Inmate Medical Program Under Federal Receivership. In 2006, after finding that California had failed to provide a constitutional level of medical care to its inmates, a federal court appointed a Receiver to take over the direct management and operation of the state's inmate medical care program from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). Since that time, the current and prior Receiver have taken a variety of actions that appear to have increased the quality of inmate medical care but also dramatically increased state expenditures. The increased cost of the inmate medical care program is partially attributable to several inefficiencies including its (1) inconsistent application of the utilization management system, (2) limited use of telemedicine, and (3) an inefficient management structure.

Court Takes Early Steps Towards Returning State Control. In January 2012, the federal court found that while some improvements to the program are still needed, substantial progress had been made towards achieving a constitutional level of medical care for prison inmates. The court ordered the administration, the Receiver, and attorneys representing prison inmates to jointly develop a plan for transitioning the responsibility for managing inmate medical care back to the state. Thus, the Legislature could soon be faced with critical decisions regarding how the state will effectively and efficiently carry out the responsibility of providing constitutionally adequate medical care for inmates following the termination of the Receivership by the federal court.

Keys to Providing Ongoing Constitutional and Cost–Effective Care. We find that in determining how to transition the responsibility for managing the program back to state control, the state should focus on two keys to long–term success: (1) creating independent oversight of the program, and (2) controlling inmate medical costs. Based on our review of California's inmate medical program and experiences in other states, we recommend that the Legislature create an independent board to provide oversight and evaluation of the inmate medical care program to ensure that the quality of care does not deteriorate over time. We further recommend that the state take steps to address current operational inefficiencies and establish a pilot project to contract for medical care services to bring state expenditures to a more sustainable level.

In 2006, after finding that California had failed to provide a constitutional level of medical care to its inmates, a federal court appointed a Receiver to take over the direct management and operation of the state's inmate medical care program from CDCR. Since that time, the current and prior Receiver have taken a variety of actions to revamp CDCR's medical program. Such actions have included increasing the range of salaries for various clinicians, revising the disciplinary process to facilitate the dismissal of incompetent physicians, and improving medical screening and classifications. On January 17, 2012, the federal court found that while some improvements to the program are still needed, substantial progress had been made towards achieving a constitutional level of medical care for prison inmates. The court ordered the administration, the Receiver, and attorneys representing prison inmates to jointly develop a plan for transitioning the responsibility for managing inmate medical care back to the state. Thus, the Legislature could soon be faced with critical decisions regarding how the state will effectively and efficiently carry out the responsibility of providing constitutionally adequate medical care for inmates following the eventual termination of the Receivership by the federal court.

In this report, we (1) provide a status report on the Receiver's actions, (2) describe how these actions have impacted inmate medical care spending and outcomes, (3) discuss the experiences of other states that have faced problems similar to California's in delivering inmate medical care, and (4) provide recommendations for delivering a constitutional level of inmate medical care in the most cost–effective manner as possible in the long run. In preparing this report, we spoke with correctional health care administrators in California and those in other states. In addition, we visited various medical facilities in different prisons operated by CDCR. We also reviewed the literature regarding correctional health care, and we drew upon data from numerous sources, including the Receiver's office and other states.

Inadequate Medical Care in Prisons Leads to Receivership

In April 2001, a class–action lawsuit, known as Plata v. Brown, was filed in federal court contending that the state violated the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution by providing inadequate medical care to prison inmates. The court found that the state's inmate medical care program was "broken beyond repair" and was so deficient that it resulted in the unnecessary suffering and death of inmates. Specifically, the court found, among other problems, that CDCR's medical care program was poorly managed; provided inadequate access to care for sick inmates; had deteriorating facilities and disorganized medical record systems; and lacked sufficient qualified physicians, nurses, and administrators to deliver medical services.

The state agreed in 2002 to take a series of actions to settle the case. On the basis of its ongoing review of the state's performance over subsequent years, the court found that CDCR had failed to comply with a series of court orders since 2002 to improve the inmate medical care program. The court concluded that, due to the lack of reliable access to quality medical care, an average of one inmate died every week and many more had been injured. Consequently, in February 2006, the Plata court appointed a Receiver to take over the direct management and operation of the state's inmate medical care program from CDCR. A nonprofit corporation was subsequently created, known as the California Prison Health Care Services (CPHCS), as a vehicle for operating and staffing the Receiver's operation. Almost two years later, the court appointed a new Receiver to continue and expand the efforts initiated by the first Receiver in bringing prison medical care up to federal constitutional standards. (As we discuss in the nearby box, a federal three–judge panel determined that overcrowding in the state's prison system was the primary cause of CDCR's inability to provide constitutionally adequate inmate health care and ordered a reduction in the inmate population.)

Federal Court Orders State to Reduce Prison Overcrowding

In November 2006, plaintiffs in the Plata v. Brown case joined plaintiffs in the Coleman v. Brown case (involving inmate mental health care) in filing motions for the courts to convene a three–judge panel pursuant to the U.S. Prison Litigation Reform Act. The plaintiffs argued that overcrowding in the state's prison system was preventing the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) from delivering constitutionally adequate health care to inmates. For example, it was alleged that overcrowding forced staff to restrict inmate movements for security purposes, preventing sick inmates from seeing health care staff in a timely manner. In August 2009, a three–judge panel ruled that in order for CDCR to provide constitutionally adequate health care, overcrowding would have to be reduced to no more than 137.5 percent of the designed capacity of the prison system within two years. (Design capacity generally refers to the number of beds that CDCR would operate if it housed only one inmate per cell and did not utilize spaces such as gyms and dayrooms for housing.) At the time of the three–judge panel ruling, the state prison system was operating at roughly 188 percent of design capacity—or about 39,000 inmates more than the limit established by the three–judge panel. The state appealed this decision to the U.S. Supreme Court. In May 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the three judge panel's ruling and gave the state until June 2013 to reduce the prison population to 137.5 percent of design capacity.

Receivers Implement Changes to Improve Care

First Receiver Restructured Inmate Medical Program. The first Receiver appointed by the federal court took a variety of actions to revamp CDCR's medical program. For example, he increased salaries for various clinicians, and implemented salary increases for nurses, pharmacists, and other clinicians. The Receiver hoped that these actions would reduce the number of vacant medical positions, which were around 20 percent for primary care providers. In addition, the Receiver revised the disciplinary process to facilitate the dismissal of incompetent physicians. He also changed the type of staff used to provide medical services and awarded a contract to a vendor to improve and manage pharmacy operations.

Current Receiver Implements "Turnaround Plan." In June 2008, the current Receiver submitted and the federal court approved his Turnaround Plan of Action designed to ensure that inmates receive constitutionally adequate medical care. Specifically, this plan identified various deficiencies in the existing inmate medical care program, as well as measurable goals to address these deficiencies. Some of the objectives outlined in the plan included reducing the number of inmate deaths, reducing the vacancies in certain clinical positions, and developing a medical information technology (IT) infrastructure. In order to implement his plan, the Receiver has made significant operational changes. For example, he established new policies related to emergency medical response, primary and chronic care delivery, and inmate medical screening and classifications. While the Receiver has completed many objectives included in the plan, he is still working on others (such as expanding and improving prison health care facilities). For example, the Receiver's proposed California Health Care Facility, a new prison medical facility to provide long–term care to seriously ill inmates, remains under construction. (The facility, which is scheduled to be fully occupied by December 13, 2013, will have a capacity of 1,722 beds.) In addition, the Receiver intends to make various medical facility upgrades to the state's 33 existing prisons. (We discuss the inmate health care construction plan in more detail in our recent report, The 2012–13 Budget: Refocusing CDCR After the 2011 Realignment.)

Court Orders State to Prepare for End of Receivership

On January 17, 2012, the Plata court found that while some improvements to the inmate medical care system are still needed, substantial progress had been made towards achieving a constitutional level of care for prison inmates. The court ordered all parties involved in the Plata case—including the administration, the Receiver, and attorneys representing prison inmates—to file a joint report to the court by April 30, 2012. Under the terms of the order, the report must include the parties' views on: (1) what criteria should be used to determine when it is appropriate to move from the Receivership to a less intrusive system of oversight; (2) whether the current Receiver should serve as a monitor once the Receivership ends, or, if not, how another monitor should be selected; (3) what criteria should be used to determine when the court should end its oversight and conclude the Plata case (including whether the state must first institutionalize some type of independent oversight of the inmate medical program); and (4) what system of governance should be used to manage the delivery of inmate medical care post–Receivership.

Receivership's End Would Restore State's Management Authority . . . Ending the Receivership would mean that the state would resume control of its inmate medical care program. Specifically, the state would regain the authority to make management decisions, provide oversight, and hold managers accountable for delivering inmate medical care cost–effectively. For example, the state would regain control over personnel decisions such as the hiring, termination, evaluation, and compensation for thousands of state employees currently managed by the Receiver. In addition, the state would regain authority to execute and monitor contracts worth hundreds of millions of dollars (such as for IT projects and specialty medical services). Currently, many of these contracts (as entered into by the Receiver) are not subject to state administrative regulations that generally apply to contracts entered into by other state agencies (such as reporting requirements for IT projects and competitive bidding requirements for procuring goods and services). This is because the Plata court waived such regulations in order to expedite certain contracts that were deemed critical to improving inmate medical care. While the court has not stipulated which state agency will assume control at the conclusion of the Receivership, it is likely that CDCR will do so because it managed the inmate medical program prior to the Receivership.

. . . But Court Will Likely Retain Some Level of Control in the Short Run. While the court order brings the end of the Receivership closer, it also implies that the court intends for there to be some period of continued court oversight following the conclusion of the Receivership. This period between the end of the Receivership and the conclusion of the Plata case could include the appointment of an expert monitor, commonly known as a special master. Special masters are similar to Receivers in that they are appointed by a federal court to monitor and oversee remedial efforts to bring an organization into constitutional compliance. Unlike Receivers, however, special masters lack executive authority and must rely on courts to order changes when they discover noncompliance with court orders. During the period following the Receivership, the court will expect the state to demonstrate that CDCR is able to sustain the improvements made under the Receivership, as well as make any additional improvements ordered by the courts. In addition, if a special master is appointed, the state will likely need to confer with this individual before making important operational and policy decisions related to inmate medical care.

Data Suggests Improvement in Inmate Medical Care

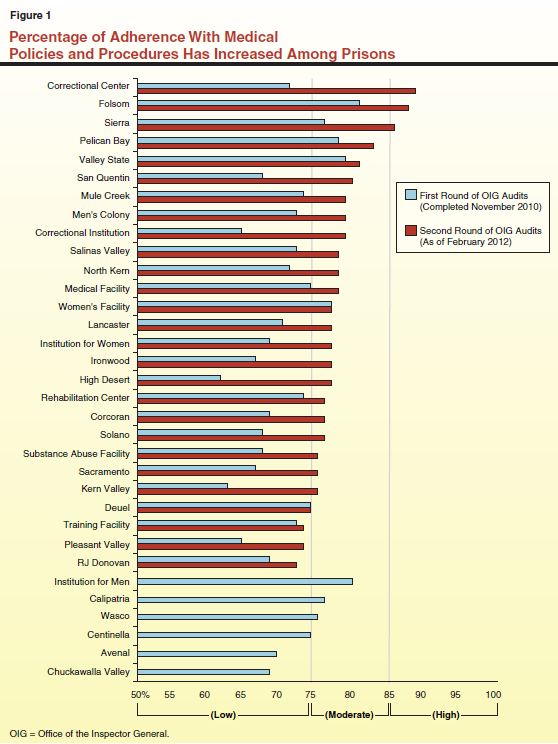

Office of Inspector General (OIG) Audits. In 2008, at the request of the Plata court, the OIG developed a statewide medical inspection program in order to periodically measure the extent to which the state's 33 adult prisons are adhering to the Receiver's medical policies and procedures and community standards of care. Specifically, the OIG, with the assistance of medical care professionals, designed an assessment tool to evaluate each prison's adherence to these policies and procedures. Based on this assessment, each prison receives a score on a scale from 0 to 100 in different areas of medical operations (such as medication management and chronic care). Prisons are categorized as "low" (below 75), "moderate" (between 75 and 85), or "high" (85 or higher) based on their level of adherence to specific medical policies, procedures, and standards. In 2010, after completing a first round of audits at each adult prison in the state, the OIG found that only 9 of the 33 prisons met the threshold of moderate adherence. As a result, the OIG concluded at that time that the Receiver had not yet fully implemented a statewide system of care that meets existing medical policies, procedures, and standards (including those developed by the Receiver).

Currently, the OIG is in the process of conducting a second round of audits which are intended to help determine whether the quality of care has improved over time since the first round of audits in 2010. At the time this report was prepared, second round audits have been completed at 26 of the 33 state prisons. According to OIG, 23 of these 26 prisons met the threshold of moderate adherence to medical policies and procedures, and three prisons met the threshold of high adherence. As shown in Figure 1, most prisons have improved significantly since the first audits were completed in 2010. Among the prisons that have had a second round audit, the average score increased from 71 percent to 79 percent.

While the above results are encouraging and a step in the right direction, the OIG audits do have some limitations. For example, a recent study of correctional health care measurements in California's prisons by RAND concluded that the OIG audits relied on many metrics that are not "explicit" (objective and quantifiable) and "evidence–based" (consistent with findings in the generally accepted medical literature). The RAND report also recommended that the state focus on using explicit and evidence–based measurements as the basis for developing a permanent performance measurement system. Thus, while the OIG's audits are an important indicator of improved care, they may be less conclusive than the type of robust and long–term performance measurement system recommended by RAND.

Health Care "Dashboard." The Receiver, in coordination with CDCR, recently implemented a health care dashboard, a visual display that summarizes key performance indicators, including a number of health outcome metrics that are explicit and evidence–based. The dashboard also specifies certain benchmarks or goals, based on data available from other health systems, against which inmate medical care outcomes can be compared. Since most of the indicators were only recently implemented, there currently is insufficient data to establish a clear trend in the quality of care being provided. Based on the limited data provided by the Receiver, it appears that the state's inmate medical program compares somewhat favorably with external benchmarks in some areas (such as asthma care) and compares unfavorably in others (such as colon cancer screening). Despite these mixed results, the dashboard represents a significant step towards establishing a framework for a robust performance measurement system that can be used to assess the quality of inmate medical care.

Spending on Inmate Medical Care Has Increased Dramatically

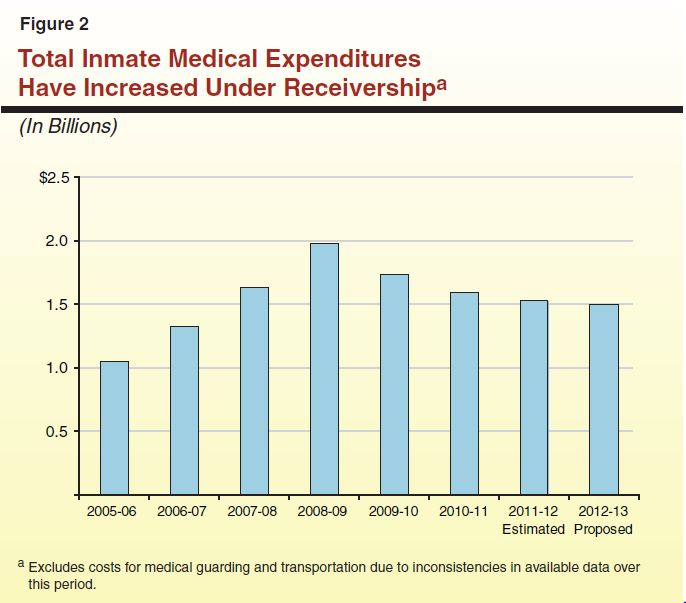

The various actions taken thus far by the Receiver to improve inmate medical care have dramatically increased state expenditures. Figure 2 shows expenditures for inmate medical care services and pharmaceuticals from 2005–06 through 2011–12 and as proposed in the Governor's budget for 2012–13. As the figure shows, spending on such services grew from $1.1 billion in 2005–06 (when the Receivership was established) to a peak of almost $2 billion in 2008–09, an average annual increase of 23 percent. This increase was in large part driven by greater usage of contract medical services, such as for specialty medical care provided outside prison, private ambulance transportation, and nursing and pharmacy registry usage. For example, contract medical costs more than doubled from $394 million in 2005–06 to $845 million in 2008–09. In addition, the hiring of over 1,000 additional medical staff and the increase in salaries for physicians and nurses during that period also drove up inmate medical care expenditures. Since 2008–09, however, inmate medical care expenditures have actually declined by 7 percent annually to a proposed level of about $1.5 billion in 2012–13. This decrease is largely attributable to a reduction in expenditures on contract medical, which are assumed to be $384 million in 2012–13. While the recent decline in total inmate medical care expenditures is encouraging, the proposed expenditure level for 2012–13 is still 42 percent higher than in 2005–06.

California also appears to be spending more per–inmate on medical care than any other state. A 2010 survey by Corrections Compendium (a research–based journal of the American Correctional Association) compiled per–inmate health care (medical, mental health, and dental care) expenditure data from 39 other states. According to the survey, these states spent an average of roughly $5,000 to provide comprehensive medical, mental health, and dental care to an individual inmate in 2009. Nearly all of the states surveyed spent in the range between $3,000 and $7,000. In that same year, California spent roughly $16,000 per inmate for all inmate health care services, of which, $11,000 was for medical care.

Several Inefficiencies Remain

Based on our review of California's current inmate medical care program, it is clear that the actions taken by both the former and current Receiver have improved the program and begun to address the concerns raised by the Plata court. However, it is unclear at this time whether these improvements are being provided in the most cost–effective manner, particularly in light of the fact that California spends significantly more on inmate medical care than other states with no evidence that the quality of care provided in California is higher. In particular, we find that the inmate medical care program in California continues to suffer from various inefficiencies. As we discuss below, the inmate medical care program has not taken full advantage of potential cost–containment measures related to utilization management and telemedicine, and it continues to suffer from an inefficient management structure.

Inconsistent Compliance With Utilization Management System. Utilization Management (UM) is the process of evaluating the appropriateness of health care services according to pre–established criteria and guidelines. Most managed health care organizations use UM to ensure that patients are consistently receiving the right type and level of care at the right time. Based on the symptoms a patient is presenting, a UM system relies on set guidelines for determining the types of medical services that would be reasonable, necessary, and effective to provide the patient. For example, the guidelines might indicate that a patient with symptoms that indicate a recent stroke (such as blurred vision and numbness) should be referred for an MRI scan.

Once UM guidelines are in place, one widely used practice in the medical industry is a process known as prospective review. During a prospective review, an independent UM specialist reviews a referral for an inmate to receive non–urgent specialty medical treatment that is unavailable in prison to determine whether it meets the UM guidelines. If the referral meets the guidelines, it is approved. If it does not, it is generally rejected. The UM specialist can, however, approve a referral that does not meet the guidelines by overriding the UM system if he or she finds that there are extenuating circumstances that make the UM guidelines inapplicable. In addition, the referring physician can seek to override the UM system by appealing to a higher level of review. While overrides are sometimes appropriate and some level of overrides is to be expected, high rates of overrides can indicate a lack of acceptance of the UM system from medical staff.

The prospective review process enables health care managers to reduce the amount of services that are prescribed unnecessarily, thereby avoiding unnecessary costs. We also note that such prospective reviews are an especially important tool in health systems with a high risk of malpractice litigation, such as prisons. This is because in such settings physicians often have an incentive to overprescribe health care services in order to insulate themselves from lawsuits alleging insufficient care, a practice known as "defensive medicine." Defensive medicine is especially expensive in prison settings because referrals to outside care include not only the cost of the care itself, but also the cost of guarding and transporting an inmate to and from such medical appointments. While actual medical costs vary depending on the type of treatment the inmate receives, medical guarding and transportation can cost more than $2,000 per inmate per day. Prospective reviews reduce defensive medicine by providing physicians with an objective and evidence–based justification for denying unnecessary medical treatment.

While CDCR has been using UM since 1996, the department has not always taken the necessary steps to ensure that the UM system is implemented effectively (such as properly training staff). We note, however, that the current Receiver has paid particular attention to establishing an effective UM system in recent years and data suggest that his efforts have led to significant cost savings. For example, expenditures on contracts for specialty medical care services has declined by 44 percent from $695 million in 2008–09 to $388 million in 2010–11, primarily due to a decline in the number of inmates referred for specialty care services. Between October 2009 and October 2011 the rate of referrals for specialty medical care decreased from 98 referrals per 1,000 inmates per month to 70 referrals per 1,000 inmates. This trend suggests that medical staff are increasing their use of and compliance with the UM system, thereby avoiding unnecessary referrals.

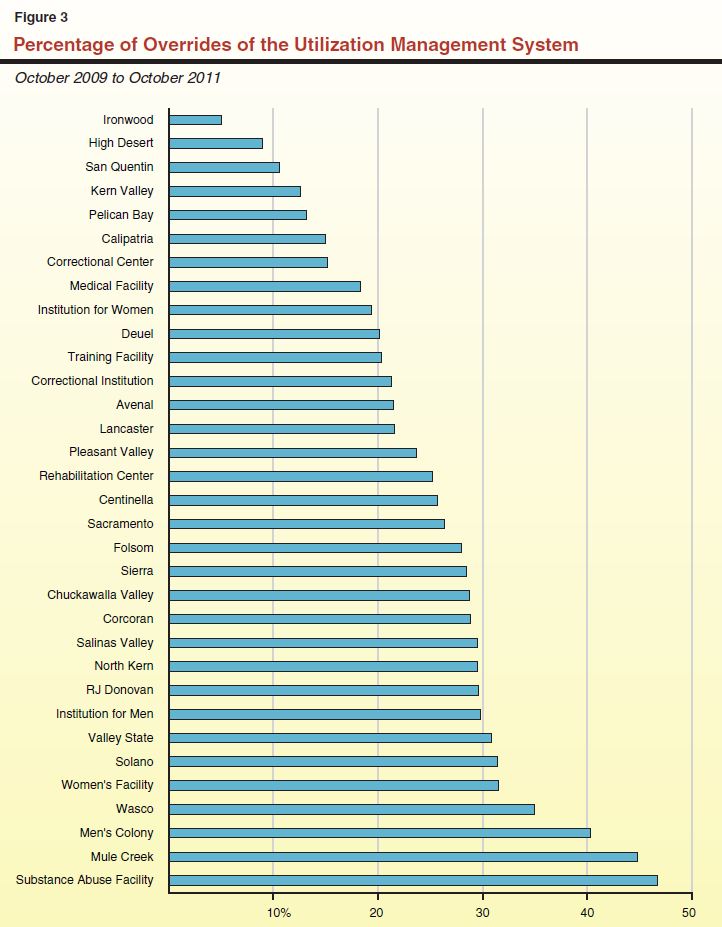

While the above trends are encouraging, other data suggest that the system is still not being employed as effectively as it could be. For example, the UM system used by the Receiver is not centrally controlled as is typical in other health care systems. Instead, UM decisions in California are made at individual prisons. This has led to varying degrees of compliance. For example, data on the rate at which medical staff override the recommendations of the UM system (such as by referring inmates to specialty care when the UM system does not recommend doing so) provides evidence of a UM system that is not applied consistently across institutions. Although the Receiver's monthly report on key performance indicators does not include data on the rate of such overrides, the Receiver's office provided the data at our request. As shown in Figure 3 there is a large amount of variation in the rates of overrides in the state's 33 prisons, ranging from less than 10 percent in two prisons to more than 40 percent in three other prisons.

Limited Use of Telemedicine. Telemedicine, or the delivery of health care services via interactive audio and video technology, can both increase inmates' access to care—particularly to specialty care—and reduce the cost of delivering that care. Through the use of telecommunications systems, live images of the patient are transmitted over broadband internet or telephone lines to the doctor's office. Equipment such as exam cameras, monitors, and electronic stethoscopes allow physicians to treat patients remotely without meeting them face–to–face. Telemedicine is used by public and private health care providers throughout the country to treat patients who otherwise would have to travel long distances to confer with a health care professional. Telemedicine is also used in most states to provide some health care services to incarcerated persons. In fact, 26 of 44 states surveyed by the Corrections Compendium in 2010 were using telemedicine to deliver some medical services to inmates in their prisons.

Correctional facilities have found that telemedicine increases access to care and enhances public safety. This is because inmates who otherwise would have been transported into the community for medical treatment instead remain inside prison walls for their consultation. In addition, telemedicine reduces costs associated with transporting inmates to outside medical facilities. As previously mentioned, the cost of guarding inmates when they are transported outside of prison is roughly $2,000 per inmate per day. Depending on the frequency with which prisons use telemedicine, the costs for telemedicine staffing, equipment, and maintenance can be more than offset by savings generated from avoiding medical trips. Contract costs with physicians may also be lower for correctional systems that deliver health care services using telemedicine as opposed to traditional in–person consultations. This is because telemedicine provides the opportunity to bid out contracts to a larger pool of physicians licensed to practice in a given state, rather than only to those contract physicians practicing in the region of a specific prison. Moreover, telemedicine improves inmates' access to health care by enabling correctional systems to expand their provider network to include physicians located outside the immediate vicinity of prisons.

In view of the above benefits, the use of telemedicine in California prisons has increased in recent years under the federal Receivership. For example, the number of telemedicine encounters increased from about 9,000 in 2004–05 to about 23,000 in 2010–11. In spite of this increase, however, it appears that California has not taken full advantage of this technology for inmates. By comparison, Texas (a state with fewer inmates than California) currently records about 40,000 telemedicine encounters annually. This is partially because inmate–telemedicine relies on the use of other technologies (such as a health care scheduling system and high–speed network infrastructure) that have only recently been developed and made widely available in California's prisons. In addition, the Buerau of State Audits (BSA) reported in 2009 that the Receiver's office had failed to track data that could guide the expansion of telemedicine by identifying which types of medical consultations are best suited for telemedicine and which institutions could benefit most from the technology. In a follow–up report in March 2011, BSA noted that the Receiver had still not begun tracking such data. In total, we estimate that the state could achieve savings in the millions or low tens of millions of dollars annually through the expansion of telemedicine.

Inefficient Management Structure. As previously mentioned, CDCR is responsible for the day–to–day operations of the state's prisons, while CPHCS operates the inmate medical services program in the prisons. As a result, CPHCS is a separate organization from CDCR with its own executive staff that employ individuals to carry out various administrative functions (such as IT, human resources, procurement, and budgets). We estimate that this duplicative administrative staffing structure results in unnecessary costs in the low tens of millions of dollars annually.

Having two sets of executive management staff can also lead to confusion over responsibilities and complicate the task of coordinating the management of the inmate medical program with CDCR's inmate mental health and dental care programs. For example, while the Receiver is responsible for procuring pharmaceuticals on behalf of the mental health and dental programs, he does not have management authority over psychiatrists and dentists, which limits his ability to ensure that they are prescribing drugs in the most cost–effective way. We note that in 2010 the OIG found that there was inconsistent monitoring by the Receiver of prescribing practices. According to the OIG, this inconsistency led to the prescription of expensive drugs, despite the availability of less costly alternatives. The OIG recommended that the Receiver identify individuals who are prescribing more costly drugs and take actions to rectify their behavior. The Receiver's ability to implement this recommendation, however, is complicated by the fact that many of these prescribers are psychiatrists who are not under his management.

Given the recent federal court order to create a transition plan, the conclusion of the Receivership now appears to be in sight. However, as we discussed above, our analysis indicates that the inmate medical care program in California continues to suffer from various inefficiencies. Moreover, we find that there are a couple of key issues that would still need to be addressed to ensure that the state is positioned to sustainably deliver a constitutional level of inmate medical care in a post–Receivership future. Specifically, there will need to be some level of independent oversight and evaluation of the inmate medical care provided by CDCR. In addition, the department should take steps to bring the cost of delivering care to a level that is more in line with what other states are spending, particularly given the state's fiscal condition.

Independent Oversight and Evaluation. Given CDCR's poor track record in providing medical care to inmates, it would be unwise to return control of the inmate medical program to the department without first establishing independent oversight and evaluation. Failure to establish effective oversight mechanisms could result in a failure of the state to recognize if the department begins to backslide on recent improvements in the quality of inmate medical care. Absent recognition of problems, the state cannot effectively undertake corrective action. Ongoing problems, if unaddressed, could result in renewed federal court oversight. We expect that the establishment of independent oversight will also be a priority of the federal court.

Delivering Care Cost–Effectively. As we discussed above, inmate medical expenditures have increased dramatically in recent years to the point where California now spends significantly more than other states. Given the pressure these costs put on the state's General Fund, along with the state's ongoing fiscal struggles, it is important that the inmate medical program be operated as efficiently as possible. The state may not be able to afford to pay $1.5 billion or more each year on inmate medical costs. Operating a more efficient inmate medical system, therefore, will make it more sustainable in the long run and less susceptible to budget cuts that could reduce the ability of the department to deliver services to inmates effectively.

As we discuss in the nearby box, there have been a couple of proposals in recent years which attempted to improve the inmate medical care program by providing independent oversight and/or delivering care in a more cost–effective manner.

Recent Proposals to Improve Inmate Medical Care

In recent years, two major proposals have been put forward to restructure inmate medical care in California in order to address some of the fundamental problems with the current program. First, the Schwarzenegger administration commissioned a consulting firm to develop a proposal to partner with the University of California (UC) for the delivery of inmate health care. Second, the current Receiver released a draft proposal to create a new authority to manage inmate health care in the state.

Proposal to Partner With UC for Inmate Health Care. In 2010, a consulting firm commissioned by the Schwarzenegger administration proposed a partnership between the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) and UC whereby UC would assume responsibility for delivering inmate health care. The plan called for the creation of an independent California Health Care Authority that would contract with UC for the provision of inmate medical, mental health, and dental care. It would also develop oversight measures and audit systems, with CDCR being responsible for auditing the quality of care provided by the university.

Proposal to Establish Prison Health Care Authority. In 2010, the Receiver provided the Legislature with a draft proposal to create a new authority that would be independent of CDCR and would manage inmate health care. Under the Receiver's draft proposal, the authority would receive a continuous appropriation (meaning an annual legislative appropriation would not be required) to fulfill its duties and would be governed by a board consisting of nine members. The board would contract with the UC to conduct an annual assessment of the cost–effectiveness of the authority's operations and the quality of care being delivered. All current health care staff at CDCR, as well as the California Prison Health Care Services support staff, would become employees of the authority.

Both Proposals Include Independent Oversight. The major potential advantages of both of these proposals is that they would provide independent oversight of the inmate medical care program. Establishing this type of independent oversight would be an important step towards demonstrating to the Plata court that the state can maintain a constitutional level of care. In addition, both proposals assign the responsibilities for delivering and evaluating inmate health care to separate agencies, thus avoiding some of the conflicts that arise from having these responsibilities rest with the same agency.

Both Proposals Would Likely Be Expensive. However, our analysis indicates that both proposals could be expensive. For example, awarding a contract to UC without a competitive bidding process provides little incentive for UC to deliver care in the most cost–effective way possible. Similarly, the Receiver's proposal to fund the new health care authority with a continuous appropriation is problematic because it restricts the Legislature's authority to make annual budget adjustments. Such adjustments would likely be necessary over time because of changes in the inmate population and its health care needs, the state's fiscal situation, and the Legislature's budgetary responsibility to balance correctional health care funding with other competing priorities in the state. Furthermore, a continuous appropriation would provide no incentive to provide more efficient delivery of services. In addition, by assigning the management responsibilities to an entity other than CDCR, the proposal could continue the inefficiencies that currently stem from the Receiver employing separate administrative staff to fulfill functions (such as information technology management, human resources, and accounting) that could be completed by existing CDCR administrative staff.

Like California, several states have been subject to federal court oversight of their inmate medical care in recent decades. In this section, we discuss the experiences of some of these states. First, we discuss how two states, Texas and Florida, established independent oversight to help remove themselves from court oversight. Also like California, nearly every other state in the nation is facing rising inmate medical care costs. Increasingly, some states have attempted to deliver inmate health care in a more cost–effective manner by contracting with experienced managed health care organizations to provide primary health care services. Below, we discuss how the approaches that Texas, Florida, and Kansas took to contracting out resulted in varying levels of success.

Oversight Can Be Implemented Successfully

Florida—Federal Court Oversight Ended in 1993. In 1972, a federal court found that the Florida Department of Corrections (FDOC) had failed to provide a constitutional level of medical, mental health, and dental care to its inmates and assumed oversight of the delivery of such care. In 1986, the Florida Legislature created an independent state agency known as the Correctional Medical Authority (CMA) to (1) monitor correctional health care and (2) advise the Governor and Legislature regarding the quality of care provided, and the level of funding provided in the annual budget for such care. In 1993, the court ended its jurisdiction over the state's correctional health care system and returned control of the system to FDOC under the condition that the CMA would continue to provide independent oversight, in order to ensure the continued delivery of adequate health care. Since that time, the FDOC has successfully retained full control of its inmate health care system with the ongoing oversight of the CMA, which was later eliminated by the Florida Legislature in August 2011.

Texas—Federal Court Oversight Ended in 1999. In 1980, a federal court found that the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ)—formerly called the Department of Corrections—failed to provide a constitutionally adequate level of health care to its inmates and appointed a special master to monitor and oversee various health care improvements. In 1994, the state created the Correctional Managed Health Care Committee (CMHCC) to serve as the oversight and coordination authority for the delivery of health care services to individuals incarcerated in facilities operated by TDCJ. The committee consists of nine members, including two members from the University of Texas and two members from Texas Tech University. The CMHCC contracts with the public universities in Texas—specifically, the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) and Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center—to provide all inmate health care services. The committee is responsible for developing these contracts, establishing reimbursement rates, monitoring the quality of care provided, and making sure providers comply with the terms of the agreed–upon contract. This arrangement, including the oversight provided by CMHCC, helped to facilitate the end of court oversight over Texas' inmate health care system in 1999.

A 2004 audit by the Texas State Auditor's Office, however, identified a couple of significant problems with the CMHCC. Specifically, the auditor found that the committee was not completely independent of the universities it oversees because four of the board members were employed by the universities. In addition, the auditor found that the contracts between CMHCC and the universities lacked basic provisions such as for evaluating contractor performance, remedying nonperformance, and requiring expenditure reports. The auditor also found that the CMHCC was not ensuring that it was only reimbursing the universities for costs allowed under the terms of the contracts. In 2011, the auditor found that UTMB had been inappropriately charging the state for millions of dollars in costs that were deemed not reimbursable. These audit findings suggest that it is important for an oversight agency to be truly independent and be subject to scrutiny itself.

Contracting Out Can Reduce Costs

In 2004 (the most recent year for which data is available), 32 states contracted out for some or all aspects of their adult correctional health care services. Most of these states contract with private prison health care providers while a small but growing number of states contract with their public universities. While the reasons for contracting out vary from state to state, one common reason is that experienced managed health care organizations can be more efficient at employing cost avoidance measures (such as UM). For example, one research study published by the National Institute for Corrections in 2000 found that states using some form of capitated contracts for primary health care in prisons had significantly lower correctional health care costs than those states that did not use such contracts. (In a capitated rate contract, the provider agrees to provide specified health care services to inmates based on a fixed daily reimbursement rate.) Specifically, the study found that the daily cost of providing health care services for inmates was roughly $2.22 less per inmate in states that used capitated rate contracts. Given the current prison population in California, a cost reduction of $2.22 per inmate per day would result in savings of over $100 million annually.

Below, we examine the experiences of three states that have contracted out for their inmate health care: (1) Kansas, which has largely been successful at contracting out with various private providers; (2) Texas, which has had a mixed experience contracting with its public universities; and (3) Florida, which had serious problems when it attempted to contract with various private providers.

Kansas Has Successfully Contracted With Private Providers. In the late 1980s, the Kansas Department of Corrections (KDOC) faced significant challenges in delivering inmate health care. For example, the department was unable to hire sufficient qualified staff and had trouble meeting the financial demands brought on by rising health care costs. In an attempt to meet its staffing needs and control rising costs, KDOC solicited bids from private companies to provide health care services to the inmates in its prisons. Since 1988, KDOC has been contracting with various private providers for these services. Currently, a private entity provides medical, mental health, and dental care to inmates at an annual capitated rate of about $4,900 per inmate. Under such an arrangement, the financial risks of potential cost increases are shifted from the state to the provider. This is because the state's costs under the contract cannot exceed the established capitated rate. In order to ensure that the private provider is not earning excessive profits by denying inmates necessary health care, the existing contract requires the provider to submit to the state a detailed accounting of how its budget is allocated and how much profit they are earning. In addition, the contract specifies certain performance measures that must be met as well as specific penalties that will be assessed if they are not. For example, if an inmate does not receive a physical exam within seven days of admission to a Kansas prison, the private provider is assessed a $100 fine. Based on our discussions with representatives from Kansas, the state has generally been satisfied with the cost and quality of inmate health care provided by private entities. For example, between 2000 and 2008, the cost of inmate health care per inmate in Kansas increased by 9 percent annually. For comparison, one recent study surveyed 22 states and found that those states experienced an inmate health care cost increase of 11 percent annually over the same time period. In California, per inmate health care costs increased by 18 percent annually.

Texas Has Had Mixed Results Contracting With Public Universities. As mentioned earlier, Texas began contracting with its public universities to provide inmate health care services in 1994. Under the contracts, the public universities provide inmate medical, dental, and mental health care services to inmates based on a capitated rate of reimbursement. The contracts were seen as a way to contain rising inmate health care costs as well as to meet a court mandate to improve the quality of care. Officials at the UTMB estimate that the state was able to achieve roughly $215 million in savings over the first six years of the contracts through various cost–containment measures, including the increased utilization of telemedicine. In addition, data provided by the UTMB indicates that inmate health care outcomes (such as mortality rates for inmates with HIV and asthma) also improved over this time period. However, in recent years it appears that the partnerships between TDCJ and the universities has become strained. Specifically, administrators at UTMB have expressed discontent with the level of funding provided by the state for inmate health care services and threatened to terminate the existing contract with the state. While the TDCJ is currently negotiating with the UTMB to extend its contract, officials at TDCJ are also considering contracting directly with private providers for inmate health care services.

Florida's Attempt to Contract With Private Providers Largely Failed. In an attempt to curtail rising inmate health care costs, Florida contracted with a private correctional managed health care organization to provide inmate health care in prisons in the southern region of the state beginning in 2001. In the following years, the outsourcing initiative suffered a variety of setbacks—including the early termination of the contract by the initial provider, difficulties in finding qualified competitive bidders for subsequent contracts, and poor performance by contracted providers. As a result of these problems, the state began phasing out the contracts and today most of the staff providing inmate health care are state employees.

In a 2009 report, the Florida Office of Program Policy Analysis and Government Accountability identified several factors that led to the failed outsourcing effort. The report found that FDOC failed to adequately monitor and oversee its contracts with private health care providers. For example, the department failed to (1) clearly articulate the terms and conditions of contracts, including penalties for noncompliance; (2) establish performance measures; and (3) properly train contract monitoring staff. In addition, they found that the state had failed to obtain inmate health care services at the lowest possible cost because contracts were often awarded without a competitive bidding process.

As we discussed earlier, a recent federal court has ordered all parties involved in the Plata case to file a joint report to the court by April 30, 2012 on how the state will manage inmate medical care following the conclusion of the Receivership. The state, therefore, may soon be in a position to implement changes without having to seek court approval. Moreover, the Legislature may soon be requested by the administration and federal court to pass legislation designed to implement some aspects of the court–approved transition plan that requires changes to state law. In addition, the administration may request that the Legislature appropriate funds to pay for additional inmate medical services that could be part of the plan.

Based on our research and the lessons learned from other states, we have identified two steps the state should take to establish a sustainable, constitutional, and cost–effective system of inmate medical care in California. First, the state should create an independent board to provide oversight and periodically evaluate the inmate medical care program. Second, the state should control inmate medical care costs by addressing inefficiencies in the inmate medical care program and contracting with one or more managed care organizations to provide medical care in one or more prisons on a pilot basis. Figure 4 summarizes these recommendations, which we describe in more detail below.

Figure 4

Summary of LAO Recommendations

|

|

|

|

Establish a New State Board to Oversee Inmate Medical Care

|

- Require board to evaluate care and provide policy direction

|

- Appoint health care professionals and experienced managers to board

|

- Fund the board with savings from ending the Receivership

|

|

Control Inmate Medical Care Costs

|

- Address inefficiencies in the Inmate Medical Program

|

- Contract with managed care organizations for medical care on pilot basis

|

We also note that it will be important for the Legislature to ensure that any transition plan developed and implemented by the administration and the Receiver appropriately protects its authority to provide oversight and accountability of the inmate medical program and expenditures. For example, the Legislature should oppose any proposals that include a continuous appropriation for inmate medical care. Instead, the Legislature should have the ability to review and approve funding for the program as part of the annual state budget process. This would allow the Legislature to hold program managers accountable for their expenditures and reduce future appropriations if it identifies areas of inefficiencies. In addition, the Legislature should be able to determine what, if any, exceptions the inmate medical program should have from state laws and regulations that apply to other agencies. As discussed above, the Receiver is currently exempt from adhering to certain laws and regulations related to personnel, IT, and contracts. In some cases this has led to an increased risk that the state is overpaying for certain contracted services. The Legislature could increase its ability to oversee the inmate medical program by choosing to require CDCR to adhere to some state laws and regulations from which the Receiver is currently exempt (such as those requiring competitive bidding for contracts and reporting on IT projects).

In order to ensure that the state's inmate medical program is delivering a constitutional level of care to inmates, we recommend that the Legislature create a new oversight board, independent of CDCR, to oversee the delivery of inmate medical care. (The Legislature might also consider requiring the board to oversee inmate mental health and dental care programs.) Based on the experiences of Texas and Florida, we believe that the creation of an independent oversight board would have several benefits. First, it could facilitate the conclusion of federal court involvement in California's prison medical care system by demonstrating that the state has institutionalized a system for providing ongoing oversight and evaluation of the program. In addition, an independent board would help to identify any deterioration in the quality of inmate medical care before it reaches a point where the state finds itself subject to future lawsuits. Finally, the board would increase transparency and accountability in the inmate medical program by reporting performance measurements that could be used by the Legislature and the administration to hold managers accountable for achieving good outcomes.

Duties of Proposed Oversight Board

The Legislature could assign different responsibilities to the oversight board. In our view, these duties should include evaluating the provision of medical care, providing budget and policy direction, contracting responsibilities, and ensuring accreditation.

Evaluation of Inmate Medical Care. Under our proposal, the primary purpose of the board would be to conduct periodic evaluations of the quality of care being delivered by CDCR. Such evaluations should focus not only on adherence to policies and procedures that have been mandated by the court, but also on actual health outcomes (such as morbidity and mortality rates). In May 2011, RAND Corporation released a report, commissioned by the Receiver, which recommended roughly 80 outcome measures that could be used to evaluate California's inmate medical program. This report could provide a good starting point for the board in determining what performance measures it should use in its evaluations. In fact, the Receiver has already started tracking roughly half of the measures recommended by RAND and intends to eventually implement about two–thirds of them.

The board could also set performance goals, measure the degree to which CDCR meets those goals, and regularly report its findings to the Governor and Legislature. We note that the Receiver has already developed a number of benchmarks based on data from other health systems which are used to set goals for the current inmate medical program. These existing benchmarks could serve as a good starting point for the board. In addition, having the board publicly report on CDCR's progress in meeting these goals would promote transparency in the system and allow the Legislature and Governor to hold the department accountable for meeting the prescribed performance goals.

Budget and Policy Direction. The board could also be responsible for reviewing CDCR's medical care budget and expenditures to assess the degree to which the department is delivering care as cost–effectively as possible. It could report to the Legislature and Governor annually regarding the appropriateness of the budget including any recommendations where certain spending should be increased or decreased. Finally, the board could provide policy direction to CDCR for the inmate medical program. For example, the board could recommend that the department adopt new technologies (such as electronic medical records) that could increase the quality of care. In addition, it could establish guidelines, such as what type of medical appointments can be done through telemedicine rather than a traditional consultation.

Contract Development and Monitoring. The oversight board could also be responsible for developing and monitoring a pilot contract with a managed care organization, which we describe in more detail later in this section. In our view, the board would be in a much better position to fulfill this responsibility than CDCR, for several reasons. First, the board would be comprised of individuals with expertise in (1) delivering and managing medical care and (2) measuring the quality of such care, which are integral skills for contract oversight. Second, since the board would also be responsible for developing performance goals and measurements for CDCR, it would be able ensure that an appropriate level of consistency is applied in developing similar metrics for other providers. Third, CDCR has historically had difficulty managing certain contracts with private providers. For example, in 2007 the OIG found that the department did not provide adequate oversight of its in–prison substance abuse treatment contracts.

Accreditation. The board could also be responsible for ensuring that inmate medical care is accredited in all of the state's prisons. Currently, 31 states have some or all of their prisons accredited for health care by either the National Commission on Correctional Health Care or the American Correctional Association. None of California's prisons have national accreditation, though prison medical facilities treating higher acuity inmates do have to be licensed by the state. The advantage of accreditation is to ascertain whether a prison is operating its medical program in a way that is consistent with national standards. This can provide some protection from legal risks associated with litigation related to inmate care. Also, prior to implementation of a robust set of performance measures, accreditation could serve as an important indicator to the Plata court that the state is delivering constitutional care.

Structure and Funding of the Oversight Board

Organizational Structure. We recommend that the oversight board be made up of medical care professionals (such as physicians and nurses), leaders of managed care organizations, correctional experts, and academic researchers. Florida's nine–member CMA, which consisted of physicians in private practice, hospital administrators, and academic experts, could serve as one model for developing California's medical care oversight board.

Although the board would be independent, it may make sense to place the board within the OIG for administrative purposes. The OIG could provide administrative functions (such as human resources, IT, and budget support) to the board and its staff. In addition, existing OIG staff that currently perform inmate medical care audits could help support the board. The board also could call upon other OIG staff to provide audits of the department's medical program budget as needed. We note, however, that a small number of additional staff may be needed to help the board with some of its oversight functions. For example, there may be a need for staff with expertise in medical care quality measurement to assist in the development and implementation of performance measures.

Board Funding. We estimate that the cost of our proposed board would be small relative to the size of the prison medical care budget. In Florida, the CMA has historically been operated on an annual budget of less than $1 million. While California's board may need to be larger to account for its bigger prison system and the need for relatively more oversight in the near term, we estimate that the cost would likely not exceed a couple million dollars annually. However, these new costs would be more than offset by savings resulting from the elimination of the Receiver's office. If the administrative staff at CPHCS was merged with CDCR's administrative staff, we estimate that efficiencies could be achieved, resulting in savings in the millions or low tens of millions of dollars annually.

In addition to having independent oversight and evaluation, the state's inmate medical program also needs to be more cost–effective in order to sustainably deliver a constitutional level of care. Accordingly, we recommend below a series of steps that could be taken in both the short and longer term to address existing inefficiencies and further control inmate medical costs.

Address Identified Inefficiencies

Our analysis indicates that there are a few steps that could be taken to address the inefficiencies we have identified in the current inmate medical program. In the near term, the Receiver could make certain changes to how UM and telemedicine are currently being used, which we describe below. In the longer term, following the conclusion of the Receivership, the state would have the authority to make these changes on its own accord. In addition, following the conclusion of the Receivership, the state could also consolidate existing CPHCS administrative staff with CDCR administrative staff.

Increase Consistency in the Application of the UM System. The Receiver could begin taking steps to centralize control of the UM system so that the process of overriding the system requires approval by headquarters staff. This would increase the consistency with which the UM system is applied across prisons. To the extent that centralizing the approval process requires the adoption of certain IT capabilities that do not currently exist, the Receiver could take other measures to increase compliance with the UM system in the short term. For example, the Receiver could include data on UM override rates in his monthly reports on key performance indicators. Such data could then be used to identify prisons and clinicians that have above average rates of UM overrides. The Receiver could then take steps (such as increased training on applying the UM system) to bring the override rates more in line with the state average. We estimate that if the system–wide rate of UM overrides could be brought down to 10 percent that could result in about 19,000 avoided referrals to specialty care on an annual basis. This would translate to savings of roughly $80 million annually.

Increase Use of Telemedicine. While the Receiver has taken significant steps towards increasing the utilization of telemedicine in recent years, there are probably still unexploited opportunities to further increase its utilization rate. In the past couple of years, the Receiver has designated a number of specialty care services (such as orthopedics) for which telemedicine is the default mode of care delivery. This means that physicians are directed to use telemedicine to deliver the services unless there are extenuating circumstances that make telemedicine impractical. The Receiver could further expand the list of specialty care services for which telemedicine is the default mode of care. In addition, the Receiver could expand the use of telemedicine to deliver primary care services, particularly at geographically remote prisons where it is difficult to hire qualified physicians. We estimate that if the rate of telemedicine utilization was increased to a rate similar to Texas (about 40,000 annual appointments) that would result in savings in the low tens of millions of dollars annually.

Consolidate Administrative Staff. Following the conclusion of the Receivership, the Legislature could consolidate CPHCS administrative staff with CDCR administrative staff. Since these two sets of administrative staff currently perform similar functions, such a consolidation would allow for the elimination of unnecessary administrative overhead. We estimate that this could result in savings in the low tens of millions of dollars annually. In addition, the consolidation of management would eliminate the confusion and inefficiencies that result from having divided management responsibilities.

Contract With Managed Care Organizations For Medical Care on a Pilot Basis

While the above steps would result in significant savings in the near term, they would not be sufficient to bring the cost of the inmate medical program in California more in line with other states. Doing so would likely require a more fundamental change in the state's approach to delivering inmate medical care. This is because the existing system does not include strong incentives for inmate medical program managers to proactively implement cost–containment measures. One strategy the state could pursue to address this fundamental problem is to contract out the responsibility for providing inmate medical care (including primary and specialty care) to one or more entities with experience in delivering managed health care. Contracting out would introduce competition into the inmate medical care system, which would incentivize the adoption of cost–containment measures.

CDCR Already Contracts Out for Some Health Care Services. In 2010–11, the state spent roughly $2.2 billion on adult correctional health care (including medical, mental health, and dental care). While most of these costs were for state employees to provide basic health care services to inmates, a significant portion of the budget paid for contracts with private vendors for a variety of specialized services (such as complicated surgical operations) that are often unavailable at the state's own prison hospitals and clinics. For example, prison health care staff often refer patients suffering from respiratory, heart, and kidney diseases to outside care for treatment. In 2010–11, a total of about $388 million (18 percent) was spent on such specialty care services.

In addition, both CDCR and the Receiver's office often utilize private registries to meet their staffing needs. This is primarily because they are often unable to fill all of their authorized correctional health care positions. For example, in 2010–11, the Receiver spent roughly $82 million on registry services mainly for nurses, physicians, and pharmacists, and CDCR spent about $39 million on registry services for the mental health and dental programs. Moreover, the Receiver has recently contracted with a Preferred Provider Organization (PPO) in order to gain access to a network of community care providers that deliver inmate medical services based on a fixed fee–for–service rate negotiated by the PPO. We also note that the Receiver previously maintained a contract with a private provider to manage the purchasing and distribution of pharmaceuticals.

Contract Should Be Competitively Bid and Done on a Pilot Basis. Contracting out tends to work best when there is a well–developed and competitive private sector market for the activity under consideration. This is because a competitive market tends to incentivize efficiency and innovation. Our research indicates that there are a number of private correctional health care providers operating in California and nationally. We spoke to several of these providers that expressed an interest in bidding for the opportunity to deliver medical services in the California prison system.

Based on our conversations with these firms, however, it appears unlikely that any one provider could take full responsibility over the medical care delivered in California's prison system, particularly given its size, complexity, and geographic distribution. Instead, the state could contract for medical care at an individual prison or a few selected prisons on a pilot basis. This should be done through a competitive bid process in which any qualified provider is allowed to bid for the contract.

Potential Cost Savings. In general, private correctional health providers offer medical care contracts on a capitated basis. This type of contract allows the state to shift the financial risk to the provider. Moreover, it creates a strong incentive for the provider to carefully manage care and control costs through a variety of management techniques. Such techniques include (1) using UM technology to reduce unnecessary and costly referrals to outside care; (2) negotiating bulk–purchasing rates for medical supplies, pharmaceuticals, and contracted specialty care; and (3) implementing efficient staffing plans. Given the above incentives, the state could potentially achieve cost savings from a capitated contract. While there is one study indicating that states with capitated rate contracts have lower costs that other states do not, there is generally a lack of controlled research on the fiscal and programmatic impacts of contracting out for correctional health care services. Therefore, it is unclear what level of savings, if any, California would achieve from contracting out for the delivery of primary health care services in the prisons. Any potential cost savings from contracting out should be weighed against other factors, such as the quality of care. For this reason, contracting for care on a pilot basis could be a valuable way to determine the positive and negative impacts on costs and quality of care.

Contract Development and Monitoring. A well–defined contract is critical to ensuring the success of any medical care outsourcing effort. When outsourcing efforts go awry, as they did in Florida in the early 2000s, it is often because of poorly written contracts. Alternatively, when outsourcing efforts are successful, as they have been in Kansas, contracts include clear expectations and accountability measures. With that in mind, there are several principles that should be followed when developing a contract for the delivery of inmate medical care.

First, contracts should clearly specify performance targets that the contractor must meet, as well as penalties that will be imposed for failing to meet them. We believe that there should be a continuum of penalties so that the state has the ability to hold the provider accountable for performance without having to resort to contract termination.

Second, the state should evaluate bids based on criteria that include the performance record of the bidder as well as the price. Selecting a bidder on the sole basis of price can lead the state to award the contract to a bidder that has bid so low that they are forced to deliver deficient care in order to earn a profit.

Third, CDCR should utilize contract monitors who receive standardized training to ensure that they are familiar with the requirements of the contract and understand how to work with the provider to resolve issues as they arise. As discussed in the nearby box, there are some legal issues to more widely contracting out for inmate medical services.

Legal Considerations for Contracting Out

Our analysis indicates that there are some legal hurdles to overcome if the state were to contract out for additional inmate medical care services. This is because current law, specifically Article VII of the State Constitution and related statutory and case law, restricts the state's ability to outsource services currently performed by state employees, including primary inmate medical care services.

There are, however, circumstances where the state can legally contract out. For example, in a court case related to contracting out for the construction and maintenance of state highways, known as Professional Engineers in California Government vs. Department of Transportation, the California Supreme Court found that the state could contract for services on an experimental basis. In addition, Section 19130 of the Government Code and associated case law allow contracting out for services that cannot be adequately, satisfactorily, or competently performed by state employees. This exception has allowed the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to contract for specialty health care services (such as complicated surgical operations).

Thus, while the legality of contracting out all inmate medical care is uncertain and would probably ultimately be determined by the courts, we believe that the state could enter into such a contract on a pilot basis, consistent with the ruling in the Professional Engineers case. Furthermore, the state has demonstrated that it lacks employees with sufficient expertise to adequately manage a medical care system of the size and complexity of California's prison system—as evidenced by the current reliance on registry staff, years of increasing costs, and the inadequate health outcomes that ultimately led to the federal Receivership. Accordingly, the state could also justify contracting out on the grounds that the inmate medical program meets the exceptions established by Section 19130 of the Government Code.

We also note that, as has been made clear by the U.S. Supreme Court decision in West v. Atkins (1988), contracting for health care services does not alter the state's responsibility to deliver a constitutional level of health care. In that case, the court held that states can be held legally liable for inadequate care provided by private physicians working under contract with the state.

Studying the Effects of Contracting for Inmate Medical Care. In order to determine what effect contracting for inmate medical care has on the cost and quality of care, the state should study any pilot undertaken. For example, the state could contract with one of the state's public universities to conduct the study. We estimate that such a study likely would cost several hundred thousand dollars with the exact amount depending on several factors, including the number of prisons included in the pilot and the duration of the evaluation period. One of the criteria the state should use in selecting the location for the pilot is which prison or prisons are well suited for such a study. For example, the state could select two prisons that are similar in terms of the medical needs of their inmates and contract for care in one of them. Comparing the quality and cost of inmate medical care in these prisons before and after the pilot project would provide evidence on the impact of contracting for primary medical care services.

Significant changes have been made to the state's inmate medical care program since it was placed under Receivership in 2006. In determining how to transition the responsibility for managing the program back to state control, the state should focus on two keys to long–term success: (1) creating independent oversight of the program, and (2) controlling inmate medical costs. Based on our review of experiences in other states, we therefore recommend that the state create an independent board to provide oversight and evaluation of the inmate medical care program, take steps to address current operational efficiencies to bring state expenditures to a more sustainable level, and establish a pilot project to contract for medical care services.