In April 2012, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) released a report (referred to as the "blueprint") on the administration's plan to reorganize various aspects of CDCR operations, facilities, and budgets in response to the effects of the 2011 realignment of adult offenders, as well as to meet various federal court requirements (such as reducing the inmate population to meet specified population cap targets). In this brief we (1) summarize and assess the major aspects of the blueprint and (2) present alternative approaches that are available to the Legislature. In our view, much of the administration's blueprint merits legislative consideration. However, the General Fund costs of the planned approach—in particular, an estimated $78 million in annual debt service—is a significant trade–off. We find that the state could meet its facility requirements (including those for medical and mental health treatment) and specified population cap targets at much lower ongoing General Fund costs than proposed by the administration, potentially saving the state as much as a billion dollars over the next seven years.

In 2009, a federal three–judge panel issued a ruling requiring the state to reduce the amount of inmate overcrowding in California prisons. Specifically, the ruling required the state to reduce within two years overcrowding to 137.5 percent of the design capacity in the 33 prisons operated by CDCR. (Design capacity generally refers to the number of beds CDCR would operate if it housed only one inmate per cell and did not use temporary beds, such as housing inmates in gyms. Inmates housed in contract facilities or fire camps are not counted toward the overcrowding limit.) In May 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the three–judge panel's ruling. Under the population cap imposed by the federal courts, the state would need to reduce the number of inmates housed in its 33 state prisons by about 34,000 inmates by June 2013.

In 2011, the state enacted legislation that "realigned"—or shifted responsibility for managing—certain felony offenders from state prisons and parole to county jails and probation supervision. Realignment is projected to reduce the state inmate population by approximately 40,000 inmates over the next five years. (Please see our report, The 2012–13 Budget: Refocusing CDCR After the 2011 Realignment [February 2012], for more detailed information regarding the three–judge panel ruling and the implementation of the 2011 realignment.)

In April 2012, the CDCR released The Future of California Corrections (generally referred to as the CDCR blueprint), which outlines the administration's plan to reorganize various aspects of CDCR operations, facilities, and budgets in response to effects of realignment and to meet federal court requirements. The plan includes a multitude of changes. These include several changes that would increase the state's prison system capacity, more than offset by other proposals reducing the state's capacity. As shown in Figure 1, on net the blueprint would reduce the state's prison capacity by almost 2,000 beds. The blueprint also includes various operational and other changes which have no direct impact on capacity. Some components of the plan requiring legislative approval are included in the Governor's May Revision proposal for 2012–13. In total, the administration's plan would meet the Governor's budget proposal to reduce state spending on adult prison and parole operations by $1 billion in 2012–13 as a result of 2011 realignment. The plan estimates that these savings will grow to $1.5 billion by 2015–16. Figure 2 shows the administration's estimated savings and position reductions to CDCR under the blueprint. We describe each of the major components of the blueprint below.

Figure 1

Major Components of Blueprint Affecting State Prison Capacity

|

Blueprint Component

|

Number of Beds

|

|

Increase population cap to 145 percent

|

5,924

|

|

Construct three infill projects

|

3,445

|

|

Renovate DeWitt Nelson Juvenile Facility

|

1,643

|

|

Expand in–state contracts

|

1,225

|

|

Reduce population

|

500

|

|

End out–of–state contracts

|

–9,588

|

|

Close California Rehabilitation Center

|

–3,612

|

|

Reduce fire camp capacity

|

–1,500

|

|

Net Changes

|

–1,963

|

Figure 2

Blueprint Achieves Significant Savings

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

2015–16

|

|

Budget reductiona

|

$1,000

|

$1,317

|

$1,458

|

$1,544

|

|

Position reductiona

|

5,549

|

6,032

|

6,431

|

6,630

|

Changes to Increase Total CDCR Capacity

The CDCR blueprint includes several changes that would have the effect of increasing the state's total capacity to house offenders. Specifically, the blueprint includes plans to:

- Request Increased Prison Capacity of 145 Percent. The administration's plan assumes that the court–imposed population cap would be increased to 145 percent of design capacity. (At the time this analysis was prepared, such a request has not been submitted to the federal court.) This would allow the state to house about 5,900 more inmates in existing state prisons than would be the case under the 137.5 percent cap.

- Construct Three Infill Projects. The administration requests as part of the May Revision $810 million in new lease–revenue bond authority to construct additional low–security prison housing at three existing prisons, though the specific locations have not yet been chosen. The proposed projects would have capacity for 3,445 inmates under the proposed 145 percent population cap (design capacity of 2,376 inmates) and would include sufficient space to permit the operation of inmate programs such as mental health treatment and academic programs.

- Renovate DeWitt Juvenile Facility for Adult Inmates. The administration requests as part of the May Revision $167 million in lease revenue authority from Chapter 7, Statutes of 2007 (AB 900 Solorio), for the renovation of the DeWitt Nelson Youth Correctional Facility to house adult offenders. The facility would serve as an annex to the California Health Care Facility (CHCF) currently under construction in Stockton. Under the proposed 145 percent population cap, the DeWitt facility would have capacity for 1,643 lower–security inmates (design capacity of 1,133 beds). Most of these beds would be used to house inmates who have regular medical and mental health treatment needs, thereby helping the state address shortfalls identified by the federal courts overseeing the provision of prison medical and mental health care.

- Increase Use of In–State Contract Beds. The administration requests authority to expand the use of in–state contract beds for an additional 1,225 low–security inmates. The state currently houses about 700 inmates in various in–state contracted facilities.

- Reduce Population. The plan includes two proposed statutory changes that would further reduce the population by approximately 500 inmates, thereby freeing up an equivalent number of prison beds. First, the administration proposes to cease the Civil Addict Program beginning in 2013. (This program allows courts to civilly commit offenders to prison to receive substance abuse treatment.) The administration also proposes to expand the eligibility criteria for the Alternative Custody for Women program, which allows certain female offenders to serve their sentence in the community rather than in state prison.

Changes That Reduce Total CDCR Capacity

The administration's blueprint includes several components that would have the effect of reducing the state's total capacity to house felon offenders. Specifically, the administration proposes the following:

- End Use of Out–of–State Contract Beds. Over the next four years, the administration plans to eliminate the practice of housing inmates in out–of–state contracted facilities. There are currently about 9,500 inmates housed in out–of–state facilities.

- Close the California Rehabilitation Center (CRC). The blueprint assumes that one prison, CRC (Norco), will be closed in 2015–16. Under the proposed 145 percent population cap, CRC has the capacity for about 3,600 low security inmates.

- Reduce Use of Fire Camps. The CDCR blueprint assumes that realignment will reduce the availability of offenders eligible to work in the state's fire camps. The blueprint assumes that the fire camp population will decrease from about 4,000 to 2,500 inmates by June 2013.

Operational and Other Provisions

The blueprint also contains several components that do not directly affect the number of inmates in the state prison system nor the amount of capacity to house inmates.

- Modify Inmate Classification System. The administration plans to implement new security classification regulations that will allow about 17,000 inmates to be housed in lower–security facilities than under current classification rules. These changes are in response to a study recently completed by several academic researchers at the request of the administration.

- Establish Standardized Staffing for Prisons. The administration plans to begin using standardized staffing packages for each prison based on factors such as the prison's population, physical design, and missions. For the most part, prison staffing levels would remain fixed unless there were significant enough changes in the inmate population to justify opening or closing new housing units. Historically, prison staffing levels have been regularly adjusted to reflect changes in the inmate population regardless of the magnitude of those changes.

- Make Prison Health Care Facility Improvements. The blueprint includes the use of existing lease revenue authority from AB 900 to design and implement health care improvements at all existing prisons (except CRC). Although, specific project cost estimates have not been provided, the administration estimates that in total these projects will cost about $700 million to design and construct.

- Modify Delivery of Rehabilitation Programming. The department indicates that it no longer plans to build the reentry prisons that were called for in AB 900. (As discussed below, the administration is proposing to reduce the size of AB 900.) Instead, it will now designate certain existing prisons as reentry hubs to house inmates nearing release and provide them with enhanced programming services. The plan also calls for the expansion of certain types of programs that the department has not historically provided on a large scale (such as anger management and cognitive behavioral treatment). In addition, the plan proposes to expand the availability of rehabilitation programming to parolees supervised by CDCR.

- Change Missions of Many Existing Prisons. The blueprint modifies the missions of many prisons. For example, the administration plans to convert some reception centers to general population facilities. As discussed above, certain prisons will also be designated as reentry hubs.

- Reduce AB 900 Appropriation. The AB 900 authorized a total of $6.5 billion for prison construction projects, of which about $1.5 billion has been used. The blueprint calls for the elimination of $4.1 billion of the remaining $5 billion of the AB 900 bond funds for state prison construction projects.

- Expand CDCR Oversight. The administration proposes various additional reporting requirements, including regular reporting to the administration and Legislature, by CDCR of its progress implementing the various components of the blueprint.

In our view, much of the administration's blueprint merits legislative consideration. However, the plan does raise several concerns. In particular, the administration has not justified the need for several costly prison construction projects that would add $76 million in annual debt–service costs to the General Fund. The proposed projects also appear to be significantly more expensive than other recently proposed prison construction projects. In addition, the blueprint depends on the uncertain court approval of its request to raise the population cap to 145 percent of design capacity. Finally, the blueprint lacks details in several important areas. We discuss each of these issues in more detail below.

Blueprint Merits Consideration. In our view, the Legislature should carefully review the administration's blueprint, but we find that the plan has much that merits consideration. For example, the plan achieves the level of savings targeted for CDCR's adult operations in the budget year, and those savings grow in out years. In addition, we find that many of the individual components of the plan are generally a step in the right direction towards reducing prison overcrowding and refocusing the priorities of CDCR. For example, reducing reliance on out–of–state contracted beds has the potential to help improve rehabilitation by bringing inmates closer to their families and local communities. Standardized staffing could better ensure that prisons have consistent and appropriate staffing levels across the state. Closing CRC would allow the department to close a facility that was not originally designed as a prison and is currently under significant disrepair. The classification changes will allow CDCR to house offenders at a lower cost and improve access to rehabilitation programming. Finally, the proposed changes affecting CDCR capacity generally would provide the right mix of beds to meet the types of inmates projected to be in CDCR in future years, including by security level and for inmates with specialized health and mental health placement needs.

New Construction Proposals Will Increase Annual General Fund Costs, but Blueprint Will Decrease Total Capacity. The administration's blueprint would result in an annual increase in General Fund costs of about $76 million to pay the debt service on the roughly $1 billion in lease–revenue bonds needed to finance its plan to construct three infill projects and renovate the DeWitt juvenile facility. Despite these increased costs, the plan would actually result in a net decrease in overall bed capacity of roughly 2,000 beds.

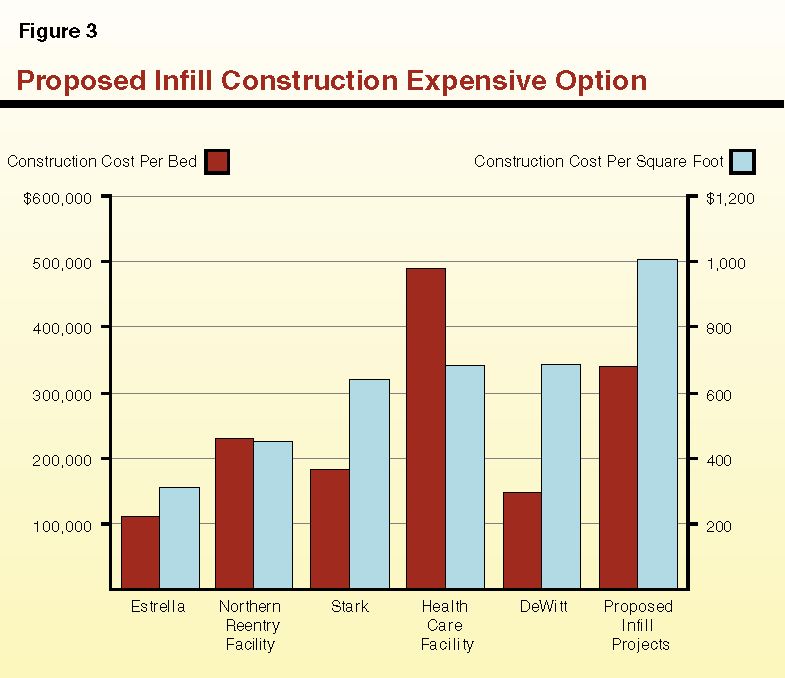

Proposed Infill Construction Costs Are High Compared to Other Projects. The construction costs of the proposed infill bed facilities are significantly higher than most other recently proposed or initiated major prison projects. (We briefly describe each of these projects in a nearby box) As shown in Figure 3, the proposed infill projects are more expensive per square foot than any other project. The infill projects are also more expensive on a per–bed basis than any other project except CHCF, which includes additional infrastructure for delivering complex inpatient mental health and medical treatment. The higher construction costs are largely attributable to the fact that most of the other recently proposed or initiated projects involve the renovation of existing facilities (with the exception of CHCF), which typically lowers overall construction costs. We note that there are some important advantages to constructing new facilities—such as ability to incorporate modern design standards and longer life of the facility—and that the proposed infill projects would have the operational benefit of including sufficient programming space to be used flexibly for different types of inmate programs. However, it is uncertain whether these advantages are worth the substantially higher construction costs.

Recently Proposed Prison Construction Projects

In recent years, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) has proposed or initiated several prison construction projects. We summarize some of the major projects below. (We note that capacity figures reflect the design capacity of each facility.)

- Northern California Reentry Facility (NCRF). In 2010, CDCR proposed the conversion of the former Northern California Women's Facility into a male reentry prison known as NCRF. The facility was proposed to have 500 general population beds and provide inmates with comprehensive rehabilitation programming prior to their release from prison. Estimated renovation costs were $115 million. The administration no longer intends to proceed with the project.

- Estrella Facility. In 2009, the department proposed the conversion of the former juvenile justice facility in Paso Robles into an adult male prison known as the Estrella facility. The facility was proposed to include 1,000 beds, including 200 beds for inmates requiring outpatient mental health treatment, 200 beds for inmates requiring outpatient medical treatment, and 600 general population beds. The administration estimated this project would cost $111 million to renovate. The administration's proposed 2012–13 budget includes the cancellation of the Estrella project.

- Stark Facility. In 2010, the department proposed the conversion of the former juvenile justice facility in Chino into an adult male prison known as the Stark facility. The facility was proposed to include about 2,800 beds, including 1,800 reception center beds, 600 beds for inmates requiring outpatient mental health treatment, 400 general population beds, and a 60 bed correctional treatment center to provide inpatient mental health and medical treatment. The administration estimated that this project would cost $519 million, but indicates that it is no longer pursuing this project.

- California Health Care Facility (CHCF). The construction of the CHCF in Stockton is currently underway and expected to be completed by July 2013. The facility will provide about 1,700 total beds including about 1,000 beds for inpatient medical treatment, about 600 beds for inpatient mental health treatment, and 100 general population beds. The CHCF is estimated to cost about $840 million to construct.

Additional Construction Not Fully Justified. The proposed renovation of the DeWitt facility would provide additional housing and treatment space for inmates in need of mental health and medical treatment. Specifically, the facility would provide about 400 beds for mentally ill inmates requiring specially designed housing units that include readily accessible outpatient treatment space (known as Enhanced Outpatient [EOP] inmates) and about 500 beds for inmates in need of chronic outpatient medical treatment (known as Specialized General Population [SGP] inmates). According to the administration, this capacity is needed in order to provide a constitutional level of inmate medical and mental health treatment. However, as we discuss in our February 2012 report, there does not appear to be a need for any additional EOP or SGP beds. This is because the reduced overcrowding that results from realignment, as well as the construction of various health care infrastructure improvements also being proposed, will make it easier for the department to deliver adequate medical care to SGP inmates within existing prisons. In addition, realignment is projected to result in a large decrease in EOP inmates. According to the department's most recent projections, there will be a surplus of over 100 EOP beds in 2016–17 without the construction of the DeWitt facility.

According to the administration, the proposed infill projects would be built with a flexible design that would allow them to house general population inmates or inmates needing mental or medical treatment on an outpatient basis (such as EOP and SGP inmates), depending on the department's future needs. However, the department has not been able to identify the specific population that would be housed in these facilities nor has it demonstrated that the projects are needed in order to deliver additional health care capacity. We also note that neither the plaintiffs in the Plata class action case (related to inmate medical care) nor the plaintiffs in the Coleman class action case (related to inmate mental health care) have indicated that the infill facilities are needed to comply with the settlement agreements in those cases.

Uncertain Whether Court Will Approve of Increase of Population Cap. The administration's plan is dependent on the federal court approving a requested increase in the population cap to 145 percent of design capacity. However, it is uncertain whether the court will approve the increased population cap, and the administration has not presented a detailed back–up plan in the event that the court denies the request to increase the cap. The blueprint contains only a short reference that rejection of the population cap increase would result in a need to identify alternatives, such as increased reliance on out–of–state beds. In addition, the administration is asking the Legislature to approve components of its plan without any indication of when it will seek the court's approval of the increased population cap. As we describe in more detail later, the Legislature has a variety of alternatives for satisfying the court order to meet the population cap, but these alternatives have varying trade–offs. Thus, it would be difficult for the Legislature to determine the most prudent course of action without first knowing the court's decision.

Some Details Still Needed. The blueprint lacks detail in several important areas. For example, while the Governor's budget assumes $100 million in savings from realignment in the medical program in 2012–13, rising to $153 million annually upon the full implementation of realignment in 2015–16, the plan includes no indication of how these savings will be achieved. In addition, the blueprint for delivering rehabilitation programming lacks details on how the department will address issues related to its long–standing inability to assign inmates and parolees to programs based on risk and needs assessments, as we discuss in our February 2012 report. Finally, the administration has not yet submitted details (such as specific building plans and individual project costs) on the projects it intends to complete using the approximately $700 million designated in AB 900 for health care infrastructure improvements in existing prisons. Despite the lack of details, the administration is also proposing budget trailer bill language that would reduce legislative oversight over the health care improvements by amending existing state law to eliminate a requirement that the department submit individual projects for legislative review before beginning construction. We recommend rejection of this language, instead reserving the authority of the Legislature to review the scope and estimated costs for projects before approving funding authority.

Many pieces of the CDCR blueprint are mutually dependent on one another. As such, the Legislature will need to consider how each component fits as part of a package. For example, much of the department's plan would have to be reconsidered if the proposed security reclassification of inmates was not implemented. Without reclassification, the department's plan would overbuild lower–security beds while having too few higher–security beds. Similarly, the housing plans will need to be reconsidered if the federal court does not agree to adjust the population limit to 145 percent of design capacity. The adjustment in the population limit is a particularly critical factor as an increase in the allowable capacity enables the state to house nearly 6,000 additional inmates.

While each component of the blueprint should be viewed in the context of the larger package, that does not imply that the Legislature could not consider alternative packages. In fact, the Legislature could take a number of different approaches depending on its policy priorities for CDCR. The blueprint, for example, reflects the administration's priorities that include ending out–of–state contracts, closing CRC, and constructing new prison facilities. Alternatively, the Legislature could consider prioritizing each of these components differently and, consequently, achieve different levels of General Fund savings for operations and debt service.

Below, we recommend an alternative approach to the blueprint for housing state inmates. In addition, we lay out two other alternative packages, based on a different set of priorities, that could be considered (referred to as "Alternative 1" and "Alternative 2"). Each of the alternatives we present modify various aspects of the blueprint while achieving its primary goals of meeting specified capacity targets. However, each of the alternatives does so at lower ongoing General Fund cost than under the blueprint. Because the appropriate package will depend heavily on whether the federal court approves an adjustment in the population limit, we lay out our recommendations and alternatives both in the event the court approves the adjustment and if no adjustment is granted. We strongly encourage the Legislature to weigh the trade–offs of each alternative.

We note that each of the alternatives under both scenarios—the court approving the requested population cap adjustment and the court not approving the requested adjustment—assume an increase in the number of offenders housed in the state's fire camps. The varying alternatives assume full utilization of the camps consistent with recent recommendations we have made that CDCR review its fire camp eligibility criteria and increase efforts to get inmates into camps—for example, by adopting increased incentives for inmate participation. (For more on CDCR's fire camp program and these recommendations, please see The 2012–13 Budget: Refocusing CDCR After the 2011 Realignment.) We also note that the proposed change in the classification system discussed above will likely increase the number of offenders qualifying for fire camp placements, which could also increase the fire camp population.

Alternative Packages if the Court Approves the 145 Percent Population Limit

If the federal court approves the proposed increase in the population limit to 145 percent of design capacity, the Legislature has several alternative packages of changes available that would allow the state to reach this revised capacity level. Depending on the Legislature's policy priorities, it could choose from packages that vary in the degree to which they rely on contract beds, the closure of CRC, and new construction. All of the alternative scenarios we provide below result in significant annual savings relative to the administration's blueprint, in large part because of reduced reliance on construction. Each of the alternatives, which are also depicted in Figure 4, is described below.

Figure 4

Comparing Blueprint and Alternatives if Court Approves Population Cap Increase

June 30, 2016 (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

Administration Blueprint

|

LAO Recommendation

|

Alternative 1

|

Alternative 2

|

|

Population Cap

|

145%

|

145%

|

145%

|

145%

|

|

Inmate Populationa

|

122,863

|

122,863

|

122,863

|

122,863

|

|

Capacityb

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDCR prisonsc

|

114,531

|

114,531

|

114,531

|

114,531

|

|

CRC

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

3,612

|

|

DeWitt

|

1,643

|

—

|

1,643

|

—

|

|

Infill projects

|

3,445

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Estrella

|

—

|

—

|

1,450

|

—

|

|

Fire camps

|

2,500

|

4,000

|

4,000

|

4,000

|

|

Out–of–state contracts

|

—

|

2,908

|

—

|

—

|

|

In–state contracts

|

1,924

|

1,924

|

1,739

|

1,220

|

|

Total Capacity

|

124,043

|

123,363

|

123,363

|

123,363

|

|

Surplus

|

1,180

|

500

|

500

|

500

|

|

Annual CDCR Savings Relative to Governor's Plan

|

|

Operations

|

—

|

$79

|

$53

|

–$23

|

|

Debt service

|

—

|

76

|

55

|

76

|

|

Total Savings

|

—

|

$155

|

$107

|

$54

|

LAO Recommendation. We recommend the state (1) close CRC, (2) reject the proposed DeWitt and infill construction projects, and (3) significantly reduce—though not eliminate—the state's reliance on out–of–state contract beds. This would save the state an additional $155 million annually relative to the plan proposed in the blueprint. These savings are derived primarily from the elimination of the additional debt–service payments and operations costs associated with the construction proposed in the administration's plan. As indicated in Figure 4, our recommended approach results in the greatest costs savings of the alternatives identified, permits the closure of CRC, avoids costly construction, and substantially reduces the number of out–of–state contracts.

Alternative 1. Alternatively, the state could (1) close CRC, (2) renovate the DeWitt facility, (3) renovate the Estrella facility in lieu of the three infill projects, and (4) eliminate the use of out–of–state contracts and reduce the number of in–state contracts relative to the blueprint. This would save the state an additional $107 million annually relative to the plan proposed in the blueprint. These savings are derived primarily from lower debt–service payments incurred by the state given that the Estrella project is significantly less expensive than the three proposed infill projects, as well as lower operational savings due to the use of fewer instate contracts. Although this approach would result in the closure of CRC and less reliance on contract beds than the blueprint, it would include construction that, in our view, the administration has not fully justified.

Alternative 2. Under this approach, the state would (1) continue to operate CRC for the near future, (2) reject the proposed DeWitt and infill construction projects, and (3) eliminate the use of out–of–state contracts and reduce the number of in–state contracts. This would save the state an additional $54 million annually relative to the plan proposed in the blueprint. These savings are derived primarily from the elimination of the additional debt–service payments associated with the DeWitt and infill projects. While this approach avoids costly construction, it results in an increase in operational costs relative to the administration's modified plan because of the continued operation of CRC.

Alternative Packages if the Court Does Not Approve the 145 Percent Population Limit

If the federal court does not approve an increase in the population limit to 145 percent of design capacity, the Legislature will be unable to eliminate the out–of–state contracts without more construction than contained in the administration's plan or the adoption of policy changes that would further reduce the state's inmate population. However, the state could pursue alternative packages that would be less expensive. Depending on the Legislature's policy priorities, it could choose among packages that to differing degrees reduce the number of contract beds currently used by the state, close CRC, and/or rely on less new construction.

We note that the blueprint indicates that if the court does not approve a change in the population limit it will rely on additional contract beds to meet the 137.5 percent of design capacity limit. While the administration did not specify whether these contracts would be for in–state or out–of–state beds, we assume the state would use out–of–state beds because of a lack of higher security contract beds available in California. Accordingly, the savings of each alternative displayed in Figure 5 is scored relative to a modified version of the blueprint in which the state enters into contracts for additional out–of–state beds. Each of the alternatives is described below.

Figure 5

Comparing Modified Blueprint and Alternatives if Court Does Not Approve Population Cap Increase

June 30, 2016 (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

Modified Blueprint

|

LAO Recommendation

|

Alternative 1

|

Alternative 2

|

|

Population Cap

|

137.5%

|

137.5%

|

137.5%

|

137.5%

|

|

Inmate Populationa

|

122,863

|

122,863

|

122,863

|

122,863

|

|

Capacityb

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDCR prisonsc

|

108,607

|

108,607

|

108,607

|

108,607

|

|

CRC

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

3,425

|

|

DeWitt

|

1,558

|

—

|

1,558

|

—

|

|

Infill projects

|

3,267

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Fire camps

|

2,500

|

4,000

|

4,000

|

4,000

|

|

Out–of–state contractsd

|

6,187

|

8,832

|

7,274

|

5,407

|

|

In–state contracts

|

1,924

|

1,924

|

1,924

|

1,924

|

|

Total Capacity

|

124,043

|

123,363

|

123,363

|

123,363

|

|

Surplus

|

1,180

|

500

|

500

|

500

|

|

Annual CDCR Savings Relative to Modified Blueprint

|

|

Operations

|

—

|

$83

|

$75

|

–$18

|

|

Debt service

|

—

|

76

|

63

|

$76

|

|

Total Savings

|

—

|

$159

|

$138

|

$58

|

LAO Recommendation. If the federal court does not approve the increase in the population cap, we would recommend that the state adopt a package that (1) closes CRC, (2) rejects the proposed DeWitt and three infill projects, and (3) modestly reduces the state's reliance on out–of–state contract beds. This would save the state an additional $159 million annually relative to the modified administration plan. These savings are primarily derived from the elimination of the additional debt–service payments and operations costs associated with the construction proposed in the administration's plans. As indicated in Figure 5, our recommended approach would result in the greatest cost savings of the alternatives we identify and permit the closure of CRC while avoiding construction and still reducing the number of out–of–state contracts.

Alternative 1. Instead, the state could (1) close CRC, (2) approve the DeWitt project, (3) reject the three infill projects, and (4) make a modest reduction in the use of out–of–state contracts. This would save the state an additional $138 million annually relative to the administration's modified plan. These savings result primarily from the elimination of the debt service and operating costs associated with the three proposed infill projects. While this approach would result in the closure of CRC and less reliance on contract beds, it would include construction that, in our view, the administration has not fully justified.

Alternative 2. Under this approach, the state would (1) keep CRC in operation, (2) reject the DeWitt and three infill projects, and (3) make a fairly significant reduction in the use of out–of–state contracts. This would save the state an additional $58 million annually relative to the modified administration plan. These savings are derived from the elimination of the additional debt–service payments associated with the DeWitt and infill projects. While this approach avoids costly construction, it results in an increase in operational costs relative to the administration's modified plan because of the continued operation of CRC.

While the administration's blueprint merits careful consideration by the Legislature, we find that there are alternative packages that are available to the Legislature. Each alternative, including the CDCR blueprint, comes with significant trade–offs to consider. However, we find that the state could meet specified population cap targets at much lower ongoing General Fund costs in the future than proposed by the administration, potentially saving the state over a billion dollars over the next seven years.