Related Publications

LAO Contact

- California Community Colleges

- California Student Aid Commission

- Affordability and Financial Aid

- Apprenticeship Programs

- University of California

- California State University

February 15, 2018

The 2018-19 Budget

Higher Education Analysis

- Introduction

- Higher Education In Context

- University of California

- California State University

- California Community Colleges

- California Student Aid Commission

- Summary of Recommendations

Executive Summary

In this report, we analyze the Governor’s higher education budget proposals. Below, we highlight key messages from the report.

University of California

Legislature Faces Key University of California (UC) Budget Decisions. UC’s budget is affected by certain key cost drivers—most notably employee compensation, enrollment growth, its academic quality initiatives, and facility projects. The Legislature likely will want to consider supporting certain faculty and staff compensation increases in 2018‑19. We note, however, that UC faculty salaries remain very competitive relative to other public universities that conduct intensive research. Regarding enrollment growth, we believe UC’s funding redirection plan to support 1,500 additional students in 2018‑19 generally is consistent with legislative intent. We recommend enrollment decisions for 2019‑20 be made within the context of any broader discussion on UC eligibility. We recommend the Legislature consider additional funding for UC’s academic quality initiatives as lower priority. Though UC’s student‑to‑faculty ratio has increased the past several years, its student outcomes have continued to improve. Finally, several of UC’s proposed capital outlay projects lack sufficient justification. For example, four projects entail relatively large, expensive expansions despite UC providing no systemwide analysis of existing unused capacity. Whatever cost increases it ultimately supports for UC, we encourage the Legislature to think about how to share those costs between the state and nonfinancially needy students. (The state covers tuition for financially needy students.)

California State University

Legislature Faces Similar Key Budget Decisions for California State University (CSU). CSU has similar cost drivers as UC—most notably, faculty and staff compensation, enrollment growth, the Graduation Initiative, and capital outlay. The Legislature likely will want to consider supporting compensation increases given CSU already has entered into contracts increasing its costs. We note, however, that recent faculty salary increases at CSU have far exceeded inflation and are generally higher than what other state workers and UC faculty have received. As regards enrollment growth, we recommend the Legislature set an overall enrollment target based on certain demographic and policy considerations, including the state’s recent finding that CSU is drawing from beyond its Master Plan freshman eligibility pool (admitting from the top 41 percent rather than the top 33 percent of high school graduates). As regards the Graduation Initiative, we identify a number of opportunities CSU has to improve course availability and student success using existing resources, such that lower priority could be placed on providing additional funding for this initiative in 2018‑19. Finally, we identified several serious deficiencies with CSU’s capital outlay requests and recommend the Legislature direct CSU to compile standard information, including stronger justifications for each project, and resubmit its proposals by early March.

California Community Colleges

Recommend Allocating Some California Community College (CCC) Funding Based on Performance. The Governor’s largest proposed higher education augmentation this year relates to implementing a new CCC funding formula. Specifically, the Governor proposes moving away from the almost entirely enrollment‑based CCC funding model to one based on three components: (1) enrollment, (2) low‑income student counts, and (3) performance. Given the strong incentives under the existing funding model to focus on enrolling students rather than accelerating their time to degree, we recommend the Legislature allocate less CCC funding based on enrollment and some portion based on performance. We suggest at least 20 percent of funding be performance based to ensure sufficiently strong incentives to focus on student completion and time to degree. Regarding specific performance measures, we recommend using the Governor’s proposed performance measures but refining them to ensure districts continue to focus on serving low‑income students and still offer relatively expensive programs that serve student needs (such as certain career technical education programs). We also recommend the Legislature combine the proposed funding for low‑income students with existing categorical funding for those students and offer districts more flexibility in how they serve these students. Enhanced flexibility could be coupled with more transparent district budgets indicating how these students are supported. Finally, we recommend the Legislature task the Chancellor’s Office with monitoring the approval of new program awards, grade‑related data, and changes in the types of degrees and certificates awarded to ensure the new funding system is working as intended.

Recommend Taking Time to Evaluate New Online College Proposal. The Governor’s next largest higher education proposal is to create a new online college. Initially, the college is intended to focus on short‑term program pathways for working adults with no postsecondary credentials. We believe some elements of the Governor’s proposal could have statewide benefits—for example, by expanding course access. The proposal, however, fails to clearly identify the key reasons why the target student group is currently not seeking or receiving more education. Moreover, research suggests the target student group is not particularly well suited for online instruction. The administration also has not explained how a statewide college would be able to foster sufficient industry partnerships given the regional nature of many industries. We encourage the Legislature to take its time in reviewing the proposal and consider alternatives. In particular, the Legislature could consider ways to improve online and competency‑based education reforms within the existing CCC system.

Recommend More Holistic Approach to Covering Unmet Living Costs for Financially Needy CCC Students. The Governor proposes to consolidate two financial aid programs that cover some living costs for full‑time community college students. Though the proposal consolidates two programs, it makes the underlying award rules even more complex. Layered onto an already complex financial aid system, the proposal could further complicate the financial aid landscape for students and administrators. We recommend the Legislature take a more straightforward approach—consolidating all four existing state financial aid programs for financially needy CCC students into one program with one set of rules. Under the new program, financially needy students would receive a grant for living costs that covered all their unmet need after taking into account their expected family contribution, federal aid, and a reasonable work expectation. As covering all unmet need for all financially needy full‑time CCC students would cost about $500 million compared to the $287 million earmarked for such aid under the Governor’s budget, the Legislature would have to consider how to ration awards or repurpose other funding to cover the full estimated program cost.

Introduction

In this report, we analyze the Governor’s higher education budget proposals. We begin by providing an overview of higher education in California. In the next four sections, we analyze the Governor’s budget proposals for the three public higher education segments and the California Student Aid Commission. In each of these sections, we provide relevant background, describe and assess the proposals, and make associated recommendations. The final section of the report consists of a summary of our recommendations. In addition to this report, we have three other higher education budget briefs that analyze the Governor’s proposals for adult education, the California Education Learning Lab, and Hastings College of the Law. The “EdBudget” section of our website contains many higher education budget tables, some of which are not included in this report.

Higher Education In Context

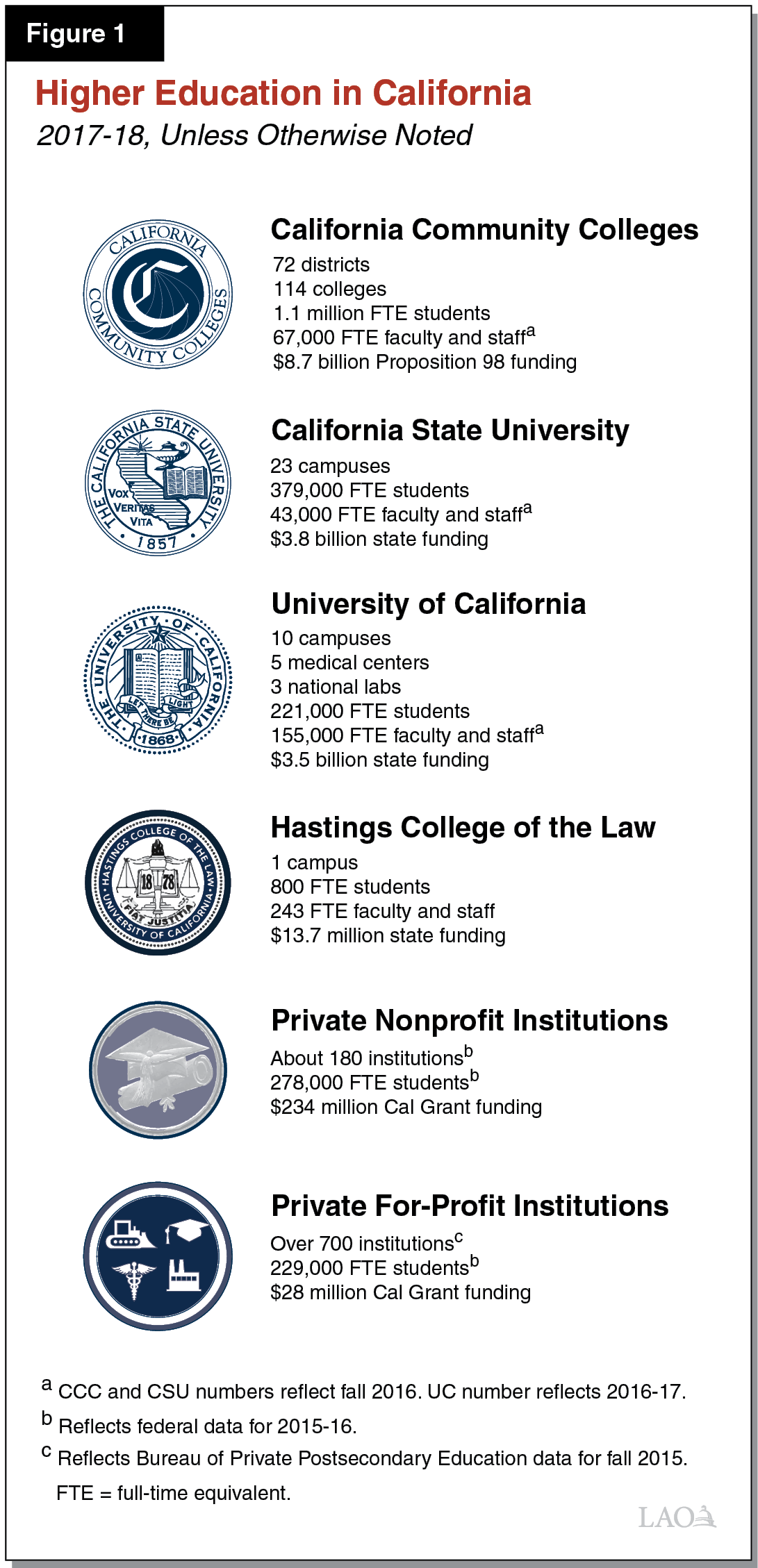

As Figure 1 shows, California has 114 California Community Colleges (CCC), 23 California State University (CSU) campuses, 10 University of California (UC) campuses, and 1 UC‑affiliated law school. Its private sector includes about 180 nonprofit colleges and universities and more than 700 for‑profit institutions. In this section, we focus primarily on the public sector—covering key issues relating to college eligibility, enrollment, and affordability.

Eligibility

Below, we provide background on the state’s eligibility policies, review the findings of a recent eligibility study funded by the state, and highlight issues for the Legislature to consider in light of these findings.

Background

Longstanding State Policies Determine Which Students Are Eligible to Attend Each Segment. In 1960, the state developed its Master Plan for Higher Education in California, which set forth eligibility policies for each of the public segments. Under the plan, all California residents may enroll in CCC. After completing lower‑division coursework with a minimum grade point average (GPA), CCC students may transfer to a public university. The Master Plan limits freshman admission to CSU and UC to the top one‑third and one‑eighth of high school graduates, respectively. Though never established in state law, these Master Plan policies have served as the basis for the universities’ admissions policies for the past six decades and influenced enrollment levels at all three public segments.

Policies Originally Intended to Tighten Freshman Access to Universities and Encourage Lower‑Division Instruction at CCC. Prior to the 1960 Master Plan, CSU and UC collectively drew from larger pools of high school graduates for freshman admission, with estimates of the proportion as high as 50 percent and 15 percent for CSU and UC respectively. Policymakers in 1960 elected to limit these proportions. In the original Master Plan report, policymakers cited five reasons for tightening freshman eligibility at the universities, including:

- Costs. Operating and capital outlay costs were lower at the community colleges than the universities. Costs were particularly high at UC because of its research mission. The authors of the Master Plan reasoned that focusing most enrollment growth at CCC would allow the state to support a more expansive higher education system.

- Access and Affordability. CCC was believed to be the most accessible of the three higher education segments to students, as that segment charges the lowest fees and generally serves local commuting students.

- Capacity. Several CSU and UC campuses at that time were believed to have reached enrollment levels that were “unmanageable.” Redirecting enrollment growth to CCC was seen as allowing the state to better control enrollment levels at those university campuses.

- Mission. Encouraging lower‑division enrollment at CCC was viewed as allowing CSU and UC to focus their resources on upper‑division and graduate instruction.

- Transfer Achievement. Data indicating that transfer students performed well at CSU and UC also was cited as a reason for focusing lower‑division coursework at CCC.

Transfer Eligibility Based on Grades Earned at CCC. In addition to setting policies for freshman eligibility, the Master Plan set expectations regarding transfer eligibility. Students at CCC who complete their lower‑division work and earn a minimum of a 2.0 GPA are eligible to attend CSU as upper division undergraduate students. To be eligible to attend UC as a transfers, students must earn a minimum of a 2.4 GPA in lower‑division CCC coursework.

Universities Are to Align Their Admission Policies With Their Respective Eligibility Pools. To draw from the top 33 percent and 12.5 percent of high school graduates, the university systems have historically structured their admission policies to require high school students to (1) complete college‑preparatory coursework and (2) attain a certain mix of high school GPA and scores on standardized aptitude tests (such as the SAT or ACT). We describe both requirements below:

- College Preparatory Coursework. Both university systems require students to complete a series of high school courses known as “A through G” (A‑G). The A‑G series includes courses in English, history, math, science, and other subjects. The share of high school graduates completing the A‑G series hovered around 35 percent from 2000‑01 through 2008‑09, before beginning to increase steadily over the next 7 years—reaching 45 percent in 2015‑16.

- Grades and Test Scores. Both university systems maintain an index of GPA and test scores that students must attain to be eligible for admission. Each index is devised such that a student with a lower GPA on A‑G courses must earn a higher test score to be eligible for admission. In order to draw from a smaller pool of students, UC’s index requires higher grades and test scores than CSU’s index.

UC Recently Developed Two Additional Freshman Admission Options. In addition to the statewide admission policy, students now have two other options to demonstrate eligibility at UC. Under the first of these options, known as “eligibility in the local context,” students in the top 9 percent of their high school are eligible to attend UC as freshmen—regardless of how they rank statewide. UC determines whether students are in the top 9 percent of their school based on high school GPA in A‑G courses, though students must still take the SAT or ACT. Under the second option, students who complete the A‑G series, have at least a 3.0 GPA, and take the SAT or ACT but do not meet either the statewide or the local admission criteria qualify for what is known as “comprehensive review.” A comprehensive review considers additional factors beyond overall grades and test scores, such as a student’s performance in their senior year, academic accomplishment in light of their life experiences, and special talents. Whereas students eligible under the statewide index or local context are guaranteed admission to UC, students qualifying for comprehensive review are not guaranteed admission. Instead, UC only views students who qualify for comprehensive review to be eligible once they are admitted. The combination of these three criteria (the statewide index, local context, and students admitted under comprehensive review) still are intended to draw from the top 12.5 percent of public high school graduates.

Eligible UC Students Not Ensured Access to Specific Campus or Major. While state policy is intended to guarantee eligible students admission to the UC system, it does not guarantee admission to students’ first‑choice campus or major. Eligible UC students who are not admitted to their campus of choice are referred to less selective campuses. Currently, Merced is the sole referral campus for freshmen. Merced and Riverside are referral campuses for transfer students.

Traditionally, CSU Attempts to Serve Eligible Students at Their Local Campus. In contrast to UC, high‑demand CSU campuses historically set “local admission areas” to determine which students are “local.” These campuses, in turn, guarantee admission for local students but increase admission standards for students from outside the local admission areas. This practice is intended to guarantee place‑bound students access to their nearby campus. Increasingly, more campuses are choosing to no longer guarantee admission to local students. CSU also does not have a systemwide referral policy for freshman applicants, though it does have a referral policy for transfer students who complete an associate degree for transfer. Due to some campuses not guaranteeing admission to local students and some eligible students not being referred to campuses with available slots, a proportion of eligible applicants (10 percent in 2016‑17) are not being admitted anywhere in the system. In response, the 2017‑18 Budget Act directed CSU to require all campuses to grant first priority admission to their local students and develop referral policies for students not admitted to the campus of their choice. (We provide more information regarding these efforts in the “CSU” section of this report.)

Universities’ Freshman Admission Criteria Periodically Assessed. To gauge whether the universities draw from their Master Plan eligibility pools, the state has funded what are known as “eligibility studies.” As part of these studies, CSU and UC admission counselors examine a sample of public high school transcripts and determine the number of students the universities would have admitted had these students applied. If the proportion of transcripts eligible for admission is significantly different from 33 percent and 12.5 percent for CSU and UC, respectively, the universities adjust their admission policies accordingly. For example, UC tightened its admission criteria after an eligibility study conducted in 2003 found it was drawing from the top 14.4 percent of public high school graduates. Since the 1960 Master Plan, the state has conducted eleven studies, with the last study conducted in 2015.

Findings From Recent Study

Results of Latest Study Recently Released. For the first time since 2007, the 2015‑16 budget provided funding for an eligibility study. The state provided $1 million to the Office of Planning and Research (OPR), which in turn contracted out the study to a private vendor. The vendor, which analyzed 77,000 transcripts from students graduating high school in 2015, completed the study in July 2017. We describe the results of the study below.

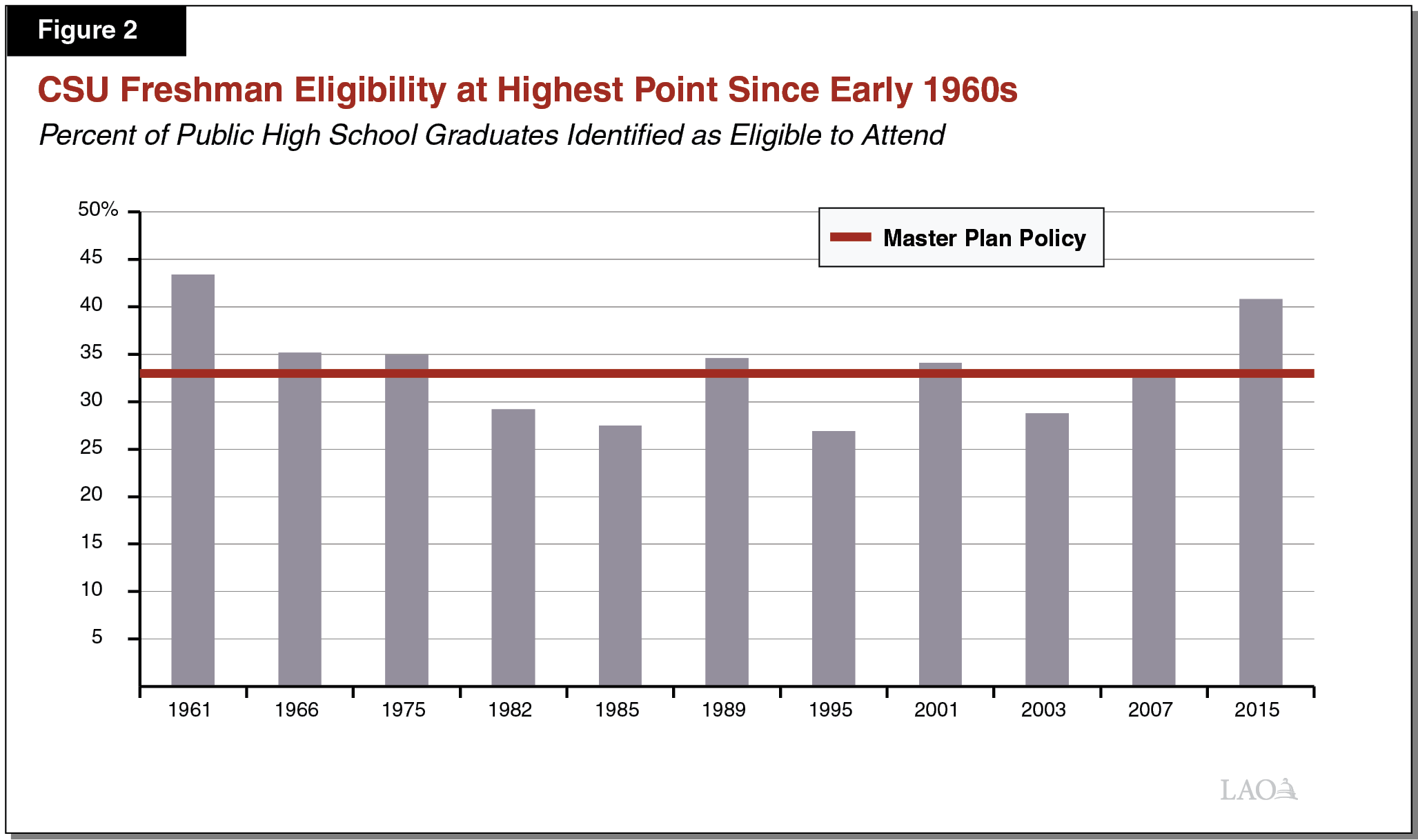

CSU Drawing From Notably Beyond Its Eligibility Pool. The study found that 41 percent of public high school graduates met CSU’s systemwide admission requirements in fall 2015. This proportion is notably higher than CSU’s expected eligibility pool of 33 percent. It also is the highest proportion of graduates CSU has drawn from since the 1960s (see Figure 2). Because CSU admission requirements have not changed since the last eligibility study in 2007, the increase since then is likely due to the greater share of high school graduates completing the A‑G series.

UC Might Be Drawing From Beyond Its Pool. For UC, the study found that 13.9 percent of public high school graduates met the university system’s admission requirements in 2015, with 11.2 percent of graduates eligible through the statewide or local criteria and an additional 2.7 percent of graduates admitted to UC under comprehensive review. While above UC’s expected 12.5 percent eligibility pool under the Master Plan, two factors complicate the study’s results. One is that UC’s results have a margin of error of 1.6 percentage points, creating a possible range between 12.3 percent to 15.5 percent. The other is that the eligibility study did not examine where students admitted under comprehensive review ranked statewide or locally, such that the state no longer knows the entire pool of students from which UC is drawing. Moreover, UC has increased the proportion of high school graduates admitted under comprehensive review. In fall 2016, UC admitted 4 percent of high school graduates under the comprehensive review policy.

Eligibility Increased for Students in Most Major Race and Ethnicity Groups. Figure 3 shows that eligibility rates are markedly higher for Asian students than other student groups. Eligibility rates for white students are somewhat higher than rates for Latino and black students. Since the last eligibility study in 2007, nearly all student groups have experienced increases in their eligibility rates. The eligibility rate for white students at UC, however, declined.

Figure 3

Eligibility Increased for Most Student Groups

Percent of High School Graduates Meeting Admission Requirements By Race and Ethnicity

|

2007 |

2015 |

Change From 2007 |

|

|

California State University |

|||

|

Asian |

50.9% |

64.0% |

13.1% |

|

White |

37.1 |

39.8 |

2.7 |

|

Latino |

22.5 |

31.9 |

9.4 |

|

Black |

24.0 |

30.0 |

6.0 |

|

All graduates |

32.7 |

40.8 |

8.1 |

|

University of California |

|||

|

Asian |

29.4% |

30.7% |

1.3% |

|

White |

14.6 |

11.9 |

‑2.7 |

|

Latino |

6.9 |

8.5 |

1.6 |

|

Black |

6.3 |

6.5 |

0.2 |

|

All graduates |

13.4 |

13.9 |

0.5 |

Issues for Consideration

Recent State Interest in Re‑examining Policies. Even prior to the findings of the recent eligibility study, the Legislature had expressed interest in reviewing the Master Plan eligibility policies. As part of the 2016‑17 budget, the state required all three segments to report on what would be entailed in notably increasing their production of certificate and degree holders by 2030. In its plan, UC estimated it would have to draw from around 17 percent to 20 percent of high school graduates to grow bachelor’s degrees to the desired level. CSU did not propose changes to its existing admission policies. Instead, it noted that many students who are not admitted to CSU as freshmen would eventually work their way to the university system through transfer from CCC. In addition to these reports, two state reviews of the 1960 Master Plan are currently underway: (1) a study of Master Plan polices and state workforce needs from OPR (due February 2018); and (2) a review by the Assembly Select Committee on the Master Plan for Higher Education in California, which held hearings in 2017 and plans to hold further hearings throughout 2018.

Key Trade‑Offs to Consider in Expanding Freshman Eligibility. In revisiting the state’s eligibility policies, one policy option would be to allow CSU and UC to continue drawing from larger eligibility pools than envisioned under the Master Plan. Expanding eligibility would permit more high school graduates to enroll directly at a public university. Advocates for this approach argue that the increase in A‑G completion rates indicates more students are better prepared for college‑level study and desire to attend CSU and UC as freshmen. Not every student who meets existing admission standards, however, is deemed ready for college‑level work, with remedial rates at CSU still notable—32 percent in fall 2017. (This proportion could drop in the coming years due to changes CSU is making both to how it assesses students’ college readiness and how it places students into first‑year courses.) The public universities also have higher instructional and capital costs than CCC. Moreover, the Legislature faces existing cost pressures in higher education, such as rising salary and benefit costs at each segment.

Key Trade‑Offs to Consider in Retaining Master Plan Eligibility Pools. In revisiting freshman eligibility pools, another policy option is to adhere to the Master Plan eligibility pools. This would mean CSU and UC would need to adopt stricter admissions requirements. This option would reduce enrollment pressures on CSU and UC, which would have the advantage of freeing up General Fund support for other cost pressures. As a result of tightening eligibility criteria, more students likely would be diverted to CCC, which has been experiencing declining enrollment in recent years. It also likely would increase the level of academic preparedness of entering freshman classes at CSU. Because this option would tighten admission requirements, however, many students may feel frustrated that they completed A‑G coursework but did not get admitted directly as freshmen to a public university.

Enrollment

Below, we discuss college‑related demographic trends, enrollment trends, and enrollment funding.

Demographic Trends

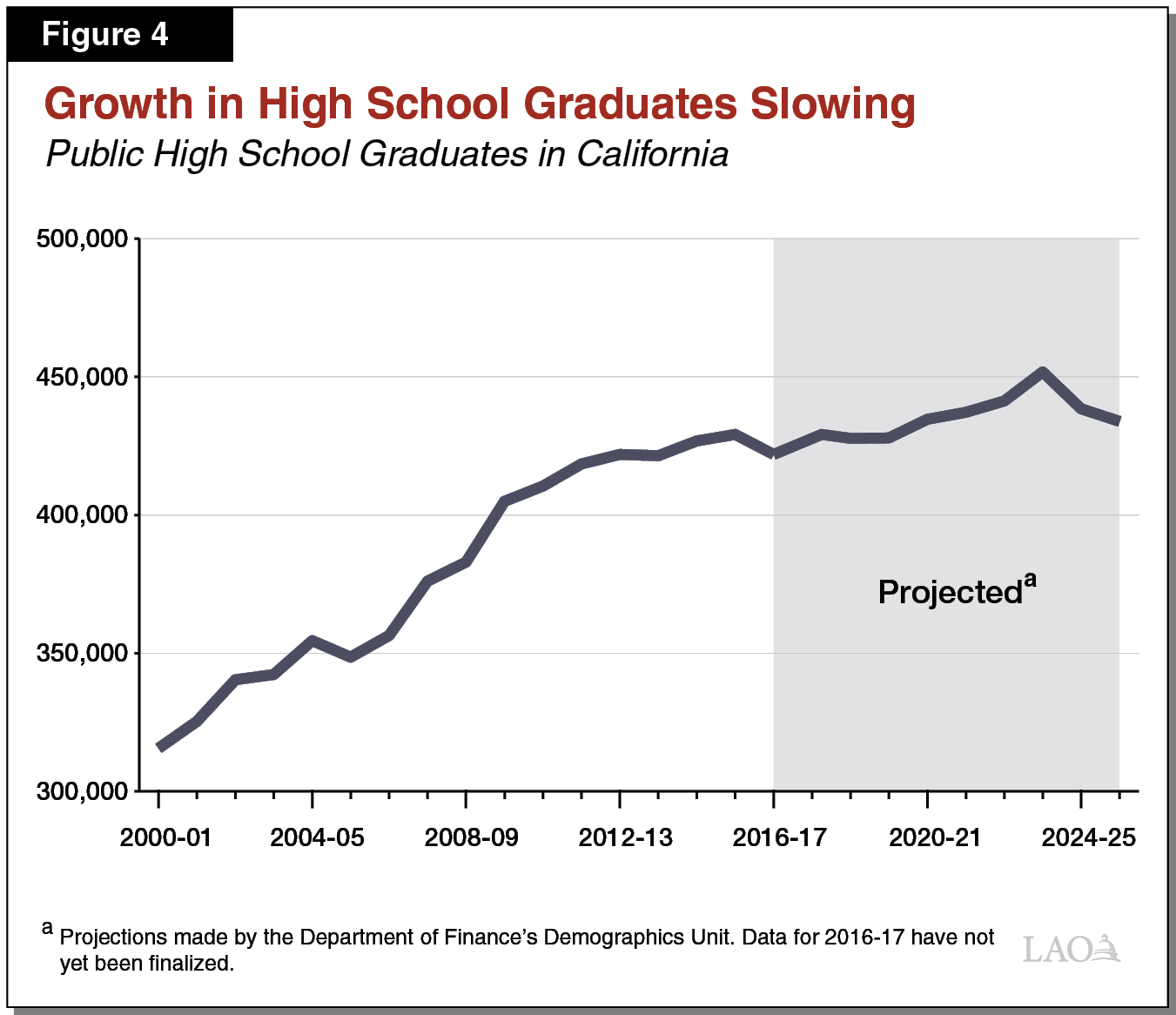

In 2016‑17, 422,000 Students in California Graduated From a Public High School. Enrollment demand for the three public segments is driven in part by changes in the number of high school graduates. Assuming no other changes, an increase in the number of California high school graduates causes a proportionate increase in college enrollment demand. More high school graduates can affect freshman enrollment immediately for all the segments. Increases in high school graduates also can have a future effect on transfer enrollment, as some entering community college students will work their way through the transfer process over the course of subsequent years.

Growth in High School Graduates Is Slowing. As Figure 4 shows, the number of high school graduates grew somewhat quickly from 2000‑01 through 2009‑10, with average annual growth over this period of 2.8 period. Since 2009‑10, growth has slowed considerably. Between 2009‑10 and 2016‑17, average annual growth was 0.6 percent. The state is expected to continue seeing slow growth in high school graduates throughout the next several years. The Department of Finance projects 0.3 percent average annual growth between 2016‑17 and 2025‑26.

Share of Californians Attending College Is Growing. In 2015, 47 percent of Californians between the age of 18 and 24 (the traditional college‑going age) reported attending college. This share has steadily increased since 2000. In that year, 35 percent of 18‑24 years olds in California reported attending college. In 2015, the rate for all 18‑24 year olds in the nation was 43 percent, with California’s rate ranking 9th highest among all states.

Enrollment Trends

California Has Larger Public Sector Compared to Rest of Nation. About three‑fourths of full‑time equivalent (FTE) enrollment in California is in the public higher education sector. The share in the public sector is somewhat higher in California than the rest of the nation (two‑thirds of FTE enrollment). California’s share of students in nonprofit colleges is lower than the rest of the nation (13 percent compared to 23 percent). The for‑profit sector enrolls similar shares of students in California and the rest of the nation (12 percent and 11 percent, respectively).

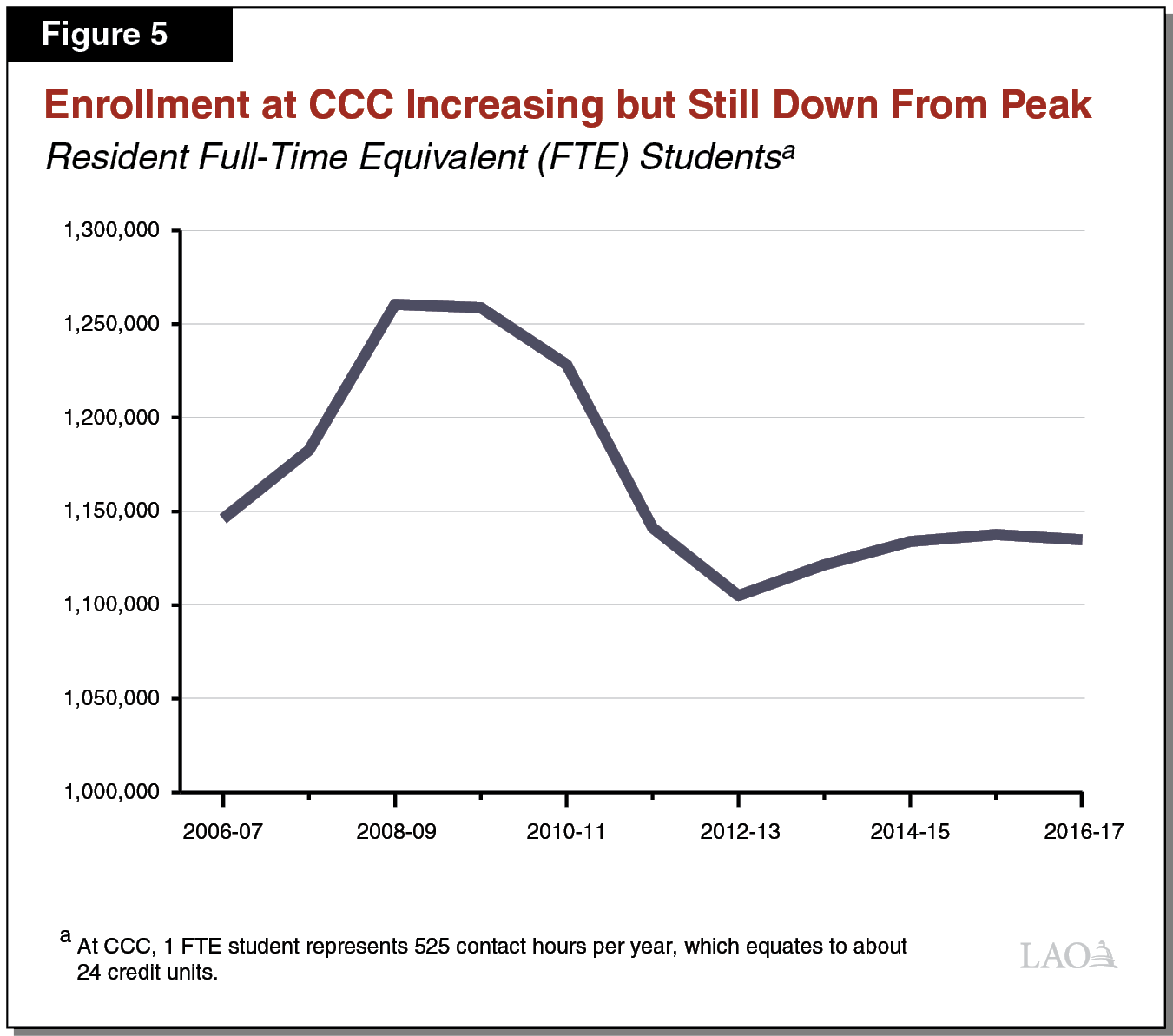

CCC Educates More Than 1 Million Resident FTE Students. CCC enrolls 62 percent of public sector undergraduate FTE students in California. This is higher than public sector enrollment in two‑year institutions in the rest of the nation (43 percent). California’s relatively larger community college system reflects the state’s eligibility policy, which encourages lower‑division enrollment at CCC. In 2016‑17, CCC educated 1.1 million FTE students (see Figure 5). This enrollment level is (0.7 percent) lower than the level in 2006‑07 and (10.7 percent) lower than the peak of CCC enrollment, which occurred in 2008‑09 (reaching almost 1.3 million FTE students). The decline in enrollment during the recession largely reflected reductions in state funding rather than declining enrollment demand. Enrollment demand is often highest at CCC during recessions as unemployment rates rise. California’s unemployment rate has been declining throughout the most recent economic expansion, likely a key reason why growth in CCC enrollment has been relatively slow in recent years. Largely due to its stronger link to the economic cycle, CCC enrollment is the most volatile among the three segments.

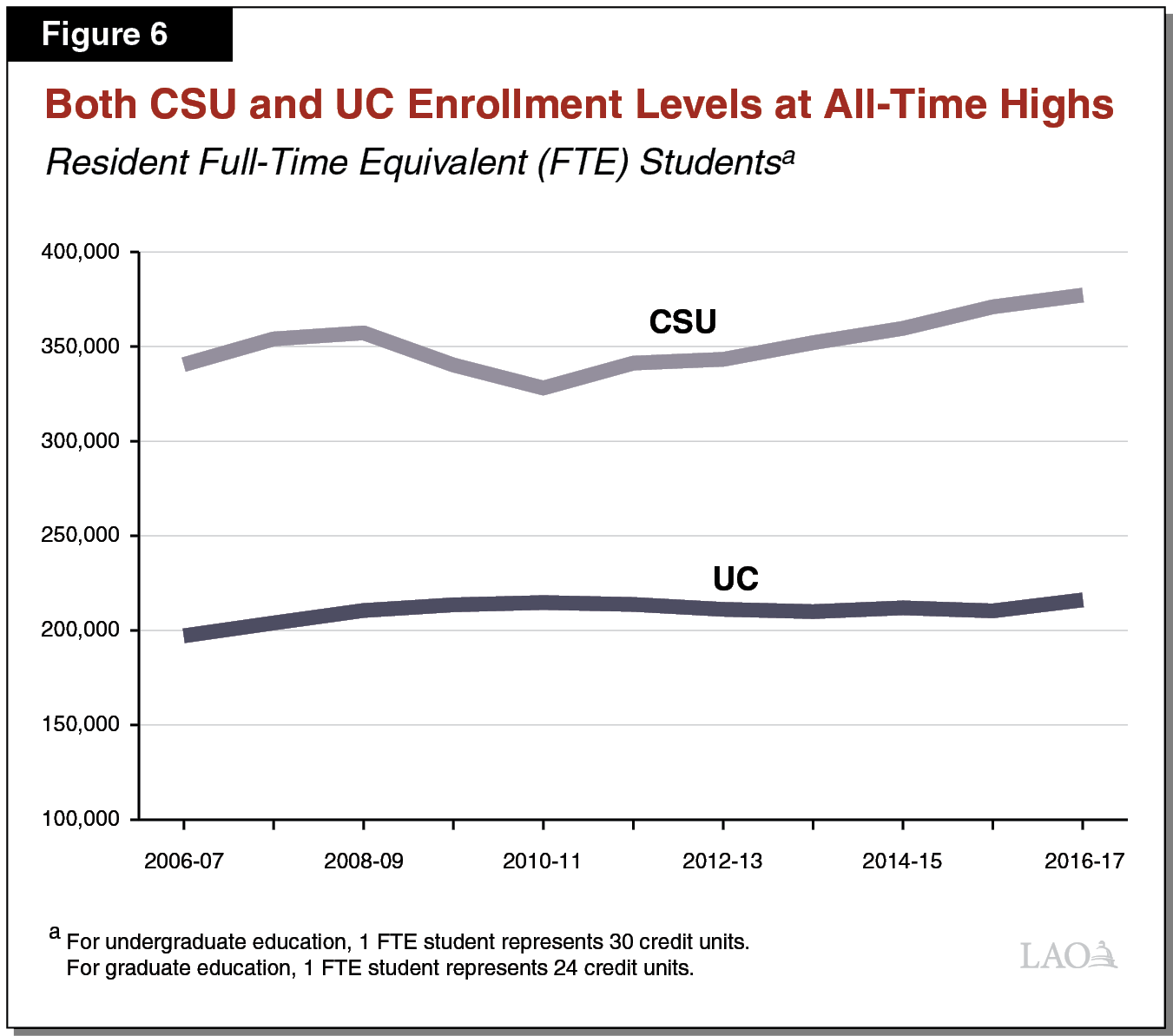

CSU and UC Resident Enrollment at All‑Time Highs. In 2016‑17, CSU educated 377,300 resident FTE students and UC educated 216,200 resident FTE students (see Figure 6). The 2016‑17 enrollment levels are 11 percent higher at CSU and 10 percent higher at UC compared to their respective levels in 2006‑07. Though resident enrollment at the universities is less volatile than at CCC, both CSU and UC experienced some enrollment decline during the past recession.

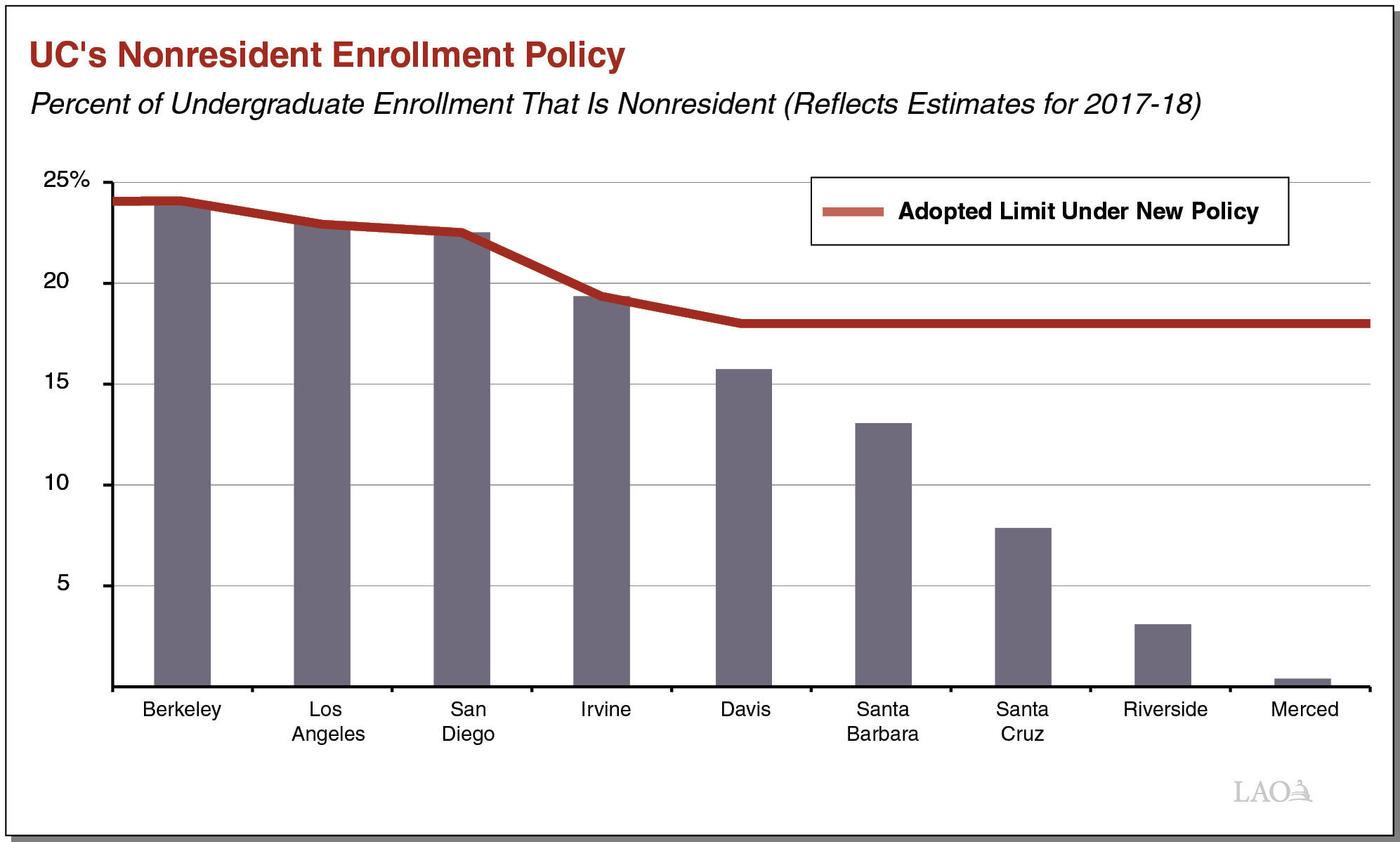

Nonresident Enrollment Remains Low at CCC and CSU but Has Grown Notably at UC. The proportion of nonresident students at CCC over the past ten years has been stable at 4 percent of total enrollment. At CSU, the share of nonresident students has grown only slightly—from 4 percent in 2005‑06 to 6 percent 2016‑17. Prior to the most recent recession, nonresident enrollment also was a small portion of enrollment at UC, comprising around 8 percent of all students. Nonresident enrollment at UC has grown notably since the start of the last recession, with the share in 2016‑17 reaching 17 percent. The share of nonresidents has grown especially quickly for undergraduate enrollment—from 4 percent in 2008‑09 to 15 percent in 2016‑17, increasing by 26,000 FTE students (148 percent) over the period.

Growth in Nonresidents at UC Leads to New UC Enrollment Policy. In response to concerns that the increase in nonresident enrollment was limiting space for eligible resident students, the state recently directed UC to adopt a policy to limit nonresident enrollment. UC adopted such a policy earlier this year, which we describe in the nearby box. In contrast to UC, no formal policy limits nonresident enrollment at CCC and CSU.

UC’s Nonresident Enrollment Policy

The 2016‑17 budget included provisional language requiring UC to adopt a policy limiting nonresident enrollment as a condition of receiving enrollment growth funding that year. In May 2017, the UC Regents finalized the new policy. The policy sets an 18 percent cap (or target) for nonresident undergraduate enrollment at five campuses and sets higher campus‑specific caps for the remaining four campuses (see the figure below). At these campuses, the caps are linked to their 2017‑18 nonresident enrollment shares. Effectively, the new policy gives five campuses an opportunity to increase their shares of nonresident enrollment, while limiting further growth in nonresident enrollment at the four campuses with the highest existing shares.

Graduate Students Account for About 1 in 5 Students at UC and 1 in 10 Students at CSU. In 2016‑17, UC enrolled 50,600 graduate students (19 percent of its total enrollment) and CSU enrolled 40,700 graduate students (10 percent of its total enrollment). These shares are somewhat lower than the shares 15 years ago. In 2000‑01, graduate students comprised 23 percent of total enrollment at UC and 17 percent at CSU. Among UC graduate students today, about 50 percent are doctoral students, about 40 percent are enrolled in a master’s program, and about 10 percent are enrolled in a graduate professional program (such as medicine, law, and business). At CSU, about 75 percent of graduate students are enrolled in a master’s program and 25 percent are enrolled in a postbaccalaureate program (mostly teacher training programs). Postbaccaularate enrollment in 2016‑17 is less than one‑third of what it was 15 years ago.

Science Majors and Degrees Trending Upward Over Past 15 Years. This upward trend is most notable at UC, where the share of undergraduates enrolled in a science, technology, engineering, or mathematics (STEM) major increased from 30 percent in fall 2000 to 41 percent in fall 2016. While increasing at CSU too, the trend has been more gradual. In fall 2016, 23 percent of undergraduate students enrolled in a STEM major, compared to 20 percent in fall 2000. An even greater share of graduate students are enrolled in a STEM field—about 60 percent of UC doctoral students and about 26 percent of CSU master’s students in fall 2016.

Private Sector Enrollment Below Peak Levels. Private sector enrollment peaked in California in 2010‑11, reaching around 314,000 students in the for‑profit sector and 281,000 students in the nonprofit sector. Since that time, enrollment has declined notably at the for‑profit sector and slightly at the nonprofit sector. In 2014‑15, enrollment in the for‑profit sector was 18 percent lower than its peak, with enrollment in the nonprofit sector down 1.9 percent. Of the two sectors, the for‑profit sector has a larger share of its enrollment in two‑year institutions. Among nonprofit colleges, most enrollment (95 percent) is in four‑year institutions. Both sectors also have notable graduate student enrollment (10 percent of for‑profit enrollment and 36 percent of nonprofit enrollment).

Enrollment Funding

Traditionally, State Sets Enrollment Target for Each Segment. Under the traditional approach to funding enrollment, the state first considers the eligibility, demographic, and enrollment factors discussed earlier and sets a target for each segment. Over the past few decades, the state typically has set one overall enrollment target for each segment rather than separate targets for certain types of students (such undergraduate and graduate students or students in the humanities and sciences). If the state increases a segment’s overall enrollment target, then the state decides how much associated funding to provide.

State Funds CCC Enrollment Growth at Per‑Student Rate. State law requires that the CCC Board of Governor’s annual budget request for enrollment growth be based, at a minimum, on changes in the adult population and excess unemployment (defined as an unemployment rate higher than 5 percent). The Governor and Legislature do not have to approve enrollment growth at the requested level. Their decisions tend to reflect the state’s budget condition. Once the enrollment growth level is set, the state calculates how much funding to provide CCC based on a going per‑student funding rate. That rate ($5,151 in 2017‑18) effectively is based on the average cost of serving an additional CCC student. The CCC distributes enrollment growth funding among districts based upon a set of statutory factors, including each district’s prior‑year enrollment level as well as various socioeconomic factors (such as the local unemployment level). If a district does not meet its target, it retains associated enrollment funding for one year, but then the unearned funding is reverted. A district, however, has up to three years to earn back the funding if it can increase its enrollment. If the overall CCC system does not meet its target, the state immediately repurposes the funds for other college (or school) priorities.

CSU and UC Enrollment Growth Traditionally Funded Based on Marginal Cost Formula. In the case of the universities, the state makes a determination each year on how much enrollment to fund and gives the segments flexibility to set enrollment targets for each campus. When providing funding for enrollment growth, the state for decades used a “marginal cost” formula that estimated the cost of admitting one additional student. The most recently used formula assumed that the universities would hire a new professor (at the average salary of newly hired faculty) for every 19 additional students enrolled. In addition, the formula included the average cost per student for faculty benefits, academic and instructional support, student services, instructional equipment, and operations and maintenance of physical infrastructure. The marginal cost formula was based on the cost of all enrollment (undergraduate and graduate students and all academic disciplines excluding health sciences). After calculating the total marginal cost per student, state and student shares were calculated. In 2017‑18, CSU estimated its total marginal cost per student was $10,649, with a state share of $8,041. UC estimated its total marginal cost per student was $18,146, with a state share of $10,097. If the segments did not meet the enrollment target specified in the budget within a certain margin, then historically an equivalent portion of the associated enrollment growth funding was reverted.

Funding Enrollment Growth at CSU and UC Has Become Less Transparent Over Past Several Years. Though the state traditionally has set enrollment targets and used the marginal cost funding formula to determine how much associated enrollment growth funding to provide CSU and UC, it has not regularly used this process since 2008. The state began omitting enrollment targets in the 2008‑09 budget, when it entered the last recession and reduced base funding for CSU and UC. The purpose was to provide CSU and UC flexibility to manage state funding reductions. Though the state resumed some of its enrollment budgeting practices since that time, it has not consistently set enrollment targets and used the marginal cost formula to determine associated state funding.

New Budgetary Rules Emerging for UC. In recent years, the state has approached UC enrollment targets and funding in a few new ways:

- Setting Out‑Year Targets. In order to give UC more time to respond to legislative direction, the 2015‑16 budget set enrollment goals for UC for the 2016‑17 academic year, one year after the budget year. The state has since continued this practice. For example, the 2017‑18 budget set enrollment targets for the 2018‑19 academic year.

- Expecting UC to Cover Some of the Associated Cost From New Sources. In 2015‑16 and 2016‑17, the state budget provided UC with less enrollment growth funding than what would have been generated under the traditional marginal cost formula. The 2017‑18 budget did not provide any new funding for enrollment growth. The change in funding practices were made with the expectation that UC find funding through alternative sources and redirected savings from certain cost reductions.

- Making Funding Conditional. In years where funding was provided for enrollment growth (the 2015‑16 and 2016‑17 budgets), the state budget required UC to demonstrate to the Department of Finance that it was on track to meet its enrollment target by May of the following year. If UC was on track, it received its enrollment funding. In both years, UC ultimately received funding.

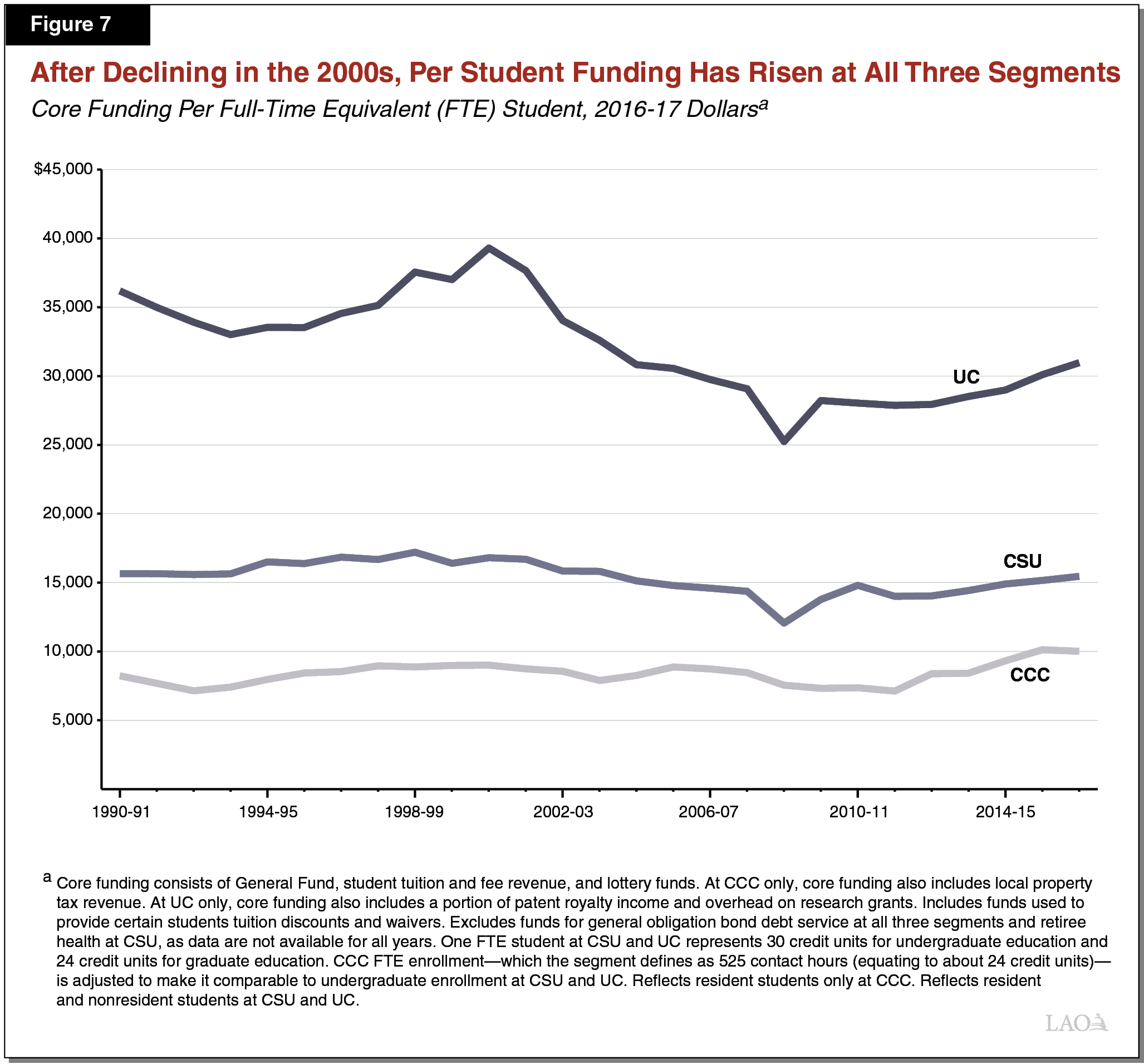

Core Funding Per Student Increasing in Recent Years. As Figure 7 shows, total core funding per student is highest at UC ($30,975), lower at CSU ($15,457), and lowest at CCC ($10,014). CCC’s inflation‑adjusted per‑student amount is down slightly from the system’s peak level, reached in 2015‑16 ($10,125). At the universities, inflation‑adjusted per‑student funding has been increasing in recent years but remains below peak levels (of $39,299 at UC in 2000‑01 and $17,205 at CSU in 1998‑99). Since 1990‑91, state and local funds have comprised around 95 percent of core funds at CCC. At the universities the share of state funding has declined, from around 80 percent in 2000‑01 at both segments to around 60 percent at CSU and 50 percent at UC in recent years.

Affordability

Below, we provide information about student tuition, living expenses, and financial aid.

Tuition

State Currently Does Not Have a Tuition Policy. A tuition policy establishes how tuition levels are to be adjusted over time. Depending on the policy, the tuition charge either explicitly or implicitly represents the share of education costs to be borne by full fee‑paying students and the state. The state share of education costs consists of the subsidy it provides directly to each of the higher education segments as well as the financial aid it provides to students for covering tuition. Though California had a tuition policy for several years during the late 1980s and early 1990s, it has not had a tuition policy the last few decades.

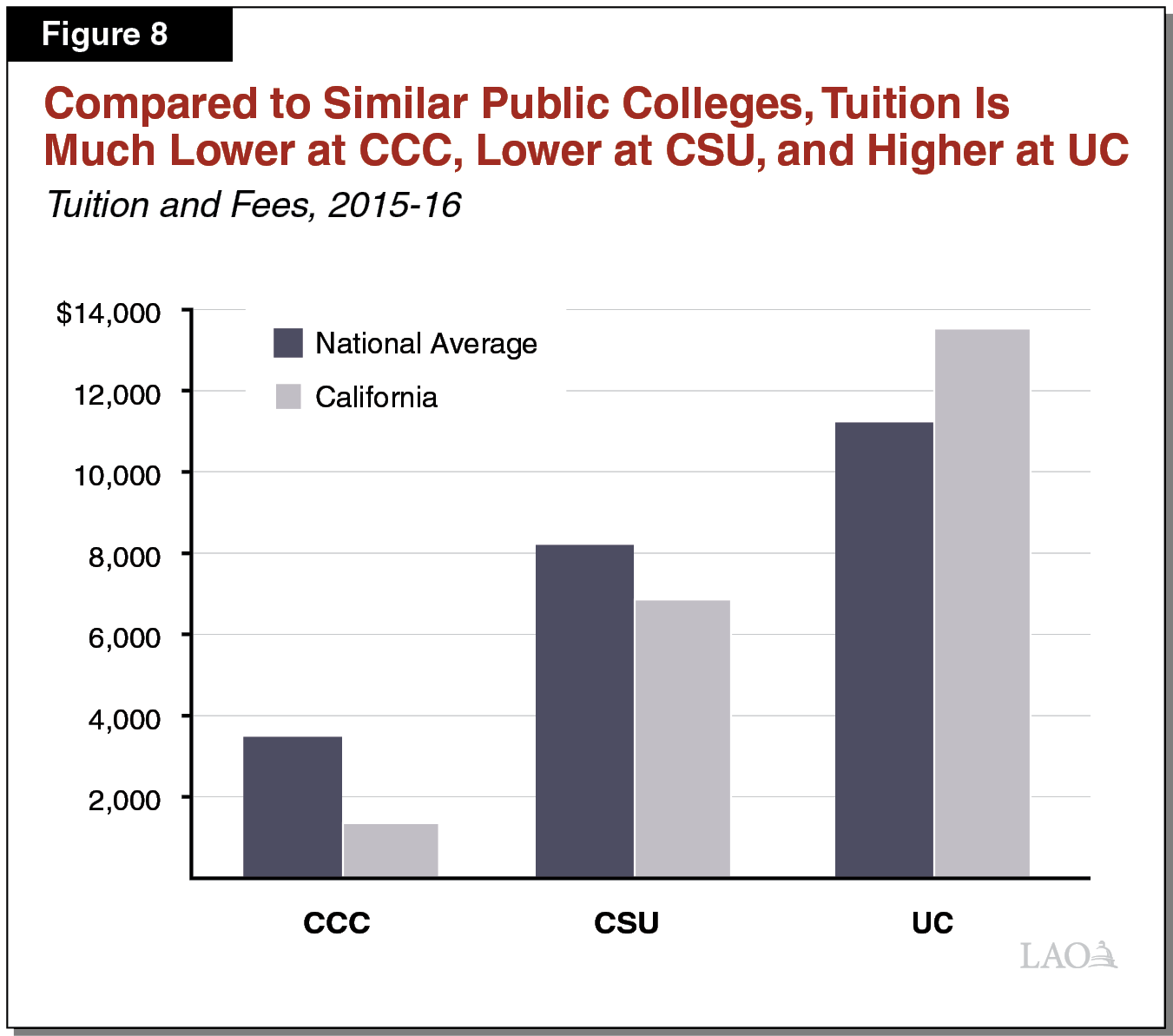

Tuition at Public Institutions Is Lower in California Than Other States. For full‑time undergraduate students, UC currently charges $12,630, CSU charges $5,742, and CCC charges $1,380 ($46 per unit for 30 units). Campuses in each system also charge fees for specific services, such as student health services. Compared to the average fee level of similar public universities in other states, UC’s tuition and fees tend to be notably higher, whereas CSU’s tend to be notably lower (see Figure 8). CCC tuition and fees are the lowest in the country compared to other public community colleges—about one‑third of the national average.

Large Share of Education Funding Comes From the State. At UC, we estimate that the state provides 62 percent of all core education funding, with tuition revenue from resident students comprising 17 percent, and other fund sources (primarily nonresident tuition revenue and endowment income) covering 21 percent. At CSU, we estimate that the state provides 68 percent of all core education funding, with resident tuition revenue comprising 26 percent, and nonresident tuition revenue covering 6 percent. At CCC, we estimate state and local revenue comprises 95 percent of core funding, with student fee revenue covering 5 percent. (These aggregate shares are not a meaningful indicator of the share covered by any particular student. A financially needy student, for example, pays no tuition at any of the public segments.)

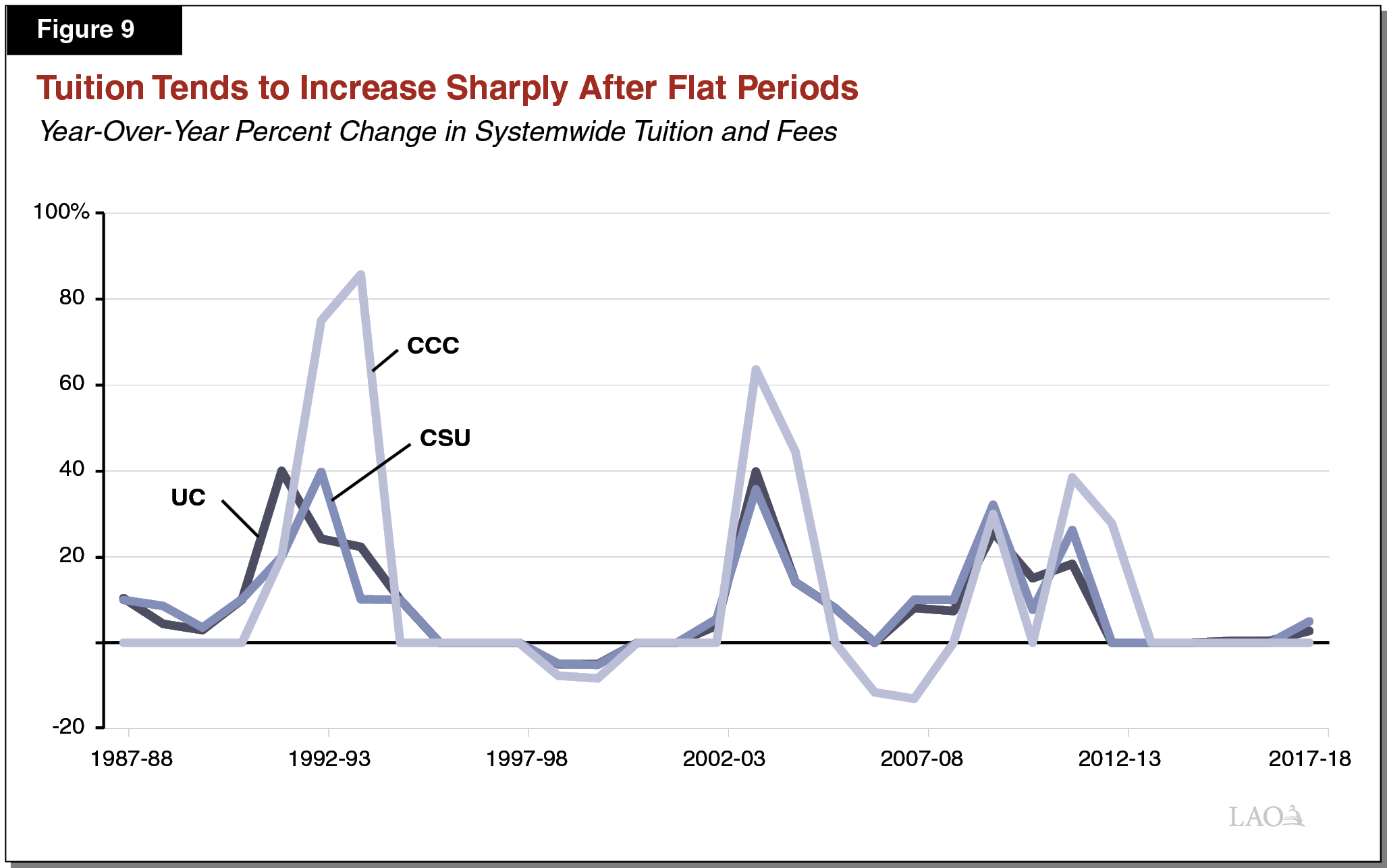

Tuition and Fees Tend to Be Volatile. Though the state provides a large share of core education funding, the state contribution varies over time, tending to increase during economic expansions and retract during recessions. Tuition and fee levels in California tend to be affected by such fluctuations. As Figure 9 shows, tuition and fee levels have had long flat periods generally corresponding to years of economic growth and increasing state contributions. These periods tend to be followed by steep increases generally corresponding to economic slowdowns or recessions, when state contributions tend to fall. Somewhat exceptional to these overall trends, in 2017‑18—a time of continued economic growth—UC increased its tuition and fees by about 3 percent and CSU increased its tuition and fees by about 5 percent. These increases came after six years of flat tuition charges at the two segments.

Living Expenses

Total Cost of Attendance Includes Both Tuition and Living Expenses. Apart from tuition (that is, direct education costs), students incur other costs to attend college, including housing, food, books and supplies, transportation, and personal expenses.

Estimated Living Expenses Vary Based on Several Factors. Each segment has its own method for estimating students’ living costs. Within each segment, costs vary across campuses, as some expenses (such as housing) vary across the state. Living costs also vary depending on whether a student lives on campus, off campus not with family, or off campus with family. Figure 10 shows how average living expenses at UC vary by living arrangement. The UC system estimates students living with family face by far the lowest costs—about 30 percent lower than other students living off campus and almost 50 percent lower than students living on campus.

Figure 10

Estimated Living Expenses Vary by Student Living Arrangement

University of California, 2016‑17a

|

On Campus |

Off Campus |

Off Campus With Family |

|

|

Rent and food |

$14,520 |

$9,769 |

$4,861 |

|

Health careb |

2,312 |

2,316 |

1,946 |

|

Transportation |

699 |

1,273 |

1,686 |

|

Otherc |

1,732 |

1,916 |

2,068 |

|

Totals |

$19,263 |

$15,274 |

$10,561 |

|

aReflects average costs across the system’s ten general campuses. bPrimarily reflects health insurance costs. Students insured through family are not required to purchase insurance. cIncludes expenses for clothing, entertainment, and recreation. |

|||

Living Expenses Higher in California Than in Other States. Compared to similar public universities in other states, living expenses for students attending CCC, CSU, and UC tend to be higher. Specifically, for students living off campus not with family, living expenses are on average about 20 percent higher in California. For students living on campus, costs are on average about 30 percent higher in California.

Financial Aid

Various Types of Financial Aid Help Students. Figure 11 shows the main financial aid programs available to undergraduates attending one of California’s public higher education segments. The aid comes from many sources—the federal government, state government, colleges, and private entities, such as philanthropic groups. Financial aid includes gift aid (grants, scholarships, and tuition waivers that students do not have to pay back); loans (that students must repay); federal tax benefits (that can reduce income tax payments or provide a tax refund); and subsidized work‑study programs (that make it more attractive for employers to hire students). Financial aid may be need based (for students who otherwise might be unable to afford college) or nonneed based (typically scholarships based on academic merit, athletic talent, or military service).

Figure 11

Majority of Financial Aid Programs for California Students Are Gift Aid

(In Millions)

|

Programa |

Coverage |

Expendituresb |

|

Gift Aid |

||

|

Pell Grant (federal) |

Some tuition and living expenses. |

$2,832 |

|

Cal Grant (state) |

Full tuition and some living expenses for students attending public and some private institutions in California. |

1,986 |

|

California College Promise Grantc (state) |

Full tuition for CCC students. |

758 |

|

UC Grant (state) |

Full tuition and living expenses for UC students. |

746 |

|

CSU State University Grant (state) |

Full tuition for CSU students. |

586 |

|

Middle Class Scholarship (state) |

Partial tuition for UC and CSU students not eligible for a Cal Grant. |

71 |

|

Supplement Education Opportunity Grant (federal) |

Some tuition and living expenses. |

65 |

|

CCC Full‑Time Student Success Grant (state) |

Some tuition and living expenses for full‑time CCC students. |

41 |

|

Subtotal |

($7,085) |

|

|

Loans |

||

|

Direct Student Loans (federal) |

Any college expense. More generous terms for financially needy students. |

$1,610 |

|

Parent PLUS Loans (federal) |

Any college expense. Available for parents of dependent students. |

402 |

|

Perkins Student Loans (federal) |

Any college expense. Typically more generous terms than other loans. |

47 |

|

Subtotal |

($2,059) |

|

|

Tax Benefitsd |

||

|

Higher education credits and deductions (federal) |

Tuition, books, and supplies. |

$1,210 |

|

Scholarshare savings plan (federal) |

Any college expense. Accounts have tax benefits. |

209 |

|

Coverdell education savings account (federal) |

Any K‑12 or college expense. Accounts have tax benefits. |

4 |

|

Subtotal |

($1,418) |

|

|

Work Study (Federal/State) |

Provides part‑time jobs. |

$74 |

|

Total |

$10,637 |

|

|

a All gift aid, work study, and Perkins Student Loans are need based. Other loans and tax credits are nonneed based. b Reflects 2015‑16 data for federal programs and 2016‑17 data for state programs. c Formerly known as the CCC Board of Governor’s Fee Waiver. d Estimated based on nationwide expenditures. |

||

Federal Formula Determines a Student’s Financial Need. Need‑based aid programs assess financial need using the federal Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA. The FAFSA asks students/families to provide various information, such as household income, certain available assets, and number of children in college. This information then feeds into a formula that determines an expected family contribution (EFC) toward college costs. A student’s financial need is the total cost of attendance (tuition and living costs combined) at a particular campus less his or her EFC.

Many Financial Aid Programs Available to California Students. Most programs are need based and most provide gift aid. If a student qualifies for more than one program, then campus financial aid offices “package” together aid for the student. When packaging aid, campuses first prioritize awarding gift aid before moving on to awarding loans and work study. Campuses do not award tax benefits. Students and parents claim these benefits on their tax returns.

Half of Public College Students Receive Full Tuition Coverage, Some Receive Aid for Living Expenses. Most state aid programs are geared toward providing full tuition coverage for financially needy students. These programs collectively cover full tuition for around 60 percent of undergraduate students at UC and CSU. At CCC, about half of students receive full fee waivers, paying for two‑thirds of all course units taken. In addition, the federal Pell Grant program and some state programs pay for some or all of financially needy students’ living expenses. Taken altogether, gift aid for financially needy students cuts their total college costs (tuition and living expenses) in half at the universities. For full‑time students attending CCC, gift aid covers a somewhat lower portion of the total cost of attendance—about one‑third.

Lower‑Income Families Have Lower Net Price of College. Average net price is the cost of attendance after gift aid. Figure 12 shows average net price for families at various income levels. Students/families with higher‑income levels pay more toward the cost of college than lower‑income students/families.

Figure 12

Net Price Lowest for Lowest‑Income Studentsa

(2015‑16)

|

Family Income Level |

Percent of Students |

Net Price |

|

University of California |

||

|

$0 ‑ 30,000 |

36% |

$9,266 |

|

$30,001 ‑ 48,000 |

20 |

10,287 |

|

$48,001 ‑ 75,000 |

18 |

13,580 |

|

$75,001 ‑ 110,000 |

11 |

20,627 |

|

Over $110,000 |

14 |

29,290 |

|

California State University |

||

|

$0 ‑ 30,000 |

41% |

$6,851 |

|

$30,001 ‑ 48,000 |

21 |

8,244 |

|

$48,001 ‑ 75,000 |

17 |

12,099 |

|

$75,001 ‑ 110,000 |

10 |

16,607 |

|

Over $110,000 |

12 |

18,815 |

|

California Community Colleges |

||

|

$0 ‑ 30,000 |

67% |

$5,927 |

|

$30,001 ‑ 48,000 |

20 |

6,532 |

|

$48,001 ‑ 75,000 |

11 |

8,757 |

|

$75,001 ‑ 110,000 |

1 |

10,113 |

|

Over $110,000 |

—b |

12,193 |

|

aReflects average total cost of attendance less financial aid for full‑time resident undergraduates. Excludes students who did not apply for or receive federal student loans, grants, or work study. bLess than 1 percent. |

||

Student Loan Debt Relatively Low. Each year, around 40 percent of UC and CSU undergraduates take out loans, with an average annual loan amount of $5,400 per borrower. Slightly more than half of UC and CSU students have loan debt at graduation, with debt at graduation averaging $20,500. At CCC, 2 percent of students borrow each year, with an average annual loan amount of $4,500. Student borrowing in California tends to be lower than in other states. For example, about 60 percent of students at four‑year public universities nationally graduate with loan debt, with an average debt load upon graduation of $27,300. (These figures only include student loans, not other forms of debt, such as credit card debt.)

Student Loan Default Rates Low at UC and CSU, Higher at CCC. Almost all borrowing at UC, CSU, and CCC is through federal loans. For each cohort of undergraduate borrowers entering repayment, the federal government tracks the share defaulting within three years. Three‑year student loan default rates tend to be low at UC and CSU but higher at CCC. Specifically, while no UC campus has a rate greater than 3.6 percent and no CSU campus has a rate greater than 6.7 percent, the vast majority of CCC campuses have rates in excess of 10 percent. The average rate for all institutions nationally is 11.3 percent. On average, older students and students who do not complete their degrees are significantly more likely to default.

University of California

In this section, we provide an overview of the Governor’s budget proposals for UC and analyze key cost increases facing the university in 2018‑19. At the end of the section, we assess UC’s 2018‑19 capital outlay request.

Overview

Below, we first focus on the 2018‑19 budget plan for UC and then examine whether UC is likely to meet specific 2017‑18 budget conditions.

2018‑19 Budget Plan

UC Estimated to Receive $35.6 Billion From All Sources in 2018‑19. As Figure 13 shows, UC’s total budget would increase by $733 million (2.1 percent) over the 2017‑18 level. One‑quarter of total funding ($8.9 billion) consists of “core funds” (primarily state General Fund and student tuition revenue) that support the university’s undergraduate and graduate educational programs. Core funding would increase by $70 million (0.8 percent). The remainder of UC funding comes primarily from its five medical centers, sales and services (including housing, bookstores, and academic extension), and the federal government (primarily for research and financial aid).

Figure 13

University of California Funding by Source

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2016‑17 Actual |

2017‑18 Revised |

2018‑19 Proposed |

Change From 2017‑18 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Core Funds |

|||||

|

General Fund |

|||||

|

Ongoing |

$3,279 |

$3,367 |

$3,469 |

$102 |

3.0% |

|

One time |

262 |

177 |

0 |

‑177 |

‑100.0 |

|

Carryovera |

‑45 |

5 |

39 |

34 |

639.0 |

|

Tuition and feesb |

4,507 |

4,816 |

4,936 |

120 |

2.5 |

|

Lottery |

38 |

42 |

42 |

—c |

‑0.1 |

|

Other core fundsd |

353 |

405 |

395 |

‑10 |

‑2.5 |

|

Totals |

$8,394 |

$8,813 |

$8,882 |

$70 |

0.8% |

|

Other Funds |

|||||

|

Medical centers |

$10,395 |

$11,330 |

$11,670 |

$340 |

3.0% |

|

Sales and services |

6,670 |

7,134 |

7,345 |

211 |

3.0 |

|

Federal |

3,649 |

3,735 |

3,776 |

41 |

1.1 |

|

Private |

2,250 |

2,347 |

2,400 |

53 |

2.3 |

|

State |

342 |

441 |

437 |

‑4 |

‑0.9 |

|

Other |

1,031 |

1,049 |

1,071 |

22 |

2.1 |

|

Totals |

$24,337 |

$26,036 |

$26,699 |

$663 |

2.5% |

|

Grand Totals |

$32,730 |

$34,848 |

$35,581 |

$733 |

2.1% |

|

FTE Studentse |

263,957 |

272,267 |

275,267 |

3,000 |

1.1% |

|

Core Funding Per Student |

$31,800 |

$32,368 |

$32,268 |

‑$100 |

‑0.3% |

|

aOf the $262 million one time provided in 2016‑17, $45 million was unspent. UC plans to spend $5 million of the carryover in 2017‑18 and the remainder in 2018‑19. bIncludes funds that UC uses to provide tuition discounts and waivers to certain students. In 2018‑19, UC plans to provide $1 billion in such aid. cAmount is less than $500,000. dIncludes a portion of overhead funding from federal and state grants, a portion of patent royalty income, and Proposition 56 funding designated for graduate medical education. eOne full‑time equivalent (FTE) represents 30 credit units for an undergraduate and 24 credit units for a graduate student. Student counts includes resident and nonresident students. |

|||||

Governor’s Budget Provides $92 Million General Fund Base Increase. As Figure 14 shows, the main General Fund change to UC in 2018‑19 would be a $92 million ongoing unrestricted base increase. The increase would reflect a 3 percent increase to UC’s ongoing General Fund support to campuses. The Governor’s budget does not include an increase for the Office of the President (UCOP), which the Legislature began line‑item budgeting in 2017‑18. Under the Governor’s budget, UCOP remains funded at $349 million. In addition to the base increase, the Governor (1) provides $10 million ongoing to offset expiring one‑time Proposition 56 monies in the 2017‑18 budget, (2) removes $177 million in one‑time funds (primarily for UC’s Retirement Plan) provided in the 2017‑18 budget, and (3) reappropriates certain unspent one‑time funds provided in the 2016‑17 budget.

Figure 14

University of California General Fund Changes

(In Millions)

|

2017‑18 Revised Funding |

$3,549.4 |

|

Ongoing |

|

|

Provide unrestricted base increase |

$92.1 |

|

Replace one‑time Proposition 56 funds with General Fund |

10.0 |

|

Subtotal |

($102.1) |

|

One Time |

|

|

Spend 2016‑17 carryover |

$34.1 |

|

Remove one‑time funding provided in 2017‑18 |

‑176.6 |

|

Subtotal |

(‑$142.5) |

|

Total |

‑$40.4 |

|

2018‑19 Proposed Funding |

$3,509.0 |

Under Governor’s Budget, Total of $300 Million Available for Ongoing Spending. Beyond the proposed $92 million General Fund base increase, UC plans to tap an additional $208 million. This additional funding would come from various fund sources, redirections, and savings, as described below.

- $120 Million From Tuition and Fees. The increase would result from 1.1 percent enrollment growth ($71 million), a $978 (3.5 percent) increase to nonresident supplemental tuition ($35 million), and a $54 (4.8 percent) increase to the Student Services Fee ($14 million). The Governor assumes resident tuition levels remain flat year over year. Of the increase in gross tuition and fee revenues, we estimate $18.2 million would be redirected for financial aid.

- $88 Million From Anticipated Savings and Alternative Revenue Sources. This amount consists of (1) $30 million in new revenue from increased investment returns, (2) a package of $15 million in identified redirections intended to fund enrollment growth in 2018‑19, (3) $14 million from phasing out financial aid for nonresident students, (4) $10 million in savings from improved procurement practices, (5) $10 million in philanthropic donations, and (6) $9 million in savings from retiring obligations associated with a past lawsuit.

UC Likely to Prioritize Increases for Compensation and Enrollment. Though the UC Regents have not yet adopted a budget plan for 2018‑19, its draft budget prioritizes spending for compensation increases and enrollment growth. As the top part of Figure 15 shows, UC for 2018‑19 is likely to increase faculty and staff compensation by $104 million. It also is budgeting $57 million for planned enrollment growth. Additionally, UC has identified various other high priorities, including student financial aid and mental health services, that total $70 million. After funding all these high priorities, $69 million would remain available for other cost increases.

Figure 15

UC Has More Spending Priorities Than Can Be Covered by $300 Million Assumed in Governor’s Budget

(In Millions)

|

Top Prioritiesa |

|

|

Compensation |

|

|

Benefit cost increases |

$44 |

|

Faculty Merit Program |

32 |

|

Represented staff salary increases (3.6 percent) |

28 |

|

Subtotal |

($104) |

|

Other Cost Increases |

|

|

Operating expenses and equipment (2.5 percent) |

$32 |

|

Financial aid |

18 |

|

Debt service |

15 |

|

Mental health services |

5 |

|

Subtotal |

($70) |

|

Enrollment Growth |

|

|

Resident undergraduate (1,500 students) |

$28 |

|

Nonresident undergraduate (1,000 students) |

19 |

|

Graduate (500 students) |

9 |

|

Subtotal |

($57) |

|

Total Top Priorities |

$231 |

|

Remaining Priorities |

|

|

Funds Availableb |

$69 |

|

Calls on Available Funds |

|

|

Faculty and nonrepresented staff salary increases (3 percent) |

$83 |

|

Academic quality |

50 |

|

Deferred maintenance (one time) |

35 |

|

Financial aid |

27 |

|

Enrollment growth (500 resident undergraduates)c |

9 |

|

aReflects LAO assumptions of UC’s top spending priorities based on UC and state budget documents and conversations with UC staff. bReflects funding implicitly remaining under Governor’s budget. cWere UC to add these additional students, $4 million of this cost would be funded from the tuition revenue those students would pay. |

|

UC Has Many Other Calls on Remaining Funding. The UC Regent’s draft budget plan assumes significantly more funding is available than implicitly recognized in the Governor’s budget. Whereas the Governor’s budget implicitly recognizes the $300 million in new funding, UC’s draft budget assumes $437 million. The largest revenue difference between the two plans is UC’s preliminary budget assumption that it would raise tuition by 2.5 percent. The largest spending difference between the two plans is UC’s preliminary request for additional salary increases for faculty and other nonrepresented staff. Other notable spending differences include UC’s preliminary request for $50 million for academic quality initiatives and $35 million one‑time General Fund for deferred maintenance projects. The bottom part of Figure 15 shows all the calls on the $69 million remaining under the Governor’s assumed spending level.

Governor Is Not Supporting Further Tuition Increases at This Time. Though UC has been considering a potential tuition increase and built a preliminary budget assuming associated tuition revenue, the Governor has indicated that he is not in support of a tuition increase at this time. Specifically, the administration states that it is concerned about raising tuition on resident students because (1) in its view, UC could do more to reduce its overall cost structure; (2) students who do not have their tuition covered by financial aid would face additional financial burden; and (3) it indirectly would increase state costs for the Cal Grant program, which covers the cost of systemwide tuition for eligible low‑income undergraduate students. The administration calls on UC to implement further reforms before increasing tuition, though it does not specify which reforms it expects the university system to undertake.

2017‑18 Budget Conditions

Uncertain Whether UC Will Meet Every Expectation Set in Last Year’s Budget. The 2017‑18 budget conditioned $50 million on UC meeting certain expectations. As outlined in provisional budget language, the Director of Finance is to determine by May 1, 2018 whether UC has made a good faith effort to meet these expectations. Figure 16 lists these expectations. UC reports that it has completed one of them (adopting a policy prohibiting supplemental retirement payments) and is close to completing another condition (piloting activity‑based costing at three campuses). Some uncertainty surrounds whether UC will meet the remaining three conditions, as noted below.

- Budget Transparency. UC has provided greater clarity on the funding amounts and sources supporting its systemwide and presidential initiatives. Whether UC has improved its overall budget documents showing all revenues, expenditures, and carryover funds to the administration’s satisfaction is not yet clear.

- Auditor’s Recommendations. Of the ten recommendations the Auditor calls upon UC to complete by April 2018, the Auditor to date deems one as fully implemented and another as partially implemented. UC indicates that it is continuing to work on implementing all of the recommendations.

- Transfer Enrollment. Some uncertainty exists whether two campuses (Riverside and Santa Cruz) will attain the expected freshman‑to‑transfer ratio. Below, we describe the expected ratio and UC’s efforts thus far to attain it.

Figure 16

2017‑18 Budget Linked $50 Million With UC Meeting Numerous Expectations

|

By May 2018, the University of California must demonstrate it has made a good faith effort to achieve the following expectations: |

|

|

|

|

|

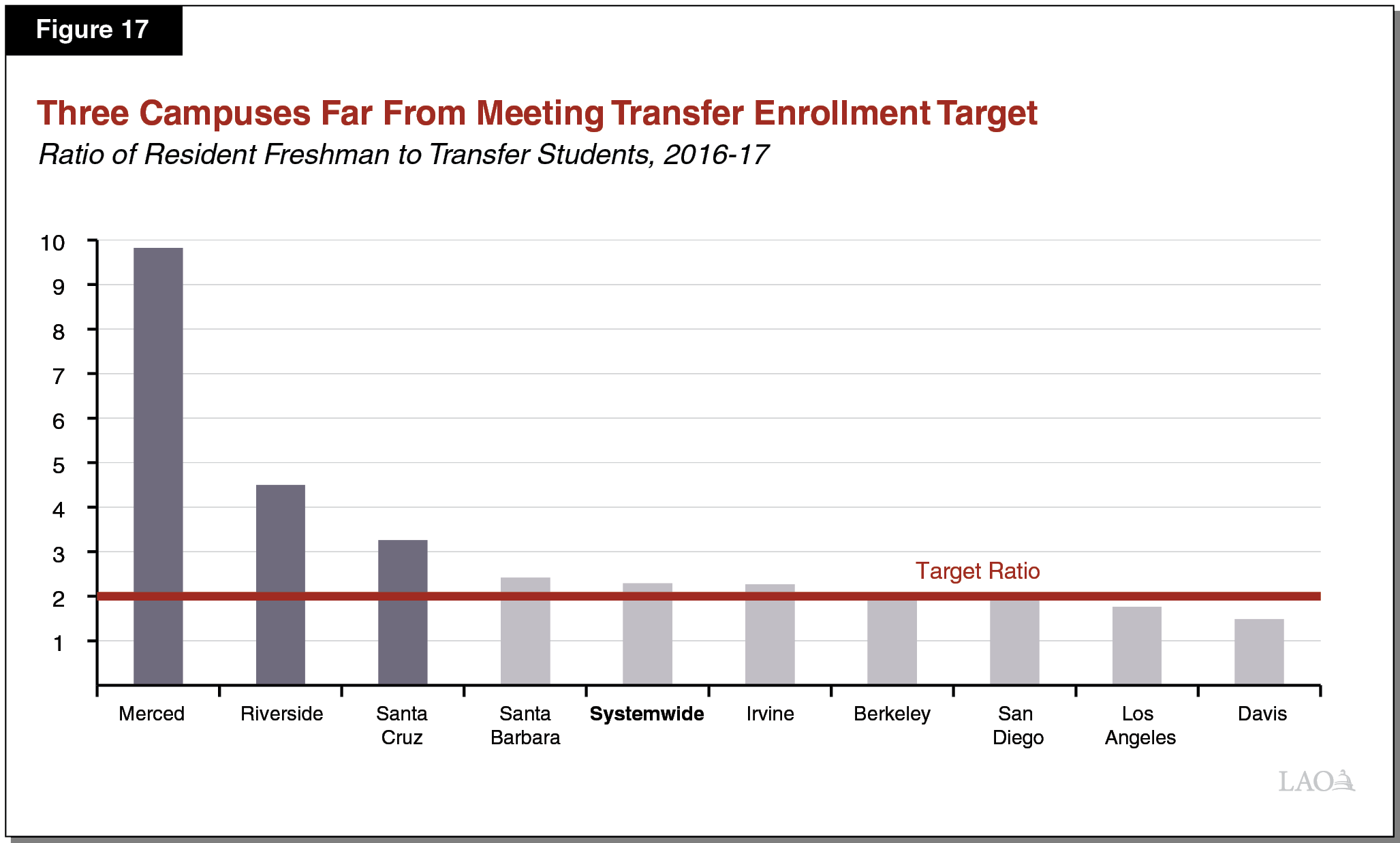

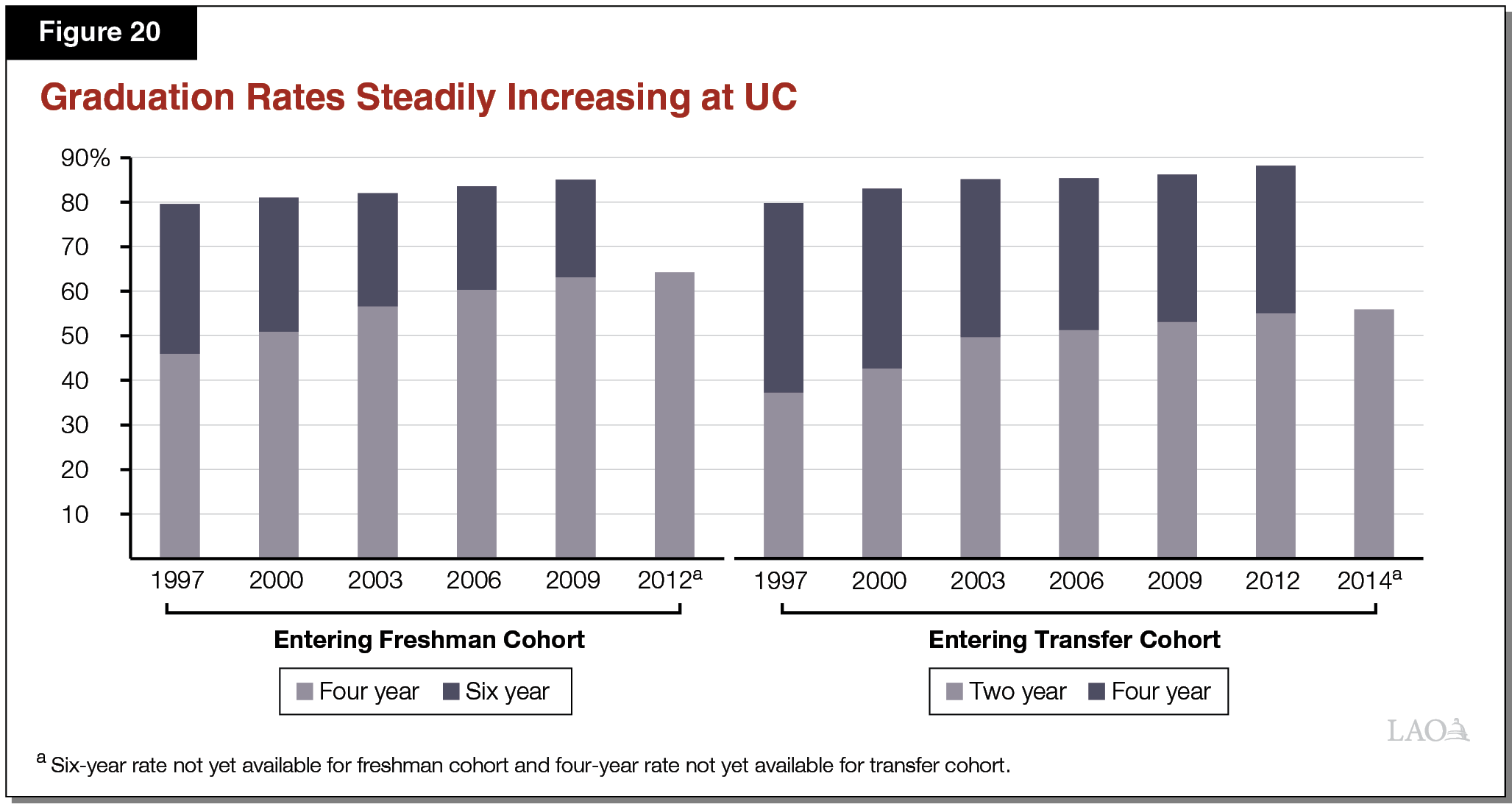

UC Has Had Aspirational Goal of Meeting Freshman‑to‑Transfer Ratio. Consistent with the state’s Master Plan for Higher Education, which envisions students transferring from community colleges to the universities, UC historically has aimed to enroll at least one new transfer student for every two new freshmen. (The ratio is intended to implement a recommendation in the Master Plan that no more than 40 percent of undergraduate enrollment at UC be lower‑division.) Over the past ten years UC has not attained this target, with the systemwide ratio hovering at about 1 transfer student for every 2.3 freshmen. Though the system does not meet the target, some campuses do (see Figure 17). Five of UC’s nine undergraduate‑serving campuses, however, did not meet the target in 2016‑17, with three of those campuses (Merced, Riverside, and Santa Cruz) especially far from the target.

UC Developed Plans for Santa Cruz and Riverside Campuses to Increase Transfer Enrollment. Due to concerns that the Riverside and Santa Cruz campuses would face the greatest challenge in boosting transfer enrollment to meet the 2017‑18 budget condition, each campus developed a strategic plan to attain the 2‑to‑1 ratio. The plans are similar. Both plans aim to increase outreach efforts to community colleges. Riverside, for example, plans to increase recruitment visits to its nearby community colleges as well as seven other community colleges with historically high transfer rates to UC. Riverside also plans to reach out to transfer students applying to CSU San Bernardino in an effort to reduce enrollment pressures on that campus. In addition to ramping up outreach efforts, both UC campuses plan to review their course articulation agreements with community colleges. Additionally, both campuses plan to review their transfer student admission requirements and potentially admit more lower‑division transfer applicants or certain students who have not completed all of their pre‑major course requirements.

UC Also Planning Systemwide Efforts to Better Streamline Transfer Process. These efforts include (1) establishing an agreement with the CCC Chancellor’s Office to share contact information for students deemed transfer ready, (2) increasing outreach efforts to community college counselors and students, and (3) exploring whether UC could better align its existing transfer pathways with the associate degree for transfer (ADT).

Administration Has Asked for Additional Efforts. In a December 2017 letter from the Department of Finance to UC, the department indicated that it thought UC’s plans were reasonable but additional effort was warranted. In particular, the Department of Finance noted that UC could do more to align its existing transfer pathways with the ADT. The department specifically indicated that UC could demonstrate good faith effort in this area by entering into a memorandum of understanding with the CCC Chancellor’s Office by May 1, 2018. In conversations with our office, UC indicated that it is working on implementing the recommendation.

A Couple of Options to Consider if UC Does Not Meet Transfer Condition. Were UC to fall short of achieving the 2‑to‑1 transfer ratio in 2018‑19, the Legislature could consider adopting a systemwide target next year instead of campus‑specific targets. A systemwide approach would give UC greater flexibility to increase transfer enrollment at campuses where the demand is highest. Additionally, we believe UC could continue working on simplifying the transfer process for students, especially by aligning its transfer admissions and lower‑division requirements with the ADT. Better alignment in this area would help transfer students better plan for their coursework while at community colleges and complete their upper‑division studies at UC more efficiently.

Key Cost Drivers

Legislature Has Key Decisions to Make Regarding UC Cost Increases. As we have noted in past analyses, the Legislature faces two key decisions regarding UC’s budget each year. The first decision regards which proposed cost increases are acceptable. Typically, the Legislature gives first priority to covering cost increases needed to maintain existing services. At the universities, the largest of these costs relate to compensation and enrollment. After addressing these base issues, the Legislature then typically considers proposals for program expansions or new programs.

Legislature Also Faces Key Decisions About How to Cover Those Cost Increases. After deciding which cost increases to support, the second decision regards how to fund them. Traditionally, UC cost increases have been implicitly shared between the state (through budget augmentations), resident students and their families (through tuition increases), and other fund sources (such as nonresident students). Under the Governor’s proposal, most of UC’s increase, after factoring funds from nonresident students and other redirections, would be covered by the state. Though the Legislature could choose to have the state bear the full effect of approved cost increases, it alternatively could consider sharing any cost increases about evenly between the state and nonfinancially needy students. (The state provides full tuition coverage for financially needy students.) Such an approach would recognize the notable public and private benefits of a UC education.

Legislature Faces Three Key Cost Areas. To assist the Legislature in setting its UC funding priorities for the budget year, we analyze three proposed cost increases: (1) salary increases for faculty and staff, (2) enrollment growth, and (3) UC’s plan for academic quality initiatives. Throughout our analysis, we do not assume fundamental changes to the way UC delivers instruction or runs its operations. If UC found new ways of instructing and operating that substantially reduced costs, these savings could be redirected to funding desired cost increases.

Compensation

Employee Compensation Is UC’s Largest Expense. Similar to most state agencies, employee compensation is UC’s largest cost. Compensation for faculty, staff, and administrators accounts for over 80 percent of UC’s core budget.

UC Regents Set Compensation Policies and Determine Compensation Levels. At UC, most faculty, as well as managers and other administrative staff, are not represented by employee unions. The remaining employees (such as health care workers at UC’s five medical centers; graduate student teaching assistants; and clerical, custodial, and other support staff) are represented by 13 systemwide and 14 campus‑specific collective bargaining units. Cost increases resulting from collective bargaining agreements, salary increases for nonrepresented employees, and the university’s employment benefit programs are funded from within UC’s support budget. By comparison, for most state agencies, the Legislature exerts more direct control over compensation policies and associated costs. Notably, state law provides guidance on health benefits, pension benefits, and other employment and post‑employment benefits available for state employees. State law also requires collective bargaining agreements between the state and employees to be ratified by the Legislature before going into effect.

UC Planning 3 Percent to 4 Percent Compensation Increases. UC’s preliminary budget plan assumes 3 percent general faculty salary increases ($83 million). It assumes an average salary increase of 3.6 percent across all its represented employee groups ($20 million). Additionally, UC budgets for benefit cost increases, including employee health, retiree health, and pension contributions.

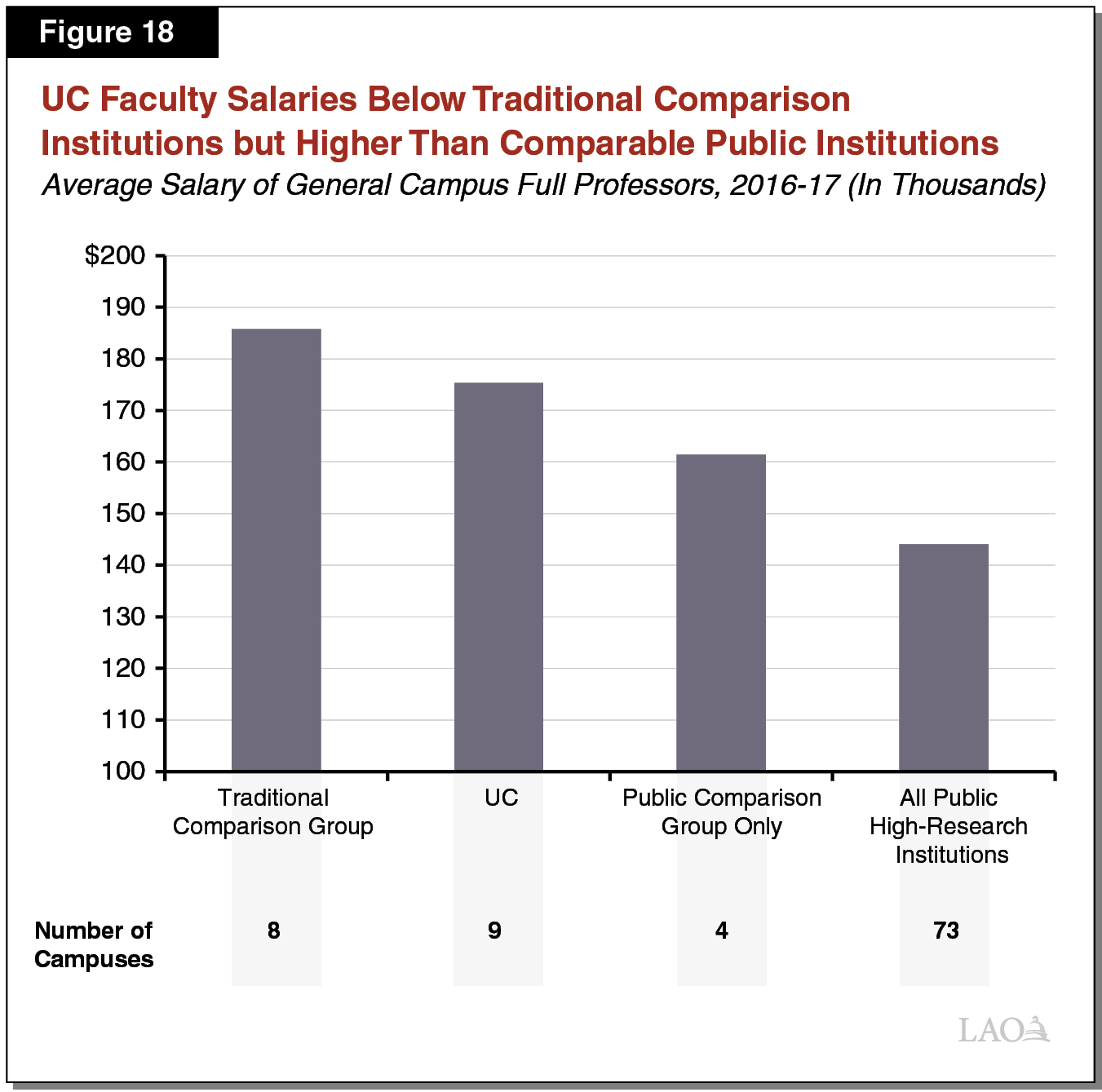

UC Faculty Salaries Below Average of Traditional Comparison Institutions. Historically, UC has used compensation data from a group of eight research universities to gauge the competitiveness of its faculty compensation. The group includes four private institutions (such as Stanford and Harvard) and four public flagship institutions (such as the University of Michigan and the University of Virginia). As Figure 18 shows, average salaries for full professors at UC are below the average of these eight institutions but above the average of the four public comparison institutions. Salaries for associate and assistant professors compare similarly. In its preliminary budget plan, UC expresses concern that campuses face increasing difficulty competing with these comparison institutions to attract and retain high‑quality faculty.

Salaries Remain Competitive Relative to Public Research Institutions. Comparing UC salaries to a small number of relatively expensive private and public research institutions may not accurately reflect the broader academic market in which UC campuses compete for faculty. To provide a broader picture of UC’s labor market, we use federal data to estimate the average salary of faculty at 73 public institutions around the country that conduct a similar level of research as UC. Figure 18 shows that UC professors make notably higher average salaries than the average across all of the 73 public institutions with intensive research.

Enrollment Growth

Last Year’s Budget Set 2018‑19 Enrollment Target. The 2017‑18 budget set an expectation for UC to enroll 1,500 more undergraduate resident students in 2018‑19 over the 2017‑18 level. In meeting this target, UC was to enroll at least one new transfer student for every two new freshmen. That is, at least 500 of the additional 1,500 students were to be new transfer students.

UC to Support Enrollment Growth From Redirected Funding. The 2017‑18 budget did not designate additional funding to support the additional enrollment in 2018‑19. Instead, the budget directed UC to report by December 1, 2017 on existing programs budgeted at UCOP from which monies could be redirected to support the enrollment growth. UC was expected to consult with legislative staff and the Department of Finance in the summer and fall regarding the possible changes. The budget also stated an expectation that enrollment costs be shared and UC’s cost structure reviewed. This process was designed to give legislative staff an opportunity to provide input on the possible programmatic reductions and allow the Legislature to finalize funding decisions in the 2018‑19 budget.

UC Identifies $15 Million That Could Be Redirected to Fund Enrollment Growth. Figure 19 shows how UC proposes to achieve the $15 million in redirected resources intended to support enrollment growth. Of this amount, $8 million would come from reductions to UCOP’s budget. The remaining funds would come from other sources, including: (1) redirected lottery funds ($3 million); (2) savings, according to UC, by providing certain systemwide programs a smaller budget increase than otherwise planned for 2018‑19 ($2.5 million); and (3) eliminating certain programs budgeted at certain campuses ($1.5 million).

Figure 19

UC’s Proposed Redirection Plan for Funding 2018‑19 Enrollment Growth

(In Millions)

|

Funding |

|

|

Reductions to Office of the President |

|

|

UC Presidential Initiatives Fund |

$2.0 |

|

Contingency budget (50 percent reduction) |

2.1 |

|

Professional services budget (5 percent reduction) |

1.5 |

|

Chancellor’s House maintenance |

0.5 |

|

Unpaid merit awards |

0.5 |

|

Administrative fund for campus chancellors |

0.4 |

|

Travel and meetings budget (10 percent reduction) |

0.4 |

|

Star Award Policy |

0.3 |

|

Outreach and membership activities |

0.2 |

|

Administrative fund for Office of the President (60 percent reduction) |

0.1 |

|

Subtotal |

($8.0) |

|

Growth in lottery funds |

$3.0 |

|

Reduced growth to campus programs |

|

|

Agricultural Experimental Stations |

$1.4 |

|

Neuropsychiatric Institutes |

0.5 |

|

Scripps |

0.4 |

|

Mental Health Teaching Support |

0.2 |

|

Medical Investigation of Neurodevelopmental Disorders (MIND) Institute |

0.1 |

|

Subtotal |

($2.5) |

|

Eliminated campus programs |

|

|

California Program on Access to Care |

$0.9 |

|

Health Initiatives of the Americas |

0.3 |

|

US‑Mexico Social Security and Tax Policy |

0.2 |

|

Graduate Fellows Program |

0.1 |

|

Subtotal |

($1.5) |

|

Total |

$14.9 |

Overall Redirection Plan Is a Reasonable Starting Point. Overall, we think UC’s proposed list is a reasonable starting point, as UC met with legislative staff throughout the fall and identified savings sufficient to support the state share of the new enrollment. While we believe the redirections are reasonable for 2018‑19, we note that the identified savings are very modest. During spring budget hearings, the Legislature may want to consider whether such a plan meets the Legislature’s intent to have the university more fundamentally revisit its cost structure.

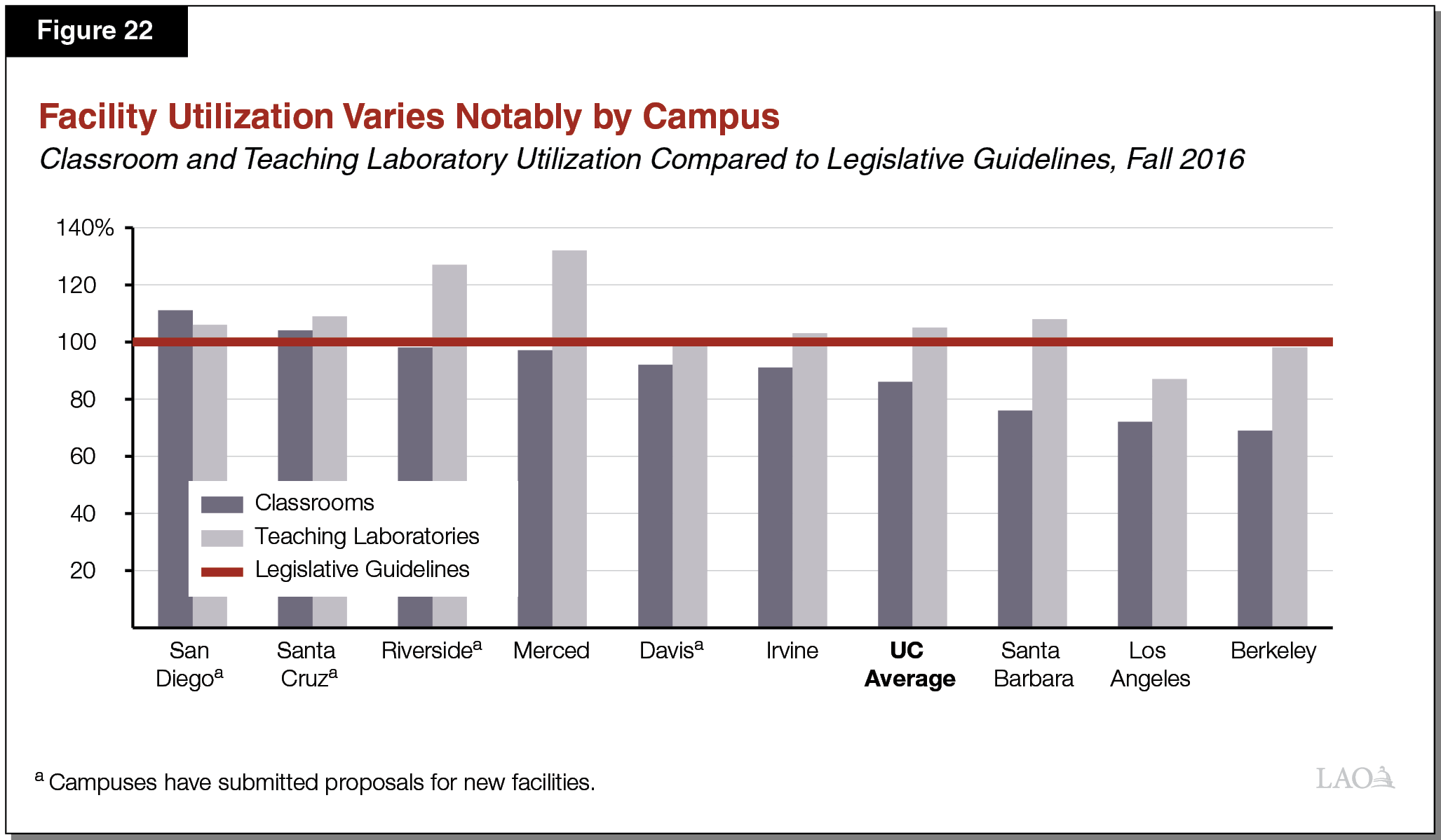

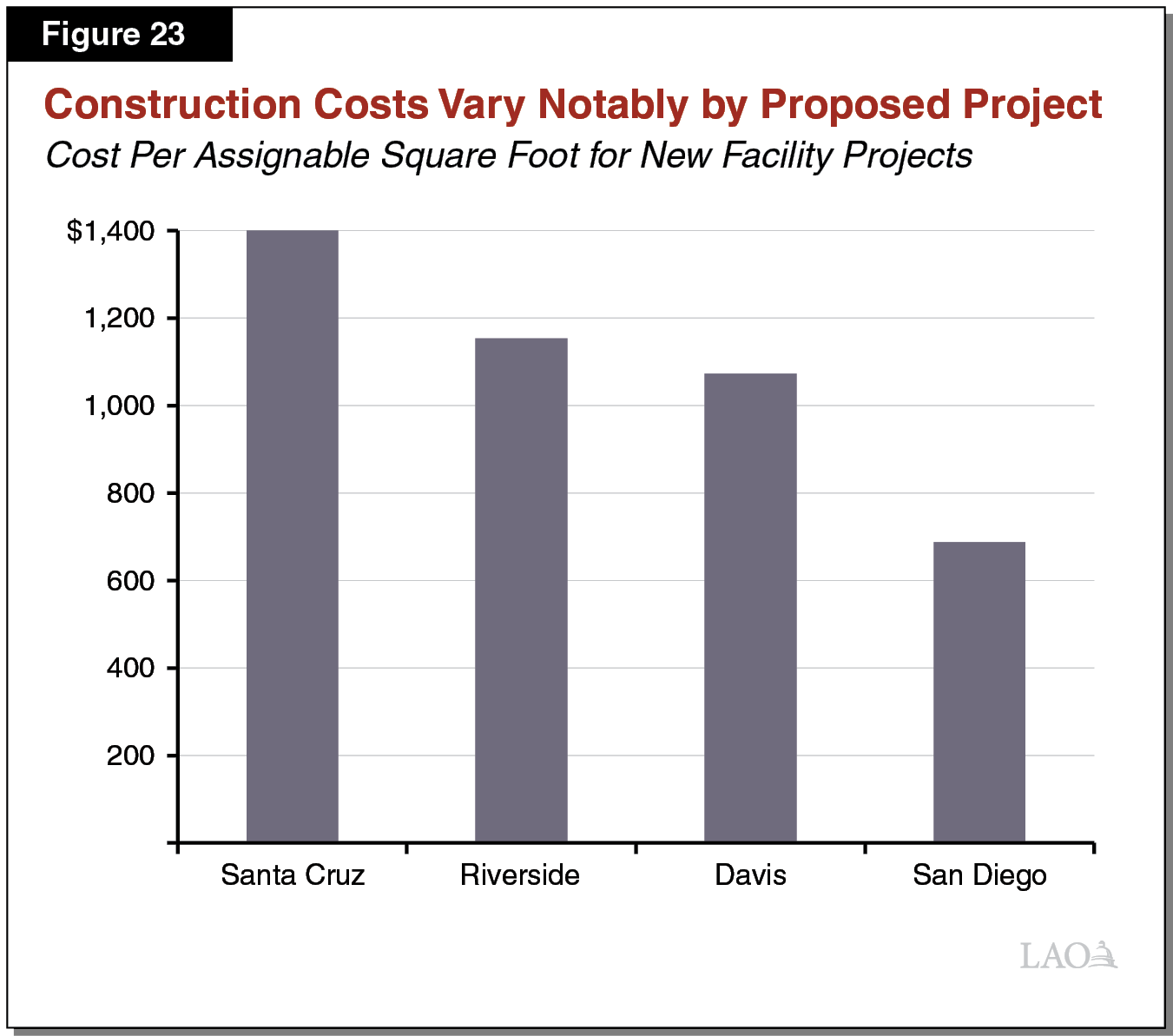

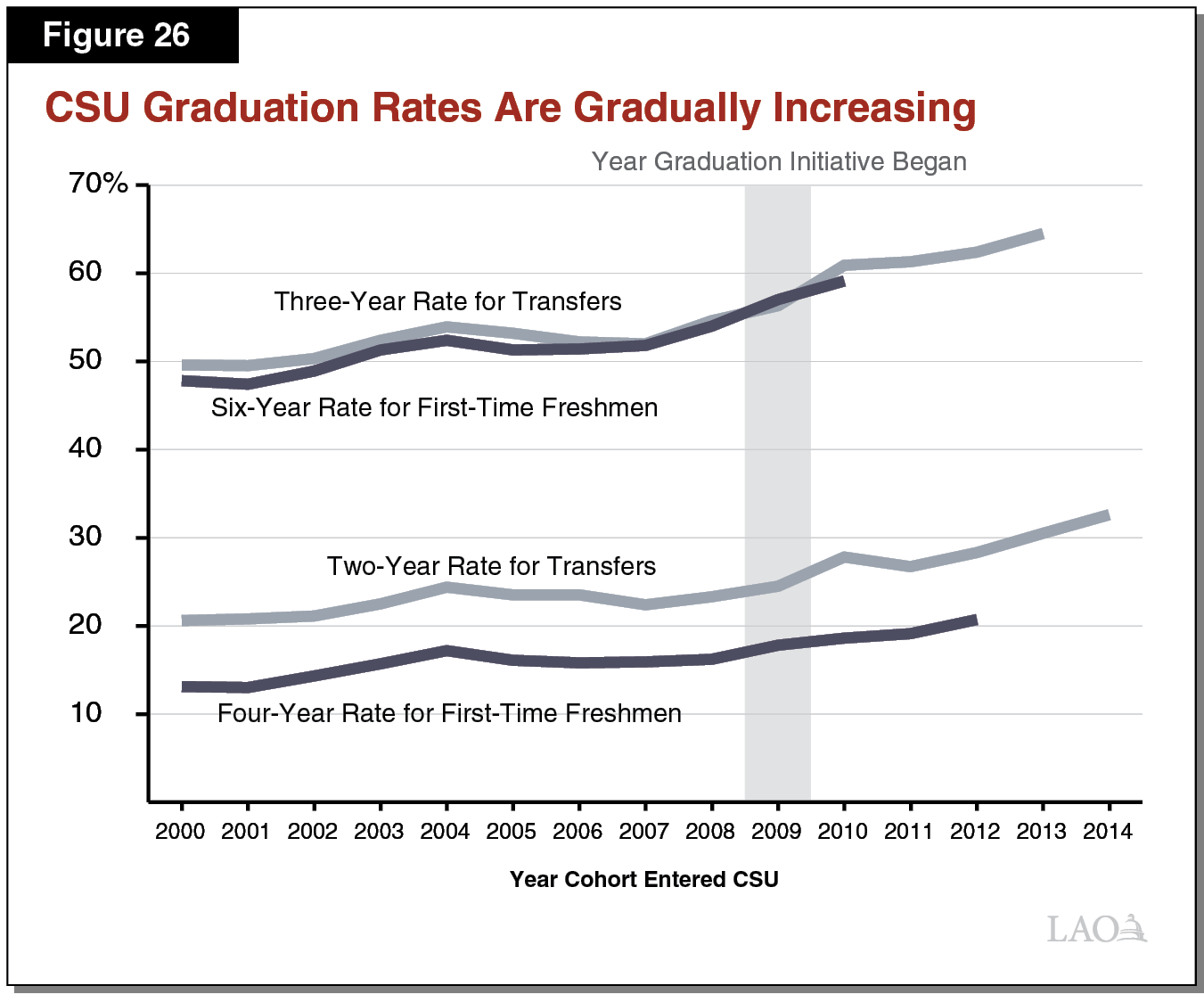

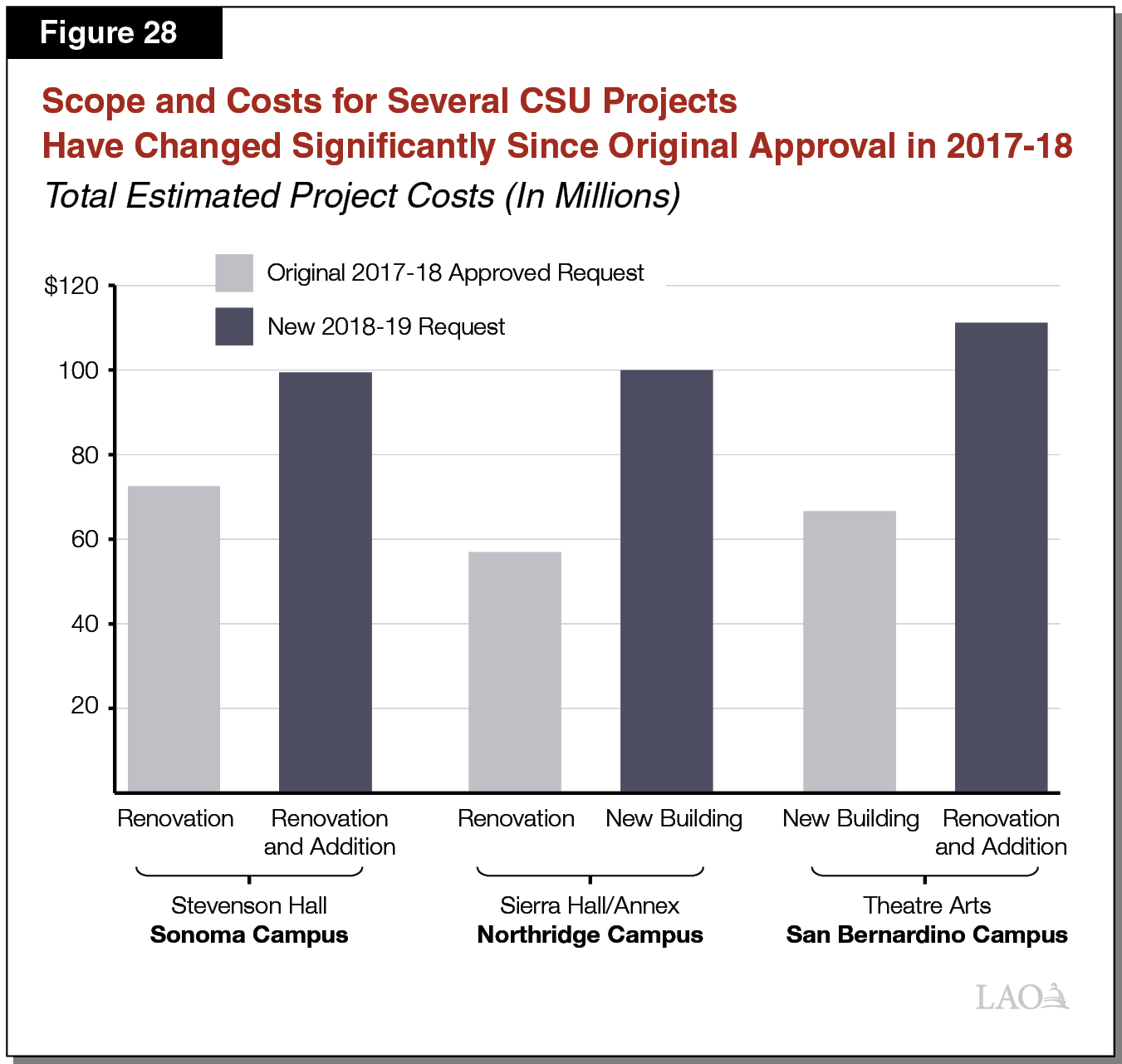

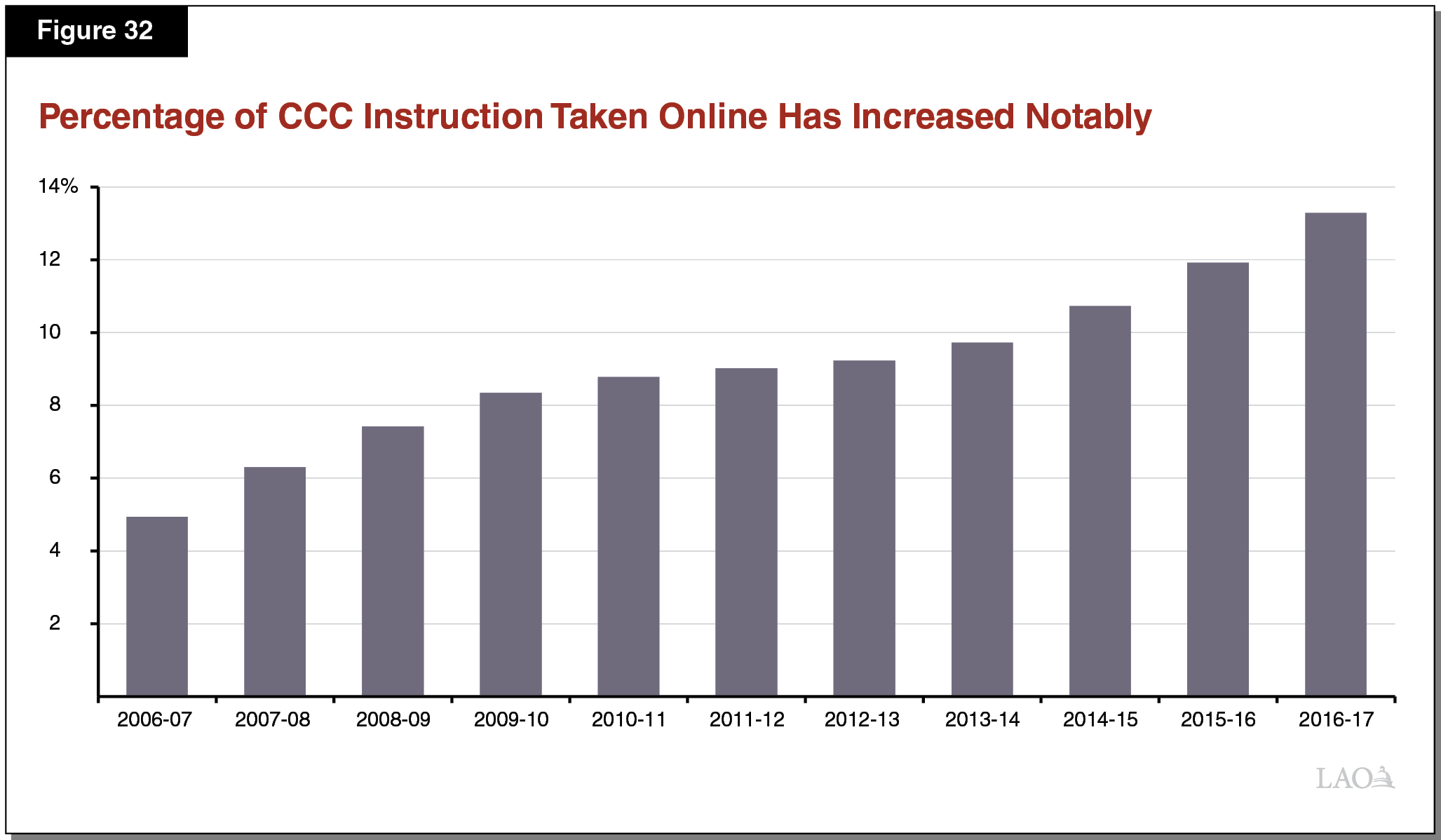

Recommend Conforming Adjustment to UCOP Line Item. Regardless of the Legislature’s specific funding decision for enrollment growth in 2018‑19, we recommend any programmatic reductions to UCOP be reflected in the office’s line item in the budget. That is, were the Legislature to authorize UC’s proposed enrollment funding plan, we recommend it subtract $8 million from UCOP’s appropriation (bringing the line item down to $341 million) and transfer the funding to the campuses.