Through this budget item, the state makes most of its contributions toward health and dental insurance premiums of about 220,000 retired state government and California State University (CSU) employees, their family members, and other eligible annuitants. The California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) administers the health benefit programs for state employees and retirees. Retirees receive a state contribution—the amount of which is set under a statutory formula—of up to 100 percent of monthly premium costs for a health maintenance organization or preferred provider organization plan. The CalPERS health plans require participants to pay for various costs—such as deductibles and prescription drug copayments—“out of pocket.”

The administration proposes expenditures of $1.3 billion for retiree benefits in this budget item—an increase of 13 percent over estimated 2007–08 spending levels. Although almost all of these costs are appropriated from the General Fund, the state recovers a portion of the costs—around 40 percent—from (1) special funds through pro rata charges and (2) federal funds through the statewide cost allocation plan.

In addition to the funds appropriated through this item, a portion of state contributions to active state employees’ health premiums goes to cover some health care costs for retirees (basically, those under age 65). This is because the same premiums are used for both active employees and these pre–Medicare retirees—even though retirees tend to have considerably higher medical costs. Accounting rules refer to these state payments as an “implicit subsidy,” which keeps premiums for pre–Medicare retirees lower than they would otherwise be. In 2007, actuaries estimated that the state’s implicit subsidy totaled about $300 million per year. In addition to the implicit subsidy, additional state contributions to the health expenses of some retirees living in rural California are paid through the Department of Personnel Administration (DPA) budget, and the university systems also make additional payments for their retirees’ benefits. Combining these amounts together, the state’s total costs for retiree health and dental benefits in 2008–09 would be in the range of $1.6 billion under the Governor’s budget. As described in the

nearby text box, the Governor has exempted retiree health and dental benefits from his proposed across–the–board spending reductions.

Governor Cites “Constitutional Restrictions,” But the Law Is Uncertain. The Governor exempted retiree health and dental benefits from his proposed across–the–board reductions, citing “constitutional restrictions.” State retiree health benefits are set in various statutes, which address the percentage of monthly California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) plan premium costs that the state pays for eligible annuitants. Some experts believe these payments are a constitutionally guaranteed benefit to retirees. To our knowledge, however, the ability of the state to reduce the percentage of premiums it pays for retirees has never been addressed by a court.

What Would Happen if the Legislature Was Able to Reduce This Budget Item? Reducing the state’s contributions to retirees’ health and dental plans probably would mean that annuitants (1) would have to pay more for their health and dental benefits and/or (2) would see the scope of their health or dental benefits—for example, the services covered or the quality of service offered by providers—diminished.

Does the Legislature Have Options to Reduce Costs? The Legislature could amend laws concerning the percentage of premiums the state pays for eligible retirees. In addition, the Legislature could attempt to contain costs without reducing the percentage of premiums paid by the state for retirees. The Legislature, for example, could direct the CalPERS’ Board of Administration to increase retirees’ out–of–pocket costs beginning in calendar–year 2009 or a future year. Retirees would pay a greater percentage of their overall treatment costs through these out–of–pocket expenses, and the rate of premium growth could be lowered. Paying the percentage of retirees’ premiums specified in current law then would be less costly for the state.

Any significant cost reduction measure affecting benefits of existing retirees would probably prompt a legal challenge. Such a challenge could affect the ability of the state to implement cost reductions in a timely manner. With negotiations between CalPERS

and health plans for 2009 benefits already underway, the Legislature

probably would need to pass a measure to reduce 2008–09 costs well

before July 1, 2008.

We withhold recommendation on the request for $1.3 billion for retiree health and dental costs pending the California Public Employees’ Retirement System’s determination of calendar–year 2009 health premiums in May or June. The administration’s initial estimates appear reasonable.

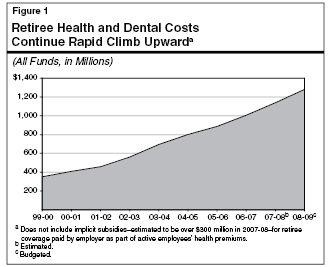

Costs Estimated to Continue Growing Rapidly. Under the administration’s budget estimate, the state’s costs to pay for statutory health and dental benefits for state retirees would continue their recent trend of rapid growth. Figure 1 shows the increases in this budget item since 1999–00—an average annual rate of 15.5 percent. The Governor’s budget assumes that the number of retirees eligible for benefits expands by over 3 percent in 2008–09 and that CalPERS adopts an average premium increase of 9.5 percent for its health plans in calendar–year 2009—for a total growth rate in the budget item of about 13 percent. The assumed average rate of premium growth is consistent with that used in the state’s actuarial valuation for retiree health and dental benefits, which was released by the State Controller’s Office (SCO) in 2007. The SCO’s assumptions about annual premium growth were developed in line with a model developed by CalPERS. In general, the administration’s estimates appear reasonable. Subsequent adjustments in the budget item will need to account for CalPERS’ actions later this year concerning 2009 plan premiums, as well as updated estimates of the state’s receipts of subsidies from the federal Medicare Part D program. (In 2007, the Legislature determined that these subsidies would be used to cover a small part of the state’s retiree health and dental costs and reduce General Fund costs accordingly.)

Withhold Recommendation. We withhold recommendation on the administration’s budget request pending CalPERS’

determination of calendar–year 2009 employee and retiree health plan

premiums in May or June.

The State Controller’s Office released the first actuarial valuation of California’s retiree health benefit program in 2007, which estimated the state’s unfunded liabilities for these benefits to be $48 billion. We concur with the conclusion reached by a commission appointed by legislative leaders and the Governor: The state should start addressing these liabilities. Otherwise, the liabilities will tend to grow over time—passing to tomorrow’s generations the cost of benefits earned by the public employees of today and yesterday.

What Are Unfunded Liabilities and Why Do They Matter? In our publication, California’s First Retiree Health Valuation: Questions and Answers, we discussed SCO’s release of the state’s first valuation of its other post–employment benefits (OPEBs)—principally consisting of retiree health benefits—in May 2007. The valuation—completed in accordance with new public–sector accounting rules—identified the state’s unfunded actuarial accrued liability (UAAL) for OPEBs to be $48 billion. In simplified terms, the UAAL is the amount of funds that would need to be set aside today, which, when combined with assumed future investment returns, would be sufficient to cover costs of the retiree benefits already earned to date by current and past employees.

Such large UAALs for retiree health benefits have emerged for California, other states, and many local governments because the benefits—unlike pensions—have never been funded in an actuarially sound manner. Instead of setting aside funds to cover the costs of retirement benefits as employees earn them each year—as the state and other governments have done for pension benefits for decades—most governments, including the state, fund retiree health benefits on a “pay–as–you–go” basis. This means benefits are funded only when they are due to the retirees, and no investment earnings are generated to cover a part of the costs. With health costs and the number of public retirees increasing, retiree health costs have grown rapidly over time, as shown in Figure 1. The result of the pay–as–you–go approach is that future generations pay for benefits earned by current and past public employees. This is a violation of a fundamental tenet of public finance: Transfers of costs from one generation to the next should be avoided.

Commission Strongly Recommends That the State Begin Addressing This Issue. Legislative leaders and the Governor appointed a 12–member commission—the Public Employee Post–Employment Benefits Commission (PEBC)—to identify accrued and unfunded OPEB liabilities of the state and local governments and to make recommendations on this topic. (See the nearby text box for more information on PEBC’s findings.) Consisting of members of both major political parties (including several leaders of public employee associations), PEBC unanimously recommended that the state and local governments “prefund” retiree health benefits—that is, set aside and invest funds as employees earn OPEB benefits, instead of funding those benefits on a pay–as–you–go basis. “As a policy,” the commission recommended, “prefunding OPEB benefits is just as important as prefunding pensions.” The “ultimate goal of a prefunding policy,” the commission said, “should be to achieve full funding.” (Full funding means the elimination of unfunded liabilities over time and the end of intergenerational transfers of benefit costs.) The commission specifically recommended that state policy makers “develop and make public a prefunding plan” and “establish prefunding as both a policy and budget priority.” These recommendations are consistent with those in our February 2006 publication, Retiree Health Care: A Growing Cost For Government.

Total Is Even Higher, as Some Governments Have Not Yet Had a Valuation. The Public Employee Post–Employment Benefits Commission (PEBC) was asked to estimate the amount of unfunded retiree health liabilities for the state and all local government entities in California. Based on surveys completed by officials at each level of government, PEBC estimated that the total unfunded retiree health liabilities for the state and local governments were at least $118 billion. The figure below displays PEBC’s estimates of how the $118 billion is distributed among the various types of governmental entities in the state. The actual amount exceeds $118 billion because some governmental entities did not respond to the PEBC survey, and some are not yet required to have completed actuarial valuations under the new public–sector accounting rules. For example, PEBC reported that 53 school districts with annual revenues of over $100 million did not respond to the survey, suggesting that the total amount of unfunded school district liabilities is much higher than listed.

|

|

|

Unfunded Retiree Health Liabilities |

|

(In Billions) |

|

|

|

|

State of California (including CSU) |

$47.9 |

|

Counties |

28.0 |

|

School districts |

15.9 |

|

UC |

11.5 |

|

Cities |

8.8 |

|

Special districts |

3.5 |

|

Community college districts |

2.5 |

|

Total |

$118.1 |

|

|

In addition to its own unfunded retiree health liability, the state plays a major role in funding several of the entities shown in the figure—such as the University of California, school districts, and community colleges. As such, the Legislature may face difficult choices in the future for how these governmental entities will pay rising retiree health benefit costs.

Funding the Liabilities Costs Much More Now, but Saves Money Over Time. According to data in SCO’s valuation, a full–funding strategy for OPEBs—like that advocated by PEBC and recommended by our office—would require the state to begin setting aside and investing an additional $1.2 billion (in current dollars) each year in a retiree health investment trust fund—similar to the pension funds invested by CalPERS. These estimates assume the state plans to eliminate its OPEB UAAL over 30 years, starts setting aside funds to do so immediately, and consistently funds the trust annually. The estimate—like all actuarial estimates—also assumes that certain assumptions are met each year concerning inflation (including growth of health care premiums) and gains in the stock market. Alternatively, the state could ramp up to the full funding amount of over $1.2 billion over several years and/or pay off its unfunded liabilities over more than 30 years. At some point in the future—likely 20 years from now or more—this strategy would prove to be less expensive than current practice for the state (assuming that future retirees continue to receive the same level of benefits specified in current law). This is because investment returns eventually would fund much or most of the annual benefit costs, relieving cost pressures on the state.

CalPERS’ 2008 Premium Increase May Help Reduce Liability Estimate. In June 2007—after SCO’s release of the valuation—CalPERS adopted calendar–year 2008 premium increases for its health plans that averaged about 6.3 percent. This was the lowest annual CalPERS premium increase in a decade. The lower–than–expected premium increase resulted in part from CalPERS’ decisions to increase copayments and maximum out–of–pocket charges and eliminate certain plan options for some members. The SCO’s valuation assumed that 2008 premium increases would average about 10 percent. The CalPERS staff has estimated that the lower 2008 premium increases may reduce the state’s unfunded liabilities by over $1 billion in the next valuation. Each year, the unfunded liability will increase or decrease depending on whether the actuaries’ assumptions about inflation, investment returns, and other factors are met.

Legislature Also Could Consider Benefit Changes to Address the Liabilities. Another alternative for the Legislature to address the state’s unfunded liabilities is to reduce benefits for retirees. This would reduce future retiree benefit costs, but could result in the need to increase some other categories of employee compensation (such as salaries or pension benefits) in order for the state to remain competitive in the labor market.

Administration Suggests a Good First Step to Address OPEB Liabilities. In the 2008–09 Governor’s Budget Summary (see page 241), the administration suggests an alternate approach for addressing OPEB liabilities. Instead of pursuing a full–funding strategy like that recommended by the commission and our office, the strategy discussed in the Governor’s Budget Summary seems to involve funding a part of the $1.2 billion (in current dollars) suggested by the SCO’s actuaries. As we understand the proposal, this would involve depositing to a retiree health trust account the amount each year estimated by actuaries to be the “normal cost” for OPEB benefits. (This is the amount that, if set aside and invested each year, would be sufficient—with accumulated investment earnings over time—to cover the future costs of the portion of retiree health benefits earned by employees in that single year.) As the administration describes it, this amount “would eliminate any new liability from being accrued.” Such a funding strategy would be a productive first step for the state in addressing its liabilities, if implemented by the Legislature in the coming years. The administration proposes no change in funding policy for 2008–09.

The Governor’s Budget Summary also discusses changing current benefit plans to allow greater flexibility and customization. The administration’s concept involves meeting directly with unions on the design of the benefit programs. Such a change would be significant, since, currently, the Legislature delegates most such decisions to CalPERS’ Board of Administration. Because agreements with unions are subject to legislative approval, the administration’s concept may increase legislative authority over the state’s employee and retiree benefit programs. We believe the concept is worthy of consideration.

Full Funding Strategy—Not the Administration’s—Is the One With the Greatest Benefit. In the Governor’s Budget Summary, a figure (see page 244) developed in consultation with actuaries claims that, under the administration’s suggested funding approach, state costs would be about the same 20 years from now as they would be under either the full–funding strategy or the pay–as–you–go funding strategy. The figure implies that the state’s financial condition would be the same over the long term no matter which funding strategy was chosen. We cannot validate the methods and assumptions used by the administration in developing this figure, nor do we agree that the state’s long–term fiscal condition will be the same in any event. Projections of this type that are based on actuarial calculations are prone to significant error based on the assumptions utilized concerning caseloads, inflation, investment returns, and other factors. The full–funding strategy is the approach that will reduce state costs the most over the long term. The PEBC, actuaries, and our office concur on this fundamental economic fact.

Return to General Government Table of Contents, 2008-09 Budget AnalysisReturn to Full Table of Contents, 2008-09 Budget Analysis