LAO Contact

December 5, 2017

A Review of Caltrans’ Vehicle Insurance Costs

- Introduction

- Caltrans’ Vehicle Usage

- State Motor Vehicle Liability Self‑Insurance Program

- Caltrans’ Premiums

- Options to Contain Caltrans’ Premium Costs

- Conclusion

Summary

Caltrans’ Drivers Insured Through State Self‑Insurance Program. Like all other state departments owning vehicles, the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) is required to participate in the State Motor Vehicle Liability Self‑Insurance Program, administered by the Department of General Services (DGS). This program pays for injuries and damages caused by Caltrans drivers to other individuals and their property. Caltrans pays DGS a premium each year in order to be insured under the program.

Caltrans’ Premiums Have More Than Tripled Over Last Three Years. Specifically, Caltrans’ premiums increased from $4.2 million in 2014‑15 to $14.6 million in 2017‑18. (Despite this steep increase, the premium remains a tiny share of Caltrans’ overall budget of $12.2 billion.) To cover its premium cost increase for 2017‑18, Caltrans requested $5.5 million from the Legislature. The Legislature approved the requested funding but directed our office to (1) examine the causes of recent cost increases, and (2) present options for containing costs, such as a safe driver training program.

Premium Increases Are Almost Solely Due to Three Exceptionally Large Claims. The number of insurance claims against Caltrans has generally been trending down, which indicates that Caltrans’ premium costs are not increasing due to changes in the frequency of vehicle collisions. Rather, Caltrans’ premiums are increasing because the costs associated with its claims have gone up. In particular, three recent multimillion dollar claims (together totaling $19.5 million) appear to account for virtually all of the increased costs. These exceptionally large claims could be the result of the chance occurrence of a few extremely serious collisions, though DGS officials indicate they believe it could be part of a changing legal climate leading to higher liability costs for the state.

Options to Reduce Costs Include Establishing State Liability Limit. California law currently sets no limit on the amount of money for which the state can be held liable for vehicle collisions (though it does prohibit paying for punitive damages). California’s law on liability limits differs from many other states, with a recent study finding that at least two‑thirds of all states maintain liability limits. If the Legislature is concerned about the state costs associated with large liability payments, it could consider establishing a statutory limit, though this likely would result in some claimants receiving less than the full amount to pay for their injuries and economic damages. A second option to reduce costs is for Caltrans to take steps to bolster its driver training and vehicle safety practices, though the department already appears to be adhering to many best practices to minimize collisions.

Introduction

As part of the 2017‑18 budget, the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) requested $5.5 million (one time) to pay for a nearly two‑thirds increase in its vehicle liability insurance premiums. This insurance pays for damages caused by Caltrans drivers to other individuals and their property. The Legislature approved the requested funding but included language in the Supplemental Report of the 2017‑18 Budget Act directing our office to study the issue further. Specifically, the reporting language directs us to (1) examine the causes of recent cost increases, and (2) present options for containing costs, such as a safe driver training program. This report responds to the legislative reporting language.

The report contains four sections. First, we describe various aspects of Caltrans’ vehicle usage, including the types of vehicles the department owns and its policies for employees to drive them. Second, we provide an overview of the state’s vehicle liability self‑insurance program in which Caltrans participates. Third, we examine the recent increases in Caltrans’ insurance premiums. Lastly, we identify options to contain the department’s premium costs. In accordance with the reporting language, we focus on Caltrans’ vehicle liability insurance costs in the report, though some of our findings could have implications for vehicle insurance costs for other state departments as well as state liability for other incidents besides vehicle collisions.

Caltrans’ Vehicle Usage

Caltrans is responsible for planning, coordinating, and implementing the development and operation of the state’s transportation system. The department has about 19,000 employees, who work in 12 districts located throughout the state as well as headquarters in Sacramento. The department’s staff primarily work on maintaining and rehabilitating the state highway system, though some staff support programs dedicated to mass transit and other modes of transportation. Below, we provide an overview of various aspects of the department’s vehicle usage.

Employees Required to Drive. Many types of Caltrans employees must drive to fulfill their job requirements. Most notably, Caltrans’ maintenance staff must travel frequently among district offices and highway maintenance sites in order to perform activities such as clearing vegetation and filling potholes. These maintenance staff comprise about one‑third of Caltrans’ workforce. In addition, staff overseeing highway construction work and administrative staff sometimes must drive among highway sites and department offices.

Driver Training Requirements. Caltrans employees who drive must have a valid driver license appropriate to the type of vehicle they drive. For example, entry‑level maintenance workers are required to possess a Class C license, which permits them to drive vehicles such as light trucks and landscaping equipment. In addition, employees who drive typically are required to undergo at least one of the following types of training and testing:

- Defensive Driver Training. Caltrans employees who drive at least once per month are required every four years to take a defense driver training course run by the Department of General Services (DGS). The DGS offers both classroom and non‑classroom courses (such as online courses). In 2016‑17, about 3,300 Caltrans employees completed a DGS defensive driver training course. Slightly less than half completed a classroom course and the remainder completed a non‑classroom course.

- Maintenance Driver Training. Caltrans’ Division of Maintenance provides driver training for its field maintenance workers at its Maintenance Equipment Training Academy. New field maintenance workers are required to attend a ten‑day training course that includes both classroom instruction as well as “hands‑on” training in maintenance vehicles. The division also provides specialized courses for employees operating certain equipment, such as snow removal vehicles.

- Drug and Alcohol Testing. Caltrans employees who operate commercial vehicles in safety‑sensitive classifications are required under both federal and state regulations to submit to drug and alcohol testing. This includes pre‑employment testing, post‑accident testing, random testing, and reasonable suspicion testing.

Other Department Policies on Driving. Caltrans has a number of policies limiting vehicle usage by its employees. For instance, managers must give their approval for an employee to use a vehicle, and employees are prohibited from using state vehicles for personal use. Caltrans also has a number of vehicle safety policies related to activities such as securing loads on vehicles, using amber warning lights, and stopping and parking on state highways. Caltrans employees who are involved in a collision are required to record certain information about the collision and submit it to the department. After a collision, a supervisor reviews the information to determine whether the employee needs additional driver training. Caltrans can take personnel actions against an employee if the employee operates a vehicle negligently or does not comply with its policies on driving.

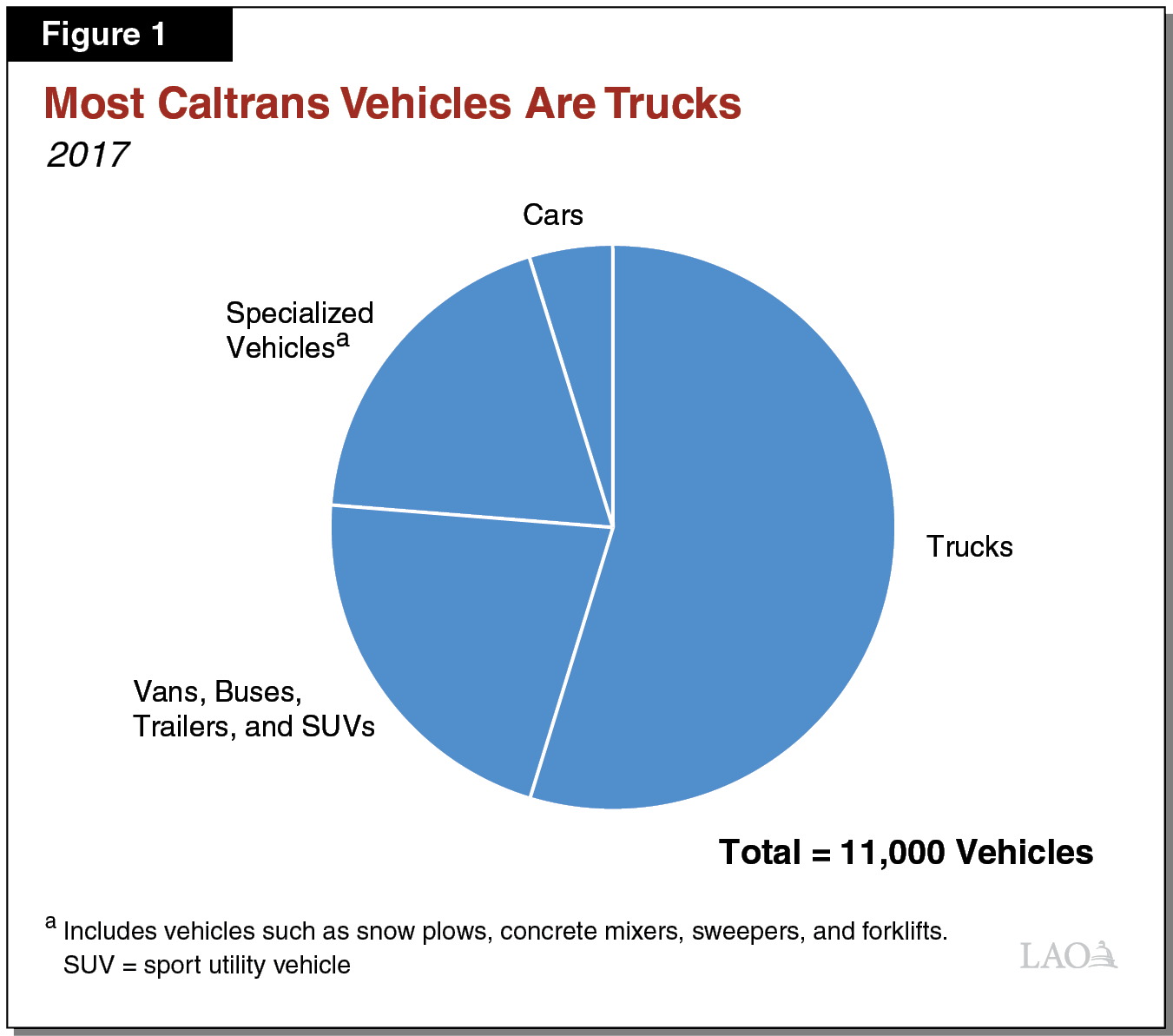

Vehicles Owned. Altogether, the department owns about 11,000 vehicles. Figure 1 summarizes this fleet by type of vehicle. The largest share of vehicles—about half—are various types of trucks (primarily pick‑up trucks). Caltrans’ vehicles are managed at the district level. To ensure vehicle safety, district employees are required to inspect light duty vehicles once per year and heavy duty vehicles every 90 days. Moreover, Caltrans indicates that it recently has begun installing back‑up cameras and other safety equipment in many of its vehicles. (Though most driving occurs in department‑owned vehicles, some driving also occurs in employees’ personal vehicles or rental vehicles.)

Miles Driven. In 2016, Caltrans employees drove department‑owned vehicles nearly 93 million miles. This means that on average each vehicle was driven about 8,300 miles. About half of the miles driven in 2016 were attributable to four districts covering the Bay Area, the greater Sacramento area, the lower portion of the Central Valley, and Los Angeles and Ventura counties. Caltrans’ headquarters accounts for about 2 percent of all miles traveled.

State Motor Vehicle Liability Self‑Insurance Program

In 1977, DGS implemented a self‑insurance program through which state departments set aside money each year to pay for anticipated vehicle liability expenses. All state departments owning vehicles, including Caltrans, are required to participate in this program. Currently, the program includes about 80 state departments. Figure 2 summarizes the main features of the State Motor Vehicle Liability Self‑Insurance Program, which we describe in more detail below.

Figure 2

Main Features of State Motor Vehicle Liability Self‑Insurance Program

|

|

|

|

Types of Coverage. The State Motor Vehicle Liability Self‑Insurance Program covers injuries and damages to other individuals and their property caused by state employees driving state vehicles. It also provides secondary liability coverage for state employees who drive a personal or rental vehicle on state business. The program does not cover damages to state vehicles or injuries to state employees. Instead, state departments pay for damages to their vehicles from within their budgets, while injured employees can seek damages through the state Worker’s Compensation Program.

Coverage Limits. California law currently sets no limit on the amount of money for which the state can be held liable for vehicle collisions, though it does prohibit paying for punitive damages. California’s law on liability limits differs from many other states. For example, at least two‑thirds of all states maintain liability limits. (Please see the nearby box for additional information on how California’s liability limits compare to other states.)

How Do California’s Liability Limits Compare to Other States?

The U.S. Constitution grants states “sovereign immunity” from lawsuits. This means all states can determine in their own laws the extent of their liability for actions by their employees. Below, we describe how California’s liability laws compare to other states with respect to (1) overall liability limits and (2) punitive damages.

Overall Limits. California is in a minority of states that sets no limit on its liability payments. At least 33 states set some type of statutory limit, according to a recent study by the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). (Though the study reported on liability limits generally, it appears they typically would apply in cases involving state vehicle collisions.) States with limits typically set one limit per claimant and a higher limit per incident. Some of these states also set higher limits for injuries and deaths as opposed to property damages. The value of the limits vary. For instance, while Florida pays up to $200,000 per claimant and $300,000 per incident, Pennsylvania pays up to $250,000 per claimant and $1 million per incident. Rather than set a fixed limit, some states require public agencies to purchase liability insurance and set the maximum payment at the amount covered under the policy.

Punitive Damages. California is in the majority of states that prohibit paying for punitive damages. According to the same NCSL study, at least 29 states explicitly prohibit making these types of payments.

Premium Calculations. DGS assesses a premium to each department in the State Motor Vehicle Liability Self‑Insurance Program. Premiums are primarily based on the cost of the previous five years of collision claims. DGS assesses an individualized premium to each department with more than 300 vehicles based on that department’s own claims history. For all other departments, DGS groups them together and assesses each the same premium based on their collective claims history. Currently, 23 departments are rated individually, while 57 departments are rated collectively. In addition to paying for claims, premiums also cover administrative expenses and provide a reserve for the insurance fund

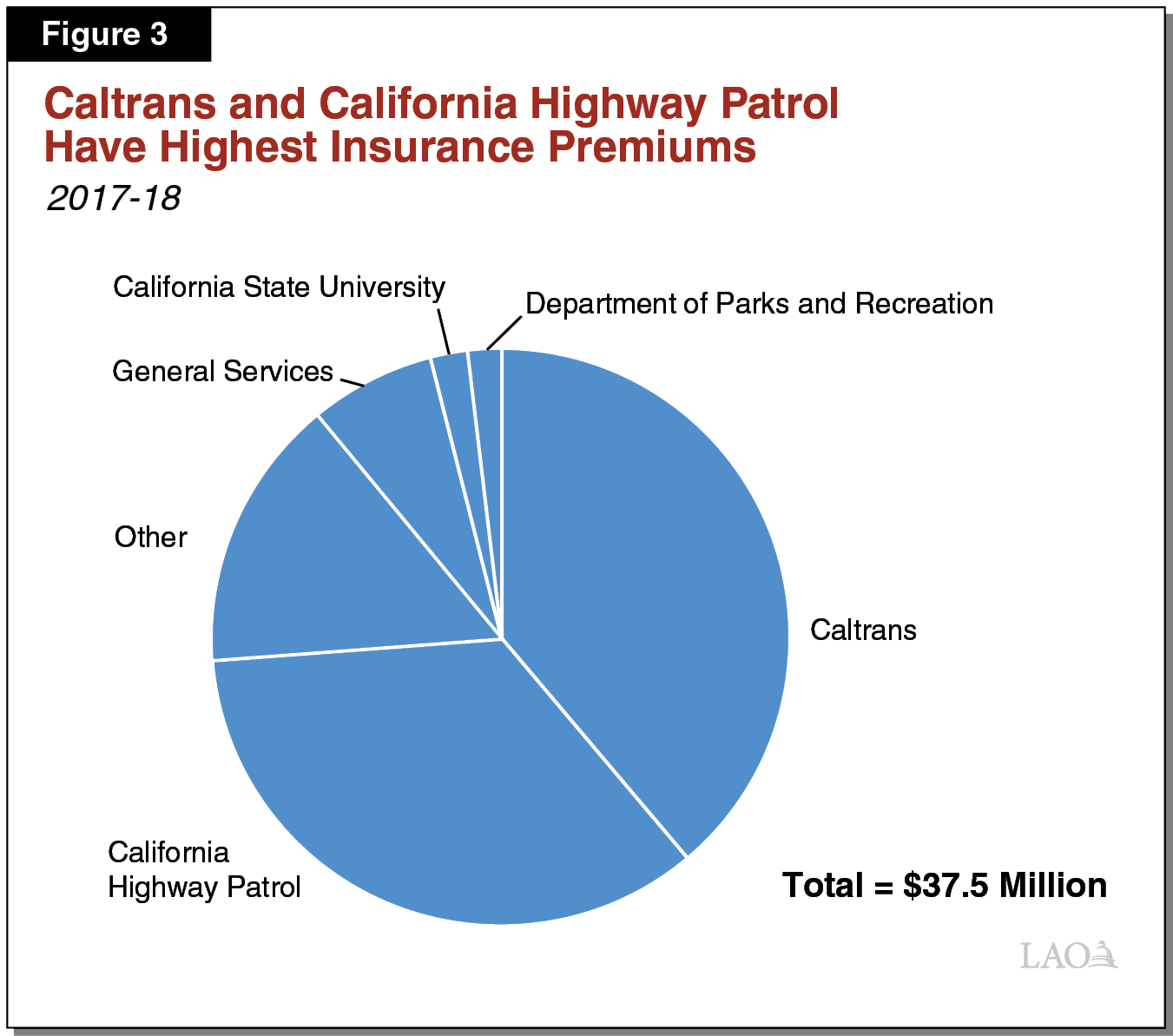

Premiums by Agency. For 2017‑18, DGS assessed a total of $37.5 million in premiums for all state departments. Figure 3 shows the share of total premiums by state department. Premiums vary by department due to differences in their recent collision history, which can be affected by the number of vehicles owned, the total miles driven, and the nature of the driving. Caltrans and the California Highway Patrol (CHP) have by far the highest premiums, because both departments have a large number of employees who frequently travel on state highways, often under hazardous conditions.

Administrative Costs. The DGS expects to spend $4.8 million in 2017‑18 to administer the State Motor Vehicle Liability Self‑Insurance Program. These administrative costs are allocated to each department’s premium based on its share of claims. The funds pay to support the 12.5 DGS positions responsible for investigating collisions, negotiating settlements, and calculating state department premiums. Caltrans, however, handles its own claims valued at less than $10,000. Program administration funds also pay for legal services for cases that go to court. The Department of Justice handles court cases for all state departments except Caltrans, which uses its own attorneys. DGS administrative costs have remained relatively stable recently, averaging about $4.2 million annually over the last five years.

Caltrans’ Premiums

Caltrans’ insurance premiums under the State Motor Vehicle Liability Self‑Insurance Program have increased significantly in recent years. Below, we examine trends in Caltrans’ premiums and collision claims, including reasons for the recent premium increases.

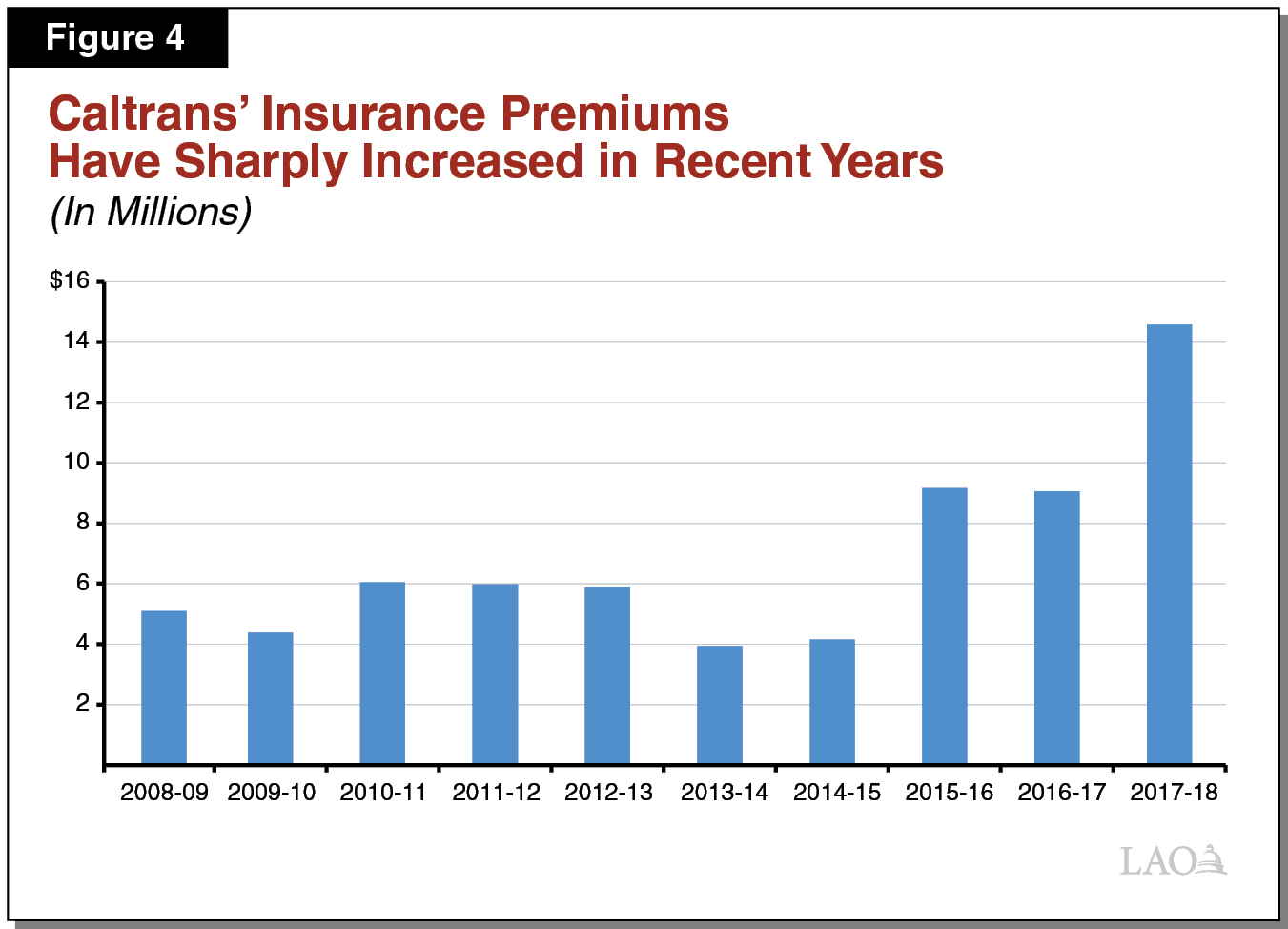

Premiums Have More Than Tripled Over Last Three Years. Figure 4 shows Caltrans’ premiums each year over the last decade. For the first seven years, premiums fluctuated around $5 million. Then, premiums nearly doubled in 2015‑16, and then increased by nearly two‑thirds in 2017‑18. (Despite these steep percentage increases, the premium remains a tiny share of Caltrans’ overall budget of $12.2 billion.) Caltrans is not alone among state departments experiencing steep premium increases—for example, CHP saw its premiums nearly double over the last three years. By comparison, motor vehicle insurance premiums charged by private companies nationally increased by around 20 percent over the past three years.

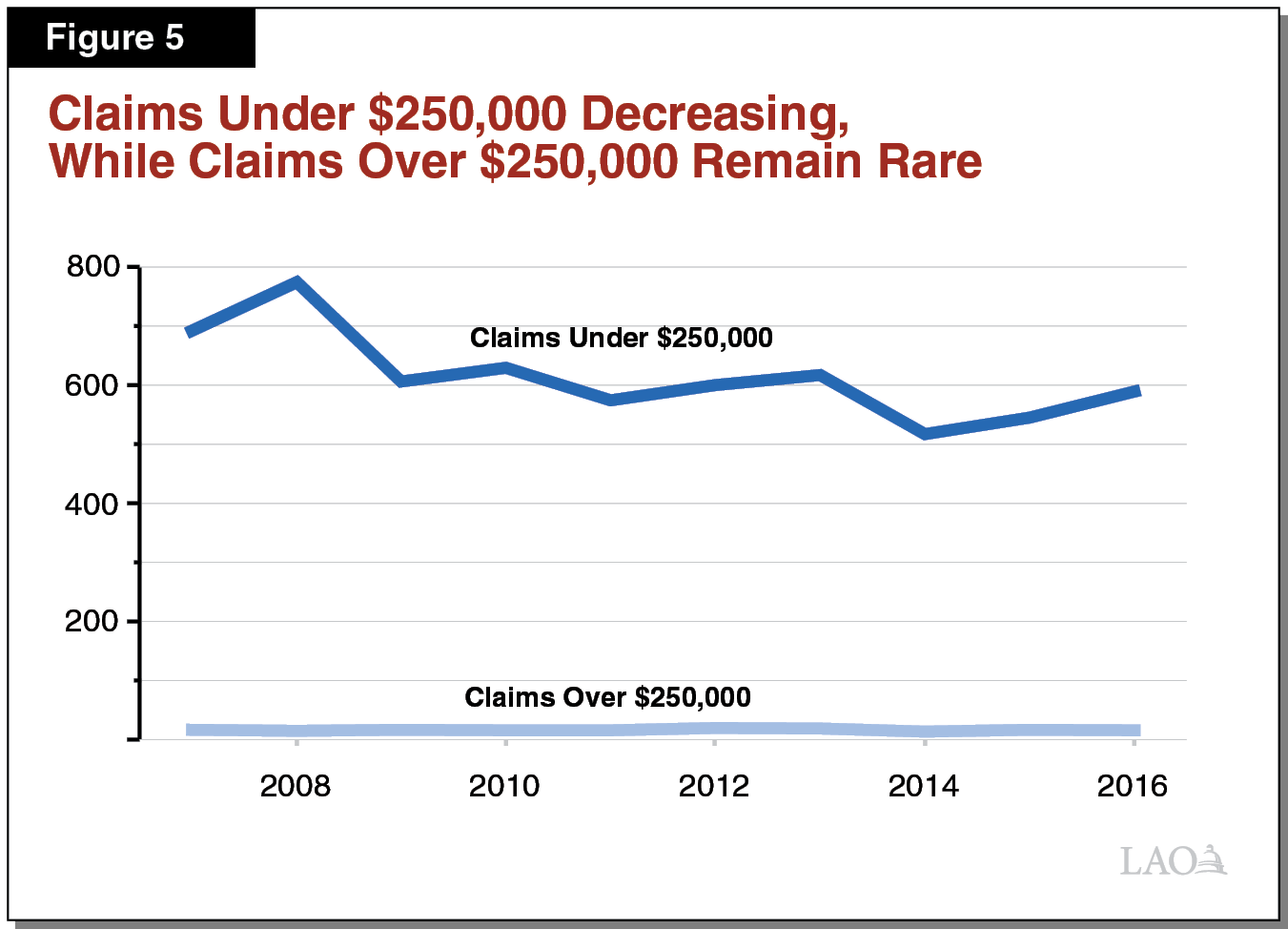

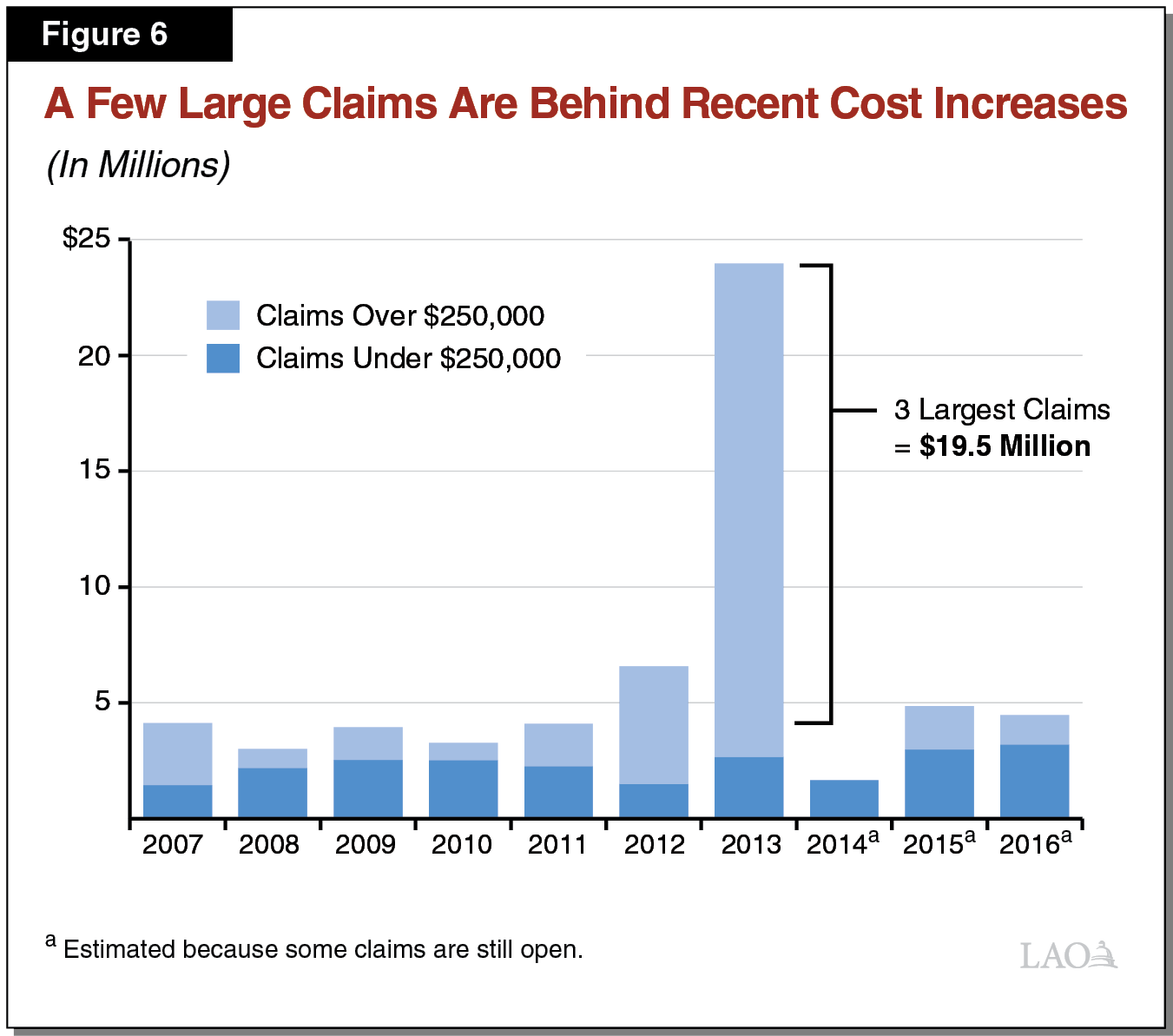

Premium Increases Are Not the Result of More Collisions. Figure 5 shows trends in the number of claims over the last decade, broken out by claims under $250,000 and claims over $250,000. The number of claims under $250,000 has generally been trending down somewhat. Claims over $250,000, which are much rarer, have remained essentially flat, with only a handful occurring each year. These trends indicate that Caltrans’ premium costs are not increasing due to changes in the frequency of vehicle collisions.

Rather, Premium Increases Are Almost Solely Due to Three Exceptionally Large Claims. Figure 6 shows the total cost of claims against Caltrans over the last decade. In most years, claims against Caltrans tend to hover around $4 million annually, with the costs for claims under $250,000 typically making up one‑half to three‑quarters of the total cost. However, as shown in the figure, the claims costs increased dramatically in 2013 due to a spike in costs for claims over $250,000. This spike mostly was the result of three exceptionally large claims costing $4.3 million, $6.8 million, and $8.5 million. Notably, these are the only claims over the last decade that exceed $2 million. The three claims involved serious injuries (such as traumatic brain injuries) and in one case a fatality. Though all three claims occurred in 2013, they affected Caltrans’ premiums starting a few years later because their full costs were not immediately recognized. For instance, the $4.3 million claim is still open and is the main reason for Caltrans’ premium increase in 2017‑18.

Reasons for Recent Exceptionally Large Claims Difficult to Determine. The recent exceptionally large claims could be the result of the chance occurrence of a few extremely serious collisions. Yet, DGS officials indicate that CHP and some other state departments also have experienced recent increases in high cost claims, making random chance seem somewhat less likely. One possible explanation suggested by DGS officials is that a changing legal climate has led to higher settlements and judgements against the state. In other words, claims that in the past might have cost several hundreds of thousands of dollars today are costing several millions of dollars. But determining how changes in legal practices by the state and plaintiffs’ attorneys are affecting costs is difficult because each case can have unique circumstances.

Options to Contain Caltrans’ Premium Costs

As indicated above, the significant increase in Caltrans’ premium costs is primarily due to three exceptionally large claims in recent years. Accordingly, we find that there are two main options to reduce Caltrans’ premium costs. First and foremost, the Legislature could establish a state liability limit to reduce payments for exceptionally large claims. Such a limit would apply to all state vehicle liability claims, not just those involving Caltrans vehicles. Second, Caltrans potentially could reduce vehicle collisions, which might also reduce the likelihood of severe collisions.

Establish State Liability Limit. The Legislature could consider establishing a statutory limit on the amount of damages for which the state can be held liable for collisions involving state vehicles. As discussed earlier, many other states have set such a limit. To determine an appropriate limit, the Legislature could consider the limits set by other states, the typical limits on private insurance policies, and the average costs for medical payments and lost wages in collisions resulting in severe injuries and fatalities. The Legislature also could consider setting different limits for personal injuries and deaths as opposed to property damages. As one example, had the state had a $1 million limit per collision over the last decade, Caltrans would have saved nearly $19 million and the limit only would have affected six out of over 6,000 claims. A limit, however, likely would result in some claimants receiving less than the full amount to pay for their injuries and economic damages. If the Legislature were to pursue this option to impose a limit, it also could consider whether to have the limit apply to other incidents involving state liability besides just vehicle collisions.

Additional Steps Caltrans Could Take to Potentially Reduce Collisions. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (part of the federal Department of Health and Human Services) recommends employers create a motor vehicle safety program to reduce collisions by taking several steps. These steps include:

- Reducing Driving. Federal studies have found a strong correlation between the number of vehicle miles traveled and the number of traffic fatalities. For this reason, the federal government recommends employers reduce driving as much as possible. In particular, it suggests employers use a “journey management system” that has formal mechanisms for assessing the need for travel, considering safer modes of travel besides driving (such as transit), considering videoconferencing in lieu of in‑person meetings, and combining driving trips whenever possible.

- Training Drivers. The federal government also recommends employers train new drivers as soon as possible, using behind‑the‑wheel training and training specific to different types of vehicles. Additionally, it recommends employers conduct routine on‑the‑road evaluations of drivers, review employee driving records annually, and use in‑vehicle monitoring systems to track driving performance.

- Making Vehicles Safer. The federal government further recommends employers use vehicles with high safety ratings. In particular, vehicles with advance safety features (such as lane departure warning systems, collision warning systems, and rear‑facing cameras) can help prevent collisions. Properly maintaining vehicles and conducting pre‑ and post‑trip vehicle inspections also can make driving safer.

As noted in the first section of this report, Caltrans already has various polices in place to limit driving, train drivers, and ensure vehicle safety. Nonetheless, some opportunities might exist to bolster these efforts. For instance, Caltrans potentially could further its driver training by making it more frequent or it could expedite replacing older vehicles with newer vehicles with advanced safety features. However, there are costs associated with taking these steps, and the benefits might be somewhat marginal, given Caltrans already has adopted many of the recommended best practices.

Conclusion

Caltrans’ vehicle liability insurance premiums have increased substantially over the last few years. The increase appears to be related to a handful of severe collisions for which Caltrans employees were at fault. These collisions resulted in extraordinarily large payments to the injured parties of several millions of dollars. At this time, however, it is not entirely clear whether these types of large payments will continue or escalate into the future, or whether they are the result of random chance. If the Legislature is concerned about the state costs associated with these large payments, it could consider establishing a statutory limit on liability payments. Many other states have set such limits to protect against large claims. Also, Caltrans could take steps to enhance its driver training and vehicle safety requirements, though the department already appears to be adhering to many best practices to minimize collisions.