December 22, 2011

Pursuant to Elections Code Section 9005, we have reviewed the

proposed constitutional initiative concerning public employee pensions

(A.G. File No. 11‑0064, Amdt. #1S).

Background

Existing Public Employee Pensions.

California governments generally offer comprehensive pension benefits to

their employees, which are funded from public employer and public

employee contributions, as well as investment earnings generated from

those contributions. Some governments also contribute to retiree health

benefits for their former employees.

Types of Retirement Plans. In general,

California public employees are enrolled in defined benefit pension

plans, which provide them with a specified benefit—generally based on

their salary levels near the end of their career, their number of years

of service, and the type of job they had while in public employment.

This is called a defined benefit pension plan, and public employees

generally are obligated to contribute only a fixed amount—as a

percentage of their pay each month—to these plans.

Public employers and employees generally are required to contribute

the amount estimated by actuaries as the “normal cost” for plans each

year. Normal costs are the amounts estimated to be necessary—combined

with future investment returns—to pay for benefits earned by employees

in that year. To the extent that the plans do not have enough money over

time to pay for benefits, an unfunded liability can result—due, for

example, to lower-than-expected investment returns or decisions to give

retroactive benefit increases that apply to prior years of service. In

general, public employers bear all of the responsibility to pay for such

unfunded liabilities. As of 2008‑09, the most recent year for which data

are available from the State Controller’s Office, public employers paid

a total of about $14 billion to pension systems to cover benefit costs,

including several billion dollars to pay for unfunded liability costs.

Many California governments also provide their employees with options

to contribute funds to defined contribution retirement plans, which are

common in the private sector. Defined contribution plans do not promise

a defined benefit like those described above. Instead, these plans are

able to provide retirees with income generated from prior contributions

plus available investment returns. Employers have no obligation to

provide additional money to employees’ defined contribution accounts to

offset lower-than-expected investment returns.

In addition to defined benefit and defined contribution plans, many

California public employees also are eligible to receive Social Security

benefits. Teachers and many public safety workers, however, generally

are not eligible for such Social Security benefits.

Contract Clause. Courts have ruled that

public employees in California accrue certain rights to pension benefits

on the day that they are hired and, over time, they typically accumulate

more pension benefit rights. Contracts related to pensions sometimes are

included in collective bargaining agreements or in statutes, but in some

cases, they may be “implicit” (or unwritten) commitments based on their

employer’s past practices. Both the U.S. and California Constitutions

contain a clause—known as the Contract Clause—that prohibit the state or

its voters from impairing contractual obligations. Interpreting these

Contract Clauses, California courts have ruled for many decades that

pension benefits for current and past public employees can be reduced

only in rare cases—generally, when public employers provide a benefit

that is comparable and offsets the pension contract that is being

impaired or when employers previously have reserved the right to modify

pension arrangements.

Proposal

This measure amends the California Constitution to impose new

requirements and limitations concerning public employee retirement

benefits and the funding of those benefits by public employers and

employees. The measure establishes different retirement benefit

requirements for public employees hired before July 1, 2013 (referred to

below as “current public employees” or “current employees”) and public

employees hired on or after July 1, 2013 (referred to below as “future

public employees” or “future employees”). Assuming the measure is

adopted by voters in November 2012, current employees, therefore, would

include public employees hired between the date this measure is adopted

and June 30, 2013.

Pensions for Employees Hired On or After July 1, 2013

This section describes this measure’s limitations on retirement

benefits and the funding of such benefits for future public employees.

“Hybrid Plan” to Be Established. For future

public employees, the measure requires the Legislature, by a two-thirds

vote, to establish a hybrid retirement plan. (In retirement policies,

hybrid plans are considered plans that combine elements of defined

contribution and defined benefit pension plans.) The hybrid plan would

be designed so that a future employee’s retirement benefit would consist

of up to three components: defined contribution, defined benefit, and

federal Social Security benefits (if the employee is eligible). In

aggregate, these benefits would be designed to replace up to 75 percent

of an employee’s base wage (defined as an employee’s average highest

three years pay). It is unclear if the measure would result in each

component representing an equal share of the 75 percent.

The full benefit of the hybrid plan (75 percent replacement income)

would only be available to employees after attaining a specified age and

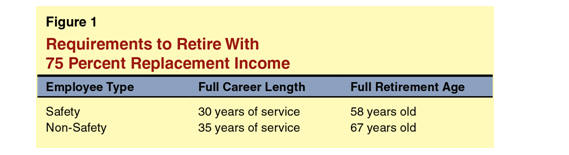

working a full career, as defined by the measure. Figure 1 shows the

career and age requirements necessary for safety and non-safety

employees to earn the full benefit. The measure specifies that an

employee can retire up to five years before he or she reaches the full

retirement age, but in this instance, the defined benefit portion of the

employee’s retirement benefit would be lower than if he or she retired

at the full retirement age.

Limitations on Defined Benefit Component of the Hybrid

Plan. The measure places specific limitations on the

defined benefit that would be available to future public employees. The

formula used to determine an employee’s pension would use his or her

average highest three years’ base wage as a public employee. The measure

would limit the size of a future employee’s defined benefit pension so

that it could not exceed (1) $100,000 (annually adjusted for inflation

beginning in July 2014), and (2) 25 percent (for employees who

participate in federal Social Security) or 50 percent (for employees who

do not participate in Social Security) of base wage after a full career

in government service. Under the measure, future employees and public

employers would share equally all costs associated with the defined

benefit, including any payments for unfunded liabilities. The measure

adds a requirement to the California Constitution that requires public

pension plans to adopt accounting and actuarial standards that minimize

unfunded liabilities related to future employees.

Defined Contribution Component of the Hybrid Plan.

Under this measure, public employers each would select a defined

contribution plan administrator. Upon retirement, a future employee

would have the option to use the money in his or her defined

contribution account to purchase an annuity underwritten by regulated

financial institutions meeting capital and financial standards

established by the Legislature. A government employer or retirement plan

may offer a collective defined contribution plan so long as the public

employer or taxpayers bear no risk for additional contributions. The

measure does not indicate whether, or to what extent, employers match

employee contributions to a defined contribution plan.

Pensions for Employees Hired Before July 1, 2013

This section describes this measure’s limitations of retirement

benefits and the funding of such benefits for current public employees.

Pension Modifications for Current Employees Retiring

After June 2016. Under this measure, a current employee

who retires after June 30, 2016 would be able to receive pension

benefits based only on the average of his or her highest three years’

average annual base wage.

Annual Review of Plans’ Funded Status. This

measure requires the administrator of each defined benefit retirement

plan for current employees to obtain an independent review of the plan’s

assets and liabilities and determine the plan’s funding status each

year. This independent review would have to follow potentially stricter

standards than those currently used by California’s defined benefit

public pension systems—specifically, the accounting standards and

assumptions established by federal law for private-sector pension plans,

including those established by the federal Employee Retirement Income

Security Act (ERISA). If the independent review determines that a plan’s

assets cover less than 80 percent of its liabilities, based on the

standards included in the measure, the plan would be considered “at

risk.” Once a plan is considered at risk, the public employer would be

required to either (1) appropriate the funds necessary to fund the plan

above the at-risk level or (2) find and declare that making the

appropriation necessary to fund the plan above the at-risk level would

impair the public entity’s ability to provide essential governmental

services. If a public employer makes the latter declaration, the measure

(1) requires employees to contribute more to the plan until the plan’s

funding exceeds the at-risk level, and (2) gives the affected employees

the right to withdraw from further participation in the at-risk plan and

enter into the retirement plan available to future employees. Moreover,

current employee and public employer contributions would change as

described below so long as pension plans are deemed at risk.

Contributions to Pay for Normal Costs of At-Risk Pension

Funds. Under this measure, if a public employer declares

that it cannot fund an at-risk plan for current employees without

impairing essential services, the public employer would be required to

limit its contributions to the normal cost to 6 percent of a non-safety

employee’s pay and 9 percent of a safety employee’s pay. For employees

who do not participate in Social Security, public employers would also

contribute an additional amount equal to 25 percent of the cost of the

defined benefit component of future employees’ hybrid plan. The balance

of the normal cost generally would be contributed by current employees,

provided, however, that current employees’ share of pension costs could

not increase by more than 3 percent of pay per year. (If this 3 percent

of pay limit, however, otherwise would result in normal costs not being

fully funded in any year, the public employer would be required to make

additional contributions above the limits described earlier to ensure

that normal costs are fully funded each year.)

Contributions to Pay for Unfunded Liability Costs of

At-Risk Pension Funds. If a public employer’s contribution

to the normal cost of an at-risk plan under this measure is less than it

contributed before the plan was considered at risk, the employer would

contribute the difference to the unfunded liability of the fund. The

measure states that public employers would be able to require employees

to make additional contributions to the unfunded liability determined to

be “necessary and equitable,” but the employee’s aggregate contribution

to normal costs and unfunded liabilities never could increase by more

than 3 percent of pay each year. There is no limit to the total amount

of pay current employees contribute to plans as long as their

contributions do not increase by more than 3 percent of pay each year.

Other Provisions

The measure makes a number of other changes to the retirement

benefits received by public employees and the systems that provide those

benefits.

Death and Disability Benefit Administration Changes.

Public employers that provide retirement benefits for their employees

may also “separately provide” death and disability benefits to their

employees, regardless of the employee’s date of hire. The cost of such

death and disability benefits is not subject to the cost limitations

established by the measure. Death and disability benefits for employees

hired on or after July 1, 2013 would have to be provided separately from

the system that administers their pension, defined contribution, or

similar retirement benefits, except for integrated defined contribution

benefits (an undefined term).

Retroactive Benefits Prohibited. Under this

measure, public employers no longer would be able to provide increases

in pension plan benefits or formulae applicable to prior years of

service—otherwise known as “retroactive increases” in employees’ pension

benefits.

Limits on Cost-of-Living Increases for All Current and

Future Retirees. For all current and future state and

local retirees, this measure states that it would amend existing pension

benefit contracts to limit annual percentage cost-of-living increases

after December 31, 2012, to no more than the annual Social Security

cost-of-living increase.

Pensions for Certain Felons Prohibited.

This measure provides that a public employee convicted of a felony

arising out of his or her service to a government agency cannot receive

public pension benefits for his or her service to “such government

agency.” (It is not entirely clear whether this would prohibit the felon

from receiving pension benefits related to their service for another

government agency, for which there was no related felony conviction.)

“Air Time” Purchases Generally Prohibited.

This measure prohibits government employees from purchasing additional

retirement service credit—often called air time—for any period that does

not qualify as government service or military service.

Pension Contribution Holidays Generally Prohibited.

Both public employers and employees would be required to contribute to

the normal cost of defined benefit pension plans each year unless the

plan is more than 120 percent funded under the various private-sector,

ERISA, and other funding standards described in this measure for

evaluating the at-risk status of current employees’ pension plans.

Alterations to Future Pension Benefit Accruals.

This measure requires public employers to reserve the right to make

prospective changes to pension, defined contribution, and similar

retirement benefits at their sole discretion. (It appears that this

change would apply to current—as well as future—employees under this

measure.)

Changes to Composition of Public Retirement Boards.

This measure amends existing constitutional provisions related to the

composition of California’s public retirement system boards. Under this

measure, beginning on July 1, 2013, at least a majority of the members

of the governing board of every public retirement system would be

required to (1) have demonstrated expertise in a specified area and (2)

not be members or beneficiaries of any California government pension

plan or retirement system or have immediate family members who are

members or beneficiaries of such a plan or system. In addition, the

state’s Director of Finance—an official appointed by the Governor with

the advice and consent of the State Senate—would serve as a voting

member of any state or local pension system with total liabilities that

exceed $5 billion. (Because this $5 billion figure is not adjusted for

inflation, over time, the Director of Finance probably would join each

public pension board in the state.)

Judges Excluded From the Pension Limits.

This measure applies its various pension plan changes to current and

future public employees, which the measure specifically defines to

exclude California’s judges. Accordingly, the judges’ retirements

plans—administered by California Public Employees’ Retirement

System—would be unaffected by this measure.

State Contract Clause Would Not Apply. The

measure contains provisions that override existing sections of the

California Constitution and other laws to the extent that they are in

conflict with this measure’s requirements. For example, changes to

current employee and related public employer pension contributions are

required to be put in place notwithstanding provisions of existing

contracts or the California Constitution’s Contract Clause.

Fiscal Effects

This measure would make changes to hundreds of different public

employee pension plans throughout the state. It would almost certainly

be subject to a wide array of serious legal challenges pertaining to its

changes to benefit plans that enroll current and retired public

employees, including, but not limited to, suits alleging that the

measure would impair public contract obligations under the U.S. and/or

California Constitutions. Moreover, the provisions of this measure would

be subject to potentially varying interpretations by public employers

and pension systems. In some cases, provisions of the federal Internal

Revenue Code—which governs the tax status of public pension plans—may

limit the flexibility of pension systems to implement certain provisions

of this measure. Given all of these factors, there is large uncertainty

about this measure’s possible fiscal effects, which we attempt to

describe below. There is also large uncertainty about how this

measure—applying broadly to nearly every type of government worker—would

apply to the variety of public employees in California, which include

teachers, public safety workers, office workers, professors, and many

others.

Impacts Related to Future Employees

Potentially Large Retirement Benefit Savings Over the

Long Term. Under the U.S. and California Constitutions,

public employers generally are free to alter existing contractual

obligations, such as those for pension benefits, as applied to employees

hired after the date of that alteration. The fiscal effects of these

provisions on state and local governments would depend on the design of

the hybrid retirement plan adopted by the Legislature. Depending on this

program design, California public employers potentially would be able to

reduce their retirement benefit costs by billions of dollars per year

(in current dollars) once public employees hired on or after July 1,

2013 constitute the bulk of their workforces. This likely would not

occur until several decades from now.

Included in such cost savings are likely reductions in public

employers’ costs to provide health benefits to retired future employees.

While not affected specifically by this measure, these retiree health

benefits generally would cost less for governments over the long term

because future employees would likely retire at later ages than current

employees. Thus, governments would pay for these benefits for fewer

years, and under current federal law, the Medicare program of the U.S.

government would pay a greater share of these benefits for future

employees.

Offsetting Increases in Other Compensation Costs.

To ensure that total compensation for future employees is

competitive with that offered by other employers, many public employers

likely would increase pay, health benefits, or other non-retirement

benefits for future employees. This would partially offset the

retirement cost savings described above.

Impacts Related to Current Employees

It is unclear how exactly this measure’s at-risk funding status

evaluations would have to be conducted. We assume for purposes of this

analysis that most—perhaps all—California public pension plans (which

have significant unfunded liabilities under existing accounting methods)

would initially be at risk under the definitions of this measure.

Furthermore, we assume few public entities would be able to appropriate

enough money to immediately change their plans’ status. As noted above,

this could result in substantial changes to employer and current

employee contributions to pension plans so long as the at-risk status

persists.

Possible Decrease in Pension System Investment Returns.

Under this measure, future employees’ hybrid plans would

contain defined benefit pension components that are considerably smaller

than those offered to current employees. Total contributions to pension

systems for future employees’ defined benefits, therefore, will be much

smaller than the total current contributions related to current and past

employees. Defined benefit pension plans would experience a reduction in

their incoming cash flow that would become more substantial over the

coming few decades, as future employees grow to a larger share of the

public workforce. These reductions in cash flow could cause many

California pension plans to shift their allocation of investments to

ensure they can meet existing benefit obligations, thereby reducing

their average annual future investment returns. In general, when pension

plans have to assume lower investment returns in this manner, their

estimated normal costs increase, as do estimates of their unfunded

liabilities. For these reasons, in the short and medium term (perhaps

over the next two or three decades), these changes could result in

public employers having to contribute over $1 billion more per year (in

current dollars) to cover pension costs of current and past employees.

Effects of Shift of Costs to Current Employees.

This measure contains provisions that seek to shift pension

costs from public employers to current employees over time. For example,

the measure contains limits on employer contributions for normal costs

related to current employees and allows shifts of unfunded liability

costs to employees in some cases. If able to be implemented fully, these

provisions could help reduce some public employers’ annual pension costs

during some periods in the coming few decades. By shifting costs to

current employees in this manner, some public employers could encourage

or induce employees to “opt out” of existing pension plans and shift to

the plans authorized for future employees under this measure.

Other Potential Public Employer Savings.

For some current employees, this measure would provide for lower pension

benefit costs by requiring benefits to be based on the highest three

years’ average base pay—rather than existing benefit provisions (often

based on the highest single year’s pay). The measure also would limit

future cost-of-living increases for all current and future retirees. If

able to be implemented, these changes could reduce public employers’

costs for current employee benefits during the next few decades. The

amount of this savings is unknown, but likely of a lower magnitude than

the other savings and cost issues described above.

Potential Public Employer Costs. As with

their costs to compensate future employees, public employers likely

would increase pay, health benefits, or other non-retirement benefits

for current employees to ensure their competitiveness in the labor

market.

It is unclear exactly how the measure’s provisions for death and

disability benefits would affect current employees and their

beneficiaries. To the extent that the measure requires these benefits to

be provided outside of existing retirement systems and governments

provide death and disability benefits similar to those now in place,

increased costs could result for some public employers.

Conclusion

In the short and medium term (perhaps the next two or three decades),

the various financial effects of this measure make its net fiscal

effects for state and local employers difficult to determine. During

these decades, public employers may face either increased costs or

savings related principally to current and past employees’ pension and

other retirement benefits.

Over time, a greater portion of public employers’ personnel costs

would be related to future employees—those hired on or after July 1,

2013, and, therefore, subject to the hybrid plan requirements to be

adopted by the Legislature under this measure. For these future

employees, depending on this hybrid plan’s design, governments may

experience substantial savings in retirement costs. These savings would

be partially offset by higher costs for employee salaries and

non-retirement benefits in order to keep public-sector compensation

levels competitive in the labor market. Accordingly, when costs for

these future employees constitute the bulk of public employers’

personnel costs—several decades from now—governments could experience

significant net savings.

Summary of Fiscal Effects

This measure would result in the following major fiscal effects for

state and local governments:

- Over the next two or three decades, either increased annual

costs or annual savings in state and local government personnel

costs, depending on how this measure is interpreted and

administered.

- In the long run (several decades from now), depending on how the

Legislature designs the required hybrid retirement plan, potential

annual savings in state and local government personnel costs of

billions of dollars per year (in current dollars), offset to some

extent by increases in other employee compensation costs.

Return to Propositions

Return to Legislative Analyst's Office Home Page