Background

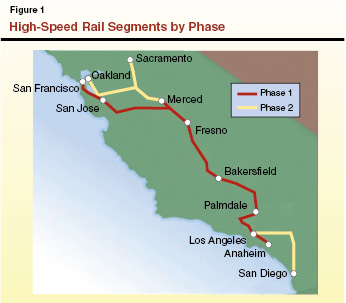

The HSRA is responsible for planning and constructing an intercity high–speed train that is fully integrated with the state’s existing mass transportation network. The train system would link the state’s major population centers, including Sacramento, the San Francisco Bay Area, the Central Valley, Los Angeles, the Inland Empire, Orange County, and San Diego (as shown in Figure 1). The California High–Speed Rail Act of 1996 (Chapter 796, Statutes of 1996 [SB 1420, Kopp]) established HSRA as an independent authority consisting of a nine–member board appointed by the Legislature and Governor. In addition, the HSRA has an executive director, appointed by the board, and a staff of less than 20. Most work is carried out by consultants under contracts with HSRA.

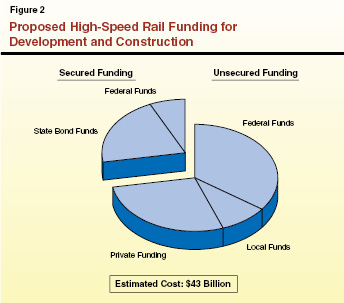

In November 2008, voters approved Proposition 1A, which allows the state to sell $9 billion in general obligation bonds to partially fund the development and construction of the high–speed rail system. In addition, the state has received roughly $3 billion from the federal government for the cost of construction. The remaining funding for the system’s construction and operation is anticipated to come from the federal and local governments, as well as the private sector. The HSRA’s most recent cost estimate for completion of the first phase of the project as defined by Proposition 1A, from San Francisco to Los Angeles and Anaheim via the Central Valley, is roughly $43 billion. The HSRA recently approved plans to begin construction in fall 2012 on a portion of the system through the Central Valley that spans from north of Fresno to north of Bakersfield. It is estimated this portion will cost roughly $5.5 billion. The Governor’s January budget plan proposes to allocate $192 million for HSRA activities for 2011–12.

A Number of Problems Threaten Successful Development of High–Speed Rail

California’s high–speed rail project is quickly picking up pace, with plans to spend billions of dollars in the next few years. A number of serious problems, however, threaten the successful development of the high–speed rail project. They include:

- The availability of the funding necessary for the new system is highly uncertain.

- Federal project requirements limit the state’s options for development of the system.

- The HSRA’s structure and staffing levels are inadequate for its changing role.

- The Legislature lacks good information for decision making.

Availability of the Funding Necessary for New System Highly Uncertain

The 2009–10 Budget Act required HSRA to submit to the Legislature a revised business plan by December 15, 2009, as well as a review of this plan by our office. Figure 2 shows the project’s anticipated funding sources as described in the business plan, as well as what portion of this funding has been secured as of April 2011. In our review of the business plan in early 2010 we concluded that its funding assumptions are optimistic and that it is unclear how the state will be able to secure the necessary funding to complete the project. Specifically, we found that the business plan includes unrealistic assumptions about the receipt of federal funds to build the project, no discussion of the challenges of additional General Fund debt–service costs, as well as a lack of identified sources for the other funding assumed in the business plan to complete a high–speed rail system. In addition, the plan indicated the potential need for a state operating subsidy, which would be contrary to explicit provisions in Proposition 1A. We discuss these potential problems in more detail below.

Federal Funding Assumptions Appear Unrealistic. The HSRA’s latest business plan assumes the state will receive $17 billion to $19 billion from the federal government for construction of the high–speed rail system. To date, HSRA has secured roughly $3.6 billion in federal funding for development of the project. Of that, roughly $3 billion is dedicated to the construction of the system; $400 million was given to the developers of the San Francisco Transbay Transit Center, one of the planned high–speed rail stations; and nearly $200 million will be used by HSRA for project–wide preliminary engineering and environmental clearance work. The HSRA indicates that without additional significant federal support beyond that provided to date, the project cannot be completed. Given the federal government’s current financial situation and the current focus in Washington on reducing federal spending, it is uncertain if any further funding for the high–speed rail program will become available. In contrast to the interstate highway system, which was constructed with the dedication of funding from the federal excise tax on gasoline, federal funding for high–speed rail is not supported by a dedicated revenue stream and therefore must compete with other annual federal funding priorities.

State Would Incur Major Additional Debt Service Costs. The 2009 business plan assumes that $9 billion in state funding for the project will come from the sale of general obligation bonds approved by voters in Proposition 1A. The debt service payments on general obligation bonds are typically paid for from the state’s General Fund. We estimate that, should the state sell all of the $9 billion in voter–approved high–speed rail bonds, the state’s total principal and interest costs for repaying the debt would be $18 billion to $20 billion. This would require annual debt service payments of roughly $1 billion for the next two decades. Due to the dire condition of the state’s General Fund, adding such costs for debt service in the near future means that the Legislature would have to consider reducing costs for other state programs or increasing revenues to offset these costs.

Basis for Assuming Other Funding Contributions Is Unclear. The 2009 business plan assumes that $14 billion to $17 billion of the project’s construction costs would be paid with funds from local agencies and private partners. The bulk of this funding is expected to come from the private sector when the state enters into some form of public–private partnership (PPP), or contractual agreement with private partners to complete and operate the high–speed rail system. The amount of funding available from these sources will be highly dependent on the business model chosen for the system. For example, if HSRA ultimately decides to share the tracks built for the new train system with commuter rail operators in certain metropolitan areas, those local agencies might have an incentive to contribute local revenues to the construction of the project because the improvements would ultimately benefit the operations of local systems. This would not be the case, however, if the business model chosen by HSRA did not share the tracks and instead maintained the rail line purely dedicated to its own trains. The HSRA could choose not to share tracks for a variety of reasons, such as safety concerns or a determination that it needed all the rail capacity for its own service. The current HSRA business plan does not provide any details about the business model and how, as it now assumes, it will attract substantial funding from local agencies and private partners to build the system.

Potential Need for Operating Subsidies Could Lead to General Fund Cost Pressures. The HSRA’s business plan indicates that the initial costs of operating a high–speed rail system may exceed $1 billion per year. However, Proposition 1A requires HSRA to submit a funding plan which certifies that, once complete, the planned high–speed rail passenger service will not require a local, state, or federal operating subsidy. This certification must occur prior to requesting any appropriation of the $9 billion in state bond funds for capital costs. Notwithstanding the provisions of Proposition 1A, the state could discover during development or after construction has been completed that the system needs such a subsidy in order to operate. If the train does not attract the number of riders projected, for example, operating revenues would likely be less than expected. The train line would then need funding from some other source to operate. Absent the identification of another source of operating funds for the train system, this situation could place an additional financial pressure on the state’s General Fund.

Federal Project Requirements Limit State’s Options

As noted earlier, the state so far has received a commitment of $3.6 billion of federal funds for the development of the state’s high–speed rail system. The FRA, which is responsible for administration of federal railroad assistance and rail safety programs, has attached specific requirements to the roughly $3 billion portion of that funding which was designated specifically for construction of the high–speed rail line. Below, we discuss some of the challenges for the project created by these federal restrictions.

Federal Funds Deadlines and Requirements Led to Risky Decisions. A large portion of the federal funding dedicated so far to California’s high–speed rail project came with strict deadlines that may be difficult for the state to meet. Moreover, federal authorities are also requiring that nearly all of these funds be spent building an initial section of the train line in the Central Valley that, by itself, would have insufficient ridership and revenues to stand on its own.

About $2.3 billion of the $3 billion in federal funds awarded to the state for construction of the rail system come from the 2009 federal economic stimulus legislation, titled the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). The FRA initially required that the state obtain environmental clearance of the segment of the project financed with ARRA funds by September 2011. (In this report we use the terms segment, corridor, and route interchangeably without regard to potential technical distinctions in state law.) In addition, the FRA required that the ARRA funds be expended by 2017 and indicated that the state must forfeit any ARRA funds that are unspent by that time. (The remaining $715 million of federal funding awarded to California for high–speed rail purposes is not subject to the same deadlines as the ARRA funds.)

In November 2010, the FRA announced that it will require all federal funds for construction awarded to the state as of that time be spent on a segment of the rail line planned for the state’s Central Valley. According to FRA, this decision was driven by the deadlines discussed above. Specifically, FRA concluded that the segments most likely able to meet the 2017 deadline for expenditure of ARRA monies were in the Central Valley in part because, at the time, there was little public opposition to this portion of the project which potentially could slow the project down.

Largely as a result of these federal deadlines and requirements, HSRA decided in December 2010 to begin the construction of the statewide system within the Central Valley. This decision by HSRA, however, represents a big gamble that additional monies will eventually become available from the federal government or other sources to connect the Central Valley line to other major urban areas of California. The authority acknowledges that operation of the Central Valley segment by itself is infeasible because the potential ridership of a high–speed rail line within that segment alone would be insufficient to operate the system without a substantial subsidy.

It now appears, however, that this risky decision by HSRA was based on faulty assumptions. After HSRA approved the Central Valley section, the FRA dropped the September 2011 deadline for environmental clearance work. Moreover, the assumption that construction of the Central Valley segment could move quickly because of a lack of public opposition has already proved to be unfounded. Significant local opposition has arisen, relating largely to concerns over how the alignment of the tracks could affect agricultural operations, which has cast into doubt whether the 2017 deadline for expending all the ARRA funds can be met.

HSRA Structure and Staffing Levels Inadequate for Its Changing Role

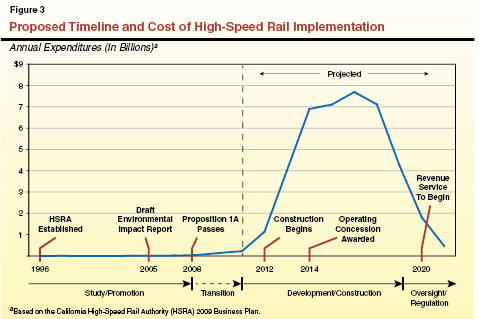

The HSRA was initially created in 1996 to direct the development and implementation of a California high–speed rail line that is fully integrated with the state’s existing intercity rail and bus network. As described earlier, HSRA consists of a nine–member board (five members appointed by the Governor, two appointed by the Senate Rules Committee, and two by the Speaker of the Assembly), an executive director appointed by the board, and staff to support the project. Voter approval of Proposition 1A in 2008 shifted its role from development of the system to one of overseeing the construction of what experts often refer to as a “mega–project.” The HSRA is now responsible for delivering one of the country’s largest transportation infrastructure projects. The timeline in Figure 3 shows how HSRA’s role and annual funding levels have changed since 1996 and are proposed to significantly change in the future. As the figure indicates, annual funding levels for the project have been relatively low compared to the large increases in expenditures anticipated in the near future when the project begins construction.

However, our analysis indicates that HSRA’s operational structure and staffing practices have not kept pace with the project’s changing demands. Below, we describe how these problems could hinder the effective management and oversight of the high–speed rail project.

Structure of HSRA Board Is Problematic. To date, the Legislature’s major role in the development of the high–speed rail project is the appropriation of funding each year. State law otherwise grants the HSRA board considerable authority over the project, including the award of multi–billion dollar contracts and concessions as well as the choice (within voter–approved parameters) as to when and where the train will be constructed and eventually operated.

The considerable autonomy granted to the HSRA board under current state law, however, does not ensure that the board keeps the overall best interests of the state in mind as it makes critical decisions about the project. Upon their appointment to the panel, board members receive four–year terms and are not subject to direction by the executive branch. Nor are gubernatorial appointees to the board subject to a legislative confirmation process. This relative lack of accountability to either the executive or legislative branches creates a risk that the board will pursue its primary mission—construction of the statewide high–speed rail system—without sufficient regard to other state considerations, such as state fiscal concerns.

Arguably, some board decisions, such as its selection of the Central Valley segment as the starting place for construction of the system, have already demonstrated such weaknesses in the structure of the board. While that decision at the urging of federal authorities did advance the primary mission of the board to complete the high–speed rail project, it raises concerns that the board did not sufficiently consider the fiscal risks to the state if additional monies to complete construction of the line into a more urban area do not materialize. Moreover, HSRA pledged at the time to provide a dollar–for–dollar match of ARRA funds even though no match was required, committing more state bond dollars and debt–service payments than necessary to secure the federal funding.

Another concern is that, under the current statute that created HSRA, appointees to the board are not required to have the specific expertise that would be helpful in the management of a construction project of this magnitude, such as a background in engineering or construction management, infrastructure finance, or rail system management.

Heavy Reliance on Consultants May Increase Risks to State. Before the passage of Proposition 1A, the HSRA maintained a staff of roughly seven positions and conducted oversight of a relatively small number of consultants developing the general approach for building the high–speed rail system. After the voters approved the bond funding for the project, the number of consultants working on its implementation increased significantly. At the time we prepared this analysis, the HSRA operated with a staff of approximately 19 filled positions and a team of consultants that is the equivalent of 604 positions. While HSRA is authorized to have a staff of 40, vacancies have persisted largely because of hiring freezes imposed in recent years in response to the state’s severe fiscal difficulties. If all of the authorized state positions were filled, the ratio of state employees to consultants would be 1 to 15. As things stand, with only 19 state workers actually in place, the ratio is 1 state employee for every 33 consultants.

Representatives of the HSRA contend that successful oversight of this type of project is not dependent on the number of state workers available to oversee its consultants but rather on the ability of staff to manage certain necessary functions, such as contract management and oversight, financial and operational plan development, and risk management. According to HSRA staff, similar mega–projects worldwide have succeeded with between 60 and 80 staff fulfilling these critical functions. Recent state reviews, however, challenge the authority’s contentions. For instance, in 2010, the State Auditor found that although HSRA generally followed state requirements for awarding contracts, its processes for monitoring the performance and accountability of its contractors are inadequate. In addition, the auditor found that HSRA paid at least $6.9 million in invoices from its consultants without verifying that the work reflected on the invoices was actually performed. A review by the state Office of the Inspector General included similar findings and raised additional concerns about HSRA’s ability to oversee the consultants on the project. Based on these findings, it is questionable whether the current number of state employees at HSRA can effectively manage such a large team of consultants.

The Legislature Lacks Good Information for Decision Making

In general, the availability of good data leads to better decision making. However, our analysis indicates that the Legislature suffers from a lack of good information that is needed to make decisions about the appropriation of funds for the high–speed rail project. Given the very large size of this project, its extended construction timeline, and the novelty of this type of project for California, it is reasonable that some key project decisions must be based on the best available analysis and assumptions rather than hard numbers. For example, it is unlikely that any ridership or revenue forecast is going to give a definitive, reliable answer to whether the high–speed rail system can be successfully completed and operated without significant state support. However, in other cases, HSRA has not shared critical information with the Legislature. For example, while HSRA has provided an estimate of the cost of the part of the line between San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Anaheim, it has not provided its estimate of the total cost of all phases of the project that go beyond this route. Below, we discuss some of the information gaps that are making it more difficult for the Legislature to make decisions about the project.

Project Lacks a Detailed Business Plan. Our review indicates that the Legislature lacks a detailed business plan to guide multi–billion–dollar decisions it must make about high–speed rail projects. Such a plan would include, at a minimum, updated cost estimates, anticipated funding amounts and sources adjusted to reflect current political and economic realities, a range of forecasted ridership and revenue estimates, a proposed business model, and a discussion of risks the project may encounter. The existing business plan was prepared in 2009 and, while it included all of the information that was statutorily required at the time, it lacks adequate detail for the Legislature to use to make major funding decisions. The lack of detail prompted the Legislature to adopt budget bill language in 2010 requiring HSRA to provide this kind of information. However, this language was later vetoed from the budget bill by the Governor. The HSRA has committed to providing an updated business plan in October 2011. At the time this report was prepared, however, the Legislature had received little of the information it needs to decide what activities it should fund in the 2011–12 budget plan and beyond.

Cost Estimates Outdated and Likely Understated. Based on our analysis, the high–speed rail project is likely to cost much more than the $43 billion originally estimated by HSRA for the first phase from San Francisco to Anaheim. That estimate was prepared in 2009 based on very preliminary information concerning which alignments would be selected for the track and what the design of the system would look like.

For example, based on the state’s agreement with FRA, the cost of the initial construction segment between Fresno and Bakersfield alone is now estimated to be $4.5 billion, which is 57 percent greater than was assumed in the original plan. As shown in Figure 4, the costs for program management, final design, and construction are each significantly higher for the 100–mile Central Valley segment now planned for construction than compared to the full 120–mile segment originally proposed from Fresno to Bakersfield. (This initial construction segment estimate also does not include the cost of completing the line into Bakersfield, nor the $200 million station planned for that city.)

Figure 4

Comparison of Costs for Fresno to Bakersfield Segment

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2009 Estimate

|

|

2011 Estimate

|

|

Fresno toBakersfield

|

|

Initial Construction Segment

|

|

Estimated Length of Segment in Miles

|

120

|

|

100a

|

|

Project Component

|

|

|

|

|

Program Management

|

$361

|

|

$667

|

|

Real property acquisition and early work

|

603

|

|

583

|

|

Final design and design–build construction contracts

|

1,879

|

|

2,912b

|

|

Project reserves and unallocated contingency

|

—c

|

|

309

|

|

Total

|

$2,843

|

|

$4,471

|

|

Increase in Project Costs

|

|

|

57%

|

If the cost of building the entire Phase 1 system were to grow as much as the revised HSRA estimate for the 100–mile segment discussed above, construction would cost about $67 billion. This extrapolation of costs, however, is based on the cost increase for a relatively straight–forward and uncomplicated segment of the proposed rail line. It is possible that some of the more urban segments could be even more significantly underestimated. The uncertainty surrounding the eventual cost of the system represents a significant challenge to the Legislature’s ability to make sound decisions about appropriation for the project.

Governor’s 2011–12 Budget Would Move Project Ahead

The Governor’s proposed budget for HSRA generally follows the schedule outlined in the most recent high–speed rail business plan. This proposal would fund HSRA at a level that is comparable to the level of funding it is receiving in the current year. The proposal is significant because it moves the project ahead as planned. As a result, the Legislature may be asked to appropriate billions of dollars in 2012–13.

The budget plan includes $192 million to fund HSRA activities ($90 million in federal funds and $102 million in Proposition 1A bond funds). Almost all of the funding ($185 million) is for work that will be performed by consultants. This includes contracts for program management, financial consulting, public outreach, and work on the development of the high–speed rail system. In March 2011, the Legislature passed (but has not yet sent to the Governor) SB 69 (Leno), a state budget bill which would appropriate the $7 million in funding for HSRA’s state administrative costs. This is an increase of roughly $1 million from the current year’s administrative budget, primarily due to increased intergovernmental contract costs (as described below).

Budget Proposes Increased Funding for State Legal and Administrative Services. State law requires that all state agencies use the Department of Justice (DOJ) as legal counsel, unless specifically exempted by law. As the project moves forward, HSRA is increasingly in need of legal support for activities such as the project’s environmental process, land acquisition, and contracting for construction. Because of this, the budget includes a request for additional funds for legal work performed by DOJ. In addition, HSRA contracts with the Department of General Services (DGS) for accounting, administrative, and personnel services. While it is common for small departments to have such contracts, larger departments such as Caltrans often have in–house, specialized staff to accomplish this work.

Major Budgetary Decisions Are Looming. The Legislature will face some major decisions about the appropriation of billions of dollars in state and federal funds beginning in 2012–13. In that fiscal year, HSRA plans to enter into a number of large design–build construction contracts which, in contrast to traditional construction procurement processes, award the design and construction of a project to a single entity. Some of the design–build contracts could be worth more than a billion dollars. The Legislature will likely be asked to appropriate the state and federal funding for entire, multiyear contracts in 2012–13 so that HSRA can award these types of contracts.

This situation poses a dilemma for the Legislature. Because these huge appropriations are not needed now, they are not formally before the Legislature as part of the 2011–12 budget plan for HSRA. On the other hand, unless directed otherwise, HSRA will proceed during the interim with extensive development activities based on its decisions about the project, such as its choice of the initial Central Valley segment for construction. If the Legislature has concerns about the path the high–speed rail project is on, it will diminish its opportunity to have meaningful input over such issues as the location of the first construction segment if it waits until 2012–13 to do so.

The Legislature Faces Challenging Choices

Given the significant challenges to the high–speed rail project, and the large and looming budgetary decisions, the Legislature faces some near–term challenging choices. Should the state continue with the project as planned, slow it down dramatically and attempt to address some of the problems that threaten its success, or stop the project completely? At the root of this decision is whether the significant potential benefits of moving forward with the project outweigh the significant risks to the state. Unfortunately, at this time, there is little reliable information available to inform this decision.

Project Could Have Some Positive Outcomes. The proposed high–speed rail system could have some positive fiscal benefits. For example, HSRA estimates that this project would alleviate the need to build 3,000 new lane–miles of freeway, and 5 airport runways and 90 new departure gates—at a cost of nearly $100 billion—that would otherwise be necessary to accommodate intrastate travel by 2030. This is because the state’s population is projected to grow steadily for decades and significant investment in transportation infrastructure is expected to be needed to accommodate travelers between Northern and Southern California. In theory, if those travelers choose the high–speed rail system instead of other modes, the project could reduce the state’s overall infrastructure costs.

In addition, beginning construction of the project could have some positive effects on the state’s economy. For example, the infusion of federal funds and potentially other private funds from outside the state, such as international partners who might invest in the project, would benefit the overall economy at least in the short run. Some work, such as the construction of rail cars, could be performed by California firms.

However, it is unclear how much of the funding allocated for high–speed rail would be spent in California. Because California has never before built this mode of transportation, some out–of–state or international firms may have the critical expertise needed by the state to successfully build such a large–scale and complex rail system. For example, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 97 percent of all operators of the track–laying equipment that HSRA indicates it would use for the project reside in other states. To the extent that the state procures the services of firms from outside of California to develop and construct the rail line, as well as to obtain rolling stock and equipment for the system, the overall economic benefit to the state could be diminished.

Finally, some have argued that investing in high–speed rail infrastructure instead of other modes of transportation could lead to improved environmental outcomes, such as better air quality. This is because the proposed system will be electrically powered and not require fossil fuels the way most automobiles and aircraft currently do. However, other studies have suggested that the project may not realize such improved environmental outcomes, especially if levels of ridership were low to moderate.

If Project Moves Forward, Changes Needed to Increase Likelihood of Its Success. Given the threats to the project that we described earlier, we have concluded that the Legislature should only proceed with the project if two significant changes in direction occur. First, the Legislature needs more time and the flexibility to make critical decisions relating to the project, even though this would require modifications to the federal restrictions that have been imposed on the project. Second, given the magnitude of the state’s investment in the project, significant improvements are needed in the way both day–to–day and longer–term strategic decisions to manage the project are made. We have concluded that the current governance structure for the project is no longer appropriate and is too weak to ensure that this mega–project is coordinated and managed effectively. These changes in governance need to be made soon, in our view, because HSRA has already begun the process to move toward the award of multi–billion dollar construction contracts for the project. We describe in more detail below the specific changes in direction that we have concluded are necessary.

State Needs More Time and Flexibility to Develop Project

As mentioned earlier, the FRA has imposed some impractical restrictions on the development of California’s proposed high–speed rail system. If the state were granted flexibility from the federal government to spend federal funding on a more reasonable timeline, and where it will have the most benefit, the project’s chances of success could be significantly improved in a way that might also better accomplish some of the federal program’s stated goals in funding the project.

Flexibility Regarding Federal Restrictions Is Needed. Based on our analysis, we recommend that the state seek substantial additional flexibility regarding the federal restrictions on the project. First, the state needs more time than federal authorities are currently allowing to critically evaluate which segment or segments should be constructed first. Second, the state should be allowed to choose the segments to be constructed. Among the critical factors that we believe the state should consider in choosing a segment for construction are: (1) whether a passenger rail system on a selected segment could generate the ridership and revenues to be financially successful and operate without a state subsidy; (2) how much of the segment could be completed with the funds now available; and (3) the potential benefits from building a particular segment, including its potential impacts on traffic congestion and air quality. The nearby text box describes some alternative segments within Phase 1 that our analysis indicates should be carefully evaluated because of their potential to provide greater overall benefits to the state than the Central Valley route.

Whatever routes were chosen as a result of this additional evaluation, gaining the additional federal flexibility needed to take more time on this critical decision could pay other dividends. For example, it might better enable the state to properly prepare environmental documents necessary for the project to move forward and decrease the likelihood of delay from litigation. Such project delays can endanger the state’s ability to meet deadlines as well as increase the overall cost of the project.

Alternative Segments Could Provide More Benefit to the State

For several reasons discussed earlier, there is a significant risk to the state that the statewide high–speed rail system envisioned in Proposition 1A will never be fully completed. It is possible that only a segment or two of the system will ultimately be constructed. The High–Speed Rail Authority has chosen to begin construction of the system on a 123–mile segment from near Fresno to Bakersfield. If this is the only portion of the system built, the state would realize some service improvements for the San Joaquin intercity rail corridor, such as shorter trip times and better on–time service. This intercity rail service currently runs six trains daily in each direction. However, based on our analysis, other segments could provide greater benefit to the state’s overall transportation system even if the rest of the high–speed rail system were not completed. Below, we describe three segments that warrant consideration as alternatives to the Central Valley line.

- Los Angeles–Anaheim. This highly travelled corridor includes commuter, freight, and intercity rail traffic, which could benefit greatly from corridor improvements along the alignment shared with the proposed high–speed rail system. Fifty passenger trains run daily through this corridor, at times sharing tracks with roughly 75 freight trains. In addition, grade separations that could be built as part of a high–speed rail project would improve the flow of auto traffic along the corridor because vehicles would no longer have to stop and wait for passing rail. Finally, to the extent improved passenger rail service in this corridor led to increased ridership, it could reduce pressure on other transportation modes and decrease the need for infrastructure projects that expand the capacity of the roads.

- San Francisco–San Jose. Similar to Los Angeles–Anaheim, capital projects in this heavily congested corridor could improve both rail and auto traffic. This segment currently hosts 86 commuter trains daily, and freight trains use it at night.

- San Jose–Merced. The state provides intercity rail service from Sacramento to Merced (and on to Bakersfield), and a separate rail service between Sacramento and San Jose. If the state chose the segment between San Jose and Merced for a high–speed rail project, the state would essentially “close the loop” and enable a significant increase in passenger rail mobility between the Central Valley and the Bay Area. This benefit from high–speed rail construction would result even if high–speed trains ultimately were never operated on the system. A recent report prepared by a Bay Area transportation commission projects that the number of commuters traveling daily from the Central Valley to the Bay Area will double by 2030, adding 60,000 commuters a day.

|

More Flexibility Could Help the State Meet Federal Goals. Putting a hold on the Central Valley segment, and asking the federal government for more flexibility to examine this and other alternatives more carefully, carries the inherent risk that the state could lose some or all of the committed federal funding. However, we believe it is likely that the federal government would ultimately work with the state to grant more flexibility, for the following reasons.

- California Offers a True High–Speed Rail Option. The federal administration has prioritized dedicated high–speed rail projects, or projects that result in trains running at speeds of over 110 mph and generally do not share tracks with freight rail. California’s project is currently the only federally funded high–speed rail system in the country. (Some federally funded “high–speed rail” projects in other states would incrementally improve existing passenger rail services, but none of these are dedicated high–speed rail projects.) For this reason, it is in both FRA’s and the state’s best interests that the project succeed.

- Federal Authorities Are Already Showing Flexibility. The FRA has already demonstrated a willingness to adjust timelines in order to accommodate the state. For example, the state was recently granted more time to complete the environmental clearance on the initial construction section to give the contractors an opportunity to identify ways to reduce the cost of construction. In addition, in February 2011, the President issued a memorandum to all federal agencies directing them to provide more administrative flexibility to state and local governments in order to improve outcomes in federally supported programs at a lower cost.

- Federal Authorities Could Get a Greater Payoff From Their Investment. Granting the state more flexibility from federal deadlines and restrictions could ultimately lead to greater achievement of the federal program’s own policy goals. For example, in addition to ARRA’s goals of creating jobs and stimulating economic recovery, the federal law was intended to improve the nation’s energy independence, improve environmental quality, and make regional transportation systems more efficient. A better decision on where to start construction of California’s high–speed rail system could lead to a greater payoff in each of these areas.

How Greater Federal Flexibility Could Be Achieved. A federal extension of the timeline for expending these funds could be accomplished in a couple of ways. Current FRA regulations require that the state spend federal funds and its state matching funds at the same time. Under one approach, the state could request that FRA adjust its regulations to allow the state to first spend the federal funds it has received and, after those funds have been fully spent, to spend the amount of state funds committed under the federal program. The amount of state funding committed to the project would not change—only the timing of when the funds are spent. This approach seems reasonable given that the ARRA funds required no match and therefore are being spent by other recipients in this way. Such a change would enable the state to spend the ARRA funds twice as quickly once construction begins and make the 2017 expenditure deadline more easily achievable.

In addition, FRA indicates that it has the administrative discretion to remove the current requirement that its grant award to California be used for construction of the high–speed rail line beginning in the Central Valley. Changing this requirement opens the possibility to begin construction anywhere on the proposed line between San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Anaheim. Such a change would give the Legislature more latitude to consider the state’s interests when determining the initial construction segment of the high–speed rail system.

More Effective Governance Could Improve Likelihood of Project Success

If the Legislature chooses to move forward with the high–speed rail project, it could also address issues we have identified pertaining to the governance of the project—how both day–to–day and longer–term strategic decisions about the project are made and implemented. Our analysis indicates that a more effective governance structure could help to remedy some of the serious problems faced by the high–speed rail project and improve its chances for success. The concept of good governance is discussed in the nearby textbox.

Characteristics of Good Governance

Governance refers to the process of decision making and how decisions are implemented. Public governance involves the management and control of public resources and the delivery of programs and services. According to numerous studies of national and international organizational management, good governance principles generally include:

- Participation—the involvement of key stakeholders.

- Accountability—holding decision makers responsible for what they say and do.

- Transparency—clarity and openness in the decision–making process.

- Responsiveness—addressing the priorities and expectations of the public.

- Efficiency—the extent to which resources are used without waste, delay, or negatively impacting future generations.

Effective governance structures are more likely to make decisions and take actions that define expectations, grant power, and ensure that performance meets expectations. Such an approach can better ensure the successful completion of large projects within budget and on time. |

Our analysis found no one best way to structure an organization to improve governance, and that there is no particular organizational structure that can guarantee effective governance. Management experts hold the view that an organization’s structure should ideally be adjusted on a regular basis to reflect its current goals and the particular circumstances it faces, both of which can change dramatically, sometimes even within a few years’ time. Ultimately, an appropriate organizational structure allows for the best decisions to be made that lead to the best outcomes.

Our analysis indicates that the current organizational structure for California’s high–speed rail project does not meet these tests. For example, in our view, the current decision making process for the project does not ensure that this statewide effort, funded heavily with state bond funding, is developed primarily with the state’s best policy and fiscal interests in mind. In the sections that follow, we explore several issues related to the way decisions are made about the project. In particular, we discuss (1) whether the project should be treated as a state project or a business enterprise and (2) options for modifying HSRA’s organizational structure to improve the governance of the project.

Is This Phase of High–Speed Rail Development a State Project or Business Enterprise?

A first step toward improving the governance structure for the high–speed rail system is to consider the state’s relationship to and responsibilities regarding the project. In other words, is the project at this phase of development principally a state effort, or should the state minimize its involvement and allow the project to be developed and administered like a business enterprise?

Because of the magnitude of this project and the length of time it is likely to take to develop and construct the project, the answer to this question will depend largely on which phase the project is in. Figure 3 shows the overall timeline and the different phases of implementation anticipated for the high–speed rail system. (The timeline for the project, which is based on HSRA’s business plan, differs from that of a traditional PPP. We describe these differences in more detail in the nearby text box) As we noted earlier in this analysis, the original role of HSRA was to explore the feasibility of creating a state high–speed rail system and to do some initial planning for the system. The state’s role in the project is already changing dramatically as it begins the development and construction phase, and would change again during its subsequent operation and maintenance. As a result, it is reasonable that the state’s governance approach to the project should similarly evolve over time. We discuss these concepts in more detail below.

How the Phases of This Project Will Differ From Traditional PPPs

In all public–private partnerships (PPP), there is a point in the project’s development when the public sector’s involvement diminishes and the private partners take significant control. Generally, for transportation–related PPPs, this happens after the initial design, environmental clearance, and right–of–way acquisition occur, but before construction is fully under way. This is because it is often best for the public entity to bear the early risks to the project—such as right–of–way acquisition—because the public sector can use such tools as eminent domain to accomplish the task that are not available to the private sector. Typically, control of a PPP project is ceded to the private sector for later phases of a project’s development in order to potentially lower the project’s overall cost and to reduce the risks that the sponsoring public agency would otherwise bear for its development.

California’s high–speed rail project will differ from this typical model because of the enormous cost and risk involved with the project. While a consortium of large firms can generally bear the risk of a project costing up to a few billion dollars, the High–Speed Rail Authority’s (HSRA’s) latest business plan indicates that this project will conservatively require $10 billion from the private sector to complete. According to HSRA, the high amount of risks and costs mean that the state will need to follow a different project development model. For this project, HSRA expects to spend most or all the public funding first and oversee the dozens of large construction contracts. Then, toward the completion of the project, HSRA expects that a private partner or consortium will provide funding to finish the system and procure rail cars, likely with a long–term operations and maintenance contract to recover its costs over time. |

High–Speed Rail Is More Similar to Large State Projects During Development and Construction

Figure 5 summarizes some of the key characteristics of what we refer to in this report as state projects—meaning, projects in which state government plays the primary role in the day–to–day as well as long–term strategic decision making. The figure also summarizes the characteristics of what we refer to in this analysis as business enterprises—activities for which the state cedes significant administrative responsibility and control to a more autonomous state agency or even a private partner.

Figure 5

Characteristics of State Projects and Business Enterprises

|

Characteristic

|

StateProject

|

BusinessEnterprise

|

|

Funded by General Fund dollars

|

X

|

|

|

Funded by large amount of federal funds

|

X

|

|

|

Financially self–supporting

|

|

X

|

|

Similar work done by private entities

|

|

X

|

|

Competes with private market to deliver services

|

|

X

|

|

Requires coordination with other levels of government

|

X

|

|

|

Contractors perform most work

|

X

|

X

|

|

Use of eminent domain

|

X

|

|

|

Oversight of public funds

|

X

|

|

|

Completion of environmental studies and mitigation

|

X

|

|

|

High level of accountability to the public

|

X

|

|

|

Takes some risks to realize higher returns

|

|

X

|

Our analysis found that, during the upcoming development and construction phases, the high–speed rail project more closely resembles a state project. For example, state bond funds (with debt service costs paid for by the General Fund) will finance a significant portion of the project’s costs. These monies are typically managed by the state rather than private or quasi–private entities. In addition, the success of the completed system will largely depend on its integration with local transit, the state’s intercity rail, and the state highway systems. The high–speed rail project is also more like a state project in that, in order to complete its work, the implementing organization must engage in a number of activities traditionally accomplished by government rather than private enterprise. These activities include, for example, the use of eminent domain to acquire large swaths of property.

All of these factors suggest the need for a more “hands–on” involvement by the state at this phase in both day–to–day administrative and strategic decisions. At this stage of implementation, the high–speed rail project in many ways resembles the construction of the state highway system. The development of the state’s highways was assigned to Caltrans, a department which, like most state departments and agencies, is subject to strong oversight and controls by both the executive branch and the Legislature, such as through the annual state budget process.

In contrast, California Housing Finance Agency (CalHFA), which takes the lead on a number of the state’s affordable housing finance programs, has operated with considerably more autonomy under the model of a business enterprise. CalHFA is financially self–supporting, meaning that it does not require public funds from either the state or federal government to operate. It does work similar to private entities, and in some ways competes with the private sector to provide home–mortgage loans. At this time in its development, the high–speed rail project shares none of these qualities with CalHFA.

Options for Improving Governance of the High–Speed Rail Project

As discussed above, our analysis suggests that an autonomous state operation does not seem to be a very good fit with the critical set of tasks now required to move forward with a high–speed rail project. This is of concern for several reasons. First, the current governance structure for HSRA grants its commission more independence and autonomous decision–making ability than we believe is appropriate for this phase of the project’s development. Second, because of the significant impacts on the state’s transportation network, we believe the project should be integrated into the state’s current transportation planning structure. Finally, preserving the current organization of HSRA could lead to redundancies within state government and inefficient allocation of resources. Below, we present three options for changing the governance of what we view as fundamentally a state project rather than a business enterprise.

High–Speed Rail Project Could Be Shifted to Caltrans

One option to address the problems identified above would be to shift some or all of the responsibility for overseeing the construction of the high–speed rail line to a more conventionally governed state agency or department. Caltrans may be the best choice, in our view, because this project is consistent with Caltrans’ mission of delivering transportation construction projects and improving mobility throughout the state. Caltrans has decades of experience in delivering large transportation infrastructure projects and has a large complement of engineering staff in place. Because Caltrans is already subject to close oversight by both the executive branch and the Legislature, moving the project from HSRA to the department could improve accountability for critical project decisions. Such a change could also somewhat reduce the need for external contractors and provide the state with greater staff resources to ensure appropriate oversight of the sizeable number of contracts that would be required for the construction of such a project.

While we believe there are merits to shifting the project to Caltrans, there are reasons to be concerned about such a shift. For instance, transportation experts within and outside state government have expressed concerns about Caltrans’ ability to effectively implement this project, citing the department’s longstanding focus on highways and lack of expertise in working with private partners on PPPs. In addition, our office has in recent years found some significant management problems in Caltrans. Finally, some experts suggest that the project should be viewed not as a state project but as a PPP under which the state would cede a significant level of control to private partners. (As we indicate in a previous text box, however, this project is not expected to follow the traditional PPP schedule and would be the state’s responsibility for many years before the private partners become involved.)

Notwithstanding these issues, the benefits of moving the responsibility of this transportation project to Caltrans may outweigh these potential concerns. The Legislature would have to consider carefully exactly what operational changes might be needed for Caltrans to successfully manage development and construction of a new high–speed rail system. Below we further discuss the advantages of moving the project to Caltrans.

Caltrans Staff Could Perform Many Project Tasks. While much of the more specialized project work would remain the responsibility of contractors, some of the proposed contracted work could be moved to Caltrans. Under this alternative, HSRA’s executive director and staff would be shifted to Caltrans to oversee the remaining contract activities, as well as to develop plans for future partnerships to help finance and operate the rail system. Examples of work that could be turned over to Caltrans staff include:

- Negotiating and Overseeing Large Contracts. Caltrans contracts with engineering and construction firms for the completion of major transportation projects. For example, the department has entered into multiple, large contracts ranging from hundreds of millions of dollars to $1.75 billion for the construction of the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge.

- Acquiring Property for Transportation Rights of Way. Caltrans has roughly 500 staff in Sacramento and in district offices that acquire property for the state’s transportation projects. This staff is already well–trained in the specific actions necessary to acquire rights of way for transportation projects, including assessment of property values, relocation of utilities, and the successful negotiation of land purchases. For instance, the HSRA is planning to adopt Caltrans’ manual for right–of–way acquisition as its own because of the department’s experience and in–depth knowledge of the process.

- Developing Public Support for Transportation Projects. The department maintains a public information office with over 60 staff, as well as hundreds of staff in its planning division. Many of these staff regularly attend local public meetings concerning state projects and by doing so work to gain public support for the department’s proposals. In addition, the department has established relationships with local agencies, regions, and other stakeholders which could greatly benefit the high–speed rail project. The HSRA is currently contracting with Caltrans to conduct inter–governmental relations with many of the entities potentially affected by the project.

- Providing Legal Support for Project Development and Delivery. Caltrans has about 280 attorneys, many of whom are experienced in handling legal issues regarding the environmental review process for transportation projects. In addition, Caltrans’ staff handle legal issues relating to the acquisition of property for rights of way and transportation–related contracting issues.

- Interacting With State and Federal Administrative Processes and the Legislature. Caltrans has significant experience dealing with the typical state administrative processes such as working with the state’s Department of Personnel Administration to hire staff and DGS to award contracts. Caltrans also has extensive experience working with the federal Department of Transportation, including meeting reporting requirements and effectively communicating the state’s needs. Finally, Caltrans has a good understanding of the state and federal budget and legislative processes.

Caltrans’ Capital Outlay Process May Be Better–Suited to High–Speed Rail. Currently, the high–speed rail project is subject to a review and approval process administered by the state Public Works Board (PWB). The main purpose of this process is to ensure that capital outlay projects are developed in compliance with the Legislature’s intent when it appropriated funding for them. This process is generally used for non–transportation projects such as the construction of office buildings and courthouses or the acquisition of open space land.

However, certain departments, such as Caltrans, are not subject to the PWB process. Traditional transportation projects use a different capital outlay process which we find is better–suited to the high–speed rail project. Caltrans’ process takes into account various challenges unique to transportation projects, such as the timing of design, environmental clearance, and right–of–way acquisition. Because Caltrans is so familiar with delivering transportation projects, shifting this project development and construction work to the department could increase the odds that the high–speed rail project will be successful.

Developing Project Within Caltrans May Foster Integration Into Transportation System. If the high–speed rail project were moved to Caltrans, the project that is ultimately built is likely to be better integrated into the state’s transportation system. Currently, decision making about the state’s transportation system is not integrated and it is unclear to what extent Caltrans and HSRA are working together to address the state’s overall transportation needs.

For instance, we have been advised by Caltrans that HSRA contractors have only recently begun engaging the department in discussions about the added traffic volumes around some proposed train stations. In some cases, Caltrans staff have formally commented in writing through the environmental process that the additional traffic at the proposed stations could be considerable. For example, the most recent business plan projects nearly 13,000 boardings daily at the Palmdale station alone. In theory, close coordination of the train project with improvements to mass transit systems operated by other state or local transportation agencies could head off potential traffic problems. Without a robust transit system, however, many riders would likely rely on their cars to reach this station. Thus, this potentially significant increase in traffic to and from this station should be included in state and local transportation planning long before the station opens. This kind of coordination is critical to the success of the project.

Some Operational Changes Within Caltrans Would Be Needed. While Caltrans has developed and overseen the construction of the state highway system, it has no experience with high–speed rail projects. In addition, our office has raised concerns in the past about aspects of the operations of Caltrans and, in particular, its staffing levels for its division responsible for overseeing the development and construction of capital projects. Therefore, the Legislature should carefully consider what operational changes would be needed within Caltrans if it were assigned this task. The ultimate strategy should be to take advantage of the department’s experience and expertise while maintaining the current organization’s access to particular project delivery tools necessary for successful completion of a high–speed rail project.

One way to accomplish this would be to create a separate division within Caltrans, led by a high–level deputy director who would have overall responsibility to manage the construction project. The current HSRA executive director could transition to this role to minimize any disruption to the project. In addition, all of the current HSRA staff and position authority could likewise shift to be the initial staff of this new Caltrans division. In this way, the transfer of the project to Caltrans could be accomplished in a way that was not unduly disruptive to the project. Finally, any such shift of the project to Caltrans should be accompanied by the enactment of statutory changes that would allow Caltrans to apply certain project delivery tools specifically for the high–speed rail project that are authorized in state law. These would include the unlimited ability HSRA now has to enter into contracts with private entities for the design, construction, and operation of the system. Caltrans, in contrast, is currently limited in its ability to hire contractors and can only complete 10 percent of its construction management and oversight work using consultants. This proposed change would not affect Caltrans’ current limitations for development of other projects, but would apply only to the work to complete the high–speed rail project.

Given the complexity of the high–speed rail project, Caltrans should also be given the flexibility now afforded to HSRA to use design–build contracts for its development and construction. Also, if the project were to be shifted to Caltrans, we believe certain positions within this new Caltrans division should be exempted from state civil service requirements to help the state attract individuals from the private sector with the experience to develop this project, negotiate multi–billion dollar contracts, and oversee the system’s implementation.

HSRA Could Become a New State Department

Another option to better integrate the high–speed rail project into the traditional state governance structure is to create a new state department for this purpose within the Business, Transportation and Housing (BTH) Agency. This new department could focus exclusively on the development of the high–speed train system or, in the alternative, be combined with other state rail programs, such as the intercity rail system that is now overseen by Caltrans. A recent study by the California Research Bureau found that a new department combining state rail duties would likely be beneficial, but could also increase state costs.

A new department, whether focused on high–speed rail or encompassing all state rail responsibilities, theoretically could have a number of advantages over the current organization. The BTH Agency could better coordinate the activities of this new department with other state transportation efforts, including those of Caltrans. In addition, the creation of such a department could give rail system development issues more visibility with the public and give rail projects more prominence in policy and budget decisions. Pending legislation, AB 145 (Galgiani), as amended on March 16, 2011, would establish a new Department of High–Speed Trains under the BTH Agency to focus exclusively on the high–speed rail project. The new department proposed in the legislation would be modeled after Caltrans, but would continue to take policy direction from the HSRA board and the director would still work at the board’s pleasure.

There are some disadvantages to this approach. Creating a new department would likely increase state administrative costs and result in the duplication of activities already being performed by other state departments. For example, the new department would likely require the establishment of a new division for the acquisition of rights of way, duplicating the work of a Caltrans division already doing the same type of work. Similarly, the new department would need to duplicate the expertise that Caltrans already has in negotiating and entering into various types of innovative contracts with the private sector. In addition, a new department may be less able to integrate the project into the state’s transportation system because it would lack Caltrans’ familiarity with transportation planning processes.

HSRA Board Could Be Eliminated or Modified

As described earlier, HSRA consists of a nine–member board with considerable power to direct the development and implementation of the high–speed rail system. Along with the other changes described above, the Legislature may wish to consider the elimination or modification of this largely autonomous board that now controls the administration of the high–speed rail project.

Legislature Could Eliminate the Board. As discussed earlier, the current governance structure for development of the high–speed rail system does not require that the board keep the overall interests of the state in mind, including state fiscal concerns, as it makes critical decisions about the project. The current lack of accountability of the board to either the Legislature or the executive branch, in our view, creates a serious risk that it will continue to make decisions about the train route and finances without paying sufficient regard to the future consequences for the state. In addition, we are concerned that such a board—particularly one lacking requirements for members who have the specific technical expertise to manage such a massive construction mega–project—is not appropriate for the next phase of this work.

For these reasons, the Legislature may wish to consider eliminating the board and ceding both day–to–day and strategic long–term project management decisions either to Caltrans or to a new state department. Either choice, in our view, would likely be more accountable for its decisions to the executive branch and the Legislature. In either case, the California Transportation Commission (CTC), which works closely with Caltrans, could play an important role. The commission already is assigned the responsibility of advising and assisting the Secretary of the BTH Agency and the Legislature in formulating and evaluating state policies and plans for California’s transportation programs. The important role that the current board serves in obtaining public input about the project could also be accomplished by changing the statutory mission of the CTC so that it would hear high–speed rail issues in the same way that it currently hears public concerns about state highway projects.

Legislature Could Modify the Board’s Existing Role and Structure. If the Legislature chose to retain the board, state law could be changed so that it would operate in an advisory rather than a decision making role. For example, Florida’s Statewide Passenger Rail Commission was created within the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) to monitor the efficiency, productivity, and management of all publicly funded passenger rail systems and to advise FDOT and the legislature on policies and strategies relating to state–owned passenger rail systems. This new advisory board could be combined with the already statutorily established peer review group, tasked with reviewing the project’s planning, engineering, and financing plans and reporting to the Legislature, or it could remain a separate board to monitor the management of the project and provide general advice about the system to the Legislature and the administration.

Regardless of whether the panel retains its authority as a decision–making body or becomes an advisory panel, the composition of the board could be changed to require that at least certain members have specified technical expertise, such as in construction management, infrastructure finance, or the operation of rail systems. Appointments to a number of state boards, such as the California Energy Commission and the Air Resources Board, similarly require that its members have specific areas of experience or knowledge. Pending legislation, SB 517 (Lowenthal), as amended on April 25, 2011, would vacate the membership of the current board and require new appointments of members with various changes, including requiring specific expertise of some members.

Another potential change to the membership of the board would be to include some representation for local elected officials or transit agencies in areas along the route of the high–speed system. This could help to ensure that the potential impacts of the design and alignment of the high–speed rail system in those communities are fully considered and that the high–speed rail line is better integrated with local mass transit and other transportation systems. This could be accomplished in a number of ways, such as giving each affected county a board seat, or creating a joint–powers authority (JPA) similar to the Capitol Corridor JPA, which oversees the Northern California intercity rail system between the Sacramento region and the Bay Area.

LAO Recommendations: Increasing the Odds That High–Speed Rail Will Succeed

The proposed high–speed rail system offers some significant potential benefits to California’s transportation system—including a possible reduction in overall transportation spending for highway and airport expansions, and improvements in air quality and the environment. As we have also noted in this report, however, a number of concerns—ranging from the availability of and federal conditions on the funding for the project, lack of good information for decision making, and problems with the way project decisions are governed—pose threats to its successful completion.

Thus, major budgetary and other challenges related to this project loom in the near term. The Legislature will likely be asked to appropriate billions of dollars for the high–speed rail project in 2012–13. The deadlines and conditions attached to federal funding will make it increasingly difficult over time for the Legislature to make any changes it may wish to consider to the proposed configuration or prioritization of segments of the rail system, or to the organization (HSRA) now charged under state law with the responsibility of building it. Some of these factors have already led to debatable decisions about the future of the project, such as HSRA’s commitment to start building a segment in the Central Valley.

Accordingly, if upon weighing these factors the Legislature chooses to go forward with the project, we believe there are some key steps that it should take now to improve the likelihood of its successful development. In general, our recommended strategy involves (1) seeking greater flexibility from federal authorities on the project deadlines and the choice of a rail segment involving use of federal grant funds and (2) improving the governance and oversight of the project. The recommendations below represent the first steps that the state could take so that, in the long run, the efforts undertaken to develop and implement the high–speed rail project can provide the best outcomes for the state as a whole.

Seek Flexibility From Federal Restrictions and Evaluate Construction of Alternative Segments

In our view, the Governor’s budget proposal to continue to fund activities that would move the high–speed rail project forward as now proposed is asking the Legislature to take a huge leap of faith given the threats to the success of the project. For example, the proposed start to the project in the Central Valley represents a significant gamble that additional unidentified funding to complete adjacent segments of the project onward to urban areas will be forthcoming. The proposed approach creates a serious risk that, after billions of state bond funds have been spent and significant future debt–service costs have been incurred, the state will be left with a rail segment unconnected to major urban areas that has little if any chance of generating the ridership to operate without a significant state subsidy. In our view, this is inconsistent with the parameters for the project set forth by the voters in Proposition 1A, who explicitly directed that any future rail system be capable of operating without a state subsidy.

In addition, we have concluded that the Legislature needs more reasonable deadlines and flexibility from the federal government so that it can conduct a full evaluation of the Central Valley segment and alternative starting points for the system. The granting of this flexibility from the federal government would also give the Legislature time to consider how the governance of the project could be improved, given that the current organizational structure is unlikely to be up to the task of development and construction of the new rail system. In our view, the state has a potent argument that the granting of such flexibility by federal authorities would not only protect the interests of the state, but would ultimately lead to greater achievement of the federal program’s own policy goals to improve the nation’s energy independence, improve environmental quality, and make regional transportation systems more efficient.

Therefore, we recommend the Legislature take a series of steps to ensure that the state prioritizes spending of state funding for segments that have the best chance of actually being constructed and operated.

First, we recommend that the Legislature reject HSRA’s 2011–12 budget request for $185 million in funding for consultants to perform project management, public outreach, and other work to develop the project. We recommend that the Legislature appropriate only the $7 million in funding for HSRA state administration provided for in the pending budget bill, SB 69. This would provide the resources needed by HSRA to complete the tasks we describe below that we believe are warranted to move the project forward in a way which is more likely to be successful.

Second, we recommend that the Legislature adopt budget bill language directing HSRA to renegotiate the terms of the federal funding awarded to the state by the FRA. The language would specifically request that FRA permit the state to first spend the federal funds it has received and, after those funds have been fully spent, to spend the state bond funds that it has committed. As noted earlier, such a change would enable the state to spend the ARRA funds twice as quickly once construction begins and make the 2017 expenditure deadline more easily achievable. It would not change the state’s financial commitment to the segment supported with federal funds. The language would also request that FRA use its administrative discretion to remove the current requirement that its grant award to California be used only for construction of the high–speed rail line beginning in the Central Valley. This would open up the possibility for the state to begin construction of whatever segments on the proposed route between San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Anaheim that further evaluation shows makes the most sense. Further, we recommend the Legislature only proceed with the project if this flexibility from the federal government is forthcoming.

Third, we recommend that the Legislature adopt budget bill language requiring HSRA to reevaluate which segment or segments of the high–speed rail line should be constructed first. The language would specify that this reevaluation would proceed only if federal authorities granted the state the additional flexibility described above. The language would further direct that this study be completed by October 2011. In our view, this would provide sufficient time to complete such a study without creating delays that would make it impossible to meet the renegotiated federal deadlines. Because the HSRA may need additional resources to conduct this study, we further recommend the adoption of budget bill language authorizing the administration to seek an augmentation of its funding during 2011–12 for this purpose. The HSRA should be directed to identify the top two options, including its recommended option, for beginning construction based on criteria identified by the Legislature. The criteria for evaluating the best segment to build first should be included in the budget bill language and could include:

- The potential statewide benefits from building a particular segment, such as its impact on improving mobility and reducing congestion or improving environmental outcomes.

- How far along in the environmental review and design process the segment is and when construction could begin.

- Whether a passenger rail system on the selected segment could generate on its own ridership and revenues to be financially successful and operate without a subsidy.

- How much of a segment could be completed with available funds, and under the assumption that little or no additional funding might be forthcoming for the high–speed rail project.

Fourth, we recommend that the HSRA provide specific updated information about the project, such as updated cost estimates for the entire proposed rail line, to help the Legislature make more informed budgetary decisions about its investment in the high–speed rail system. We recommend that the Legislature require that this report be completed by HSRA by October 2011 in order to facilitate timely decision making about how the project could best move forward.

Lastly, we recommend that the Legislature adopt budget bill language authorizing the administration to seek an augmentation of HSRA’s budget that would allow it to proceed with the development of the segment approved by the Legislature based on the results of the evaluation described above.

This entire multistep process we have outlined above should take no more than a few months and therefore should not significantly affect the state’s ability to meet the federal deadlines for the project—assuming, of course, that federal authorities provide the state with the additional flexibility we believe is necessary for the project to move ahead with the best chance of success.

Structure High–Speed Rail Development as a State Project