LAO Report

March 2, 2017The 2017-18 Budget

Governor’s Gann Limit Proposal

- Introduction

- History of the Gann Limit

- How the State Appropriations Limit Works

- How Gann Limit Works for School Districts

- Governor’s Proposal

- Assessment

- Recommendation

- LAO Calculation of SAL

- Conclusion

- Appendix

Executive Summary

Voters Passed Gann Limit in 1979 to Constrain Government Spending. In the wake of Proposition 13 (1978)—the landmark initiative that limited local property taxes—voters passed another measure that limited the spending side of government operations. Proposition 4 (1979) amended the State Constitution to impose spending limits—technically, appropriations limits—on the state and most local governments. The limits are sometimes referred to as “Gann limits” in reference to one of the measure’s coauthors, Paul Gann. The fundamental purpose of the limits was to keep inflation‑ and population‑adjusted appropriations under the 1978‑79 level. The measure required revenues in excess of the limit to be rebated to taxpayers.

Gann Limit a Big Factor in Budgeting Until Proposition 111 (1990) Reduced Its Effects. The state’s appropriations limit, or SAL, was a significant factor in state budgeting during the 1980s. In fact, the state had revenues in excess of its SAL in 1986‑87 and was required to rebate $1.1 billion to taxpayers (equal to over $2 billion in today’s dollars). Proposition 111 made several changes to the Gann Limit that reduced its effects on state and local budgeting. The measure required excess revenues to be determined over a two‑year period rather than in a single year, making excess revenues less likely. The measure also changed the population and inflation growth factors in a way that created more “room” under the limit. Since passage of Proposition 111, the SAL has rarely affected state budgeting.

Governor Proposes to Not Count $22 Billion Under Gann Limit. Not mentioned in the Governor’s 2017‑18 budget summary is a proposal to adopt a new SAL calculation methodology. Essentially, the Governor proposes to no longer count $22 billion of school‑related spending toward the state’s appropriations limit. As the Governor is not proposing to count these funds toward local limits, this means that the Governor does not count the funds anywhere under Gann Limit calculations. In effect, the funds become “nowhere money” under the calculations.

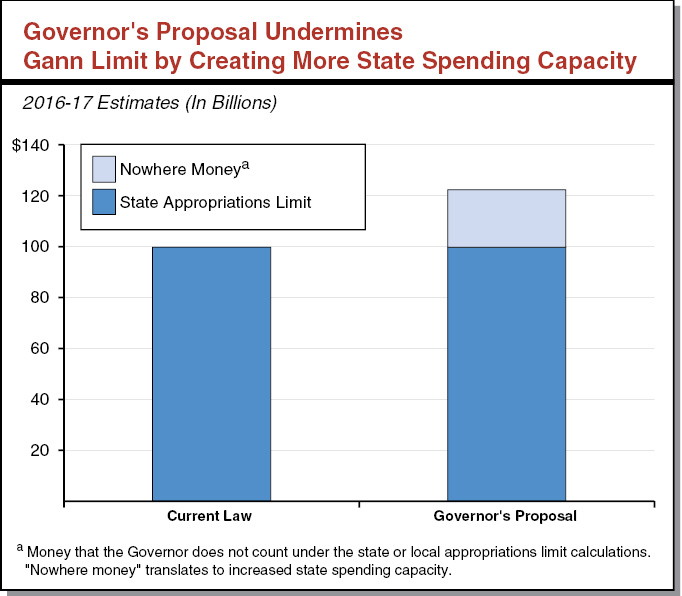

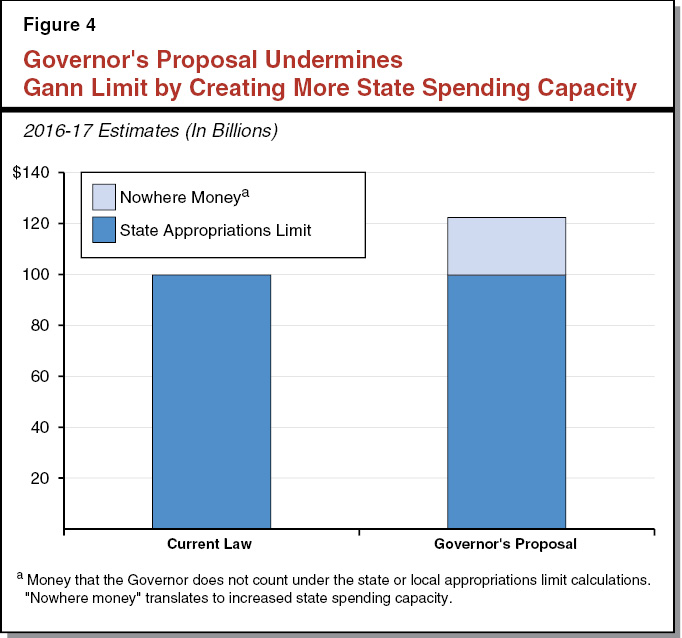

Proposal Creates $22 Billion in New State Spending Capacity. A core principle of the Gann Limit is that spending from tax revenues must be counted at either the state or local level (unless specifically exempted under the Constitution). If such spending is unaccounted for, appropriations can be greater than intended under the Gann Limit. The figure below shows the effect of the Governor’s proposal. By not counting $22 billion in spending toward the limit (labeled “nowhere money” in the figure), the Governor frees up a like amount of room—essentially new state spending capacity under the Gann Limit.

Governor’s Proposal Violates Spirit of the Gann Limit. The Governor’s proposal contradicts long‑standing policies regarding the implementation of the Gann Limit. Keeping spending under the 1978‑79 level was the fundamental purpose of Proposition 4. By not counting $22 billion in spending toward the limit, the Governor’s proposal allows for more government spending capacity than the 1978‑79 level, thus violating the spirit of Proposition 4. Accordingly, we believe that the plan would be highly vulnerable to legal challenges. We recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal and direct the administration to produce SAL calculations for the 2017‑18 budget using their prior methodology.

Gann Limit Now Appears to Be a Real Budget Constraint. In this report, we offer our own SAL calculations using the administration’s prior methodology. We find that the state has only a few billion dollars of room under the SAL. While the Gann Limit has not been a focus of budgetary discussions for some time, this finding is not entirely unexpected, as state room under the SAL tends to shrink as economic expansions persist. In addition, we identify issues outside of the Governor’s proposal that—if addressed—would further erode room under the SAL. Furthermore, if revenues increase in the May Revision or the Legislature approves additional tax levies, the state could find itself on the brink of exceeding the SAL.

Options for Legislative Consideration. Should this scenario come to pass, there are a few options for the Legislature to consider. First, the Legislature could do nothing, in which case excess revenues over two consecutive years would be divided between Proposition 98 spending and taxpayer rebates. Second, the Legislature could reduce taxes either through lower rates or increased tax credits or deductions. Third, the Legislature could shift appropriations from items subject to the SAL to purposes that are exempt from the limit. These include debt service; certain capital outlay projects; and funding for cities, counties, and certain special districts (to the extent these local governments have room under their limits). Finally, other options exist to shift up to several billion dollars in room from school and community college districts to the state without violating the spirit of the Gann Limit. (We note that such actions could be designed to hold districts harmless.) While these options could relieve some pressure on state budgeting, the gain to the state would be far smaller than under the Governor’s proposal, meaning the SAL could constrain state budgeting at least in the near future.

Introduction

In the late 1970s, voters passed two major initiatives that constrained government operations: Proposition 13 (1978) and Proposition 4 (1979). Proposition 4 added Article XIII B to the State Constitution, which established an appropriations limit on the state and most types of local governments. These limits are also referred to as “Gann limits” in reference to one of the measure’s coauthors, Paul Gann.

The fundamental purpose of the Gann Limit—described in Section 1 of the measure—was to keep real (inflation adjusted) per person government spending under 1978‑79 levels. While the Gann Limit has been a nonfactor for state finances in recent years, “room” under the limit—available spending capacity for the state’s tax‑supported funds—has been shrinking. The Governor’s 2017‑18 budget proposes a new interpretation of the Gann Limit that allows for significantly more state spending capacity. The new interpretation would change long‑standing methods used to calculate the Gann Limit.

This report provides our assessment of the Governor’s proposal. First, we provide background on the Gann Limit, including a discussion of its history and explanation of the complex calculations required by Proposition 4. We then describe the Governor’s proposal. Finally, we provide our assessment of the proposal and recommendations.

Back to the TopHistory of the Gann Limit

California in the Late 1970s. During the late 1970s, the state amassed large budget surpluses. Over a few fiscal years, revenues significantly exceeded spending, and the state effectively held much of this excess in reserves as opposed to spending the funds or returning them to taxpayers. In 1977‑78, the state had a reserve equal to over $11 billion in today’s dollars, or nearly 20 percent greater than total reserves proposed by the Governor in the 2017‑18 budget. Unlike California’s recent budgeting experience—in which the state’s elected leaders and voters have prioritized reserves, including the 2014 passage of Proposition 2—many at that time viewed the surpluses negatively. Some believe they contributed to voters approving Propositions 13 and 4.

Proposition 13 Limited Property Taxes. In 1978, voters passed Proposition 13, the landmark decision to limit property taxes. The measure had a profound effect on state and local government. Local property tax revenues dropped by about 60 percent immediately following the measure, the state was given the responsibility of allocating local property taxes among local governments, and the state took various actions to provide fiscal relief to local governments.

Proposition 4 Limited Government Spending. In Proposition 13’s wake, voters approved Proposition 4 in 1979. This measure amended the Constitution to impose an appropriations limit on the state and most local governments. The fundamental purpose of the appropriations limit is to keep real per capita government spending under the 1978‑79 level. It did this by requiring a complex set of calculations to be performed each year to compare appropriations to the limit. If the state has revenues that cannot be appropriated because of the limit—meaning the state has “excess revenues”—the measure required the excess revenues to be returned to taxpayers. (Proposition 4 also required the state to reimburse local governments for state‑imposed mandates, but the administration’s proposal does not affect the mandate‑reimbursement process.)

Legislature Faced Decisions in Implementing the Measure. The Gann Limit was intended to constrain spending by the state and well over 1,000 local governments. To accomplish this, Proposition 4 used general, rather than specific, language requiring the Legislature to interpret parts of the measure in its implementation. Moreover, the Legislature was given the responsibility to define some aspects of the measure, including the measure of population used for purposes of adjusting the appropriations limits. (We described these numerous choices in our December 1979 report, An Analysis of Proposition 4: The Gann “Spirit of 13” Initiative.) As we describe later in this report, the Legislature implemented the measure to minimize the effect on school districts. (In this report, we use the term “school district” to encompass school districts, community college districts, and county offices of education.)

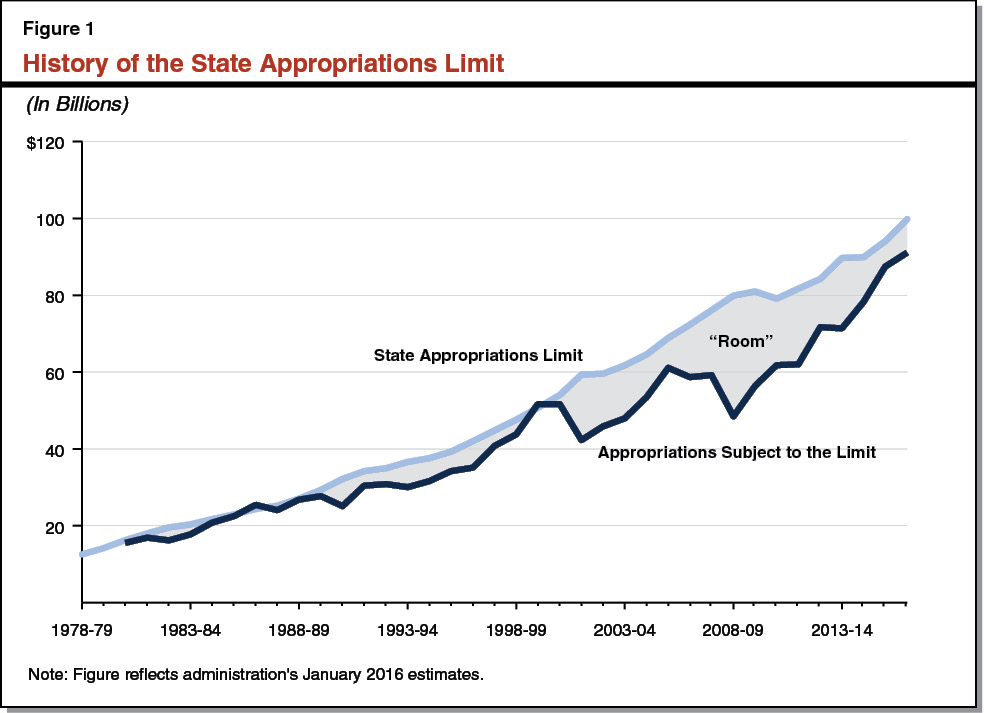

Gann Limit Constrained State Spending in Mid‑1980s. Figure 1 shows historical calculations of the state’s appropriations limit, or SAL, and appropriations subject to the limit. Initially, the Gann Limit had little effect on state budgeting. In part, this was because prior‑year surplus balances were factored into the calculations, giving the state more room under the limit than otherwise would have been the case. During the late 1970s and early 1980s high inflation and slow revenue growth increased room under the limit. By the mid‑1980s, however, strong revenue growth quickly brought state appropriations to the limit. In fact, the state had excess revenues of $1.1 billion in 1986‑87—equal to over $2 billion in today’s dollars. Proposition 4 required the excess to be rebated to taxpayers.

Proposition 98 (1988) Changed How Excess Revenues Are Distributed. In 1988, voters passed Proposition 98. Proposition 98 is the state’s constitutional minimum funding guarantee for schools and community colleges. Proposition 98 also amended the Constitution to require a portion of excess revenues to be spent on Proposition 98 programs.

Voters Changed Gann Limit in 1990. Proposition 111 (1990) significantly changed the Gann Limit. First, the measure changed the population and inflation growth factors in a way that created more room for state and local appropriations. Second, it required excess revenues to be determined over a two‑year period rather than in a single year, making it less likely to trigger taxpayer rebates and additional Proposition 98 spending. Third, the measure changed how excess revenues were to be distributed. Specifically, Proposition 111 required that half of the excess be allocated to additional Proposition 98 spending with the rest allocated to taxpayer rebates. Lastly, Proposition 111 exempted additional categories of appropriations from the Gann Limit.

Taxpayer Rebates Not Triggered Since Mid‑1980s. In the early 1990s, the SAL rarely affected state budgeting because of the changes made by Proposition 111. As revenues surged during the dot‑com boom of the late 1990s, however, the state approached the limit. The state had excess revenues in 1999‑00, but because appropriations were under the limit in 2000‑01, additional Proposition 98 spending and taxpayer rebates were not required. The 2001 recession and resulting decline in state revenues created substantial room under the limit by 2001‑02. (We discussed the SAL issues from around this time in our April 2000 report, The State Appropriations Limit.) Since 2001‑02, the state has continued to have considerable room under the limit.

Back to the TopHow the State Appropriations Limit Works

Each year, Article XIII B requires the state to perform a series of complex calculations. In this section, we explain the current rules of the SAL calculation.

Annual SAL Calculations Included in Budget Bill, Subject to Budget Process. Statutes require the Governor to include SAL calculations in his or her annual budget proposal to the Legislature. (Detail of these calculations can be found in Schedules 12A through 12E in the Appendix of the Governor’s Budget Summary. Historical SAL estimates can be found in Chart L on the Department of Finance website.) Under state law, the estimate “shall be subject to the budget process.” Currently, Section 12.00 of the annual budget bill lists the state appropriations limit, and declares that any court action to review or void this determination must be stated within 45 days of the budget taking effect.

Initial Calculations for 1978‑79 Established the Base

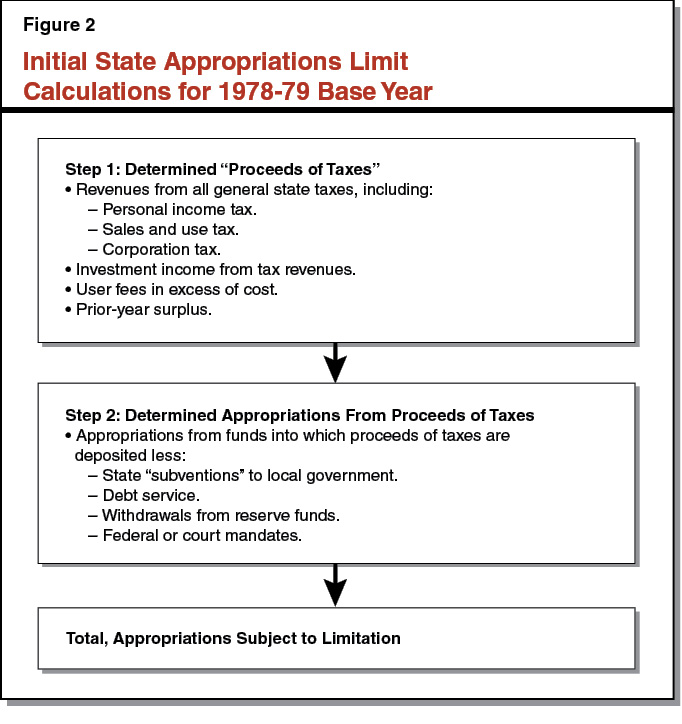

Limit Based on Appropriations in 1978‑79. The fundamental purpose of the Gann Limit is to keep real per capita government spending under the 1978‑79 level. In order to accomplish this task, the measure required a series of complex calculations to determine the 1978‑79 base, as summarized in Figure 2. The Legislature faced various choices in implementing these calculations, but for simplicity’s sake, we focus here on those choices relevant to the Governor’s proposal.

First Step Was to Determine “Proceeds of Taxes.” The Gann Limit does not constrain appropriations from all government revenues. Rather, it applies the limit to appropriations from proceeds of taxes. Essentially, this means that appropriations from tax levies are subject to the limit. For example, revenues from the state’s “big three” taxes—the personal income tax, sales and use tax, and corporation tax—were included in the initial calculation of state proceeds of taxes. Appropriations from non‑tax revenues, such as fees to provide a service to feepayers, are not subject to the Gann Limit and therefore were not included in the initial calculations.

Second Step Was to Determine Appropriations From Proceeds of Taxes. The next step in the initial calculations was to sum appropriations from funds that received proceeds of taxes. Article XIII B allows for various exemptions from the SAL, which are detailed in Figure 2. Of particular relevance to Governor’s proposal are “state subventions to local government,” particularly to school districts. Generally, state subventions are state funds that support local programs. State subventions are exempted from the state’s limit and counted under local limits. Proposition 4 left state subventions largely undefined—thus, the Legislature was left with the task of determining what types of programs would be considered state subventions. In our 1979 report on implementing the Gann Limit, we addressed the trade‑offs inherent in adopting different interpretations of state subventions, calling this “one of the most important tasks confronting the Legislature in implementing Proposition 4.”

Regarding schools, the Legislature implemented Proposition 4 to count base per‑pupil funding at the school district level. The state counted the remaining funds—including categorical programs over which the state exercised relative control—under the state’s appropriations limit. We detail our review of legislative intent concerning how the Gann Limit applies to school districts in the box below.

Exploring Legislative Intent

In assessing the Governor’s Gann Limit proposal, we reviewed historical documents to understand legislative intent regarding state subventions to school districts. Below, we summarize our findings.

Implementing Legislation Defined Subventions to Cities, Counties, and Special Districts Based on Degree of Control. Proposition 4 (1979) was generally silent on how expansive the definition of subventions should be; however, our office and others at the time pointed to one phrase in the measure that provided some guidance. Specifically, Section 8(a) of the measure references state subventions “for the use and operation of local government,” suggesting that the degree of local control over the use of funds could guide whether they should be considered state subventions. The Legislature appears to have adopted this view. The 1981‑82 Governor’s Budget Summary states, “the implementing legislation provides that state funded programs which are administered locally will be subject to limitation at the state level because the legislature determines the size and scope of these programs.” The summary then lists several programs that “are provided to local government for general purposes and their use is not restricted by statutes.”

Most State Education Funding Counted at School District Level With Remainder Counted at State Level. Concerning school districts, the state adopted a similar approach, with funding counted at different levels based generally on degree of local control. Specifically, the state counted at the state level around $900 million in categorical programs and about $1.5 billion that the state provided at the time to address disparities in funding across districts. This latter funding—provided in response to the Serrano court decision—was provided through “equalization formulas.” The remaining roughly $4 billion in state education funding over which school districts had more control was counted at the school district level. Chapter 1205 of 1980 (SB 1352, Marks), the implementing legislation, stated:

The Legislature…finds and declares…that equalization of the financial capabilities of school districts is a matter of statewide interest and concern and that state money provided to school districts to achieve this end is properly excluded from “state subventions” to local school districts as that term is used in Article XIII B of the California Constitution.

Similarly, the various categorical aid programs provided by the state are provided as a matter of statewide public policy. The changing character of children and neighborhoods and the resultant changing needs of local school districts require flexibility in providing these programs which can only be achieved by characterizing these programs as state programs, thereby excluding state support for these programs from state subventions to local school districts.

The 1981‑82 Governor’s Budget Summary confirms the intent of the Legislature:

State subventions for K‑12 school districts are divided, with a portion subject to the state appropriations limit and a portion subject to school district limits.

The state has augmented the basic K‑12 educational program through a series of “equalization formulas” designed to bring the schools into substantial compliance with the Serrano court mandate. In view of the control which rests with the state over these and other categorical program expenditures, the implementing legislation provides that expenditures above the basic program level are the responsibility of the state and therefore a part of the state’s appropriations limit.

Local school districts are responsible for making available to all children a basic level of education. This basic program level is subject to limit at each school district.

State subventions for community colleges are treated similarly to subventions for school districts. The portion of state support dedicated to equalization will be placed, along with state‑supported categorical programs, in the state base. The remainder of the community college subventions augment local revenues and are subject to limitation at each community college district.

In summary, concerning school districts, the state implemented Proposition 4 by placing nearly two‑thirds of state aid under the districts’ limits. Amounts in excess of these levels—including categorical aid—were placed under the state’s limit.

Resulting Amount Is Appropriations Subject to Limitation. After determining proceeds of taxes and appropriations from those proceeds of taxes, the remaining amount—appropriations subject to limitation—was deemed to be the 1978‑79 base year SAL. The SAL was grown for population and inflation in 1979‑80 and 1980‑81 and became effective for the 1980‑81 fiscal year. In the next section, we describe how the SAL grows each year.

Calculating Year‑to‑Year Changes in the SAL

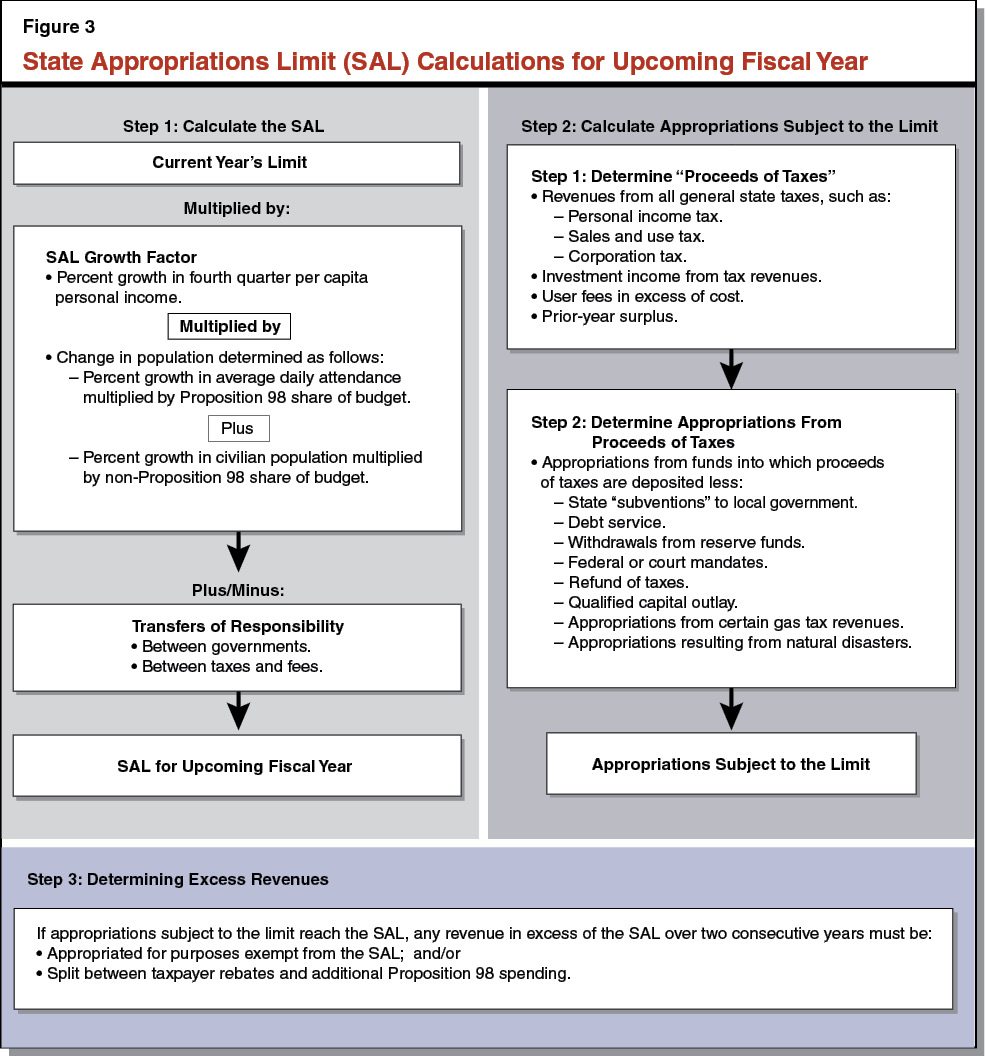

Figure 3 shows the annual SAL calculations for the upcoming fiscal year. Step 1 shows the calculation of the SAL, step 2 shows the calculation of appropriations subject to the limit, and step 3 shows the determination of whether the state has excess revenues. Below, we walk through the annual steps necessary to compute the SAL.

Multiply Current Year’s SAL by SAL Growth Factor. The current year’s SAL is the starting point for determining the upcoming year’s SAL. The current year’s SAL is multiplied by the “SAL growth factor,” an annual measure of inflation and population growth. As noted earlier, Proposition 111 changed the inflation and population measures used to compute the SAL growth factor. The current SAL growth factor is determined by multiplying the two items below:

- Measure of Inflation. The annual change in per capita personal income is determined using (1) California 4th quarter personal income, as measured by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, and (2) the civilian population of the state, as measured by the Department of Finance.

- Measure of Population Growth. The SAL growth factor’s change in population is a weighted average of change in the school population and change in the civilian population. Specifically, growth in average daily attendance is weighted by the Proposition 98 share of the state budget (roughly 40 percent) and growth in the civilian population is weighted by the non‑Proposition 98 share of the state budget (the other roughly 60 percent). The sum of these two population growth rates results in the estimate of change in population used in the SAL growth factor.

Account for Transfers of Responsibility. From time to time, governments transfer responsibility for providing services to other governments or to the private sector. For example, the state might transfer responsibility for operating a park to a local government. In this example, Proposition 4 requires the state and local government to agree on an amount to be transferred from the state’s appropriations limit to the local government’s appropriations limit. Proposition 4 also requires adjustments in the limit if responsibility for a program is transferred from a tax to a fee.

Resulting Amount Is the SAL for the Upcoming Fiscal Year. After multiplying the current year’s limit by the SAL growth factor and adding or subtracting any transfers of responsibly, if applicable, the resulting amount is the SAL for the upcoming fiscal year.

Calculating Appropriations Subject to the State Limit

Similar Process to Initial Calculation of 1978‑79 Base. Step 2 of Figure 3 shows the process used in determining appropriations subject to the SAL. The first step is to determine revenues from proceeds of taxes. (Schedules 12B and 12 C in the Appendix of The 2017‑18 Governor’s Budget Summary lists the revenues currently excluded from the SAL.) The next step is to determine the amount of appropriations from those proceeds. After reducing the appropriations by the various exemptions, such as subventions to local governments, the resulting amount is appropriations subject to the state limit. The total level of these appropriations cannot exceed the SAL for that year.

Today’s process is nearly identical to the process used to determine the initial 1978‑79 base SAL that we described earlier but with a few small differences. Specifically, Proposition 111 added three new categories of exempt appropriations: (1) appropriations resulting from certain emergencies, (2) certain capital outlay projects, and (3) appropriations from certain gas tax revenues.

Determining Excess Revenues

If the state over any two‑year period has revenues that it has not appropriated (because it has spent up to its limit), Proposition 4 requires that these excess revenues be:

- Appropriated for purposes exempt from the SAL; and/or

- Split between additional Proposition 98 spending and taxpayer rebates.

How Gann Limit Works for School Districts

State Law Sweeps School District Room, Essentially Maximizing State Flexibility. State statutes detail the process by which districts administer their limits. First, school districts grow their appropriations limits using a process similar to that of the state. Next, school districts estimate their proceeds of taxes—including their local property tax shares and subventions that they receive from the state. State statute essentially maximizes the amount of state education funding that can be counted under school district limits. Specifically, if a school district’s limit is greater than its proceeds of taxes—in other words, if a school district has room under its limit—additional state education funding is included in the calculation to bring the school district’s appropriations up to its limit. (For purposes of this calculation, only the funding provided through the Local Control Funding Formula is included. Categorical funds are counted at the state level.) Statewide, however, not all state education funding can be included under school districts’ collective limits. The balance of state aid that cannot be absorbed under school district limits is counted at the state level. This mechanism essentially counts as much state education aid as possible at the school district level while counting all funds at either the state or local level. (The state applies a similar process for administering community college district limits.)

State Minimized Effects of Proposition 4 on School Districts. In some cases, a school district’s local proceeds of taxes exceed a school district’s appropriations limit. This happens, for example, in periods of strong property tax growth when revenue growth exceeds growth in appropriations limits. In these cases, statutes limit Proposition 4’s effects on school districts by allowing school districts that would otherwise exceed their limits to increase their limit by notifying the state Director of Finance. The school district increases its limit by the amount needed to keep appropriations under their limit and the state makes a like downward adjustment to its limit to keep the overall level of government spending under the real per capita 1978‑79 level.

Available Data Suggest School and Community College Districts Could Have More Than $4 Billion in Room. Some districts have an appropriations limit that exceeds the revenue they receive from local property taxes and state subventions. In other words, these districts have room left over even after the state has counted all of their apportionment funding toward their local limits. Based on the reports that districts file with the state, we think the available room could exceed $4 billion statewide. Of this amount, the bulk is reported by community college districts. Possible factors that could explain why college districts have more room than school districts include differences in the funding formulas for the two systems and varying practices for administering changes to local limits over time.

Back to the TopGovernor’s Proposal

Proposes New Interpretation of Gann Limit Provisions. The administration’s SAL calculations included in the Governor’s 2017‑18 budget proposal adopt a new interpretation of the Proposition 4 implementation statutes. The Governor proposes to no longer count $22 billion in state education appropriations toward the state limit. First, the Governor proposes to no longer count under the state limit roughly $14 billion of state funding that cannot be absorbed under school district limits. (This is our estimate; the administration declined to provide us its estimate.) Second, the Governor proposes to no longer count under the state limit roughly $8 billion in categorical aid to school districts. The Governor excludes these funds from the state limit by categorizing them as state subventions to local government.

Does Not Count Additional State Subventions at Local Level. Most importantly, the Governor’s proposal does not count the $22 billion in additional state subventions as local proceeds of taxes. In other words, the Governor does not count the funds under either the state’s or school districts’ limits. In effect, the funds become “nowhere money,” meaning they are not accounted for under Gann Limit calculations.

Back to the TopAssessment

Proposal Creates $22 Billion in State Spending Capacity

“Nowhere Money” Creates More Spending Capacity. Figure 4 compares our estimates of state spending capacity under current law with the Governor’s proposal. Even though the state would still be spending the $22 billion in school aid, the Governor proposes to no longer count these appropriations under the Gann Limit. This frees up $22 billion in room under the SAL that can be used for new state spending. The Governor’s proposal, therefore, can be viewed as creating more government spending capacity than the real per capita 1978‑79 level, thus undermining the Gann Limit.

Proposal Raises Legal Concerns

Governor’s Proposal Contradicts Long‑Standing SAL Interpretation. Based on our review of the Legislature’s intent in implementing Proposition 4—described earlier in the text box—it is clear that the state intended to count under the state’s limit (1) categorical programs and (2) funding provided through equalization formulas. (Today’s version of this latter funding is the $14 billion of state aid that cannot be absorbed under school district limits.) In 1980, the Legislature declared its intent that these programs are a matter of statewide interest and that their funds should not be counted at the local level. The 1981‑82 Governor’s Budget Summary also confirms this intent, stating that this funding was “the responsibility of the state and therefore a part of the state’s appropriations limit.” The Governor now proposes to change this long‑standing SAL interpretation.

Proposed Interpretation of Statute Appears to Conflict With Constitution. The administration points to statutes as the basis for their proposed change in SAL interpretation. Existing statutes are clear that the funds in question are not counted as school district proceeds of taxes. The statutes were written that way, however, because when the Legislature implemented Proposition 4, it chose to count the funds at the state level.

The Constitution requires that appropriations from state proceeds of taxes be counted either as state appropriations subject to the limit or as subventions that are then counted as local government proceeds of taxes (unless specifically excepted under the Constitution). If some appropriations are not counted at one level or the other, total government appropriations could be greater than intended under the Gann Limit. Specifically, the Constitution states that “With respect to any local government, ‘proceeds of taxes’ shall include subventions received from the State . . . and, with respect to the state, proceeds of taxes shall exclude such subventions.” By not counting the additional state subventions as school district proceeds of taxes, the nowhere money created in the Governor’s proposal allows for more government spending capacity than was intended by the voters in passing, and later modifying, the Gann Limit.

San Francisco Lost Similar Gann Limit Case. In 1992, the California Supreme Court decided a similar case concerning appropriations limit calculations—San Francisco Taxpayers Association v. Board of Supervisors of the City and County of San Francisco. San Francisco included retirement contributions in its initial appropriations limit calculations. In the mid‑1980s, the Board of Supervisors decided to exclude the contributions and “rebench” its appropriations limit as if the contributions had always been excluded. In this case, rebenching the limit removed San Francisco’s retirement contributions from its 1978‑79 base year limit. San Francisco then recalculated its appropriations limit by growing the new, lower base year limit by the same growth factors it originally used. The result of the rebenching process was a lower appropriations limit.

While excluding retirement contributions from the calculations meant San Francisco counted less appropriations toward the limit, the rebenching also reduced San Francisco’s appropriations limit. In other words, rebenching the limit offset much of the “gain” that San Francisco achieved from excluding the contributions. The move would have been advantageous to San Francisco, however, if retirement contributions were growing faster than their appropriations limit.

The court ruled against San Francisco’s exclusion of retirement contributions, finding that “the manifest purpose of Proposition 4 was to limit the overall growth of governmental appropriations.” “To remove from the spending limit such a large category of appropriations as retirement contributions,” the court noted, “would do violence to that goal.”

The language of the court is notable because in this case San Francisco rebenched its appropriations limit, offsetting much of the advantage San Francisco would have otherwise achieved from not counting retirement contributions toward the limit. In other words, the court ruled against San Francisco despite its efforts to address the nowhere money problem in its plan. By failing to address the nowhere money problem in his proposal, the Governor’s plan seems to run further afoul of the Constitution than San Francisco’s previously invalidated plan.

Back to the TopRecommendation

Recommend Legislature Reject Governor’s Proposal. The Governor’s proposal contradicts long‑standing policies regarding the implementation of the Gann Limit. By creating nowhere money—state school spending that is counted neither at the state nor local level—the plan, in our view, would be highly vulnerable to legal challenges. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal and direct the administration to produce SAL calculations for the 2017‑18 budget using the current law methodology. Using that methodology as a starting point, the Legislature could then consider options—such as designating more appropriations to categories exempted from the SAL—to preserve room under the state’s Gann Limit.

Back to the TopLAO Calculation of SAL

If the Legislature rejects the Governor’s SAL proposal, it will need to consider alternative estimates of the SAL in developing the 2017‑18 budget. (We note that the administration declined to provide us with SAL estimates under the current law methodology.) Below, we first develop an estimate of what the administration’s SAL estimates would have been under the current law methodology. We then identify additional issues we came across while evaluating the Governor’s proposal.

Establishing a Baseline

Figure 5 shows our estimate of what the administration’s SAL estimate would have been under the current law methodology. We start with the administration’s January 2017 SAL estimates, back out administration calculations of education subventions, and insert our calculation of what education subventions would have been under the previous (current law) SAL calculation method. In other words, the only place where these calculations differ from those displayed in The 2017‑18 Governor’s Budget Summary is the line in Figure 5 labeled “education subventions.” Figure 6 details the adjustments we made to the administration’s education subventions to reflect the current law methodology.

Figure 5

State Nearing State Appropriations Limit (SAL)

Under Current Law Methodology

LAO Estimates (In Billions)

|

2015‑16 |

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

|

|

Calculation of SAL |

|||

|

Limit |

$94.0 |

$99.8 |

$103.0 |

|

Calculation of Appropriations Subject to Limit |

|||

|

Administration’s Proceeds of Taxes |

$142.7 |

$147.4 |

$152.2 |

|

Department of Finance noneducation exemptions |

‑$21.4 |

‑$23.6 |

‑$22.7 |

|

Education subventionsa |

‑30.5 |

‑27.9 |

‑29.3 |

|

Subtotal, Adjusted Exemptions |

(‑$52.0) |

(‑$51.5) |

(‑$52.0) |

|

Adjusted Appropriations Subject to the Limit |

$90.8 |

$95.9 |

$100.2 |

|

Calculation of Room Under SAL |

|||

|

LAO Estimate of Room Under SAL (Current Law Methodology) |

$3.3 |

$3.9 |

$2.8 |

|

aSee Figure 6 for detail. |

|||

Figure 6

Deriving Estimate of Education Subventions

Under Current Law Methodology

(In Billions)

|

2015‑16 |

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

|

|

Department of Finance Estimate (New Methodology) |

$52.1 |

$51.0 |

$51.2 |

|

Remove categorical program spending |

‑7.7 |

‑8.0 |

‑7.7 |

|

Reflect state funding not absorbed under school district limits |

‑13.9 |

‑15.1 |

‑14.3 |

|

LAO Estimate (Current Law Methodology) |

$30.5 |

$27.9 |

$29.3 |

State Nearing SAL Under Current Law Methodology. Our calculations suggest that if the administration provided SAL calculations under the current law methodology, the state would have little room under the SAL, as shown in Figure 5. Specifically, the state would end 2015‑16 through 2017‑18 with between $2.8 billion and $3.9 billion of room under the SAL.

Prior Administration Calculations Appear to Have Overstated Room Under SAL. In the course of our work to establish this part of our SAL baseline, we determined that the administration seems to have overstated state subventions in its January 2016 SAL calculation by over $6 billion annually for 2014‑15 through 2016‑17. These overstated state subventions had the effect of decreasing state appropriations subject to the limit, thus increasing the amount of room under the SAL. Our estimates in Figures 5 and 6 correct for these overstated subventions. The Appendix at the end of this report provides more information about this issue.

Other Issues for Legislative Consideration

In the course of our review of the Governor’s proposal, we identified additional SAL issues outside of the Governor’s proposal that merit legislative attention. Addressing some of these issues would further erode state room under the SAL while others would create additional state room. While we think these issues merit attention, further examination of the Gann Limit and its history at both the state and local levels easily could uncover information that would change SAL estimates by billions of dollars one way or the other. For example, we found that among the many estimates of state costs to comply with federal and court mandates (which are exempt from the limit), the administration probably could have included additional health and human services costs related to federal overtime regulations. This would increase room under the SAL.

Include Road Improvement Charge in Proceeds of Taxes. The administration’s 2017‑18 SAL calculation excludes revenues from the road improvement charge proposed as part of the Governor’s transportation package. The road improvement charge assesses a $65 charge on all vehicles. Generally, to be considered a fee, the charge would have to approximate the cost of the motorist’s use of the roads or the cost of providing a service directly to the fee payer. For example, the Department of Motor Vehicles assesses a fee to individuals who apply for a driver’s license. The fee approximates the cost to the state of providing that service. The Governor’s proposed road improvement charge, on the other hand, assesses a $65 levy on all vehicles—regardless of the motorist’s usage of public roads—and uses the revenue for the broad public benefit of improving transportation infrastructure. There is, therefore, a strong argument that this assessment is a tax. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature count the $1.1 billion that the administration estimates the charge will raise in 2017‑18 as proceeds of taxes. This would reduce room under the SAL in that year by a like amount.

Count Mandate Payments at State Level Pursuant to Constitution. Proposition 4 specifically requires state costs to reimburse local government for mandated programs to be counted at the state level. Beginning in January 2015, the administration counted mandate reimbursements to school districts as state subventions. In order to be consistent with Proposition 4, we recommend that the Legislature count education mandate payments toward the SAL. This would reduce state room under the SAL by $451 million in 2014‑15, $3.8 billion in 2015‑16, $1.4 billion in 2016‑17, and $287 million in 2017‑18. (We note that a portion of these payments that did not actually reduce the mandate backlog could be counted at the local level. Because most school districts have no room under their limits with which to absorb additional state funding, however, essentially all of the monies would be counted at the state level in any case.)

Adjust SAL Downward to Account for Recent School District Limit Adjustments. As described earlier, school districts that would otherwise exceed their limits can increase their limit by notifying the state Director of Finance. When this occurs, school districts increase their limit by the amount needed to keep appropriations under their limit. The state is then supposed to make a downward adjustment to the SAL to keep the overall level of government spending capacity under the real per capita 1978‑79 level.

The administration’s calculations appropriately adjust the SAL for shifts expected to occur in 2017‑18. In recent years, however, the administration reflected these shifts by adjusting education subventions rather than reducing the SAL. This essentially had a one‑time effect on state room under the SAL as opposed to the ongoing, compounded effect that would have occurred if the administration had been adjusting the SAL. We recommend that the Legislature adjust the SAL downward to appropriately count for these prior‑year shifts. We estimate that adjusting this issue for 2012‑13 through 2016‑17 combined would reduce the SAL by $1.1 billion by 2017‑18. The effect in 2015‑16 and 2016‑17 would be partially offset by removing the administration’s education subvention adjustment.

Adjust SAL Upward for Unnecessary Transfer of Responsibility Adjustment. The Governor’s 2017‑18 budget plan proposes to reduce the SAL by $50 million to reflect a transfer in responsibility. Specifically, the administration proposes to shift the responsibility for University of California graduate medical education from the General Fund to tobacco tax funds approved by voters in Proposition 56 (2016). A provision in Proposition 56, however, amends the Constitution to state “no adjustment in the appropriations limit of any entity of government shall be required . . . as a result of revenue appropriated from” a fund created by the measure. In other words, we do not think the adjustment is necessary. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature adjust the 2017‑18 SAL upward by $50 million, thereby creating an equivalent amount of room in the state’s limit.

Legislature Could Shift Room Under School District Limits to State. State law limits the Gann Limit’s effect on school districts by shifting state room to districts that would otherwise exceed their limits. As currently structured, however, room is only shifted in one direction—from the state to school districts. As noted earlier, schools and community colleges appear to have over $4 billion in room under their limits. The Legislature could change state law to shift room in both directions, thereby allowing the state to capture the room at the school and community college district level. This option would not require a change in where education spending is counted under Gann Limit calculations. In addition, this option would not increase overall government spending capacity, meaning it could increase state flexibility under the SAL without violating the spirit of the Gann Limit.

Back to the TopConclusion

Governor’s Proposal Violates Spirit of the Gann Limit. The fundamental purpose of the Gann Limit is to keep real per capita government spending under the 1978‑79 level. The Governor’s proposal expands government spending capacity, thereby violating the spirit of Proposition 4. We recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal.

Gann Limit Now Appears to Be a Real Budget Constraint. In this report, we offer SAL calculations under the current law methodology. Our estimates suggest that the state is nearing the SAL. While the Gann Limit has not been a focus of budget discussions for some time, this finding is not entirely unexpected, as state room under the SAL tends to shrink as economic expansions persist.

In our 2017‑18 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, we stated that the Governor’s personal income tax estimates for 2017‑18 appear too low. If we are correct and revenues increase in the May Revision, the state may find itself on the brink of exceeding the SAL. Beyond 2017‑18, the SAL could continue to constrain the state if the economic expansion continues. The SAL could constrain state spending to a greater extent with the passage of additional taxes for transportation or other purposes.

Options to Respond to Tightening SAL. If the state finds itself with excess revenues for two consecutive years, there are a few options for the Legislature to consider. First, the Legislature could do nothing, in which case excess revenues would be divided between Proposition 98 spending and taxpayer rebates. Second, the Legislature could reduce taxes either through lower rates or increased tax credits or reductions. The Legislature also could shift appropriations from items subject to the SAL to purposes that are exempt from the limit. These include debt service; certain capital outlay projects; and subventions for cities, counties, and certain special districts (to the extent these local governments have room under their limits).

Finally, options exist that could shift up to several billion dollars in room from school and community college districts to the state. Such an action would not require a change in where education spending is counted under Gann Limit calculations and would not increase overall government spending capacity, meaning it would not violate the spirit of the Gann Limit. Such actions could also be designed to hold schools harmless. While these options could relieve some pressure on state budgeting, the gain to the state would be far smaller than under the Governor’s proposal. This means that the SAL could continue to constrain state budgeting even if the state acts to capture some or all of the room under school district limits.

Back to the TopAppendix:

Prior Administration Calculations Appear to Have Overstated Room Under SAL

Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). The 2013‑14 budget reflected a major restructuring of education finance. In general, the LCFF gave more control to school districts by decreasing the amount of categorical funding and increasing general purpose funding. The LCFF also increased funding for low‑income and English learner students.

Effect on State Appropriations Limit (SAL) Calculations. Figure A1 shows calculations of education subventions from the Governor’s January 2013 budget proposal. As explained in the main text of this report, the Legislature has implemented the Gann Limit to count at the state level categorical aid and state funding that cannot be absorbed at the school district level. The LCFF proposal reduced the amount of categorical aid and increased general purpose funding. This is reflected as an increase in K‑12 LCFF and other apportionments in the figure. Because district appropriations limits would have increased by much less than the increase in general purpose funding, state aid not absorbed at the school district level increased (reflected as a larger negative number). This increase made sense given the changes made by LCFF. Because categorical aid is counted at the state level, the decrease in that funding is not reflected in the figure.

Figure A1

State Subventions to Districts in

Governor’s 2013‑14 Budget Proposal

(In Millions)

|

Estimated |

Proposed |

Change |

|

|

K‑12 LCFF and other apportionments |

$21,469 |

$29,660 |

$8,191 |

|

Other K‑12 funding |

2,435 |

1,124 |

‑1,311 |

|

State aid not absorbed under |

‑1,709 |

‑6,778 |

‑5,069 |

|

Community college funding |

3,527 |

4,142 |

615 |

|

Total, Education Subventions |

$25,722 |

$28,148 |

$2,426 |

|

LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula. |

|||

2013‑14 and 2014‑15 Subventions Increased Substantially After 2013‑14 Budget. Figure A2 shows how the amount of subventions for 2013‑14 and 2014‑15 changed after January 2013. As shown in the figure, state aid not absorbed under school district limits—again, reflected as a negative number in the administration’s displays—decreased substantially beginning in January 2014. By the time the estimates were finalized, total state education subventions increased by $4.7 billion for 2013‑14 and $6.6 billion for 2014‑15. The decrease in state aid not absorbed under school district limits does not make sense given that school district funding was growing much faster than local limits over the period. In other words, we would expect the increased Proposition 98 funding to have decreased room under the state limit rather than the increase in room that was shown on administration displays.

Figure A2

State Education Subventions Increase Substantially

Beginning in January 2015

(In Millions)

|

2013‑14 |

Difference |

||

|

Revised |

Actual |

||

|

K‑12 LCFF and other apportionments |

$29,496 |

$30,869 |

$1,373 |

|

Other K‑12 funding |

1,089 |

1,147 |

58 |

|

Community college funding |

3,917 |

3,548 |

‑369 |

|

State aid not absorbed under school district limits |

‑6,436 |

‑2,757 |

3,679 |

|

Total Subventions, Education |

$28,066 |

$32,807 |

$4,741 |

|

2014‑15 |

Difference |

||

|

Revised |

Actual |

||

|

K‑12 LCFF and other apportionments |

$34,849 |

$34,259 |

‑$590 |

|

Other K‑12 funding |

425 |

854 |

429 |

|

State aid not absorbed under school district limits |

‑10,645 |

‑2,940 |

7,705 |

|

Community college funding |

4,324 |

3,322 |

‑1,002 |

|

Total Subventions, Education |

$28,953 |

$35,495 |

$6,542 |

|

LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula. |

|||

Calculations Appear to Have Overstated Room Under the SAL. Using California Department of Education data, we have replicated most of the administration’s January 2016 education subvention calculations. However, we have been unable to replicate the administration’s estimates of state aid not absorbed under school district limits—the key issue discussed above. Our model suggests that the negative value in this line should have been several billion dollars larger beginning in 2013‑14. This would have decreased the amount of state subventions to districts. In 2014‑15, for example, we estimate that state aid not absorbed under school district limits totaled nearly $9 billion rather than the nearly $3 billion in the final display that was included in the Governor’s January 2016 budget summary. Because the higher number increases appropriations subject to the state limit, reflecting it in the final 2014‑15 SAL calculation would have reduced the amount of room under the SAL from $9.4 billion to roughly $3 billion. We note that the final administration estimate for the 2014‑15 SAL was included in the Governor’s January 2016 budget proposal. In other words, the administration has “closed” its estimates for that fiscal year.