input from their communities.

Fiscal Effects on Counties Uncertain

Overall SB 450 Costs May Be Lower Than Current Model in Some Counties. To implement SB 450, counties will have to establish vote centers, provide all ballot types at every vote center, and mail all registered voters a VBM ballot, among other requirements. These activities come with some amount of new costs not incurred under the current voting model. For instance, some counties may have to pay for the use of facilities for vote centers. Vote centers also may require additional paid staff for some counties. On the other hand, some costs associated with the current voting model may decline. For instance, the SB 450 system requires fewer voting machines. Under the current model, counties need voting machines for potentially thousands of polling places. Under SB 450, counties will only need equipment for the significantly fewer vote centers. Whether overall elections costs will increase or decrease with the implementation of SB 450 likely will vary by county. A couple of counties considering implementing SB 450 in 2018 indicated that they believe overall costs will decline largely as a result of needing fewer voting machines and hiring fewer poll workers. (These counties need to update their voting equipment for the 2018 election regardless of whether they implement SB 450.) Despite the potential long‑term savings of SB 450, some counties may not implement the new model. In part, this may be because additional costs to implement the measure must be incurred now while net benefits might not be realized for many years.

Remaining Work and Challenges

Secretary of State Finalizing Necessary Regulations. The Secretary of State indicates that it has nine packets of regulations that it is preparing to submit to the Office of Administrative Law in order to complete the regulatory process and promulgate regulations related to SB 450 implementation. The need for these regulations preceded the passage of SB 450. While SB 450 does not require new regulations itself, its passage assumed these regulations would be in place. Figure 3 summarizes these regulations. The Secretary of State is soliciting regular input from the counties and is working closely with the statewide association of county elections officials to develop these regulations. The Secretary of State hopes to have established some regulations as soon as within a few months, while others likely will be completed several months from now—perhaps in 2018. The Secretary of State has identified which regulations it sees as a priority for SB 450 implementation and hopes to promulgate these higher priority regulations first. Although the Secretary of State is working closely with counties, many counties have indicated that they are concerned that the amount of time it is taking to promulgate these regulations will hamper their abilities to implement the SB 450 vote center model in 2018. To date, the state has not provided the Secretary of State any new resources to implement SB 450 despite bill analyses that indicated the Secretary of State would incur roughly $300,000 in additional annual costs.

Figure 3

Status of Regulations Related to Elections Administration

|

Subject |

Associated Statute |

Description |

Status |

|

Conditional voter registration |

Chapter 497 of 2012 (AB 1436) |

Requirements related to the procedures for conditional voter registration. |

Developing draft. |

|

Recounts |

Chapter 723 of 2015 (AB 44) |

Requirements related to the procedures for recounting ballots and how counties can impose charges on other governments for recounts. |

Developing draft. |

|

Ballot pickup |

Chapter 724 of 2015 (AB 363) |

Requirements related to sealing of ballots and delivery of ballots to central counting location. |

Draft developed. |

|

VoteCal |

Chapter 728 of 2015 (AB 1020) |

Various changes to voter registration procedures related to the state’s voter registration system of record, VoteCal. |

Draft developed. External review expected in April. |

|

Motor Voter |

Chapter 729 of 2015 (AB 1461) |

Requirements related to canceling voter registrations of persons who are ineligible to vote. Also includes requirements for education and outreach on new Motor Voter registration law. |

Submitted to OAL. Public comment period ends in April. |

|

Vote by mail drop boxes |

Chapter 733 of 2015 (SB 365) |

Requirements related to the security of vote by mail drop off locations and drop boxes. |

Draft developed. External review expected in April. |

|

Ballot printing |

Chapter 734 of 2015 (SB 439) |

Requirements for “ballot on demand systems,” which print ballots for voters as needed. |

Rulemaking documents drafted. SOS anticipates submitting regulations to OAL in April. |

|

ePollbooks |

Chapter 734 of 2015 (SB 439) |

Requirements for “ePollbooks” and their use. ePollbooks contain information regarding registered voters. |

Rulemaking documents drafted. SOS anticipates submitting regulations to OAL in April. |

|

Vote‑by‑mail and provisional ballot processing |

Chapter 821 of 2016 (AB 1970) |

Requirements for processing vote by mail and provisional ballots. |

Draft developed. |

|

SOS = Secretary of State and OAL = Office of Administrative Law. |

|||

Unlikely That All Authorized Counties Will Implement the New System in 2018. Those counties permitted to implement SB 450 in 2018, as well as Los Angeles County, are participating in an ongoing workgroup with the Secretary of State. Based on conversations in those workgroups as well as discussions with counties, we do not believe that all counties permitted to implement SB 450 in 2018 will do so. In some cases, county registrars are concerned about garnering sufficient support for the new system from their communities and boards of supervisors. In other cases, counties are unsure as to whether or not they can meet the equipment needs—and other related costs—associated with implementation. Counties permitted to implement the new model in 2018 will likely decide whether to do so later in 2017.

Significant Voter Outreach Will Be Needed. As mentioned earlier, county registrars are required to do significant outreach when developing their SB 450 implementation plans. In addition, counties will need to do significant outreach to voters when shifting to the new model. Voters who are not permanent vote‑by‑mail voters will need to understand why they are receiving VBM ballots and their options for casting their votes. For example, in many cases, voters who choose to vote in person have gone to the same polling place in their neighborhood for decades to cast their ballots. Without sufficient outreach, these voters may not understand why they (1) are receiving a ballot in the mail and (2) cannot vote at their customary polling place (assuming the polling place is not being used as a vote center). Reaching out to voters will be particularly important due to the fact that some counties will be implementing the new model while neighboring counties will not.

Moving Forward, the State May Have Two Different Voting Models. As noted earlier, implementing SB 450 is at each county’s discretion. As a result, some counties may shift to the new model, while others may not. This could present challenges for voters who may be confused as to which system their county uses. Moreover, this will require the Secretary of State to oversee two different types of election models.

Roles and Responsibilities in Elections

Counties Best Positioned to Administer Elections. California governments form a complex web of overlapping boundaries of federal, state, and local government districts. Administering elections—that is, determining which residents are eligible to vote in a particular district election and facilitating that contest—is a function best suited for county government. Counties not only are familiar with their landscape of governments, but also the preferences of their residents. This local knowledge allows counties to organize elections in a manner consistent with local needs. Counties also are large enough to allow for economies of scale in voting—residents can vote for all of their elected officials using one ballot in a county administered election.

County Administration Yields Significant Benefits to the State. The state derives significant benefits from county administration of elections. These benefits include relieving the state from organizing thousands of local government elections as well as the elections for California’s members of Congress, the State Legislature, other statewide positions (like the Governor and Secretary of State), and statewide initiatives. In fact, in many elections, state issues make up the majority of the ballot. While the state reaps regular benefits from county elections administration, it only sporadically provides funding to counties for elections activities. Counties (and other local governments) generally bear elections’ costs without regular support from the state.

Effective Elections Administration an Important State Interest. The state has a clear interest in secure and timely elections. Moreover, some level of uniformity across counties in elections administration is valuable. Many legislative and other voting districts span multiple counties. Significant variation in elections procedures across counties could have implications for voter turnout, and by extension, election results.

State’s Financial Role in Elections. Due to the state’s challenging reimbursable mandates process, the Legislature does not often place new reimbursable requirements upon local governments. And when new requirements have been imposed, the Legislature typically has suspended them to avoid reimbursement to counties. Counties typically have continued to comply with the requirements (because they remain in state law), effectively paying for these state‑priority costs with local funds. In addition, the state has made a number of changes to elections administration (see Figure 3) which are not yet identified as reimbursable mandates but may impose new costs on counties. Given the importance of uniformity in elections, relying on the existing mandates system is ineffective. We recommend that the Legislature develop a new financial relationship between the state and county elections officials that allows the state to (1) direct statewide elections policy and (2) provide a reasonable and reliable level of financial support that reflects the benefits to the state of county elections administration. The pending implementation of SB 450 provides an opportunity for the Legislature to consider how to structure such a financial relationship to ensure consistency across counties as well as address other elections issues. In the next section, we provide options for how the state could provide such support.

State Funding of County Election Activities

Considerations for Providing Funding. In assessing the state’s role in funding county election activities, the Legislature will want to consider such key factors as existing—largely unfunded—state mandated responsibilities; any net costs that might result from implementing SB 450; and the major costs of buying and replacing voting machines. In addition, there may be other elections improvements the Legislature may want that go beyond current requirements. These could include timely vote counting, protecting elections systems, and keeping voter registration current. (The box below goes into more detail on some of these potential issues.) When determining the proper level of state support, the Legislature will want to consider all existing requirements as well as any other desired improvements to the elections system.

Other Elections Issues to Consider

Various Elections Issues Loom. While the Voter’s Choice Act (Chapter 832) SB 450 presents one new issue facing county elections officials, it is clear that California’s election system faces other significant issues. In designing a new financial relationship with counties, the Legislature could take into account the fiscal impacts of implementing any actions related to the issues discussed below. Counties may take different approaches to addressing these issues. In designing state support, the Legislature may not want to direct specific county activities, but rather focus on the desired outcome of those activities and incentivize counties accordingly.

- Timely Vote Counting. Due in large part to the widespread use of vote‑by‑mail and provisional ballots, counties now take weeks to finish counting ballots. Some voters are saying this undermines their confidence in the election process, in part because California counts ballots so much slower than other states do. Should the Legislature determine that swift determination of elections results is an important state goal, the Legislature could make receipt of funding conditional on counties demonstrating efforts to improve the swiftness of their tallies. Reducing the need for voters to use provisional ballots also could be a goal.

- Cybersecurity. The security of electronically stored voting information is paramount to maintaining confidence in elections. While the Secretary of State already sets standards for voting equipment used by counties, the Legislature could take further steps in designing financial support to encourage counties to continually upgrade and maintain their cybersecurity systems.

- Voter Registration. Maintaining up to date voter registration will be particularly important with conditional voter registration. VoteCal will facilitate county maintenance of the rolls, but the Legislature may want to consider what other steps counties should take to keep registrations up to date.

- Other Outcomes. State support also could be designed to encourage any particular outcomes or goals the Legislature may have with regard to elections administration. The Legislature could require the Secretary of State to gather information over time to see if counties make sufficient progress towards any such legislative priorities.

A Different Process for Funding. As discussed above, the process the state uses to achieve its local elections priorities—the mandates process—simply has not worked. We suggest the Legislature consider a different approach. In this new approach, the state and counties would share in the costs of elections, with state support addressing the costs associated with a range of activities directed by the Legislature. Only those counties choosing to take state funding would be required to perform the specified activities. For the new funding process to be effective, the Legislature would need to set the funding at such a level as to cover a reasonable portion of the associated costs so that counties would be willing to participate. As an example, the Legislature could model a new funding arrangement along the lines of the existing Education Mandates Block Grant. This program provides the same per‑pupil funding level to participating districts for various state educational requirements. School districts that participate in the block grant—currently 95 percent of districts—cannot claim reimbursement for mandate requirements covered by the block grant. If the Legislature were to establish a similar program for county election activities, the amount of funding provided would depend on the number of activities required and the share of counties the Legislature hoped would participate. Should the Legislature want elections to be more uniform across counties, the amount of funding would have to be set at such a level as to get most—if not all—counties to participate.

Create Block Grant for Ongoing Support. We recommend the Legislature structure ongoing support for elections as a block grant to participating counties. At minimum, we recommend the Legislature require participating counties to implement SB 450 by 2022. We also recommend the Legislature determine which existing mandates, if any, counties should perform and include those in the block grant. There are various options for how to distribute the block grant. For example, basing the grant amount on the number of registered voters could encourage counties to increase voter registration. As an example, were the state to provide $3 per eligible voter, the annual costs would be a bit less than $60 million if all counties participated. (Alternatively, the Legislature could base the grant amounts on the number of voters in recent elections.) The state also could consider using the ballot real estate model. That is, the state could reimburse counties for election costs based on the share of the ballot state issues comprise. Because state issues often are a large share of the ballot, the ballot real estate model could be more costly than the other options.

Consider One‑Time Support to Replace Counties Voting Systems. While not directly related to the ongoing elections issues discussed above, most counties voting equipment is quite old. Historically, the state has assisted counties in replacing their systems. In part, this may be because the state controls what voting equipment is available to counties to purchase. Should the Legislature wish to assist counties again, there are various ways to do so—including matching grants, short‑term loans, or bonds. The state could provide all of the necessary funds or only a portion. The Secretary of State estimates the total costs to replace counties’ voting equipment to be around $400 million.

Conclusion

Although the state receives significant benefit from county administration of elections in California, the state has provided sporadic financial support for elections administration. The existing process to provide state support for elections administration—the reimbursable mandates process—is ineffective. We recommend that the Legislature create a block grant to provide regular ongoing support to counties for Legislative priorities in elections. While the creation of an optional new voting model—SB 450—is an impetus for the Legislature to reconsider the state’s role in elections, we recommend taking a broader approach in considering elections issues addressed by a block grant.