Executive Summary

Recent legislation authorized the Department of General Services (DGS) to sell and then lease back 11 state–owned office properties. The sale–leaseback is designed to free up the state’s equity in the buildings to provide one–time revenue for addressing the state’s current budgetary shortfall. The leaseback component would allow the state to retain use of the properties.

The DGS has initiated the process for selling and leasing back the properties and expects to select a buyer or buyers as early as the end of May. In order to maintain oversight of the process, the legislation requires DGS to report on the terms and conditions of any sale–leaseback to the Legislature’s fiscal committees 30 days prior to completing a transaction. During this 30–day period, the Legislature has an opportunity to review the transaction and determine whether the sale–leaseback is preferable to maintaining state–ownership of the buildings. In this report, we outline the key issues the Legislature will need to consider in comparing the sale–leaseback to the status quo.

Major Up Front Benefit…The major benefit of the sale–leaseback transaction is the one–time revenue from the sale of the buildings. Proceeds from the sale would first retire the bonds associated with the buildings, while the remainder would provide one–time revenue to the state’s General Fund. The 2010–11 Governor’s Budget estimates sale proceeds would provide $598 million to the General Fund. In the report, we find that the Governor’s estimate represents the low end of what the state could expect to receive and that one–time revenue could be $1.4 billion under more optimistic assumptions.

…But Higher Annual Costs. While the sale–leaseback would transfer the state’s costs and risk of owning the buildings to the new owner, the state would make ongoing lease payments to the new owner that would be greater than the amount the state currently spends to own and operate the buildings. We estimate leasing the facilities would cost $30 million more than ownership in the first year and continue to increase over time—eventually costing the state approximately $200 million more annually than maintaining ownership.

Evaluating the Transaction. In deciding whether to endorse the sale–leaseback during the 30–day review period, the Legislature will need to consider whether the benefit of the one–time revenue from selling the facilities would be large enough to compensate for the higher costs in subsequent years. After taking into account the one–time revenue that the state would receive in the first year and converting the future costs into today’s dollars, we estimate the transaction would cost the state between $600 million and $1.5 billion. The Legislature will need to weigh how these costs compare to other alternatives for addressing the state’s budget shortfall. In our view, taking on long–term obligations—like the lease payments on these buildings—in exchange for one–time revenue to pay for current services is bad budgeting practice as it simply shifts costs to future years. Therefore, we encourage the Legislature to strongly consider other budget alternatives. And, more specifically, we recommend the Legislature reject the sale–leaseback if the sales revenue is at the lower end of the range presented in this report—near the Governor’s revenue estimate, for example—as the costs would be equivalent of long–term borrowing at double digit interest rates.

Background

Chapter 20, Statutes of 2009 (ABX4 22, Evans), authorizes the DGS to (1) sell 11 state–owned office buildings and (2) lease the buildings back from the new owners through a long–term lease. The sale–leaseback transaction was one component of a larger proposal from the Governor to extract revenue from the state’s real estate assets. Other components of the Governor’s state asset revenue proposal included in Chapter 20 were the sale of the Orange County Fairgrounds and allowing DGS to arrange long–term ground leases for underutilized state properties. Each proposal was intended to provide revenue for addressing the state’s budgetary shortfalls. This report addresses the sale–leaseback component of Chapter 20.

The Sale–Leaseback Transaction. A sale–leaseback is a real estate transaction in which the owner sells a property and then leases it back from the buyer. The purpose of a sale–leaseback is to free up the original owner’s equity while allowing the owner to retain use of the property. The leaseback component is essential to the state since it will continue to need space in the buildings proposed for sale. As described in the nearby box, a sale–leaseback transaction is much different than a traditional asset sale.

Selling the Properties in Today’s Real Estate Market

Selling at a Low Point in the Market Will Result in Less Revenue… The commercial real estate market has experienced a significant decline during the recession. Increasing vacancy rates have caused commercial building values to drop across the state since 2007. Accordingly, the state would be selling the buildings at a low point in the market and receive less revenue than it would have in previous years.

...But Also Lower Rent Payments. Although the state would not earn the same revenue that it might have in previous years, the state would also not have to pay the higher market rents of previous years when it leases the buildings back. Rental rates in all of California’s metropolitan markets have fallen significantly since 2007 as owners attempt to attract new tenants or retain current tenants. The lower rental rates would lessen the state’s long–term lease costs under a sale–leaseback.

Sale–Leaseback Should Be Attractive to Investors. Under the sale–leaseback proposal, the state would lease the entire properties for a term of at least 20 years. One advantage of pursuing a sale–leaseback in this market is that with the significant turnover and vacancy rates, there is considerable demand among institutional investors for real estate assets that offer such long leases and secure income streams. The state’s buildings would still represent some risk to the new owners depending upon their condition and age, but carry less risk than many other commercial properties that do not offer guaranteed occupancy. As a result, we would expect a competitive bidding environment for the state’s sale–leaseback properties. |

Timeline. The DGS has initiated the process for selling and leasing back the 11 state properties authorized in Chapter 20 (see Figure 1). The process started with DGS selecting the firm CB Richard Ellis (CBRE) through a competitive bidding process to serve as the broker for marketing and managing the sale–leaseback transaction. Next, DGS worked with CBRE to determine the marketing timeline and strategy, compile due diligence information on the properties, and prepare lease terms for the leaseback part of the transaction. As shown in the current timeline in Figure 2, CBRE officially placed the properties on the market—advertised as the “Golden State Portfolio”—on February 26. The bidding process began with potential buyers submitting initial offers on one or more of the properties in April. The DGS and CBRE will then evaluate the initial offers and invite potential buyers who submitted competitive initial offers to participate in a “best and final” round at the end of May. Assuming additional bidding rounds are not necessary, a decision on the buyer or buyers could occur as early as the end of May.

Figure 1

State Office Properties Authorized for Sale–Leaseback

|

Building

|

Location

|

|

Junipero Serra State Building

|

Los Angeles

|

|

Ronald Reagan State Building

|

Los Angeles

|

|

Elihu Harris Building

|

Oakland

|

|

California Emergency Management Agency Headquarters

|

Rancho Cordova

|

|

Attorney General Building

|

Sacramento

|

|

Capitol Area East End Complex

|

Sacramento

|

|

Department of Justice Building

|

Sacramento

|

|

Franchise Tax Board Complex

|

Sacramento

|

|

Public Utilities Commission Building

|

San Francisco

|

|

Earl Warren and Hiram Johnson Buildings (Civic Center)

|

San Francisco

|

|

Judge Rattigan Building

|

Santa Rosa

|

Figure 2

Sale–Leaseback Schedule

2010

|

|

|

|

February 26

|

Release of initial brochure and offering memorandum.

|

|

April 14

|

Deadline for potential buyers to submit initial offer.

|

|

April 23

|

Competitive buyers invited to participate in additional offer rounds.

|

|

May 20

|

Deadline for best and final bids.

|

|

May 28

|

Anticipated date of the selection of the buyer(s).

|

The Role of the Legislature. The legislation provides broad authority for DGS to determine the sale and lease terms that are “in the best interest of the state.” In order to maintain oversight of the process, however, the legislation requires DGS to report on the terms and conditions of the sale–leaseback to the Legislature’s fiscal committees 30 days prior to completing a transaction. This 30–day review period provides the Legislature an opportunity to review the transaction and determine if the state should enter into the agreement. The key policy question the Legislature will have to confront (if DGS successfully negotiates a deal) is whether the sale–leaseback is preferable to maintaining state ownership of the buildings. The purpose of this report is to outline the key issues for comparing the sale–leaseback to the status quo and suggest approaches for evaluating the sale–leaseback transaction.

Evaluating the Sale–Leaseback

Sale–leasebacks are fairly common in the private sector because the transaction can provide opportunities for companies to decrease their tax liability, improve their balance sheet, or gain capital to reinvest in the company. Fewer public sector entities have engaged in sale–leaseback transactions because most of the benefits experienced by the private sector do not apply to governments. Most government sale–leaseback transactions seek to generate revenue for either immediate budgetary solutions—similar to California—or to provide capital for investing in large projects. (More details on public entities’ use of sale–leasebacks are discussed in the nearby box.) Generating revenue from a sale–leaseback, however, also means the state would incur additional costs in later years as it pays rent to the new owners. Below, we discuss these two major considerations—one–time revenue and ongoing lease costs—that the Legislature would need to consider in evaluating the desirability of the proposed sale–leaseback. We then describe other factors concerning the transaction.

Sale–Leasebacks in the Public Sector

The most prevalent use of sale–leasebacks in the public sector is at the local government level. Governments pursuing sale–leasebacks typically want to extract the equity from their buildings in order to (1) fund new infrastructure projects or (2) balance current budget shortfalls. Using sale–leasebacks to invest in additional infrastructure projects is more common than using the revenue to meet operating expenses.

We found that most public entities structure their sale–leaseback transactions quite differently than California’s proposal. Specifically, in most sale–leasebacks the state or local government sells certificates of participation in the building to investors and remains responsible for all of the building’s services and costs. The certificates of participation carry a specified interest rate and maturity date, and repayments to the certificate holders represent the government’s “lease payments.” The government retains the risk of ownership under this type of sale–leaseback, but the building returns to state ownership when the certificates are paid off at the maturity date. In this way, it is more like borrowing with the property serving as collateral. For example, Arizona recently sold certificates of participation on 14 buildings it owns with maturity dates ranging from three to 20 years and an average interest rate of 4.6 percent to raise approximately $735 million to help address its budget deficit.

Examples similar to California, in which ownership of the building is permanently transferred to the new owner, are less common. The benefit of permanent transfer in a sale–leaseback is that it results in a higher sale price, but at the cost of indefinite lease payments that do not result in any equity. We found limited use of this type of sale–leaseback by some local governments as well as the United States and Canadian federal governments. |

Fiscal Considerations

One–Time Revenue

The most obvious benefit of the sale–leaseback transaction is the one–time revenue generated from selling the buildings. The sale proceeds would first go towards retiring the outstanding lease–revenue bonds associated with some of the buildings. After deducting a small amount to reimburse DGS and CBRE for their expenses in arranging the transaction, the remaining sale proceeds would be deposited in the state General Fund—reducing the need for expenditure reductions or revenue augmentations that would otherwise be needed to balance the state’s budget.

Budget Revenue Estimate. In January, the Governor’s 2010–11 budget proposal assumed net sale proceeds would provide $598 million for the General Fund over three years, with about half coming in 2010–11 and the remainder in the following two years. (This is slightly lower than earlier estimates of $660 million.) Upon learning that DGS intended to move forward with all of the property sales in the budget year, the administration testified that the roughly $300 million in sale proceeds originally scored as revenue in 2011–12 and 2012–13 should instead also be counted in 2010–11. As part of its actions in the 8th Extraordinary Session, the Legislature accepted this assumption. Consequently, the budget plan now assumes $598 million in 2010–11 revenue.

Wide Range of Revenue Possible. The Governor’s revenue estimate for the sale–leaseback is a preliminary projection. A wide range of revenue is possible given the variables involved in the transaction and the uncertainty of how investors will respond to the state’s offering. The main factor determining the amount potential buyers are willing to bid on the properties is the estimated income stream the buildings will provide to the buyer. The offering memorandum established the rental rates the state would pay and outlined expected operating costs for each building. The final bid price, however, will ultimately depend upon many factors including the bidding competition, perceptions of the buildings’ conditions, the economic climate, and expected returns.

Sale Price Could Be Higher. Considering each of these factors, we believe the Governor’s revenue estimate of $598 million represents the low end of what the state could receive from the sale–leaseback of the 11 properties. The Governor’s revenue estimate assumes a sale price of approximately $1.7 billion. (The difference of $1.1 billion between the sale price and net revenue would pay off the outstanding debt on the buildings and cover the transaction’s expenses.) Based upon the projected net operating income the buildings would generate as calculated in the offering memorandum, a sale price similar to the Governor’s estimate would mean that potential buyers bid cautiously. Alternatively, under a more optimistic scenario, the sale price could reach $2.5 billion, with net proceeds to the state of $1.4 billion after paying off the outstanding bonds. The final bid will ultimately depend upon each bidder’s independent assessment of the potential risk and cash flows associated with the sale–leaseback as well as the bidding competition. We would expect, however, that the sale price would fall within the range specified above and summarized in Figure 3. (Consistent with this expectation, the administration announced as we were going to press that it had received bids with amounts above the Governor’s budget assumption.)

Figure 3

Estimated One–Time Revenue From Sale

(In Billions)

|

Scenario

|

Purchase Price

|

Net Proceeds

|

|

Governor's budget

|

$1.7

|

$0.6

|

|

More optimistic

|

2.5

|

1.4

|

Increased Annual Costs

The main argument against pursuing a sale–leaseback on state office properties is that the 20 years to 50 years of lease payments under the sale–leaseback will likely cost more than the state would spend maintaining ownership of the buildings. Currently, the state covers all of the costs associated with the 11 office properties proposed for the sale–leaseback. These costs include debt service, utilities, building management, janitorial services, routine maintenance, special repairs, and security. As described in the nearby box, DGS is proposing a modified gross lease for the sale–leaseback in which a single lease payment to the new owner would replace most of these costs. As shown in Figure 4, making lease payments at the market rents proposed in the offering memorandum would cost the state approximately $30 million more in 2010–11 than the status quo of maintaining state ownership of the buildings. This assumes DGS is able to rapidly implement the staff reductions and internal restructuring necessary for the transition from state to private ownership. If the layoff and restructuring process takes some time and the state continues to incur some of these costs even after the sale, the first–year costs of the sale–leaseback would exceed the estimated $30 million—potentially over $10 million.

Figure 4

2010–11 Costs Under State Ownership and the Sale–Leaseback

(In Millions)

|

State Ownership

|

|

Sale–Leaseback

|

|

Debt service

|

$111.8

|

|

Lease payments

|

$198.4a

|

|

Operations and maintenance

|

54.7

|

|

Gas and electricity

|

12.7

|

|

Utilities

|

14.1

|

|

CalEMA operating costs

|

1.2

|

|

Special repairs

|

4.6

|

|

Sublease revenue

|

–0.9

|

|

Parking and lease revenue

|

–3.9

|

|

|

|

|

Total Cost

|

$181.3

|

|

Total Cost

|

$211.4

|

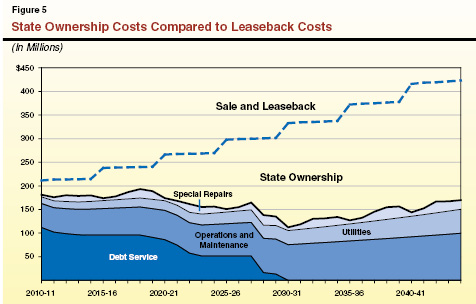

In subsequent years, the state’s cost of owning the buildings under the status quo would actually decrease over time as the various bonds on the facilities are retired. Some of these ownership savings would be offset by increasing costs for utilities, maintenance, special repairs, and renovations as the buildings age. As shown in Figure 5, however, we expect the declining debt service payments to outweigh the increasing operating costs so that the overall cost to the state of owning the buildings would steadily decrease until the bonds are completely paid off in 2028–29. (See the nearby box for a more detailed description of how we estimated ongoing costs.)

On the other hand, costs under the sale–leaseback would steadily increase due to the increases in base rent every five years and the annual operating cost increases included in the proposed leases. As shown in Figure 5, therefore, the estimated difference between the cost of maintaining ownership and the cost of leasing the buildings would increase over time. Considering this in terms of the state budget, the difference between the two alternatives is quite clear. Maintaining ownership of the buildings would lead to decreasing costs over time, lending a small contribution toward lessening the state’s structural budget deficit. Alternatively, the rising cost of leasing the facilities would lead to an increase in the state’s structural problem. In the near term, however, the greater cost of leasing compared to owning would be fairly modest—averaging about $34 million annually over the first five years. However, the cost differential would increase to over $200 million annually in later years.

Proposed Lease Terms

The long–term lease determines the income stream the new owners will receive from the buildings and therefore the price buyers are willing to pay. The lease terms are also essential in determining the costs of the sale–leaseback to the state over time. In the offering memorandum released to potential buyers on February 26, the Department of General Services (DGS) outlined the state’s preferred lease terms. The following are the main components of the proposed leases for ten of the buildings:

- Type of Lease. Under a modified gross lease, the owner would be responsible for paying most building services including building management, janitorial services, maintenance, special repairs, insurance, and scheduled upgrades. The owner would pay utilities with the exception of gas and electricity costs, which the state would pay. The DGS believes this is in the state’s best interests in order to take advantage of previous investments in energy efficiency. The state would also continue to provide security at those buildings with unique security needs.

- Lease Term. The initial lease would be for 20 years. After the initial term, the state would have the option to renew the lease under the same lease conditions for six additional terms of five years each—resulting in a total lease term of potentially 50 years.

- Rent Payments. Base rent payments would be set near current market rents for each property. The base rent would increase by 10 percent every five years.

- Operating Cost Escalator. On top of the base rent payments, the state would be responsible for paying annual changes in the owner’s operating expenses. The operating costs would be set at a fixed amount when the buildings are purchased and adjusted each year by the change in the Consumer Price Index.

- Property Tax Credit. As a government, the state does not currently pay property taxes on state buildings. The base rent included in the offering memorandum assumes that property taxes would be assessed on the properties. Under Board of Equalization rules, however, lease terms (including options) over 35 years are considered the equivalent of ownership, meaning that the state would still be considered the owner of the buildings for tax purposes. The state would be provided an annual credit against its rent equal to the amount of taxes not assessed on the basis that market rents reflect property tax costs.

- Right of First Refusal. If the owner receives an offer from a third party for the purchase of one or more of the properties, the state would have an opportunity to purchase the property under the same terms as the third–party offer.

- Upgrades. The owner would repaint all interior surfaces every five years and replace all floor coverings every ten years.

- Subleasing. The state may sublease any portion of the space.

These lease terms would apply to all of the properties with the exception of the California Emergency Management Agency Headquarters. Due to the building’s specialized purpose in responding to emergencies, DGS structured the proposed lease so that the state would maintain responsibility for all building services. |

The Governor’s 2010–11 budget proposal includes language allowing the Department of Finance to adjust budget amounts for rental costs associated with the sale–leaseback. Such adjustments would be necessary because appropriations scheduled to pay the debt service on the buildings, for example, would have to be redirected as lease payments to the new owners if the sale–leaseback transaction goes through. The Governor’s budget assumes this adjustment would require $20 million to account for higher lease costs. Similar to the revenue projections, the Governor’s rental cost projection of $20 million only assumed some of the buildings would sell in 2010–11. These costs would be higher if the state sold all of the properties in 2010–11 and leased them back at the market rents proposed in DGS’ lease terms.

Other Factors

In the previous sections, we focused exclusively on the financial factors that we believe provide the most important information for deciding how to proceed with the sale–leaseback. In researching the sale–leaseback, however, we encountered other issues, which we address below.

Transfer of Risk and Increased Cost Predictability. Leasing the facilities would result in more budget certainty through fairly predictable lease payments while avoiding the risk of unexpected and large costs associated with special capital repairs and renovations. In other words, the risk of unexpected costs would shift to the new owner. The lease payments would not be completely predictable because in addition to the base rent, the state would be responsible for paying increases in operating costs which would fluctuate according to inflation (as measured by the Consumer Price Index).

In addition to the cost predictability, leasing the facilities should guarantee that the buildings receive adequate maintenance and investment. During budget shortfalls, the state has tended to reduce expenditures for maintenance projects. Under the sale–leaseback, the ongoing lease payments would be fixed obligations.

Elimination of Debt. A successful sale would eliminate debt that the state owes on eight of the facilities. As shown in Figure 6, the state has approximately $1 billion in outstanding lease–revenue bonds remaining on the buildings proposed for sale. As described above, the state would use the sale proceeds to pay off the remaining principal debt and therefore would not have to pay most of the $467 million in interest costs (approximately $65 million of the interest would still be paid to bondholders as compensation for retiring the bonds earlier than scheduled).

Figure 6

Debt on Proposed Sale–Leaseback Properties as of July 1, 2010

(In Millions)

|

Building

|

Remaining Principal

|

Remaining Interest Payments

|

Total RemainingDebt Service

|

Debt Retirement Date

|

|

Capitol Area East End Complex

|

$381.1

|

$197.7

|

$578.8

|

2027–28

|

|

Franchise Tax Board Complex

|

231.7

|

139.6

|

371.3

|

2029–30

|

|

Earl Warren and Hiram Johnson Buildings (Civic Center)

|

201.5

|

66.0

|

267.5

|

2021–22

|

|

Elihu Harris Building

|

101.1

|

40.3

|

141.4

|

2022–23

|

|

Junipero Serra State Building

|

36.4

|

10.8

|

47.2

|

2019–20

|

|

Attorney General Building

|

37.2

|

9.5

|

46.7

|

2019–20

|

|

Public Utilities Commission Building

|

17.8

|

1.8

|

19.6

|

2013–14

|

|

Ronald Reagan State Building

|

17.0

|

1.0

|

18.0

|

2010–11

|

|

Totals

|

$1,023.8

|

$466.7

|

$1,490.5

|

|

While lowering the state’s debt is typically good policy, the benefit of eliminating the debt through a sale–leaseback transaction is illusionary. First, the avoided debt service would be immediately replaced with costlier rental payments to the new owners. Although the rental payments would not likely be considered debt in an accounting sense, they would still be an ongoing obligation of the state in future years.

Proponents have also suggested that eliminating the debt would improve the state’s credit position. The state currently has approximately $73 billion in outstanding general obligation and lease–revenue bonds plus an additional $58 billion in authorized, but unissued bonds. Eliminating the comparably small bond debt on these eight buildings—less than 2 percent of the state’s total debt—is unlikely to have a significant effect on the state’s debt ratios. Additionally, the state’s low credit rating is largely due to the state’s structural budget deficit, which one–time solutions such as the sale–leaseback do not address.

Loss of Building Control. One concern raised with the sale–leaseback is that the state would no longer have control over each building’s operation and condition. Assuming DGS and CBRE effectively incorporate minimum standards for the operation and condition of the buildings into the lease agreements, the state should be guaranteed a certain building standard even though it will no longer operate the buildings. Another concern was whether the state would maintain control over subleasing decisions. For example, daycare providers in the buildings were concerned that the new owners could raise their rents or evict them. Under the proposed lease terms, however, the state would lease the entire building and continue to have authority over which space is subleased and at what price. For example, the state could continue to subsidize rental rates for daycare providers.

Opportunities for More Subleasing. In promotional materials, DGS has highlighted the limited subleasing capacity in state–owned buildings. In order to maintain the tax–exempt status of the buildings’ financing, the amount of space that can be subleased to nonstate entities is limited. One purported benefit of the sale–leaseback is that under nonstate ownership, the state would have the added flexibility to sublease unneeded space to nonstate entities. In our view, the subleasing potential is minimal. Many of the buildings proposed for the sale–leaseback contain state government functions that are not likely to be eliminated or relocated so the availability of space for subleasing would be limited. In the event that downsizing did create some vacant space, the state would receive the same benefit by relocating other state agencies with shorter, less favorable leases into the sale–leaseback properties as it would from leasing the space to nonstate entities.

Estimating the Cost of Maintaining State Ownership Of the Office Buildings

There are four main costs of owning and operating the state’s office buildings: debt service, operations and maintenance, utilities, and special repairs. Only the debt–service payments are known with certainty. In forecasting the remaining costs, we attempted not to understate the potential costs and risk of the state continuing to own the buildings. Although not representing the worst–case scenario (we would not expect major failures in every building due to the diversity of the portfolio), we sought to provide significant allowances for major repairs and minor renovations. Our forecast starts with the Department of General Services’ (DGS’) estimated 2010–11 expenditures for operations and maintenance, utilities, and special repairs, and increases them each year by inflation. Then, in order to capture risk and potentially increasing costs as the buildings age, we did the following:

- We assumed additional capital reserves above DGS’ estimates. To meet the need for capital repairs and tenant improvements, DGS sets aside funds each year into capital reserve accounts for each building. We increased the set aside by 50 percent.

- We assessed additional costs to each building every five years that increase as the buildings age. These costs are meant to capture potential costs for system failures, capital upgrades, and minor renovations.

Our cost estimate does not include the potential costs of major renovations, and also does not acknowledge the residual value of the buildings and land at the end of the forecast period. We assume these values would tend to offset each other.

The state also receives a small amount of revenue by charging for parking at some buildings and leasing space to daycare providers and retail (for example, credit unions and coffee shops). We assume these revenues increase at the rate of inflation. |

Fiscal Analysis

If DGS finds a buyer and accepts an agreement on a sale–leaseback, the Legislature would have 30 days to review the transaction and determine if the state should enter into the agreement. As described above, the annual cost of owning the facilities would likely be much less than the cost of leasing the facilities over the long run. In evaluating the deal, the Legislature would need to consider whether the benefit of the one–time revenue from selling the facilities would be large enough to compensate for the higher costs in subsequent years.

As described above, we estimated the cost of maintaining state ownership of the office buildings and compared it to the cost of leasing the facilities under the terms proposed in the sale–leaseback. Over a 35–year period, we estimated the cost of leasing the facilities would be over $5 billion more than the cost of state ownership. As shown in Figure 7, these costs greatly exceed even the more optimistic estimate for sale revenue presented earlier. In present value terms (that is, adjusted for the principle that money available at the present time is worth more than money available in the future), the difference is considerably less. This is because the greatest costs are heavily discounted because they occur in the latter part of the 35–year period. Still, in present value terms, the leasing costs are greater than the one–time revenue. The sale–leaseback is projected to cost the state an additional $600 million to $1.5 billion.

A simple way to measure the cost in present value terms is to think of the sale–leaseback as a loan with interest—the state receives cash up front through the sale with the obligation to pay it back over time through lease payments. As shown in Figure 7, the state’s effective interest rate would be between 7.1 percent and 14.3 percent. These interest rates are greater than those the state is currently paying on the buildings’ outstanding lease–revenue bonds and greater than the effective interest rates on the state’s recently issued general obligation bonds.

Figure 7

Estimated Revenue and Cost of Sale–Leaseback Compared to Status Quo

(In Billions)

|

|

One–Time Revenue

|

Cost Differential Over 35 Years

|

Cumulative Net Present Value of Sale–Leaseback

|

Effective Interest Rate

|

|

Scenario

|

(Nominal)

|

(Net Present Value)a

|

|

Governor's budget sale price

|

$0.6

|

$5.5

|

$2.1

|

–$1.5

|

14.3%

|

|

More optimistic sale price

|

1.4

|

5.2

|

1.9

|

–0.6

|

7.1

|

Single Portfolio Versus Individual Sales. The above calculations combine the revenue and costs of the state’s entire portfolio of 11 buildings under the assumption that all of the buildings are sold. The bidders, however, are required to submit prices for each building and the legislation does not require DGS to sell every property. The DGS and the Legislature, therefore, could choose to analyze each building separately rather than as a single portfolio. Such an analysis could find that it is less costly to sell and lease back some buildings compared to others in the portfolio. For example, the state could receive a high bid on one building for which DGS currently has high operating costs and decide to sell that building while rejecting the remaining offers.

Results Sensitive to Various Factors. Our calculations were based upon a specific set of data and assumptions. If new information became available or the assumptions were changed, the analysis could be quite different. One of the larger uncertainties is estimating the cost of maintaining state ownership of the buildings due to the various risks and unknowns associated with building ownership. As described previously, we attempted to address this uncertainty by estimating these costs so as to not overstate the potential benefit of state ownership.

The number of years over which the sale–leaseback is analyzed is another parameter that effects the outcome of the analysis. For example, if the analysis only covered the initial lease term of 20 years, the sale–leaseback would appear more favorable because the growing costs in the later years would not be included. We chose 35 years for the evaluation period not only because it represents a reasonable useful life for the buildings in the portfolio but also because it is likely that the state would renew its leases on these buildings due to their role in providing government services, historic status, or proximity to other government buildings. For this reason, a shorter time frame would understate the cost of the leaseback in our view. For example, limiting the analysis to the initial 20–year term would not account for the significant costs in the following years of renewing the lease or leasing, buying, or building alternative space for these government functions.

Another factor open to different interpretations is the time value of money. Placing a larger emphasis on near–term revenues and costs, for instance, would make the sale–leaseback more attractive. The level to which the transaction’s future costs should be discounted depends upon an individual’s expectations about inflation, risk, and the value of future generations.

Recommendation

The above calculations provide some understanding of the true underlying cost of the sale–leaseback by showing how the lease payments impact the state’s budget beyond the budget year. The state originally invested in these buildings because it was determined that owning state office space would save money compared to leasing. Based on our analysis of the proposed sale–leaseback, this continues to be true as the cost of leasing back the buildings would exceed the sale revenue. As a result, we would normally not consider the sale–leaseback a reasonable budget solution since it would add to the structural deficit in order to address the current budget shortfall. Paying for the state’s annual costs of running its programs with a one–time sale of critical state assets is poor fiscal policy.

In the current budget environment, however, the sale–leaseback represents one imperfect option among many for balancing the budget. In deciding whether to endorse the sale–leaseback, the Legislature will need to consider how its costs compare to other alternatives for addressing the state’s budget shortfall, such as reducing expenditures and/or augmenting revenues. Given the array of difficult budget options before the Legislature, it would be difficult to specify how the sale–leaseback would compare. In general, however, we would encourage the Legislature to strongly consider other alternatives to the sale–leaseback. And, more specifically, we recommend the Legislature reject the sale–leaseback if the sales revenue is at the lower end of the range presented in this report—near the Governor’s revenue estimate, for example—as the effective interest rate would be too high and make other options preferable.

Next steps

If the bids do not match the administration’s expectations, DGS could decide to stop the sale–leaseback without seeking the Legislature’s input, similar to DGS’ actions for the sale of the Orange County Fairgrounds. If DGS decides to move forward with the sale, the department is required to provide details to the Legislature 30 days before completing the transaction. The 30–day reporting requirement was included to ensure the Legislature had an opportunity to examine the terms of the sale–leaseback and consider the matter again once all the information is available. With the bidding complete and terms agreed to, DGS will be able to provide the actual sale price and lease terms so that a more thorough analysis can be completed to show the actual benefits and costs of the sale–leaseback. The estimates in this report were based upon the lease terms proposed in the offering memorandum and assumptions about how buyers would react to the sale. With the actual numbers available, the Legislature can use this notification period to scrutinize the deal and stop the sale if it is unfavorable to the state.