Under the direction of the Attorney General, the Department of Justice (DOJ) enforces state laws, provides legal services to state and local agencies, and provides support services to local law enforcement.

Budget Proposal. The budget proposes total expenditures of approximately $791 million from all fund sources for support of DOJ in the budget year, which represents a $44 million, or about 5.3 percent, reduction from the revised current–year level of spending. Total General Fund support for the department in the budget year is $381 million, which represents a decrease of about $36 million, or 8.7 percent, relative to the adjusted current–year level. The spending plan proposes $328 million in expenditures from special funds, $42 million from federal funds, and $40 million from reimbursements.

Spending Reductions Partly Offset With Some Spending Increases. The significant net decrease in the DOJ budget is primarily due to an unallocated budget–balancing reduction of $42 million General Fund. At the time this analysis was prepared, DOJ had not presented a plan indicating how it planned to reduce its expenditures in the event such a reduction was adopted. In addition, the DOJ spending plan includes about $15 million in General Fund savings from technical adjustments, reflecting the expiration of limited–term positions or one–time expenditures in 2007–08 that will not continue into the budget year.

About $7.2 million from the General Fund is allocated within the budget to account for the continuing cost of employee compensation increases that took effect in 2007–08. The budget also includes increases in spending for some particular units within the department, the largest being $5.4 million budgeted from the General Fund to permanently continue the operation of the Gang Suppression Enforcement Teams (GSET) program. The GSET program was first introduced in 2006–07 with 34 staff on a two–year, limited–term basis. Also, $4.3 million from the General Fund would be provided to add about 26 staff to the correctional writs and appeals unit.

The Governor’s budget proposes an unallocated reduction of $42 million in General Fund support for the Department of Justice (DOJ). The Legislature should adopt a savings target of greater or lesser than this amount that is consistent with its own overall program and spending priorities, and with consideration for any funding priorities identified by the department. If the Legislature does choose to enact major spending reductions in this area, there are some options for doing so that would help reduce the direct impact on DOJ’s missions of representing the legal interests of the state and protecting public safety.

Putting the Proposed Reductions in Perspective. As noted earlier in this analysis, the 2008–09 budget plan proposes a $42 million reduction in the DOJ budget. The spending reduction is not allocated to specific programs in the department, consistent with an overall declared budget strategy of leaving out such specifics for “General Fund budgets not under the control of the administration.”

The 10 percent reduction is proposed to be applied against the workload budget for DOJ, as estimated by the Department of Finance. This is generally consistent with the administration’s approach for applying 10 percent reductions to a number of other state programs and departments. Unlike some other major criminal justice agency budgets, DOJ is not budgeted to receive significant General Fund increases for its programs in 2008–09. Thus, DOJ would realize a significant reduction in General Fund resources in the budget year if the Governor’s spending plan is adopted.

Whether DOJ should absorb a cut of this magnitude, or one that is larger or smaller in scale, is fundamentally a question relating to the Legislature’s own spending and program priorities. The administration has proposed that the department itself determine how this reduction would be achieved. While we believe the Legislature should consider the department’s advice when setting its funding level, the Legislature should also evaluate the impact of reductions on departmental services.

A budget reduction of this size could significantly affect DOJ’s operations, which fall primarily into two categories: legal representation of the state and its various departments, and law enforcement. A significant General Fund cut directed to DOJ’s legal representation could prompt the department to scale back its legal representation of other agencies. That, in turn, could potentially result in these other agencies incurring equal or greater costs to contract with private counsel for legal assistance. That makes it likely that any sizeable budget cut to DOJ would be borne mainly by its law enforcement programs.

Some Budget–Balancing Options Exist. With these factors in mind, we outline two possible approaches for the Legislature to consider in implementing a major reduction for DOJ. Our analysis suggests that these approaches would help the state to achieve its savings goals, while minimizing (but by no means eliminating) the impacts on its missions of representing the legal interests of the state and protecting public safety. These options are (1) eliminating the significant number of vacant positions at DOJ, and (2) charging state and local agencies for all, or part of, the cost of the laboratory services provided to them by DOJ. These options could result in state savings of $13 million in the budget year and as much as $54 million annually in future years. The fiscal effect of these options, which we discuss in more detail below, are summarized in Figure 1.

|

|

|

Figure 1

Options for Cost Savings in the

Department of Justice |

|

(In Millions) |

|

Options |

2008–09

Fiscal

Impact |

Potential

Future

Savings |

|

Eliminate some vacant positions |

$13.0 |

$13.0 |

|

Charge forensic laboratory fees |

— |

41.0 |

|

Totals |

$13.0 |

$54.0 |

|

|

To both enhance the Legislature’s oversight of state funding and reduce General Fund costs, we recommend the Legislature consider the option of eliminating a number of the vacant positions in the Department of Justice in order to achieve potential ongoing savings of as much as $13 million annually.

Background. When a department’s request for additional positions is approved in the budget process, the Legislature ordinarily appropriates nearly the full amount of the salaries and benefits, as well as funding for the supplies and office space (known as operating expenses and equipment, or OE&E) necessary for the positions. For most types of positions, the budget typically appropriates 95 percent of the cost of the personnel on the assumption that, in normal circumstances, the department will not be able to fill each position 100 percent of the year due to delays in hiring. If, however, hiring delays are longer or turnover is larger than expected, the department still maintains control of the money it does not use for the unfilled positions.

The way these funds are spent can vary by department but, ideally, the department should use the funds to further the mission for which they were appropriated. That might mean using the funds for additional equipment or paying the overtime expenses of staff required to do the work associated with the vacant positions. Unless specifically requested to do so, departments do not report to the Legislature on the manner in which they use these funds. Large and persistent numbers of staff vacancies in excess of the normal 5 percent salary savings, and large redirections of the funds appropriated to support those positions, can therefore weaken the Legislature’s oversight over the expenditure of these funds. (We discuss this statewide vacancy issue in the “Crosscutting Issues” section of the “General Government” chapter.)

DOJ Has a High Vacancy Rate. According to information provided by DOJ, the department as a whole reported a vacancy rate of 15 percent as of January 2008, representing about 863 positions. Based on our analysis, the total value of these positions, including salaries and benefits, but excluding OE&E, is approximately $57 million. Accounting for the normal 5 percent salary savings, this implies that there is in excess of $50 million in funds originally budgeted for employee salaries and benefits that is being used by the department on a discretionary basis for other purposes. At the time this analysis was prepared, and due to the complexity of this task, the department was unable to explain exactly how these funds are actually being used.

Within individual units of the department, the vacancy rates can be higher than the 15 percent cited above. This is particularly the case in units with positions that are difficult to fill, such as special agents or criminalists. For example, the Bureau of Narcotic Enforcement has a vacancy rate of nearly 28 percent, primarily due to more than 85 open special agent positions.

Targeted Reductions Could Create Savings. Our analysis of vacancy reports for the department’s 61 sections and bureaus indicates that 9 have both high vacancy rates and a large number of unfilled positions, as shown in Figure 2. These nine programs have an average vacancy rate of 20 percent and represent about 59 percent of the total vacancies in the department as a whole. The salary and benefits of these positions represent nearly $32 million.

|

|

|

Figure 2

Nine Department of Justice Sections

Have High Vacancy Rates |

|

As of January 2008 |

|

Division/Section/Bureau |

Vacant

Positions |

Total

Authorized

Positions |

Vacancy Rate |

|

Legal Secretariesa |

25.9 |

36.9 |

70% |

|

Bureau of Medi-Cal Fraud and Elder Abuse

|

34.0 |

204.0 |

17 |

|

California Bureau of Investigation |

23.0 |

129.5 |

18 |

|

Mission Support Branch |

36.1 |

122.1 |

30 |

|

Bureau of Narcotics Enforcement |

114.3 |

411.8 |

28 |

|

Bureau of Forensic Services |

79.0 |

405.0 |

20 |

|

Criminal Intelligence Bureau |

53.0 |

166.1 |

32 |

|

Hawkins Data Center Bureau |

48.0 |

336.3 |

14 |

|

Bureau of Criminal Identification and

Information |

94.5 |

708.0 |

13 |

|

Totals |

507.8 |

2,519.7 |

20% |

|

|

|

a Referred to by

the Department of Justice as Executive Unit. |

|

|

Our analysis identified 200 vacant positions that could be eliminated for annual General Fund savings of nearly $13 million. Our analysis focused on positions that have been historically difficult to fill, such as the special agent or criminalist positions discussed previously, as well as on sections that had more than a 10 percent vacancy rate. We assumed that only the salary and benefits portion of the original appropriations would be eliminated, leaving about $6 million originally budgeted along with these positions for OE&E for continued use by the department. This accounts for situations in which the department might be spending some of these OE&E funds on supplies for individuals in filled positions.

Some General Fund savings from vacancies might be achieved through conversion of positions to special fund support. The DOJ and some particular units within the department have many special fund sources of support. It might be possible to convert some positions now supported from the General Fund so that they are supported from special funds, making it possible in turn to further reduce the department’s General Fund appropriation. For example, the Bureau of Firearms has positions that are supported by the General Fund and other positions supported by the Dealers’ Record of Sale (DROS) Account, a special fund. Under our proposed approach, a vacant position in the bureau that is supported by DROS could be filled by transferring a bureau staff member now in a position supported by the General Fund. The newly vacant General Fund position could then be abolished to achieve General Fund savings.

Legislative Option. To both enhance the Legislature’s funding oversight and reduce General Fund expenditures, we recommend the Legislature consider eliminating a number of the vacant positions in DOJ in order to achieve potential ongoing savings of as much as $13 million annually, as shown in Figure 3. There are some key points the Legislature should consider under our proposed approach:

|

|

|

Figure 3

Elimination of Vacant Positions Would Create

Savings |

|

(Dollars in Thousands) |

|

Division/Section/Bureau |

Vacant Positions

Eliminated |

Savings |

|

Legal Secretariesa |

15 |

$891 |

|

Bureau of Medi-Cal Fraud and Elder Abuse |

10 |

756 |

|

California Bureau of Investigation |

10 |

756 |

|

Mission Support Branch |

20 |

1,218 |

|

Bureau of Narcotics Enforcement |

60 |

4,535 |

|

Bureau of Forensic Services |

30 |

2,190 |

|

Criminal Intelligence Bureau |

25 |

1,294 |

|

Hawkins Data Center Bureau |

15 |

914 |

|

Bureau

of Criminal Identification and Information |

20 |

907 |

|

Totals |

205 |

$13,461 |

|

|

|

a Referred to by

the Department of Justice as Executive Unit. |

|

|

- Ensure Special Fund Resources Are Sufficient. As noted earlier, some positions now supported from the General Fund could be shifted to special fund support in order to achieve General Fund savings. In such cases, the Legislature should ensure that the special fund has the resources to sustain the positions in the budget year and beyond.

- Consider Impact on DOJ Programs. In reducing funds associated with the vacant positions, the Legislature should direct the department to disclose its current use of the funds and the full programmatic impact of the elimination.

- Preserve Critical Positions. The Legislature should determine, after consulting with the department, whether any of the positions slated for elimination are so critical that their importance would outweigh the benefit of any potential General Fund savings.

The Legislature should consider the option of offsetting General Fund support for the Bureau of Forensic Services by requiring state and local agencies to pay for the laboratory services provided them by the bureau. Any fee structure should accommodate small agencies dealing with expensive and complex investigations, adequately protect the bureau financially, and be designed to effectively capture laboratory costs. This option could result in future savings that could reach $41 million annually.

Background. The DOJ’s Bureau of Forensic Services (BFS) operates 11 full–service criminalistic laboratories throughout the state. These laboratories provide analysis of various types of physical evidence and controlled substances, as well as analysis of materials found at crime scenes. The laboratories include a state DNA laboratory in Richmond (formerly located in Berkeley) that is responsible for processing evidence in criminal cases, as well as DNA samples taken from certain violent and sex offenders, and individuals convicted of other felonies, as specified in Proposition 69 (a 2004 initiative approved by statewide voters) for inclusion in its CalDNA database.

While the DOJ labs provide some services to state agencies, they primarily serve local law enforcement agencies in jurisdictions without their own crime labs. These local agencies are found in 46 out of 58 counties representing approximately 25 percent of the state’s population. The remaining jurisdictions either maintain their own labs or contract with other agencies for laboratory services.

Services undertaken by the DOJ crime labs for state and local agencies are generally provided at no charge. Two exceptions are that fees for both blood alcohol and some drug toxicology tests have been paid for since 1977 by local agencies from the collection of criminal penalties, such as those collected for driving under the influence convictions. The majority of BFS funding, however, is derived from the General Fund. The budget proposes that over $64 million in General Fund support be provided to BFS in the budget year, representing 70 percent of the $92 million budgeted for BFS from all fund sources.

Charging Lab Fees Would Result in Revenues and a Reduction in Workload. By directing BFS to charge local law enforcement agencies lab fees, the Legislature could reduce or eliminate General Fund support for BFS due to (1) the creation of new revenue and (2) a reduction that is likely to result in the number of cases processed by the labs.

Currently, local law enforcement agencies that rely on BFS have no incentive to ration their use of laboratory services, either by sending only their highest–priority cases to the state or by seeking other entities to assist with testing. There is evidence that the charging of fees can have a significant impact on the use by local agencies of BFS forensic services. For example, in 1992–93, when DOJ began to charge local agencies for the cost of processing blood alcohol tests, the number of such tests declined by 29 percent from the previous year. Many agencies started contracting with other providers who charged less than the state, thereby saving both the state and the agency money and reducing the caseload faced by state laboratories.

This strategy appears to be worth broader consideration, given the rising state General Fund costs for providing these services to counties. In 2005–06, BFS received a total of $41 million in General Fund support for its operations. As discussed above, these costs are projected to climb to $64 million by 2008–09, representing an increase of $24 million, or 57 percent, in just three years.

To the extent that the broader imposition of fees reduced DOJ laboratory workloads, it would also help the state to cope with its ongoing staffing difficulties in this unit. Seventy–nine of the 405 staff positions (many of them criminalists) authorized for BFS, or nearly 20 percent, are unfilled, according to information provided to us by the department.

Some Local Governments Provide Their Own Lab Services. We have proposed in the past that the Legislature authorize the charging of fees to other state and local agencies in order to offset DOJ forensic laboratory costs, most recently in the

Analysis of the 1999–00 Budget Bill (please see page D–133). Because developing physical evidence through laboratory analysis is part of local law enforcement responsibility for investigating and prosecuting crimes, we believe that the costs for these services should be borne by the counties and cities. Law enforcement agencies in 12 counties—county sheriffs, district attorneys, or city police—obtain laboratory services through the operation of their own laboratories or by relying on other agencies. It is also of note that the Federal Bureau of Investigation offers local law enforcement, free of charge, all forensic services in criminal matters, including expert witness testimony, unless the request for assistance originates in a laboratory that could handle the matter itself.

Potential Implementation Issues. If the Legislature were to move toward a fee–based system for financing BFS it would be important to address several key implementation issues:

- Mitigating Unusually High Costs for Complex Investigations. Some cases processed by the labs involve significant amounts of physical evidence and are, therefore, very expensive. If local agencies were billed for all costs in such cases, it could create a fiscal hardship for smaller agencies. Any proposed fee schedule would have to address such circumstances.

- Ensuring Financial Protection for Labs. If the labs are to be funded by reimbursements, they must be able to ensure full and timely payment of these fees by the state and local agencies for which they provide service. For example, BFS might be reimbursed based on the amount of service provided in the prior year, to prevent disagreement over the total amount owed.

- Establishing an Appropriate Fee Schedule. Determining the appropriate basis for allocating the costs of lab services can be challenging for some forensic services. As a result, it would be necessary to undertake a review of the services to determine the appropriate fees that should be charged for each service.

- Other State Agencies. The Legislature should adjust the budgets of any other state agencies to account for fees they would pay to BFS for laboratory services.

Legislative Option. We recommend that the Legislature consider the option of reducing General Fund support for DOJ by requiring that BFS charge state and local agencies for the forensic services they provide. If the Legislature moves in such a direction, we also recommend that any resulting fee structure effectively address the concerns we have raised. Resolving these issues could take some time and means that savings are not likely from this change until 2009–10. Eventually, however, depending mainly upon whether the Legislature wished to offset all or only part of BFS’s costs for forensic laboratory services with fees, the state could realize savings of as much as $41 million annually.

We find that a request by the Department of Justice for additional positions and funding for the Correctional Writs and Appeals section is only partially justified based on recent workload data provided by the department. (Reduce Item 0820–001–0001 by $1.8 million.)

Background. The Correctional Writs and Appeals section within DOJ is responsible for representing the state in cases in which prison inmates challenge various decisions made by the Governor, the Board of Parole Hearings, and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. The majority of the section’s workload involves so–called “habeas corpus” petitions in which inmates seek their release from prison or raise concerns about the adequacy of the conditions of the prison facilities in which they are confined. The section also handles other types of cases that arise while the inmate is incarcerated, such as petitions that deem inmates to be incapable of making health care decisions for themselves so that they can be administered drugs to improve their mental health.

Budget Proposal. The section has experienced an increase in workload since 2006. The 2007–08 budget plan authorized about 23 positions and about $3.6 million in additional General Fund support for the section to address these workload concerns. Based on the department’s projections that the section will continue to see increasing numbers of habeas corpus challenges, the 2008–09 budget plan requests an additional 26 positions for the section, including 13 Deputy Attorney General (DAG) positions, and $4.3 million from the General Fund.

The department has indicated in support of its budget request that staffing shortfalls have rendered the section unable to handle its current caseload, forcing its attorneys to seek delays in proceedings rather than directly arguing the inmates’ challenges in court. The primary reason for seeking these delays, according to the department, has been its inability to devote an adequate amount of time to each case. The request for 26 new positions, in addition to the total current authorized section staff of 47.5, is based on the department’s projection of an increased number of cases as well as a proposed increase in the average number of hours allotted to DAGs for each case they are assigned.

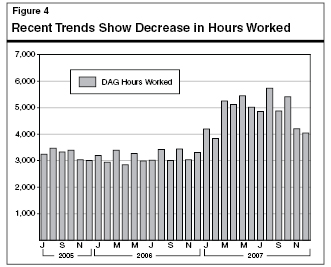

Data Indicate Recent Drop in Workload. As part of our review of the administration’s 2008–09 budget request, we requested that the department provide us with monthly data on the hours being worked by DAGs on the correctional writs and appeals workload. While the data provided by the department clearly indicate an increase in workload for the section since 2005–06, the most recent monthly data, as shown in Figure 4, show a drop in the number of hours being worked by DAGs. In August 2007, DAGs worked in excess of 5,700 hours. In each succeeding month, however, the total hours devoted to these cases has never exceeded 5,400, and the number was just over 4,000 by December 2007.

As a result, we estimate that the total number of hours of staffing that the section will require for this work is less than is projected in the 2008–09 budget proposal. Specifically, we project that the department would only require 6.5 additional DAGs, as opposed to the 13 requested. Our estimate takes into account the possibility that there will still be some growth in the caseload, and allows for an increase in the average hours that DAGs would work on these cases.

We would also note that, at the time our analysis was prepared, the department still had not filled 6.5 DAG positions—or the equivalent of one–half of the additional DAG positions authorized by the Legislature in the 2007–08 budget plan.

Analyst’s Recommendation. Based on our analysis of the section’s workload, we recommend that the Legislature only approve half of the requested DAG positions, and accordingly only approve half of the requested support positions. Thus, we recommend a reduction of $1.8 million and 13 positions in the department’s General Fund request for the budget year. If the department also filled the vacant positions it received in 2007–08 in the coming year, as well as the new positions we recommend be approved, it should have sufficient resources to respond to legal challenges filed by inmates.

We find that a request for $432,000 ($130,000 General Fund) in 2008–09 to support the initial planning costs to relocate the Department of Industrial Relations’ headquarters in 2009–10 is premature. The primary purpose of the move is to allow for the expansion of the Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) in the Hiram Johnson State Building in San Francisco. However, neither AOC nor DOJ has presented a plan or justified the need or the costs for the expansion.

We discuss issues surrounding a proposal for the AOC and DOJ to expand into the Department of Industrial Relations’ space in the “Department of Industrial Relations” section of the “General Government” chapter.

Return to Judicial and Criminal Justice Table of Contents, 2008-09 Budget AnalysisReturn to Full Table of Contents, 2008-09 Budget Analysis