Executive Summary

The 1992 legislation that authorized charter schools in California created a funding model intended to provide charter schools with the same per–pupil operational funding as received by other schools in the same school district. The state subsequently modified this policy in 1998, enacting legislation specifying that “charter school operational funding shall be equal to the total funding that would be available to a similar school district serving a similar pupil population.” This policy remains in place. To assess the extent to which this policy is being met, we analyzed per–pupil Proposition 98 operational funding for charter schools and their school district peers. Due to data limitations, we focused our analysis primarily on direct–funded charter schools. (These schools receive funding directly from the state whereas locally funded charter schools have some of their funding allocations embedded within their local school district’s allotment.)

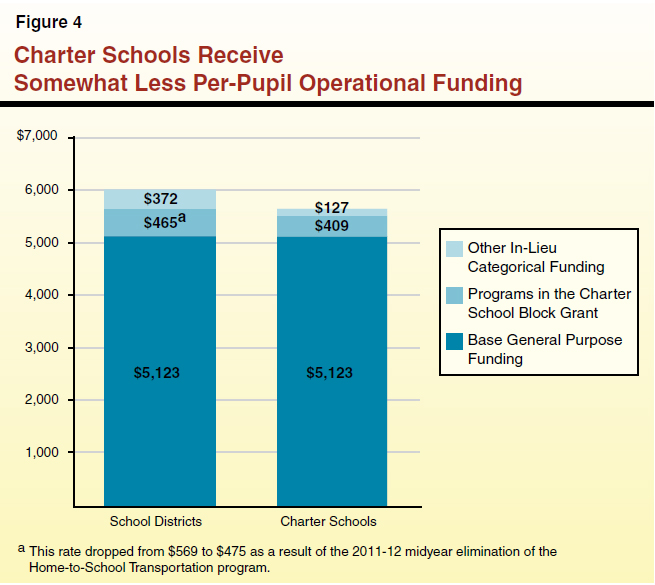

Total General Purpose Per–Pupil Funding Is Somewhat Less for Charter Schools. In 2010–11, charter schools received, on average, $395 per pupil (or 7 percent) less in total general purpose funding than their school district peers. This difference is relatively small because the largest single source of funding—base general purpose funding—is comparable for both groups. Charter schools, however, receive less in–lieu (or “flexible”) categorical funding. The $395 per–pupil funding gap is attributable to school districts receiving $150 more for programs in the Charter School Categorical Block Grant (CSBG) and $245 more for other in–lieu categorical programs. With the 2011–12 midyear elimination of the Home–to–School (HTS) transportation program, the per–pupil funding gap for programs in the CSBG decreased from $150 to $56—lowering the total funding gap to $301 per pupil.

Funding Gap Increases as a Result of Changes in K–3 Class Size Reduction (CSR) and Mandate Rules. The funding gap between charter schools and their school district peers grows if one accounts for recent changes in K–3 CSR and mandate rules. Regarding K–3 CSR, in 2008–09, the state barred any new schools or additional classrooms from participating in the program. Because of the relatively rapid growth of new charter schools, only 49 percent of total K–3 charter school students participated in the program in 2010–11 whereas approximately 95 percent of school district K–3 students participated. This resulted in an additional funding gap of $721 per pupil for new charter schools. Regarding education mandates, the Commission on State Mandates (CSM) made a determination in 2006–07 to disallow charter schools from receiving mandate reimbursement, and the Controller subsequently stopped reimbursing charter schools in 2009–10. While claiming school districts receive on average $46 per pupil to complete certain mandated activities that also apply to charter schools, charter schools receive no associated funding.

Three Recommendations if Existing K–12 Funding Structure Retained. We recommend the Legislature equalize the funding rates of charter schools and their school district peers as well as provide more flexibility for both groups of schools. The Legislature could achieve these objectives either by making changes within the existing K–12 finance system or fundamentally restructuring the existing system. If the existing K–12 funding structure were retained, we recommend the Legislature:

- Equalize In–Lieu Categorical Funding Rates. We recommend providing charter schools with the average statewide amount received by school districts for all in–lieu categorical programs—$837 per pupil (a $301 increase from the existing rate of $536 per pupil). Completely closing this funding gap in 2012–13 for the roughly 440,000 charter students projected statewide would cost $133 million. Given the state’s current fiscal condition, the Legislature could close the funding gap over a multiyear period.

- Maximize Flexibility for Charter Schools and School Districts. We recommend making K–3 CSR flexible for both charter schools and school districts by including these funds in their base general purpose allocations and providing the same associated per–pupil funding rate to new charter schools. If new charter schools were provided the statewide average K–3 CSR funding rate, this would cost the state $16 million in 2012–13. Similarly, we recommend placing all remaining career technical education programs (agricultural vocational education, Partnership Academies, and apprentice programs) into base general purpose allocations.

- Provide Charter Schools In–Lieu Mandate Funding. We recommend the state provide $23 per charter pupil to fund the 17 mandated activities that apply to charter schools. This would cost the state $10 million in 2012–13. We recommend the state provide this amount as a supplement to the CSBG. (This funding rate equates to roughly half the amount provided to school districts that file mandate claims, on the rationale that charter schools will incur lower costs as a result of not needing to participate in the state’s formal mandate process.)

Two Recommendations if Legislature Pursues More Fundamental Restructuring. Though the above changes would eliminate existing funding disparities between charter schools and school districts, the Legislature could pursue more fundamental restructuring of the K–12 finance system. If a new system were designed to replace the existing one, we recommend the Legislature:

- Apply the Same Basic Funding Model to Charter Schools and School Districts. For both charter schools and school districts, we recommend funding a base general purpose allocation—one that is rationale, simple, and transparent—along with a few block grants linked with student needs, and then equalizing associated per–pupil rates over time. Alternatively, the Legislature could consider the Governor’s proposal to create a weighted student formula, which also would provide additional funding for disadvantaged students and equalize per–pupil rates over time.

- Allow Charter Schools Access to Certain Mandate–Related Funding. In addition to categorical restructuring, the Legislature could consider fundamental changes to the existing mandate reimbursement system. If this course of action were pursued, we recommend applying the new system to both charter schools and school districts. While we think the Governor’s discretionary mandate block grant proposal is a reasonable starting point, we recommend allowing both charter schools and school districts access to the associated funding.

|

Introduction

In this report, we assess whether operational funding received by charter schools and their school district peers is comparable. For the purposes of this report, we define operational funding as all Proposition 98 unrestricted and restricted funding designated for school operations. (We exclude funding for school facilities.) Proposition 98 funding is comprised of both state General Fund and local property tax revenues. Our analysis primarily focuses on direct–funded charter schools, which make up approximately 75 percent of all active charter schools. This is because complete school–level funding information is not available for locally funded charter schools that receive some allocations indirectly through their local school district. Despite this data limitation, our funding comparisons apply to the vast majority of charter schools. Our analysis is based on data from 2010–11—the most recent year for which reliable fiscal and attendance data are available. We adjust these data, however, to account for the recent elimination of the HTS transportation program. Below, we (1) describe the funding models used for charter schools and school districts, (2) compare funding rates for the two groups, and (3) provide recommendations for simplifying the funding system, maximizing flexibility for both school types, and equalizing funding rates.

Existing Funding System

In 1992, the legislation that authorized charter schools created a funding model intended to provide charter schools with comparable operational funding as received by other schools in the same school district. This locally focused model required that school districts pass through a negotiated amount of funds to charter schools without a clear way of monitoring if funding was following each student. The state significantly changed this policy in the late 1990s and created a statewide funding model specifying that “charter school operational funding shall be equal to the total funding that would be available to a similar school district serving a similar pupil population.” Rather than having a variety of locally negotiated funding rates for charter schools throughout the state, this policy established statewide rates for charter schools. Though two relatively minor changes subsequently were made to the categorical funding component of this funding model, the policy established in 1998–99 essentially remains in place today. (Figure 1 summarizes the major legislation affecting charter schools’ funding over the years.)

Figure 1

Major Charter School Funding Legislation

|

Year

|

Legislation

|

Major Provisions

|

|

1992

|

Chapter 781

|

- Created first charter school funding model. Established that charter schools receive the same level of per–pupil revenue limit funding as their sponsoring school district. Also provided charter schools with access to designated categorical funding (including special education funding).

|

|

1998

|

Chapter 34

|

- Declared that “charter school operational funding shall be equal to the total funding that would be available to a similar school district serving a similar pupil population.” Tasked the California Department of Education with implementing this provision.

- Also allowed charter schools to choose whether to receive funding through the local school district or directly from the state.

|

|

1999

|

Chapter 78

|

- Created the current charter school funding model. Model includes a general purpose entitlement, a base Charter School Categorical Block Grant, and in–lieu Economic Impact Aid funding.

- Changed charter schools’ general purpose entitlement from their district’s revenue limit rate to the statewide average provided to districts serving the same grade–level student.

|

|

2005

|

Chapter 359

|

- Revised the list of programs in the Charter School Categorical Block Grant and set an associated per–pupil funding rate ($400 in 2006–07, $500 in 2007–08, and adjusted annually thereafter for inflation).

|

|

2009

|

Chapter 2

|

- Allowed school districts and charter schools to use funds from 34 applicable categorical programs for any educational purpose. Of the 34 programs for which flexibility was provided, 21 were already in the Charter School Categorical Block Grant.

|

Four Major Sources of Funding. Currently, the state provides four major types of operational school funding. As shown in Figure 2, the state provides: (1) base general purpose funding (commonly called revenue limits for school districts and general purpose entitlements for charter schools), (2) in–lieu categorical funding, including programs in the CSBG and other flexible categorical programs, (3) restricted funding tied to specific policy goals and programmatic requirements, and (4) mandate reimbursements linked with certain state–imposed activities. (This figure excludes a few programs that apply only to a few districts and/or county offices of education [COEs].) The sections below discuss each of these four types of funding in more detail.

Figure 2

School Funding Model

|

Base General Purpose Funding

|

|

Revenue limits

|

General purpose entitlements

|

|

In–Lieu Categorical Funding (37)

|

|

Flexible Programs in CSBGa:

|

Flexible Programs Not in CSBG:

|

|

Advanced Placement Grant Programs

|

Adult education

|

|

Agricultural vocational educationb

|

Alternative Credentialing/Internship program

|

|

Bilingual teacher training assistance program

|

Arts and Music Block Grant

|

|

Deferred maintenance

|

California High School Exit Exam supplemental instruction

|

|

Foster youth programsb

|

California School Age Families

|

|

Gifted and Talented Education

|

California Technology Assistance Projects

|

|

Instructional Materials Block Grant

|

Certificated Staff Mentoring

|

|

Ninth–Grade Class Size Reduction

|

Community Based English Tutoring

|

|

Peer Assistance and Review

|

Community Day School

|

|

Principal Training

|

Grade 7–12 counseling

|

|

Professional Development Block Grant

|

National Board certification incentive grants

|

|

Professional development for Math and English

|

Oral health assessments

|

|

Pupil Retention Block Grant

|

Physical Education Block Grant

|

|

Reader services for blind teachers

|

Regional Occupational Centers and Programs

|

|

School and Library Improvement Block Grant

|

Summer school programs/supplemental instruction

|

|

School Safety Block Grant

|

Teacher Credentialing Block Grant

|

|

School Safety Competitive Grant

|

|

|

Specialized secondary program grants

|

|

|

Targeted Instructional Improvement Block Grant

|

|

|

Teacher dismissal apportionment

|

|

|

Year–Round School Grantsb

|

|

|

Restricted Programs (9)

|

|

After School Education and Safety Program

|

Economic Impact Aidb

|

|

Apprentice programs

|

Partnership Academies

|

|

Assessments

|

Quality Education Investment Act

|

|

Child nutrition

|

Special education

|

|

Class Size Reduction (K–3)

|

|

|

Reimbursable Mandates (36)

|

|

See Figure 3 for list of mandated programs

|

|

Base General Purpose Funding

Both charter schools and school districts receive base per–pupil funding that can be used for any educational purpose. This funding is primarily used for the general operating costs associated with schools, such as salaries and benefits for teachers, administrators, aides, and other school support staff. This is the largest funding source for both school types. Despite these similarities, differences exist in how charter school and school district rates are determined. School district rates are unique to each district based on historical factors. In contrast, charter schools all receive the same per–pupil general purpose rate based on school districts’ statewide averages in four grade spans: K–3, 4–6, 7–8, and 9–12. Charter school rates range from $5,077 for schools with students in kindergarten through third grade to $6,148 for charter high schools. In general, this component of the funding model results in little disparity (while also incentivizing charter schools to locate in any part of the state).

In–Lieu Categorical Funding

In addition to base general purpose funding, both charter schools and school districts receive in–lieu categorical funding. This funding is akin to general purpose funding in that the associated categorical requirements have been removed—that is, the funding comes in lieu of having to comply with specific categorical rules. As with base general purpose funding, this funding can be used for any educational purpose (including each program’s intended purpose, if desired). Two major types of in–lieu categorical funding exist, as described below.

Programs in the CSBG. With the creation of the CSBG in 1999, most of the in–lieu categorical funding charter schools receive is from the block grant. The block grant provides funding in lieu of 21 categorical programs. As shown in Figure 2, many of the programs in the CSBG fund basic school operations, such as instructional materials, professional development, and facility maintenance. Rather than having to operate these 21 categorical programs, charter schools can use their in–lieu funding for any educational purpose. Block grant funding is linked to a single per–pupil amount and school allocations are adjusted annually for changes in student attendance. (In–lieu Economic Impact Aid [EIA] funding also is provided through the categorical block grant, as discussed later in the report.)

“Flexed” Programs Not in the CSBG. Charter schools and school districts received significant new flexibility in 2009. Chapter 2, Statutes of 2009 (ABX4 2, Evans), allows charter schools and school districts to use funds associated with 34 applicable categorical programs for any educational purpose. As shown in Figure 2, many of these flexed programs also were originally intended to fund certain basic school operations, such as adult education, summer school, and counseling. Of the 34 flexed programs, 18 programs already were included in the CSBG, with 16 programs newly flexed. Thus, the flexibility granted in 2009 was more substantial for school districts than charter schools. For existing charter schools and school districts, flexed funding allocations are locked in at 2008–09 levels, with allocations not adjusted annually for increases or decreases in student attendance. New charter schools, however, receive the average statewide charter school amount for the 16 flexed programs not in the CSBG ($127 per pupil), adjusted for changes in student population.

Restricted Categorical Funding

Increased categorical funding flexibility shortened the list of stand–alone programs that charter schools and school districts are required to apply for separately. Nonetheless, a school district must still access funding for 12 programs separately, whereas a charter school must access funding for eight programs separately (see Figure 2). Each of these stand–alone programs has a specific set of requirements, eligibility rules, and funding rate determinations that generally apply to charter schools and school districts in similar ways. The three largest categorical programs are special education, K–3 CSR, and EIA. We discuss these three programs in more detail below.

Special Education. The largest restricted program is special education, which supports an array of education services for students with disabilities. The program has specific rules intended to ensure funding equity among regions in the state, with funding distributed to 126 Special Education Local Plan Areas (SELPAs). In turn, SELPAs allocate funds and organize services for their member local educational agencies (LEAs) based on local plans. For SELPA purposes, charter schools can choose to be part of a school district or they can choose to be deemed an LEA, thereby becoming a direct member of the SELPA. As of 2011–12, two SELPAs—run out of El Dorado COE and Los Angeles COE—consist of only charter school members, with another such SELPA (run out of Sonoma COE) likely to begin operating in 2012–13. We do not address special education funding issues in detail in this report because any change to the SELPA funding model could have notable implications statewide. Though we are aware of concerns that some charter schools are receiving too little or too much special education funding, we believe these issues are better addressed as part of a more comprehensive special education funding conversation.

K–3 CSR. The second largest categorical program is K–3 CSR. The original purpose of this program was to reduce class sizes to 20 or fewer students in the early grades. The funds are intended to be used for the operational costs associated with decreasing class sizes, including the costs of hiring additional teachers. Charter schools and school districts must follow the same requirements to receive funding and are subject to the same funding reductions if they exceed the class–size caps. The state recently modified these funding–reduction rules. Since 2008–09, school districts and existing charter schools have been able to receive up to 70 percent of the full funding rate for K–3 class sizes of 25 or more students. The full funding rate is the same for all participants—$1,071 for each full–day student in a K–3 class of 20 or fewer students. The rates vary for school districts and charter schools depending solely on the number of participating classrooms and the size of those classrooms.

EIA. The third largest categorical program is EIA, which provides funds to charter schools and school districts for supplemental support of economically disadvantaged (ED) students and English learner (EL) students. The state requires that school districts use these funds to provide ED and EL students with additional educational resources, such as hiring classroom aides, offering after–school tutoring, reducing class sizes, engaging parents, and purchasing supplemental instructional materials. In contrast, charter schools can use these funds for any educational purpose. Each charter school and school district’s annual allocation is based on their total counts of ED and EL students (a student that is both ED and EL generates funding under both designations). The per–pupil EIA funding rate varies among school districts for historical reasons. By comparison, charter schools all receive the same statewide average per–pupil EIA rate ($337 in 2010–11). The program provides minimum grants if a charter school or district’s ED and EL student counts are very small (lower than 25 students) to ensure sufficient funding of additional support services. Additional funding is also provided to charter schools and school districts with very large proportions of these populations (at least 50 percent of total enrollment) on the assumption that higher concentrations of ED or EL students require more supplemental services.

Mandate Funding

In addition to applying for categorical program funding, school districts can seek reimbursement for certain state–mandated activities. The state is constitutionally required to pay for new programs, activities, or higher levels of service it imposes on school districts. As shown in Figure 3, school districts currently are subject to 36 active mandates, ranging from requirements to annually notify parents of certain school policies and collectively bargain certain personnel issues to requirements on conducting teacher evaluations and keeping student immunization records. Of the 36 mandates school districts are required to complete, charter schools are either statutorily or implicitly required to do 17 of the same or similar activities. Despite being required to undertake these activities, charter schools are not eligible to seek associated reimbursement. This is because the CSM determined in 2006–07 that charter schools were not eligible claimants, and the Controller consequently cut off all reimbursement for all mandated activities in 2009. (Prior to 2009, charter schools had received reimbursement for certain mandated activities.)

Figure 3

Charter Schools Required to Do Some Mandate–Related Activities

|

Required Activities for Both Charter Schools and School Districtsa

|

|

Agency Fee Arrangements

|

High School Exit Examination

|

|

Behavioral Intervention Plansb

|

High School Science Graduation Requirementsb

|

|

California State Teachers’ Retirement System Service Credit

|

Immunization Records—Hepatitis B

|

|

Caregiver Affidavits

|

Immunization Records—Original

|

|

Collective Bargaining

|

Missing Children Notifications

|

|

Comprehensive School Safety Plans

|

Physical Performance Tests

|

|

Criminal Background Checks I–II

|

Pupil Health Screenings

|

|

Expulsion Transcripts

|

Pupil Suspensions, Expulsions, and Expulsion Appeals

|

|

Financial Compliance and Audits

|

|

|

Required Activities Only for School Districts

|

|

Stull Act

|

Mandate Reimbursement Process

|

|

Absentee Ballots

|

Notification of Truancy

|

|

AIDS Prevention Instruction I–II

|

Notification to Teachers of Mandatory Expulsion

|

|

Annual Parent Notification

|

Open Meetings Actc

|

|

Charter Schools I–III

|

Pupil Safety Notices

|

|

Differential Pay and Reemployment

|

School Accountability Report Cards

|

|

Habitual Truant Parent Notification and Conference

|

School District Fiscal Accountability Reporting

|

|

Inter/Intradistrict Attendance

|

County Office Fiscal Accountability Reporting

|

|

Juvenile Court Notices II

|

School District Reorganizations

|

|

Law Enforcement Agency Notifications

|

|

Funding Disparities

Charter schools are, on average, receiving less operational funds per pupil than their school district peers due to lower in–lieu categorical funding rates. As shown in Figure 4, school districts received $5,960 per pupil in 2010–11 (adjusted for the elimination of the HTS transportation program) whereas charter schools received $5,659. This funding disparity grows by approximately $46 per pupil if one considers mandate reimbursement rules. Moreover, new charter schools serving K–3 students experience an even wider funding disparity given they are disallowed from receiving any K–3 CSR funding. Below, we discuss our findings in more detail.

Inequities Between Charter Schools and Their School District Peers Linked to Categorical Block Grant… Under current law, charter schools were to receive $500 per pupil in CSBG funding in 2007–08, adjusted annually thereafter for inflation. Due to recent budget cuts, however, charter schools received $409 per pupil in 2010–11. This charter rate is $150 less per pupil than the funding rate provided to school districts for the same programs—resulting in charter schools receiving $53 million less statewide than school districts serving the same number of students in 2010–11. In 2011–12 and moving forward, this funding gap was reduced to $56 due to the elimination of the HTS transportation program.

…And Other In–lieu Categorical Funding. As shown in Figure 4, school districts receive $372 per pupil for the 16 programs made flexible but not in the CSBG. Charter schools receive less for these programs, with charter schools existing prior to 2008–09 receiving, on average, $127 per pupil and charter schools opening after 2008–09 each receiving exactly $127 per pupil. In 2010–11, this disparity resulted in charter schools receiving approximately $85 million less statewide than school districts serving the same number of students.

Inequities Exacerbated by Changes to K–3 CSR Participation and Eligibility for New Schools. The funding gap between charter schools and school districts is exacerbated by low charter participation rates in K–3 CSR due to recent changes in eligibility requirements. Whereas funding rates are generally comparable for both based on program rules, school districts and charter schools participate at very different rates. Approximately 95 percent of all district K–3 students participate in the program whereas only 49 percent of all K–3 charter students participate. This difference largely is a result of charter schools opened after 2008–09 being ineligible to apply for the program. This is particularly problematic given the number of charter schools in California has been growing about 12 percent annually in recent years. (Though the K–3 CSR funding rules are the same for school districts and charter schools, charter schools received $836 per pupil in 2010–11 compared to $718 per pupil for school districts, indicating that charter schools are keeping their K–3 class sizes somewhat lower than their district peers.)

…And by Lack of Access to Mandate Reimbursements. For the 17 mandated activities charter schools are required to complete, charter schools receive no funding. By comparison, school districts that claim reimbursement for those 17 mandates receive on average a total of $46 per pupil. (Considerable funding disparities also exist among districts, as less than one–third apply for reimbursement.)

Addressing Funding Disparities

Given these funding disparities, the state does not appear to be meeting its statutory objective of providing equal operational funding for charter schools and their school district peers. To address these disparities, we recommend equalizing the funding rates of charter schools and their school district peers as well as providing more flexibility for both groups of schools. The Legislature could achieve these objectives by either making changes within the existing K–12 finance structure or fundamentally restructuring the existing system. Below, we first discuss our specific recommendations if the Legislature chooses to retain the existing finance structure. We then discuss our recommendations if the Legislature chooses to pursue more fundamental school funding restructuring.

Recommendations if Existing K–12 Funding Structure Retained

If the Legislature chooses to retain the existing K–12 funding structure, we have three recommendations, which, if taken together, would essentially eliminate the funding disparities between charter schools and their school district peers and provide both with more flexibility.

Equalize In–Lieu Categorical Funding Rates. Rather than providing charter schools with the single rate of $409 in the CSBG and the average rate of $127 in flexible funding for programs not included in the block grant, we recommend providing charter schools with the annual statewide average received by school districts for all in–lieu categorical funding. This would increase the charter rate from $536 to $837 per pupil—an increase of $301 per pupil. The total additional cost of closing this funding gap in 2012–13 is $133 million. Connecting the funding determination for charter schools with that provided to school districts would ensure both groups receive the same amount of flexible categorical money each year—thus ensuring both experience budget increases and cuts similarly moving forward. Given the state’s current fiscal condition, the Legislature could close this funding gap over a multiyear period. For example, the state could schedule charter funding increases over the next three years (2012–13 through 2014–15), such that the charter rate equaled the statewide average district rate by the end of the period.

Remove More Strings for Both Charter Schools and School Districts. We also recommend providing even more flexibility for certain remaining stand–alone programs. Of the remaining categorical programs, a few make particularly good candidates for flexing (whereas flexing others, such as those connected to settlements or ballot measures, would be more problematic). Specifically, we recommend making K–3 CSR and all remaining career technical education (CTE) programs (agricultural vocational education, Partnership Academies, and apprentice programs) flexible for both school districts and charter schools. For each of these programs, we believe districts would benefit more from flexible dollars. For K–3 CSR, we recommend folding funding into the base general purpose allocations of elementary/unified school districts and charter schools. In addition, we recommend providing associated funding to new charter schools. This would cost approximately $16 million in 2012–13 (by providing the statewide average rate of $721 for all new charter school average daily attendance). For the CTE programs, we recommend folding all CTE funds into the base general purpose allocations of high school/unified school districts and charter high schools. In 2010–11, the state provided a total of $39 million for these restricted programs combined. In our report,

Year–Two Survey: Update on School District Finance, the majority of districts stated they would like some or much more flexibility for these CTE programs, indicating they believe they can benefit from modifying the programs to better meet local priorities or redirecting the funds to other higher local priorities. Moreover, the state already has made funding flexible for Regional Occupation Centers and Programs—a much larger CTE program. (In contrast to our general recommendation to remove strings from many currently restricted programs, we recommend requiring charter schools to apply separately for foster youth funding rather than allowing them to access in–lieu funding through the block grant as they now do. The Foster Youth Program is primarily operated by COEs, with funding based on foster student counts in the region. For these reasons, the program is not an ideal candidate for the charter block grant.)

Fund Charter Schools for State–Mandated Activities Imposed on Them. Because charter schools are required to complete 17 mandated activities similar to other public schools, we recommend the state provide them with associated funding. Rather than requiring them to participate in the state’s mandate system, however, we recommend providing charter schools with a funding supplement to the CSBG. Because all charter schools would receive funding without undertaking the mandate reimbursement process under our approach, we believe they could complete the required activities for notably less than their school district peers. As a result, we recommend providing charter schools with less funding than their school district peers. For example, the state could provide charter schools with half the per–pupil funding provided to school districts that file mandate claims ($23 per pupil). (In setting the specific per–pupil funding rate for charter schools, the Legislature, however, could make a different assumption regarding the amount of efficiency likely to be achieved as a result of charter schools not needing to undertake the reimbursement process.) If the Legislature were to provide charter schools half of the per–pupil funding going to participating districts, the statewide cost would be $10 million in 2012–13. Moving forward, if additional mandates were imposed on charter schools, we recommend adjusting the funding supplement commensurately.

Recommendations if Fundamental Restructuring Is Pursued

Many research groups and other education stakeholders have concluded that California’s K–12 school finance system is complex, irrational, and inequitable. Though general improvements recently have been made to simplify, equalize, and provide more flexibility to school districts and charter schools, certain components of the current school funding model are still overly complex and result in funding disparities amongst schools serving similar students. Specifically, the state’s categorical program funding approach is deeply flawed and contains notable discrepancies in state funding both among school districts and between school districts and charter schools. Though the Legislature could equalize funding and increase flexibility for both school types under the existing K–12 funding structure, we think an even better approach would be to improve the entire K–12 funding system going forward and place school districts and charter schools on the same funding model. Having all schools under the same funding model would not only eliminate existing funding disparities but make funding disparities less likely to reemerge in the future. The Legislature could consider two basic approaches if it pursues restructuring of the funding system: a block grant approach or a weighted student formula. Both approaches could be structured to ensure that funding disparities between charter schools and school districts (and among school districts) are eliminated.

Block Grant Approach. Rather than extend current categorical flexibility for additional years, the Legislature could improve the state’s K–12 funding system on a lasting basis by consolidating virtually all K–12 funding into base general purpose funding and a few block grants. Unlike the current in–lieu categorical program approach, a few block grants would provide flexibility while also allowing more opportunity for the state to ensure at–risk and/or high–cost students continue to receive the services they need. For example, the state might create a disadvantaged student block grant and a special education block grant to ensure school districts and charter schools dedicate additional resources to these higher–cost students. Regarding timing, we recommend the Legislature develop the new finance system before the end of in–lieu categorical funding flexibility in 2014–15, with implementation phased in over a few years, thereby allowing for equalization in funding rates to occur more gradually. In addition to making improvements permanent, our recommended approach would create a system that is simpler, more transparent, rational, and better connected to student needs for all schools.

Weighted Student Formula. Another restructuring approach would be to adopt the Governor’s proposal to create a new funding system that would provide more flexibility through a weighted student formula, with funding rates equalized for all school districts and charter schools on a lasting basis. Specifically, instead of the existing revenue limit and categorical funding model, the Governor proposes that all districts and charter schools receive an equal base per–pupil funding amount, plus additional general purpose funding intended to serve their disadvantaged students. He proposes phasing in the weighted student formula over five years, beginning in 2012–13, with full equalization for all schools achieved in 2016–17.

Recommend Pursuing Comprehensive Mandate Reform, Including Both Charter Schools and School Districts. While we recommend the Legislature directly address the current operational funding disparity created by charter schools exclusion from the mandate reimbursement process, we also recommend the state pursue fundamental changes to its education mandate process. As discussed in our report,

Education Mandates: Overhauling a Broken System, the state could vastly improve this system by eliminating nonessential requirements and then rethinking how it funds essential requirements. Moreover, if certain activities are deemed essential and charter schools are required to undertake them, then the state should address how best to fund charter schools for these activities. On a lasting basis, the state either could have charter–specific solutions or develop comprehensive solutions that apply to both charter schools and school districts. While the Governor’s proposal to provide school districts with a new mandate block grant deserves serious consideration, it applies only to school districts, thereby missing the opportunity to address charter schools’ access to funding for state–imposed activities.

Conclusion

Though the Legislature established its intent to provide school districts and charter schools serving similar student populations with comparable operational funding, we find that charter schools receive less per–pupil operational funding. Inequities are primarily linked to in–lieu categorical funding, K–3 CSR, and mandates. To address these issues, the Legislature either could modify or fundamentally restructure the state’s K–12 funding system. If the Legislature were to retain the existing finance system, we recommend equalizing in–lieu categorical funding rates, providing access to K–3 CSR funding for new charter schools, and providing access to funding for certain state–mandated activities that apply to all charter schools. If the Legislature were to pursue fundamental finance restructuring, then we recommend placing both charter schools and school districts on the same funding model. Specifically, we recommend adopting a simple and transparent base general purpose allocation, coupled with a few large block grants, potentially including a block grant for state–mandated activities. These improvements would ensure school districts and charter schools receive comparable funding for all students on a lasting basis.