Currently, the state park system, administered by the Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR), contains 278 parks and serves over 70 million visitors a year. The 2012–13 Governor's Budget includes proposals to address some of the funding challenges currently faced by parks, including the continuation of the plan to close up to 70 state parks by July 2012. However, the Legislature and stakeholders have expressed interest in identifying alternative ways to prevent park closures and, more importantly, help ensure that the park system is adequately maintained and operated in the future.

In this report, we evaluate various options that could be adopted to reduce costs or increase revenue for the state park system, including the inherent trade–offs associated with each option. Based on this analysis, we recommend specific steps to help maintain the park system during these tough fiscal times. In developing these recommendations, we attempt to find a balance between the need to achieve budgetary savings or increase park revenues and the goal of preserving public access to the parks. While we recognize that some parks may need to be closed in the short run, we believe that our recommendations would reduce the number of parks that would need to be closed in the long run. Specifically, we propose the following:

- Transferring the ownership of some state parks to local governments.

- Eliminating the use of peace officers for certain park tasks (such as providing information to visitors and leading school groups on park tours).

- Allowing private companies to operate some state parks.

- Increasing park user fees and shifting towards entrance fees, rather than parking fees.

- Incentivizing park districts to more effectively collect park user fees.

- Expanding the use of concessionaire agreements.

In adopting the 2011–12 budget, the Legislature reduced General Fund support for the state park system by $11 million. The 2012–13 Governor's budget proposes an additional reduction of $11 million in General Fund support, thereby increasing the ongoing reduction to the park system to $22 million. According to DPR, which manages the state park system, it will need to permanently close up to 70 parks by July 2012 in order to achieve the assumed savings. However, the Legislature and stakeholders have expressed interest in identifying alternative ways to prevent park closures and, more importantly, help ensure that the park system is adequately maintained and operated in the future.

In this report, we (1) describe the California park system and its role in providing recreation and cultural and environmental preservation for the state, (2) review park operations and how these operations are funded, (3) evaluate various strategies to reduce costs or increase revenue for the state park system, and (4) recommend actions that could be taken to help maintain the park system.

Overview of the State Park System

California's state park system consists of 278 state parks that totaled more than 1.3 million acres of property in 2009–10. State parks vary widely by type, from state beaches to museums, golf courses, ski runs, historical and memorial sites, forests, grass fields, rivers and lakes, and rare ecological reserves. The size of each of park also varies, ranging from less than one acre to over 585,000 acres. In addition, many parks have their own campsites, water and waste water systems, generators or power supply, visitor information centers, and ranger stations. Figure 1 summarizes the diversity of the state park system.

Figure 1

The State Park System Is Diverse

|

Asset

|

|

|

Miles of coastline

|

280

|

|

Miles of lake and river frontage

|

625

|

|

Miles of trails

|

15,000

|

|

Campsites

|

3,000

|

|

Recorded historic buildings

|

3,188

|

|

Archeological sites

|

10,271

|

|

Archaeological specimens

|

2,000,000

|

|

Museum objects

|

1,000,000

|

The number of people who visit the state parks each year has remained relatively stable during the past five years at over 70 million visitors. In addition, the parks, particularly those with historic sites or unique ecosystems (such as tide pools), are popular destinations for school field trips. For schools that are unable to have their students travel to a state park, DPR offers online curriculum and videoconferencing between classes and rangers at seven state parks.

Under existing state law, DPR is required to administer, protect, and develop the state park system, as well as ensure that the parks provide recreation and education to the people of California. The DPR is also required to help preserve the state's extraordinary biological diversity and its most valued natural and cultural resources.

State Park Operations

In many ways, the operation of a state park requires many of the same services as a small city, such as electricity, water, garbage disposal, and sewage treatment. A state park also needs to maintain its buildings, roads, and trails and employ peace officers to ensure the safety of its visitors.

State Employees Operate Most State Parks. The DPR's central administration office (located in Sacramento) consists of about 1,000 permanent state employees who are responsible for various administrative activities, including planning and budgeting, grants administration, and personnel management. The central administration office is also responsible for various statewide programs, such as providing specific areas for off–highway vehicles (OHV) to operate and identifying and protecting places of historical significance.

In addition to the staff in the central administration office, there are staff in the field responsible for operating the parks. The state park system is divided into 20 districts (or geographic clusters) that share resources across multiple parks. (Although the state park system also consists of five districts that contain OHV parks, the focus of this report is on the state's non–OHV parks.) The DPR assigns state employees to a particular district—rather than to a specific state park and they are responsible for maintaining all of the state park assets in that district. Districts are staffed by superintendents, park rangers, maintenance workers, and other state employees who perform various administrative and specialized activities (such as archaeologists). The number of permanent staff used to operate a district varies significantly, depending mainly on the geographic and unique features of the parks in a district. For example, the smallest park district (Capitol District) has 95 permanent positions to operate eight parks totaling 322 acres. In contrast, the largest park district (Colorado Desert District) operates six parks totaling 622,000 acres with only 68 permanent positions.

State staff in the field include over 750 superintendents and rangers responsible for park operations, safety and law enforcement, assisting with program management, educational services, resource protection and management, and supervision of seasonal staff. All superintendents and rangers are sworn peace officers who have undergone specialized training, receive higher pay, and more generous retirement benefits than non–sworn park staff. The system also includes about 650 maintenance workers who perform routine maintenance tasks (such as cleaning, stocking, painting, and repairing park facilities) and over 200 specialists (such as historians, environmental scientists, and archaeologists) who research, identify, and maintain artifacts and historical and environmentally sensitive sites. In addition, about 130 state employees perform various administrative duties such as budgeting, staff services, and training.

The DPR also hires roughly 800 employees on a part–time and seasonal basis to collect entrance fees, lead tours, plan educational programs, and work in visitor centers.

State Contracts With Some Entities to Operate Parks. Under current state law, the DPR can enter into contracts with public agencies for the care, maintenance, or operation of a park. Currently, the department has about 50 operating agreements with local government entities (such as cities), for the partial or whole operation of a state park. In addition, Chapter 450, Statues of 2011 (AB 42, Huffman), permits DPR to enter into an unlimited number of similar operating agreements with nonprofit agencies. Prior to Chapter 450, the department was only authorized to enter into two operating contracts with nonprofit organizations—specifically in regards to the El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park and the Marconi Conference Center.

We also note that the operation of two state parks involves nonprofit park operators contracting with for–profit concessionaires to create a somewhat hybrid management model. For example, although the nonprofit Crystal Cove Alliance operates the Crystal Cove State Park through a concession agreement, it contracts with a private company to provide food services. This type of approach gives non–state entities additional flexibility to acquire the needed resources and expertise to operate a state park.

Volunteers Help Operate State Parks. In 2010, about 34,000 state park volunteers worked over one million hours by serving as tour guides, history and nature specialists, laborers for light cleanup and preservation projects, and campsite hosts. According to the department, this level of volunteer work is estimated to be worth over $20 million a year. (This estimate assumes a labor cost of $21 per volunteer hour, which is based on an average of production and non–supervisory labor costs in the private sector as reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.) The DPR currently invests about 90,000 staff hours annually (at an estimated value of about $7 million) to train and operate its volunteer program.

Concessionaires Provide Some Visitor Services. State law allows DPR to enter into contracts with concessionaires—persons, corporations, partnerships, and associations—for certain visitor services that DPR generally does not provide. These contracts typically include the provision of food services, recreation gear rentals, retail, golf courses, marinas, tours, and lodging. Currently, DPR maintains about 200 different concession contracts statewide. Under most circumstances, the concessionaires pay the state rent or a certain percentage of the revenue they generate. However, a local government entity or a nonprofit organization that provides a service in high demand (such as park tours or an environmental education information and research center) and does not create a profit, would typically not be required to make such a payment to the state. To the extent that these particular entities actually earn a profit, the contract requires that it be reinvested in the concession or park. For 2011–12, the state is expected to receive $12.5 million from concessionaires.

State Park Funding

Major Funding Sources. The state park system receives funding from three primary sources:

- General Fund. The state park system is partly funded from the state General Fund. However, as we discuss in more detail below, the amount of General Fund support for the parks has declined in recent years.

- User Fees. Visitors to many of the state parks are generally required to pay user fees to help support various operation and maintenance costs. Of the parks that charge a day use fee, three–fourths charge a parking fee for visitors who use a park's parking lot, while the remaining one–fourth charge an entrance fee. Fees are also sometimes charged for specific recreational activities that are offered at a state park, such as the use of overnight campsites. Actual fee levels can vary based on park location, demand for visitation, level of service provided, and the time of year. The revenues collected from the various user fees are deposited into the State Park Recreational Fund and allocated each year to DPR's central administration and the different park districts. Figure 2 summarizes the range of park fees for 2011–12.

- Special Funds. State parks also receive support from various special funds, including rent paid by state park concessionaires, revenues from the state boating gas tax, federal highway dollars for trails, and various state revenue sources earmarked for natural resource habitat protection (such as the Habitat Conservation Fund, the California Environmental License Plate Fund, and a percentage of the state cigarette and tobacco product tax). The DPR also receives state bond revenue that funds one–time infrastructure projects.

Figure 2

2011–12 State Park Fees

|

|

|

|

Day use/parking (per car)

|

$4 to $15

|

|

Camping (per site)

|

9 to 35

|

|

Boat launching

|

5 to 8

|

|

Museums/historic sites (per person)

|

2 to 9

|

|

Annual passes

|

75 to 125

|

For 2012–13, the Governor's budget proposes $329 million in total expenditures for state park operations and facilities. (The proposed budget also provides $103 million to DPR for OHV and local assistance grant programs.) This amount represents a decrease of $93 million, or 22 percent, below the estimated level of current–year spending for the state parks. This reduction primarily reflects a reduction in planned bond expenditures and in General Fund support, which we discuss in more detail below. Specifically, the $329 million proposed for the parks includes $112 million (34 percent) from the General Fund, $80 million (24 percent) from fees paid by park visitors, and $137 million (42 percent) in special funds.

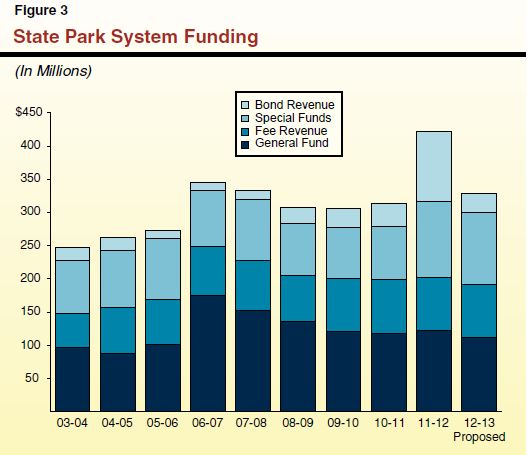

Historic Funding Trends. The level of funding proposed by the Governor for 2012–13 is generally consistent with the levels provided during the past decade. Figure 3 shows total expenditures (by fund source) for state parks since 2003–04. As shown in the figure, with the exception of 2011–12, when a large amount of bond funds were provided to the parks on a one–time basis, funding for the parks has remained relatively flat since 2006–07.

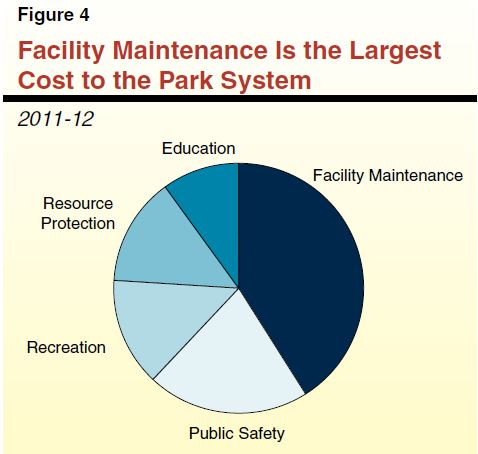

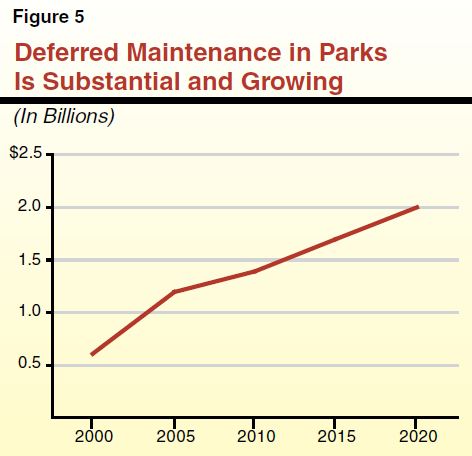

Major Cost Factors. Figure 4 summarizes the major costs for the park system in 2011–12. As shown in the figure, roughly 40 percent of the funding provided to the state parks is spent on maintaining park facilities. This includes costs for routine maintenance (such as removing trash and cleaning bathrooms), as well as making repairs to infrastructure. About 20 percent of funding for the parks is spent on providing public safety in the parks, primarily for park rangers. Other park expenditures are for recreation (such as trail maintenance), resource protection (such as the removal of invasive species), and providing educational services to the public. In addition to these "funded" costs, DPR estimates the parks have a backlog of $1.3 billion in deferred maintenance projects that is projected to grow to $2 billion by 2020, as shown in Figure 5.

The Governor's budget for 2012–13 includes three major proposals to address some of the funding challenges currently faced by state parks. Specifically, the budget includes (1) an $11 million reduction in General Fund support that would be achieved largely by closing up to 70 state parks, (2) a $15.3 million continuous appropriation to incentivize efforts to generate additional revenue at state parks, and (3) the alteration of an operating agreement to collect entrance fees. Below, we discuss each of these proposals and some of our concerns.

Close Up to 70 State Parks

The proposed budget assumes that DPR will close up to 70 state parks by July 2012. In selecting which parks to close, the department is utilizing the criteria that the Legislature established last year in statute regarding park closures (see Figure 6). In an attempt to reduce the number of parks to be closed, the department has created agreements with the United States Forest Service (USFS), regional park districts, and nonprofit organizations resulting in ten parks being removed from the closure list. The department also plans to issue a request for proposals from concessionaires to potentially keep additional parks from closing.

Figure 6

State Law Specifies How Department of Parks and

Recreation Selects Parks for Closure

|

Criteria for Evaluating Each Park

|

- Relative statewide significance.

|

|

|

- Net savings from closure.

|

- Physical feasibility of closing.

|

- Potential for partnerships to support the park.

|

- Operational efficiencies to be gained from closing.

|

- Significant and costly infrastructure deficiencies.

|

- Recent infrastructure investments.

|

- Necessary, but unfunded capital investments.

|

- Deed restrictions and grant requirements.

|

- Extent of non–General Fund support.

|

Since DPR announced its plan to close up to 70 parks, the Legislature has raised concerns about the impact of closed parks on visitors and nearby communities, and the ability to realize the savings because of offsetting closure costs and ongoing caretaker and maintenance costs. The department has since concluded that some parks on the closure list are too costly to close—meaning it would cost more to close them in the near term, because of the one–time costs associated with closure. As a result, to achieve savings in the budget year, it may need to swap some parks on the closure list for others or find additional savings elsewhere. Furthermore, since DPR will only minimally maintain closed parks, the cost to reopen these parks in the future will likely be substantial because the infrastructure would not have been sufficiently maintained.

Authorize Continuous Appropriation to Incentivize Districts to Generate Revenues

The Governor's budget requests the authority to continuously appropriate $15.3 million annually in fee revenues to parks. According to the administration, this would incentivize districts to implement new projects that could increase the number of paying visitors. The DPR asserts that the annual budget process for the allocation of park revenues decreases its ability to achieve greater park revenue, because it is delayed in providing funding for the implementation of new projects. Under the Governor's proposal, DPR would have the authority to spend up to $15.3 million of newly generated revenue in the year it is generated, instead of waiting for the Legislature to appropriate the funds the following year.

We are concerned that this proposal limits the Legislature's authority and would not result in the stated goal of incentivizing districts to generate revenue. Specifically, allowing a portion of DPR's funding to be continuously appropriated would limit the Legislature's authority to approve DPR's expenditures. In addition, it is unlikely that this proposal would result in the desired outcomes because the administration's proposed budget trailer legislation does not specify that a district would receive any of the revenue it generates. Instead, it appears that the funds could be distributed to any park for any purpose, which would provide very little incentive for a park to generate additional revenue. For these reasons, we recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor's proposed continuous appropriation of $15.3 million in park revenues.

Allow Collection of Entrance Fees at Montana de Oro State Park

The Governor's budget proposes to revise the operating agreement between DPR and the county of San Luis Obispo by changing the user fees at Montana de Oro State Park from parking fees to per–vehicle entrance fees. Under this proposal, the state would gain control of park access and the ability to charge per–vehicle entrance fees in exchange for the county paying the state less for a golf course concession at the park. The department estimates that the planned fees will result in a net increase of $235,000 in park revenues in 2012–13. We think the general concept of the proposal has merit. This is because it will allow DPR to gain permanent control of the road used to access the Montana de Oro State Park and, as a result, to more effectively collect entrance fees for the park. Thus, we recommend that the Legislature approve the Governor's proposal.

In consideration of the closure of up to 70 state parks and the Legislature's concern about maintaining the state's park system, we discuss below various options to help keep parks open. While there are inherent trade–offs associated with each option, the Legislature will want to consider those that will (1) minimize the impact on visitor experience and access, (2) provide a long–term funding source for the parks, (3) build upon existing and successful programs within the park system, and (4) not restrict legislative oversight or flexibility. Also, because most of these options take time to implement, the Legislature may want to consider a package of options that will, on balance, address the short– and long–term needs of the parks.

In general, the available policy options fall into three general strategies:

- Reducing size of the state park system.

- Changing park operations.

- Increasing park revenues.

Figure 7 lists the various specific options with each of the above general strategies, which we describe in detail below.

Figure 7

Strategies and Options to Address Park Closures

|

|

- Reducing the Size of the State Park System

|

|

|

- Transfer ownership of parks.

|

|

|

- Limit use of sworn staff.

|

- Allow for for–profit operation of state parks.

|

|

|

- Raise additional revenue from fees.

|

- Incentivize revenue generation at the district level.

|

|

|

- Provide a dedicated revenue source.

|

Given the historical and ongoing backlog of deferred maintenance in the state parks, it is possible that the state cannot afford to keep the state park system at its current size. To maintain the highest priority state park assets in a reasonable condition, the state could reduce the size of the park system so that more funding is available to adequately maintain and operate the remaining parks.

Close Some State Parks

One option for reducing the size of the park system is to close a number of state parks. This option would limit public access to recreational activities. In addition, it is uncertain at this time how much funding can actually be saved from closing a given number of state parks. This is because the department is unable to provide information on the cost of operating an individual park. Moreover, there are some costs associated with closing a park, such as the cost of packing up artifacts and shipping them to DPR's central administration office for storage.

Transfer Ownership of Some State Parks

Given that some state parks provide primarily local benefits, another option is to transfer parks or parcels of land to the care of local governments or other non–state entities. Parks that do not have unique natural or historical components of broad state interest but have strong regional support or share borders with regional parks could be transferred to local governments or nonprofit organizations in exchange for a promise to operate the land as a park. In contrast to closing a state park, transferring ownership of a park to a non–state agency releases the state from all financial responsibility and maintains public access to the park. However, given the financial constraints of local governments, it is uncertain if a significant number of cities and counties would be interested in taking ownership of a state park. Thus, the estimated savings from this option could be minimal. We note that a couple of states (mainly Georgia and Texas) have transferred or are in the process of transferring ownership of a few of their state parks to local governments.

One of the largest costs to operate state parks is labor, mainly for paying state staff to operate many aspects of the parks. In order to reduce such costs, the Legislature could consider options that would allow the parks to operate in a more efficient manner. Specifically, changes could be made to modify how state staff are used to operate the parks, as well as allow DPR to contract with for–profit companies to operate state parks. (As discussed earlier in this report, DPR already contracts with local governments for park operations and is authorized to contract with nonprofit organizations.)

Eliminate Need for Peace Officer Status for Certain Tasks

As previously mentioned, park superintendents and rangers are sworn peace officers who are responsible for operating many aspects of state parks. As shown in Figure 8, while some of their day–to–day duties require peace officer status (such as responding to emergencies and making arrests), many of them do not (such as managing staff, providing information to visitors, and leading school groups on park tours).

Figure 8

Current Ranger Duties

|

Peace Officer Related Duties

|

- Patrol parks and campgrounds.

|

|

|

|

|

- Enforce park rules and state laws.

|

|

Non–Peace Officer Related Duties

|

|

|

- Train and manage volunteers and seasonal staff.

|

|

|

|

|

- Provide visitor information.

|

|

|

- Explain exhibits, local ecology, and history.

|

One option to reduce the operating costs of state parks is to have non–peace officers perform the tasks that do not require a peace officer status to complete. Tasks that require peace officer status would still be performed by sworn staff. This would enable DPR to hire fewer sworn staff and more non–sworn staff, who typically require less training and lower compensation. In addition, we note that DPR currently has a vacancy rate of roughly 25 percent for park rangers. According to the department, this is in part due to its difficulty in attracting and retaining peace officers to work for the parks, as other government entities (such as cities) typically pay much higher salaries. Reducing the need to have park rangers who are peace officers would likely make it easier for the department to fill its vacancies. We estimate that the above option could result in savings in the low millions of dollars annually.

Expand Park Operations to Private Sector

Another option that the Legislature could consider is to allow for–profit organizations to operate certain state parks. This option would achieve operational savings—potentially in the low tens of millions of dollars annually—and transfer some of the financial risk of managing a park to another entity. Under such an option, the state would still own the asset and could specify certain conditions that a private company would need to meet.

Our research finds that the USFS, as well as many provinces in Canada, currently use private companies to operate and manage entire public parks and recreation areas. Outcomes for these different arrangements vary, but the reported benefits generally include the flexibility to easily reduce or increase staffing levels and lower operating costs from the introduction of competitive bidding. Lower costs were particularly noticeable if several parks in a geographic area were packaged as a single operation, allowing for economies of scale.

According to the provincial park system of British Columbia (BC Parks), bundling a mix of different parks (low–revenue–generating parks and high–revenue–generating parks) helps to attract potential bidders, since it is unlikely that bidders would otherwise elect to operate low–revenue–generating parks. The BC Parks also makes payments to most of their private operators to cover costs that are not recouped by park visitor fees. Even with these payments, BC Parks considers its operations model a success, because the payments, on balance, are less than the full cost of operating the parks.

Another advantage of using private companies to operate the parks is that they generally can procure new equipment and implement new projects more quickly than the state. In addition, privately operated parks also could assist DPR with its cash flow needs by assuming some of the risks associated with operational costs (including unpredictable user demand and fee revenue). Currently, if revenues from park fees are less than projected, the department must cut its operating costs during the fiscal year to make up for this loss in revenues. If private companies operated some of the parks, they could potentially take on this risk, as well as risks resulting from reduced visitor demand and unexpected maintenance costs.

However, DPR may be limited in its ability to attract private contractors. Specifically, because the infrastructure of the state park system has not been adequately maintained, private operators may require DPR to fund the cost of certain repairs as a condition of the operating contracts. In some cases, the degradation of park infrastructure (such as sewage or water systems) is so severe that if funding these repairs were the only way to attract qualified bidders, additional cost pressures would be placed on DPR in the near term. We also note that DPR would need to retain some staff to manage the contracts and ensure parks are maintained and operated up to DPR's standards.

Another general strategy addressing the current funding challenges faced by state parks is to increase the amount of revenues that is collected to fund their operations and facilities. Specifically, the Legislature could change the type and amount of user fees that are charged, incentivize revenue generation in park districts, expand concession agreements, and establish a new dedicated revenue source for the park system.

Increase Existing User Fees and Establish Additional Fees

As discussed earlier, about 20 percent of park revenues for operations come from fees that people pay when they visit most state parks—either a parking or entrance fee. Currently, the average cost to visit a state park is $3.25, which is only about 70 cents more than the average park fee collected in 1996–97. We also note that most people visit state parks for free, as most do not charge an entrance fee.

Thus, the state could increase revenues from user fees in one of two ways: (1) impose a per visitor charge at more parks by switching from parking fees to entrance fees and (2) increase the amount of the user fees that are currently charged. Moving away from parking fees to entrance fees can help address the challenge of visitors legally avoiding paying parking fees by parking on roads outside of a park and walking into the park for free. We estimate that charging an eighth of the people that currently visit day–use parks for free an entrance fee would increase revenues by the low tens of millions of dollars annually. Alternatively, raising the amount of the fees that current visitors pay by $1 would also increase revenues by the low tens of millions of dollars annually. Moreover, if school groups (which now visit parks and use online learning programs for free) were charged a modest fee, the state could raise about $2 million in revenues annually.

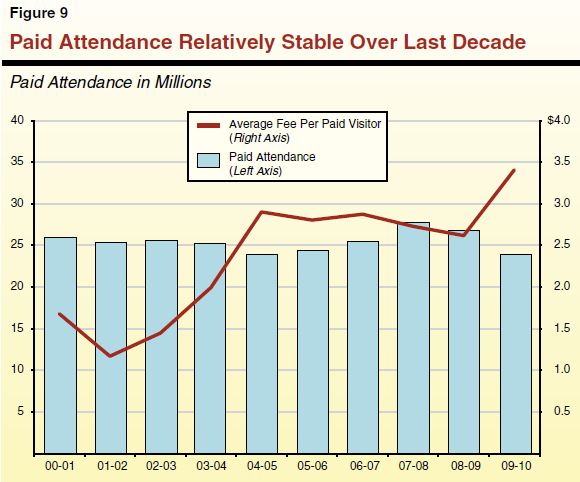

According to DPR, park attendance typically declines after a fee increase is implemented and that, on average, it takes three years for attendance rates to recover. However, attendance data from the department for paid day use and camping over the past decade shows that attendance has remained relatively flat at about 25 million people, despite changes in fee levels during this time period (see Figure 9). In part, this could be due to the finding of many studies that the cost of transportation to parks—not park fees—is the main financial barrier for potential park visitors, especially those with low incomes. The department currently offers many discounts to help mitigate concerns about individuals with lower incomes being able to access the parks. While these discounts could be expanded to address concerns about access, this would offset to some extent additional revenue generated by increases in fees.

Another potential trade–off to consider is that imposing more entrance fees can result in increased administrative and enforcement costs. For example, at some parks, the cost of staff to enforce and collect fees may be more than the revenue brought in by the fees. Also, controlling access and ensuring payment can be difficult at parks that lack a main entrance. To address some of these potential challenges, a concession was approved in 2011 to use a private contractor to collect fees at six state beaches within the San Diego Coast District. Such an approach could be used in other state parks to help mitigate increases in state administrative costs that could result from implementing additional user fees.

In addition, we note that using fees as a primary revenue source can make it somewhat difficult for parks to plan and budget. This is because the amount of revenues anticipated being collected in a given year may not materialize. While attendance has remained relatively flat on an annual basis, the amount collected in user fees from month to month can vary significantly because park attendance largely depends on people's preferences and uncontrollable factors such as the weather.

Incentivize Revenue Generation at District Level

Our analysis indicates that park district staff currently have little incentive to maximize the generation of revenues and reduce operating costs. This is because there is no link between the amount of fees a district collects and the funding it receives from fee revenues. However, if a portion of the fees collected in a district remained in that district for its use, districts would have a greater incentive to maximize revenue in their parks through new or experimental fee collection programs. The DPR could evaluate promising practices and expand the most successful throughout its system. We estimate that implementing such an approach statewide could potentially increase annual park revenues in the low tens of millions of dollars. (As we discuss in the nearby box, a similar incentive program was implemented in Texas on a pilot basis.)

Lessons Learned From Texas' Revenue Generation Program

In 1994, Texas implemented a voluntary program that incentivized cost savings by having each of its state parks set an annual revenue goal and spending target. In order to initially assist parks that joined the program, the state provided them with start–up funds to implement pilot projects geared toward increasing revenue (such as recreation gear rentals and new fee collection methods). If a park exceeded its revenue goal for a given fiscal year, it could keep a share of the excess revenues as part of its budget from the subsequent fiscal year. If a park spent less than its targeted expenditure level in a year, it could carry over a share of its savings to the following year. The state distributed the additional revenues on a proportional basis. For example, a park would receive 35 cents of every dollar that exceeded its revenue target. Forty percent of the revenues was spent to support parks overall, especially those parks that could not feasibly become self–supporting. The remaining 25 percent was allocated to parks that joined the program.

The program led many parks to cut costs and several parks to become self–sustaining. However, when the Texas park system had low visitor turnout due to unanticipated or uncontrollable events (such as unfavorable weather), the state was unable to make some of the incentive payments to those parks participating in the program. In addition, while new projects increased the number of visitors and the amount of revenue at certain state parks, the overall statewide number of visitors and amount of revenue did not increase. The program was abandoned a few years later when it became insolvent.

According to park staff in Texas, although the program ultimately failed, key pieces were beneficial. These included incentivizing park superintendents to try new operations and programs, execute business plans, and perform market analyses to assess the costs and benefits before starting a new project. Texas staff believes that a different allocation of new revenue might have made a difference in the program's success.

The above option does have its limitations, as not all parks have the ability to generate additional revenue. Parks that lack significant recreational features, such as lakes or beaches, may not ever be able to substantially increase attendance and revenues. Similarly, parks with historically significant features may not be able to reduce their operational costs. We also note that if an incentive program is not well–structured to ensure staff complete high–priority tasks, incentivizing cost savings may encourage employees to decrease their level of service and trade necessary maintenance costs for short–term savings.

Expand Use of Concessionaire Agreements

Another option for legislative consideration is to expand the use of concessionaires in state parks, which would increase the amount of revenues that DPR receives from concessionaires. We estimate that such an expansion could potentially increase annual revenues by up to $10 million, depending on how many additional concessionaire agreements are entered into. Ideal candidates for expansion are concessions that are in demand (restaurants and catering), are easier to expand (fee collection services and parking lot management), and can generate the greatest revenue for the state. It is likely that some of these types of concessions could be expanded.

However, an important trade–off to consider is that increasing the number of concessionaire agreements in the state park system alters the role of DPR towards a greater focus on commercial recreational and entertainment services, rather than preserving natural resources. According to DPR, when it evaluates a potential concession, it carefully considers how the concession fits within the department's mission and the landscape of a park. There also would be minor increased administrative costs related to DPR creating, reviewing, and managing additional concession contracts.

Establish New Revenue Sources Dedicated to Parks

The Legislature could also consider establishing a dedicated revenue stream to provide additional funding for state parks. As summarized in Figure 10, many states currently dedicate tax revenues from various sources to fund their state park systems. In addition, some states have variations of a vehicle license–related fee that funds state parks, sometimes allowing drivers to opt–in or opt–out of paying the fee. (California voters defeated Proposition 21 on the November 2010 ballot, which would have enacted a vehicle license surcharge to help support state parks in return for granting fee payers day use at state parks.) Finally, like California, at least seven other states use proceeds from the sale of commemorative license plates and stamps to fund state parks, although these generally bring in substantially less revenue than other dedicated revenue sources.

Figure 10

Many States Use Dedicated Funding Mechanisms For State Parks

|

Dedicated

Revenue Source

|

Revenue

Generated Annually

|

States

|

|

Sales tax

|

Tens of millions of dollars

|

Minnesota, Arkansas, Texas (sale of sporting goods only)

|

|

Oil and gas/drilling tax

|

Tens of millions of dollars

|

Alabama, Arkansas, Michigan, Alaska, Pennsylvania

|

|

Real estate transfer tax

|

$5 to $20 million

|

New York, Tennessee, Delaware, North Carolina

|

|

Vehicle license fee (opt–in or opt–out)

|

Tens of millions of dollars

|

Montana, Washington

|

|

Income tax donation check–off

|

Less than $10 million

|

Arkansas, Kansas, South Carolina, Colorado, Delaware

|

|

Specialty license plates and/or stamps

|

Less than $10 million

|

Montana, Nebraska, Ohio, Texas, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, California, Maine

|

Although establishing a dedicated tax for parks—such as a portion of state sales tax revenue—would reduce DPR's reliance on General Fund support, it also reduces the Legislature's ability to prioritize how the state spends the revenues it receives. Dedicating tax revenue for a specific purpose instead of depositing them into the state's General Fund limits the overall amount of funds that the Legislature can allocate across all state programs based on its priorities.

Dedicated fees or donations (such as specialty license plates or an opt–in donation on vehicle registration or income tax forms) are less problematic because they are voluntary. However, these fees often raise less revenue.

In light of the planned park closures, we attempted to find a balance between the need to achieve budgetary savings or increase park revenues and the goal of preserving public access to the parks. While we recognize that some parks may need to be closed in the short run, we recommend a number of proposals that we believe would reduce the magnitude of the number of parks proposed for closure in long run. Specifically, we propose the following:

- Transferring Ownership of Some State Parks to Local Governments. We recommend that the Legislature direct DPR to assess which state parks in its system could be transferred to local governments.

- Eliminating the Use of Peace Officers for Certain Park Tasks. We recommend that the Legislature direct DPR to report at budget subcommittee hearings this spring on ways that it could separate peace officer and other duties into existing sworn and non–sworn job classifications.

- Allowing Private Companies to Operate Some State Parks. We recommend that the Legislature adopt budget trailer legislation specifying that for–profit organizationscan operate state parks—either as concessionaires or through operating agreements. We further recommend supplemental report language requiring DPR to analyze which parks might be suitable for private operators and for each of these parks identify operational costs, fee revenue, and special issues that may need consideration (such as historical structures or significant deferred maintenance).

- Increasing Park User Fees and Shifting Towards Entrance Fees. We recommend that the Legislature adopt supplemental report language directing DPR to complete a study of the feasibility of adopting entrance fees at its parks and an analysis to deter–mine the amount of park fees that could be raised without substantially impacting park attendance. (The DPR currently has the authority to increase and establish both parking and entrance fees.) The department could also report on the impact of charging modest fees to school groups.

- Incentivize Park Districts to More Effectively Collect Fees. We recommend the Legislature adopt supplemental report language directing DPR to study how to structure an incentive program that would allocate some of the fee revenue collected back to districts.

- Expanding Use of Concessions. We recommend that the Legislature direct DPR to continue its efforts to expand the use of concessionaires.

While we think the above recommendations would help reduce the need to close the magnitude of parks being contemplated by DPR—particularly in the long run—it is certainly not the only set of options available to the Legislature. The Legislature could certainly remove, replace, or modify any of these components to reflect its own choices about the trade–offs between achieving savings or increasing revenues and preserving public access to the parks, as well as consideration of other criteria.