Analysis of the 2008-09 Budget Bill: Perspectives and Issues, LAO Alternative Budget Plan

What Role Could Parole Realignment Play in Improving Public Safety and Addressing the State’s Budget Difficulties?

A major component in the LAO’s alternative budget package is a nearly $500 million realignment of responsibility for supervision of lower–level criminal offenders released from state prison.

Currently, when a state prison inmate completes his or her sentence, state staff in the community supervise the offender’s parole. The supervision services the state provides parolees are very similar to the services county probation departments provide probationers.

Under our alternative, responsibility for supervising lower–level parolees would shift from the state to counties. Our plan is designed to give counties greater stake in the success of these offenders in the community, thereby reducing their likelihood of reoffending.

Under our alternative, counties would receive slightly more resources than the state currently dedicates to this purpose ($495 million instead of $483 million). Counties would have broad authority to use these resources to reduce recidivism and improve public safety.

Funding for parole realignment would come from a reallocation of: waste and water enterprise special district property taxes, city Proposition 172 sales taxes, and vehicle license fees retained by the Department of Motor Vehicles for administrative purposes.

In a state as large and dynamic as California, it is important for the Legislature to periodically review state–local program responsibilities to clarify duties and make sure that programs are assigned to the level of government likely to achieve the best program outcomes. Over the years, the Legislature has achieved notable policy improvements by realigning responsibility for some state programs to local government and by shifting local programs to the state.

Which programs should the state control and which should local government control? While there is no single answer to this question, Figure 1 summarizes the major factors for the Legislature to weigh as it reviews the assignment of program responsibilities. In general, we find that programs are most effectively controlled and funded by local government if (1) they are closely related to other local government programs, and (2) program innovation and experimentation is desired. Programs are more appropriately assigned to state government, in contrast, if statewide uniformity is important or if the primary purpose of the program is income redistribution.

|

|

|

Figure 1

Assigning Program Responsibilities

Between the State and Local Governments |

|

|

|

♦ Programs

where statewide uniformity is important, where statewide

benefits are the overriding concern, or where the primary

purpose of the program is income redistribution—usually are more

effectively controlled and funded by the state. |

|

� Reduces

inappropriate service level variation. |

|

� Focuses

state attention on programs integral to state goals. |

|

� Allows

income support programs to reflect the resources of the

state—not a single county. |

|

♦ Programs

where innovation, responsiveness to community interests, and

efficiency are paramount—usually are more effectively controlled

by local governments. |

|

� Facilitates

citizen access to the decision-making process and encourages

experimentation. |

|

� Allows

community standards and priorities to influence allocation of

scarce resources. |

|

♦ Coordination

of closely linked programs is facilitated when all programs are

controlled and funded by one level of government, usually local

government. |

|

� Increases

attention to programmatic outcomes. |

|

� Reduces

incentives for cost shifting among programs. |

|

♦ If state and

local governments share a program�s costs, the state�s share

should reflect its level of program control. If the costs of

closely linked programs are shared, the cost-sharing

arrangements should be similar across programs. |

|

� Increases

accountability to the public. |

|

� Promotes

efficiency in expenditures and discourages inappropriate cost

shifting. |

|

|

In this section of the Perspective and Issues, we review the state’s parole program for lower–level offenders. Because exploration of new approaches to reducing recidivism is important, and because state parole and county probation programs are so similar, we recommend the Legislature realign responsibility for supervising lower–level parolees from state government to county probation departments. Our proposed approach is designed to give counties a greater stake in the success of these offenders in the community, thereby reducing the likelihood of their reoffending.

In our view, realigning parole responsibilities makes policy sense regardless of the state’s fiscal condition. If the state’s fiscal condition were stronger, the Legislature could implement parole realignment simply by providing counties the resources the state would have spent on parole. In light of the state’s fiscal challenges, however, we reviewed various existing revenues to determine whether any would be appropriate to redirect to this purpose, thereby also creating a budgetary solution. To provide counties resources to carry out this responsibility and provide financial incentives to counties that operate programs that successfully reintegrate offenders into society, we recommend the Legislature modify three revenue allocation formulas. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature provide counties $495 million from: waste and water enterprise special district property taxes ($188 million), city Proposition 172 sales taxes ($178 million), and vehicle license fees (VLF) currently retained for administrative purposes by the Department of Motor Vehicles ($130 million).

The discussion below is divided into three parts. In the first part, we discuss the similarities between parole and probation, and explain why increasing counties’ role with regards to parole supervision makes sense. We then outline a plan for realigning lower–level parolees. In the second part, we discuss the financial components of our alternative. Part three concludes with a discussion of some important questions regarding parole realignment, including the state’s ability to achieve savings in 2008–09.

Criminal courts can sentence offenders to state prison for a felony offense. After completing their prison term, inmates are released to their most recent county of legal residence where they are placed under parole supervision. State parole agents are responsible for supervising parolees in part by maintaining a certain level of contact with the parolee. The frequency of contact depends on the risk level of the parolee. Parole agents refer parolees to various programs and services—such as substance abuse treatment, employment assistance, and mental health services—to assist the offenders in making a successful transition to parole and to reduce the likelihood that they will reoffend. Some of these programs and services are operated by the state, and others are contracted for with other governmental or community organizations. Parolees must comply with their conditions of parole that include, for example, obeying all laws and submitting to drug testing. Failure to abide by these parole conditions can result in sanctions, including administrative return to prison by the Board of Parole Hearings for up to one year. Parolees can also be prosecuted in criminal courts for new crimes. As of December 31, 2007, there were about 127,000 state parolees.

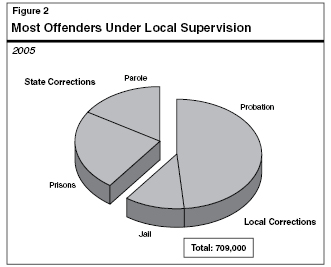

Criminal courts place some offenders on county probation, instead of sending them to state prison. Like parole, probation involves supervision (by a county probation officer, in this case) of the offender in the local community, requirements to comply with specified conditions, referrals to programs and services, and sanctions—including reincarceration—for those offenders who violate those conditions. According to the Department of Justice, there were about 344,000 offenders on probation throughout the state in 2005. About three–quarters of those probationers were offenders convicted of a felony offense. Figure 2 shows the population of offenders on probation and parole, as well as in local jails and state prisons.

In past years, our office has proposed state parole for realignment for several reasons. In particular, realignment could result in better public safety outcomes because the realignment of resources and responsibilities provides an incentive for local governments to have a greater stake in the outcomes of these offenders, develop innovative approaches to supervision, and reduce crime. Moreover, realignment would enable local governments to better meet their public safety priorities, as well as reduce the current duplication of effort that occurs by the state and counties supervising similar offenders in the community. We discuss the case for parole realignment in more detail below.

Better Outcomes and Innovation With Local Control. Parole realignment would change fiscal incentives in such a way as to likely improve public safety outcomes. Specifically, counties would have a greater incentive than they have now to intervene and treat these criminal offenders because they would be responsible for the costs of reincarcerating offenders who commit violations of their probation conditions. Currently, the state bears the cost of reincarcerating parolees who fail under community supervision. Our analysis indicates that giving counties a direct stake in the success of offenders living in their communities is likely to improve offender outcomes and reduce their risk of reoffending. In other words, this strategy is likely to reduce crime.

In part, the incentive for counties to intervene with these offenders will lead them to have greater access to community programs—such as mental health and drug treatment—than sometimes occurs now. For example, counties could use available Proposition 63 funds for these offenders. Proposition 63 provides funding for county mental health programs but excludes parolees from receiving services provided by these funds. However, probationers are eligible for Proposition 63 services.

Moreover, parole realignment would encourage small–scale experimentation and piloting of projects at the local level. Because local governments would be responsible for a number of different programs and offenders, they would be likely to try different models for intervention and treatment of offenders. As a result, innovative approaches to supervising offenders are more likely to be developed by local governments, and these innovations could spread throughout the state.

Better Meet Local Criminal Justice Priorities. In California, as in most states, local governments have the responsibility for most criminal justice activities, including the arrest, prosecution, legal defense, and supervision of criminal offenders. Historically, local governments have had this responsibility because it allows them to respond to activity specific to their communities and set their own priorities for public safety programs and expenditures. Realigning parole is consistent with this general approach by making the supervision of parolees a local public safety responsibility.

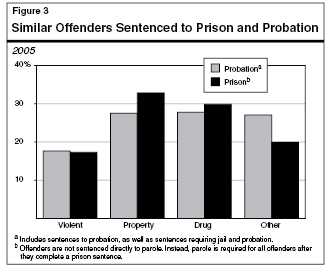

Duplication of Effort by State and Local Governments. As described above, local probation departments and the state’s parole agency fulfill very similar functions. In particular, they supervise criminal offenders living in the community, monitor their compliance with state laws and other conditions of their supervision, as well as provide programs and services designed to reduce recidivism. Moreover, while judges generally have significant discretion to send felons to state or local corrections, parole agents and probation officers supervise very similar offender populations in many respects. As shown in Figure 3, for example, an almost identical percentage of offenders sentenced to probation and prison were convicted for a violent offense. (In many cases, the offenders sentenced to prison are those who have committed more serious violent offenses.)

These similarities in functions as well as populations served means that there exists significant duplication of effort between the state and local governments. Therefore, realigning responsibility for supervising parolees to local probation departments could achieve better economies of scale and reduce overall criminal justice costs.

We recommend realigning some responsibility for supervising parolees to local governments. Under our proposal, certain lower–level inmates released from prison would be supervised by local probation departments rather than the state parole agency. We discuss our proposal in more detail below.

How Would Realignment Work? Under our proposal, local governments would have responsibility for supervising lower–level offenders released from prison on probation. This would include the full responsibility for supervision of these offenders in the community, provision of programs and services, and applying punishments for violations of probation conditions, such as reincarceration in county jails. Returns to prison would only occur for a new criminal court conviction, as can occur currently (though we do propose that counties be able to use some of their revenues to reimburse the state for use of state prison beds if they are experiencing significant jail overcrowding). As discussed below, counties would receive an additional $495 million for local probation programs provided from a shift of existing revenues. This funding would be for the probation–related services described above. The state would retain responsibility for supervising higher–level offenders, such as those convicted of violent crimes, first degree burglary, and drug manufacturing and sales. In the past, our office has proposed realigning all of parole to local probation. While such a proposal still has merit, in our view, we propose focusing on lower–level offenders as a first step.

Who Do We Mean by Lower–Level? We do not propose to shift all parolees to local governments. Instead, we propose to shift a total of 71,000 lower–level parolees, about 56 percent of the total parole caseload. These lower–level parolees are the ones who are most likely to resemble the relatively lower–level offenders already supervised by local probation departments. Specifically, the parolees we propose to shift to probation are convicted of property and drug offenses. We exclude offenders with current convictions for violent or sex offenses, though some of the lower–level offenders may have such offenses in their criminal history. Figure 4 lists the current offenses for which offenders would be transferred to probation supervision, as well as the number of current parolees.

|

|

|

Figure 4

Parolees Proposed for

Realignment to Local Probation |

|

June 30, 2007 |

|

Current Offense |

Number of

Parolees |

|

Property Offenses |

|

|

Second degree burglary |

7,482 |

|

Vehicle theft |

7,128 |

|

Petty theft with a prior theft |

6,159 |

|

Receiving stolen property |

4,920 |

|

Forgery/fraud |

4,104 |

|

Grand theft |

3,736 |

|

Other property offenses |

1,146 |

|

Subtotal, Property Offenses |

(34,675) |

|

Drug Offenses |

|

|

Drug possession |

19,046 |

|

Drug possession for sale |

12,057 |

|

Marijuana possession for sale |

1,280 |

|

Marijuana sales |

538 |

|

Other marijuana crimes |

179 |

|

Hashish possession |

49 |

|

Subtotal, Drug Offenses |

(33,149) |

|

Driving under the

influence |

3,539 |

|

Total, All Offenses |

71,363 |

|

|

Benefits Both State and Local Governments. Realigning these supervision responsibilities to local governments would yield benefits to both state and local governments. The state would save approximately $500 million from reduced parole caseloads, reincarceration of parole violators, and administrative costs. There would be less “churning“ of lower–level offenders repeatedly coming in and out of prison for short stays related to parole violations. This would reduce prison overcrowding, particularly in expensive reception center beds. Moreover, shedding lower–level offenders from the state parole caseloads would allow the department to refocus its parole mission on supervising the higher–level offenders that would remain on parole, including, for example, sex offenders and those offenders with a recent serious or violent offense on their record.

While this realignment proposal would significantly increase local probation caseloads and costs, it would also provide significant additional revenues for local probation and public safety programs. Our proposal would result in approximately a 25 percent increase in funding for local probation departments which we estimate spend about $2 billion annually now, though this also includes funding for juvenile probation. The 71,000 offenders shifted to local probation departments would constitute about a 20 percent increase in county caseloads on a statewide basis. Therefore, under our alternative, counties would receive significant new revenues with which to manage their new offenders, as well as to bolster programs for their existing populations. The additional funding provided to counties could be used for more intensive supervision, expansion of rehabilitation programs and services, and jail costs to reincarcerate probation violators. In may also make sense to allow counties to be able to use some of their revenues to reimburse the state for the use of state prison beds if they currently face overcrowding in their jails. As we discuss above, counties would have discretion as to how they would use this funding, providing them flexibility to manage this offender population as they determine appropriate, as well as to invest some of these funds in prevention or intervention programs that might yield significant improvements to public safety in the longer term.

Below, we discuss how this shift of responsibilities from the state to the counties would be financed.

Under our alternative, each county would create a Public Safety Realignment Account (PSRA) within its existing Local Public Safety Fund (discussed in detail below). Every county would deposit into its PSRA a portion of the property tax revenues currently allocated to water and waste enterprise special districts in the county.

Our alternative also creates a State Public Safety Realignment Account (SPSRA) and directs into this account (1) 6 percent of total statewide Proposition 172 sales taxes (approximately the share received by cities) and (2) about one–third of the VLF currently retained by the Department of Motor Vehicles. Funds from SPSRA, in turn, would be allocated to county PSRAs to the extent necessary to ensure that every county had sufficient resources to carry out its expanded supervision responsibilities. Counties could use PSRA resources for a broad range of services related to offender supervision, including rehabilitation and incarceration

We discuss the three revenue sources used in our financing plan (property taxes, Proposition 172 sales taxes, and VLF) separately below. We then describe how the LAO alternative would provide revenues to each county.

While most Californians receive water, sewer, and solid waste disposal service from a branch of their city or county government, some Californians are served by independently elected special districts. These water and waste special districts are called “enterprise” special districts because they (1) have broad authority to charge service fees and (2) account for their finances like private businesses.

Prior to Proposition 13, about one–half of these water and waste districts levied a property tax rate to offset part of their costs. Paying for water and waste services with property tax revenues was common throughout the United States at that time. (Since the 1970s, there has been greater reliance on variable–rate user fees to finance these services because the fees provide incentives to conserve and recycle.)

In 1978, Proposition 13 dramatically changed the fiscal landscape for local government. Specifically, Proposition 13 (1) reduced the average property tax rate from over 2.5 percent to 1 percent of assessed value and (2) gave the state the responsibility for determining how property taxes are allocated among local governments. To implement Proposition 13, the Legislature enacted measures, beginning with SB 154, Conference Committee (Chapter 292, Statutes of 1978) and AB 8, L. Greene (Chapter 282, Statutes of 1979). Under these laws, local governments that levied a property tax rate before Proposition 13 continue to receive a share of the property tax today. The only exceptions to this provision are if the local government dissolves or follows a statutory process to (1) shift its share of the property tax to another local government or (2) notify the county auditor that it no longer wishes to receive property tax revenues (in which case the auditor reduces the 1 percent property tax rate commensurately).

At the time the Legislature implemented Proposition 13, the Legislature recognized that the state’s reduced property tax rate would not be sufficient to maintain funding for all local government services. Accordingly, in 1978 the Legislature urged enterprise special districts to shift to user fee financing. Specifically, the Legislature stated in Government Code Section 16270:

The Legislature finds and declares that many special districts have the ability to raise revenue through user charges and fees and that their ability to raise revenue directly from the property tax for district operations has been eliminated by Article XIIIA of the California Constitution. It is the intent of the Legislature that such districts rely on user fees and charges for raising revenue due to the lack of the availability of property tax revenues after the 1978–79 fiscal year. Such districts are encouraged to begin the transition to user fees and charges during the 1978–79 fiscal year.

Notwithstanding this legislative intent, most water or waste districts that levied a property tax before Proposition 13 continue to receive property tax revenues today. To illustrate this link between modern property tax allocation and tax policies of the 1970s, the box on the next page describes a district (Los Trancos County Water District) whose ongoing need for property tax revenues has been eliminated, yet the district continues to receive property taxes. While the Los Trancos example is admittedly extreme, it illustrates the rigidity of the current property tax allocation system and its lack of connection with modern local needs and preferences.

Enterprise Special Districts Use of Property Taxes Today. In 2008–09, we estimate that waste and water districts will receive $370 million in property taxes. (This sum does not include property taxes collected in excess of the 1 percent rate and pledged to payment of bonded indebtedness.) Every county in California has some waste and water districts that receive property taxes, except San Francisco. Districts that receive property taxes (less than one–half of all waste and water districts statewide) typically rely on these revenues for less than 7 percent of their operating costs. Districts typically indicate that property taxes allow them to set lower service charges than providers that do not receive property taxes.

Under our alternative, county boards of supervisors would hold hearings to review the property tax revenues that waste and water districts receive. Counties would determine the amount to shift from each district to its PSRA. (As described in the shaded box on page 137, this approach draws heavily from legislation enacted on a one–time basis for the County of Santa Cruz, Chapter 905, Statutes of 1993 [AB 1519, Isenberg].)

As we describe more fully below in the section “How the Financial Model Would Work,” under our alternative, each county shifts to its PSRA 70 percent of countywide water and waste district property tax revenues, unless a lower percentage of property taxes would raise sufficient funds to support the realignment program. (This would be the case in 11 counties—Orange, El Dorado, Kern, Marin, and Placer and several small counties, where tax shifts of about 35 percent to 45 percent would raise the full amount needed.) The percentage of property taxes shifted from different districts need not be identical. For example, a county might decide to shift 5 percent of a small water district’s property taxes and 90 percent of a large waste district’s property taxes.

Statewide, we estimate that our alternative would shift about 50 percent of waste and water district property taxes—$188 million—to county PSRAs to support the realignment program. This property tax shift, in turn, would put pressure on districts to increase service charges.

Remaining Waste and Water Enterprise Special District Property Taxes. To minimize the near–term fiscal disruption to water and waste districts, our alternative leaves almost 50 percent, or $180 million, of property taxes with districts. Within a couple years, however, we think the Legislature should authorize county boards of supervisors to determine whether these property taxes should remain with the districts or be reallocated to other local governments to support local priorities. Because local communities have had no authority over property tax allocation in nearly 30 years, we are mindful that this process would engender concerns by special districts and significant public debate. While difficult, we believe that this result would be a sign of a healthy local democratic process, appropriately debating the allocation of local revenues.

In 1954, residents of a hilly, rural area in San Mateo County created an enterprise special district to provide water service and levied a property tax rate to help pay for this service. In 2005, the water district sold its entire water distribution system to a private company (a change that resulted in lower water service charges to the area’s residents). Although the water district no longer provides water service, the district did not dissolve or request that its property tax revenues be redistributed or eliminated. The water district continues to receive property taxes pursuant to current law. The district uses about one–half of these revenues to provide tax rebates to its residents and the rest for activities unrelated to water delivery.

By approving Proposition 172 in 1993, California voters established a statewide half–cent sales tax for support of local public safety activities. Proposition 172 was placed on the ballot by the Legislature and the Governor to partially replace $2.6 billion in property taxes permanently shifted from local agencies to school districts as part of the 1993–94 state budget agreement. (The value of this 1993–94 property tax shift has grown over time.)

Under Proposition 172, resources from the half–cent sales tax (almost $3 billion in 2008–09) are allocated to each county based on its share of statewide taxable sales. When Proposition 172 was considered initially by the Legislature, the measure did not direct counties to transfer any Proposition 172 revenues to cities. This is because Proposition 172 was considered property tax shift mitigation and cities bore a much smaller share of the 1993–94 property tax shift than counties (in fact, some cities were exempt from the 1993–94 property tax shift).

As the debate over Proposition 172 evolved, however, the Legislature determined that (1) cities which sustained a property tax shift in 1993–94 would benefit from some offsetting revenues and (2) allocating some Proposition 172 revenues to cities would broaden the measure’s political support. Accordingly, the Legislature modified the Proposition 172 allocation formula to direct each county to transfer a small share (about 6 percent) of its revenues to those cities in the county that sustained a 1993–94 property tax shift.

In 1993, the Santa Cruz County Board of Supervisors held public hearings to determine the relative need for funding for all enterprise special districts and the County Library Fund. The county reported to the Legislature that in the case of about 12 percent of the revenues the “districts provided convincing reasons for retaining all or part of the allocated taxes.” With regard to the remaining 88 percent of the taxes, however, the board concluded that “considerations of equity and appropriate use of tax funds” led them to conclude that depositing the property taxes into the County Library Fund was appropriate.

Controversy Regarding City Share of Proposition 172. In the years after the Legislature developed the Proposition 172 allocation formula, there has been significant controversy about the share of Proposition 172 allocated to cities. Some cities that do not receive Proposition 172 revenues (because they were not affected by the 1993–94 property tax shift) have argued that they should be included in its distribution because they provide public safety services. Cities and counties also have debated the percentage of county Proposition 172 revenues that should be transferred to cities.

When the Legislature drafted Proposition 172, it recognized that local government public safety and financing needs change over time. Accordingly, Proposition 172 gives the Legislature broad authority to modify how its revenues are allocated to local governments for public safety purposes.

Based on our review of state–local finance and the potential benefits of parole realignment, we think a revision to the allocation formula is reasonable. Specifically, due to strong growth in property taxes over the last decade, city expansion of redevelopment activities, and the significant fiscal benefit cities have realized under the 2004 VLF–for–property tax swap, city financial conditions appear stronger than they were at the time the Legislature earmarked for them a portion of Proposition 172 funding.

Under our alternative, cities do not receive Proposition 172 sales tax revenues. Instead, 6 percent of total statewide Proposition 172 revenues—approximately the amount cities receive—are deposited to the SPSRA and then allocated to county PSRAs as described in the section “How the Financial Model Would Work.” Cities’ loss of Proposition 172 revenues likely would result in commensurate program reductions. As a point of reference, we note that Proposition 172 funding represents about 1 percent of city tax revenues and less than 2 percent of city spending for public safety.

When one government collects revenues on behalf of another, it is common for the revenue–collecting government to retain a portion of the revenues to cover its administrative costs. The DMV collects VLF on behalf of cities and counties and retains a portion of these revenues to offset its costs.

When the Governor reduced the VLF rate in 2004 from 2 percent to 0.65 percent, the administration was concerned that DMV would experience fiscal stress from a commensurate reduction in its retained VLF

revenues. (The amount of VLF that DMV retains is calculated under a statutory formula that uses as a factor the total amount of VLF collected.) Accordingly, the administration proposed that DMV be allowed to calculate the amount of its retained VLF under the assumption that the VLF rate was still 2 percent. The Legislature enacted this change into law (Revenue and Taxation Code 11003 and Vehicle Code 42205).

This change to DMV’s calculations was discussed with cities and counties when the VLF for property tax swap was negotiated in 2004 and its fiscal effect was incorporated into the final tax swap agreement. Cities and counties, therefore, are not “worse off” because DMV retains its pre–2004 funding from VLF. Instead, the cost to maintain DMV’s pre–2004 funding from VLF is born by the state General Fund. This is because the state shifted a larger share of K–14 property taxes to cities and counties under the VLF swap than would have been the case if DMV’s VLF revenues had been based on the lower rate.

In 2008–09, we estimate that DMV will retain $130 million more VLF than would be the case if DMV’s funding from the VLF reflected the current 0.65 percent VLF rate. In our view, there is little reason for the state General Fund to pay indirectly part of the cost of the DMV, a department that historically has been financed by user fees.

Our alternative would repeal the provisions of law that allow DMV to calculate its retained VLF revenues under the assumption that the VLF rate is still 2 percent. As a result, DMV would retain $209 million of VLF for administrative purposes, rather than the $339 million proposed in the Governor’s budget. The $130 million of reduced VLF retained by DMV would be deposited to SPSRA for allocation to the counties.

The DMV, in turn, likely would need to increase vehicle registration fees to offset this reduction in VLF support. We estimate that this fee increase would be approximately $4 per vehicle.

Our financing approach provides counties reliable revenues to support their increased responsibilities, authority to use these resources flexibly to provide services offenders need, and incentives to improve program outcomes.

Specifically, under our model, counties receive a total of $495 million of reallocated property tax, sales tax, and VLF revenues to support the realigned program. The $495 million is $12 million more than the amount the 2008–09 state budget includes for state supervision of lower–level parolees

($483 million). Under our approach, the additional $12 million would be allocated to counties as incentive payments (discussed below).

Because the distribution of parolees per 1,000 residents is fairly uniform among counties, our model assumes that each county’s parole funding level would reflect its proportionate share of the statewide population. (As an alternative, the Legislature could base parole funding on the number of people in the age group most likely to offend.)

Figure 5 illustrates how the financial approach would work. Hypothetical counties “A,” “B,” and “C” have identical sized populations. Thus, our model assigns them identical parole funding levels. The resources used to meet the three counties’ parole funding levels differ, however, due to differences in the amount of property taxes their water and waste districts receive. As shown in Figure 5, County A’s districts receive a large amount of property taxes. As a result, County A meets its parole funding level by reallocating 45 percent of these district property taxes to its county PSRA.

|

|

|

Figure 5

How Parole Realignment Financing Would Work |

|

(Dollars in Millions) |

|

|

Hypothetical Countiesa |

|

|

A |

B |

C |

|

Parole Realignment Allocation |

$10.0 |

$10.0 |

$10.0 |

|

Funding Sources |

|

|

|

|

Water and waste district property taxes |

|

|

|

|

County totals |

22.0 |

10.0 |

5.0 |

|

Amount allocated to PSRAb |

10.0 |

7.0 |

3.5 |

|

Percent reallocated |

45.0% |

70.0% |

70.0% |

|

Support from

SPSRAc |

— |

$3.0 |

$6.5 |

|

|

|

a Counties have

same population so their funding levels are identical. |

|

b The lesser of

the amount needed for realignment funding (in this case, $10

million) or 70 percent of total property taxes is deposited to

each county�s Public Safety Realignment Account (PSRA). |

|

c State Public

Safety Realignment Account, which consists of certain

Proposition 172 funds and reallocated Department of Motor

Vehicles vehicle license fee revenues. |

|

|

Water and waste districts in County B and C, in contrast, receive fewer property taxes. After County B and C reallocate the maximum percentage of property taxes (70 percent under our approach), these counties still do not have enough resources to reach their parole funding levels. Accordingly, County B and C receive support from SPSRA. The revenues in this account come from the cities’ share of Proposition 172 revenues and excess VLF revenues currently retained by DMV.

County Incentive Payments. We estimate that the SPSRA would have about $12 million more in revenue than needed to bring each county to its parole funding level. For the first three years of realignment, our alternative allocates this sum to counties on a per capita basis to offset administrative costs associated with the program change. After three years, however, this funding would be allocated by the state to counties making the greatest strides towards reducing recidivism and state incarceration.

How Would the Funding Allocation Change Over Time? Every five years, these funding allocations would be updated to reflect changes in population. The amount of resources would grow over time along with the specific growth patterns of each revenue source’s underlying revenue base (the property tax, VLF, and sales tax). In this way, each county’s parole resources would grow commensurately with its population and the strength of three tax sources.

Realigning supervision responsibilities for lower–level offenders from the state to counties has potential to significantly improve program outcomes. Any plan of this magnitude, however, raises practical, policy, legal, and financial questions. This is particularly true given the fiscal challenges the state is facing and the Constitution‘s many requirements regarding local finance. In this concluding section, we discuss several major questions related to this realignment proposal.

- What ongoing coordination between state and local governments will be required?

- How should financial incentives be arranged to ensure the best outcomes?

- How can the transition of responsibilities be best managed to mitigate the operational impact to the state and counties?

- What steps could the Legislature take to achieve state savings in 2008–09?

- Would parole realignment impose a state–reimbursable mandate?

- Would the financing plan conflict with the provisions of Proposition 1A?

The transition of state inmates to county probation departments would require a level of coordination that does not currently exist between these agencies. However, for realignment to work, it would be critical to establish standard processes of communication. In particular, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) would need to communicate to probation departments information on which state inmates are being released to probation supervision and when. This should include all relevant information about the offender that may be important for probation supervision, such as criminal history, residence, and the outcome of any assessments of the offender’s risk to reoffend or needs for various programs and services.

County probation would also need to provide information to the state. For example, CDCR would need to be able to inform inmates releasing to county probation where and to whom they are required to report when they return to the community. It would also be important for counties to be able to track the outcomes of probationers formerly in state prison and provide that information to the state in order to determine how to distribute the $12 million of incentive funds proposed.

As discussed above, realignment should result in better incentives for local governments to manage this population and invest in sound prevention and rehabilitation programs. However, with any change of this magnitude, it is important to ensure that the change provides sufficient incentives for the outcomes desired. In this case, that outcome is improved public safety.

One potential concern is whether counties could use the new public safety revenue to supplant existing funds used for this purpose, and divert existing public safety dollars to other county programs. This could result in a negative impact on local public safety. Therefore, it may be worth considering including a maintenance–of–effort requirement for parole realignment.

Another potential concern is whether counties would use their new revenues to sufficiently invest in prevention and rehabilitation programs designed to reduce recidivism and improve public safety. We recommend that the realigned funds be placed in a newly created PSRA in each county’s Local Public Safety Fund. The Legislature will want to consider how counties would be able to use funds deposited in their PSRAs. We would suggest that these funds be designated for probation supervision, rehabilitation programs and services, incarceration of probation violators, and prevention programs.

As discussed above, we also recommend that $12 million of the SPSRA be set aside to reward those counties that show the greatest reductions in offender recidivism. This should provide additional incentive to counties to focus on this specific public safety outcome. However, the Legislature will need to determine how this outcome will be measured. For example, will the incentive be based on county crime rates or prison commitments? Will the incentive be determined by recidivism of all county probationers or just those offenders formerly in state prison?

Clearly, parole realignment would have significant operational impacts for both the state and counties, particularly during the time it takes the program transition to occur. For example, counties would need to hire hundreds of additional probation officers to supervise the new offenders, and the state would likely have to reduce its total parole agent positions. The Legislature may want to explore whether there are strategies available to ease the transition of state parole agents to county probation offices for those who would want to transfer. Similarly, counties would likely need to expand rehabilitation services—such as drug treatment, mental health services, and employment assistance—for their probationers, and the state may have to reduce or alter its existing rehabilitation services to meet the programmatic needs of the remaining parolee population. Finding ways to manage this transition effectively would better ensure successful outcomes.

Ideally, state and local governments would have a couple years to plan the implementation of parole realignment. This would allow ample time to address personnel issues and resolve administrative matters. Given the state’s fiscal challenges, however, we believe the realignment could be implemented to allow the state to realize savings in 2008–09, while giving the state and counties time to work out transition issues.

To accomplish this, the Legislature would enact urgency legislation making this parole realignment effective on July 1, 2008. That is, on that date the counties would have the fiscal responsibility for the parolees shifted to them, as well as the new revenues. The counties, however, would not have to provide the actual supervision services at the local level as of July 1, 2008. They would have up to one year to address personnel, facilities, and other administrative issues before actually providing the services locally. During that transition, the state would continue to supervise these lower–level parolees and the counties would reimburse the state for its costs. (This would be fiscally neutral for the counties, as they would have the additional revenues to pay the state for these transitional services.) These county reimbursement payments to the state would cease when the county assumed supervision responsibility.

Under the California Constitution, the state generally must provide a subvention of funds to local governments if it mandates “a new program or higher level of service” which increases local governments’ costs.

Would this program realignment be considered a mandate? State law is not clear. The underlying rationale for mandate law is to safeguard local governments from incurring additional costs to implement required new programs. Because our alternative provides revenues that fully offset counties’ increased responsibilities, our alternative does not appear to impose a mandate. Case law is not clear, however, whether tax revenues reallocated from other local governments would count as an offset for purposes of determining whether a mandate exists.

Given the magnitude of revenues included in this realignment proposal, the Legislature should consider taking one or more of the following steps to reduce the possibility that this plan would be found to be a reimbursable mandate:

- Amend the Government Code to specify that additional tax revenues allocated to a local government shall be considered offsetting revenues in any mandate determination. (Existing law provides that fee revenues count for such purposes.)

- Place the proposed realignment before the state’s voters on the June or November 2008 ballot. (Measures approved by voters are not considered reimbursable mandates.)

- Enact the proposed realignment only if all counties pass a resolution requesting that the Legislature approve the plan and shift parole supervision responsibilities to them. (Measures requested by local governments are not considered reimbursable mandates.)

Proposition 1A, approved by the state’s voters in 2004, amended the California Constitution to reduce the Legislature’s authority over local finance. Nothing in this realignment plan, however, conflicts with the requirements of Proposition 1A. Specifically, Proposition 1A does not limit the Legislature’s authority to reallocate Proposition 172 revenues or VLF retained by DMV.

In terms of property taxes, Proposition 1A specifies that laws that shift property taxes from one (noneducation) local government to another must be approved by a two–thirds vote of the Legislature. Accordingly, we would assume that the legislation granting counties the authority (and responsibility) to transfer district property taxes would be subject to the two–thirds vote requirement.

Successfully reintegrating criminal offenders into society requires a coordinated approach, including offender supervision, as well as the provision of mental health, substance abuse, and other types of treatment and programs. In California’s current criminal justice system, counties operate most of these programs, but the state is responsible for supervising offenders released from state prison.

For many years, this office has recommended the Legislature (1) shift state parole responsibilities to counties and (2) give counties the funding and flexibility to operate these programs so that they achieve the best public safety outcomes.

In our view, realigning parole responsibilities makes policy sense regardless of the state’s fiscal condition. In light of the state’s fiscal challenges, we have developed an approach that would allow the Legislature to realign a significant portion of the state parole program and achieve nearly $500 million in ongoing budget solution.

Return to Perspectives and Issues Table of Contents, 2008-09 Budget AnalysisReturn to Full Table of Contents, 2008-09 Budget Analysis