(Note: In a letter dated February 16th, 2011

we responded to questions regarding our analysis of the California Redevelopment Association’s study of the economic effects of redevelopment included in this report.)

Californians pay over $45 billion in property taxes annually. County auditors distribute these revenues to local agencies—schools, community colleges, the counties, cities, and special districts—pursuant to state law. Property tax revenues typically represent the largest source of local general purpose revenues for these local agencies.

More than 60 years ago, the Legislature established a process whereby a city or county can declare an area to be blighted and in need of redevelopment. After this declaration, most property tax revenue growth from the “project area” is distributed to the city or county’s redevelopment agency, instead of the other local agencies serving the project area.

During the early years of California’s redevelopment law, few communities established project areas and project areas typically were small—usually 10 to 100 acres. Over the last 35 years, however, most cities and many counties have created project areas and the size of project areas has grown—several cover more than 20,000 acres each. Partly as a result of this expansion in number and size of project areas, redevelopment’s share of total statewide property taxes has grown six fold (from 2 percent to 12 percent of total statewide property taxes). In some counties, local agencies have created so many project areas that more than 25 percent of all property tax revenue collected in the county are allocated to a redevelopment agency, not the schools, community colleges, or other local governments.

California’s expansive use of redevelopment has engendered significant controversy. Advocates of the program contend that it is a much needed tool to promote local economic development in blighted urban areas. Program critics counter that redevelopment diverts property tax revenues from core government services and increases state education costs, and that the scale and location of many project areas bear little relationship to the program’s intended mission.

The Governor’s 2011–12 budget includes a plan for dissolving redevelopment agencies and distributing their funds (above the amounts necessary to pay outstanding debt) to other local agencies. To assist the Legislature in reviewing this proposal, this report explains how redevelopment redistributes and uses property tax revenues. The report then evaluates redevelopment, summarizes and assesses the Governor’s proposal, and offers suggestions for legislative consideration.

After property owners pay property taxes, county auditors distribute them to schools and other local agencies in the county. While the laws controlling allocation of the base 1 percent property tax rate are complex, they can be summarized in three steps.

- Step 1. Every year, each local agency receives the same amount of property tax revenues that it received the year before.

- Step 2. Each local agency receives a share of any growth (or loss) in property tax revenues that occurred within its jurisdiction. (The share an agency receives is based on historical factors and is often referred to as its “AB 8 share” after the 1979 law that established the formula to create these shares.)

- Step 3. Each city and county receives additional revenues (shifted from the schools’ property tax revenues) to offset its losses from the state’s reduction of the local sales tax rate (the “triple flip’) and vehicle license fee (the “VLF swap”). Each city and county receives funds equal to its current sales tax losses and its 2004 VLF losses, adjusted by the agency’s change in assessed valuation since 2004.

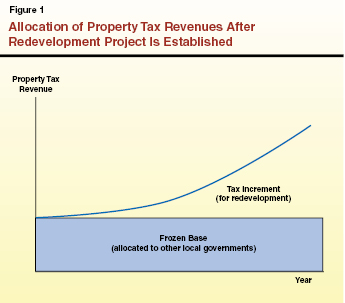

If a community establishes a redevelopment project area, the amount of property tax revenues flowing to local agencies serving the area is frozen. K–14 districts, the counties, cities, and special districts continue to receive all of the property tax revenues they had received up to that point. This amount is known as the frozen base.

As shown in Figure 1, all of the growth in property taxes in the project area—over the frozen base—is allocated to the redevelopment agency as tax–increment revenue. In other words, local agencies receive the same amount of property tax revenues they received in the past, but none of the growth.

This redirection of property tax revenues lasts for the life of the redevelopment project—typically 50 years, although some older projects have longer lifetimes. (A nearby box provides some information about how this element of California’s redevelopment law compares with other states with similar programs.)

Viewed from the county auditor’s perspective, Steps 1 and 3 of the property tax allocation system (described previously) stay the same. Step 2, however, is revised so that the auditor distributes all revenue growth in the project area to the redevelopment agency—and not to other agencies.

|

California’s redevelopment law provides for a 50–year diversion of all property tax revenue growth in redevelopment areas. This feature of California law is somewhat unusual in comparison with other states with redevelopment programs (often called “tax increment financing” elsewhere in the country). Many other states, for example, authorize some local agencies to “opt out” of the redevelopment program (that is, to not have their property tax revenue growth included in the diversion) or statutorily exclude school property taxes from the program. Still other states limit to shorter periods how long redevelopment agencies may redirect property taxes. California redevelopment law partially mitigates the fiscal effect of its program design by requiring redevelopment agencies to “pass through” a portion of the revenues diverted from other local agencies. |

State law allows redevelopment agencies to use property tax increment revenues to finance a broad array of projects. Redevelopment agencies typically use these revenues—often in conjunction with private developer funds or other governmental resources—to finance capital improvements, land and real estate acquisitions, affordable housing, and planning and marketing programs.

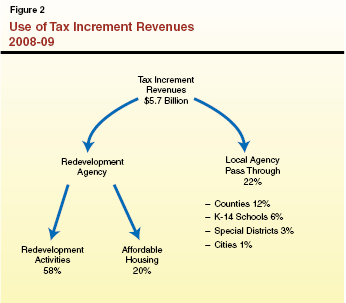

As shown in Figure 2, however, not all of the property tax increment revenue is available for broad redevelopment purposes. State law requires redevelopment agencies to spend 20 percent of tax–increment funds for low– and moderate–income

housing. Additionally, in order to partially offset the loss of growth in property tax revenues for other local agencies, state law requires redevelopment agencies to “pass through” to other agencies a portion of their tax–increment revenues.

Statewide, redevelopment agencies pass through an average of about 22 percent of their property tax increment revenues. This pass–through percentage varies across project areas, based on the date the redevelopment project area was formed and other factors. (Redevelopment law was amended in 1993 to establish a statewide formula for sharing property tax increment revenue derived from newly created redevelopment project areas. This formula increases the pass–through share over time. In redevelopment areas established prior to 1993, redevelopment agencies and affected local agencies typically negotiated the amount of revenues contained in a pass–through agreement.)

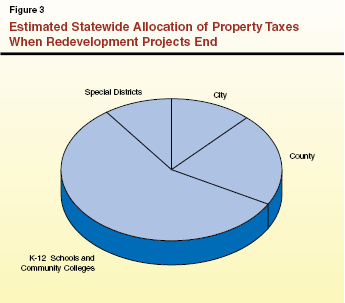

After a redevelopment project ends, the county auditor distributes all of the revenues that formerly were considered “tax increment revenues” to local agencies in the area. Each agency serving the area receives a portion of the revenues as determined by its AB 8 share. From a county auditor’s standpoint, these revenues do not trigger additional allocations pursuant to Step 3 (the triple flip and VLF swap adjustments) because the end of a redevelopment project does not affect a local agency’s sales tax revenue losses or calculation of the VLF swap amount. As shown in Figure 3, we estimate that schools and community colleges would receive over half of the revenues made available after a redevelopment project ends. While very few redevelopment projects have ever ended to date, a significant number are expected to end within next 15 years.

The Governor’s proposal to end redevelopment raises fundamental questions regarding the extent to which this program benefits the state. To help the Legislature evaluate redevelopment programs, we reviewed available academic studies on their effectiveness. In addition, because published academic articles on California redevelopment programs are rare, we reviewed studies on other states’ tax–increment financing districts—the common term for redevelopment finance nationwide. Finally, we reviewed state agency and other reports on redevelopment performance producing affordable housing and compared the key elements of accountability for redevelopment and other programs. Figure 4 summarizes our findings, which we discuss in more detail below.

Figure 4

Redevelopment: Findings From Research and Studies

|

Positive

|

|

Flexible tool that can improve targeted areas.

|

|

Helps build affordable housing.

|

|

Negative

|

|

No evidence that redevelopment increases overall regional or statewide economic development.

|

|

Diverts revenues from other local governments and increases state education costs.

|

|

Has limited transparency and accountability.

|

Under the powers granted to them in redevelopment law, cities can target areas within their jurisdiction for economic development. (Although counties also form redevelopment agencies, we focus on cities in this report because they account for more than 90 percent of active redevelopment areas.) While cities have other tools to encourage economic development, establishing a redevelopment area is one of the easiest ways to raise significant sums. Most other local options for generating revenue for economic development—such as issuing general obligation bonds or establishing a business improvement district—require approval by voters and businesses and/or residents to pay increased sums. Redevelopment requires neither.

The use of redevelopment has improved many areas of the state through the revitalization of downtown and historic districts, improvements in public infrastructure, and increased commercial investment. Many of these investments have improved the quality of life for residents in specific areas. In terms of quantifiable measures, most of the academic literature indicates that property values within project areas increase more than comparable areas within a region. This is not surprising as we would expect areas receiving public subsidies to outperform those that do not.

As mentioned above, state law requires redevelopment agencies to deposit 20 percent of their tax increment revenues into low– and moderate–income housing funds and spend these funds on affordable housing. Redevelopment agencies are authorized to spend housing funds to acquire property, rehabilitate or construct buildings, provide subsidies for low– and moderate–income households, or preserve public subsidized housing units at risk of conversion to market rates. While other federal, state, and local programs also provide funds for affordable housing efforts, redevelopment represents one of the largest funding sources.

In terms of housing production efficiency and effectiveness, we are not aware of any studies that compare redevelopment agencies’ results in producing affordable housing with other financing approaches. We note, however, that state audits and oversight reports frequently conclude that a significant number of redevelopment agencies take actions that have the effect of reducing their housing program productivity, including:

- Maintaining large balances of unspent housing funds. (The Department of Housing and Community Development’s most recent report indicates that the agencies collectively had an unencumbered balance of more than $2.5 billion.)

- Using most of their housing funds for planning and administrative costs.

- Spending housing funds to acquire land for housing, but not building the housing for a decade or longer.

While redevelopment leads to economic development within project areas, there is no reliable evidence that it attracts businesses to the state or increases overall regional economic development. Instead, the limited academic literature on this topic finds that—viewed from the perspective of an entire city or region—the effect of this program on property values is minimal. That is, redevelopment may cause some geographic shifts in economic development, but does not increase the overall amount of economic activity in a region. Studies in Illinois and Texas, for example, found that their redevelopment programs did little more than displace commercial activity that would have occurred elsewhere in the region.

In addition to examining the effect of redevelopment on property values in a region, some research has focused on the effect of this program on jobs. The independent research we reviewed found little evidence that redevelopment increases jobs. That is—similar to the analyses of property values—the research typically finds that any employment gains in the project areas are offset by losses in other parts of the region. We note that one study, commissioned by the California Redevelopment Association, vastly overstates the employment effects of redevelopment areas (please see nearby box).

|

The California Redevelopment Association (CRA) recently circulated a document asserting that eliminating redevelopment agencies would result in the loss of 304,000 jobs in California. We find the methodology and conclusion of CRA’s report to be seriously flawed. In our view, it vastly overstates the economic effects of eliminating redevelopment and ignores the positive economic effects of shifting property taxes to schools and other local agencies.

The CRA’s job loss estimate is based on a consultant’s report using data from 2006–07. To estimate the number of jobs resulting from redevelopment agencies, the report calculated the total expenditures on construction projects completed within a sample of redevelopment areas for 2006–07, as well as for any projects completed outside the area with agency participation. Based upon that sample, the report then estimated the total construction expenditures for redevelopment agencies statewide in 2006–07 and used a computer model to calculate through various multipliers the total effect of those expenditures on the state’s economy and employment. The report concluded that redevelopment was responsible for the creation of about 304,000 full and part–time jobs in 2006–07. Therefore, the CRA asserts that the elimination of redevelopment would result in the loss of 304,000 jobs.

To our knowledge, the consultant’s study has never been subjected to any independent or academic scrutiny. Our review indicates that the report has three significant flaws that cause it to vastly overstate the net economic and employment effects of redevelopment agencies.

Assumes Redevelopment Agencies Participate in All Project Area Construction. The study’s calculation of construction expenditures includes all construction completed in a redevelopment project area in 2006–07, even if the redevelopment agency was not a participant. We find implausible the report’s implicit assumption that no construction with solely private financing would have occurred within a redevelopment area in the absence of the redevelopment agency. This is particularly true, given the large geographic scale of California redevelopment project areas. In our view, it is likely that much of the new business or residential construction (and the associated jobs) would have occurred independently of the redevelopment agency.

Assumes Private and Public Entities Participating in Redevelopment Agency Projects Would Not Invest in Other Projects. Most redevelopment agency projects include significant financing from private investors or other public agencies. By asserting that all of the jobs associated with redevelopment construction would be lost if redevelopment agencies were eliminated, the CRA implicitly assumes that these private and public partners would not invest in other economic activities in the state. The report provided no explanation for this assumption that the existing private capital and public agency grants would remain unused without redevelopment agency participation. In most cases, we would expect developers, investors, and public agencies to find alternative projects to pursue—either within the redevelopment area or elsewhere in the state.

Assumes Other Local Agencies’ Use of Property Tax Revenues Would Not Yield Economic Benefits. Under the Governor’s proposal, the property tax revenues that currently support redevelopment would flow over time to schools and other local agencies in the county. By asserting that all of the jobs associated with redevelopment construction would be lost if redevelopment agencies were eliminated, the CRA implicitly assumes that these other local agencies’ use of property tax revenues would not result in any economic activity. The report provided no explanation for this assumption. In our view, spending by school districts, counties, and other local agencies also would yield significant economic and employment benefits. |

Redevelopment agencies receive over $5 billion of tax increment revenues annually. Lacking any reliable evidence that the agencies’ activities increase statewide tax revenues, we assume that a substantial portion of these revenues would have been generated anyway elsewhere in the region or state. For example, a redevelopment agency might attract to a project area businesses that previously were located in other California cities, or that were planning to expand elsewhere in the region. In either of these cases, property taxes paid in the project area would increase, but there would be no change in statewide property tax revenues.

To the extent that a redevelopment agency receives property tax revenues without generating an overall increase in taxes paid in the state, the agency reduces revenues that otherwise would be available for local agencies to spend on non–redevelopment programs, including law enforcement, fire protection, road maintenance, libraries, and parks.

The fiscal effect of redevelopment on K–12 schools and community colleges, in contrast, is somewhat different. This is because, under California school finance laws, the state is responsible for ensuring that each district receives sufficient total revenues (from state and local sources) to meet a statutorily defined funding level. Thus, property tax revenues redirected to redevelopment agencies usually are replaced by increased state aid. In this way, K–14 districts are largely unaffected by redevelopment, but state education costs increase.

Fiscal Effect on Local Agencies and the State. Based on the available evidence, we estimate that the amount of property tax revenues diverted from non–school local agencies (principally, counties and special districts) is about $1.5 billion annually net of pass–through payments. We further estimate that the increased cost to the state associated with the diversion of K–14 district property taxes is over $2 billion annually net of pass–through payments. In addition to these amounts, we note that some K–14 districts with unusually high property tax revenues per pupil (“basic aid” districts) also sustain property tax revenue losses associated with redevelopment, but we are not able to estimate the magnitude.

Redevelopment agencies lack some of the key accountability and transparency elements common to other local agencies. Specifically, unlike other local agencies, redevelopment agencies can incur debt without voter approval. Redevelopment agencies can also redirect property tax revenues from schools and other local agencies without voter approval or the consent of the local agencies.

In addition, although redevelopment programs are authorized in state law and increase state costs, redevelopment programs lack the key accountability elements that are common to state–supported local assistance programs. Specifically, no state agency reviews redevelopment economic development activities or ensures that project areas focus on the program’s mission. We also note that use of redevelopment is not limited to communities with low property wealth—some of California’s most affluent cities have declared large sections of their jurisdictions “blighted.”

The administration proposes to dissolve the state’s redevelopment agencies. Tax increment revenues that currently go to redevelopment agencies would be redirected to retire redevelopment debts and contractual obligations and to fund other local government services. In place of redevelopment, the administration indicates that it will propose a constitutional amendment to allow local voters to approve tax increases and general obligation bonds for economic development purposes by a 55 percent majority. While many of the details of the Governor’s proposal still are under development, we outline its key elements below.

Redevelopment agencies currently have the authority to issue debt, own and lease property, and enter into other long–term contractual obligations. While enactment of the Governor’s proposal as urgency legislation would prohibit redevelopment agencies from entering into additional obligations, existing debts would need to be paid. The Governor proposes to transfer the responsibility for managing these obligations to a local successor agency—most likely the city or county that authorized the redevelopment area, guided by an oversight board. The successor agency would receive the redevelopment agency’s existing balances and future shares of tax increment revenue to pay the agency’s debts. Any funds above the amounts needed to pay these debts would be used for other purposes as described below. The one exception is that the successor agencies would shift any unspent redevelopment housing funds to local housing authorities to use for low– and moderate–income housing.

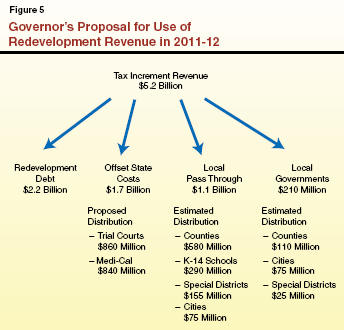

The Governor’s budget assumes that tax increment revenues from dissolved redevelopment areas would be approximately $5.2 billion in 2011–12. (The most recent report from the State Controller’s Office identifies $5.7 billion of redevelopment tax increment revenues in 2008–09. The Governor’s lower tax increment estimate reflects its assumptions regarding the decline of property values statewide.) Of this amount, an estimated $2.2 billion would be used to pay redevelopment debts and obligations during the first year. As outlined in Figure 5, the remainder of the tax increment revenues ($3 billion) would provide funding to local governments and offset state General Fund costs. The Governor’s proposal would continue to provide redevelopment’s existing pass–through payments to local agencies. It would also offset $1.7 billion in state Medi–Cal and trial court costs and distribute $200 million to cities, counties, and special districts in proportion to these agencies’ AB 8 shares of the property tax.

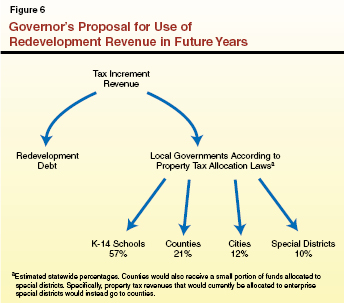

Beginning in 2012–13, any property tax revenues remaining after the successor agencies pay redevelopment debt would be distributed to other local governments in the county. Instead of offsetting state costs or continuing pass–through payments as in 2011–12, distributions of these revenues to local governments generally would follow provisions in existing law. One exception is that property taxes that otherwise would be distributed to enterprise special districts (primarily fee–financed water and waste disposal districts) would be allocated instead to counties. As shown in Figure 6, we estimate more than half of the remaining revenue would be distributed to schools. (The exact allocation of property tax revenues, however, varies significantly across the state.) As redevelopment debts are repaid over time, the amount of revenue available to local governments would steadily increase.

While the Governor’s plan would phase out the existing redevelopment system, it also proposes a constitutional amendment to allow local voters to approve tax increases and general obligation bonds for economic development purposes by a 55 percent majority. At this time, details on this portion of the proposal are not available. As we understand it, cities and counties would retain the powers granted to them under redevelopment law except for the use of property tax increment revenue. In the place of tax increment revenue, the proposal would lower the voter threshold for other financing mechanisms that local governments could use to pursue economic development activities that are currently carried out by redevelopment agencies.

In our view, the Governor’s proposal merits consideration. The proposal places the responsibility to pay for local economic development activities with the level of government benefiting from these policies. The proposal also heightens local accountability for its economic development policies and provides local governments increased general purpose revenues. Finally, the proposal would make a significant contribution towards helping the state address its serious fiscal difficulties in 2011–12. We discuss these advantages, as well as some additional considerations related to the proposal, below.

Redevelopment agencies determine the types of projects they undertake. Decisions regarding spending tax increment revenues—to remedy local infrastructure problems, provide amenities for an auto mall, or subsidize business relocation—are made at the local level. In addition, the research on tax increment financing indicates that it provides localized economic benefits, but does not necessarily increase statewide economic development.

Given these factors—local control over the use of tax increment funds and local benefits—we see little reason for the state to continue its financial support for this program. The Governor’s proposal adheres to a key policy principle that, whenever possible, beneficiaries should pay for services that do not have larger societal benefits.

Local residents and elected officials can best assess the advantages and disadvantages of raising new funds for economic development activities versus shifting funds from other government programs. Under the current system, however, local residents and most elected local officials do not have a role in making these decisions. This is because a redevelopment agency’s decision to form a project area can divert property tax revenues from other agencies without their consent or voter approval. The agency forming a project area also does not have to confront the tradeoffs associated with diverting property tax revenues from its local schools because the state backfills virtually all of these property tax losses. Ending state–assisted redevelopment would require individual communities to confront the full policy implications of funding economic development within their borders, thereby improving transparency and accountability.

Under the Governor’s proposal, schools, counties, special districts, and cities would receive increased property tax revenues. While existing property tax increment revenues are restricted to redevelopment purposes, local governments would have the flexibility to direct these new revenues to their highest priority programs, including public safety, education, health, or social services. Local governments also could elect to use these increased funds for economic development activities.

The proposal would help address the state’s 2011–12 budget problem by offsetting state General Fund costs for Medi–Cal and trial courts by $1.7 billion. While there is little policy rationale for using property taxes permanently for these purposes, we think this one–time use is reasonable in recognition of the magnitude of the state’s prior–year subsidies for redevelopment.

At the time this brief was prepared, the administration was still developing the statutory provisions to implement its proposal. While we cannot provide the Legislature with a detailed assessment of the proposed plan, we highlight below three issues that merit the Legislature’s consideration.

Early Plan Complicated School Funding and Property Tax Allocation Systems. Early versions of the Governor’s plan provided a special allocation system for the additional property tax revenues to schools. Instead of being allocated as property taxes to K–14 districts where the revenues were generated, the administration’s plan allocated these revenues to K–14 districts countywide as a supplement to their existing funds. In our view, this approach does not make sense and would further complicate the already complicated K–14 district finance and property tax allocation systems. This approach also would increase state costs over the long term (relative to current law) because the state would not receive the financial relief associated with the expected expiration of redevelopment projects. The state also would forgo considerable ongoing state savings because the increased K–14 property taxes would not offset the state’s spending for schools. In our view, any property tax revenue from the former redevelopment areas—above the amounts needed to pay existing debt—should be allocated as property taxes pursuant to existing laws. Should the Legislature wish to provide increased support for K–14 districts or to modify the AB 8 property tax allocation system, it could do so separately.

Few Other Options for Ongoing Redevelopment Relief. In some ways, the Governor’s proposal is similar to many previous actions of the Legislature. Specifically, ten times over the last two decades the Legislature has required redevelopment agencies to shift funds to schools, thereby partly mitigating the state’s increased education costs associated with redevelopment. In 2009–10, for example, the Legislature required redevelopment agencies to shift $2 billion of redevelopment funds to schools over two years. The voter’s recent approval of Proposition 22, however, prohibits the Legislature from enacting these types of revenue shifts in the future. Thus, the Legislature has few options for mitigating the major ongoing costs of redevelopment other than dissolving the program. In the future, the Legislature could consider creating an alternative, more targeted, economic development program.

Dissolving Redevelopment Will Be Complicated and Disruptive. Program changes of this magnitude inevitably pose administrative, policy, and legal difficulties. Ending redevelopment, a program that California local governments have used for decades, will not be an exception. Many communities have significant numbers of people and projects currently funded through redevelopment revenues, as well as plans for additional redevelopment expenditures over the coming months. In addition, a significant portion of redevelopment agency funds are committed to the payment of bonded indebtedness, and three voter approved measures—Proposition 18 (1952), Proposition 1A (2004), and Proposition 22 (2010)—contain provisions limiting the state’s authority to shift property taxes and/or redirect tax increment revenues. Drafting a plan for local governments to carefully unwind their redevelopment programs and successfully navigate the many legal, administrative, and financial factors will be complex. The Legislature will need to weigh the costs and benefits of dissolving redevelopment agencies versus the costs and benefits of other major budget alternatives.

Given the significant policy shortcomings of California’s redevelopment program, we agree with the Governor’s proposal to end it and to offer local governments alternative tools to finance economic development. Under this approach, cities and counties would have incentives to consider the full range of costs and benefits of economic development proposals.

In contrast with the administration’s proposal, however, we think revenues freed up from the dissolution of redevelopment should be treated as what they are: property taxes. Doing so avoids further complicating the state’s K–14 financing system or providing disproportionate benefits to K–14 districts in those counties where redevelopment was used extensively. Treating the revenues as property taxes also phases out the state’s ongoing costs for this program and provides an ongoing budget solution for the state.

Ordinarily, we would recommend that the state phase out this program over several years or longer to minimize the disruption an abrupt ending likely would engender. Given the state’s extraordinary fiscal difficulties, however, the Legislature will need to weigh the effect of this disruption in comparison with other major and urgent changes that the state would need to make if this budget solution were not adopted.