The California Constitution vests the state’s judicial power in the Supreme Court, the Courts of Appeal, and the trial courts. The Supreme Court, the six Courts of Appeal, and the Judicial Council of California, which is the administrative body of the judicial system, are entirely state–supported. The Trial Court Funding program provides state funds (above a fixed county share) for support of the trial courts. Chapter 850, Statutes of 1997 (AB 233, Escutia and Pringle), shifted fiscal responsibility for the trial courts from the counties to the state. California has 58 trial courts, one in each county.

The Judicial Branch consists of two components: (1) the judiciary program (the Supreme Court, Courts of Appeal, Judicial Council, and the Habeas Corpus Resource Center), and (2) the Trial Court Funding program, which funds local superior courts.

The 2005–06 Budget Act merged funding for the judiciary and Trial Court Funding programs under a single “Judicial Branch” budget item. It also shifted local assistance funding for a variety of programs, including the Child Support Commissioner program, the Drug Court Projects, and the Equal Access Fund from the Judicial Council budget to the Trial Court Funding budget.

Budget Proposal. The Judicial Branch budget proposes total appropriations from all fund sources of just under $3.7 billion in 2008–09. This is a decrease of $14 million, under one–half percent below revised current–year expenditures. As illustrated in Figure 1, the budget proposes an unallocated reduction of about $246 million in General Fund support that is applied to the budget after proposals that would increase the amount allocated to the judicial branch from the General Fund. The net effect is total General Fund expenditures of $2.2 billion, a decrease of about $20 million, or less than 1 percent, below estimated current–year expenditures. Total expenditures from special funds and reimbursements are proposed at about $1 billion, an increase in spending of about $7 million, or less than 1 percent. The counties’ contribution of support remains unchanged at almost $500 million.

|

|

|

Figure 1

Judicial Branch Funding—All Funds |

|

2006-07 Through 2008-09

(Dollars in Millions) |

|

|

|

|

|

Change From

2007-08 |

|

|

Actual

2006-07 |

Estimated

2007-08 |

Proposed

2008-09 |

Amount |

Percent |

|

Judiciary Program |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Supreme Court |

$42 |

$45 |

$48 |

$3 |

6.7% |

|

Courts of Appeal |

187 |

201 |

219 |

18 |

9.0 |

|

Judicial Councila |

155 |

201 |

248 |

47 |

23.4 |

|

Habeas Corpus Resource Center |

13 |

14 |

15 |

1 |

7.1 |

|

Subtotals |

($397) |

($461) |

($530) |

($69) |

(15.0%) |

|

Trial Court

Funding Program |

$3,037 |

$3,248 |

$3,411 |

$163 |

5.0% |

|

Unallocated cut |

— |

— |

-246 |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

$3,434 |

$3,709 |

$3,695 |

-$14 |

-0.4% |

|

|

|

a Includes funding

for the Judicial Branch Facility Program. |

|

Detail may not

add due to rounding. |

|

|

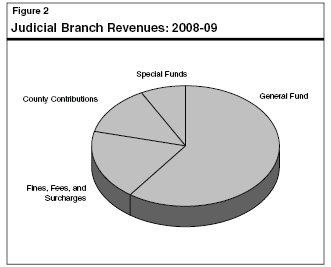

Approximately 92 percent of total Judicial Branch spending is for the Trial Court Funding program, and the remainder is for the judiciary program, although this split in funding could change depending upon how the proposed General Fund reduction of $246 million was eventually allocated. Figure 1 shows proposed expenditures for these two major program components (the Judiciary Program and the Trial Court Funding program) in the past, current, and budget years, while Figure 2 shows the revenue sources for the entire Judicial Branch.

Proposals to Increase and Decrease Judicial Spending. The major increases in spending proposed in the Judicial Branch budget are annual adjustments for growth and inflation ($126 million), adjustments for the cost of new or expanded programs ($72 million), and increases for the cost of implementing recent legislation to increase oversight of conservators and guardians ($17 million). Most of these proposals for increased spending are for the Trial Court Funding program.

The Governor’s budget also includes a proposed unallocated reduction of approximately $246 million in General Fund support in the budget year. At the time this analysis was prepared, the Judicial Branch had not presented a plan indicating what programs it planned to reduce in the event such a reduction was adopted.

The Governor’s budget proposes an unallocated reduction of $246 million in General Fund support for the Judicial Branch. The Legislature should adopt a savings target of greater or lesser than this amount that is consistent with its own overall program and spending priorities and with consideration for any funding priorities identified by the courts. The Legislature should also evaluate the impact of spending reductions on court services.

Putting the Proposed Reductions in Perspective. As noted earlier in this analysis, the 2008–09 budget plan proposes a $246 million reduction in the Judicial Branch budget. The spending reduction is not allocated among the various components of the judiciary, consistent with the administration’s policy of leaving out such specifics for “General Fund budgets not under the control of the administration.”

The 10 percent reduction is proposed to be applied against the workload budget for the courts, as estimated by the Department of Finance. This is generally consistent with the administration’s approach for applying 10 percent reductions to a number of other state programs and departments. In the case of the Judicial Branch, the proposed $246 million reduction in the budget for the courts is applied after $226 million in spending increases have been incorporated into the judicial budget. Thus, the net effect of the spending plan, as proposed by the Governor, is a fairly minor reduction in support of less than one–half percent when compared with the previous year’s budget.

Whether the courts should absorb a cut of this magnitude, or one that is larger or smaller in scale, is fundamentally a question relating to the Legislature’s own spending and program priorities. The administration has proposed that the courts themselves determine how this reduction would be achieved. While we believe the Legislature should carefully consider the advice of the courts when setting their funding level, should it choose to make a reduction, how any cut is made is also an important decision for the Legislature. A budget reduction of this size could significantly affect trial court operations, with civil cases disproportionately bearing the brunt of any delays in trials that resulted from a shortfall in available resources. That is because statutorily enforced time lines would force the judicial branch to give criminal cases higher priority in order to prevent the dismissal of charges against defendants.

A Number of Budget–Balancing Options Exist. With these factors in mind, we outline several possible approaches for the Legislature to consider in implementing a major reduction for the Judicial Branch that our analysis suggests would help the state to achieve its savings goals while minimizing (but by no means eliminating) the impacts on services to the public. These options include suspending State Appropriations Limit adjustments and using significant existing fund balances at the trial court level to buffer against loss of state funding. They also include the adoption of cost–saving operational changes in trial courts, adjusting the budget for delays in the appointment of new judges, and increasing court revenues. The fiscal effect of these options, which we discuss in more detail below, are summarized in Figure 3. They could result in as much as $176 million in savings in 2008–09 and as much as $358 million in ongoing savings upon their full implementation.

|

|

|

Figure 3

LAO Options for Cost Savings in the Judicial

Branch |

|

(In Millions) |

|

Option |

2008–09

Fiscal Impact |

Annual

Ongoing Savingsa |

|

Suspension of SALb |

$126 |

$126 |

|

Electronic court reporting |

13 |

111 |

|

Court security |

— |

100 |

|

Delays in judicial appointments |

15 |

— |

|

Civil filing fee increase |

21 |

21 |

|

Totals |

$175 |

$358 |

|

|

|

a When fully

implemented. |

|

b State

Appropriations Limit. |

|

|

The Legislature should consider the option of suspending, on a one–time basis, automatic adjustments in funding for the trial courts. This option would result in state savings of $126 million in 2008–09 that would grow modestly in subsequent years.

Background. Chapter 227, Statutes of 2004 (SB 1102, Committee on Budget), changed the process for budgeting the Trial Court Funding program. The state shifted from the traditional state budget process—in which annual adjustments are separately requested and approved based on demonstrated need—to a process in which the amount of new funding for this program is based on a formula and does not require demonstration of need. The adjustment is made based upon the SAL, a measure to limit the overall growth of certain state government costs that is also used to adjust the budgets of certain other agencies. The SAL growth rate is multiplied by an adjusted cost of operating the trial courts for the previous year. The result is the additional amount of General Fund support the state must allocate to the trial courts, over and above the amount allocated the previous year. For a more in–depth discussion of SAL adjustments, please see page

D–15 of the Analysis of the 2006–07 Budget Bill.

Trial Courts Have Significant Revenues and Reserves. As directed by the Supplemental Report of the 2006–07 Budget Act, the Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC) submitted a report on individual trial court financial statements for 2006–07. The report suggests that, on a collective basis, trial courts are in a strong financial condition. Specifically, in 2006–07, the aggregate amount of revenue received by the 58 superior courts exceeded their expenditures in that same fiscal year by $54 million. In addition, the total amount of assets that remained unspent in 2006–07 totaled $590 million. Only about $235 million is classified as having being restricted by contractual or statutory obligations, leaving $355 million that had not been obligated. Data for 2007–08 revenues, expenditures, and fund balances will be forthcoming in December 2008.

Legislative Option. Given the state’s fiscal difficulties, the Legislature should consider the option of suspending the SAL adjustment for 2008–09 and letting the trial courts use their considerable reserves to buffer against the loss of state funding. This action could have some effect on information technology and other types of projects to improve court operations, as the courts have indicated they plan to use the unobligated funds for such projects. On the other hand, we believe the trial courts could prioritize the use of their reserves to move forward with their highest priority projects even with a suspension of the SAL adjustment. Because the SAL spending increase received by the trial courts is calculated, in part, on the General Fund support provided in the previous year, a one–time suspension of the SAL would lead to ongoing and modestly growing savings. The Legislature would have to adopt trailer bill legislation to suspend SAL for 2008–09, but no further legislative action would be needed to achieve these ongoing savings.

The state has the option of saving a substantial amount of funding, and of better meeting the reporting needs of the courts, if it transitioned from court reporters to electronic methods of recording court proceedings. This approach could result in net state savings of $13 million in 2008–09 that could grow over the subsequent fiscal years to as much as $111 million annually.

Background. Current law requires the use of certified shorthand reporters to create and transcribe the official record of most court proceedings. Typically, the court reporter is the sole owner of all the equipment necessary to perform his or her duties, including the stenotype machine, computer–aided software for transcription, and all the elements involved in producing the transcript. Also, for the most part, the court reporter transcribes the record on his or her own time, outside of the eight–hour work day. For these reasons, the transcripts are “owned” by the court reporter and must be purchased by the court. In addition to paying for the first copy, the court must also pay a reduced rate for additional copies. In 2006–07, the total amount spent on such transcripts was nearly $26 million, while the total amount spent on salaries and benefits for court reporters was about $202 million.

In contrast, electronic court reporting involves using video and or audio devices to record the statements and testimony delivered in the courtroom. Depending on the system used, a monitor may be assigned to oversee the proper functioning of the equipment and provide replays of statements upon request of the judge, though some systems are available that can be used without a monitor. Following a proceeding, typed transcripts can be created by transcription services for use by court staff, attorneys, or in any subsequent appeal. However, the actual recordings created during the proceeding can also be used in a manner similar to a transcript, and the sales of these recordings can generate the court additional revenue.

Electronic Reporting a Well–Established, Cost–Effective Practice. Electronic court reporting is in widespread use in many state and Federal courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court. Moreover, electronic court reporting was demonstrated to be cost–effective in a multiyear pilot study carried out in California courts between 1991 and 1994. Chapter 373, Statutes of 1986 (AB 825, Harris), enacted a four–year demonstration project to assess the costs, benefits, and acceptability of using audio and video reporting of the record except in criminal or juvenile proceedings. The project found significant savings of $28,000 per courtroom per year in using audio reporting, and $42,000 per courtroom per year using video, as compared to using a court reporter. For a more complete discussion of electronic court reporting, its use in other states, and the results of the Judicial Council study, please see the

Analysis of the 2003–04 Budget Bill (page D–22).

Electronic Court Reporting May Help Address Short Supply of Court Reporters. A persistent problem facing the courts is the short supply of certified shorthand reporters, who, by statute, are the only individuals qualified to make transcripts of most trial court proceedings. In 2005, the Judicial Council released the findings of its Reporting of the Record Taskforce. The taskforce indicated, based on comments from trial court officials, that the pool of court reporters has been dwindling since the mid–1990s and is insufficient to meet their needs.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, it can take anywhere from two to three years to become proficient in court reporting techniques. By statute, an individual can only become a certified shorthand reporter if he or she passes an examination administered by the Court Reporters Board of California. Eligibility for the exam is limited to those who have some experience, or have passed the state hearing reporters examination, or those who have past certification from one of several different sources. The number of people passing the exam has declined since the mid–1990s. In November 1995, a high of 309 individuals successfully passed the examination required to become a certified shorthand reporter, while in October 2007 only 38 achieved passing scores. The dwindling supply of reporters is compounded, as is pointed out in the report, by the fact that those passing the exam may choose to seek work outside of the courts in professions like closed captioning, deposition reporting, or in providing translation services to the hearing–impaired.

In contrast, the Bureau of Labor Statistics indicates that electronic court reporters usually learn their skills on the job. There is currently no certification requirement for electronic court reporters in California. As a result of these factors, the pool of eligible candidates for electronic court reporting would likely be both larger and more easily expanded than the pool of eligible candidates for court reporting.

Electronic Court Reporting Could Save the State Millions Annually. Based upon our past review of other states and the pilot project mentioned above, we believe that electronic reporting is a reliable and cost–effective alternative to the system of court reporting currently used in California’s trial courts. Our inflation–adjusted analysis of the pilot study indicates that, if electronic court reporting had been operational in 2006, the state would have saved nearly $89 million on trial court operations. This represents an estimated savings of nearly 60 percent for reporting activities. Even greater savings may now be possible with more modern technology that has become available since the California pilot projects. According to estimates from the 9th Circuit Court of Florida, the cost of providing all 20 Florida circuit courts with court reporters is around $36 million, but would be only $5 million if those courts used electronic reporting—a potential savings of 86 percent.

Legislative Option. To both address the shortfall in the supply of court reporters and reduce state costs for trial court operations, we recommend that the Legislature consider the option of directing the courts to begin now to implement electronic court reporting in California courtrooms.

In order to allow transition time, one approach would be to direct that 20 percent of courtrooms in California switch to electronic court reporting on an annual basis. After factoring in the estimated one–time costs of the equipment, our analysis indicates that this may result in nearly $13 million in savings during 2008–09. By 2010–11, annual savings from the switchover to electronic reporting could reach $53 million. If electronic court reporting were fully operational in all California courtrooms we estimate that savings could reach $111 million on an annual basis. This option would require a statutory change.

In order to allow the courts to gain greater control of rapidly escalating security costs, the Legislature should consider directing the courts to contract for court security on a competitive bidding basis with both public and private security providers. This option would result in only a minor state savings in 2008–09, but potentially in savings of $100 million or more at full implementation on a statewide basis.

Background. Current law requires trial courts to contract with their local sheriff’s department for court security. Courts thus have little opportunity to influence either the level of security to be provided or the salaries of those security officers, but are expected to pay the full amount of each. In most cases, the county sheriff determines the minimum level of security required in a court facility. In addition, the county board of supervisors, as opposed to the court, negotiates the level of salaries and benefits with the sheriff. These costs have grown rapidly in recent years. Specifically, total security costs have increased from about $263 million in 1999–00 to about $450 million in 2006–07, the last year of complete data. This amounts to an average annual increase of 8 percent. Judicial Council staff have attributed the growth largely to negotiated salary increases for sheriff’s deputies.

Courts Currently Lack the Ability to Contain Security Costs. Because the courts are required to contract only with county sheriffs, the sheriff has no incentive to contain costs of the security provided, and the courts have no recourse to ensure they do. Establishing a competitive bidding system for court security, in contrast, would provide an incentive for whichever public agency or private firm won the bid to provide court security in the most cost–effective manner possible. A competitive bidding system would also enable courts to exercise more control over the level of security provided to their courts. Courts would be able to select among the proposals offered to them by different security providers, thus allowing them to select the level of security that best meets their needs.

Legislative Option. We believe that allowing courts to contract with private security companies, the California Highway Patrol, as well as local law enforcement agencies would likely result in significant state savings. In a 2003–04 analysis of Los Angeles Superior Court security costs, (please see the

Analysis of the 2003–04 Budget Bill, page D–17), we estimated that competitive bidding could reduce spending on trial court security from 14 percent to 71 percent, depending upon the mix of public sector and private firms awarded contracts.

It would take time to phase in such a new system, including as much as a year for the preparation of bids and allowing a suitable time for potential private and public sector bidders to respond to such an opportunity. (This delay would also provide sheriffs with some lead time to adjust to the new competitive bidding environment.) Thus, the savings from such a change in 2008–09 would probably be minor, and some new costs might be incurred by the state on a one–time basis to develop a model solicitation for bids and a model contract to implement such new arrangements. The AOC could also incur additional ongoing costs to administer such contracts. However, our analysis suggests that these administrative costs would be exceeded by significant savings on security costs which could begin to be realized in 2009–10. Within a few years, depending upon how this change was implemented, the net savings could exceed $100 million annually.

The Legislature should consider adjusting the budget for the trial courts to reflect a more realistic timetable for the appointment of 50 new judgeships created in 2007–08 as well as 50 additional judgeships proposed for 2008–09. This option could reduce state spending by as much as $15 million in 2008–09.

Background. Chapter 390, Statutes of 2006 (SB 56, Dunn) and Chapter 722, Statutes of 2007 (AB 159, Jones), created 100 new judgeships over a two–year period—2006–07 and 2007–08. Fifty judges were to be appointed in the last month of each fiscal year and were budgeted accordingly. Pending the passage of legislation authorizing them, the budget plan assumes the creation of 50 additional judgeships in 2008–09.

Delays in Judicial Appointments Have Created Significant Savings. Recent history indicates that the appointment of new judges has been out of sync with the funding provided in the budget for these new positions. Delays by the Governor in appointing the first 50 judges established in 2006–07 resulted in savings of nearly $3 million—ten positions, as of the time this analysis was prepared, still were not filled.

Legislative Option. Currently the Governor is appointing judges at the rate of approximately five per month. At this rate between February 2007 and June 2009 there will be an average of nearly 16 unfilled judgeships at any given time. If the Legislature were to adjust the level of funding provided for these judgeships to reflect the actual rate at which these appointments are being made, while leaving one–time funding available for equipment and facilities costs to accommodate new judges, we estimate this would result in almost $15 million in savings in 2008–09.

The Legislature should consider the option of increasing civil filing fees because these state revenues are not keeping pace with the increase in costs of court operations. This option could allow an offsetting reduction in General Fund support for the courts in order to achieve state savings of $21 million in the budget year.

Background. The trial court system imposes civil fees on parties filing papers related to litigation. For example, the initial filing in a civil case seeking damages is typically $320, while the charge for filing the legal papers to respond to such a filing is also $320. The attorney handling a legal action generally pays such fees, except in cases where an individual is representing him or herself and therefore pays the fees personally. The revenue from these fees is intended to offset part, but not all, of the expense incurred by the court that is associated with these cases. These expenses include the administrative costs of setting up hearings, notifying the parties involved, and, in cases where the case goes to trial, the costs associated with conducting the proceedings.

Share of Support for Courts From Civil Fees Has Declined. The trial courts have a variety of funding sources to support their operations, including money collected from the counties that operated the trial courts before the passage of Chapter 850, federal funds, civil and criminal violation assessments, fines, forfeitures, and court filing fees and surcharges. However, the General Fund shoulders the majority of trial court costs, and trends indicate that the General Fund share is growing.

After the enactment of the 2005–06 Budget Act, when the trial court budget was reorganized into its current form, the General Fund portion of trial court funding was about $1.4 billion or 53 percent of the total, as can be seen in Figure 4. By 2008–09, the General Fund portion is projected to rise to about $2 billion, around 60 percent of the total. This represents an expansion of General Fund support of more than $600 million or 42 percent in the span of four years. The total cost of the court system from all fund sources grew by almost $700 million in this period. Thus, General Fund expenditures have grown disproportionately, covering about 86 percent of the increase in expenditures on trial court operations.

|

|

|

Figure 4

Trial Court Funding Between 2005-06 and

2008-09 |

|

(Dollars in Millions) |

|

|

2005–06 |

2006–07 |

2007–08 |

2008–09 |

|

Total trial court funding |

$2,714 |

$3,037 |

$3,248 |

$3,411 |

|

General Fund |

1,446 |

1,672 |

1,865 |

2,047 |

|

TCTFa

fee and surcharge revenue |

391 |

421 |

429 |

424 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Changes Between 2005–06 and 2008–09 |

Increase |

Percent |

|

|

|

Total trial court funding |

$697 |

26% |

|

|

|

General Fund |

601 |

42 |

|

|

|

TCTF fee and surcharge revenue |

33 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

a Trial Court

Trust Fund. |

|

|

This large increase from the General Fund indicates that the alternative sources of funding used by the trial courts are supporting a lesser share of trial court costs than they once did. For example, total fine and surcharge revenue deposited in the Trial Court Trust Fund (TCTF), which consists primarily of civil fee revenue for trial courts, was about $391 million in 2005–06. By 2008–09, the budget projects this to reach $424 million, representing an increase of 8 percent, in contrast to the 42 percent increase in General Fund support discussed previously.

Fee Increases Not Keeping Up With Inflation. The Uniform Civil Fees and Standard Fee Schedule Act of 2005 (UCF), part of the 2005–2006 Budget Act, reorganized many of the existing civil filing fees effective January 1, 2006, increasing some fees to create uniform statewide fee rates. The measure also stipulated that fees would remain unchanged until December 31, 2007. Since fiscal year 2005–06, however, projections of the U.S. State and Local Deflator, a measure of prices associated with goods and services purchased by state and local governmental entities, indicates that prices will have increased by just under 10 percent by 2008–09. Thus, while costs for operating the trial courts have increased, the fees charged to offset a portion of these costs have remained unchanged.

A Modest Fee Increase Could Generate Trial Revenue and Savings. Based on our analysis of estimates provided by Judicial Council staff, an increase just under 10 percent in certain selected filing fees (to reflect the inflation measure cited above) could generate as much as $21 million in increased revenue for the trial courts in 2008–09. This would amount to an average increase in fees of about $26 per filing. Such an increase would help offset the increase in cost of providing services associated with the trial courts and would help reduce the increased reliance on the General Fund. It is possible that such a fee increase could result in a reduction of the number of civil cases filed in court. While this means the courts might forego some additional revenues, the fiscal effect on the courts would likely be a net reduction in costs that would exceed any revenue loss. That is because the selected fees we propose be increased do not fully cover the cost the trial courts bear for the services associated with the filings. Any reduction in revenue due to decreased caseload would probably result in net savings for the trial courts.

Legislative Option. To reduce increasing General Fund expenditures and rising costs of operating the trial courts, the Legislature should consider the option of increasing civil filing fees to reflect inflation since 2005–06. If it takes such an action, the Legislature should also reduce General Fund expenditures for the trial courts accordingly, by about $21 million in 2008–09.

Return to Judicial and Criminal Justice Table of Contents, 2008-09 Budget AnalysisReturn to Full Table of Contents, 2008-09 Budget Analysis