In 2011, the state enacted several bills to enact a wide–ranging "realignment," shifting several state programs and a commensurate level of revenues to local governments. Perhaps the most significant programmatic change implemented as part of the 2011 realignment was realigning to county governments the responsibility for managing and supervising certain felon offenders who previously had been eligible for state prison and parole. This report provides an update on the status of realignment, reviews changes proposed by the Governor, and make several recommendations designed to promote the long–term success of realignment. Our recommendations are summarized below.

Create Reserve Fund for Revenue Growth to Promote Financial Flexibility. We recommend modification of the administration's proposed realignment funding account structure. While we find that the proposed structure is significantly improved over the current–year account structure, it could be further improved by adding a reserve account into which all unallocated revenue growth would be deposited. Counties would have flexibility to manage these resources in ways that best meet their local priorities while still meeting federal program requirements where those exist.

Design Ongoing Allocation Formula to Be Responsive to Future Changes. We recommend creating a formula for allocating the funds dedicated to the realignment of adult offenders among the state's 58 counties in a way that would be responsive to changes in local demographics and crime–related factors. Specifically, we recommend implementing—perhaps phased in over a couple of years—a formula relying on two factors: (1) at–risk population ages 18 through 35 and (2) felony dispositions. In so doing, county allocations would be adjusted to better respond to underlying trends in population and criminal activity that can vary by county and over time.

Reject Governor's Proposal for Additional Year of Funding for Community Correctional Plans (CCPs). We recommend rejecting the administration's proposal to provide counties with a second year of planning and training funding totaling $8.9 million. The provision of this funding had merit in the current year when counties had only a few months to begin implementing realignment. While local realignment responsibilities will increase in the budget year as more offenders come onto county caseloads, counties will have hundreds of millions of dollars in additional realignment revenues from which to draw, thereby reducing the need for the state to provide General Fund assistance.

Utilize New Board to Support Public Safety Through Technical Assistance and Local Accountability. We recommend that the administration report at budget hearings regarding the responsibilities of the Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC), a board created as part of the realignment legislation and given the mission of providing technical assistance to counties and promoting local accountability. Despite the clear intention that BSCC play a central role in supporting the successful implementation of realignment over the long run, the administration has not made any proposals on how that mission will be fulfilled.

In 2011, the state enacted several bills to "realign" to county governments the responsibility for managing and supervising certain felon offenders who previously had been eligible for state prison and parole. This report, which is the first of a two–part series examining the impacts of the 2011 realignment on California's criminal justice system, focuses on how realignment has impacted local governments. Specifically, we provide an update on the status of that realignment which became effective October 1, 2011, and review several realignment–related proposals made by the Governor as part of his 2012–13 budget plan. Finally, we offer several recommendations related to those proposals, as well as other recommendations designed to better ensure the long–term success of the realignment of adult offenders.

Several times over the last 20 years, the state has sought significant policy improvements by reviewing state and local government programs and realigning responsibilities to a level of government more likely to achieve good outcomes. As part of the 2011–12 budget package, the state enacted such a reform by realigning funding and responsibility for adult offenders and parolees, court security, various public safety grants, mental health services, substance abuse treatment, child welfare programs, adult protective services, and California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) to counties along with funding to support these programs. We discuss this major shift of responsibility in greater detail below.

Revenues Shifted to Local Governments

To finance the new responsibilities shifted to local governments, the 2011 realignment plan reallocated $5.6 billion of state sales tax and state and local vehicle license fee (VLF) revenues in 2011–12. Specifically, the Legislature approved the diversion of 1.0625 cents of the state's sales tax rate to counties. The administration projects this diversion of sales tax revenues to generate $5.1 billion for realignment in 2011–12, growing to $6.2 billion in 2014–15. In addition, the realignment plan redirects an estimated $462 million from the base 0.65 percent VLF rate for local law enforcement grant programs. Finally, the realignment plan shifted $763 million on a one–time basis in 2011–12 from the Mental Health Services Fund (established by Proposition 63 in November 2004) for support of two mental health programs included in the realignment. Figure 1 illustrates how the total revenue allocated for realignment is projected by the administration to grow over the next several years.

Figure 1

Revenues for Realignment

(In Millions)

|

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

|

Sales tax

|

$5,107

|

$5,320

|

$5,748

|

$6,228

|

|

VLF

|

462

|

496

|

492

|

492

|

|

Proposition 63

|

763

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Revenues

|

$6,332

|

$5,816

|

$6,240

|

$6,720

|

The revenues provided for realignment are deposited into a new fund, the Local Revenue Fund 2011, which includes 8 separate accounts and 13 subaccounts to pay for the realigned programs (see Figure 2). For 2011–12 only, the realignment legislation established various formulas to determine how much revenue is deposited into each account and subaccount. The legislation also contains some formulas and general direction to determine how the funding is allocated among local governments. In addition, the legislation limits the use of funds deposited into each account and subaccount to the specific programmatic purpose of the account or subaccount, with no provisions allowing local governments flexibility to shift funds among programs.

Program Responsibilities Shifted From State to Local Government

The realignment package includes $6.3 billion in realignment revenues in 2011–12 for court security, adult offenders and parolees, public safety grants, mental health services, substance abuse treatment, child welfare programs, adult protective services, and CalWORKs. Figure 3 lists each of the realigned programs, as well as the Governor's projected level of funding provided to the counties for the transferred program responsibilities over the next several years.

Figure 3

Governor's Budget Proposed Expenditures for 2011 Realignment

(In Millions)

|

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

|

Adult offenders and parolees

|

$1,587

|

$858

|

$1,016

|

$950

|

|

Local public safety grant programs

|

490

|

490

|

490

|

490

|

|

Court security

|

496

|

496

|

496

|

496

|

|

Pre–2011 juvenile justice realignment

|

95

|

99

|

100

|

101

|

|

EPSDT

|

579

|

544

|

544

|

544

|

|

Mental health managed care

|

184

|

189

|

189

|

189

|

|

Drug and alcohol programs

|

180

|

180

|

180

|

180

|

|

Foster care and child welfare services

|

1,562

|

1,562

|

1,562

|

1,562

|

|

Adult Protective Services

|

55

|

55

|

55

|

55

|

|

CalWORKs/mental health transfer

|

1,105

|

1,164

|

1,164

|

1,164

|

|

Unallocated revenue growth

|

—

|

180

|

444

|

989

|

|

Totals

|

$6,332

|

$5,816

|

$6,240

|

$6,720

|

Shift of Adult Offenders the Most Significant Policy Change of Realignment. The most significant policy change created by the 2011 realignment is the shift of responsibility for adult offenders and parolees from the state to the counties. This shift can be divided into three distinct parts: the shift of lower level offenders, the shift of parolees, and the shift of parole violators. We discuss each in detail below.

- Lower Level Offenders. The 2011 realignment limited which felons can be sent to state prison, thereby requiring that more felons be managed by counties. Specifically, sentences to state prison are now limited to registered sex offenders, individuals with a current or prior serious or violent offense, and individuals who commit certain other specified offenses. Thus, counties are now responsible for housing and supervising all felons who do not meet that criteria. The shift was done on a prospective basis effective October 1, 2011, meaning that no inmates under state jurisdiction prior to that date were transferred to the counties. Only lower level offenders sentenced after that date came under county jurisdiction.

- Parolees. Before realignment, individuals released from state prison were supervised in the community by state parole agents. Following realignment, however, state parole agents only supervise individuals released from prison whose current offense is serious or violent, as well as certain other individuals—including those who have been assessed to be Mentally Disordered Offenders or High Risk Sex Offenders. The remaining individuals—those whose current offense is nonserious and non–violent, and who otherwise are not required to be on state parole—are released from prison to community supervision under county jurisdiction. This shift was also done on a prospective basis, so that only individuals released from state prison after October 1, 2011, became a county responsibility. County supervision of offenders released from state prison is referred to as Post–Release Community Supervision and will generally be conducted by county probation departments.

- Parole Violators. Prior to realignment, individuals released from prison could be returned to state prison for violating a term of their supervision. Following realignment, however, those offenders released from prison—whether supervised by the state or counties—must generally serve their revocation term in county jail. (The exception to this requirement is that individuals released from prison after serving an indeterminate life sentence may still be returned to prison for a parole violation.) In addition, individuals realigned to county supervision will not appear before the Board of Parole Hearings (BPH) for revocation hearings, and will instead have these proceedings in a trial court. Before July 1, 2013, individuals supervised by state parole agents will continue to appear before BPH for revocation hearings. After that date, however, the trial courts will also assume responsibility for conducting revocation hearings for state parolees. These changes were also made effective on a prospective basis, effective October 1, 2011.

Additional Changes to Assist Counties to Manage Realigned Offenders

The 2011 realignment legislation made several other changes designed to facilitate the successful implementation of the shift of adult offenders to local responsibility. First, it required each county to develop a CCP that identified the county's approach to managing the realigned offenders it was projected to receive. The legislation required a group made up of corrections, law enforcement, judicial, and behavioral health officials to develop each county's plan, which was then submitted to that county's board of supervisors for approval. The 2011–12 budget provided $7.9 million (General Fund) to counties for the development of CCPs.

Second, the realignment legislation also created a new state department, the BSCC. The BSCC was created by removing the Corrections Standards Authority (CSA) from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), where it currently resides. In addition, BSCC will have responsibility for administering some local criminal justice grant responsibilities that currently reside with the California Emergency Management Agency (CalEMA). The BSCC will be operative beginning July 1, 2012 and, in addition to the existing missions of CSA and CalEMA, will have the added responsibility of providing state level oversight of, and technical assistance to, the local corrections system. The BSCC board will be made up of 12 members, with half of the members representing local governments and agencies, and the other half representing other aspects of the state and local criminal justice system.

Third, the realignment legislation provided counties with some additional options for how to manage the realigned offenders. The legislation included provisions allowing for "split sentences," a new sentencing option that allows a judge to sentence a felon to both jail and community supervision. This is somewhat different than what prior law allowed, where a judge usually sentenced someone to either jail or probation. In addition, the legislation allows county probation officers to return offenders who violate the terms of their community supervision to jail for up to ten days, which is commonly referred to as "flash incarceration." The rationale for using flash incarceration is that short terms of incarceration when applied soon after the offense is identified can be more effective at deterring subsequent violations than the threat of longer terms following what can be lengthy criminal proceedings.

Fourth, the realignment legislation provided additional financial resources for counties. This included $1 million provided to three associations—the California State Association of Counties, California State Sheriffs' Association, and Chief Probation Officers of California—for statewide training efforts related to the implementation of realignment. In addition, the Legislature made changes to accelerate the availability of existing state funding for jail construction. Specifically, the Legislature approved expedited release of about $600 million in jail construction funding that had originally been authorized under Chapter 7, Statutes of 2007 (AB 900, Solorio) but not yet awarded. (Chapter 7 provided for $1.2 billion in lease revenue bond authority for the construction of local jail facilities.)

Revenue Projections Close to Original Projections. We last updated our realignment revenue projections last fall for our publication

The 2012–13 Budget: California's Fiscal Outlook. At that time, we projected that realignment revenues were on track with what the administration originally estimated at the time the 2011–12 budget was adopted. The administration's current revenue estimates are somewhat lower but still project sufficient revenue growth to cover the expansion of realignment programs over the next few years. We will continue to update our revenue estimates periodically.

Population Impacts Close to Original Projections. Based on our conversations with the administration and county representatives, the number of new offenders on county caseloads due to realignment appear to be fairly close to what the administration projected when the realignment legislation was enacted. While the total caseload impacts of realignment may be close to original projections, there may be some variation across counties, depending on local factors such as sentencing and supervision decisions and the number of parole revocations.

Development of CCPs in Most Counties. We have found that 47 of the state's 58 counties have completed a CCP as required by law. It is unclear why some counties have not completed their CCPs, but they will continue to receive their realignment allotments even in the absence of an approved plan. The CCPs that have been completed vary in the amount of detail provided, as well as what information is included. The most common elements included in the CCPs are estimates of the number of offenders to be realigned to the county, proposed strategies for managing these offenders, and a proposed expenditure plan. In reviewing the CCPs, we found that 33 CCPs included some level of detail on how the counties planned to allocate their realignment funds to manage their new offender population. While there is considerable variation in the strategies counties plan on employing, on average these plans allocated spending in the following ways:

- 38 percent to the sheriff's department, primarily for jail operations;

- 32 percent to the probation department, primarily for supervision and programs;

- 11 percent for programs and services provided by other agencies, such as for substance abuse and mental health treatment, housing assistance, and employment services;

- 9 percent for other services, including district attorney and public defender costs;

- 10 percent set aside in reserve or undesignated (reduced to 2 percent if San Diego, which set aside more than half of its allocation, is excluded).

We would note that these percentages are somewhat imprecise given the variation and lack of fiscal detail in some CCPs. For example, some CCPs do not specify which agency is to provide a particular program or service (such as substance abuse treatment)—making it unclear if the service would be provided through the probation department or another county agency.

Handoff of Offenders From State to County Supervision Generally Smooth. Based on our conversations with county representatives, the transition of inmates released from prison at the end of their terms to community supervision by counties has generally gone well. Counties report that they usually receive information on the offenders to be released well before their actual release dates. Also, to assist the transition process, CDCR has designated someone at each state prison to be the contact person for counties when they have questions or problems related to someone scheduled to be released. Counties report that this has made it significantly easier to manage problems quickly.

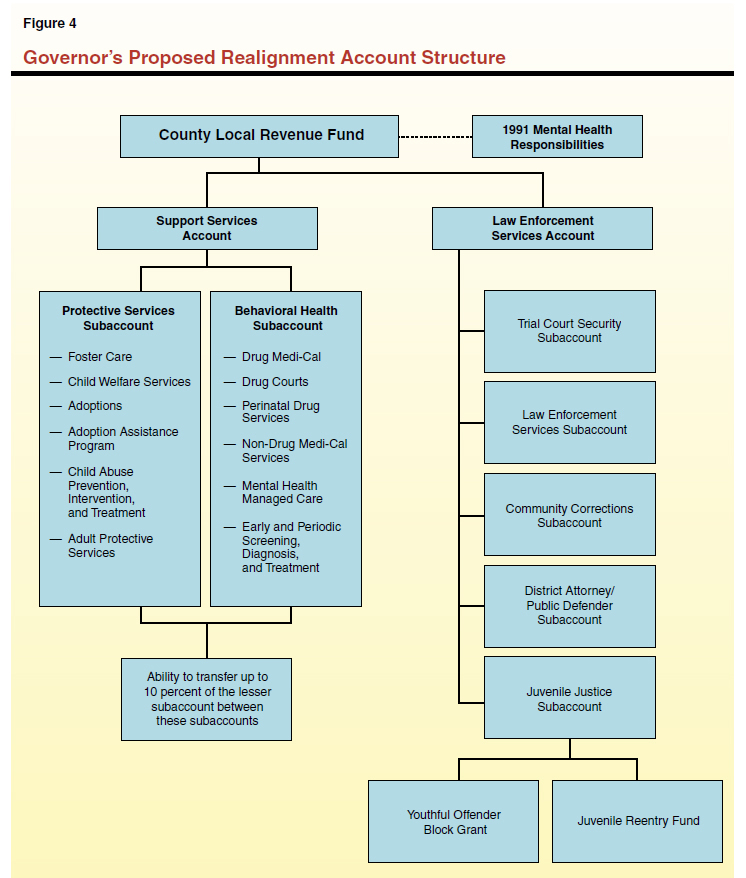

The Governor proposes a couple of changes to the 2011 realignment. However, at the time this analysis was prepared, the administration had not yet released specific trailer bill language revising the 2011 realignment funding system. Specifically, the Governor is proposing some changes to how funding is allocated in future years. These changes include a somewhat simplified structure of accounts and subaccounts. This modified structure is shown in Figure 4. It has two main differences from the existing realignment account structure. First, the Governor's proposal significantly reduces the number of accounts and subaccounts for health and human services programs so that nearly all of those programs would be funded from just two subaccounts (rather than from 11 subaccounts). Counties would also be provided fiscal flexibility to transfer some of the funding—equal to an amount of up to 10 percent of the smaller of the two subaccounts—between these two particular subaccounts. The administration does not propose similar changes to the criminal justice accounts for the budget year, but suggests that similar flexibility to shift funding among law enforcement subaccounts should be provided to counties beginning in 2015–16.

Second, the Governor proposes that, generally, any unallocated growth in realignment revenues—estimated at $180 million in 2012–13—be allocated proportionately among all of the accounts and subaccounts. The administration is proposing, however, that child welfare funding increase by $200 million over the coming years and federally mandated programs receive priority for funding if warranted by caseloads and costs.

In addition, the Governor's budget for 2012–13 provides counties with $8.9 million from the General Fund for CCPs and training, as was similarly done in the 2011–12 budget. Specifically, the proposed budget includes $7.9 million in grants to counties to update CCPs for 2012–13 and $1 million to the three statewide associations to facilitate training related to realignment.

While the 2011 realignment appears to be progressing largely as intended over its first few months, we believe there are still some outstanding issues to be addressed. In this section, we raise concerns with the Governor's proposal for how to distribute the unallocated revenue growth, the absence of a proposal for how to allocate realignment dollars dedicated for the adult offender realignment among counties, and the Governor's proposal to provide counties with $8.9 million in one–time funding. In addition, we are concerned that the BSCC does not have well–defined responsibilities and that the formula for a state grant for county probation departments has not been updated to account for realignment.

Distribution of Unallocated Revenue Growth Should Not Be Done Proportionally

As described above, the Governor has proposed a revised and somewhat simplified account structure for realignment. In general, we think the proposed changes are an improvement of the current–year structure because the revised structure has the potential to provide counties with more financial flexibility to shift some funding around to address local needs and priorities, at least for most of the health and human services programs in 2011 realignment.

We are concerned, however, with the Governor's proposal to distribute the unallocated revenue growth proportionally among the program accounts and subaccounts. In effect, each county would get the same overall share of the unallocated revenue growth as it does of the allocated realignment funds, with all of that revenue growth designated for specific accounts. The rationale for this approach is that it would ensure that each account and subaccount receives at least some share of any revenue growth so that no single program or set of programs could be allocated a disproportionate share of the funding in any county.

The problem with the Governor's proposed approach is that it leaves counties with little flexibility to focus their resources towards their local priorities based on county–specific caseloads, costs, and preferences. For example, the proposed approach could limit a county's ability to dedicate a greater share of revenue towards a specific program that is growing faster or for which there is local demand for greater services. In addition, the proposed approach is problematic because it reduces county incentives to manage their programs efficiently. In other words, a county would have less fiscal incentive to control program costs if that program is getting dedicated funding regardless of factors that actually drive funding need such as caseloads.

An alternative approach would be to have the unallocated revenue growth funding go into a reserve account and allocated among counties on a per capita basis. Under this option, each county would have flexibility to spend its share of the revenue growth as it chooses based on local preferences and priorities.

No Specified Ongoing County Allocations For Realignment of Offenders

As discussed above, the allocation of realignment dollars among counties is identified in statute for 2011–12 only. Allocations for at least the budget year need to be determined before the end of the current fiscal year. At the time this report was prepared, the administration had not yet proposed an allocation formula for future years. Based on our conversations with the administration and various local stakeholder groups, it appears that the administration is hoping to achieve some consensus among counties around an allocation formula to which all counties can agree.

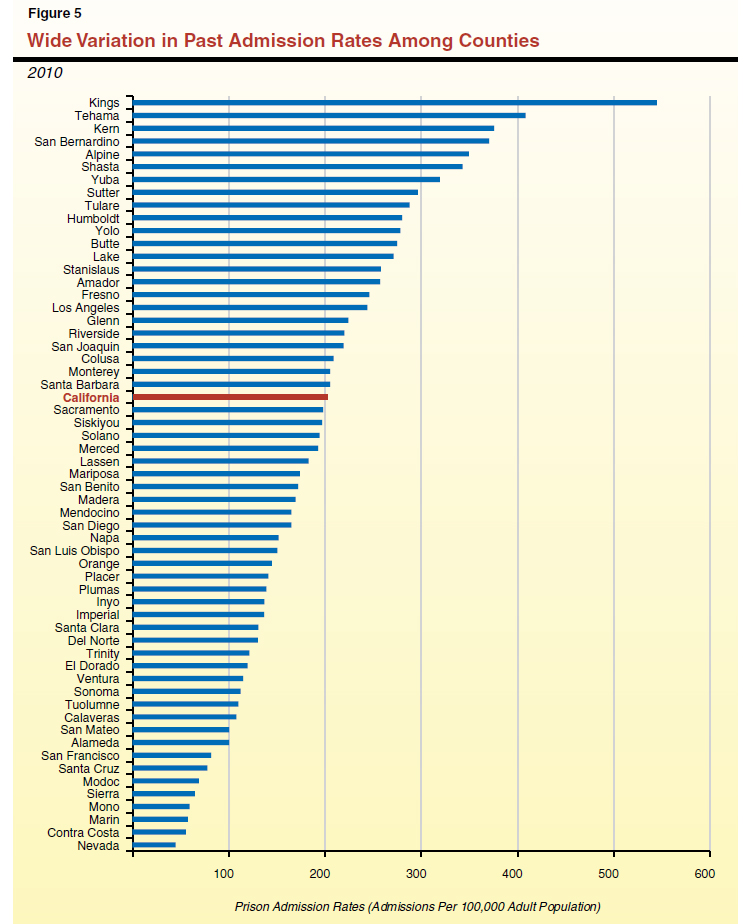

Currently, there is some debate among counties as to what factors should be used to determine county allocations. On the one hand, some believe that each county's share should largely reflect the number of criminal offenders estimated to be shifted to each county under realignment. On the other hand, other counties are concerned that such an allocation formula effectively rewards counties that have historically sent a disproportionate number of offenders to prison, whereas other counties may have more frequently utilized prevention programs or alternatives to prison. As shown in Figure 5, counties have varied widely in the rate at which they sent offenders to state prison. The current–year realignment allocation is more heavily weighted (60 percent) towards the number of offenders historically sent to state prison. There is, however, some weight (30 percent) in the allocation formula given to the size of each county's adult population. The remainder (10 percent) is based on each county's share of grant funding under the California Community Corrections Performance Incentives Act of 2009 (Chapter 608, Statutes of 2009 [SB 678, Leno]).

Proposed General Fund Augmentation Unjustified

The Governor proposes $8.9 million in General Fund monies in 2012–13 to support counties in their CCP process and for realignment training. This is in addition to the $7.9 million provided in 2011–12. The CCP process has been a positive one because it encourages various local stakeholders to collaborate and coordinate in planning for the new responsibilities under realignment. As such, the current–year appropriations for this purpose had merit because this financial support assisted counties in initiating this process before the first offenders—and realignment funding—became available to counties. We find, however, that the need for the state to fund this local planning process no longer exists in the budget year. In particular, the current realignment plan provides counties an increase of $490 million in 2012–13 specifically for the realignment of adult offenders. This increased funding includes a complement of funding specifically for administrative purposes, which would include local research and planning efforts. Moreover, counties are estimated to receive an additional $180 million in realignment funding in 2012–13 because of projected growth in sales tax and VLF revenues. The availability of this additional funding further reduces the necessity for the state to provide General Fund support for these local activities, particularly given the state's fiscal condition.

Role of BSCC Still Largely Undefined

The Legislature has defined BSCC's mission broadly, requiring that it collect and disseminate data and information, provide technical assistance to counties, and offer leadership in the area of criminal justice policy. However, the Legislature has not specifically laid out in statute BSCC's responsibilities in fulfilling this mission, leaving open a number of questions that need to be addressed. For example, how should BSCC be structured, what types of data should it collect, what form should its technical assistance take, and how can it help ensure local accountability and success?

Given its mission, BSCC will be expected to play an expanded role in local corrections, especially as counties adjust to their new responsibilities under 2011 realignment. While BSCC's mission has grown beyond the functions inherited from CSA and CalEMA, the Governor's budget does not propose additional staff or funding. In addition, the draft BSCC organizational chart provided by the administration does not appear to contemplate the new mission described in the realignment legislation. The organizational chart includes no new offices or divisions focused on the expanded technical assistance or data collection responsibilities envisioned by the Legislature in establishing the BSCC. According to the administration, additional resources may be requested—and changes to the organizational chart will be made—in the future after an executive director for BSCC has been appointed and has had the opportunity to develop a more comprehensive plan.

The lack of definition of BSCC's specific responsibilities, and the fact that BSCC's additional mission is not accommodated in the administration's plan (at least for the budget year), is problematic for two main reasons. First, as local governments have already begun absorbing caseload and receiving funding from 2011 public safety realignment, counties could benefit from technical assistance and expertise as they adapt to their new responsibilities, especially during this early stage. Second, there is currently no accountability system in place to ensure that local programs are operating effectively and efficiently. The BSCC should play a key role in this area, particularly in collecting and analyzing relevant data to allow policymakers and the public to evaluate a program's success. Without statewide leadership and coordination, the data collected locally will likely be inconsistent among counties, making it difficult to compare counties' performance and learn from local successes.

SB 678 Formula Still Needs Modification to Account for Realignment

In accordance with SB 678, counties currently receive funding based on their success in reducing the percentage of probationers sent to state prison compared to a county–specific baseline percentage of probationers they sent to prison between 2006 and 2008. Our analysis indicates that the realignment of adult offenders from the state to counties will affect some of the same offenders captured by the SB 678 formula. Without statutory changes, therefore, the SB 678 formula could effectively provide counties funding a second time for offenders already funded through realignment. Chapter 12, Statutes of 2011 (ABX1 17, Blumenfield), directs the Department of Finance in consultation with the Administrative Office of the Courts, the Chief Probation Officers of California, and CDCR to revise the formula to account for this. The administration has not yet proposed a revised formula, though we are advised that the required participants are working on a proposal to implement the necessary changes.

Based on the issues discussed above, we offer several recommendations designed to improve the likelihood that realignment will be implemented successfully for the long term. Specifically, we recommend (1) providing counties with flexibility on how to spend the unallocated realignment revenue growth, (2) adopting an allocation formula that provides money to counties in a way that is responsive to future changes in county demographics and other factors related to the number of offenders they are likely to manage, (3) rejecting the administration's request to fund local training and planning, and (4) more clearly defining the responsibilities of BSCC to focus on technical assistance and local accountability.

Create Reserve Fund for Revenue Growth to Promote Financial Flexibility

We recommend revising the Governor's proposed account structure to add a reserve fund into which all revenue growth above that which is already designated for specified programs would be deposited. In 2012–13, the administration estimates that this would be about $180 million. Under our proposal, this funding would be allocated among the 58 counties on a per capita basis, and each county would have discretion on how to spend their share of the reserve fund on realignment programs. This approach has two distinct benefits. First, it maximizes local flexibility, allowing each county to spend its share of funding on whichever realignment programs best meet their local needs, caseloads, and priorities. Some counties may want to prioritize more of its funding for public safety programs, while other counties may want to invest more of this discretionary funding into health and human services programs. Our approach would allow this variation across counties without interference from the state. Counties would still be required to fully fund federally mandated programs.

Second, financial flexibility also provides counties with a greater incentive to manage program costs more efficiently. Under our approach, each county would have the inherent incentive to stretch funding as far as it can to do as much as it can towards meeting its local priorities. In contrast, under the Governor's proposal, counties would have to spend the dollars provided for each program on that program, regardless of whether each program requires or would benefit from additional funding. This means, for example, that a program would get additional funding even if it had a declining caseload or if there were ways to reduce programs costs.

We recognize the Legislature may be concerned that providing counties with complete flexibility to allocate this growth in funding could mean that some programs would be allocated little of that additional funding over time if not a local priority. To the extent that the Legislature is concerned about this possibility, it could modify our proposal to, for example, require that at least some minimum share of the funding in the reserve be dedicated to the Support Services Account and the Law Enforcement Account with the remainder allocated at the discretion of the county.

Design Ongoing Allocation Formula to Be Responsive to Future Changes

Designing an ongoing allocation formula is challenging. Any factors used will favor some counties over others. For the long run, however, the key is to identify factors that (1) are reliable indicators of funding need, (2) adjust allocations over time as county demographics change, and (3) are not likely to result in poor incentives for counties. Based on these criteria, we recommend a long–term allocation formula where each county's share is based on two factors: its population of adults ages 18 through 35 years old and its number of adult felony dispositions (excluding dispositions to state prison). We believe these two factors appropriately reflect each county's potential correctional workload following realignment. Utilizing the population factor allows the formula to reflect the age group within a county statistically most likely to be at–risk of getting involved in the criminal justice system and provides greater allocations to more populous counties. Incorporating adult felony disposition data into the formula captures variation in levels of criminal activity across counties.

The combination of these two factors have the advantage of being responsive to changes in local populations over time, as well as giving some weight to local variations in felony criminal activity. Another advantage of this approach—as compared to basing allocations on the number of offenders historically sent to state prison—is that it provides some fiscal incentive for counties that have historically sent a higher proportion of offenders to prison to be more innovative and bring down their costs. To the extent that the Legislature is concerned that our proposed approach would leave counties currently receiving a disproportionately high number of offenders from state prison because of prior sentencing practices, our proposed funding formula could be phased in over a couple of years and, in the interim, could include a factor related to the number of offenders historically sent by each county to prison.

Importantly, the two factors we proposed to use for the long–term allocation formula are tracked on an annual basis, allowing allocation changes as county demographics and other factors change over time. This is important because some counties are projected to grow much more rapidly than others over the coming decades. Between 2010 and 2030, the state's total population of adults ages 18 through 35 is projected to grow by 18 percent. Some counties, however, are projected to grow much faster than the average. For example, among some of the state's largest counties, San Joaquin's population of 18 through 35 year olds is projected to grow by 70 percent over this period, Kern by 42 percent, Riverside by 40 percent, and Santa Clara by 36 percent. A formula that did not utilize population data might leave these and similarly growing counties at a disadvantage in future years.

Reject Governor's Proposal for Additional Year of Funding for CCPs

We recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor's proposal for $8.9 million to support counties in their CCP process and for realignment training. As we described above, the administration has not provided justification for this second year of funding. Moreover, with the hundreds of millions of dollars of additional revenues counties will receive under the realignment plan, we think counties can bear the administrative costs associated with developing CCPs and implementing training activities. Rather than the state providing direct funding to counties, we think the state should focus on developing the BSCC into an organization that can be a useful resource and provide technical assistance to counties as they implement realignment, as described below.

Utilize BSCC to Support Public Safety Through Technical Assistance and Local Accountability

The state has an interest in the overall success or failure of realignment because the shift of offenders from state to county responsibility could have a significant impact on public safety in California. In passing realignment legislation, the Legislature hoped that realignment could improve public safety outcomes by providing fiscal incentives for counties to identify more effective ways to manage lower–level criminal offenders, reduce recidivism, and lower overall criminal justice costs. On the other hand, if counties are unsuccessful at implementing realignment, public safety in California could be negatively affected and state and local corrections costs could increase. The Legislature envisioned BSCC being the primary state–level agency working with counties to ensure the success of realignment. Therefore, we recommend that the Legislature more clearly define BSCC's responsibilities, by adopting budget trailer bill legislation directing the department to (1) provide technical assistance to counties and (2) assist in the development of a local accountability system as described below.

Technical Assistance. Current law directs BSCC to provide technical assistance to county correctional agencies, though the provisions of this law do not identify the board's specific responsibilities in fulfilling this function. We have heard from county stakeholders, however, that counties would benefit from a single entity that had expertise in best practices nationally, as well as information on what other counties are doing that is effective. For example, the BSCC could be a repository for counties to access current research and data both within California and nationally. We have also heard that counties, particularly those that have less experience using correctional best practices, would benefit from having an agency that can provide assistance in implementing and evaluating those practices. It may be that BSCC could provide that function. Alternatively, BSCC may not need to provide that type of assistance directly, but it could provide counties with information about which researchers, practitioners, and universities offer those services in California. Technical assistance performed by BSCC, in whatever shape it takes, can assist counties in identifying and implementing best practices, as well as evaluating how effectively and efficiently local programs are operating. In so doing, counties can make better decisions on how to implement realignment to achieve improved outcomes and reduce costs.

Local Accountability. Current law also requires BSCC to collect and disseminate California corrections data. A state role in data collection can help promote public safety and the success of realignment if that role is focused on providing local accountability. To the extent that useful information is available to local stakeholders—corrections managers, county elected officials, local media, and the public—local governments can be held accountable for their outcomes and expenditures. For example, county boards of supervisors can hold their jail and probation managers accountable for how effectively and efficiently their programs are managed, and the general public can raise concerns with their elected officials if they see that their county's outcomes are significantly worse than other counties. Because decisions about how to manage realignment populations and resources are inherently local decisions, the focus of accountability should be local. For this reason, the role of BSCC should not be to collect data for the sake of informing the state of what is happening locally. Instead, the role of BSCC should be to facilitate local accountability, such as by assisting counties in providing transparency and uniformity in how they report outcomes.

A good example of a statewide system that promotes local accountability is in the area of child welfare. In this system, information on individual child welfare cases is entered into a case management information technology (IT) system by county workers. The University of California at Berkeley then consolidates this data and posts aggregated data on the Internet where it can be accessed by anyone. Individual level data is not available on the public website, but people using this site can create different reports showing various outcomes across counties and across years. This accountability system is comprehensive, ensures uniform reporting, and is readily accessible to the public. We have heard that this system has allowed state and local policymakers to make more informed program decisions, identify areas for improvement, and hold program managers publicly accountable. Unfortunately, developing a similar IT system for local corrections accountability is probably not practical in the near term, since creating such a statewide IT system takes years to complete and would be very expensive. For example, a case management system currently being implemented by CDCR for the state prison and parole system will cost about $400 million by the time it is completed.

Even in the absence of a comprehensive IT system to promote local accountability, like in the child welfare field, BSCC should play an active role in ensuring local accountability. Thus, we recommend that the board, after being established in July, take a leadership role in implementing a uniform process for counties to report local corrections outcomes. We understand that various stakeholders (including counties, the administration, researchers, and universities) have been holding different meetings to discuss data collection issues and other implementation issues. It is not clear, however, the degree to which these conversations are focused on promoting long–term local accountability, or the degree to which they will be successful in creating statewide uniformity on the measures to be implemented.

We recommend the Legislature direct the BSCC (or CDCR, until the BSCC is officially established) to create a working group to identify an accountability system that is as comprehensive, uniform, and accessible as is reasonable given limited state and local resources. This group should be made up of representatives of the state, counties, and the broader research community and should focus on (1) identifying the handful of key outcome measures that all counties should collect, (2) clearly defining these measures to ensure that all counties collect them uniformly, and (3) developing a process for counties to report the data and for BSCC to make the data available to the public.

In the near term, it would probably be most practical for the state to simply expand on current data collection systems. For example, CSA has a quarterly jail survey they conduct of counties. This could be expanded to include probation department caseloads, as well as to include a few key outcome measures, such as successful discharges from community supervision and recidivism rates. We think that building on an existing process may be the less burdensome and costly for counties. Once receiving the data from counties, the BSCC should be required to post the data on its public website in a format that allows the public to create sortable reports to compare caseloads and outcomes across counties and time. The Legislature may also want to direct BSCC to begin exploring the feasibility of developing a more comprehensive statewide case management system, including determining the overall costs, potential funding sources (including federal and private dollars), implementation challenges (such as in counties without robust IT infrastructures), and the potential fiscal and programmatic benefits to counties.

Finally, we recommend that the Legislature direct CSA to report at budget hearings on plans for how it will fulfill the new mission of BSCC. In particular, the administration should report on what steps it plans to take to provide technical assistance to counties and to assist in the development of local accountability systems. The administration should also report on how it can focus on these responsibilities, within existing resources or to what extent additional funding may be necessary. As noted above, the Governor's budget provides no new funding for the BSCC. We note that, if adopted, our recommendation to reject the Governor's proposal to provide counties with planning and training funding would save $8.9 million in General Fund resources, some of which could be directed to support BSCC's new mission.

The 2011 realignment of adult offenders has the potential to produce a more efficient and effective statewide criminal justice system. Long–term success, however, will depend on the choices made, in particular, by county policymakers and program managers. The state can promote success and give counties a better opportunity to implement realignment effectively by taking some actions today to support local financial flexibility, allocating funding in a way that encourages innovation, and supporting local accountability.