Total Spending Down by 38 Percent. Expenditures for resources and environmental protection programs from the General Fund, various special funds, and bond funds are proposed to total $6.7 billion in 2010–11, which is 5.6 percent of all state–funded expenditures proposed for the budget year. This level is a decrease of $4 billion, or 38 percent, below estimated expenditures for the current year. The proposed net reduction is mostly from bond funds. Specifically, the budget proposes bond expenditures totaling about $1 billion in 2010–11—a decrease of $4.2 billion, or 80 percent, below estimated bond expenditures in the current year.

The budget also includes a net reduction of $134 million (7 percent) in General Fund spending, reflecting both proposed spending decreases and increases. The spending decreases reflect a combination of program expenditure reductions and funding shifts to alternative new revenue sources. The budget includes a reduction of $33 million for emergency fire suppression, reflecting an estimate that a lower level of resources will be needed in the budget year following a high level of spending on firefighting activities in the current year significantly beyond the amounts initially budgeted. Still, even with this decrease, the $223 million from the General Fund proposed for emergency fire suppression in 2010–11 is the largest amount ever initially proposed in the Governor’s budget plan. This amount is based on the most recent five–year average of these costs. In addition, the budget reflects two major funding shifts in the resources area for the budget year: (1) the replacement of $140 million General Fund support in the Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR) with new revenues from the proposed Tranquillon Ridge oil and gas lease agreement and (2) the replacement of $200 million General Fund support in the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) with new revenues from a proposed surcharge on property insurance premiums statewide.

The budget proposes increased General Fund spending as follows: (1) an additional $201 million to pay for resources–related bond debt–service costs, an increase of 28 percent above estimated current–year expenditures for this purpose; and (2) $30 million to restore General Fund expenditures in the Department of Fish and Game (DFG) that were shifted on a one–time basis to a special fund in the current year. Although not reflected in the resources spending totals, the budget also reflects the administration’s intent to make a $98 million partial repayment of a loan made from the Beverage Container Recycling Fund to the General Fund in a prior year.

Multiple Funding Sources; Special Funds Predominate. In contrast to the current year where bond funding predominates, the largest proportion of state funding for resources and environmental protection programs in the budget year—about $3.8 billion (or 57 percent)—would come from various special funds. These special funds include the Environmental License Plate Fund, the Fish and Game Preservation Fund, funds generated by beverage container recycling deposits and fees, an “insurance fund” for the cleanup of leaking underground storage tanks, and a relatively new electronic waste recycling fee. Of the remaining expenditures, $1.8 billion would come from the General Fund (27 percent of total expenditures) and $1 billion from bond funds (16 percent of total expenditures).

Summary of Resource Spending Proposals. Figure 1 shows spending for major resources programs—that is, those programs generally within the jurisdiction of the Natural Resources Agency. As the figure shows, the General Fund provides a significant amount of the funding for a number of resources departments. We discuss the extent to which the General Fund is used to support particular resources (as well as environmental protection) programs in greater depth later in this analysis. The year–over–year changes in General Fund spending mostly reflect funding shifts (both replacing and restoring General Fund support), rather than changes in the level of program expenditures.

Figure 1

Selected Funding Sources Resources Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

Actual

2008–09

|

Estimated

2009–10

|

Proposed

2010–11

|

Change From 2009–10

|

|

Department

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Resources Recycling and Recoverya

|

|

|

|

|

|

Beverage container recycling funds

|

—

|

$625.9

|

$1,201.6

|

$575.7

|

92.0%

|

|

Other funds

|

—

|

102.6

|

202.3

|

99.7

|

97.2

|

|

Totals

|

—

|

$728.5

|

$1,403.9

|

$675.4

|

92.7%

|

|

Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire)

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$825.3

|

$807.7

|

$554.1

|

–$253.6

|

–31.4%

|

|

Other funds

|

534.0

|

341.6

|

1,342.3

|

1,000.7

|

292.9

|

|

Totals

|

$1,359.3

|

$1,149.3

|

$1,896.4

|

$747.1

|

65.0%

|

|

Fish and Game

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$82.7

|

$37.4

|

$68.9

|

$31.5

|

84.2%

|

|

Fish and Game Fund

|

77.6

|

123.1

|

106.6

|

–16.5

|

–13.4

|

|

Bond funds

|

44.4

|

91.4

|

27.0

|

–64.4

|

–70.5

|

|

Other funds

|

128.3

|

160.6

|

185.1

|

24.5

|

15.3

|

|

Totals

|

$333.0

|

$412.5

|

$387.6

|

–$24.9

|

–6.0%

|

|

Parks and Recreation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$135.2

|

$123.1

|

—

|

$123.1

|

–100.0%

|

|

Parks and Recreation Fund

|

111.6

|

125.7

|

$266.3

|

140.6

|

111.9

|

|

Bond funds

|

44.9

|

452.4

|

91.0

|

–361.4

|

–79.9

|

|

Other funds

|

99.2

|

278.3

|

222.2

|

–56.1

|

–20.2

|

|

Totals

|

$390.9

|

$979.5

|

$579.5

|

–$400.0

|

–40.8%

|

|

Water Resources

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$133.2

|

$107.7

|

$110.1

|

$2.4

|

2.2%

|

|

State Water Project funds

|

1,396.4

|

1,568.7

|

2,043.8

|

475.1

|

30.3

|

|

Bond funds

|

645.4

|

2,549.8

|

482.4

|

–2,067.4

|

–81.1

|

|

Electric Power Fund

|

4,953.3

|

4,064.6

|

3,688.8

|

–375.8

|

–9.3

|

|

Other funds

|

38.4

|

135.4

|

98.5

|

–36.9

|

–27.3

|

|

Totals

|

$7,166.8

|

$8,426.2

|

$6,423.6

|

–$2,002.6

|

–23.8%

|

|

Delta Stewardship

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bond funds

|

—

|

—

|

$9.7

|

—

|

—

|

|

Other funds

|

—

|

—

|

39.4

|

—

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

—

|

—

|

$49.1

|

—

|

—

|

While the budget proposes a net reduction in bond spending, it nonetheless reflects a number of new proposals to spend bond funds. These include a proposal to spend $321 million in bond funds (from Propositions 13, 84, and 1E) for flood control projects and levee improvements in the state’s Delta and Central Valley regions. The budget also proposes $49 million in bond funds (from Propositions 84 and 50) for groundwater monitoring, water conservation, and other activities implementing the package of Delta/water–related legislation approved by the Legislature in November 2009. Finally, the budget proposes $23 million (mainly bond funds, but also including special funds) for recreation and fish and wildlife enhancements at State Water Project (SWP) facilities, and proposes reform of related statutes, including the Davis–Dolwig Act enacted in 1961. (We provide an update on the bond resources available for resources and environmental protection programs later in the Resources Bond Issues write–up later in this analysis.)

Summary of Environmental Protection Spending Proposals. Similar to Figure 1, Figure 2 shows spending and fund source information for major environmental protection programs—those programs within the jurisdiction of the California Environmental Protection Agency (Cal–EPA). As Figure 2 shows, the budget proposes a few major spending changes in these programs. Most of the 30 percent reduction for the Air Resources Board (ARB) reflects an anticipated decrease in spending from the Proposition 1B transportation bond for air quality improvements in the state’s major trade corridors. The 10 percent net increase for the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) reflects both a reduction of $98 million in bond–funded local assistance and an increase of $158 million in spending from the Underground Storage Tank Cleanup Fund to pay more claims seeking reimbursement from the fund for costs to clean up leaking tanks. The latter change results from the enactment of Chapter 649, Statutes of 2009 (AB 1188, Ruskin), that temporarily increased the level of the fee that supports the fund.

Figure 2

Selected Funding Sources Environmental Protection Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Department/Board

|

Actual

2008–09

|

Estimated

2009–10

|

Proposed

2010–11

|

Change From 2009–10

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Air Resources Board

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Motor Vehicle Account

|

$113.7

|

$113.1

|

$118.2

|

$5.1

|

4.5%

|

|

Air Pollution Control Fund

|

142.4

|

163.6

|

171.3

|

7.7

|

4.7

|

|

Bond funds

|

3.4

|

501.0

|

229.6

|

–271.4

|

–54.2

|

|

Other funds

|

65.8

|

82.7

|

82.8

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

|

Totals

|

$325.3

|

$860.4

|

$601.9

|

–$258.5

|

–30.0%

|

|

Pesticide Regulation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pesticide Regulation Fund

|

$67.6

|

$65.8

|

$71.0

|

$5.2

|

7.9%

|

|

Other funds

|

2.7

|

3.5

|

8.1

|

4.6

|

131.4

|

|

Totals

|

$70.3

|

$69.3

|

$79.1

|

$9.8

|

14.1%

|

|

Water Resources Control Board

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$38.3

|

$36.7

|

$34.3

|

–$2.4

|

–6.5%

|

|

Underground Tank Cleanup

|

166.2

|

233.1

|

396.1

|

163.0

|

69.9

|

|

Bond funds

|

72.3

|

159.8

|

65.1

|

–94.7

|

–59.3

|

|

Waste Discharge Fund

|

80.6

|

76.2

|

84.4

|

8.2

|

10.8

|

|

Other funds

|

41.5

|

242.4

|

245.7

|

3.3

|

1.4

|

|

Totals

|

$398.9

|

$748.2

|

$825.6

|

$77.4

|

10.3%

|

|

Toxic Substances Control

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$22.2

|

$22.7

|

$23.7

|

$1.0

|

4.4%

|

|

Hazardous Waste Control

|

50.4

|

47.0

|

49.9

|

2.9

|

6.2

|

|

Toxic Substances Control

|

42.5

|

49.9

|

57.3

|

7.4

|

14.8

|

|

Other funds

|

65.2

|

66.8

|

68.4

|

1.6

|

2.4

|

|

Totals

|

$180.3

|

$186.4

|

$199.3

|

$12.9

|

6.9%

|

|

Environmental Health Hazard Assessment

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$7.1

|

$2.2

|

$2.4

|

$0.2

|

9.1%

|

|

Other funds

|

8.1

|

15.5

|

17.2

|

1.7

|

11.0

|

|

Totals

|

$15.2

|

$17.7

|

$19.6

|

$1.9

|

10.7%

|

Largest Budget Solutions Involve New Alternative Revenue Sources. The primary budget–balancing solutions proposed by the Governor in the resources area involve new revenue sources to replace General Fund support for (1) state parks and (2) wildland fire protection and emergency response.

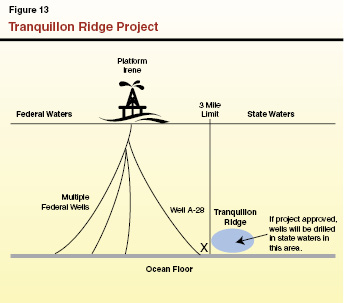

Regarding funding for state parks, the Governor proposes to use $140 million of Tranquillon Ridge oil and gas lease revenues for this purpose in the budget year. In subsequent years, the Governor proposes that these lease revenues be used for the support of state parks.

Regarding funding for wildland fire protection and emergency response, the budget proposes the Governor’s Emergency Response Initiative (ERI), to be implemented together by CalFire, the California Emergency Management Agency (CalEMA), and the Military Department. The ERI is intended to enhance the state’s emergency response capabilities, and would be funded by a 4.8 percent surcharge on all residential and commercial property insurance premiums statewide. The budget proposes that ERI special fund revenues in 2010–11 be used to offset $200 million of the department’s General Fund support for wildland fire protection. In subsequent years, ERI revenues would be used both to create General Fund savings and expand emergency response programs in CalFire and other departments. The General Fund savings in subsequent years—estimated around $219 million—result from ERI revenues being used to replace General Fund support for CalFire’s Emergency Fund and CalEMA’s assistance to local governments.

Other Funding Shifts. The budget proposes to shift $6.4 million of funding for various water quality and water rights regulatory programs from the General Fund to existing fee–based funding sources.

Program Reductions. The budget proposes only a few program reductions as budget–balancing solutions. These include a reduction of $5 million from the General Fund for recreational hunting and fishing programs in DFG.

Continuing the Reorganization of the State’s Recycling and Waste Management Functions. The budget reflects the implementation of Chapter 21, Statutes 2009 (SB 63, Strickland), that combines the functions of the California Integrated Waste Management Board and the Department of Conservation’s Division of Recycling to create the Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery in the Natural Resources Agency as of January 1, 2010. The administration notes that the location of all of the state’s waste management and recycling functions currently in the Natural Resources Agency may not be the appropriate one for each of these functions. Given this, the administration has stated its intent to pursue further changes to the reorganization of these functions. Details of the administration’s proposal were not yet available at the time this analysis was prepared.

Beverage Container Recycling Program Changes. In conjunction with the budget, the Governor has submitted a legislative proposal to implement various programmatic and budgetary changes in the beverage container recycling program. Some of these changes are proposed to take effect several years from now, such as a proposal to incorporate the cost of recycling into the price paid by consumers for beverage containers. Other changes, such as the proposed elimination of several recycling programs and subsidies that the administration contends are unnecessary, would take effect beginning in the budget year.

Where Does the $1.8 Billion Go? As mentioned above, the budget proposes about $1.8 billion from the General Fund for resources and environmental protection purposes, including for general obligation bond debt service. Over the last decade, the level of General Fund support for these purposes has been highly variable—reaching a peak of about $2.6 billion in 2000–01 (when the state’s General Fund condition was particularly healthy), and a low point of about $1 billion in 2003–04.

Debt Service a Major Driver of Resources–Related General Fund Expenditures. Figure 3 shows the departments that are recipients of General Fund monies in the resources and environmental protection area, and the corresponding percentage of their budgets that are funded from the General Fund. As shown in the figure, the General Fund expenditure for resources–related general obligation debt service accounts for $929 million (52 percent) of the $1.8 billion. Expenditures for debt service have increased exponentially over the last decade, reflecting voter approval of several, increasingly larger bond measures. Accordingly, outside of debt service, $871 million of the $1.8 billion from the General Fund directly supports program budgets.

Figure 3

Governor’s Proposed General Fund Expenditures—Resources and Environmental Protection

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

General Fund

Amount

|

As Percentage of Total

Departmental Budget

|

|

Departmental Budgets

|

|

|

|

CalFire

|

$554.1

|

29%

|

|

Department of Water Resources

|

110.1

|

4a

|

|

Fish and Game

|

68.9

|

18

|

|

California Conservation Corps

|

38.0

|

39

|

|

State Water Resources Control

|

34.3

|

4

|

|

Toxic Substances Control

|

23.7

|

12

|

|

Coastal Commission

|

11.2

|

62

|

|

State Lands Commission

|

9.3

|

31

|

|

Delta Stewardship Council

|

5.9

|

12

|

|

Department of Conservation

|

4.8

|

6

|

|

San Francisco Bay Conservation

|

4.1

|

70

|

|

Environmental Health Hazard Assessment

|

2.4

|

12

|

|

Secretary for Environmental Protection

|

1.9

|

11

|

|

Delta Conservancy

|

0.8

|

62

|

|

Secretary for Natural Resources

|

0.7

|

2

|

|

Native American Heritage Commission

|

0.7

|

99

|

|

Tahoe Conservancy

|

0.2

|

2

|

|

Subtotals

|

($871.1)

|

|

|

Agencywide General Obligation Bond Debt Service

|

$929.0

|

|

|

Total General Fund Expenditures

|

$1,800.1

|

|

$871 Million General Fund Proposed for Programs Largely Reflects Fire Protection Costs. As shown in Figure 3, the largest General Fund programmatic expenditure by far in the resources area is for CalFire. The General Fund supports CalFire’s (1) core fire protection program ($523 million), (2) the forest resource management program ($28 million, of which about $11 million is for timber harvest plan review), and (3) the Office of the State Fire Marshal ($3 million). While the General Fund supports 29 percent of the department’s total budget, it supports about 70 percent of its state operations (that is, excluding capital outlay).

The General Fund budget proposed for CalFire for 2010–11 would total $754 million if not for the proposed $200 million funding shift to ERI revenues—a total amount that is substantially higher than the expenditure level a decade ago. Without the proposed funding shift, General Fund expenditures would be 75 percent ($323 million) higher than in 2000–01. There are a number of factors that have driven the department’s fire protection costs upwards so significantly, including increasing labor costs, the growing population in and around wildland areas, and unhealthy forest conditions (particularly in Southern California).

General Fund Support Has Dropped in Other Areas. Apart from its support for fire protection, the General Fund generally supports resources and environmental protection programs at levels that are lower than in 2000–01. For example, from a 2000–01 peak, General Fund support for the Department of Water Resources (DWR) and SWRCB has declined by 74 percent and 66 percent, respectively. For the most part, these declines in General Fund support are not reflected in reduced program levels. Rather, for resources departments, these declines have been largely offset by newly available bond funds and in some cases by revenues from increased fees (such as state park fees). For Cal–EPA regulatory departments, the decline in General Fund support mostly reflects the shifting of funding from the General Fund to regulatory fees.

In spite of the declines in the level of General Fund support for these programs, the General Fund still provides significant support in a number of resources and environmental protection departments outside of CalFire. The $110 million proposed for DWR largely goes for flood management purposes, of which about $51 million is for financing of a flood–related lawsuit settlement. For DFG, the $69 million proposed from the General Fund is for a wide variety of activities, including enforcement, habitat conservation planning, and sport fishing and hunting programs. For SWRCB, the $34 million proposed from the General Fund supports a number of water quality management activities, including basin planning and general cleanup programs.

While relatively small in absolute dollar terms, the General Fund continues to be the primary means of support for a number of resources and environmental protection departments outside of CalFire, including the Coastal Commission and the California Conservation Corps.

Conclusion. While General Fund support for resources and environmental protection programs are declining overall under the Governor’s proposed spending plan, our analysis indicates that there are nonetheless additional opportunities to help the state address its significant General Fund problems. In the sections that follow, we offer a number of specific recommendations for achieving General Fund savings. These reflect both program reductions and opportunities to shift funding from the General Fund to alternative funding sources.

In the analysis that follows, we (1) summarize the package of Delta and other water–related legislation passed by the Legislature in November 2009, (2) discuss how the legislative package impacts the CALFED Bay–Delta Program (CALFED) and its oversight, (3) summarize CALFED expenditures proposed in the budget, (4) review the Governor’s budget proposals explicitly related to the package, and (5) discuss key issues for the Legislature to consider related to financing the legislation.

In 2009, the Governor called a special session to focus on solving water–related problems in the state’s Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta region. The session resulted in the enactment of five pieces of legislation, covering matters related to Delta governance and land use policies, water conveyance, groundwater management, water rights, and a water bond to be placed on the November 2010 ballot. We summarize the major provisions of the legislative package in Figure 4.

Figure 4

The Major Components of the 2009 Water Package

|

Bill

|

Topic

|

Key Provisions

|

|

SBX7 1 Delta Governance

(Chapter 5, Simitian and Steinberg)

|

- Creates Delta Stewardship Council and Delta Conservancy, and reconfigures existing Delta Protection Commission.

- Requires the council to create a management plan for the Delta (incorporating work from existing planning efforts)—the Delta Plan.

- Requires

development of water flow criteria for

Delta ecosystem.

|

|

SBX7 2 Water Bond

(Chapter 3, Cogdill)

|

- Places an $11.1 billion legislative bond on the November 2010 ballot, providing for multiple water program goals.\

- Reactivates California Water Commission (with continuous appropriation authority for new storage projects).

|

|

SBX7 6 Groundwater

(Chapter 1, Steinberg and Pavley)

|

- Requires groundwater elevation monitoring by local agencies (with guidance from Department of Water Resources).

- Bars counties and certain local agencies that do not comply with reporting from receiving state water grants and loans.

|

|

SBX7 7 Water Conservation

(Chapter 4, Steinberg)

|

- Requires a 20 percent reduction in urban per capita water use (and 5 percent overall base reduction—regardless of population) by 2020.

- Requires agricultural water efficiency, and changes certain water recycling and stormwater targets.

|

|

SBX7 8 Water Diversion/Rights

(Chapter 2,

Steinberg)

|

- Requires increased reporting of water use and water diversion; increases certain penalties for water rights violations.

|

|

|

|

Package Addresses Broad Array of Water Issues. As can be seen in Figure 4, the legislative package addressed many fundamental water issues facing the state. For example, the bill related to Delta governance creates the Delta Stewardship Council to manage the state’s interests in the Delta, requires the council to develop a Delta Plan to guide the management of Delta resources by multiple state and local agencies, and creates a state conservancy for the acquisitions of land in the Delta mainly for preservation and restoration of habitat. This bill also requires DFG and SWRCB to provide input to the Delta Plan process on environmental in–stream flow requirements and water quality matters, respectively.

The other bills in the legislative package address water issues that are broader in geographic scope than the Delta. For example, the water conservation bill establishes a statewide target of a 20 percent reduction in urban per capita water use by 2020. (Related conservation provisions also seek greater efficiency in agricultural water use.) Another bill in the package requires increased reporting to the state water boards of water use and unlawful diversions and increases enforcement of water rights at the state level. The groundwater bill requires local agencies to conduct monitoring of groundwater elevations at the basin level, and imposes penalties on counties whose water agencies do not fulfill the monitoring requirements. The legislative package also placed an $11.1 billion general obligation bond measure on the November 2010 ballot. Figure 5 summarizes the bond measure’s allocation of funds among various water–related purposes.

Figure 5

November 2010 Water Bond

Allocation of Funds

(In Millions)

|

|

|

|

Water supply (storage)

|

$3,000

|

|

Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta sustainability

|

2,250

|

|

Conservation and watershed protection

|

1,785

|

|

Regional water supply

|

1,400

|

|

Water recycling and conservation

|

1,250

|

|

Groundwater protection and water quality

|

1,000

|

|

Drought relief

|

455

|

|

Total

|

$11,140

|

Water Bond Not a Financing Mechanism for All Other Components. The water bond, if approved by the voters, could potentially fund some elements of the legislative package (for example, by providing funding for capital improvements that help in meeting the urban water conservation goals). However, the bond issue was not designed to be the financing mechanism for the whole package. For example, other sources of funding will have to be found for the ongoing administrative operations of the new Delta Stewardship Council and the conservancy. As another example, the water bond explicitly does not provide funding for the design, construction, operation, or maintenance of Delta conveyance facilities—facilities involving the movement of water either through or around the Delta. We discuss these financing issues in greater detail later in this analysis.

The CALFED Bay–Delta Program. The CALFED encompasses multiple state and federal agencies that have regulatory authority over water and resource management responsibilities in the San Francisco Bay/Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta region. The objectives of the program are to provide good water quality for all uses, improve fish and wildlife habitat, reduce the gap between water supplies and projected demand, and reduce the risks from deteriorating levees. The program’s implementation has been guided since 2000 by what is referred to as the CALFED “Record of Decision”—a legal, environmental planning document that lays out the roles and responsibilities for each participating agency, sets program goals and milestones, and covers the type of projects to be pursued.

In recent years, the Secretary for Natural Resources has been the lead state agency with responsibility for CALFED program oversight, including overall program planning, performance evaluation, and tracking of the progress of these activities. Accordingly, funding for CALFED was provided from the Secretary’s budget. Through legislative budget actions, the Secretary assumed the responsibility for oversight of CALFED oversight as well as some program responsibilities that were previously carried out by the California Bay–Delta Authority (CBDA). The CBDA, originally created to coordinate implementation of continuing CALFED– and Delta–related programs, was in effect eliminated several years ago (although not eliminated in statute), when the Legislature eliminated its funding and transferred its responsibilities to the Secretary.

The passage of Chapter 5 (Statutes of 2009, 7th Extraordinary Session) in the new water package means that the new Delta Stewardship Council will take the lead role in providing oversight for CALFED. The CALFED program oversight and coordination staff in the office of the Secretary, as well as CALFED fiscal staff in CalFire, are to be transferred to the council along with related funding. In addition, the CBDA was statutorily eliminated and its responsibilities assigned to the new council.

Budget Reflects CALFED Expenditures Across Many Departments. While the new Delta council will take the lead for oversight of CALFED, multiple state agencies will continue to spend money to carry out CALFED activities. The state agencies have estimated the amounts that would be spent for these purposes (as seen in Figure 6), including some additional funding amounts requested in the 2010–11 budget plan. Information about these expenditures continues to be compiled by the Delta Stewardship Council by the reporting of the CALFED budget, which cuts across numerous departments.

Figure 6

Proposed CALFED Budget—State Funds Only

(In Millions)

|

State

|

2010–11

(Proposed)

|

|

Department of Water Resources

|

$206.2

|

|

Department of Fish and Game

|

69.2

|

|

State Water Resources Control Board

|

11.5

|

|

CALFED Bay–Delta Program (Delta Stewardship Council)

|

8.7

|

|

Department of Public Health

|

3.9

|

|

Department of Conservation

|

3.8

|

|

San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission

|

0.1

|

|

Department of Forestry and Fire Protection

|

—

|

|

Total

|

$303.5

|

The Governor’s budget plan proposes a number of major changes in CALFED expenditures. For example, there would be a major increase in funding for SWRCB for, among other purposes, the development of Delta flow standards. A major decline for CALFED activities for DWR does not reflect an actual decline in the level of programmatic activity, but rather reflects the fact that three years’ worth of expenditures (for 2009–10 through 2011–12) were all appropriated in the budget act for the current year.

Time for a Zero–Based Budget for CALFED. In past years, when CALFED and other Delta–related programs activities were at a major crossroads, the Legislature directed the administration to submit a zero–based budget identifying the proposed expenditures of the various state agencies involved in this programmatic area. The intent was to require the administration to justify all CALFED expenditures and thereby enable better legislative understanding of the overall size of the program and how funds were being expended.

Given the Legislature’s new policy direction for the Delta and the recent changes in CALFED program oversight, this is an appropriate time, in our view, for the Legislature to direct the council to submit a similar zero–based budget encompassing all CALFED and Delta–related activities in conjunction with the Governor’s submittal of the 2011–12 budget. The budget should include a workload analysis and the goals for each of the state’s Delta–related investments. The Legislature would then be in a position to eliminate duplicative or unnecessary activities in favor of those that move the state toward the Legislature’s stated policy goals for the Delta.

Budget Proposals Total $118 Million. As shown in Figure 7, a total of $118 million is proposed to implement the new legislative water package in the budget year. There are two major components of the budget package:

- Capital Projects: $52 Million. The budget would allocate $28 million to DWR for the Two–Gates Fish Protection Demonstration Program and $24 million to the Wildlife Conservation Board for Natural Communities Conservation Planning projects. Both projects are supported with existing bond funds. (We discuss our concerns with the Two–Gates proposal later in this analysis.)

- Delta Stewardship Council: $49 Million. The proposed funding would come mainly from existing bond funds and reimbursements from other state agencies (including SWP funds). The budget would for the most part continue funding for CALFED activities at the same level that were supported before their shift from other state agencies.

Figure 7

Governor’s Budget Proposal to Implement the New Legislative Package

(In Millions)

|

State Agency/Major Activities

|

Proposed 2010–11 Expenditures

|

|

Delta Stewardship Council

|

|

- Creation of the Delta Plan, establishment of the Council, continuation of Delta science programs.

|

$49.1

|

|

Department of Water Resources

|

|

- Reactivation of the California Water Commission, groundwater monitoring, water conservation projects, and the $28 million Two–Gates Fish Protection Demonstration Project.

|

35.0

|

|

Wildlife Conservation Board

|

|

- Continuous appropriation authority for Natural Communities Conservation Planning projects.

|

24.0

|

|

State Water Resources Control Board

|

|

- Increased water rights enforcement, new water diversion reporting, Delta Watermaster Program, and water conservation activities.

|

5.4

|

|

Delta Protection Commission

|

|

- Preparation of an economic sustainability plan.

|

2.0

|

|

Delta Conservancy

|

|

- Establishment of the conservancy and early action projects.

|

1.3

|

|

Department of Fish and Game

|

|

- Development of Delta flow criteria.

|

1.0

|

|

Total

|

$117.8

|

The Two–Gates Fish Protection Demonstration Project, which would be jointly funded by the state with the federal government, is designed to install operable gates in the central Delta for fish protection and water supply benefits. The Governor’s budget proposes to revert the $28 million in Proposition 84 bond funding that was (1) originally appropriated for the project in the current year in the new legislative water package and (2) replaced those monies with a new appropriation of Proposition 50 funding in the budget year of the same amount. However, the federal government has put the project on hold due to concerns about a scientific review of the proposal. It is uncertain at this time if and when federal authorities will resume funding of the project.

Two–Gates Project Should Be Put on Hold. We recommend that the Legislature approve the Governor’s proposal to revert the Proposition 84 bond funding for the Two–Gates Fish Protection Demonstration Project. However, we recommend that it not approve at this time the administration’s proposal to appropriate an identical amount of Proposition 50 funding for the project. This project should be put on hold until such time as the federal government again agrees to support the project and the state has had an opportunity to reevaluate the proposal.

In order to provide context for an evaluation of the Governor’s budget proposals for the new Delta Stewardship Council, we believe it is useful to first review two of the Council’s core statutory responsibilities—the development of the Delta Plan and its work in connection with the Bay Delta Conservation Plan (BDCP) process. We discuss both of these responsibilities further below, and then comment on the 2010–11 budget that is proposed for the council.

The Delta Plan. The council’s main statutory assignment is the development and adoption of the Delta Plan, a planning document to guide state and local agency actions within the Delta. The plan is intended to further the state’s goals of ecosystem health and water supply reliability which are to guide the state‘s actions in the Delta. The plan would guide the state’s coordination efforts with other levels of government, and take into account other state Delta planning efforts, including the BDCP process (which we discuss in greater detail below).

The Bay Delta Conservation Plan. As part of its development of the Delta Plan, the council is required to consider the BDCP currently being developed by DWR and a group of stakeholders (including state environmental agencies, local water agencies, and environmental organizations). The council is not required to incorporate the BDCP into the Delta Plan, however, unless certain conditions are met. Specifically, DFG must determine that the BDCP meets the qualifications to be deemed a natural community conservation plan. Also, the BDCP must have been approved as a habitat conservation plan that meets requirements in the federal endangered species law. The BDCP is being developed to create a long–term conservation strategy for the Delta. When complete, the plan would provide the basis for the issuance of endangered species permits necessary to allow operations of both the state and federal water projects in the Delta for the next 50 years.

This BDCP planning process is voluntary. The stakeholders and the departments participating in this planning process are not required to adopt this plan when it is completed. If the BDCP were not adopted, then the state and federal water projects would again be at risk of being held in noncompliance with endangered species laws. These agencies would therefore be required to achieve compliance with endangered species laws by the more traditional regulatory permitting process.

In order to ensure that the Delta Plan and the BDCP mesh well, the council is expected to closely monitor and, to some degree, participate in the BDCP process. However, state law also contemplates that the council will independently review the BDCP and make recommendations as to how it would be implemented.

The Proposed Council Budget. The Governor’s budget proposes a total of $49.1 million and 58 positions for the council for 2010–11. Of these positions, 50 are CALFED positions that would be transferred from various state agencies (mainly the Secretary and CalFire) to the council. Eight positions would be new—the council’s seven–member board and an assistant to the chair. The proposed complement of staff is shown in Figure 8. Most of the council’s funding would come in the form of bond–funded reimbursements ($29.8 million), direct bond appropriations ($9.7 million), and the General Fund ($5.9 million).

Figure 8

Positions Proposed for

Delta Stewardship Council

|

|

|

|

Executive

|

19

|

|

Administration

|

14

|

|

Science

|

12

|

|

Planning and accountability

|

8

|

|

External affairs

|

5

|

|

Total

|

58

|

Contract Funding Proposed. The council budget would provide funding for $42.7 million in contracts with outside contractors and other state agencies. Of that total, $16 million (paid for with reimbursements from DWR) would be earmarked for the development of the Delta Plan. The budget also assumes that the council would contract for a project director (at an as–yet–undetermined amount), who would develop a process and schedule to accomplish the Delta Plan, to make presentations to the council, and to ensure integration of the Delta Plan. Under the Governor’s budget plan, this contracted project director would report to an executive–level staff member at the council.

The council budget would also continue an existing CALFED contract originally established under the Natural Resources Agency for a BDCP liaison at an annual cost of about $159,000. The contractor would coordinate Delta–related activities among various state and federal agencies and the council, as well as manage public and legislative outreach activities on behalf of the council.

Some Budget Modifications Warranted. In general, we believe the council’s budget proposal follows legislative direction regarding the transfer and use of existing resources to establish the council. However, we recommend two modifications to the proposed budget. We find that the work that would otherwise be assigned to a project direction contractor should instead be handled by one or more of the proposed 19 executive–level staff proposed for the council. Accordingly, we recommend reducing the council’s budget by $200,000 (bond funds), our estimate of the approximate annual cost of such a contract.

The proposal to continue the current contract arrangement for a BDCP liaison is also problematic. The current contractor for the council is the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. Contracting with such a major stakeholder of the BDCP could compromise the ability of the council to conduct its BDCP–related work objectively and without the perception that it was being unduly influenced by one party to the BDCP process. Thus, we recommend reducing the council’s budget by $79,000 (bond funds) to eliminate the contract for the remaining six months of the contract (June through December 2010). We believe the liaison functions could likewise be handled by one of the council’s executive–level staff.

How Will Implementation of the Delta Plan Be Financed? The new legislative water package requires that implementation of the Delta Plan to be developed by the council begin by January 2012. However, the water package did not provide a long–term financing plan (the proposed water bond was not designed to fund all components of the legislative package), including for implementation of the Delta Plan. Thus, it is not clear how implementation of a new Delta Plan would be able to proceed in a timely manner as contemplated in the recent legislation.

As we have noted in the past, we believe development of a long–term plan to guide the state’s investments in the Delta is warranted. In the absence of such a plan, it has been difficult for the Legislature to evaluate numerous Delta–related funding requests. The development of a long–term financing plan should await the completion of a number of Delta–related assessments. However, these assessments are now largely complete. The two–year timetable for development and implementation of a Delta Plan makes it all the more imperative that such a long–term financing plan also be developed and put in place.

We also continue to believe that such a financing plan should reflect the implementation of the “beneficiary pays” funding principle, whereby the public and private beneficiaries of a state expenditure pay an appropriate share of costs based on the benefit received. We have elaborated on the analytical arguments for this approach in past analyses of resources issues.

Council Should Develop a Long–Term Financing Plan for Delta Improvements. Based on these findings, we recommend that the Legislature adopt statutory language as a part of the budget directing the council to develop a comprehensive long–term financing plan for state expenditures to implement the Delta Plan in conjunction with the Governor’s 2011–12 budget proposal. The plan should identify a long–term funding strategy to support the ongoing operations of the council and the Delta Conservancy. This plan should be based on the beneficiary pays principle and should clearly delineate public versus private benefits of ongoing state operations expenditures and capital projects reflected in the Delta Plan. If new fees are proposed to carry out actions recommended in the Delta Plan, the fees should be reasonable and proportionate to the benefits directly received by the fee payer. Finally, as we have often recommended in the past, bond financing should be used only for capital projects that have long–term benefits, and for reasonable administrative costs related to those capital projects.

Davis–Dolwig Budget Proposal. The Governor’s budget proposes to spend $22.6 million in bond and special funds for recreation and fish and wildlife enhancements in SWP. The funding is proposed in connection with the state’s 48–year–old law, the Davis–Dolwig Act (Davis–Dolwig), which states the intent of the Legislature that such activities be included in the development of the statewide water system and that the cost of such activities be a state funding responsibility.

The budget also proposes statutory reforms to the act, in part to provide a dedicated funding source for its implementation. Specifically, the Governor proposes a statutory change to provide an ongoing, annual appropriation of $7.5 million from the Harbors and Watercraft Revolving Fund (mainly funded from boating–related fees and gas–tax revenues) to DWR for Davis–Dolwig costs.

The Governor also proposes a statutory clarification to declare that, absent a legislative appropriation, Davis–Dolwig does not obligate the General Fund or DWR to cover costs for SWP–related recreation and fish and wildlife enhancements. In addition, the administration proposes to delete an existing provision of Davis–Dolwig that states the intent of the Legislature to appropriate monies from the General Fund in the annual budget act for these purposes.

Recommend Again That Proposal Be Rejected. The budget proposal is essentially the same one that was submitted last budget cycle and that was rejected by the Legislature. In our 2009–10 budget analysis and subsequent report, Reforming Davis–Dolwig: Funding Recreation in the State Water Project, we reviewed policy and fiscal issues that arise from the way Davis–Dolwig is currently being interpreted and implemented by DWR, and offered our recommendations for legislative action. As we found in our prior analyses, the Governor’s latest proposal does not address a number of major problems that we have identified with the implementation of the act. Moreover, we again find that the administration’s approach improperly limits the Legislature’s oversight role for state expenditures in this area. We recommend that the budget request be denied, and we continue to offer the Legislature an alternative package of statutory reforms to the act.

We first discuss some particular problems we have identified with the Governor’s proposal, before turning to our recommendations for Davis–Dolwig reform.

Inconsistency in Justification for Budget Proposal. The Legislature’s review of this budget proposal is complicated by the department’s inconsistent claims about whether SWP construction projects are being put on hold due to Davis–Dolwig funding problems.

As there is currently no dedicated state funding source for costs allocated to Davis–Dolwig by DWR, the SWP contractors, who pay most of the costs of SWP, have fronted the monies for these costs over many years on the assumption that they would eventually be repaid by the state. According to documents submitted by the department in support of last year’s budget proposal, a lack of a dedicated state funding source for Davis–Dolwig costs has resulted in a situation in which new revenue bonds for SWP construction have been placed on hold, delaying these construction projects. The DWR cited this as a key reason for the adoption of its Davis–Dolwig budget proposals, and made the same statements in meetings with legislative staff and bond counsel. While the department later retracted this statement in legislative budget hearings last April, it has included such statements again as justification for the current budget proposal. These inconsistencies make it difficult for the Legislature to assess the merit of the administration’s budget request.

No Guarantee of Any Recreation and Fish and Wildlife Enhancement Benefits. Instead of providing funding directly to recreation and fish and wildlife enhancements (the fundamental purpose of Davis–Dolwig), the $22.6 million in the Governor’s proposal is to be used to fund a portion of the total annual budget of the overall SWP. This reflects an accounting method adopted by the department in the 1960s whereby total SWP costs are allocated among the project’s beneficiaries. The Department of Finance (DOF) raised concerns about this accounting method as far back as the 1970s. As such, very few physical recreation facilities (for example, boat docks or campgrounds) or fish and wildlife enhancements would actually be provided with the requested funds. Under the administration’s approach, Davis–Dolwig funds would be allocated to pay for such items as an SWP communications system upgrade, an administrative office building, and a pump replacement.

Improper Limits on Legislative Oversight. We are concerned about the proposal to provide authority for ongoing appropriations of funding from the Harbors and Watercraft Revolving Fund (HWRF) without annual review of these expenditures by the Legislature. This approach means that there would continue to be insufficient oversight of the Davis–Dolwig commitments made by DWR and how funds are spent for these purposes. In addition, our analysis indicates that the HWRF has a structural deficit and thus cannot sustain support for these additional funding commitments over time.

Failure to Address Various Problems With Davis–Dolwig Implementation. Finally, we find that the Governor’s proposal fails to address a number of problems that we identified in our previous analyses with the implementation of Davis–Dolwig. Specifically, our previous review found that DWR has interpreted the provisions of the Davis–Dolwig Act broadly, and as a result has:

- Over–allocated total SWP costs to recreation, thereby overstating the appropriate public funding share of SWP costs for recreation.

- Incurred operational costs at some SWP recreation facilities without prior legislative budgetary review.

- Allocated some regulatory compliance costs of SWP operations to Davis–Dolwig and the state, rather than including them in charges to SWP contractors.

- Allowed construction to start on costly capital repairs to the Lake Perris Dam without consideration of other potential legislative priorities for spending for recreation programs.

We recommend that the department report at budget hearings on its inconsistent statements regarding whether the lack of a dedicated funding source for Davis–Dolwig obligations is affecting DWR’s bond–funded projects. The department should resolve whether this is a problem that the Legislature needs to address. If it considers this situation to be an impediment to bond–funded projects, DWR should provide specific information indicating which such projects have been delayed and the extent of such delays.

Regardless of how this issue relating to bond–funded projects is resolved, we maintain our view that fundamental reform of the implementation of Davis–Dolwig is still needed for the reasons discussed below. Accordingly, we recommend that the Governor’s proposal be denied and that the Legislature adopt alternative actions. Specifically, as discussed in detail in our previous analyses, we recommend that the Legislature:

- Amend the act to specify what are eligible costs under Davis–Dolwig (and hence to be paid for with state funds) and what costs are to be met by SWP contractors.

- Direct DWR to evaluate whether SWP facilities mainly used for recreation can be divested from the SWP. Moreover, until this and the cost allocation issues cited above are resolved, we recommend that DWR not commit to any new recreation–focused investments in the SWP.

- Provide clear policy direction on the status of costs previously allocated by DWR to Davis–Dolwig and for which the money has been fronted by the SWP contractors.

Our rationale for these actions is outlined in more detail in our prior reports.

In keeping with the reforms discussed above, we recommend adoption of the Governor’s proposal to delete the current provision of Davis–Dolwig stating the intent of the Legislature to appropriate monies from the General Fund in the annual budget act for SWP–related recreation and fish and wildlife enhancements. Such a change, in our view, would clarify the Legislature’s intention to determine its program funding priorities on a year–to–year basis in the future, including the allocation of any resources for implementation of Davis–Dolwig requirements.

The budget proposes to redirect $1 million of General Fund flood program funding in DWR to create a permanent emergency fund (E–Fund) for flood emergencies. According to the department, this fund would provide expenditure authority to proactively respond to flood emergencies, and allow the department to tap into a newly created special fund for these purposes. Below, we outline the proposal and comment on our concerns about the lack of fiscal controls and basic expenditure criteria for accessing the proposed fund. We also discuss our concerns about how the proposal would undermine legislative oversight of the department’s expenditures.

State’s Role in Flood Emergencies. Under current law and practice, the department responds to local requests for assistance related to flood emergencies. This can be after a flood is in progress, or prior to a flood event when imminent failure of a levee seems likely. The department coordinates as a first–responder the deployment of personnel and flood–fighting equipment, and generally coordinates the activities of various levels of government. When called upon, the department uses the state funding available for flood management to position itself for a response, in coordination with other levels of government and other state emergency response entities (such as Cal–EMA). In most circumstances, the state may declare an emergency which triggers assistance from the federal government to offset some of the expenses of the state.

General Fund Support Proposed for Flood Management Activities. The Governor‘s budget proposes about $40 million from the General Fund for state operations and local assistance for the flood management program (excluding debt–servicing costs for a flood–related lawsuit settlement). This funding would be used by DWR for (1) floodplain management activities, including the identification of land subject to flooding, and encouraging local land use practices that take the existing flood threat into account; (2) management of the Central Valley Flood Protection Board; (3) maintenance of the state–federal system of flood control, including encroachment control and inspection; (4) administration of local flood control subventions; and (5) flood forecasting and natural disaster assistance.

Legislature Previously Augmented Flood Management Expenditures. In recent years, the department indicated that it had substantial unmet funding requirements in the state’s flood control system, particularly with regard to levee capital projects. In the 2005–06 budget, the department proposed a number of increases in funding for these purposes over a three–year period. The Legislature approved each of these budget requests, thereby augmenting the department’s flood management funding authority from General Fund, bond funds, and special funds. General Fund support for flood management baseline activities has increased from about $14 million in 2004–05 to about $40 million in the proposed budget (a 184 percent increase). In addition, bond funding for state operations has increased from less than $10 million in 2004–05 to about $95 million in the proposed budget.

E–Fund Proposal. The department’s budget has been built in the past on the assumption that three flood emergency events will occur each year at a cost to the state of approximately $500,000 per flood event. The department’s activities include providing sandbags, coordinating state flood fighting efforts (including Conservation Corps members), and levee monitoring. However, actual flood emergency events, and the associated costs for the department to respond, vary greatly based on the weather pattern in any given year. The response to a single flood event has sometimes cost the state more than $1 million.

The budget proposes to establish a new $1 million fund, using General Fund resources, which would be used exclusively to respond to imminent flood threats with duration of no more than seven days. The administration would be provided authority to redirect the existing General Fund support for flood management. The Director of DWR could access this new fund, at his or her discretion, to support emergency response activities. Proposed budget bill language would further allow DOF to immediately transfer additional funds (General Fund) to the E–Fund without legislative notification whenever the $1 million appropriation was exhausted.

How E–Fund Fits Within Total Funding for Flood Emergencies. Of the $40 million for flood baseline activities, the department proposes to allocate $12.8 million in General Fund support for flood emergencies, response, and recovery activities, from which $1 million could be redirected by DWR to the new E–Fund. Significant additional funding beyond these resources would be available under the Governor’s budget proposal for flood management purposes. This includes additional expenditures for flood system maintenance, risk notifications, activation of the State–Federal Flood Operations Center, and the conduct of feasibility studies for improvements for the state system of flood control. The department would also be provided $211 million in bond funds to evaluate floodplains as well as to complete flood system improvements.

The department contends that setting up a dedicated funding account for flood emergencies via the E–Fund would improve the likelihood and timeliness of cost recovery from the federal government in flood emergencies. In support of its proposal, the department cites federal law that requires a state to demonstrate that an emergency has exceeded the state’s capacity and resources to respond before it can access federal emergency assistance funding. The department provides that the E–Fund is meant to be a reflection of the state’s commitment of resources to respond to flood emergencies and thus of its capacity to respond to an emergency.

However, it is unclear how the E–Fund, as proposed, would accomplish this goal. Since the fund could be augmented—without restriction—with resources at DOF’s discretion, it is unclear how the fund’s existence could be used to demonstrate to the federal government that an emergency has exceeded the state’s capacity and resources to respond in order to trigger federal assistance.

The administration has not cited any specific instance in which the lack of such an E–Fund structure hindered state access to federal emergency funding. We are not convinced that the department’s E–Fund proposal would have any effect on the state’s ability to access federal emergency funding.

E–Fund Proposal Lacks Sufficient Fiscal Controls. As noted earlier, the administration’s proposal would redirect General Fund monies from the existing flood management program to a new emergency fund. As we also discussed, DOF would then be allowed to replenish the fund at its discretion with General Fund monies, without any prior notification to the Legislature. We find that this type of “revolving door” funding authority could substantially undermine legislative oversight of departmental expenditures and would provide insufficient fiscal controls. (We have similar concerns about an emergency fund for emergency fire suppression.) We further explain our concerns below.

Funding Impacts to Current Programs Unclear. The department has not explained which current flood management activities would be affected by the redirection of resources to the new E–Fund. While the department states that the level of any current programmatic activity would not be reduced, it is not clear how this could be the case if funding formerly available for these activities were now set aside in the E–Fund. In our view, such changes greatly weaken legislative oversight over state spending in this area.

Basic Criteria and Priorities for Expenditures Lacking. The administration has not explained how monies in the new E–Fund would be allocated or prioritized by the department. According to the department, the E–Fund could be accessed simply when the department determined there was an “imminent threat” of a flood. It is unclear, however, whether this means the department could access the funds to deploy personnel and equipment even if the customary process of declaring an emergency has not yet been completed.

Because of the lack of fiscal controls and unclear expenditure criteria to access the proposed new E–Fund, we recommend that the Legislature not approve the proposal. This approach, in our view, would undermine legislative oversight of the department’s expenditures for this important state function while providing no demonstrated improvement in the state’s access to federal emergency funding.

California has been at the forefront of promoting the development of renewable energy sources for many years, as demonstrated by the enactment of a state law commonly referred to as the renewables portfolio standard, or RPS. The state’s RPS law requires specified electricity providers to increase the amount of electricity they acquire from renewable resources, such as solar, geothermal, biomass, or wind power, either from their own power sources or through the purchase of energy from others.

The adoption of renewable energy procurement requirements raises a number of important and complex policy issues. The Legislature has clearly demonstrated its intention to set state policy in this area in statute. Our review finds, however, that the administration is currently spending state funds, and proposing further such expenditures, to develop new renewable energy procurement requirements that circumvent current legislative policy as reflected in state law. We find that such action is (1) premature until and unless the Legislature adopts a new RPS statute and (2) leading to inefficient duplication of efforts by state agencies and wasteful spending.

In the analysis that follows, we review current RPS law, discuss the administration’s recent activity that circumvents that law, and make budget–related recommendations to address this concern.

RPS Standard Now Set at 20 Percent. Current law, as amended in 2006, requires each privately owned electric utility to increase its share of electricity generated from eligible renewable energy resources by at least 1 percent each year so that, by the end of 2010, 20 percent of its electricity comes from renewable sources. State law defines what specific types of energy sources are to be considered renewable for purposes of the RPS requirement. (The RPS requirement also applies to Electric Service Providers [ESPs]—companies that provide retail electricity service directly to customers who have chosen not to receive service from the utility that serves their geographic area.)

Enforcing the RPS. Current law requires the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) to enforce compliance by the private utilities (commonly referred to as investor–owned utilities, or IOUs) and ESPs with the 20 percent RPS. Only IOUs are required to submit plans to the CPUC that describe how they will meet RPS targets at the least possible cost. The RPS law contains provisions that specifically govern how this policy is to be implemented by state officials. For example, the CPUC is prohibited from ordering an IOU or ESP to procure more than 20 percent of its retail sales of electricity from eligible renewable energy resources. As another example, the RPS law caps the costs that an IOU must pay to acquire potentially higher–cost electricity from renewable sources, regardless of the annual RPS targets.

Publicly Owned Utilities Set Their Own Renewable Energy Standards. Current state law does not require publicly owned utilities to meet the same RPS that other electricity providers are required to meet. Rather, current law directs each publicly owned utility to put in place and enforce its own renewable energy standards and allows each publicly owned utility to define the electricity sources that it counts as renewable. No state agency can require a publicly owned utility to comply with renewable energy standards or impose penalties if one fails to meet the renewable energy goals it has set for itself.

Vetoed 2009 RPS Legislation. During the 2009 legislative session, the Legislature passed, and the Governor subsequently vetoed, a package of RPS–related bills. These bills—which included SB 14 (Simitian), AB 21 (Krekorian), and AB 64 (Krekorian)—together would have increased the RPS target for IOUs and ESPs to 33 percent by 2020 and also made publicly owned utilities subject to the same RPS targets as these other electricity providers. In his veto messages, the Governor cited his policy concerns about the Legislature’s approach to meeting a 33 percent RPS, a target which he nonetheless supported. For example, the Governor contended that these bills unduly limited utilities’ use of renewable electricity imported from other Western states to meet California’s RPS targets. Even though the legislation was vetoed, the passage of the 2009 measures demonstrated the Legislature’s continued intention to set policy in this area through the enactment of new statutes.

As discussed below, our review finds that over the last few years, the administration has been involved in a number of activities that, in effect, circumvent the Legislature’s policy direction as reflected in current RPS law.

Governor’s Two Executive Orders. In November 2008, the Governor issued an executive order calling for all providers of retail electricity (thereby including publicly owned utilities) to obtain 33 percent of their electricity from renewable sources by 2020. State government agencies were directed to “take all appropriate actions” to implement this target. In September 2009, after vetoing legislation that would have placed a 33 percent RPS target in statute, the Governor issued another executive order directing ARB to develop a regulation “consistent with” a 33 percent renewable energy target. The executive order indicated that the administration believed that it had the legal authority to establish such regulations under the Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 (commonly referred to as “AB 32”). The ARB currently is working to develop this regulation.

Executive Orders Cannot Replace or Circumvent Lawmaking. In a recent written opinion, the Legislative Counsel advised us that, as a general proposition, the Governor may not issue an executive order that has the effect of enacting, enlarging, or limiting legislation. In the context of the Governor’s September 2009 executive order, we are advised that the ARB may not adopt a renewable energy–related regulation that contravenes, changes, or replaces the statutory requirements of the current RPS law. According to Legislative Counsel, AB 32 does not authorize the ARB to adopt such a regulation. Since current RPS law is very prescriptive in its requirements, this prohibition would severely constrain the ARB in developing its regulation pursuant to the executive order. For example, we are advised by Legislative Counsel that the ARB could not develop a regulation that contravenes the current–law prohibition upon requiring an IOU to procure more than 20 percent of its electricity from renewable sources. Given this legal opinion, in our view it would clearly be inappropriate for the administration to circumvent the existing RPS law by attempting to implement a new renewable energy standard on its own authority.

Planning Activities. Despite these legal constraints, the administration has been involved in various planning activities that assume an RPS target that is different than the one established in current law. For example:

- The ARB’s plan to implement AB 32 (commonly referred to as the AB 32 Scoping Plan) includes a 33 percent RPS as one of its primary measures to achieve the state’s greenhouse gas emission reduction goals.

- Multiple Integrated Energy Policy Reports prepared by the California Energy Commission have evaluated the state’s ability to achieve a 33 percent RPS.

- The Renewable Energy Transmission Initiative planning group (an administration initiative involving multiple state energy and environmental agencies, public and private utilities, and environmental interests, among others) has conducted its planning work and analysis based on the assumption of the imposition of a 33 percent RPS target.

- The CPUC is moving forward with efforts to implement a 33 percent RPS with respect to the private utilities it regulates, through its Long–Term Procurement Plan process.

Administration’s Spending Related to a 33 Percent RPS. Although the Legislature has not approved a budget request related explicitly to the evaluation or implementation of a 33 percent RPS, the administration has spent significant resources for these purposes and has plans to continue this spending. Figure 9 summarizes these ongoing and proposed expenditures, which would total $4 million in 2010–11 under the Governor’s budget proposal.

Figure 9

Administration’s 33 Percent

RPS–Related Spending

(In Thousands)

|

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

|

Air Resources Board

|

|

|

|

Base budget

|

$1,900

|

$750

|

|

Proposed budget request

|

—

|

—

|

|

California Public Utilities Commission

|

|

|

Base budget

|

$553

|

$423

|

|

Proposed budget request

|

—a

|

2,800

|

|

Totals

|

$2,453

|

$3,973

|

The ARB estimates that it will spend $1.9 million (from the Air Pollution Control Fund) in the current year and $750,000 in the budget year to develop RPS–related regulations pursuant to the Governor’s executive order and the AB 32 Scoping Plan. No specific funding requests for this purpose have been submitted to the Legislature for the budget year. For CPUC, the 2009–10 Governor’s Budget proposed a $322,000 increase for the commission to begin the process of implementing a 33 percent RPS. The Legislature denied this budget request, finding that the proposal was premature, pending enactment of the enabling legislation to establish the 33 percent RPS. However, the CPUC has continued to conduct planning and analysis for a 33 percent RPS, and estimates that it will spend $553,000 (from the Public Utilities Reimbursement Account) in the current year for this purpose ($423,000 for staff costs and $130,000 for consulting fees).

The CPUC plans to spend $423,000 for staffing costs for these same purposes in the budget year from its existing budget resources. In addition, the Governor’s budget includes requests totaling $2.8 million (from the Public Utilities Commission Utilities Reimbursement Account [PUCURA]) for CPUC to implement a 33 percent RPS in 2010–11. These requests include $1.8 million for seven personnel–years in staffing to implement a 33 percent RPS, and $1 million annually (for each of the next five years) to contract for RPS program evaluation and technical assistance.

Administration’s Spending Plans Are Problematic. The administration’s spending plans discussed above are problematic for a couple of reasons. First and foremost, the expenditures by CPUC and ARB to develop RPS–related regulations are premature given the current statute authorizing a 20 percent RPS. This regulatory activity should not occur until or unless the Legislature enacts a 33 percent standard, and only then should be implemented in a fashion consistent with any policy parameters for a revised RPS that have been established by the Legislature.

The ARB’s expenditures to develop a higher RPS are particularly problematic. This is because ARB is delving into a subject matter—renewable energy procurement—that is both outside its area of statutory responsibility and outside its area of technical expertise. The ARB is spending significant funding to work with CPUC to come up to speed on the subject matter of renewable energy procurement. In our view, this is an inefficient use of state resources. These ARB activities also constitute an inappropriate duplication of effort, given that CPUC plans to move ahead at the same time to implement a 33 percent RPS that would apply to the entities that it regulates.

Analyst’s Recommendations. Given that the administration’s spending plans are both premature and an inefficient and duplicative use of resources, we recommend that the Legislature take the following actions to remedy this situation. Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature:

- Deny CPUC’s budget request for an additional $2.8 million (from PUCURA) for RPS–related activity in the budget year.

- Reduce CPUC’s PUCURA appropriation (Item 8660–001–0462) by an additional $423,000—the amount the commission anticipates spending from its base budget to implement a 33 percent RPS in the budget year.

- Reduce ARB’s Air Pollution Control Fund appropriation (Item 3900–001–0115) by $750,000—the amount the board anticipates spending from its base budget to develop a renewable energy standard regulation in the budget year.

- At budget hearings, specifically direct CPUC and ARB to immediately cease spending funds for the purpose of developing a new renewable energy standard or similar requirement absent the enactment of legislation that authorizes such activities.

The California Energy Commission (CEC) is charged with the duty of issuing permits for large thermal power plants in the state. Over the past decade, the commission has seen a significant increase in the number of applications for the siting of new power plants—a trend that is expected to continue. In 2003, the Legislature enacted both a siting application fee and an annual compliance fee to partially support the CEC’s siting and compliance activities, with electricity ratepayer funds covering the balance of these costs.

In the analysis that follows, we evaluate the current funding structure for the siting program, and offer our recommendations to revise the process. Our recommendations serve two purposes: (1) to more accurately reflect the direct benefits received from the program by power plant developers and operators and reduce the disproportionate cost burden imposed on the state’s electricity ratepayers and (2) address current backlogs in the program and facilitate more timely permitting of such facilities.