The Department of Public Health (DPH) delivers a broad range of public health programs. Some of these programs complement and support the activities of local health agencies in controlling environmental hazards, preventing and controlling disease, and providing health services to populations who have special needs. Others are solely state–operated programs, such as those that license health care facilities.

The Governor’s budget proposes about $2.6 billion from all funds for state operations and local assistance for DPH in the budget year, this is a decrease of about $208 million, or 7.3 percent, from the revised level of spending proposed for 2007–08. Total proposed local assistance expenditures are about $2.4 billion, of which $257.9 million is from the General Fund. The General Fund amount is 7.3 percent less ($20.1 million) than the revised current–year level of spending. This decrease is due to the proposed budget–balancing reductions (as discussed below).

The Governor’s proposed budget for public health programs includes the following significant changes:

- Budget–Balancing Reductions. The Governor’s budget plan includes a reduction of $31.7 million General Fund and 51.2 positions in 2008–09. A 10 percent reduction against the base workload budget for 2008–09 was applied to each program area funded by the General Fund except for programs related to food–borne illness and lease–revenue bond payments for the Richmond Laboratory. Of the 51.2 positions proposed to be eliminated, 19 were vacant as of January 10, 2008.

- Additional Funding for Licensing and Certification. The budget proposes $8.8 million in special funds and 68 positions to implement Chapter 896, Statues of 2006 (SB 1312, Alquist), which

- requires DPH to inspect all long–term care health facilities to ensure compliance with state laws and regulations.

- Upgrade of Richmond Laboratory. The budget includes $2.5 million General Fund to fund construction of enhancements to the Richmond Laboratory necessary to meet newly established federal standards.

- Implementation of Infections Control Program. The budget includes $1.7 million ($1.3 million General Fund) and 12 positions to implement an infection surveillance and prevention program pursuant to Chapter 526, Statutes of 2006 (SB 739, Speier). The Governor vetoed funding for this program in the 2007–08 Budget Act indicating in his veto message that his intent was to delay implementation by one year.

The state’s current process for administration and funding of over 30 public health programs at the local level is fragmented, inflexible, and fails to hold local health jurisdictions (LHJs) accountable for achieving results. This reduces the effectiveness of these programs because these services are not coordinated or integrated and LHJs cannot focus on meeting the overall goal of improving the public’s health. We recommend (1) the consolidation of certain public health programs into a block grant and (2) the enactment of legislation that would direct the Department of Public Health (DPH) to develop a model consolidated contract for these and other public health programs (which are not consolidated into the block grant). In addition, we recommend that outcome measures for these programs be developed and that DPH work with counties in using a consolidated contract.

The DPH’s 2008–09 budget includes about $2.4 billion ($258 million General Fund, $1.3 billion federal funds, and $635 million special funds) in local assistance for public health programs. This funding is allocated primarily to local health jurisdictions (LHJs) for a variety of purposes, such as emergency preparedness, infectious disease programs, chronic disease programs, county health services, and environmental health. (There are 61 LHJs, composed of the 58 counties and the cities of Berkeley, Long Beach, and Pasadena.) Community based organizations and universities also receive state local assistance funds for public health programs and research. Figure 1 lists the numerous categorical public health programs that provide state and federal support to LHJs.

|

|

|

Figure 1

Public Health

Categorical Programs |

|

Chronic Disease Prevention |

|

·

Children’s Dental Disease Prevention Program |

|

·

Fatal Child Abuse and Neglect Surveillance Program |

|

·

Kids’ Plates Program |

|

·

Preventative Health Care for Aging |

|

·

Tobacco Control Section |

|

Communicable/Infectious Diseases |

|

·

Immunization |

|

·

Sexually Transmitted Diseases |

|

·

Tuberculosis Control |

|

County Health Services |

|

·

Emergency Medical Services Appropriation (EMSA)

for California Healthcare for Indigents Program Counties |

|

·

EMSA for Rural Health Services Counties |

|

·

Refugee Programs |

|

·

State Public Health Subvention |

|

·

Vital Records |

|

Emergency Preparedness |

|

·

Bioterrorism Preparedness |

|

·

Hospital Preparedness |

|

Environmental Health |

|

·

Beach Water Sanitation |

|

·

Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program |

|

Family Health |

|

·

Adolescent Family Life Program |

|

·

Battered Women Shelter Program |

|

·

Black Infant Health |

|

·

Maternal, Child, and Adolescent Program |

|

·

Women, Infants, and Children Supplemental

Nutrition Program |

|

HIV/AIDS Programs |

|

·

AIDS Drug Assistance Program |

|

·

Bridge II-Minority AIDS Initiative |

|

·

Care Services Program |

|

·

Early Intervention Program |

|

·

HIV Counseling and Testing |

|

·

HIV Education and Prevention |

|

·

HIV Resistance Testing and Viral Load |

|

·

HIV/AIDS Case Management Program |

|

·

HIV/AIDS Surveillance and Special Epidemiology

Studies |

|

·

Housing Opportunities for People With AIDS

Program |

|

·

Neighborhood Interventions Geared to High-Risk

Testing |

|

|

The state funds public health programs in two primary ways—through categorical public health programs and the state’s realignment program. Categorical public health programs provide most of the funding, $2.4 billion in 2008–09 as mentioned above, while realignment provides an estimated $660 million to $825 million (an estimate we discuss in further detail below).

Many Categorical Public Health Programs. The state provides a combination of state and federal funds to LHJs for over 30 categorical programs. In general, these programs are targeted to specific populations with particular health needs. Funding for these programs is allocated in a variety of ways including on a formula basis and via a grant application process. The LHJs receiving these funds must comply with many and varied administrative requirements. For example, some programs require annual status reports, while others must submit data on a monthly basis. Generally, LHJs have little discretion over how the categorical funds can be used.

Realignment. The state enacted a major change, known as realignment, in the relationship between state and local governments in 1991. Realignment shifted responsibility for certain health programs from the state to LHJs and provided LHJs with a dedicated tax revenue from the sales tax and vehicle license fee to pay for these changes. In 2007–08, LHJs received $1.6 billion in realignment funds for health programs. It is unclear how much realignment funding LHJs use for public health purposes because LHJs are not required to report how these funds are spent. However, based on discussions with county associations it is generally estimated that between $660 million and $825 million (about 40 percent to 50 percent) of realignment funds are spent on public health programs and that the remainder is spent on inpatient and outpatient services for persons who are uninsured and are not eligible for other health care coverage, such as Medi–Cal and Healthy Families.

As previously discussed, LHJs have discretion over the use of realignment funds and are not required to report to the state how the funds are spent. In contrast, one of the primary purposes of categorical programs is to assure on a statewide basis that LHJs allocate resources for specific activities and services. However, this method of funding and administering each public health concern individually often leads to a public health system that is fragmented, inflexible, and not responsive to the overall health status of the community. Figure 2 summarizes the problems with California’s system of categorical public health programs.

|

|

|

Figure 2

Problems With California’s System of

Categorical Public Health Programs |

|

|

|

·

Numerous Categorical Programs Promotes

Fragmentation. Process

requirements of the categorical programs often shape local

responses rather than the needs of the community. |

|

·

State Rules Restrict Needed Local

Flexibility. Complex and detailed

program requirements in some programs reduce the flexibility

needed by local health jurisdictions (LHJs) to maximize the

impact of funds on improving the public’s health. |

|

·

Accountability Fails to Focus on Outcomes.

Current oversight efforts are intended to ensure accountability

for how funds are spent and how programs are structured. Few

programs are required to routinely collect good outcome data and

measure performance. |

|

·

Administrative Burden. State public

health programs separately enter into agreements with local

health jurisdictions. These agreements have different

definitions, formats, and requirements. Locals must enter into

agreements with each state program. |

|

|

Numerous Categorical Programs Promote Fragmentation. The current system of numerous categorical programs targeted to different populations promotes fragmentation of services at the local level. This fragmentation manifests itself in LHJs administering each program separately from other programs rather than in a coordinated or integrated fashion. County officials indicate that there is often limited communication among staff assigned to separate programs and limited ability to work together, even when the programs serve the same families and deal with related issues. This lack of coordination shifts the LHJ’s focus from one of improving the overall community’s health to focusing on a specific health concern.

State Rules Restrict Local Flexibility Needed to Be Effective and Efficient. The complex and detailed program requirements in categorical programs restrict the flexibility needed by LHJs to maximize the use of available funds. A recent evaluation of LHJs by the Health Officers Association of California, for example, indicated that categorical program funding restricts the ability of employees, especially public health nurses, to participate in education, training, and exercises aimed at building LHJs’ capacity to respond to a large disease outbreak. This is because staff must allocate their time according to the specific activity funded by a categorical program. In this case, categorical funding limits LHJs’ ability to adequately prepare for an emergency response situation.

Similarly, categorical funding can prevent LHJs from delivering services in the most effective manner. For example, one LHJ may have a disproportionate share of persons infected with certain sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and a very low percentage of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cases. However, the state’s separate allocation of funding for HIV and STD programs does not take this into consideration. Furthermore, a LHJ might find that STD testing is an effective means to prevent the spread of HIV because it addresses risky behavior that also leads to the spread of HIV. However, state HIV prevention funds cannot be used for such activities.

Categorical funding can also promote inefficiency. For example, five different health educators from five different programs may meet separately with individual pediatricians in a LHJ to discuss each program. However, it would be more efficient if LHJs had the flexibility to allow the health educators to coordinate their messages and visits to maximize the time available to both the educators and health care providers for delivering direct services.

Accountability Fails to Focus on Outcomes. Most categorical programs are bound by various state and/or federal restrictions on how the program must be structured or how funds may be used. For example, legislation enacted with the passage of Proposition 99 in November 1988 has very specific requirements for how LHJs must implement their tobacco cessation programs and has a specific percentage of funding that must be allocated to each LHJ. Consequently, current oversight efforts intended to ensure accountability focus on what activities LHJs fund and how services are delivered, instead of what the funding accomplishes (outcomes). Few programs are required to routinely collect outcome data and measure performance. This emphasis encourages local administrators to design programs that ensure compliance, rather than providing LHJs the freedom to assess the needs of the community and develop programs that would achieve desired results.

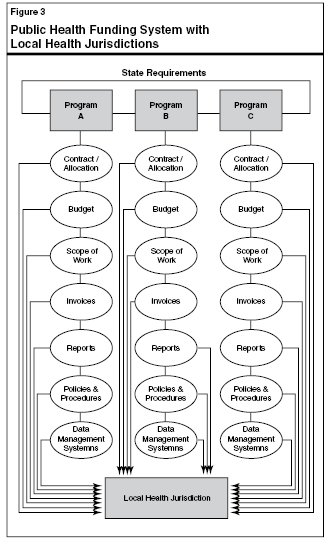

Categorical Programs Are an Administrative Burden. As shown in Figure 3, most state public health programs must separately enter into an agreement with each LHJ. Each program must (1) develop a contract or allocation agreement, (2) develop a budget, (3) define its scope of work, (4) include invoice requirements, (5) follow reporting requirements, (6) outline policies and procedures, and (7) develop a data collection system. Furthermore, each of these programs generally has different definitions of fiscal terms (such as what constitutes indirect costs, operating expenses, and travel) and accounting formats. Consequently, program staff at both the state and local level devote a significant amount of time to administrative activities, rather than the delivery of public health services.

As discussed above, the current approach to funding and administering distinct public health concerns leads to fragmentation and does not provide LHJs needed flexibility to address the overall health needs of the community. We find that there are benefits to reforming this system.

Local Flexibility Increases Effectiveness of LHJs. Various studies, including some by the Rand Corporation and the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), indicate that increasing local flexibility over funding allocations, administrative requirements, and program details allows LHJs to use funds in ways that meet community needs more efficiently and effectively. Providing local flexibility recognizes that health needs vary greatly from place to place, depending on geographic location, local industry (such as agriculture versus manufacturing), and the population served. Generally, public health professionals closest to the communities are in the best position to make detailed program decisions.

For example, a recent GAO study cited a flexible–funding demonstration project (conducted under a waiver with the federal government) by the State of Ohio’s child welfare department. Under this project, participating counties received a monthly allotment to fund child services free of any eligibility and allocation restrictions. During the first six years of the project, 11 of the 14 counties operated at below average costs, resulting in a total savings of $33 million.

In California, Placer County is piloting a program that integrates health

and human services programs and allows the county to have an integrated

contract with the state that consolidates the administrative requirements

for 16 state and federally funded health programs. (See the following box for more information on Placer County’s pilot program.)

Chapter 899, Statutes of 1996 (SB 1846, Leslie) and Chapter 268, Statutes of 2006 (AB 1859, Leslie) authorized Placer County, with the assistance of the appropriate state departments, to implement a pilot program for funding the delivery of health services through an integrated and comprehensive county health and human services system. The integrated program has been operational for five years and consolidates the administrative requirements for 16 state and federally funded health programs. These health programs include:

- California Children’s Services

- Child Health and Disability Prevention Program

- Health Care Program for Children in Foster Care

- Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program

- Immunization Outreach and Education

- Maternal and Child Health

- Adolescent Family Life Program

- Adolescent Sibling Pregnancy Prevention Program

- HIV/AIDS Counseling and Testing

- HIV/AIDS Education and Prevention

- HIV/AIDS Surveillance

- Oral Health, Miles of Smiles

- Preventative Health Care for the Aging

- Sexually Transmitted Disease Control

- Tobacco Control Program

- Women, Infants and Children Supplemental Nutrition Program

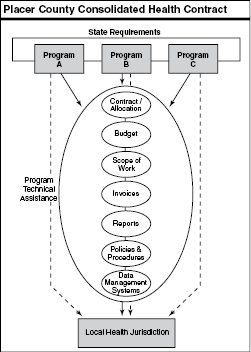

Prior to the pilot, these services were administered by separate programs within the county and each program had a separate contract with the state. In contrast, as shown in the figure, Placer County now has one consolidated contract with the state that includes a single scope of work, and a single, streamlined accounting, contracting, claiming, and reporting process for 16 public health programs administered

by the state Department of Health Services. The goals of this consolidated contract were to (1) create a simplified administrative framework for managing categorical funding for public health programs, (2) maximize the use of public health funds and staffing by reducing staff administrative duties and deploying staff more flexibly, (3) improve administrative efficiencies for reporting and accountability, and (4) track program outcomes more effectively.

These programs remain categorical in nature because the funding for these programs is not pooled or comingled. Consequently, funds allocated for any one of the programs cannot be expended for other purposes or programs.

An independent evaluation of the Placer County pilot found that having a consolidated contract increased staff’s flexibility to provide services to their clients. Under the pilot, a single health educator can work with a high–risk teenager on HIV prevention, nutrition, tobacco, dental health, and other issues, whereas, prior to the pilot, this teenager would be seen by multiple health educators even though the educators were teaching the same prevention strategies.

In addition, Placer County staff found that the consolidated contract permits greater county flexibility in meeting state and federal requirements because it reduces the administrative burden associated with administering 16 contracts and shifts the focus from being accountable for carrying out a series of individual categorical programs to being accountable for the overall health of the community. In addition, Placer County has achieved significant savings in accounting, reporting, and contracting costs. Specifically, Placer County estimates that it has reduced its accounting, reporting, and contracting workload by 1,600 hours annually. County staff also have more flexibility to provide better coordinated services to the community.

Other Counties Interested in Using a Consolidated Contract. Other LHJs are interested in using a consolidated contract for certain public health programs. For example, Alameda County was working with the Department of Health Services (DHS) on consolidating its health contracts prior to the split of DHS into DPH and the Department of Health Care Services. However, since the split there has been no movement on DPH’s part to engage again in these discussions. (Chapter 655, Statutes of 2004 [AB 1881, Berg], gave Alameda, Humboldt, and Mendocino Counties the authority to integrate their health and human services systems.)

As just discussed, Placer County has taken steps to simplify and consolidate aspects of its administration of public health programs. We find that in addition to consolidating the administrative requirements of these programs, the state could do more to consolidate programs and funding by using block grants.

Block grants consolidate funding for multiple categorical programs into one allocation. Reforming categorical public health programs by consolidating them into block grants with a single program structure and funding stream provides flexibility to deliver services in a way that best fits local needs.

What Are Block Grants? Block grants consolidate funding for multiple categorical programs into one allocation. A block grant tends to have fewer restrictions on how money is spent, in contrast to disparate funding streams each with different sets of requirements.

Block Grants Promote Integration of Services. Proponents of block grants argue that since block grants remove many specific requirements about how local governments must spend their money, they simplify the funding system and provide flexibility to deliver and integrate services in a way that best fits local needs. A unified set of goals and objectives put forth by a single agency frees LHJs to focus on the health care needs of the community. For example, a block grant that promotes disease prevention would allow LHJs to integrate disease prevention services that target similar at–risk populations.

Integration of Services Leads to Better Results. Integration of services can lead to better outcomes. For example, the California Department of Education’s Healthy Start Program provided grants to integrate service delivery for children and families. These services may include academic, youth development, family support, medical care, mental health care, and employment. (Prior to the implementation of this program, these services were not coordinated or integrated for a child or family.) One of the goals of this program is to streamline and integrate these services—from the child and family’s perspective—to provide more efficient and effective support to these families. The evaluations of this program indicate it was successful at arranging health care services for persons who might not have gotten them otherwise and that school violence decreased at schools with a Healthy Start Program.

Another example of how the integration of services leads to better outcomes is a demonstration project the state Office of AIDS (OA) at DPH is conducting for hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HIV testing. The OA found that HIV testing rates among injection drug users nearly doubled and the number of individuals returning to receive test results increased by 21 percent when an HIV test was offered in conjunction with an HCV test. This is because those individuals being tested were more interested in learning their HCV status than their HIV status. These results indicate that the integration of HIV testing with other services geared towards high–risk clients is likely to help prevent the spread of HIV and/or other diseases. As a result of this demonstration project, OA will distribute funds to LHJs to provide HCV tests as part of the HIV testing program.

Integration of Certain Prevention Services Can Improve Results. The Governor’s budget includes a total of about $40 million General Fund local assistance spread over a number of programs to prevent the spread of HIV, STDs, hepatitis, and tuberculosis (TB). Each of these programs separately allocates funding to LHJs. However, all of these prevention programs share the same general goal of preventing the spread of disease by educating persons about risky behaviors that lead to contraction of the disease. As illustrated in the example above, a person dealing with one of these issues is often engaged in risky behaviors that make them susceptible to multiple infections. Therefore, these programs often work with the same people, but currently there is little integration of the services they receive. As we discuss later, we find that the consolidation of these programs could lead to better outcomes.

Limitations to Consolidation. Given that a majority of the state’s public health programs are funded with a combination of federal and state special funds, there are limitations currently on the extent to which programs can be consolidated. This is because of federal funding requirements and restrictions on the use of state special funds. We note, however, that at the federal level, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are taking significant steps to increase the integration of categorical funding and programs. Nevertheless, steps can be taken to encourage the integration of certain programs and to reduce the administrative burden on LHJs that can interfere with achieving program objectives.

We recommend the enactment of legislation that would create a block grant for certain health prevention services. Specifically, we find that consolidating funding for disease prevention programs would provide flexibility to Local Heath Jurisdictions (LHJs) to deliver services that best meet the needs of their communities and provide an integrated approach to disease prevention. We also recommend the enactment of legislation that would direct the Department of Public Health to develop a model consolidated contract and outcome measures and work with LHJs that are interested in consolidation. This would lead to administrative efficiencies at the state and local level.

In order to reform the funding of public health programs we make two recommendations. First, we recommend the consolidation of certain disease prevention program funding into a block grant. Second, we recommend the consolidation of contracts with LHJs for public health programs. These recommendations are discussed in more detail below.

Consolidate Funding for Certain Prevention Services Into a Block Grant. We recommend that the Legislature create a disease prevention block grant. This grant would include about $40 million in General Fund support that is allocated for the prevention of HIV, STDs, hepatitis prevention (nonperinatal), and TB. Consolidating these programs would maximize local control for LHJs in order to best meet community needs, and if structured well, shifts the focus from process to results. The LHJs would be allowed to shift funding among these prevention programs in response to the needs of a particular community. We find that combining these prevention–funding streams has the potential to lead to better program integration and as a result, a reduction in the spread of disease and the improvement of the overall health of the community. Furthermore, to help evaluate the effectiveness of this funding, the block grant would require the tracking of specific outcome measures to evaluate the LHJs efforts in preventing these diseases.

Direct DPH to Develop a Model Consolidated Contract and Outcome Measures. We recommend the enactment of legislation that would direct DPH to develop a consolidated contract model building on its work with Placer County. The department should also be required to work with LHJs who are interested in using a consolidated contract. A consolidated contract could lead to long–term administrative efficiencies at both the state and local level and a significant reduction in costs associated with accounting, reporting, and contracting. These administrative savings would more than offset the short–term state cost to refine the contract model and work with LHJs. In addition, to help ensure that the focus is on achieving positive outcomes, the state would design specific outcome measures to evaluate the effectiveness of LHJs. Based on the experience of those counties choosing to consolidate their contracts, the Legislature may wish to consider requiring all LHJs to use a consolidated contract in the future.

The state’s process of administering and funding categorical public health programs leads to a system that is fragmented, inflexible, and not accountable to the overall health status of the state. We recommend the creation of a prevention block grant and the enactment of legislation that would direct DPH to develop a model consolidated contract, outcome measures, and work with counties interested in using this approach.

The Legislature relies on departments to promulgate regulations to implement laws. The Department of Public Health is slow to promulgate such regulations and consequently, state laws are not being enforced or applied consistently across the state. We recommend the department report at budget hearings on the status of the development and promulgation of unissued regulations.

Every year the Legislature passes new laws. For many of these laws, the administering department must promulgate regulations in order to implement the new law’s requirements. Regulations often provide the details necessary to implement the law so that it can be applied consistently across the state.

Department Behind in Promulgating Regulations. Our review found that DPH is behind in its development and promulgation of regulations. This often means that state laws are not being implemented or enforced. For example, a superior court judge recently tossed out a lawsuit alleging understaffing in numerous Sacramento–area nursing homes because the state had failed to promulgate regulations relating to minimum–staffing requirements thereby failing to provide a standard the courts could use to determine if the nursing homes complied with state law.

Department Unresponsive to Requests for Information. Our office requested a list of pending regulations from DPH in March 2007. We continued to follow–up on this request and almost a year later have not received any information from the department. For example, we specifically asked the department about the status of regulations to implement Chapter 742, Statutes of 1997 (AB 186, V. Brown), a law that has been on the books for over ten years. This law requires the Department of Health Services (now DPH) to adopt written standards to establish sterilization, sanitation, and safety procedures for persons engaged in the business of tattooing, body piercing, or permanent cosmetics. The state’s failure to promulgate regulations on this issue has lead to individual local health departments passing their own ordinances. This can result in a state law being implemented differently across the state or not being implemented and enforced at all.

Analyst’s Recommendation. We recommend that the department report at budget hearings on the status of regulations which it is required to promulgate in order to carry out laws passed by the Legislature. Specifically, the department should identify what regulations are under development, what steps the department is taking to promulgate the regulations, and how the issues are being regulated in the interim. With this information, the Legislature will be aware of what laws have not been implemented and it can direct the department’s priorities in promulgating regulations to ensure the public’s health and safety are protected.

The 2008–09 budget plan proposes $127,000 General Fund and one position to ensure that the state’s sexual health education programs are comprehensive and not based on abstinence–only. Since this is a new activity and the program has not yet begun, we believe that these funds would be best used to offset the cuts the Governor is proposing to ongoing programs that provide direct services for sexual health needs. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature delay implementation of Chapter 602, Statutes of 2007 (AB 629, Brownley), and redirect the proposed increase in funding to offset budget–balancing reductions for teen pregnancy and sexual health direct services. (Decrease Item 4265–011–0001 by $127,000. Increase Item 4265–111–0001 by $127,000.)

Governor’s Proposal. The budget includes $127,000 General Fund and one position to implement Chapter 602, Statutes of 2007 (AB 629, Brownley), which requires that sexual health education programs funded or administered by the state be comprehensive and not based on abstinence–only. This position would monitor the state’s sexual health education programs to ensure that they meet the requirements of Chapter 602.

The Governor’s budget also includes a reduction of about $365,000 General Fund for direct teen pregnancy prevention and sexual health services. The administration estimates that because of this reduction approximately 38,000 teens would not receive pregnancy prevention and sexual health services.

Analyst’s Recommendation. We recommend the Legislature delay implementation of Chapter 602 and redirect proposed funding for staff to offset budget–balancing reductions the Governor proposes for direct teen pregnancy and sexual health services. Since this is a new program and has not yet started, we believe that providing direct services to 38,000 teens is more likely to be cost–beneficial.

Return to Health and Social Services Table of Contents, 2008-09 Budget AnalysisReturn to Full Table of Contents, 2008-09 Budget Analysis