|

The California High–Speed Rail Authority (HSRA) is responsible for planning and constructing an intercity high–speed train that would link the state's major population centers. In April 2012, the HSRA released its most recent business plan that estimates the cost of constructing the first phase of the high–speed train project at $68 billion. However, the HSRA only has secured about $9 billion in voter approved bond funds and $3.5 billion in federal funds. Thus, the availability of future funding to construct the system is highly uncertain. The revised business plan also makes significant changes from prior plans—such as proposing to integrate high–speed rail with other passenger rail systems, constructing the southern portion of the system first, assuming lower construction costs, and using "cap–and–trade" auction revenues if additional federal funds fail to materialize. The Governor's budget plan for 2012–13 requests $5.9 billion—$2.6 billion in state bond funds matched with $3.3 billion in federal funds to begin construction of the high–speed rail line in the Central Valley. In addition, about $800 million is requested to make improvements to existing passenger rail services and about $250 million to complete preliminary design work and environmental reviews for various sections of the project.

We find that HSRA has not provided sufficient detail and justification to the Legislature regarding its plan to build a high–speed train system. Specifically, funding for the project remains highly speculative and important details have not been sorted out. We recommend the Legislature not approve the Governor's various budget proposals to provide additional funding for the project. However, we recommend that some minimal funding be provided to continue planning efforts that are currently underway. Alternatively, we recognize that the Legislature may choose to go forward with the project at this time. If so, we recommend the Legislature take a series of steps to increase the chance of the project being successfully completed.

|

The HSRA is responsible for planning and constructing an intercity high–speed train that is fully integrated with the state's existing mass transportation network. The 800–mile long high–speed train system would link the state's major population centers. The California High–Speed Rail Act of 1996 (Chapter 796, Statutes of 1996 [SB 1420, Kopp]), established HSRA as an independent authority consisting of a nine–member board appointed by the Legislature and Governor. In addition, the HSRA has a staff of approximately 30 state employees who oversee contracts for environmental review, preliminary engineering design, preliminary right–of–way acquisition tasks, and other activities such as legal counsel, communications, and contractor oversight.

In November 2008, voters approved Proposition 1A, which allows the state to sell up to $9.95 billion in general obligation bonds to partially fund the development and construction of the high–speed rail system. Of that amount, $9 billion is for the high–speed rail system while the remaining $950 million is for existing passenger rail systems to improve their connectivity with the high–speed system. Proposition 1A further enacted certain statutory requirements to guide the design of the system and to help assure the voters that there would be accountability and oversight of the HSRA's use of bond funds.

In addition to the funds authorized in Proposition 1A, HSRA has been awarded approximately $3.5 billion in federal funds for planning, engineering, and constructing up to 130 miles of dedicated and fully grade–separated high–speed rail line in the Central Valley. Specifically, these funds were provided through the federal High–Speed Intercity Passenger Rail Program, which is administered by the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA). This program was established by the 2008 Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act to award grants for eligible intercity high–speed rail passenger rail projects that contribute to building new or substantially improving existing passenger rail corridors. Initial funding for this program was made available in the 2009 federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. The federal budget for federal fiscal year 2009–10 appropriated additional funding to FRA for high–speed rail grantees. However, as we discuss in more detail below, permanent and ongoing federal funding for this program has not been identified at this time.

Chapter 618, Statutes of 2009 (SB 783, Ashburn), requires HSRA to submit a business plan containing specified elements to the Legislature by January 2012 and every two years thereafter. On April 2, 2012, the HSRA released a revised draft business plan. This is the fourth draft plan that the authority has released for review and comment. As shown in Figure 1, the HSRA proposes to construct the entire 800–mile long statewide high–speed train system in two phases—Phase 1 "Blended" and Phase 2. Phase 1 Blended, which consists of different stages, attempts to integrate or blend high–speed rail operations with other passenger rail systems. (Please see the nearby box for a more detailed description of this blended approach being proposed by the HSRA.) The total cost for Phase 1 Blended (connecting the San Francisco Bay Area to the Los Angeles Basin) is estimated to be $68.4 billion, which is significantly less than the $98.5 billion cost estimated by the HSRA in its November 2011 draft business plan. Currently, the total cost for Phase 2, which would further expand the system to other regions, is unknown.

Proposed Blended Approach for High–Speed Rail

In general, the blended approach proposed by the California High–Speed Rail Authority involves the integration of high–speed rail operations with other passenger rail systems, in order to control costs, accelerate benefits, and address environmental concerns. Such an approach could include coordinated scheduling and ticketing. For example, on the San Jose to San Francisco corridor, the Phase 1 Blended system would share upgraded and electrified track with Caltrain. The Phase 1 Blended system may also rely on "enhanced" Metrolink (Southern California's passenger rail system) service in the Los Angeles to Anaheim corridor. In addition, the "Northern Unified Operating Service" would integrate the services (such as ticketing, trackage rights, and marketing) of a consortia of existing Northern California passenger rail operators. These include the state–supported Amtrak routes and the Altamont Commuter Express.

Figure 1

High–Speed Rail Construction

|

Phase/Stage

|

Description

|

Length in

Milesa

|

Completion

Year

|

Cost in

Billionsb

|

|

Phase 1 Blended

|

|

|

|

|

|

Initial Operating Segment (IOS), first construction

|

Madera to Bakersfield

|

130

|

2017

|

$6.0

|

|

Remainder of IOS

|

Merced to San Fernando Valley

|

170

|

2021

|

25.3

|

|

Bay to Basin

|

San Jose to San Fernando Valley

|

110

|

2026

|

19.9

|

|

Blended

|

San Francisco to Los Angeles

|

110

|

2028

|

17.2

|

|

Subtotals

|

|

520

|

|

$68.4

|

|

Phase 2

|

Extend to other regionsc

|

280

|

Unknown

|

Unknown

|

|

Total

|

|

800

|

|

|

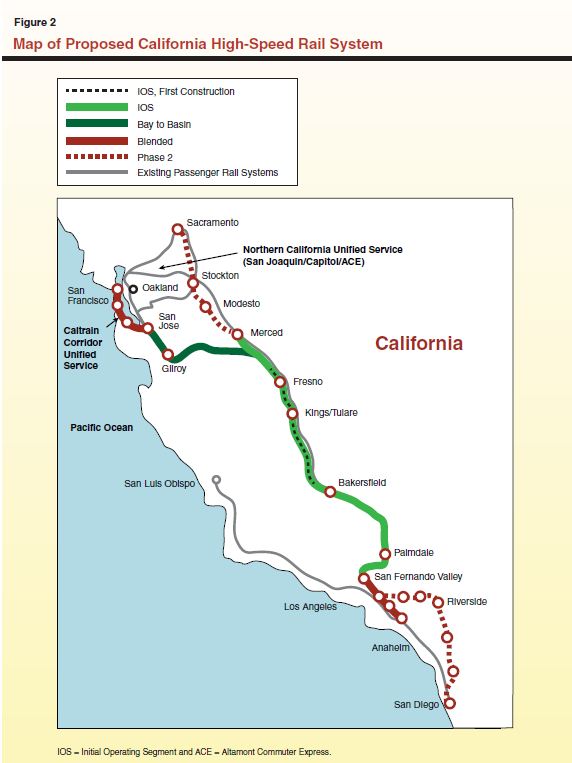

Train Would Go South First. The HSRA's previous business plan indicated that construction for the high–speed rail system would begin in the Central Valley. However, that plan did not indicate whether the train would subsequently be constructed towards Northern or Southern California. The latest business plan proposes to construct the southern portion of the system first. As shown in Figure 1, the first two stages of construction would be an Initial Operating Segment (IOS) that would run between Merced and the San Fernando Valley over the Tehachapi Mountains. The HSRA asserts that this corridor could support the operation of an unsubsidized passenger train service consistent with the design characteristics required by Proposition 1A. The authority estimates that the IOS would cost a total of about $31.3 billion to construct and be completed by 2021. The next construction stage of Phase 1 Blended (referred to as the "Bay to Basin") would extend the IOS to San Jose. The final stage of Phase 1 Blended would extend the system to the Transbay Terminal in San Francisco and to Union Station in Los Angeles (or to Anaheim). Figure 2 illustrates the location of the various phases and stages of construction.

Investments in "Bookends" of System. The 2012 revised business plan proposes to direct $1.1 billion in Proposition 1A funds to make investments in regional rail projects in the San Francisco Bay and the Los Angeles metropolitan areas—referred to as the bookends of the high–speed rail system. The HSRA has signed memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with regional transit agencies in these areas to coordinate efforts to obtain additional funding for projects that can immediately improve passenger rail service in those regions. Although the specific projects to be constructed under the terms of these agreements have not been fully identified, plans include electrifying the Caltrain corridor. Projects in Southern California will be smaller improvements around the region that improve safety or increase capacity and could include, for example, grade separations or double–tracking along the high–speed rail corridor.

Lower Estimated Construction Costs. The 2012 revised business plan includes detailed "low" and "high" cost estimates for Phase 1 Blended that range from $68.4 billion to $79.8 billion. These estimates are lower than those provided by the HSRA in the November 2011 business plan, which ranged from $98.5 billion to $117.6 billion, particularly in the latter stages of construction. Specifically, reductions in the out–year costs result from the use of blended operations, abandoning plans to build out to Anaheim (which is now under reconsideration), and revised assumptions on future interest rates. The estimated costs to construct the first stage of the project are relatively unchanged from the estimate identified in the November 2011 business plan.

Less Capacity and Reduced Ridership. According to HSRA, in addition to reducing costs, the changes identified in the revised 2012 business plan would result in a system with less capacity and reduced ridership. Specifically, the HSRA estimates that the projected ridership would be about 30 percent lower than estimated in the November 2011 draft business plan. For example, while the November 2011 business plan projected between 29.6 million and 43.9 million one–way trips per year on Phase 1 in 2040, the latest plan assumes between 20.1 million and 32.6 million one–way trips per year.

Assumes Operating Subsidy Would Not Be Needed. The business plan continues to assume, as required by Proposition 1A, that the high–speed rail system will not need an operating subsidy. This is because most of the operations and maintenance costs are variable based on the number of trains and miles of track. Given the estimated lower ridership, the business plan assumes that fewer trains will be needed. Specifically, the HSRA estimates that revenues will exceed the cost to operate the train if there are more than 6 million fare–paying passengers per year. We note that to better ensure the soundness of its operating cost estimates, the HSRA is in the process of joining the Union Internationale des Chemins de fer (UIC) or the International Union of Railways. For example, the HSRA has requested UIC to conduct a study of high–speed train operating and maintenance costs, in order to improve its own planning efforts.

Use of Cap–and–Trade Revenues as Backstop. The revised business plan is similar to the last business plan in that it heavily relies on federal funding to complete construction of the system. As shown in Figure 3, nearly $42 billion, or over 61 percent of the funds needed to construct Phase 1 Blended, is anticipated to come in the form of grants from the federal government. The most significant change from prior business plans is that if the federal funds fail to materialize, revenue from the state's quarterly cap–and–trade auctions would be used as a "backstop." As we discuss in the nearby box, the cap–and–trade auctions are part of the state's overall plan to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The remaining funds to complete the project consist of $8.2 billion in Proposition 1A funds, $13.1 billion in private capital, and $5.2 billion from other funds (such as local funds and operating surpluses).

Figure 3

Sources of Funding for Phase 1 Blended

(Dollars in Billions)

|

Source of Funds

|

Amount

|

Percent of

Total

|

|

Proposition 1A bonds

|

$8.2

|

12.0%

|

|

Secured federal grants

|

3.3

|

4.8

|

|

Unsecured federal grants and/or cap–and–trade auction revenue

|

38.6

|

56.4

|

|

Private capital

|

13.1

|

19.2

|

|

Other funds (local funds, operations, development)

|

5.2

|

7.6

|

|

Totals

|

$68.4

|

100.0%

|

Cap–and–Trade Auctions

The Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 (Chapter 488, Statutes of 2006 [AB 32, Núñez/Pavley]), commonly referred to as AB 32, established the goal of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions statewide to 1990 levels by 2020. In order to help achieve this goal, the California Air Resources Board (ARB) recently adopted regulations to establish a new cap–and–trade program that places a "cap" on aggregate GHG emissions from entities responsible for roughly 80 percent of the state's GHG emissions. The ARB will issue carbon allowances that these entities will, in turn, be able to "trade" (buy and sell) in the open market.

As part of its plan to issue allowances, ARB will hold quarterly auctions at which time a portion of these allowances will be made available for purchase. For 2012–13, ARB's auctions are estimated to generate roughly $660 million to upwards of $3 billion. These revenues are expected to be in the tens of billions of dollars in the aggregate over subsequent years. |

Consistent with the HSRA's revised business plan, the Governor's budget plan for 2012–13 requests additional funding to continue the high–speed rail project. Specifically, the Governor requests in an April Finance Letter:

- $5.9 billion ($2.6 billion in Proposition 1A funds matched with $3.3 billion in federal funds) to acquire right–of–way ($937 million) and for construction (about $5 billion) of the 130–mile Central Valley segment from Madera to just north of Bakersfield. As shown in Figure 4, of the $5 billion for construction, $4.2 billion would be for five separate contracts. The remaining $800 million would be for design, contingencies, and other construction–related expenditures.

- $812 million in Proposition 1A funds for rail connectivity projects, including $106 million for Caltrans intercity rail (Amtrak) and $706 million for local rail systems. (This amount reflects the remainder of the $950 million that was set aside in Proposition 1A for rail connectivity.)

- $252.5 million ($204.2 million in Proposition 1A funds and $48.3 million in federal funds) to complete preliminary engineering design work and environmental review for various sections of the project.

Figure 4

Central Valley Segment Divided Into Five Design–Build Contracts

|

Contract

|

Description

|

Length in Milesa

|

Cost Estimate

(In Billions)

|

Estimated Date of

Contract Award

|

|

1

|

North of Fresno through Fresno

|

26 to 37

|

$1.5

|

December 2012

|

|

2

|

South Fresno to Hanford Aroma Road

|

28

|

0.8

|

September 2013

|

|

3

|

Hanford Aroma Road to Dresser Avenue

|

55

|

1.0

|

September 2013

|

|

4

|

Dresser Avenue to Allen Road

|

14

|

0.4

|

October 2013

|

|

5

|

Trackwork for the entire 130 mile segment

|

N/A

|

0.5

|

March 2017

|

In addition, the Governor's January budget proposal includes $17.9 million for state operations to fund the authority for 73 positions (including 19 new positions), contracts with other state departments, and external contracts for communications, program management, and financial consulting services.

Based on our review of the 2012 business plan and the Governor's related budget proposals, we find that the HSRA has not provided sufficient detail and justification to the Legislature regarding its plan to build a high–speed rail system. Specifically, we find that (1) most of the funding for the project remains highly speculative, including the possible use of cap–and–trade revenues; and (2) important details regarding the very recent, significant changes in the scope and delivery of the project have not been sorted out.

Most of the Future Funding Remains Speculative

Future Funds Not Identified. The future sources of funding to complete Phase 1 Blended are highly speculative. Specifically, the funding approach outlined in the 2012 revised business plan is no more certain than what was proposed in previous plans. For example, the recent plan assumes nearly $42 billion, or 62 percent of the total expected cost, will be funded by the federal government. However, about $39 billion of this amount has not been secured from the federal government. Given the federal government's current financial situation and the current focus in Washington on reducing federal spending, it is uncertain if any further funding for the high–speed rail program will become available. In other words, it remains uncertain at this time whether or not the state will receive the necessary funds to complete the project. The absence of an identified funding source at the federal level makes the state's receipt of additional funding unlikely, particularly in the near term. In addition, it is unclear how much, if any, other non–state funds (such as local funds, and funds from operations and development, or private capital) have been secured. In total, only $11.5 billion (or about 17 percent) of the estimated funds needed to complete the project have been committed.

Use of Cap–and–Trade Auction Revenues Very Speculative. As discussed earlier, the plan proposes to use revenue from the state's quarterly cap–and–trade auctions, which are scheduled to begin in November of this year, to backstop any shortfall in anticipated funding from the federal government. These auctions involve the selling of carbon allowances as a way to regulate and limit the state's GHG emissions in accordance with Chapter 488, Statutes of 2006 (AB 32, Núñez/Pavley). As we discussed in our recent brief,

The 2012–13 Budget: Cap–and–Trade Auction Revenues, the use of cap–and–trade revenues are subject to legal constraints. Based on an opinion we received from Legislative Counsel, the revenues generated from the cap–and–trade auctions would constitute "mitigation fee" revenues. Therefore, in order for their use to be valid as mitigation fees, these revenues must be used to mitigate GHG emissions. Given these considerations, the administration's proposal to possibly use cap–and–trade auction revenues for the construction of high–speed rail raises three primary concerns.

- Would Not Help Achieve AB 32's Primary Goal. The primary goal of AB 32 is to reduce California's GHG emissions statewide to 1990 levels by 2020. Under the revised draft business plan, the IOS would not be completed until 2021 and Phase 1 Blended would not be completed until 2028. Thus, while the high–speed rail project could eventually help reduce GHG emissions somewhat in the very long run, given the project's timeline, it would not help achieve AB 32's primary goal of reducing GHG emissions by 2020. As a result, there could be serious legal concerns regarding this potential use of cap–and–trade revenues. It would be important for the Legislature to seek the advice of Legislative Counsel and consider any potential legal risks.

- High–Speed Rail Would Initially Increase GHG Emissions for Many Years. As mentioned above, in order to be a valid use of cap–and–trade revenues, programs will need to reduce GHG emissions. While the HSRA has not conducted an analysis to determine the impact that the high–speed rail system will have on GHG emissions in the state, an independent study found that—if the high–speed rail system met its ridership targets and renewable electricity commitments—construction and operation of the system would emit more GHG emissions than it would reduce for approximately the first 30 years. While high–speed rail could reduce GHG emissions in the very long run, given the previously mentioned legal constraints, the fact that it would initially be a net emitter of GHG emissions could raise legal risks.

- Other GHG Reduction Strategies Likely to Be More Cost Effective. As we discussed in our recent brief on cap–and–trade, in allocating auction revenues we recommend that the Legislature prioritize GHG mitigation programs that have the greatest potential return on investment in terms of emission reductions per dollar invested. Considering the cost of a high–speed rail system relative to other GHG reduction strategies (such as green building codes and energy efficiency standards), a thorough cost–benefit analysis of all possible strategies is likely to reveal that the state has a number of other more cost–effective options. In other words, rather than allocate billions of dollars in cap–and–trade auctions revenues for the construction of a new transportation system that would not reduce GHG emissions for many years, the state could make targeted investments in programs that are actually designed to reduce GHG emissions and would do so at a much faster rate and at a significantly lower cost.

Significant Changes Made Recently Without Necessary Details

As described earlier, the most recent business plan makes significant changes to how the construction of the high–speed rail project would proceed, by making early investments in the bookends and constructing the southern portion of the high–speed rail line first. In the past, we have recommended that the Legislature work to ensure that any funding provided be spent on segments that have the greatest potential of actually being constructed and operated and can provide benefit to the state's overall transportation system, even if the rest of the system were not completed.

Based on our review of the 2012 revised business plan, the approach of improving passenger rail infrastructure in the San Francisco Bay and the Los Angeles Metropolitan areas has the potential to deliver some such tangible benefits. In addition, the intent to integrate the high–speed train with the overall transportation network sooner than later also has merit. For example, the "Northern Unified Operating Service" could increase ridership on the existing rail system, which could in turn increase the likelihood that the high–speed train would achieve the ridership targets estimated by the HSRA. Collaboration among passenger rail operators throughout the state is also likely to reduce risk and improve the chance of successfully completing the high–speed rail system.

However, despite the potential benefits, we are concerned that the decisions to make the above changes have been rushed with many important details not having been sorted out. While the HSRA has been planning for the project over the past 15 years, the proposed modifications, which substantially change how the project would proceed, were developed within the last couple of months (and in only the last few days with regards to the inclusion of Anaheim). As a result, it is unclear how some of the changes would be implemented, further adding to the risk of the project. For example, some of the necessary agreements with all parties involved, such as the MOU for the Northern Unified Operating Service, have not yet been reached. In addition, implementation of the project as proposed in the revised 2012 business plan places a greater emphasis on coordination with entities such as the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), the California Transportation Commission, Amtrak, Union Pacific Railroad, and regional rail systems (such as Caltrain and Metrolink). This would require coordination and leadership from HSRA, which has been lacking in the past in part due to the high number of persistent vacancies in key positions (such as the chief executive operator [CEO] and the risk manager).

In view of the above concerns regarding the certainty of future funding and the recent significant changes proposed for the project, we find that the HSRA has not made a strong enough case for going forward with the project at this time. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature not approve the Governor's various budget proposals to provide additional funding for the high–speed rail project. However, we recommend that some minimal funding be provided to continue some of the planning efforts that are currently underway, in order to help the Legislature maintain its future options for the project. Specifically, some of the environmental review and preliminary engineering efforts are nearing completion and it would be costly and time–consuming to start this process over again as opposed to revising and updating environmental documents in the future. In addition, once the necessary environmental documents have been completed, the Legislature may want to consider preserving critical right of way (such as land in densely populated urban areas) through the purchase of easements or acquisitions. In this way, the Legislature could retain some of the investment already made in the project and maintain its options to proceed in the future.

Alternatively, we recognize that the Legislature may choose to move forward with the high–speed rail project at this time. Given the numerous threats to the project's successful completion, we would recommend that the Legislature take a series of steps to increase the chance that the project is successfully completed. First, we would suggest providing funding at this time for only those contracts that will be awarded in 2012–13. As discussed earlier, the $5.9 billion for the first construction project will be procured under five separate contracts. The first contract is estimated to be between $1.5 billion and $2 billion and is expected to be awarded in December 2012. However, the remaining four contracts would be awarded after 2012–13 and, thus, funding for these particular contracts is unnecessary at this time.

We also believe it would be important to improve the governance of the project. In our May 2011 report,

High–Speed Rail Is at a Critical Juncture, we discussed options to better integrate the high–speed rail project into the state's current transportation planning structure. Over the past year, HSRA has been increasingly relying on Caltrans staff and the new business plan indicates an increasing overlap with the roles and responsibility of Caltrans. At the present time, HSRA is advertising for numerous two–year assignments for current Caltrans staff to come over and fill its vacancies. Therefore, should the Legislature decide to move forward with the project at this time, we would recommend adopting legislation that would shift the responsibility for the development of the project from HSRA to Caltrans.

Current staffing levels remain far below authorized positions (about 30 of 54 already authorized positions are filled), with many key positions unfilled. In addition, there continue to be serious concerns about interagency coordination, contractor management, and project funding. Thus, we would further recommend that the Legislature adopt budget bill language requiring the new CEO to present a plan that specifies (1) a strategy and timeline for filling vacancies; (2) how HSRA will ensure coordination with other state, regional, and private transportation entities; (3) steps that will be taken to ensure adequate contactor management and oversight; and (4) how new sources of project funding will be developed.

Finally, it will be important for the HSRA to provide certain critical information and key documents. While it is not unreasonable that certain details of the business plan would be periodically revised with changes in circumstances and new information, there are critical parts of the recent plan that lack sufficient detail or have not yet been fully developed. Thus, in order to allow for greater legislative oversight of the project, we would also recommend that the Legislature require HSRA to provide the following to the appropriate fiscal and policy committees: (1) a copy of the UIC study examining how HSRA's estimated operating costs compare to international systems, (2) the MOU with the Northern Unified Operating Service, and (3) an analysis of the net impact that high–speed rail would have on the state's GHG emissions.