LAO Contacts

- California Student Aid Commission

- University of California

- Hastings College of the Law

- California Community Colleges

- California State University

LAO Report

February 16, 2017The 2017-18 Budget

Higher Education Analysis

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Higher Education in Context

- University of California

- California State University

- California Community Colleges

- Hastings College of the Law

- California Student Aid Commission

- Summary of Recommendations

Executive Summary

In this report, we analyze the Governor’s higher education budget proposals. Below, we highlight key messages from the report.

Key Messages

UC’s Spending Plan Raises Several Issues to Consider. First, regarding enrollment, the state recently has begun setting the University of California’s (UC’s) enrollment target one year out to better align with UC’s admissions calendar. We recommend the Legislature continue this approach by setting a 2018‑19 enrollment target but waiting to set the specific target until after it has received two forthcoming reports. We recommend using trailer legislation to provide the associated funding in 2018‑19. Second, UC’s Academic Excellence initiative lacks clear objectives and detail. If UC is unable to provide sufficient justification for this initiative, we recommend redirecting the associated funding to higher priorities. Finally, the Legislature faces two other significant UC decisions in the coming year: (1) whether to use Proposition 56 funding to replace or augment existing funding for graduate medical education, and (2) whether to allow UC to increase nonresident enrollment in 2017‑18.

CSU Facing Notable Cost Pressures, Difficult Decisions Between Tuition Increases and Cost Increases. The California State University (CSU) faces significant cost pressures in the budget year—most notably, pressure to fund faculty bargaining agreements already ratified by the Board of Trustees last spring. Given recent compensation increases for faculty, pressure also exists to provide some compensation increase for other employee groups with expiring contracts. Another notable cost pressure is funding enrollment growth for eligible transfer students, some of whom have been denied admission in recent years. Were the Legislature to approve the General Fund level proposed by the Governor, CSU asserts it would be able to cover the costs of the previously ratified faculty contracts and some basic cost increases. It would not be able to provide compensation increases for other employee groups or enroll additional transfer students. Were the Legislature to want these other priorities funded, additional General Fund support or tuition revenue would be required. As tuition charges have been flat at CSU for the past six years, the Legislature may want to consider a tuition increase. A 2.5 percent tuition increase would generate enough revenue to support a 1 percent compensation pool and 1 percent enrollment growth for eligible transfer students.

California Community Colleges (CCC) Budget Proposals Could be Improved Around the Edges. The Governor proposes to increase apportionments $197 million to cover enrollment growth, a cost‑of‑living adjustment, and a further small unallocated increase. We recommend the Legislature approve these increases, as providing substantial ongoing, general purpose funding would help colleges address certain cost pressures, such as covering pension rate increases, as well as implement local priorities. The Governor also provides $150 million for a one‑time initiative. Though we recommend the Legislature dedicate some new funding for one‑time purposes, we have concerns with the Governor’s guided pathways initiative. In particular, the proposal departs from existing, successful pathway initiatives in key ways and lacks many important details. Nonetheless, the concept has potential and we recommend the Legislature ask the administration and the Chancellor to provide specific additional details about it during spring hearings.

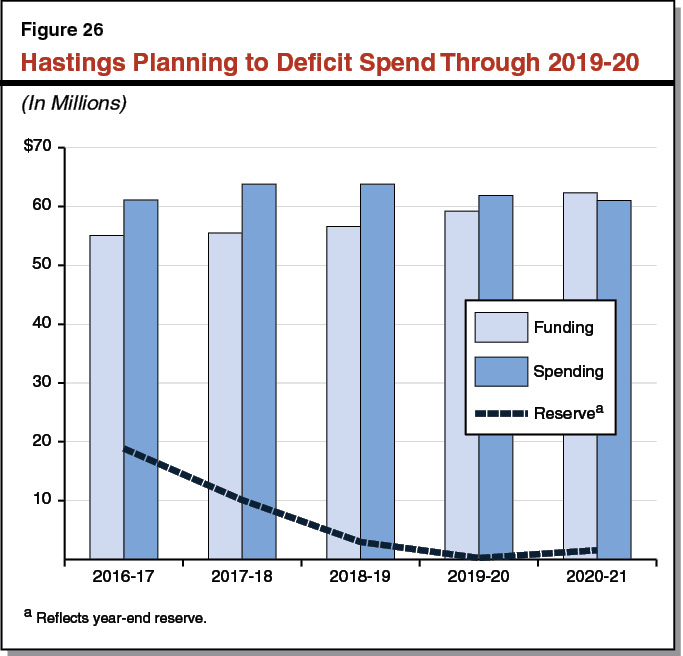

Hastings College of the Law’s Recent Budgetary Approach Raises Concern. In 2016‑17, Hastings anticipates running a $6.4 million operating deficit. Under the Governor’s budget, this trend would continue, with Hastings running an even larger ($8.3 million) deficit in 2017‑18, ending the year with a $10.2 million reserve. Hastings’ recent budget problems stem primarily from its decision to provide more generous financial aid packages to incoming students—a strategy designed to attract higher quality students and boost the school’s prestige. To address its operating deficit, Hastings anticipates it soon will have to reduce spending on financial aid and increase tuition levels—effectively counteracting its earlier decisions. We recommend the Legislature question Hastings during spring budget hearings on its recent budgetary approach, as it appears not to achieve any long‑term objectives while potentially putting pressure on the state in future years to stabilize the school’s financial condition.

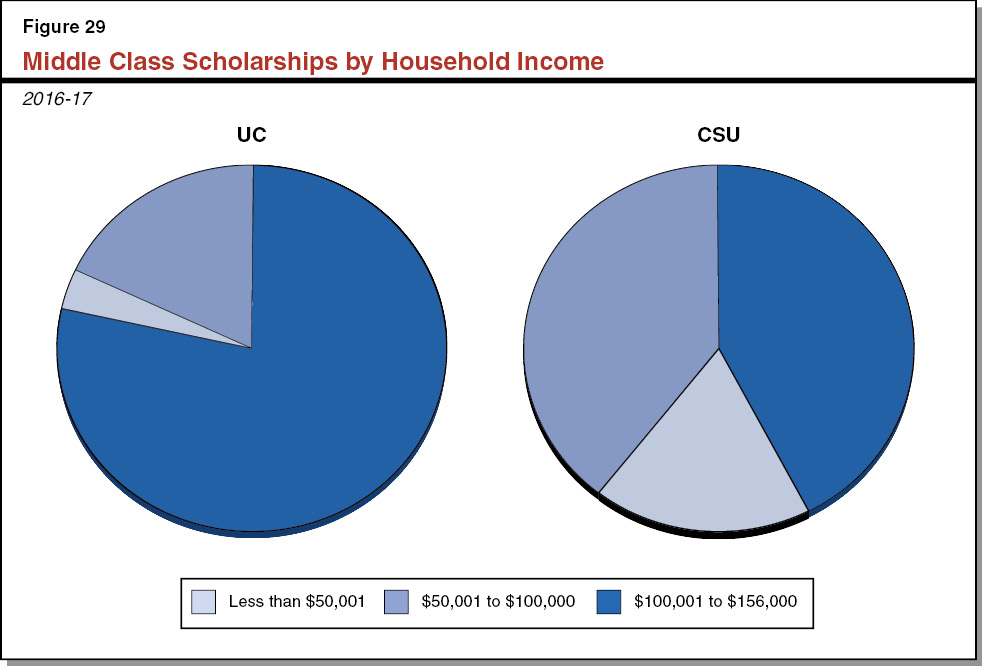

Recommend Restructuring State and Institutional Financial Aid Programs. The Governor proposes to phase out Middle Class Scholarships starting in 2017‑18. According to the administration, the phase out is intended to address a state budget shortfall while prioritizing state aid for financially needy students served through the Cal Grant program. We concur with the Governor that prioritizing aid for the financially neediest students is the more effective way to promote college access. Meeting this objective, however, is difficult due to the plethora of existing state and institutional aid programs, which have different eligibility criteria and rules. We recommend the Legislature explore ways to restructure these programs, such as by consolidating them into a single grant or establishing uniform and coordinated eligibility requirements. Such an approach would better position the Legislature to use available funds for optimizing college access and affordability.

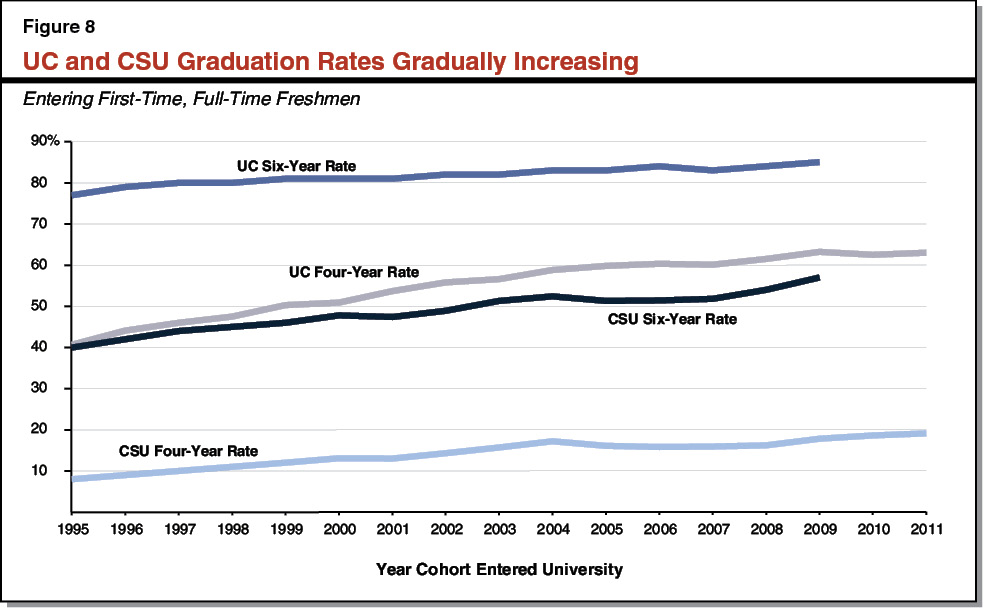

Further Improvement Needed in Segments’ Performance and Performance Framework. The segments’ annual performance reports show that performance is improving in some instances but additional improvement is needed. For example, UC’s and CSU’s graduation rates have increased gradually over time, though even now less than 60 percent of CSU freshmen graduate within six years. At CCC, a slightly greater share of students is successfully moving from remedial into college‑level coursework, though overall completion rates are declining. Excess unit‑taking remains a problem at CSU and CCC, with the average CSU student taking 18 semester units (six courses) more than required to obtain a bachelor’s degree and the average CCC student generating more than double the required units for an associate degree. We think opportunities exist to improve the state’s overall performance framework. In particular, we recommend the Legislature direct the CCC Chancellor’s Office to adopt a redesigned performance measurement system that promotes greater transparency and more challenging targets. We also recommend the Legislature collaborate with all three segments to develop meaningful measures related to (1) efficiency and (2) outcomes for college graduates.

Introduction

In this report, we analyze the Governor’s higher education budget proposals. We begin by providing background on higher education in California. In the next five sections, we analyze the Governor’s budget proposals for (1) the University of California, (2) the California State University, (3) the California Community Colleges, (4) Hastings College of the Law, and (5) the California Student Aid Commission. In each of these sections, we provide relevant background, describe the proposals, assess the proposals, and make associated recommendations. The final section consists of a summary of the recommendations we make throughout the report. For many higher education budget tables not included in this report, please see “EdBudget Tables” on our website.

Back to the TopHigher Education in Context

California Has Public and Private Higher Education Sectors. As Figure 1 shows, California has 113 California Community Colleges (CCC), 23 California State University (CSU) campuses, 10 University of California (UC) campuses, and 1 UC‑affiliated law school. Its private sector includes about 175 nonprofit colleges and universities and more than 1,000 for‑profit institutions. About three‑fourths of full‑time equivalent (FTE) enrollment in California is in the public sector. This share is somewhat higher than the share in the public sector in the rest of the nation (two‑thirds of FTE enrollment). California’s share of students in nonprofit colleges is lower than the rest of the nation, whereas its share in for‑profit colleges is similar to the rest of the nation.

Three Key Aspects of Higher Education in California. Below, we provide background on: (1) public higher education enrollment, (2) tuition and financial aid, and (3) institutional and student performance. In cases where data is available, we provide perspective on how California compares to other states. Throughout this section, we cite the most recent data available from government sources. In some cases, particularly for national comparison data, the most recent data is several years old.

Enrollment

Below, we discuss higher education eligibility policies, enrollment trends, and enrollment funding.

Eligibility

Master Plan Sets State’s Goals for College Access. Written in 1960, the California Master Plan for Higher Education established a number of key policies for the state’s public sector. Most notably, the Master Plan set forth each of the three segments’ missions and student eligibility policies. The state and the segments historically have based their enrollment, budget, and physical capacity decisions upon these policies.

Master Plan Assigns Each Public Segment a Different Mission. The Master Plan calls for CCC to provide basic skills instruction, career technical education, and lower‑division instruction. It also sets forth that CCC is to grant associate degrees and certificates as well as prepare students to transfer to four‑year colleges. It calls for CSU to focus on instruction leading to bachelor’s and master’s degrees. It envisions UC as the state’s primary public research university and directs it to grant bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees.

Master Plan Has Each Public Segment Differing in Selectivity and Cost. Each segment serves somewhat different student populations. The CCC system is to be open to all students over the age of 18, CSU is to be somewhat selective, and UC is to be the most selective segment. Each segment also has different expected costs. CCC has the lowest per‑student cost and UC the highest per‑student (given its research mission).

Master Plan Sets Different Eligibility Policies for Each Segment. The Master Plan envisions CCC as open access, allowing any adult to enroll without set eligibility criteria. By comparison, CSU and UC have eligibility criteria, with UC’s criteria being more selective. For freshman eligibility, UC is to draw from the top 12.5 percent of public high school graduates, whereas CSU is to draw from the top 33 percent. For transfer eligibility, UC is to admit students who have completed lower‑division coursework with at least a 2.4 grade point average, whereas CSU is to admit those having at least a 2.0 grade point average. The transfer function is intended both to (1) provide students who do not qualify for freshman admission an opportunity to earn a bachelor’s degree and (2) reduce costs for students seeking a bachelor’s degree by allowing them to attend CCC for their lower‑division coursework. The Master Plan does not include eligibility criteria for graduate students. Instead, it calls for the universities to consider graduate enrollment in light of workforce needs, such as for college professors and physicians.

UC and CSU Set Admission Requirements to Reflect Eligibility Policies. For freshmen, the university systems are responsible for setting specific admission criteria intended to reflect their respective eligibility pools. As a minimum criterion, both systems require high school students to complete a series of college preparatory courses known as the “A‑G” series. The series includes courses in math, science, English, and other subjects. To qualify for admission, students must complete this series while earning a certain combination of course grades and scores on standardized tests. In 2014‑15, 43 percent of high school graduates completed the A‑G series with a “C” or better in each course. For transfer students, the university systems set general education and pre‑major course requirements. Transfer students completing these courses and meeting the Master Plan’s grade point average requirements are eligible for admission.

Available Evidence Suggests Current Admission Criteria Not Perfectly Aligned to Eligibility Policies. In 2015, 13 percent of high school graduates were admitted to UC and 30 percent to CSU. The segments are likely drawing for admission from larger pools than these percentages, as some eligible students likely do not apply. For example, some eligible students might apply to UC but not CSU, and some eligible students might not apply to either institution, instead opting to attend community colleges, in‑state private universities, or out‑of‑state institutions. As a result, both university systems are very likely exceeding their Master Plan freshman eligibility targets. For transfer students, in fall 2016, UC reports that it admits all eligible applicants, whereas CSU reports denying admission to about 10,300 eligible applicants, mostly nonlocal applicants.

State Currently Conducting a Freshman Eligibility Study to Obtain Better Data. To gauge whether the universities are drawing from their freshman eligibility pools, the state periodically funds “eligibility studies.” These studies examine public high school graduates’ transcripts to determine the proportion of students meeting each university system’s admission criteria. If the proportion is significantly different from 12.5 percent and 33 percent for UC and CSU, respectively, the universities are expected to adjust their admission policies accordingly. For example, UC tightened its admission criteria after an eligibility study conducted in 2003 found it drawing from the top 14.4 percent of public high school graduates. The last eligibility study was conducted in 2007. The 2015‑16 budget provided $1 million for the Office of Planning and Research to complete a new eligibility study by December 1, 2016. (As of the release of this report, the study was not yet published.)

Legislature Recently Directed Segments to Develop Plans for Producing More Degree and Credential Holders. The Public Policy Institute of California prepared a baseline forecast showing UC and CSU awarding around 750,000 and 1.3 million bachelor’s degrees, respectively, between 2015‑16 and 2029‑30. The 2016‑17 budget requires UC and CSU to develop plans to produce 250,000 and 480,000 more bachelor’s degrees, respectively, than these baseline projections. To reach these targets, the budget specifies that the university systems could propose changes that would broaden eligibility, increase enrollment, or improve graduation rates. The 2016‑17 budget also requires CCC to develop a plan that recommends policy and budget changes needed to produce 1 million associate and vocational credentials between 2017 and 2027. Unlike for UC and CSU, no baseline projection was prepared for CCC. The segments are required to submit these reports to the Legislature by March 2017.

Enrollment Trends

Public Sector Enrollment Has Increased Over Past Decade. Over the past decade, resident enrollment at all three segments has increased. (In the box below, we discuss trends in nonresident enrollment.) Compared to 2005‑06, resident enrollment in 2015‑16 was 4 percent (about 44,000 FTE students) higher at CCC, 18 percent (about 58,000 FTE students) higher at CSU, and 12 percent (about 22,000 FTE students) higher at UC. Over this period, CCC enrollment was the most volatile—with a spread of almost 150,000 FTE students from its peak in 2008‑09 to its trough in 2012‑13. Average annual growth over this period was 0.5 percent at CCC, 1.8 percent at CSU, and 1.2 percent at UC. During the preceding two decades (1985‑86 through 2005‑06), average annual growth was 2 percent at CCC, 1.5 percent at CSU, and 2 percent at UC. In 2015‑16, total FTE enrollment reached almost 1,146,000 at CCC, 371,000 at CSU, and 210,000 at UC.

Nonresident Enrollment

All Three Segments Enroll Nonresident Students. Currently, nonresidents make up 17 percent of all students at UC, 6 percent at CSU, and 4 percent at CCC. At UC and CSU, a majority of nonresident students are undergraduates. Most graduate students are able to establish residency after one year of enrolling.

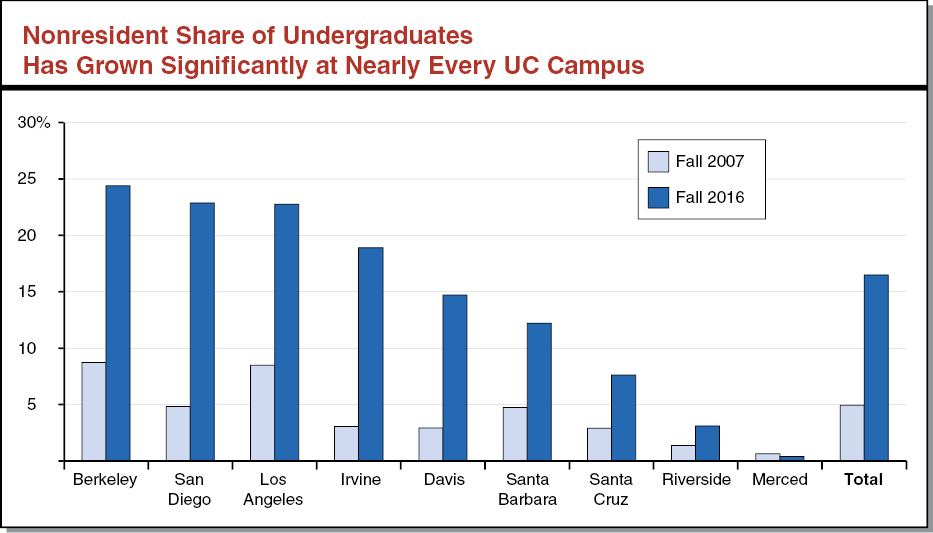

Nonresident Enrollment Varies Significantly By Campus. Within each segment, some campuses, typically high‑demand campuses, have much higher proportions of nonresident students than other campuses. For example, nonresidents comprise more than 20 percent of enrollment at UC’s four most selective campuses (Berkeley, San Diego, Los Angeles, and Irvine). Several selective CSU campuses (San Luis Obispo, San Diego, and San Jose) also enroll greater proportions than other CSU campuses. CCC campuses with notable proportions of nonresident students (such as Santa Monica and Santa Barbara) have higher enrollment demand due to their strong transfer programs.

Undergraduate Nonresident Enrollment Has Notably Increased at UC. UC has experienced the largest growth in nonresident students in the recent past, particularly among undergraduates. UC undergraduate nonresident enrollment increased from about 7,100 students in 2007‑08 to an estimated 32,300 students in 2016‑17. Nonresidents’ share of the UC undergraduate student body more than tripled during this time. As the figure below shows, the share of nonresident undergraduates has grown at every UC campus, except for Merced. UC asserts that the growth in nonresident undergraduate students allowed it to further grow resident enrollment. This is because UC charges nonresidents a supplemental charge (around $27,000) that significantly exceeds their average expected cost (around $10,000).

Some UC and CSU Campuses Much More Selective Than Other Campuses. Though enrollment has been increasing at all three public segments, certain UC campuses (such as Berkeley and Los Angeles) continue to deny many applicants admission. Eligible freshmen applicants who are not accepted to their first choice campus are redirected to UC Merced. Differences in enrollment demand also exist across CSU campuses. High‑demand CSU campuses generally give enrollment priority to eligible applicants from their surrounding areas. Six campuses (Fresno, Fullerton, Long Beach, San Diego, San Jose, and San Luis Obispo), however, do not guarantee admission even to their local students.

Number of High School Graduates One Factor Driving Enrollment Demand. Enrollment demand for the three public segments is driven in part by changes in the number of high school graduates. Assuming no other change, an increase in the number of California high school graduates causes a proportionate increase in the number of students interested in attending one of the public segments. The relationship is particularly strong at CSU and UC. For these two segments, an increase in freshman enrollment contributes to an increase in transfer enrollment, as CSU typically enrolls one transfer student for every one freshman and UC aims to enroll one transfer student for every two freshmen. Increases in high school graduates also can have a future effect on transfer enrollment, as some of those students will work their way through the transfer process at CCC over the course of a few years.

In Near Term, High School Graduates Projected to Grow Very Slowly. The Department of Finance’s Demographic Unit does projections of high school graduates. Its most recent forecast projects high school graduates increasing from about 420,000 in 2016‑17 to 445,000 in 2023‑24, followed by declines in the following two years. Over this period (through 2025‑26), the projected average annual growth rate is less than 1 percent. (In our review, we found the Department of Finance’s projections of high school graduates have been fairly accurate one to two years out, but its model tends to underproject high school graduates five to ten years out.)

College Participation Rates Another Factor in Gauging Enrollment Demand. For any demographic group (for example, high school graduates), the percentage of individuals who are enrolled in college is that group’s college participation rate. Other factors remaining constant, if participation rates increase, then enrollment demand increases. Participation rates can change due to a number of factors, including state and institutional efforts to promote college going, the availability and attractiveness of other postsecondary and employment options, student fee levels, and the availability of financial aid.

Freshman College Participation Rates Somewhat Steady. The federal Department of Education estimates that the overall college participation rate of California high school graduates was 59 percent in fall 2012 (the most recent year of available data), somewhat below the fall 2010 rate of 62 percent. In both years, participation rates in California were slightly below the national average. Participation rates in California’s public sector also have been somewhat steady. Between fall 2007 and fall 2015, for example, participation rates have ranged between 7 percent to 8 percent at UC and 11 to 13 percent at CSU. (No comparable CCC data are available.)

Enrollment Funding

Traditionally, State Sets Enrollment Target for Each Segment. Under the traditional approach to funding enrollment, the state first considers the various factors discussed above and sets an enrollment target for each segment. Over the past few decades, the state typically has set one overall enrollment target for each segment rather than separate targets for undergraduate and graduate students. If the state increases a segment’s overall enrollment target, then the state decides how much associated funding to provide for enrollment growth.

UC and CSU Enrollment Growth Traditionally Funded Based on Marginal Cost Formula. In the case of the universities, the state for decades funded enrollment growth according to a “marginal cost” formula that estimated the cost of admitting one additional student. The most recently used formula assumed the universities would hire a new professor for roughly every 19 additional students and linked the cost of the new professor to the average salary of newly hired faculty. In addition, the formula included the average cost per student for faculty benefits, academic and instructional support, student services, instructional equipment, and operations and maintenance of physical infrastructure. The marginal cost formula was based on the cost of all enrollment (undergraduate and graduate students and all academic disciplines excluding health sciences). The state provided each system flexibility to determine how to distribute enrollment funding to its campuses. If the systems did not meet the enrollment target specified in the budget within a certain margin, then the associated enrollment growth funding reverted back to the state.

Over Past Decade, State Has Not Consistently and Clearly Linked Funding to Enrollment Growth for UC and CSU. The state began omitting enrollment targets in the 2008‑09 budget, when it entered the most recent recession and reduced base funding for UC and CSU. The purpose was to provide UC and CSU flexibility to manage state funding reductions. The state resumed enrollment funding from 2010‑11 through 2012‑13, but, in two of the three years, it did not require the universities to return money to the state if they fell short of the target. In 2013‑14 and 2014‑15, the state again chose not to include enrollment targets in the budget. Beginning in 2015‑16, the state resumed setting enrollment targets for UC and CSU, although its approach for UC differed somewhat from previous years. We describe this different approach below.

New Approach Recently Taken for UC. Whereas the state traditionally has set enrollment targets for the budget year, it recently began setting UC’s enrollment target for the subsequent academic year. This change was intended to give UC more time to respond to legislative direction. In the 2015‑16 budget, the state set a goal for UC to enroll 5,000 more resident undergraduate students by 2016‑17 (than the 2014‑15 level) and allocated an associated $25 million in ongoing funding for the growth. The state continued this practice in 2016‑17, setting an expectation that UC enroll 2,500 more resident undergraduate students in 2017‑18 than in 2016‑17. It providing an associated $18.5 million, contingent on UC providing sufficient evidence by May 1, 2017 that it would meet this goal. (The funding also is contingent on UC adopting a policy by the same deadline that limits nonresident enrollment.) The state did not set targets for graduate student enrollment in either year.

State Continues to Link Funding to Enrollment Growth for CCC. Whereas the state’s approach to funding UC and CSU enrollment has fluctuated in recent years, the state has maintained its traditional approach to budgeting for CCC enrollment growth. State law requires that CCC’s annual budget request for enrollment growth be based, at minimum, on changes in the adult population and excess unemployment (defined as an unemployment rate higher than 5 percent). The CCC also may request enrollment growth to cover “unfunded” (or over‑cap) enrollment. The Governor and Legislature do not have to approve enrollment growth at the requested level. As with UC and CSU enrollment, their decisions tend to reflect the state’s budget condition.

Back to the TopTuition and Financial Aid

Below, we examine affordability for undergraduate students from a variety of angles, beginning with a focus on student tuition and living costs, then turning to financial aid.

Tuition and Living Costs

State Currently Does Not Have a Tuition Policy. A tuition policy establishes how tuition levels are to be adjusted over time. Depending on the policy, the tuition charge either explicitly or implicitly represents the share of education cost to be borne by full‑fee‑paying students and the state. The state share of cost consists of the subsidy it provides directly to each of the higher education segments as well as the financial aid it provides to financially needy students to help them cover their tuition charges. Though California had a tuition policy for several years during the late 1980s and early 1990s, it has not had one the last couple of decades.

Tuition Highest at UC, Lowest at CCC. For full‑time undergraduate students, UC charges $12,294, CSU charges $5,472, and CCC charges $1,380 ($46 per unit for 30 units). Campuses in each system also charge additional fees for specific services or activities—such as student health services. Compared to similar public universities in other states, UC’s tuition and fees tend to be higher, whereas CSU’s tend to be much lower. CCC tuition and fees are the lowest in the country compared to other public community colleges, about one‑third of the national average

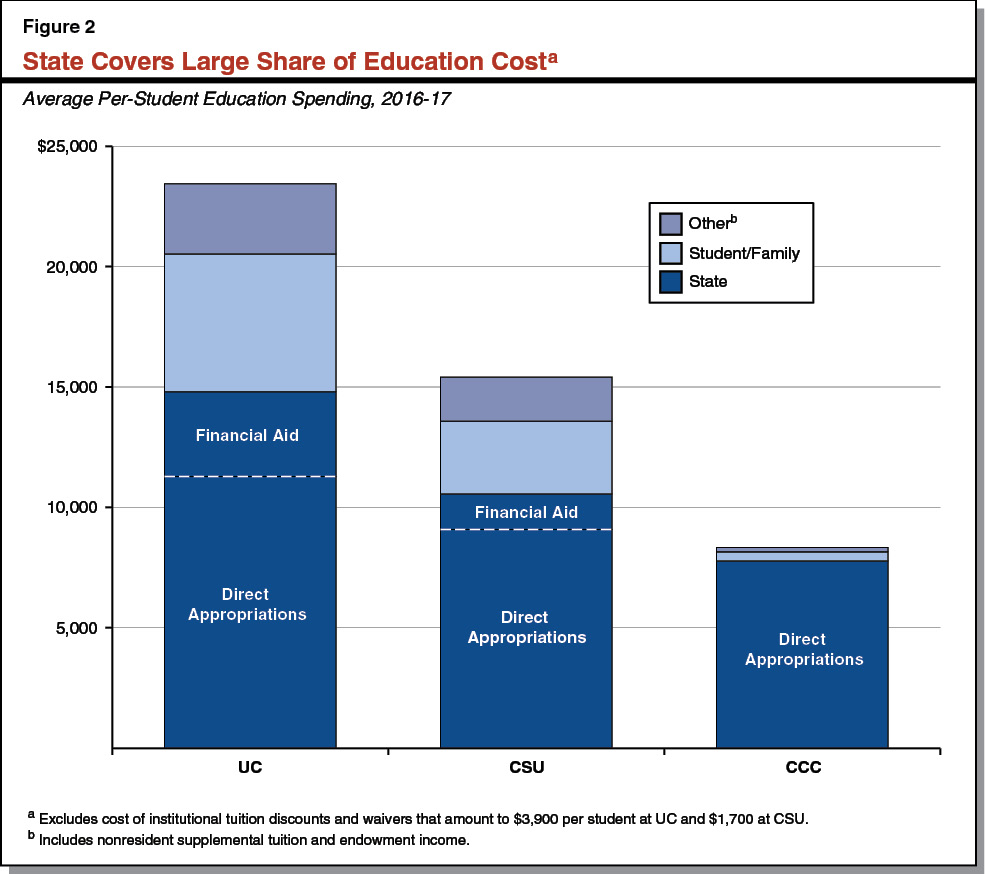

Students and Families Cover Only a Fraction of Education Costs, State Pays Much Larger Share. Tuition and fee levels vary across the segments because (1) their education costs are different, and (2) the state covers a different share of these costs. Figure 2 shows the proportion of education cost at each segment that is covered by students and families, the state, and other fund sources, such as nonresident supplemental tuition. The figure shows both state support in the form of direct appropriations to the segments as well as from state financial aid. At UC and CSU, the student and family share of education costs on average is 24 percent and 20 percent, respectively, with the state share comprising 63 percent at UC and 69 percent at CSU. Other fund sources cover 12 percent at each system. At CCC, the student and family share is only 5 percent, versus a state share of 94 percent. The average share of cost covered by students and families masks some differences, with the share for a particular student depending on the amount of financial aid he or she receives. Even students and families paying full tuition, however, pay much less than the cost of education. Specifically, they pay for 52 percent of education costs at UC, 36 percent at CSU, and 17 percent at CCC. (Not accounted for in the figure are federal grants and tuition tax credits that further reduce the average student and family share of education costs.)

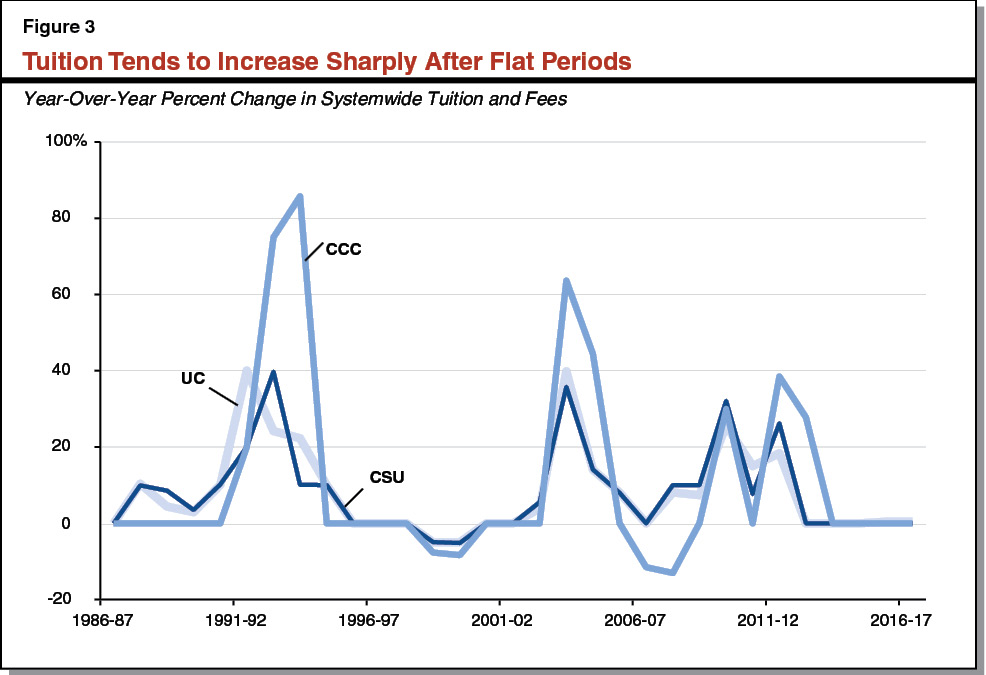

Tuition and Fees Tend to Be Volatile. As shown in Figure 3, tuition and fee levels in California tend to follow a pattern of flat periods punctuated by sharp increases. The flat periods generally correspond to years in which the state experienced economic growth, while the periods of steep increases generally correspond to years when the state experienced a recession. During recessions, the state has often balanced its budget in part by reducing state funding for the segments. UC and CSU, in turn, increased tuition charges to make up for the loss of state support, and the state increased fees at CCC. This pattern could be affected by the new state reserve requirements enacted under Proposition 2 (2014), which could mitigate state revenue losses during recessions.

Estimated Living Costs Vary Based on Several Factors. Apart from tuition, students incur other costs to attend college, including housing and food, personal expenses, books and supplies, and transportation. Estimated living costs vary across each system because each system determines for itself how to estimate these costs. Costs vary across campuses within each system because some expenses (such as housing) vary by location. Costs also vary depending on whether a student lives on campus, off campus not with family, or off campus with family. For example, as Figure 4 shows, UC estimates students living with family face the lowest costs—about 30 percent lower than students living off campus and almost 50 percent lower than students living on campus.

Figure 4

Living Expenses Vary by Student Living Arrangement

University of California, 2015‑16

|

On campus |

Off campus |

Living With Family |

|

|

Rent and food |

$14,199 |

$9,391 |

$4,700 |

|

Health carea |

2,130 |

2,169 |

1,818 |

|

Transportation |

687 |

1,247 |

1,659 |

|

Otherb |

1,700 |

1,884 |

2,032 |

|

Totals |

$18,716 |

$14,691 |

$10,209 |

|

aPrimarily reflects health insurance costs. Students insured through a family member are not required to purchase insurance. bIncludes expenses for clothing, entertainment, and recreation. |

|||

Financial Aid

Various Types of Financial Aid Help Students Cover Their Cost of Attendance. Types of financial aid include gift aid (grants, scholarships, and tuition waivers that students do not have to pay back); loans (that students must repay); federal tax benefits (that can reduce income tax payments or provide a tax refund); and subsidized work‑study programs (that provide income to students while making it more attractive for employers to hire students). Financial aid may be need based (for students who otherwise might be unable to afford college) or nonneed based (typically scholarships or other payments based on academic merit, athletic talent, or military service). Need‑based aid programs assess need based on the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA. The federal government has developed a formula that takes into account information reported on the FAFSA—such as household income, certain available assets, and number of children in college—to determine an expected family contribution (EFC) toward college costs. A student’s financial need is the total cost of attendance (tuition and living costs combined) at a particular campus less his or her EFC.

Many Financial Aid Programs Available for California Students. Figure 5 shows the main aid programs available to undergraduates attending one of California’s public higher education segments. Most programs are need based and most provide gift aid. If a student qualifies for more than one program, then campus financial aid offices “package” together aid for the student. Generally, a student’s aid package cannot exceed his or her estimated college costs (tuition and living combined). When packaging aid, campuses first prioritize awarding gift aid before moving on to awarding loans and work study. Campuses do not award tax benefits. Students and parents claim these benefits on their tax returns.

Figure 5

Major Financial Aid Programs for Undergraduates

(In Billions)

|

Program |

Source |

Expendituresa |

|

Gift Aid |

||

|

Pell Grant |

Federal |

$3.0 |

|

Cal Grant |

State |

1.7 |

|

CCC Board of Governor’s Fee Waiver |

State |

0.8 |

|

UC Grant |

State |

0.8 |

|

CSU State University Grant |

State |

0.6 |

|

Supplemental Education Opportunity Grant |

Federal/state |

0.1 |

|

Middle Class Scholarship |

State |

—b |

|

CCC Full‑Time Student Success Grant |

State |

—b |

|

Subtotal |

($7.0) |

|

|

Loans |

||

|

Direct Student Loans |

Federal |

$1.7 |

|

Parent PLUS Loans |

Federal |

0.4 |

|

Perkins Student Loans |

Federal |

0.1 |

|

Subtotal |

($2.1) |

|

|

Tax benefits |

||

|

Tuition credits and deductions |

Federal |

$1.4c |

|

Coverdell education savings account |

Federal/state |

—b |

|

Scholarshare savings plan |

Federal/state |

—d |

|

Subtotal |

($1.4) |

|

|

Work study |

Federal/state |

$0.1 |

|

Total |

$10.6 |

|

|

a2014‑15 for federal programs and 2015‑16 for state programs. bLess than $50 million. cEstimated based on nationwide expenditures. dNot available. |

||

Cal Grant Program Is the State’s Largest Aid Program. The state’s Cal Grant program guarantees gift aid to California high school graduates and community college transfer students who meet both financial need and academic criteria. Students who do not qualify for one of these entitlement awards may apply for a limited number of competitive grants if they meet other eligibility criteria. Awards cover full systemwide tuition and fees at the public universities and up to a fixed dollar amount toward costs at private colleges. The program also offers $1,678 stipends (known as access awards) for some students. Access awards are intended to help cover some living expenses, such as the cost of books, supplies, and transportation. State spending on Cal Grants has increased from $813 million in 2007‑08 to an estimated $2 billion in 2016‑17, primarily due to sharp increases in the number of award recipients as well as increases in award amounts for students at the public universities.

State Recently Created Two New Aid Programs. The newest state program (created in 2015‑16) is the Full‑Time Student Success Grant—a grant that supplements the Cal Grant access award for CCC students who are enrolled in 12 or more units. The 2016‑17 budget provides $41.2 million for the program to increase the access award by $600—bringing the total access award for qualifying CCC students to $2,078. In 2014‑15, the state created Middle Class Scholarships. This program provides partial tuition coverage for certain UC and CSU students with household income and assets each less than $156,000.

Each Segment Also Offers Institutional Aid. In addition to Cal Grants and Middle Class Scholarships, UC and CSU operate institutional need‑based programs. UC and CSU pay for these programs largely by redirecting a portion of tuition revenue generated from full‑fee‑paying students. When packaging financial aid, UC first applies any applicable federal and state aid on a student’s behalf and assumes each student must contribute $9,700 through work and borrowing. It then uses institutional aid to fill any remaining gap between available resources and the total cost of attendance. About two‑thirds of UC’s institutional aid covers tuition, with the remaining one‑third paying for living costs. By comparison, CSU uses its State University Grant program only to cover tuition for certain students based on their federal expected family contribution. It does not cover other costs of attendance. At CCC, the Board of Governors Fee Waiver program fully covers enrollment fees (but not other costs of attendance) for financially needy students. Institutional need‑based gift aid spending ranges from $803 million at CCC to $764 million at UC to $607 million at CSU.

Half of Public College Students Pay No Tuition, Many Also Receive Gift Aid for Living Expenses. As evident from the above descriptions, most state aid programs are geared toward paying tuition. These programs collectively cover full tuition for around 60 percent of undergraduate students at UC and CSU. At CCC, 44 percent of students receive full fee waivers, paying for two‑thirds of all course units taken. In addition, the federal Pell Grant program and some state programs also pay for some or all of financially needy students’ living expenses. Taken altogether, gift aid for financially needy students cuts their total college costs (tuition and living expenses) in half at the universities. For full‑time students attending CCC, gift aid covers a somewhat lower portion of the cost of attendance—about one‑third.

About Half of University Students Borrow to Pay for College, Very Few CCC Students Borrow. Each year, around 40 percent of UC and CSU undergraduates take out loans, with an average annual loan amount of $6,800 per borrower. Slightly more than half of UC and CSU students have loan debt at graduation, with debt at graduation averaging $19,500. At CCC, only 2 percent of students borrow each year, with an average annual loan amount of $5,500. Student borrowing in California tends to be lower than in other states. For example, about 60 percent of students at four‑year public universities nationally graduate with loan debt, with an average debt load upon graduation of $25,900. (These figures only include student loans, not other forms of debt, such as credit card debt.)

Student Loan Default Rates Low at UC and CSU, Higher at CCC. About 95 percent of all borrowing at UC, CSU, and CCC is through federal loans. For each cohort of undergraduate borrowers entering repayment in a given year, the federal government tracks the percentage of students defaulting within three years, by institution. Three‑year student loan default rates tend to be low at UC and CSU but higher at CCC. Specifically, while no UC campus has a rate greater than 3.6 percent and no CSU campus has a rate greater than 6.7 percent, the vast majority of CCC campuses have rates in excess of 10 percent. The average rate for all institutions nationally is 11.3 percent.

Federal Loans Have Income‑Driven Repayment Plans. The most common type of federal loan—federal direct loans—currently offers new borrowers seven repayment plans. Four of these plans, known as income‑driven repayment plans, vary loan repayments based on the income of the borrower as a way to improve affordability and reduce the likelihood of a student defaulting. For example, the Pay As You Earn Repayment Plan (PAYE) caps monthly repayments at 10 percent of a borrower’s discretionary income (defined as income earned above 150 percent of the poverty level, adjusted for location and household size). Each of these four plans also forgives any remaining loan balances after a set period of repayment. For example, PAYE forgives balances after 20 years of repayment, or 10 years of repayment for eligible borrowers in public service careers.

Back to the TopPerformance

Below, we provide background on the state’s higher education goals and performance measures, review UC’s and CSU’s performance, and then assess CCC’s performance. We then discuss (1) replacing an existing performance measure and (2) potentially adding a new measure.

Background

State Has Set Forth Broad Goals for Higher Education. Chapter 367 of 2013 (SB 195, Liu) establishes three major goals for higher education: (1) improve student access and success, such as by increasing college participation and graduation rates; (2) better align degrees and credentials with the state’s economic, workforce, and civic needs; and (3) ensure the effective and efficient use of resources to improve outcomes and maintain affordability. To monitor progress toward these goals, the law calls for the creation and adoption of performance measures that take into account the distinct missions of California’s higher education segments. In addition, the law states the Legislature’s intent that progress on these measures be reported and considered as part of the state’s annual budget process.

State Has Adopted Performance Measures for Universities. Separate from Chapter 367, Chapter 50 of 2013 (AB 94, Committee on Budget) established eight specific performance measures for UC and CSU. The measures include graduation rates, degree completions, units accumulated upon graduation, and funding per degree. For most measures, the segments must track results for specified student subgroups, including low‑income students and transfer students. Chapter 50 requires the segments to submit related performance reports to the Legislature by March 15 each year.

State Requires Universities to Set Annual Performance Targets. Beginning with the 2014‑15 Budget Act, UC and CSU also are to submit performance reports (commonly referred to as “academic sustainability plans”) by November 30 each year. In these reports, UC and CSU are to set performance targets for each of the above‑referenced statutory measures for each of the coming three years. The plans include several years of actual performance on each of the measures. The Governor proposes to eliminate the requirement for the universities to submit these November reports. In the nearby box, we discuss and assess this proposal.

Universities’ November Performance Reports

The Governor proposes to eliminate the provisional budget language that requires UC and CSU to submit performance reports to the Legislature each November. Given that these plans provide key performance data—including former targets, actual results, and future targets—we recommend the Legislature reject this proposal. Should the Legislature wish to reduce the universities’ reporting workload, we recommend the Legislature eliminate the segments’ statutorily required March performance reports. The March reports contain the same past actual data as the November reports but, unlike the November reports, do not include the universities’ performance targets and certain other useful information.

State Also Requires CCC to Set Performance Targets. Chapter 687 of 2014 (SB 876, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) required the CCC Board of Governors to identify performance measures and develop annual performance targets that are “challenging and quantifiable.” The Board of Governors adopted systemwide measures and identified initial targets in July 2014. The systemwide measures come largely from CCC’s Student Success Scorecard, which was developed in 2012. The measures are tracked for a cohort of students over a six‑year period.

Some State Funding Provided in Recent Years to Boost Performance. To date, the state has not adopted a performance funding formula that adjusts funding based upon the segments’ or individual campuses’ performance. The state, however, has provided some funding in recent years intended to improve institutional performance. Most notably, the state increased CCC’s Student Success and Support Program from $49 million in 2012‑13 to $482 million in 2016‑17. In other cases, the segments have chosen to dedicate otherwise unallocated resources for student success initiatives. Most notably, CSU is dedicating $48 million of its unrestricted ongoing base budget to fund its Graduation Initiative, which aims to increase degree completion rates and eliminate achievement gaps over a multi‑year period. The 2016‑17 Budget Act includes an additional $35 million one time for CSU to further the objectives of the Graduation Initiative.

Review of Universities’ Performance

To date, the universities have submitted three annual reports to the Legislature under the new requirements. Based on data from those plans, this section highlights UC’s and CSU’s performance results compared with their targets. Specifically, Figure 6 displays UC’s initial targets for 2015‑16, actual results, and new targets for 2019‑20. Figure 7 provides the same information for CSU.

Figure 6

UC’s Performance Measures and Targets

|

State Performance Measure |

Target for 2015‑16 |

Actual 2015‑16 Performance |

Target for 2019‑20 |

|

CCC Transfers Enrolled. Number and as a percent of undergraduate population. |

33,904 (18%) |

34,197 (18%) |

37,589 (18%) |

|

Low‑Income Students Enrolled. Number and as a percent of total student population. |

71,462 (39%) |

75,608 (40%) |

82,359 (40%) |

|

Graduation Rates |

|||

|

63% |

64% |

68% |

|

57% |

58% |

62% |

|

55% |

55% |

59% |

|

51% |

51% |

55% |

|

Degree Completions. Number of degrees awarded annually to: |

|||

|

34,200 |

34,519 |

39,756 |

|

14,600 |

14,866 |

16,396 |

|

18,600 |

14,497 |

15,580 |

|

21,800 |

24,660 |

28,017 |

|

69,100 |

63,882 |

73,181 |

|

First‑Year Students on Track to Graduate on Time. Percentage of first‑year undergraduates earning enough credits to graduate within four years. |

51% |

52% |

52% |

|

Funding Per Degree. State General Fund and tuition revenue divided by number of degrees for: |

|||

|

$107,771 |

$111,328 |

$126,029 |

|

Not reported |

Not reported |

$74,981 |

|

Units Per Degree. Average quarter units earned at graduation for: |

|||

|

187 |

183 |

183 |

|

100 |

95 |

95 |

|

Degree Completions in STEM Fields. Number of STEM degrees awarded annually to: |

|||

|

17,100 |

20,503 |

23,382 |

|

9,300 |

8,620 |

9,264 |

|

7,100 |

9,284 |

10,549 |

|

CCC = California Community Colleges and STEM = science, technology, engineering, and math. Source: UC Academic Sustainability Plans. |

|||

Figure 7

CSU’s Performance Measures and Targets

|

State Performance Measure |

Target for 2015‑16 |

Actual 2015‑16 Performance |

Target for 2019‑20 |

|

CCC Transfers Enrolled. Number and as a percent of undergraduate population. |

145,436 (36%) |

143,445 (36%) |

144,879 (36%) |

|

Low‑Income Students Enrolled. Number and as a percent of total student population. |

207,528 (50%) |

206,926 (50%) |

218,948 (51%) |

|

Graduation Rates |

|||

|

18% |

19% |

24% |

|

11% |

12% |

19% |

|

54% |

57% |

62% |

|

47% |

52% |

57% |

|

28% |

31% |

36% |

|

26% |

30% |

36% |

|

65% |

62% |

69% |

|

64% |

62% |

69% |

|

Degree Completions. Number of degrees awarded annually to: |

|||

|

37,915 |

38,770 |

47,803 |

|

43,152 |

47,034 |

51,415 |

|

18,938 |

20,788 |

22,248 |

|

40,482 |

51,226 |

64,080 |

|

106,788 |

112,832 |

127,706 |

|

First‑Year Students on Track to Graduate on Time. Percentage of first‑year undergraduates earning enough credits to graduate within four years. |

51%a |

52%a |

57%a |

|

Funding Per Degree. State General Fund and tuition revenue divided by number of degrees for: |

|||

|

$41,049 |

$40,781 |

$42,789 |

|

$51,670 |

$49,991 |

$46,780 |

|

Units Per Degree. Average semester units earned at graduation for: |

|||

|

139 |

138 |

138 |

|

140 |

141 |

141 |

|

Degree Completions in STEM Fields. Number of STEM degrees awarded |

|||

|

18,846 |

20,201 |

26,994 |

|

3,958 |

5,693 |

7,453 |

|

7,470 |

10,462 |

13,927 |

|

aCSU excludes students who do not return to CSU for their second year. Including these students reduces CSU’s performance by about 8 percentage points. CCC = California Community Colleges and STEM = science, technology, engineering, and math. Source: CSU Academic Sustainability Plans. |

|||

UC and CSU Met Their Targets for Graduation Rates for Freshmen And Have Raised Their Targets. Both UC and CSU have exceeded slightly their original targets for four‑year graduation rates for freshmen (for all freshman entrants as well as low‑income freshman entrants). Specifically, both segments ended up 1 percentage point higher than their original targets. For its six‑year graduation rate for freshman entrants, CSU surpassed its target of 54 percent, graduating 57 percent of its students. Both segments have set higher targets for 2019‑20. Figure 8 shows that the universities’ recent improvement is part of a long‑term trend of gradually increasing graduation rates.

Targets for Graduation Rates for Transfer Students Mostly Met. A two‑year graduation rate for transfer students is analogous to a four‑year graduation rate for entering freshmen. Both UC and CSU either met or exceeded their original targets for two‑year graduation rates for CCC transfer students. The two‑year graduation rate for transfer students at UC has increased from 46 percent a decade ago to 55 percent today. The two‑year rate at CSU has increased from 21 percent to 31 percent over the same period. CSU did not meet its target for the three‑year graduation rate for transfer students (analogous to a six‑year graduation rate for freshmen entrants)—aiming for 65 percent but falling short at 62 percent. As with the graduation targets for freshmen entrants, both segments have set higher out‑year graduation targets for transfer students.

Excess Units Remain a Concern for CSU. Both university systems must track the number of units students have accumulated upon graduation. UC did better than its 2015‑16 target. UC’s 2015 graduating class (consisting of those who began as freshmen as well as transfer students) accumulated an average of four quarter units (one typical course) beyond the typical 180 quarter unit degree requirement. CSU also did better than its 2015‑16 target for entering freshmen. The average number of units accumulated upon graduation, however, was still 18 semester units (six courses) beyond the typical unit degree requirements. Moreover, CSU saw no reduction in accumulated units for students starting as transfers. Despite considerable efforts by the Legislature to improve the transfer process, transfer students who graduated from CSU during the 2015‑16 academic year accumulated an average of 141 semester units—21 semester units (seven courses) beyond the typical semester unit degree requirement.

Review of CCC’s Performance

Below, we review data on key community college performance outcomes and provide a recommendation relating to CCC’s performance measurement system.

At CCC, Rate of Students Progressing From Remedial to College‑Level Courses Improving . . . For CCC, one of the most important “milestone” performance measures is the percentage of students initially placed into precollegiate coursework that end up later passing college‑level math and English courses. Over time, CCC has improved slightly in this area. For remedial math, its progress rate has gone from 29 percent in 2010‑11 to 33 percent in 2014‑15. Progress rates for remedial English have increased from 42 percent to 45 percent over the same period.

. . . But Program Completion Rates Declining Slightly. Though a somewhat greater percentage of students are advancing from remedial courses through college‑level math and English courses, CCC program completion rates have been declining slightly in recent years. Program completion rates peaked at 49 percent in 2011‑12, dipping to 47 percent for 2014‑15. Completion rates decreased both for entering students that were initially assessed as underprepared and assigned to remedial courses, as well as students who were deemed prepared for college‑level coursework.

CCC’s Approach to Setting and Reporting Completion Targets Is Problematic. Figure 9 shows the CCC system’s performance measures. The targets for the first three performance measures cannot be displayed easily. This is because CCC does not set a single target for an incoming cohort of students to complete a program within a set period of time (the methodology that UC and CSU use). Furthermore, CCC rebenches those targets annually based on each cohort’s latest performance. As a result, CCC’s approach can lead to counterintuitive outcomes, such as the system meeting its target even as a cohort of students performs worse than prior cohorts.

Figure 9

CCC’s Performance Measures and Targets

|

Performance Measure |

Target for 2014‑15 |

Actual 2014‑15 Performance |

Target for 2015‑16 |

|

Completion Rate. First‑time students who completed a degree, certificate, 60 transferrable units, or transferred within 6 years of entry. |

—a |

47.1% |

—a |

|

Remedial Progress Rate. Students enrolling in remedial math or English or precollegiate English as a second language (ESL) who completed a college‑level course in that discipline within 6 years. |

—a |

33% in math 45% in English 29% in ESL |

—a |

|

CTE Completion Rate. CTE students who completed a degree, certificate, 60 transferable units, or transferred within 6 years of entry. |

—a |

51.4% |

—a |

|

Associate Degrees for Transfer. Number of these degrees completed annually. |

12,020 |

20,737 |

21,774 |

|

Equity Rate. Index showing whether a subgroup’s completion rate is low compared with overall completion rate. An index of less than 1.0 indicates underperformance. |

|||

|

African American |

0.79 |

0.75 |

Increase above 0.75 |

|

American Indian |

0.73 |

0.88 |

Stay above 0.8 |

|

Asian |

Stay above 0.8 |

1.31 |

Stay above 0.8 |

|

Hispanic |

Stay above 0.8 |

0.84 |

Stay above 0.8 |

|

Pacific Islander |

Stay above 0.8 |

0.81 |

Stay above 0.8 |

|

White, Non‑Hispanic |

Stay above 0.8 |

1.09 |

Stay above 0.8 |

|

Education Plan Rate. Percent of required students who have an education plan. |

Not reported |

57% |

Above 57% |

|

FTE Years Per Completion. A measure of efficiency showing amount of instruction, on average, required for each completion. (A student completing 60 units, the standard length of an associate degree or preparation for transfer, would generate two FTE years.) |

|||

|

Assessed as underprepared |

Below 5.3 |

4.98 |

Stay below 4.98 |

|

Assessed as prepared |

Below 2.85 |

2.72 |

Stay below 2.72 |

|

Overall |

Below 4.39 |

4.15 |

Stay below 4.15 |

|

Participation Rate. Number of students ages 18‑24 attending a community college per 1,000 California residents in the same age group. |

Above 264.7 |

266.6 |

Above 266.6 |

|

Participation Among Subgroups. Index comparing a subgroup’s share of enrollment with its share of the state population. An index of less than 1.0 indicates underrepresentation. |

|||

|

African American |

Stay above 0.8 |

0.9 |

Stay above 0.8 |

|

American Indian |

0.8 |

0.8 |

Stay above 0.8 |

|

Asian |

Stay above 0.8 |

1.19 |

Stay above 0.8 |

|

Hispanic |

Stay above 0.8 |

1.06 |

Stay above 0.8 |

|

Pacific Islander |

Stay above 0.8 |

1.10 |

Stay above 0.8 |

|

White, Non‑Hispanic |

Stay above 0.8 |

0.82 |

Stay above 0.8 |

|

aCCC is unable to provide this information. CTE = career technical education and FTE = full‑time equivalent. |

|||

For Other Performance Measures, CCC Has Set Very Low Bar. Though we were unable to display CCC’s three completion‑related performance measures, Figure 9 shows the six other measures that community colleges use. CCC’s targets for several of these measures are underwhelming as well as inconsistent with both legislative intent and the Board of Governors’ own policy on significantly improving outcomes. For example, in 2014‑15, 57 percent of students who were required to develop an education plan actually had one a year after enrolling. The Board of Governors’ expressed goal is for 100 percent of nonexempt students to have an education plan soon after enrolling. Nonetheless, for 2015‑16, CCC’s target is only to increase—by any amount—above 57 percent. Given the significant recent investments by the Legislature in student support services and the Board of Governors’ own policy, we think this target is much too low. Similarly, CCC students on average generate just over four FTE years to complete an associate degree or certificate or prepare for transfer. CCC’s target is to reduce this amount to four FTE years or less. Given that a student completing 60 units (the standard length of an associate degree) would generate two FTE years, we believe such a target is not sufficiently ambitious.

Recommend Legislature Direct CCC to Revise Performance Measurement System. To promote greater transparency and more challenging targets for CCC, we recommend the Legislature direct the Chancellor’s Office to redesign its performance measurement system. The new system should include performance targets that are clear and understandable and do not change for a given cohort as it moves through a program. Also, consistent with legislative intent, CCC should set challenging targets for all of its metrics. In addition, as part of its review and redesign, the Chancellor’s Office should consider adding shorter cohort periods (such as two years and three years) for its completion and remedial rate metrics. The current amount of time a cohort is tracked (over a six‑year period) results in a long lag time that makes it difficult to assess the extent to which the Legislature’s recent investments in CCC are affecting student outcomes.

A Modified Efficiency Measure

Funding Per Degree Does Especially Poor Job Measuring Efficiency. Among UC’s and CSU’s eight statutory performance measures, two of them—units accumulated per degree and funding per degree—are intended to focus on efficiency. By tracking how many excess units students take, we think units per degree is a useful and meaningful measure of efficiency. In contrast, funding per degree has no obvious nexus with efficiency. Worse, as implemented to date, the measure seems to be promoting inefficiency, as both UC and CSU have set out‑year targets to increase their funding per degree. Moreover, neither segment thinks the measure is useful.

Recommend the Legislature Work With UC and CSU to Develop a More Meaningful Efficiency Measure. For these reasons, we recommend the Legislature adopt trailer legislation replacing funding per degree with a more meaningful efficiency measure. To develop a more meaningful measure, we recommend the Legislature work with the segments and Department of Finance this spring to explore alternatives. Reasonable alternatives could include using data the segments already report to create a cost per student or cost per degree measure. In exploring a new measure, the Legislature also might consider involving CCC in its discussions and applying the new measure to that segment too.

A New Higher Education Performance Measure

State Law Indicates Intent to Track Graduates’ Outcomes. In articulating broad statewide goals for higher education, Chapter 367 identifies greater participation by low‑income students, higher completion rates for all students, and improved outcomes for graduates as important components of student access and success. While each segment has performance measures related to college participation and graduation, none of the segments’ currently adopted measures assesses how graduates do once they leave college and enter the workforce.

Consider Adding a Measure of Graduates’ Outcomes. Measuring students’ outcomes once they graduate from college could give the Legislature a fuller picture of the extent to which the state’s higher education system is meeting workforce needs and adding value to students. One possible new measure could track earnings of graduates by segment and campus. (The CCC Chancellor’s Office already operates a system‑level data system that reports earnings gains of recent graduates by program.) Another possible measure could track income mobility by segment and campus. A recent national study, for instance, has investigated the extent to which particular colleges and universities in the country serve students from lower‑income brackets who, over time, move into higher‑income brackets. We recommend the Legislature direct the three public higher education segments to report at spring budget hearings on potential measures of graduates’ outcomes, including the feasibility of adding an earnings or income mobility indicator.

Back to the TopUniversity of California

In this section, we provide an overview of UC’s budget, describe UC’s spending plan, assess that plan, and make associated recommendations. At the end of the section, we summarize UC’s new capital outlay requests.

Overview

Governor’s Budget Proposes Nearly $33 Billion From All Sources for UC in 2017‑18. As Figure 10 shows, UC’s total budget would increase by $839 million (2.6 percent) over the 2016‑17 level. About one‑quarter ($8.4 billion) of UC’s total funding consists of “core funds” (primarily state General Fund and student tuition revenue) that support the university’s undergraduate and graduate education programs. Core funding would increase by $191 million (2.3 percent). The remainder of UC funding comes primarily from its five medical centers, sales and services (including housing, bookstores, and academic extension), and the federal government (primarily for research and financial aid).

Figure 10

University of California Funding by Source

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2015‑16 Actual |

2016‑17 Revised |

2017‑18 Proposed |

Change Over 2016‑17 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Core Funds |

|||||

|

General Fund—ongoing |

$3,135 |

$3,279 |

$3,362 |

$83 |

2.5% |

|

General Fund—one time |

124 |

262 |

169 |

‑93 |

‑35.0 |

|

Subtotals |

($3,259) |

($3,541) |

($3,531) |

(‑$10) |

(‑0.3%) |

|

Resident tuition and fees |

$3,211 |

$3,371 |

$3,449 |

$78 |

2.3% |

|

Nonresident supplemental tuition |

833 |

976 |

1,050 |

74 |

7.6 |

|

Subtotals |

($4,044) |

($4,347) |

($4,499) |

($152) |

(3.5%) |

|

Lottery |

$38 |

$36 |

$36 |

— |

— |

|

Othera |

318 |

286 |

334 |

$49 |

17.1% |

|

Totals—Core Funds |

$7,660 |

$8,209 |

$8,401 |

$191 |

2.3% |

|

Other Funds |

|||||

|

Medical centers |

$9,467 |

$9,751 |

$10,044 |

$293 |

3.0% |

|

Sales and services |

6,045 |

6,308 |

6,497 |

189 |

3.0 |

|

Federal |

3,920 |

3,994 |

3,988 |

‑6 |

‑0.2 |

|

Privateb |

2,055 |

2,149 |

2,234 |

85 |

4.0 |

|

State special funds |

26 |

59 |

106 |

47 |

80.0 |

|

Other |

1,400 |

1,451 |

1,490 |

40 |

2.7 |

|

Totals |

$22,913 |

$23,711 |

$24,359 |

$648 |

2.7% |

|

Grand Totals |

$30,573 |

$31,921 |

$32,760 |

$839 |

2.6% |

|

aIncludes a portion of overhead funding on federal and state grants and a portion of patent royalty income. Also includes $50 million in funding freed up for core purposes by Proposition 56 funds. bConsists of private gifts and endowment earnings. |

|||||

Governor’s Budget Proposes $3.5 Billion General Fund Support for UC in 2017‑18. Figure 11 shows the proposed General Fund changes to UC’s budget in 2017‑18. The budget contains an $81 million (2.5 percent) unrestricted ongoing base increase and a $2 million ongoing increase for a specified medical program originally funded in the 2015‑16 budget. In addition, the Governor proposes to provide $169 million one time to help UC pay down its unfunded pension liability. The state provided $262 million in one‑time funding to UC in 2016‑17, including $171 million for the system’s pension liabilities. After factoring in all these adjustments, UC’s total General Fund appropriation would decline by $10 million (0.3 percent).

Figure 11

2017‑18 University of California General Fund Changes

(In Millions)

|

2016‑17 Revised Funding |

$3,541 |

|

Pay down unfunded pension liability (one time) |

$169 |

|

Provide unrestricted base increase (ongoing) |

81 |

|

Resume funding for medical education program (ongoing) |

2 |

|

Remove prior‑year one‑time funding |

‑262 |

|

Total Changes |

‑$10 |

|

2017‑18 Proposed Funding |

$3,531 |

Governor’s Budget Also Redirects $50 Million Freed Up From Proposition 56 Funds. Approved by voters in November 2016, Proposition 56 imposes new taxes on tobacco products and specifies the use of the resulting revenue. Among its numerous provisions, the law requires the state to allocate funding to UC for graduate medical education. To implement this provision, the Governor proposes to designate $50 million in Proposition 56 funding for graduate medical education and free up a like amount of existing state General Fund for other UC priorities. Under the proposal, the mix of funding for graduate medical education would change, but the overall funding level for graduate medical education would remain the same. The Governor describes the ultimate effect of this fund swap as providing the university with a total unrestricted base augmentation of $131 million (4 percent) in the budget year. The nearby box provides further information on UC‑related provisions in Proposition 56.

Proposition 56 Allocations to UC

Proposition 56 includes funding for two UC purposes, as described below.

Graduate Medical Education. The measure specifies that $40 million in Proposition 56 tax revenue is to go to UC for graduate medical education. Specifically, the measure indicates the funds are to “sustain, retain, and expand graduate medical education programs.” The measure further specifies that the funds are “for the purpose and goal of increasing the number of primary care and emergency physicians trained in California.” To this end, the measure requires UC to assess annually whether there are regional or statewide shortages of physicians for specific specialties (such as surgery or neurology). To the extent a demonstrated shortage of specialty physicians exists, UC may use funding to expand graduate medical education programs in those specialty areas. The measure does not explicitly prohibit UC from swapping out existing funding for graduate medical education with Proposition 56 funds. (Because the measure does not take effect until April 2017, UC would receive $10 million in 2016‑17. The Governor proposes carrying forward this amount, for total funding of $50 million in 2017‑18.)

Tobacco‑Related Disease Research. After covering various specified costs under the measure, Proposition 56 designates 5 percent of remaining tax proceeds be given to UC for tobacco‑related disease research. Prior to Proposition 56, some tax proceeds on tobacco products already were directed to tobacco‑related disease research administered by UC (which, in turn, provides grants to researchers throughout the state). Proposition 56 augments funding for this research. In 2017‑18, the Governor budget’s includes $81 million in Proposition 56 funds for this purpose. (Similar to the other UC‑related item, this amount includes an estimated $16 million carried forward from 2016‑17.) Unlike its provision for graduate medical education, Proposition 56 expressly prohibits UC from using this funding to supplant existing tobacco‑related disease research funding.

Governor’s Budget Assumes UC Will Receive $18.5 Million in 2016‑17 for Enrollment Growth in 2017‑18. The 2016‑17 Budget Act provides $18.5 million for UC to enroll 2,500 more resident undergraduate students in 2017‑18, a 1.4 percent increase over the estimated 2016‑17 level. To receive this funding, UC must meet two requirements by May 1, 2017: (1) provide evidence that it is on track to meet this enrollment expectation and (2) adopt a policy that limits nonresident enrollment. The Department of Finance assumes UC will meet these requirements and includes release of the enrollment funding as part of its budget plan. Because the amount provided in 2016‑17 would be released to UC in May or June 2017, UC intends to carry forward this amount into 2017‑18.

Governor’s Budget Does Not Assume Resident Tuition Increases. Though the administration does not assume tuition increases for resident students, the budget reflects 5 percent increases in both the Student Services Fee (charged to all students) and the undergraduate nonresident supplemental tuition charge. Coupled with assumptions about enrollment growth in 2017‑18, the budget assumes associated year‑over‑year increases of $152 million from tuition and fees.

UC Has Identified Additional Funding It Plans to Use in 2017‑18. Beyond the $191 million increase in core funding recognized in the Governor’s budget, UC has identified an additional $114 million as available in 2017‑18. Of the $114 million, $74 million is associated with tuition increases. In January 2017, the Board of Regents approved increases in resident tuition charges. Under this action, students will pay $11,502 in tuition in 2017‑18, a $282 (2.5 percent) increase over the 2016‑17 level. The board also identified $40 million in savings and redirected revenues. Specifically, UC indicates this funding consists of: (1) $14 million from phasing out financial aid for nonresident students, (2) $10 million in philanthropic donations, (3) $8 million in savings from improved procurement practices, (4) $5 million in savings from self‑insuring for certain risks, and (5) $3 million in new revenue from increased investment returns. Except for phasing out nonresident aid, which the state called for in the 2015‑16 budget, the revenues are the result of UC initiatives.

UC’s Spending Plan

In January 2017, the Regents adopted a core budget plan for 2017‑18. The plan incorporates the Governor’s General Fund proposal, as well as other core funds (including proposed tuition increases, nonresident enrollment growth, and savings) available for the university system to spend. After factoring in all of these available revenues, UC plans to increase ongoing spending by $412 million in 2017‑18. Figure 12 displays the elements of the plan. We describe each element below.

Figure 12

UC’s Spending Plan for 2017‑18a

(In Millions)

|

Increase |

|

|

Compensation |

|

|

General salary increasesb |

$112 |

|

Faculty merit increases |

32 |

|

Health benefit cost increases |

19 |

|

Pension cost increases |

18 |

|

Retiree health benefit cost increases |

8 |

|

Subtotal |

($189) |

|

Undergraduate Enrollment Growth |

|

|

Resident students (1.4 percent) |

$45 |

|

Nonresident students (3 percent) |

16 |

|

Subtotal |

($62) |

|

Academic Excellence |

$50 |

|

Financial Aid |

$49 |

|

Facilities |

|

|

Deferred maintenance |

$15 |

|

Debt service for previously approved projects |

15 |

|

Subtotal |

($30) |

|

Other |

|

|

Operating expenses and equipment |

$27 |

|

Student mental health |

5 |

|

Subtotal |

($32) |

|

Total |

$412 |

|

aExcludes spending items that assumed additional state funding above the Governor’s proposal. bIncludes a 3 percent increase for faculty and unrepresented staff and a 3.9 percent increase for represented staff. |

|

Designates $189 Million for Compensation Cost Increases. Nearly half of UC’s spending plan is for employee compensation increases. Of the total proposed compensation increase, $112 million would provide a 3.2 percent general salary increase for faculty and staff. In addition to this general salary increase, UC budgets $32 million to provide merit salary increases for tenure‑track faculty. UC also recognizes increases in health benefit and pension costs.

Builds In $62 Million for Resident and Nonresident Enrollment Growth. Consistent with state expectations, UC plans to spend $45 million to enroll 2,500 more resident undergraduate students in 2017‑18. Spending on resident enrollment growth is based on the marginal cost of education, which UC calculates to be $18,146 in 2017‑18. UC plans to spend an additional $16 million to enroll 1,000 (3 percent) more nonresident undergraduate students in 2017‑18. Nonresident enrollment growth would be funded from the base tuition charged to these students as well as a portion of nonresident supplemental tuition revenue.

Provides $50 Million for UC’s Academic Excellence Initiative. This proposal would continue past initiatives by UC to enhance funding for its instructional and research programs. Similar to these past initiatives, campuses would have discretion to set their own priorities for these monies. UC anticipates campuses would use the funds for a broad range of purposes, including reducing the student‑faculty ratio at certain campuses, providing additional start‑up research funding for new faculty, increasing stipends for graduate students, better maintaining facilities, and replacing more equipment.

Increases Financial Aid by $49 Million. Consistent with longstanding practice, UC plans to increase financial aid spending by redirecting a portion of tuition revenue to need‑based institutional aid. This increase is derived from (1) $26 million from tuition increases, (2) $18 million from increased tuition revenues generated from enrollment growth, and (3) $5 million from the Student Services Fee increase.

Augments Facility Spending by $30 Million. UC proposes spending $15 million on deferred maintenance projects. The university system also plans to spend $15 million to cover debt service payments on previously approved capital outlay projects.

Provides $27 Millionfor Operating Expenses and Equipment. UC annually budgets for various cost increases that are separate from employee compensation, such as instructional equipment, library materials, and utilities. In 2017‑18, UC estimates spending about $27 million (2.5 percent) more on these costs.

Provides $5 Million for Student Mental Health. In 2015‑16, UC adopted a plan to allocate a portion of Student Services Fee revenue to augment mental health services for students. In 2017‑18, UC anticipates a $4.6 million increase for this program.

Back to the TopAssessment

UC’s Spending Plan Raises Several Issues for the Legislature. We think the Governor’s funding plan and UC’s spending plan is a mixed bag, with some components more warranted than other components. Below, we provide our assessment of several key budget components—compensation, resident enrollment, nonresident enrollment, and academic excellence. (We assess the Governor’s Proposition 56 funding proposal, including his proposal regarding graduate medical education, in a separate publication.)

Compensation

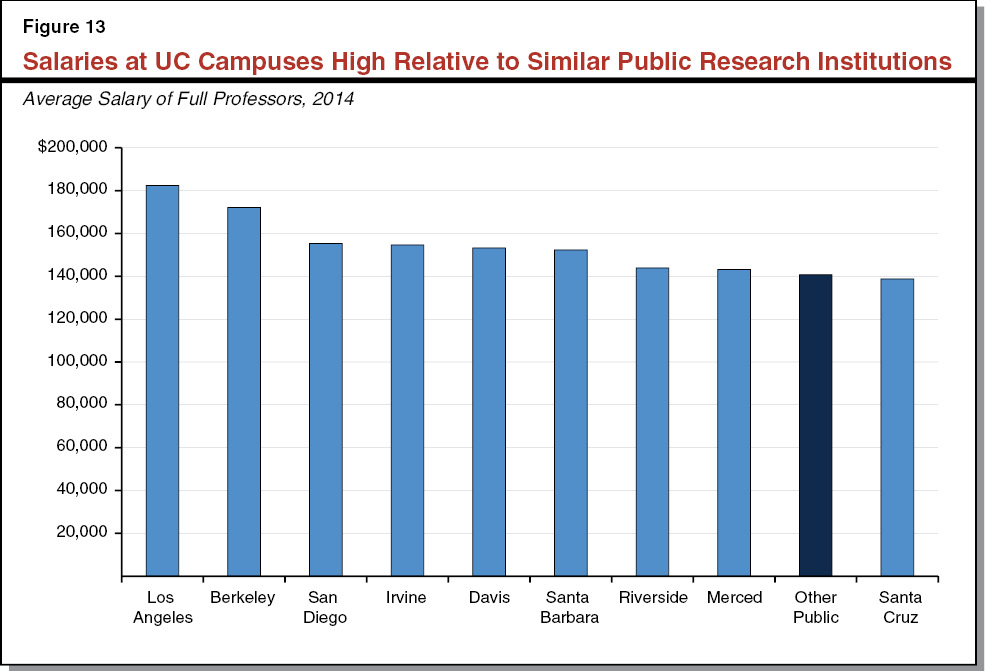

Employee Compensation Is UC’s Largest Expense. Similar to most state agencies, employee compensation is UC’s largest cost, accounting for over 80 percent of its core budget. Employees funded from UC’s core budget include faculty, staff, and administrators.