Over the last several years, the state has deferred payments to school districts as a way to achieve significant Proposition 98 savings. Since 2007–08, 42 percent of the K–12 Proposition 98 solution has come from deferrals (with almost 46 percent coming from program reductions and 12 percent from funding swaps). Relying on deferrals has allowed the state to achieve significant one–time savings while simultaneously allowing school districts to continue operating a larger program by borrowing or using cash reserves. As the magnitude and length of payment deferrals have increased, however, school districts have found fronting the cash required to continue operating at a higher programmatic level increasingly difficult. As part of his 2011–12 budget plan, the Governor continues to rely heavily on payment deferrals. His one major budget proposal for K–12 education is a $2.1 billion deferral. In this report, we track the state’s increased use of deferrals, discuss the advantages and disadvantages of deferrals, and highlight several other major factors the Legislature should consider as it decides whether to approve additional K–12 deferrals.

State law requires that General Fund payments be made to school districts using a “5–5–9” schedule, with 5 percent of annual payments made in July and August and 9 percent of total payments made each month thereafter. Nonetheless, school districts have not received funding according to this schedule due to payment deferrals adopted in recent years. Figure 1 lists all of the state’s existing Proposition 98 deferrals along with the new deferral the Governor proposes. Below, we briefly review each of the deferrals the state has authorized over the last decade. (For more background information on general cash management issues affecting school districts, please see the “Cash Management” section of our February 2009 report, 2009–10 Budget Analysis Series: Proposition 98 Education Programs.)

Figure 1

Inter–Year Deferrals of K–12 Education Payments

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Deferrals

|

Amount

|

|

Existing as of 2007–08

|

$1,103

|

|

Enacted in February 2009 Budget (to begin in 2008–09)

|

|

|

Retire Home–to–School Transportation deferral

|

–$53

|

|

Shift some K–12 revenue limit and categorical payments from February to July

|

2,000

|

|

Shift K–3 Class Size Reduction payment from February to July

|

570

|

|

Increase size of existing K–12 June–to–July deferral

|

334

|

|

Subtotal

|

($2,851)

|

|

Enacted in July 2009 Budget (to begin in 2009–10)

|

$1,679

|

|

Enacted in October 2010 Budget Package (to begin in 2010–11)

|

|

|

Increase size of existing K–12 June–to–July deferral

|

$500

|

|

Increase size of existing K–12 May deferral (likely paid in September)

|

800

|

|

Increase size of existing K–12 April deferral (likely paid in September)

|

420

|

|

Subtotal

|

($1,720)

|

|

Proposed in Governor’s January Budget (to begin in 2011–12)

|

$2,064

|

|

Total Inter–Year Deferrals

|

$9,418

|

|

Share of K–12 Proposition 98 Program Paid Late

|

21%

|

First Deferrals Used to Mitigate Effects of Midyear Cut. The state first began relying on deferrals in 2001–02. After facing a large midyear budget deficit due to the dot–com bust, the state was forced to reduce spending in the middle of 2001–02. Rather than make programmatic K–12 reductions in the middle of the year, the state deferred $1.1 billion in K–12 payments from June to July 2002 in order to achieve 2001–02 budget savings. The state used deferrals to minimize the programmatic disruption on school districts and families during the midst of the school year (as staffing and assignment decisions already had been made). The action implicitly recognized that school districts have few options to achieve midyear savings other than to drain their reserves or lay off staff (and current law prevents school districts from laying off teachers in the middle of the school year).

Initial Deferrals Only Delayed Payments a Few Weeks. Although the state was able to count $1.1 billion in savings by adopting the deferrals, this shift had little impact on school district finances. Given the deferrals moved payments only from late June to early July, districts had to wait only a few additional weeks to receive their funding. The 2001–02 deferrals highlight their initial appeal—the state could claim budget savings with little to no effect on school district finances or operations.

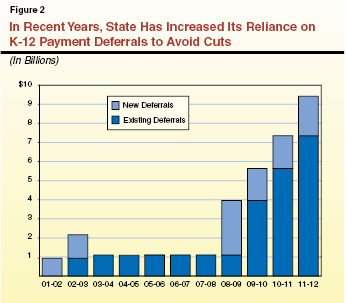

Deferrals a Major Proposition 98 Solution Over Last Three Years. As shown in Figure 2, the state has increasingly relied on deferrals to achieve budget solutions. In 2008–09, the state delayed $2.9 billion in K–12 payments to deal with a large midyear decline in General Fund revenues. In 2009–10 and 2010–11, however, the state adopted K–12 payment deferrals at the beginning of the fiscal year—knowing that even if all revenue assumptions in the enacted budget held, the state still would not have enough resources to support the desired K–12 programmatic level. In 2009–10, the state adopted a $1.7 billion deferral and, in 2010–11, it adopted a new deferral totaling $1.7 billion. Over the three–year period, the state adopted a total of $6.3 billion in new payment deferrals. (In response to the large increase in deferrals, the state created a deferral waiver process in 2010–11. Districts now can be exempt from the June to July payment deferrals if they can demonstrate that they would be unable to meet their financial obligations due to the delayed payments. Applications to receive a waiver must be submitted by April 1 and are limited to a total of $100 million annually.)

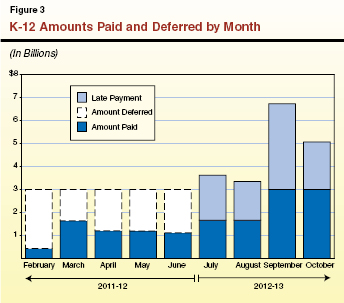

Recent Deferrals Delay Payments for Up to Five Months, New Deferrals Likely to Delay Even Longer. Unlike the initial deferrals that only delayed payments by a few weeks, the more recent deferrals shifted payments by several months, placing a significant cash burden on school districts. The longest deferral—a shift of payments from February to July—delays payments for five months. Under the Governor’s 2011–12 plan, funds could be shifted even longer—likely from March to October (a seven–month delay). As Figure 3 shows, under the Governor’s plan, almost two–thirds of K–12 payments originally made February through June would now be paid in the following year. In total, $9.4 billion in K–12 payments would be paid late.

Given the Governor’s new $2.1 billion deferral proposal, the Legislature is likely to grapple with whether it should approve additional borrowing to sustain a higher level of K–12 programmatic support. To help the Legislature in making this determination, we discuss the advantages and disadvantages of relying on deferrals below.

Provides One–Year State Savings. Deferrals are appealing because they provide one year of state savings (in the initial year of a deferral) without requiring school districts to reduce their spending. If the deferrals are ongoing (as has been the case), they have no fiscal effect in subsequent years (either savings or cost) for the state. This is because for any given fiscal year the added cost of paying for the amount from the prior fiscal year is exactly offset by the savings from deferring the same amount into the next fiscal year. In essence, a payment deferral allows the state on a one–time basis to authorize a programmatic level for school districts that it cannot afford in that year.

Minimizes Need for Immediate Programmatic Reductions. Since a deferral does not reduce school districts’ programmatic spending, school districts can continue to operate as if no reduction has occurred. That is, if the state adopts a payment deferral rather than a cut, districts can continue to operate a higher level of program despite the one–time reduction in state spending. For example, under the Governor’s 2011–12 proposal, the $2.1 billion K–12 deferral would allow schools to spend about $350 per student more than if a $2.1 billion cut were adopted. Given this benefit, deferrals could be particularly appealing in 2011–12, as school districts will no longer have federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funds available and could face their most difficult year (from both a fiscal and programmatic perspective) since the beginning of the recession.

Authorizes Programmatic Level State Cannot Afford. On the other hand, the major problem with using payment deferrals as a budget solution is that they authorize school districts to operate a program the state cannot afford. Although deferrals help mitigate budget reductions in the short term, they also create a large ongoing out–year obligation. That is, repaying for prior–year deferrals becomes first call on current–year monies. This out–year cost pressure persists until the state “doubles–up” funding in order to retire the deferrals. The use of deferrals also makes the state’s budget information both less meaningful and less transparent. Since deferrals are not reflected as an expenditure in the year in which operations are authorized, the state’s annual budget displays are not truly reflective of the state’s commitments. In addition, deferrals are only helpful to the extent school districts can access cash (internally or externally) in the short term to cover costs. If lenders stop loaning sufficient cash, the state would need to provide an additional $7.3 billion to avoid school district programmatic reductions.

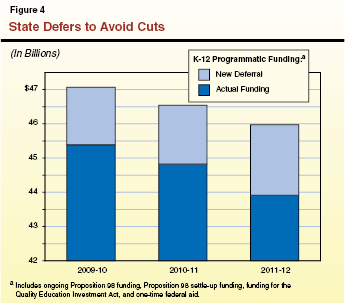

Results in Cuts the Following Year Unless Funding Increases Sufficiently to Cover Programmatic Costs. Though a deferral prevents programmatic cuts on a one–time basis, programmatic cuts are avoided the following year only if year–to–year growth in funding is sufficient to pay for the deferred payments as well as support all existing programmatic costs. If growth is insufficient to cover these costs, then the state would need to authorize a new deferral to avoid a year–to–year reduction. This is essentially the situation that has occurred over the past few years. Figure 4 shows the K–12 “funding level” versus the “program level” (which includes payment deferrals) for 2009–10, 2010–11, and 2011–12 (as proposed by the Governor). In 2009–10, due to a new payment deferral, the state was able to authorize a program level of $47.1 billion even though it only provided $45.4 billion in actual funding. In 2010–11, school districts would have experienced a notable decline in programmatic funding (from $47.1 billion to $44.8 billion), but the state adopted another deferral such that the actual year–to–year decline was small. Similarly, in 2011–12, the state would need a new deferral to continue supporting the higher programmatic level. In short, the state has been continuing to use new deferrals to support programs in excess of available state funding.

Places Increasingly Heavy Cash Burden on School Districts. By deferring payments, the state shifts the burden of fronting cash onto school districts, along with potential borrowing costs. To access cash, districts can use existing budget reserves or special funds (although drawing down reserves also results in a loss of earned interest). If internal resources are insufficient, districts can try to borrow from private lenders, the County Office of Education, or the County Treasurer. If districts borrow from other agencies, they are responsible for covering all transaction and interest costs. The current interest rates are at historically low rates, so the costs of borrowing has not been particularly burdensome for districts. These costs, however, could increase notably in the future, thereby increasing the financial burden being placed on districts.

Districts Must Use Odd Accounting and Borrowing Practices. To maintain higher levels of programmatic spending, school districts must use seemingly questionable accounting and borrowing practices. According to general accounting principles, entities should only count revenue as a “receivable” for a given fiscal year if the funds will be paid within 60 days of the end of the fiscal year. Under the Governor’s proposal, many deferred payments would not be made until September or October, up to 90 or 120 days after the close of the fiscal year. In addition, many school districts must now borrow twice a year to meet short–term cash flow needs, often using funds from one loan to pay for the previous loan. Although they do not violate any laws (and some are actually codified in statute), these practices show the level to which districts have been stretched as a result of lengthy deferrals.

In addition to the advantages and disadvantages discussed above, the Legislature should consider several other issues when deciding whether to adopt new K–12 payment deferrals. In particular, the Legislature should take into account the budget decisions made by districts over the past year, the potential impact of a new deferral, the general fiscal health of school districts, and the timing of state budget decisions on school districts’ ability to respond.

Governor’s Proposal Provides Significantly More Than Districts Initially Budgeted for 2010–11. State law requires school districts to submit their locally approved budgets to their county offices of education for fiscal review by July 1. As a result, school districts often finalize their local budgets before the state has adopted its budget. In years when the state budget is likely to be adopted late, school districts typically base their final budget decisions on the Governor’s May Revision. This was the case in 2010–11. With the state not adopting its 2010–11 budget until October 2010, school districts built their budgets based upon the May Revision level—which reflected a programmatic cut of 7 percent and included no new deferrals. Despite these developments, the state chose in October to include a $1.7 billion deferral in its 2010–11 budget package rather than make reductions as proposed in the May Revision. Just as the state could not afford the higher 2010–11 programmatic level resulting from the $1.7 billion deferral, the Governor’s 2011–12 plan (even with his proposed revenue augmentations) does not have adequate revenue to support the higher programmatic level. Hence, he relies on a new $2.1 billion deferral. Without either deferral, however, school districts would be receiving funding in 2011–12 roughly sufficient to support the programmatic level in effect when they began the 2010–11 school year. That is, if one uses the beginning of the 2010–11 school year as a point of reference, a new deferral would not be needed to meet the Governor’s desired goal of keeping programmatic funding flat year over year.

New Deferral Likely to Lead to Disconnect Between “Authorized” and “Actual” Programmatic Support. Though a new deferral is not needed to sustain the same level of K–12 programmatic support in 2011–12 as in effect when the 2010–11 school year began, the Legislature still is likely to seriously consider the Governor’s 2011–12 deferral proposal. To help guide the Legislature in its decision as to whether to adopt a new deferral, we recently sent a survey to districts asking how they likely would respond to a new deferral in 2011–12. Almost half (44 percent) of responding districts reported that one of the ways they would respond would be to cut/not restore operations. This is very likely because these districts believed that would have exhausted internal and external sources of short–term borrowing and they would not be able to front sufficient cash to support as high a programmatic level. As a result, the state in essence would be claiming a higher level of programmatic support statewide than would actually exist in the field. In other words, the level of authorized programmatic support at the state level would no longer be an accurate reflection of actual programmatic support at the school district level.

Consider District Financial Health. When deciding whether to adopt additional deferrals, the Legislature also should take into consideration the overall financial condition of school districts. Based on first interim reports submitted to the California Department of Education during fall 2010, 103 school districts (or roughly 1 in 10) had a negative or qualified certification, which suggests that they might have difficulty meeting their financial obligations over the next two or three years. Qualified and negative school districts also will have a more difficult time borrowing from the private market to meet cash flow needs.

Assess Whether Increase in Deferral Waiver Authority Is Justified. Given the troubled financial conditions of many school districts and the likelihood that the state will adopt additional deferrals or budget reductions, more districts may be at risk of insolvency in the coming year. One way to help ease the burden on struggling districts is to allow districts to be exempt from certain deferrals if they are at risk of insolvency. As mentioned previously, the state established a deferral waiver process in 2010–11 to exempt school districts from the June to July deferral. The Legislature should review the demand for deferral exemptions in 2010–11 (applications are due by April 1) and determine if additional waiver authority is needed for 2011–12.

Send Signals Early to School Districts. Finally, were a significant amount of the administration’s proposed budget solutions not to be approved, the state very likely would need to rely on additional reductions, including some in K–12 education, to balance its budget. Regarding the tax package alone, if it were not to be approved, the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee would drop by roughly $2 billion. Given the uncertainty with state solutions and the timing of school districts’ own budget requirements, the Legislature should try to send signals early to districts regarding the extent to which additional reductions might be needed to balance the 2011–12 budget. The more information that is available to school districts about potential state actions, the better prepared they will be to respond to potentially larger–than–anticipated reductions.