Executive Summary

The Governor presented a 12–point plan to change pension and retiree health benefits for California’s state and local government workers on October 27, 2011. This report provides background on the state’s retirement policy issues and our initial response to the Governor’s proposals.

Our Office’s Key Principles on Public Retirement Benefits. As we have noted in the past, we do not view the current system of defined benefit pensions for California’s public employees as an intrinsically bad thing at all. Rather, we view pensions and retiree health benefits as just one part of overall public employee compensation—in many cases, as benefits offered in lieu of what otherwise might be higher salaries over the course of a public–service career. Moreover, we believe that encouraging public or private workers to defer a portion of their compensation to retirement represents sound public policy. Well–managed and properly funded retirement systems, therefore, are meritorious.

What Is the Problem With Public Retirement Benefits?

California’s current structure of public employee pension and retiree health benefits has some substantial problems. There is a notable tendency in the current system for public employers and employees to defer retirement benefit costs—which should be paid for entirely during the careers of retirement system members—to future generations. This leads to unfunded liabilities that have spiraled higher in recent years and are producing cost pressures for the state and many local governments that will persist for years to come. Under the current system, governments have very little flexibility under case law to alter benefit and funding arrangements for current employees—even when public budgets are stretched, as they are today. Finally, there is a substantial disparity between retirement benefits that are offered to public workers and those offered to other workers in the economy.

Sustaining a financially manageable system of public employee retirement benefits—one that is more closely aligned with the benefits offered private–sector workers—will require substantial, complex, and difficult changes by the Legislature, the Governor, local governments, and voters.

Governor’s Proposal Is a Bold, Excellent Starting Point

Would Help Increase Public Confidence in California’s Retirement Systems. We view the Governor’s proposal as a bold starting point for legislative deliberations—a proposal that would implement substantial changes to retirement benefits, particularly for future public workers. His proposals would shift more of the financial risk for public pensions—now borne largely by public employers—to employees and retirees. In so doing, these proposals would substantially ameliorate this key area of long–term financial risk for California’s governments. At the same time, the Governor’s proposals aim for a future in which career public workers receive a package of retirement benefits that would be (1) sufficient to sustain employees’ standards of living during their retirement years and (2) more closely aligned with benefit packages offered to private–sector workers. For all of these reasons, we believe that the Governor’s proposals could increase public confidence in the state’s retirement benefit systems.

Many Details Left Unaddressed in Governor’s October 27 Presentation. Despite the strengths of the Governor’s pension and retiree health proposal, it leaves many questions unanswered. In particular, we do not understand key details of how his hybrid benefit and retirement age proposals would work. Moreover, the Governor’s plan leaves unaddressed many important pension and retiree health issues, including how to address the huge funding problems facing the state’s teachers’ retirement fund, the University of California’s (UC’s) significant pension funding problem, retiree health benefit liabilities, and other issues. In making significant changes to pension and retiree health benefits, we would urge the Legislature also to tackle these very difficult issues concerning the funding of benefits.

Raising Current Workers’ Contributions Is a Legal and Collective Bargaining Minefield. The Governor proposes that many current public employees be required to contribute more to their pension benefits. Others have proposed reducing the rate at which current employees accrue pension benefits during their remaining working years. Our reading of California’s pension case law is that it will be very difficult—perhaps impossible—for the Legislature, local governments, or voters to mandate such changes for many current public workers and retirees. Moreover, employer savings from these changes likely will be offset to some extent by higher salaries or other benefits for affected workers. Given all of these challenges, we advise the Legislature to focus primarily on changes to future workers’ benefits. Such changes should produce net taxpayer savings only over the long run but are certain to be legally viable.

A Golden Opportunity to Make These Benefits More Sustainable

Clearly, there is significant public concern about public pension and retiree health benefits. In our view, the current structure of these benefits—wherein state and local governments provide compensation in forms that are very different from that offered in the private sector—impairs the public’s ability to assess whether government is carefully managing its funds and can affect the public’s trust in government itself. We believe that the Legislature, the Governor, and voters should change these benefits—as well as the way in which governments and workers fund the benefits—in order to address these problems. These changes will involve difficult, complex choices. In the end, however, we believe that such changes can result in the public becoming more comfortable with public retirement benefits. This, in turn, will help ensure that the state and local governments can continue offering such benefits in the future.

Background: Public Pension and Retirement Benefits Today

A Complex System of Public Pensions

Not Just One Pension System…But Many. During the first half of the 20th Century, California began to implement a public policy to provide a comprehensive set of retirement benefits to its retired public employees. Public employees typically begin to accumulate rights to receive future benefits the moment that they are hired, and the longer that they work in the state or local government sector in the state, the more pension and other retirement benefits they accumulate. This policy continues today.

Today, pension and retiree health benefits for California’s public employees are determined in a largely decentralized fashion. This means that employees of the state, the public universities, school districts, community college districts, cities, counties, special districts, and other local governments earn a variety of different pension and retiree health benefits during their careers. As such, any effort to modify pension and retiree health benefits for public employees will prove complex, dealing as it may with a variety of different governments, benefit plans, and pension systems.

A Variety of “Defined Benefit” Pension Plans. California has both statewide and local public pension plans that offer defined benefits. Defined benefit pensions provide a specific amount after retirement that is generally based on an employee’s age at retirement, years of service, salary at or near the end of his or her career, and type of work assignment (for instance, public safety or non–public safety work assignment). In total, about four million Californians—11 percent of the population—are members of one or more of the state’s 85 defined benefit public pension systems. This four million figure includes about one million people who now receive benefit payments and around 700,000 “inactive” members—that is, individuals who were once, but are not currently, public employees and who do not yet receive pension benefits.

The two largest entities managing state and local pension systems in the state are the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) and the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS). Combined, these two statewide systems serve 3.1 million active and inactive members, including around 750,000 members and beneficiaries now receiving benefit payments. While both CalPERS and CalSTRS operate pursuant to state law, they are very different.

Members of CalPERS include current and past employees of state government and California State University (CSU), as well as judges and classified (nonteacher) public school employees. In addition, hundreds of local governmental entities (including some cities, counties, special districts, and county offices of education) choose to contract with CalPERS to provide pension benefits for their employees. Local governments can choose from a variety of plan options in CalPERS, as allowed in the state’s Public Employees’ Retirement Law. Governmental employers make contributions to their current and past employees’ pension benefits, as in most cases, do public employees themselves. Each employer generally is responsible for its own employees’ costs in CalPERS, meaning that the state does not directly contribute to CalPERS to cover pension costs for local government employees. (Local governments, however, often do use a portion of various funding streams they receive from the state government to pay a part of their own pension costs.)

Different governmental entities in CalPERS have a variety of pension contribution arrangements with their employee groups, meaning that some employees pay more or less than other, similarly situated employees of other governmental entities. In practice, various elements of CalPERS benefits—benefit amounts and employee contributions—now are determined in collective bargaining with unions that represent rank–and–file state and local government employees.

Compared to CalPERS, CalSTRS offers an entirely different—often less generous—set of benefits to teachers and administrators of California’s public school and community college districts. Benefits offered by CalSTRS, as well as required payments by employees, districts, and the state, are specified on a statewide basis in the state’s Education Code—that is, they apply on a generally equal basis to all districts. As such, CalSTRS benefits generally are not determined through collective bargaining. Unlike many CalPERS members, CalSTRS members generally do not participate in Social Security.

In addition to CalPERS and CalSTRS, about 80 other defined benefit state and local pension systems (such as the University of California Retirement Plan [UCRP], the Los Angeles County Employees Retirement Association, and the Los Angeles City Employees’ Retirement System) serve about one million other Californians, including about 300,000 who currently receive benefit payments. County pension plans generally are governed by the state’s County Employees Retirement Law of 1937 (known as the “1937 Act”). Benefits and employee and employer contributions in these various other plans can vary widely—typically, subject to negotiation with rank–and–file employee unions.

“Defined Contribution” Plans Also Now in Place for Some Public Employees. Many public employees currently are enrolled in defined contribution plans, which are intended to supplement their defined benefit pensions after they retire. Defined contribution plans include 401(k), 403(b), and 457 plans in which the rate of contribution by the employer is fixed, sometimes serving in practice as a “match” to amounts deposited to those funds by employees. Accordingly, an employee’s defined contribution plan benefits equal what amount the accumulated employee and employer contributions can provide at retirement, plus investment earnings. Unlike defined benefit plans, therefore, defined contribution plans do not promise a specific amount to be paid to the retiree each month or each year. Some governmental entities manage defined contribution plans, often in conjunction with private–sector investment managers. For example, state employees can enroll in defined contributions plans managed by the Savings Plus Program of the Department of Personnel Administration (DPA). Some teachers also enroll in CalSTRS’ Pension2 supplemental savings plan. A variety of other public and private defined contribution plans serve California’s local governments and school districts.

Social Security. Social Security—established in the 1930s—initially did not provide benefits to public employees, but in the 1950s, the federal government approved amendments to the Social Security Act to allow states to enter into agreements with the Social Security Administration to provide such benefits to their public employees. Over time, Congress has added to these requirements, essentially mandating Social Security for specified public employees not covered by a qualified public pension plan.

It has been estimated that only about one–half of California’s public employees participate in the federal Social Security program. Teachers and most public safety officers, including corrections officers, police, and firefighters, generally are not enrolled in Social Security. There are a variety of reasons why this is so. Public safety officers generally are eligible for retirements at earlier ages than envisioned under Social Security’s benefit formulas. Moreover, it is expensive for a government to initiate enrollment of its employees into Social Security without, at the same time, enacting reductions in its other pension benefits. While there has been some discussion over the years at the federal level of requiring all state and local employees to be enrolled in Social Security, this proposal has not been accepted to date, in part because of the cost pressures for state and local governments that would be affected.

Generally speaking, employees and employers in Social Security each contribute 6.2 percent of pay—up to the Social Security earnings cap (now $106,800 per year)—to the federal government in the form of Social Security payroll taxes. (Congress reduced employee payroll taxes in 2011 to help stimulate the economy.) The federal government essentially uses these funds—in addition to amounts paid from the federal government’s general fund—to pay Social Security benefits to current retirees. (This means that Social Security benefits—unlike state and local pension benefits—are paid on a “pay–as–you–go” basis, essentially making Social Security a social insurance system, rather than a pension system, as we think of it here in California.) Over time, as baby boomers age and the ratio of workers to retirees in the United States falls further, the federal general fund will have to pay more and more to cover the cost of Social Security benefits. For this reason, in the future it is likely that Congress will have to enact revenue increases and/or benefit reductions in order to keep the federal budget on a sustainable path.

For individuals born between 1943 and 1954, the Social Security “normal retirement age”—at which full Social Security benefits can be received—is now 66. For individuals born in the years 1955 through 1959, the Social Security normal retirement age is somewhere between age 66 and 67, as specified in law. For individuals born in 1960 and after, the Social Security normal retirement age is 67. (Individuals generally can receive reduced benefits if they retire earlier than the normal retirement age, provided that they are at least 62.)

Even More Variety for Retiree Health Benefits

Medicare. Medicare is a federal health program that covers individuals age 65 and older. It was established in 1965 and has long enrolled many state and local government employees. State and local government employees hired or rehired after March 31, 1986, are subject to mandatory coverage by Medicare. Employers and employees each currently pay a 1.45 percent tax on earnings to cover part of Medicare program costs, which consist of Part A (hospital insurance), Part B (outpatient medical insurance), Part C (Medicare Advantage plans), and Part D (prescription drug insurance). Individuals are eligible for premium–free Medicare Part A if they are age 65 or older and worked for at least 10 years (40 quarters) in Social Security and/or Medicare–covered employment. Accordingly, Medicare is now the core element of retiree health coverage for both public and private retirees in the United States. In many public pension plans, including CalPERS, Medicare–eligible retirees generally must enroll in Part B benefits at age 65 (or earlier, if they are qualified due to a disability). In 2011, Medicare Part B premiums typically have been around $100 per month.

Retiree Health Programs of State and Local Governments. While Medicare is now the core component of retiree health coverage for state and local workers, there is much variety among state and local governments in the area of retiree health care. Many local governments—especially school districts—offer virtually no retiree health care benefits. The state and many other local governments, however, offer a range of retiree health benefits that vary from small to expansive. Of these governments, many, including the state, provide health benefits to pre–Medicare retirees, and others—also including the state—offer Medicare supplement plans to retirees after age 65. Retiree health benefits have been subject to extreme cost pressures in recent years due to the general growth of health care expenses, a rise in the number of retirees drawing the benefits, and costs resulting from growing unfunded liabilities, which are discussed below.

For Many Career Employees, a Generous Set of Benefits

As described above, there is considerable variety among California’s public retirement systems. As such, it is difficult to generalize about the specific benefit packages provided to public workers and retirees today. Moreover, there have been numerous changes to benefits in recent years—some enacted through legislation and others negotiated at the bargaining table. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a wave of benefit enhancements—most notably, those related to Chapter 555, Statutes of 1999 (SB 400, Ortiz)—affected benefits for state and many local employees. More recently, governmental budget problems, combined with growing public concern about retirement benefit costs, have resulted in a wave of benefit reductions—particularly for future employees—and employee contribution increases. These have affected most state employee groups, as well as some local employee groups.

Replacement Ratio: Less Income Generally Needed in Retirement. A person’s income needs generally are less in retirement than when working. This is because clothing and daily travel expenses decline, home mortgages may be paid off at this point in life, and retirees may be in a lower tax bracket than when working. As a result, retirees typically need less income to maintain the same standard of living as when they worked.

The percentage of income a person has in retirement compared to his working income prior to retirement is called the “replacement ratio” or “replacement rate” by retirement experts. When pension benefits are compared to each other, it is typically this replacement ratio that is being compared. When we speak of pension benefits being “generous,” we mean that they provide a relatively high replacement ratio compared to other benefit plans in the public and/or private sectors.

In 2005, a publication of Boston College’s Center for Retirement Research said, “Overall, the range of studies that have examined [the] issue consistently finds that middle class people need between 65 percent and 75 percent of their pre–retirement earnings to maintain their lifestyle when they stop working.” This paper indicated “that the majority of households retiring today are in pretty good shape,” with about two–thirds of households then in that 65 percent to 75 percent replacement ratio range. The paper, however, suggested that “the coming way of baby boom retirees…will see lower replacement rates from Social Security and less certain income from employer pensions.” Similar to the 2005 study, a 2010 U.S. Census Bureau paper found that replacement rates for the median individual—as of 2004—was between 66 percent and 75 percent of pre–retirement income.

State and Local Government Benefits (Not Including Teachers). In our 2005 publication, The 2005–06 Budget: Perspectives and Issues (see page 132), we compared state “miscellaneous” (non–public safety) pensions then in place with those of 15 other states. Of the states we surveyed, California offered the highest retirement benefits. We also discussed the generous nature of public safety pension benefits and local government benefits then in place.

Since 2005, the state and some local governments have enacted pension benefit changes—particularly for new employees hired after a given date—and increased employee contributions, often through negotiation with rank–and–file union representatives. Nevertheless, some local governments have continued to offer particularly generous pension benefits, including “2.5 percent at 55,” “2.7 percent at 55” and “3 percent at 60” for miscellaneous employees, as well as “3 percent at 50” benefits for public safety employees. In pension parlance, for example, 2.5 percent at 55 means—in simplified terms—that a retiree can receive a benefit equal to 2.5 percent (the benefit factor or multiplier) of his or her final compensation multiplied by the number of years of service if retiring at 55. Lesser benefits are available if they retire earlier than 55, and higher benefits may be available in a formula if a person retires after the age indicated in the formula. As we suggested in our 2005 report, these kinds of generous benefit levels result in some career public service workers receiving pension benefits above—and in some cases, well above—the 65 percent to 75 percent replacement ratio described above, particularly when Social Security and other sources of retirement income are considered. While the state and some other public entities have negotiated with employees for reductions in these generous benefit formulas, CalPERS’ most recent annual report shows that a few governments were still switching to some of these particularly costly benefit packages as recently as 2009–10.

The most recent version of a public pension comparison report prepared periodically by the Wisconsin Legislative Council indicates that, for public employees in Social Security, pension benefit “multipliers” of 2.1 percent or higher are rare—available for only 7 percent of surveyed plans. The report found that, among comparable plans, the average pension benefit multiplier was 1.94 percent. For pension plans serving public employees not in Social Security, the report found the average benefit multiplier was 2.3 percent.

We believe that the data shows that defined pension benefits offered to California’s state, city, county, and special district employees have been among the most generous in the country in recent years. While there have been some reductions in these benefits recently, some California governments still offer among the most generous defined pension benefits available anywhere in the United States public or private labor market today. In many cases, California public pension benefits for career public employees—coupled with other sources of retirement income—can replace far more than the 65 percent to 75 percent income replacement ratio described earlier.

Teachers. Several reports have indicated that teachers enrolled in CalSTRS receive less generous benefits than other kinds of public employees in California. In 2009, CalSTRS staff presented to the Teachers’ Retirement Board a study examining replacement ratios for teachers under CalSTRS benefit formulas that were to be in effect in 2011. The CalSTRS report found that the median CalSTRS retiree as of 2011 (retiring after 29 years of service) would have a retirement income replacement ratio of 78 percent. This consisted of a CalSTRS defined benefit of $3,914 per month, a defined benefit supplement program payment of $93 per month, and a supplemental annuity payment from a defined contribution plan of $613 per month. (This defined contribution component represented about 13 percent of the total assumed retirement income for the median CalSTRS retiree.) The study assumed that the median CalSTRS retiree invested $100 per month over a 25–year career in a defined contribution account.

In addition to considering the median CalSTRS retiree, the study also showed replacement ratios for CalSTRS retirees at the 25th and 75th percentiles of income, respectively. The replacement ratio for the 25th percentile retiree (retiring after 18 years of service) was 42 percent, while the replacement ratio for the 75th percentile retiree (retiring after 35 years of service) was 103 percent. The report said that teachers retiring without employer–subsidized health coverage would need more income to maintain a suitable replacement ratio. Specifically, it listed a “recommended replacement ratio” of around 77 percent of final compensation for those retired teachers with health care benefits and around 89 percent for those without health care benefits.

Retirees With Benefits of $100,000 Per Year or More. In recent years, there has been considerable public attention related to retired California public employees receiving annual pension benefits of $100,000 or more. These individuals are a small, but growing, segment of California’s public sector retirees. About 2 percent of CalPERS and CalSTRS retirees currently receive such payments. Payments to these retirees now equal around 7 percent to 9 percent of total pension payments from the two systems. During their working lives, these retirees generally were among the longest–serving and highest–paid public employees—for example, senior executives and managers of some state and local agencies, school districts, and community colleges, as well as some employees in public safety agencies.

The percentage of CalPERS, CalSTRS, and other public retirees receiving pension benefits of over $100,000 per year will grow in the future for several reasons. These reasons include the effects of inflation (which tends to increase all employees’ pay and pension benefits over time) and the effects of increased pension benefit provisions put in place in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Beyond the group of retirees receiving payments of $100,000 or more per year, many public retirement systems can expect to see the percentage of their retirees with higher pension benefits—and the amounts of those benefits—grow for these same reasons. This trend is already apparent in data provided by the pension systems. In its financial reports, for example, CalPERS publishes statistics on the characteristics of employees retiring in each fiscal year. In 2003–04, 4,831 people retired with 30 or more years of service, and this group retired with an average monthly pension of $4,553 (equating to $54,636 per year). In 2008–09, there were 5,801 retirees with 30 or more years of service, and they had an average monthly pension of $5,569 ($66,828 per year)—up 22 percent in non–inflation adjusted terms compared to the initial benefit of the 2003–04 retiree group. Growth in monthly pension benefits was even greater in percentage terms during this period for employees retiring with 10 to 30 years of service. For retirees with 25 to 30 years of service for example, the average initial pension grew from $3,308 per month ($39,696 per year) for 2003–04 retirees to $4,432 per month ($53,184 per year) for 2008–09 retirees—up 34 percent in non–inflation adjusted terms.

This data from CalPERS’ annual report suggests that while the average pension benefit for all CalPERS retirees (including those who retired decades ago) is around $25,000 per year, such average retirees are not responsible for the bulk of benefits that CalPERS will pay out in the future. For public employees who retired in 2008–09, the newest retiree group for which data is available, it appears that around 60 percent of CalPERS benefit costs are being paid to retirees with 25 or more years of service. The average annual benefit for this group is somewhere between $53,000 and $66,000—over double the amount paid to the average retiree in the system. For those 2008–09 retirees with 25 to 30 years of service, their monthly defined benefit pension is replacing an average 67 percent of their final career compensation; for those retirees with 30 or more years of service, the monthly defined benefit pension is replacing an average 79 percent of their final career compensation. Some of these retirees also receive Social Security benefits, and some also have defined contribution savings, which would increase their replacement ratios further. Over time, retirees like the 2008–09 cohort will become more of the norm in CalPERS and other public pension systems.

Tendency to Defer Costs to Future Generations

Unfunded Pension Liabilities. A troubling trend of California’s state and local public pension systems has been the growth of substantial unfunded actuarial accrued liabilities (UAAL). Put in very simple terms, an unfunded liability is the amount that would need to be invested into a public pension plan today such that, when coupled with amounts already deposited in the fund plus assumed future investment earnings, all benefits earned to date by public employees would be funded upon their retirement. While there is some disagreement on how to value unfunded liabilities of pension systems, it is clear that California’s state and local systems are coping with very large shortfalls. These shortfalls will push costs upward—above what they otherwise might be—for years to come, in some cases.

As of June 30, 2009, CalPERS reported that its UAAL in its main pension fund for state and local governments was over $49 billion—consisting of about $23 billion for the state and $26 billion for other public agencies. Because the UAAL uses data that “smoothes” investment gains and losses over extraordinarily long periods of time, CalPERS tends to communicate its funded status by another, more volatile measure that relies on the market value of its investments at any given time. By this measure, CalPERS’ main pension fund was 61 percent funded with a $115 billion unfunded liability, split between the state and other public agencies. In 2009–10, buoyed by favorable investment performance, CalPERS reports that its funded status improved somewhat—to around 65 percent when measured based on the market value of assets. Fiscal year 2010–11 saw even more favorable investment returns.

Unlike CalPERS, but like most other pension systems, CalSTRS recognizes investment gains and losses in its actuarial valuations over a multiyear period. Due to the near–collapse of world financial markets in 2008, CalSTRS and other pension systems sustained heavy losses, and the continued recognition of those losses is the major driver of the system’s growing reported UAAL. The most recent CalSTRS valuation indicates the system’s UAAL grew from $40.5 billion as of the 2009 valuation to just over $56 billion as of June 30, 2010. This means that CalSTRS’ reported funded ratio dropped from 78 percent as of the 2009 valuation to 71 percent in the June 30, 2010 valuation.

Pension systems in California and elsewhere reported growth in their UAALs after the 2008 market collapse and then experienced a recovery in their funded status during the relatively strong investment markets of 2009–10 and 2010–11. These trends illustrate a primary reason that unfunded liabilities emerge: weaker–than–expected investment returns. Lower–than–expected investment returns have been a primary reason for growth of unfunded pension liabilities in the last decade. Such investment weakness—relative to some pension systems’ assumption of 7.5 percent to 8 percent investment return per year—has given fuel to critics, who believe that these assumptions are imprudent and understate costs that governments and employees should contribute for a given set of benefits.

Other reasons for unfunded liabilities include benefit increases that are implemented retroactively (that is, applied to previous years of service before the benefit enhancement is implemented) and demographic and pay changes among employees and retirees. If retirees live longer than expected by plan actuaries, unfunded liabilities can result. If employees are paid more than expected during their career relative to assumptions of plan actuaries, this also can contribute to unfunded liabilities.

Unfunded Retiree Health Liabilities. For many governments, the size of unfunded retiree health liabilities has rivaled or exceeded their unfunded pension liabilities. In contrast to pensions, governments typically have not “pre–funded” their retiree health liabilities. In other words, they generally have never set aside funds—or required employees to do so—to cover the future costs of retiree health benefits earned during their working lives. This means that future taxpayers may bear a larger cost burden for these benefits. Unlike pensions, there are no investment returns under this type of funding structure to cover a large portion of benefit costs. While a small portion of governments have begun to pay down their unfunded retiree health liabilities, such liabilities will remain a pressing burden for many California public entities as the decades progress. The state government’s unfunded retiree health liabilities alone total about $60 billion, as of June 30, 2010, according to the State Controller’s Office. A report released by a commission in early 2008 estimated that all public entities in the state had a combined retiree health unfunded liability of over $118 billion as of that time; that total probably has grown since then.

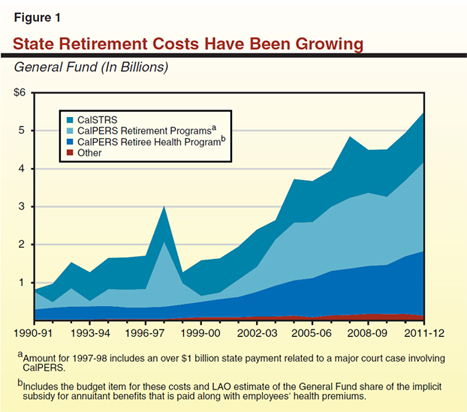

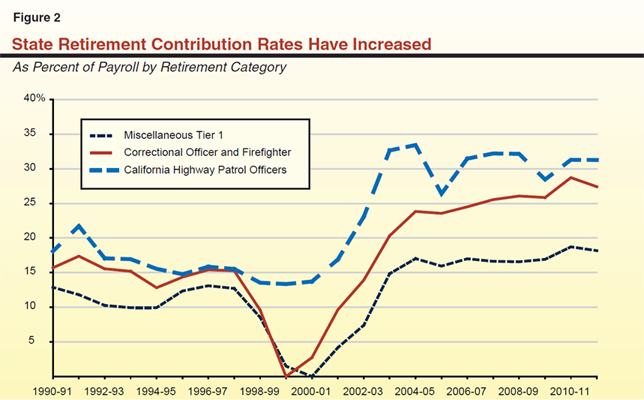

Unfunded Liabilities and Growing Benefits Have Increased Costs. Increased benefits and the emergence of large unfunded liabilities have increased pension and retiree health costs for many California governments in recent years. In Figure 1, we show the trend of increasing state General Fund costs for retirement benefits in nominal dollars. A major reason for the magnitude of recent growth in state costs is the fact that public employers generally benefited from “pension holidays” in the late 1990s and early 2000s due to the stock market bubble that temporarily resulted in systems like CalPERS being fully funded or close to it. Figure 2 shows the contribution rates paid by the state as a percentage of pay for several key employee groups. (While state contributions as a percentage of pay were slightly higher in 1980—before the period covered in Figure 2—that period is not directly comparable to the present day since CalPERS at that time invested primarily in fixed–income bond instruments and assumed an annual investment return of only 6.5 percent.

Inflexible Benefits, Inflexible Costs

Strict Legal Limits on Changing Benefits and Reducing Government Costs. In our view, perhaps the most significant retirement benefit challenge facing California governments is that there is very little flexibility for governmental employers under decades of case law that are extremely protective of employee and retiree pension rights. In California, pension benefits for public employees are an element of a public employee’s compensation. He or she begins to accumulate pension rights at the moment of hiring, and these benefits accumulate throughout a public service career. There is a detailed case law in the state that protects these benefits as contracts under the State and U.S. Constitutions. Pension benefit packages, once promised to an employee, generally cannot be reduced—either retrospectively or prospectively—without a government’s offering comparable and offsetting advantages (which, themselves, can be quite expensive). The case law suggests that governments do have some power to alter benefits when they face emergency situations, but these powers are very limited, and governments, according to case law, generally will have to alter benefits temporarily, with interest accruing to employees and retirees in the meantime. In some cases, local governments may be able to alter contracts when they seek protection under Chapter 9 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code.

Negotiations Can Help, but Unions Must Represent Their Members. In general, the primary way that the state and local governments can change pension benefits for current and past employees is to negotiate with employee groups. As discussed above, the state and some local governments have successfully reduced pension costs recently through such negotiations. The challenge with this approach, however, is that unions have an obligation to represent their members, and so, in exchange for pension concessions, they generally will be duty bound to seek comparable, offsetting benefits for their members. For example, many of the recent state employee agreements that increased employee contributions to their pensions included future pay increases roughly equivalent to the increase in the employee pension contributions. This is understandable, given the history of the state’s benefit commitments and the obligations of unions to represent their members, but it limits governments to an extent from achieving lasting cost savings for current and past employees through the negotiation process.

For Future Employees, Government Can Alter Pension and Retiree Health Benefits. While governments have very little flexibility with regard to current and past employees’ retirement benefits, it is clear that they may change benefit promises prospectively for future hires without limit.

Disparity Between Public and Private Retirement Benefits

Underlying the real policy and fiscal problems of current public retirement systems is a sharp divide between public–sector and private–sector workers. Public–sector workers have guaranteed, defined–benefit pension plans, and many, but not all, of them have retiree health plans too. Private–sector workers by and large have none of these things anymore. The Governor’s proposal, in essence, aims to reduce this substantial disparity.

Governor’s 12–Point Plan

The Governor released his 12–point pension plan on October 27, 2011. In addition to making remarks at a press conference, the Governor released a short description of the goals of his plan. While some of the elements of the plan have been included in prior legislative vehicles (and the Governor released language for similar proposals on March 31), our review below is based primarily on the Governor’s pension handout from October 27 and his press conference, as well as subsequent contacts with administration staff concerning the plan. Draft legislative language to implement the Governor’s proposals would need to fill in many details absent from his October 27 presentation.

Below, we will review each of the 12 points in turn, providing, in some cases, some background information, a description of the Governor’s proposal, and our initial comments.

Equal Sharing of Pension Costs

Background

Normal Cost and Unfunded Liability Contributions. Contributions to pension plans from employers and employees consist of two main components: (1) “normal cost” contributions, which generally are equal to the amount actuaries estimate is necessary—combined with assumed future investment returns—to pay the cost of future pension benefits that current employees earn in that year and (2) contributions to retire unfunded liabilities. For example, CalPERS estimates that the normal cost for state Miscellaneous Tier 1 workers (such as state office workers and most CSU employees) is now 14.4 percent of their payroll. In addition, the annual cost to retire unfunded liabilities for Miscellaneous Tier 1 workers—plus some related benefit costs—equals 10.4 percent of payroll, for a total required contribution of 24.8 percent of payroll. For CalPERS’ state Peace Officer and Firefighter workers (principally state correctional officers), the normal cost is now 25.4 percent of their payroll, and the annual cost to retire unfunded liabilities is 11.3 percent of payroll, for a total required contribution of 36.7 percent of payroll.

Most State Workers Pay One–Half of Normal Costs and One–Third of Total Costs. Following the recent agreements of state employee unions to increase their employees’ contributions to CalPERS, over 70 percent of Miscellaneous Tier 1 workers contribute approximately 8 percent or more of monthly pay to cover pension costs. This 8 percent exceeds 50 percent of the normal cost contributions for these employees, but, for most, represents only about one–third of the total required contribution, including both normal costs and unfunded liability contributions. In the state Peace Officer and Firefighter group, about 80 percent of workers now contribute about 11 percent of their monthly pay to cover pension costs. This represents just under one–half of the normal cost contributions for these employees, but less than one–third of the total required contribution.

With Fixed Employee Contributions, Employers Cover Any Cost Changes. In current law and most employee contracts, employee contributions to their pensions generally are fixed. This means that the portion of the total required contribution not paid by workers generally is paid by the public employer—in this example, the state. While normal costs tend to remain fairly stable over time, assuming no changes in the pension benefit structure, unfunded liabilities can change markedly from year to year due mainly to upturns and downturns in the investment markets. Since employee contributions generally are fixed in labor agreements or state or local law, this means that the public employer can experience significant increases in total required contributions as unfunded liabilities increase and significant decreases in total required contributions when those liabilities drop.

Public Employee Contributions Vary. Like the state, some local public employers recently have negotiated with their unions to increase employee contributions to local pension plans. As the Governor points out, however, there remains a wide disparity among public employers in what portion of normal costs and total required contributions is borne by public employees themselves. In some cases, public employees make no such contributions. Various laws, agreements, and precedents allow some employers to pay a portion of their employees’ contributions to pension plans. In many cases, such a payment merely substitutes for pay the employers otherwise might choose to give to employees, but it means that some employees may see no real costs for their pension benefits when reviewing their pay stubs. There is concern among some that many of these public employees view their substantial pension as a sort of “free good.”

Proposal

Equal Sharing of Normal Costs, but Unclear If Sharing Would Apply to Other Costs. The Governor’s plan proposes that all current and future public employees be required to pay at least 50 percent of the normal costs of their defined pension benefits. This seemingly would mean that there would be no more employer payments of required employee pension contributions. This requirement would be phased in “at a pace that takes into account current contribution levels, current contracts and the collective bargaining process”—apparently, over several years.

The Governor’s proposal explicitly addresses only the employee share of normal costs and is unclear as to whether the 50 percent requirement also would apply to unfunded liability contributions. It is also unclear if the 50 percent requirement would apply to defined contribution fund deposits (which also can be split 50/50 between employers and employees, in theory).

Governor Says This Provides “Real Near–Term Savings.” By applying the increased employee payment requirement to both current and future public employees, the Governor states that this change would provide near–term cost relief for some public employers, since increased employee contributions would reduce contributions that public employers otherwise would have to make.

LAO Comments

Governor’s Proposal a Good Start in This Area. We agree with the Governor that future public employees should be required to pay for a portion of pension contributions. We believe it would enhance public confidence in state and local retirement systems for there to be a clear, unambiguous statewide policy in this area. There is no single correct percentage of total required contributions that employees should be required to pay, but 50 percent is a reasonable starting point for the discussion.

Important for Employees to Share in Unfunded Liability Costs Too. We urge the Legislature to require that future public employees bear a portion of not only pension normal costs, but also unfunded liability contributions. When public employers see their pension contributions go up due to a downturn in the stock market or similar reasons, employees should see their contributions rise as well. Similarly, when public employers see their pension contributions drop due to stock market upticks, employees should benefit from a reduction in their contributions.

Like many others, we are concerned that public retirement boards make excessively optimistic assumptions concerning future investment returns. We believe that requiring public employees to bear a portion of the cost (or benefit from a portion of the savings) when these assumptions prove inaccurate will incentivize retirement boards to make more prudent investment assumptions. Moreover, requiring employees to bear a portion of unfunded liability costs would reduce the year–to–year volatility of government contributions to pensions. In effect, this change would transfer a portion of this volatility risk from employers (who now generally pay all increases due to unfunded liabilities) to employees.

Case Law: Possible for Some Current Employees, but Probably Not for Many Others. At his press conference announcing the proposal, the Governor said his proposal addressed “existing employees by increasing their contribution rate.” He added, “One thing we know for sure: under constitutional law, the employer can require higher contributions.”

We do not share the Governor’s belief that existing constitutional law clearly allows the state to require current public employees to contribute more to pensions. To the contrary, such a proposal seems to run counter to existing constitutional protections in case law that may protect many current and past public employees. In the nearby box (see page 18), we summarize the case and statutory law in this area, which suggests that it might be possible to increase contributions for some current employees, but not for others. For many current employees, such contribution increases probably could be implemented only through negotiations, and in any event, would result in many employers increasing pay or other compensation to offset the financial effect of the higher pension contributions. Since increasing current employees’ contributions is one of the only ways to substantially decrease employer pension costs in the short run, the legal and practical challenges that we describe mean that the Governor’s plan may fail in its goal to deliver noticeable short–term cost savings for many public employers.

Strict Legal Protections Limit Government’s Flexibility

Our understanding of California’s detailed case law on public pensions over the last century is as follows: in order to have the flexibility to unilaterally implement cost–saving reductions to the pensions of current and past employees, public employers need to have explicitly preserved their rights to make such changes either at the time of an employee’s hiring or in subsequent, mutually–agreed amendments to the pension arrangement. Otherwise, reductions for these employees and retirees require that comparable, offsetting advantages be granted—advantages that tend to negate the pension savings.

“Comparable New Advantages” Generally Required When Disadvantaging Employees. The 1955 California Supreme Court case, Allen v. Long Beach, is an important landmark in California pension law. The court ruled that “changes in a pension plan which result in disadvantage to employees should be accompanied by comparable new advantages.” One of the pension amendments invalidated in Allen increased each employee’s pension contribution from 2 percent to 10 percent of salary. The Supreme Court, in fact, declared that this increased contribution requirement “obviously constitutes a substantial increase in the cost of pension protection to the employee without any corresponding increase in the amount of the benefit payments he will be entitled to receive upon his retirement.”

In Pasadena Police Officers Association v. City of Pasadena (1983), a state appellate court said the precedent in Allen meant that “where the employee’s contribution rate is a fixed element of the pension system, the rate may not be increased unless the employee receives comparable new advantages for the increased contribution.” The appellate court added that while “an increase in an employee’s contribution rate operates prospectively only and in effect reduces future salary…in Allen the Supreme Court struck down such a change on the grounds that it modified the system detrimentally to the employee without providing any comparable new advantages.”

What About Changing Future Benefit Accruals? The logic in the Allen and Pasadena Police Officers Association cases, among others, makes it very difficult to assume that state or local governments could unilaterally change the rate at which current employees accrue pension benefits for their future service, as has been suggested by various recent proposals. (The Governor does not make such a proposal.)

In a 1982 case, Carman v. Alvord, the California Supreme Court noted that upon “entering public service an employee obtains a vested contractual right to earn a pension on terms substantially equivalent to those then offered by the employer.” In the 1991 case concerning Proposition 140, the court considered that measure’s termination of then–incumbent legislators’ rights to earn future pension benefits through continued service. In that case, the court said the termination of the benefit accrual rights for these legislators was a contract impairment and was unconstitutional under the U.S. Constitution’s contract clause because it infringed on their vested pension rights. (Proposition 140, it should be noted, did end pension benefits for legislators elected after its passage.) Furthermore, in the Pasadena Police Officers Association case, the appellate court noted that an employee “has a vested right not merely to preservation of benefits already earned…but also, by continuing to work until retirement eligibility, to earn the benefits, or their substantial equivalent, promised during his prior service.”

Significant Challenges to Mandating That Current Workers Contribute More. While the case law described above is protective of current and past public employees’ pension rights, it indicates that governments may be able to unilaterally (that is, outside of negotiations) change elements of the pension arrangement if they have explicitly preserved the right to do so. For example, in International Association of Firefighters, Local 145 v. City of San Diego (1983), the California Supreme Court ruled that a city could increase employee contribution rates pursuant to city charter and ordinance provisions that allowed it to do so. Accordingly, some public employers that have carefully preserved such rights could unilaterally implement increases in current workers’ pension contributions.

We suspect that many local governments may not be in a good position to defend their ability to implement such increases. While several sections of the state’s CalPERS and 1937 Act laws purport to preserve the Legislature’s ability to increase certain CalPERS contribution rates or make clear that state law itself does not limit local governments’ ability to periodically increase, reduce, or eliminate their payments to offset required employee contributions, local governments—promising, as they do, a wide variety of retirement packages through dozens of retirement systems—may obligate themselves contractually.

Even in a 2009 decision upholding San Diego’s ability to impose higher employee pension costs at a bargaining impasse, the Ninth Circuit federal appeals court distinguished between legislatively enacted reductions in employers’ payment of a share of employees’ required pension contributions (allowable, the court ruled) and legislatively imposed increases in the total amount of required employee pension contributions themselves (implying the latter may be unallowable under contract law). The Ninth Circuit stressed that looking into a state or local legislative body’s intent was key to determining whether a retirement benefit provision was contractually protected. Accordingly, some local governments may have intended to include low employee contributions as a part of their pension contract, while others may not. This muddled, uncertain legal framework seems to us inconsistent with the Governor’s claim that governments have broad legal ability to mandate current employee contribution increases. Furthermore, even if unilateral increases are permissible under contract law, they will directly or indirectly result in many governments having to pay more to employees in salaries or other forms of compensation in order to remain competitive in the labor market. For example, recent increases in most state employees’ contributions negotiated with rank–and–file employees were accompanied by future salary increases of similar amounts.

Since increasing current employees’ contributions is one of the only ways to substantially decrease employer pension costs in the short run, these substantial legal and practical hurdles mean that the Governor’s plan may fail in its goal to deliver noticeable short–term cost savings to many public employers.

Key Lesson From Case Law: Governments Should Be Clear About Their Pension Rights. The case law makes clear to us that governments often have not been clear about what aspects of pension and retiree health benefits and contributions—if any—they can change unilaterally in the future and which they cannot. For this reason, we have recommended that the Legislature require local governments to explicitly disclose to employees—preferably, on the day that they are hired—which aspects of pension and retiree health benefits and contributions the public entity can change unilaterally (that is, without negotiation) and which it cannot. If it chose to do so, the Legislature could require that such disclosures reflect the results of collective bargaining and apply only to future employees. (Approval of such a requirement by voters may be necessary to avoid the state having to reimburse local governments for this disclosure mandate.)

|

Hybrid Pension Plan for Future Employees

Background

“Hybrid” pension plans generally combine a defined benefit pension with a defined contribution retirement savings plan. Accordingly, it is important to understand the characteristics of both such plans. The key difference between such plans is the handling of investment risk. In most defined benefit plans, such as California’s state and local pension systems, employers bear almost all investment risk. This means that if investment returns of the systems over time are less than projected, public employer costs rise, but public employee costs do not change. By contrast, in defined contribution plans, an employer is obligated to make only a specific amount of contributions in the years that employees work. If investment returns are less than desired, the employer is not obligated to contribute anything more to a defined contribution plan. In defined contribution plans, therefore, employees and retirees generally bear all investment risk.

Proposal

Hybrid Plan for Future Public Employees. The Governor proposes that future public employees be enrolled in hybrid retirement plans. Details of the Governor’s idea are somewhat unclear, but he appears to envision employer and employee contributions to both defined benefit and defined contribution plans, as well as employees’ participation in Social Security (except, presumably, for future teachers and most public safety workers). The Governor seems to propose that the state Department of Finance be empowered to design such hybrid plans based on the following general goals:

- Non–Public Safety Employees. The hybrid plans would be based on employer and employee contribution schedules that would aim to produce a 75 percent replacement ratio for non–public safety employees assuming a 35–year public–sector career. The defined benefit pension plan would be responsible for about one–third of the 75 percent replacement income, the defined contribution plan another one–third, and Social Security the final one–third. For teachers and others not in Social Security, the defined benefit would be responsible for two–thirds of the 75 percent replacement income, with defined contribution plans responsible for the remaining one–third.

- Public Safety Employees. The hybrid plans would be based on employer and employee contribution schedules that would aim to produce a 75 percent replacement ratio for public safety employees assuming a 30–year public–sector career. For those employees not in Social Security, as with teachers, the defined benefit would be responsible for two–thirds of the 75 percent replacement income, with defined contribution plans responsible for the remaining one–third.

Benefit “Cap” for High–Income Public Employees. The Governor’s plan also references a cap on the defined benefit portion of the proposed hybrid plan requirement so that public employers do not face high costs for pension benefits of future high–income public workers. Such a cap might affect future public workers like the small, but growing, portion of current public pensioners who receive pension benefit payments exceeding $100,000 per year. The Governor’s plan provides no detail on how such a cap might work.

LAO Comments

Excellent Starting Point for Discussion. We previously have recommended that the Legislature take steps to ensure that future public workers are enrolled in hybrid plans. This can reduce substantially the risk of future unfunded pension liabilities by shifting a significant portion of the risk that public employers now bear for defined benefit plans to defined contribution plans instead. In defined contribution plans, employers bear no risk for future investment returns, and unfunded liabilities for these plans are not possible.

Major Policy Shift Would Make Public Employees More Like Private–Sector Workers. We believe that moving future public employees to hybrid plans would address a key policy concern relating to the current public employee pension system—the growing disparity between public–sector and private–sector employee retirement benefits and security. Moving to a hybrid plan would bring public employees’ retirement packages closer in line with those of their private–sector counterparts and serve to discourage future public employees from retiring as early as their predecessors do today. Finally, we believe that the Governor’s goal to have career public workers have a retirement income equal to about 75 percent of their career income makes sense and is in line with studies indicating the replacement ratio to preserve an employee’s lifestyle in retirement. (This is particularly true if the employee has supplemental employer–subsidized health coverage during retirement.)

We discuss our concerns related to the proposed cap for high–income public workers later in this report. Also, as discussed immediately below, there appear to be discrepancies between this part of the Governor’s proposal and his proposal to increase future public employees’ retirement ages.

Increased Retirement Ages for Future Employees

Background

In California, public employee pension formulas often are referenced in a type of shorthand—such as 2 percent at 55—that implies there is a single “retirement age” (in this case, 55). Actually, current California public employees in this group are eligible to begin receiving service retirement benefits at age 50—although with a lower benefit factor. In most cases, however, these employees work longer so that they can increase their retirement benefits through a higher factor. For example, in the 2 percent at 55 group for non–public safety state employees, employees can “max” out their factor at 2.5 percent at age 63. Even this, however, is not the “maximum retirement age,” as workers generally can continue to increase their benefits by working more years beyond age 63.

As shown in Figure 3, in the state’s three largest public employee retirement systems, the average state or local employee retired at about age 60 as of 2009–10. Public safety employees tend to retire a few years earlier. Moreover, due to recent changes in benefits for newly hired state employees and some local employees, average retirement ages in many of the groups shown in the figure will tend to increase somewhat in the coming decades under current policies, even if the Governor’s proposal is not adopted.

Figure 3

Average Retirement Ages for Selected Public Employee Groups in 2009–10

|

|

Age

|

|

California Public Employees’ Retirement Systema

|

|

|

California Highway Patrol Officers

|

53

|

|

Local public safety officers

|

55

|

|

State correctional officers and firefighters

|

60

|

|

Other state and local employeesb

|

60–61

|

|

California State Teachers’ Retirement Systema

|

|

|

School district and community college teachers

|

62

|

|

University of California Retirement Plan

|

|

|

Professional and support staff members

|

59

|

|

Academic faculty

|

63

|

It is also worth noting that many retirees receiving benefits from public retirement systems also work in other jobs during their lifetime, including private–sector positions. These partial career employees can receive relatively small pension benefits. Calculations of the average monthly or annual pension benefits paid by public pension systems often include these partial–career workers. If such workers were excluded from these calculations, average monthly benefits paid would be higher than shown by public pension systems in many cases, and average retirement ages shown in Figure 3 also could be affected.

Proposal

Work to a Later Age Would Be Required for Full Benefits. The Governor’s plan seemingly requires that all future public employees work to a later age to qualify for full retirement benefits. The Governor proposes that non–public safety pensions for future employees target a retirement age at 67 (the current Social Security retirement age for those workers). Future public safety workers would target a lower retirement age “commensurate with the ability of those employees to perform their jobs in a way that protects public safety.” (As discussed below, it is not clear exactly what the Governor means in this part of his proposal. Presumably, this would be addressed when the administration provides additional details about its plan.)

The Governor points out that these changes would reduce significantly both pension and retiree health costs for governments. In particular, employees would have fewer, if any, years between retirement and reaching the age of Medicare eligibility. After the age of Medicare eligibility, a substantial portion of public–sector retiree health care costs shift to the federal government’s Medicare program.

LAO Comments

Increasing Average Retirement Ages Is Essential. Given increased longevity, we believe it is appropriate to increase retirement ages for future public employees. Failing to do so would risk a growing long–term fiscal burden for governments supporting pension programs, since future increases in longevity would then produce proportionate or greater increases in pension and retiree health benefit costs. There is no single right age to target, especially for public safety workers. It will be important, however, for the Legislature to set a specific policy for public safety workers rather than the nebulous one that the Governor’s proposal seems to suggest.

The Legislature also may wish to consider whether the current age of minimum service retirement eligibility for most public employees—age 50—should be increased.

Possible Conflict With Other Parts of the Proposal. We are uncertain how the Governor’s retirement age proposal squares with other aspects of his proposal. Specifically, if future non–public safety workers are to work until age 67 to receive full retirement benefits, this suggests that a public employee entering government service right out of college or high school might have to work for over 40 years to receive such benefits. Yet, the Governor’s hybrid proposal envisions a 75 percent replacement ratio for such workers after only 35 years of government service. Accordingly, it is not clear how the Governor’s plan intends to mesh the key variables of the expected length of a working career, replacement ratios, and retirement age.

Limit Spiking for Future Employees

Background

Benefits for Many Still Based on Single Highest Year of Salary. Many current public employees are entitled to receive pension benefits based on their single highest year of government salary. As we discussed in our 2005 P&I report on public pensions, this single–year formula for determining pension benefits is very rare among state and local employees in the United States; in fact, it is a feature of public pensions in California and almost nowhere else.

In recent years, the state and some local governments have moved to change the single–year formula for newly hired employees by instead calculating their pension benefits based on their highest average annual compensation over a three–year period. This discourages pension “spiking,” which includes efforts of employees to change jobs or receive increased pay during their final one or two years of employment that increases their eventual pension benefit by a large amount.

Proposal

Require “Three–Year Final Compensation” for Future Employees. The Governor proposes that all future public employees have their defined benefit pensions calculated based on their highest average annual compensation over a three–year period.

LAO Comments

Broad Consensus for This Change. We previously have recommended the Governor’s proposal. There seems to be broad public consensus for this change, and it would be a small step to increase public confidence in public employee pension systems. We caution, however, that, despite frequent headlines concerning pension spiking, this change probably would result in substantial pension cost savings for a relatively small group of future employees. It is not likely to result in significant cost savings for governments.

Base Benefits on Regular, Recurring Pay

Background

Current Rules Can Result in Some Abuses. There are some instances when public pensions reportedly are increased as a result of employees receiving additional pay from bonuses, unused vacation time, overtime, and other “perks.” Many pension systems, however, already prohibit such compensation items from being used to calculate final compensation for purposes of pension benefits.

Proposal

Establish Uniform Rule to Prevent Abuses. The Governor proposes that all public defined benefit pension systems prohibit these types of compensation items from being included in final compensation used to determine annual pension benefits for future employees.

LAO Comment

Broad Consensus for This Change. We recommend passage of this proposal. Such a change, if rigorously enforced by all pension systems and employers, should help increase public confidence in California’s state and local pension systems. This change, however, might lower costs for only a small percentage of future employees. This part of the proposal seems unlikely, therefore, to produce substantial pension cost savings for governments.

Limit Post–Retirement Employment for All Employees

Background

Currently, Individuals Can Return to Public Sector After Retirement. California governments often rely on “retired annuitants” and retired workers from other public employers to work part–time or full–time. Such retired workers can bring considerable expertise to public agencies. Some pension systems, such as CalPERS, limit retired members to working for only 960 hours per year for certain state and local agencies, and these retired annuitants’ services do not result in their accruing any additional retirement benefits. In other cases, an individual may be able to retire from one retirement system and work for an employer in a different public retirement system, while accruing additional retirement credit in that second system. (This latter scenario probably occurs very infrequently.)

Proposal

Extending CalPERS Limits to All Public Employers. The Governor proposes to limit all current and future employees in their post–retirement work for California governments. Specifically, the Governor wants to limit all current and future employees from retiring from public service and working more than 960 hours per year for a public employer—essentially extending the CalPERS post–retirement employment rules to all public employees. The Governor also would prohibit all retired employees from earning retirement benefits for service on public boards and commissions.

LAO Comments

Important to Strike the Right Balance With These Changes. While the Governor’s proposal in this area lacks some detail, it seems reasonable to us, in that it seems to strike the right balance on limitations on postretirement employment. In many cases, public employers can benefit from the expertise of retired workers while saving money—paying them little or nothing in the way of benefits. (A full–time worker, by contrast, typically would receive substantial benefits that would add to his or her personnel costs.) We observe, however, that it will be very difficult for pension systems across the state to enforce this provision if it is indeed applied to limit a public retiree’s work for any state or local employer in the state. For example, it might be difficult for the Los Angeles County Employees Retirement Association to identify a newly hired, middle–aged employee who happened to be a retiree of, say, the UCRP.

Limit Felons’ Receipt of Pension Benefits

Proposal

Forfeit of Pension and Related Benefits. The Governor proposes that public officials and employees convicted of a felony in carrying out official duties, in seeking elected or appointed office, or in connection with obtaining salary or pension benefits forfeit their pension and related benefits.

LAO Comments

Proposal Raises Various Issues. The Legislature may want to explore certain issues regarding this proposal. For instance, it is unclear to us whether this type of change would be constitutional in all cases as applied to current and past public employees. For future public employees, however, the state clearly may impose such a forfeiture requirement. In addition, would such forfeiture be prospective only, or would repayments of some or all previously paid pensions to retired felons be required? What if the felon cannot repay such costs?

Prohibit Retroactive Pension Increases

Background

Contributor to Recent Unfunded Liability Increases. In recent years, many California governments have retroactively applied pension benefit increases to some or all employees’ prior years of service. This can mean, for instance, that an employee who worked nearly all of his career earning benefits based on one pension benefit formula (for example, 2.5 percent at 55) was able to complete that career on a higher pension benefit formula (such as 3 percent at 50). When the change is applied retroactively, that worker may earn a pension benefit equal to 3 percent of his final compensation multiplied by his years of service, even though both he and his employer made contributions throughout his working life based on a 2.5 percent benefit factor. Accordingly, when that worker retires, the government is left with an unfunded liability to address in the coming decades.

Proposal

Ban Retroactive Benefit Increases. The Governor proposes to ban future retroactive pension increases for all public employees. Prior retroactive increases are constitutionally protected and generally cannot be changed.

LAO Comment

An Important Change to Make. History suggests that, particularly at times when pension systems temporarily appear overfunded, retroactive benefit increases can be very tempting for public employers and employees—essentially a kind of “free money” to provide to career public servants. Yet, as the Governor correctly points out, such free money generally will end up costing taxpayers, since pension systems rarely remain overfunded for long and unfunded liabilities almost always result from such retroactive benefit grants. Moreover, retroactive grants often will play no role—or even a counterproductive role—in encouraging employee recruitment and retention. New recruits certainly do not benefit from a higher pension benefit applied to prior years of service. Valued career employees often will be incentivized to retire earlier than they otherwise would due to their ability to receive a higher retirement benefit.

Given the history of public employers in this area and the limited instances in which such retroactive benefit grants would be of real value to public employers, we recommend that the Legislature approve this element of the Governor’s proposal.

Prohibit Pension Holidays

Background

A Relic of Past Boom Years in the Financial Markets. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, the “tech bubble” years in the stock market when public pension systems temporarily reported that they were overfunded, many public employers substantially reduced or entirely eliminated their annual pension contributions and, in some cases, public employee contributions were reduced as well. This is the key reason why state pension contributions to CalPERS were so low in some years of the late 1990s, as shown in Figures 1 and 2. State contributions to CalSTRS’ defined benefit program also were reduced during this period, contributing to CalSTRS’ recent funding problems.

Proposal

Limit Ability of Employers to Suspend Contributions. The Governor’s proposal would “prohibit all employers from suspending employer and/or employee contributions (related to both current and future public employees) necessary to fund annual pension costs.”

LAO Comments

Getting Details Right Is the Key. We agree that employers should be sharply limited in their ability to suspend regular employer or employee contributions. History tells us that such periods of overfunding often are fleeting and may be based on temporary stock market bubbles.

In 2008, the Public Employee Post–Employment Benefits Commission (PEBC) appointed by the prior Governor and legislative leaders agreed to a recommendation to restrict pension funding holidays. The PEBC recommended that employers be permitted to implement contribution holidays only based on the amortization of their surplus over a 30–year period. In other words, contributions could fall to zero only in instances when the surplus is so great it can fund 30 full years of normal costs. We suggest that the Legislature use PEBC’s recommendation as a starting point in the discussion in this area.

Prohibit Airtime Purchases

Background

Widely Available, but Very Difficult to Price. Pursuant to state legislation or other law, CalPERS and many other public pension systems have allowed certain eligible public employees to buy “airtime,” which is additional retirement service credit for years not actually worked. For example, a state employee can add five years of service credit—and, accordingly, increased retirement benefits later—by paying a significant sum of money to CalPERS. In theory, the public employee pays for the entire cost of this additional defined benefit pension credit. In practice, however, airtime is nearly impossible to price accurately and, in the past, often has been priced far too low, which has resulted in the creation of a small portion of existing unfunded pension liabilities.

Proposal

Ban Airtime Purchases. The Governor proposes banning airtime purchases for current and future employees. Prior airtime purchases presumably would remain valid.

LAO Comments

Agree With Governor. In light of the difficulty of pricing airtime accurately and its tendency to result in the creation of unfunded liabilities and higher taxpayer costs, we recommend that the Legislature approve this part of the Governor’s plan.

Change Composition of Pension Boards

Background

Proposition 162 Limits Ability to Change Pension Boards. California’s public retirement systems are governed by boards that generally consist of appointees of public officials and public employees and retirees elected by system members (or, in some cases, appointed by public officials). In 1992, Proposition 162—sponsored by public employee groups in response to efforts of Governor Wilson and the Legislature to alter financial arrangements relating to CalPERS—placed in the Constitution a limitation on the Legislature’s ability to change the composition of state and local public retirement systems. Accordingly, the Legislature generally may not alter the number, terms, method of selection, or method of removal of state or local pension board members. To do so, a vote of the electors of the jurisdiction affected by the pension board is required. For CalPERS, for example, a statewide vote is required to change board membership.

Proposal