Chapter 1

The Budget Outlook

This report provides our projections of the state’s General Fund revenues and expenditures for 2010–11 through 2015–16 under current law, absent any actions to close the state’s budget gap. Our projections primarily reflect current–law spending requirements and tax provisions, while relying on our independent assessment of the outlook for California’s economy, demographics, revenues, and expenditures. The report aims to assist the Legislature with its fiscal planning as it begins to consider revisions to the 2010–11 budget and adoption of the 2011–12 budget. The basis of our estimates is described in the nearby box.

Basis for Our Estimates

Our revenue and expenditure forecasts are based primarily on the requirements of current law, including constitutional provisions (such as the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee for school funding), statutory requirements, and currently authorized federal funding. In other cases, the estimates incorporate effects of projected changes in caseloads, federal requirements, and other factors affecting program costs. The estimates are not predictions of what the Legislature and the Governor will adopt as policies and funding levels in future budgets. Instead, our estimates are intended to be a reasonable baseline of what would happen if current–law policies continue to operate in the future. We intend the forecast to provide a meaningful starting point for legislative deliberations involving the state’s budget so that corrective actions can be taken.

No COLAs or Inflation Adjustments Assumed. In line with the Legislature’s policy in recent years, we generally have not made annual cost–of–living adjustments (COLAs) or price increase adjustments over our forecast period. (Health programs are an exception since the costs of current–law benefits are subject to inflationary increases.) In particular, in the 2009–10 budget package the Legislature added to state law a provision stating that most programs, including universities, the courts, and various social services programs, would no longer receive “automatic” COLAs and inflation adjustments. The impact of not adjusting for COLAs and inflation means that the purchasing power of current state expenditures will be eroded by inflation over the forecast period and the state will not be able to maintain a “current services” budget. Should the Legislature choose to provide these adjustments in future years, we estimate that the state’s annual budget problems would be even greater than those indicated in our forecast—by about $400 million in 2011–12 and, if inflation adjustments were provided each year during the forecast, by as much as $3 billion in 2015–16. If the Legislature were to approve additional state employee pay or benefit increases (beyond those included in recent labor agreements), that also would increase costs above those indicated in our forecast.

Impact of Future Ballot Measures Not Considered. In keeping with our use of current law as the basis for our forecast, our projections do not consider any future impact of measures scheduled for future statewide elections—the $11 billion water bond and the budget reserve and spending measure passed as part of the 2010–11 budget package. We do, however, incorporate our preliminary estimates of the fiscal effects of propositions that were passed on November 2, 2010.

State Victories in Court Cases Assumed. Our forecast generally assumes that the state eventually prevails in active, budget–related court cases. (By active cases, we mean open cases at the trial or appellate court level.) The state faces an array of active cases, including ones related to the budgeted shift of redevelopment funds and various health and social services reductions. The state also is appealing a three–judge panel’s order to reduce the prison population to the U.S. Supreme Court.

|

Figure 1 shows our estimate of the condition of the General Fund through the end of 2011–12 assuming no corrective action. The 2010–11 fiscal year would end with a $6 billion deficit. In 2011–12, expenditures would exceed revenues by $19 billion and leave the state with a year–end deficit of over $25 billion. Accordingly, we estimate that the Legislature and the new Governor will have to address a budget problem of $25 billion between now and the time that they agree to a 2011–12 state budget plan.

Figure 1

LAO Projection of General Fund Condition if No Corrective Actions Are Taken

(In Millions)

|

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

|

Prior–year fund balance

|

–$5,375

|

–$5,371

|

–$4,591

|

|

Revenues and transfers

|

87,041

|

93,284

|

83,530

|

|

Expenditures

|

87,037

|

92,505

|

102,756

|

|

Ending fund balance

|

–$5,371

|

–$4,591

|

–$23,817

|

|

Encumbrances

|

1,537

|

1,537

|

1,537

|

|

Reservea

|

–$6,908

|

–$6,128

|

–$25,354

|

2010–11 to End in Deficit

Projected 2010–11 Year–End Deficit of $6 Billion

$3.5 Billion of New Funding or Flexibility Not Yet Approv ed by U.S. Government. At the time the Governor signed the 2010–11 budget package in October 2010, the administration estimated that the General Fund would have a $1.3 billion reserve at the end of 2010–11. A key assumption in that calculation was that the state would receive around $4 billion in federal funding (or additional flexibility in operating state–federal programs like Medi–Cal) that had not yet been approved by the federal government. Recently, the federal government approved a waiver affecting Medi–Cal and other health programs that provides annual General Fund savings that is initially estimated to total around $500 million per year. Our forecast assumes that the state fails to secure the remaining $3.5 billion of additional federal funding or flexibility incorporated into the 2010–11 budget package. Accordingly, based on that assumption alone, our projections show a General Fund deficit at the end of 2010–11.

A Net $3 Billion of Other Budget Solutions Likely at Risk. In addition to the inability to secure federal funding, we assume the state will be unable to achieve the following 2009–10 and/or 2010–11 budget solutions counted on in the 2010–11 budget package:

- Prisons and Medical Care Receiver. We expect that expenses of the prison medical care Receiver will exceed budgeted amounts by about $780 million and that other prison expenses will surpass budgeted totals by $185 million.

- Employee Compensation. Recent collective bargaining agreements and other personnel actions are projected to achieve over $400 million less in savings than assumed in the 2010–11 budget. In addition, in 2009–10, the state enacted a one–day payroll delay to achieve one–time savings of about $1 billion. Estimates now indicate the delay achieved savings of $800 million.

- Medi–Cal. Around $400 million of budgeted savings are estimated to be unachievable in Medi–Cal due to (1) the late passage of the 2010–11 budget and (2) our projection that the program will be unable to achieve an unallocated budget reduction of $323 million.

- In–Home Supportive Services (IHSS) Program. As part of the 2010–11 budget package, a variety of solutions were estimated to reduce IHSS costs by $300 million. We estimate that only about one–half of this savings will materialize. In addition, $45 million of budgeted savings from previously enacted anti–fraud activities will not be achieved.

- Lower Property Tax Estimate Affects General Fund Education Spending. Our forecast assumes lower local property tax revenues than the 2010–11 budget package. General Fund spending on Proposition 98, therefore, is over $400 million higher in our forecast for 2009–10 and 2010–11 combined.

- Information Technology Savings. The budget package assumed the administration would reduce departmental budgets by $130 million in 2009–10 and $140 million in 2010–11 to capture savings from recent efficiencies implemented in information technology programs. Our forecast assumes that much of this savings does not flow to the General Fund’s bottom line.

2009–10 and 2010–11 Revenue Projection Down $447 Million. The 2010–11 budget package essentially relied on our office’s May 2010 revenue forecast for 2009–10 and 2010–11, which was $1.4 billion higher than the administration’s. Our current projection has General Fund revenues $447 million below the budget package forecast for 2009–10 and 2010–11 combined.

Proposition 22 Reduces General Fund Solutions by Nearly $800 Million. There is some uncertainty about what Propositions 22 and 26 mean for state finance in the short term, as discussed in the nearby box. Our forecast, however, assumes that Proposition 22 prevents the state from achieving nearly $800 million in budgeted 2010–11 solutions—about $400 million in now–prohibited borrowing from the Highway Users Tax Account and $400 million in now–prohibited use of transportation funds to pay bond debt service.

Effects of November 2010 Ballot Measures on Our Forecast

Three major budget–related measures were approved by voters at the November 2 general election. Proposition 25 changes the vote threshold needed to send a budget bill to the Governor from two–thirds to a simple majority of each house of the Legislature. This may help make it easier for the Legislature to pass an on–time budget each year. At the same time, voters approved Propositions 22 and 26, which restrict the Legislature’s ability to use certain local funds to help balance the budget and raise the vote threshold for passing certain fees from a simple majority to two–thirds, respectively.

Our Assumptions Concerning Propositions 22 and 26. We assume that Proposition 22 prevents the state from borrowing certain transportation special funds for the General Fund, as was assumed in the Legislature’s 2010–11 budget plan. We also assume that loans from such special funds prior to November 3 (the effective date of the measure) are not affected by Proposition 22. Accordingly, in our forecast, about $400 million of not–yet–executed loans from the Highway Users Tax Account are assumed to be prohibited by Proposition 22. This worsens the condition of the General Fund in 2010–11 by a like amount. The budgeted use of certain transportation funding to offset General Fund debt–service costs also is assumed to be impermissible in 2010–11, thereby hurting the General Fund’s bottom line by another $400 million.

In 2011–12, we assume that Proposition 26 fully reverses the “fuel tax swap” adopted by the Legislature earlier this year, beginning November 2011 (one year after voter approval). Accordingly, state sales taxes on gasoline resume (thereby increasing General Fund revenues), excise taxes on gasoline decline, and the General Fund’s payments for transportation programs resume pursuant to Proposition 42 (2002). A timing lag in Proposition 42 payments means that the net effect of these measures is near zero for 2011–12. The ongoing effect of Propositions 22 and 26—approaching $1 billion or more annually—does not hit the General Fund until 2012–13 in our forecast.

Some Uncertainty. Propositions 22 and 26 are complex measures. It is possible that some of the fiscal effects we describe above would not materialize until a stakeholder successfully sues the state in court to force these budgetary changes. Accordingly, our forecast presents a preliminary point of view about their effects on the budget. The actual effect may be different in any given fiscal year.

|

$6.1 Billion General Fund Deficit Forecast for 2010–11. As shown in Figure 1, given all of these expenditure and revenue issues, we forecast that 2010–11 will end with a General Fund deficit of $6.1 billion, absent any corrective action by the Legislature. Various cash management actions—including payment delays approved by the Legislature and borrowing from both investors and state special funds—will facilitate continued General Fund operations despite the forecasted deficit, as described in the nearby box.

Cash Management

Background. As we described in our January 2009 report, California’s Cash Flow Crisis, the state suffers from a basic cash flow problem, even in good years. Most revenues are received during the second half of the fiscal year (January to June), while most expenses are paid in the first half of the fiscal year (July to December). In order to meet payments in the early part of the year, the state obtains short–term borrowing that is paid back within the fiscal year, referred to as revenue anticipation notes (RANs). The state also relies on a pool of “borrowable resources”—balances in state special funds—that can be borrowed for cash flow purposes.

Billions of Dollars of Payments Delayed in 2010–11. The Legislature enacted two sets of cash payment delays for the 2010–11 fiscal year in order to assist with cash management. The first was enacted in special session legislation and allowed for delays of up to $5 billion of scheduled payments to schools, universities, and local governments at almost any given time within the fiscal year. The second set of delays was enacted in the October budget package and allowed for an additional $4.7 billion of payments to be delayed in October and November in order to avoid the issuance of registered warrants (IOUs) and facilitate the issuance of a 2010–11 RAN. The Controller also used his executive authority to delay other payments in October, such as tax refunds. These various payment delays will be repaid within the 2010–11 fiscal year.

Payment Delays Will Be Needed for 2011–12. With a few exceptions, there are no statutory provisions for intrayear payment delays in the 2011–12 fiscal year. Given our forecast for the significant deficit at the end of 2010–11 and the accumulated deficit in the General Fund, the state will likely require significant external cash flow borrowing again in 2011–12. In addition, to avoid the issuance of IOUs at certain points in the year, payment delays similar to those approved in 2010–11 likely will be needed. Local governments, schools, and community colleges previously have indicated that early adoption of payment delays helps them execute their own annual cash borrowings.

Curbing the Deficit Would Reduce Cash Pressures in Future Years. Many temporary or one–time budget solutions—such as borrowing from special funds—increase cash pressures by reducing overall borrowable resources. If the Legislature acts to eliminate operating shortfalls in the coming years, we would expect cash pressures, and hence the need for payment delays, to decline. While removing the payment delays will not have a significant impact on the state’s budget situation, it should reduce the external borrowing costs of local entities and provide more certainty in fiscal planning efforts of schools and community colleges. Reducing cash pressures can also reduce the state’s need for external borrowing, thus reducing the state’s borrowing costs.

|

Major New Budget Problem in 2011–12

With the “Carry–In” Deficit, a $25 Billion Problem to Address. The vast majority of the roughly $20 billion of budget solutions enacted as part of the 2010–11 budget process were one–time or temporary in nature. At the same time, by the end of 2010–11 about $8 billion of temporary tax increases expire, and about $4.5 billion of federal stimulus funding used to reduce General Fund expenses will be exhausted. For these reasons, the state will be left with a large operating shortfall (the difference between annual General Fund revenues and expenditures) problem in 2011–12 totaling $19.2 billion. In addition, the Legislature must address the 2010–11 year–end deficit at or before the time it enacts the 2011–12 budget package. Accordingly, the total budget problem that the state must address between now and passage of the 2011–12 budget totals $25.4 billion in our forecast, as shown in Figure 1.

Key Considerations Regarding the 2011–12 Budget

Sharp Reduction in K–14 Programmatic Spending Already Reflected in Our Forecast. Because of the expiration of temporary tax increases and other factors, General Fund tax revenues are forecast to decline significantly in 2011–12, which drives down the Proposition 98 minimum funding guarantee in our projections. The Proposition 98 minimum guarantee is forecasted to decline from $49.7 billion in 2010–11 (when the Legislature suspended Proposition 98) to $47.5 billion in 2011–12. The General Fund’s share of Proposition 98 funding is forecast to decline as well—from $36.2 billion in 2010–11 to $34.2 billion in 2011–12.

At the same time, it is expected that schools will have spent most of the billions of dollars of recent, one–time federal stimulus and jobs funding approved by Congress. Accordingly, it may be very difficult for the Legislature to achieve additional Proposition 98 savings as part of its 2011–12 budget package. In other words, if the Legislature funds schools at the forecasted minimum guarantee in 2011–12, it would mean billions of dollars in programmatic cuts to education but not contribute a single dollar to closing the $25 billion budget problem.

State Faces Ongoing Constraints on Reducing Health Programs. Our forecast reflects sharp General Fund increases in Medi–Cal, the state’s second–largest General Fund program, that are required under current law and as a result of the expiration of federal economic stimulus funding. The American Reinvestment and Recovery Act (ARRA) of 2009 provided an enhanced federal match in state support for Medi–Cal that will be phased out as of the end of 2010–11. The state’s receipt of billions of dollars in federal assistance under ARRA, however, was on the condition that it maintain the eligibility standards, methodologies, and procedures that were previously in place for Medi–Cal. These constraints originally were to expire along with the provision of ARRA funding. However, provisions in the federal health care reform law essentially extended these maintenance–of–effort requirements for Medi–Cal and also applied them to the Healthy Families Program. This essentially takes off the table many options to scale back these programs that could result in several hundreds of millions of dollars in state General Fund savings annually.

In other areas, such as California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs), the expiration of federal economic stimulus funding (known as the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Emergency Contingency Fund, or TANF ECF) does open up additional options for state savings. The high 80 percent federal matching rate available under TANF ECF for increased CalWORKs grant costs above the state’s base costs in 2007 had been a deterrent to cutting General Fund support for CalWORKs cash assistance, but it is no longer in effect.

Revenue Uncertainty. As we discuss in Chapter 2, there are a lot of challenges with forecasting economic activity and revenues in California following the unprecedented recession that ended in 2009. One of the key challenges is forecasting capital gains. This is always difficult, but is even more so this year given the huge unrealized stock and housing capital losses of recent years and uncertainties about federal tax policy with the pending expiration of various tax cuts. Action or inaction by Congress on the expiring tax cuts in the coming weeks could affect taxpayer behavior and the resulting timing of hundreds of millions of dollars in state revenues related to capital gains.

Of perhaps even greater concern is uncertainty about the federal estate tax. Currently, our forecast—like the 2010–11 budget package—assumes $2.7 billion of estate tax revenues for the General Fund in 2010–11 and 2011–12 combined based on current law. There has, however, been significant speculation that Congress will change estate tax law to eliminate the state’s ability to generate any of these revenues. Should Congress do this, the budget problem for 2011–12 would increase by $2.7 billion above the level indicated in our forecast.

Lingering Budget Problem of $20 Billion For Years to Come

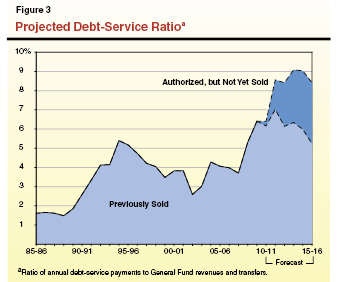

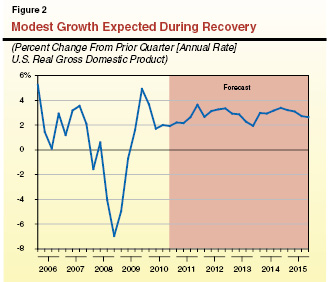

Roughly $20 Billion Annual Problem Forecast Through 2015–16. As shown in Figure 2, our forecast of General Fund revenues and expenditures shows an annual budget problem of around $20 billion through 2015–16. With the econsomic recovery remaining very weak and the lack of many permanent budget solutions in the 2010–11 budget package, the ongoing structural deficit has not changed much since our forecast one year ago. The annual operating shortfall peaks at $22.4 billion in 2012–13, when the state must repay its $2 billion Proposition 1A loan related to local property tax revenues. Thereafter, revenues grow a bit faster than expenditures as the state’s economic recovery becomes stronger. By 2015–16, the annual budget problem is $19.4 billion.

Projections Likely Understate the State’s Fiscal Woes. We believe that our projections probably understate the magnitude of the state’s fiscal problems during the forecast period. First, our forecast generally assumes no cost–of–living adjustments or inflationary increases in departmental budgets. Second, by including only current–law expenditures, our forecast does not include funding to address a number of large liabilities that pose a risk to future state finances, as discussed below.

Massive Liabilities Growing. Unfunded actuarial accrued liabilities in pension and retiree health funds for state employees, teachers, and university employees now total $136 billion. (Possible upcoming actions by the state’s two largest pension systems to lower their assumed annual rates of investment return would expand this number.) The California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) estimates that it needs billions of dollars more per year in contributions—not included in our forecast—to retire its unfunded liabilities within about 30 years and continue operations past the 2040s. Similarly, there are no funds assumed in our forecast to begin retiring the University of California Retirement Plan’s (UCRP) growing unfunded liabilities. State retiree health liabilities continue to grow, driving upward the associated General Fund expenditures. The Legislature took action earlier this year to modify state pension programs, providing some budget relief now and greater relief in the future. The unfunded liabilities of state retirement systems, however, loom over the state’s budget prospects. Left unaddressed in the near term, costs to service CalSTRS, UCRP, and retiree health liabilities will only grow, burdening future Californians more and more and requiring even harder decisions about taxes and services. The state should look for ways to address these problems soon, to avoid passing these huge obligations to future Californians.

Multiyear Approach To Balance the Budget...Beginning Now

Current Budget Problems Hinder Ability to Plan for the Long Term. As discussed throughout this report, California faces immense short–term budget problems and perhaps even more troubling longer–term fiscal challenges. Without immediate action to begin tackling the structural deficit for the long term, the state may not be able in the foreseeable future to move beyond its current stumble from one terrible budget problem to the next. As such, it will continue to be difficult for the state to address fundamental public sector goals—such as rebuilding aging infrastructure, addressing massive retirement liabilities, maintaining service levels of high–priority government programs, and improving the state’s tax system.

Not Possible to Solve the Whole Problem in One Year. In a state as complex as California, with an economy as weak as the one we have right now, it is not possible to solve this $20 billion ongoing budget problem all at once. The solutions necessary to address the whole problem are probably not obtainable in the current environment. Instead, this problem will take several years to solve. Sound financial planning requires that the state’s leaders agree now to a broad framework for a multiyear approach to tackling the stubborn budget problem.

Multiyear Approach Requires Real Budget Solutions. The current fiscal year is the third consecutive one that will end with a General Fund deficit. Key contributors to year–end deficits have been enacted budget solutions that have not been achieved. For example, earlier in this chapter we discussed a net $3 billion of 2009–10 and 2010–11 expenditure solutions that are unlikely to be achieved. Year–end deficits have to be “carried in” to the next fiscal year and make the task of balancing the next year’s budget much more difficult. To make progress over several years in tackling the ongoing deficit, the Legislature should minimize the use of risky budget solutions that contribute to year–end deficits. Instead, budget solutions need to be real—by which, we mean those that have a high probability of achieving budgeted savings. The Legislature can maximize the probability of achieving solutions by passing budgets on time (preferably early) and, in the case of spending reductions, providing specific direction and authority to the administration in well–crafted legislation on how reductions are to be realized.

Revenues Need to Be Part of the Mix. Just as the Legislature will have to prioritize its spending commitments in order to address the ongoing deficit, it will need to examine the revenue side of the ledger. There are several specific revenue policy areas that the Legislature should consider, such as:

- Tax Expenditure Programs. Through tax expenditure programs—special credits, deductions, and exemptions—the state provides subsidies to certain groups or individuals in ways that often have not been shown to be cost–effective. Their modification or elimination raises revenues without having to increase marginal tax rates.

- Increasing Charges for Program Beneficiaries. The Legislature should also look to increasing charges in those cases where the costs of state programs currently supported by the General Fund can appropriately be shifted to specific beneficiaries.

- Extending Certain Temporary Tax Increases. The Legislature may also have to revisit some of the temporary tax increases that are set to expire by the end of 2010–11. We think the best candidates for extension would be the vehicle license fee, where a good policy case can be made to tax vehicles at a rate similar to all other property, and the dependent exemption credit, where the current level is more consistent with the practice of almost all other states.

- Reconsider the Optional Single Sales Factor. The Legislature may wish to reexamine some corporate tax provisions, such as the existing option of multistate companies to switch annually between the new “single sales factor” method of profit apportionment and the state’s traditional method of apportionment for these companies. Making the single sales factor apportionment mandatory, instead of optional, for multistate companies could increase General Fund revenues and help the state’s competitiveness. (For more information, see our May 2010 report, Reconsidering the Optional Single Sales Factor.)

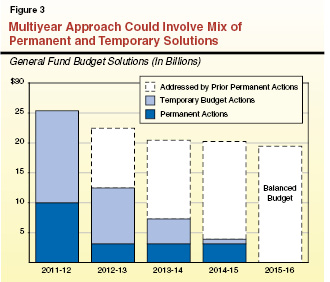

Both Permanent and Temporary Budget Solutions Are Needed in 2011–12. The basic framework we suggest for policy makers to balance the 2011–12 budget would involve a mix of:

- Permanent, real and ongoing expenditure reductions and revenue increases.

- Temporary budget solutions, such as short–term revenue or expenditure changes, asset sales, special fund loans and transfers, extended state employee furloughs or personal leave programs, and delays in lower–priority bond–financed infrastructure projects.

Given our forecast of a $25 billion budget problem in 2011–12, we suggest that the Legislature and the new Governor target $10 billion of permanent budget solutions in 2011–12 and $15 billion of temporary budget solutions. This would be a “down payment” on the multiyear approach to ending California’s structural deficit.

In a Multiyear Approach, More Permanent Solutions Each Year. Figure 3 graphically illustrates—in very simplified form—how a multiyear budget–balancing approach would work, assuming the accuracy of our budget deficit projections, for each fiscal year:

- 2012–13. By taking $10 billion of permanent budget actions in 2011–12, the size of the 2012–13 budget problem we forecast might be reduced from $22 billion to $12 billion. In 2012–13, the Legislature could address the budget problem with about $3 billion of new additional permanent actions (or the growth in savings from previously adopted solutions) and $9 billion of temporary actions.

- 2013–14. Adding together the effects of the permanent budget–balancing actions in 2011–12 and 2012–13, the budget problem we forecast for 2013–14 could be reduced from $20 billion to around $7 billion. The Legislature could address this problem with $3 billion of new additional permanent actions and around $4 billion of temporary actions.

- 2014–15. The prior permanent budget actions would reduce the 2014–15 budget problem from $20 billion to about $4 billion. Roughly another $3 billion of new, permanent budget actions could be adopted, along with $1 billion of temporary solutions.

- 2015–16. In this simplified scenario, there would no longer be a structural deficit facing the state in 2015–16 due to the accumulated effects of the permanent budget actions passed in the previous four years.

Naturally, the real work of balancing the budget would not be this simple. This scenario assumes that our revenue and expenditure forecast assumptions are correct, ignores the interaction between any increased revenues and Proposition 98 funding requirements, and assumes that no temporary budget–balancing actions—such as borrowing—increase costs (and deficits) in later years. The basic concept we offer, however, is that the Legislature can earnestly “chip away” at the budget problem, but only by beginning to enact permanent and real solutions to reduce spending and increase revenues.

The solutions needed to balance the budget will mean unavoidably painful sacrifice by today’s Californians. The benefit of this sacrifice would be putting the state on a sound fiscal footing. That sound footing may allow future Californians to live in a place where the annual state budget process is a chance to improve government’s ability to serve its residents.

Chapter 2

Economy, Revenues, and Demographics

The Economic Outlook

The National Bureau of Economic Research has determined that the national recession that began in December 2007 ended in June 2009. It was the longest recession since World War II and the most severe downturn since the Great Depression The 2007–2009 recession was precipitated by the implosion of overheated housing markets in California and throughout the United States, the resulting balance sheet deterioration of financial firms and households, and the near collapse of world credit markets.

California’s recession started even earlier than the nation’s and was deeper. Unemployment in the state—under 5 percent as recently as 2006—has topped 12 percent for over a year now, as 1.4 million jobs have disappeared. In 2009, personal income in California dropped 2.4 percent—the first annual decline since 1933.

Slow Recovery Expected to Continue. The latest evidence suggests that the state and national economies continue their very slow recovery from this staggering economic drop–off. Our economic forecast—summarized in Figure 1—generally reflects the current consensus that the state and national economies will continue to recover slowly and sluggishly in the coming years.

Figure 1

The LAO’s Economic Forecast

(November 2010)

|

|

Actual

|

Estimated

|

|

Forecast

|

|

|

2009

|

2010

|

|

2011

|

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

2016

|

|

United States

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Percent change in:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Real Gross Domestic Product

|

–2.6%

|

2.6%

|

|

2.2%

|

3.1%

|

2.9%

|

2.8%

|

3.1%

|

2.8%

|

|

Personal Income

|

–1.7

|

2.8

|

|

3.2

|

3.9

|

4.3

|

5.5

|

5.4

|

5.7

|

|

Wage and Salary Employment

|

–4.3

|

–0.5

|

|

0.9

|

2.2

|

2.2

|

1.5

|

1.4

|

1.2

|

|

Consumer Price Index

|

–0.3

|

1.6

|

|

1.6

|

1.9

|

2.0

|

2.1

|

2.1

|

2.1

|

|

Unemployment Rate (percent)

|

9.3

|

9.7

|

|

9.6

|

9.1

|

8.3

|

7.9

|

7.3

|

6.9

|

|

Housing Permits (thousands)

|

554

|

596

|

|

789

|

1,243

|

1,465

|

1,565

|

1,689

|

1,686

|

|

California

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Percent change in:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Personal Income

|

–2.4

|

2.8

|

|

3.5

|

4.3

|

4.8

|

5.7

|

5.9

|

5.7

|

|

Wage and Salary Employment

|

–6.0

|

–1.7

|

|

0.7

|

2.2

|

2.4

|

1.8

|

2.0

|

1.3

|

|

Consumer Price Index

|

–0.4

|

1.6

|

|

1.6

|

1.9

|

2.0

|

2.1

|

2.1

|

2.1

|

|

Unemployment Rate (percent)

|

11.4

|

12.5

|

|

11.9

|

10.5

|

9.1

|

8.2

|

7.1

|

6.6

|

|

Housing Permits (thousands)

|

34

|

42

|

|

67

|

79

|

99

|

113

|

121

|

121

|

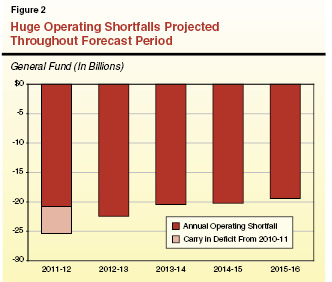

The U.S. Economy

Slower Recovery Than Previously Expected. Our recent economic forecasts already assumed a slow recovery, compared to past economic rebounds. Following the deep 1981–82 recession, for example, the U.S. economy bounced right back—with real gross domestic product (GDP) growing 4.5 percent in 1983 and 7.2 percent in 1984. Our updated forecast, by contrast, assumes that real GDP growth will be 2.6 percent in 2010, 2.2 percent in 2011, and no higher than 3.1 percent in any of the years between now and 2016. (Figure 2 summarizes our forecasts of quarterly changes in GDP.) Unemployment—now 9.6 percent nationally—is forecast to remain above 9 percent through 2012. Our forecasts of U.S. economic growth in 2011 and 2012 are somewhat lower than our forecasts from the past year.

What Is Causing the Slow Recovery? The slow recovery results from a combination of (1) excess inventories of residential and commercial real estate, (2) severely depressed economic confidence among both individuals and firms, and (3) for many consumers, a considerably weakened financial capacity to spend and invest. Consumers are attempting to restore their personal finances amidst the weak labor markets and diminished housing wealth. Credit remains very tight. While businesses have been spending more in recent quarters to address equipment, software, and other needs they deferred during the recession, they remain very reluctant to hire. The construction industry remains flat on its back—with few immediate prospects—due to the massive fall in residential and commercial real estate markets. While massive fiscal stimulus from the federal government helped cushion the fall, the 2009 stimulus program spending will taper off in the coming quarters, and the likelihood that Congress will enact additional fiscal stimulus appears remote. The Federal Reserve continues to take actions to stimulate the economy, but, with interest rates already at very low levels, its ability to achieve much in this regard is limited.

“Double–Dip” Recession Not Likely. While our economic and revenue forecasts reflect very modest assumptions about near–term growth, they are by no means a worst–case scenario. A minority of economic commentators have suggested that a double–dip recession—another period of diminished economic output—is possible due to the coming declines of federal economic stimulus, continued weakness in consumer spending, turmoil in the world’s sovereign debt and currency markets, and other factors. Our forecast reflects the consensus view that a double–dip recession will not occur. While employment, personal income, output, and housing permit growth, among other measures, are very weak by historical standards during a recovery, they are not shrinking. Similarly, while we expect low inflation through 2015–16, we do not forecast a period of deflation in the U.S. economy. In large part, our economic outlook reflects the view that some key economic measures (such as construction activity) have fallen so far that there is little room to fall even more.

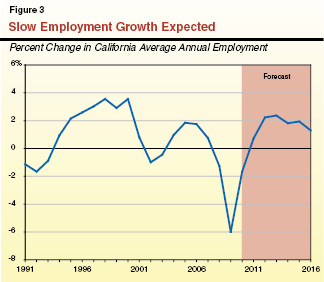

The California Economy

Employment Losses Subsiding. While U.S. employment has dropped about 5 percent since 2007, employment in California has declined 9 percent (1.4 million jobs). In 2010, however, the level of job losses in the state has been subsiding—a trend we expect to continue. We forecast that California will begin to experience a net increase in employment again in early 2011, causing unemployment to creep below 12 percent later in the calendar year. We expect employment in the state to grow by only about 100,000 jobs during 2011—a slower level of job growth for the year than in any of our recent forecasts. In 2012, we project slow employment growth in the state, a trend that should keep unemployment at or above 10 percent for much of that year. Growth in later years also remains fairly sluggish, as shown in Figure 3. Total employment in California does not return to its 2007 pre–recession levels in our forecast until 2016.

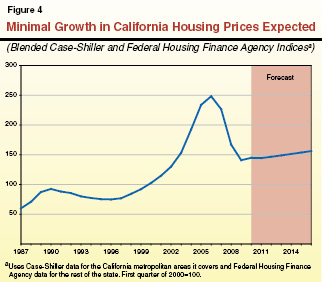

Housing Weakness Casts Formidable Shadow Over Economy. The main cause of the economic implosion of recent years has been the housing market. For now, at least, the collapse of California’s residential housing sector appears to have ended. As depicted in Figure 4, however, our forecast for California housing prices shows a very weak recovery—with minimal average gains in prices through 2016. While house prices now are more affordable—particularly in light of low mortgage interest rates—credit remains very tight. A large (but difficult to measure) “hidden inventory” of homes in default or facing foreclosure heavily influences our forecast. While residential building permits are up in 2010, they are still below 2008 levels—which, at the time, was the worst year in recent memory. Our forecast, as shown in Figure 1, expects housing permits to continue to grow slowly. Commercial building also continues to be exceptionally weak. For all of these reasons, California’s construction sector—having endured a crushing 40 percent employment decline since 2007—is not on track to regain its pre–recession strength in the foreseeable future.

Personal Income Poised to Rise With Job Growth. As job growth resumes, personal income in the state rebounds in our forecast—first, fairly slowly in 2011 and 2012, and then with some increasing strength thereafter. By 2014, we expect annual personal income growth for California in the 5.7 percent to 5.9 percent range—a level consistent with what we would consider a healthy growth rate for the state in the long run. Gradually climbing interest rates contribute to much stronger growth in dividends, interest, and rent income in the later years of our forecast. Government benefits also grow in the later years of our forecast, buoyed by growth in the aging “baby boom” population and, to some extent, the implementation of federal health care reform. All of these factors should help households in California continue to repair their finances, boost consumer confidence, and contribute to several years of increased consumption.

Revenue Projections

California’s General Fund is supported by revenues from a variety of taxes, fees, licenses, interest earnings, loans, and transfers from other state funds. About 90 percent of the total, however, is derived from the state’s “big three” taxes—the personal income tax (PIT), the sales and use tax (SUT), and the corporate income and franchise tax (CT). A summary of our revenue projections is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5

LAO General Fund Revenue Forecast

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Revenue Source

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

2015–16

|

|

Personal income tax

|

$44,575

|

$46,731

|

$44,252

|

$47,909

|

$50,868

|

$54,072

|

$57,507

|

|

Sales and use tax

|

26,741

|

27,310

|

25,370

|

27,725

|

29,137

|

30,397

|

31,622

|

|

Corporation tax

|

9,500

|

10,418

|

8,567

|

8,125

|

8,531

|

9,255

|

9,963

|

|

Subtotal, “Big Three”

|

($80,816)

|

($84,460)

|

($78,189)

|

($83,760)

|

($88,536)

|

($93,724)

|

($99,092)

|

|

Percent change

|

5.4%

|

4.5%

|

–7.4%

|

7.1%

|

5.7%

|

5.9%

|

5.7%

|

|

Insurance tax

|

$2,020

|

$2,033

|

$2,060

|

$2,093

|

$2,129

|

$2,168

|

$2,223

|

|

Vehicle license fee

|

1,380

|

1,428

|

159

|

34

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Estate tax

|

—

|

850

|

1,838

|

1,988

|

2,150

|

2,325

|

2,515

|

|

Sales of fixed assets

|

—

|

1,286

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

7

|

7

|

|

Other revenues

|

2,378

|

2,205

|

2,136

|

1,861

|

2,072

|

2,233

|

2,342

|

|

Net transfers and loans

|

447

|

1,021

|

–853

|

–1,014

|

–180

|

21

|

18

|

|

Total Revenues and Transfers

|

$87,041

|

$93,283

|

$83,530

|

$88,723

|

$94,708

|

$100,478

|

$106,197

|

|

Percent change

|

5.2%

|

7.2%

|

–10.5%

|

6.2%

|

6.7%

|

6.1%

|

5.7%

|

Figure 6 shows the differences between our forecasts of 2009–10 and 2010–11 revenues, as compared with those assumed in the 2010–11 budget package. For 2009–10 and 2010–11 combined, we now project that the big three and other revenues will be $447 million below the budget package assumptions. In addition, due to our assumption that passage of Proposition 22 will prevent the borrowing of some transportation funds, our net transfer and loans forecast is $378 million lower. In total, for 2009–10 and 2010–11 combined, our revenue and transfer forecast is $826 million below that assumed in the 2010–11 budget package.

Figure 6

November 2010 LAO Revenue Estimates Compared With 2010–11 Budget Package

(General Fund, In Millions)

|

Revenue Source

|

2009–10

|

|

2010–11

|

|

LAO November Forecast

|

Budget Package

|

Difference

|

LAO November Forecast

|

Budget Package

|

Difference

|

|

Personal income tax

|

$44,575

|

$44,820

|

–$245

|

|

$46,731

|

$47,127

|

–$396

|

|

Sales and use tax

|

26,741

|

26,618

|

123

|

|

27,310

|

27,044

|

266

|

|

Corporation tax

|

9,500

|

9,275

|

225

|

|

10,418

|

10,897

|

–479

|

|

Subtotal, “Big Three”

|

($80,816)

|

($80,713)

|

($103)

|

($84,460)

|

($85,068)

|

(–$608)

|

|

Other revenues

|

$5,778

|

$5,760

|

$18

|

|

$7,802

|

$7,762

|

$40

|

|

Net transfers and loans

|

447

|

447

|

—

|

|

1,021

|

1,399

|

–378

|

|

Total Revenues and Transfers

|

$87,041

|

$86,920

|

$121

|

$93,283

|

$94,230

|

–$947

|

Personal Income Tax

End of Temporary Tax Increases Affects 2011–12 Forecast. We estimate that PIT revenue will increase from its 2009–10 level of $44.6 billion to $46.7 billion in 2010–11. It will then drop off to $44.3 billion in 2011–12 as the temporary 0.25 percentage point rate increase and dependent credit reduction enacted in February 2009 expire at the end of calendar year 2010. These temporary tax increases contribute over $2 billion to PIT revenues in 2010–11. We project PIT collections to increase steadily in the out years as the economy continues to recover, but we do not expect collections to exceed their 2007–08 level of $54.2 billion until 2015–16.

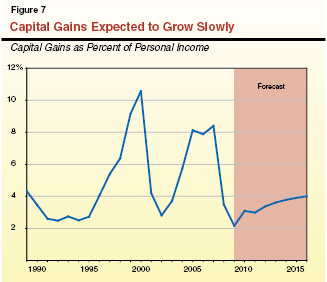

PIT Forecast Marked by Capital Gains, Federal Tax Uncertainties. Capital gains are important for PIT projections because these gains are concentrated among taxpayers who pay the highest marginal PIT tax rates. As Figure 7 shows, capital gains fluctuate wildly relative to personal income depending on the state of asset markets, and this always makes them difficult to forecast. They peaked at $120 billion in tax year 2000 at the height of the dot–com bubble but fell to $33 billion in 2002. Similarly, capital gains peaked at $132 billion at the height of the housing bubble in 2007, only to fall to $56 billion in 2008. We estimate that capital gains fell further to $34 billion in 2009. Our forecast reflects modest future growth in capital gains through 2016 due to improving stock prices and slowly increasing real estate values. If our forecast is off, this could have a significant effect on PIT collections and General Fund revenues. For example, for each $10 billion increase in capital gains, General Fund revenues increase by approximately $800 million.

Currently, there are two big variables that makes us particularly uncertain about capital gains. First, there is a large stock of unused losses. Taxpayers racked up far more capital losses than they could claim on returns in 2008 and probably again in 2009. Accordingly, we expect that these unused losses will hinder revenue growth for many years as taxpayers use 2008 and 2009 losses to offset future gains.

Second, there is significant tax policy uncertainty at the federal level regarding congressional action on expiring tax cuts. In 2001 and 2003, lower tax rates, including capital gains tax rates, were adopted, and these federal tax rate reductions are to expire this year. Our forecast assumes that this higher federal tax rate on capital gains returns to its higher level in 2011. This would cause some taxpayers to take gains in 2010 that otherwise would be taken in 2011. The actions Congress takes could affect the timing of these capital gain receipts and other economic and revenue variables in different ways. It seems as though the federal tax picture will be somewhat clearer by the time the new Governor releases his budget proposal in January.

Sales and Use Tax

End of Temporary Tax Increase and Proposition 26 Affect 2011–12 Forecast. In 2010–11, we expect SUT receipts of $27.3 billion, a 2.1 percent increase over the prior year. The 1 percent temporary SUT rate increase adopted in 2009—which contributes $4.7 billion of SUT revenue in 2010–11—will expire on June 30, 2011. For 2011–12, SUT revenues are projected to fall to $25.7 billion, reflecting the net effect of this rate drop, projected growth in the SUT taxable sales base of nearly 7 percent, and our assumption that voter approval of Proposition 26 on November 2, 2010 will undo the “fuel tax swap” adopted earlier this year. Under the terms of that measure, the gasoline sales tax is reinstated in November 2011, thereby also increasing General Fund spending on transportation. After 2011–12, taxable sales are expected to grow by 4 percent to 7 percent annually.

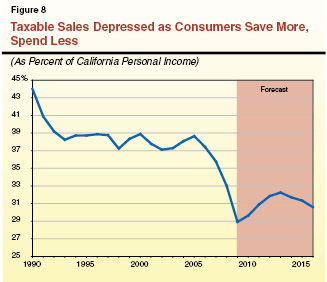

Taxable Sales Bottomed Out Last Year and Now Are Recovering. The main determinant of SUT receipts is taxable sales. About two–thirds of taxable sales result from retail spending by consumers, including a significant portion on light vehicles and trucks. Other important categories of taxable sales are the purchase of building materials involved in new construction and business–to–business transactions, where a business is the item’s final consumer. Taxable sales in California appear to have hit bottom in the second half of 2009, and are bouncing back.

As shown in Figure 8, overall consumer spending remains low relative to the levels of recent decades, when viewed as a percentage of personal income. It appears there has been a long–term trend toward lower taxable sales, relative to personal income, which has been influenced by: (1) the major recessions of the early 1990s and 2007–2009; (2) a trend toward more consumption of nontaxable services and other products (such as those purchased online, for which the collection of sales and use taxes is more difficult); and (3) increased household savings, particularly in the last few years.

Corporate Tax

Corporate Tax Forecast to Bottom Out in 2012–13 Before Rebounding. The CT receipts for 2009–10 are estimated to have totaled $9.5 billion, virtually unchanged from the previous fiscal year. Due to the slow recovery and policy changes enacted by the Legislature, we project CT receipts will fall sharply in 2011–12 and 2012–13. The tax bottoms out in 2012–13 at around $8 billion before rebounding back to around $10 billion by 2015–16.

Corporate Profit Rebound Does Not Necessarily Translate Into Higher Revenues. The main factor underlying CT receipts is the level of corporate profits that California taxes. California’s corporate profits, in turn, reflect the economic conditions facing Californians, as well as national and international economic conditions. At times, higher profits do not fully translate into higher CT receipts because these higher profits also make it possible for businesses to use more deductions and credits. Precise data on California taxable profits for 2009 and 2010 are not yet available, but our forecast assumes that corporate profits hit bottom in 2008–09 and rebounded rapidly in 2009–10. Profits in the final years of our forecast grow at about 5 percent each year.

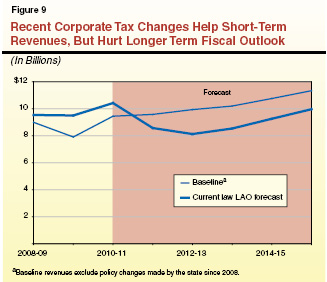

Policy Changes Reduce Long–Term Revenues. Policy changes made over the past few years have significant impacts on corporate tax receipts over the forecast period. As shown in Figure 9, increases of CT receipts due to policy changes negated what otherwise would have been a significant reduction in CT receipts in 2009–10. Recent tax policy changes also will boost receipts in 2010–11 by increasing collections by a net amount of around $1 billion. For the remainder of the forecast period, however, these same policy changes diminish CT receipts by between $1 billion and $2 billion each year. The major policy changes affecting the forecast include:

- Changes in Multistate Business Taxation. The elective single sales factor—the new option for businesses to annually choose which method is used to determine California taxable income—and associated tax law changes are estimated to reduce General Fund CT revenues by up to $1 billion per year within a few years.

- Revenue Accelerations. The Legislature has enacted several measures over the last couple of years that will allow the state to collect revenues earlier and delay the use of tax deductions or credits. The accelerations include the suspensions, for 2008 through 2011, of larger businesses’ use of net operating loss deductions. Recently enacted penalties on corporate taxpayers who are found to have significantly underpaid their taxes also serve to accelerate CT collections. This occurs as businesses try to avoid the penalties by paying upfront some of the tax they might have been forced to pay later following an audit. In addition, legislation limited the amount of tax credits a corporation could use in 2008 and 2009 to 50 percent of its tax liability for those years. This boosted near–term receipts but leads to increased use of those credits in 2010 and beyond. These changes, collectively, are estimated to bring in around $1.2 billion in 2010–11 but have the effect of decreasing CT revenues after 2011–12.

- Expanded Credit Use. Recent legislation also affected the use of tax credits. Changes in this area include the creation of new temporary tax credits for qualified employment and film production. Also, credits are now easier to use under a law that allows transfers of certain credits between companies that are treated as parts of a single unit for tax purposes. These changes reduce revenues by up to $500 million per year throughout the forecast period.

Other Revenues and Transfers

Estate Tax Highly Uncertain and Could Swell 2011–12 Problem by $2.7 Billion. Above, we discussed how congressional action in the coming months could affect capital gains and PIT receipts. In addition, congressional action or inaction on estate taxes could significantly affect the state’s ability to receive any of the $850 million of current–law estate tax receipts we project for 2010–11 (a half–year of receipts), as well as around $2 billion of annual receipts in each subsequent year of the forecast. As we discussed in prior reports, a 2002 federal law phased out estate taxes so that, by 2010, the estate tax was eliminated entirely. In 2011, this provision sunsets so that estate tax laws revert back to 2001 law—which means that tax rates would return to 2001 levels and the state pickup tax is restored. This pickup tax reduces federal estate taxes by the amount of state taxes levied on each estate, up to a certain level. As a result, many states—including California—set state tax levels at the maximum exemption level under federal law. There have been considerable efforts in recent years to change this current federal law to permanently limit both the federal and state estate tax. If Congress were to act to change the federal law, it appears there is a good chance the pickup tax exemption would not be restored. In this event, the 2011–12 budget problem would increase by $2.7 billion (recognizing the effects of both the half–year projected estate tax receipts of $850 million in 2010–11 and the first full year of receipts projected to be $1.8 billion in 2011–12). Later budget problems would grow by up to $2 billion per year above our forecast. (These amounts do not account for any Proposition 98 interactions.)

Fixed Asset Sales Slightly Above Enacted Budget Forecast in 2010–11. Assuming that recently announced sales of state office buildings and the Orange County Fairgrounds proceed as planned, our forecast projects $1.3 billion of one–time General Fund revenue in 2010–11. This total is about $100 million higher than assumed in the 2010–11 budget package.

End of Temporary Vehicle License Fee (VLF) Increase Affects 2011–12 Forecast. The temporary VLF increase enacted as part of the 2009–10 budget package expires at the end of 2010–11. This temporary increase generates $1.4 billion of revenue for the General Fund in 2010–11. Thereafter, the General Fund VLF rate declines again to zero in our forecast, although small amounts of VLF payments trickle in during subsequent fiscal years due to late payments. Figure 10 summarizes the VLF and other revenues that the state has received from the temporary tax package.

Figure 10

Estimated Revenues From Temporary Tax Increases Enacted as Part of the 2009–10 Budget Package

(In Billions)

|

|

2008–09

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

|

Sales and use tax—1 percentage point increase

|

$1.1

|

$4.4

|

$4.7

|

|

Personal income tax—dependent credit decrease

|

0.1

|

1.2

|

1.1

|

|

Personal income tax—0.25 percentage point increase

|

0.8

|

1.8

|

1.0

|

|

Vehicle license fee—0.5 percentage point increase

|

0.2

|

1.4

|

1.4

|

|

Totals

|

$2.2

|

$8.7

|

$8.3

|

Special Fund Loans Dominate the General Fund Transfers Forecast. In addition to tax, fee, and other revenues, the General Fund receives transfers from the state’s special funds and transfers money out to those same special funds. During the forecast period, the state’s transfers are to be dominated by loans received from special funds (the major component of the $1.4 billion of net transfers assumed in the budget package for 2010–11) and loan principal repayments back to special funds ($853 million of projected net transfers out in 2011–12, $1 billion in 2012–13, and $180 million in 2013–14). Our forecast assumes that approval of Proposition 22 on November 2, 2010 eliminates the possibility of the state borrowing $378 million of funds from transportation accounts assumed in the 2010–11 budget package. This reduces net transfers and loans in 2010–11 to $1 billion in our projections.

Demographic Projections

Department of Finance (DOF) Population Estimates Differ From Census Estimates. The DOF estimates that California’s July 1, 2009 population was 38.5 million and that the state’s population increased by 1 percent (or greater) in each year between 2001 and 2008 and by 0.93 percent in 2009. By contrast, the Census Bureau—in its annual estimates released prior to next year’s release of 2010 Census data—believed that California’s July 1, 2009 population was 37.0 million. The Census estimates differ from DOF’s because they assume that California’s net annual population growth rate has been somewhat under 1 percent in several years during the past decade. Data from the 2010 Census to be released in March 2011 should help resolve this demographic dispute.

Economic Downturn Probably Has Resulted in Fewer Newcomers. Relatively poor economic performance in California can make it less attractive for residents of other state and countries to migrate here. Based on historical experience, our population model suggests that the recent trend of Californians leaving the state probably is accelerating and will continue to do so through 2011. At the same time, the economic downturn will depress net international migration into California for the next several years. Births increase slowly as women continue to delay childbirth until later ages. Accordingly, as shown in Figure 11, our office estimates that total annual population growth in California will be 0.55 percent in 2010 and projects that population growth will be under 1 percent annually through 2015.

Figure 11

LAO’s California Demographic Forecasta

(In Thousands)

|

|

2009a

|

2010

|

|

2011

|

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

2016

|

|

Totals (July 1st)

|

38,488

|

38,699

|

|

38,863

|

39,137

|

39,453

|

39,803

|

40,191

|

40,643

|

|

Percent change

|

0.93%

|

0.55%

|

|

0.43%

|

0.70%

|

0.81%

|

0.89%

|

0.98%

|

1.12%

|

|

Change in population:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Births

|

553

|

548

|

|

527

|

526

|

534

|

542

|

549

|

557

|

|

Deaths

|

–237

|

–236

|

|

–241

|

–245

|

–249

|

–253

|

–257

|

–261

|

|

Net domestic migration

|

–173

|

–190

|

|

–225

|

–121

|

–98

|

–85

|

–54

|

–12

|

|

Net foreign migration

|

210

|

89

|

|

104

|

114

|

130

|

145

|

152

|

167

|

|

Net Change

|

353

|

211

|

|

165

|

274

|

316

|

349

|

389

|

451

|

Baby Boomers Will Swell Over–65 Population. Baby boomers born immediately after the end of World War II began to reach the age of 65 earlier this year. As this huge population cohort continues to reach this age, this group will swell in the coming years. We project the over–65 population generally will grow over 4 percent per year throughout our forecast period.

Modest Growth for K–12 and College–Age Population Groups. Our forecast assumes the K–12 population grows by 0.2 percent or less through 2013–14 before increasing slightly more rapidly. The 18–24 college age group is projected to increase very modestly through 2013 before beginning to decline thereafter. During the forecast period, this college–aged group largely consists of the offspring of the relatively small “Generation X”—those born in the two decades after the baby boom.

Chapter 3

Expenditure Projections

In this chapter, we discuss our General Fund expenditure estimates for 2009–10 and 2010–11, as well as our projections for 2011–12 through 2015–16. Figure 1 shows our forecast for major General Fund spending categories for all of these years. Below, we first discuss projected general budgetary trends and then discuss in more detail our expenditure projections for individual major program areas.

Figure 1

Projected General Fund Spending for Major Programs

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

Estimates

|

|

Forecast

|

Average Annual

Growth From

2011–12 to

2015–16

|

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

2015–16

|

|

Education

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

K–14–Proposition 98

|

$35,669

|

$36,209

|

|

$34,184

|

$36,733

|

$38,847

|

$41,058

|

$43,270

|

6.1%

|

|

Proposition 98 QEIA and Settle–Up

|

300a

|

—a

|

|

750

|

750

|

750

|

750

|

472

|

–10.9

|

|

CSU

|

2,288

|

2,433

|

|

2,646

|

2,646

|

2,646

|

2,646

|

2,646

|

—

|

|

UC

|

2,449

|

2,711

|

|

2,815

|

2,815

|

2,815

|

2,815

|

2,815

|

—

|

|

Student Aid Commission

|

1,019

|

1,079

|

|

1,258

|

1,334

|

1,413

|

1,499

|

1,609

|

6.4

|

|

Health and Social Services

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Medi–Cal

|

10,136

|

12,595

|

|

17,642

|

18,831

|

20,291

|

22,101

|

23,976

|

8.0

|

|

CalWORKs

|

1,995

|

2,143

|

|

3,041

|

3,140

|

3,130

|

2,960

|

2,676

|

–3.1

|

|

SSI/SSP

|

2,951

|

2,954

|

|

3,033

|

3,116

|

3,200

|

3,287

|

3,379

|

2.7

|

|

IHSS

|

1,488

|

1,419

|

|

1,732

|

1,835

|

1,903

|

1,973

|

2,045

|

4.2

|

|

Developmental Services

|

2,420

|

2,541

|

|

3,124

|

3,292

|

3,473

|

3,671

|

3,885

|

5.6

|

|

Mental Health

|

1,666

|

1,837

|

|

2,142

|

2,193

|

2,247

|

2,305

|

2,367

|

2.5

|

|

Other major programsb

|

3,185

|

2,823

|

|

3,327

|

3,460

|

3,518

|

3,457

|

3,751

|

3.1

|

|

Corrections and Rehabilitation

|

7,718

|

9,281

|

|

9,034

|

9,124

|

9,371

|

9,546

|

9,792

|

2.0

|

|

Judiciary

|

419

|

1,649

|

|

2,016

|

2,013

|

2,012

|

2,012

|

2,012

|

—

|

|

Proposition 1A Loan Costs

|

15

|

91

|

|

91

|

1,986

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Infrastructure Debt Servicec

|

5,383

|

5,752

|

|

6,926

|

7,239

|

8,378

|

8,848

|

8,705

|

5.9

|

|

Other Programs/Costs

|

7,934

|

6,988

|

|

8,995

|

10,658

|

11,155

|

11,755

|

12,230

|

8.0

|

|

Totals

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5.2%

|

|

Percent Change

|

|

6.3%

|

|

11.1%

|

8.2%

|

3.6%

|

4.8%

|

4.1%

|

|

General Fund Budget Trends

2010–11 Outlook

General Fund expenditures in 2010–11 are billions of dollars below their normal levels due to one–time or temporary actions, including (1) billions of dollars in federal stimulus funds received, (2) suspension of Proposition 98, and (3) funding shifts to non–General Fund sources. However, General Fund expenditures are forecast to increase from $87 billion in 2009–10 to $92.5 billion in 2010–11—an increase of 6.3 percent. This is much more than the budgeted increase of 0.2 percent that was expected when the budget was passed in October—due principally to our projection that a significant amount (around $3.5 billion) of assumed federal funds will not be secured. In addition, we project that several major programs—such as the prison system, In–Home Supportive Services (IHSS), and employee compensation—will be unable to achieve the full amount of budgeted reductions.

Expenditure Growth During the Forecast Period

Sharp Growth in 2011–12 as One–Time Savings Measures Expire. In 2011–12, our forecast shows General Fund spending climbing by 11 percent. This is principally the result of billions of dollars of one–time saving measures expiring. For example, Medi–Cal expenditures will increase by about $5 billion—the majority of this is due to expiring federal funds.

Lower Growth Projected After 2011–12. Our forecast shows General Fund spending growing by 8.2 percent in 2012–13, 3.6 percent in 2013–14, 4.8 percent in 2014–15, and 4.1 percent in 2015–16. As shown in Figure 1, this equates to an average annual growth rate of 5.2 percent between 2011–12 and 2015–16—slightly higher than the forecasted rate of personal income growth in the state during that period. The period is characterized by consistently high rates of growth in two areas that represent over half of the General Fund budget in 2015–16: (1) Proposition 98 spending for K–14 education, and (2) Medi–Cal. Although Proposition 98 spending for K–14 education is forecasted to drop in 2011–12, spending over the following years averages 6 percent annual growth as the economy continues its expected recovery. The largest growth in our forecast (8 percent) occurs in Medi–Cal due to growth in caseload and health care costs and, in the last two years of the forecast, the impact of federal health care reform. The remainder of the budget is forecast to grow at a modest 3.5 percent over the forecast period. This modest growth is due in part to the stated legislative policy of having no automatic cost–of–living adjustments (COLAs) or inflation adjustment for programs (as discussed in Chapter 1). For instance, our forecast shows no growth in General Fund appropriations to the universities or the courts after 2011–12.

Proposition 98—K–14 Education

State budgeting for K–14 education is governed largely by Proposition 98, passed by the voters in 1988. The measure, later modified by Proposition 111 in 1990, establishes a minimum funding requirement, commonly referred to as the “minimum guarantee,” for K–14 education. Both state General Fund and local property tax revenues apply toward meeting the minimum guarantee. Proposition 98 monies support child care, preschool, K–12 education, and the California Community Colleges—accounting for about 70 percent of total funding for these programs. (K–14 education funding also comes from the federal government, other state sources, and various local sources.)

Calculating the Minimum Guarantee. The Proposition 98 minimum guarantee is determined by one of three tests set forth in the Constitution. These tests are based on several inputs, including changes in K–12 average daily attendance, per capita personal income, and per capita General Fund revenue. Though the calculation of the minimum guarantee is formula driven, a supermajority of the Legislature can override the formulas and provide less funding than the formulas require. This happened in 2010–11, with the Legislature suspending Proposition 98 and providing less funding than otherwise required. As a result of the suspension, the state created an out–year Proposition 98 obligation referred to as a “maintenance factor.” When growth in state General Fund revenues is healthier (as determined by a specific formula set forth in the Constitution), the state is required to provide additional funding (make a maintenance factor payment) to build up K–14 funding to the level it otherwise would have been absent the earlier reduction. In essence, the maintenance factor allows the state to attain near–term savings without affecting the long–run level of K–14 support.

Proposition 98 Forecast

Minimum Guarantee Drops in 2011–12 Before Rebounding. The top part of Figure 2 shows our projections of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee throughout the forecast period. For 2011–12, we project the minimum guarantee will be about $2 billion lower than the 2010–11 spending level due to the expiration of tax increases that temporarily raised tax revenues in 2009–10 and 2010–11. For the rest of the forecast period, we project steady increases in the minimum guarantee of $2 billion to $3 billion each year. Local property tax revenues modestly grow each year of the forecast period. In the last year of the forecast period, we project the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee and local property tax revenues would finally be higher than their pre–recession levels.

Figure 2

Proposition 98 Forecast

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

2015–16

|

|

Minimum Guarantee

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$36,465

|

$34,184

|

$36,733

|

$38,847

|

$41,058

|

$43,270

|

|

Local property tax

|

13,193

|

13,272

|

13,598

|

14,014

|

14,559

|

15,231

|

|

Totals

|

$49,658a

|

$47,456

|

$50,331

|

$52,861

|

$55,617

|

$58,501

|

|

Percent change

|

|

–4.4%

|

6.1%

|

5.0%

|

5.2%

|

5.2%

|

|

Proposition 98 “Test”

|

2

|

1

|

2

|

2

|

2

|

1

|

|

Proposition 98 Obligations

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Maintenance Factor Created/Paid (+/–)

|

$475

|

$3,929

|

–$1,229

|

–$463

|

–$392

|

–$611

|

|

Outstanding Maintenance Factor

|

9,489

|

13,749

|

12,996

|

13,067

|

13,259

|

13,189

|

|

Key Factors

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

K–12 average daily attendance

|

–0.12%

|

0.14%

|

0.20%

|

0.17%

|

0.33%

|

0.50%

|

|

CCC full–time equivalent students

|

1.40

|

1.00

|

1.00

|

1.00

|

1.00

|

1.00

|

|

Per capita personal income (Test 2)

|

0.62

|

3.33

|

3.26

|

3.93

|

4.13

|

3.57

|

|

Per capita General Fund (Test 3)

|

5.92

|

–7.31

|

6.54

|

5.42

|

5.42

|

5.12

|

|

K–14 COLA

|

–0.39

|

1.78

|

1.34

|

1.76

|

2.23

|

2.37

|

|

Year–to–Year Change

|

|

–$1,946

|

$2,875

|

$2,530

|

$2,756

|

$2,884

|

|

Less Baseline Costs

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

K–14 COLA

|

|

–$864

|

–$663

|

–$883

|

–$1,144

|

–$1,252

|

|

K–14 attendance

|

|

–101

|

–124

|

–116

|

–206

|

–305

|

|

Backfill of one–time actions

|

|

–2,272

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Funds Available/Shortfall (+/–)

|

|

–$5,184

|

$2,088

|

$1,531

|

$1,406

|

$1,326

|

Maintenance Factor Obligation Grows in 2011–12, Remains Large Throughout Period. Figure 2 also shows both how much maintenance factor is created or paid in each year of the forecast period and the total amount of outstanding maintenance factor. As shown in the figure, we estimate the state will have an outstanding maintenance factor obligation of $9.5 billion at the end of 2010–11. Using the same maintenance factor assumptions as used to build the last three Proposition 98 budgets, $4 billion in new maintenance factor would be created in 2011–12—resulting in a total outstanding obligation of about $14 billion. During the remainder of the forecast period, the state would make relatively small maintenance factor payments each year. Because maintenance factor obligations grow (akin to an inflationary adjustment) and the required payments are small, we project the state would end the forecast period still having an outstanding maintenance factor obligation of more than $13 billion.