Febuary 8, 2012

The Governor's budget provides $9.4 billion in General Fund support for higher education in 2012–13. This amount is $348 million, or 3.6 percent, less than the revised current–year level. When other core funding (primarily student tuition revenue, federal funds, and local property taxes) is included, higher education would receive about $17 billion, which reflects an increase of 2.4 percent.

We also compare the Governor's proposed funding level with that provided in 2007–08 (which was the last year that higher education received normal workload and inflation adjustments). While proposed General Fund support for higher education declines by 21 percent over the five–year period, total core funding for higher education would increase by 1.2 percent.

Governor's Proposals

The Governor's budget proposal for higher education reflects three broad themes:

New Approach to Segments' Budgets. The Governor's proposal reduces various restrictions on the three segments' budgets, including the elimination of enrollment targets and other requirements. At the same time, it promises funding increases in subsequent years, contingent on the segments' meeting as–yet–undefined performance standards. For the universities, the proposal also would change how bond debt service and retirement costs are funded.

Budget Solutions Concentrated in State Financial Aid Programs. Virtually all of the Governor's proposed General Fund savings in higher education—$1.1 billion—is concentrated in the state's financial aid programs. Almost two–thirds of this amount comes from replacing General Fund support with other fund sources, and thus would have no programmatic effect on students. The remaining one–third of his General Fund savings is achieved by tightening financial and academic requirements for receiving aid, reducing the size of some grants, and eliminating some smaller programs.

Segments' Budgets Linked to Fate of Tax Package. While the Governor seeks no General Fund savings from the segments in his main budget proposal, all three segments would be subject to midyear cuts if the Governor's proposed tax increases are rejected by voters in November 2012. Specifically, the University of California and California State University would each receive midyear General Fund reductions of $200 million, while general purpose funds for the California Community Colleges would be cut by almost $300 million.

LAO Findings and Recommendations

In addition to describing the Governor's proposals, this report includes various findings and recommendations for the Legislature. Key findings and recommendations include:

New Approach to Segments Would Undermine Legislature's Budget Role. While we can appreciate the Governor's attention to higher education accountability, we think many aspects of the Governor's plan would reduce the Legislature's ability to allocate higher education funding according to its priorities. The elimination of enrollment targets and the promise of automatic funding increases are of particular concern.

Some Financial Aid Proposals Could Unduly Harm Access and Increase State's Long–Term Costs. We agree with several aspects of the Governor's financial aid proposals, including the need to refine some eligibility criteria and to phase out some unproductive programs. However, we believe some of the strengthened academic requirements, as well as reductions to Cal Grant awards for needy students at private institutions, would unreasonably harm access. Meanwhile, proposed cuts to Cal Grants at private institutions would end up costing the state more money in the long term if it leads to a significant shift of those students to public institutions.

Community College Aid Program Needs Improvement. The Governor does not propose any changes to the community colleges' fee waiver program, whose costs have been escalating. Well over half of all community college students receive fee waivers, and this number is expected to keep climbing. Meanwhile, the program places few academic or other requirements on students, resulting in low student success rates. We recommend specific changes to this program.

Legislature Has Options in Approaching Trigger Cuts. Given that a significant portion of the Governor's revenue assumptions is subject to voter approval, it makes sense to include a contingency plan in the event voters reject his tax proposal. However, the Legislature has choices as to how the contingency plans are structured. For example, the Legislature could allocate the trigger cuts differently among the state's education and non–education programs. The Legislature could also take the opposite approach from the Governor: building a budget that does not rely on the Governor's tax package, with contingency augmentations if the tax package is approved.

California's publicly funded higher education system includes the University of California (UC), the California State University (CSU), the California Community Colleges (CCC), Hastings College of the Law, and the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC). For 2012–13, the Governor's proposed budget provides higher education with General Fund appropriations of $9.4 billion, which is $348 million, or 3.6 percent, less than the current–year amount (see Figure 1). However, this masks a number of significant changes to the higher education budget, including fund substitutions, programmatic reductions, and cost shifts. Most significantly, the budget includes about $300 million of cuts to the Cal Grant program. Moreover, if the Governor's proposed tax increases are rejected by the voters in November, higher education would sustain almost $700 million in "trigger" reductions.

Figure 1

Governor's Budget Proposal for Higher Education

General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2011–12

Revised

|

2012–13

Proposed

|

Change

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California a

|

$2,273.6

|

$2,570.8

|

$297.2

|

13.1%

|

|

California State University a

|

2,002.7

|

2,200.4

|

197.7

|

9.9

|

|

California Community College

|

3,276.7

|

3,740.2

|

463.5

|

14.1

|

|

Hastings College of the Law (Hastings)a

|

6.9

|

8.8

|

1.8

|

26.2

|

|

California Postsecondary Education Commission

|

0.9

|

—

|

–0.9

|

–100.0

|

|

California Student Aid Commission

|

1,481.7

|

567.9

|

–913.7

|

–61.7

|

|

General obligation bond debt b

|

724.9

|

330.8

|

–394.0

|

–54.4

|

|

Totals

|

$9,767.3

|

$9,418.9

|

–$348.3

|

–3.6%

|

The Governor's budget proposal for higher education reflects three broad themes: (1) a new approach to funding that emphasizes greater budgetary freedom for the public colleges and universities, (2) a concentration of budget solutions in the state's financial aid programs, and (3) the potential for substantial, largely unallocated budget reductions for the three public segments if the Governor's tax package is rejected.

New Approach Proposed for Segments' Budgets

A centerpiece of the Governor's higher education budget proposal is a "long–term plan" that would (1) shift more control over higher education funding from the state to the segments and (2) promise to the segments annual General Fund augmentations in exchange for improvement in certain types of outcomes. Critical details of the plan were not available at the time this report was prepared, but the basic elements of the plan include:

New Funding "Compact." Although the administration does not use the term "compact" to describe its proposed funding commitments, the proposal is similar to multiyear funding pacts developed between the segments and previous governors. Governor Brown's proposal includes no new cuts for the colleges or universities in 2012–13 (assuming passage of his tax package), and would provide annual General Fund increases of at least 4 percent for each of the segments beginning in 2013–14. These augmentations would be contingent on the segments' meeting improvement standards in such areas as graduation rates and enrollment of transfer students.

Affordability. The Governor proposes to "curtail" tuition and fee increases at the public segments. The budget assumes no such increases for 2012–13. However, the governing boards of UC and CSU have the authority to set tuition on their own.

Expanding the Base. The proposed budget moves into UC and CSU's base General Fund appropriations some costs that until now were treated separately. Specifically, in 2012–13 debt service payments for UC and CSU facilities, as well as the state's share of UC and CSU retirement costs, would be included in their respective base budgets. These amounts would not be separately adjusted in future years, although the entire, enlarged base budgets would be subject to the 4 percent annual increase described above.

Budgetary Flexibility. The Governor's budget seeks to increase flexibility for the segments in several ways. First, in moving retirement and debt service costs into the universities' base budgets, the Governor proposes to remove restrictions on those funds. In addition, the Governor's budget deletes longstanding provisional language and budgetary schedules that in prior budgets had tied portions of the universities' appropriations to specific programs or expenditures. Similarly, the budget consolidates over $400 million of CCC categorical funding into a single appropriation that can be used for a wide variety of purposes.

General Fund Solutions Concentrated In State Financial Aid Programs

The Governor's higher education budget focuses most of his proposed General Fund savings in the state Cal Grant programs. Figure 2 shows all the savings proposals, along with estimated savings and number of students affected.

Figure 2

Governor's Proposed General Fund Reductions to Financial Aid Programs

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Proposal

|

Savings

|

Estimated Number of Students Affected

|

|

Use federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families funds to offset Cal Grant costs

|

$736

|

—

|

|

Use Student Loan Operating Fund to offset Cal Grant costs

|

30

|

—

|

|

Raise Cal Grant grade point average requirements

|

131

|

26,600

|

|

Change Cal Grant award amount for independent, nonprofit colleges and universities from $9,708 to $5,472

|

112

|

30,800

|

|

Change Cal Grant award amount for private, for–profit colleges and universities from $9,708 to $4,000

|

59

|

14,900

|

|

Restore uninterrupted enrollment requirement for transfer entitlement awards

|

70

|

9,000

|

|

Phase out loan assumption programs for teachers and nurses

|

7

|

2,670

|

|

Maintain maximum student loan default rate at 25 percent

|

Minimal

|

Minimal

|

Large Fund Shifts Would Have No Programmatic Impact on Financial Aid . . . The first two proposals in Figure 2 represent $766 million in General Fund savings. However, these proposals would simply replace part of the Cal Grant programs' General Fund support with alternative fund sources, and thus would have no programmatic impact on financial aid programs.

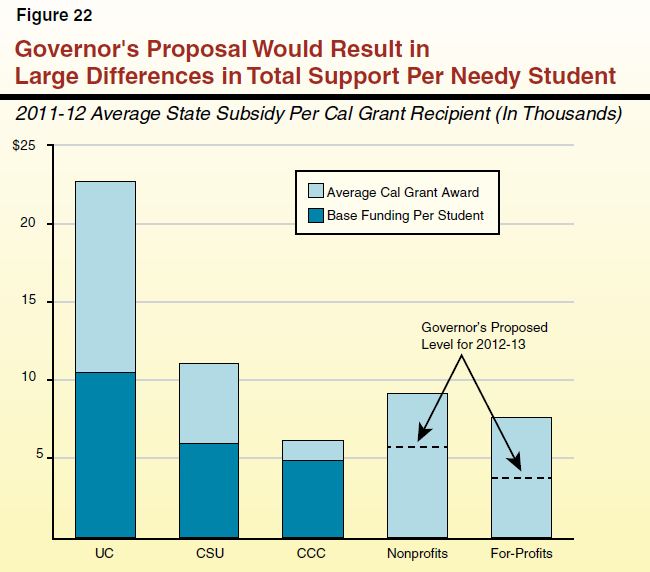

. . . But Cal Grant Changes Would Reduce or Eliminate Aid for Many Students. The Governor proposes several changes to the state Cal Grant program, which covers tuition and provides living stipends for eligible financially needy students. The proposed changes would save an estimated $372 million in 2012–13. They include:

- Raising GPA requirements for Cal Grant eligibility, which would reduce the number of eligible students and save an estimated $131 million.

- Reducing the Cal Grant award available to students at independent, nonprofit colleges and universities by 44 percent, for savings of $112 million.

- Reducing the Cal Grant award available to students at private, for–profit colleges and universities by 59 percent, for savings of $59 million.

- Restoring a requirement that recipients of transfer Cal Grant entitlement awards must enter a university within one year of completing their attendance at community college.

Several Other Financial Aid Proposals Provide Additional Savings. Other financial aid proposals in the Governor's budget include phasing out two loan assumption programs aimed at teachers and nurses, for estimated savings of $6.6 million in the budget year. The Governor also proposes to halt two anticipated changes in the administration of the Cal Grant programs.

Tuition Increases Could Increase Cal Grant Costs. The Governor's budget assumes neither UC nor CSU will raise their tuition for 2012–13. However, the CSU has already approved a 9.1 percent increase for fall 2012, and UC has not yet set a tuition level for fall. To the extent that the universities charge higher tuition in the budget year, Cal Grant costs will increase beyond the level assumed in the Governor's budget.

Trigger Cuts Could Reduce Higher Education Funding Almost 10 Percent

The Governor's overall budget package relies on a proposed November 2012 ballot initiative that would raise revenues through temporary income and sales tax increases. In the event that voters do not approve that proposal, the Governor proposes $5.4 billion in trigger cuts to take effect January 1, 2013. Included in that amount are $200 million unallocated reductions that would be imposed on both UC and CSU, as well as a nearly $300 million reduction in community college programs.

Tough Choices Ahead

The Governor's higher education proposal presents the Legislature with difficult choices as it balances the need for new budget balancing solutions with the state's longstanding principles of promoting access, affordability, and quality in higher education. The remainder of this report is intended to help the Legislature in making those choices. Specifically, the next section reviews how higher education has been affected to date by the state's recent budget challenges. After that, we offer our assessment and recommendations related to the Governor's key budget proposals for higher education.

In recent years, confusion has surrounded the question of how the state's fiscal difficulties have affected higher education budgets. To a large extent, this confusion results from dissimilar characterizations that focus on different funding sources or use varying baselines for their comparisons. There is no single correct way to describe higher education funding. However, below we present what we consider to be the most relevant aspects of higher education funding changes since 2007–08. That year was the last time that higher education budgets received standard baseline adjustments—enrollment growth and cost–of–living increases were funded at all three public segments, no large unallocated reductions were imposed, and no payments for new costs were deferred to future years.

General Fund Change Since 2007–08

As shown in Figure 3, annual General Fund support for higher education has varied by several billion dollars since 2007–08. Under the Governor's budget proposal, total General Fund appropriations for higher education in 2012–13 would be $9.4 billion, which is 21 percent lower than the 2007–08 total. General Fund reductions to the various segments and agencies over the five–year period would range from 12 percent (for CCC) to 100 percent (for the California Postsecondary Education Commission [CPEC], which was eliminated in November 2011). However, these net reductions are affected by several significant accounting changes, described below.

Figure 3

Higher Education General Fund Support

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2007–08 Actual

|

2008–09 Actual

|

2009–10 Actual

|

2010–11 Actual

|

2011–12 Revised

|

2012–13 Proposed

|

Change From 2007–08

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

UC

|

$3,257.4

|

$2,418.3

|

$2,591.2

|

$2,910.7

|

$2,273.6

|

$2,570.8

|

–$686.6

|

–21%

|

|

CSU

|

2,970.6

|

2,155.3

|

2,345.7

|

2,577.6

|

2,002.7

|

2,200.4

|

–770.2

|

–26

|

|

CCC

|

4,272.2

|

3,975.7

|

3,735.3

|

3,994.0

|

3,276.7

|

3,740.2

|

–532.0

|

–12

|

|

Hastings

|

10.6

|

10.1

|

8.3

|

8.4

|

6.9

|

8.8

|

–1.8

|

–17

|

|

CPEC

|

2.1

|

2.0

|

1.8

|

1.9

|

0.9

|

—

|

–2.1

|

–100

|

|

CSAC

|

866.7

|

888.3

|

1,043.5

|

1,251.0

|

1,481.7

|

567.9

|

–298.8

|

–34

|

|

GO bond debt service

|

496.2

|

591.4

|

762.0

|

809.3

|

724.9

|

330.8

|

–165.4

|

–33

|

|

Totals

|

|

|

|

|

$9,767.3

|

$9,418.9

|

|

–21%

|

Proposed Change to Treatment of Bond Debt Payments Skews Comparisons With Prior Years. As noted earlier, each year the state has funded general obligation bond debt service on facilities at the public segments through a General Fund appropriation that is not reflected in those segments' budgets. For UC, CSU, and Hastings College of the Law (Hastings) in the budget year, the Governor proposes to move that funding (totaling $388 million) into the segments' base budgets. Without this accounting change, reductions in direct General Fund appropriations over the period would be somewhat higher: 27 percent for UC, 32 percent for CSU, and 34 percent for Hastings.

Some CCC General Fund Costs Not Reflected in Annual Appropriations. For four of the fiscal years in Figure 3, the state deferred payment of additional CCC costs to the following fiscal year. In those years, the state achieved one–time General Fund savings ranging from $129 million to $340 million. However, those actions were not expected to affect CCC programs because funding was simply delayed to the next fiscal year, rather than eliminated.

Some General Fund Changes Result From Funding Swaps. In some cases, General Fund appropriations were simply replaced with other state appropriations, resulting in no net change in funding. This is a common occurrence in CCC's budget, as growth in local property taxes can offset General Fund costs. (Conversely, reductions in local property taxes can be backfilled with General Fund augmentations.) In addition, all three segments received federal stimulus funding that backfilled General Fund reductions for several years. For CSAC, General Fund support for the Cal Grant program has been offset by payments provided through the Student Loan Operating Fund. And for the budget year, the Governor has proposed to replace over $700 million in General Fund support for Cal Grants with federal funding redirected from the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program.

Other Funding Sources Also Support Higher Education

Several other sources of funding—primarily student tuition payments and, for community colleges, local property taxes—also support higher education's core education functions. ) shows all core funding for higher education. As shown in the figure, changes in total core funding during the period has varied considerably by segment. For example, under the Governor's 2012–13 proposal, UC's total core funding will have increased by about $400 million (9 percent) from 2007–08, while CSU's will have declined about $200 million (5 percent). As the figure shows, much of this difference results from tuition charges. (It should be noted that the proposed 2012–13 figures include general obligation bond debt service, which is not included for earlier years. If debt service is excluded from the universities' 2012–13 amounts, the change in core funding over the period would be an increase of 4 percent at UC and a reduction of 10 percent at CSU.) Overall, the Governor's 2012–13 budget proposal would increase total core funding for all of higher education about 1 percent above its 2007–08 level.

Figure 4

Higher Education Core Funding

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2007–08 Actual

|

2008–09 Actual

|

2009–10 Actual

|

2010–11 Actual

|

2011–12 Revised

|

2012–13 Proposed

|

Change From 2007–08

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California (UC)

|

|

|

|

General Funda

|

$3,257.4

|

$2,418.3

|

$2,591.2

|

$2,910.7

|

$2,273.6

|

$2,570.8

|

–$686.6

|

–21%

|

|

Net tuitionb

|

1,365.3

|

1,437.4

|

1,751.4

|

1,793.1

|

2,403.7

|

2,444.1

|

1,078.8

|

79

|

|

ARRA

|

—

|

716.5

|

—

|

106.6

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Lottery

|

25.5

|

24.9

|

26.1

|

27.0

|

32.9

|

32.9

|

7.4

|

29

|

|

Subtotalsa

|

($4,648.2)

|

($4,597.1)

|

($4,368.6)

|

($4,837.3)

|

($4,710.2)

|

($5,047.8)

|

($399.6)

|

(9%)

|

|

California State University (CSU)

|

|

|

|

General Funda

|

$2,970.6

|

$2,155.3

|

$2,345.7

|

$2,577.6

|

$2,002.7

|

$2,200.4

|

–$770.2

|

–26%

|

|

Net tuitionb

|

1,045.8

|

1,239.3

|

1,351.7

|

1,362.4

|

1,626.0

|

1,626.0

|

580.3

|

55

|

|

ARRA

|

—

|

716.5

|

—

|

106.6

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Lottery

|

58.1

|

42.1

|

42.4

|

42.4

|

47.8

|

47.8

|

–10.3

|

–18

|

|

Subtotalsa

|

($4,074.5)

|

($4,153.2)

|

($3,739.9)

|

($4,089.1)

|

($3,676.5)

|

($3,874.3)

|

(–$200.2)

|

(–5%)

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

|

|

|

General Funda

|

$4,272.2

|

$3,975.7

|

$3,735.3

|

$3,994.0

|

$3,276.7

|

$3,740.2

|

–532.0

|

–12%

|

|

Fees

|

281.4

|

302.7

|

353.6

|

316.9

|

353.9

|

359.2

|

77.7

|

28

|

|

LPT

|

1,970.8

|

2,028.8

|

1,992.6

|

1,959.3

|

2,107.3

|

2,101.1

|

130.3

|

7

|

|

ARRA

|

—

|

—

|

35.0

|

4.0

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Lottery

|

168.7

|

148.7

|

163.0

|

172.8

|

178.6

|

178.6

|

9.9

|

6

|

|

Subtotals

|

($6,693.1)

|

($6,455.9)

|

($6,279.6)

|

($6,447.0)

|

($5,916.4)

|

($6,379.0)

|

(–$314.0)

|

(–5%)

|

|

Hastings College of the Law

|

|

|

|

General Funda

|

$10.6

|

$10.1

|

$8.3

|

$8.4

|

$6.9

|

$8.8

|

–$1.8

|

–17%

|

|

Net tuitionb

|

21.6

|

26.6

|

30.7

|

36.8

|

36.5

|

34.8

|

13.2

|

61

|

|

Lottery

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.2

|

0.2

|

0.2

|

0.1

|

80

|

|

Subtotalsa

|

($32.3)

|

($36.8)

|

($39.1)

|

($45.3)

|

($43.6)

|

($43.8)

|

($11.5)

|

(35%)

|

|

California Postsecondary Education Commission

|

|

|

|

General Funda

|

$2.1

|

$2.0

|

$1.8

|

$1.9

|

$0.9

|

—

|

–$2.1

|

100%

|

|

California Student Aid Commission (CSAC)

|

|

|

|

General Funda

|

$866.7

|

$888.3

|

$1,043.5

|

$1,251.0

|

$1,481.7

|

$567.9

|

–$298.8

|

–34%

|

|

Otherc

|

—

|

24.0

|

32.0

|

100.0

|

62.3

|

766.4

|

766.4

|

N/A

|

|

Subtotals

|

($866.7)

|

($912.3)

|

($1,075.5)

|

($1,351.0)

|

($1,543.9)

|

($1,334.3)

|

($467.6)

|

(54%)

|

|

General obligation

bond debt servicea

|

$496.2

|

$591.4

|

$762.0

|

$809.3

|

$724.9

|

$330.8

|

–$165.4

|

33%

|

|

Grand Totals

|

|

|

|

|

|

$17,010.0

|

$197.0

|

1%

|

|

General Fund

|

$11,875.8

|

$10,041.4

|

$10,487.8

|

$11,552.9

|

$9,767.3

|

$9,418.9

|

–$2,456.8

|

–21%

|

|

Fees/tuition

|

2,714.1

|

3,006.1

|

3,487.3

|

3,509.2

|

4,420.1

|

4,464.1

|

1,750.0

|

64

|

|

ARRA

|

—

|

1,433.0

|

35.0

|

217.2

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

LPT

|

1,970.8

|

2,028.8

|

1,992.6

|

1,959.3

|

2,107.3

|

2,101.1

|

130.3

|

7

|

|

Lottery

|

252.4

|

215.8

|

231.7

|

242.4

|

259.5

|

259.5

|

7.1

|

3

|

|

Other

|

—

|

24.0

|

32.0

|

100.0

|

62.3

|

766.4

|

766.4

|

N/A

|

Larger Share of Costs Shifted to Students

Tuition Increases at All Public Segments. As a partial response to General Fund reductions, UC, CSU, and Hastings have increased student tuition charges, resulting in an increased share of total education costs being shifted to students. Community colleges fees are set in statute, and have also increased. These tuition and fee increases have resulted in additional revenue for the segments which partially backfills their General Fund reductions. (Increases in revenue from tuition and fees are reflected in Figure 4.) Figure 5 shows tuition and fee levels for resident and nonresident students at the public segments over the six–year period.

Figure 5

Higher Education Annual Tuition/Fees

Mandatory Charges per Full–Time Resident Student

|

|

2007–08

|

2008–09

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

2012–13 Proposed

|

Change From 2007–08

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Undergraduate

|

$6,636

|

$7,126

|

$8,373a

|

$10,302

|

$12,192

|

$12,192

|

$5,556

|

84%

|

|

Graduate

|

7,440

|

7,986

|

8,847

|

10,302

|

12,192

|

12,192

|

4,752

|

64

|

|

California State University

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Undergraduate

|

2,772

|

3,048

|

4,026

|

4,440a

|

5,472

|

5,472b

|

2,700

|

97

|

|

Teacher credential

|

3,216

|

3,540

|

4,674

|

5,154a

|

6,348

|

6,348b

|

3,132

|

97

|

|

Graduate

|

3,414

|

3,756

|

4,962

|

5,472a

|

6,738

|

6,738b

|

3,324

|

97

|

|

Doctoral

|

7,380

|

7,926

|

8,676

|

9,546

|

10,500

|

10,500b

|

3,120

|

42

|

|

CCC

|

600

|

600

|

780

|

780

|

1,080

|

1,380

|

780

|

130

|

|

Hastings College of the Law

|

21,303

|

26,003

|

29,383

|

36,000

|

37,747

|

43,486

|

22,183

|

104

|

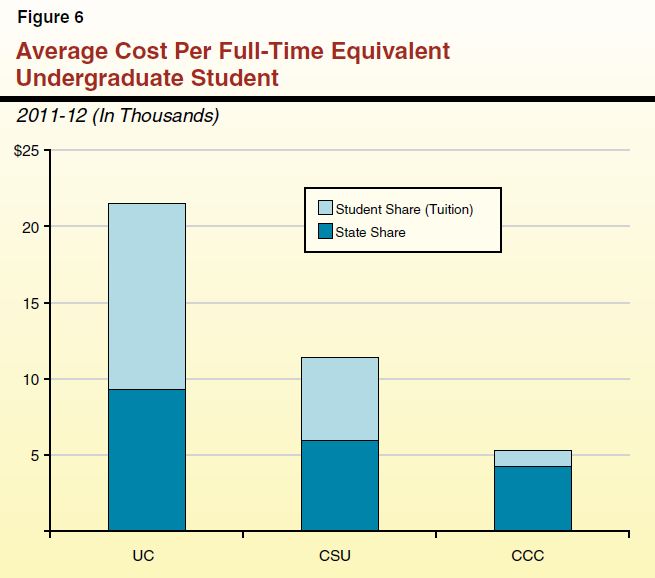

Students Paying Larger Share of Total Education Cost. The combined effect of reduced General Fund support and increased tuition and fees has been to shift a larger share of total education cost to students. Figure 6 shows our estimates of the share of education cost paid by undergraduate students at UC, CSU, and CCC. As shown in the figure, tuition represents about 57 percent of the UC's average cost to educate an undergraduate. The respective percentages for CSU and CCC are 48 percent and 20 percent. These shares are up from 2007–08, when UC and CSU students were paying less than a third of education cost, and CCC students were paying about a tenth. Still, the share of cost currently paid by California students remains at or below that paid by students at comparable institutions in other states. Undergraduate tuition at UC currently ranks in the middle of its group of five public comparison institutions. The CSU's tuition ranks second lowest among 16 public comparison institutions. And CCC fees remain the lowest in the nation.

Increased Spending On Financial Aid

Number and Size of Cal Grants Have Increased. Unlike most of the rest of higher education, the state's financial aid programs have experienced significant increases in General Fund support. The state Cal Grant program in particular has been one of the fastest–growing programs in the state budget, increasing from $812 million in 2007–08 to $1.5 billion in 2011–12. Two primary factors account for this growth:

- Most Cal Grants cover the entire tuition charge for eligible students attending UC or CSU. As a result, the tuition increases noted above have driven a commensurate increase in Cal Grant costs.

- The number of Cal Grants awarded has grown about 18 percent. Among other factors, the economic recession has increased the number of families that meet the program's financial need requirements.

Institutional Aid Also Increasing. In addition to Cal Grants, many financially needy students also receive institutional financial aid from their campuses. At UC and CSU, the total amount of institutional aid grows each time tuition is increased. Typically, of every $100 generated by a tuition increase, $33 is set aside for institutional aid. Overall, core funding for UC and CSU's institutional aid programs has increased from $822 million in 2007–08 to $1.6 billion in 2011–12.

The community colleges also provide a form of financial aid, which is the Board of Governors' (BOG) fee waiver program. This program waives community college fees for all students with financial need. Participation in this program has grown considerably, with well over half of all students paying no fees at all. (We discuss growth in BOG waivers in more detail in the "Financial Aid" section later in this publication.)

Enrollment Changes

The state Master Plan for Higher Education promises admission to all higher education applicants within defined eligibility pools. Specifically, the top one–eighth of high school graduates are eligible to attend UC, the top one–third are eligible to attend CSU, and all high school graduates (and others who can benefit from instruction) are eligible to attend CCC. However, demand for enrollment at the three segments depends on a number of factors, including the perceived cost and benefit of attendance versus other options. In addition, all three segments regularly seek to increase or decrease total enrollment to fit available capacity, using enrollment management tools such as application deadlines, program impaction, and course scheduling. Figure 7 shows annual full–time equivalent (FTE) resident enrollment at the three public segments.

Figure 7

Higher Education Enrollment

Resident Full–Time Equivalent Students

|

|

2007–08 Actual

|

2008–09 Actual

|

2009–10 Actual

|

2010–11 Actual

|

2011–12 Estimated

|

2012–13 Projected

|

Change From 2007–08

|

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Undergraduate

|

166,206

|

172,142

|

174,681

|

175,607

|

175,409

|

175,409

|

9,203

|

6%

|

|

Graduate

|

24,556

|

24,967

|

25,233

|

25,202

|

24,686

|

24,686

|

130

|

1

|

|

Health Sciences

|

13,144

|

13,449

|

13,675

|

13,883

|

14,017

|

14,017

|

873

|

7

|

|

Subtotals

|

(203,906)

|

(210,558)

|

(213,589)

|

(214,692)

|

(214,112)

|

(214,112)

|

(10,206)

|

(5%)

|

|

California State University

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Undergraduate

|

304,729

|

307,872

|

294,736

|

287,733

|

298,119

|

305,396

|

667

|

—

|

|

Graduate/post baccalaureate

|

49,185

|

49,351

|

45,553

|

40,422

|

41,881

|

42,904

|

–6,281

|

–13%

|

|

Subtotals

|

(353,914)

|

(357,223)

|

(340,289)

|

(328,155)

|

(340,000)

|

(348,300)

|

(–5,614)

|

(–2%)

|

|

CCC

|

1,182,627

|

1,260,498

|

1,258,718

|

1,230,649a

|

1,181,792a

|

1,158,156a

|

–24,471

|

–2%

|

|

Hastings

|

1,262

|

1,291

|

1,250

|

1,283

|

1,254

|

1,135

|

–127

|

–10

|

|

Totals

|

|

|

|

|

|

1,721,703

|

–20,006

|

–1%

|

In addition, a number of UC campuses have sought to increase their nonresident enrollment as a way to increase revenue. Although UC receives no state funding for nonresident students, the amount of their tuition payment ($35,070 for a nonresident undergraduate) exceeds the additional costs these students impose on UC. As a result, UC receives excess revenue from these students that it redirects to other purposes. Since 2007–08, UC's nonresident enrollment has increased by about a third, from about 17,500 FTE students to over 23,000 in the current year.

Programmatic Funding Has Declined, But Not as Much as State Funding

Taking into account the various funding and workload issues discussed above, we can determine how much core funding was available to cover the costs imposed by the average student enrolled at each of the three public segments. To arrive at these estimates for each segment, we combined all the core sources of higher education funding received by that segment, corrected it for deferrals and other anomalies, and divided this amount by the number of FTE students enrolled. We present these estimates in Figure 8. As the figure shows, per–student funding for each of the three segments has declined, even after accounting for the tuition increases and enrollment limitations which have been part of their response to budget constraints. Under the Governor's budget proposal, the total decline in programmatic per–student funding over the period would range from 5 percent to 11 percent, depending on the segment. None of these figures accounts for inflation, which has been low during this period.

Figure 8

Programmatic Funding Per Full–Time Equivalent Studenta

|

|

2007–08 Actual

|

2008–09 Actual

|

2009–10 Actual

|

2010–11 Actual

|

2011–12 Estimated

|

2012–13 Proposed

|

Change From 2007–08

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

UC

|

$21,253

|

$19,905

|

$18,556

|

$20,373

|

$19,636

|

$20,229b

|

–$1,023

|

–5%

|

|

CSU

|

11,306

|

11,062

|

10,445

|

11,867

|

10,303

|

10,088b

|

–1,217

|

–11

|

|

CCC

|

5,659

|

5,391

|

5,118

|

5,344

|

5,115

|

5,320

|

–340

|

–6

|

The segments have employed a variety of responses to contend with this reduced per–student funding. Among these responses have been limitations on employee salary increases, temporarily furloughing faculty and staff, tapping into budget reserves, reducing student support services, increasing class sizes and consolidating course sections, making greater use of part–time and adjunct faculty, streamlining administrative services, and other actions.

The Governor's budget proposal for higher education reflects a significantly revised approach in the relationship between the state and the higher education segments. In general, the proposed budget increases the segments' fiscal autonomy by reducing budgetary restrictions on their General Fund allocations. Alongside that increased autonomy the administration proposes annual augmentations to the segments' budgets in the out years, subject to as–yet–undefined performance standards. Below, we discuss four key components to the Governor's new budgeting approach: (1) linking accountability to annual base increases, (2) removing budgetary restrictions, (3) moving general obligation bond debt service payments in the universities' base budgets, and (4) forgoing out–year budget adjustments for university retirement costs. Overall, while we share the Governor's attention to accountability for the higher education segments, we are concerned that many aspects of his proposal would diminish the Legislature's oversight role as well as undermine its budgetary discretion.

Proposal Would Commit Additional Funding And Require Improved Outcomes

A central component of the Governor's higher education proposal is the commitment of 4 percent annual base increases for the public segments in exchange for meeting performance standards. To the extent those standards are met, augmentations would be provided in 2013–14, 2014–15, and 2015–16.

A Centerpiece of Higher Education Budget. The Governor relies on this funding–and–accountability proposal as an integral element of his higher education budget package. For example, the cost of the base increases is affected by his separate proposals (discussed below) to move debt service and retirement payments into the universities' base budgets. And all of these proposals presume that the state will no longer make unallocated (or even targeted) reductions to the universities' budgets. Moreover, the development of accountability mechanisms could help the administration's effort to justify its proposal to remove restrictions on the segments' base funding (also described below).

Key Details Lacking. At the time this report was prepared, the administration had not provided key details on its proposal. These include:

- Nature of the Agreement. Similar agreements between prior administrations and the segments generally took the form of uncodified agreements between the Governor and the universities. (The CCC generally has been excluded from these kinds of higher education compacts.) The Legislature has not been a party to those earlier agreements. In contrast, the Governor proposes that this agreement apply to all three public segments, and suggests that the Legislature would somehow be involved in its development. Meanwhile, it is our understanding that the Governor and the universities have already spent considerable time negotiating aspects of the proposal. It is not clear what role the Legislature would have at this point, and what form the agreement—if any—would take.

- Data and Data Collection. Under the Governor's proposal, higher education performance would be measured using "accountability metrics." The administration suggests as possible candidates a number of common higher education performance indictors: graduation rates, time to completion, enrollment of transfer students, faculty teaching workload, and course completion. However, it is not known which specific metrics would be used, how they would be defined, how data would be collected and by whom, what performance targets the segments would be expected to meet, and what level of overall performance would merit a base increase.

- Endurance of Accountability Provisions. The administration indicates that the proposed annual base increases would not be made if the Governor's proposed tax package were not approved by the voters. It is not clear whether the accountability provisions would also be suspended if the tax package failed. For the longer term, it is not clear whether the segments would be expected to maintain any particular performance levels once the final year of the proposed base increases had passed.

Legislature Has Shown Strong Interest in Accountability

The accountability proposal in the Governor's higher education budget is something of a departure from prior administrations, which have been notably resistant to the idea. In contrast, for the past decade the Legislature has spent considerable effort in trying to develop a higher education accountability framework. In fact, the Legislature has twice passed comprehensive higher education accountability legislation which was vetoed. More recently, the Legislature's Joint Committee on the Higher Education Master Plan identified serious shortcomings in the state's ability to oversee and set standards for the higher education system, and called for renewed efforts to develop goals and oversight mechanisms for higher education. A current legislative effort in this direction is SB 721 (Lowenthal), which would establish higher education goals and create a working group of representatives of the Legislature, administration, segments, and others to develop specific accountability metrics. Other current and recent legislative efforts have focused on similar objectives.

Future of Statewide Higher Education Data Unclear. Higher education oversight relies to a large extent on objective data that allows policymakers to monitor performance. Last fall, however, the Governor vetoed funding for CPEC, which the Legislature had charged with annually collecting and analyzing key data on California's higher education system and its students. (See our recent publication,

Improving Higher Education Oversight, for details on this and related issues.) The Legislature has held hearings and is considering possible legislative responses to address the data and oversight issues created by CPEC's demise.

Committing to Out–Year Base Increases Presents Problems

The higher education segments, like many state and local entities, have experienced unpredictable, significant changes to their budgets in recent years. It is understandable that those who receive state funding would desire greater budgetary stability and predictability. However, agreements such as the one proposed by the Governor have been tried before, and have proven unworkable. (For our assessment of earlier compacts, see

Higher Education Compacts: An Assessment, August 26, 1999, and "Higher Education Compacts," pages E149 – E156 of our Analysis of the 2005–06 Budget Bill.) By promising base increases to the three higher education segments (contingent upon their meeting certain performance targets), the Governor's proposal would encounter or create a number of problems, described below.

Budget Volatility Would Be Redirected and Amplified in Other Areas. The budget uncertainty experienced by the segments in recent years stems from underlying revenue volatility that affects the entire state budget. By promising to insulate the segments from these effects through stabilized budgets and annual base increases, the Governor's proposal would in effect concentrate the effects of revenue volatility in other areas of the budget.

Legislative Discretion Would Be Constrained. To the extent that the Governor's proposal was followed, the Legislature would have less discretion in allocating funds toward its priorities. For example, under the Governor's proposal the three segments would receive General Fund increases totaling about $350 million in 2013–14, which would reduce the amount of available revenue the Legislature could appropriate for other purposes. Moreover, the Legislature would not be able to reallocate funding among the segments in response to differing needs. For example, if enrollment demand at CSU increased more rapidly than the growth at UC, the Legislature would not be able to redirect funding to accommodate the shift in demand.

Conflicts With Codified Legislative Intent. As part of the 2009–10 budget package, the Legislature amended statute expressing its intent that the public universities (as well as most other state departments and the courts) should not receive automatic cost–of–living adjustments. The Governor's proposed annual 4 percent base increases would appear to conflict with that intent. (To the extent that the Governor's proposed accountability provisions were developed and rigorous, it might be argued that the base increases were not "automatic.")

Builds in Cost Increases. The Governor's proposal would build in cost increases for the universities—irrespective of underlying inflation, enrollment growth, or other cost drivers. At a time when cost savings are being sought in most areas of government, it is unclear why the Legislature would want to build in cost increases for higher education.

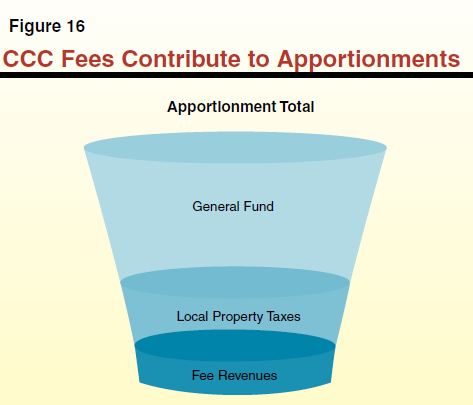

Unique Concerns for Community College Funding. As noted earlier in this publication, community college funding is subject to Proposition 98. As a result, General Fund support for CCC is intertwined with local property tax revenues received by the colleges, since Proposition 98 counts the combination of these two fund sources together. This means that an increase in local property taxes would result in a reduction in the amount of General Fund needed for a given level of Proposition 98 support. For this reason, simply increasing CCC's General Fund support by 4 percent (as described in the Governor's budget proposal) does not ensure any particular level of Proposition 98 resources for CCC, since property tax revenues do not necessarily move in tandem with General Fund revenues.

In response to our questions, the administration has clarified that it intends for CCC's 4 percent base increases to be applied to its entire Proposition 98 base (including both General Fund and local property taxes). However, this raises a new set of concerns. For example, if property taxes were to increase by less than 4 percent from one year to the next, fulfilling the Governor's promise of a 4 percent increase in CCC's Proposition 98 funding could cost well more than a 4 percent increase in CCC's General Fund appropriation. This is because the General Fund would have to make up for the inability of property taxes to cover their share of the overall 4 percent augmentation.

Another difficulty arises because CCC and K–12 schools together share total Proposition 98 funding. If the overall Proposition 98 minimum guarantee were not to increase by at least 4 percent in a given year, meeting the Governor's proposed increase for CCC would require either shifting some of K–12's share to CCC, or appropriating above the minimum guarantee (which would increase overall state costs).

LAO Recommendation: Pursue Accountability Without Automatic Augmentations

We believe the Governor's proposal provides a good opportunity to move forward with the Legislature's accountability efforts. However, we recommend that accountability metrics be used to help the Legislature in identifying policy and budget priorities, rather than as a mechanism for triggering the preset 4 percent augmentations for the segments.

Invite Administration to Join Legislature's Accountability Efforts. As noted above, the Legislature has spent over a decade pursuing higher education accountability efforts. It has been part of a national dialogue on the topic, and its legislative efforts have taken advantage of lessons learned along the way. At the same time, it has become clear that the most successful accountability systems in other states have had strong engagement and support from both the executive and legislative branches. The Governor's interest in accountability therefore provides a good opportunity for the Legislature and administration to jointly make progress in developing a statewide higher education accountability system. At the same time, accountability remains a difficult and elusive goal, so it would be unrealistic to expect to complete such an effort as part of this year's budget process. Instead, we recommend that these efforts be directed through policy committees and the regular legislative process.

Reject Commitment to Base Increases. As noted above, promising out–year base augmentations to the segments would complicate budgeting in other areas, reduce the Legislature's discretion in allocating resources, and create particular difficulties within Proposition 98. For these reasons, we recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor's approach of promising base increases to the segments. Instead, we recommend the Legislature continue its current practice of making higher education funding decisions as part of each year's budget deliberations.

Somewhat related to the administration's accountability proposal are a variety of changes that would expand the segments' freedom to decide how their funding should be used. The administration asserts that these various proposals work together to give the segments the incentives and flexibility to make better use of their base funding.

Removal of UC and CSU Earmarks

Background. Typically, the annual budget act includes a number of restrictions on UC's and CSU's General Fund appropriations. For example, recent budget acts have required UC to spend a certain portion of its funding on specified research programs, and have required both UC and CSU to direct a portion of their funding to student outreach programs. Other provisions have linked a portion of the universities' General Fund support to start–up costs at particular campuses. These and other "earmarks" for UC and CSU funding have varied over the years in keeping with the Legislature's and Governor's particular concerns at the time. Figure 9 lists the various earmarks for UC and CSU in the 2011–12 Budget Act. (We consider the setting of enrollment targets to be a special category and address it separately in a following section.)

Figure 9

UC and CSU General Fund Earmarks

From 2011–12 Budget Act (In Millions)

|

UC

|

CSU

|

|

Separately Scheduled General Fund Appropriations

|

Separately Scheduled General Fund Appropriations

|

|

Charles R. Drew Medical Program

|

$8.7

|

Assembly, Senate, Executive, and Judicial Fellows Programsa

|

$3.0

|

|

AIDS research

|

9.2

|

Lease–purchase bond debt service

|

65.5

|

|

Student Financial Aid

|

52.2

|

|

|

|

San Diego Supercomputer Center

|

3.2

|

|

|

|

Subject Matter Projectsb

|

5.0

|

|

|

|

UC Merced

|

15.0

|

|

|

|

Lease–purchase bond debt service

|

202.2

|

|

|

|

Provisional Language

|

Provisional Language

|

|

Energy service contracts

|

$2.8

|

Science and Math Teacher Initiative

|

$2.7

|

|

COSMOS

|

1.9

|

Entry–level master's degree nursing programs

|

0.6

|

|

Science and Math Teacher Initiative

|

1.1

|

Entry–level master's degree nursing programs

|

1.7

|

|

PRIME

|

2.0

|

Baccalaureate degree nursing programs

|

0.4

|

|

Nursing enrollment increase

|

1.7

|

Baccalaureate degree nursing programs

|

3.6

|

|

2/12/09 MOU for service employees

|

3.0

|

Student financial aid

|

33.8

|

Governor's Proposal. The Governor's budget eliminates virtually all earmarks from UC and CSU's budgets. The administration asserts that this will provide the universities with greater flexibility to manage recent unallocated budget reductions.

LAO Assessment. Unlike most state agencies, UC and CSU are governed by independent boards that make various decisions about how the universities will spend their resources, including the number of students that will be admitted; the number of faculty, executives, and other employees on the payroll; the salaries and benefits to be provided to those employees; tuition levels paid by students; the amount of tuition revenue redirected to financial aid; and other choices. Given the delegation of so much budgetary authority to UC and CSU, the state has relied on earmarks as one way to ensure that its key concerns and priorities are addressed with the funding it appropriates to the universities. The inclusion of earmarks in the budget bill also provides a clear public record of budgetary allocations and expectations. The Governor's proposal would eliminate this budgetary tool, and thus would reduce the Legislature's ability to ensure that state funds are spent in a manner consistent with its intent.

Recent budget reductions have made it more difficult for the universities to fulfill the public missions assigned to them. While they are able to absorb some budget reductions by drawing on funding reserves and increasing efficiencies, reductions of the magnitude in the current year—$750 million per segment—require a prioritization and narrowing of some activities. In this context, the Governor's budget proposal would provide the universities with $4.8 billion of General Fund support, while deferring virtually all spending decisions to the universities.

Recommend Legislature Reevaluate Requirements for Universities' Spending. We think it is reasonable for the Legislature to make some adjustments to the conditions it places on funding for UC and CSU, given recent budget reductions. (Such adjustments should take into account the net change in UC's and CSU's programmatic funding, rather than simply the change in General Fund support.) However, rather than simply abandoning all earmarks in the universities' budgets, we recommend that the Legislature reevaluate budgetary earmarks on a case–by–case basis. In some cases, the Legislature may decide that a particular earmark is no longer a priority. In others, the Legislature may wish to keep or change or add an earmark. To help in evaluating potential earmarks, the Legislature may wish to develop guidelines that could be used for the budget year and beyond. For example, the Legislature might decide to approve only earmarks that serve a broader state purpose. To the extent that the Legislature chooses to retain any earmarks, the budget bill should be amended accordingly.

CCC Categorical Flexibility

The Governor's budget proposal would move $412 million of CCC categorical funding into a single "flex item" that districts could use for a wide array of purposes. In recent years we have encouraged the Legislature to loosen categorical restrictions on CCC funding, while assigning broader yet defined purposes for some funding. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature consider alternative approaches to the Governor's proposal that would maintain somewhat more focus for this funding on key legislative priorities. (We discuss this proposal in detail later in the "Community Colleges" section of this report.)

Elimination of Enrollment Targets

Proposal. One of the key measures of workload at the higher education segments is FTE enrollment. In most years, each segment's budget is tied to a specified enrollment target. For UC and CSU, the budget act typically includes an enrollment target for each segment and provisional language that would reduce the segment's General Fund support in proportion to any enrollment shortfall relative to its target. For CCC, enrollment targets are somewhat more complicated. Specifically, the budget drives statutory formulas and calculations which result in enrollment targets for each of the state's 72 community college districts. The amount of apportionment funding received by each district depends on the number of students they enroll, up to (but generally not beyond) that enrollment target. Although not specifically included in the budget act, an overall enrollment target for the entire CCC system is calculated by the Department of Finance (DOF).

The Governor's budget proposal would eliminate enrollment targets for all three segments. For UC and CSU, this means simply omitting provisional language which typically would reference an enrollment target. For CCC, the administration has introduced trailer bill language that would suspend or eliminate existing formulas for allocating apportionment funding.

Assessment. Enrollment levels are a fundamental building block of higher education budgets. They bear a direct relationship to access provided to the higher education system; they are a central cost driver for the segments; and they affect other costs, such as state financial aid. For these reasons, enrollment targets have been a major concern of the Legislature in recent years.

Changes to the segments' overall funding raise the question of what changes, if any, should be made to their enrollment levels. In some cases, the Legislature has reduced enrollment targets in recognition of funding reductions. In other cases, the Legislature has directed the segments to accommodate funding reductions without reducing enrollment below budgeted levels.

The Governor's proposal would allow the segments to make their own decisions about how many students to enroll with the funding available to them. In theory, the segments could significantly reduce the number of students served, thus raising the average amount of funding available per student. This funding could be used to increase salaries for faculty, staff, and executives—a goal all three segments have expressed at various times. Or they could reduce the number of undergraduates served, and use the funding to add a smaller number of higher–cost graduate students. Alternatively, the segments could employ an enrollment reduction to shift a larger amount of their budgets away from direct education costs toward research or other noninstructional programs. These kinds of decisions have implications not just for the costs that the segments pay to educate students; they also could have a profound effect on the level of access provided at each segment.

Recommend Rejection of Governor's Proposal. We recommend the Legislature reject the Governor's proposal to eliminate enrollment targets. Instead, we recommend the Legislature restore provisional language that specifies enrollment targets for UC and CSU, and reject proposed trailer bill language that would decouple community college funding from enrollment. As a starting point, the Legislature may wish to consider maintaining each segment's enrollment at its current–year level, given that the budget proposes roughly flat funding for each segment. To the extent that the Legislature chooses to significantly reduce or increase a segments' budget, it may wish to modify the enrollment targets. Alternatively, the Legislature may wish to require the segments to achieve greater efficiencies without reducing enrollment.

The Governor proposes major changes to the manner in which both general obligation and lease–revenue bond debt is repaid for higher education. These changes would apply to UC, CSU, and Hastings, but not to CCC.

Background

General Obligation Bond Debt Service. The California Constitution requires that general obligation bonds be approved by a majority of the voters and sets repayment of this type of debt before all other obligations of the state except those related to K–14 education. State bond acts continuously appropriate this debt service from the General Fund. Funding to repay this debt is not included in direct budget appropriations for the higher education segments. Due to the varying debt service payment schedules related to different projects, general obligation bond debt payments the state makes on behalf of the segments fluctuate from year to year.

Lease–Revenue Bond Debt Service. Lease–revenue bonds are also used to finance infrastructure projects for the segments. These bonds may be authorized with a majority vote of the Legislature, and their debt service is covered from the future rental payments on the facilities that are built. Funding for these rental payments is included in the segments' budget appropriations. The funding, however, is restricted specifically for paying the debt service, and is adjusted each year in the Governor's budget to account for fluctuations in the amount of debt to be repaid.

Governor Proposes Major Modifications to Debt Payment Process

Funding for General Obligation Bond Debt Shifted Into Segments' Base Budgets. First, the Governor proposes to increase UC, CSU, and Hastings' base budget appropriations to reflect what the administration estimates would be the 2012–13 general obligation bond debt service payments related to each segment's capital projects. This means the segments would receive base budget augmentations of $196.8 million, $189.8 million, and $1.8 million, respectively. Debt service payments would still be continuously appropriated from the General Fund. However, proposed budget bill language would require that the segments reimburse the General Fund for making general obligation bond debt payments related to their capital projects. The State Controller would transfer the necessary amounts from the segments' General Fund support.

By design, the proposal does not result in increased General Fund costs in the budget year. For example, under the Governor's proposal, UC's budget would be increased by $196.8 million, whereas a similar amount would be transferred out of its budget appropriation by the State Controller. In effect, this part of the proposal merely subjects general obligation bond debt repayment to the process already in place for paying lease–revenue bond debt.

No Restrictions or Future Adjustments on Debt Funding. After making adjustments for 2012–13, the Governor further proposes not to adjust the segments' budget appropriations in the future to reflect any changes in lease–revenue and general obligation bond debt service costs, nor to restrict the funding provided to the segments for the purpose of repaying debt. The amount of funding provided to the segments in 2012–13 for both types of debt service, however, would grow in the out–years to the extent the segments receive general increases in their budgets. For example, the administration proposes minimum 4 percent annual increases to the segments' base budgets for 2013–14 through 2015–16. (These proposed annual increases are discussed in more detail in a separate section of this report.)

No Proposed Changes to State Review Process. According to the administration, the current process through which both the administration and the Legislature review and approve state–funded capital projects for the segments would remain the same under the Governor's proposal. The administration asserts that the segments would still have to request approval from the administration and the Legislature for any projects to be funded with general obligation bonds approved by the voters. Moreover, the administration and the Legislature would still need to review and approve any future lease–revenue projects. Figure 10 summarizes the key elements of the Governor's proposal.

Figure 10

Key Elements of Governor's Proposal

|

|

- All debt funding for 2012–13 included in universities' base appropriations.

|

- Funding not restricted for debt service.

|

- No future adjustments specifically for debt service.

|

- Base appropriations proposed to increase by 4 percent annually from 2013–14 though 2015–16.

|

- No proposed changes to state review process of capital projects.

|

Potential Effects on Debt Service Costs Unclear

Governor's Plan Could Provide Incentives for Segments to Economize on Projects. Because funding for debt service payments is currently budgeted separately from other operations and because their debt service payments are automatically adjusted each year, the segments' general–purpose base budgets are unaffected by debt costs. For this reason, the current approach provides no incentive for the segments to limit the number and scope of capital projects that they submit to the administration and the Legislature. In fact, in past budget analyses we have found that the scope of projects submitted by the segments often exceeds what we would consider to be necessary. For example, our reviews of the segments' capital outlay budget proposals in recent years have frequently identified what we believe are excessive requests for additional space compared to the stated needs.

By funding capital debt service and operating costs from a single, finite appropriation, the Governor's proposal attempts to create an incentive for the segments to prioritize and limit capital projects. In other words, a dollar from a segment's base budget that is spent on debt service would be one dollar less to spend on operations. This would highlight for the segments the trade–offs between spending on operations versus infrastructure—as well as highlight the fact that infrastructure spending can increase operational costs once projects are complete.

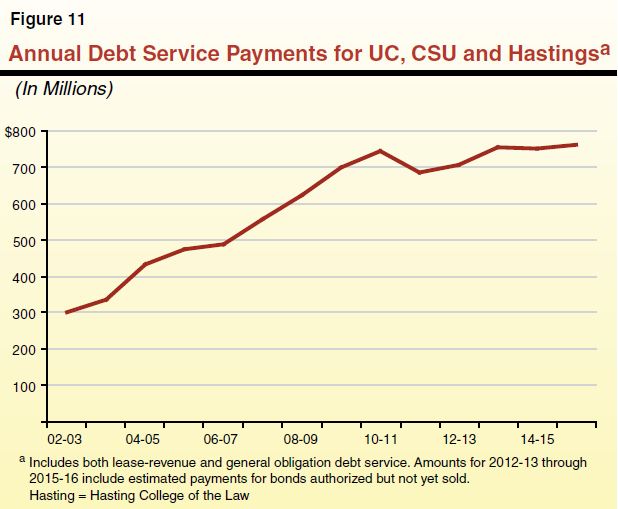

But Future Fiscal Implications Uncertain. As shown in Figure 11, annual debt service payments related to infrastructure projects for UC, CSU, and Hastings have more than doubled over the past ten years—growing from about $300 million in 2002–03 to an estimated $708 million for 2012–13. This means that debt service payments have risen on average by about 9 percent per year, although in recent years they have declined slightly. (At the time this analysis was prepared, estimates of general obligation bond debt payments by segment were not available prior to 2010–11—therefore, we could only analyze historical debt spending for all segments combined. Nevertheless, there could be important variations by segment.)

It is difficult to predict how the segments' state–funded debt payments could change in the future. As the figure indicates, annual debt service payments on existing bonds (including our estimates for bonds that have been authorized but not yet sold) are expected to increase slightly through 2015–16. Whether the segments' debt costs would further increase relative to these existing obligations would largely depend on what future capital projects the segments request, whether the Legislature approves those projects, or, as discussed further below, what actions UC takes to issue its own debt. For UC, there also could be some debt payment reductions under the Governor's plan. According to the university, it could potentially refinance some of the existing lease–revenue bond debt related to UC facilities and lower its debt service primarily by extending repayment periods. Given these actions cannot be predicted in advance, it is unclear what effect the Governor's proposal would have on debt service costs.

Legislature Would Lose Significant Control Over University Budgets and Projects

Shifting Funding Transfers Control Over Budgets to Universities. The Governor's proposal would relinquish significant control over the universities' budgets. In the future, the Legislature would no longer be responsible for allocating funding for support operations versus infrastructure debt service. This is particularly troublesome since it is not clear whether the amount of debt funding that would be shifted into the universities' budget is an appropriate amount to support the universities' long–term infrastructure needs. Rather, the Governor proposes to shift an amount that is related specifically to one fiscal year. It appears the administration did not perform an analysis to determine how this amount of funding relates to what the universities might reasonably require in the long term. For UC, for example, the amount of funding would be equivalent to roughly $2,000 per student. Without additional information on reasonable debt costs per student, it is unclear whether this amount of funding is appropriate—or whether is is too low or too high. Shifting this amount of control over spending priorities to the universities raises serious questions given that they are statewide, public institutions.

No Guarantee That Projects Would Still Be Submitted for Legislative Review. The administration asserts that the segments would still request bond funding for capital projects from the Legislature. While this could be the case, it is also possible that the segments could circumvent the capital outlay budget request process. For instance, UC could potentially issue its own bonds for projects for which it currently requests state bond financing. This means that in the future UC might not submit many (or even any) state–related project proposals to the Legislature for it to review. (The CSU's ability to issue bonds appears more limited, so it would probably still request bond funding from the state.) Under such a scenario, the Legislature would not have any formal role in reviewing projects to ensure that they are consistent with its priorities. For example, the Legislature would not have the option of directing bond financing toward instructional facilities instead of research buildings. Instead, the choice of projects would be left entirely up to UC. Although it is unclear at this time whether UC could in fact take this approach, we find that the potential loss of Legislative oversight of state–related projects to be a serious concern.

Statewide Infrastructure Planning Could Be More Difficult

As we noted in our recent publication—A Ten–Year Perspective: California Infrastructure Spending (2011)—the Legislature's decision making process for all infrastructure projects remains fragmented. Proposals are reviewed and funded in isolation, and there is little examination of how competing proposals fit within the context of overall state infrastructure needs, priorities, and funding capabilities. In our view, the Legislature cannot effectively assess the trade–offs among different proposals without sufficient perspective on the infrastructure demands across various capital outlay programs. The Governor's proposal to devolve the responsibility for debt service payments for UC, CSU, and Hastings' capital projects to the respective segments would likely exacerbate this problem. Should the Legislature at some point in the future wish to prioritize construction projects at one segment (or another state program area) over projects for another segment, it could not easily shift General Fund support to account for the effect of that shift on debt service costs. This could occur, for example, if the Legislature were to enact new policies encouraging distance learning that would reduce the need for higher education facilities.

Recommend Rejecting Governor's Approach

While we agree with the administration that certain aspects of the current state debt financing system for the segments does not always provide the right incentives, overall we find that the Governor's proposal does not fully address these issues and makes the Legislature's future capital outlay budgeting decisions for the segments (and the state as a whole) even more difficult. Moreover, we find that some aspects of the Governor's proposal regarding Legislative oversight of the segments' state–related projects raise serious concerns. For these reasons, we recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor's proposed approach. Specifically, we recommend reducing the General Fund appropriations for UC, CSU, and Hastings by $196.8 million, $189.8 million, and $1.8 million, respectively to take debt service for general obligation bonds out of their budgets (as well as deleting the associated budget language). Further, we recommend restricting the amounts proposed for lease–revenue bond debt service in 2012–13 to that purpose only. These actions would result in no net changes in General Fund spending in 2012–13.

The Governor proposes major changes to the way in which some retirement costs are funded for higher education. For CSU, the Governor proposes to no longer make base adjustments to reflect changing retirement costs. For UC, the Governor proposes (1) a $90 million base augmentation that could be used for pension costs or other purposes, and (2) no out–year adjustments for retirement costs. The budget proposes no changes to the way retirement is funded for CCC.

Background

CSU Pension Benefits. CSU employees are members of the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS)—the same retirement system to which most state employees belong. Funding for this system comes from both employer contributions and employee contributions. Each year, as is the case with other state departments, CSU's employer contributions to CalPERS are charged against its main General Fund appropriation. The employer contribution is based on a percent of employee salaries and wages that is determined by CalPERS and specified in the annual budget act. The Governor's budget annually adjusts CSU's main appropriation to reflect any estimated changes in the employer contribution. For example, the Governor's budget reduces CSU's main appropriation by $38 million due to a lower employer rate and lower payroll costs in the current year. The CSU is expected to contribute $404 million to CalPERS in 2012–13.