(Note: On May 25, 2011, to complement

the economic and revenue forecasts contained in this report, we published

here the details of our multi-year expenditure forecast.)

The Governor’s May Revision

Administration Estimates $9.6 Billion Budget Problem Remains

A $26.6 Billion Projected Deficit. In January 2011, the administration estimated that the state would face a $25.4 billion deficit at the end of 2011–12. This large deficit was due in large part to the ending of many temporary budget solutions, including the expiration of temporary tax measures adopted two years ago. In March 2011, the administration announced that it would not pursue a planned sale of state buildings, resulting in additional lost revenue of $1.2 billion and the projected deficit increasing to $26.6 billion.

Legislature Has Passed $13.4 Billion in Budget Solutions. In March 2011, the Legislature passed and the Governor signed budget–related legislation that enacted $11 billion in General Fund solutions—cuts, fund shifts, and loans—over the 2010–11 and 2011–12 period. The Legislature also passed the 2011–12 Budget Bill that contained an additional $2.4 billion in expenditure reductions, but this has not been sent to the Governor for signature. Figure 1 shows the expenditure–related solutions that have been passed by the Legislature.

Figure 1

General Fund Benefit of Budget Actions Already Adopted

2010–11 and 2011–12 (In Billions)

|

Enacted Expenditure Reductions and Fund Shiftsa

|

|

|

Reduced Medi–Cal spending

|

$1.7

|

|

Reduced CalWORKs spending

|

1.0

|

|

Used Proposition 10 reserves to fund children’s programs

|

1.0

|

|

Reduced UC and CSU budgets

|

1.1

|

|

Funded transportation debt costs and loans primarily using weight fees

|

1.0

|

|

Shifted Proposition 63 funds to support community mental health services

|

0.9

|

|

Reduced spending on developmental centers

|

0.4

|

|

Reduced In–Home Supportive Services spending

|

0.4

|

|

Other expenditure reductions and fund shifts

|

0.6

|

|

Subtotal

|

($8.1)

|

|

Enacted revenue increases

|

$0.3

|

|

Enacted new loans, loan extensions and transfers from special funds, other solutions

|

2.6

|

|

Total, Enacted Budget Actions

|

$11.0

|

|

Enrolled Expenditure Reductions and Fund Shiftsb

|

|

|

Scored savings from efficiencies in state operations

|

$0.3

|

|

Suspended, deferred, or repealed state mandates

|

0.2

|

|

Reduced Receiver’s inmate medical care budget

|

0.2

|

|

Reduced court budget

|

0.2

|

|

Reduced other expenditures

|

1.0

|

|

Subtotal

|

($2.0)

|

|

Other Enrolled Budget Actions

|

|

|

Borrowed from Disability Insurance Fund for Unemployment Insurance interest payments

|

$0.3

|

|

Other actions

|

0.1

|

|

Subtotal

|

($0.4)

|

|

Total, Enrolled Budget Solutions

|

$2.4

|

|

Total, All Budget Actions

|

$13.4

|

Administration Forecasts Additional Revenue of $6.6 Billion. Since the administration produced its revenue estimates in January, its forecast of General Fund revenues in 2010–11 and 2011–12 combined has increased by $6.6 billion. This largely reflects the surprisingly strong PIT trends of recent months and assumes these continue into next year. (We discuss the revenue forecast in detail later in this publication.)

Additional Costs of $3 Billion Since March. The administration has identified an additional $3 billion in General Fund costs since the Legislature passed the budget actions in March 2011. These include additional costs in the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation ($0.4 billion), a net increase in Proposition 98 costs over the 2009–10 through 2011–12 period ($1.6 billion), and the administration’s decision not to include the General Fund savings from using Proposition 10 funds for children’s health programs. (The administration has stated its intent to defend the use of these funds in the legal challenges brought against the state but has decided not to score the savings due to its assessment of the legal risks.)

Estimate of Required Actions Includes a $1.2 Billion Reserve. Figure 2 shows the administration’s estimate of the actions still needed to balance the 2011–12 General Fund budget. In total, the Governor’s plan projects the need for an additional $9.6 billion of budget actions. The Governor also proposes a $1.2 billion reserve at the end of 2011–12, resulting in the administration’s call for $10.8 billion of additional actions. As we will discuss later in this document, the size of the required solutions is based, in part, on the administration’s assumptions regarding the funding of K–14 education under the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee.

Figure 2

Remaining Solutions Needed to Address the Deficit

2010–11 and 2011–12 Combined (In Billions)

|

|

|

|

Estimated June 30, 2012 deficit—January 2011

|

$25.4

|

|

Loss of sale–leaseback revenue

|

1.2

|

|

Deficit—May 2011

|

$26.6

|

|

Enacted solutions

|

$11.0

|

|

Enrolled solutions

|

2.4

|

|

Additional current–law revenues

|

6.6

|

|

Higher state costs (net)

|

–1.4a

|

|

Higher Proposition 98 workload costs

|

–1.6

|

|

Solutions Already Achieved

|

$17.0

|

|

Additional Solutions to Close the Deficit

|

$9.6

|

|

Governor’s reserve

|

1.2

|

|

Governor’s Estimate of Solutions Needed

|

$10.8

|

Major Proposals in the May Revision

Figure 3 lists the Governor’s May Revision proposals addressing the remaining problem. In total, the Governor proposes $11.2 billion in new revenues and $2.2 billion in additional expenditure reductions, both of which are partially offset by additional expenditures for Proposition 98 and paying off special fund borrowing. The Governor continues with the plan to end redevelopment agencies and use some portion of their funding to support Medi–Cal programs and the courts. Overall, the Governor uses the revenue growth described above to (1) scale back some of the new revenue proposals, (2) increase education funding, and (3) reduce some budgetary borrowing.

Figure 3

May Revision Proposals to Close Remaining Gap

(In Billions)

|

|

Impact on Reserve

|

|

Revenue Solutions

|

|

|

General Fund Revenue Solutions

|

|

|

Adopt 0.25 percentage point personal income tax surcharge for four more years

|

$1.3

|

|

Adopt reduction in dependent exemption credit for five more years

|

2.2

|

|

Adopt 0.1 percentage point vehicle license fee (VLF) increase for five more years

|

0.3

|

|

Make single sales factor mandatory for multistate firms

|

1.4

|

|

Adopt other revenue measures

|

0.4a

|

|

Subtotal

|

($5.6)

|

|

Local Realignment Revenue Solutions

|

|

|

Adopt 0.5 percentage point VLF increase for five more years (0.4 percent goes to realignment)

|

$1.1

|

|

Adopt 1 percentage point state sales tax increase for five more years

|

4.5

|

|

Subtotal

|

($5.6)

|

|

Total

|

($11.2)

|

|

Expenditure–Related Solutions

|

|

|

End redevelopment and shift funds to Medi–Cal and trial courts

|

$1.7

|

|

Achieve additional state savings from realignment

|

0.2

|

|

Achieve additional health spending reductions

|

0.2

|

|

Achieve additional employee compensation savings

|

0.1

|

|

Achieve other savings

|

0.1

|

|

Total

|

($2.2)

|

|

Additional Expenditures

|

|

|

Increase Proposition 98 guaranteeb

|

–$1.9

|

|

Cancel new loans, loan extensions, and repay other special fund loans early

|

–0.7

|

|

Total

|

(–$2.6)

|

|

Total, All Solutions

|

$10.8

|

Same Basic Framework for Revenue Proposals. The basic framework of the Governor’s revenue proposals—the adoption for several more years of higher PIT, sales and use tax (SUT), and vehicle license fees (VLF) first passed in 2009—is largely unchanged from January. These rates would remain in effect for five years (although the PIT rates would be in effect for only four years). The Governor also maintains his proposal to require multistate companies to apportion profits using the “single sales factor” method. The Governor, however, has dropped his proposal to eliminate enterprise zones and has replaced this proposal with a more modest reform of the program. Overall, the total additional revenue in the May Revision is $11.2 billion, compared with $14 billion in the January budget proposal.

Governor’s Realignment Proposal Also Largely Unchanged. In January, the Governor proposed to shift responsibility for some program delivery from the state to local entities (primarily in some criminal justice, mental health, and human services programs). In the May Revision proposal, the Governor makes some adjustments to the programs shifted to local entities. The Governor continues to propose that the programs shifted to local responsibility be funded through the temporary increases in sales taxes and VLF. However, as the estimated cost of the realigned programs is now less than the projected revenues from these taxes, the Governor proposes that only a portion of the VLF be used to fund programs at the local level, with the remainder being available for General Fund purposes.

Governor Still Seeking Voter Approval for Elements of the Budget Plan. As in January, the Governor is still proposing that two key elements of the budget proposal—his major tax proposals and the shift of some state programs to local entities—be approved by voters. At this stage, the administration has not published a timetable for this election or how these two elements of his plan would be implemented prior to the election.

New Proposals to Restructure Elements of State Government. The May Revision includes new proposals to change, eliminate, or reorganize some elements of state government (see Figure 4). The administration also proposes to shift all children in the Health Families Program into Medi–Cal health coverage.

Figure 4

Reorganizations and Eliminations of State Functions in the Governor’s May Revision

Estimated Savings (In Millions)

|

|

2011–12

|

|

General Fund

|

Other Funds

|

Totals

|

|

Changes Due to Realignmenta

|

|

|

|

|

Eliminate the Department of Mental Health and the Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Create a Department of State Hospitals

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Eliminations and Consolidations

|

|

|

|

|

Eliminate the Early Learning Advisory Council

|

—

|

$3.6

|

$3.6

|

|

Eliminate the California Anti–Terrorism Information Center

|

$3.2

|

—

|

3.2

|

|

Eliminate the California Postsecondary Education Commission

|

0.9

|

0.2

|

1.1

|

|

Eliminate the Colorado River Board

|

—

|

0.8

|

0.8

|

|

Accelerate end of American Recovery and Reinvestment Act Task Force

|

0.4

|

0.4

|

0.8

|

|

Consolidate the State Personnel Board and the Department of Personnel Administration

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Adopt other eliminations

|

1.9

|

1.1

|

3.0

|

|

Subtotals

|

($6.4)

|

($6.1)

|

($12.5)

|

|

Program Efficiencies and Reductions

|

|

|

|

|

Reduce workload in the Office of the Inspector General

|

$6.4

|

—

|

$6.4

|

|

Achieve Department of Parks and Recreation technology savings

|

4.5

|

—

|

4.5

|

|

Eliminate the Human Resources Modernization Project

|

2.3

|

$3.2

|

5.5

|

|

Adopt other efficiencies and reductions

|

5.5

|

1.7

|

7.2

|

|

Subtotals

|

($18.7)

|

($4.9)

|

($23.6)

|

|

Totalsb

|

$25.1

|

$11.0

|

$36.1

|

Commitment to Pay Off Budgetary Debt. As part of the May Revision, the administration stated its intent to work towards the repayment of “budgetary debt.” Over time, the administration estimates, the state has incurred around $34 billion of debt associated with temporary fixes to General Fund deficits such as deferring a portion of annual payments to schools or borrowing from special funds. Some of this debt, such as the economic recovery bonds (voter–approved borrowing that was used to fund the state deficit incurred early in the last decade), has a dedicated funding source. Others, such as special fund loans, have a repayment schedule set in statute. In 2011–12, the Governor proposes to repay $744 million of special fund loans early (bringing forward repayment from 2012–13) as well as reversing an earlier budget decision to defer additional payments to schools. In future years, the Governor proposes to further reduce budgetary debt beyond what would happen automatically or through existing statute—principally, it appears, by ending interyear deferrals of scheduled payments to schools.

The Economy and Revenues

Economic Outlook

U.S. Economy

Economy Has Been Picking Up Steam Lately. The national recession that began in December 2007—the longest since World War II and the most severe since the Great Depression—ended in June 2009. The subsequent modest recovery clearly has picked up steam in recent months, aided substantially by continuing fiscal and monetary economic stimulus actions of the federal government. Nonfarm payroll employment has increased by an average of 233,000 per month over the last three months compared with an average of 104,000 per month over the entirety of the past year. While government payrolls have shrunk—the casualty of widespread state and local fiscal difficulties—gains in private payrolls have been broad–based. Economic activity in the manufacturing sector, which has been battered in many recent years, has expanded for 21 consecutive months through April. Core inflation—which excludes the sometimes volatile components of food and energy—has remained low. Business profits have grown, helping to improve prospects for the labor market.

Job Market Is Better…But Still a Long Way to Go. The national unemployment rate has dropped from 9.8 percent in November 2010 to 9.0 percent in April 2011—an indication of some economic progress but also that much slack remains in labor markets. Seasonally adjusted nonfarm employment, which peaked at 138 million in January 2008 and fell to 129 million through February 2010, has now risen to 131 million. By historical standards, this remains a tepid recovery, as the national economy continues to mend and readjust after the severe shocks resulting from the near–collapse of the housing and credit markets.

2011 Economic Performance Affected by Federal Tax Measures. Figure 5 compares several key national and California economic variables for 2011 and 2012 in our office’s February 2011 economic forecast, the administration’s May Revision forecast, and our new May 2011 forecast. Compared to our forecast in February, our updated forecast shows national economic performance up by some measures and down by other measures during that period. The projected rate of personal income growth appears to slow in 2012, but this is because of the temporary one–time boost in 2011 resulting from a one–year federal payroll tax holiday. Were it not for this one–time effect, 2012 likely would show a slightly higher personal income growth rate than 2011.

Our updated multiyear national economic forecast—shown in Figure 6 (see page 11)—assumes steady, moderate growth through 2016.

Figure 5

Forecasts for Some Economic Indicators Have Improved

(Percent Change Unless Otherwise Indicated)

|

|

2011

|

|

2012

|

|

LAO Forecast (Feb. 2011)

|

Administration Forecast

((May 2011)

|

LAO Forecast (May 2011)

|

LAO Forecast (Feb. 2011)

|

Administration Forecast

((May 2011)

|

LAO Forecast (May 2011)

|

|

United States

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Real Gross Domestic Product

|

3.2%

|

2.8%

|

2.8%

|

|

2.9%

|

2.9%

|

3.1%

|

|

Personal Income

|

4.9

|

5.2

|

5.3

|

|

3.2

|

3.7

|

3.6

|

|

Wage and Salary Employment

|

1.4

|

1.2

|

1.2

|

|

2.1

|

1.8

|

1.9

|

|

California

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Personal Incomea

|

5.0

|

4.4

|

5.4

|

|

3.3

|

4.5

|

3.8

|

|

Wage and Salary Employment

|

1.1

|

1.3

|

1.6

|

|

1.9

|

1.9

|

2.0

|

|

Housing Permits (thousands)

|

53

|

55

|

54

|

|

79

|

87

|

81

|

Figure 6

The LAO’s Economic Forecast

(May 2011)

|

|

2009

|

2010

|

2011

|

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

2016

|

|

United States

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Percent change in:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Real Gross Domestic Product

|

–2.6%

|

2.9%

|

2.8%

|

3.1%

|

2.9%

|

2.9%

|

2.9%

|

2.7%

|

|

Personal Income

|

–1.7

|

3.1

|

5.3

|

3.6

|

4.4

|

5.6

|

5.2

|

5.5

|

|

Wage and Salary Employment

|

–4.4

|

–0.7

|

1.2

|

1.9

|

2.0

|

1.8

|

1.6

|

1.3

|

|

Consumer Price Index

|

–0.3

|

1.6

|

2.6

|

1.5

|

2.0

|

2.3

|

2.2

|

2.1

|

|

Unemployment Rate (percent)

|

9.3

|

9.6

|

8.7

|

8.2

|

7.6

|

7.1

|

6.6

|

6.3

|

|

Housing Permits (thousands)

|

554

|

585

|

640

|

1,065

|

1,480

|

1,621

|

1,732

|

1,732

|

|

California

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Percent change in:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Personal Income

|

–2.3%

|

2.5%

|

5.4%

|

3.8%

|

5.1%

|

5.7%

|

5.6%

|

5.7%

|

|

Wage and Salary Employment

|

–6.0

|

–1.4

|

1.6

|

2.0

|

2.5

|

2.3

|

2.1

|

1.7

|

|

Unemployment Rate (percent)

|

11.4

|

12.4

|

12.0

|

11.1

|

9.6

|

8.4

|

7.5

|

6.8

|

|

Housing Permits (thousands)

|

36

|

45

|

54

|

81

|

101

|

117

|

127

|

133

|

Uncertainties in the Forecast. Like all economic forecasts, ours is subject to uncertainty, both on the upside and the downside. There is certainly a possibility that economic performance could improve above expectations—more closely mirroring the more robust growth trends of past economic recoveries. On the other hand, there are also a number of risks embedded in our forecast, including the following:

- Oil Prices. Our office’s economic forecast reflects an expectation that recent spikes in fuel prices will be a temporary phenomenon due to the recent upheaval in the Middle East. If prices remain high, however, near–term economic performance could be weakened.

- Federal Debt Limit Debate. Our forecast also assumes no economic disruption due to a failure of Congress and the President to approve increases in the federal “debt limit,” which is key to allowing the United States to continue making its debt payments to investors around the world. Should there be substantial disruptions in credit markets from the failure to resolve the debt limit issue, severe economic consequences may result. For California, such disruptions in credit markets could hamper the state’s ability to borrow this fall for cash flow purposes.

- Japan’s Recovery. Our forecast assumes little or no net economic effect resulting from Japan’s efforts to rebuild after its recent earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster. Japan is a leading trade partner, and adverse developments in its recovery could affect both the United States and California.

- Housing Prices. The housing market remains fragile, with the most recent California data from February suggesting that prices continued to fall slowly in San Diego, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. Further drops in national and California housing prices are expected to be small, but housing markets are volatile and if the drop is bigger than expected, various elements of our economic and revenue forecasts could be affected adversely, including building permits, employment growth, and capital gains.

California Economy

Economic Outlook for State Has Improved Somewhat in Recent Months. Figure 5 shows that our near–term economic outlook for California has improved somewhat since February. As measured by both personal income and employment growth, California now appears poised to have a somewhat faster pace of growth than the nation as a whole in 2011 and 2012. This is understandable given the degree to which California suffered more severely than the nation as a whole during the recent recession. Like the nation, economic prospects are favorable in much of California’s private–sector economy, except, notably, for the construction industry. Nevertheless, like the nation as a whole, California continues to have substantial slack in its labor markets. We project that the state’s unemployment rate will remain above 10 percent until early 2013. The number of Californians unemployed for more than six months—currently over 1 million—could remain very high for some time.

Housing and Construction Remain Substantial Economic Drags. Housing permits—a key indicator of construction activity—numbered about 45,000 in 2010 in California, nearly 80 percent below their pre–recession peak level. While our forecast suggests the number of permits will grow at a fairly good pace (measured in percentage growth terms) throughout the forecast period, there are no prospects for housing permits to return to their pre–recession level. Housing prices are poised to remain far below their prior peak levels for the foreseeable future. This drag on the state’s economy is one reason why annual personal income growth and employment growth should continue to lag those of some past economic recoveries. If there is one brighter spot in the housing market, it is the multi–unit sector, as apartment vacancy rates have dropped and permits have already picked up somewhat.

Revenues

Administration Forecast

Over $6 Billion Higher Revenue Estimate Driven by Strong Recent Collection Trends. The administration updates its revenue estimates when it prepares the May Revision. The revision shows that revenues under the policies described in the 2011–12 Governor’s Budget from January are estimated to be $6.3 billion higher now—$2.8 billion in 2010–11 and $3.5 billion in 2011–12.

The vast majority of this projected revenue increase is in personal income taxes (PIT). Both PIT withholding and estimated payments have been running very strong. Withholding—a key indicator of current wage and payroll growth in the economy—has been 5.4 percent above prior–year levels since January, despite lower withholding rates due to the expiration at the end of December of higher PIT rates adopted with the February 2009 budget package. Estimated payments in April—a key indicator of capital gains and certain business activity in the economy—were up by 24 percent over collections in the same month of the prior year. Both the Department of Finance (DOF) and our office have had difficulty reconciling these robust revenue trends with official economic data related to wages and other categories of personal income. Nevertheless, consistent with the collection trends, the May Revision increases the administration’s January PIT baseline forecast by $3.7 billion in 2010–11 and $4.4 billion in 2011–12.

Offsetting the strength in PIT collections has been weakness in corporation tax (CT) receipts compared to the administration’s January projections. Between January and April, CT collections sagged by $654 million below the administration’s estimates. Accordingly, the May Revision lowers the 2010–11 CT baseline forecast by $1 billion and the 2011–12 forecast by $701 million.

In addition to the $6.3 billion increase in major revenues shown in the May Revision summary, the administration also notes that accruals and other revenue estimating adjustments add $300 million in revenue for the 2011–12 budget process. Accordingly, the administration estimates that the total amount of increased baseline revenues is $6.6 billion.

Budget Problem Definition Also Reflects Expansion of Administration’s Accrual Policy. As we described in our January 31, 2011 publication, The Administration’s Revenue Accrual Approach, the administration incorporated a new, complex approach for accruing (attributing) revenues to fiscal years in its January budget package. With the May Revision, the administration expands this new approach to apply not just to the Governor’s new tax proposals, but to total personal and corporate income tax revenues. This expansion of the administration’s January accrual approach results in a $2.5 billion decrease in the state’s 2009–10 ending General Fund balance—in essence, removing revenues from prior years’ books and moving them to either 2010–11 or 2011–12. Correspondingly, the accrual change increases PIT and CT revenues by $900 million in 2010–11 and $1.4 billion in 2011–12. Incorporating both the fund balance adjustment and these changes in 2010–11 and 2011–12 revenues, the overall net effect of the accrual change is a reduction in resources available for the 2011–12 budget process of $170 million.

May Revision Proposals

Same Basic Framework for Both January and May Revenue Proposals. The Governor’s May Revision revenue proposals maintain the same basic framework as those in his January budget proposal. Temporary increases in SUT, VLF, and PIT originally adopted in February 2009 generally would be adopted for five more years. In addition, the Governor proposes to require multistate companies to apportion profits to California using the single sales factor method.

Governor Changes Some of His Tax Proposals. In the May Revision, the Governor changes his January revenue proposals—reducing the size of some tax proposals and proposing new tax expenditures (credit and exemption programs). Specifically, his May proposal reflects the following changes, compared to his January proposal:

- Eliminates PIT Surcharge for 2011. The Governor has modified his January proposal to apply the temporary 0.25 percentage point PIT surcharge to tax years 2012 through 2015—therefore omitting the 2011 surcharge included in his January proposal. In January, the 2011 surcharge had been estimated to result in $725 million of accrued General Fund revenues for 2010–11.

- Modifies, Rather Than Eliminates, Enterprise Zones. The Governor’s January budget proposal included $924 million of General Fund revenue over two years ($343 million accrued to 2010–11 and $581 million in 2011–12) based on the elimination of the state’s enterprise zones. This program seeks to stimulate economic investment and hiring in economically depressed areas. In the May Revision, the Governor abandons his enterprise zone elimination proposal, offering instead modifications to the current program. Specifically, the Governor proposes to reduce the value to employers of the hiring credit portion of the enterprise zone program. Under his proposal, a business would be eligible for a one–time $5,000 credit—claimed on an original return—for each new full–time equivalent employee they hire. This is far less than is generally available now. In addition, the administration proposes that no new credit vouchers be granted for tax years prior to 2011 if an application was made more than 30 days after the hire’s start date. Finally, enterprise zone hiring credits, including those issued in the past, would expire if not used within five years after being issued. The new proposal is estimated to increase General Fund revenues by $23 million in 2010–11, $70 million in 2011–12, and more thereafter.

- Adopts Partial Manufacturing Investment Sales Tax Exemption. The Governor proposes a four–year partial exemption from General Fund SUT for purchases of tangible property used in manufacturing. This exemption would begin in 2012–13. In general, manufacturers would be eligible for an exemption on paying 1 percentage point of the SUT, but start–up firms would be eligible for a full exemption from the 5 percentage point General Fund SUT rate. The Governor’s proposal would result in a General Fund revenue decrease estimated at $261 million in 2012–13, increasing slightly thereafter through 2015–16.

- Changes Existing State New Jobs Credit. In 2009, the state adopted a new hiring credit for certain small businesses. A total of $400 million was allocated to the credit, but it has not been claimed to the extent expected. As a result, the administration estimates that funds would be available for five more years. With the May Revision, the Governor proposes to increase the hiring credit from $3,000 to $4,000 per new employee, offer the credit to employers with less than 50 employees (as opposed to less than 20 employees under current law), and sunset the credit at the end of 2012. In addition, the administration proposes funding a public awareness effort for the credit. The administration estimates these changes would decrease General Fund revenues by $29 million in 2010–11, $65 million in 2011–12, and $31 million in 2012–13 and then increase revenues by a few million dollars each year thereafter through 2016–17.

While the Governor’s VLF proposal is unchanged, lower costs of realigned programs in his budget package allow him to dedicate 0.1 percentage points of his proposed 0.5 percentage point extension in VLF rates (generating about $270 million of estimated revenue in 2011–12) to the General Fund—instead of local realignment funds—for the next five fiscal years. All told, including various estimating changes, the administration projects the value of its tax proposals to be $11.2 billion (of which $5.2 billion is proposed for the General Fund) versus about $14 billion (about $8 billion General Fund) in January.

LAO Forecast

Based on our office’s updated national and California economic estimates, we develop our own independent estimate of the near–term and out–year effects of both economic conditions and the Governor’s proposed tax policies on General Fund revenues. The results of our preliminary forecast of General Fund revenues under the Governor’s May Revision policies are summarized in Figure 7 and described below.

Figure 7

LAO Preliminary Revenue Forecast—Reflecting Governor’s May 2011 Proposals

General Fund (In Millions)

|

|

2009–10 Actual

|

2010–11 Projected

|

2011–12 Projected

|

2012–13 Projected

|

2013–14 Projected

|

2014–15 Projected

|

2015–16 Projected

|

|

Personal income tax

|

$44,852

|

$51,869

|

$54,191

|

$56,643

|

$58,236

|

$63,051

|

$64,871

|

|

Sales and use tax

|

26,741

|

26,770

|

24,440

|

26,226

|

28,077

|

29,429

|

30,572

|

|

Corporation tax

|

9,115

|

9,422

|

9,944

|

10,240

|

10,870

|

11,673

|

12,265

|

|

Subtotals, “Big Three” General Fund taxes

|

($80,708)

|

($88,061)

|

($88,575)

|

($93,109)

|

($97,183)

|

($104,153)

|

($107,708)

|

|

Insurance tax

|

$2,002

|

$2,009

|

$1,818

|

$1,960

|

$2,189

|

$2,278

|

$2,369

|

|

Estate taxa

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

830

|

1,750

|

1,850

|

1,940

|

|

Other revenuesb

|

3,860

|

3,735

|

2,936

|

2,880

|

2,570

|

2,697

|

2,820

|

|

Net transfers and loans

|

476

|

1,897

|

391

|

–292

|

–1,114

|

–962

|

–500

|

|

Totals, General Fund Revenues and Transfers

|

$87,046

|

$95,702

|

$93,720

|

$98,487

|

$102,578

|

$110,016

|

$114,337

|

Overall Revenue Estimates Almost Identical to Administration’s in 2010–11 and 2011–12. Figure 7 shows that, under the Governor’s May Revision policies, we estimate that 2010–11 General Fund revenues and transfers would be $95.7 billion and 2011–12 revenues and transfers would be $93.7 billion. These numbers are virtually identical to the administration’s, as shown in Figure 8. Over the two fiscal years combined, our forecast of General Fund revenues is $59 million higher than the administration’s. In the out–years, as described more below, our forecasts are $2 billion or more lower than the administration’s estimates in each year.

Figure 8

LAO Forecast Same as Administration’s Now . . . Lower in the Future

LAO Preliminary Forecast Minus Administration Forecast (In Millions)

|

|

2010–11 Projected

|

2011–12 Projected

|

2012–13 Projected

|

2013–14 Projected

|

2014–15 Projected

|

|

Personal income tax

|

–$76

|

–$138

|

–$2,103

|

–$950

|

–$1,899

|

|

Sales and use tax

|

30

|

525

|

229

|

10

|

–286

|

|

Corporation tax

|

14

|

–216

|

–232

|

–1,086

|

–1,170

|

|

Other revenues and transfers

|

–6

|

–74

|

–80

|

–18

|

10

|

|

Differencesa

|

–$38

|

$97

|

–$2,186

|

–$2,044

|

–$3,345

|

Some Significant Differences With Administration on Methodology. While our overall General Fund revenue totals for 2010–11 and 2011–12 are similar to the administration’s, there are some significant differences underlying our respective forecasts which are important to understand because they contribute to significant differences in our respective out–year revenue forecasts.

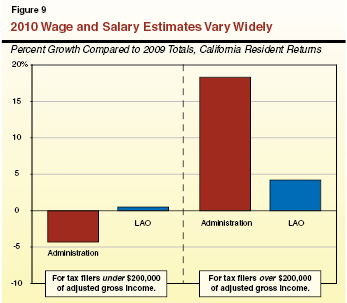

Different Assumptions About 2010 Salaries and Wages. Both our office and the DOF have had difficulty reconciling the very strong PIT results this spring with the official economic data. In short, revenues are coming in much higher than the official labor and other economic data seem to suggest. Administration officials informed us that their working theory about the higher PIT totals centered on an assumption that wage and salary growth for high–income Californians grew substantially in 2010. As shown in Figure 9, the administration assumed that tax filers with over $200,000 of adjusted gross income (AGI) collectively saw their wages and salaries grow by 18.3 percent in 2010. By contrast, the administration assumed that tax filers with under $200,000 of AGI saw their wages and salaries decrease by 4.3 percent that year.

While we agree that the data suggest that upper–income Californians experienced higher wage growth in 2010, we see nothing in available economic and tax collection data to support the very large growth number the administration assumes for upper–income residents and the negative growth number assumed for lower–income residents. As shown in Figure 9, our forecast assumes that tax filers with over $200,000 of AGI saw their salaries and wages grow by 4.2 percent in 2010, versus 0.5 percent growth for tax filers with less AGI.

Data to determine which estimate is more accurate will become available gradually over the next two years, and have major implications for out–year PIT collections. Because the administration builds such strong 2010 growth for upper–income Californians—those paying taxes at the highest marginal tax rates—into their wage forecasts and then grows salaries and wages for this group each year thereafter, its forecasts for PIT are systematically higher than ours for the rest of the forecast period. This difference explains a portion of the $1 billion to $2 billion difference between our PIT forecast and the administration’s beginning in 2012–13.

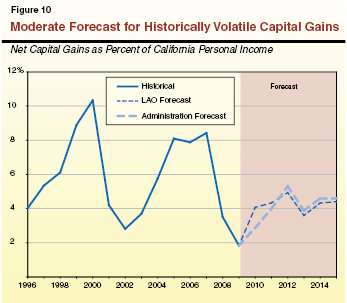

Different Assumptions About 2010 Capital Gains. Our working theory about the higher 2010 tax collections centers on capital gains—typically, a much more volatile revenue source than income taxes generated by salaries and wages. As shown in Figure 10, we are assuming in our PIT forecast that net capital gains grew from about $29 billion in 2009 (a very low level due to the 2008 and 2009 financial market turmoil) to $65 billion in 2010, a level that is equal to about 4 percent of California personal income. By contrast, the administration assumes only $46 billion of net capital gains in 2010. Similarly, we assume higher capital gains than the administration in 2011 based on these trends and recently favorable stock market performance. These higher capital gains assumptions are a key reason why our forecast ends up being so similar to the administration’s in 2010–11 and 2011–12—offsetting our lower assumption for salary and wage growth in 2010 for higher–income residents. Nevertheless, in our forecast model, capital gains generally remain flat after 2011, with some variation based on the assumed acceleration of capital gains to tax year 2012 due to the scheduled expiration of federal tax cuts in 2013. Accordingly, while the higher capital gains help keep us even with the DOF’s forecast in the near term, they do not provide a similar boost in the out–years.

It should be noted that capital gains are virtually impossible to forecast over a multiyear period. Data to determine which forecast is more accurate in the out–years will not emerge until well after PIT collections pour in during April in each year of the forecast.

Lower Dependent Credit Revenue Assumption. In addition to the differences described above concerning salaries and wages and capital gains, other differences with the administration also are embedded in our PIT forecasting model. For example, our estimate of the revenue gain from the proposed reduction of the dependent exemption credit is $145 million lower in 2010–11 and 2011–12 combined and $100 million to $200 million lower in each fiscal year thereafter.

Higher SUT Forecast in 2011–12 and 2012–13. Our forecast assumes $525 million more of SUT collections for the General Fund in 2011–12 and $229 million more in 2012–13. Consumer confidence clearly is returning, as retail (same–store) sales trends have experienced months of increases, including impressive increases in April. In recent months, the car sales market—an important component of the SUT base in California—also has improved, with notable increases by domestic U.S. automakers. Federal tax policy stimulus—lower payroll taxes in 2011, as well as two–year extensions of other federal tax reductions—also are stimulating consumer demand. While our forecast is higher than the administration’s in the near term, our forecast models indicate a somewhat slower rate of taxable sales growth in the out–years.

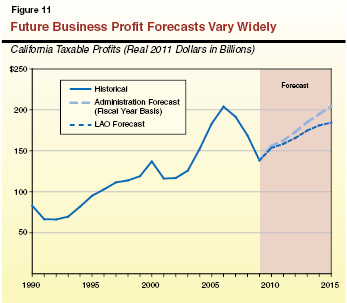

Lower CT Forecast in the Out–Years. Our February 2011 CT forecast was considerably lower than the administration’s. In the May Revision, the administration has lowered its forecast substantially. Our updated forecast is virtually identical to the administration’s new projections in 2010–11 and about $200 million less in both 2011–12 and 2012–13. In the out–years the administration assumes growth of California taxable business profits that resembles the boom of the early 2000s (see Figure 11). In contrast, we expect corporate profits to grow more slowly beginning in about 2013. This difference in corporate profits largely explains our lower CT forecasts beginning in 2013–14.

Reasonable Revenue Estimates for the 2011–12 Budget Process. As described above, our revenue estimates end up virtually identical to the administration’s for 2010–11 and 2011–12, despite some differences in methodology. Accordingly, we conclude that the overall revenue numbers in the Governor’s revised budget plan are reasonable. Revenue prospects clearly have improved substantially since January based on robust PIT collections trends.

Proposition 98—K–14 Education

Governor’s May Revision Proposal

Figure 12 shows the Governor’s May Revision Proposition 98 funding levels for K–12 education and the California Community Colleges (CCC). Relative to the budget approved by the Legislature in March, the May Revision contains only minor funding increases in the current year but a $3 billion increase in the budget year.

Figure 12

Governor’s Proposition 98 Funding Proposal

(In Millions)

|

|

2010–11

|

|

2011–12

|

|

|

Conference

|

May Revision

|

Change

|

|

Conference

|

May Revision

|

Change

|

|

K–12 Education

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$32,239

|

$31,722

|

–$517

|

|

$32,494

|

$34,430

|

$1,936

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

11,557

|

12,147

|

589

|

|

11,406

|

12,123

|

717

|

|

Subtotals

|

($43,796)

|

($43,868)

|

($72)

|

|

($43,900)

|

($46,553)

|

($2,653)

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$3,885

|

$3,885

|

—

|

|

$3,542

|

$3,807

|

$265

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

1,892

|

1,949

|

$57

|

|

1,873

|

1,949

|

75

|

|

Subtotals

|

($5,777)

|

($5,834)

|

($57)

|

|

($5,415)

|

($5,756)

|

($340)

|

|

Other Agencies

|

$85

|

$85

|

—

|

|

$87

|

$85

|

–$2

|

|

Totals, Proposition 98

|

$49,658

|

$49,787

|

$129

|

|

$49,402

|

$52,394

|

$2,992

|

|

General Fund

|

$36,209

|

$35,691

|

–$517

|

|

$36,123

|

$38,322

|

$2,199

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

13,449

|

14,096

|

646

|

|

13,279

|

14,072

|

793

|

2010–11 Funding Up Slightly. For 2010–11, the Governor’s May Revision continues to assume the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee is suspended. The May Revision, however, includes an increase of $129 million in Proposition 98 funding to recognize higher–than–expected K–12 costs ($72 million) and higher–than–expected community college property tax revenues ($57 million). Despite the small increase in total Proposition 98 funding, General Fund costs are notably reduced ($517 million). This is because higher–than–expected K–12 local property tax revenues ($646 million) reduce the General Fund share of revenue limit costs. (For CCC, higher–than–expected local property taxes do not result in an automatic reduction in state General Fund spending. The additional revenues instead provide an increase to community college apportionments.)

2011–12 Funding Up $3 Billion. The Governor continues to fund at the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee in 2011–12. Due to a number of factors, however, the minimum guarantee is $3 billion above the March level. Figure 13 shows the changes from the March to the May estimates of the minimum guarantee. As the figure shows, the minimum guarantee increases by $2 billion due to improvements in the state’s baseline General Fund revenues and changes in the way the state accrues certain General Fund revenues. These increases are offset slightly by the Governor’s revised tax proposals, which reduce the minimum guarantee by $375 million. The guarantee also increases by $793 million due to higher estimates of local property tax revenues in the budget year. Finally, the Governor makes various adjustments so that the minimum guarantee is “held harmless” for specific changes in tax policy and shifts in programmatic responsibilities. These adjustments—commonly called rebenching—increase the minimum guarantee by a net of $656 million. (Rebenching is discussed in more detail in the box below.)

Figure 13

Summary of Changes in 2011–12

Proposition 98 Minimum Guarantee

(In Millions)

|

|

|

|

General Fund Adjustments:

|

|

|

Baseline General Fund increase

|

$1,451

|

|

Accrual/policy changes

|

573

|

|

Tax proposal changes

|

–375

|

|

Other minor revenue changes

|

–106

|

|

Subtotal—Revenues

|

($1,543)

|

|

Property Tax Increase

|

$793a

|

|

Rebenching:

|

|

|

Gas tax shift

|

$630

|

|

AB 3632 mental health shift

|

222

|

|

Change in value of existing LPT shifts/other

|

–196

|

|

Subtotal—Rebenching

|

($656)

|

|

Total Changes

|

$2,992

|

Rebenching Raises Many Dicey Issues

The May Revision contains two rebenching proposals that result in increases in the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. Specifically, the administration proposes to rebench for: (1) the recent policy change that eliminated the sales tax on gasoline and increased the excise tax and (2) the proposed shift of responsibility for student mental health services from county mental health departments to school districts. As discussed in more detail below, rebenching raises serious legal, policy, and implementation issues.

Constitution Makes No Provision for Rebenching. The California Constitution is silent on whether the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee can be adjusted to account for policy changes. Over time, the state has adopted various statutory provisions relating to rebenching, but these provisions tend either to implement only one specific shift or are so general as to raise questions of legal interpretation. In the case of program shifts, statute also addresses only shifts to not away from schools. That is, if implemented, rebenching for programmatic shifts would result only in more, never less, funding for schools.

Rebenching Can Make Policy Sense but Opens Up Pandora’s Box…To date, rebenching largely has been used to account for shifts in local property tax revenues to or away from schools. In these cases, rebenching can make policy sense because local property tax and General Fund revenues are considered fungible. For example, when the state has redirected local property tax revenues away from schools to other local governments, then General Fund support for schools has been increased to backfill for the loss of local revenue. Though these types of changes seem reasonable, the administration’s rebenching proposals open up a Pandora’s box of other rebenching possibilities. For example, if the state rebenches for the gas tax change (in an effort to hold schools harmless for the loss of sales tax revenue), should it also rebench for the administration’s realignment proposals (in a similar effort to hold schools harmless for the loss of sales tax and vehicle license fee revenue)? Moreover, if the state rebenches for policy decisions that result in the loss of certain General Fund revenues, then should it also rebench for policy decisions that result in increases in General Fund revenues (such as personal income tax rate increases)?

…The Swarm of Questions Continues. Rebenching due to shifts of program responsibility can be almost as problematic as revenue–related rebenchings. For example, given school districts have responsibility for all other special education services, does assuming responsibility for student mental health services reflect a shift of program responsibility? Moreover, should the state rebench only when program responsibilities are shifted between schools and other agencies or should rebenching apply more generally when schools are required to perform any new service? Conversely, should rebenching occur when schools are no longer required to perform existing services (for example, if home–to–school services or after–school programs were eliminated)? Along these lines of thinking, should the state rebench every time a major categorical program is created or eliminated, as most categorical programs are linked to the provision of specific services?

Rebenching Fraught With Implementation Issues. Even if one were to set aside these fundamental legal and policy issues, other implementation issues would remain. One major implementation issue is how exactly to adjust the minimum guarantee. For example, the administration’s May Revision plan uses a different rebenching method than the rebenching method used for previous local property tax shifts. Had the administration used the traditional rebenching method, the effect on the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee would have been significantly smaller. Moreover, for the mental health shift, the administration is rebenching based upon an extremely high estimate of existing program costs. If one of the major reasons these services are being shifted to school districts is because the existing program structure lacks incentives to contain costs, then the Legislature likely would want to reevaluate the amount that should be used for rebenching purposes. Furthermore, depending on the overall state budget situation, the Legislature might want to revisit more generally whether it can afford either of the administration’s rebenching proposals.

|

Additional Funding Designated for Paying Down Deferrals. Whereas the March package contained a new $2.2 billion deferral of K–14 payments in 2011–12 (bringing total K–14 deferrals up to $10.4 billion), the May Revision provides $2.8 billion to eliminate the new 2011–12 deferrals and begin paying down prior–year deferrals. Specifically, the May Revision provides $2.5 billion to reduce K–12 deferrals and $350 million to reduce CCC deferrals. These payments would reduce the state’s outstanding Proposition 98 deferrals to $7.6 billion.

Other Notable Proposals. The May Revision also contains three major policy proposals:

- Shifts Student Mental Health Services to School Districts. In contrast to his January proposal, the Governor’s May Revision proposes to make school districts (rather than counties) responsible for providing students with educationally necessary mental health and residential support services. The May Revision contains a total of $389 million to support these services in 2011–12.

- Undertakes Education Mandate Reform. The May Revision contains an education mandate reform package that would eliminate 27 K–14 mandates and reduce the costs of 13 K–14 mandates—achieving $41 million in associated savings.

- Proposes Task Force to Reform State’s Testing and Data Systems. In the May Revision, the administration raises several concerns with the state’s existing accountability system, including excessive testing requirements and cumbersome data requirements. The administration proposes to address these issues by bringing together a group of teachers, scholars, administrators, and parents to identify ways to reduce testing time and eliminate unnecessary data collections. The May Revision also eliminates funding for the state’s longitudinal student and teacher data systems.

Budget Outlook Improved but Districts Still Face Uncertainty and Timing Issues

Despite the proposed $3 billion increase in Proposition 98 funding, the May Revision does not reflect a major program expansion from the budget plan adopted in March. This is because the bulk of the additional Proposition 98 funding is associated with paying down deferrals (that is, making existing school payments on time) rather than increasing the level of programmatic spending. Under the May Revision, per–pupil programmatic spending goes up only $40—from $7,693 to $7,733—with virtually all of the increase attributable to including mental health funding within Proposition 98. Because of the improvement in the state’s fiscal condition and the propect of reduced deferrals, school districts face less budget uncertainty today than in March. While uncertainty has been reduced, it has not been eliminated entirely. As a result, school districts continue to face timing issues that likely will result in some of them planning for programmatic cuts.

Increase in Baseline Revenues Significantly Improves Districts’ Budget Outlook. School districts must have their 2011–12 budgets finalized by July 1. As a result, without a complete, adopted state budget, school districts often build their budgets and make their related staffing decisions assuming a “worst–case” scenario. Under these scenarios, school districts prior to the May Revision were planning for potential Proposition 98 reductions of up to $4.5 billion. School districts now face an improved budget outlook. As noted above, improvement in state General Fund and local property tax revenues result in substantial additional Proposition 98 funding. As a result of this improvement, cuts as deep as $4.5 billion are much less likely.

Risk of Tax Proposals Not Passing and Having a Deferral Means Some Districts Still Likely to Make Cuts. Unless the state adopts tax proposals prior to July 1, many school districts likely will feel compelled to continue making budget and staffing decisions assuming no such tax proposals. Nonetheless, a lower level of Proposition 98 funding likely would not result in major programmatic reductions, particularly if the state maintained the already adopted payment deferrals. Though districts likely will budget based on this same set of assumptions, the effect will vary partly depending on a district’s ability to borrow. If a district believes it will be able to access short–term cash to cover a large deferral, then it will support a higher programmatic level. In contrast, if a district believes it will be unable to access short–term cash to cover such a deferral, then it very likely will make corresponding cuts rather than budget at the May Revision programmatic level. In a survey we conducted earlier this year, approximately 40 percent of districts reported that they would not access cash to cover an additional deferral. In short, though no longer planning for the worst–case scenario considered in March, some districts will continue to consider some programmatic cuts due to remaining concerns over timing and borrowing capacity.

Administration’s Proposition 98 Priorities Generally Reasonable and Responsible

We believe the administration’s May Proposition 98 plan is generally reasonable and responsible and recommend the Legislature adopt most of its major components. Specifically, if the final state budget package were to contain revenues able to support the May Revision level of spending, we recommend the Legislature adopt the administration’s plan to rescind previously adopted deferrals. In addition, regardless of the revenue situation, we recommend the Legislature adopt the Governor’s proposal to shift mental health responsibilities to school districts as well as his proposal to undertake mandate reform. (We recommend the Legislature reject the administration’s proposal to defund the state’s student and teacher data systems.

Paying Down Deferrals Improves Fiscal Health. By not creating new programs and instead paying down deferrals, the May Revision provides benefits to both the state and school districts. From the state’s perspective, outstanding state obligations as well as out–year state budget shortfalls are reduced. From districts’ perspective, less borrowing is needed, thereby reducing associated transaction and interest costs and potentially allowing districts to build back some programmatic support and/or replenish their reserves. From both perspectives, using additional funds for deferrals is fiscally responsible.

Overall Assessment of the Governor’s Plan

As described above, the Governor’s May Revision proposal generally maintains the same framework as his January proposal. As such, it has many of the same positive features and concerns as his original plan.

Positive Aspects of the Proposal

Uses Reasonable Estimates. In putting together its revised proposal, the administration had to make a variety of estimates: the problem definition, caseload and other spending requirements, revenues, and the value of proposed solutions. Generally speaking, we find their 2010–11 and 2011–12 numbers to be reasonable. As noted earlier, with regard to the most important variable—updated revenues—our near–term estimates are very similar to those of the administration. We expect to complete a more thorough

multiyear budget forecast in the coming days.

Achieves Operating Balance for Next Several Years. As in January, the proposal not only balances in the budget year, but, according to the administration’s estimates, would tend to stay in the black over the forecast period. While the temporary nature of the major tax proposals raises longer–term issues, the plan would achieve the important goal of bringing annual spending and resources much closer in line over the forecast period.

Recognizes the “Overhang” of Other Budgetary Obligations. In addressing past budgetary shortfalls, the state has taken actions that have worsened its future fiscal situation. These actions—primarily spending deferrals of various types and borrowing—have resulted in an overhang of debt and obligations that will weigh on the Legislature’s budget deliberations for years to come. Under current law, billions of dollars of these obligations are scheduled to be retired in the next few years. The administration, however, has proposed using a portion of the growth in General Fund revenues to retire more of these obligations, as well as committing to further “buy–downs” in the future. While the exact nature of those commitments—particularly with regard to school–related payments—is unclear, the administration’s attention to these longer–term obligations is commendable.

Offers Some State Operational Efficiencies. Through various executive orders and decisions in recent months and numerous proposals in the May Revision, the administration has provided means of achieving some savings and changes in state governmental operations.

Concerns With the May Revision Proposal

Uncertainties Caused by the Election Contingency. The Governor continues to propose that his major tax proposals and linked realignment plan be approved by the voters. While the May Revision document does not specify a date, the Governor appears to prefer a time earlier in the fiscal year rather than later. The problem with this plan is that it creates enormous uncertainty for both the state and local governments. For example, school districts, which need to make budget–year staffing and other decisions in the near future, will not know whether to budget based on the higher Proposition 98 funding level in the May Revision, the minimum guarantee should no tax proposals be adopted, or some level below that (should rejection of the tax measures require even more significant reductions).

Counties will face the same types of uncertainties. Since the administration’s realignment proposal is linked to the tax measures, they will be up in the air as to their new responsibilities until the voters have decided. If the voters reject the measures, they could also face additional state reductions in programs they administer in order to bring the budget back into balance.

Finally, the state also faces uncertainty in the case of a midyear election. As the Treasurer has already noted, the risk associated with such an election would make it difficult to obtain the external intrayear borrowing that is needed to address the state’s cash needs. In addition, if the voters rejected the tax measures, the state would have to reconsider various reductions to state programs in order to bring the budget back into balance.

Issues With the Governor’s Tax Proposals. Despite the noted improvement in state revenues, the Governor has chosen not to change his proposals to extend the higher tax rates on the state’s two major taxes (with the exception of a one–year delay in the PIT surcharge). The state’s sales and PIT rates are currently among the highest in the country. Keeping these rates as competitive as possible can contribute to the state’s longer–run economic health. With regard to his other tax proposals, we would rather have seen the administration stick with its original proposal to eliminate enterprise zones, and we continue to have concerns about the cost–effectiveness and other features of the hiring credit. As to his proposal to exempt some manufacturing equipment from sales taxes, we think the Governor has raised legitimate concerns about the taxation of business intermediate goods. His specific proposal to treat start–ups more generously than existing businesses, however, creates unnecessary and distorting distinctions among businesses.

How Should the Legislature Address the Remaining Problem?

After accounting for actions taken to date and growth in baseline revenues, the Legislature still needs to address a remaining budget–year shortfall of about $10 billion. Below, we offer our advice to the Legislature on how to approach this problem.

Evaluate the Spectrum of Options. The May Revision document states that, “Absent the balanced approach proposed by the Governor, the options are either an ‘all cuts’ budget or a combination of gimmicks and cuts.” Clearly, this is not the case. The Legislature has many options to address the remaining shortfall, including: (1) adoption of some of the administration’s revenue proposals, (2) consideration of other revenue proposals, (3) additional program reductions, and (4) selected fund transfers and internal borrowing.

Maximize Ongoing Solutions. Through its actions and improved revenues, the Legislature has already addressed about half of its ongoing structural shortfall. Last November, we suggested in our Fiscal Outlook that such a target would be a productive first step in chipping away at the state’s persistent operating shortfall. The state, however, is now in a position to make more significant inroads into the problem. Whether through revenue or expenditure solutions, we strongly urge the Legislature to maximize the amount of ongoing solutions in addressing the remaining problem.

Prioritize Revenue Increases. In considering proposals that increase revenues, the Legislature must always struggle with the trade–off between avoiding undesired program reductions and the impact of increased taxes on individuals and businesses. As such, we think the Legislature should carefully prioritize such tax proposals. In our view, the Legislature should give highest priority to tax provisions which eliminate distortions among taxpayers or for which the evidence is not persuasive regarding their effectiveness. It is on these bases that we have recommended approval of the Governor’s proposals to eliminate enterprise zones and require single sales apportionment for corporations. We would give next priority to proposals which achieve a desired tax policy objective. For example, we think the administration’s VLF proposal accomplishes the goal of the state taxing property at a similar rate.

Provide as Much Certainty as Possible. As discussed above, a budget that is based on the approval of voters for key provisions can create huge uncertainty at the state and local government levels. At this point, the outcome providing the most certainty would be the Legislature and Governor reaching a budget agreement without going to the voters. If, however, the tax measures are to go before the voters, it might be preferable to have the election at the end of the fiscal year. In this case, parties affected by the budget would at least have certainty as to funding levels for the entire fiscal year.

Incorporate the Governor’s Emphasis on Budgetary Obligations. Regardless of the components of a final budget package, we think the Legislature should incorporate the Governor’s focus on the state’s large fiscal obligations in its budgetary deliberations. This could be done in many ways. For example, the Legislature could adopt the Governor’s approach of scheduling the repayment of various Proposition 98–related obligations. With regard to infrastructure spending, the Legislature could improve its oversight and prioritization of bond fund expenditures in order to minimize the impact of growing debt–service payments. Furthermore, as the economy and revenues improve, it could specify its priorities for (1) paying off other obligations (such as special fund loans), (2) improving funding of long–term commitments (such as retiree health benefits), and (3) reversing the numerous revenue acceleration and accrual policies adopted in recent years in order to enhance investor and public confidence in the state’s accounting practices.

Conclusion

In recent budgets, the state has not been able to make significant inroads into its underlying operating shortfall. The reliance on one–time and short–term solutions has meant that the Legislature and Governor have had to address each year a large budget problem. This year is different. An improved economic and revenue situation, along with significant budgetary solutions already adopted, mean that the state is in a position to dramatically shrink its budget problem. The Governor has offered a serious proposal worthy of legislative consideration. The Legislature, however, has a variety of other tax and spending actions it could take to more closely align state revenues and expenditures now and in the future.