2009-10 Budget Analysis Series: Proposition 98 Education Programs

Largely as a result of the state’s recent difficulties balancing the budget, it has also experienced difficulties managing its cash flow situation. To address these cash problems, the state deferred several large payments in 2008–09, with the largest deferrals coming from Proposition 98 payments. Given the state’s reliance on Proposition 98 deferrals and concern about their impact on districts, the Legislature directed our office to convene a work group to examine K–14 cash management more closely. Below, we describe the distribution of existing Proposition 98 payments and discuss the strategies local agencies use to ensure they have sufficient cash available to make major payments. We then identify areas of misalignment between cash payments and programmatic needs under the current system and develop two new better aligned payment systems. Although we believe the state should begin implementing a more rational payment system as soon as possible, we recognize a new system might take more than one year to implement fully. At the same time, the state might continue to need extraordinary short–term cash solutions. Thus, we also provide the Legislature with a few guidelines for making deferrals under the existing system that would help the state while minimizing the negative impact on K–14 entities.

State Payments

The distribution of existing Proposition 98 payments is notably different for K–12 education compared to the CCC and CCD. Whereas payments for CCC and CCD are rather evenly distributed throughout the fiscal year, K–12 payments are more erratic. (The box below briefly describes the distribution of federal funds. We do not cover these payments in detail because the federal government currently has separate efforts underway to better align federal disbursements with districts’ programmatic needs.)

|

Federal K–12 Payments Similar to “Other” Categorical Payment. Federal K–12 payments are made to the California Department of Education (CDE), which then transfers the appropriate amounts to each school district. Most of these payments are made in the same manner as “other categorical” payments—each program is paid out in two or three installments throughout the year. Payments per month vary, but large payments typically are made in August, November, April, and June. The department indicates that it is in the process of better aligning its disbursements of federal funds with districts’ programmatic needs. The federal government has directed states to move toward a virtually instantaneous “pull down” system, whereby districts would receive federal funds within days of incurring expenses. Though this is the federal government’s objective, CDE indicates that it is trying to move to a system of quarterly allocations as a first step. Given these separate efforts, we do not integrate federal payments into the new payment systems we describe later in this section. Federal California Community Colleges (CCC) and Child Care and Development (CCD) Payments Already Aligned With State Payment System. Community colleges receive most of their federal funding for services to individuals participating in the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program and from Carl Perkins vocational grants. Most federal funds for CCC’s CalWORKs program are allocated on the CCC monthly apportionment schedule. The Carl Perkins vocational grants are distributed on a quarterly basis. Federal child care payments are made in the same manner as state payments, with one–quarter of funds paid in July, and the remainder evenly distributed between October and June. |

Three K–12 Payment Systems. K–12 school districts receive Proposition 98 funding from a combination of state General Fund dollars and local property tax revenues ($46 billion proposed for 2009–10). Statewide, approximately three–quarters of Proposition 98 payments to school districts are made from the state General Fund. State payments to school districts are distributed by the CDE using one of three payment systems.

- Principal Apportionment. Approximately 80 percent of state payments to school districts are distributed through the principal apportionment system. Under this system, school districts receive payments for 21 programs, with funding distributed according to monthly payment schedules set by law. As shown in Figure 20, the apportionment schedule for most school districts is generally uniform throughout the year, but has smaller payments in July and larger payments in August and February. (Current law also authorizes two alternative payment schedules that provide larger payments in the beginning of the fiscal year. These schedules are used for small school districts that receive a large percentage of their funding from property taxes and, therefore, are more cash poor at the beginning of the fiscal year.) State revenue limit payments, which provide general purpose funding for districts, represent about 80 percent of the principal apportionment payment. In addition, current law requires that 15 specified categorical programs be paid using the principal apportionment system. At its discretion, CDE makes payments for five other categorical programs through the principal apportionment.

- Special Purpose Apportionments. The state distributes approximately 5 percent of state funds to school districts through the special purpose apportionment system, which provides ten equal monthly payments from September to June. The special purpose apportionment currently provides payments for two categorical programs—EIA and Home–to–School Transportation.

- Other Categorical Payments. School districts also receive payments for more than 20 other K–12 categorical programs throughout the year at the discretion of CDE. Approximately 15 percent of state payments to school districts are made in this manner. Based on our discussions with the department, payments are made with the goal of providing as much money as possible early in the fiscal year. The department, however, takes into consideration its own staff availability and data constraints. To limit the amount of workload, only two or three payments are made annually for each applicable program. The CDE is also restricted by the specific data required to calculate districts’ allotments (such as current–year student enrollment or first–year teacher counts). Payments are made later in the year for programs that rely on data not readily available at the beginning of the fiscal year. The exact payment schedule for each applicable program varies from year to year, but generally provides large payments to districts in September, October, January, and February. (A tentative cash flow schedule is available on the department’s Web site so districts know when funding for certain programs is expected to be paid.) Among the large categorical programs distributed in this way are K–3 Class Size Reduction (CSR), the Targeted Instructional Improvement Block Grant, and the School and Library Improvement Block Grant.

Figure 20

Payment Schedules for Major K-14 Programs |

General Fund |

|

K-12 Principal

Apportionment |

CCCa

Apportionment |

Child Care |

July |

6.0% |

8.0% |

25.0% |

August |

12.0 |

8.0 |

— |

September |

8.0 |

12.0 |

— |

October |

8.0 |

10.0 |

8.3 |

November |

8.0 |

9.0 |

8.3 |

December |

8.0 |

5.0 |

8.3 |

January |

8.0 |

8.0 |

8.3 |

February |

14.0 |

8.0 |

8.3 |

March |

7.0 |

8.0 |

8.3 |

April |

7.0 |

8.0 |

8.3 |

May |

7.0 |

8.0c |

8.3 |

June |

7.0b |

8.0c |

8.3 |

Totals |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

|

a California Community Colleges. |

b Under current law, the entire K-12 principal apportionment payment for June is made in the

first week of July. |

c Under current law, a portion of the May and June CCC apportionments are paid in July. |

One Primary CCC Payment System. As with K–12 education, community colleges also receive Proposition 98 funding from a combination of state General Fund dollars and local property tax revenues ($6.5 billion proposed for 2009–10). Statewide, approximately two–thirds of Proposition 98 community college payments are from the General Fund. These payments are made to community college districts by the CCC Chancellor’s Office.

- Apportionments and Most CCC Categorical Payments Are Distributed Using Set Schedule. Community college regulations establish the percentage of apportionment funds that are allocated to districts every month. As shown in Figure 20, districts receive about 8 percent of the total each month, with the highest percentage (12 percent) coming in September and the lowest (5 percent) in December (when districts receive their property tax revenues). Payments for the latter half of the fiscal year are generally evenly distributed. Of CCC’s 22 categorical programs, 17 are distributed on this monthly apportionment schedule. Payments for the remaining five programs are disbursed fully or partially through an invoice or direct billing process (based on specific contractual terms or as costs are actually incurred).

One Primary CCD Payment System. Child care providers also receive Proposition 98 funding from the state. (They do not receive any local property tax revenues.) Aside from the beginning of the year, CCD payments are spread evenly throughout the year. In July (or whenever a budget is enacted), CDE provides a 25 percent payment to providers intended as an advance for expenses incurred in the first three months of the fiscal year. Thereafter, nine equal payments are made from October through June. All 11 child care programs receive state payments using this disbursement system.

Adjustments Throughout Year as Better Data Become Available. State funding for most K–14 programs are based on current–year estimates of numerous factors, including K–12 attendance and community college enrollment. Because estimates of these numbers are constantly changing, CDE and the CCC Chancellor’s Office must make corrections throughout the year to ensure districts are receiving the appropriate amount of funding.

Principal Apportionment Adjustments. School districts and community colleges rely on a specific process for adjusting principal apportionment payments. In July (or whenever a budget is enacted), CDE and the Chancellor’s Office determine monthly allocations to districts from July through January based on the “advance.” The advance is based on prior–year funding levels adjusted by the estimated statewide change in K–12 average daily attendance (ADA)/CCC enrollment growth, any applicable COLA, local property tax estimates, and CCC fee revenue estimates. In February, CDE and the Chancellor’s Office use actual ADA and enrollment information from the fall, as well as revised property tax estimates, to recalculate monthly payments for each district. These revised estimates, known as the “first principal apportionment” (or P–1), are used to make payments from February through May. The “second principal apportionment” (or P–2) uses revised attendance/enrollment information up to April 15 and is used for the June payment for each district. The largest K–12 programs generally receive funding based on attendance estimates up to April 15, so after receiving the June payment their total allocations are not typically further adjusted. Some K–12 programs and all community college programs, however, receive funding based on annual data up to June 30. A final set of adjustments are made for these programs after the close of the fiscal year when actual enrollment and revenue numbers are known.

Similar But Less Complicated CCD Adjustment Process. Child care programs have a similar, but less complex, process for making adjustments to initial payments. The CDE adjusts total payments to each provider after reviewing quarterly attendance information. Depending on the accuracy of the initial estimates, payments are increased or decreased to ensure providers receive the appropriate reimbursement.

Property Tax Payments

Statewide, property tax revenues account for approximately one–fourth of Proposition 98 funding for K–12 school districts and community college districts ($15.4 billion estimated in 2009–10). Each school and community college district uses property tax revenues to fund a portion of revenue limits/apportionments (the remainder of support comes from the state General Fund). The share of funding that a district receives from property taxes varies widely throughout the state, depending on the value of assessed property in the district and the portion of property tax revenues that are provided to school districts (counties, cities, and other local agencies also receive a share of property tax revenues). According to state law, property owners must pay their property taxes to the county in two installments, due on December 10 and April 10. Payments are collected by counties and transferred to school districts shortly thereafter. As a result of the property tax due dates, districts receive virtually no property tax revenues until the middle of the fiscal year.

Dealing With District Cash Shortages

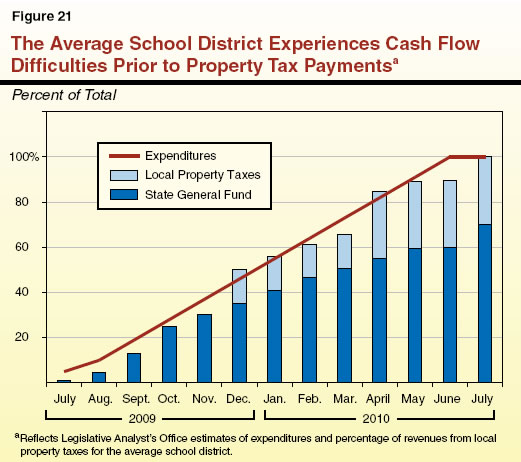

School and community college districts generally face cash flow shortages at certain times in the fiscal year, primarily as a result of the property tax payment schedule. Cash shortages can be particularly severe for districts that receive a large share of their revenues from property taxes. As Figure 21 shows, before December and April, even the average school district has spent more than it has received in state and local revenues. These cash flow problems can be further exacerbated by deferrals of state payments. Below, we discuss the various ways districts go about meeting their short–term cash needs.

Internal Borrowing. If a district does not have sufficient cash available to meet its obligations, the simplest and least costly option for districts is to borrow internally from other district accounts or funds. Districts, for example, can use categorical funding for a different purpose on a temporary basis if it is experiencing a cash shortage in another program. In addition, districts can use funds from other restricted funds, such as those for facilities projects. Current law requires that no more than 75 percent of any restricted fund be loaned at any one time, and the loan must be repaid by June 30 if it was taken more than four months prior to the end of the fiscal year. If the loan is made within four months of the end of the fiscal year, then the money does not have to be repaid until the end of the subsequent fiscal year. This is the most common option used by districts to address cash flow shortages.

Borrowing From COEs. If a school or college district has insufficient cash available in other district funds to meet its expenses, state law allows them to borrow from their COE. The ability of a COE to lend money to a district depends on the COE’s cash situation. Given COEs have the same cash issues related to late–arriving property tax payments, districts very rarely request loans from COEs.

Borrowing From County Treasurer. Both school and community college districts can obtain a loan from the county treasurer. The California Constitution requires the county treasurer to loan to a district, as long as the loan is no more than 85 percent of the direct taxes levied by the county on behalf of the district (such as property taxes). The district must pay the loan back with the first new revenues received by the district, before any other payments are made. Due to these restrictions, districts rarely use this option as a cash management tool.

Issuing Tax and Revenue Anticipation Notes (TRANs). School and community college districts also have the option of borrowing from the private sector by issuing TRANs to access cash on a short–term basis. The TRANs are purchased by investors and must be paid back by districts (with interest) within a short period of time, typically by the end of the fiscal year. In determining how much cash to access through TRANs, school districts typically determine their most “cash–poor” month and borrow enough money to ensure the district can pay all its obligations in that month. In addition to paying interest for the borrowed cash, districts also incur some upfront costs for the cost of issuing the notes. The number of districts that issue TRANs varies from year to year, but districts use this option more frequently than borrowing from COEs or the county treasurer.

Pooling to Issue TRANs. To reduce the cost of issuing TRANs, most districts pool their efforts to access funds from the private market. The California School Boards Association (CSBA) and the Community College League of California (which represents the system’s trustees and chief executive officers) both sponsor pools for districts that are interested in issuing TRANs. These organizations gather the interested parties and issue one set of TRANs on behalf of all districts. The CSBA’s pool currently includes 164 districts. The League’s pool currently includes 11 community colleges. In addition, several COEs, including Los Angeles, have created pools for districts in their region. In total, approximately one–fifth of districts participated in a TRANs pool in 2008–09.

Dealing With State Cash Shortages

Much like school and community college districts, the state also faces cash flow shortages during certain times of the year. The state generally is most cash poor in the months of October and March, prior to the issuance of private cash–flow borrowing in November and the receipt of large income tax payments in April. Unlike districts, the state has the option of deferring certain local assistance payments to help manage its cash flow.

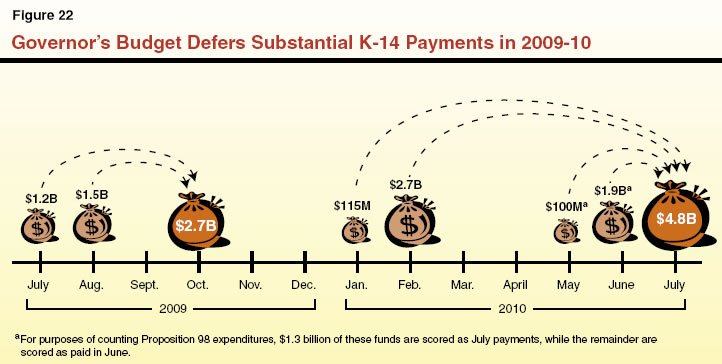

Governor’s Budget Includes Several K–14 Deferrals. For 2009–10, the Governor’s budget includes several proposals to defer K–14 payments, thereby achieving state cash relief in critical cash–poor months. Less than 10 percent of the deferrals would affect community colleges, with the remainder affecting K–12 schools. As shown in Figure 22, the Governor would defer $1.2 billion in July payments and $1.5 billion in August payments until October. He also would defer $115 million in January payments and $2.7 billion in February payments until July. These deferrals are in addition to already existing $2 billion deferrals from May and June to July that were created in earlier years.

Problems With the Current State Payment System

We have no significant issues with the method in which child care and community college payments are made. Both receive funding through a simple process that consolidates several programs into one payment system. As discussed below, we do, however, have concerns with the payment structure used for K–12 schools. In addition, we see no clear rationale for distributing K–12 and community college payments differently.

Lacks Transparency and Predictability. The multiple existing K–12 payment systems make determining how much funding a school district will receive each month difficult. As noted, the state operates both a “principal” and “special purpose” apportionment system as well as an ever–changing payment system for many categorical programs. This complexity can make it difficult for school districts to plan their cash flows.

No Clear Rationale or Coherence in Current Structure. None of the finance experts in the K–14 cash management work group that we convened could explain the rationale for having three separate K–12 payment systems or the rationale for why each system currently worked as it did. For example, the state typically pays 14 percent of principal apportionment and a large portion of funding for the K–3 CSR program in February. There is, however, no clear justification for why February payments are so much larger than payments in other months. Similarly, there is no clear policy rationale for the manner in which categorical payments are made. Most categorical programs are paid in two or three large sums, even though most of these programs require districts to incur costs evenly throughout the year. The specific idiosyncrasies of each payment system result in a disconnected system that is not designed to provide a rational, well–planned method of distributing payments.

No Rationale for Treating School and Community College Districts Differently. School and community college districts experience the same types of problems in dealing with cash shortages. Although the magnitude of the problem varies in each district, both school and college districts must manage their cash situation to ensure sufficient funds are available in the months prior to receiving property tax payments. Because the issue is not fundamentally different for school and college districts, we see no analytical reason why payment schedules should be different for the two segments.

Build a More Streamlined System That Aligns Payments With Costs

Because of its lack of transparency, predictability, and coherence, we recommend making major changes to the current K–12 payment structure to provide a simpler, more rational system for providing school districts with funding in line with expenses.

Create One Payment Schedule. Rather than have several different schedules for distributing state payments, we recommend that all payments go out under the principal apportionment system. This would provide a more predictable payment schedule and allow the state to distribute funding uniformly throughout the year.

Align Payment Schedule With Expenditures. As with any rational payment system, we recommend that the K–12 payment schedule be aligned with district expenditures. Based on reviews of district–level expenditure data collected as part of the cash management work group, school district expenditures tend to be evenly spread throughout the year, with the exception July and August. (The summer months have lower teacher payroll costs.) Below, we provide two possible payment schedules that would provide funding in line with expenditures. The first would disburse state payments at the same rate school expenses are incurred. The second would disburse state payments earlier in the year so that total (state and local) revenues are aligned with expenditures.

“5–5–9” Approach. Under this approach, the state would provide 5 percent of state payments in July and August, with 9 percent payments for the remainder of the year. This schedule would provide somewhat less cash in the first two months of the year, when districts incur lower costs, and provide even payments thereafter (consistent with school district expenditure patterns). Although this payment schedule would distribute state payments in a manner consistent with district expenditures, it would not provide additional resources for school districts to manage cash flow prior to property tax payments. Finding short–term cash solutions prior to the receipt of property tax payments would remain the responsibility of the school district.

“10–10” Approach. This option would provide 10 percent payments in every month except for December and April, the months when districts receive property tax payments. There would be no state payments in these two months. Because of the larger payments in the beginning of the year, this schedule would provide districts with additional resources to deal with their cash–poor months. As a result of the larger payments in early months, the state would need to have additional cash available to make these payments early in the year.

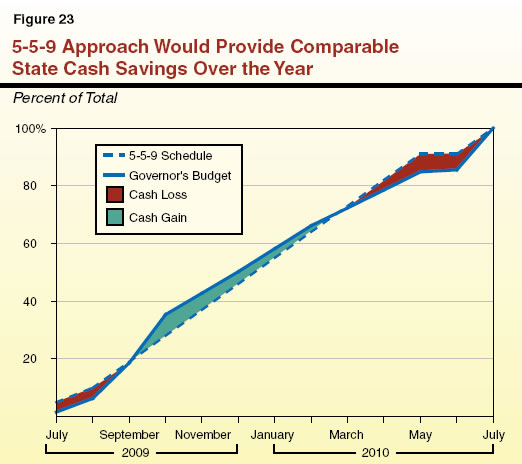

Different Effects on State Cash Flow. These two options would have significantly different effects on the state’s cash flow. As shown in Figure 23, compared to the Governor’s proposed payment distribution (including all his proposed deferrals), the 5–5–9 approach would result in cash loss to the state in the first two and last few months of the fiscal year, but would provide a cash gain from September to February. Despite these differences, the 5–5–9 approach would generally put the state in a comparable cash position as the administration’s plan. The 10–10 approach, however, would provide a cash loss to the state every month except for December and April. As a result, the 10–10 approach would generally put the state in a less favorable cash position relative to the administration’s plan.

Apply 5–5–9 Approach to K–12 and CCC Payments. The 5–5–9 approach aligns state payments with district costs, at least partly eliminates the need for deferrals, and treats all districts consistently. For these reasons, we recommend the state convert to a 5–5–9 system over the next few years. Because we see no strong rationale for using different payment systems for school districts and community colleges, we recommend applying the 5–5–9 system to both segments. This would only require modest changes to CCC payments.

Given Great Variation Across Districts, 5–5–9 Approach Is Reasonable Statewide Policy. Under a 5–5–9 system, we recognize many school and college districts would lose the benefit they now receive from somewhat frontloaded state payments as they await property tax allocations. Nonetheless, we believe it is a reasonable statewide policy given districts across the state vary greatly in terms of their reliance on property tax revenues. That is, unless the state provides unique payment schedules for each school district, it cannot fully address the property tax situation for all school districts. Furthermore, many districts have well–established tools for addressing cash flow issues related to property tax payments, and districts that currently do not use such tools could access them if needed.

2009–10 May Be a Transition Year. Transitioning from the current system to a one–payment–schedule system would entail near–term implementation challenges. First, the new system would require administrative changes at CDE. In particular, the transition to a new system would require changes in organization, staffing, and information technology systems. The Legislature likely also would need to change some of the data requirements underlying certain categorical payments. As a result, CDE may not be able to fully implement the new system for the start of the 2009–10 fiscal year. Second, the state’s cash situation could be so severe in 2009–10 and 2010–11 that additional one–time deferrals could be needed to help the state meet all of its cash obligations.

Provide Early Notice. With sufficient time, school districts are capable of adapting to most situations and securing sufficient cash to meet their obligations. Adapting to a changing cash situation, however, can be difficult without sufficient notice—particularly if a deferral would affect districts in cash–poor months. Many of the actions school districts must take to secure cash require planning and cannot occur immediately. For example, districts would need to provide advance notice to counties if they were to request a loan. Due to the cost of issuance and time required to sell notes, issuing TRANs also can require several months of planning. We recommend, therefore, that any deferrals be declared as soon as possible to ensure districts can properly plan for their cash needs in the upcoming fiscal year.

Return to Proposition 98 Education Programs Table of Contents,

2009-10 Budget Analysis Series

Return to Full Table of Contents,

2009-10 Budget Analysis Series