Introduction

Over 150 years ago, the state’s first adult education program began offering instruction to residents seeking basic language and job skills. Today, considerable need continues to exist for such services. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, for example, more than 10 percent of Californians over 24 years old have less than a ninth grade education, and an additional 9 percent of Californians over 24 years old have attended high school but lack a high school diploma. For some, adult education can serve as a “second chance” after dropping out of high school. For others (such as recent immigrants), adult education can be a first opportunity to learn English and train for a career.

Despite the importance of the mission, funding for adult education in California has declined significantly over the past few years. And, despite adult education’s long history, the state continues to struggle with fundamental issues relating to the system. To help the Legislature address these challenges, this report provides a comprehensive overview and assessment of adult education services provided by school districts (through their adult schools) and CCC—the largest providers of such instruction in the state. (Other providers include nonprofit community–based organizations and public libraries.) The first part of the report contains background on California’s system of adult education. The second part identifies five major problems with the current adult education system, and the third part provides a package of recommendations for improving the state’s adult education system.

Background

Many Complexities of Adult Education. This part of the report provides an overview of adult education—reviewing its history in the state, its array of course offerings, enrollment, funding, and data on program outcomes. Adult education in California is a complex—and in many ways confusing—system consisting of multiple providers and policies. The material presented here is intended to provide relevant information for understanding our later analysis and recommendations.

Adult Education Serves Various Types of Students. In contrast to collegiate (postsecondary) education, the primary purpose of adult education is to provide persons 18 years and older with precollegiate–level knowledge and skills they need to participate in society and the workforce. Adult education is intended to serve various types of students, including:

- Immigrants who want to learn English, obtain citizenship, and receive job training.

- Native English speakers who are illiterate or only can read and write simple sentences.

- High school dropouts who want to earn a diploma or General Educational Development (GED) high school equivalency certificate to increase their employability or attend college.

- High school graduates who seek to earn a college degree but have not yet fully mastered reading, writing, or mathematics at precollegiate levels.

- Unemployed persons or unskilled workers earning low wages who seek short–term vocational training to improve their economic condition.

In addition to serving these types of students, adult education fulfills other purposes. For example, adult education also serves older adults who want to stay active physically and mentally as well as parents seeking to learn effective techniques for raising their children.

The Entangled History of School Districts and Community Colleges

State’s First Adult Schools Run by School Districts. As shown in Figure 1, in 1856 the San Francisco Board of Education established the state’s first adult school. By the end of the 19th century, adult schools (commonly known as “centers for Americanization”) were providing evening classes in English and other subject areas in a number of cities, including Sacramento, San Jose, and Los Angeles. In the early 1900s, school districts were legally entitled to operate two distinct types of programs for adults: (1) adult schools to provide instruction to immigrants and others lacking basic language and job skills, and (2) junior colleges to provide instruction to high school graduates in the first two years of postsecondary education.

Figure 1

State’s Adult Education System Developed Over Long Period of Time

|

|

|

|

1856

|

San Francisco Board of Education approves state’s first “evening” (adult) school.

|

|

1907

|

State Supreme Court rules that adult schools have legal right to state funding. Legislature authorizes school districts to offer first two years of postsecondary instruction to high school graduates.

|

|

1910

|

Superintendent of Fresno Schools establishes the state’s first junior (community) college, an extension of Fresno High School.

|

|

1921

|

Legislature permits voters to establish community college districts to administer community colleges. (Despite focus on postsecondary instruction, new districts remain under the authority of K–12 system’s State Board of Education.) Legislature passes separate statute (still in the Education Code) giving right of adult residents to ask for and receive English as a second language (ESL) and citizenship classes from school districts.

|

|

1941

|

Community colleges permitted to establish own evening (adult) programs.

|

|

1960

|

Donohoe Act recognizes community colleges as higher education segment (with state colleges and universities) but retains State Board of Education as CCC system’s governing board.

|

|

1968

|

Community colleges removed from State Board of Education governance and placed under authority of Board of Governors of the California Junior (later renamed “Community”) Colleges.

|

|

1970

|

All community colleges are legally separated from local school districts, replaced by community college districts.

|

|

1976

|

Statute assigns core adult education responsibilities (such as literacy and ESL) to school districts. School districts permitted to transfer instructional responsibility to community colleges by “mutual agreement.”

|

|

1991

|

Statute adds adult (noncredit) education as an “essential and important” mission of community colleges.

|

|

1994

|

Several school districts file lawsuit against CCC for offering adult education courses, contending that neighboring CCC districts have no legal right to do so absent mutual agreement with school districts.

|

|

1997

|

Court of Appeal rules that CCC districts do not need a mutual agreement to offer adult education, since the program is part of CCC’s mission. Both school and CCC districts permitted to provide adult education.

|

|

2009

|

The requirements governing adult education program and funding were made flexible for school districts—though not for CCC—through 2012–13 (since extended through 2014–15).

|

Junior Colleges Begin Offering Adult Education Too. Beginning in 1921, junior colleges started forming their own local boards apart from school districts, though many continued to be governed by school districts and all junior colleges remained under the authority of the State Board of Education (SBE). Junior colleges’ responsibilities expanded in 1941, when the Legislature authorized them to offer adult education. By the 1950s, over 300 adult schools existed in the state, with about 50 of them operated by junior colleges.

School Districts and Community Colleges Struggle Over Which Has Responsibility for Adult Education. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Legislature transferred state–level governance of the junior colleges (renamed “community colleges” shortly thereafter) from SBE to the colleges’ own systemwide Board of Governors (BOG), and all remaining colleges that had been run by school districts came under the authority of CCC districts. This split raised the question of which segment, school districts or community college districts, should have responsibility for the delivery of adult education. The Legislature sought to address this issue in 1976 by giving statutory responsibility for several core adult education programs—literacy, high school diploma and GED programs, English as a second language (ESL), and citizenship—to school districts. Community colleges were permitted to provide such instruction within the geographical area of a school district only if they obtained a formal agreement with the school district. Statute did not assign responsibility for the other instructional areas, such as vocational education, to one particular segment. Instead, school districts and community colleges had to reach a “mutual agreement.”

Often Responsibilities Ended Up Split Between School Districts and Community Colleges. School districts and community college districts responded to this legislative directive in various ways. In most cases, school districts took primary responsibility for literacy, high school diploma, ESL, and citizenship programs, with community colleges offering adult education–related instruction in areas such as vocational instruction and precollegiate (remedial) English and math coursework. In a few cases (such as in San Francisco and Santa Barbara), school districts gave up their right to run all adult education programs and the community college district became the sole local provider. In one case (San Diego), the school district and community college district agreed to offer a joint high school diploma program, with the community college district providing all other adult education instruction on its own.

School Districts and CCC Districts in Court Over Issue. In the 1990s, adult education was further complicated both by a change in statute and a subsequent lawsuit involving certain school districts and community college districts in Southern California. Specifically, in 1991 the Legislature changed law by adding adult education as a mission of the community colleges. Three years later, six school districts filed a lawsuit against three community college districts. The school districts contended that, pursuant to state law, their neighboring community colleges had no right to operate literacy, high school diploma, ESL, and citizenship programs because the colleges lacked a formal agreement with the school districts to do so. In its decision, the court observed that the 1976 legislation requiring such agreements and the 1991 statute that included adult education as a CCC mission were “irreconcilably inconsistent” with each other since “the requirement that [CCCs] obtain a mutual agreement before offering these programs . . . would interfere with the fulfillment of their mission.” The court concluded in its 1997 ruling that, based on its reading of current law, both school and community college districts have the “authority, power or right to offer the full range” of adult education programs within the same geographical area, regardless of whether they have a mutual agreement in place. The court noted, however, that the 1991 statute “contemplates that the community colleges will act conjointly or in unison with the school districts” to provide ESL and certain other adult education programs.

Lack of Clarity Continues. Since that time, the state has made some notable efforts to clarify adult–education governance in statute, but none has been implemented. For example, noting that the “conflicting statutes . . . cause confusion among adult schools and community colleges,” in 1998 a joint SBE and BOG task force called for “statewide clarification regarding both systems’ authority to offer . . . adult education in a coordinated way.” A few years later, the Davis administration’s initial budget proposed to place adult education under the community colleges, though the May Revision later rescinded the proposal. Thus, more than 40 years after the legal split of school districts and community colleges into separate segments, the state continues to leave unresolved fundamental issues of governance and coordination of adult education.

Adult Education Is Neither Segment’s Core Statutory Responsibility. While adult education falls under the purview of both community colleges and school districts, it is not the top statutory mission of either segment. The community college’s core mission is to provide academic and vocational programs at the lower–division collegiate level. School districts’ core statutory and constitutional responsibility is for kindergarten through high school (K–12). Furthermore, school districts are responsible for adult education only “to the extent” state support is provided.

Recently Adult Schools Signaled by State as Lower Priority. Adult schools’ lower priority within the K–12 system was reinforced by budgetary decisions made in February 2009. Prior to 2008–09, the state provided funding for adult schools though a categorical program and required school districts to use these monies for adult instruction. During a February 2009 special session, the Legislature removed the categorical program requirements and allowed school districts to use adult education funding (along with funding associated with a number of other categorical programs) for any educational purpose. As part of the change, the Legislature also exempted school districts from reporting and certain other statutory requirements pertaining to adult education. (This flexibility is authorized through 2014–15.)

Instructional Areas Overlap in Two Segments

Adult Education Encompasses a Number of Instructional Areas. While adult education’s initial focus was on basic academic and vocational skills, other categories of instruction were added and expanded over time. For example, in 1915 the Legislature authorized teachers to instruct adults in their own homes on food nutrition. With the growth of the state’s population after World War II, adult schools greatly expanded offerings in parenting education. Courses targeted to older adults began in the early 1950s. By 1982, the Legislature had settled on the ten state–supported instructional areas that are still authorized today.

Community Colleges Can Offer Courses on “Credit” or “Noncredit” Basis. Figure 2 shows that both adult schools and community colleges are authorized to offer courses in each of these ten instructional areas. The figure also shows that, in six of these ten categories, community colleges can offer instruction on a credit or noncredit basis. For example, community colleges can choose to offer ESL and “health and safety” instruction (which consists largely of exercise and fitness classes) as either credit or noncredit. In addition, community colleges offer a number of noncredit vocational courses and certificate programs (such as automotive repair, carpentry, certified nurse assisting, culinary arts, and welding) whose content is very similar to credit instruction. In fact, a few community colleges enroll both credit and noncredit vocational students in the same class. (Though many credit vocational courses are similar to noncredit vocational courses, credit vocational programs generally tend to be somewhat more advanced and longer in length.) The nearby box discusses the differences between credit and noncredit courses. It also explains the differences between credit degree applicable and credit non–degree applicable courses. (Confusingly, despite the name, not all credit courses give community college students academic credit they can apply toward graduation.)

Figure 2

Adult Education Includes a Wide Array of Instructional Areas

|

Instructional Area

|

Adult Schools

|

CCC Noncredit

|

CCC Credit

|

|

Adults with disabilities

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Apprenticeship

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Vocational educationa

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Immigrant education (citizenship and workforce preparation)

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

Elementary and secondary education

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

English as a second language

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Health and safetyb

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Home economics

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

Older adults

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

Parenting

|

X

|

X

|

|

Various Types of California Community College (CCC) Courses

Notable Differences Between Community College Credit and Noncredit. Though CCC credit and noncredit instruction overlap in many ways, they differ in five notable ways. First, depending on the course and college, students taking noncredit courses may be permitted to join or leave a class at any time during the term. Second, unlike credit courses, typically there is no restriction on the number of times students may reenroll in a noncredit course (which can be beneficial for underprepared students who need additional time to master course material). Third, CCC regulations generally require faculty to possess at least a master’s degree in order to teach a credit course (with exceptions made for certain vocational disciplines), but at least a bachelor’s degree for noncredit courses. Fourth, students are charged enrollment fees for CCC credit courses but not CCC noncredit courses. Lastly, the state funds noncredit courses at a lower rate than credit courses and calculates attendance differently.

Two Types of Credit Courses—Degree Applicable . . . Credit courses that count toward an associate degree are referred to as “credit degree applicable.” Community college regulations stipulate the types of credit coursework that can count toward an associate degree: (1) lower–division (freshman and sophomore) coursework that is transferable to the University of California or California State University systems and (2) non–transferable vocational courses that a college requires as part of its major requirements for an associate degree in a vocational field. Additionally, colleges can designate certain precollegiate–level math and English courses as credit degree applicable.

. . . And Non–Degree Applicable. The CCC regulations allow for a second type of credit instruction known as “non–degree applicable.” Whereas the units from credit degree–applicable courses count toward a student’s associate degree, units from credit non–degree–applicable courses do not. The CCC regulations give colleges considerable discretion as to whether they may offer precollegiate (adult education) math, English, and English-as-a-second-language courses as credit degree applicable or credit non–degree applicable. Community colleges receive the same funding rate regardless of whether a course is credit degree applicable or credit non–degree applicable.

Enrollment

More Than 400 State–Funded Entities Providing Adult Education. In 2011–12, about 300 adult schools (down from 335 in 2007–08, the year prior to flexibility) and 112 community colleges were operating throughout the state. Exactly how many students were enrolled in adult education programs, however, is unclear. This is because attendance data has become less and less complete in recent years. For adult schools, the California Department of Education (CDE) contracts with a nonprofit organization, Comprehensive Adult Student Assessment Systems (CASAS), to collect attendance data. Prior to the enactment of flexibility, every adult school reported attendance data to CASAS in all ten state–authorized instructional areas. In 2008–09 and 2009–10, the roughly half of adult schools receiving federal Workforce Investment Act (WIA) funding continued to report complete attendance data to CASAS, with the remaining schools generally submitting partial data or no data at all to CASAS. Enrollment data became even more incomplete in 2010–11 when CDE revised the CASAS contract to require WIA–funded schools to submit only attendance data for the three instructional areas applicable to the federal program (adult elementary education, adult secondary education, and ESL). In contrast to adult schools, the CCC Chancellor’s Office continues to collect complete attendance data from community colleges.

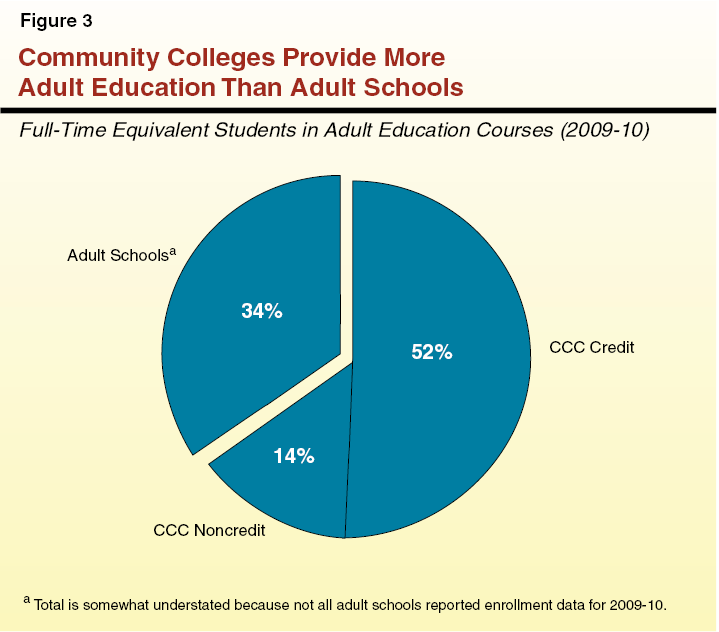

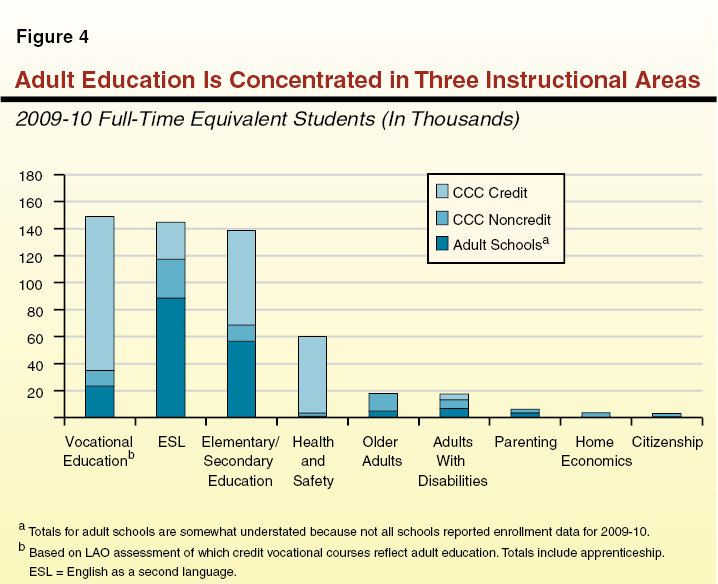

Estimate Over 1.5 Million Students Served in 2009–10. Though the data are incomplete, based upon the data from CASAS and CCC that are available, we estimate adult schools and community colleges provided adult education instruction to at least 1.5 million students (headcount) in 2009–10, which translates into about 550,000 full–time equivalent (FTE) students. (One FTE represents 525 instructional hours—reflecting one student taking a full load of coursework during an academic year. It is equivalent to the “average daily attendance” [ADA] measure used by school districts.) Figure 3 shows that community colleges provide the largest share of adult education in the state, primarily through its credit program. As Figure 4 details, vocational education is the largest adult education instructional area, with most of this instruction offered through the community colleges on a credit basis. English as a second language and adult elementary and secondary education (which includes remedial math and English) are the second and third most–offered adult education programs, respectively. Whereas most adult elementary and secondary instruction is provided by community colleges, ESL is more commonly taught by adult schools. Also, while health and safety is a relatively small instructional category for adult schools and CCC noncredit programs, it accounted for over 50,000 FTE students in the CCC credit program (in physical education classes such as yoga, pilates, and weight lifting).

A Few Community Colleges Have Large Noncredit Programs. Whereas all community colleges widely offer adult education instruction on a credit basis, only a handful of colleges offer a robust selection of noncredit adult education. The largest CCC noncredit providers are the Rancho Santiago (Orange County), San Francisco, San Diego, North Orange, Mount San Antonio (Los Angeles County), and Los Angeles districts. Together, these six districts accounted for two–thirds of total noncredit FTE students in 2011–12, with the top ten largest district providers accounting for about 85 percent of CCC noncredit instruction. (Data exclude enrollments in supervised tutoring.)

Funding

More Than $2 Billion Spent in 2011–12. As with enrollment, pinpointing the exact amount the state spends on adult education is not possible. This is primarily because school districts are not required to report to the state how they spend their now–flexible adult education monies. A rough estimate is that a total of $2.1 billion was spent on community colleges and adult schools in 2011–12 (all funding sources), of which about $1.7 billion supported community colleges and about $400 million supported adult schools. The largest funding sources are state General Fund and local property tax revenues—commonly known as Proposition 98 funding. The other major funding sources are student fees and federal funds.

Proposition 98 Funding

Prior to 2008–09, Adult Schools Funded Based on Attendance. Historically, funding for adult schools was based on ADA, with school districts receiving $2,645 in state funding per ADA in 2007–08. School district adult education programs had funding caps on the number of ADA they were paid for each year. Per statute (initially adopted in 1979–80), each district’s cap was increased by 2.5 percent annually. If a school district failed to reach its cap for two consecutive years, the amount of enrollment monies that went unused would be redirected to other districts serving students in excess of their funding caps. This redistributive approach was intended to help match school district allocations with statewide demand for adult education services.

Flexibility Has Had Significant Implications for Adult School Funding. Beginning in 2008–09, the state reduced funding for school districts due to declining revenues. That fiscal year, the state implemented a 15 percent across–the–board cut to adult education (the same reduction applied to the majority of other categorical programs). This cut deepened from 15 percent to 20 percent in 2009–10 and remained at that reduced level in 2010–11 and 2011–12. As discussed earlier, in a corresponding action, the state allowed school districts to use their adult education funding for any education purpose. The amount that has been redirected for K–12 purposes varies considerably among districts—from no funds in a few districts to the entire amount in others. Based on our survey of school districts, it is likely that only between 40 percent to 50 percent of the $635 million nominally provided in Proposition 98 adult education categorical funds actually is spent on adult education.

Three Funding Rates for CCC. Under current law and regulations, community colleges receive enrollment funding that can be used for both credit and noncredit instruction, with colleges independently deciding the combination of credit and noncredit enrollment they deem appropriate. These general–purpose monies (commonly known as apportionment funds) are provided to cover each campus’ basic operating costs for serving students. Under current law, there is one per–student funding rate for credit instruction and two per–student funding rates for noncredit instruction. These rates can be adjusted annually for a cost–of–living increase, though the last year of such an adjustment was in 2007–08. For both types of noncredit instruction, apportionment funding is calculated based on students’ daily course attendance (known as “positive attendance”). This is different from credit instruction, which is generally calculated based on the number of students enrolled in a course at a given point in the academic term (typically the third or fourth week). The funding rates are as follows:

- Credit. In 2012–13, the per–student funding rate for credit courses is $4,565. Colleges receive this funding rate regardless of whether the coursework is degree–applicable or non–degree applicable.

- “Enhanced” Noncredit. Chapter 631, Statutes of 2006 (SB 361, Scott), established an enhanced funding rate for noncredit “career development and college preparation” (CDCP) courses that lead to noncredit certificates (such as a certificate of completion in medical assisting). The 2006–07 Budget Act included $30 million in base funding toward the enhanced noncredit rate. The CDCP courses, which include noncredit elementary and secondary education, ESL, and vocational instruction, receive $3,232 per FTE student in 2012–13.

- Regular Noncredit. All other noncredit courses (such as home economics and programs designed for older adults) receive $2,745 per FTE student in 2012–13.

Budget Cuts Have Resulted in Smaller Adult Education Program for CCC. Over the past few years the state’s economic and fiscal situation has resulted in a considerable reduction to community colleges’ funding levels. Although not reduced in 2008–09, the 2009–10 budget package reduced CCC base apportionments by $190 million (3.3 percent). To balance their local budgets, community colleges responded by cutting course sections. Course sections were further reduced in 2011–12 as a result of additional budget cuts that year. Many districts have targeted noncredit instruction for a disproportionate share of cuts. Statewide, the number of noncredit FTE students served in 2011–12 was about 30 percent lower compared with 2008–09 levels. These reductions were focused primarily on regular noncredit instruction (as opposed to CDCP programs).

Student Fees

Two State Policies on Student Fees for CCC Courses . . . The state has two policies with regard to fees for CCC students enrolled in adult education. Under current law, community colleges are prohibited from charging a fee for any noncredit instruction. By contrast, a fee is charged for credit instruction (which increased to $46 per unit, from $36 per unit, in July 2012), though financially needy students qualify for a fee waiver. In 2011–12, community colleges collected a total of $360 million in enrollment fees. The community colleges do not disaggregate fee revenue associated with individual programs or courses. Given that adult education–related instruction accounts for roughly one–quarter of total credit instruction, it is likely that fee revenue for this type of instruction was about $100 million in 2011–12.

. . . Also Multiple Policies on Student Fees for Adult Schools. Until recently, adult schools were prohibited from charging fees for ESL and citizenship classes, as well as adult elementary and secondary education. Chapter 606, Statutes of 2011 (AB 189, Eng), amended the law to allow adult schools to charge a fee for ESL and citizenship (but not for adult elementary or secondary education) through 2014–15. As they have in the past, adult schools continue to be permitted to charge adults a fee for vocational courses and the other instructional areas (such as parenting classes). Current law does not specify a specific fee level that may be charged, but the fee cannot exceed the amount it costs adult schools to offer the course. The amount of fee revenue that was collected by adult schools in 2011–12 is unknown but is likely to total in the low tens of millions of dollars. Figure 5 summarizes the state’s various fee policies.

Figure 5

The State Has Multiple Fee Policies for Adult Education

|

|

Adult Schools

|

CCC Noncredit

|

CCC Credit

|

|

English as a second language

|

Fee permitted (varies)

|

No fee permitted

|

$46/unit

|

|

Citizenship

|

Fee permitted (varies)

|

No fee permitted

|

N/A

|

|

Elementary and secondary education

|

No fee permitted

|

No fee permitted

|

$46/unit

|

|

Vocational education

|

Fee permitted (varies)

|

No fee permitted

|

$46/unit

|

|

Other (such as health and safety)

|

Fee permitted (varies)

|

No fee permitted

|

$46/unit

|

Federal Funds

Federal Funds Supplement Many Providers’ Budgets. A primary source of federal funding for adult education is WIA Title II. The state was allocated $91 million in WIA funding for 2011–12 to support instruction in adult elementary education, adult secondary education, and ESL—the instructional areas authorized under the act. A total of 169 adult schools ($59 million), 17 community colleges with noncredit programs ($13 million), and 38 other providers such as libraries and community–based organizations ($7 million) received WIA funding. (The remaining $12 million in WIA funding is retained by CDE to administer the federal program, as well as to support statewide activities such as professional development.) Pursuant to CDE policy, only providers that submitted successful applications in 2005 are eligible to receive this funding. (The CDE plans to reopen the grant to new applicants beginning in 2013–14.)

State Allocates Federal Adult Education Funds to Providers Based on Performance. Although the federal government does not require it, CDE allocates funds to educational providers using a pay–for–performance mechanism. Under the outcomes–based approach, specified student outcomes earn a provider performance points. For example, adult education programs earn points each time a student attains a high school diploma or GED or when a student’s score improves by a set amount on literacy pre– and post–tests. The CDE then takes the WIA grant and divides the funding by the total points earned across participating adult education programs to determine a per–point rate. Grants are determined by multiplying the per–point rate by the number of points earned by a particular provider. This approach is meant to create a strong incentive for providers to deliver services that improve academic performance and program completion rates. Beginning in 2013–14, CDE plans to introduce additional performance measures that track student transitions from adult education to postsecondary studies and the workforce. The intent is to reward providers not just for their students’ success in adult education but also for developing partnerships and pathways that advance individual and societal goals of continued education and successful job placement.

Federal Perkins Funds Support Vocational Instruction. In addition to WIA funding, both adult schools and community colleges receive federal Perkins funding to support vocational programs. Unlike WIA Title II, Perkins monies are distributed to educational providers through formula allocation (based on student enrollment). In 2011–12, adult schools and community colleges received $8 million and $55 million in Perkins funds, respectively. Providers can use these funds for a number of purposes, including curriculum and professional development and the acquisition of equipment and supplies for the classroom.

Data and Accountability

State Receives Comprehensive Data on Certain Adult Schools. Though the federal government only requires states to collect demographic and student performance data for providers receiving WIA funding, for years CDE used the federal data infrastructure to collect data from all adult schools in the state. That is, until flexibility was adopted in 2009, adult schools were required to supply CASAS with various data (including student enrollment, demographics, labor force status, and certain student outcomes) as a condition of receiving categorical funds. As noted earlier, however, data on adult schools has been incomplete since that time.

CCC Chancellor’s Office Collects Own Set of Data. In addition to the federal accountability requirements discussed above, the state requires CCC to collect and report on a wide range of data pertaining to its educational programs. Pursuant to statutory requirements, the CCC Chancellor’s Office releases an annual report known as Accountability Reporting for the Community Colleges (ARCC). The ARCC includes certain system and campus–level demographic and performance data over multiple years, primarily in credit coursework. The report includes completion rates in vocational courses, fall–to–fall persistence rates, and other metrics. The Chancellor’s Office also produces an annual performance report that focuses exclusively on students in credit and noncredit basic skills and ESL instruction (such as the percentage of underprepared students who eventually obtain an associate degree) and a separate report with wage data and persistence rates of students enrolled in CDCP noncredit courses.

Student Outcomes Comparable at Adult Schools and CCC Noncredit. While the state lacks a single data system that allows for comprehensive comparisons between students at adult schools and community colleges, CASAS data can supply insights into comparative student outcomes. The CASAS recently analyzed all adult students who took an adult elementary, adult secondary, or ESL course at a WIA Title II–funded adult school or community college during 2005–06. The study tracked the cohort over a three–year period to determine the extent to which students’ learning increased (as demonstrated by either improving their standardized–test results a certain number of points or advancing to a higher instructional level). The data indicate that the students in adult schools and community college noncredit programs generally had similar demographic characteristics (such as age, gender, and ethnicity) and performed nearly equally. For example, about half of students in each segment’s cohort advanced at least one instructional level during the three–year period, with another 40 percent of students showing learning gains within the same instructional level. About 10 percent of students in each segment did not demonstrate any notable progress.

Assessment of the State’s Adult Education System

Review Finds Some Key Strengths but Many Weaknesses. Our review finds that California’s adult education system possesses some key strengths. These include having two large segments with extensive experience working with adult learners throughout the state. Adult education also has a data system that can measure learning gains for at least some students and an innovative state policy that allocates federal funds to providers based on performance. Our review, however, also has identified a number of major problems and challenges with the current system, as summarized in Figure 6. Specifically, we have concerns with the adult education system’s: (1) overly broad mission; (2) lack of clear delineation between precollegiate and collegiate studies at CCC; (3) inconsistent state–level policies; (4) widespread lack of coordination among providers; and (5) limited data, which makes oversight difficult.

Figure 6

California’s Adult Education System Has a Number of Problems

- Adult education has overly broad mission.

|

- Community colleges lack clear and consistent lines between precollegiate and collegiate education.

|

- Providers are subject to inconsistent rules by the state.

|

- Inter–agency coordination is limited.

|

- Gaps in data systems make oversight difficult.

|

Adult Education Mission Overly Broad

Some Programs Are Not Aligned With State’s Highest Educational Priorities. Several of the current categories of instruction (such as adult elementary education, adult secondary education, ESL, and vocational education) generally are centered around the core goal of providing students with the foundational education and skills they need to participate effectively in society and the workforce. The state currently authorizes other instructional categories, however, that serve various other vaguely defined and unrelated purposes, such as “programs for older adults” and “programs in home economics.” While these classes can be of value, they can have the effect of stretching finite levels of state resources. This, in turn, reduces the amount of instruction that is available to advance the state’s highest priorities of civic engagement and economic growth.

CCC Lacks Clear and Consistent Lines Between Adult Education and Collegiate Education

CCC Funding System Creates Incentives to Offer Certain Precollegiate Material on Credit Basis. Currently, neither state law nor CCC regulations establish a minimum level for credit coursework in math, English, and ESL (in contrast to other academic disciplines such as history and science, which must be transferable to the University of California [UC] or the California State University [CSU] to be offered on a credit basis). As a result, credit instruction in remedial math and English can be less advanced than noncredit instruction (or instruction offered by an adult school) in the same discipline. Based on our discussions with CCC, the major factor in colleges’ decision to provide math, English, and ESL on a credit basis (as opposed to noncredit) often boils down to the higher funding rate districts receive for credit instruction. Given the lack of a floor on credit instructional levels, colleges have a strong financial incentive to offer adult education–level material on a credit basis, regardless of actual course costs or whether it is the best fit for students.

CCC Lacks Common Definition of Degree–Applicable Coursework. Not only are community colleges permitted to claim the credit funding rate for precollegiate–level instruction in math, English, and ESL, they also have considerable flexibility to count these courses as degree applicable. For example, CCC regulations allow colleges to award students credit toward an associate degree for Elementary Algebra, which is a course commonly taken by high school freshmen. Colleges also can choose whether to give credit toward an associate degree for even the lowest–level ESL courses. In effect, then, colleges within the same system have different definitions of what is adult education (precollegiate instruction) and what is collegiate instruction.

No Clear Basis for Delineating Vocational Programs as Credit or Noncredit. The state also provides little guidance to community colleges with regard to whether vocational courses are offered on a credit or noncredit basis. As a result, the distinction between credit and noncredit vocational education is locally determined and inconsistent across the state. Statute authorizes adult schools and community colleges to offer noncredit vocational training that is “short–term” in nature (typically understood as a program that is one year or less in length). Community colleges, however, routinely offer short–term programs on a credit basis too. In 2011–12, for example, over half of credit certificates awarded to students were for programs of fewer than 30 units (the equivalent of one full year of coursework). Some community colleges award certificates to students who complete as little as six units of credit (the equivalent of two courses). And, as mentioned earlier, some colleges also place credit and noncredit students in the same vocational class. These practices raise a question about why the state provides two different funding rates for what can amount to similar or the same instructional content.

Inconsistent State–Level Policies

Though adult schools and CCC generally cover the same geographic areas, statutes have created two markedly different systems operating within the same state.

Faculty Subject to Different Qualification Requirements. Despite teaching similar or identical content to adult students, instructors from adult schools and community colleges are subject to different minimum qualifications for employment. Whereas both adult schools and community colleges generally require instructors to have a bachelor’s degree or higher, statute requires adult–school instructors also to be credentialed by the Commission on Teacher Credentialing.

Students Can Be Subjected to Different Fee Levels for Similar Programs. Whereas the Legislature does not allow CCC to charge for noncredit coursework (and sets a specified fee level for credit instruction), for years the Legislature has permitted multiple fee policies for adult schools, including allowing them to charge up to the full cost of instruction for vocational and certain other instructional programs. As discussed earlier, in 2011 the state enacted Chapter 606, which authorizes adult schools to offer ESL instruction for a fee. While the purpose of the law is to enable adult schools to maintain courses they may otherwise have to cancel due to a lack of state funding, the policy raises the question of why it is permissible to charge a fee to English learners taking an ESL class but not to native English speakers taking a literacy class through an adult elementary education program. (Inconsistencies also exist for funding policies, which are addressed later.)

Providers’ Assessment and Placement Policies Are in Conflict. State law allows adult schools and community colleges to require entering students to undergo assessment to determine their level of proficiency in math and English. Whereas adult schools can use any assessment instrument they deem appropriate, community colleges can only use assessment instruments (typically standardized tests) that have been approved by their state governing body (the BOG). In addition, current law requires assessment results for CCC students—but not adult school students—to be nonbinding. That is, CCC cannot prevent students from enrolling in an educational program based on their assessment score. Instead, students are free to take any courses that do not carry a math or English prerequisite—which includes most course offerings at CCC. Conversely, adult schools have a widespread practice of requiring prospective students to obtain a certain score on an assessment test in order to be admitted into a vocational program.

Missed Opportunities for Collaboration

Both CCC and Adult Schools Have Strengths. In our view, both community colleges and adult schools have comparative advantages for delivering adult education. The 112 colleges that make up the CCC system focus on adult learners almost exclusively and provide a continuum of education and training through the sophomore year of college. Adult schools, meanwhile, are spread even more widely across the state—even with recent budget cuts, there are about 300 adult schools. They also often provide instruction that is very accessible to adult learners. For example, some adult education programs are run at elementary schools, such that parents can take classes at the same time and location as their children. Individual providers can possess differing strengths too. For instance, even before flexibility, a number of adult schools had large high school diploma and GED programs but offered minimal (if any) vocational training. Conversely, many CCCs have robust vocational programs but relatively few (currently just 12 of 72 districts) have high school diploma programs. Although both providers offer ESL, adult schools often provide less advanced levels of instruction of ESL than community colleges.

Inter–Segmental Coordination Beneficial for Students . . . In some cases, adult schools and neighboring community colleges have managed to form working partnerships that leverage these differing strengths and capabilities. These collaborations can take different forms. For example, some school and CCC administrators have created aligned course sequences so that students can move seamlessly from lower levels of ESL at adult schools to increasingly more–advanced levels at a community college. In other cases, instructors from adult schools and neighboring community colleges have created articulation agreements for comparable courses. This allows students who successfully complete a course or set of courses at an adult school to receive credit toward an associate degree or certificate upon their enrollment at a community college.

. . . But Survey Results Indicate Such Coordination Is Not Extensive. While examples of coordination exist throughout the state, too often the two agencies work independently from one another at the local level. For example, 48 percent of CCC respondents to a survey we conducted in July 2011 indicated that they do not coordinate with any adult schools to provide aligned pathways for adult school students to continue their studies at their college. (Another 42 percent reported that they do coordinate to provide such pathways. The remaining 10 percent of respondents were unsure whether their college coordinated in this way.) In addition, 52 percent of respondents reported that their college does not articulate comparable courses with adult schools. (Another 23 percent of respondents reported that they did articulate at least some courses. The remaining 25 percent were either unsure or indicated that they did not offer courses that were comparable with those of adult schools.) The adult schools we surveyed indicated similar responses. This lack of articulation means that a student may have completed a course at an adult school yet would not receive credit for it at the community college even if the two courses were identical.

Multiple Factors Inhibit Cooperation. In our discussions with adult schools and community colleges, a number of faculty and administrators indicated that the lack of a statewide or regional structure for articulation inhibits the ability of providers to develop such cooperative agreements. For example, currently there is no formal program or body in place for faculty from adult schools and community colleges to engage in ongoing dialogue on curriculum and standards. In addition, because course titles vary by provider, identifying comparable courses at adult schools and community colleges can be difficult and cumbersome for instructors. Many also remarked that the state’s adult education system lacks strong incentives for providers to collaborate. To the contrary, funding based on “seat time” has historically created a sense of competition among providers and created a disincentive to coordinate their services.

Data and Accountability Systems Are of Limited Utility

Each Data System Has Pros and Cons. As discussed in the previous section, data pertaining to adult education in the state is collected and maintained by two primary organizations: CASAS and the CCC Chancellor’s Office. Each organization’s data system has core strengths, as well as notable shortcomings. The major capabilities of CASAS’ and CCC’s data systems—as summarized in Figure 7—are:

- CASAS Data System. A major strength of CASAS is that the system collects data on student learning gains and high school diplomas (and their equivalent) earned by students. A major shortcoming of CASAS is that since flexibility was enacted, it only collects data from providers that receive WIA funds. Another shortcoming is that CASAS does not collect any information on vocational education (such as the number of skills certificates earned by students).

- CCC Data System. The CCC Chancellor’s Office maintains a data system that, in some ways, has opposite strengths and shortcomings to CASAS’ system. A strength of the CCC data system is that it maintains complete enrollment information on community colleges. Another strength is that the Chancellor’s Office’s information system links with the Employment Development Department (EDD) to obtain wage data on former CCC students who have entered the workforce. A notable shortcoming is that, unlike CASAS, the CCC data system does not collect information on student learning gains. In addition, our review finds that only a handful of colleges offering CDCP noncredit courses report to the Chancellor’s Office the annual number of noncredit awards earned by students (such as high school diplomas and vocational certificates), which renders the CCC data system of limited utility for assessing the segment’s overall contribution to adult education.

Figure 7

Two Data Systems Collect Different Types of Information

|

|

CASAS

|

CCC MIS

|

|

Data Element:

|

|

|

|

Student enrollment?

|

Limiteda

|

Yes

|

|

Course grades?

|

No

|

Credit courses onlyb

|

|

Learning gains?

|

Yesa

|

No

|

|

High school diplomas earned?

|

Yesa

|

Limitedc

|

|

Vocational certificates earned?

|

No

|

Limitedc

|

|

Linked with EDD wage data?

|

No

|

Yes

|

Data Systems Are Not Coordinated. Another notable issue is that the two data systems are incapable of data matching because community colleges and adult schools use different student identification numbers. This makes tracking student transfers from adult schools to CCC (or other postsecondary institutions) and the labor market difficult. In fact, currently adult schools must rely on surveying former adult school students to determine whether they have moved on to college, obtained a CCC degree or certificate, or entered the workforce. (Survey return rates are typically very low.) Because the two data systems are not linked, they are of limited value to researchers, policymakers, and practitioners.

LAO Recommendations

Challenges Facing Adult Education Are Numerous and Growing. As described above, even before recent budget cuts and the removal of categorical spending requirements, the state’s system of adult education was characterized by a myriad of challenges. Adult education encompasses many instructional categories—several of which are ill–defined and unrelated to the traditional focus on providing adults with basic language and job skills. In addition, fundamental terms and policies related to adult education lack consistency and coherence. Furthermore, coordination and accountability are uneven. Since budget cuts and flexibility, adult education has become a program adrift. Community colleges and, in particular, school districts have cut enrollment funding, which likely has resulted in a significant amount of unmet demand.

Adult Education in Need of Comprehensive Restructuring. Given all these challenges, we believe adult education is in need of comprehensive restructuring. We also believe the Legislature has an important role in guiding the development of a new system. Below, we lay out a vision and roadmap for a more rational, coordinated, and responsive system with both adult schools and CCC as providers. Our recommendations include the creation of: (1) a state–subsidized system focused on adult education’s core mission; (2) common, statewide definitions that clearly differentiate between adult education and college education; (3) a common set of policies relating to faculty qualifications, fees, and student assessment; (4) a dedicated stream of funding that fosters cooperation between adult schools and community colleges; and (5) an integrated data system that tracks student outcomes and helps the public hold providers accountable for results. Figure 8 summarizes our recommendations.

Figure 8

A Roadmap to Restructuring California’s Adult Education System: Summary of LAO Recommendations

|

|

|

Focus State Support on Core Adult Education Mission

|

- Reduce number of authorized state–supported instructional programs from ten to six: (1) adult elementary and secondary education, (2) English as a second language (ESL), (3) citizenship and workforce preparation, (4) vocational education, (5) apprenticeship, and (6) adults with disabilities.

|

|

Provide a Clear and Consistent Distinction at California Community Colleges (CCC) Between Adult Education and Collegiate Instruction

|

- Restrict credit instruction in English and ESL to transfer–level coursework, and credit instruction in math to one level below transfer. Require courses below these levels to be offered on a noncredit basis.

|

- Convene a work group to advise the Legislature and CCC Board of Governors on the appropriate delineation between adult education (noncredit) and collegiate instruction (credit) for vocational education.

|

|

Resolve Inconsistent and Conflicting Adult Education Policies

|

- No longer require instructors at adult schools to hold a teaching credential so that adult education faculty can teach at both adult schools and community colleges.

|

- Establish an enrollment fee (such as $25 per course) for students taking adult education courses through adult schools or CCC.

|

- Allow CCC faculty to place students into adult education courses based on assessment results (as faculty at adult schools currently are permitted to do). Require that adult schools use only assessment instruments that have been evaluated and approved for placement purposes (as community colleges currently are required to do).

|

|

Create a New Funding Mechanism for Adult Education

|

- Fund adult education as a separate item within school district budgets.

|

- Provide adult schools with the same noncredit funding rate that CCC districts receive.

|

- Allocate base adult education funds on combination of enrollment and performance.

|

- Allocate new funds for adult education based on regional needs.

|

- Promote collaboration among providers by adopting common course numbering for adult education.

|

|

Promote a Coordinated Data System

|

- Clarify legislative intent that adult schools and CCC use common student identification numbers.

|

Several Reasons to Start Transitioning to New System Now. Given that the state’s existing adult education system is both complex and riddled with serious shortcomings, we recommend the Legislature get started immediately in moving toward a better system—particularly as the transition to a better system likely will entail many steps and take several years to implement fully. Given that many of our recommended changes could be adopted without incurring additional costs, we recommend the Legislature begin implementing at least some components of a better system in 2013–14 regardless of the state’s fiscal condition. By taking at least a few steps immediately, the foundation for a more rational, efficient, effective, and better coordinated system would be in place in the event that the state has new funds to invest in adult education in future years. As discussed below, the first steps involved in restructuring are to narrow adult education’s focus and develop a clearer delineation between adult education and college–level instruction.

Focus Adult Education on Core Mission

Though many types of instruction can be of value to students, we believe the ten statutorily permitted instructional areas of adult education are not all of equal value. Rather, the most important programs in adult education are those that provide the knowledge and skills students need to participate in civic life and the workforce. Going forward, we recommend the Legislature focus state support on programs that advance this core mission. Specifically, we recommend the state support adult elementary and secondary education, ESL, citizenship and workforce preparation, and vocational education—including apprenticeship. (Because of their focus on basic skills and employment preparation, we recommend courses for adults with disabilities also continue to be eligible for state support.) Although school districts and community college districts would not be able to claim apportionments for instruction that fall outside these core areas, adult schools and CCCs could still provide opportunities for students to take these other classes (as many already do) through “community services education,” which are fully supported by student fees. Alternatively, individuals could participate in these programs through other local providers, such as senior centers and city parks and recreation departments.

Establish Clear Line Between Adult Education and Collegiate Education at CCC

Recommend Establishing Clear Distinctions Between Precollegiate and Collegiate Instruction. We recommend the Legislature create consistent rules and terms that clearly distinguish adult education (precollegiate) coursework in math, English, and ESL from collegiate coursework—as is already the case for other academic subjects such as history and science. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature restrict credit instruction in English and ESL to transfer–level coursework within those disciplines. Under our recommendation, English and ESL courses that are precollegiate (below transfer level) would only be offered on a noncredit (and thus non–degree applicable) basis. (Reclassifying such coursework as noncredit would have no material effect on students’ eligibility for state and federal financial aid such as Cal Grants, Pell Grants, and federal loans.) Although UC and CSU consider Intermediate Algebra to be one level below transfer math, we recommend the Legislature make an exception and permit community colleges to offer the course on a credit basis. This is because community colleges consider Intermediate Algebra to be “college level” given that it is a systemwide graduation requirement for any student seeking an associate degree. As a result of shifting certain precollegiate–level coursework from credit to noncredit, districts would be eligible for less apportionment funding. The Legislature could decide to keep CCC funding at the same level, however, which would allow colleges to accommodate additional students.

Recommend the Legislature Convene Work Group on Credit and Noncredit Vocational Education. In our view, credit coursework generally should include instructional content that requires students to possess and demonstrate college–level knowledge and skills, whereas noncredit content should be accessible for less–advanced students. Given that there are currently no common standards for what is collegiate and precollegiate vocational coursework, we recommend the Legislature convene a work group of experts to address the issue. The work group could consist of vocational as well as math and English educators. The group could be required to consult with industry representatives to help identify the level of skills needed for various vocational programs. Based on the work group’s findings, the Legislature could clarify through statute the definition of credit and noncredit vocational education. This, in turn, would assist the BOG in adopting more–detailed regulations on the appropriate division of the two types of instruction.

Adopt Consistent Policies on Faculty Qualifications, Fees, and Assessment

To further achieve consistency of standards for providers and students, we recommend the Legislature address policy differences between adult schools and community colleges in several issue areas.

Establish Consistent Qualifications for Faculty. We recommend the Legislature amend statute so that individuals no longer need a teaching credential to serve as an instructors at an adult school. By aligning policy for adult schools with that of the community colleges, instructors could readily teach adult education courses with both providers.

Adopt Consistent Policy for Enrollment Fees. Over the years, the state has adopted different fee structures for adult schools and community colleges. In order to create a more integrated system, we believe the Legislature needs to reconcile these differences and devise a consistent fee policy. We believe that certain social benefits—such as a population better able to support itself and a better–informed electorate—justify an investment by the state’s taxpayers in adult education. At the same time, however, students derive personal benefits from their education and training, and in many cases these benefits show up in the form of higher earnings. Consequently, it is not unreasonable, we believe, to expect the recipients of these benefits to bear a proportion of the costs involved in educating them. Fees can cause positive behavioral tendencies in students too—such as making them more deliberate in their selection of courses and more purposeful about holding campuses accountable for providing high–quality services. It is important, though, that fee policies are structured so that students’ financial circumstances do not limit their educational opportunities. We thus recommend the Legislature consider levying a modest enrollment fee (such as $25 per course) for students in adult schools and noncredit CCC programs.

Align Student Assessment and Placement Policies. We also recommend the Legislature address conflicting state policies with regard to the assessment and placement of students. As we discuss in Back to Basics: Improving College Readiness of Community College Students (June 2008), most research concludes that incoming students should be assessed prior to enrolling in classes. Studies also generally recommend that, based on assessment results, colleges should mandate placement of students into coursework that is appropriate for their skill level. To enhance student success, we thus recommend the Legislature amend statute to allow CCC faculty to place students in courses and programs based on assessment results. This would align CCC’s policy with that of adult schools. In addition, to ensure that reliable assessment instruments are used, we recommend the Legislature require adult schools to use tests that have been pre–approved by a state agency such as SBE or BOG. This would align policy for adult schools with that of the community colleges.

Create Funding Mechanism That Promotes Coordinated System

Along with adopting common terms and reconciling disparate policies, the state will need to decide on a funding mechanism for adult education. In our view, such a mechanism should balance the goal of providing stable, predictable funding so providers can plan for the future while also fostering innovation and collaboration to maximize access and student success. As discussed in more detail below, we envision a financing mechanism that includes a dedicated stream of funding for adult education, provides the same funding rate for the same instruction, rewards providers for student success, and aligns future allocations with program need.

Fund Adult Schools as a Separate Budget Item. To help rebuild and restructure the state’s system of adult education, we recommend the Legislature create a separate line item for adult schools. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature restore adult education as a stand–alone categorical program once flexibility sunsets at the end of 2014–15. Given that virtually all school districts have redirected at least some of these categorical funds to cover K–12 instructional costs, the Legislature will face a transitional issue regarding whether districts will be required to resume spending their entire pre–flex categorical allocation on adult education. While such a requirement would benefit adult education services, it also would create a funding shortfall for the non–adult education programs that currently are supported by the flexed funds. To minimize such a disruption, we recommend the Legislature require districts to spend on adult education in 2015–16 whatever they spent on the program in a specified prior year (such as in 2012–13). Such a categorical program is not needed for CCC because colleges already itemize their expenditures by type of instruction. This makes it easy to identify how much community colleges spend on adult education.

Equalize Funding Rate for Adult Education. Once flexibility ends, we also believe the Legislature should make equalizing per–student funding rates across the two segments a priority. Specifically, we recommend providing adult schools with the same funding rate that community colleges receive to provide adult education (noncredit) instruction. In most cases, providers would receive the enhanced noncredit rate (though instruction in citizenship and adults with disabilities would receive the regular noncredit rate, consistent with current practice). Equalization could be under taken in a few different ways, including providing a special appropriation for this purpose or providing higher cost–of–living adjustments to adult schools in future years.

Allocate Base Apportionments on Combination of Enrollment and Performance. Initially, we recommend the Legislature fund districts’ base apportionments entirely on actual instructional hours (consistent with traditional practice). After a short transitional period, we recommend the Legislature phase in a pay–for–performance component that would comprise a specified percentage of total apportionments that adult schools and community colleges receive for adult education (such as at least 10 percent at full implementation). We envision the state allocating these performance funds in largely the same way that WIA Title II funds go out to adult education providers. (As with WIA Title II funding, these funds would be based on performance in a prior year such that no delay would occur in their distribution to providers.) Since WIA does not fund vocational education, one notable difference would be that providers also would receive points for vocational certificates earned by students. By funding both enrollment and outcomes, the state would create a strong incentive for adult schools and CCC to provide educational access for students while at the same time focusing on strategies that improve student learning and successful transitions to collegiate studies and the workforce.

Assess Regions’ Relative Funding Needs. After multiple years of budget cuts and categorical flexibility, considerable variation exists at the local level in terms of the availability of adult education instruction. In years in which the state has new Proposition 98 monies to invest, we recommend a process whereby local areas are eligible for funds based on relative need. To assess local needs, we recommend the enactment of legislation that requires a state agency (such as the Department of Finance) to report annually how much in state funds are being provided for adult education by geographic area. Using census data, the state could then estimate relative funding needs. For each county, for example, the state could calculate the amount of adult education funding currently provided per adult with less than a high school diploma and per adult who does not speak English at home. Other indicators of need could include regional unemployment and poverty rates.

Make New Funding Available on a Regional Basis. Based on these calculations and the availability of state funding, the state could determine a region’s eligibility for additional adult education funding. (In general, we think counties are a reasonable proxy for a regional approach, though heavily populated counties could be divided into multiple regions, and multiple counties with relatively small populations could be combined into a single region.) Any existing or potentially new provider (including adult schools and community colleges) would be eligible to apply for these funds. In areas in which both school districts and community colleges offer adult education, providers would be permitted to apply for these new regional monies on their own (that is, without including any other partners in the application). Providers would have an incentive to apply with others, however, because applications would be awarded on a competitive basis and evaluated based on statutorily define criteria. For example, applications could be scored and ranked based on their inclusion of details, such as:

- The role each provider would have in providing instruction and services to students.

- The educational programs and student support services (such as counseling) that would be offered within the region.

- The proposed location of educational sites within the region and the extent to which the sites are accessible to populations in need of adult education.

- Courses the providers have sequenced and aligned career pathways they have in place (such as from adult elementary education to high school diploma programs and high school diploma programs to short–term vocational training and CCC credit programs).

- Partnerships that have been developed with other workforce–related agencies (such as business and labor organizations) in the region.

Task CCC, SBE, and a Third Agency With Evaluating Applications. We recommend the Legislature charge the CCC Chancellor’s Office and SBE with scoring and ranking the applications. In cases in which CCC and SBE do not agree on the winning application, we recommend the Legislature task a third–party agency (such as EDD) with breaking the tie. Once these additional monies are awarded, they would roll into the providers’ respective base budgets.

Promote Collaboration Among Providers by Adopting Common Course Numbering for Adult Education. To facilitate the creation of coordinated course sequences and seamless career pathways among providers, we recommend the Legislature support the development of a common course numbering system for adult education. We envision a system along the lines of what is already in place for the CCC and CSU systems. Specifically, to implement recent legislation requiring CCC and CSU to create streamlined pathways for transfer students, faculty from both segments have collaborated to develop a common course numbering system (known as “C–ID”) for hundreds of the most commonly taken courses by undergraduate students. Courses that meet the curricular standards of discipline faculty are given a C–ID number. (For example, all approved college–level algebra courses are designated C–ID MATH 150.) The C–ID designation provides assurance to faculty that a course taken by students at one campus is comparable elsewhere, which significantly simplifies the articulation process. The C–ID designation also provides CCC faculty with the building blocks for creating associate degree programs that are properly aligned with more–advanced coursework at CSU. (For more details on C–ID, please see Reforming the State’s Transfer Process: A Progress Report on Senate Bill 1440, May 2012.) The CCC Academic Senate has recently indicated that it has preliminary plans to use a similar approach to improve alignment and articulation of vocational courses between high schools and CCC associate degree programs. Going forward, we recommend the Legislature support the inclusion of adult education providers in this proposed effort. The Legislature could do so by providing special grant monies (such as through the Proposition 98–funded Career Technical Education Pathways Initiative) that allow faculty from adult schools and community colleges to meet and identify comparable vocational courses. We believe it also makes sense to adopt a common course numbering system for non–vocational instruction (such as ESL). In so doing, adult education providers within a given region would be better able to coordinate on the academic and vocational courses that each offers (to avoid unnecessary duplication) as well as to design clear pathways that facilitate the transition of students from adult education (noncredit) to coursework at the collegiate level.

Monitor Provider Performance With Linked Data System

Legislature Needs More Data to Exercise Its Oversight Function. Our proposed funding mechanism would require a much more robust data system than what is currently in place. For example, in addition to enrollment data, the state would need CASAS to collect outcomes data (such as learning gains) for all adult schools and community colleges—not just those that receive WIA monies. Community colleges, meanwhile, would need to start reporting complete data on the number of noncredit certificates earned by students. Without key data such as these, the Legislature would continue to have significant difficulty holding providers accountable for their use of state funds. By incorporating performance into the funding mechanism, however, we believe that both segments would have a strong incentive to ensure that such information is collected and reported to the state.

Adopt Common Student Identifiers to Improve Accountability. To further improve accountability, the state also will need a better way to track students as they move from one segment to the other. As noted in the previous section, a major obstacle to implementing a coordinated data system is the lack of uniform identification numbers for students in adult schools and the CCC system. While community colleges and other postsecondary institutions collect and use students’ social security numbers, CDE policy prohibits all schools from doing so (regardless of whether they serve children or adults). We recommend the Legislature request CDE to review its current policy for adult students. Depending on the outcome of CDE’s review, the Legislature could further clarify in statute its intent that adult schools and community colleges use students’ social security numbers to better facilitate the tracking of students across segments and into the labor force.

Conclusion

Adult education occupies a unique place in the state’s education continuum between K–12 and higher education in that it serves adult learners but consists of subject matter at the elementary and secondary level. Adult education plays an important role in providing adults with the basic skills and training they need to participate in civic life and become economically self–sufficient. Yet, a century and a half after the founding of the first adult school in California, adult education faces a number of major problems and challenges. In this report, we lay out a roadmap for restructuring the system. Taken together, we believe our recommendations would improve adult education by making it more focused, coherent, collaborative, responsive to local needs, and accountable to the public.